Abstract

Malagasy is a language with non-culminating accomplishments. There is, however, a specific prefix (maha-), which appears to entail culmination. Moreover, verbs prefixed with maha- display a range of interpretations: causative, abilitive, ‘manage to’, and unintentionality. This paper accounts for these two aspects of this prefix with a unified semantic analysis. In particular, maha- encodes double prevention. The double prevention configuration is associated with a circumstantial modal base, which leads to culminating readings in the past and future, but not the present tense. The embedding of double prevention in a force-theoretic framework leads to a more fine-grained theory of causation, which the Malagasy data show to have empirical relevance.

1 Introduction

The literature on non-culminating accomplishments notes an intriguing contrast between languages like English and languages like Skwxwú7mesh (a Salish language). In the former, accomplishment verbs in the perfective necessarily culminate, while in the latter, culmination is often an implicature, but not an entailment. We can see this contrast in the example below from Skwxwú7mesh (Jacobs 2011: 111) and its English translation.

| chen | lhích’-it-Ø | ta | seplin welh | es-kw’áy | an | tl’exw-Ø |

| 1sg.sub | 1cut-ctr-3obj | det | bread but | stat-cannot | too | hard-3sub |

‘#I cut the bread but I couldn’t. It was too hard.’

Cutting the bread qualifies as an accomplishment that culminates in a state of the bread being cut. The inference to the result state can be canceled in Skwxwú7mesh, but not in English.

Malagasy is often mentioned in this context as a language with non-culminating accomplishments. An example is provided in (2b), where culmination is only implied, not entailed. This example contrasts with (2a), which is incompatible with a denial of culmination (much like its English translation). The two examples have the same verb root (sambotra ‘catch’), but differ in verbal morphology: (2a) bears Actor Topic voice (AT), whereas (2b) uses maha-.[1]

| Nisambotra | alika | ny | zaza | nefa | faingana | loatra | ilay | alika |

| pst-at-catch | dog | det | child | but | fast | too | def | dog |

| ka | tsy | azony. | ||||||

| comp | neg | do-3 |

‘The child caught a dog #but it was too fast, so it didn’t get caught by him.’

| Nahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza | #nefa | faingana | loatra | ilay | alika |

| pst-aha-catch | dog | det | child | but | fast | too | def | dog |

| ka | tsy | azony. | ||||||

| comp | neg | do-3 |

‘This child managed to catch a dog #but it was too fast, so it didn’t get caught by him.’

The prefix maha-, as well as apparently encoding culmination, also appears to be ambiguous between an ability reading and a causative reading, as illustrated in (3) (adapted from Phillips 2000).

| Mahaongotra | fantsika | amin’ | ny | tanana | Rabe. |

| prs-aha-pull.out | nail | with | det | hand | Rabe |

‘Rabe can pull out nails with his hands.’

| Mahatony | an’ | i | Soa | Rabe. |

| prs-aha-calm | acc | det | Soa | Rabe |

‘Rabe makes Soa calm.’

This paper places the Malagasy data in (2) in the context of the general debate on culminating and non-culminating accomplishments. Rather than aiming at an explanation of the non-culminating accomplishment in (2a) per se, we focus on the syntax-semantics interface of Malagasy voice that explains the differences between (2a) and (2b), as well as the readings in (3).

Our analysis builds on core insights from Paul et al. (2015, 2016, but shifts the burden of explanation to maha-. We take our inspiration from Phillips (1996, 2000 and Travis (2010), who analyze maha- as a functional predicate, akin to English experiencer or causative have in examples like ‘Mary had the students revise their papers twice’. Our central claim is that maha- introduces a relation that Wolff (2007, 2014 labels double prevention. In Wolff’s analysis, double prevention underlies the semantics of English enable or allow in examples like ‘He allowed the water to flow down the drain’ in contexts where a plug in the sink prevents the water from flowing down the drain, and an agent who removed the plug prevents the plug from doing so, enabling the water to run down the drain. We will show how double prevention comes into play in sentences containing different kinds of roots (eventive and stative), and how it accounts for the range of readings labeled enablement, causation and unintentionality in the literature.

The outline of the paper is as follows. Section 2 provides a short background on Malagasy grammar. Section 3 presents the data on culminating and non-culminating accomplishments in the language. In Section 4 we walk through our analysis and Section 5 concludes.

2 Background on Malagasy

Malagasy is an Austronesian language spoken in Madagascar that has fairly rigid VOS word order. Importantly for this paper, the language has what is often described as a rich voice system. Simplifying somewhat, the verbal morphology indicates the semantic role of the subject (sometimes called the “topic” or “trigger” in the literature). Thus Actor Topic verbs have an agent as the subject, as in (4a), and Theme Topic verbs have a theme subject, as in (4b). The third voice is called Circumstantial Topic and almost any other non-core argument can be the subject (in (4c) it is an instrument). When the agent is not the subject, it appears adjacent to the verb, as in (4b), (4c).

Actor Topic (AT) – Subject is agent

| Nanapaka | ity | hazo | ity | tamin’ | ny | antsy | i | Sahondra. |

| pst-at-cut | dem | tree | dem | pst-with | det | knife | det | Sahondra |

‘Sahondra cut this tree with the knife.’

Theme Topic (TT) – Subject is theme

| Notapahin’ | i | Sahondra | tamin’ | ny | antsy | ity | hazo | ity. |

| pst-tt-cut | det | Sahondra | pst-with | det | knife | dem | tree | dem |

‘Sahondra cut this tree with the knife.’

Circumstantial Topic (CT) – Subject has some other role

| Nanapahan’ | i | Sahondra | ity | hazo | ity | ny | antsy. |

| pst-ct-cut | det | Sahondra | dem | tree | dem | det | knife |

‘Sahondra cut this tree with the knife.’

As noted in the literature on Malagasy, each voice can be realized by a range of different forms. For example, active voice is associated with the prefixes mi-, man-, ma-, and maha-. In the literature, it is therefore standard to treat maha- as a voice marker and we will follow this tradition in this paper.

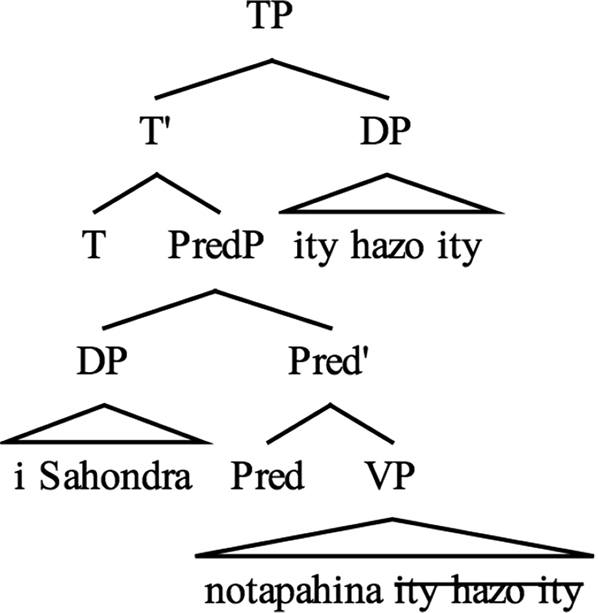

We follow most syntactic work on Malagasy and assume that there is a major constituent made up of the verb and its internal arguments; the clause-final subject appears to the right of this constituent (Keenan 1976). Adopting Pearson (2005), we refer to this constituent as PredP. We provide a simplified syntactic representation in (5b) and (6b) for AT and TT sentences, respectively.[2] To obtain verb-initial word order, we assume verb movement to T, but this movement is not shown in the trees.

| Nanapaka | ity | hazo | ity | i | Sahondra. |

| pst-at-cut | dem | tree | dem | det | Sahondra |

‘Sahondra cut this tree.’

|

| Notapahin’ | i | Sahondra | ity | hazo | ity. |

| pst-tt-cut | det | Sahondra | dem | tree | dem |

‘This tree was cut by Sahondra.’

|

Both (5a) and (6a) are interpreted as non-culminating accomplishments. That is, they implicate, but do not entail the result state of the tree being cut.

3 Non-culminating accomplishments

Non-culminating accomplishments have been documented in a wide range of languages, including Mandarin (Koenig and Chief 2008), Thai (Koenig and Muansuwan 2000), several Salish languages (Bar-el et al. 2005; Jacobs 2011), and Tagalog (Dell 1983). Moreover, for a certain class of verbs, we can see the same effect in English and French (Martin and Schäfer 2012).

| Ivan taught me Russian, but I did not learn anything. |

| Marie lui enseigna les rudiments du russe en deux semaines, et pourtant il n’apprit rien du tout. |

‘Marie taught him the basics of Russian in two weeks and yet he didn’t learn anything at all.’

The literature on this topic has considered several facts about non-culminating accomplishments that we will now illustrate with data from Malagasy. Although Phillips (2000), Travis (2010), and Paul et al. (2015) discuss non-culmination, there is no single complete description available.

3.1 Failed attempt vs. partial success

As noted by Tatevosov (2008), there are potentially two distinct non-culminating interpretations: what he calls failed attempt and partial success. On the first, the entire change of state does not take place, while on the second there is some change, but it is not complete. Both readings are possible with Malagasy Actor Topic verbs, such as nandrava ‘destroy’ in (8).[3]

| Nandrava | ny | tranony | Rabao | fa | tsy | voaravany. |

| pst-at-destroy | det | house-3 | Rabao | comp | neg | voa-destroy-3 |

‘Rabao destroyed her house but it didn’t get destroyed.’

i. She didn’t even manage to remove a single brick.

ii. She removed the roof and a wall, but not everything.

In other words, these predicates are compatible with a situation where there is no change of state (the house wasn’t affected at all). They are also possible in a situation where there is some change of state (the house is partially destroyed), but the complete change of state (the house being completely destroyed) does not occur. On the other hand, verbs with maha- do not allow non-culminating readings, whether failed attempt (9a) or partial success (9b).

| Naharava | ny | tranony | Rabe | # | fa | tsy | voaravany | mihitsy. |

| pst-aha-destroy | det | house-3 | Rabe | comp | neg | voa-destroy-3 | at.all |

‘Rabe was able to destroy his house but it didn’t get destroyed at all.’

| Naharava | ny | tranony | Rabe | # | nefa | tsy | rava | tanteraka. |

| pst-aha-destroy | det | house-3 | Rabe | but | neg | destroy | completely |

‘Rabe was able to destroy his house but it didn’t get completely destroyed.’

The maha-predicate naharava ‘destroy’ in (9a,b) entails that the destruction of the house is completed. As a result, it is incompatible with a follow-up sentence that denies the result state. We now turn to the interpretation of the subject.

3.2 Agent control hypothesis

Demirdache and Martin (2015) observe that the non-culminating reading correlates with agency and we see similar effects in Malagasy (shown below). We begin, however, with the contrast between the French examples in (10).

| Marie lui expliqua le problème en une minute, et pourtant il ne le comprit pas. |

| ‘Marie explained to him the problem in one minute, and yet he didn’t understand.’ |

| Ce résultat lui expliqua le problème de l’analyse, #pourtant il ne le comprit pas. |

| ‘This result explained to him the problem of the analysis, #yet he didn’t understand.’ |

In (10a), the subject, Marie, is agentive and the non-culminating construal is possible. In (10b), however, the subject is inanimate (and therefore non-agentive) and the non-culminating reading is not possible, giving rise to a contradiction.[4]Demirdache and Martin (2015) note that this pattern is also observed in German, Mandarin, and Salish. To account for this correlation, they formulate the Agent Control Hypothesis (ach):

s-ach (strong version)

| Zero result and partial result nc construals require the predicate’s external argument to be associated with ‘agenthood’ properties. |

w-ach (weak version)

| Zero result nc construals only require the predicate’s external argument to be associated with ‘agenthood’ properties. |

Looking crosslinguistically, we note that what counts as “agenthood” varies across languages. In Romance, Germanic and Mandarin, there appears to be a correlation with animacy. In Salish, however, even animate/human subjects can be understood to be “non-agentive” with certain verb forms. These forms are called “limited-control” in Skwxwú7mesh (Jacobs 2011) and “non-control” in St’át’imcets (Davis et al. 2009) and are associated with a specific range of meanings (Thompson and Thompson 1992). We will see in (16) that these meanings also arise with maha-.

Non-control (Thompson and Thompson 1992: 52)

events which are natural, spontaneous-happening without the intervention of any agent;

events which are unintentional, accidental acts;

limited control, which is intentional, premeditated events which are carried out to excess, or are accomplished only with difficulty, or by means of much time, special effort, and/or patience, and perhaps a little luck.

In Malagasy, we also see that agenthood cannot be fully identified with animacy. The comparison of (8) and (13) shows that the non-culminating reading is always available with Actor Topic verbs, independent of the animacy of the subject.[5]

| Nandoro | ny tranoko | ny | afo | nefa | tsy | may | tanteraka. |

| pst-at-burn | dethouse-1sg | det | fire | but | neg | burned | completely |

‘The fire burned my house but it isn’t burned completely.’

In the context of the Agent Control Hypothesis, Skwxwú7mesh and Malagasy provide evidence that animates can be non-agentive and inanimates can be agentive, respectively.

Turning now to the culminating readings in Malagasy, as we have seen earlier in examples (2a) and (9), animate/human subjects are possible with maha-. On the other hand, as pointed out by Phillips (1996, 2000 and Travis (2010), maha- does impose certain restrictions on its subject. First, the subject must be understood as what Phillips calls a “stative causer”. She gives the following examples (Phillips 1996: 45–46).

| #Mahatsara | ny | trano | Rabe. |

| prs-aha-good | det | house | Rabe |

(intended) ‘Rabe makes the house beautiful.’

| Mahatsara | ny | trano | ny | voninkazo. |

| prs-aha-good | det | house | det | flowers |

‘The flowers make the house beautiful.’

Phillips notes that (14a) is odd and can only be understood as Rabe’s beauty making the house beautiful (the Actor Topic equivalent manatsara ‘improve’ is felicitous in this context). Travis (2010) observes that verbs with maha-, unlike other active verbs, are incompatible with agent-oriented adverbs, such as nanao fanahy iniana ‘do on purpose’, as shown by the contrast in (15). In (15a), the main verb is nameno ‘fill’ with Actor Topic voice and modification by this adverb is possible, while in (15b), the main verb is nahafeno ‘fill’ with maha- and modification leads to infelicity.

| [Nanao | fanahy | iniana]Adv | nameno | tavoahangy | Rakoto. |

| pst-at-do | spirit | tt-do.on.purpose | pst-at-fill | bottle | Rakoto |

‘Rakoto deliberately filled bottles.’

| #[Nanao | fanahy | iniana]Adv | nahafeno | tavoahangy | Rakoto. |

| pst-at-do | spirit | tt-do.on.purpose | pst-aha-fill | bottle | Rakoto |

‘Rakoto deliberately managed to fill bottles.’

Thus the key notion here is not animacy, but agency: the subject of a maha- verb must be non-agentive. Finally, although not reported in the literature, maha- also allows for readings where the subject does some action by accident (much like has been observed for Salish languages). The examples below all allow a ‘manage to’ and an accidental reading.

| Nahasotro | poizina | izy |

| pst-aha-drink | poison | 3 |

‘He drank poison’

| Nahatelina | moka | aho |

| pst-aha-swallow | mosquito | 1sg |

‘I swallowed a mosquito.’

| Nahapetraka | teo | ambony | tsilo | i Soa |

| pst-aha-sit | pst-loc | on | thorn | detSoa |

‘Soa sat on a thorn.’

The availability of the “accidentally” reading depends on context. For example, if the person was unaware of the poisonous nature of the drink, (16a) conveys unintentionality. But in a context where the person is trying to commit suicide, the interpretation is ‘managed to drink poison’. The context-dependency supports Phillips’s (1996) claim that the different readings are manifestations of one underlying semantics. This paper works out a unified semantics for maha- as encoding double prevention, while the readings are the result of different interactions between vectors, the strength and orientation of which is sensitive to world knowledge and discourse context.

In sum, the Malagasy data provide evidence in favor of the Agent Control Hypothesis, to the extent that culmination is linked to the absence of agentivity. We discuss how our analysis accounts for non-agentivity in Section 4.1.

3.3 The role of tense in triggering culmination

The role of tense in culmination has not received much attention in the literature (but see Matthewson (2012)). The examples in Section 3.2 illustrate that maha- gives rise to an entailment of culmination, but all these sentences are in the past tense. As it turns out, in the present tense maha- does not entail a change of state (e.g., at least once in the past). Let us look more closely at some examples – for ease of exposition, we gloss the m- prefix as present tense.[6] In (17), the first clause simply states the ability of the wolf to kill goats and the second clause explicitly denies that the wolf has ever actually killed one.

| Mahafaty | osivavy | ny | ambodia | fa | izy | mbola | tsy | hamono | fotsiny. |

| prs-aha-dead | goat | det | wolf | comp | 3 | still | neg | fut-at-kill | yet |

‘The wolf can kill a goat but it still hasn’t done so.’

The example in (18) is similar – it can be used to describe a car that has just come out of the factory and has never been driven.

| Mahaleha | 200 km/hre | ity | fiara | ity. |

| prs-aha-go | 200 km/h | dem | car | dem |

‘This car can go 200 km/h.’

On the other hand, maha- in the future tense entails culmination, just like it does in the past.

| Hahatitra | sakafo | ho an’ | ny reniny | i | Be |

| fut-aha-send | food | acc | detmother.3 | det | Be |

| #fa | tsy | ho | raisiny | ilay | sakafo. |

| comp | neg | fut | receive-3 | def | food |

‘Be will be able to send food to his mother but she won’t receive the food.’

Any account of maha- must take into consideration these facts.

The reader may wonder if the culminating reading in the past tense is in fact an actuality entailment, such as has been proposed in the literature for Hindi and French (see e.g., Bhatt (1999) and Hacquard (2006, 2009)). Actuality entailments are claimed to arise with ability modals in the perfective. We set this possibility aside for two reasons. First, there is evidence that past tense in Malagasy is not perfective (it is compatible with stative predicates). Second, as we argue in Section 4.5, maha- does not pattern with other modals in the language. Although Paul et al. (2016) as well as an anonymous reviewer suggest the possibility of a modal semantics for maha-, we have so far been unable to develop a modal analysis that accounts for its different readings in combination with the non-agentivity requirement on the external DP. For instance, we greatly appreciate the modal analysis of manage to developed in Baglini and Francez (2016), but we are not sure it covers the ability and unintentionality readings of maha-. Consequently, this leads us to think that the modal meaning component constitutes a side effect of the double prevention structure that we adopt as the conceptual meaning of maha-. We now turn to a detailed presentation of our proposed analysis.

4 Maha- encodes double prevention

Recall that we want to account for culmination, as well as the range of interpretations displayed by maha- predicates (causation, ability, unintentionality, ‘manage to’ readings). On the syntactic side, we take our starting point in the role of maha- as a morphologically complex functional predicate (Section 4.1). As we ground our semantics in the framework of causation and enablement developed by Wolff (2007, 2014 and Wolff et al. (2010), we introduce the theoretical setting in Section 4.2, and posit the hypothesis that maha- encodes double prevention in Section 4.3. Section 4.4 develops the conceptual and compositional semantics of maha- for stative and eventive roots. Section 4.5 works out the implications of the analysis for culmination in relation to past, present and future tense.

4.1 Maha- as a functional predicate

The analysis we work out in this section builds on core insights from Paul et al. (2015, 2016, but assumes a simpler mono-eventive lexical semantics for eventive roots. We take our inspiration from Phillips (1996, 2000 and Travis (2010), who analyze maha- as a functional predicate, akin to English experiencer or causative have in examples like (20):

| Mary had the students walk out on her. |

| Mary had the students revise their papers twice. |

What have and maha- have in common is that both introduce a relation between the external argument and a state or event embedded under the functional predicate. In contrast to English have, maha- does not encode experience or agentivity, because the external argument is construed as non-agentive. In Phillips’s terms, the external argument of a maha- phrase qualifies as a ‘stative cause’ (Phillips 1996: 82, 92). But what is a stative cause?

Phillips treats maha- as a morphologically complex voice marker composed of two parts: ma- and ha-. She assigns ma- the functional meaning of HAVE and ha- the meaning of BECOME, as illustrated in (22), that sketch the trees for (21):[7]

| Mahaongotra | fantsika | amin’ | ny | tanana | Rabe. |

| prs-aha-pull.out | nails | with | det | hand | Rabe |

‘Rabe can pull out nails with his hands.’

| Mahatony | an’ | i Soa | Rabe. |

| prs-aha-calm | acc | det Soa | Rabe |

‘Rabe makes Soa calm.’

| a. |  | b. |  |

The difference between eventive and stative roots plays a key role in Phillips’ analysis. The fact that Rabe is the external argument of a HAVE predicate makes the maha- verb stative. The BECOME predicate accounts for the causative meaning component of maha- that Phillips takes to underlie both the ability reading in (21a) and the causative reading associated with stative roots in (21b). Interestingly, the causative reading of English have in (20) implies that the inner argument (the students) carry out the action, while the external argument (Mary) is responsible for making it happen. This is not the case in Malagasy, where the two roles are assigned to the same argument (the external DP). In order to capture the special nature of the external argument, Travis (2010: 224) takes ha- to exceptionally assign a theta role in Spec of AspP. This leads to the structure in (23):

|

According to Travis, the theta role assigned to the DP in Spec of AspP depends on the nature of the root: states don’t have argument structure, so a default causative argument is added in Spec of AspP, which leads to the causative reading in (21b). Eventive roots, on the other hand, have an Agent, which is exceptionally discharged in Spec of AspP, giving rise to the ability reading in (21a). For our analysis, we adopt the distinction between stative and eventive roots, as well as the morphological decomposition of maha- into two morphemes, ma- and ha-. We follow Phillips in merging the internal argument in the specifier of the projection that hosts ha- and the external argument in the specifier of ma-.[8] Like Travis, we claim that the theta role associated with the external argument is non-agentive. We link the non-agentive role to the prefix ma-, which is typically found on stative verbs (see Phillips (1996) and Travis (2010) for discussion). The relevant structures are given below and will be discussed in detail in Section 4.4.

| Mahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza. | [eventive root: sambotra ‘catch’] |

| prs-aha-catch | dog | det | child |

‘The child can catch a dog.’

| Mahatony | an’ | i | Soa | Rabe. | [stative root: tony ‘calm’] |

| prs-aha-calm | acc | det | Soa | Rabe |

‘Rabe makes Soa calm.’

| a. eventive root | b. stative root |

|  |

Building on the analysis of maha- as a functional predicate proposed by Phillips and Travis, we make it our primary aim to work out the semantics of maha-. We do this in the framework of Wolff’s (2007, 2014 force-theoretic framework of causation, introduced in the next subsection.

4.2 A force-theoretic theory of causation and its relevance for maha-

Analyses of non-culminating accomplishments typically rely on the external argument being the agent of the action (see Section 3.2). As accomplishments typically imply a cause relation according to Dowty (1979), this is naturally tied in with the view that causation requires agentivity (see the overview in Copley and Wolff (2014)). This approach has led to investigations of the (quasi) agentive behavior displayed by inanimates in causative constructions, as illustrated in (26).

| John/The book had Mary laugh. |

| The sidewalk was warm from the sun. |

There is surprisingly little discussion in the literature on the inverse pattern, that is, relations that look similar to causation, but crucially rely on non-agentivity. But maha- seems to do exactly that. As pointed out in Section 3.2 above, (27a) is infelicitous unless somehow the house looks beautiful with Rabe in it:

| # | Mahatsara | ny | trano | Rabe. |

| prs-aha-good | det | house | Rabe |

| Mahatsara | ny | trano | ny | voninkazo. |

| prs-aha-good | det | house | det | flowers |

‘The flowers make the house beautiful.’

Most of the mainstream literature on causation focuses on agentive configurations like the ones in (26), but maha- requires us to look for analyses of causation that are compatible with non-agentivity. Note further that maha- does not necessarily imply causation, but can also convey enablement or unintentionality, so its analysis requires a more fine-grained picture of causation. These observations motivate the adoption of the force-theoretic framework developed by Wolff (2007, 2014 and Wolff et al. (2010), which elaborates earlier ideas on the conceptual structure of causation relations by Talmy (1988, 2000. Actions and events imply dynamics, energy and forces. We feel the difference in force between a light touch or a hard bump, so forces are distinct from individuals and events (Wolff 2007). Perception can influence language, so in a force-theoretic framework, forces are typically represented as vectors, which have an origin, a magnitude and a direction.

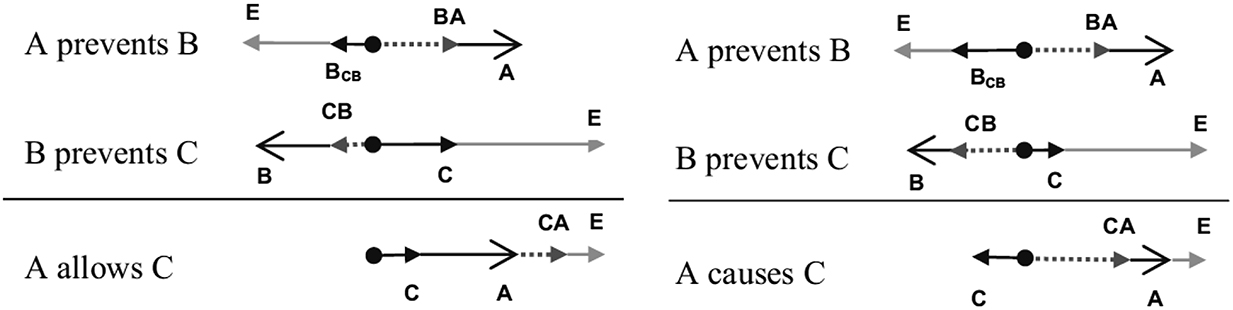

Wolff (2007) uses the vector-based representation of forces to distinguish three main configurations of causation, labeled cause, help and prevent. All three are defined in terms of two-place relations between an affector (A) and a patient (P). Directional forces are associated with both affectors and patients, while the end state (E) is a positional vector. He does not restrict the model to physical forces, but includes non-physical forces as well. This motivates the more general term of tendency towards an end state. When a patient or an affector has a tendency towards an end state, their vector points towards the end state, otherwise it points in a different direction. When the patient and the affector are in concordance, their vectors point in the same direction. Summing up the patient and the affector vector produces the resultant vector (R). Figure 1 (from Wolff et al. (2010: 195)) illustrates the three configurations.

Configurations of forces associated with cause, help/enable/allow, and prevent; A = the affector force; P = the patient force; R = the resultant force; E = endstate vector, which is a position vector, not a force.

As we see in Figure 1, Cause, help and prevent differ in the interactions between affector and patient, and we can model this difference in terms of directionality of the vectors associated with them. In a cause configuration, the patient P does not have a natural tendency towards the end state E (the P vector points away from E), the affector A opposes this tendency (the A vector points towards E), and the resultant vector R points towards the end state. An example Wolff provides is ‘the wind caused the boat to heel’: the force of the wind is not in concordance with the natural tendency of the boat, so the vectors are pointing in opposing directions, but the vector resulting from the composition of the two forces shows that the end state is heeling.

In a help configuration, the patient has a natural tendency towards the end state (the P vector points towards E), the affector concords with this tendency (the A vector also points towards E), and the resultant R is towards the end state. The help configuration comes into play in enablement and allow relations. An example Wolff provides is ‘Vitamin B enables the body to digest food’: the body (P) has a natural tendency to digest food, Vitamin B (A) concords with that tendency, and the end state (digestion) obtains.

In a prevent configuration, the patient has a natural tendency towards the end state (the P vector points towards E), the affector opposes this tendency (the A vector points away from E), and the resultant R does not point towards the end state. An example Wolff provides is ‘Rain prevented the tar from bonding’: the tar (P) has a tendency for bonding that is opposed by the rain (A), and the bonding (E) does not occur.

Classical causation as illustrated in (26) is captured by the cause relation in Figure 1: Mary wouldn’t have laughed, if it weren’t for John (or the book). What has been labeled as the causative reading of maha- in (27) could involve a cause configuration (along the lines of (28e) below), but it can also be taken to illustrate the help or enablement configuration in Figure 1. Under the enablement interpretation of (27), the room (P) has a natural tendency to look beautiful, but something is missing, and the presence of flowers or Rabe’s natural beauty (A) which supports the room’s tendency for beauty makes it possible for the room (P) to reach the end state (E). The force-theoretic approach brings out the difference between a cause and a help configuration through the oppposing or concording vectors linking affectors and patients, and their impact on the resulting end state. This more fine-grained picture of causation makes Wolff’s framework an attractive set-up for us to dig deeper into the semantics of maha-. As we hypothesize that maha- encodes a double prevention relation, we zoom in on this more complex configuration next.

4.3 Zooming in on double prevention

According to Wolff et al. (2010), enablement or allow relations in natural language are often complex in that they rely on the composition of two prevention relations. An example illustrates. If a plug in the sink prevents the water from flowing down the drain, someone who removes the plug from the sink, prevents the plug from doing its prevention work, so we can say that ‘Someone allowed (or enabled or helped) the water to flow down the drain’. There is no argument role for the plug in the natural language sentence, but the plug is clearly a factor in the situation described. To account for the role of the plug, Wolff models the enablement relation in terms of a composition of two prevention relations, called a double prevention configuration. A enables C is then modeled as A prevents B, B prevents C.

One of the interesting features of the prevent relation is that it doesn’t require events: the state of the plug being in the sink prevents the water from flowing down the drain, and no input of energy is needed. Wolff’s system also explains how absences can lead to changes in the world, as in ‘lack of water caused the plant to die.’ An analysis in terms of double prevention runs as follows: water prevents the plant from dying, but if no water reaches the plant, the one thing that prevented the plant from dying is prevented, and the plant dies.

Double prevention relations are modeled in Figure 2 (from Wolff et al. (2010)). The patient force in the conclusion is based on the vector addition of the patient forces in the two premises. Whether double prevention relations lead to enablement or causation depends on the strength of the patient tendencies in each of the prevention relations. In Figure 2, short arrows represent weak forces, while long arrows model strong ones.

The composition of two prevent relations can either lead to an allow (or enable) conclusion (left part) or to a cause conclusion (right part).

The manner in which the overall conclusion is reached is always the same: the affector from the conclusion is the affector from the higher prevent relation, the end state from the conclusion is the end state from the lower prevent relation, and the patient vector in the conclusion is the resultant of the patient vectors in the higher plus the lower prevent relations. The difference between the left and right parts of Figure 2 resides in the strength of the patient vectors in the higher and lower prevent relation, because that strength affects the resulting patient vector, and thereby makes the difference between causation (opposing affector and patient vectors) or enablement (concording affector and patient vectors).

The strength of the patient vectors is grounded in world knowledge or knowledge of the specific situation at hand. In the example ‘Someone allowed the water to flow’, which illustrates the left part of Figure 2, water has a strong tendency to flow, so we posit a long patient vector in the lower prevent relation. However, plugs are fairly inert, so there is a short patient vector for the plug in the higher prevent relation. Composition of these two vectors leads to an enablement relation, where the agent removing the plug concords with the natural tendency of the water to run down the drain. In contrast, the example ‘Lack of water causes plants to die’ illustrates the right part of Figure 2. Plants are resilient, and have a weak tendency to die, so the patient vector in the lower prevent relation in the right part of Figure 2 is short. But if no water can reach the plant, this has a major impact in the long run, so the patient vector in the higher prevent relation is long. As a result of the opposing affector and patient vectors, lack of water is construed as cause of death, rather than a helping hand.

On a psychological level, recognizing a prevent relation involves counterfactual reasoning.[9] As A prevents B means that A causes ¬B, one needs to envision what would happen in the absence of the blocking event. This raises the possibility that the second prevention in a double prevention chain need not actually occur, but may be anticipated, if the early parts in the causal chain make it possible to anticipate the later ones. To test the psychological reality of such virtual forces, Wolff et al. (2010) carried out experiments with closely related animations involving actual and virtual forces. For instance, in one animation a car A approaches a line, a car B approaches the line from the opposite direction and prevents A from crossing the line (actual force). In another animation, car A approaches a line, car B approaches the line from the opposite direction, but stops at the last moment, and A crosses the line. Participants in the experiment describe this animation as ‘B allows A to cross the line.’ Projection of the trajectory of the car beyond its current position leads the participants to construe the absence of B’s blocking A as a virtual force that allows A to cross the line. As Wolff (2014:112) puts it, causation can be based “not only on transmission, but also on removal of an actual force or threat of a virtual preventive force”. It is this intuition that we build on for the conceptual structure of double prevention as the semantics for maha-.

The experiments Wolff and his colleagues carry out reveal the psychological reality of the double prevention relation, but also confirm that English lacks an expression specifically encoding this conceptual structure. This lexical gap is the reason why participants use a range of verbs like enable, cause, help and allow to describe the situations presented to them. The labels correlate with the perception of agent and patient forces in the experimental items as weak or strong, and their interaction as leading to one end state or the opposite one. We hypothesize that Malagasy differs from English in that it has a single lexical expression to describe double prevention, namely maha-. If maha- lexically encodes double prevention, the range of readings that have been associated with maha- in the literature are nothing but attempts to paraphrase that particular configuration in a language like English, which lacks an expression for this conceptual structure. The details are worked out in the following two subsections.

4.4 Conceptual structure and the syntax-semantics interface of maha-

The five core readings of maha- distinguished in the literature are the general ability reading in (28a), the specific ability under adverse conditions (‘manage to’) reading in (28b), the accidental (unintentional) reading in (28c), the enablement reading in (28d), and the causative reading in (28e).[10]

| Mahafaty | osivavy | ny | ambodia. | [general ability] |

| prs-aha-dead | goat | det | wolf |

‘The wolf can kill a goat.’

| Nahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza. | [manage to] |

| pst-aha-catch | dog | det | child |

‘The child managed to catch a dog.’

| Nahapetraka | teo | ambony | tsilo | i | Soa | [unintentionality] |

| pst-aha-sit | pst-loc | on | thorn | det | Soa |

‘Soa sat on a thorn

| Mahatsara | ny | trano | ny | voninkazo. | [enablement] |

| prs-aha-good | det | house | det | flowers |

‘The flowers make the house beautiful.’

| Mahatony | an’ | i | Soa | Rabe. | [causation] |

| prs-aha-calm | acc | det | Soa | Rabe |

‘Rabe makes Soa calm.’

There is a fairly strong tendency for maha- sentences with eventive roots to imply external DPs with animate reference (28a),(28b),(28c), and for stative roots to imply inanimates (28d). But there are exceptions, as seen in (28e), so the five readings do not strictly correlate with animacy. Rather, they depend on the nature of the root, the discourse context in which they appear, and world knowledge shared between speaker and hearer. We rely on the interpretations given for these sentences in the literature to illustrate the various readings, but we do not exclude the possibility that one and the same sentence can give rise to different readings in other contexts (see also discussion in Section 3.2). However, this does not mean that all readings are accessible to all sentences. As previously noted by Phillips (1996, 2000, the general ability, ‘manage to’ and accidental readings appear with eventive roots, whereas the enablement and causative readings arise with stative roots. We qualify the different interpretations as readings that all derive from a unified semantics of double prevention that underlies maha-. The main point of Sections 4.4.1 and 4.4.2 is to show that the interaction of maha- with stative and eventive roots leads to different force-theoretic configurations that correlate with the different readings. We start with the stative roots, and then turn to the analysis of eventive roots.

4.4.1 Stative roots

Enabling and causative readings with stative roots typically rely on the virtual force of absences as the intermediate patient (B). In a default context, we read the conceptual structure of (28d) as follows: the flowers (A) prevent the absence of decoration (B); the absence of decoration (B) prevents the room from looking beautiful (C). Based on world knowledge, we take the room to have a natural tendency towards beauty, and the absence of decoration to have just a weak tendency away from it. Intuitively then, (28d) conveys that flowers are the final touch to reach the end state of beauty. The representation in Figure 3 uses single arrows (→) to represent weak forces, and double arrows (⇒) for strong forces. Grey arrows  visualize that the end state need not be reached. The resultant force R is represented (in red) as

visualize that the end state need not be reached. The resultant force R is represented (in red) as  . Just like in Figure 2, we provide three vector configurations for the higher prevent relation, the lower prevent relation and the conclusion in terms of enablement.

. Just like in Figure 2, we provide three vector configurations for the higher prevent relation, the lower prevent relation and the conclusion in terms of enablement.

Enablement with stative roots.

Similarly, in a neutral context, we assume the conceptual structure of (28e) is as follows: Rabe (A) prevents stress (B), stress (B) prevents Soa from being calm (C), so Rabe makes Soa calm. Figure 4 has the same set-up as Figure 3 in its force-theoretic representation of the two prevent relations, followed by the conclusion in terms of causation.

Causation with stative roots.

In both cases, the B argument remains implicit, and its nature is reconstructed as an affector that prevents the situation described by the stative root to arise for the inner argument (C), and is itself prevented by the external argument A. The most natural interpretation of (28d) is to associate B with lack of decoration, and for (28e) the interpretation of stress suggests itself. Note that both are to be construed as virtual, rather than actual values of B, in line with the counterfactual reasoning that underlies double prevention configurations in general (see Section 4.3 above). Crucially, maha- sentences convey that A is successful in overcoming any difficulties that prevent C from arising, so whichever value B takes up in the context, A prevents B, and enables or causes C to reach the end state E (beauty in (28d), tranquility in (28e)). The formal analysis below accounts for reaching the end state by bringing the variable introduced by the lower prevent relation under the scope of a universal quantifier ranging over alternatives, introduced by the higher prevent relation. The strength of the forces, and the interaction of vectors is dependent on world knowledge and context. Thus one and the same sentence may allow different readings. In other words, any stative root affixed with maha- can in principle be interpreted as involving causation or enablement, but as noted in the discussion of the examples in (16), some readings are more salient than others, depending on the particular root and its arguments.

Now that the conceptual structure of the double prevention configuration in maha- sentences is clear, we can work out the compositional build-up at the syntax-semantics interface. Based on the functional approach to maha- in Section 4.1, and combining the insights of Phillips (1996, 2000, Travis (2010), and Paul et al. (2016), we propose the syntactic structure in (29b) for (28e), repeated here as (29a). In line with Phillips (1996, 2000 and Travis (2010), we take maha- to enrich the argument structure of the verb and create a two-place predicate out of a stative root.[11]

| Mahatony | an’ | i | Soa | Rabe. |

| prs-aha-calm | acc | det | Soa | Rabe |

‘Rabe makes Soa calm.’

|

Semantically, ma- and ha- each contribute a prevent relation and their combination establishes a double prevention relation between the external argument (the affector A), the situation variable of the stative root (C), and an intermediate argument (B) that functions as the patient in the higher prevent relation, and the affector in the lower prevent relation. We work out the compositional semantics in the stepwise derivation in (30). We assign a simple, mono-eventive structure to roots, and take stative roots to denote one-place predicates over states (30b). Ha contributes the lower prevent relation in (30c). Existential quantification over z ensures that that there is something that prevents the state described by the root tony ‘calm’ from arising (30d). Combination with i Soa in (30e) conveys that some (possibly virtual) force prevents Soa from being calm.

| Mahatony | an’ | i | Soa | Rabe. |

| prs-aha-calm | acc | det | Soa | Rabe |

‘Rabe makes Soa calm.’

| [TP [PredP ma [AspP [DP Soa] [AspP’ ha [√ calm]]]] [DP Rabe]] |

| [[tony]] : λyλs[calm(s) & theme(y,s)] |

| [[ha-]]: λPλs[P(s) & ∃z.prevent(z,s)] |

(where P is a stative predicate)

| [[ha-tony]]: λyλs[Calm(s) & theme(y,s) & ∃z.prevent(z,s)] |

| [[ha-tony i Soa]] : λs[calm(s) & theme(Soa,s) & ∃z.prevent(z,s)] |

| [[ma-]]: λP’λxλs[P’(s) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,s) → prevent(x[-ag],z’)]] |

(where P’ is a ha-predicate building on a stative root, with ha- as defined in c)

| [[ma-ha-tony i Soa]] : λxλs[calm(s) & theme(Soa,s) & ∃z.prevent(z,s) & ∀altz’[prevent(z’,s) → prevent(x[-ag],z’)]] |

| [[ma-ha-tony i Soa Rabe ]]: |

| λs[calm(s) & theme(Soa,s) & ∃z.prevent(z,s) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,s) → prevent(Rabe[-ag],z’)]] |

Ma enriches the argument structure, assigns a non-agentive theta role to x, and contributes the higher prevent relation in (30f). As the higher prevent relation is indifferent to the value taken up by the intermediate argument B, which functions as the affector in the lower prevent relation, we take ma- to imply an intensional meaning component. The intended meaning of (30h) is that Rabe prevents whatever actual or virtual stressor that might prevent Soa from being calm in situation s. The paraphrase suggests that the intensional meaning component of ma- is more closely related to English wh-ever phrases than to any, which is typically infelicitous in non-modal, episodic contexts (see Caponigro and Fălăuş (2018) and references therein). Following Jacobson (1995), wh-ever phrases have been analyzed as intensional definites, implying universal quantification over alternative values or descriptions, thus giving rise to ignorance or indifference readings. Quantification over alternatives is either part of a modal component in the truth conditions (Dayal 1998) or the presuppositional content (von Fintel 2008) or implemented in a focus-background structure with appropriate restrictions on the alternatives at stake in the context (Condoravdi 2015). We remain agnostic on the details here, and simply assume a universal quantifier over alternatives (∀alt). We leave the interaction of maha- with modals, quantifiers and appositives that could reveal the exact relations between maha- and free choice items, free relatives and epistemic indefinites in other languages for follow-up empirical research, because we currently lack the relevant empirical date.[12] Combination of ma- with the ha-predicate leads to (30g), and further combination with the external DP to (30h), which conveys that Soa is calm thanks to Rabe’s removal of whatever actual or virtual threats to her state of being calm.

Recall from Section 4.1 that we follow Travis (2010) in associating the external argument introduced by ma- with a non-agentive theta role. The fact that maha- verbs are incompatible with agent-oriented adverbs supports this thematic structure (see (15b)). As we saw in Section 4.3, the force-theoretic framework developed by Wolff is compatible with such non-agentive preventers (including inanimates, virtual forces and absences).

The syntax-semantics interface of (28d) is identical to that of (28e), the difference between enabling and causative maha- with stative roots being handled by the conceptual component, as illustrated in Figures 3 and 4. We now turn to the syntax-semantics interface of maha- with eventive roots, which extends the analysis of stative roots developed so far.

4.4.2 Eventive roots

Before we develop the formal syntax-semantics interface, we lay out the conceptual structure of the double prevention configuration of maha- sentences with eventive roots. We start with the ‘manage to’ reading of (2b) (repeated in (28b) above and (31) below).

| Nahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza. |

| pst-aha-catch | dog | det | child |

‘The child managed to catch a dog.’

In a neutral context, the conceptual structure of (31) is a double prevention configuration in which there is some B that prevents the child from catching the dog (C) - maybe the dog is big and fast, and the child is small in comparison. The higher prevention relation indicates that the child (A) did something to remove the threat B poses to the child catching the dog (maybe the child ran harder than anyone would have expected). The end state is that the child removed the prevention on her catching the dog, in other words, she managed to catch the dog. We characterize this configuration as special ability under adverse conditions, and analyze it conceptually in Figure 5. The ‘manage to’ reading of (31) in Figure 5 mirrors the representation of the causative reading of the stative root (28e) in Figure 4 above: capturing the dog requires a special effort on the side of the child to overcome potential or real difficulties.

The schematic representation of the general ability reading (28a) mirrors the enablement structure of (28d) in Figure 3 above. Malagasy lacks a separate verb ‘to be able to’,[13] and uses a maha- configuration to report general ability, the underlying structure of which is: A has certain features, which entities otherwise similar to A lack, and the lack of these features constitutes the B that prevents C. Figure 6 spells out the conceptual structure of (28a) in force-theoretic terms.

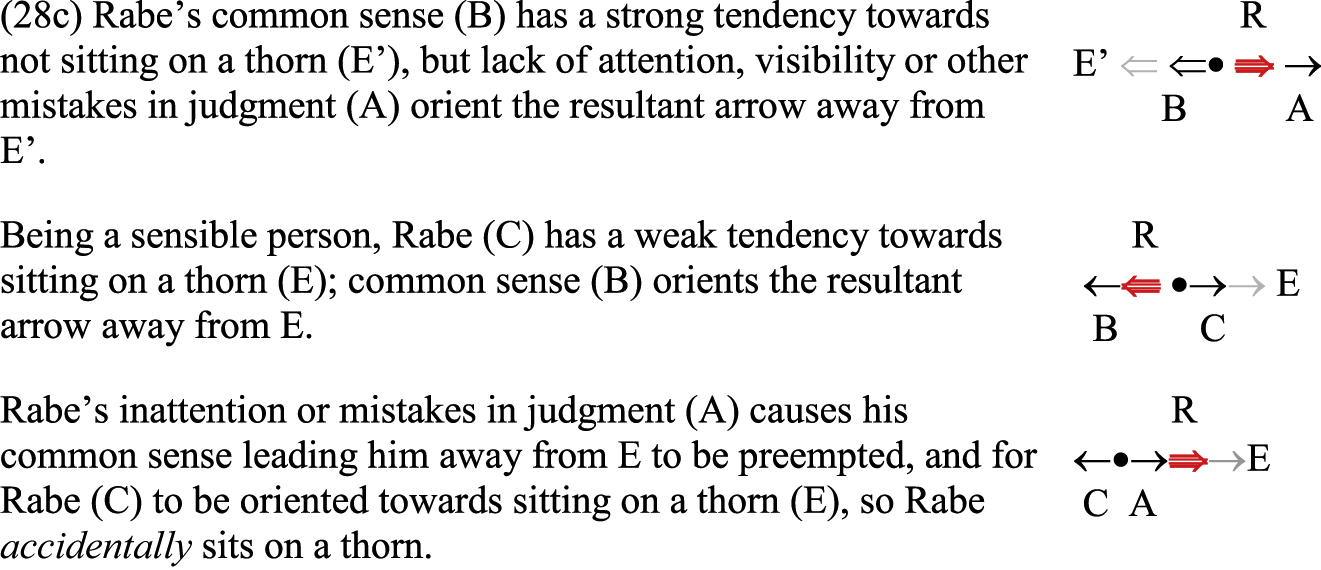

In a neutral context, the most likely reading of (28c) is unintentionality, because we expect Rabe to normally not sit on a thorn, as common sense would guide him towards careful behavior. But in this special case, maybe it was dark, or he wasn’t as attentive as he normally is, so he didn’t notice the thorn, or didn’t identify the object as a thorn, in other words, Rabe missed whatever crucial piece of information that prevented his common sense from preventing him from making a mistake, and as a result, he accidentally sat down on a thorn. The conceptual structure of (28e) in Figure 7 reflects that Rabe’s sitting on a thorn is caused by his own inattention or mistakes in judgment.

The three readings all build on a double prevention relation, but they vary in the force of the patient vector, which leads to different vector configurations, and different paraphrases in English. The ‘manage to’ and accidental readings rely on a causative structure, which implies a strong B vector that A needs to overrule. The general ability reading in contrast relies on a weak B vector and implies an enablement structure. The general ability and unintentional reading share a role for the external argument in the B vector. For the general ability reading, the specific features of the external argument are needed compared to other entities in the same general category (the wolf in contrast to other predators in (28b)), so in a sense, the wolf enables itself to kill the goat. For the accidental reading, the B vector directly implies the common sense of the external argument (Rabe in (28c)), so Rabe caused himself to sit on a thorn. In contrast, the ‘manage to’ reading assigns an important role to characteristics of the inner argument in the B vector (the size and speed of the dog in (31)), so the child overcomes the patient force of the dog and causes the dog to get caught. Interestingly, eventive roots do not lead to an enablement structure whereby the external argument enables the inner argument to be in a certain end state. This configuration is reserved to stative roots, as in the flowers enabling the room to look beautiful. The syntax-semantics interface we work out for the composition of maha- accounts for the unavailability of this configuration, as we will see below.

By way of illustration, we spell out the syntax-semantics interface of the ‘manage to’ reading. The tree in (32b) provides the syntactic structure of (32a).

| Nahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza. |

| pst-aha-catch | dog | det | child |

‘This child managed to catch a dog.’

|

The tree in (32b) is very similar to the one in (29b), so there are essentially no syntactic differences between maha- sentences with stative or eventive roots. The semantic composition is slightly different, though. Recall that the distinction between eventive and stative roots in Malagasy is construed as a contrast between intransitive stative roots and transitive eventive roots. If eventive roots are transitive, they denote a two-place relation between an agent and a theme. As we want to stay as close as possible to the semantics of ma- and ha- as defined in (30), and ha- as defined in (30c) operates on intransitive roots, we turn the eventive root into a one-place predicate (subscripted IV). There are various ways to do that, but we choose Montague’s quantifying-in approach. Informally, the syntax of quantifying-in replaces the Agent role with an indexed pronoun hei. The indexed pronoun binds off the argument slot, just like a regular pronoun would do, so the result of applying hei to the eventive root sambotra is the intransitivized counterpart of the eventive root in (33c). Bare nouns get an indefinite interpretation (Paul 2016), so combination with the inner argument leads to the set of events e such that xi catches the dog in event e (33d). The prefix ha- can now operate on this intransitive root, and adds the lower prevent relation in (33e).

With stative roots, ha- prevents the state denoted by the root from arising, as we saw in (30c) above. With eventive roots, ha- targets the change of state, so it prevents the event e from culminating, written here as Cul(e). As the theme appears as the VP-internal argument in maha-sentences with eventive roots, application of ha- to the VP in (33f) conveys that there is something that prevents the dog from getting caught by xi.

| Nahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza. |

| pst-aha-catch | dog | det | child |

‘The child managed to catch a dog.’

| [S [PredP ma [AspP [DP dog] [AspP ha [√ catch]]]] [DP the child]] |

| [[sambotra]] : λxλyλe[catch(e) & theme(y,e) & agent(x,e)] |

| [[sambotraIV]] : λyλe[catch(e) & theme(y,e) & agent(xi,e)] |

| [[ha-]]: λPλyλe[P(e) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e)) & theme(y,e) & agent(xi,e)] |

(where P is an eventive root)

| [[ha-sambotraIV]]: λyλe[Catch(e) & theme(y,e) & agent(xi,e) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e))] |

| [[ha-sambotraIValika]]: λe∃y[catch(e) & theme(y,e) & dog(y) & agent(xi,e) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e))] |

| [[ma-]]: λPIVλxiλe[P(e) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,Cul(e)) → prevent(xi,z’)]] |

(where P is a ha-predicate based on an eventive root, with ha- as defined in d)

| [[ma-ha-sambotra alika]]: λxiλe∃y[catch(e) & theme(y,e) & dog(y) & agent(xi,e) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e)) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,Cul(e)) →prevent(xi[-ag],z’)]]] |

| [[ma-ha-sambotra alika ny zaza]]: λeιx∃y[catch(e) & theme(y,e) & dog(y) & agent(x,e) & child(x) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e)) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,Cul(e)) → prevent(x[-ag],z’)]]] |

Ma- introduces a higher prevent relation, just like before. But where ma- augmented the argument structure with stative roots in (30f), the application of ma- to an eventive root recycles the indexed variable xi of the eventive root, by lambda abstracting over it (33g). The application to the VP in (33h) shows that quantifying-in identifies the child both as the affector of the higher prevent relation, and as the agent of sambotra. This use of quantifying-in captures Phillips’s intuition that the agent role of the root is realized above ha-, in the specifier of the projection headed by ma-, in our analysis (30b) in the PredP, yet the external argument qualifies as a non-agentive cause. The universal quantifier ∀alt ranges over actual or virtual threats to the culmination of e and ensures that nothing can prevent the event e contributed by the root from culminating. The final representation in (33i) illustrates that the child is not only the one who removes any actual or virtual factors that prevent capture of the dog, it is also necessarily the person achieving the catching.

The differences between the ‘manage to’, general ability and accidental readings we find in (28a-c) reside in the conceptual structures illustrated in Figures 5–7, that arise out of the various double prevention configurations, and depend on the force of patient vectors reflecting the interactions between the inner and outer argument. As a result, the syntax-semantics interface of the three sentences in (28a-c) is exactly the same: in all cases maha- introduces a double prevention configuration where the DP external to the PredP is linked to the Agent role of the event, and removes whatever could prevent the event from culminating.

‘manage to’ reading with eventive roots.

General ability with eventive roots.

Unintentionality with eventive roots.

The analysis in (33) explains why maha- sentences with eventive roots do not lead to an enablement structure whereby the external argument enables the inner argument to be in a certain end state, in a way that we find it with stative roots (see Figure 3). In other words, (33) does not mean ‘This child enabled the dog to be caught’. The enablement configuration does not identify the affector of the higher prevent relation with the Agent role of e, so the missing reading supports the recycling of xi by the application of ma- in (33g).

4.5 Implications of the double prevention relation for culmination

Sections 4.4.1 and 4.4.2 together provide the conceptual structure and compositional semantics of maha- and illustrate how ha- and ma- interact with stative and eventive roots in slightly different ways, because of the differences in argument structure, and the contrast between states and events. At the same time, ma- and ha- share a common core: in both cases, ha- introduces the lower prevent relation, and ma- the higher one.

The higher prevent relation implies a universal quantifier over alternatives (∀alt). As we noted in Section 4.4 above, follow-up research is needed to fine-tune the restrictions on alternatives, but we can already provide one ingredient. Quantification over possible worlds obviously requires interpretation with respect to a conversational background, and the quantificational component of maha- necessarily relies on a circumstantial modal base: whether they report on actual or virtual forces, the two prevent relations imply possibilities that fit into the normal development of the real world. In that sense, maha- is different from other modal verbs in Malagasy, which, just like their English counterparts, vary in modal base depending on the conversational background relevant in the context.[14] The examples below illustrate these readings for tsy maintsy ‘must’ (data from Rajaona (1972:322)).

| Tsy maintsy | hajaina | ny | ray | aman-dreny. | [deontic] |

| must | tt-respect | det | father | with-mother.3 |

‘One’s parents must be respected.’

| Tsy maintsy | mianjera | io | trano | io | fa | mivava. | [epistemic] |

| must | prs-at-fall | dem | house | dem | comp | prs-at-crack |

‘This house must fall down because it is cracked.’

In sum, maha- has an intensional meaning component, because it takes into account virtual forces, and includes a universal quantifier over alternatives. Yet it does not qualify as a modal verb, per se, rather, the modal meaning directly falls out from the double prevention configuration and does not allow for variation in conversational background - it necessarily implies a circumstantial modal base.

Building on Matthewson (2012) and Martin and Schäfer (2012), Paul et al. (2015, 2016 identify the circumstantial modal base as a key ingredient of maha-’s potential to induce culmination: if culmination with eventive roots holds in all possible worlds in the modal base, and the set of possible worlds quantified over includes the real world, as is the case with a circumstantial modal base, culmination is enforced by assertion of the event. We will show now that this explains why maha- sentences in the past tense entail culmination, as illustrated by (35) (repeated from (2b)):

| Nahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza | # | nefa | faingana | loatra | ilay | alika |

| pst-aha-catch | dog | det | child | but | fast | too | def | dog | |

| ka | tsy | azony. | |||||||

| comp | neg | do-3 |

‘The child managed to catch a dog #but it was too fast, so it didn’t get caught by him.’

In line with standard assumptions in the literature on tense and aspect, we assume that the past tense operator introduces a reference interval r preceding the speech time now (r < now). According to Paul et al. (2015, 2016, Malagasy does not encode grammatical distinctions like perfective/imperfective in its grammar, so we follow the conclusion we reached there, which is that lexical aspect (also called Aktionsart or situational class) drives the anchoring of stative and eventive roots to the time axis. Following standard assumptions in the literature on aspect, we take events to be included in the reference time r (e ⊆ r), while states include the reference time (r ⊆ s). Putting these assumptions together explains the pattern in (35), as worked out in (36).

The compositional semantics of (28b) is spelled out in (33) above. We repeat the last step of (33i) in (36a). Application of the past tense operator completes the derivation and leads to the final interpretation in (36b):

| Nahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza. |

| pst-aha-catch | dog | det | child |

‘The child managed to catch the dog.’

| [[ma-ha-sambotra alika ny zaza]]: λeιx∃y[catch(e) & theme(y,e) & dog(y) & agent(x,e) & child(x) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e)) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,Cul(e)) → prevent(x[-ag],z’)]]] |

| [[na-ha-sambotra alika ny zaza]]: ∃e∃rιx∃y[catch(e) & r < now & e ⊆ r & |

| theme(y,e) & dog(y) & agent(x,e) & child(x) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e)) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,Cul(e)) → prevent(x[-ag],z’)]]] |

Maha- encodes that the child is successful in removing everything and anything that could prevent her from catching the dog (36a). The past tense operator induces existential closure over the event variable e and places this event at a time before the speech time (36b). As the event is located in the past, and a circumstantial modal base ranging over realistic possibilities in the real world underlies the double prevention configuration operating on e, culmination of e is entailed for a maha- sentence implying an eventive root in the past tense.

Example (19) in Section 3.3, repeated here as (37) illustrates that maha- has the same culminating effect in the future tense. The main problem with the future is lack of epistemic access, which has led to many different formal analyses (temporal, modal, and a mixture of temporal and modal reference). Modulo epistemic fine-tuning, sentences like (19) should get the semantics in (37) with the projection of r at a time later than the speech time.

| Hahatitra | sakafo | ho | an’ ny | reniny | i | Be |

| fut-aha-send | food | acc | det | mother.3 | det | Be |

| # fa | tsy | ho | raisiny | ilaysakafo. | ||

| comp | neg | fut | receive-3 | def food |

‘Be will be able to send food to his mother but she won’t receive the food.’

| [[ha-ha-titra sakafo ho an’ny reniny i]]: λe∃y[send(e) & theme(y,e) & food(y) & |

| agent(Be,e) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e)) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,Cul(e)) → prevent(Be,z’)]]] |

| [[ha-ha-titra sakafo ho an’ny reniny i Be]]: ∃e∃r∃y[send(e) & now < r & e ⊆ r & |

| theme(y,e) & food (y) & agent(Be,e) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e)) & |

| ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,Cul(e)) → prevent(Be,z’)]]] |

As the agent prevents anything standing in the way between him and the result state, a proper epistemic embedding of the condition now < r should allow us to project reaching of the result state in the future.

As we have just seen, maha- always induces culmination in the past and future tenses, but not necessarily in the present tense. For present tense sentences, the distinction between stative and eventive roots comes into play. Following standard assumptions in the literature, we take the present tense operator to include the speech time in the reference interval (now ⊆ r). For stative roots, we illustrate with (28e), repeated here as (38). The compositional semantics of (28e) is spelled out in (30) above. (38a) repeats the final step (30h); adding the tense operator leads to the final interpretation in (38b):

| Mahatony | an’ | i | Soa | Rabe. |

| prs-aha-calm | acc | det | Soa | Rabe |

‘Rabe makes Soa calm.’

| [[ma-hatony an’i Soa Rabe ]]: λs[calm(s) & theme(Soa,s) & ∃z.prevent(z,s) & |

| ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,s) → prevent(Rabe,z’)]] |

| [[ma-hatony an’i Soa Rabe ]]: ∃s∃r[calm(s) & now ⊆ r & r ⊆ s & theme(Soa,s) |

| & ∃z.prevent(z,s) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,s) → prevent(Rabe,z’)]] |

Interpretation of the present tense operator induces existential closure over the state variable s. As s includes r, and r includes now, the state s of Soa being calm holds at the speech time. Maha- does not play a role in inducing culmination, because states just hold, they don’t culminate.

Lack of culmination with eventive roots in present tense maha- sentences precludes ‘manage to’ and unintentional readings, and leads to general ability and dispositional readings, as we saw in relation to (17) and (18) in Section 3. Similarly, the present tense counterpart of (36) in (39) states that the child has the ability to catch a dog, and does not entail that he has done so. The event structure in (36a), repeated in (39b) provides us with the set of events such that the child removes anything that could prevent her from successfully catching the dog.

| Mahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza. |

| prs-aha-catch | dog | det | child |

‘The child can catch a dog.’

| [[ma-ha-sambotra alika ny zaza]]: |

| λeιx∃y[catch(e) & theme(y,e) & dog(y) & agent(x,e) & child(x) & |

| ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e)) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,Cul(e)) → prevent(x[-ag],z’)]]] |

In contrast to (37a), which leads to (37b) in a straightforward application of the present tense operator, (39a) is not the right input for the present tense operator: the present is not aspectually neutral, the way the past and future operators are. Comrie (1976) drew the typological generalization that (simple) present tenses are never perfective, but always imperfective. A reformulation of the generalization in terms of lexical aspect states that accomplishments and achievements cannot be located at the speech time, only states and processes can. In English, this restriction is reflected in the infelicity of sentences like (40a), in contrast to either the progressive (40b) or the stative (40d). Habitual/dispositional readings arise in present tense sentences implying middles (40e), but also without special morphosyntactic marking (40f).

| #This child catches a dog. |

| The child is catching a dog. |

| L’enfant attrape un chien. |

| The child is able to catch a dog. |

| This glass breaks easily. |

| Mary sorts the mail coming from Antarctica. |

In languages without a grammaticalized progressive, simple present tense sentences with accomplishments are generally not ungrammatical, but shift their meaning to the imperfective reading that English captures by the progressive (40b) or to dispositional/ability readings along the lines of (40e,f). French (40c) for example, is not infelicitous, unlike English (40a), as it conveys the progressive reading without the explicit morphosyntactic marking we see in English (40b). We hypothesize that the different aspectual meaning shifts triggered by the combination of present tense and eventive roots that describe culminating events correlate with different voice markers in Malagasy. Present tense sentences in AT typically describe ongoing events (what Rajaona (1972) calls “durative”), as illustrated in (41):[15]

| Misambotra | alika | ny | zaza. |

| prs-at-catch | dog | det | child |

‘The child is catching a dog.’

Malagasy AT resembles French (40c) in that the shift to an imperfective reading is not expressed through overt morphology on the verb, but arises out of the conflict between present tense and eventive verbs. But (41) resembles English (40b), and differs from French (40c) in that it does not have a dispositional/ability reading. We take this to be a blocking effect: multiple grammatical options induce a division of labor between forms and meanings. The English grammar formalizes the contrast between ongoing event reading (progressive verb forms) and other shifted readings. Malagasy exploits the double prevention semantics to establish a contrast between dispositional/ability readings (conveyed by maha-) and other imperfective readings. We know from Section 4.4.2 that self-enablement is one of the possible interpretations of maha- with eventive roots. As this is the only aspectual meaning shift that is compatible with the lexical semantics of maha-, other readings must be conveyed through other voice markers. Conversely, the overt marking of enablement through maha- blocks the dispositional/ability reading for AT voice markers, as in (41). We set aside for future research an in-depth discussion of non-culmination with the other voice markers. We refer the interested reader to Beavers and Lee (this volume) for one approach.

Returning to present tense maha- sentences like (39), we propose that dispositional sentences are intensional, just like generics and habituals, so their semantics is inherently modal. Building on Dahl (1975), Menendez-Benito (2005) analyzes dispositional sentences in terms of possibilities, i.e., existential quantification over possible worlds. The dispositional reading of (39) then reads as ‘there is an alternative possible world compatible with the child’s features in which she catches a dog’. The possibility reading does not require that the child has ever caught a dog in the real world so far, so the dispositional reading is weaker than the habitual/pluractional reading of (41) referred to in footnote 15 (which would require the child to have caught a dog at least once). However, not just any accidental circumstances under which the dog is caught qualify as support for the dispositional reading. As Menendez-Benito argues, the dispositional reading requires a circumstantial modal base that takes into account inner dispositions or ‘mental programming’ of the subject rather than outside circumstances. The formal details of the dispositional reading are beyond the scope of this paper, so we simply represent it as ⋄, and refer to Menendez-Benito (2005) for further discussion. In order to allow the present tense operator to anchor the dispositional reading to the time axis, we take it to trigger a shift from events to states s in which the disposition for e holds, as spelled out in (42b).

| Mahasambotra | alika | ny | zaza |

| prs-aha-catch | dog | det | child |

‘The child can catch a dog.’

| [[Ma-ha-sambotra alika ny zaza]]: ∃sιx [now ⊆ r & r ⊆ s & child(x) & |

| s: ⋄∃e∃y[catch(e) & theme(y,e) & dog(y) & agent(x,e) & ∃z.prevent(z,Cul(e)) & ∀ALTz’[prevent(z’,Cul(e)) → prevent(x[-Ag],z’)]]] |

In words, (42b) states that there is a possible world in which the child removes whatever prevents her from successfully catching a dog. In this possible world, the event culminates (the dog is caught), but the possibility operator ensures that culmination is not necessarily entailed in the real world. Against a circumstantial modal base that takes into account the inner dispositions of the child, the sentence means that the child has the ability to catch a dog.

In sum, anchoring to the time axis always leads to culmination in past and future tense sentences, because the circumstantial modal base associated with the double prevention configuration ensures that the end state is reached in all worlds in the conversational background, which includes the real world. Present tense maha- sentences with stative roots assert that the state holds at the speech time, while their counterparts with eventive roots shift to a general ability or dispositional reading, asserting that there is a possible world compatible with the agent’s features in which the event culminates. ‘Manage to’ and unintentional readings are restricted to past/future sentences, which entail event culmination.

Summing up, we have developed in this section an analysis that, following Phillips and Travis is grounded in the morphological complexity of maha-. Semantically, ma- and ha- each introduce a prevention relation, its composition leading to a double prevention configuration. With stative roots, maha- adds an extra argument, which gives rise to causative and enablement conceptual structures. With eventive roots, maha- recycles the external argument of the root, effectively identifying the affector of the higher prevent relation with the agent role of the event. Depending on the conceptual interaction of the affector and patient forces, this leads to the ‘manage to’, the unintentional, a general ability or a dispositional reading.

5 Conclusion

The literature on non-culminating accomplishments tends to focus on how to derive the absence of culmination. In Malagasy, culmination is sensitive to the voice marker. Basic AT and TT voice sentences implicate, but do not entail culmination, so non-culminating accomplishment readings are available in most contexts. For the morphologically complex voice marker maha-, we have argued that culmination falls out of its semantics, at least in past and future sentences. We follow Phillips (1996, 2000 and Travis (2010), who defend the morphological complexity of maha-, and propose that ma- and ha- each introduce a prevention relation. This double prevention configuration interacts with the type of root (stative or eventive) to give rise to the various readings observed in the literature. The embedding of the double prevention configuration in a force-theoretic framework allows us to deal with the flexibility of interpretation: many sentences allow different interpretations, depending on world knowledge and discourse context.

Through the association of the double prevention configuration with a circumstantial base, the culminating reading of past and future sentences with eventive roots arises naturally from this approach, as does the absence of culmination when maha- occurs in the present tense. Many past approaches have attempted to link maha- to resultativity (Rajaona 1972) or telicity (Phillips 1996, 2000; Travis 2010), but the more indirect link through double prevention provides a more insightful explanation of the culmination effects where they occur (and don’t occur). In addition, this paper supports the linguistic need for a more fine-grained theory of causation and argues that a force-theoretic framework yields new solutions for complex empirical puzzles in underdescribed languages that have a different set of grammatical categories than English, in the case of Malagasy: a richer set of voice markers.

Turning now to the broader typological perspective, we can ask how Malagasy patterns with other languages. We will not enter into a detailed discussion here, but Malagasy is strikingly similar to Tagalog (another Austronesian language; see Dell (1983) and Kroeger (1993)) as well as some of the Salish languages in terms of morphology (a dedicated marker for culmination) and interpretation (the same cluster of “out of control” readings). Does Malagasy provide support for the Agent Control Hypothesis of Demirdache and Martin (2015)? Perhaps indirectly, given that culmination is so closely tied to the absence of agentivity. Whether the converse is true (agentivity is required for non-culmination) remains to be determined.

Looking ahead, Malagasy has other means to mark culmination (e.g., via the “passive” prefixes voa- and tafa- discussed by Travis (2010)) but it remains to be seen whether these affixes can be analyzed in similar ways as maha-.

References

Baglini, Rebekah & Itamar Francez. 2016. The implications of managing. Journal of Semantics 33. 541–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffv007.Search in Google Scholar

Bar-el, Leora, Henry Davis & Lisa Matthewson. 2005. On non-culminating accomplishments. In Leah Bateman & Cherlon Ussery (eds.), Proceedings of NELS, vol. 35, 87–102. Amherst, MA: GLSA.Search in Google Scholar

Bhatt, Rajesh. 1999. Ability modals and their actuality entailments. In Proceedings of WCCFL 17, 74–87. Stanford: CSLI Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Caponigro, Ivano & Anamaria Fălăuş. 2018. Free choice free relative clauses in Italian and Romanian. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 36. 323–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9375-y.Search in Google Scholar

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Condoravdi, Cleo. 2015. Ignorance, indifference, and individuation with wh-ever. In Luis Alonso-Ovalle & Paula Menéndez-Benito (eds.), Epistemic indefinites, 213–243: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665297.003.0010Search in Google Scholar

Copley, Bridget & Phillip Wolff. 2014. Theories of causation should inform linguistic theory and vice versa. In Bridget Copley & Fabienne Martin (eds.), Causation in grammatical structures, 11–57. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199672073.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

Dahl, Östen. 1975. On generics. In Ed Keenan (ed.), Formal semantics of natural language, 99–112. London: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511897696.009Search in Google Scholar

Davis, Henry, Lisa Matthewson & Hotze Rullmann. 2009. ‘‘Out of control’’ marking as circumstantial modality in St’át’imcets. In Lotte Hogeweg, Helen de Hoop & Andrej Malchukov (eds.), Cross-linguistic semantics of tense, aspect, and modality, 205–244. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.148.09davSearch in Google Scholar

Dayal, Veneeta. 1998. Any as inherently modal. Linguistics and Philosophy 21. 433–476. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005494000753.10.1023/A:1005494000753Search in Google Scholar

Dell, François. 1983/1984. An aspectual distinction in Tagalog. Oceanic Linguistics 22/23. 175–206. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20172314.Search in Google Scholar

Demirdache, Hamida & Fabienne Martin. 2015. Agent control over non culminating events. In Elisa Barrajón López, José Luis Cifuentes Honrubia & Susana Rodriguez Rosique (eds.), Verb classes and aspect, 185–217. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/ivitra.9.09demSearch in Google Scholar