Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the services and facilities provided by rural public libraries in West Bengal, India. In addition, the study aims to evaluate the perceptions of librarians regarding the implementation of Information Communication Technology (ICT) applications in these libraries. The study employed a mixed-methods approach, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative methods to gather data. The primary method of data collection was a survey using a structured questionnaire, which was administered to a total of 102 rural libraries. Furthermore, interviews were conducted with the respective librarians to bring more objectivity to the results. The findings revealed that rural libraries possess a moderate collection of printed books, newspapers, and magazines. The results indicate that these rural libraries offer a diverse range of services and facilities that benefit their respective communities. However, findings of the study indicated an acute shortage of staff in almost all the surveyed libraries, with this factor, consequently, affecting services. One significant challenge faced by these libraries is the lack of ICT applications. Nevertheless, most librarians expressed positive attitudes towards the implementation of ICT in rural libraries, recognizing their potential to enhance library services and reach out to a wider audience. Based on the findings of the study, it is recommended that the government should provide the necessary ICT tools in order to provide ICT-based library services. The results of this study can contribute to the upgrading and restructuring of rural library collections, infrastructure, services, and facilities in developing countries.

1 Introduction

West Bengal is a state located in the eastern part of India. It is the fourth most populous state in India, with a population of over 91 million people. There are 23 districts in the state. The state’s literacy rate is 77.08 % (Office of the Registrar General, India 2011). The state covers a total area of 88,752 square kilometres and is bordered by Bangladesh to the east, Nepal and Bhutan to the north, and the Indian states of Odisha, Jharkhand, Bihar, Sikkim, and Assam to the south, west, and northeast respectively. The capital of West Bengal is Kolkata (erstwhile Calcutta) which is also the largest city in the state. West Bengal is known for its rich history, cultural diversity, and natural beauty.

The development of public libraries in West Bengal has a long and rich history dating back to the colonial era. During the colonial period, many public libraries were established in Bengal (including Bangladesh) with the efforts of the Britishers and missionary organizations. Calcutta was selected by Job Charnock, an East India Company official, as the location for a British trading settlement in 1690 (Pradhan and Tripathi 2010). However, after winning the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the British decided to build some prestigious academic institutions and libraries in Calcutta. Majumdar (2008) pointed out that the city of Calcutta was the first place in India where the British introduced the Western education system. The establishment of Calcutta Public Library in 1836 marked a crucial moment in the development of the public library movement in Bengal’s history (Dasgupta 1989; Munshi and Ansari 2022; Nair 2004; Ohdedar 1966; Saha 1989). However, after India’s independence in 1947, the government of West Bengal took on the responsibility of establishing and promoting public libraries in the state. Koner (1989, 209) highlighted that “762 government-controlled and sponsored public libraries had been set up by 1977 in West Bengal.”

The Left Front government in West Bengal played a significant role in the development of public libraries in the state. During their rule, which lasted from 1977 to 2011, the government took various measures to promote the growth of libraries and to make them more accessible to the people. One of the key initiatives taken by the Left Front government was the enactment of the West Bengal Public Library Act in 1979 (Government of West Bengal 1980). Thereafter, a significant quantitative shift in the number of government-sponsored libraries was seen (Bandyopadhyay 2008). Significantly, during the initial eight years of the Left Front government in West Bengal, the number of government-sponsored libraries saw a significant increase, and by 1985, it had more than doubled compared to the previous figure. Majumdar (2008, 176) mentions how “the Left Front Party opened a new chapter of growth and development of public libraries in West Bengal.”

As per the Department of Mass Education Extension and Library Services West Bengal, there are 2480 public libraries in West Bengal, comprising 13 government libraries, 2460 sponsored libraries, and seven government-aided libraries. Out of 2473 government and government-sponsored libraries, there is one state central library located in the capital city, besides one special library, 26 district libraries, 236 town/sub division libraries, and 2209 rural/area/primary unit libraries. Apart from these, there are 319 Community Library Cum-Information Centers that operate through the Gram Panchayat-established community-based organization. Currently, the Department of Mass Education Extension and Directorate of Library Services look after the West Bengal Public Library System. A three-tier public library system exists in every district, comprising of district libraries (DL), town/sub-division libraries (TL), and rural/primary/unit libraries (RL) (Department of Mass Education Extension and Library Services 2013).

2 Objectives of the Study

The primary objective of the current study is to evaluate the services and facilities offered by rural libraries in West Bengal. Furthermore, the study will also examine the significance of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) applications in rural libraries. The major objectives are mentioned below:

To know the staff strength in rural libraries of West Bengal;

To study the information resources available in the rural libraries;

To explore the infrastructure of rural libraries;

To examine the services and facilities provided by the rural libraries;

To know the perceptions of librarians towards the implementation of ICT applications on rural library operation and services;

To identify the constraints that librarians face in providing library services and facilities.

3 Literature Review

It was ardently stated that public libraries act as community centres, serve as entryways to local knowledge, and provide a platform for lifelong learning. According to Zaid and Popoola (2010), a public library’s responsibilities include: educating rural residents about information resources and encouraging them to use the resources; addressing the educational, economic, social, cultural, and informational needs of the community; converting the uneducated, illiterate, and neo-literate into potential users; and providing information on a wide range of topics, including agriculture, finance, public health, and other topics. By offering a wide range of information resources and different services, public libraries also benefit students, jobseekers, farmers, businessmen, retired persons, and other members of society (Munshi, Ansari, and Barsha 2022; Ramasamy 2003). Lal (2018, 310) mentioned that the “Public library is the only institution that can provide [an] equal chance to the society to access information needed through the latest technology with free of cost.”

The study by Ajithakumari and Francis (2015) suggested that public libraries in Kerela state of India should implement modern technologies, build new collections regarding agriculture and health science, and appoint trained professional staff. Elsewhere, Raju and Raju (2010) discussed the role of public libraries in South Africa; this study highlighted the contribution of public libraries in the reduction of illiteracy, poverty, and unemployment in Africa and South Africa. The authors noted:

In the African continent and in South Africa specifically, the public library should be more than an institution propagating democracy – it has to be an institution of democracy itself providing information to all, in the format that is most relevant and in a language that is most preferred (Raju and Raju 2010, 11).

Munshi and Ansari (2019) and Ansari and Munshi (2018) identified that public libraries assist their users by offering them reading materials. Moreover, public libraries in West Bengal regularly organize various programs with regards to education and recreation. Elsewhere, Warraich, Malik, and Ameen (2018) investigated the current status of public libraries in Pakistan and revealed that the majority of libraries have poor conditions with respect to their library collections, professional staff, infrastructure, and services. Researchers have also mentioned that the development of the public library system has received very little attention from political leadership and higher authorities. Sule (2003) revealed that the majority of rural public libraries in Nigeria faced different problems like an inadequate book collection, financial constraints, a shortage of staff, and a lack of modernization that were not allowing them to fulfil the desires of the rural user communities. An evaluative study was conducted by Azhikodan (2010), who critically investigated the current status of the public libraries in the Malabar district of Kerala state in India. Interestingly, no library under the study has adopted any book selection policy. Furthermore, not even one single district in the Malabar region follows the guidelines set by IFLA/UNESCO in 2001 with regard to book selection.

According to Nasir, Quaddus, and Islam (2006), a significant number of users were dissatisfied with rural library services and facilities in Bangladesh, with the majority of libraries operating without professional staff and with an obsolete collection. According to Baada et al. (2019), users of public libraries in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana expressed similar dissatisfaction due to non-availability of reading materials, both in print and electronic form. Omeluzor, Oyovwe-Tinuoye, and Emeka-Ukwu (2017) examined rural library services and facilities for rural development in Delta State, Nigeria. The findings show that the information needs of rural residents were not sufficiently met due to some obstacles, including a lack of awareness, outdated book collections, illiteracy, a language barrier, a shortage of professional staff, inadequate infrastructure, an absence of IT, etc. Another study by Salman, Mugwisi, and Mostert (2017) examined the issues that hampered access to and use of public library services in Nigeria. The authors found that unawareness of library services, inadequate reading materials, and a lack of information literacy skills were the major factors that affected library use and better services. Significantly, however, a positive response was found by Aslam and Sonkar (2018) in their study. They concluded that most of the users from public libraries in Lucknow, India were satisfied with services and facilities offered by them.

A recent study by Munshi, Ansari, and Barsha (2022) found that a very large number of job seekers and students are using rural library services to search academic and job-related information. According to the respondents, “rural libraries in West Bengal should implement modern technologies and provide ICT-based library services so that they may access resources available in different parts of the globe” (293). Mushtaq and Arshad (2022) revealed that the majority of users frequently visit public libraries in Lahore, Pakistan, for obtaining job-related information; they also believed that public libraries are community information centers that assist individuals in lifelong learning. Urhefe-Okotie, Okafor, and Ijiekhuamhen (2022) found that there is a significant relationship between library services and job performance of librarians and paraprofessional librarians in public libraries in South Nigeria. The study also established that paraprofessional librarians play a significant role in the provision of library services in public libraries in South Nigeria. Lenstra and Roberts (2023) examined the potential for public libraries to partner with health promotion initiatives in order to provide greater access to health information and resources in South Carolina in the United States. They found that public libraries are uniquely positioned to serve as health promotion partners due to their broad reach within their communities, their commitment to providing free and open access to information, and their ability to serve as trusted sources of health information.

Kohlburn et al. (2023) highlighted that public libraries in United States played a critical role in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing valuable resources and services to their communities. The authors argued that public libraries demonstrated their value as essential community resources during the pandemic, and that policymakers should recognize the importance of libraries and support them accordingly. However, researchers also identified several political challenges facing public libraries, including funding cuts and debates over whether libraries are essential services. Another study by Adle et al. (2023) examined the efforts of public libraries in the United States to promote health justice during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of the study revealed that public libraries in the United States made significant efforts to promote health justice during the pandemic, including providing access to reliable health information, offering virtual health programs and resources, and partnering with local health organizations to provide community-based health services. Sadra et al. (2023) revealed that Iranian public libraries face several challenges in storing and retrieving information, including a lack of funding, outdated technology, inadequate staffing, and limited access to information resources. The study also identified several opportunities for improvement, including the use of new technologies, the development of partnerships with other organizations, and the provision of training and professional development opportunities for librarians. Notably, the study suggests that public libraries in Iran can improve their services by adopting new technologies and developing partnerships with other organizations.

4 Methodology

The researchers employed a mixed-methods approach, combining both quantitative and qualitative methodologies to gather relevant data. Additionally, few more relevant secondary data sources were consulted, including internal annual reports (each rural library prepares an annual report in March every year), annual reports published by the Department of Mass Education Extension and Library Services, Government of West Bengal, and also various websites associated with the West Bengal Public Library System. These secondary data sources provided valuable supplementary information in conjunction with the primary data collected.

4.1 Target Population

Currently, the state of West Bengal is divided into five administrative divisions: Presidency, Medinipur, Burdwan, Malda, and Jalpaiguri. Each division consists of either four or five districts, resulting in a total of 23 districts across all divisions. Two districts were selected from each division using a lottery method. The selected districts are: Presidency division (Nadia and Howrah); Medinipur division (Bankura and Purulia); Burdwan division (Paschim Bardhaman and Birbhum); Malda division (Malda and Murshidabad); and Jalpaiguri division (Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar).

Rural libraries in these ten districts were the target population of this study. Table 1 shows the total number of government-sponsored rural libraries in ten districts, according to the Department of Mass Education Extension and Library Services (2013). It is worth mentioning that this study solely focused on assessing the services and amenities provided by rural libraries in West Bengal and, therefore, district and town/sub-division libraries were excluded from the survey.

Selected districts and number of rural libraries covered.

| S.N. | Division | District | No. of govt. sponsored public libraries | No. of govt. sponsored rural libraries | No. of rural libraries surveyed | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Presidency | Howrah | 136 | 123 | 13 | 10.5 |

| Nadia | 110 | 99 | 10 | 10.1 | ||

| 2. | Medinipur | Bankura | 130 | 122 | 13 | 10.6 |

| Purulia | 117 | 111 | 12 | 10.8 | ||

| 3. | Burdwan | Paschim Bardhaman | 61 | 53 | 6 | 11.3 |

| Birbhum | 124 | 113 | 12 | 10.6 | ||

| 4. | Malda | Malda | 105 | 95 | 10 | 10.5 |

| Murshidabad | 159 | 146 | 15 | 10.2 | ||

| 5. | Jalpaiguri | Alipurduar | 37 | 34 | 4 | 11.7 |

| Jalpaiguri | 73 | 65 | 7 | 10.7 | ||

| Total | 1052 | 961 | 102 | 10.6 | ||

4.2 Sampling Technique

To select the districts, researcher adopted the lottery method of sampling. Two districts were chosen from each division, making a total of ten districts as a target population. However, considering the substantial number of rural libraries in each district, a stratified sampling method was employed to select at least 10 % of the rural libraries from each district. The stratified sampling method involves dividing the population into subgroups or strata based on specific characteristics. From each subgroup, a random sample is then selected in proportion to its size or importance in the population, ensuring that the sample represents the entire population (Busha and Harter 1980). It is important to note that this study did not involve library users and supporting library staff, as they were not the specific focus of the investigation.

4.3 Data Collection Instruments

To gather the relevant data, the researchers employed a research approach that combined quantitative and qualitative methodologies. A structured questionnaire was used to conduct a quantitative survey followed by personal interviews with the respective librarians. The questionnaire consisted of five main sections: (1) library staff; (2) collection; (3) infrastructure; (4) services and facilities; and (5) perception regarding the implementation of ICT applications. During the interviews, librarians were asked about the challenges they have faced in providing effective services to their users. One of the researchers used a smartphone to record the discussion.

4.4 Data Collection and Analysis

One of the researchers personally visited 102 rural libraries and distributed the questionnaires to the librarians. Rural libraries in Nadia (10), Howrah (13), Bankura (13), Purulia (12), Birbhum (12), Malda (10), and Murshidabad (15), Paschim Bardhaman (6), Jalpaiguri (7), and Alipurduar (4) were physically visited (the list of selected surveyed libraries as shown in Appendix 1). It was observed that the librarians exhibited a positive attitude and enthusiastically filled in the questionnaires within a reasonable amount of time. The data were analyzed using MS-Excel.

5 Results

5.1 Library Staff

According to the Department of Mass Education and Extension and Library Services, each rural library in West Bengal has sanctioned two positions: one professional (librarian) and one non-professional (junior library attendant). Based on the data presented in Table 2, it is evident that out of the 102 surveyed libraries, only 32 (31.3 %) have full-time librarians. Additionally, 82 (80.3 %) libraries have junior library attendants.

Staff strength in rural libraries (N = 102).

| S.N. | Library staff | No. of libraries | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Staff strength | Librarian | 32 | 31.3 |

| Junior Library Attendant | 82 | 80.3 | ||

| 2. | Professional qualifications | Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) | 8 | 7 |

| Bachelor of Library and Information Science (BLIS) | 18 | 15.7 | ||

| Certificate course in Library and Information Science (CLIS) | 28 | 24.6 | ||

| No LIS qualifications | 60 | 52.6 | ||

| 3. | Work experiences | 12–15 years | 22 | 19.3 |

| 16–20 years | 30 | 26.3 | ||

| 21 years and above | 62 | 54.4 | ||

The minimum qualifications for librarians are Higher Secondary or its equivalents, a pass Certificate in Library and Information Science (CLIS) or a Bachelor degree in Library and Information Science (BLIS). To become a junior library attendant, candidates must pass class VIII standard from a recognized secondary school. When we asked about the qualifications of librarians/junior library attendants, it was found that 28 (24.6 %) of them obtained a Higher Secondary degree along with the CLIS, 18 (15.7 %) have a Bachelor’s degree with BLIS, and only eight (7 %) have completed a Bachelor’s degree with MLIS. It can be concluded from the results that the majority of the libraries are being managed by junior library attendants. Nevertheless, it was found that some of the junior library attendants had pursued a Bachelor’s degree with CLIS/BLIS through distance education after securing their job. It is worth noting that in some libraries, junior library attendants are managing the library despite not having any LIS qualifications. Regarding professional experience, a majority of the librarians/junior library attendants (N = 62, 54.4 %) stated that they have more than 21 years of professional experience. Notably, some junior library attendants reported that, with the passage of time, they have been able to gain confidence in handling various sections of the library.

5.2 Library Collections

Public libraries play a crucial role in providing life-long learning opportunities for people of all ages and backgrounds. They serve as community hubs for education and provide access to a wide range of resources and services including books, magazines, newspapers, etc. A discussion, in the following paragraphs, will be made regarding availability of different types of materials in surveyed libraries.

The study revealed that the majority of the libraries (N = 45, 44.1 %) have book collections ranging from 8001 to 10,000 followed by 18 (17.7 %) libraries with more than 10,000 books. Notably, only 16 libraries (15.7 %) have a collection of less than 6000 books (see Table 3).

Library collections of rural libraries of West Bengal (N = 102).

| S.N. | Information resources | Collections | No. of libraries | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Printed books (Title) | 1,000–6,000 | 16 | 15.7 |

| 6,001–8,000 | 23 | 22.5 | ||

| 8,001–10,000 | 45 | 44.1 | ||

| More than 10,000 | 18 | 17.7 | ||

| 2. | Number of daily newspapers subscribed | 1 | 74 | 72.6 |

| 2 | 20 | 19.6 | ||

| More than 2 | 8 | 7.8 | ||

| 3. | Number of magazines subscribed | 1–5 | – | – |

| 6–10 | 78 | 76.5 | ||

| 11–20 | 24 | 23.5 | ||

| 4. | Availability of non-books materials | Maps and atlas | 102 | 100 |

| CDs/DVDs | 102 | 100 | ||

| Photographs | 54 | 52.9 |

The librarians were further questioned about the number of newspapers regularly received in their libraries. Analyzed data in Table 3 showed that most of the libraries (N = 74, 72.6 %) were subscribing to one newspaper regularly. Only 20 (19.6 %) libraries were subscribing to two newspapers. These subscribed newspapers are available in the Bengali language. The most commonly subscribed newspapers in the libraries are Bartaman and Ajkal. Further, as shown in Table 3, 76.5 % of libraries (N = 78) subscribe to 6 to 10 magazines every year, while 23.5 % of libraries (N = 23) subscribe to 11 to 20 magazines. The majority of these magazines are in the Bengali language, with a few magazines also available in the English language. It is also worth pointing out that not a single library has an e-book collection or subscriptions to any e-magazines. When asked about the availability of non-book materials in their libraries, each surveyed library had three to five maps and atlases, while 54 libraries had old photograph collections.

5.3 Library Infrastructure

Some interesting information such as the total area, the number of reading rooms, and their seating capacity is given in Table 4. This table also shows whether surveyed libraries have separate rooms for children and senior citizens, space for parking vehicles, etc.

Rural libraries infrastructure (N = 102).

| S.N. | Library infrastructure | No. of libraries | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Total area covered by the libraries | 600–1,000 sq. ft. | 67 | 65.7 |

| 1000–1500 sq. ft. | 24 | 23.5 | ||

| Above 1500 sq. ft. | 11 | 10.8 | ||

| 2. | Availability of reading room | 1 | 24 | 22.5 |

| 2 | 72 | 70.7 | ||

| More than 2 | 6 | 6.8 | ||

| 3. | Seating capacity in reading room | 1–40 | 21 | 20.6 |

| 41–80 | 69 | 67.7 | ||

| More than 80 | 12 | 11.7 | ||

| 4. | Separate children’s section | Yes | 26 | 25.4 |

| No | 76 | 74.6 | ||

| 5. | Separate seminar hall | Yes | 28 | 27.4 |

| No | 74 | 72.6 | ||

| 6. | Separate section for senior citizens | Yes | 12 | 11.8 |

| No | 90 | 88.2 | ||

| 7. | Parking area | Yes | 68 | 66.6 |

| No | 34 | 33.4 | ||

As shown in Table 4, 11 libraries (10.8 %) cover an area of above 1500 square feet, followed by 24 libraries (23.5 %) which cover an area between 1000 to 1500 sq. ft., and 67 libraries (65.7 %) which cover 600 to 1000 sq. ft. The seating capacity of libraries varies depending on their size. The study found that 69 libraries (67.7 %) had a capacity of between 41 to 80 seats in their reading areas while 20.6 % of libraries (N = 21) had a capacity of up to 40 seats. Only 11.7 % (N = 12) of libraries had more than 80 seats in their reading areas (see Table 4). In total, 72 libraries (70.7 %) had two reading rooms for their users, while the rest (N = 24, 22.5 %) had only one room.

Out of 102 libraries, only 25.4 % libraries (N = 26) have a separated section for children. The remaining libraries reported that, due to the shortage of library space, they could not create a separate section; however, they do maintain children’s collections on separate bookshelves. Notably, only 27.4 % (N = 28) of the surveyed libraries possess separate rooms for the purpose of organizing cultural programs, holding important meetings, and conducting seminars, etc. It is noted that out of 102 libraries, only 12 (11.8 %) provide separate sections where senior citizens read newspapers and spend their leisure time. Significantly, the majority of libraries (N = 68, 66.6 %) have parking areas.

5.4 Services and Facilities

A public library has a responsibility to provide a wide range of services and various activities to their user communities in order to satisfy their information needs. This section examines different services and facilities available in surveyed libraries.

5.4.1 Access to the Library Services

IFLA’s guidelines (Koontz and Gubbin 2010) state that “Physical accessibility is one of the major keys to the successful delivery of public library services. Services of high quality are of no value to those who are unable to access them. Access to these services should be structured in a way that it maximizes convenience to users” (57). Accessibility of the library services includes library opening hours, mode of access to the collection, duration of book loan, etc. as shown in Table 5.

During the library visit, it was observed that the opening and closing times of rural libraries were different, however, total working time in all the libraries is seven hours. Fifty-eight of the studied libraries open at 11 a.m. IST time with the closing time of 6 p.m. IST. Twenty-nine libraries open at 12 p.m. IST with the closing time of 7 p.m. IST. Fifteen libraries open at 1 p.m. IST, with the closing time of 8 p.m. IST. These libraries are open six days a week except on state and national holidays.

Bona fide members are allowed to borrow one book and two books at a time for 15 days in 68 and 23 libraries respectively. Although renewal facility is also available in all libraries, these libraries do not impose any fine to their members up to 10 days of a delay. When librarians were asked how many books were issued on average each day, 74 libraries (72.6 %) mentioned that 30 to 60 books were issued. On the other hand, 19 libraries (18.6 %) said they were issuing up to 30 books every day.

5.4.2 Library Services and Facilities

The present study revealed that all the surveyed rural libraries in West Bengal provide a wide range of services and facilities to their users, thus assisting their users in getting the right information without any loss of time.

5.4.2.1 Reference Service

Among all the services provided by libraries, the reference service is one of the most vital. The present study found that all the libraries provide reference services to their users. Notably, 54 libraries (52.9 %) have reference collections ranging from 1001 to 2000 while 24 libraries (23.6 %) have more than 2000 as shown in Table 6.

Access to the rural library services (N = 102).

| S.N. | Access to the library services | No. of libraries | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Library working hours | 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. | 58 | 56.8 |

| 12 p.m. to 7 p.m. | 29 | 28.5 | ||

| 1 p.m. to 8 p.m. | 15 | 14.7 | ||

| 2. | Mode of access | Open access | 18 | 17.7 |

| Closed access | 22 | 21.5 | ||

| Both | 62 | 60.8 | ||

| 3. | Number of books lent per registered member at one time | One book | 23 | 22.6 |

| Two books | 68 | 66.6 | ||

| More than two books | 11 | 10.8 | ||

| 4. | Duration of book loan | Seven days | – | – |

| Fifteen days | 81 | 79.4 | ||

| More than fifteen days | 21 | 20.6 | ||

| 5. | Fine for overdue books | Yes | 25 | 25.5 |

| No | 77 | 75.5 | ||

| 6. | Average books issued per day | 1–30 | 19 | 18.6 |

| 30–60 | 74 | 72.6 | ||

| More than 60 | 9 | 8.8 | ||

Services and facilities offered by the rural libraries.

| S.N. | Library services and facilities | No. of libraries | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Mode of access to the reference collections | Open access | 11 | 10.8 |

| Closed access | 77 | 75.5 | ||

| Both | 14 | 13.7 | ||

| 2. | Number of reference collections | 1–1000 | 22 | 21.6 |

| 1001–2000 | 54 | 52.9 | ||

| More than 2000 | 26 | 25.5 | ||

| 3. | Number of children collections | 1–500 | 24 | 23.6 |

| 501–1000 | 57 | 55.8 | ||

| More than 1000 | 21 | 20.6 | ||

| 4. | Daily children visitors | 1–20 | 32 | 31.4 |

| 21–30 | 58 | 56.8 | ||

| Above 31 | 12 | 11.8 | ||

| 5. | Extension activities | Cultural programs | 92 | 89.2 |

| Seminars | 34 | 33.3 | ||

| User orientation program | 67 | 65.6 | ||

| Career counselling programs | 32 | 31.3 | ||

| Other activities | 26 | 25.4 | ||

| 6. | Community information service | Agricultural information | 65 | 63.7 |

| Health information | 48 | 47 | ||

| Transport information | 36 | 35.2 | ||

| Local and political news | 66 | 64.7 | ||

| Displaying job-related advertisements | 78 | 76.4 | ||

| Miscellaneous | 46 | 45 | ||

5.4.2.2 Children’s Services

Children’s interest in reading has been greatly influenced by public libraries. Typically, there is a separate children’s area with a variety of books, magazines, toys, etc. in every public library. IFLA’s guidelines state that the “public library has a special responsibility to meet the needs of children” (Koontz and Gubbin 2010, 19). The survey found that all libraries offer children’s services; however, very few libraries have a separate children’s section. The remaining librarians have reported that, due to the inadequate infrastructure, they are unable to create a separate section. Nevertheless, the collection with regard to children is kept in separate shelves exclusively for children. As shown in Table 6, 57 libraries (55.8 %) had children’s collections ranging from 501 to 1000; only 24 libraries (23.6 %) had up to 500 books for children. The collection includes children’s books (like Birbal Story, Alif Laila, Veem Story Series, Gopal Bar, short stories, biographies, children encyclopaedias, etc.), children’s magazines, toys, maps, a globe, etc. When asked how many children used the children’s collections every day, more than 50 % (N = 58, 56.8 %) of libraries indicated that there were typically 21 to 30 visits by children (Annual Report of the District Library Officers 2019–2020).

5.4.2.3 Extension Services

One of the important services, especially in a public library, is the extension service. The fundamental objective of the extension service “is to convert a library into a cultural and intellectual centre which provides an insight into the stream of knowledge. The library can be an effective facilitator of self-learning through its extension services” (Venkateswara 1974, 65). Interestingly, the study found that all surveyed rural libraries organize different types of extension services to encourage both library members and non-members. As shown in Table 6, 89.2 % of libraries organize various cultural programs every year on different occasions like Saraswati Puja, Rabindra Jayanti, Independence Day, International Mother Language Day, etc. Libraries also host a variety of events during the program, including musical performance plays, documentaries, readings of poetry and stories, mime shows, kid-friendly dance performances, drawing competitions, etc. (see Figure 1). Moreover, these cultural and re-creational activities provide members of society the chance to advance their social, physical, and intellectual well-being. Notably, an average of 100–150 members and non-members participate in cultural programs (Annual Report of the District Library Officers 2019–2020).

Cultural programme organized by Madanpur Sadharon Pathagar on the occasion of International Mother Language Day, February 21, 2019.

In addition to the cultural program, 34 rural libraries (33.3 %) occasionally organize various seminars/workshops on diverse topics. According to the previous Annual Reports (2011–2012), these libraries organized seminars/workshops on the “Role of Public Libraries in Developing Society,” “Contribution of Iswarchandra Vidyasagar,” “Preparation for Civil Service examinations,” “Strategies for cracking government jobs,” etc. A significant number of people actively participate in these seminars/workshops reported by the librarians.

Results in Table 6 show that 67 libraries (65.6 %) organize user education programs every year to increase awareness among the user communities about the use of library resources and services. These programs are also extremely beneficial to young users who are preparing for competitive examinations. A little less than a third of libraries (N = 32, 31.3 %) occasionally organize career counselling programs, and experts from different fields were invited to deliver talks for the potential jobseekers. Besides these extension services, some of the libraries also organize adult education programs covering different topics.

5.4.2.4 Community Information Services

Public libraries also serve as community information centers in our society by providing various types of information, such as local and national news, information regarding agriculture, health, transportation, consumer issues, travel, etc. IFLA guidelines as quoted in Koontz and Gubbin (2010, 23) state: “Public libraries are locally based services for the benefit of the local community and should provide community information services.”

Notably, findings of the study suggest that rural libraries offer a variety of community information services to rural communities, as shown in Table 6. More than 60 % of libraries (N = 65, 63.7 %) provide agriculture-related information. Librarians at these libraries reported that they frequently receive magazines from the Department of Agriculture, Government of West Bengal, with articles related to the cultivation of different crops, etc. Further, rural libraries also provide health information such as information about doctors and hospitals (N = 48, 47 %), transport information (N = 36, 35.2 %) (summer and winter vacation travel plans, travel guides, etc.), and display job-related advertisements from several newspapers on the notice board (N = 78, 76.4 %). The majority of the librarians reported that many rural residents find these services very beneficial.

5.4.3 Other Services and Facilities

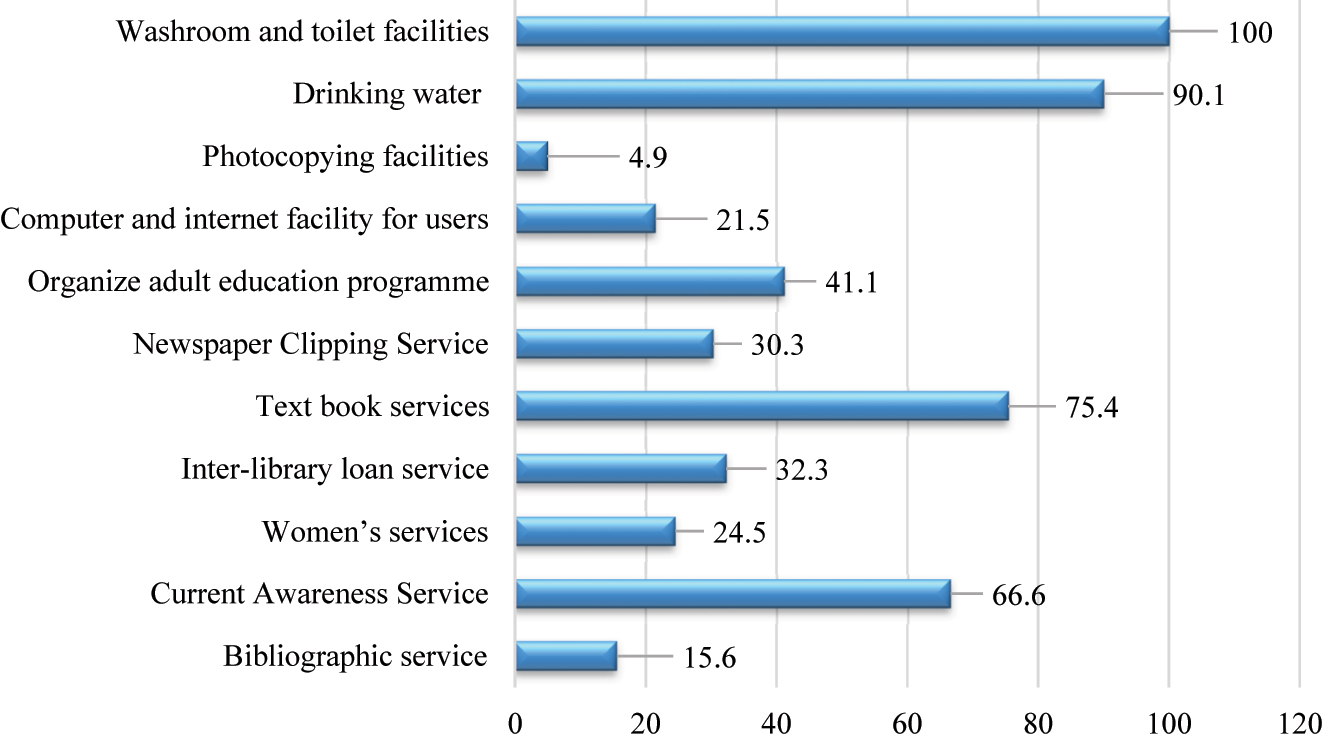

A bibliographic service denotes a list of documents provided by the library. As shown in Figure 2, out of 102 surveyed libraries, only 16 of them provide a bibliographic service. However, the rest of the libraries reported that due to a shortage of library staff, they are unable to provide a bibliographic service. Significantly, 68 (66.6 %) rural libraries display information regarding the new arrivals of books, journals, magazines, and other resources. However, a few libraries (N = 25, 24.5 %) provide women’s services. Librarians at these libraries reported that they organize International Women’s Day and awareness programs on several diseases, etc. (see Figure 3). It is important to note here that the majority of libraries (N = 77, 75.4 %) provide textbooks from eighth grade up to graduation level to needy students. Some non-government organizations (NGOs), members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs), and philanthropists have donated these textbooks to the libraries.

Other services and facilities provided by the libraries.

Celebration of International Women’s Day by the Abdul Halim Smriti Rural Granthagar, Birbhum District, March 8, 2017.

Photocopying services were discovered to be less common, with only five rural libraries (4.9 %) providing the service. When librarians were asked about the computer and internet facilities, only 22 libraries (21.5 %) provided such facilities. The rest of the libraries mentioned that they had not yet received computers and other necessary ICT tools from the state government. During the survey, the researchers found that around 100 % of rural libraries offer drinking water, washrooms facilities, and other public utilities.

5.5 Perception About the Implementation of ICT Applications

It was found that out of the 102 surveyed libraries, only 22 libraries have ICT equipment such as computers and printers. The librarians of these libraries reported that they have received only one computer and printer from the Raja Rammohun Roy Library Foundation through special grants. The Raja Rammohun Roy Library Foundation is an autonomous organization under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India. Its objectives are the establishment and development of public libraries, the promotion of library services, and the training of library personnel. The foundation also provides financial assistance to public libraries for the purchase of books, ICT equipment, and other necessary materials. However, the remaining librarians informed that they did not receive any ICT equipment from the government. Despite the era of digitization and modern ICT facilities, these libraries lack the essential equipment needed to provide ICT-based services. In light of this, the management of these 102 rural libraries were asked about their opinion on the necessity of adopting ICT in rural libraries. The responses are presented in Table 7, where each row represents a specific statement and each column represents a level of agreement ranging from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.”

Librarians’ perceptions regarding implementation of ICT applications in rural libraries (N = 102).

| S.N. | Necessity of ICT adoption in the rural libraries | SA | A | D | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I believe it is necessary that ICT applications are adopted by each rural library in West Bengal. | 68 (66.7 %) | 26 (25.5 %) | 8 (7.8 %) | – |

| 2. | I believe that ICT applications will improve the speed of technical processing and make documents available faster to users. | 62 (60.8 %) | 28 (27.4 %) | 12 (11.8 %) | – |

| 3. | I believe that ICT applications will provide numerous access points as well as a comprehensive subject catalogue. | 55 (53.9 %) | 34 (33.3 %) | 13 (12.8 %) | – |

| 4. | I believe that ICT applications will improve circulation activities in terms of speed and accuracy. | 25 (24.6 %) | 57 (55.8 %) | 20 (19.6 %) | – |

| 5. | I believe that ICT applications will reduce the workload of library professionals. | 19 (18.6 %) | 24 (23.5 %) | 42 (41.2 %) | 17 (16.7 %) |

| 6. | I believe that ICT applications will enable users to access library resources and services faster. | 48 (47 %) | 31 (30.4 %) | 13 (12.8 %) | 10 (9.8 %) |

| 7. | I believe that ICT applications will save the time of users. | 34 (33.3 %) | 58 (56.9 %) | 10 (9.8 %) | – |

| 8. | I believe that ICT applications will provide users with wider access to electronic resources. | 26 (25.5 %) | 67 (65.7 %) | 9 (8.8 %) | – |

| 9. | I believe that ICT applications will solve the problem of the needy and poor rural inhabitants applying for various online applications for jobs and other competitive examinations. | 60 (58.9 %) | 28 (27.4 %) | 14 (13.7 %) | – |

| 10. | I believe that ICT applications will enhance the overall library quality of rural library services and facilities. | 77 (75.5 %) | 12 (11.8 %) | 9 (8.8 %) | 4 (3.9 %) |

-

Note: SA = strongly agree; A = agree; D = disagree; SD = strongly disagree.

The results show that a majority of librarians (N = 95, 93.1 %) are of the opinion that ICT applications must be adopted by rural libraries in West Bengal. The results in Table 6 indicated that a large number of librarians agree that ICT applications will improve the speed of technical processing and make bibliographic information faster for the users for providing numerous access points. Through ICT, libraries can provide a range of the services for their users. On contrary, the results also show that most of the librarians (N = 59, 57.8 %) disagree and strongly disagree with the statement that ICT applications will reduce the workload of library professionals.

5.6 Problems Faced by the Librarians

One of the researchers approached each librarian/person-in-charge for a face-to-face interview at the end of the survey. During the interview, only two questions were asked: (1) what are the problems they encountered in managing and providing services to their patrons?; and (2) based on their experiences, what recommendations do they have for addressing these issues? After analyzing the recorded conversations, the researchers identified five major critical challenges that were reported by the librarians.

5.6.1 Shortage of Staff

According to the Directorate of Library Services, West Bengal, there are two sanctioned posts for each rural library, one professional and one non-professional. The study found that more than 80 % of libraries (N = 86) are functioning with a single staff member. Librarians reported that many public libraries are facing serious problems and libraries might be closed due to acute shortage of staff. The researchers investigated the reasons for the large number of vacant positions in these libraries and discovered that no recruitment drive had been held since 2010. Therefore, all the librarians have recommended that the government of West Bengal should start recruitment immediately in order to fill the vacant posts.

5.6.2 Absence of ICT Tools

Lack of modernization is such a major issue that 78 % (N = 80) of librarians have raised it. They reported that they have still not received computers and other equipment for automation from the authority. The majority of librarians indicated that they are unable to offer computerised services due to the absence of computers in their library. It is noteworthy to mention here that many of them believed that “this is one of the major reasons that the number of users is decreasing day by day.” Furthermore, they have also suggested that the government should provide an adequate number of computers and other ICT tools so that the library services can be made up in accordance with contemporary technology.

5.6.3 Inadequate Library Collection

Around 60 % of librarians indicated that due to the limited number of books, they are unable to provide information to jobseekers. Furthermore, more than 70 % of librarians reported that they subscribe to only one newspaper due to a limited annual budget. Notably, almost all the librarians believed that the annual budget should be increased by the government to cater to the informational needs of their users.

5.6.4 Lack of Infrastructure

More than 70 % of librarians claimed that due to the shortage of library infrastructure, they are unable to offer separate children’s and women’s sections. Most of the libraries are functioning without a separate seminar hall. However, some of the librarians also reported that their libraries are running in ramshackle buildings that need urgent repair to make these buildings fully functional.

5.6.5 Lack of Financial Support

Most of the public librarians suffer from a lack of adequate funding, which limits their ability to maintain their collections, services, and infrastructure. Besides the above challenges, many librarians also reported that issues like lack of support from the higher authority, unawareness regarding library services, outdated reference collections, a lack of cooperation among the librarians, etc. are critical challenges for providing effective services and facilities.

6 Conclusion

Rural libraries in West Bengal offer a wide range of services and facilities to cater to the information needs of their users. However, due to an acute shortage of staff, the services are hampered. Many librarians believed the vacant staff positions had a detrimental impact on routine services provided by them; having an adequate number of staff members would greatly enhance the quality of services offered to library users. A lack of ICT tools have further compounded already existing problems. In terms of library collections, all rural libraries possess modest-sized print collections. However, there is a lack of emphasis on developing e-book collections and subscribing to e-magazines.

The findings suggested that the Directorate of Library Services in West Bengal should provide rural libraries with essential ICT applications and skilled personnel to facilitate the provision of ICT-based services. Therefore, it is highly recommended that such measures be taken to improve the quality of services offered by rural libraries in the region. So far, it can be inferred from the literature reviewed that this is one of the studies that pays attention to the services provided by the rural libraries in West Bengal. However, the study’s findings can be instrumental in enhancing and revamping the collections, infrastructure, services, and facilities of rural libraries in developing nations.

The survey responses indicate a strong consensus among librarians regarding the necessity of ICT adoption in rural libraries and the potential benefits it can bring. However, there are also reservations and concerns expressed by some respondents regarding the practicality and effectiveness of implementing ICT applications in certain areas. Several serious challenges were highlighted by the librarians in managing and delivering services to patrons. These challenges include staff shortages, absence of ICT tools, inadequate library collections, insufficient infrastructure, evolving user needs and demands, and limited financial support. The librarians also mentioned other issues, such as a lack of support from higher authorities, outdated reference collections, and a lack of cooperation among librarians. Undoubtedly, despite all these constraints, rural libraries have been serving inhabitants in a remarkable way.

| S.N. | Name of the library | District | Year of establishment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Prodyot Smriti Pathagar | Nadia | 1943 |

| 2. | Palsunda Sadharan Granthagar | 1971 | |

| 3. | Bankim Smriti Gramin Pathagar | 1973 | |

| 4. | Biplabi Kabi Sukanta Pathagar | 1978 | |

| 5. | Sukanta Smriti Gana Pathagar | 1979 | |

| 6. | Radhanagar Jagarani Sadharan Pathagar | 1954 | |

| 7. | Maliapota Juban Jagarani Samity & Pallisri Library. | 1961 | |

| 8. | Natidanga Tarun Samity Pathagar | 1959 | |

| 9. | Karimpur Public Library | 1967 | |

| 10. | Dnarermath Public Library | 1970 | |

| 11. | Howrah Seva Sangha | Howrah | 1942 |

| 12. | Sanskriti Rural Library | 1959 | |

| 13. | Rabindra Pathagar Parbakshi | 1951 | |

| 14. | Joypur Arya Samity | 1896 | |

| 15. | Manasri Sadharan Pathagar | 1967 | |

| 16. | Sridurga Sadharan Pathagar | 1955 | |

| 17. | Sukanta Smriti Pathagar | 1963 | |

| 18. | Maju Public Library | 1902 | |

| 19. | South Jhapordah Public Library | 1928 | |

| 20. | Dafarpur Ramkrishna Library | 1918 | |

| 21. | Jaynagar Deshbandhu Pathagar | 1945 | |

| 22. | Bainan Public Library | 1919 | |

| 23. | Rabindra Pathagar, Bangalpur | 1943 | |

| 24. | Gobindapur Public Library | Purulia | 1957 |

| 25. | Ladhurka Palli Pathagar | 1956 | |

| 26. | Vivekananda Pathagar | 1947 | |

| 27. | Najrul Smriti Sahitya Pathagar | 1978 | |

| 28. | Adhar Smriti Bani Mandir | 1946 | |

| 29. | Barabhum Public Library | 1958 | |

| 30. | Amal Smriti Pathagar | 1968 | |

| 31. | Janata Library | 1960 | |

| 32. | Debiprashad Memorial Library | 1968 | |

| 33. | Netaji Subhas Library | 1982 | |

| 34. | Universal Club & General Library | 1956 | |

| 35. | Burda Tarun Sanga Library | 1945 | |

| 36. | Jhanti Pahari Rural Library | Bankura | 1957 |

| 37. | Kharbona Adibashi Gramin Granthagar | 1987 | |

| 38. | Rajgram Milani Sangha Library | 1963 | |

| 39. | Pourabarta Library | 1980 | |

| 40. | Barajora Bandhab Samiti Library | 1958 | |

| 41. | Bibarda Jagriti Sangha Pathagar | 1975 | |

| 42. | Radhanagar Agradut Club Pathagar | 1975 | |

| 43. | Punisole Ajimia Gramin Granthagar | 1979 | |

| 44. | Kakra Dara Milani Sangha Library | 1960 | |

| 45. | Raipur Rural Library | 1941 | |

| 46. | Tilaboni Udayan Club Pathagar | 1981 | |

| 47. | Tiluri Rural Library | 1959 | |

| 48. | Saltora Rural Library | 1951 | |

| 49. | Illambazar Rural Library | Birbhum | 1958 |

| 50. | Samssuzzoha Zakia Public Library | 1938 | |

| 51. | Sidhu Kanu Smriti Pathagar | 1983 | |

| 52. | Rupaspur Sailajananda Smriti Pathagar | 1982 | |

| 53. | Lokpur Agrani Rural Library | 1958 | |

| 54. | Najrul Sukanta Pathagar, Chinpai | 1980 | |

| 55. | Balijuri Rural Library | 1957 | |

| 56. | Hetampur Ramranjan Sadharan Pathagar | 1947 | |

| 57. | Udaynagar Gramin Granthagar | 1981 | |

| 58. | Bhabanipur Rural Library | 1981 | |

| 59. | Mohurapur Public Library | 1960 | |

| 60. | Abdul Halim Smriti Granthagar | 1995 | |

| 61. | Subhas Library | Paschim Burdwan | 1947 |

| 62. | Kandeswar Tarun Sangha Library | 1961 | |

| 63. | North Zone Community Centre Library | 1970 | |

| 64. | Progati Granthagar | 1976 | |

| 65. | Andal Gram Progati Pathchakra Gramin Granthagar | 1954 | |

| 66. | Panagarhgram Chatra Samity Rural Library | 1972 | |

| 67. | Sahid Subodh Sukhit Pathagar | Malda | 1971 |

| 68. | Matoil Nabarun Sangha Rural Library | 1964 | |

| 69. | Basanti Gramin Pathagar | 1979 | |

| 70. | Kumar Shibapada Memorial Institute | 1937 | |

| 71. | Baidyanathpur Sanskriti Pathagar | 1978 | |

| 72. | Raigram Library | 1953 | |

| 73. | Sukanta Pathagar | 1979 | |

| 74. | Bachamari Kabi Bharati Bhawan Sadharan Pathagar | 1947 | |

| 75. | Anneswa Granthagar | 1990 | |

| 76. | Norhatta Club & Library | 1954 | |

| 77. | Trimohini Progressive Union Rural Library | Murshidabad | 1969 |

| 78. | Sarbodaya Sangha Rural Library | 1967 | |

| 79. | Netajee Pathagar | 1948 | |

| 80. | Kalitala Shridurga Library | 1951 | |

| 81. | Sargachhi Ramkrishna Mission Library | 1897 | |

| 82. | Kazisaha Nazrul Library | 1967 | |

| 83. | Maharaja Manindra Chandra Nandi Shahar Granthagar | 1998 | |

| 84. | Bankim Chandra library | 1905 | |

| 85. | Raghunath Club Govt. Sponsored. Rural Library | 1971 | |

| 86. | Raghunathpur Deshbandhu Pathagar | 1961 | |

| 87. | Benadaha Siraj Smriti Pathagar | 1978 | |

| 88. | Jitpur Public Library | 1978 | |

| 89. | Pashla B.K.M. Library | 1960 | |

| 90. | Saraswati Library | 1910 | |

| 91. | Mangal Jan Rural Library | 1976 | |

| 92. | Tarun Pathagar | Alipurduar | 1948 |

| 93. | Newtown Library | 1958 | |

| 94. | Vivekananda Club & Library | 1981 | |

| 95. | Sonapur Club-cum Library | 1957 | |

| 96. | Milan Sangha Library | Jalpaiguri | 1971 |

| 97. | Young Star Cultural Club Library | 1982 | |

| 98. | Gourgram Palli mangal Pathagar | 1981 | |

| 99. | Sri Sri Nigamananda Pathaga | 1961 | |

| 100. | Tarun Sangha O Granthagar | 1978 | |

| 101. | Belakoba Public Library | 1953 | |

| 102. | Jalpesh Mahikanta Pathagar | 1955 |

References

Adle, M., J. Behre, B. Real, and B. S. Jean. 2023. “Moving toward Health Justice in the COVID-19 Era: A Sampling of US Public Libraries’ Efforts to Inform the Public, Improve Information Literacy, Enable Health Behaviors, and Optimize Health Outcomes.” The Library Quarterly 93 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1086/722553.Search in Google Scholar

Ajithakumari, V. P., and A. T. Francis. 2015. “Public Library System in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala: An Investigation.” SRELS Journal of Information Management 52 (6): 465–70. https://doi.org/10.17821/srels/2015/v52i6/84324.Search in Google Scholar

Annual Report of the District Library Officers (2019–2020). Internal Library Reports of District Library Officers, West Bengal. Unpublished Documents.Search in Google Scholar

Ansari, M. A., and S. A. Munshi. 2018. “Building Public Library Collection in India: A Study of Book and Non-book Material.” Library Philosophy and Practice, 1–21. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2041 (accessed July 19, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Aslam, S., and S. K. Sonkar. 2018. “Perceptions and Expectations of Public Library Users in Lucknow (India): A Study.” Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2034 (accessed July 19, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Azhikodan, S. 2010. Public Libraries in Malabar. New Delhi: Serials Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Baada, F. N. A., P. Baayel, S. Bekoe, and S. Banbil. 2019. “Users’ Perception of the Quality of Public Library Services in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana: An Application of the LibQUAL+ Model.” Library Philosophy and Practice, 1–33. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5834&context=libphilprac (accessed July 19, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Bandyopadhyay, A. K. 2008. Our Public Libraries: Evaluation of the Public Library Services in West Bengal. Burdwan: Burdwan University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Busha, C. H., and S. P. Harter. 1980. Research Methods in Librarianship Techniques and Interpretation. New York: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Dasgupta, K. 1989. “The National Library.” In National Library and Public Library Movement: In 150th Anniversary of the Calcutta Public Library, edited by K. Dasgupta, 3–13. Calcutta: National Library of India.Search in Google Scholar

Department of Mass Education Extension and Library Services. 2013. Annual Report 2011-2012. Kolkata: Government of West Bengal.Search in Google Scholar

Government of West Bengal. 1980. West Bengal Act XXXIX of 1979. The West Bengal Public Libraries Act, 1979. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/14547/1/1979-39.pdf (accessed February 5, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Kohlburn, J., J. Bossaller, H. Cho, H. Moulaison-Sandy, and D. A. Adkins. 2023. “Public Libraries and COVID-19: Perceptions and Politics in the United States.” The Library Quarterly 91 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1086/722547.Search in Google Scholar

Koner, S. S. 1989. “Impact of Public Library Legislation on the Socio-Economic Development of West Bengal: A Critical Study of West Bengal Public Libraries Act 1979.” Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Library and Information Science. Burdwan: Department of Library and Information Science, University of Burdwan. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/68583 (accessed February 28, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Koontz, C., and B. Gubbin, eds. 2010. IFLA Public Library Service Guidelines. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur. https://www.ifla.org/publications/ifla-publicationsseries-147 (accessed May 2, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Lal, J. 2018. “The Role of Public Libraries in Socio-Cultural Development in Rural Areas in India.” Library Progress 38 (2): 299–313. https://doi.org/10.5958/2320-317x.2018.00032.6.Search in Google Scholar

Lenstra, N., and J. Roberts. 2023. “Public Libraries and Health Promotion Partnerships: Needs and Opportunities.” Evidence Based Library and Information Practice 18 (1): 76–99. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip30250.Search in Google Scholar

Majumdar, K. 2008. Paschimbange Sadharan Granthagar Byabasthar Prasar o Bangiya Granthagar Parisad (in Bengali) [Development of Public Library Services in West Bengal and Bengal Library Association]. Kolkata: Bengal Library Association.Search in Google Scholar

Munshi, S. A., and M. A. Ansari. 2019. “Century Old Public Libraries in Nadia District, West Bengal: A Study on Their Contribution and Impact.” IASLIC Bulletin 64 (2): 97–107.Search in Google Scholar

Munshi, S. A., and M. A. Ansari. 2022. “Evolution of Public Libraries in West Bengal, India: Role of the Britishers, Library Associations and Contemporary Political Parties.” International Information & Library Review 54 (2): 115–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2021.1922963.Search in Google Scholar

Munshi, S. A., M. A. Ansari, and S. Barsha. 2022. “The Contributions of Public Libraries to Satisfy Intellectual Curiosity of Rural Inhabitants in West Bengal: An Indian Case Study.” Libri – International Journal of Libraries and Information Services 72 (3): 279–96. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2021-0085.Search in Google Scholar

Mushtaq, A., and A. Arshad. 2022. “Public Library Use, Demographic Differences in Library Use and Users’ Perceptions of Library Resources, Services and Place.” Library Management 43 (8/9): 563–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/lm-10-2021-0093.Search in Google Scholar

Nair, P. T. 2004. Origin of the National Library of India, Days of the Calcutta Public Library. Kolkata: National Library of India.Search in Google Scholar

Nasir, M. U., M. Quaddus, and M. S. Islam. 2006. “Socio-economic-cultural Aspects and Mass Information Need: The Case of Public Library Uses in Bangladesh.” Library Management 27 (9): 636–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435120610715536.Search in Google Scholar

Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India. 2011. “Census of India (2011).” http://censusindia.gov.in/Ad_Campaign/Referance_material.html (accessed April 12, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Ohdedar, A. K. 1966. The Growth of the Library in Modern India 1498–1836. Calcutta: World Press.Search in Google Scholar

Omeluzor, S. U., G. O. Oyovwe-Tinuoye, and U. Emeka-Ukwu. 2017. “An Assessment of Rural Libraries and Information Services for Rural Development: A Study of Delta State, Nigeria.” The Electronic Library 35 (3): 445–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/el-08-2015-0145.Search in Google Scholar

Pradhan, D., and T. Tripathi. 2010. Public Libraries Information Marketing and Promotion: A Special Reference for Darjeeling District of West Bengal. Kolkata: Levant Books.Search in Google Scholar

Raju, R., and J. Raju. 2010. “The Public Library as a Critical Institution in South Africa’s Democracy: A Reflection.” LIBRES Library and Information Science Research Electronic Journal 20 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.32655/libres.2010.1.4.Search in Google Scholar

Ramasamy, R. 2003. Status of State Central Library in India: An Analytical Study. Delhi: Gyan Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Sadra, F., S. Ziaei, S. Ghaffari, and H. Ghazizadeh. 2023. “Challenges and Opportunities for Storing and Retrieving Information in Iranian Public Libraries from the Viewpoints of Librarians.” International Journal of Information Science & Management 21 (1): 261–73. https://doi.org/10.22034/ijism.2022.1977714.0.Search in Google Scholar

Saha, R. K. 1989. “Library Movement in West Bengal.” In National Conference on Library Movement in India, edited by R. K. Saha, 132–7. Calcutta: Bengal Library Association.Search in Google Scholar

Salman, A. A., T. Mugwisi, and B. J. Mostert. 2017. “Access to and Use of Public Library Services in Nigeria.” South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science 83 (1): 26–38. https://doi.org/10.7553/83-1-1639.Search in Google Scholar

Sule, N. N. 2003. “The Contributions of Rural Library Services of Literacy Development in Nigeria: A Review of the Past Centenary and Prospect of the New Millennium.” Library Progress 23 (2): 133–41.Search in Google Scholar

Urhefe-Okotie, E. A., V. N. Okafor, and O. P. Ijiekhuamhen. 2022. “A Comparative Study of Library Services and Job Performance of Librarians and Paraprofessional Librarians in Public Libraries in South-South Nigeria.” Performance Measurement and Metrics 23 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/pmm-11-2019-0054.Search in Google Scholar

Venkateswara, R. L. 1974. “Opening of School and College Libraries to Public.” In New Horizons in Library and Information Science, edited by C. P. Vashisth. Madras: T. R. Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Warraich, N. F., A. Malik, and K. Ameen. 2018. “Gauging the Collection and Services of Public Libraries in Pakistan.” Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication 67 (4/5): 244–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/gkmc-11-2017-0089.Search in Google Scholar

Zaid, Y. A., and S. O. Popoola. 2010. “Quality of Life Among Rural Nigerian Women: The Role of Information.” Library Philosophy and Practice. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/513 (accessed April 22, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Rural Libraries as Providers of Life-long Learning Opportunities: An Appraisal of Information Services and Facilities in West Bengal

- Assessing the Use of Scholarly Communication Platforms in Zambia

- Big Data Analytics Implementation and Practices in Medical Institute Libraries of Pakistan

- Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students’ Needs and Expectations of Digital Scholarship Spaces in a Comprehensive University Library: A Survey

- Knowledge-Sharing Strategies for Poverty Eradication Among Rural Women

- Who Seeks and Shares Fact-Checking Information? Within the Context of COVID-19 in South Korea

- A Study on the Analysis of Public User Expectations for the Metaverse Library Services

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Rural Libraries as Providers of Life-long Learning Opportunities: An Appraisal of Information Services and Facilities in West Bengal

- Assessing the Use of Scholarly Communication Platforms in Zambia

- Big Data Analytics Implementation and Practices in Medical Institute Libraries of Pakistan

- Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students’ Needs and Expectations of Digital Scholarship Spaces in a Comprehensive University Library: A Survey

- Knowledge-Sharing Strategies for Poverty Eradication Among Rural Women

- Who Seeks and Shares Fact-Checking Information? Within the Context of COVID-19 in South Korea

- A Study on the Analysis of Public User Expectations for the Metaverse Library Services