Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to describe the pathogen spectrum of bacteria and viruses of RTIs in hospitalized children during the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic in Shenzhen.

Methods

From October 2020 to October 2021, the results of pathogenic tests causing RTIs were retrospectively analyzed in hospitalized children in Shenzhen Luohu Hospital Group.

Results

829 sputum samples for bacterial isolation and 1,037 nasopharyngeal swabs for virus detection in total. The positive detection rate (PDR) of bacteria was 42.1%. Staphylococcus aureus (18.8%) was the predominant bacteria detected in positive cases, with Moraxella catarrhalis (10.9%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (9.5%) following. The PDR of the virus was 65.6%. The viruses ranking first to third were Human Rhinovirus (HRV), Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and Human Parainfluenza (HPIV), with rates of 28.0, 18.1, and 13.5%, respectively. Children under 3 years were the most susceptible population to RTIs. The pathogens of S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, HRV, and HPIV were more prevalent in autumn. Meanwhile, RSV had a high rate of infection in summer and autumn. S. aureus and HRV had higher co-infection rates.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate the pathogen spectrum of 1,046 hospitalized children with RTIs in Shenzhen, China, during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Introduction

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) in humans can evolve from common colds to severe pneumonia, representing a pressing public health challenge and a major global health burden in developing countries and especially among children in socio-economic disadvantaged situations [1]. The 2019 Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) study showed that pneumonia and bronchiolitis caused by respiratory pathogens affected 489 million people globally and children under 5 years were the populations mainly affected by pneumonia [2]. In China, S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, S. aureus, RSV, and HRV were the most commonly reported respiratory pathogens in the epidemiological survey of children RTIs in the recent five years [3, 4]. S. pneumoniae mainly caused otitis media, pneumonia, septicemia, and meningitis. It was one of the key contributors to child mortality [5]. More than 90% of invasive H. influenzae infections occurred in children under 5 years of age (4). S. aureus had become a common reason for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in children, and rising rate of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) had increased the burden of treatment for the disease. One study showed that 81% of S. aureus -induced CAP patients required intensive care, with a mortality rate of 29% [6]. RSV was found to be the predominant viral-causing LRTIs in childhood, accounting for 65% of hospitalized cases [7]. HRV was the second leading cause of RTIs after RSV, causing major diseases including bronchitis, asthma, and pneumonia. HRV infection in children was seasonal and susceptible, with mild or asymptomatic clinical symptoms, so it was easy to be ignored [8].

At the end of 2019, COVID-19 was caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). So far, it has posed an enormous health burden worldwide. To curb transmission, population-level non-pharmaceutical interventions have been rolled out on a large scale, including wearing masks in public, stay-at-home orders, and encouragement of social distancing. Studies from France, Japan and Mexico showed that these measures could also curb the spread of influenza at the same time compared to previous seasons before COVID-19 [9], [10], [11]. However, little research has been done on the prevalence of other respiratory pathogens, including bacteria, during epidemics.

Hospitalized children with RTIs tended to be more severe, and the majority of these patients had secondary bacterial infections with viral respiratory infections. This study analyzed the pathogen spectrum of infected pathogens containing bacteria and viruses among hospitalized children in Shenzhen, China, during the COVID-19 outbreak. This survey will help parents and pediatricians to develop new therapies or preventive measures and improve interventional approaches that may modify respiratory health outcomes in advance.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients with RTIs between October 2020 to October 2021 admitted to the pediatric wards were enrolled in Shenzhen Luohu Hospital Group. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) children aged younger than 12 years; (2) at least one of respiratory symptoms (sore throat, cough, body temperature above 37.5 °C, and dyspnea). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Shenzhen Luohu People’s Hospital (2021-LHQRMYY-KYLL-070).

Specimens and pathogen detection

Sputum specimens or nasopharyngeal swabs were obtained from all the enrolled children within 48 h of admission by trained personnel following standard operating procedures. The specimens were immediately transferred to the Medical Laboratory of Luohu Hospital Group for respiratory pathogen detection.

Sputum specimens were smeared on glass slides and then observed under a microscope. Squamous epithelial cells <10/low magnification field and leukocytes >25/low magnification field were considered satisfactory. Unqualified specimens were re-collected or discarded. The sputum specimens were inoculated on Columbia blood plates, MacConkey plates, and chocolate plates (BIOIVD biotechnology, Zhengzhou, China), 35 °C with 5–8% CO2 for 18–24 h. The bacteria were identified according to the characteristics of colonies on the medium, gram staining, microscopic observation and confirmed by the matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany).

Viral RNAs from Nasopharyngeal swabs were extracted and purified. There were 13 respiratory viruses including Adenoviridae (ADV), Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Influenza A virus (FluA), Influenza B virus (FluB), Influenza A virus H1N1, Influenza A virus H3N2, Human Parainfluenza (HPIV), Human Rhinovirus (HRV), Human Coronavirus (HCoV), Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV), Human Bocavirus (HBoV), Chlamydia pneumoniae (CP) and Mycoplasma (MP) identified in one tube. A preliminary detection of 13 pathogens above was carried out by real-time RT-PCR using primers and probes from the commercial “Multiple detection of 13 respiratory pathogens” kit (Health Gene Technologies, Ningbo, China) according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). Counting data was described by the number of cases and percentage. The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used for comparison of categorical data. All tests were two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The demographic data are shown in Tables 1 and 2. From October 2020 to October 2021, 1,046 eligible specimens were obtained from children hospitalized with RTIs. The patient’s age ranged from 0 to 12 years. 829 sputum samples were tested for bacterial detection. The ratio of male patients to female patients was 1.55 to 1 (504/325). 176 patients were under one year of age, 415 patients were 1–3 years of age, and 238 patients were 3–12 years of age. 1,037 nasopharyngeal swabs were tested for virus. the ratio of male patients to female patients tested for virus was 1.52 to 1 (625/412). 200 patients were under one year of age, 518 patients were 1–3 years of age, and 319 patients were 3–12 years of age.

The distribution of common respiratory bacteria in 829 children with RTIs.

| Characteristics | Total | Positive | Negative | S. aureus | M. catarrhalis | S. pneumoniae | H. influenzae | K. pneumoniae | A. baumannii | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 829 | 349 (42.1) | 480 (57.9) | 156 (18.8) | 90 (10.9) | 79 (9.5) | 36 (4.3) | 13 (1.6) | 10 (1.2) | 42 (5.1) |

|

|

||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Male | 504 | 215 (42.7) | 289 (57.3) | 103 (20.4) | 51 (10.1) | 39 (7.7) | 24 (4.8) | 5 (1.0) | 7 (1.4) | 29 (5.6) |

| Female | 325 | 134 (41.2) | 191 (58.8) | 53 (16.3) | 39 (12) | 40 (12.3) | 12 (3.7) | 8 (2.5) | 3 (0.9) | 13 (4.0) |

|

|

||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| <1 years | 176 | 97 (55.1) | 79 (44.9) | 52 (29.5) | 21 (11.9) | 20 (11.4) | 7 (4.0) | 5 (2.8) | 3 (1.7) | 14 (8.0) |

| 1–3 years | 415 | 183 (44.1) | 232 (55.9) | 76 (18.3) | 54 (13.0) | 48 (11.6) | 16 (3.9) | 6 (1.4) | 6 (1.4) | 18 (4.3) |

| 3–12 years | 238 | 69 (29.0) | 169 (71.0) | 28 (11.8) | 15 (6.3) | 11 (4.6) | 13 (5.5) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 10 (4.2) |

|

|

||||||||||

| Infection types | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| URTI | 163 | 33 (20.2) | 130 (79.8) | 18 (11.0) | 8 (5.0) | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 7 (4.3) |

| LRTI | 666 | 316 (47.4) | 350 (52.6) | 138 (20.7) | 82 (12.3) | 76 (11.4) | 33 (5.0) | 13 (2.0) | 9 (1.4) | 35 (5.3) |

-

Data are presented as no. (%) of each group. Percentages summed to over 100% because some patients had more than one diagnosis. URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection.

The distribution of common respiratory viruses in 1,037 children with RTIs.

| Characteristics | Total | Positive | Negative | HRV | RSV | HPIV | HMPV | HCoV | ADV | HBoV | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,037 | 680 (65.6) | 357 (34.4) | 290 (28.0) | 188 (18.1) | 140 (13.5) | 60 (5.8) | 12 (1.6) | 25 (2.4) | 16 (1.5) | 17 (1.6) |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| Male | 625 | 417 (66.7) | 208 (33.3) | 187 (29.9) | 114 (18.2) | 82 (13.1) | 34 (5.4) | 8 (1.3) | 13 (2.1) | 11 (1.8) | 13 (2.1) |

| Female | 412 | 263 (63.8) | 149 (36.2) | 103 (25.0) | 74 (18.0) | 58 (14.1) | 26 (6.3) | 4 (1.0) | 12 (2.9) | 5 (1.2) | 4 (1.0) |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Age | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| <1 years | 200 | 135 (67.5) | 65 (32.5) | 47 (23.5) | 52 (26.0) | 33 (16.5) | 4 (2.0) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (3.0) |

| 1–3 years | 518 | 364 (70.3) | 154 (29.7) | 143 (27.6) | 120 (23.2) | 71 (13.7) | 26 (5.0) | 8 (1.5) | 16 (3.1) | 13 (2.5) | 6 (1.2) |

| 3–12 years | 319 | 181 (56.7) | 138 (43.3) | 100 (31.3) | 16 (5.0) | 36 (11.3) | 30 (9.4) | 1 (0.3) | 5 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.6) |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Infection types | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| URTI | 252 | 119 (47.2) | 133 (52.8) | 82 (32.5) | 2 (0.8) | 18 (7.1) | 2 (0.8) | 9 (3.6) | 7 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.0) |

| LRTI | 785 | 561 (71.5) | 224 (28.5) | 208 (26.5) | 186 (23.7) | 122 (15.5) | 58 (7.4) | 3 (0.4) | 18 (2.3) | 16 (2.0) | 12 (1.5) |

-

Data are presented as no. (%) of each group. Percentages summed to over 100% because some patients had more than one diagnosis.

General characteristics of bacterial distribution

The overall PDR of respiratory bacterial infection was 42.1% (349/829 samples). The PDR of respiratory bacterial infection in female patients (41.2%) was lower than that in male patients (42.7%), but this difference was not statistically significant (χ2 =0.165, p>0.05). S. aureus, Moraxella catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae were most likely to infect the respiratory tract of children, with detection rates of 18.8, 10.9, 9.5 and 4.3%, respectively. The incidence of respiratory bacterial infection in patients under one year of age was 55.1%, which was higher than the incidence in patients of 1–3 years of age (44.1%) and patients of 3–12 years of age (29.0%). Statistical differences existed in the incidence of the bacteria among the three age groups (χ2=29.684, p<0.05). Patients under one year of age had the highest prevalence of S. aureus compared with the other age groups (29.5 vs. 18.3% vs. 11.8%). For M. catarrhalis and S. pneumoniae, the highest incidence (13 and 11.6%, respectively) appeared in the age group of 1–3 years. There were statistically significant differences in the prevalence of S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, and S. pneumoniae by age group (χ2=21.078, 7.303 and 9.332 respectively, p<0.05). Common respiratory bacteria in our study were more likely to cause LRTIs (χ2=45.295, p<0.05). The PDR of S. aureus was highest both in URTIs (11.0%) and LRTIs (20.7%). There was a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of S. aureus in different infection groups (χ2=6.916, p<0.05) (Table 1). According to the above analysis, hospitalized children with RTIs were susceptible to S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae and these bacteria were more likely to cause LRTIs in children under 3 years old.

General characteristics of virus distribution

A total of 680 RTIs cases were infected by at least one of the 13 common respiratory viruses with a viral incidence of 65.6% (680/1,037 samples). The incidence of respiratory virus infection in female patients (63.8%) was lower than that in male patients (66.7%), however, this difference was not statistically significant (χ2=0.916, p>0.05). Children of 1–3 years of age were more susceptible to the virus than children under one year of age and over 3 years (70.3 vs. 67.5% vs. 56.7%). Statistical differences existed in the incidence of the virus among different age groups (χ2=16.418, p<0.05). Viruses ranking first to fourth in PDR were HRV, RSV, HPIV and HMPV with detection rates of 28.0, 18.1, 13.5 and 5.8%, respectively. Patients under one year of age were more prone to be infected by RSV (26.0%) and HPIV (16.5%) compared with those older. There was a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of RSV by age group (χ2=54.161, p<0.05). However, for HPIV, the difference was not statistically significant (χ2=2.900, p>0.05). For HRV and HMPV, the highest incidence (31.3 and 9.4%, respectively) appeared in the age group of 3–12 years. The difference in the prevalence of HRV was not statistically significant (χ2=3.825, p>0.05) by age group. For HMPV, the difference was statistically significant (χ2=13.479, p<0.05). HCoV and FLuB were more likely to cause URTIs. HRV had the highest PDR in both URTIs (32.5%) and LRTIs (26.5%), and the difference in both infection groups was statistically significant (χ2=6.926, p<0.05) (Table 2). Thus, Respiratory viruses with high prevalence included HRV, RSV, HPIV, and HMPV. With the exception of HCoV and FLuB, most respiratory viruses were more likely to cause LRTIs in children under 3 years of age.

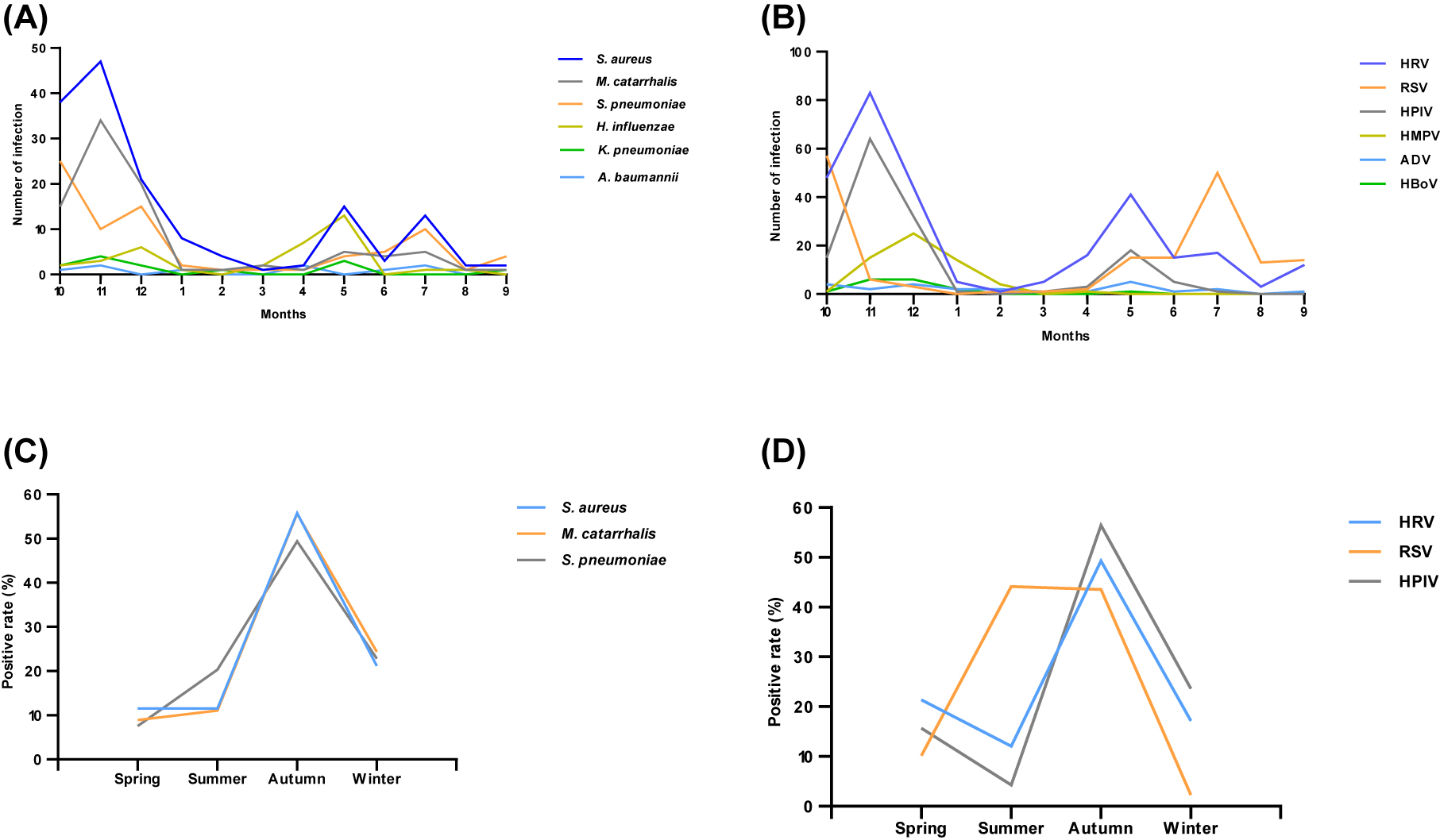

Monthly and seasonal distribution of pathogens

There was a significant difference that existed in the overall incidence of viruses in four seasons (χ2=16.818, p<0.05). However, the difference in the incidence of bacteria in four seasons was not obvious (χ2=0.758, p>0.05). HRV, RSV, HPIV, S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, and S. pneumoniae were the main epidemic pathogens all year round. HRV and HPIV were mainly -circulated in autumn with a peak in November (28.6 and 45.7% respectively). RSV was prevalent in summer and autumn with two peaks In July and October (28.2 and 32.2% respectively). S. aureus and M. catarrhalis circulated mainly in autumn with a peak in November (30.1 and 37.8% respectively). S. pneumoniae mainly circulated in autumn with a peak in October (31.6%) (Figure 1). From the above analysis, Autumn, especially in November, was the season with a high incidence of HRV, HPIV, S. aureus, and M. catarrhalis. More attention should be paid to RSV infections during the summer.

Monthly and seasonal distribution of respiratory pathogens from October 2020 to October 2021 (A) monthly distribution of bacteria (B) monthly distribution of virus (C) seasonal distribution of mainly infected bacteria (D) seasonal distribution of mainly infected viruses.

Co- infection types of respiratory pathogens

Pathogens with high detection rates were also susceptible to co-infection. Bacterial-bacterial co-infections accounted for 73 cases, an incidence of 8.8% (73/829). Of the types of bacterial-bacterial co-infections, S. aureus co-infections accounted for 65.8%. Of the S. aureus co-infection, S. aureus + M. catarrhalis (46%) was the most frequent; followed by S. aureus + S. pneumoniae (19%) (Figure 2A). A total of 67 specimens were detected as viral-viral co-infection with an incidence of 6.5% (67/1,037). The types of viral-viral co-infections were complex. Among them, HRV-coinfections accounted for 91%. Of the HRV co-infection, the HRV + HPIV coinfection (43%) was the most frequent; followed by HRV + RSV (21%) and HRV + HMPV (10%) (Figure 2B). Of the 1,046 eligible specimens, 822 patients underwent tests for bacteria and viruses. Among them, bacterial-virus co-infection accounted for 249 cases with an incidence of 30.3% (249/822). Of these co-infections, double infection was most commonly caused by S. aureus + RSV (10.0%, 25/249). S. aureus + HRV and S. pneumoniae + RSV were followed, with 22 samples of both. The PDR of triple infection was relatively low and mainly caused by M. catarrhalis + S. aureus + HRV (2.8%, 7/249) (Table 3). Thus, pathogens with a high detection rate of single pathogen infection also had a high co-infection rate. More attention should be paid to S. aureus and HRV in cases of -co-infection.

Co-infection of common pathogens (A) distribution of S. aureus co-infection (B) distribution of HRV co-infection.

The bacteria-virus co-infections in respiratory infection cases.

| Bacteria/virus co-infections | Number of cases | Constituent ratio, % |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus + RSV | 25 | 10.0 |

| S. aureus + HRV | 22 | 8.8 |

| S. pneumoniae + RSV | 22 | 8.8 |

| M. catarrhalis + HPIV | 14 | 5.6 |

| S. aureus + HPIV | 9 | 3.6 |

| S. aureus + HMPV | 8 | 3.2 |

| M. catarrhalis + HRV | 7 | 2.8 |

| S. pneumoniae + HRV | 7 | 2.8 |

| S. pneumoniae + HPIV | 6 | 2.4 |

| M. catarrhalis + RSV | 6 | 2.4 |

| M. catarrhalis + S. aureus + HRV | 7 | 2.8 |

| M. catarrhalis + S. aureus + HPIV | 5 | 2.0 |

| M. catarrhalis + S. aureus + RSV | 5 | 2.0 |

| Others | 106 | 42.6 |

| Total | 249 | 100.0 |

Discussion

This study was to investigate the pathogen spectrum of respiratory pathogens, including bacteria and viruses, in hospitalized children with RTIs in Shenzhen, China, after the COVID-19 outbreak.

In our study, children aged 1–3 years had the highest respiratory infection rate. One possible reason was that pandemic containment measures such as school closures, home quarantines and reduced social interaction have largely reduced outdoor activities for older children (1–12 years). However, children aged 1–3 years had poor adherence to preventive measures such as mask use hand washing, and gel alcohol use before and after contact with others, which also made children in this age group more susceptible to respiratory pathogens.

The prognosis of patients with COVID-19 depends on the severity of the LRTIs caused by SARS-CoV-2 [12]. Timely understanding of the epidemic trend of respiratory bacterial infection is beneficial to the prevention and treatment of LRTIs in communities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae were the major pathogens responsible for respiratory tract infections in children. The detection rates of S. aureus and M. catarrhalis showed an increasing trend year by year [13]. In addition, Zhu et al. (14). reported a significant increase in respiratory M. catarrhalis infection among children in Chengdu, China, in 2020 compared with 2019. In our study, a total of 42.1% of the RTIs cases were detected as bacteria-positive. S. aureus was the most frequently detected bacterium in Shenzhen in 2020–2021, followed by M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae and others. Common bacteria during the pandemic may be associated with bacterial structure changes [14]. In addition, studies have found that family members and the home environment play a key role in the transmission of S. aureus. Therefore, increased time spent in the home quarantine may help stabilize the incidence of S. aureus infection during the COVID-19 epidemic [15, 16].

A total of 65.6% of RTIs cases were tested positive for the virus. HRV has been known to be the major virus for RTIs in children, with a PDR as high as 10–30% in many studies [17, 18]. Our study showed that HRV was the most frequently detected virus in Shenzhen during the 2020–2021 period, with a PDR of 28%. RSV was the second common virus in our study, followed by HPIV and HMPV. These viruses were the common causes of LRTIs, mainly occurred in children under 3 years, and the prevalence of these viruses decreased with age. Studies in Austria and Japan had also reported a high incidence of HRV infections during the COVID-19 epidemic [19, 20]. HRV is a non-enveloped virus that resists disinfectants containing ethanol and can survive in the environment for long periods of time. HRV can also be transmitted between family members [21, 22]. These factors may lead to HRV infection being less affected by epidemic prevention policies. A significant increase in the rate of RSV infection was reported during the winter of 2020 in Australia (19). Studies had also shown that higher rates of RSV infection have not been detected during COVID-19 [23, 24]. However, the mechanism behind these findings is unclear. Xu [23] et al. found that the detection rates of HPIV and HMPV increased significantly in the winter of 2020, and the infection rate of HPIV was even higher than that in the same period of 2019. A study in Shenzhen also reported higher rates of HPIV and HMPV detection in the winter of 2020 [25]. One study suggested that interference between influenza viruses and other respiratory viruses could affect host viral infection, especially the reduction of influenza virus infection due to epidemic prevention measures, which partly explains the higher detection rates of HPIV and HMPV [26]. Both influenza and COVID-19 are spread between humans through contact and droplets [27]. Therefore, non-pharmaceutical interventions related to reducing COVID-19 transmission would also significantly reduce influenza infection rates. Competition for resources between viruses, immune responses or interference with viral proteins may also play some role [28], [29], [30]. Therefore, the results of these studies suggest that after the COVID-19 outbreak, attention should be focused on HRV, RSV, HPIV and HMPV infections in children, especially those under 3 years of age.

Seasonal climate is a significant factor affecting pathogen transmission. Our study found regular seasonality for S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, HRV, RSV, and HPIV. The detection rates of S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, and S. pneumoniae were highest in autumn and peaked in November. However, reports from Beijing and Shanghai found that respiratory bacterial infections were more likely to occur in winter [31, 32]. The detection rates of RHV, HRV, and HPIV were highest in autumn in our study. A study from India [17] found RHV, and HRV was more prevalent in the summer, followed by the rainy season, which was not consistent with our results. These differences in seasonal detection may be related to local climate and demographic factors. Wang [33] found the detection rate of HPIV was highest in autumn in Shenzhen, which was consistent with our results. The detection rate of RSV was highest in summer and autumn, peaking in July and October. Cold and humidity are risk factors for RSV infection. Shenzhen is located in southern China; It has a typically subtropical monsoon climate, where RSV infection increases primarily during the wet months. A report from Vietnam found that RSV was prevalent in the summer [34], which was similar to our results.

Co-infection is common in RTIs. In our study, S. aureus, HRV, and RSV were the most frequently detected co-infection pathogens. The classical view is that viruses pave the way for bacterial infection by promoting bacterial adhesion to respiratory epithelial cells [35]. Of the co-infections, S. aureus + M. catarrhalis, HRV + HPIV, S. aureus + RSV, and S. aureus + HRV combinations were the most common, which was consistent with the high PDR of these pathogens. Thus, the pathogen with a high PDR in a single infection will also have a high PDR in a co-infection.

Since our study is a retrospective study rather than a prospective analysis, it has the following limitations. (1) Not all 1,046 enrolled patients were tested for both bacteria and viruses, which may lead to an underestimation of some pathogens’ burden. (2) The surveillance time was not enough. COVID-19 is still difficult to be eradicated now, and epidemiological analysis of respiratory pathogens will be needed over the next few years to validate our results and implement effective preventive measures against RTIs in children.

Conclusions

Non-pharmaceutical interventions such as vaccination, home quarantine, reduced social interaction, hand hygiene and environmental disinfection can help address the spread of COVID-19 while also reducing the spread of seasonal epidemic-related pathogens. This information is important for planning strategies to prevent future epidemics of respiratory-related pathogens. In our study, S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, HRV, RSV, and HPIV were the main pathogens of RTIs in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. Positive rates of S. aureus and HRV in RTIs are highest in children, who were prone to co-infection. Children under 3 years were susceptible to respiratory bacteria and viruses. Autumn was the season of high incidence of RTIs. The results of this study can guide the prevention and control decisions for RTIs in children during the epidemic. We will continue to statistically analyze the epidemiological characteristics of respiratory pathogens in hospitalized children with RTIs during the COVID-19 pandemic to obtain a clearer pathogen spectrum.

Funding source: Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline

Award Identifier / Grant number: SZXK054

Funding source: Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen

Award Identifier / Grant number: SZSM201601062

Acknowledgments

We thank the children participating in this study and their families; the nurses and anyone who contributed to this study.

-

Research funding: The present study was supported by Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (Grant No. SZSM201601062) and Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline (Grant No. SZXK054).

-

Author contributions: Xiuming Zhang designed research. Xinyuan Han and Xiaojuan Gao analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Xueling Wang, Jin Zhang and Xuelei Gong analyzed the data. Lijuan Kan and Jiehong Wei contributed to revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shenzhen Luohu District People’s Hospital (2021-LHQRMYY-KYLL-070).

References

1. Zeng, ZQ, Chen, DH, Tan, WP, Qiu, SY, Xu, D, Liang, HX, et al.. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of human coronaviruses OC43, 229E, NL63, and HKU1: a study of hospitalized children with acute respiratory tract infection in Guangzhou, China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;37:363–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-017-3144-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Torres, A, Cilloniz, C, Niederman, MS, Menéndez, R, Chalmers, JD, Wunderink, RG, et al.. Pneumonia. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2021;7:25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00259-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. DeAntonio, R, Yarzabal, JP, Cruz, JP, Schmidt, JE, Kleijnen, J. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia and implications for vaccination of children living in developing and newly industrialized countries: a systematic literature review. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2016;12:2422–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2016.1174356.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Ning, G, Wang, X, Wu, D, Yin, Z, Li, Y, Wang, H, et al.. The etiology of community-acquired pneumonia among children under 5years of age in mainland China, 2001–2015: a systematic review. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2017;13:2742–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2017.1371381.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Yu, YY, Xie, XH, Ren, L, Deng, Y, Gao, Y, Zhang, Y, et al.. Epidemiological characteristics of nasopharyngeal Streptococcus pneumoniae strains among children with pneumonia in Chongqing, China. Sci Rep 2019;9:3324. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40088-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Hageman, JC, Uyeki, TM, Francis, JS, Jernigan, DB, Wheeler, JG, Bridges, CB, et al.. Severe community-acquired pneumonia due to Staphylococcus aureus, 2003-04 influenza season. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:894–9. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1206.051141.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Weber, MW, Mulholland, EK, Greenwood, BM. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in tropical and developing countries. Trop Med Int Health 1998;3:268–80. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00213.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Biagi, C, Rocca, A, Poletti, G, Fabi, M, Lanari, M. Rhinovirus infection in children with acute bronchiolitis and its impact on recurrent wheezing and asthma development. Microorganisms 2020;8:1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8101620.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Bolle, PY, Souty, C, Launay, T, Guerrisi, C, Blanchon, T. Excess cases of influenza-like illnesses synchronous with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic, France, March 2020. Euro Surveill 2020;25:2000326. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.14.2000326.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Sakamoto, H, Ishikane, M, Ueda, P. Seasonal influenza activity during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Japan. JAMA 2020;323:1969–71. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6173.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Murillo-Zamora, E, Guzmán-Esquivel, J, Sánchez-Pia, R, Cedeo-Laurent, G, Mendoza-Cano, O. Coronavirus Pandemic Physical distancing reduced the incidence of influenza and supports a favorable impact on SARS-CoV-2 spread in Mexico. J Infect Dev Ctries 2020;14:953–6. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.13250.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Dhama, K, Khan, S, Tiwari, R, Sircar, S, Bhat, S, Malik, Y, et al.. Coronavirus disease 2019-COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020;33:e00028-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00028-20.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Fu, P, Xu, H, Jing, C, Deng, J, Wang, H, Hua, C, et al.. Bacterial epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance profiles in children reported by the ISPED program in China, 2016 to 2020. Microbiol Spectr 2021;9:e0028321. https://doi.org/10.1128/Spectrum.00283-21.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Zhu, X, Ye, T, Zhong, H, Luo, Y, Xu, J, Zhang, Q, et al.. Distribution and drug resistance of bacterial pathogens associated with lower respiratory tract infection in children and the effect of COVID-19 on the distribution of pathogens. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2022;2022:1181283. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1181283.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Mork, R, Hogan, P, Muenks, C, Boyle, M, Thompson, R, Morelli, J, et al.. Comprehensive modeling reveals proximity, seasonality, and hygiene practices as key determinants of MRSA colonization in exposed households. Pediatr Res 2018;84:668–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-018-0113-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Mork, R, Hogan, P, Muenks, C, Boyle, M, Thompson, R, Sullivan, M, et al.. Longitudinal, strain-specific Staphylococcus aureus introduction and transmission events in households of children with community-associated meticillin-resistant S aureus skin and soft tissue infection: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:188–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30570-5.Search in Google Scholar

17. Panda, S, Mohakud, NK, Suar, M, Kumar, S. Etiology, seasonality, and clinical characteristics of respiratory viruses in children with respiratory tract infections in Eastern India (Bhubaneswar, Odisha). J Med Virol 2017;89:553–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24661.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Tran, DN, Trinh, QD, Pham, NT, Pham, TM, Ha, MT, Nguyen, TQ, et al.. Human rhinovirus infections in hospitalized children: clinical, epidemiological and virological features. Epidemiol Infect 2016;144:346–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268815000953.Search in Google Scholar

19. Foley, D, Yeoh, D, Minney-Smith, C, Martin, A, Mace, A, Sikazwe, C, et al.. The interseasonal resurgence of respiratory syncytial virus in Australian children following the reduction of coronavirus disease 2019-related public health measures. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e2829–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1906.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Takashita, E, Kawakami, C, Momoki, T, Saikusa, M, Shimizu, K, Ozawa, H, et al.. Increased risk of rhinovirus infection in children during the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2021;15:488–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12854.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Savolainen-Kopra, C, Korpela, T, Simonen-Tikka, M, Amiryousefi, A, Ziegler, T, Roivainen, M, et al.. Single treatment with ethanol hand rub is ineffective against human rhinovirus--hand washing with soap and water removes the virus efficiently. J Med Virol 2012;84:543–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.23222.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Peltola, V, Waris, M, Osterback, R, Susi, P, Ruuskanen, O, Hyypiä, T. Rhinovirus transmission within families with children: incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic infections. J Infect Dis 2008;197:382–9. https://doi.org/10.1086/525542.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Xu, M, Liu, P, Su, L, Cao, L, Zhong, H, Lu, L, et al.. Comparison of respiratory pathogens in children with lower respiratory tract infections before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Shanghai, China. Front Pediatr 2022;10:881224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.881224.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Huang, Q, Wood, T, Jelley, L, Jennings, T, Jefferies, S, Daniells, K, et al.. Impact of the COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on influenza and other respiratory viral infections in New Zealand. Nat Commun 2021;12:1001. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21157-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Li, L, Wang, H, Liu, A, Wang, R, Zhi, T, Zheng, Y, et al.. Comparison of 11 respiratory pathogens among hospitalized children before and during the COVID-19 epidemic in Shenzhen, China. Virol J 2021;18:202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-021-01669-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Wu, A, Mihaylova, V, Landry, M, Foxman, E. Interference between rhinovirus and influenza A virus: a clinical data analysis and experimental infection study. Lancet Microbe 2020;1:e254–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2666-5247(20)30114-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Mendez-Brito, A, El Bcheraoui, C, Pozo-Martin, F. Systematic review of empirical studies comparing the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19. J Infect 2021;83:281–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2021.06.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Cowling, B, Ali, S, Ng, T, Tsang, T, Li, J, Fong, M, et al.. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e279–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30090-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Pinky, L, Dobrovolny, H. Coinfections of the respiratory tract: viral competition for resources. PLoS One 2016;11:e0155589. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155589.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Dobrescu, I, Levast, B, Lai, K, Delgado-Ortega, M, Walker, S, Banman, S, et al.. In vitro and ex vivo analyses of co-infections with swine influenza and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses. Vet Microbiol 2014;169:18–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.11.037.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Song, Q, Xu, BP, Shen, KL. Bacterial Co-infection in hospitalized children with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Indian Pediatr 2016;53:879–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-016-0951-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Liu, P, Xu, M, He, L, Su, L, Wang, A, Fu, P, et al.. Epidemiology of respiratory pathogens in children with lower respiratory tract infections in Shanghai, China, from 2013 to 2015. Jpn J Infect Dis 2018;71:39–44. https://doi.org/10.7883/yoken.jjid.2017.323.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Wang, H, Zheng, Y, Deng, J, Wang, W, Liu, P, Yang, F, et al.. Prevalence of respiratory viruses among children hospitalized from respiratory infections in Shenzhen, China. Virol J 2016;13:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-016-0493-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Do, AH, van Doorn, HR, Nghiem, MN, Bryant, JE, Hoang, TH, Do, QH, et al.. Viral etiologies of acute respiratory infections among hospitalized Vietnamese children in Ho Chi Minh City, 2004-2008. PLoS One 2011;6:e18176. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018176.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Avadhanula, V, Rodriguez, CA, Devincenzo, JP, Wang, Y, Webby, RJ, Ulett, GC, et al.. Respiratory viruses augment the adhesion of bacterial pathogens to respiratory epithelium in a viral species- and cell type-dependent manner. J Virol 2006;80:1629–36. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.80.4.1629-1636.2006.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Oxidative stress and antioxidants in health and disease

- Original Articles

- A new machine-learning-based prediction of survival in patients with end-stage liver disease

- Circulating pyridoxal 5′-phosphate in serum and whole blood: implications for assessment of vitamin B6 status

- The lncRNA prostate androgen-regulated transcript 1 (PART-1) promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression by regulating the miR-204-3p/IGFBP-2 pathway

- Antibody titer 6 months after the third dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccination

- Study on pathogen spectrum of 1,046 hospitalized children with respiratory tract infections during COVID-19

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Oxidative stress and antioxidants in health and disease

- Original Articles

- A new machine-learning-based prediction of survival in patients with end-stage liver disease

- Circulating pyridoxal 5′-phosphate in serum and whole blood: implications for assessment of vitamin B6 status

- The lncRNA prostate androgen-regulated transcript 1 (PART-1) promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression by regulating the miR-204-3p/IGFBP-2 pathway

- Antibody titer 6 months after the third dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccination

- Study on pathogen spectrum of 1,046 hospitalized children with respiratory tract infections during COVID-19