The impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on chronic stress assessed by hair cortisol analysis via LC-MS/MS

-

Sara Casati

Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown measures have had profound effects on mental health worldwide. This study aimed to assess changes in long-term stress levels across three distinct time periods – pre-lockdown, during lockdown, and post-lockdown – by measuring cortisol concentrations in hair samples.

Methods

Hair samples were collected from 87 individuals referred to our forensic toxicology laboratory during 2020. When possible, each hair sample was segmented to reflect the pre-lockdown, lockdown, and post-lockdown periods. Cortisol, a validated biomarker of chronic stress, was quantified in each segment using a newly developed and fully validated liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method. Statistical comparisons between periods were performed using ANOVA followed by post hoc analyses.

Results

Cortisol concentrations showed a statistically significant increase in the post-lockdown period (median 3.68 pg/mg) compared to both pre-lockdown (median 2.28 pg/mg) and lockdown (median 3.06 pg/mg) periods. Subgroup analyses revealed that females and young adults (17–24 years) exhibited the most pronounced increases in cortisol levels across time points. Notably, 76 % of individuals with complete three-segment profiles showed higher cortisol concentrations in the post-lockdown period compared to pre-lockdown, suggesting a sustained psychological burden.

Conclusions

Hair cortisol analysis revealed a consistent elevation in stress biomarkers during and after the COVID-19 lockdown, particularly among females and younger individuals. These findings highlight the enduring psychosocial impact of the pandemic and support the use of segmental hair analysis as a powerful tool for retrospective assessment of chronic stress in population studies.

Introduction

The recent critical period of the COVID-19 pandemic exposed individuals to exceptionally challenging living conditions. The pervasive feelings of loneliness, confusion, and widespread unemployment significantly elevated the risk of psychological distress within the population [1]. In Italy, specifically, approximately one-third to half of the population reported experiencing COVID-19-related mental distress during the initial months of the pandemic [2], 3]. Such profound psychological impacts can manifest in various adverse mental health consequences, including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, self-harm, and even suicide [4], [5], [6]. These psychological reactions are also likely to influence other health-related behaviors [7].

In recent years, the evaluation of hair cortisol has emerged as a suitable and reliable biomarker for assessing an individual’s exposure to chronic stressful events. Hair cortisol concentrations provide a unique retrospective insight, reflecting the cumulative cortisol production over the period of hair growth. Similar to the analysis of other substances, these levels can be assessed retrospectively for several months [8], 9]. Previous research, such as the study by Stalder et al. [10], estimated an approximate 22 % increase in hair cortisol concentrations in groups exposed to long-term stress (e.g., work stress), with a more pronounced effect if the chronic stress was ongoing at the time of analysis [11], 12]. Elevated hair cortisol levels have also been observed in specific vulnerable populations, including caregivers of patients with dementia [13] and individuals suffering from burnout [14]. Recently, significantly higher hair cortisol values have been assessed in adolescents with parental physical abuse [15] as well as in students during the exam period [16].

Regarding the methodological procedures, the current hair cortisol literature does not rely on a standardized protocol, making comparisons between findings challenging and hindering consistency across studies. The methods of measuring hair cortisol may vary widely in different process steps as extensively revised in a recent meta-analysis [17]. For example, washing procedures (isopropanol, methanol, acetone), number of washes (from one to three times), grinding of hair using a ball mill or mincing hair with scissors and extraction solution (methanol, methanol and acetone, ethanol, NaOH) have been reported in published studies. In recent years, advanced liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) techniques have substantially improved the specificity and sensitivity of hair cortisol analysis. For instance, an automated online SPE LC-MS3 method has enabled simultaneous determination of cortisol and cortisone in human hair with high selectivity and minimal matrix interference [18]. More recently, an improved LC-MS/MS protocol using pulverization and solid-phase extraction was developed, allowing accurate quantification of cortisone and cortisol in human scalp hair with low sample volume [19] Lastly, an innovative approach was designed by van Harskamp et al. [20] to achieve complete cortisol extraction through the enzymatic digestion of hair. Based on the compelling available data, we considered hair cortisol evaluation a highly relevant biological marker for assessing long-term stress. A limited number of studies have specifically investigated the effects of the pandemic on stress markers. For instance, Ibar et al. [21] evaluated hair cortisol levels in healthcare workers at a University Hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic, revealing that 40 % of the studied population exhibited altered hair cortisol values. Similarly, Rajcani et al. [11] measured hair cortisol levels in nurses and identified significant differences between samples reflecting the period before and during the COVID-19-related state of emergency, with higher levels observed during the first wave of the pandemic in Slovakia. Taking into consideration these findings, our study aimed to measure cortisol levels in hair samples obtained from patients admitted to our laboratory during the pandemic. The objective was to identify potential differences in stress markers across distinct time periods, such as before and after the lockdown.

Highlights

A fully LC-MS/MS method was developed and validated for sensitive and accurate quantification of cortisol in human hair.

Cortisol concentrations increased significantly during the lockdown and post-lockdown periods, reflecting sustained psychological stress.

Age-related analysis indicated that although increases were most marked in younger adults, elevated cortisol was observed across all age groups.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

The reference standard cortisol and its deuterated internal standard, cortisol-d4 (IS), were procured from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) at respective quantities of 1 g and 0.5 mg. Ultrapure water (H2O), acetonitrile (ACN), 98 % formic acid (HCOOH) and dichloromethane (DCM), were obtained as analytical grade reagents from Carlo Erba (Milan, Italy). Methanol (MeOH) of HPLC grade (99.9 %) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). LC/MS grade MeOH was obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany).

Equipment

Analyses were performed on a 1290 Infinity UHPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) coupled to a QTRAP 5500 triple quadrupole linear ion trap MS (Sciex, Darmstadt, Germany), equipped with an ESI source. Compounds were separated on a Kinetex LC XB-C18 column (100 mm length × 2.1-mm i.d, 2.6 µm particle size) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) at 30 °C using 0.1 % formic acid in H2O (A) and 0.1 % formic acid in ACN (B) as mobile phases, with the following 10-min linear gradient: 0.0–0.50 min (85 % A, 15 % B), 0.50–2.0 min (75 % A, 25 % B), 2.0–5.0 min (65 % A, 35 % B), 5.0–6.5 min (2.0 % A, 98 % B), 6.5–8.0 min (2.0 % A, 98 % B), 8.0–8.1 min (85 % A, 15 % B), 8.1–10 (85 % A, 15 % B). The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min and the injection volume was 5 µL. The MS parameters were optimized by direct infusion of a standard mix solution (cortisol and cortisol-d4, 100 ng/mL) as follows: curtain gas, ion gas 1, and ion source gas 2 were set at 25, 50, and 55 psi (pound per square inch) respectively, the source temperature was 500 °C, the ionization voltage was 5,500 eV, the entrance potential was 6 and 8 eV for cortisol and its deuterated, respectively. MS acquisitions were performed by multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The MRM conditions and parameters including ion transitions, de-clustering potential (DP), and collision energy (CE) are provided in Table 1. Data acquisition and processing were performed using Analyst®1.7.1 and Sciex OS-Q®1.6 software (Sciex, Darmstadt, Germany), respectively.

Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) parameters: precursor and product ions (target (T) and qualifier (Q) for cortisol and cortisol-d4, de-clustering potential (DP) and collision energy (CE)).

| Compound | Retention time, min | Precursor ion, m/z | Products ions, m/z | DP, eV | CE, eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | 3.78 | 363.3 | 121.5 (T) 327.3 (Q) |

90 90 |

38 23 |

| Cortisol-d4 | 3.76 | 367.3 | 121.2 (T) 331.5 (Q) |

110 110 |

34 23 |

Cortisol validation procedure

Method validation was conducted in accordance with international recommendations for the validation of analytical methods [22]. Selectivity was assessed using cortisol-free distal hair samples (25 mg) defined as hair longer than 30 cm, with and without the addition of IS (blank and zero samples). Linearity was assessed by analysis of eight calibration levels (0, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 pg/mg) with seven replicates (n=7) for each level. Linearity was determined by plotting the peak area ratios of the analytes to the IS against the nominal analyte concentration, employing a weighted 1/x2 linear regression. Sensitivity was expressed in terms of limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ). The LOQ was defined as the lowest concentration at which precision and accuracy values were within ± 20 % and a signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio of the peak areas was ≥10. The LOD was defined as the lowest concentration with an S/N ratio of the peak areas ≥3. Precision and accuracy were determined at all calibration levels through the analysis of seven independent replicates of quality control (QC) samples, calculating the coefficient of variation (CV %) and the bias (BIAS %). CV and BIAS values below 15 % were deemed acceptable. The matrix effect (%) was determined by fortifying cortisol-free distal hair extracts and MeOH with increasing cortisol concentrations (5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 pg/mg, n=7 for each level) and comparing the mean peaks areas. The stability of cortisol in QCs extracts was assessed by comparing the response factor after 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 7 days at room temperature, after 7 days at 4 °C and after one freeze and thaw cycle with the original vial at T0.

Hair samples collection

Cortisol-free human hair samples were collected from volunteers and analyzed to exclude any source of chromatographic interferences. These samples were then mixed to obtain homogeneous pools of blank hair for cortisol calibrators and QCs. Hair was collected from 87 subjects tested in our laboratory during 2020. Each subject provided one proximal segment (3–6 cm from the scalp). When sufficient hair length was available, the sample was further divided into three consecutive segments, resulting in a total of 240 hair samples. Segments were classified according to the period of hair growth they represented, as follows: the most proximal segment reflecting the period following lockdown (2–3 months post-lockdown, post-L), the intermediate segment corresponding to the Italian first lockdown period (March 9th to May 18th, L), and the distal segment representing the pre-lockdown period (before March 9th, pre-lockdown, pre-L) (Figure 1). In instances of insufficient hair length, samples were divided into only two segments, corresponding to the Italian lockdown and the post-lockdown periods. All subjects included in this study provided written informed consent for the anonymous use of their samples for research purposes.

Schematic workflow of hair sample collection.

Sample preparation and extraction

All collected hair samples, obtained as described in the previous paragraph, were initially washed with 4 mL of DCM and 2 mL of MeOH (10 min) in ultrasonic bath subsequently dried at room temperature, and cut into small pieces (2–4 mm) using scissors. An aliquot (20–120 mg) from each sample was accurately weighed into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and used for cortisol extraction.

Following the initial preparation steps, hair matrices were spiked with 10 µL of cortisol-d4 (0.25 g/mL) as internal standard (IS), followed by the addition of 990 µL of MeOH. Incubation and extraction were performed overnight at room temperature, succeeded by an additional ultrasonication step for 2 h. The samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 g for 6 min. A 500 µL aliquot of the supernatant was collected from each sample and subsequently dried. The resulting dried residue was reconstituted with 80 µL of mobile phase (50 % H2O–0.1 % HCOOH, 50 % ACN – 0.1 % HCOOH). Finally, the supernatant was transferred into an autosampler vial, and a 5 µL aliquot was injected into the LC-MS/MS system for analysis.

Statistics

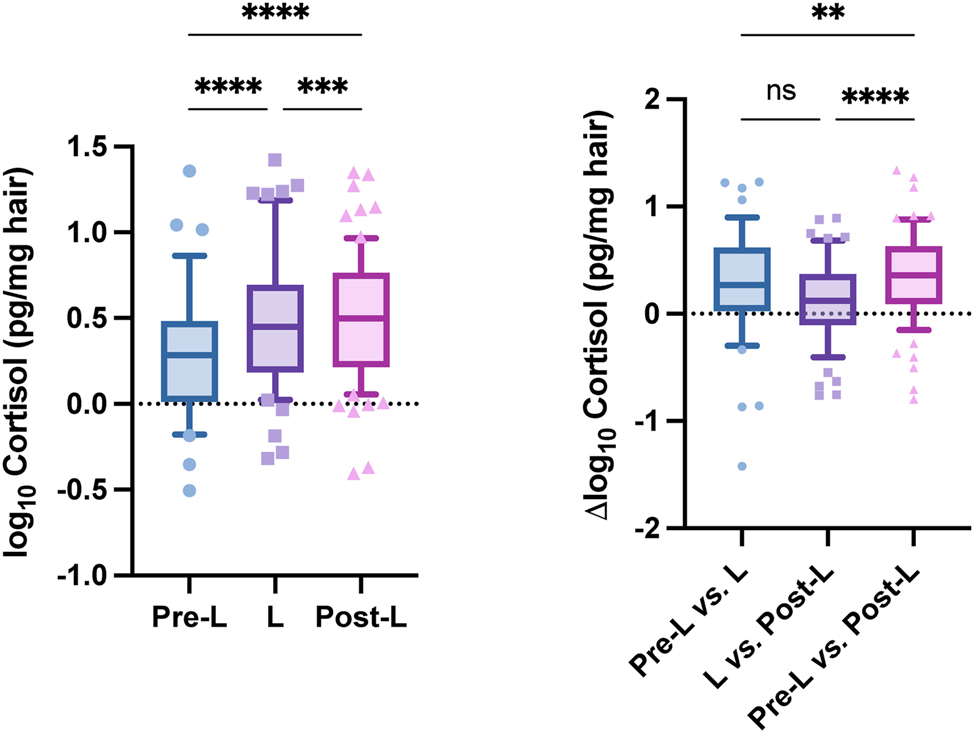

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (Graph- Pad Software, CA, USA). Hair samples (n=87) were categorized into three distinct groups: Pre-L, L, and Post-L. Data for each group and increments observed between groups are presented as box and whisker plots. In these plots, the box delineates the 25th to 75th interquartile range, with the horizontal line within the box representing the median value. The whiskers extend to the extreme values, excluding outliers, which are represented by individual dots. All reported information on median and standard deviation values is expressed in ng/mg. The cortisol content among the three groups was statistically analyzed using a completely randomized ANOVA, following a logarithmic transformation of the data to achieve normality. This was subsequently followed by orthogonal comparisons. For all statistical tests conducted, the level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Instrument conditions optimization

Optimization of the MS instrumental conditions was achieved by infusing a standard solution of cortisol and its deuterated analogue in acetonitrile, as described above. Although methods described in the literature often utilize both positive and negative ionization modes, we obtained higher intensity and superior signal symmetry using the [M+H]+ precursor ion for both cortisol (m/z 363.3) and cortisol-d4 (m/z 367.3). Consequently, the positive ionization mode was selected for our analysis. Following the optimization of the Declustering Potential (DP) and Entrance Potential (EP) parameters related to the aforementioned precursor ions, fragmentation analysis was performed to identify the most suitable product ions. Among the fragmented ions, those exhibiting the highest intensity and optimal peak shape were selected, alongside setting the source temperature and gas pressure parameters (curtain, 1 and 2). The chromatographic separation was performed using a gradient elution, with H2O containing 0.1 % HCOOH as mobile phase A and ACN containing 0.1 % HCOOH as mobile phase B, as detailed in paragraph “Equipment”. The gradient was specifically designed to ensure that cortisol and its deuterated analogue eluted approximately midway through the chromatographic run. This strategic elution time helps to prevent the signal from being affected by potential interferences that typically emerge during the initial minutes of the analysis.

Cortisol method validation

A complete validation was performed as described in paragraph “Cortisol validation procedure”. Given that cortisol is an endogenous compound, obtaining a cortisol-free hair matrix is a critical aspect for the validation of the analytical method. Therefore, the cortisol calibration curve was constructed using a pool of distal hair samples (from hair strands longer than 30 cm). This choice was based on the assumption that cortisol concentration is expected to be very low or absent in hair tips due to potential wash-out or damage effects. Initially, the collected distal hair samples were analyzed to confirm the absence of endogenous compounds, and an example chromatogram is provided in chromatogram A of Figure S1 (Supplementary Material S1). Moreover, a previous study by Binz et al. [23] suggests good linearity for both cortisol and (13)C3-labeled cortisol, as well as minor differences in the limit of quantification (LOQ) (cortisol: 1 pg/mg vs. (13)C3-cortisol 0.5 pg/mg). In accordance with the authors, we achieved a LOQ of 1.03 pg/mg. The calibration curves showed excellent linearity (R2>0.998) over the entire investigated range when using linear correlation (Table 2). Extracted ion chromatograms of the quantifier ions (cortisol: m/z 363.3>121.5 and cortisol-d4: m/z 367.3>121.2) for QCs at low, intermediate, and high concentration levels are presented in Figure S1 (Supplementary Material S1). The LOD and LOQ values were deemed adequate for the objectives of the present study and are detailed in Table 2. Inter-day precision (expressed as coefficient of variation) and accuracy (expressed as percentage error) were consistently below 15 % (Table 3). Repeatability was evaluated by measuring relative standard deviations (RSDs) at each concentration levels for n=7 curves and results are presented in Table 3. Sample stability tests were performed as previously described, and the cortisol concentration was found not to be significantly reduced. Specifically, samples analyzed after 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 7 days at room temperature, after 7 days at 4 °C, and after 7 days at −20 °C showed a mean variation from the nominal concentration of less than 15 % (Table 4). These data confirm that samples remained stable under the storage conditions employed. The matrix effect (%) ranged from −8.0 to +9.0 %, indicating a negligible impact of the hair matrix on the ionization process.

Calibration parameters.

| Compound | Mean R2 | Mean blank ± standard deviation (SD) | LOD | LOQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol, pg/mg | 0.999 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.30 | 1.03 |

Intra-day precision (CV %) and accuracy (BIAS %) for cortisol analysis.

| Cortisol |

Amount, pg/mg

|

Mean value ± SD

|

CV, %

|

BIAS, %

|

| 5 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 1.6 | 1.9 | |

| 10 | 11.9 ± 0.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 | |

| 20 | 25.5 ± 1.2 | 4.6 | 5.9 | |

| 50 | 56.9 ± 1.2 | 2.2 | 2.5 | |

| 100 | 115.5 ± 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | |

| 200 | 201.8 ± 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

Stability of QC samples after exposure to 20–25 °C, 4–8 °C, −20 °C.

| Compound | Amount range, pg/mg | Condition | Time | Mean deviation, % from day 0 | Min dev., % | Max dev., % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | 5–200 | 20–25 °C | 24 h | 3.7 | 0.7 | 10.6 |

| 48 h | 8.1 | 0.4 | 21.3 | |||

| 72 h | 8.4 | 2.0 | 21.3 | |||

| 7 days | 7.9 | 3.0 | 18.1 | |||

| 4–8 °C | 7 days | 8.9 | 5.5 | 14.5 | ||

| −20 °C | 7 days | 10.6 | 6.4 | 24.4 |

Analysis of authentic hair samples

A total of 240 hair segments from 87 individuals were analyzed. Demographic data of the cohort, including sex distribution and age, are reported in Table 6. When possible, hair was divided into three segments corresponding to Pre-L, lL, and Post-L periods. In cases of insufficient length, only L and Post-L segments were available. Cortisol was reliably quantified above the LOQ in 62 subjects (71 %), while 25 samples were below LOQ (Table 6). Median cortisol concentrations were 2.28 pg/mg in Pre-L, 3.06 pg/mg in L, and 3.68 pg/mg in Post-L segments (Table 5). ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences between Post-L and both Pre-L and L (Figure 2, left). Pairwise comparisons confirmed that individual cortisol concentrations were significantly higher in Post-L compared to both Pre-L and L segments (Figure 2, right). In 45 individuals with complete three-segment profiles (Pre-L, L and Post-L), 76 % exhibited higher cortisol in Post-L than in Pre-L.

The mean, median and range of cortisol concentration in pre-lockdown, lockdown and post-lockdown hair segments.

| Cortisol, pg/mg | Mean | Median | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-lockdown | 3.78 | 2.28 | 1.03 | 22.73 |

| Lockdown | 5.09 | 3.06 | 1.05 | 26.36 |

| Post-lockdown | 4.99 | 3.68 | 1.13 | 22.37 |

Demographic data of the cohort, mean median and cortisol concentration range (>LOQ).

| Cortisol value | n | Male/Female | Mean age ± SD | Cortisol concentration, pg/mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >LOQ | 62 | 35/27 | 36 ± 14 |

Mean 4.78

Median 2.96 Range 1.03–26.36 |

| <LOQ | 25 | 7/18 | 34 ± 16 | – |

-

LOQ, Limit of Quantitation.

Box-and-whisker plots of cortisol concentrations: Left, distribution across pre-lockdown (Pre-L), lockdown (L), and post-lockdown (Post-L) segments; right, within-individual differences across the three periods (ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test).

Subgroup analyses revealed pronounced differences by sex and age, as reported in Table 7. During lockdown, cortisol increased in 93 % of females compared to 50 % of males. In the 17–24-year age group, 89 % showed an increase, confirming young adults as the most affected subgroup. Post-L, cortisol remained elevated in most females (71 %), while males were more evenly distributed between increases and decreases. Age-related analysis indicated that although increases were most marked in younger adults, elevated cortisol was observed across all age groups.

Gender and age prevalence of cortisol increase (expressed as percentage).

| Prevalence of cortisol increase, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-lockdown vs. lockdown | Lockdown vs. post-lockdown | Pre-lockdown vs. post-lockdown | |

| Male/Female | 50/93 | 47/71 | 53/93 |

| 17−24 y 25−40 y 41−67 y |

89

63 79 |

71

52 50 |

88

77 71 |

Additional testing of hair samples for chronic alcohol and cannabis use (ethylglucuronide and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, EtG and THC) [24], 25] yielded few positives (9 for EtG, 11 for THC). Among positives, EtG concentrations increased in 75 % (Pre-L vs. L) and 67 % (L vs. Post-L), while THC decreased in 86 and 82 % of cases across the same comparisons. Due to the low number of positives, no correlations with cortisol were performed.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on chronic stress by measuring hair cortisol concentrations. Using a validated LC-MS/MS method, we observed significant differences in cortisol levels across pandemic phases, with the highest concentrations in the post-lockdown period.

The increase in cortisol during lockdown supports previous evidence that social isolation and restrictive measures were strong psychological stressors. Importantly, cortisol did not decline after restrictions were lifted. However, the majority of individuals exhibited persistently elevated levels in the post-lockdown period, indicating that the psychological burden of the pandemic extended beyond the immediate crisis. This is consistent with ongoing stressors such as economic uncertainty, unemployment, family management difficulties, and lingering fear of infection.

Sex- and age-related analyses confirmed that females and younger individuals were more vulnerable, showing the largest increases in cortisol. Adolescents and young adults likely experienced heightened stress due to developmental vulnerabilities, educational disruption, and reduced social interaction. Nevertheless, increases were observed across all age groups, highlighting the broad and lasting psychological impact of the pandemic on the population. The detection of elevated EtG in most positive samples across time windows may suggest increased alcohol consumption as a coping strategy, while decreasing THC concentrations could reflect reduced availability or changes in consumption habits during L. However, given the small number of positives, these observations remain exploratory.

From a methodological perspective, the combination of segmental hair analysis and a fully validated LC-MS/MS protocol proved robust, enabling retrospective and time-resolved stress assessment from a single non-invasive sample. This strengthens the applicability of hair cortisol as a biomarker in population-level studies investigating long-term psychosocial stressors.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, cortisone, an important metabolite of cortisol and frequently included in hair steroid analyses, was not measured. Future studies should consider both cortisol and cortisone to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity. Second, no additional covariates such as employment status, psychological disorders, or self-reported stress measures were collected, limiting the ability to directly associate cortisol variations with specific psychosocial factors. Third, distal hair segments may be affected by partial wash-out of endogenous cortisol, which could lead to underestimation of concentrations in older time windows [26], [27], [28], [29]. Fourth, the number of subjects positive for EtG or THC was too small to allow meaningful correlation analyses with cortisol levels. Finally, although our method was fully validated and robust, the exploratory nature of this cohort study calls for replication in larger, independent populations.

Strength

A key strength of this study lies in the combination of segmental hair analysis with a fully validated LC-MS/MS method for cortisol quantification. This approach enables a non-invasive, retrospective, and time-resolved assessment of chronic stress from a single biological sample. By analyzing hair segments corresponding to different pandemic phases, the method provides a unique temporal profile of stress exposure, offering high analytical sensitivity and specificity. This makes it particularly valuable for both clinical and population-level studies investigating the long-term psychological impact of external stressors such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

In the present study, we assessed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on cortisol trends, utilizing hair analysis as a marker of stress in a cohort of 87 subjects. A novel extraction and instrumental LC-MS/MS procedure for cortisol identification and quantification in hair was successfully established and fully validated, demonstrating a robust LOQ of 1.03 pg/mg. Our findings revealed that the cortisol content differed significantly in the post-L group compared to both the pre-L and L groups. Specifically, female and young individuals aged 17 and 24 years exhibited the most pronounced increases in cortisol levels. This method also facilitated the determination of cortisol in hair sample through a simple extraction approach. Overall, the data highlight a sustained elevation in stress markers, particularly in vulnerable groups, persisting well into the post-L period, underscoring the long-term psychological repercussions of the pandemic.

Funding source: Italian Ministry of Health - Current Research 25 (RC25) - Fondazione IRCSS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors’ responsibilities were as follows: SC and MM conceptualization and methodology; SC, MM, EP, BS, IA, AR, RFB validation and formal analysis; SC, EP, RFB and MO writing – original draft; SC, MM, IA, AR, RFB, MO funding acquisition; SC and MO supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study was partially funded by Italian Ministry of Heath - Current research (RC25) Fondazione IRCSS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Rajkumar, RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;52:102066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Moccia, L, Janiri, D, Pepe, M, Dattoli, L, Molinaro, M, De Martin, V, et al.. Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:75–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.048.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Wang, C, Pan, R, Wan, X, Tan, Y, Xu, L, Ho, CS, et al.. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2020;17:1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Brooks, SK, Webster, RK, Smith, LE, Woodland, L, Wessely, S, Greenberg, N, et al.. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020;395:912–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Czeisler, MÉ, Lane, RI, Petrosky, E, Wiley, JF, Christensen, A, Njai, R, et al.. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic – United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1049–57. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Galea, S, Merchant, RM, Lurie, N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:817. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Roberts, A, Rogers, J, Mason, R, Siriwardena, AN, Hogue, T, Whitley, GA, et al.. Alcohol and other substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;229:109150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109150.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Russell, E, Koren, G, Rieder, M, Van Uum, S. Hair cortisol as a biological marker of chronic stress: current status, future directions and unanswered questions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012;37:589–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Stalder, T, Kirschbaum, C. Analysis of cortisol in hair – state of the art and future directions. Brain Behav Immun 2012;26:1019–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Stalder, T, Steudte-Schmiedgen, S, Alexander, N, Klucken, T, Vater, A, Wichmann, S, et al.. Stress-related and basic determinants of hair cortisol in humans: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017;77:261–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.12.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Rajcani, J, Vytykacova, S, Solarikova, P, Brezina, I. Stress and hair cortisol concentrations in nurses during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021;129:105245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105245.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Rajcani, J, Vytykacova, S, Solarikova, P, Brezina, I. A follow-up to the study: stress and hair cortisol concentrations in nurses during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021;133:105434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105434.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Stalder, T, Tietze, A, Steudte, S, Alexander, N, Dettenborn, L, Kirschbaum, C. Elevated hair cortisol levels in chronically stressed dementia caregivers. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014;47:26–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.04.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Penz, M, Stalder, T, Miller, R, Ludwig, VM, Kanthak, MK, Kirschbaum, C. Hair cortisol as a biological marker for burnout symptomatology. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018;87:218–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.07.485.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Kassis, W, Aksoy, D, Favre, CA, Arnold, J, Gaugler, S, Grafinger, KE, et al.. On the complex relationship between resilience and hair cortisol levels in adolescence despite parental physical abuse: a fourth wave of resilience research. Front Psychiatr 2024;15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1345844.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Hakeem, MK, Sallabi, S, Ahmed, R, Hamdan, H, Mameri, A, Alkaabi, M, et al.. A dual biomarker approach to stress: hair and salivary cortisol measurement in students via LC-MS/MS. Anal Sci Adv 2025;6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ansa.70003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Martins-Silva, T, Martins, RC, Murray, J, Carvalho, AM, Rickes, LN, Corrêa, BDF, et al.. Hair cortisol measurement: a systematic review of current practices and a proposed checklist for reporting standards. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2025;171:107185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2024.107185.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Quinete, N, Bertram, J, Reska, M, Lang, J, Kraus, T. Highly selective and automated online SPE LC–MS 3 method for determination of cortisol and cortisone in human hair as biomarker for stress related diseases. Talanta 2015;134:310–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2014.11.034.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Mirzaian, M, van Zundert, SKM, Schilleman, WF, Mohseni, M, Kuckuck, S, van Rossum, EFC, et al.. Determination of cortisone and cortisol in human scalp hair using an improved LC-MS/MS-based method. Clin Chem Lab Med 2024;62:118–27. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0341.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. van Harskamp, D, Ackermans, MT, Wickenhagen, WV, Heijboer, AC, van Goudoever, JB. Enzymatic digestion of hair increases extraction yields of cortisol: a novel two-dimensional liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for hair cortisol analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem 2025;417:3465–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-025-05878-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Ibar, C, Fortuna, F, Gonzalez, D, Jamardo, J, Jacobsen, D, Pugliese, L, et al.. Evaluation of stress, burnout and hair cortisol levels in health workers at a university hospital during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021;128:105213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105213.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Bioanalytical method validation: Guidance for industry. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

23. Binz, TM, Braun, U, Baumgartner, MR, Kraemer, T. Development of an LC–MS/MS method for the determination of endogenous cortisol in hair using 13 C 3-labeled cortisol as surrogate analyte. J Chromatogr B 2016;1033–1034:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2016.07.041.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Casati, S, Ravelli, A, Angeli, I, Bergamaschi, RF, Binelli, G, Minoli, M, et al.. PTCA (1-H-Pyrrole-2,3,5-Tricarboxylic acid) as a marker for oxidative hair treatment: distribution, gender aspects, correlation with EtG and self-reports. J Anal Toxicol 2021;45:513–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkaa153.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Angeli, I, Casati, S, Ravelli, A, Minoli, M, Orioli, M. A novel single-step GC–MS/MS method for cannabinoids and 11-OH-THC metabolite analysis in hair. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2018;155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2018.03.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Hamel, AF, Meyer, JS, Henchey, E, Dettmer, AM, Suomi, SJ, Novak, MA. Effects of shampoo and water washing on hair cortisol concentrations. Clin Chim Acta 2011;412:382–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2010.10.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Kristensen, SK, Larsen, SC, Olsen, NJ, Fahrenkrug, J, Heitmann, BL. Hair dyeing, hair washing and hair cortisol concentrations among women from the healthy start study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017;77:182–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.12.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Hoffman, MC, Karban, LV, Benitez, P, Goodteacher, A, Laudenslager, ML. Chemical processing and shampooing impact cortisol measured in human hair. Clin Invest Med 2014;37:E252–7. https://doi.org/10.25011/cim.v37i4.21731.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Igboanugo, S, O’Connor, C, Zitoun, OA, Ramezan, R, Mielke, JG. A systematic review of hair cortisol in healthy adults measured using immunoassays: methodological considerations and proposed reference values for research. Psychophysiology 2024;61. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.14474.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/labmed-2025-0112).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.