Abstract

The dative in Hebrew poses a problem for a unified characterization as no single criterion seems to guides its interpretation. The present paper approaches this problem from a usage-based perspective, suggesting a multifactorial account of dative functions in Hebrew. Analyzing a corpus of Hebrew dative clauses with multivariate statistical tools I reveal the usage patterns associated with each dative function, showing that traditional descriptions of dative functions are not reflected in usage. Working within a Usage-Based perspective, in which the meaning of a word is its use in language, I argue that Hebrew has only four distinct dative usage patterns, termed Discourse Profile Constructions: conventional correspondences between a multifactorial usage pattern and a unified conceptualization of the world. The four Discourse Profile Constructions are: (i) the Extended Transitive Discourse Profile Construction, (ii) the Human Endpoint Discourse Profile Construction, (iii) the Extended Intransitive Discourse Profile Construction, and (iv), the Evaluative Reference point Discourse Profile Construction. By revealing such correspondences between usage patterns and conceptualizations, the present paper (i) broadens the Construction Grammar notion of Argument Structure Construction, and (ii), suggests an innovative account for the notion of usage as a factor in the conventional pairing between form and function.

1 Introduction

The dative in Hebrew poses a problem for a unified linguistic characterization, since there seems to be no single criterion which can guide its interpretation. Considering lexical semantics or syntax in isolation, no rule can be given according to which a dative marked nominal can be assigned a participant role. The present paper approaches this problem from a usage-based perspective. Analyzing a corpus of Hebrew dative clauses with multivariate statistical tools I reveal the usage patterns associated with each dative function. I show that traditional descriptions of more than nine dative functions are not reflected in usage. To the extent that the meaning of a word is its use in context (Wittgenstein 1953), I argue that from a usage-based perspective, Hebrew has only four distinct dative usage patterns. These patterns are termed Discourse Profile Constructions: conventional correspondences between a multifactorial usage pattern and a unified conceptualization of the world, i.e. a particular construal of a state of affairs. The four Discourse Profile Constructions are: (i) the Extended Transitive Discourse Profile Construction, (ii) the Human Endpoint Discourse Profile Construction, (iii) the Extended Intransitive Discourse Profile Construction, and (iv), the Evaluative Reference point Discourse Profile Construction. Each Discourse Profile Construction is argued for in a bottom-up manner, using a statistical analysis that reveals hidden patterns in the data.

The present paper follows recent work in cognitive semantics which emphasizes the probabilistic nature of polysemic lexical items, embedding such concepts as radial networks and prototype models in a quantitative analysis (e.g. Dattner 2015a; Divjak and Fieller 2014; Geeraerts 2010; Glynn 2010; Robinson 2014; Levshina, Geeraerts and Speelman 2013). Accounting for a polysemic grammatical item, the dative, I suggest the Discourse Profile Construction Hypothesis, according to which the dative-marked participant role varies as a function of multiple parameters simultaneously, all in the service of a discursive-communicative need. In that I follow functional and cognitive approaches to language that assume form to be driven by meaning. That is, I take distinguishable formal usage patterns to reflect distinguishable meanings.

The notion of Discourse Profile Construction is related to the Construction Grammar notion of Argument Structure Construction (Goldberg 1995; Perek 2015). Argument Structure Constructions are special constructions in Construction Grammar terms, which account for the form-meaning pairings in the language that concern schematic clausal expression, rather than fully or partially fixed constructions such as idioms or prefabs. One claim about Argument Structure Constructions is of critical importance for the definition of Discourse Profile Constructions, that simple clause constructions are associated with construals of basic human experience (Goldberg 1995). In the account of Hebrew dative constructions advocated in the present paper I show that on top of basic event types, we can approach Argument Structure Constructions from a usage-based, discursive point of view, broadening Argument Structure Constructions to include discursive functions as well, and emphasizing the existence of basic discursive scenarios. Thus, the Discourse Profile Construction is an extension of the Argument Structure Construction in that it takes into consideration multiple sources of information: lexical, morphological, syntactic, semantic, and discursive, as well as statistical information such as frequency and co-occurrence, embedding it in an exemplar-based model. Doing that, the Discourse Profile Construction provides the basis for the usage conditions conventionally linked to basic event structures.

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, I present the focus of the paper, dative clauses, and the problems in differentiating the dative’s functions and in explaining its usage in terms of isolated parameters. Then I introduce the database for the present research and the method used to analyze it. Next, I report on the results of a corpus analysis of Hebrew dative constructions, arguing that a unified account can be achieved only within a bottom-up, usage-based perspective that takes into account multifactorial usage patterns rather than isolated parameters or particular semantic roles. Finally, I propose the new theoretical concept of Discourse Profile Constructions: unique multifactorial usage patterns that cluster similar tokens together, conventionally linking them with particular functions.

2 Dative-marked participant roles

The dative, like other grammatical cases, construes a relation between a state of affairs (an event or a state) and a referent. It is a tool provided by the language for the speaker to portray how a specific situation is related to an entity in the world. Specifically, the dative marks indirect relations. Such indirect relations may profile an indirectly or partially affected participant in an event, and it may also profile a secondary, non-inherent participant construal in which the dative-marked participant is mildly affected (or not affected at all). This construal is characterized with low transitivity parameters; the dative-marked participant in a situation is usually cognitively (rather than physically) involved.

But the dative is a morpheme of many faces. There are different kinds of indirect relations, all marked by the same dative form (Van Belle and Langendonck 1996; Haspelmath 2001). For example, the Recipient function, often marked by the dative, profiles an indirect participant of a transitive motion event, in which an Agent moves an Object towards the Recipient (Van Langendonck and Van Belle 1998). Another instantiation of a dative-marked indirect participant is the Evaluative Reference Point of a situation. It marks a human reference point against which a certain state of affairs is being evaluated, as in (1):[1]

| meod | xashuv | lanu | she-ha-universita | o | ha-mixlala | tihye | mexuyevet | l-a-inyan. |

| very | important | to.us | that-the-university | or | the-college | will be | obligated | to-the-issue. |

‘It’s very important for us that the university or the college will be obligated to the issue.

The state of affairs of ‘the university being obligated to the issue’ is evaluated as important with respect to the dative’s referent judgment. The same state of affairs, appearing in a non-dative construction, is evaluated as objectively important, with respect to no specific reference point, as in the following constructed example:

| meod | xashuv | she-ha-universita | o | ha-mixlala | tihye | mexuyevet | l-a-inyan. |

| very | important | that-the-university | or | the-college | will be | obligated | to-the-issue. |

‘It’s very important that the university or the college will be obligated to the issue.

It is the dative construction (1) which renders the ‘importance’ judgment subjective, relative to the dative-marked reference point.

The dative case has several recurrent functions in language after language, together with a set of language-specific functions. Dative marked participants are related to certain types of verbs cross-linguistically: possession, existence, psychological states, visual or auditory perceptions, modal states of necessity, wanting, potentiality, and uncontrolled events (Shibatani 2001). The typical dative functions one can find in the literature are Direction, Recipient, Experiencer, Purpose, Possessor, and Beneficiary (e.g. Haspelmath 2003). Many have studied and explored the functions marked by the dative. For the most part, the dative research aims at defining its core meaning. This definition, however, is as versatile as the papers trying to articulate it. For example, listing the uses of the dative in Hebrew, Berman (1982) concludes that they all share a single basic quality of marking an Affectee. Givón (2001), defining the main semantic roles in language, describes the dative participant as “a conscious participant in the event, typically animate, but not the deliberate initiator” (p.107). Recently, Halevy (2016) claimed the basic function of the dative in Hebrew to be a Recipient. The Recipient is the prototypical dative function according to Haspelmath (2003) as well, who defines the dative using a typological semantic map. Berman’s Affectee would thus be an extension to the prototype, according to Haspelmath. Da̧browska (1994); Da̧browska (1997), working within a cognitive linguistic framework, defines the Polish dative as a Target Person: “an individual who is perceived as affected by a change, activity, or state in his or her personal sphere” (Da̧browska 1994:110). In Japanese, Kishimoto (2010) concludes that the semantic basis of dative marking is Possession. Van Belle and Langendonck (1996) and Van Langendonck and Van Belle (1998) are two major sources for dative studies in a typological perspective, providing many different definitions and describing various behavioral properties of the dative in many languages: Latin, French, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Dutch, Afrikaans, English, Polish, Pashto, and Orizaba Nahuatl. Considering the amount of research presented in these two seminal volumes, no single conclusion can be drawn with regard to a unified definition of ‘The Dative.’

Another line of studies is focused on particular functions of the dative, aiming at typological descriptions, syntactic-semantic conclusions, or lexical-semantics generalizations. These include, for example, Amritavalli (2004); Ariel, Dattner, Bois and Linzen (2015); Blume (1998); Cuervo (2003); Francez (2006); Halevy (2007); Hole, Meinunger and Abraham (2006); Linzen (2016); Levin (2008); Sridhar (1979); Šar\’ıc (2002). But again, no unified conclusion can be drawn based on the different views these papers present. Rather, one crucial problem governs the attempts to define a basic, prototypical, dative function, on the one hand, and discussing different functions on the other: The theoretical decision regarding particular dative functions is highly subjective, and taking into consideration that very few of these works are based on corpus data, the nature of grammatical judgments most of these works are based on is fluid and debatable. And moreover, even when grounded on truth conditional semantics, or formal syntactic structure (Bar-Asher Siegal and Boneh 2014; Borer and Grodzinsky 1986), grammatical judgments remain subjective and the interpretation of the dative’s function is questionable. As a consequence, different judgments and different theoretical frameworks lead to utterly different descriptions of basically the same phenomena.

The uniform marking of different types of participants raises two questions. First, how are these different types of relations related to each other (see Boneh and Bar-Asher Siegal (2014) for a recent attempt to answer this question). Second, how are these types differentiated by the speaker/hearer, if differentiated at all. That is, when a speaker utters a clause with a dative marked noun phrase, what interpretation strategy is expected from the hearer in order to attribute the dative-marked participant its right role in the construed situation?

Addressing the problem of the researcher’s choosing the appropriate dative function, and moreover of the hearer interpreting the relevant participant role, consider the the following sentences:

| shalaxti | lo | mixtav | she-oto | ash’ir | laxem | kan. |

| I.sent | to.him | letter | that-it | I.leave | to.you | here. |

‘I sent him a letter which I leave here for you.’

| ani | mash’ir | lahem | lehacig | et | ha-ta’arix | shelahem. |

| I | leave | to.them | to present | acc | the-date | their. |

‘I leave it for them to say when they’ll do it.’

| bou | nizkor | she-nish’aru | laxem | reservot | me-ha-shana | sh-avra. |

| come | remember | that-were.left | to.you | extras | from-the-year | that-pass. |

‘Let’s not forget that you have some extras left from last year.’

While (2a)–(2c) share the same verb, the dative function seems not to be identical in each of the sentences, such that the decision regarding the specific function is not straightforward and may lead to a subjective research decision, or to different interpretation by different hearers: The dative in (2a) may be interpreted either as the Recipient of the letter, or as a Beneficiary of the leaving-the-letter event. The dative in (2b), although related to the same predicate, can be interpreted as an Enabled Person, but not as a Recipient or Beneficiary of any kind. And in (2c) the dative can be interpreted as (i) the Possessor of the extras, (ii) as the Beneficiary of the state of affairs in which there are extras, or (iii) as the Recipient of the said extras. The following sentence raises the same problem:

| tnu | lanu | beynataym | latet | lahem | darga | zmanit. |

| give | to.us | meanwhile | to.give | to.them | position | temporary. |

‘For now, letusgivethem a temporary position’ (Lit. give to us to give to them).

While the same verb is repeated twice in (3), the dative-marked participant role is different in each occurrence. It is an Enabled/Allowed participant in the first occurrence, and a Recipient in the second.

Trying to define a unified principle according to which such dative functions (or other polysemic grammatical constructs) can be distinguished, two hypotheses might be considered: a lexical one, and a syntactic one. These two hypotheses are known as two approaches to argument realization: the projectionist and the constructional, respectively (Croft 2003; Perek 2015). Projectionist approaches argue that argument realization is a projection of lexical requirements. These are verb-centric approaches: argument realization is explained with regard to the verbs exclusively, and all aspects of the form and function of the clause are derived from lexical-verbal information (e.g. Levin and Rappaport Hovav 2005; Müller and Wechsler 2014a; Müller and Wechsler 2014b). On the other hand, constructional approaches argue that while lexical information plays a role, it is not enough to explain argument realization. Constructional approaches (e.g. Goldberg 1995; Perek 2015) go beyond the verb’s lexical semantics and emphasize the information contributed by Argument Structure Constructions: symbolic structural units that can be combined with verbs on the basis of some semantic restrictions.

Regarding the dative-marked participant, a projectionist-lexical hypothesis would argue that its role varies as a function of the predicate it is related to. The validity of this argument can be assessed using examples sharing the same verb, yet evoking different dative interpretations, such as (2)–(3) above, and the following (4)–(5):

| hu | ba | li | be-eyzo | amira | klalit. |

| he | comes | to.me | in-some | saying | general. |

‘He says some general comment to me.’

| mamash | lo | ba | li | she-hu | yavo | im | ha-emda | ha-kodemet. |

| really | not | comes | to.me | that-he | will.come | with | the-position | the-previous. |

‘I really don’t want him to come and present his previous position.’

| hu | arax | lahem | et | ha-shulxan. |

| he | set | to.them | acc | the-table. |

‘He set the table for them.’

| ein | mi | she-yaarox | lahem | xatuna. |

| there.is.no | who | that-will.set | to.them | wedding. |

‘There’s no one that’ll marry them.’

In both (4) and (5), and in (3) above, we see sentences sharing the same verb, while the interpretation of the dative-marked participant is different in each case. The sentences in (4) share the same verb (ba, come), but present different dative functions: Addressee (4a), and Experiencer (4b). And the same is true for (5), in which the dative-marked participant complementing the verb laarox, ‘to set’, is interpreted as a Beneficiary in (5b) of the complete event of ‘setting the table’, but as the only Endpoint of the event ‘marrying’, which is marked as a human. This role is known in the literature as the Human Endpoint (Langendonck 1998).

Based on these examples, we may conclude that a pure lexical hypothesis is not sufficient (and see Perek (2015) for a thorough review of projectionist approaches and their disadvantages). However, notice that while the datives in (3) and in (4a)–(4b) complement the same verbs, the syntactic structures of each sentence is different:

| [Verb | NP | Clause | [Verb | NP | NP] |

| [NP | Verb | NP | PP] |

| [Verb | NP | Clause] |

Thus, abandoning the lexically-based hypothesis, we may ask whether a syntactically-based hypothesis is appropriate, such that the dative-marked participant role varies as a function of the Argument Structure Construction it is a part of (e.g. Goldberg (1995); Perek (2015), and see Dattner (2008) for an account of the non-lexical dative in (4b)).

The Argument Structure Construction hyopthesis could be questioned by examining a number of sentences consisting of the same syntactic structure but presenting different dative functions. Consider in this respect the syntactic structure in (6), manifested in the sentences in (7):

| [Verb | NP | NP |

| lo | nimsera | lanu | shum | hoda’a | rishmit. |

| not | delivered | to.us | no | message | official. |

‘No official notice was given us.’

| hem | yihyu | be-kesher | yashir | im | ovedet | socialit | ve-likrat | shixrur | tibane | lahem | toxnit. |

| they | will.be | in-contact | direct | with | social | worker | and-toward | release | will.be.built | for.them | [a]program. |

‘They’ll be in touch with a social worker, and right before they’ll be released a program will be built for them.’

| behexlet | magia | lexa | zxut-haxaput. |

| definitely | arrives.3.fm | to.you | presumption-of-innocence.fm. |

‘You definitely deserve the presumption of innocence.’

| im | […] | tazin | et | shmo | shel | xaver | ha-knesset | tofia | lexa | kol | reshimat | ha-xukim shel | oto | xaver | knesset. |

| if | […] | you.will.input | acc | name | of | member | the-knesset | will.appear.3.fm | to.youall | list.of.fm | the-laws | of | this | member | knesset. |

‘If you’ll input the name of the member of the Knesset (in the right box) you’ll get his entire list of legislation.’

Although the sentences in (7) all share the syntactic structure presented in (6), the functions of their dative-marked participants seem to be different: The dative in (7a) may be interpreted as a Recipient in traditional terms, in (7b) as a Beneficiary, in (7c) as an Experiencer, and in (7d) as either an Experiencer, or as what might be termed an Ethical Dative. While constructionist approaches allow for constructional polysemy (as discussed in Goldberg and Jackendoff 2004, for example), the variety of functions presented in (7) cannot be so explained. Constructional polysemy implies the existence of a central (prototypical) meaning from which other meanings can be derived (Perek 2014). The derivation link that can be detected between the Beneficiary and the Recipient in (7a)–(7b) may be extended to the Experiencer in (7c), thus suggesting a polysemic account. However, such a polysemic analysis would struggle to reveal a derivation link leading to the Experiencer/Ethical Dative in (7d). Thus, while promising indeed, it seems that the Argument Structure Construction hypothesis regarding the Hebrew dative needs further fine-tuning due to the lack of a singular link between a dative function (albeit a polysemic one) and a syntactic construction, as presented in (7a)–(7d). The Discourse Profile Constructions approach advocated in the present paper is an extension of the Argument Structure Construction hypothesis, attempting to fill these gaps by looking at argument structure in a wider perspective.

Giving up the two hypotheses discussed above, the question remains how we can account for the variation in the dative’s function, or in other words, what guides the participant-role-interpretation of the polysemic dative. Note that the missing of both a form-function correlation, and a lexical semantic generalization moreover emphasizes the problem of the researcher in subjectively defining a participant role; considering the examples given above, we must conclude that such a decision shouldn’t be grounded on isolated parameters in a top-down manner, but rather on multiple sources of information, emerging from the data bottom-up.

The present paper follows recent work in cognitive semantics which emphasizes the probabilistic nature of polysemic lexical items, embedding such concepts as radial networks and prototype models in a quantitative analysis (e.g. Dattner 2015a; Divjak and Fieller 2014; Geeraerts 2010; Glynn 2010; Robinson 2014; Levshina, Geeraerts and Speelman 2013). Thus, I suggest that the the dative-marked participant role varies as a function of multiple parameters simultaneously, realized as Discourse Profile Constructions, in the service of a discursive-communicative need. These multiple parameters include simultaneous information coming from the lexicon, the morpho-syntax and the syntax, the semantics, and the pragmatic characteristics of the clause, encapsulated in the notion of transitivity (Hopper and Thompson 1980).

Transitivity, as a complex scale combined of multiple parameters, is highly relevant for understanding syntactic phenomena in a discursive perspective (Hopper and Thompson 1980; Næss 2007; Thompson and Hopper 2001). Regarding Hebrew, for example, Raz Zalzberg (2018) shows that the morpho-syntactic Hebrew verb paradigms, known as the binyan system, are used relative to a discourse-related transitivity construal, and that the discourse profiles of the various verbal paradigms (i.e. binyanim) are changing through later language development. The notion of scalar transitivity was proved relevant for the binyan system by Dattner (2015a) as well, showing that usage differences between two very similar transitive paradigms (piel and hifil; see Section 3.1 for details about the Hebrew binyan system) can be accounted for once discourse-related transitivity is taken into consideration. Specifically, regarding the Hebrew dative, Dattner (2008) argues for the existence of a dative lower transitivity construction, related to an array of low transitivity parameters. Thus, many of the parameters used in the present analysis are related to the scalar notion of transitivity. These parameters are articulated in the next section.

3 Data and method

3.1 Data

I account for simultaneous parameters in a quantitative, bottom-up fashion, revealing usage patterns in a corpus. Quantitatively searching for patterns in a multivariate data, we can achieve a description of the corpus that is less dependent on the researcher’s presuppositions regarding the research question. For example, the mere theoretical decision about the particular function of the dative in each sentence is a highly subjective one, as shown above, largely depending on the researcher’s theoretical stance (Rudzka-Ostyn 1996). Using quantitative bottom-up methods we can avoid the need for such decisions, and compare the patterns emerging in the data with the traditional, subjectively defined participant roles.

The corpus serving as a database for the present research is the Israeli Parliament Corpus (IPC, Dattner 2015b): an approximately 1,760,000 words corpus of spoken Hebrew, retrieved from the transcriptions of 198 meetings of committees of the Knesset, the Israeli parliament. The corpus is composed of multiple registers of language, both formal and colloquial. From this corpus, all occurrences of a dative (l-) marked pronoun were extracted, yielding 9,694 tokens of dative uses.[2]

Each token of dative use was coded for 15 variables. The choice of coding variables is based on the literature regarding dative constructions in Hebrew and in general. Thus, the coding includes the subject-predicate order, for example, as the predicate-first word order is said to be used with a particular dative function (Melnik 2006). As noted above, previous research found the notion of scalar, discourse-determined transitivity (Hopper and Thompson 1980) to play a crucial role in the use of dative constructions in Hebrew (Dattner 2008; Dattner 2015a). Transitivity, as defined by Hopper and Thompson (1980), is gradient, composed of a configuration of ten parameters. These configurations define different degrees of transitivity, such that an action is transferred from one participant to another with different degrees of effectiveness or intensity (Hopper and Thompson 1980): A high transitivity clause has two or more participants, and it conveys a telic, punctual action (rather than a state, or an atelic action) which is carried out by a volitional participant, high in Agency. If the patient (i.e. the endpoint of the action) is highly affected in the sense that it goes through a complete change of state, then the clause’s transitivity increases. A highly Individuated affected referent increases the transitivity of the clause even more: A human or an animate endpoint, who is concrete rather than abstract, singular, count, referential and definite, marked by a proper rather than a common noun, would render the clause higher in transitivity. The transitivity of a clause can be moreover increased if the clause if affirmative and contains a realis encoding of an event.

In Hebrew, as a semitic language, transitivity is also related to the verbal morphological paradigm (Berman 1987). The Hebrew verbal lexicon is morphologically organized in verb patterns, termed binyanim (lit. “buildings”). Seven such patterns exist, traditionally named kal, nifal, hifil, hufal, piel, pual, and hitpael. Each pattern is a paradigm related to a different degree of transitivity, and to a different type of argument structure (Berman 1993; Raz Zalzberg 2018): kal is underspecified for transitivity, piel and hifil are transitive, nifal and hitpael are traditionally analyzed as manifesting low transitivity, and pual and hufal are the passive patterns. Dealing with questions of transitivity and argument structure, the morpho-syntactic binyan system is highly relevant as a coding category for the present study (Ravid 2012).

Variables and values of the corpus data.

| Variable and Interpretation | Values |

|---|---|

| S/A.Agency.Individuation: Agency of Transitive Subject; Individuation of an Intransitive Subject | 4 values: high, low, mid, irr (irrelevant) |

| Verb.Binyan: Verbal paradigm of the main verb (the Hebrew Binyan system) | 8 values: kal, nifal, hifil, hufal, piel, pual, hitpael, irr (irrelevant; for non-verbal predicates) |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: Lexical category of the main predicate | 9 values: Adjective, Adverb, Complex.Verb, Discourse.Marker, Interrogative, Intransitive.Verb, Noun, Preposition, Transitive.Verb |

| Predicate.Type: Semantic type of the main predicate (following Dixon 2005) | 9 values: PA (Primary A), PB (Primary B), SA (Secondary A), SB (Secondary B), SC (Secondary C), SD (Secondary C), Property, Value, irr (irrelevant; details for each type are given in the relevant sections bellow) |

| No.Of.Arguments: Number of arguments in the clause | 3 values: one, two, three |

| Predicate.First: Order of Subject and predicate | 2 values: yes, no |

| Mode: Mode of the clause | 2 values: irrealis, realis |

| Polarity: Affirmative vs. negative clause | 2 values: affirmative, negative |

| Ellipsis: Elliptic clause | 2 values: no, yes |

| Verb.Passive.Middle: Voice of the main predicate | 2 values: active, passive/middle |

| No.Dative.Argument: Type of non-dative, non-subject argument | 6 values: Adjective, Clause, NP (Noun phrase), P (Preposition), V (Infinitival Clause), irr (irrelevant) |

| O.Argument.Individuation: Individuation of nominal Direct Object | 5 values: high, mid-high, mid-low, low, irr (irrelevant) |

| O.Argument.Definiteness: Definiteness of nominal Direct Object | 3 values: yes, no, irr (irrelevant) |

| Dative.Person: Person of the dative-marked participant | 3 values: first, second, third |

| Dative.Function: Dative function: participant role of the dative-marked participant | 9 values: Addressee, Affectee, Discourse.Marker, Ethical.dative, Evaluative.reference.point, Experiencer, Human.Endpoint,Possessive.Dative, Recipient |

| Total: 16 | 69 |

The coding variables in the current analysis thus consider the following criteria, summarized in Table 1: (i) Features of the Subject argument and the predicate: the agency and individuation of the Subject referent (S/A.Agency. Individuation), the verbal morphological paradigm (the Hebrew binyan: Verb.Binyan), the lexical category of the predicate (Predicate.Lxical.Category), the type of predicate (Predicate.Type), the number of arguments in the clause (No.Of.Arguments), Subject-Predicate order (Predicate.First), the mode of the clause (Mode), the polarity of the clause (Polarity), ellipsis (Ellipsis), and voice: whether the predicate is in the passive or middle voice (Verb.Passive.Middle). (ii) Features of the Direct-Object argument: the type of non-dative argument in the clause (No.Dative.Argument), the level of individuation of the Direct-Object referent (O.Argument.Individuation), and the definiteness of the Direct-Object argument (O.Argument.Definiteness). (iii) Features of the dative referent: the person of the dative referent (Dative.Person), and its participant role (Dative.Function).

Regarding the last parameter, it is important to note that the subjective coding of dative functions was done only to provide a reference point for the bottom-up clustering process, in order to consider the objectively defined clusters in the light of traditionally defined participant roles. Thus, the dative function for each token was coded by the researcher according to the traditional analyses of dative participant roles (e.g. Cuervo 2003; Halevy 2016; Van Belle and Langendonck 1996; Van Langendonck and Van Belle 1998). Importantly, the dimensions of the Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components reported bellow are constructed according to a set of active variables defined by the researcher. Only those variables that were hypothesized as candidates for explaining the distribution of dative interpretations are included as active variables. Therefore, the dative function parameter itself (Dative.Function), although coded in the corpus, was left out of the construction of the Multiple Correspondence Analysis map and the Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components.

3.2 Method

The usage-based approach to language, which I adopt as a theoretical framework, is embedded in Cognitive Linguistics, a model of language that emphasizes the role of method and data (Glynn and Fischer 2010). A usage-based model of language calls for an empirical, quantitative approach to linguistic research, and specifically to corpus linguistics. Quantitative methods in linguistics aid in describing, explaining, and predicting linguistic phenomena (Baayen 2008; Gries 2013). The analysis presented in this paper is based on multivariate exploratory statistics, and specifically on cluster analysis using Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (Husson, Lê and Pagès 2011; Husson, Josse, Le and Mazet 2013; R Core Team 2014).

Cluster analysis provides some objectivity in determining groups of similar tokens (Divjak and Fieller 2014). Cluster analysis (in different manifestations) is recently used in linguistics in various areas. For example, it has been used in sociolinguistics (e.g. Moisl and Jones 2005), comparing language varieties and dialects (e.g. Gries and Mukherjee 2010; Hyvönen, Leino and Salmenkivi 2007; Szmrecsanyi and Kortmann 2009), computational linguistics (e.g. Kovatchev, Salamó and Mart\’ı 2016), lexical processing (e.g. Baayen, Feldman and Schreuder 2006), Construction Grammar (e.g. Dattner 2015a; Gries and Stefanowitsch 2010, accounting for semantic classes and prototypical cases of constructions), or analyzing behavioral profiles (Divjak and Gries 2006; Snoek 2011, and see Moisl (2015) for a comprehensive survey of the use of cluster analysis in linguistics).

Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (henceforth, HCPC) is a special case of cluster analysis, done on the principal components of a Multiple Correspondence Analysis (Divjak and Fieller 2014; Husson, Josse & Pagès 2010; Husson, Lê and Pagès 2011). Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) is a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for categorical variables (Husson, Lê and Pagès 2011). Performing hierarchical clustering on the principal components of the MCA, the MCA can be viewed as a de-noising method. Without the noise in the data, the clustering analysis is done on the signal, rendering the analysis more stable. The resulted clusters of tokens can be described according to the variables in the data, or according to the individual tokens each cluster is composed of. For example, the categorical variable number of arguments in Table 1 has three categories: one, two, and three arguments in the clause. Hypothetically, using HCPC we might learn that the category three arguments is linked to cluster one, while the categories one argument and two arguments are linked to cluster two. This observation can teach us that tokens with a three-argument syntactic structure share more features within themselves than they share with one- and two-argument tokens. That is, we can conclude that (i) beyond the fact that they share a particular category, they are similar on other levels as well, and (ii), even if two tokens do not share a category, they may still belong to the same cluster (i.e. if they are similar enough) since they share other features. Using HCPC we can consider the most prototypical tokens in a cluster, such that they constitute the center of gravity: these are the tokens that are closest to the center of the cluster. All other tokens in the cluster are related to these tokens through a chain of family resemblances. Moreover, HCPC provides us with the objects that belong to a cluster and are placed the furthest from other clusters’ centers; these are the cluster’s unique tokens.

Choosing the number of clusters is critical in exploring data using clustering methods (Husson, Josse & Pagès 2010). That is, in the process of clustering the data, each token can be treated as a cluster on its own, and on a different level, all the individuals belong in a single cluster. The number of clusters is thus chosen according to growth of inertia. For example, consider a data that can be divided into three, four, or five clusters. Each division to a particular number of clusters explains a certain amount of the variation in the data, such that a division to five clusters explains the most, and a division to three clusters explains the least. The preferable number of clusters is a function of the growth of explained variation. That is, if the difference between dividing the data into three clusters versus four clusters is greater than the difference between dividing the data into four clusters versus five clusters, than one should choose to divide the data into four clusters. This is so since the further clustering would not result in a significantly better representation of the data, but would add noise to the representation. In other words, the further clustering costs too much. The results of the clustering analysis of the data introduced above are presented and discussed in the following section.

4 Clustering analysis results and discussion: Usage patterns as Discourse Profile Constructions

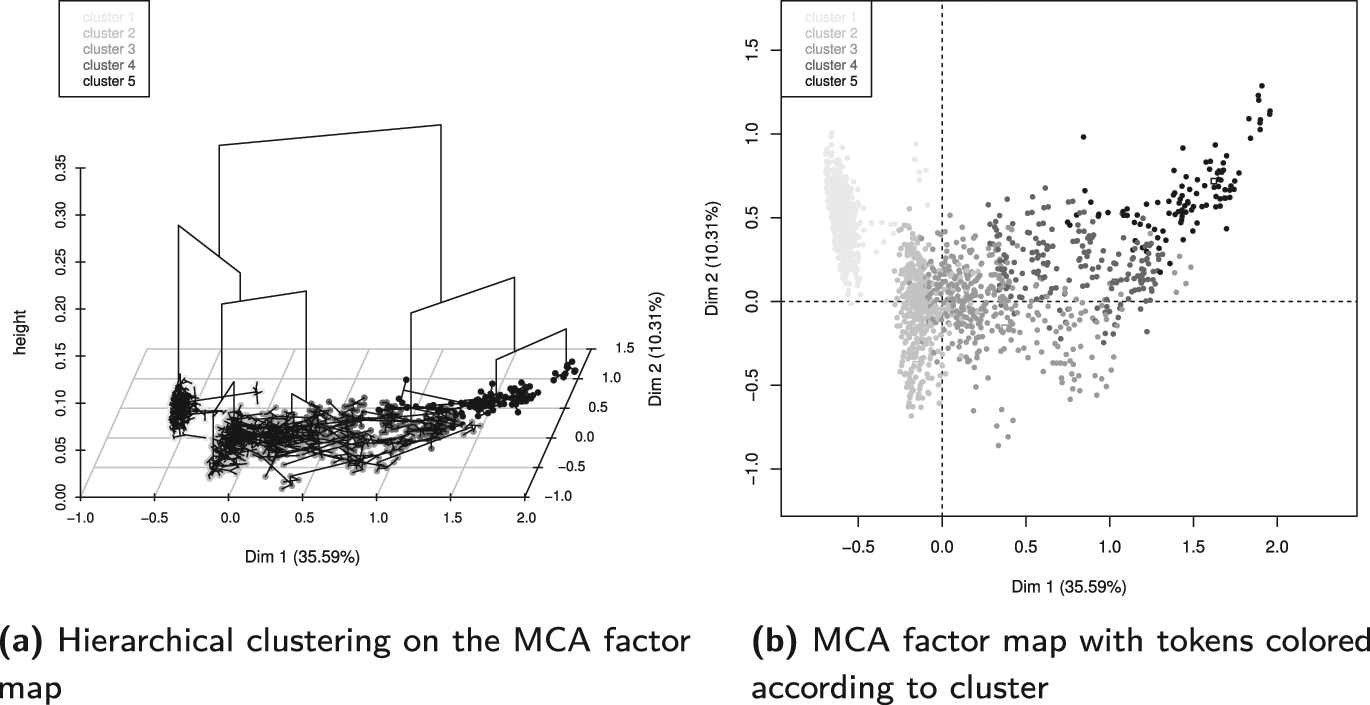

Figure 1 presents the results of the clustering analysis: Figure 1a portrays the clustering tree (a dendrogram); Figure 1b shows a Multiple Correspondence Analysis factor map, with tokens colored according to the cluster they belong to. The clustering process suggests that the data should be divided into five clusters.

Hierarchical clustering on principal components.

A cluster can be described, among other things, according to the categories it is linked to. In the present case, such a description reveals a particular usage pattern of dative clauses in Hebrew, which conventionally combines together linguistic and extra-linguistic features and has a constant function. In other words, the cluster is a Construction in the Construction Grammar sense: a conventional pairing of form and function. However, while constructions are usually defined based on morpho-syntactic or semantic-pragmatic parameters, the present account defines constructions on a wide, multifactorial basis. I therefore call this type of construction a Discourse Profile Construction. This concept is an extension of Argument Structure Constructions. Argument Structure Constructions constitute the syntactic-semantic basis for simple clauses and simple event structures in the language (Goldberg 1995). The Discourse Profile Construction, in this respect, extends the range of phenomena captured by the construction, and provides the basis for the usage conditions conventionally linked to such event structures. Thus, a particular event, or more specifically, a particular construal of a partial/mental effect in the case of the Hebrew dative, is conveyed through a specific usage pattern. The clusters identified in the corpus (presented in Figure 1) are analyzed as four Discourse Profile Constructions: Cluster One is the Extended Transitive Discourse Profile Construction (Section 4.1), Cluster Two is the Human Endpoint Discourse Profile Construction (Section 4.2), Cluster Three is the Extended Intransitive Discourse Profile Construction (Section 4.3), and Cluster Four is the Evaluative Reference Point Discourse Profile Construction (Section 4.4). Cluster Five is a small cluster that cannot receive a homogeneous treatment (Section 4.5).

4.1 Cluster one: Extended transitive discourse profile construction

The first cluster of tokens in the corpus gathers together 2,870 dative clauses that show a similar usage pattern, presented in Table 2.

Hierarchical clustering on principal components: Description of cluster one according to category.

| Category | Rel freq corpus | Rel freq cluster | Global | v.test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicate.Type: PA | 69.86 | 71.71 | 30.39 | Inf |

| P.Lexical.Category: Transitive.Verb | 41.00 | 99.13 | 71.58 | Inf |

| O.Argument.Individuation: mid-low | 99.72 | 63.00 | 18.70 | Inf |

| O.Argument.Individuation: mid-high | 100.00 | 28.54 | 8.45 | Inf |

| O.Argument.Definiteness: yes | 100.00 | 23.38 | 6.92 | Inf |

| O.Argument.Definiteness: no | 99.61 | 72.06 | 21.42 | Inf |

| No.Of.Arguments: three | 45.04 | 96.48 | 63.42 | Inf |

| No.Dative.Argument: NP | 59.34 | 98.82 | 49.30 | Inf |

| Dative.Function: Recipient | 89.10 | 50.98 | 16.94 | Inf |

| Predicate.First: no | 36.52 | 99.79 | 80.90 | 37.40 |

| Mode: realis | 52.94 | 47.11 | 26.35 | 29.28 |

| Verb.Binyan: kal | 43.50 | 63.31 | 43.09 | 26.06 |

| S/A.Agency.Individuation: mid | 71.36 | 20.31 | 8.43 | 25.86 |

| Dative.Person: third | 43.08 | 46.06 | 31.66 | 19.46 |

| S/A.Agency.Individuation: high | 46.40 | 34.39 | 21.94 | 18.68 |

| Dative.Function: Possessive.Dative | 81.70 | 6.38 | 2.31 | 16.34 |

| Dative.Function: Affectee | 85.53 | 4.74 | 1.64 | 14.78 |

| Verb.Passive.Middle: active | 30.40 | 100.00 | 97.40 | 13.20 |

| O.Argument.Individuation: high | 100.00 | 2.40 | 0.71 | 12.79 |

| O.Argument.Individuation: low | 93.48 | 1.50 | 0.47 | 9.11 |

| Ellipsis: no | 30.21 | 98.85 | 96.86 | 7.93 |

| Verb.Binyan: piel | 39.22 | 11.99 | 9.05 | 6.39 |

| Polarity: negative | 35.54 | 8.61 | 7.17 | 3.50 |

The first column in the table lists the categories of the variables in the corpus. The second column (Rel freq corpus) presents the relative frequency of tokens in the corpus manifesting each category which belong to the cluster. The third column (Rel freq cluster) indicates the relative frequency of the tokens in the cluster which possess each category. The fourth column (Global) lists the relative frequency of each category in the corpus, regardless of cluster. The last column (v.test) is related to the representation of the category in the cluster. If the v.test value is positive, the category is over-represented in the cluster; if it is negative, the category is under-represented (Husson, Lê and Pagès 2011). The present and the following tables display only those categories with a positive v.test value, as these are the categories that are linked to the cluster.

Analyzing Table 2 we can see that the first cluster of tokens is linked to transitive predicates with concrete participants (these are termed Primary A; the classification of predicates in the corpus followed the semantic approach to grammar advocated by Dixon (2005)). Most of the predicates belong to the kal verb paradigm (underspecified for transitivity), and some to the the transitive piel paradigm (see Table 1 for the list of coding categories). Syntactically, Cluster One is linked to a three-argument structure with a nominal A, a nominal O, and a dative-marked participant in the second person, functioning as what a traditional participant role analysis would define as a Recipient, an Affectee, or a Possessive Dative. Cluster One is also linked to a realis mode of clauses, with an intermediate-high degree of Agency of the A referent, and an individuated O participant. These characteristics of Cluster One correspond to high transitivity, and a high degree of affectedness of the dative-marked participant (Dattner 2008; Hopper and Thompson 1980; Næss 2007; Rozas 2007; Thompson and Hopper 2001).

Besides its categorical variables, each cluster has a limited number of central and unique exemplars according to which it can be described. A central exemplar is the token closest to the center of cluster, in the sense that it shares more formal categories with other tokens in the cluster than with tokens in other clusters. A unique exemplar, on the other hand, is the token furthest from the centers of other clusters, in the sense that it shares few, if any, categories with the central tokens of the other clusters. The following are Cluster One’s central exemplars:

| xiyavti | et | ha-sar | […] | lehacig | lanu | ma | ha-misrad | asa. |

| I.forced | acc | the-minister | […] | to.present | to.us | what | the-office | did. |

‘I forced the minister to show us what his office was doing.’

| ani | mevakeshet | mi-necigey | […] | lehavi | lanu | netunim | yoter | meduyakim. |

| I | ask | from-the.representatives.of | […] | to.bring | to.us | data | more | accurate. |

‘I’m asking the representatives of […] to give us more accurate data.’

| hem | ya’aviru | lanu | takanot | ad | ha-rishon | be-november. |

| they | will.pass | to.us | regulations | until | the-first | in-November. |

‘They will get some regulations through for us by November first.’

Looking at the three sentences in (8), we can observe a realization of the usage pattern presented in Table 2 as strongly linked to Cluster One: Verbs with concrete participants as their semantic roles, embedded in a three-argument structure with a highly agentive A participant (e.g. the minister or the representatives), and a nominal O participant. Cluster One’s unique exemplar, the token furthest from the centers of other clusters in the data, is the following:

| atem | lo | notnim | lo | et | ha-kelim | le-hitmodedut | im | ha-beaya | ha-zot. |

| you | not | give | to.him | acc | the-tools | to-cope | with | the-problem | the-this. |

‘You don’t give him the right tools for coping with this problem.’

(9) presents an accusative marked, relatively individuated O participant, a transitive, Primary A predicate in the kal paradigm (natan ‘give’), and an A participant with an intermediate-high degree of agentivity. These features, as we have seen above, mostly characterize tokens from Cluster One, and thus are unique to this particular cluster. Accordingly, the dative-marked participant in (9) can be termed a Recipient: The dative-marked participant is affected by a transitive motion event in which an Agent (metaphorically) moves a Theme from one point to another. However, it involves partial affectedness and indirect relations: the Recipient does not go through a complete change of state. The only entity that is construed as going through a change of state is the transferred Theme. The Recipient is affected only as a result of the Agent’s action on a different object, to the extent that he becomes a possessor of the transferred Theme. This type of three argument relation is elementary, and thus is lexically encoded by transfer verbs (Francez 2006; Haspelmath 2011; Malchukov, Haspelmath and Comrie 2010).

The first Discourse Profile Construction is thus related to high transitivity values, and is defined as the Extended Transitive Discourse Profile Construction: a usage pattern used to construe a relation between two participants (i.e. a transitive event) that produces a high degree of effect on a third entity (an extension to core, see Dixon (2005)). The third entity in the current case can be analyzed as a Recipient, an Affectee, or a Possessive Dative. This dative can be lexically governed by the predicate (as in (9) for example), or it can be a non-lexical dative, as in (10) bellow. It is a cover function unifying all extensions of an affective situation, in which the core event can be construed as complete without any reference to a third participant. It is in the Extended Transitive Discourse Profile Construction that a two-place event gains a relative, dependent status, anchored to a third, dative-marked participant. For example, it is only in the current Discourse Profile Construction (i.e. usage pattern) that the two-participant event of ‘drinking water’ is construed as related to a third entity, consequently affecting it:

| holxim | lishtot | li | et | ha-maym | me-ha-shorashim | shel | ha-cmaxim. |

| walk | to.drink | to.me | acc | the-water | from-the-roots | of | the-plants. |

‘They’re gonna drink my plants’ water (= they are going to draw water from a nearby underground location, whereby my plants will loose their water supply).’

This description of Cluster One is in line with Boneh and Bar-Asher Siegal’s (2014) account of non-lexical datives in Hebrew. Boneh and Bar-Asher Siegal (2014) suggest that the affected dative is a cover function, comprising the Possessor, the Benefactor, and the Malefactor. The common feature shared by these roles, according to Boneh and Bar-Asher Siegal (2014), is the marking of a participant who is affected by an event of which he is not a part of.

The following sentence contains such a non-lexical dative, which might pose a problem for interpretation. The solution proposed by the present Discourse Profile Constructions approach assumes that this sentence belongs to the Extended Transitive Discourse Profile Construction which guides the non-lexical dative’s interpretation:

| merkaz | ha-mexkar | hexin | lanu | niyar | emda |

| center | the-research | prepared | for.us | paper | position |

‘The research center prepared us a position paper.’

(11) belongs to a usage pattern which emerges out of a set of utterances characterized as having a transitive predicate that belongs to a specific class of verbs, a realis mode, and a three participant event in which the affected participant is highly affected and the affecting participant has high agentivity and volition. That is, it is a clause with high transitivity, that construes a relation between a two participant event and a third participant. These (and some other) characteristics constitute a usage pattern, linked to a single conceptualization of the world. This link guides the interpretation of the dative-marked participant, be it lexically governed or not: In the prototypical case of the Extended Transitive Discourse Profile Construction, it construes a transfer relation. In the less prototypical cases, it can be any high transitivity event that can be construed as affecting a third participant.

4.2 Cluster two: Human endpoint discourse profile construction

The second cluster is presented in Table 3. It is the largest cluster in the data, grouping together 4,127 tokens of dative clauses (42.5% of the corpus).

HCPC: Description of cluster two according to category.

| Category | Rel freq corpus | Rel freq cluster | Global | v.test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicate.First: no | 52.08 | 98.96 | 80.90 | Inf |

| Predicate.Type: PB | 78.57 | 70.08 | 37.97 | Inf |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: | ||||

| Transitive.Verb | 58.74 | 98.76 | 71.58 | Inf |

| O.Argument.Individuation: irr | 59.31 | 99.83 | 71.66 | Inf |

| O.Argument.Definiteness: irr | 59.31 | 99.83 | 71.66 | Inf |

| No.Dative.Argument: Clause | 80.16 | 56.70 | 30.11 | Inf |

| Dative.Function: Addressee | 80.93 | 64.28 | 33.81 | Inf |

| S/A.Agency.Individuation: low | 57.36 | 72.47 | 53.79 | 32.18 |

| Mode: irrealis | 51.51 | 89.12 | 73.65 | 30.93 |

| No.Of.Arguments: three | 52.78 | 78.63 | 63.42 | 27.23 |

| Dative.Person: second | 62.91 | 38.09 | 25.78 | 23.80 |

| Verb.Binyan: hifil | 63.26 | 36.64 | 24.65 | 23.50 |

| Dative.Function: | ||||

| Human.Endpoint | 61.59 | 26.92 | 18.61 | 18.01 |

| Verb.Passive.Middle: active | 43.71 | 100.00 | 97.40 | 16.69 |

| Predicate.Type: SC | 64.61 | 15.70 | 10.35 | 14.83 |

| Verb.Binyan: kal | 50.71 | 51.32 | 43.09 | 14.09 |

| Polarity: affirmative | 44.34 | 96.68 | 92.83 | 13.19 |

| No.Dative.Argument: V | 59.64 | 16.11 | 11.50 | 12.17 |

| No.Dative.Argument: P | 74.83 | 5.48 | 3.12 | 11.54 |

| Ellipsis: yes | 73.36 | 5.40 | 3.14 | 11.03 |

| S/A.Agency.Individuation: high | 50.82 | 26.19 | 21.94 | 8.67 |

| Verb.Binyan: piel | 55.99 | 11.90 | 9.05 | 8.36 |

Cluster Two is a coherent and homogeneous cluster, linked with transitive predicates from the types Primary B and Secondary C. Primary B verbs have concrete participants, but they can also be complemented by a clause (either instead of or in addition to the nominal complement), while Secondary C verbs introduce a subject that actually plays a role in bringing about the event or state referred to in the complement clause’s verb (Dixon 2005). These predicates are situated in a three-argument structure, but unlike Cluster One, the Direct Object slot is occupied by a clause or a Preposition Phrase rather than a Noun Phrase. That is, two arguments are referential, while the third is a clausal complement of the predicate conveying the content in a telling or showing event (Primary B verbs), or a Prepositional complement of the predicate (Secondary C verbs). The verb paradigms (binyan) linked with Cluster Two are the transitive hifil, which was not related to Cluster One, the underspecified kal, with the transitive piel showing a weaker link. Cluster Two is linked to the irrealis mode, and to a dative referent in the third person, which in participant role terms would be analyzed as one of the following: (i) an Addressee, the human endpoint of a message delivering action, its audience, or (ii), a Human Endpoint, which is the only (partially/mentally) affected endpoint of a two-participant event, marked as human. These characteristics can be detected in the following central exemplar:

| yesh | xavery | kneset | she-azru | lanu | b-a-inyan | ha-ze. |

| there.are | parliament | members | that-helped | to.us | in-the-issue | the-this. |

‘Some parliament members helped us with that.’

Syntactically, the third argument in (12) is a Prepositional complement of the main predicate, usually indicating a secondary event the initiator of which is the dative-marked participant.

The unique exemplar of Cluster Two construes a telling event in which the dative-marked participant is mentally affected:

| ani | macia | lexa | ke-ohed | she-tisgor | oto | le-reva | shaa. |

| I | suggest | to.you | as-fan | that-you.will.close | it | for-quarter | hour. |

‘As a fan, I suggest that you close it for fifteen minutes’.

Note that the third argument in (13) is a finite clause indicating the content of a message delivered by the A referent to the dative-marked participant. That is, the dative-marked participant in both (12) and (13) is the only real affected-endpoint of the event, the clausal/Prepositional complement being non-referential (Thompson and Hopper 2001). The construal of the telling event conveyed in (13) profiles the audience of the telling action (the dative-marked participant) as the single endpoint of the action. This is in contrast with telling construals that belong to Cluster One, where the type of message is profiled and occupies a full nominal argument position, the O argument:

| anaxnu | poxadim | lehacia | lahem | hacaot. |

| we | afraid | to suggest | to.them | suggestions. |

‘We’re afraid of giving them any suggestions.’

The dative-marked participant in the ‘type of message’ case (the audience in (14)) is not construed as the only affected entity in the event, but rather as indirectly affected by the metaphorical creation of a message. Thus, a telling act is construed differently when used within the usage patterns of Cluster One and Cluster Two: in the Discourse Profile Construction that emerges from the tokens of Cluster One a telling/showing event is construed as a creation of an abstract entity. This creation is done relative to another entity (the dative-marked participant), thus affecting it. In the Discourse Profile Construction emerging from the tokens of Cluster Two, however, a telling/showing event is construed as a two-pole action, with a teller/shower and an audience/perceiver, emphasizing not the creation of the message, but its content.

This is, then, the Discourse Profile Construction emerging from usage pattern uncovered as Cluster Two: a set of lexical, morpho-syntactic, semantic and pragmatic features that can be summarized as related to an intermediate level of transitivity, conventionally paired with an interpretation of the dative-marked participant as mildly/mentally affected by an action initiated by the A referent. This type of action is usually realized through either a telling/showing or helping/causing events as shown above, but not always, as can be seen in the following Cluster Two examples:

| eyze | metayel | yirce | lehagia | le-shetax | tiyuley | ofnaym | kshe-kodxim | lo, | hu | xoshesh | mi-zihum | svivati. |

| what | traveller | will want | to arrive | to-field | trips.of | bicycle | when-drill | to.him, | he | afraid | of-pollution | environmental. |

‘What traveller would like to have a bicycle trip in a drilling area? He’s afraid it would be polluted.’

| ke-xol | she-ze | simeax | oti, | ze | gam | hixiv | li. |

| as-all | that-it | made happy | acc.me, | it | also | hurt | to.me. |

‘As much as it made me happy, it hurt me too.’

| im | misheu | xayav | kesef | […] | ve-hu | lo | yaxol | leshalem, | mevatrim | lo | al | ze. |

| if | someone | owes | money | […] | and-he | not | can | to pay, | relinquish.pl | to.him | about | it. |

‘If one owes money and they can’t pay, their debt will be forgotten.’

HCPC: Description of cluster three according to category.

| Category | Rel freq corpus | Rel freq cluster | Global | v.test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verb.Binyan: nifal | 98.15 | 48.18 | 5.57 | Inf |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: | ||||

| Intransitive.Verb | 88.16 | 99.55 | 12.81 | Inf |

| No.Of.Arguments: two | 30.14 | 84.73 | 31.90 | Inf |

| Dative.Function: Experiencer | 39.01 | 64.73 | 18.83 | 36.38 |

| Verb.Passive.Middle: passive/middle | 100.00 | 22.91 | 2.60 | 33.84 |

| O.Argument.Individuation: irr | 15.82 | 99.91 | 71.66 | 27.71 |

| O.Argument.Definiteness: irr | 15.82 | 99.91 | 71.66 | 27.71 |

| Predicate.Type: SD | 56.40 | 27.64 | 5.56 | 26.64 |

| No.Dative.Argument: Adj | 100.00 | 11.82 | 1.34 | 23.94 |

| Verb.Binyan: hufal | 100.00 | 7.09 | 0.80 | 18.39 |

| Predicate.First: yes | 24.30 | 40.91 | 19.10 | 17.94 |

| Verb.Binyan: hitpael | 86.02 | 7.27 | 0.96 | 16.71 |

| Predicate.Type: SB | 44.48 | 13.55 | 3.46 | 15.69 |

| No.Dative.Argument: NP | 14.81 | 64.36 | 49.30 | 10.67 |

| Verb.Binyan: pual | 100.00 | 2.27 | 0.26 | 10.21 |

| Dative.Person: first | 14.98 | 56.18 | 42.56 | 9.64 |

| Mode: realis | 16.13 | 37.45 | 26.35 | 8.60 |

| Ellipsis: no | 11.71 | 100.00 | 96.86 | 8.35 |

| Dative.Function: Ethical.Dative | 59.18 | 2.64 | 0.51 | 8.04 |

| Polarity: negative | 21.30 | 13.45 | 7.17 | 7.84 |

| Predicate.Type: SA | 71.43 | 1.82 | 0.29 | 7.39 |

| S/A.Agency.Individuation: irr | 17.06 | 23.82 | 15.84 | 7.32 |

| S/A.Agency.Individuation: low | 13.27 | 62.91 | 53.79 | 6.48 |

| Predicate.Type: PA | 13.82 | 37.00 | 30.39 | 4.98 |

| Dative.Person: third | 12.51 | 34.91 | 31.66 | 2.44 |

What groups these exemplars together with the central and unique exemplars presented above is the usage-pattern-based Discourse Profile Construction. That is, it is not a case of metaphorical extension from help to relinquish, or to drill. Rather, these cases construe an event with an intermediate degree of transitivity in which the dative-marked participant is the only endpoint, partially or mentally affected. These exemplars share more formal similarities with other exemplars belonging to Cluster Two than with exemplars from other clusters in the corpus: it is a combination of a transitive verb with a two-argument, Subject-first structure in an irrealis clause, or a three-argument structure with a non-nominal occupying the third argument position (i.e. no individuated O), and an intransitive verb in the active voice. This is the Human Endpoint Discourse Profile Construction.

4.3 Cluster three: Extended intransitive discourse profile construction

The third cluster in the corpus is composed of 1,110 tokens of dative clauses, and is summarized in Table 4. The tokens of Cluster Three are linked to the Secondary D, B, and A types of predicates (ordered according to strength of link), mostly in the nifal verb paradigm, and to the Primary A type in a weaker link. Secondary D verbs are intransitive verbs that take a complement clause in subject slot and another role (a stance taker), marked by the dative. Secondary B verbs have one independent role (the subject) in addition to the roles of the verb in the complement clause, describing the subject’s attitude towards some event or state. Secondary A verbs have no independent semantic roles and modify the meaning of another verb (the main verb of a complement clause), sharing its roles and syntactic relations. Primary A verbs have only concrete participants as their semantic roles. Cluster Three is linked to a two-argument, predicate-first structure, with the predicate either in the nifal paradigm, as mentioned above, or in the passive voice, thus appearing in the hufal and pual verb paradigms. The non-dative argument most strongly linked to Cluster Three is of an Adjectival nature, as in:

| ze | nire | li | naxon. |

| it | seems | to.me | right. |

‘It seems right to me.’

It can, however, be a clause or a nominal as well. In nominal cases, it is low in Agentivity. The dative referent linked to Cluster Three is in the first person, and it corresponds with the Experiencer or the Ethical Dative in traditional terms, as in the following central exemplar of Cluster Three:

| me-olam | lo | yadati | she-ani | yaxol | lemale | et | ze | b-a-internet | ad | she-ze | noda | li. |

| never | not | I.knew | that-I | can | fill | acc | this | in-the-web | until | that-it | was.known | to.me. |

‘I didn’t know I can go on-line and fill these forms until it became known to me.’

While the Experiencer (17) is the participant role most strongly linked with Cluster Three, other types of participant roles can be found in the tokens close to the cluster’s center as well. For instance, the dative-marked participant in (18) can be analyzed as a Recipient or a Possessive Dative:

| hu | yirce | leharviax | kesef, | hu | yirce | sh-yishaer | lo | mashu | b-a-yad. |

| he | will.want | to earn | money, | he | will.want | that-will.stay | to.him | something | in-the-hand. |

‘He’ll want to get something out of it, to earn some money, to have something in his hand.’

Nevertheless, the dative-marked participant in (18) is profiled as wishing to be in a state in which he has some money, therefore it is more of an Experiencer than a Possessor.

The unique token of the cluster, on the other hand, may be analyzed as consisting of an Addressee dative-marked participant, which is the human endpoint of a message delivering action. In Cluster Three, however, such an Addressee, a Recipient or a Possessive Dative are related either to intransitive predicates (18), or to the passive voice, as in:

| hu | kibel | et | ha-haca’a | she-huc’a | lo. |

| he | accepted | acc | the-offer.3.FM | that-was.suggested.3.FM | to.him. |

‘He accepted the offer that was made to him.’

Considering this variety of examples, trying to characterize the tokens in Cluster Three as related to a single participant role is an impractical task. The question thus remains what brings these (and other) tokens together; i.e. what are the important similarities they feature, such that they share a usage pattern, thus belonging to the same cluster. The tokens in Cluster Three are counted as similar not on the basis of a common participant role marked by the dative, but rather on the basis of the construal conveyed by the speaker, realized as a shared usage pattern. The following sentences belong to Cluster Three as well, and include an intransitive verb, a predicate-first structure, and other low transitivity features.

| ani | agid | laxem | ma | kara | li | ha-boker. |

| I | will.tell | to.you | what | happened | to.me | this-morning. |

‘Let me tell you what happened to me this morning.’

| ze | nire | li | kriti. |

| it | seems | to.me | critical. |

‘It seems critical to me.’

| mamash | lo | ba | li | she-hu | yavo | im | ha-emda | ha-kodemet. |

| really | not | come | to.me | that-he | will.come | with | the-viewpoint | the-former. |

‘I would really hate it if he’d come here with his old viewpoint.’

HCPC: Description of cluster four according to category.

| Category | Rel freq corpus | Rel freq cluster | Global | v.test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verb.Binyan: irr | 72.52 | 96.23 | 15.62 | Inf |

| S/A.Agency.Individuation: irr | 53.52 | 72.04 | 15.84 | Inf |

| Predicate.First: yes | 48.76 | 79.14 | 19.10 | Inf |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: Adj | 81.67 | 92.55 | 13.34 | Inf |

| No.Of.Arguments: two | 36.90 | 100.00 | 31.90 | Inf |

| Dative.Function: Experiencer | 41.32 | 66.08 | 18.83 | 38.25 |

| Dative.Function: | ||||

| Evaluative.Reference.Point | 86.83 | 31.20 | 4.23 | 36.37 |

| Predicate.Type: Property | 72.74 | 35.32 | 5.71 | 35.28 |

| Predicate.Type: Value | 76.38 | 30.32 | 4.67 | 33.28 |

| O.Argument.Individuation: irr | 16.42 | 100.00 | 71.66 | 28.49 |

| O.Argument.Definiteness: irr | 16.42 | 100.00 | 71.66 | 28.49 |

| Dative.Person: first | 20.77 | 75.11 | 42.56 | 23.76 |

| No.Dative.Argument: V | 33.63 | 32.87 | 11.50 | 20.92 |

| Predicate.Type: SD | 33.95 | 16.04 | 5.56 | 14.03 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Type: Adv | 54.05 | 3.51 | 0.76 | 8.83 |

| Verb.Passive.Middle: active | 12.08 | 100.00 | 97.40 | 7.71 |

| Ellipsis: no | 12.13 | 99.82 | 96.86 | 7.69 |

| No.Dative.Argument: Clause | 13.39 | 34.27 | 30.11 | 3.23 |

| Polarity: negative | 15.40 | 9.38 | 7.17 | 2.97 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: | ||||

| Complex.Verb | 100.00 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 2.46 |

| Mode: irrealis | 12.16 | 76.07 | 73.65 | 1.99 |

This usage pattern is related to a construal that anchors a situation to a human referent, the dative-marked participant. This is the Extended Intransitive Discourse Profile Construction. That is, while a stative construal consists of an S argument and a predicate, the Extended Intransitive construal is composed of an S argument, a predicate, and an extra participant marked by the dative (E, or extension to core, see Dixon (2005)), to which the relation between the S and the V are construed as relevant, much like the Extended Transitive Discourse Profile Construction emerging from Cluster One.

4.4 Cluster four: Evaluative reference point discourse profile construction

Cluster Four is presented in Table 5. It consists of 1,141 tokens, strongly linked to a two-argument syntactic structure with Adjectival predicates from the types Property and Value (Dixon 2005). The Property type includes adjectives such as barur, ‘clear,’ kashe, ‘hard,’ and nagish, ‘accessible.’ The Value type includes adjectives such as xashuv, ‘important,’ tov, ‘good,’ and nifla, ‘wonderful.’ Another distinctive feature of Cluster Four’s tokens is a predicate-first word order, with the non-dative argument realized as a non-finite clause. Cluster Four is linked to dative referents in the first person, traditionally analyzed as Experiencers, Judicantis, or Evaluative Reference Points in participant role terms. (21a)–(21b) are the closest exemplars to Cluster Four’s center of gravity, sharing the highest number of features with other exemplars in the cluster. (22a)–(22b) are Cluster Four’s unique exemplars, sharing the smallest number of features with tokens from other clusters.

| ma | laxuc | lanu | laasot | et | ze | axshav? |

| what | pressed | to.us | to do | acc | it | now? |

‘What’s the rush to do it right now?’

| barur | li | laxalutin | ha-racon | legaven | b-a-ir | ha-zot. |

| clear | to.me | totally | the-desire | to vary | in-the-city | the-this. |

‘I totally understand the desire to achieve a variation in this city.’

| im | mankal | […] | savur | she-lo | rauy | lo | lehagia | l-a-diyun | shel | ha-kneset, | ha-kneset | af | paam | lo | neelevet. |

| if | C.E.O | [of…] | thinks | that-not | appropriate | to.him | to arrive | to-the-discussion | of | the-Knesset, | the-Knesset | never | not | gets | insulted. |

‘If the C.E.O of … thinks the discussion is not important enough for him to be here, the Knesset never gets insulted.’

| lo | naxon | lanu | leharim | et | ha-kfafa. |

| not | right | to.us | to raise | acc | the-glove. |

‘We should not ‘take up the glove’.’

Looking at Table 5 and considering (21)–(22), we can characterize Cluster Four as an Adjectival/Adverbial cluster. Its tokens construe an evaluation of a state of affairs relative to, or from the point of view of, the dative-marked participant. For example, the speaker in (22a) is not evaluating the arriving of the CEO as inappropriate; rather, this evaluation is anchored to a reference point – the dative-marked participant. And in (22b) there is a subjective reference to the situation, anchoring the evaluation to a reference point profiled by the dative-marked participant. That is, in (22b) the conveyed meaning can be broken into two parts, much like the type of construal we have seen in the case of the extended constructions emerging from Cluster One and Cluster Three: an evaluation, and its anchoring to a reference point.

In summary, the usage pattern of Cluster Four revolves around low affectedness of the dative-marked participant, and adjectival clause with low transitivity and predicate-first word order. This usage pattern is conventionally paired with a construal of an evaluation of a state of affairs, anchored to the dative-marked participant. This convention is the Evaluative Reference Point Discourse Profile Construction.

4.5 Cluster five

The fifth cluster is outlined in Table 6. It is the smallest cluster in the data, consisting of only 456 tokens. Clusters with a small number of tokens tend to be rather heterogeneous, and are less easily characterizable compared with other clusters presenting a uniform behavior.

HCPC: Description of cluster five according to category.

| Category | Rel freq corpus | Rel freq cluster | Global | v.test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/A.Agency.Individuation: irr | 28.84 | 97.15 | 15.84 | Inf |

| Predicate.First: yes | 24.30 | 98.68 | 19.10 | Inf |

| No.Of.Arguments: one | 92.51 | 92.11 | 4.68 | Inf |

| No.Dative.Argument: irr | 93.54 | 92.11 | 4.63 | Inf |

| Verb.Binyan: irr | 26.75 | 88.82 | 15.62 | 36.02 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Type: irr | 99.35 | 33.77 | 1.60 | 31.31 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: N | 100.00 | 25.66 | 1.21 | 27.19 |

| Dative.Function: Discourse.Marker | 50.83 | 33.77 | 3.13 | 24.22 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: Adj | 17.56 | 49.78 | 13.34 | 19.35 |

| O.Argument.Individuation: irr | 6.56 | 100.00 | 71.66 | 17.51 |

| O.Argument.Definiteness: irr | 6.56 | 100.00 | 71.66 | 17.51 |

| Dative.Function: Experiencer | 11.34 | 45.39 | 18.83 | 13.32 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Type: Property | 16.61 | 20.18 | 5.71 | 10.95 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: Adv | 45.95 | 7.46 | 0.76 | 10.54 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: | ||||

| Interrogative | 100.00 | 2.85 | 0.13 | 8.66 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: | ||||

| Discourse.Marker | 100.00 | 1.97 | 0.09 | 7.12 |

| Ellipsis: yes | 15.13 | 10.09 | 3.14 | 7.08 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Type: SB | 14.33 | 10.53 | 3.46 | 6.95 |

| Dative.Function: | ||||

| Evaluative.Reference.Point | 12.93 | 11.62 | 4.23 | 6.75 |

| Mode: irrealis | 5.43 | 85.09 | 73.65 | 5.99 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Category: P | 100.00 | 1.10 | 0.05 | 5.18 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Type: SD | 9.65 | 11.40 | 5.56 | 4.96 |

| Verb.Passive.Middle: active | 4.83 | 100.00 | 97.40 | 4.59 |

| Polarity: negative | 8.06 | 12.28 | 7.17 | 3.99 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Type: Value | 8.61 | 8.55 | 4.67 | 3.65 |

| Dative.Person: second | 5.56 | 30.48 | 25.78 | 2.32 |

| Predicate.Lexical.Type: SA | 14.29 | 0.88 | 0.29 | 1.96 |

The tokens of Cluster Five have a predicate-first syntactic structure, with non-verbal predicates, and an irrealis clause. They are mostly one-argument clauses, with the single argument being the dative-marked participant as in the following central (23a) and unique (23b) exemplars:

| ani, | be-nigud | lexa, | lo | mitlahevet | me-ha-nose. |

| I, | in-contrast | to.you, | not | excited | from-the-issue. |

‘Unlike you, I’m not so thrilled about this subject.’

| toda | raba | lexa, | adoni | ha-yoshev | rosh. |

| thank | very | much | to.you, | Mr. | chairman. |

‘Thank you very much, Mr. chairman.’

The dative construction in (23a) is a parenthetical comment concerning the speech act and its interlocutors in this case. The dative construction’s function in this type of parenthetical comments is to put the utterance in a relative, dependent state, anchoring it to an external entity (be it of the interlocutors, or another relevant referent).

The unique exemplar of Cluster Five (23b) is a gratitude utterance, aimed towards the dative-marked participant. It resembles dative clauses with other nominal predicates concerning manner and greetings (also belonging to Cluster Five) such as:

| kol | ha-kavod | laxem. |

| all | the-respect | to.you. |

‘Way to go!’

| shalom | laxem. |

| hello | to.you. |

‘Hello!’

In some respects, these examples are not different from the Addressee participant role, or the Recipient. While in the Recipient cases it is a transfer event construal in which a transitive motion event is directed at the dative-marked participant, and in the Addressee cases it is a telling/showing event, here it is a greeting action, lexicalized in a nominal rather than a verbal construction. Thus, there is no substantial difference between the nominal dative clause in (23b) and its verb-headed equivalent in (25) that belongs to Cluster Two:

| ani | meod | mode | lexa. |

| I | very | thank | to.you. |

‘Thank you very much.’

The only difference is in the construal of the state of affairs. While in (25) the greeting action is construed as a transitive event consisting of an Initiator and an Endpoint, the same action is construed in (23b) as a stative situation with no explicit reference to the Initiator of the action, profiling its Endpoint as the only relevant human entity.

We can see, then, that there is no general Discourse Profile Construction that emerges from the tokens of Cluster Five, due to the cluster’s heterogeneous nature. However, we can still detect a recurrent pattern agreeing with the types of construals we have seen so far as related to dative constructions.

4.6 Clustering analysis: Summary of the results

Summing up the results of the cluster analysis, we have shown that a corpus of Hebrew dative clauses can be categorized into clusters in a bottom-up manner to reveal hidden usage patterns. The clustering process yielded five clusters of tokens sharing usage patterns. Each of the five clusters in the data was shown to be both a cluster of tokens, and a cluster of lexical, morpho-syntactic, semantic, and discursive features. Four clusters were shown to be paired with unique conceptualizations. These correspondences between usage patterns and conceptualizations of the world have been defined as Discourse Profile Constructions. The first two clusters are transitive: The first cluster is a high transitivity pattern, defined as the Extended Transitive Discourse Profile Construction. The second cluster is an intermediate transitivity pattern, defined as the Human Endpoint Discourse Profile Construction. The third and fourth clusters are subdivisions of an intransitive pattern: The Extended Intransitive Discourse Profile Construction, and the Evaluative Reference point Discourse Profile Construction. Cluster five was shown to be incoherent due to its low frequency.

5 Conclusions

Usage-Based approaches to language (e.g. Kemmer and Barlow 2000; Tomasello 2003) follow Wittgenstein’s (1953) conceptualization of meaning in which the meaning of a word is its use in language (Tomasello 2009; Bybee 2010). Language is conceptualized as a Complex Adaptive System (Beckner, Blythe, Bybee, Christiansen, Croft, Ellis, Holland, Ke, Larsen-Freeman and Schoenemann 2009), grammar is viewed as the cognitive organization of one’s experience with language (Bybee 2006), and usage is taken to affect grammar. Construction Grammar theories adopt the usage-based approach to meaning, expanding its scope to include schematic syntactic structures. Abandoning the syntax-lexicon dichotomy (Croft 2001; Goldberg 2006; Perek 2015), Construction Grammar theories describe both lexical items and grammatical constructs using the same theoretical tools. Nevertheless, while it is agreed that “[t]o understand grammar, find out how it is used” (Du Bois, Kumpf and Ashby 2003), the notion of usage has not been adequately defined yet. The present paper suggests an innovative approach for defining the usage from which grammatical meaning emerges. Specifically, the paper focuses on a set of Hebrew dative constructions in order to exemplify the manifestation of a usage-based meaning. Utilizing a multivariate exploratory statistical technique to reveal usage patterns in corpus data, I introduced the Discourse Profile Construction: a conventional correspondence between a multifactorial usage pattern and a unified conceptualization of a state of affairs.

5.1 Discourse profile constructions: Implications for a usage-based grammar

In a seminal work, Goldberg (1995) shows that Argument Structure Constructions are the language’s basic clausal form-meaning pairings. These concern schematic clausal expressions and idealized event schemes. Goldberg points out that only such idealized events can lie at the bottom of basic clausal expressions; since specific events do not frequently recur, they are not incorporated into the grammar (Goldberg 1998; Kemmerer 2006). Thus, in any language we should be able to find a correspondence between basic clausal expressions and idealized event schemes with constant participant roles. However, regarding Hebrew dative constructions, the present paper argues that we cannot assign a single functional interpretation to correspond with a single Argument Structure, nor can we say for every Argument Structure that it construes a single idealized event with constant participant roles. Conducting a corpus research and using multivariate exploratory statistics, the present paper shows that from a usage point of view we should take into account multiple parameters that govern the interpretation of a clause.