Abstract

This paper draws on principles of sound semiotics and parameters of voice quality to examine the vocal sounds of an Australian Rules footballer who ‘calls for the ball’ from their teammates in the ‘live’ action of a sporting contest. The paper will begin by locating this study in the emerging field of sports linguistics, including recent research which shows how language-in-action in sport ‘breaks down’ typical clause, grammatical and phonological structures to foreground the meaning making of voice quality. Having introduced the data set (ten instances of ‘calling for the ball’, by the same player, from the same game) the paper draws on perceptual analyses (supported by acoustic analysis) to characterise the player’s voice according to its most salient voice quality parameters: loudness, speed and tension. The paper then turns to the data set itself to further identify two distinct voice quality patterns, coined as experiential gestures: ‘grabbing’ and ‘tapping’. The paper concludes by flagging several areas of future research that emerged from the study, including the role of on-field sporting action vis-à-vis voice quality; the co-articulation of lexis and voice quality; and the materiality of voice quality and its intersubjective function.

1 Introducing language-in-action in sport

This paper locates itself within an emerging body of research that applies linguistics to sport (e.g. Caldwell et al. 2016; File et al. 2026; Ross et al. 2025; Walsh et al. 2024). This scholarship is especially diverse and broad in its scope, both in terms of the theories and methods of linguistics applied to sport, as well the various sporting contexts that are explored (see File et al. [2026] for the first handbook of language and sport). Whilst a key objective of this research is to better understand sport through language, Doran et al. (2025) note that applications of linguistics to sport can also tell us a lot about language and how it works. To date, most linguistic research in sports has tended to focus on sports media discourse, with studies into commentary and post-match interviews especially prominent. In more recent times, assisted by advances in audio recording technology, and the mediatization of on-field language tracking (Caldwell 2020), attention has turned to the language-in-action expressed by players participating in sport (see Ross et al.’s [2025] edited volume: Language in Sport: Real-time Talk in Training and Games). For example, File’s (2025) analysis of ‘in-race’ communication between drivers and engineers in professional Formula 1 motor racing revealed that seemingly ‘neutral’ articulations of time (specifying the distance between drivers) can also function as a means of emotional regulation in that high-speed, high-pressure sporting context. Stavridou (2025), in that same volume, showed how leadership is linguistically enacted and negotiated during breaks in play by players on a university basketball team, especially those that do not have a designated leadership role. And Wilson (2025), building on a body of research into rugby discourse, examined the ways in which coaches, during training sessions, strategically refer to their players (through pronouns, personal names and address terms) in order to mitigate a loss of face.

Alongside insights into sport through close language analysis, a particular interest here is how language operates in high pressure (time-sensitive) action-oriented contexts, where communication is critical to achieving the goals of the respective sport. As Doran et al. (2021: 276) explain:

despite sporting language being positioned as a canonical language-in-action mode, we have little sense of what such language actually looks like. We have little idea what forms of language are used, under what circumstances and what, in fact, happens to language under the extreme pressure to be useful in the here and now. (Doran et al. 2021: 276)

Doran et al. (2021) found that the closer language in sport is to the ensuing action, the more it tended to ‘break down’ traditional clause structures. Indeed, as they progressed their linguistic description from less close to more close to action – from instructions at training, to immediate feedback, to the ‘real-time’ language of players participating in sport – they found that not only did clause structures reduce to single repeated words, but that the English phonology itself also started to ‘break down’, with intonation contours flattening, feet evening, and a reduction in syllable structure (particularly the deletion of consonants in Coda position). Their critical point, and the inspiration for this paper, is that the meaning-making in turn shifted to (or foregrounded) the voice quality, and in particular, the parameters of loudness and speed. This paper therefore aims to expand on that original work from Doran et al. (2021) by examining more language-in-action in sport data, and by considering more closely van Leeuwen’s (1999, 2009, 2025) parameters of voice quality. Unlike Doran et al. (2021), this paper will focus on one particular speech act that is critical to so many sports: calling for the ball from a teammate. This study also deliberately limits the data set to extracts from the same speaker, from the same game of Australian Rules football; an especially physical, high-tempo, high-pressure sport.

The paper begins by introducing the data set, including a brief overview and analysis of the ways in which the player lexically realizes his ‘calls’ for the ball, from his teammates. Here, reference is made to Doran et al.’s (2021) hypothesis, that is, the extent to which the player’s language-in-action ‘breaks down’ the clause into short phrases and repeated single words. The remainder of the paper then focuses on the sound semiotics of the player’s voice, drawing from van Leeuwen’s (1999, 2009, 2025) parameters of voice quality. Based on a perceptual sound analysis, and supported by acoustic analysis, the paper explores the most salient features of the players’ voice quality, relative to an extract of non-language-in-action talk from the same player. These salient vocal features are then explored as meaning potentials through van Leeuwen’s experiential metaphor; the meanings assigned to the physical experience of producing those vocal sounds. The paper then pushes the analysis further by identifying two distinct patterns of voice quality within the data set. Again, the salient features of these patterns are explicated through perceptual and acoustic analysis, and ultimately ‘read’ as experientially meaningful choices made by the player. In the spirit of social semiotics (van Leeuwen 2005), the conclusion to this paper is deliberately broad, generative and future oriented, identifying three emerging themes from this study, namely: voice quality co-articulating with sporting action; voice quality co-articulating with lexis, and voice quality as a material, intersubjective, socializing agent. And whilst the paper builds on and ‘talks to’ Doran et al. (2021), as well as the broader field of language and sport, it is very much intended as a contribution to this special edition on sound semiotics, particularly in its methods of vocal sound analysis, the assignment of experiential meanings to the voice, and the identified areas of future research, namely: the critical relationship between on-field action and voice quality; the relations between lexis and voice quality; and the materiality of sound and its intersubjective function.

2 Data and methods

The data are taken from an amateur Australian Rules football match, involving elite Aboriginal Australian boys (aged between 14 and 16). Australian Rules football is a fast-paced, full contact game played between two teams of 18 players on an oval field, using an oval shaped ball, which is typically kicked to gain territory, and ultimately score points. Unlike most team-based ball-sports such as soccer, rugby (union and league) and American football, Australian Rules football does not have an offside rule, meaning players can move freely across the ground with or without the ball. Suffice to say, verbal and non-verbal communication is therefore critical to success (as well as physical perseveration) in Australian Rules football.

Small recording devices were attached to the players to capture their on-field language production (see Cominos et al. [2019: 98–99] for more detail on the project background and the novel method of data collection). The language data for this paper is from the same player, using the same microphone, taken from the first quarter of the match (approximately 30 min in duration). The data was then examined for any instances of the recorded player ‘calling for the ball’ from his teammate. In total, there were ten audible instances where the player used language to call for the ball from a teammate. Each extract is numbered, time-stamped and transcribed in Table 1.

Ten extracts of language-in-action (calling for the ball) in Australian Rules football.

| Extract | Time | Text |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35:18 | /yes /yes /yes /oi /Co-dy /Co-dy |

| 2 | 36:12 | /yeah /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy |

| 3 | 37:50 | /yeah /yeah /Gay-lor Gay-lor /back |

| 4 | 44:30 | /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai |

| 5 | 45:33 | /Bosh /Bosh /Bosh |

| 6 | 51:25 | /yeah /yeah |

| 7 | 51:30 | /here /here out /wide |

| 8 | 51:35 | a-/gain a-/gain a-/gain /quick a-/gain |

| 9 | 51:43 | /Jam-ie /Jam-ie if you /need /Jam-ie if you /need /Jam-ie Jam-ie Jam-ie if you /need |

| 10 | 53:20 | /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy |

Each new line (or boundary) in Table 1 represents a rhythmic phrase in van Leeuwen’s terms (1999, 2009, 2025), that is, there is a perceivable break between syllables that end one phrase and begin another (relative to the other syllable breaks in the same extract). These phrases also tend to be marked by a salient final syllable of the phrase (or nuclear rhythmic accent in van Leeuwen’s terms), which themselves tend to be realised by greater syllable duration, volume and/or pitch movement. However, nuclear rhythmic accents are not included in this initial transcript; it simply presents unstressed and stressed (or accented) syllables, where stressed syllables are in bold, and where groups of stressed and unstressed syllables in the same foot are identified with a forward slash “/”. Syllables within the same word are also marked with a hyphen. It is important to note, following van Leeuwen (2025) that these rhythmic accents and phrases were identified in an embodied way. That is, they were based on this authors’ aural and bodily responses to the rhythm of the player’s text, and not an acoustic analysis (although acoustic technology is used throughout this paper to support other perceptual analyses). Each extract (assigned a number in the far-left column) is a complete turn at talk (or ‘move’ in van Leeuwen’s terms). This aligns with the on-field sporting action itself, where each extract represents a completely new attempt to receive the ball from a teammate. Finally, proper names are marked with Capital initial, pseudonyms are used for anonymity, and the chosen pseudonyms follow the syllable and phonetic pattern of the original names.

Before turning to the meaning-making potential of the voice quality of these ten instances of language-in-action, it is important to start by briefly examining their lexical features. As noted in the title to this paper, and the introduction above, all extracts are instances of the command speech function (Halliday and Matthiessen 2004), where the fundamental illocutionary force of the speech act is for the speaker to get their teammate (the addressee) to pass them the ball (that the teammate has in their possession). However, the player calling for the ball from his teammate does not produce the unmarked complete clause: ‘pass me the ball’. Simply put, the high-pressure, action-oriented context of sport affords little time for participants to produce clause-length turns at talk. This of course follows seminal Systemic Functional Linguistic theorizing of the mode continuum (see e.g. Martin [1992] language-in-action) which was taken up in the context of sport by Doran et al. (2021), and more recently Caldwell (2025). As explained above, the basic argument of Doran et al. (2021) is that the closer language gets to action (which is especially the case in sport, and especially the case with the examples used in this paper), the more language tends to ‘break down’ the clause, and in turn, tends to rely on two-three word groups (or phrases), and/or repeated single words. Moreover, they argue that in the most extreme examples of language-in-action, higher ranks of the English phonology itself tend to break-down (intonation, rhythm and even syllable), and the meaning-making labour is distributed to vocal sound, and specifically the kinds of para-linguistic voice quality parameters that are the focus of this paper.

Returning to the lexis itself, the ‘breaking down’ of the clause is clearly illustrated in the ten extracts in Table 1, where the majority of extracts are realised by the repetition of the addressees’ name. In fact, of the 54 words expressed by the player to command his teammate to pass him the ball, almost half (26) were repeated expressions of the players’ name. Some extracts include the positive confirmations “yes” and “yeah”, which like the naming, is expressed as a single word, and typically repeated. Two extracts include repeated single prepositions – “back” and “here” – as well as one instance of a group – “out wide”. Another extract includes the repetition of the adverb “again”, and another, the adjective “quick”. In all these cases, the complete clause – ‘pass me the ball’ is essentially ellipted,[1] either through naming (e.g. ‘Cody, pass me the ball’); acknowledgments (e.g. ‘yes, pass me the ball’); prepositions of location (e.g. ‘here I am, pass me the ball’; ‘pass me the ball, here’), and the adverb and adjective (e.g. ‘pass me the ball, again/quick(ly)’. The only instance of a complete clause is Extract 9, where the player expresses the conditional clause – “if you need”. But again, even in this instance of a full clause, it is short (comprising only three words and three syllables), and its meaning is still ultimately dependant on the ellipted main clause – ‘(β) if you need, (α) pass me the ball’.

Despite their highly restricted forms, these texts are nonetheless highly meaningful, with the lexical choices being significant. For example. the polarity in those that only involve Modal Adjuncts “yes” or “no” significantly affects what is being asked: “yes” and “yeah” calls for the ball, whereas “no”, explicitly calls not to receive the ball. Similarly, calling another player’s name, rather than the teammate with the ball would express a different command, perhaps associated with that player getting into position, rather than calling for the ball. These may seem obvious points to make, but they are necessary to avoid a reading that suggests the lexis of language-in-action texts is incidental. Indeed, in the final discussion of this paper (Section 4), consideration will be given to recent theorizing in paralanguage (Ngo et al. 2022), and in particular, the intermodal relations between voice quality and the lexis discussed above (see also Ariztimuño [2025], and their work on the synergies between affect lexis and voice quality).

Having transcribed the language-in-action into rhythmic phrases, the next (and main) stage of the voice quality analysis was completed through a sequence of perception, then acoustic analysis. Drawing on van Leeuwen’s (1999, 2009, 2025) parameters of voice quality, the perception analysis was completed by this author and checked by another trained linguist. Having identified salient elements of voice quality in the player’s voice, where possible, an acoustic analysis through Praat (Boersma and Weenik 2008) was then used to support (or otherwise) those perceptions. For reasons of replicability, all Praat analyses in this paper were analysed at the unit of rhythmic phrase. Specifically, Praat was deployed for a loudness (or dB) analysis of the players’ voice quality. Praat was then also (and mainly) used to analyse for syllable duration. To do this, individual spectrograms were produced (see figures below) to identify the specific duration of a syllable. These images not only accurately illustrate the duration of a respective syllable, but when rhythmic phrases are relatively comparable in terms of their overall duration (which they mostly are in this data set), these images can illustrate the tempo or speed (fast to slow) of the speaker (see Section 3.2), as well as reveal particular patterns of vocal rhythm and syllable salience across a rhythmic phrase (see Section 3.5). Whilst pitch is occasionally discussed in this paper, for reasons of reliability and audio quality, these have not been analysed acoustically through Praat. Similarly, vocal tension, a noted feature of the player’s voice quality (see Section 3.3), has only been analysed according to perception, and not through Praat acoustic analysis.

3 Results: voice quality

The following vocal sound analysis of a footballer ‘calling for the ball’ draws on van Leeuwen’s (1999, 2009, 2025) parameters of voice quality, as well as his embodied approach to sound analysis. As noted, the analysis is primarily based on an embodied, perceptual analysis of the data, supported where possible, by acoustic analyses.

In comparison to regular speaking, all of the extracts can be generally classified as maximally loud, maximally fast, and maximally tense. While other parameters of voice quality – rough/smooth, breathy/non-breathy, high/low pitch level, and wavering voice quality – are present, they are, in comparison to loudness, speed and intensity, not particularly salient. In other words, the player’s voice is not particularly rough or smooth, breathy or non-breathy, high or low, or discernibly wavering in its quality. However, what is clear, both perceptually, and supported by acoustic analyses, is that this player’s voice is loud, fast and tense when calling for the ball from their teammate.

Before turning to what this might ‘mean’ experientially, it is important to first unpack these perceptual classifications. One way of doing this is to compare the language-in-action extracts with an extract produced by the same player, from the same game, but in a different context, that is, not in the high-pressure language-in-action context of calling for the ball. To that end, Example 1 is a short, spoken transcript from quarter time of that same game. In Australian Rules football, quarter time is a lengthy stoppage in play, in which the game is paused so that players can rest, as well as communicate with each other and their coach (to allow it to be compared to other sports, hereafter it will be referred to as the ‘time out’ text, following Caldwell [2025]). So whilst Example 1 occurs in the broader context of sport, it is not the same kind of intense language-in-action setting as when a player is calling for a ball. For comparison with the language-in-action extracts in Table 1, the transcript in Example (1) has also been analysed into rhythmic phrases, with each phrase represented by a new line, and stressed syllables marked with a forward slash / and bold font.

| and uh /al-so with /switch-es |

| /don’t um /switch in-to /traff-ic |

| if ya /wann-a /switch |

| and you /know you have /space |

| switch /wide as /well |

What becomes immediately clear, when compared with the rhythmic analysis of those language-in-action extracts in Table 1, is the length of the rhythmic phrases in terms of syllables per phrase. They are clearly longer in the time out segment. Or put the other way: rhythmic phrases are much shorter in terms of the number of syllables that occur in the language-in-action examples. On average, the language-in-action examples comprise 3.69 syllables per rhythmic phrase (23 phrases/85 syllables), whereas the time out text comprises an average of 5.80 syllables per phrase (5 phrases/29 syllables). And whilst it is beyond the scope of this paper to further unpack this lexis, it is clear that the rhythmic phrases of the time out text are far more complex compared with the language-in-action, with the time out text comprising (mostly) complete clauses, as well as some clause complexing (supporting the work of Doran et al. 2021; Caldwell 2025). From a sound semiotic perspective, the critical point to note here is the experiential implications of this finding. In short, short rhythmic phrases such as those identified in the language-in-action extracts in Table 1 produce an increase of stressed syllables relative to unstressed syllables. And like syllables per rhythmic phrase, this can be quantified. The language-in-action extracts comprise 51 stressed syllables to 34 unstressed syllables (a total of 60 % stressed syllables). Whereas the time out talk comprises 11 stressed syllables to 18 unstressed syllables (a total of 38 % stressed syllables). It should also be noted that this is a very conservative reading; if the tonic syllables (or nuclear rhythmic accents) were included, then it would show an even greater rhythmic intensity in the language-in-action context compared with the time out text.

3.1 Maximally loud

Compared with the time out text, the player, when calling for the ball, is especially loud. Indeed, in many instances, one would perceptually classify their speech as shouting and even screaming. In support of this perception, the above identification of frequently stressed syllables can itself be read as a potential indicator of loudness. Syllable stress is produced, in part, by an increase in amplitude (acoustically measured as decibels). Or, from an experiential perspective, these players are frequently expelling an especially forceful egressive airstream from their lungs, through their vocal tract, and out through their articulators. This also says a lot about the setting of language-in-action in sport, and specifically, the proximity of addresser to addressee and the critical need for audibility. In the context of language-in-action, the player is not always close to the player from whom they wish to receive the ball (their addressee). Hence the clear and perceptible increase in volume. In contrast, in the time out text, the player is in close proximity; there simply is not the same need to increase loudness.

In support of this perceptual classification, we can also draw on the acoustic analysis software Praat (Boersma and Weenik 2008). Table 2 shows three decibel (dB) readings for each of the ten language-in-action extracts, calculated for each rhythmic phrase: the average dB reading, the maximum dB reading, and the minimum dB reading. Of particular note are the bolded figures at the bottom of the table, which capture the dB averages for the ten language-in-action extracts.

Loudness as decibels (dB) in language-in-action (calling for the ball).

| Extract | Text | Average (dB) | Maximum (dB) | Minimum (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | /yes /yes /yes /oi /Co-dy /Co-dy |

88.51 89.41 |

91.53 91.63 |

69.21 76.14 |

| 2 | /yeah /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy | 89.26 | 91.64 | 79.10 |

| 3 | /yeah /yeah /Gay-lor Gay-lor /back |

90.10 89.98 |

91.14 91.60 |

84.75 74.65 |

| 4 | /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai |

89.91 90.27 90.49 |

91.67 91.72 91.63 |

78.29 78.50 81.83 |

| 5 | /Bosh /Bosh /Bosh | 80.17 | 89.86 | 69.02 |

| 6 | /yeah /yeah | 87.10 | 91.31 | 69.14 |

| 7 | /here /here out /wide |

88.65 90.83 |

91.31 91.82 |

78.00 82.72 |

| 8 | a-/gain a-/gain a-/gain /quick a-/gain |

89.69 90.38 90.24 |

91.57 91.39 91.45 |

70.04 86.45 83.49 |

| 9 | /Jam-ie /Jam-ie if you /need /Jam-ie if you /need /Jam-ie Jam-ie Jam-ie if you /need |

88.99 87.12 89.22 |

91.26 91.09 91.57 |

76.78 79.11 77.35 |

| 10 | /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy |

88.37 88.70 90.02 90.44 90.13 |

91.53 91.86 91.76 91.82 91.85 |

77.17 79.37 84.79 83.44 83.35 |

| Average language-in-action dB | 89.04 | 91.47 | 78.37 | |

In short, from an acoustic/dB reading, the player is consistently loud. In fact, the player’s voice, both as an average (89.04 dB) and maximum reading (91.47 dB), is generally considered shouting (Berger et al. 2020). Furthermore, Table 3 shows that the player’s language-in-action voice is significantly louder than his time out voice: a statistical difference of 9.1 dB (average), 5.52 dB (maximum), and 15.51 dB (minimum). This is particularly noteworthy given that loudness is measured on a logarithmic scale where an increase of 10 decibels (dB) represents a 10-fold increase in sound intensity and essentially a doubling of the perceived loudness (Rossing 2007). Suffice to say, both perceptually and acoustically, the player’s language-in-action, when calling for the ball, is unquestionably loud.

Loudness as decibels (dB) in time out.

| Text | Average (dB) | Maximum (dB) | Minimum (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| and uh /al-so with /switch-es /don’t um /switch in-to /traff-ic if ya /wann-a /switch and you /know you have /space switch /wide as /well |

79.42 81.50 80.03 80.57 78.21 |

85.06 88.78 84.17 85.72 86.02 |

62.64 61.90 65.70 62.74 61.35 |

| Average time out dB | 79.94 | 85.95 | 62.86 |

3.2 Maximally fast

The classification of the player’s voice as maximally fast is also especially audible. Like loudness, this perception can be supported by calculations of the number of syllables expressed per second (or SPS) (Arnfield et al. 1995), as well as acoustic measurements through Praat spectrograms which offer a close analysis of syllable duration and proximity (relative to other syllables). Table 4 shows that the language-in action is calculated at a total rounded average of 6.68 syllables per second (SPS), across the complete data set. The specific calculations listed in Table 4 are based on the immediate start and end of a rhythmic phrase. This way, any significant break between a rhythmic phrase is not considered part of the overall calculation.

Speed as syllables per second (SPS) in language-in-action (calling for the ball).

| Extract | Text | Syllables | Time | SPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | /yes /yes /yes /oi /Co-dy /Co-dy |

3 5 |

0.74 0.86 |

4.05 5.81 |

| 2 | /yeah /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy | 7 | 0.74 | 9.45 |

| 3 | /yeah /yeah /Gay-lor Gay-lor /back |

2 5 |

0.27 0.65 |

7.40 7.69 |

| 4 | /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai |

6 3 3 |

0.74 0.53 0.64 |

8.10 5.66 4.68 |

| 5 | /Bosh /Bosh /Bosh | 3 | 0.59 | 5.08 |

| 6 | /yeah /yeah | 2 | 0.37 | 5.40 |

| 7 | /here /here out /wide |

1 3 |

0.21 0.48 |

4.76 6.25 |

| 8 | a-/gain a-/gain a-/gain /quick a-/gain |

6 1 2 |

0.86 0.32 0.50 |

6.97 3.12 4.00 |

| 9 | /Jam-ie /Jam-ie if you /need /Jam-ie if you /need /Jam-ie Jam-ie Jam-ie if you /need |

7 5 9 |

0.65 0.39 0.95 |

10.76 12.82 9.47 |

| 10 | /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy |

4 2 2 2 2 |

0.5 0.25 0.31 0.42 0.39 |

8.00 8.00 6.45 4.76 5.12 |

| Average language-in-action SPS | 6.68 | |||

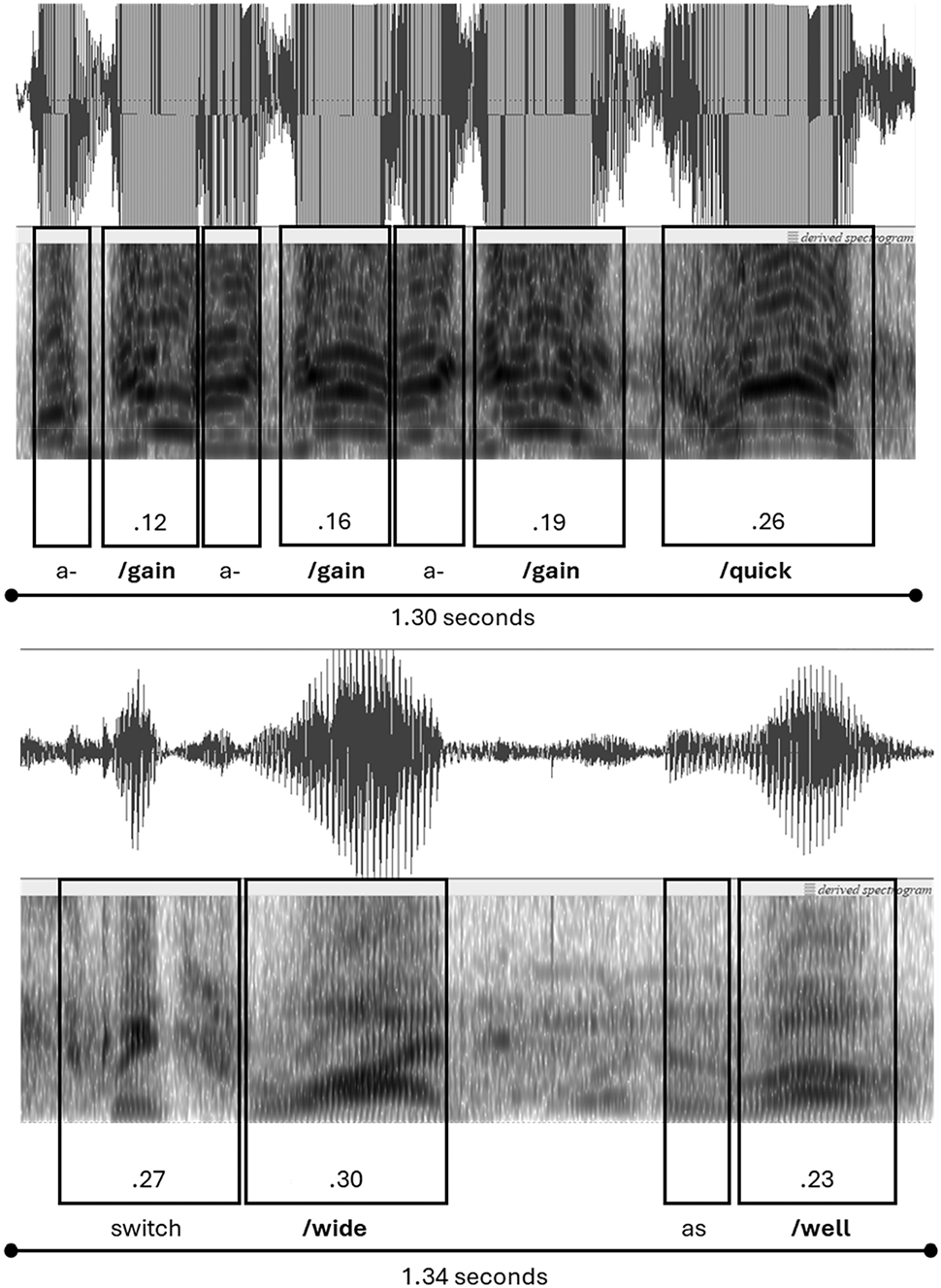

A rate of around 7 syllables per second is considered fast for English, with the average SPS for an English speaker typically around 4–5 SPS (Tauroza and Allison 1990). Put another way, the language-in-action is almost double the ‘normal’ speed of an English speaker. This fast speed can also be represented visually using Praat spectrograms. Figure 1 compares two Praat spectrograms from the language-in-action data set:[2] Extract 8 “a/gain a/gain a/gain /quick”, and the final imperative clause from the time out text: “switch /wide as /well”. Of import here, and the reason why the final rhythmic phrase of Extract 8 is not included (see Table 1), is that the total duration of these two excerpts is almost identical: 1.30 and 1.34 s respectively. This provides an excellent visual comparison of not only the number of syllables being articulated over an identical time period, but also the length of syllables, and equally as important, the duration of silence between those syllables.

Comparing speed as SPS: language-in-action versus time out.

It is clear in Figure 1 that the language-in-action excerpt is crammed with syllables, relative to the time out text. The time out text has fewer syllables, and also larger gaps between those syllables. This is particularly noteworthy given that the time out text itself is relatively fast itself when compared with the ‘normal’ SPS of English, at around 5.5 syllables per second, presented in Table 5. This likely says something about the temporal, physical and emotive pressure of the time out, as part of the broader context of sporting competition. In any case, the ultimate point being illustrated here is that the language-in-action is fast; it is both faster than regular English speech on average, and faster than the comparable time out text as shown in Figure 1.

Speed as syllables per second (SPS) in time out.

| Text | Syllables | Time | SPS |

|---|---|---|---|

| and uh /al-so with /switch-es /don’t um /switch in-to /traff-ic if ya /wann-a /switch and you /know you have /space switch /wide as /well |

7 7 5 6 4 |

1.30 1.47 0.55 0.91 1.22 |

5.30 4.76 9.00 6.60 3.27 |

| Average time out SPS | 5.55 | ||

The fast SPS calculation, and these visual images, very much support this author’s perception of language-in-action as fast, coupling with loudness, and an especially high frequency of syllable stress. This rhythmic intensity is clearly visible in the spectrograms in Figure 1, represented by intense saturation of the formants (shown by the darker stretches) on the bottom row of the language-in-action example compared with the time out example, as well as thick(er) and tall(er) lines on the top row of the first spectrogram. In summary, the player’s coupling of loudness (measured as dB), with fast syllable articulation (measured as SPS), and the many, often consecutive salient stressed syllables points to two critical features of his language-in-action voice: (1) an extreme physical exertion required to produce this particular voice quality, and (2) a final parameter of voice quality that also characterises this language-in-action voice – tension.

3.3 Maximally tense

Vocal tension, like loudness and speed, is very perceivable when the player is calling for the ball. This makes sense based on the preceding analyses: a high frequency of stressed syllables, accompanied by loudness, and expressed at a fast speed, indicates a level of physical exertion, and by implication, vocal tension on the part of a speaker (see e.g. Caldwell [2014a, 2014b, 2022] and his analysis of voice quality in rap music). Put another way, it is especially difficult to articulate the number of stressed syllables produced by this player with a lax voice quality, coupled with their extreme volume (shouting), and further coupled with a short period of time in which they articulate those stressed syllables. Again, the vocal tension in extracts 1–10 is clearly audible, especially compared with the time out talk produced by that same player. And whilst it is not possible to acoustically analyse for such tension, the rhythmic analysis, as well as the loudness and speed analyses, indicate significant tension in the player’s voice quality, across all extracts.

3.4 An experiential reading

Having established the salient parameters of voice quality in the players’ language-in-action – loud, fast and tense – it is now possible to assign meaning potentials to these features. Following van Leeuwen (1999, 2009, 2025), one way of doing this is through the body of the articulator, or more technically, the experiential[3] metaphor: “the idea that our experience of what we physically have to do to produce a particular sound creates a meaning for that sound” (van Leeuwen 1999: 205). In other words, the meaning potentials are the salient experiential vocal parameters. In fact, voice quality tends to afford meaning potentials vis-à-vis the identity and/or feelings of the individual producing the sound. Or as van Leeuwen (2025) explains, “voice quality is a semiotic resource for the expression of identity as well as for the expression of fleeting states and emotions”.

Drawing on van Leeuwen’s experiential metaphor, Caldwell (2014a, 2014b, 2022) deploys grammatical frames from Systemic Functional Linguistics (Halliday and Matthiessen 2004) and interpersonal semantics from the Appraisal system of Attitude (Martin and White 2005) to help assign experiential meanings in terms of the broad semantic space in which they are located. For example, for Caldwell (2014a, 2014b, 2022), a designated experiential meaning such as ‘tense’ can be considered an Attribute in a relational clause, where the sound itself is the Carrier, e.g. ‘the sound is tense’ (constructing an Appreciation of something in Attitude terms). Similarly, it can be an Attribute in a relational clause, where the producer of the sound is the Carrier, e.g. ‘that speaker is tense’, or ‘I am tense’ (constructing a Judgement of someone in Appraisal terms). Finally, when ‘feel’ is used as the main verb in the grammatical construction, either as a relating clause (where the Carrier is the producer or receiver of the sound), or as a sensing clause (where the Sensor is the producer or receiver of the sound), one is also able to assign Affect (or feelings) in Attitude terms, e.g. ‘I feel tense when I produce that sound’; ‘that sound feels tense [to me]’.

Returning to the language-in-action data, Table 6 presents a set of experiential meaning potentials, with the first column on the left-side showing the grammatical frame, the middle column showing the respective Attitude category, and the far-right column showing the respective meaning potentials based on the preceding perceptual (and acoustic) analyses.

Experiential meanings for language-in-action (calling for the ball).

| Grammatical frame | Attitude | Meaning potentials |

|---|---|---|

| Sound is [sound parameter] | Appreciation | Loud (noisy, booming, thundering) Fast (quick, rapid, speedy) Tense (tight, taught, rigid) |

| Person is [sound parameter] | Judgement | Loud (blatant, intent, vociferous) Fast (brisk, hasty, expeditious) Tense (still, inflexible, unyielding) |

| I feel [sound parameter] | Affect | Loud (resounding, sonorous, ear-piercing) Fast (hurried, rushed, sped up) Tense (nervous, uneasy, agitated) |

Like van Leeuwen (1999, 2009, 2025), and following Caldwell (2014a, 2014b, 2022), Table 6 also draws on near synonyms (Cambridge University Press and Assessment 2025) to assign additional meaning potentials associated with the three salient voice quality parameters of loudness, speed and tension. For example, as shown in the far-right column of Table 6, ‘tense’ as an Attribute of the sound can be associated with synonyms such as ‘tight’, ‘taught’ and ‘rigid’. Or, in the case of ‘fast’, and in relation to the kinds of feelings this might generate for both the producer and receiver of that sound, example meaning potentials might include feeling ‘hurried’, ‘rushed’ or ‘sped up’. To be clear, these meaning potential are just that – potentials. Following van Leeuewn (1999), the meanings assigned in Table 6 are not intended to be straightjackets that must be assigned to each and every instance of the language-in-action expressed by these players when calling for the ball from their teammate. At the same time, they help to construct an overall semantic field that is generally consistent with the kinds of meanings, identities and feelings one perceives from these extracts. It should also be noted that whilst Attitude is helpful in terms of explicitly shifting the ideational target (from sound, to identity, to feelings), positive and/or negative valence (the ‘good/bad’ parameter [Thomson and Hunston 2000]) need not be applied here. For example, assigning the attribute of ‘tense’ to this player is not done with some sort of negative valence, that is, they are ‘too emotive’, and therefore aggressive and unpredictable. Whilst there might be scope to extend the framing of voice quality in Attitude terms to positive and negative valence in other contexts, that is not the intention of this paper. For readers interested in a detailed system network for features of voice quality and their affectual (or emotive) realizations, see Ariztimuño (2025) in this Special Issue.

Having now established a set of experiential meaning potentials, the analysis will turn to a closer reading of the language-in-action data in and of itself, that is, exploring that data set for distinctive patterns of sounds variables which are not read in relation to the time out text, nor in relation to ‘standards’ of English voice quality.

3.5 Emerging patterns

Two patterns of voice quality emerged from this language-in-action data, which can be loosely coined in experiential terms as the ‘grab’ and the ‘tap’ (or the ‘grabber’ and ‘tapper’ personas). In terms of feelings (Martin and White 2005), the former – ‘the grab’ – can also be classified as directed affect; an ‘emotive plead’ or a ‘crying out’ (for the ball). By contrast, the second vocal patterning – the ‘tap’ – seems to be better classified in terms of an affectual state of insecurity, such as ‘eager’ or ‘anxious’ (to receive the ball). Before unpacking these two emerging types of voice quality further – the ‘grab’ and the ‘tap’ – it is important to note that both voice qualities, and the language-in-action data generally, should still be considered fundamentally loud, fast and tense.

The first two extracts from the language-in-action data set (Table 1) provide a useful starting point to explore these patterns, particularly because they have similar lexical realizations, that is, they express the same player’s name (“Cody”), and both begin with a marker of acknowledgement (see Example (2)):

| Extract 1: /oi /Co-dy /Co-dy |

| Extract 2: /yeah /Co-dy /Co-dy /Co-dy |

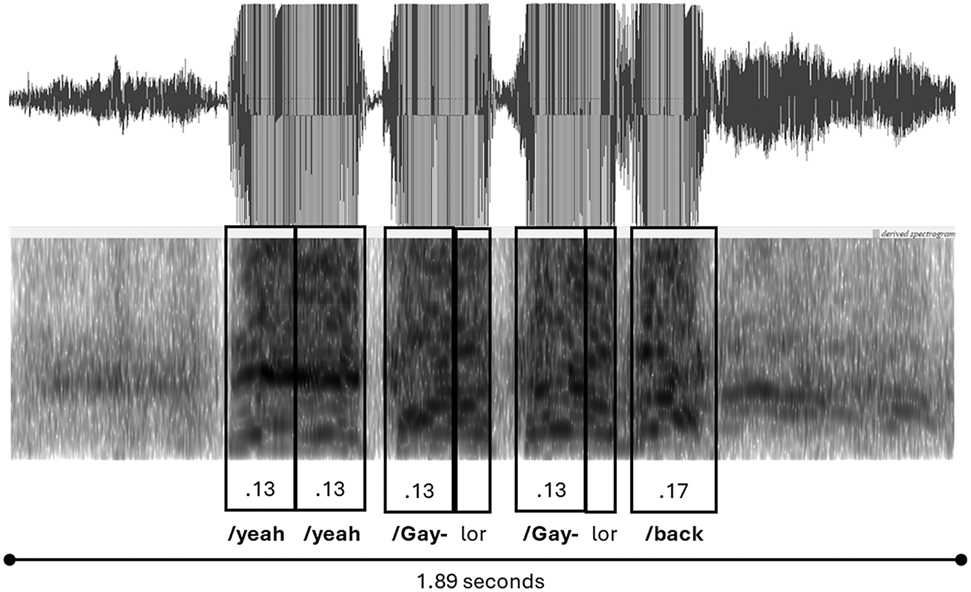

Despite their similar lexis, and their salient loudness, speed and tension, there are perceivable differences in the voice quality of these two extracts. These differences in turn produce different experiential readings: the first extract is perceived as a more highly emotive ‘plead’; the player is metaphorically ‘grabbing’ their teammate in order to receive the ball. In the second extract however, perceptually, the voice has more of an urgent, pragmatic quality; the player is repeatedly ‘tapping’ (metaphorically) their teammate in order to receive the ball. This perception is supported by the speed analysis undertaken in Table 4. Extract 1 expresses 5 syllables over 0.86 s for an SPS of 5.81, however, the rate of delivery of Extract 2 is almost double this, with 7 syllables expressed across a shorter duration (0.74), for a SPS of 9.45: an especially fast rhythmic phrase, and indicative of an experiential ‘tapping’. In terms of loudness, the difference is marginal. Extract 1 and 2 are basically equivalent in terms of the average dB reading of the excerpt and the maximum dB (see Table 2). Although there is a more than 4 (dB) difference between Extract 1 and 2 in terms of their softest sound, with the former – the grab – having a much lower point (69.21 and 76.14 dB) compared to Extract 2 (79.10 dB) – the ‘tap’ – perhaps indicative of a more experientially expansive ‘grab’, compared with a more predictable and experientially contained ‘tap’.

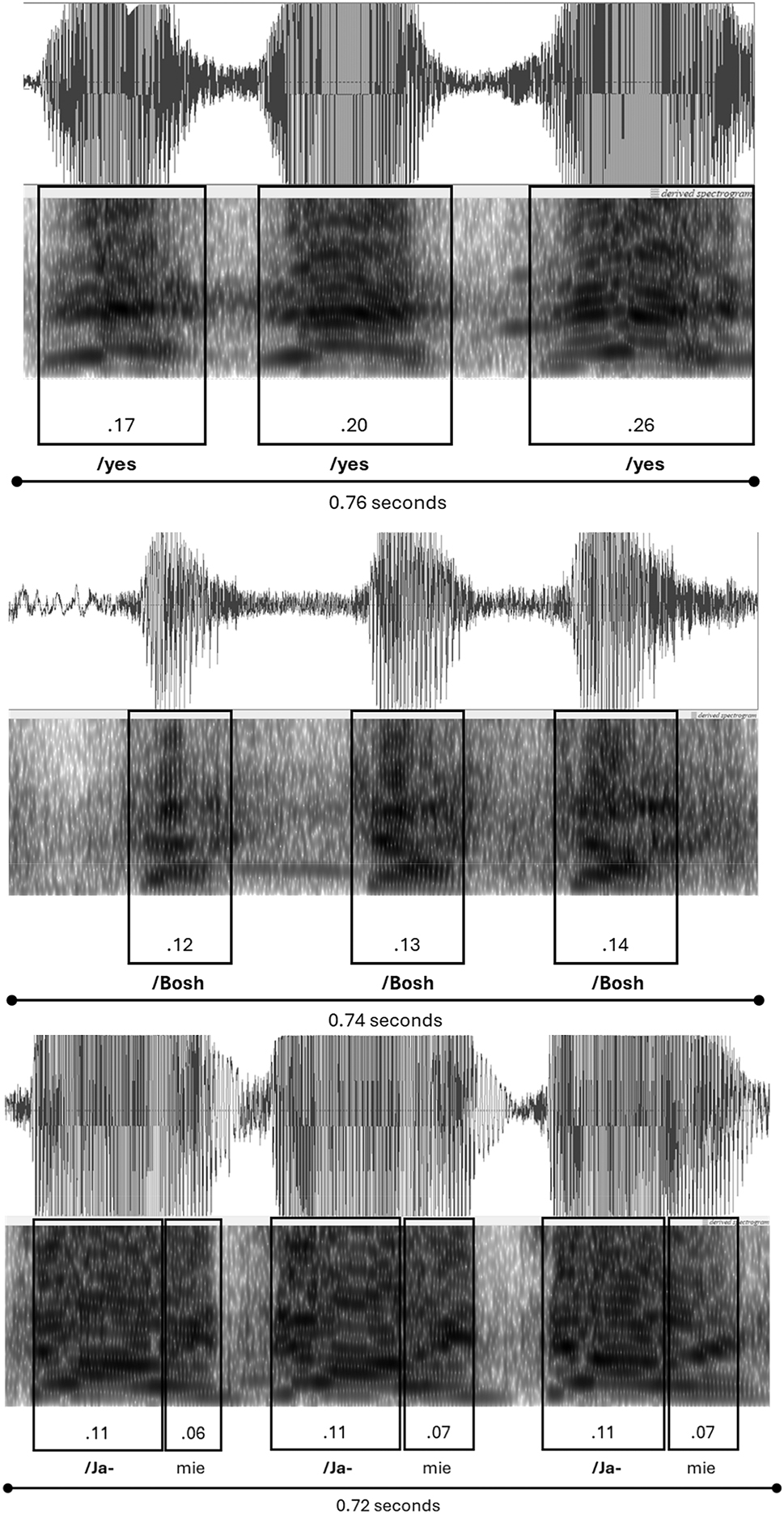

Syllable duration also plays a key role in the production of these distinct voices. By way of illustration, the three extracts in Example (3) are comparable in their respective syllable duration, with Extract 1 indicative of the ‘grabbing’ voice, Extract 9 the ‘tapper’, and Extract 5 between these two extremes of syllable duration.

| Extract 1: /yes /yes /yes |

| Extract 5: /Bosh /Bosh /Bosh |

| Extract 9: /Jam-ie /Jam-ie /Jam-ie |

Figure 2 presents Praat spectrogram analyses of these three extracts. The extracts are of similar total durations which assists with comparative analysis (approximately 0.75 s in total). They also comprise three repetitions of the same lexis. The point here is to not only compare equivalent durations across the respective visual representations, but to also compare the consistency (or otherwise) of duration across the repeated syllables within the same rhythmic phrase.

Comparing syllable duration and speed in language-in-action (calling for the ball).

We can see the most variation in stressed syllable length is in the top image (Extract 1); the least variation in the final image (Extract 9), and the middle image represents something between these two extremes, that is, some minor variation in syllable duration. Also of importance to the experiential readings of ‘grabbing’ and ‘tapping’ is not simply variation in stressed syllable duration, but an increase in that duration over time (both perceptually and acoustically), with Extract 1 moving from shorter to longer syllables: 0.17 to 0.20 to 0.26. Extract 5 (the middle image) also shows slight increases in stressed syllable duration, albeit less significant statistically, but nevertheless perceivable. And finally, Extract 9 has almost no perceivable or measurable increase across the repeated stressed syllables (besides a 0.01 increase in the second unstressed syllable, between the first and second utterance). This increase in duration (clearly audible and visible in Extract 1, and to a lesser extent in Extract 5), can also be found in Figure 1, where Extract 8 – “a/gain a/gain a/gain”– comprises increasing syllable durations of 0.12 to 0.16 to 0.19, followed by a new rhythmic phrase of an especially elongated syllable: “/quick” (0.29). Although beyond the scope of this paper, it is also worth noting for future research that the pitch of many of these long final syllables are perceived as high (relative to the preceding syllables), and in some cases carry a marked pitch movement (wide pitch range and wavering pitch), for example “/quick”(Extract 8) and the final “/kai” syllable in Extract 4 (Figure 3 below).

Grabbing and tapping in language-in-action (calling for the ball).

Before turning to some final examples, it is important to return to the respective experiential meanings, feelings and identities introduced above. For the ‘grabbing’ voice, represented by Extract 1 and Extract 8 (the first spectrogram of Figure 1); the vocalizations build up; they crescendo (or climax) to a point of extreme duration. The ‘grabbing voice’ voice is highly energized, culminating to a point of intense vocal exertion. The tapping voice however (Extract 9, the bottom spectrogram of Figure 2) is more predictable and mechanical. Again, that is not to suggest that it is not loud, fast and tense. It is very much fast, urgent and forceful in its vocal realization. However, it is ultimately more controlled, more predictable, repetitive, and ultimately more experientially contained than the ‘grabbing’ voice.

Another point to note before moving on is that these voices are not binaries of either ‘grabbing’ or ‘tapping’. These voices are gradable; one can be between these distinct voice qualities, as illustrated in Extract 5. As van Leeuwen (1999, 2009, 2025) and Ariztimuño (2025) frequently make clear, when dealing with voice quality, we are dealing with gradability. The meanings being made through sound must be conceptualized along a cline from most to least. And in turn, any clustering of these parameters that might reveal particular emotional states and identities, should also be conceptualized as gradable; from grabbing to tapping, not grabbing or tapping.

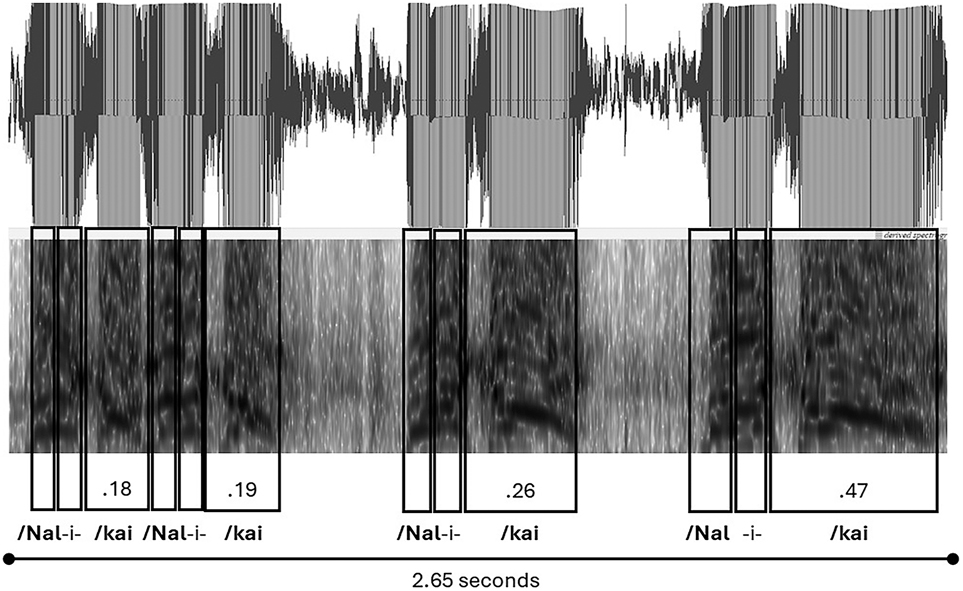

There are also examples in the language-in-action data set where the player deploys both a ‘grabbing’ and ‘tapping’ voice quality within the same move, that is, within the same attempt to receive the ball from his teammate. Extract 4 for example, which only comprises the repetition of a teammates name – “/Nal-i-/kai” – is such an example, and is presented as both a rhythmic transcription in Example (4) and then as a spectrogram image in Figure 3 below.

| Extract 4: |

| /Nal-i-/kai /Nal-i-/kai |

| /Nal-i-/kai |

| /Nal-i-/kai |

At first glance, the spectrogram image for Extract 4 could be mistaken for a ‘grabbing’ voice, with increases in the syllable duration of the final stressed syllable for each repetition. However, it is not perceived as such. The first two instances of “/Nal-i-/kai” are very much ‘tapping’ in their quality. Whereas the final two expressions are much more like grabbing. Indeed, on closer inspection of the spectrogram, the first two instances have qualities much more aligned with the previous examples of ‘tapping’. They are almost identical in duration. This is comparable with the third and fourth expressions of the teammate’s name, where there is a clear increase in the duration of the final stressed syllable “/kai”.

Another example of shifting voice quality within a single move is found in Extract 3, presented as Example (5). In this case, the first two repeated acknowledgements of “/yeah /yeah”, are perceived with a consistent ‘tapping’ quality. By contrast, what follows in that same move – the repeated articulation of the teammates name and a final preposition – has far more syllable length as it crescendos to a final lengthy plea – “/back”.

| Extract 3: |

| /yeah /yeah |

| /Gay-lor /Gay-lor /back |

In Figures 3 and 4 the sequence is the same: tapping followed by grabbing. In experiential terms, this sequence makes sense, that is, the player attempting to receive the ball begins with, relatively speaking, a more moderate voice quality in its experiential intensity. And then, if unsuccessful, they turn to a more heightened ‘grab’, comprising a crescendo of syllable length. Related to this explanation is the ensuing on-field action (a topic discussed below in Section 4). Simply put, time is a critical variable here. And the longer a player has the ball, the more likely they are to have it taken from them by the opposition. Accordingly, it is likely that the crescendo of the player calling for the ball matches the increased pressure that the teammate is under.

Grabbing and tapping in language-in action (calling for the ball).

4 Conclusion: meaning and material

Drawing on the principles of sound semiotics (van Leeuwen 1999, 2009, 2025), applied to sport (Caldwell et al. 2016; Ross et al. 2025; Walsh et al. 2024), this paper has explored the meaning making potential of voice quality within the context of a specific type of language-in-action in sport: calling for the ball. The paper began by exploring the lexis itself, not simply to introduce the data, but to support the work of Doran et al. (2021) and Caldwell (2025) who argue that language-in-action tends to ‘break down’ traditional structures (evident again in this data set), with the meaning making responsibility redistributed to salient features of voice quality. The paper then analysed ten instances of a player ‘calling for the ball’ from his teammate, drawing on van Leeuwen’s (1999, 2009, 2025) parameters of voice quality. In summary, it was perceived (and supported by acoustic analysis) that the player’s voice, in these instances of calling for the ball was loud, fast and tense. Those salient parameters of the player’s voice quality were then explored semiotically through an experiential reading, whereby the physical experience of producing loud, fast and tense sounds realised that same meaning potential. Drawing on Caldwell (2014a, 2014b, 2022), the paper then systematically assigned experiential meaning potentials to the perception of the vocal sound itself; to the player producing the vocal sound (identity); and to the emotive experience typically associated with producing the vocal sound (affect). Ultimately, this analytical process resulted in the production of a semantic field that can be assigned to the act of calling for the ball in the sport of Australian Rules, including terms such as: tight, taught, rigid, noisy, booming, thundering, quick, rapid, speedy, still, inflexible, unyielding, blatant, intent, vociferous, brisk, hasty, expeditious, nervous, uneasy, agitated, resounding, sonorous, ear-piercing, hurried, rushed, and sped up. Looking more closely again at the data set of language-in-action, the paper also found two distinct, albeit gradable, patterns of voice quality in the data, which were respectively coined the ‘grabbing’ and ‘tapping’ voice. These voice types were analysed and unpacked accordingly, with acknowledgment given to the fluidity of these voice qualities, their meaning making potential, and as will be discussed below, their intersubjective functions in the context of calling for the ball.

Of course, any social semiotic does not end at the assignment of meaning potentials. As van Leeuwen (2005) notes when introducing his readers to social semiotics:

Social Semiotics is not ‘pure theory’, not a self-contained field. It only comes into its own when it is applied to specific instances and specific problems, and it also requires immersing oneself not just in semiotic concepts and methods as such but also in some other field […]. The same applies to the ‘social’ in social semiotics. It can only come into its own when social semiotics fully engages with social theory. This kind of interdisciplinarity is an absolutely essential feature of social semiotics.

Social semiotics is a form of inquiry. It does not offer ready made answers. It offers ideas for formulating questions and ways of searching for answers. This is why I end my chapters with questions rather than conclusions. These questions are not intended to invite readers to ‘revise’ the content of the preceding chapter but to encourage them to question it, to test it, to think through independently – and arrive at their own conclusions. (van Leeuwen 2005: 1)

In the case of the first point, there are of course many other fields which would prove insightful in relation to these findings. Of relevance to this study would be research into sport, especially the fields of sports sociology and sports psychology, no doubt generating insights into why these players make the meanings that they do. Similarly, the field (and industry) of high performance in sport might consider the physiological implications of these findings – what is the physical impact and implications of such loud, fast, tense vocalizations? Or, are some types of vocalizations more effective (or otherwise) than others in terms of their intended outcome? Is there an optimal number of lexical repetitions? Is naming more effective in calling for the ball than prepositions of location?

In concluding this paper, and very much in the spirit of social semiotics noted in the van Leeuwen (2005) quote above, three topics generated from this study will be addressed, all of which lend themselves to more questions, and in turn, provocations for future research. The first relates to the on-field action that accompanies these instances of calling for the ball. For example, did the player actually receive the ball as a result of their vocalizations? What about the role of proximity, both between speaker and receiver, as well as receiver and opponent (see for example the earlier comments regarding the relationship between the ‘grabbing’ voice and the proximity [pressure] of an opponent). This kind of visual data (capturing the on-field location and action of players) in turn lends itself to other questions and potential theorizing related to high performance noted earlier, such as how effective were the meanings produced by the player’s voice quality? Is it more effective to grab or tap? Unfortunately, across these ten instances, the visual data needed to ascertain both the effect of the speech act (received or not), as well as proximity of the players, was not consistently available. It is worth nothing that Doran et al. (2021) includes three examples from this same data set, which do include some on-field contextual information, and which in turn, is effectively interpreted vis-à-vis the vocalizations. Suffice to say, capturing the on-field action is critical to future studies into language-in-action in sport (see also Doran et al. 2025). At the same time, if one’s focus is an analysis of voice quality specifically, caution does need to be taken to not become overwhelmed with a multimodal ensemble of action, gesture, proximity, touch, lexis and the like; ensembles where the aural mode, and the meanings of voice quality, is often marginalized.

In this general spirit of multimodality and the recent work in paralanguage within Systemic Functional Semiotics (Ngo et al. 2022), the second topic relates to the intermodal relations between voice quality and lexis that constitutes ‘calling for the ball’. Whilst we clearly observe a ‘breaking down’ of the clause in these examples of language-in-action in sport (Caldwell 2025; Doran et al. 2021), the lexis (ellipted commands, naming, confirmations, repetition, etc.) is recognisable and meaningful. It has been important to exclusively turn to the meaning making potential of the player’s voice quality in this paper. However, what is being said vis-à-vis that voice quality is critical for future studies. Recent work in intermodal convergence (Ngo et al. 2022) is particularly relevant here. For example, there is clear interpersonal resonance between a voice quality that signifies loudness, speed, tension, intensification (and so on), with an interpersonal discourse semantics of ellipted, repeated commands, mostly consisting of naming and confirmations, which in interpersonal terms, construes high force, strong authorial endorsement, and the like. This is most evident in the grabbing voice, where the crescendo of long syllable duration resonates with a repetition in lexis. This in turn presents not only an interpersonal semiotic resonance (Ngo et al. 2022) across the lexis and voice quality, but it also presents an intensifying prosody (Martin and White 2005) across the entire rhythmic phrase that is realised by both lexis and voice quality. Future research might therefore consider whether there are instances in language-in-action in sport where there is not convergence, where the voice quality and lexis do not resonate. We could also consider whether such patterns co-articulate with gestures and on-field actions that increase (or crescendo) in their force. Following Doran et al. (2025), this ultimately points to a focus on the division of semiotic labour in sport where action is the main ‘thing’ going on and language is dependent on it (what van Leeuwen [2025] calls ‘para-actional’ language).

The third and final topic follows in the work of Caldwell (2014a, 2014b, 2022), and his call for a more intersubjective and material reading of sound, in line with the seminal work of Schafer on birdsong (1977) and De Nora’s (2000) reading of sound as a socializing agent. Drawing on the work of Stenglin and the semiotics of space (Martin and Stenglin 2006; Stenglin 2004, 2008), Caldwell argues that alongside experiential readings of vocal sounds as indexical or affectual (where meaning is essentially attributed to the experiential state of the producer of the sound), we need to also conceptualize sound as a materiality that has particular semiotic affordances to/for its recipients. This kind of intersubjective material reading has been taken up throughout this paper, especially in the assignment of the meaning potentials ‘grabber’ and ‘tapper’. Whilst one can assign ‘grabbing’ and ‘tapping’ to the quality of the vocal sound in and of itself, or the identity of the producer, or even their affectual state, the terms also clearly invoke the sense of touch, from person to person, or person to object. The sound ‘grabs’ their teammate; the sound ‘taps’ their teammate. This highlights their function well. These vocal sounds, in the context of sport, and especially in the context of calling for the ball, are not only markers of identify or affect; they are physical, material events that ‘hit’ their teammates, and pull them into a particular kind of action. The language-in-action analysed in this paper is and means tense, urgent, belligerent, loud and so on by virtue of the physical (experiential) force required to produce those sounds. Sound is a material force; an invisible egressive airstream that literally ‘hits’ its addressee. The player in this study used his vocal sound waves to ‘grab’ and ‘tap’ his teammate in an attempt to receive the ball. Language -in-action in sport reminds us that the ‘the wall of sound’ is not only metaphorical; sound is a material phenomenon, whose communicative impact in sport is only beginning to be explored and understood.

Funding source: This work was supported by the Australian Government Higher Education Participation and Partnerships Program (HEPPP) Specified National Project titled Accelerating Indigenous Higher Education (grant number ED16/011536).

Award Identifier / Grant number: Not applicable

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges UniSA College for their support in receiving the funding for this project, and the South Australian Aboriginal Sports Training Association (SASSTA), including its coaching and training staff, as well as the students who participated in the project. Special thanks are also extended to the key members of the research project: Dr. Nayia Cominos and Ms. Katie Gloede.

-

Research ethics: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol number 0000035316) and the Department for Education, South Australia (approval number DECD CS/16/00067-1.17).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in the study.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Australian Government Higher Education Participation and Partnerships Program (HEPPP) Specified National Project titled “Accelerating Indigenous Higher Education” (grant number ED16/011536).

-

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ariztimuño, Lilian I. 2025. How do we communicate emotions in spoken language? Modelling affectual voice qualities in storytelling. Journal of World Languages. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0041.Search in Google Scholar

Arnfield, Simon, Peter Roach, Jane Setter, Peter Greasley & Dave Horton. 1995. Emotional stress and speech tempo variation. In Proceedings of the ESCA-NATO workshop on speech under stress, 13–15. Lisbon: Portugal.Search in Google Scholar

Berger, Thomas, Michael Fuchs, Sebastian Dippold, Syliva Meuret, Viet Zebralla, Maryam Yahiaoui-Doktor, et al.. 2020. Standardization and feasibility of voice range profile measures in epidemiological studies. Journal of Voice 36(1). 142.e9–142.e20.10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.04.014Search in Google Scholar

Boersma, Paul & David Weenik. 2008. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (version 6.4.41). http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/ (accessed 23 April 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Caldwell, David. 2020. Sounds of the game: An interpersonal discourse analysis of ‘on field’ language in sports media. Discourse, Context & Media 33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100363.Search in Google Scholar

Caldwell, David. 2014a. The interpersonal voice: Applying appraisal to the rap and sung voice. Social Semiotics 24(1). 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2013.827357.Search in Google Scholar

Caldwell, David. 2014b. A comparative analysis of rapping and singing: Perspectives from systemic phonology, social semiotics and music studies. In Wendy L. Bowcher & Bradley A. Smith (eds.), Systemic phonology: Recent studies in English, 271–299. London: Equinox.Search in Google Scholar

Caldwell, David. 2022. A hip-hop battle: Describing sound in the contested academy. In David Caldwell, John S. Knox & James R. Martin (eds.), Appliable linguistics and social semiotics: Developing theory from practice, 67–83. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781350109322.ch-4Search in Google Scholar

Caldwell, David. 2025. Mic’d up and mentoring: A discourse analysis of mediatised coach discourse. In Andrew S. Ross, David Caldwell & Yaegan J. Doran (eds.), Language in sport: Real-time talk in training and games, 115–140. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003458661-7Search in Google Scholar

Caldwell, David, John Walsh, Elaine Vine & Jon Jureidini (eds.). 2016. The discourse of sport: Analyses from social linguistics. New York, NY: Routledge.10.4324/9781315644974Search in Google Scholar

Cambridge University Press & Assessment. 2025. Cambridge online thesaurus. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/thesaurus/fast (accessed 15 August 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Cominos, Nayia, David Caldwell & Katie Gloede. 2019. Brotherhood and belonging: Mapping the on-field identities of Aboriginal youth. In Sadia Habib & Michael R. M. Ward (eds.), Youth, place and theories of belonging, 92–109. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203712412-8Search in Google Scholar

DeNora, Tia. 2000. Music in everyday life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511489433Search in Google Scholar

Doran, Yaegan J., David Caldwell & Andrews S. Ross. 2021. Language in action: Sport, mode and the division of semiotic labour. Language, Context and Text: The Social Semiotics Forum 3(2). 274–301.10.1075/langct.20009.dorSearch in Google Scholar

Doran, Yaegan J., David Caldwell & Andrew Ross. 2025. Language in sport: Wherefore and where to? In Andrew S. Ross, David Caldwell & Yaegan J. Doran (eds.), Language in sport: Real-time talk in training and games, 238–236. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003458661-12Search in Google Scholar

File, Kieran. 2025. Discursively regulating driver emotions during live formula 1 racing events: An emotion regulation interpretation of time-gap information messages. In Andrew S. Ross, David Caldwell & Yaegan J. Doran (eds.), Language in sport: Real-time talk in training and games, 34–54. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003458661-3Search in Google Scholar

File, Kieran, David Caldwell & Lindsey Meân. 2026. The Bloomsbury handbook of language and sport. London: Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1985. An introduction to functional grammar. London: Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 2004. An introduction to functional grammar, 3rd edn. London: Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, JamesR. 1992. English text: System and structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.59Search in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. & Maree Stenglin. 2006. Materializing reconciliation: Negotiating difference in a transcolonial exhibition. In Terry D. Royce & Wendy L. Bowcher (eds.), New directions in the analysis of multimodal discourse, 215–238. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. & Peter R. R. White. 2005. The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.Search in Google Scholar

Ngo, Thu, Sue Hood, James R. Martin, Claire Painter, Bradley A. Smith & Michelle Zappavigna. 2022. Modelling paralanguage using systemic functional semiotics: Theory and application. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781350074934Search in Google Scholar

Ross, Andrew S., David Caldwell & Yaegan J. Doran (eds.). 2025. Language in sport: Real-time talk in training and games. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003458661Search in Google Scholar

Rossing, Thomas D. 2007. Springer handbook of acoustics. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-0-387-30425-0Search in Google Scholar

Schafer, Murray R. 1977. The tuning of the world. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.Search in Google Scholar

Stavridou, Anastasia. 2025. The “other” side of leadership: Unpacking leadership and followership performance through linguistics in a university basketball team. In Andrew S. Ross, David Caldwell & Yaegan J. Doran (eds.), Language in sport: Real-time talk in training and games, 12–34. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003458661-2Search in Google Scholar

Stenglin, Maree. 2004. Packaging curiosities: Towards a grammar of three-dimensional space. Sydney: The University of Sydney PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Stenglin, Maree. 2008. Binding: A resource for exploring interpersonal meaning in three dimensional space. Social Semiotics 18(4). 425–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330802469904.Search in Google Scholar

Tauroza, Steve & Desmond Allison. 1990. Speech rates in British English. Applied Linguistics 11(1). 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/11.1.90.Search in Google Scholar

Thompson, Geoff & Susan Hunston. 2000. Evaluation: An introduction. In Susan Hunston & Geoff Thompson (eds.), Evaluation in text: Authorial stance and the construction of discourses, 1–27. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198238546.003.0001Search in Google Scholar

Van Leeuwen, Theo. 1999. Speech, music, sound. London: Bloomsbury.10.1007/978-1-349-27700-1Search in Google Scholar

Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2005. Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203647028Search in Google Scholar

Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2009. Parametric systems: The case of voice quality. In Carey Jewitt (ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis, 68–77. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2025. Three sound bites: Avenues for research in the study of speech, music, and other sounds. Journal of World Languages. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0037.Search in Google Scholar

Walsh, John, David Caldwell & Jon Jureidini. 2024. Evaluative language in sports: Crowds, coaches and commentators. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781351060998Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, Nick. 2025. Ambiguous person reference in coach talk: How New Zealand rugby coaches mediate the directness of their player-directed speech through the use of pronouns, personal names, and familiar address terms. In Andrew S. Ross, David Caldwell & Yaegan J. Doran (eds.), Language in sport: Real-time talk in training and games, 94–115. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003458661-6Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.