Abstract

This paper presents a metalanguage for teachers to teach about the functions of music and sound effects in fictional media and how it contributes to the understanding of film plot. This is part of a larger study from a Systemic Functional Semiotics (SFS) perspective examining the potential of sound in constructing key literary elements such as character, plot, setting and broader literary and cinematic effects. The metalanguage is developed by conceptualising three metafunctions of cinematic sounds (i.e. ideational, interpersonal, and textual) based on the analysis of the film data selected for this study. This paper starts with inventorising observable sounds we can hear in the films, followed by a description of sound qualities as the “signifier” and their meaning potential as the “signified”. It provides evidence that in terms of plot construction, cinematic sounds can represent a narrative story arc, realise events and properties of events. The metalanguage as well as the modelling of the metafunctions of film sound in the current study also provides multimodality researchers with a tool to analyse multimodal texts where sound is a key component such as films, video clips, video games, and other forms of multimodal digital texts.

1 Introduction: film as literature in language arts and literacy curricula

Literature is a core element in Language arts and Literacy curricula around the world because of its tremendous role in children’s development. Through literature, children not only expand their personal experience and learn about the society’s aesthetic, ethical and moral values, they also develop their language and literacy skills. The 21st century Language Arts curricula (including the Australian Curriculum: English, British Colombia curriculum, the U.S.A common core standard document, the New Zealand curriculum and Singapore curriculum) requires literature teaching to include texts that are multimodal, dynamic, and digital along with traditional printed forms (ACARA 2024; British-Colombia-Government 2019; Cope and Kalantzis 2000; Department-for-Education-England 2014; New-Zealand-Ministry-of-Education 2020; Singapore-MOE 2019; Stotsky 2013). Film is one such form of multimodal digital literature that has now been explicitly prescribed in the many Language Arts curricula. For example in the Australian Curriculum: English:

Students interpret, appreciate, evaluate and create literary texts such as short stories, novels, poetry, plays, films and multimodal texts in spoken and digital/online forms. (ACARA 2024, emphasis added)

Unlike written literature where language is the only mode of meaning making, filmic literature is constructed from multiple sound and visual resources in addition to language. While visual resources tend to be more familiar with teachers, sound is less commonly discussed. From most audience’s perspective, sound exists in films by default, and they only notice it when it is extremely poor quality or is absent. This is due to the vision being psychologically more dominant to human than the audio channel (Audissino 2017). Nonetheless, sound plays a significant role in the multimodal story-telling work of film. Film studies researchers have identified multiple functions of different types of film sounds (Audissino 2017; Manvell and Huntley 1957, 1975; Murch 1990), summarised in the statement below by internationally renowned film sound designer and editor, Walter Murch (1990):

Dialogue is usually dominant and intellectual, music is usually supportive and emotional, sound effects are usually information. (Murch 1990: 298)

The sound design job is an aural artistic one which involves a complicated and highly challenging process from interpreting the film script and understanding the director’s intentions to coordinating with the visual designers to create sounds that contribute to the overall story-telling of the film (Mancini 1985).

Film sound refers to speech sound in dialogue, music and sound effects (Chion 2009). Speech sound refers to the vocal sound proper in dialogue (Kracauer 1985: 126). Speech sound involving intonation and voice quality is essential for understanding dialogue or the main language channel of film. While intonation and voice quality have been widely oriented toward educational linguistics fields which directly inform the teaching of film in the Language Arts curriculum, there is a paucity of materials to support teachers’ teaching of film sounds as literary devices. One well-known exception is Reading in the Dark: Using Film as a Tool in the English Classroom by John Golden (2001), which focuses on film sounds’ relation to the diegesis of the film (i.e. diegetic, non-diegetic, and internal diegetic); however, there is no explication of how sound makes meanings and literary meanings. This is largely due to the difficulties in translating technical linguistics and musicology knowledge into language arts metalanguage that all teachers and students can use.

This paper introduces a metalanguage for describing the properties of music and sound effects in relation to their meaning potential in constructing plot as a key literature element. This is part of a larger study examining the potential of sound in constructing three key literary elements: character, plot and setting, as well as their literary and cinematic effects from the perspective of Systemic Functional Semiotics (SFS hereafter) (Ngo and Unsworth 2026). The metalanguage is developed through SFS work conceptualising three metafunctions for cinematic sounds (i.e. ideational, interpersonal, and textual) based on the analysis of film data selected for this study. The metalanguage is meant to be usable by teachers and students regardless of their musicology training background. The paper starts with reviewing approaches to film sound studies and explaining the Systemic Functional Semiotic approach the study adopts in developing a model of cinematic sound. The body of the paper is dedicated to presenting the SFS modelling of film sounds from which the metalanguage is developed. The paper concludes with discussion of the potential application of the metalanguage of film sounds in Language Arts education as well as in multimodality research.

2 The systemic functional semiotic approach to film sound studies

Film studies and musicology have developed a rich means of understanding the cinematic effects of film music and how it is constructed. However, to engage with this and associate cinematic effects with the literary functions in the classroom requires language arts teachers and students to have a shared knowledge of musicology and its technical language to describe any given musical phenomenon and to make inferences about its literary meaning. For example, to describe the musical construction of the dark fantasy theme in the End-Credit theme song[1] of the Coraline film (Selick 2009), musicologists would describe the music piece using technical language such as “minor second”, “tritone”, “dissonance”, and “chromatic” as in the AI generated description presented in Example (1).

| In the End Credits theme of Coraline, the dark fantasy atmosphere is crafted through tightly clustered chords sung by the children’s choir, where notes a minor second or tritone apart create intense, unsettling dissonance. This vocal layering is complemented by chromatic instrumental lines – especially from accordion, harmonium, and strings – that slide through half steps and unusual accidentals, adding an eerie, otherworldly texture. Together, these elements weave a haunting soundscape that perfectly captures the film’s blend of whimsy and creeping unease. |

This kind of description poses a great challenge to teachers and students who are not trained in musicology. In a class where there is a mixture of students with and without a music training background, even if the teacher is trained in music, it is still difficult to deploy musicologist’s description of the composition of music for a particular literary effect without leaving untrained students behind.

To mitigate this problem, this study adopts a SFS approach to describe film sounds. This approach combines Kress and van Leeuwen’s Social Semiotics approach to studying the “grammar” of non-language artefacts and activities such as visual image and movements (Kress and van Leeuwen 2021; van Leeuwen 2005) with the “systemic” component of Halliday’s Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL hereafter) (Halliday 1978). In terms of SFL, Halliday (e.g. 1978) argues that language has the potential to make three kinds of meanings (ideational, interpersonal, and textual) which he called the three metafunctions. The ideational function describes the construal of what is happening and the participants and circumstances involved in this happening. The interpersonal function is concerned with how interactants relate to each other in terms of communicative functions and attitudes. The textual function of language has to do with how language is used to weave ideas together to create a cohesive text.

Analogously, as a semiotic resource, this paper argues that film sound also has the potential to make three kinds of meanings. However, the kind of meaning film sound makes can be induced in the specific contexts it is used (usually provided by the accompanying image or speech) and does not have pre-given meanings.

Like language or any other semiotic resources, film sound can make meanings because it is a union of a “signifier” (i.e. observable sonic qualities or expression) and “signified” (i.e. meaning potential or content). Van Leeuwen (2005) explains that semiotic resources are an assembly of “signifiers” and “signifieds” but with a very considerate definition of the signified as both ‘theoretical and actual potential’ rather than fixed pre-given meanings:

Resources are signifiers, observable actions and objects that have been drawn into the domain of communication and that have a theoretical semiotic potential constituted by all their past uses and all the potential uses; and actual semiotic potential constituted by those past uses that are known to and considered relevant by the users of the resource, and by such potential uses as might be uncovered by the users on the basis of their specific needs or interest. (van Leeuwen 2005: 4, emphasis in original)

Accordingly, to develop a social semiotic understanding of film sounds, the first task of a semiotician is to catalogue “observable” sounds and their “observable” properties or qualities that are used in films. This is followed by gathering evidence of their theoretical use in relevant research and their actual use documented in literature. As the “specific interest” of this study is to “uncover” the literary meaning potential of film sounds, this step is followed by a close examination of film sounds in a selection of film data to understand the “actual” use of sounds in the data. For example, about 4:30 min into the film Coraline, a music text occurs that accompanies Coraline’s running as depicted in Figure 1.

Music text accompanying the running scene.

The observable qualities of this music text include a fast pace, rhythmic strong beats in the background matching the movement of the character, and two sustained high notes in the foreground in the middle of the running scene. The music text starts with a medium pitch then peaks with a high pitch before finishing off with a drop in pitch aligning with the end of Coraline’s running phase. The pitch composition of this music text is similar to that of a narrative story arc with orientation (medium pitch), climax (sustained high and long notes) and resolution (drop in pitch). The music sounds tense, loud and clear overall but there is vibration during the sustained high and long notes during the pitch climax. The music qualities described here for our purposes are the “signifier”.

Film studies literature has long been discussing the representation functions of music (Chion 2009; Murch 1990). In the scene from the Coraline film exemplified here, the use of such music qualities could be to mimic the character’s manner of activity (running fast) (in terms of the ideational metafunction) and/or to represent the character’s emotion (i.e. the anxiety – the interpersonal metafunction). The potential use of certain music qualities in a particular context is what we will describe as the “signified”. Both the ideational and interpersonal meanings realised by film music in this case contribute to character development of the main character, Coraline, with ideational meanings describing the character’s action and interpersonal meanings describing the character’s interiority.

Combining the Social Semiotic approach with the “systemic” aspect of SFL, the study considers one set of film sound qualities in relations to other sets in a system of possible meanings made available by the sound qualities.

The following section explicates the Systemic Functional Semiotic conceptualisation of the ideational meaning potential of film sound from which the metalanguage for describing sound and its functions is developed. The section starts with classifying the sounds we can hear, followed by a description of the potential of certain sets of sound qualities in realising ideational meanings based on the analysis of the ‘actual’ use of sound in the dataset of the study. The dataset includes five children’s literature filmic adaptations: Coraline (Selick 2009), Wonder (Chbosky 2017), Anne of Green Gables (Sullivan 1985), The Polar Express (Zemeckis 2004), and The Gruffalo (Lang and Schub 2009) as well as masterpieces of film: The Godfather (Coppola 1972) and Titanic (Cameron 1997). All of these films have been nominated for at least one prestigious award.

3 Inventorizing film sounds

The first exercise of a social semiotician when building a system network of the meaning potential of a particular material is “[…] inventorizing the different material articulations and permutations a given semiotic resource allows” (van Leeuwen 2005: 4) as the basis for the next step involving “describing its semiotic potential, describing the kinds of meanings it affords” (van Leeuwen 2005: 4). The outcome of this inventorizing job is a set of metalanguage allowing educators to identify and ‘call out’ different types of sounds that are available in films.

In a distinguishable unit of film sound (a soundtrack), observable cinematic sounds can be categorised according to (1) their sources, (2) their relations with the story world or diegesis, (3) their relations with visual displayed on the screen, and (4) their hierarchy.

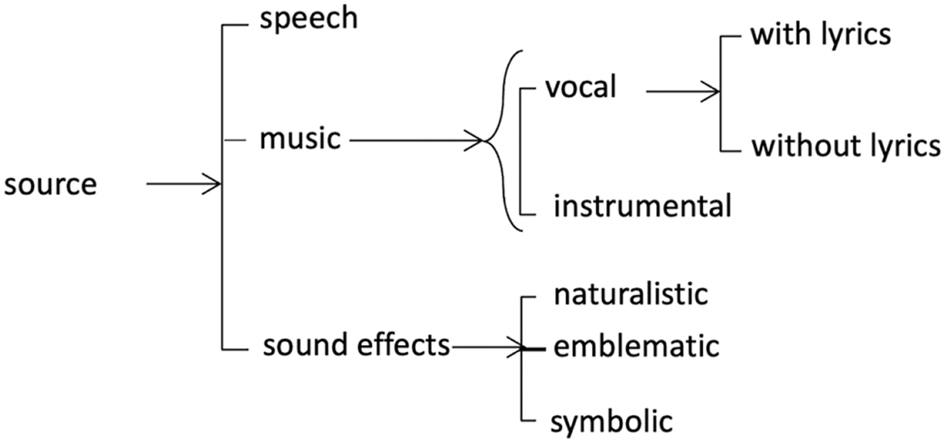

Based on their sources, film sounds consist of speech sound, music, and sound effects (Bordwell et al. 2018; Gorbman 1987; Manvell and Huntley 1957; Phillips 2009). Speech sounds refer to the vocalisation of dialogue, voice over and narration, where intonation and voice quality play a major part (e.g. Ariztimuño 2025). This paper is concerned with the other sources of sound, such as music and sound effects.

Music refers short or extended melodious phrases of sounds. The long extended melodious connected phrases can be vocal and/or instrumental. A theme song, such as the “Doll making”[2] in the Opening Credit of the Coraline film, is an example of an extended music text composed of both vocal and instrumental music. Sometimes, vocal music involves singing with lyrics or humming without lyrics.[3] Humming is often used for interpersonal meaning, to create an ambience or mood of the scene. In a long film, sometimes the film makers give each main character a musical theme in the form of a soundtrack called a leitmotif. In the Coraline movie, for example, a character called the Other Mother is closely associated with a soundtrack associated with “making dolls”. In such cases, music texts function as cohesive devices in films.

Sound effects or noise can be categorised as naturalistic, emblematic and symbolic sounds. Examples of naturalistic sounds from the Coraline film include metal clicking sounds of the wheels on a mask of character called (Figure 2), the squeaky sound of metal hinges as a door opens or closes, Coraline’s footsteps as she walks in the street or the character-Cat’s rubbing against the window.

Sound effect-the metal clicking sounds of Wybie’s mask wheels.

Examples of emblematic noise include those that are used for a designated meaning in a culture or community such as the sound of siren urging people to give way, the sound of school bells signalling the beginning or end of class time or the sound of the horn blowing signalling the start of a battle. Naturalistic sounds if composed with exaggeration can become symbolic such as the use of loud heartbeat sound representing a character’s anxiety. This example can be seen a scene from a Tom and Jerry cartoon (Figure 3).[4]

Heartbeat in Tom and Jerry.

The inventory of cinematic sounds based on its sources are presented in Figure 4. The square brackets indicate the either/or relation; e.g. a source of sound can either be speech, music or sound effects. The curly bracket outside of the square bracket indicates the “either or both” options. This means, music can either be vocal or instrumental or both.

Inventory of cinematic sound based on its source.

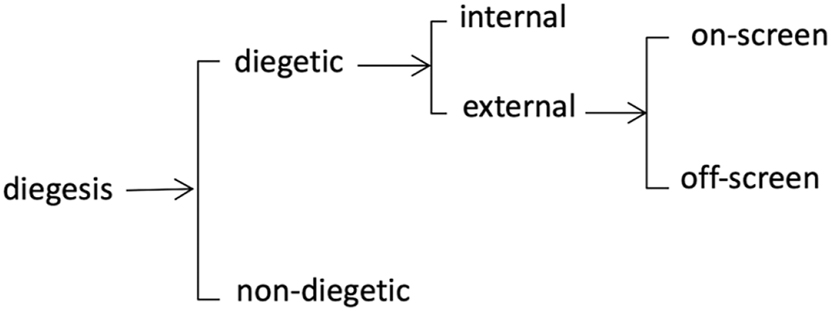

Based on their relations with the story world or diegesis, sounds can also be described as being either diegetic or non-diegetic. Diegetic sounds are the ones that characters make or hear in the world, or those that are part of the physical and social setting of the story world. Diegetic sounds can be thought of as internal and external. Internal diegetic sounds are characters’ internal thoughts that are projected for the viewers to hear. Figure 5 provides an example from Coraline, of a scene when Coraline’s internal thoughts telling herself to be ‘strong’ when facing the witch disguised as her Other Mother are projected out loud.

Internal diegetic sound.

External diegetic sounds come from any source that the characters can hear. At the very beginning of the film Coraline, for example, a man in Coraline’s neighbourhood is heard counting as he is exercising, a truck is heard beeping as it is reversing and a car is heard honking as it signals its appearance when turning into a corner (Figure 6). These sounds are diegetic because they belong to the social and physical setting of the story world.

Diegetic sounds from the story world.

External diegetic sounds can be seen from the perspective of their relations to the visual displayed on the screen. When sounds and their visual sources are displayed on the screen, the sounds are referred to as on-screen. In contrast, off screen sounds refer to those whose sources are not displayed on the screen. An example of external diegetic off-screen sound in the Coraline movie involves Coraline and Wybie hearing Wybie’s grandma calling his name ‘Wyborn’, but visual image of his grandma is not displayed on the screen. Figure 7 presents this scene.

Off-screen sound (source of diegetic sound not displayed on the screen).

Non-diegetic sounds are those outside of the story world being super-imposed on the scene for different effects, such as creating the continuity between shots, establishing mood for a scene and characterising a character, etc. The music text superimposed onto films, such as Coraline’s running scene in Figure 1, is an example of non-diegetic sound. A system network of the inventory of cinematic sounds based on their relation to the story world or diegesis is presented in Figure 8.

Inventory of cinematic sound based on diegesis.

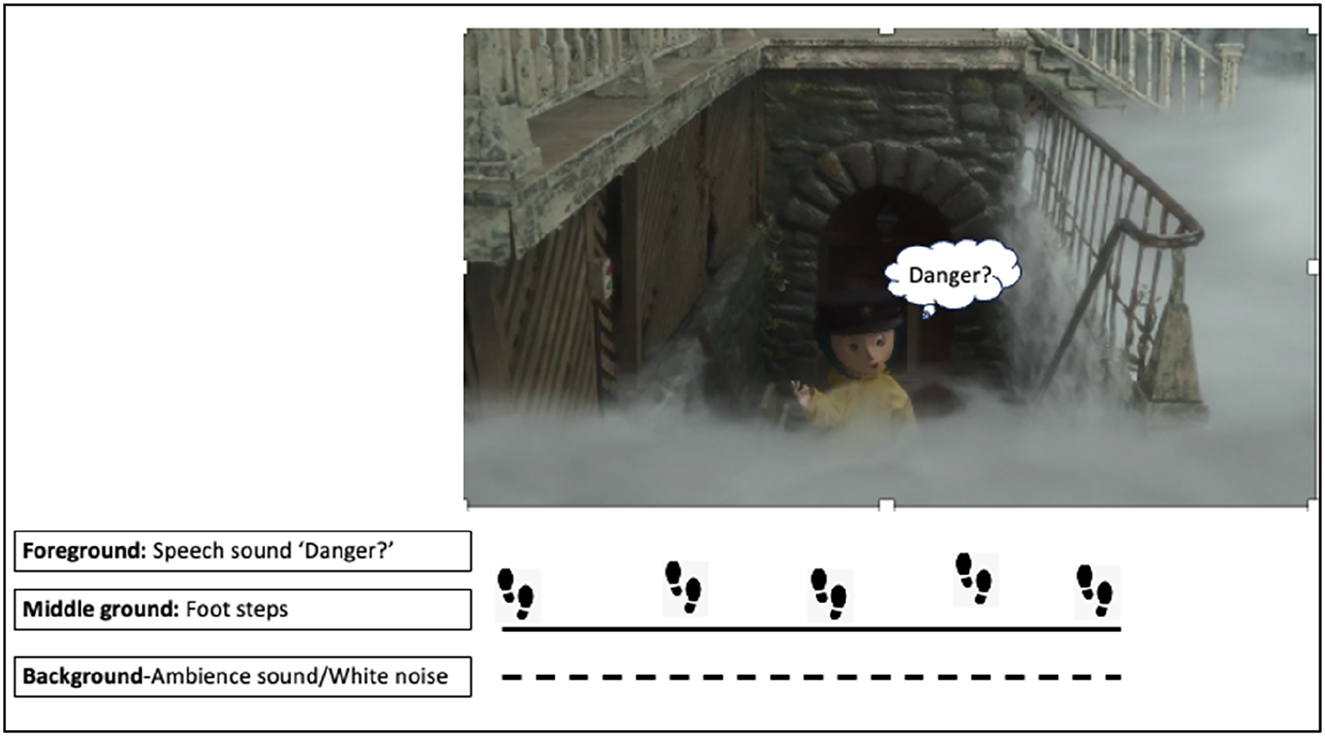

Lastly, sounds can be distinguished in terms of their hierarchy from the perspective of the listeners (van Leeuwen 1999: 23). The most prominent ones we can call ‘foreground’ sounds. These are created to make the listener react by identifying with them, paying attention to them or responding to them. In a film scene where there are all three sound sources (i.e. speech, music and sound effect), speech sounds usually take the foreground position (unless speech is used as ambient sound in the background) and the other sound sources subdue to it. Middle ground sounds (often called ‘ground’) are those that belong to the social world of the listener, but ones that they do not need to respond to. Van Leeuwen (1999) compares these sounds to familiar faces we see every day but only notice them when they are no longer present. Background sounds are those that belong to the physical world of the listener, like people in a crowded street who we do not need to react to if nothing unusual happens. In everyday context, we can hear these levels of sounds everywhere. Imagine sitting in a quiet café with a friend where a soft gentle piece of music is playing. The foreground sound is the sound of our conversation with the friend. The soft gentle piece of music is the middle ground sound and the waiters’ footsteps as they walk around is the background sound.

The hierarchy of sounds in films can be very dynamic, depending on the film maker’s intention in terms of how they wish to guide the audience’s perspective and make them hear and react. Speech sound can shift to become background sound if it is used as noises in a physical setting, for example. Indeed at time, there is only one layer of sound, which would typically be foreground sound such as speech sound. Similarly, the same source may produce a hierarchy of sound. When a scene only has music, for example, it can have one primary melody line (i.e. monophony – the foreground) or one melody line with accompaniment (i.e. homophony – foreground and middle ground) or two primary lines co-existing (i.e. polyphony). In each case, the melody line takes the foreground position.

Figure 9 presents a screenshot of a shot where Coraline walks up the stairs from her neighbour’s house. In this scene, Coraline wonders if she is in danger following a warning from her neighbour. In this shot, three layers of sound can be heard. In the background we can hear the white noise or ambience noise, which arises from the natural environment. In the middle ground is Coraline’s footsteps. In the foreground is Coraline’s speech sound as she asks herself ‘Danger?’

Representation of sound hierarchy.

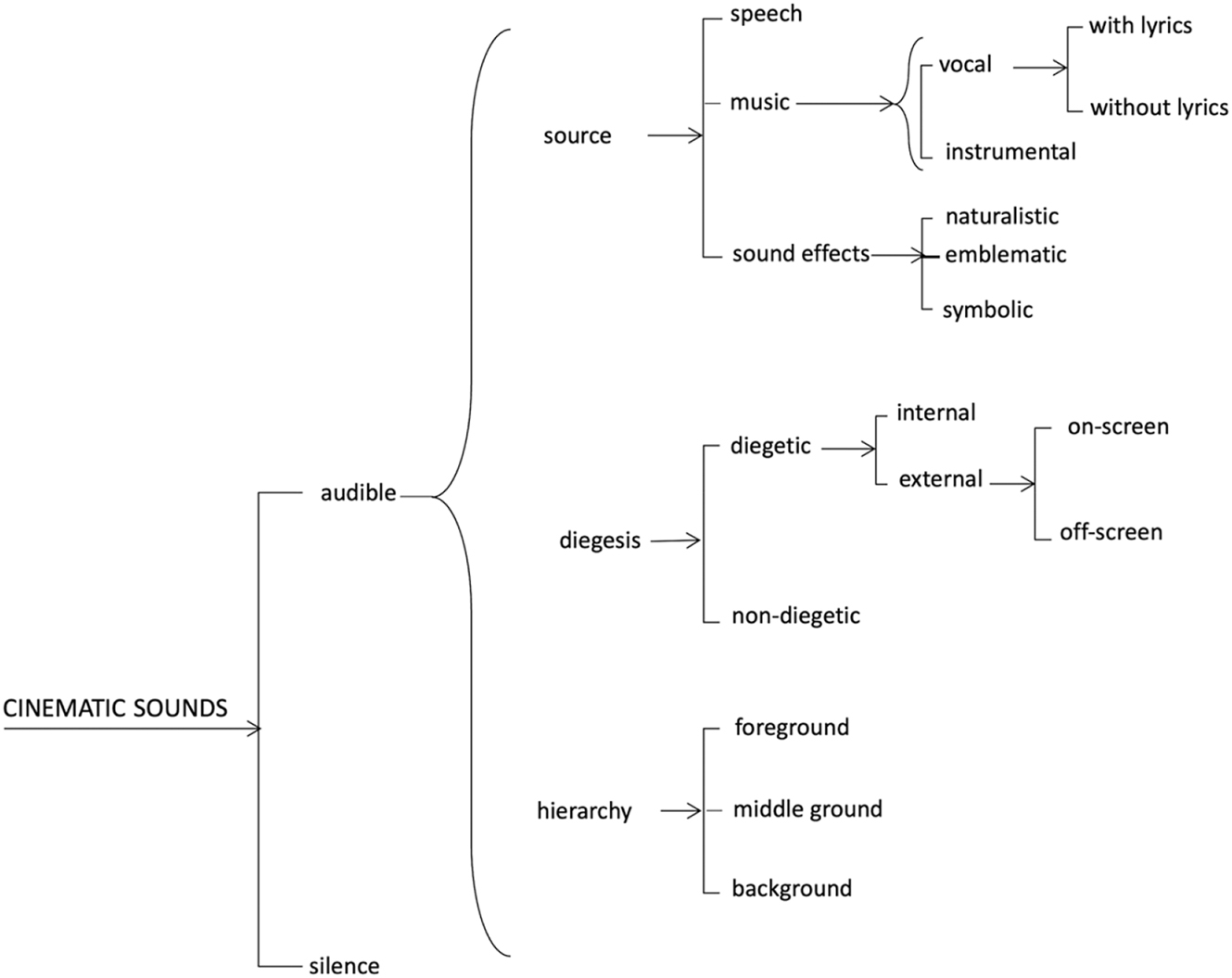

Figure 10 summarises the outcomes of the inventorisation of film sounds discussed in this section. In this network, we have included silence as a contrast to all of the choices described thus far. In film, silence is designed ‘sound’, just as much as other sound choices, and is often used to create suspense for thrilling effects.

The inventory of cinematic sounds.

The system network in Figure 3 distinguishes audible and non-audible sound (silence). The square bracket represents either/or options. The option of audible sound embraces three aspects of cinematic sounds: their source, relation to diegesis and hierarchy. The curly bracket indicates that all of these aspects happen simultaneously. In the language arts class, the teacher can use their knowledge of these choices to systematically pose specific ‘decoding’ questions to guide students’ hearing of different trains of sound.

4 Observable qualities of film sounds

To understand sound semiotics, we need to understand the qualities film sounds possess before associating them with their meaning potential. In other words, we are trying to describe the ‘signifier’ of the sonic semiotic resource through the ears of a (sound or music) listener rather than a musicologist. Four significant dimensions of film sounds constructing the ‘signifier’ are rhythm, melody, sound qualities (or timbre) and sound text structure.

4.1 Rhythm

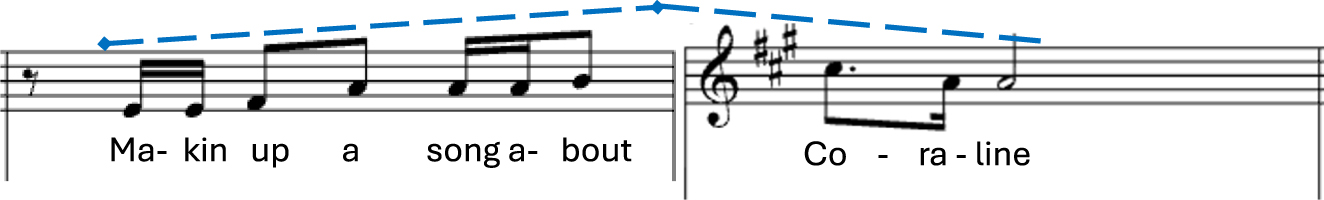

Rhythm is pervasive in sound perception (see van Leeuwen 2025). In a string of musical sound, for example, there is an alternation between stronger and weaker beats or a strong beat and a rest. In the Coraline film, when the Other Father sings a song about Coraline,[5] we can tap along on the marked (bold and italic) words/morpheme (which are the stronger beats) in his lyrics as in Example (2). The slashes in Example (2) marks the pair of stronger (ONE) and weaker beats (two) or a rest (∼).

| /Ma-king/ | up a/ | song a/ | -bout ∼/ | Co- ∼/ | raline./ |

| ONE two/ | ONE two/ | ONE two/ | ONE rest/ ONE rest/ two ONE. | ||

This kind of music or sound is called ‘measured’ sounds because it can be measured by the pattern of weaker/stronger beats. In text 1, this pattern is demarcated by two forward slashes (/-/), called a ‘measure’, analogous to a ‘foot’ in speech sound (see van Leeuwen 1999, 2025). Up to eight measures grouped together is called a sound phrase. The singing of the two lyric lines above are two music phrases.

Measured sounds are opposed to ‘non-measured’ sounds, where there is not a clear rhythmic beat. An example of non-measured sound is the white noise in the background of the shot described in Figure 7. According to van Leeuwen (1999), unmeasured sounds are often associated with ‘non-human’ phenomenon. In the case of Figure 7 example, the unmeasured sound represents the sound of the natural environment.

4.2 Melody

When dealing with music in film, much of the sound that we perceive is melodious, where there is pitch movement through a string of sound. The Coraline song described above, for example, has low to moderate pitch, making it comfortable to sing and hear. The narrow range of pitch movement is also stable and predictable. The melody or trajectory of the pitch movement and range in the first two singing phrases of the song is presented in Figure 11 indicated by the blue line above the music notes.

Melody-pitch level, movement and range.

The notes within the string of sound can flow smoothly into each other such as in lullabies. An example of this from Coraline involves humming by one of the characters called the Other Mother in a scene where she is first introduced (Figure 12).[6]

Other Mother humming the melody of Doll making song.

In contrast to smoothness, notes in a melody can be short and separated, rather than smoothly running into each other. This occurs, for example, in the first phrase of the Coraline song noted in Figure 11. The kind of disjunctive articulation of notes often makes the singing sound bouncy, playful and childlike.

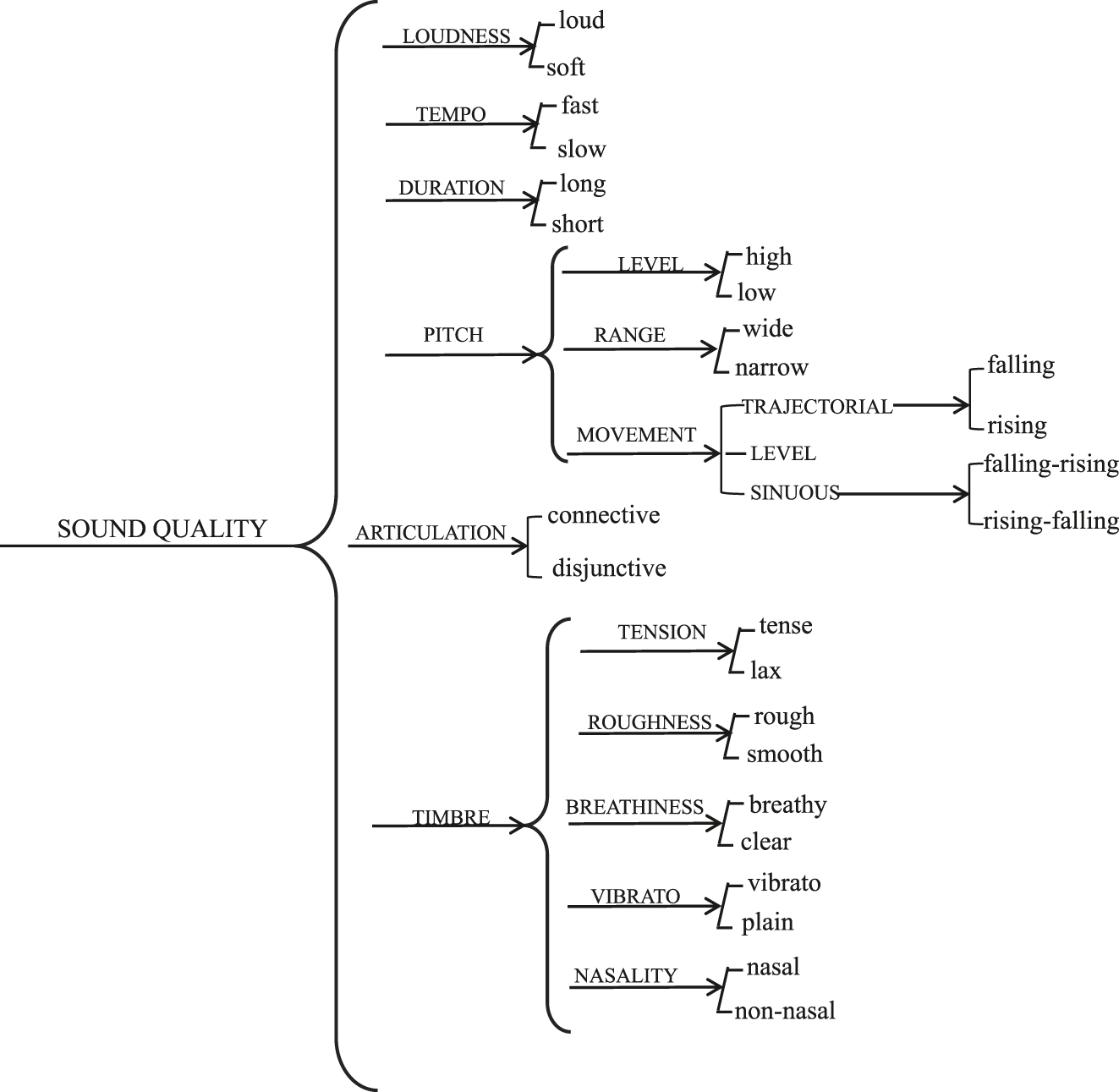

4.3 Sound qualities

Sound quality exists through a combination of wide range of sound parameters such as loudness, tempo, and tension, each of which occurs on a continuum as summarised in Figure 5. Sound qualities of a musical instrument are analogous to people’s fingerprints. They distinguish one instrument from another. The sound of a violin is obviously distinguishable from that of a cello with the former having high pitch and clear sound and the latter having lower pitch and deep sound. In this paper the sound quality framework extends on van Leeuwen’s (1999) sound parameters and Ngo et al.’s (2022) voice quality system. The tilted brackets in Figure 13 indicate the continuum a sound quality can range.

Sound quality (extended from van Leeuwen 1999: 152 and Ngo et al. 2022).

Added to van Leeuwen’s (1999) and Ngo et al.’s (2022) description of sound qualities are pitch movement features including trajectorial movement (either falling or rising), level, or sinuous (either falling then rising or rising then falling). In addition, sound quality is also seen through the dimension of articulation, whether the sound is smoothly connected (i.e. connective) or short, detached and separated (i.e. disjunctive). The sound quality framework in Figure 5 is appliable for all sources of film sounds.

Sound quality together with rhythm (or the patterns of beat and timing) and melody (the tune or musical line) arouses the viewer’s emotional reaction to what’s happening in the film. For example, tense sound, such as that which occurs during a human scream or the breaking squeal of a train as it pulls into the station, is often used to in turn make the viewer feel tense. Tense sound (which sounds tense to the ears) also helps film makers represent the character’s mood, feeling and the ambience of the scene. In the Godfather (Coppola 1972), Francis Ford Coppola raises tension during the iconic scene of Michael Corleone killing his opponents inside a restaurant, by including diegetic noise of a screeching braking train at the station next to the restaurant, in the seconds leading up to the killing.[7] The moment Michael pulls the trigger of his gun, the noise suddenly stops, releasing the tension, in a way that symbolises the release of tension represented by the shooting. Figure 14 shows the displayed image over which the train sound is played.

Tense noise used for representing character’s tension in The Godfather.

4.4 Sound text structure

Sound texts, especially music, typically have repetitive or progressive structures. The repetitive structure of the music text refers to the cyclic arrangement of music elements with either the same music phrase repeated or with small variation. An arrangement of notes in a phrase such as AABB-AABB is an example of a repetitive structure with repeated phrases. An arrangement such as AA′BB-AA′BB (with A′ is one octave higher than A) is an example of a repetitive structure with variation. Repetitive structures often represent continuous movements of characters. An example of such a structure is in the opening setting scene of the film The Gruffalo, (Figure 15), where the musical structure represents continuous walking of a Mouse character as it takes a stroll through a deep dark wood (as noted in the voiceover).

Repetitive music structure in the Mouse and the Fox scene.

In contrast, rather than cycling back through the same elements, progressive musical structures develop new musical patterns, and thus ‘moves forward’, for example by building to a dramatic point before declining. An example of this from The Gruffalo occurs in the opening title prelude, where it starts gently with a mother Squirrel leaving a log, looking for food. The music progressively builds in line with the movement of the squirrel, getting to the highest and loudest point through vibrating percussion when the squirrel reaches a tree with the film title The Gruffalo[8] (Figure 16).

Progressive music structure in the prelude of The Gruffalo.

This section has described common properties of cinematic sounds including rhythm, melody, quality, and structures. The language presented thus far for describing sound properties allows language arts teachers film analysts to describe the sound patterns and associate them with particular meaning potential to which literary meanings can be inferred. The following section explicates the potential ‘signified’ of film sounds and how they contribute to plot construction in films.

5 Film sounds for constructing plot

Plot is typically the driving thread of a film, constituting “what” the story is, comprising “significant events (or events that lead to consequences)” (Dibell 1988). From a film-studies perspective, a narrative story is composed of “a chain of events linked by cause and effect and occurring in time and space” (Bordwell et al. 2018: 73). The building blocks of a plot are thus “events” that are glued together via a logical relation.

Structurally, from the perspective of SFL, the plot of a story is built of story phases, constituting story stages (Martin and Rose 2008). For one of the most typical genres that organise films, a narrative, the stages include Orientation, Complication, Resolution, and (optional) Coda (Martin and Rose 2008). The Orientation of a narrative usually describes the setting and introduces the relevant characters that occur. The Complication provides a counter-expectant event (or events), typically involving conflicts, and progressively developing until a climax that is following by a Resolution. Film music texts with progressive structures can often represent this narrative arc due to the arrangement of their musical elements as described above.

While the configuration of stages is relatively stable within genres, the phases that occur within stages are more variable and text-specific. Common filmic narrative phases, building on those put forward by (Rose 2021) for written and spoken stories, include setting, character’s status quo, problem, event, reaction and result (Ngo and Unsworth 2026). Phases are the immediate environment or context in which filmic semiotic resources work to make meanings. From this perspective, then, to understand how film sound construct plot, we need to consider their meaning making in the unit of a phase.

As plot is concerned with “what is happening”, one of its major components is concerned with SFL’s ideational meaning – how experience is represented. In Martin and Rose’s (2007: 17) terms, this includes “what kinds of activities are undertaken, and how participants undertaking these activities are described and classified”.

In written stories, from the perspective of SFL, phases involve series of activities within what is called field at the register stratum (Doran and Martin 2021). Activities offer a dynamic perspective on a field, construing phenomena as goings-on or changes. In language, an example of an activity is a single clause (realising a single occurrence figure (Hao 2020), such as ‘Coraline exploring the neighbourhood’. Activities can be divided into a series of moments that constitute the broader activity, such as the following series of activities that represent moments of the previous activity: ‘Coraline cautiously steps out of her house’, ‘She looks around the neighbourhood’, ‘She steps down the stairs’, etc.

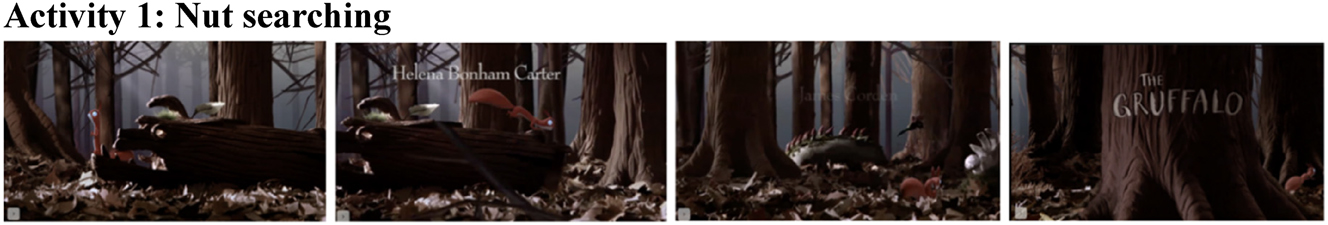

In filmic stories, activities and their logical relations can be realised by visual image, cinematographic techniques and language seen on the screen and heard in dialogue (Ngo and Unsworth 2026). As an example of visual sequences and their logical relations, let’s consider the character status quo phase in Orientation stage of The Gruffalo, that we saw above, where the Mother Squirrel leaves a log (that is shaped in the form of a monster’s head) and starts looking for food. In this instance, the phase is constructed by visual resources, music and sound effects.

The first activity in this phase is the Mother Squirrel’s search for a nut, involving four distinct moments (1) hopping out of the monster head log, (2) hopping from one log to another, (3) scratching on a leafy surface and (4) coming to a tree trunk on which the film title ‘The Gruffalo’ is superimposed upon (Figure 17). This momented activity is shown in Figure 17.

Sequence – looking for a nut.

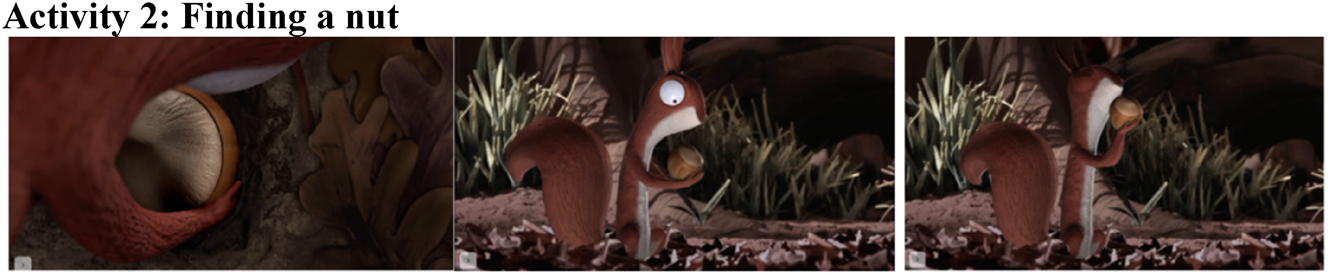

The second activity is when the squirrel eventually finds the nut, which involves three moments (1) spotting the nut, (2) picking up the nut and (3) sniffing the nut (Figure 18).

Activity 2 – finding a nut.

The logical relation between the moments of each activity in this filmic text is ‘sequential’ (i.e. ‘then’). It is realised through a ‘match cut’ editing technique in which the cinematic graphic elements from one frame matches the other, creating a sense of continuity (Bordwell et al. 2018). Within each frame, we can see the elements constructed through the activities themselves (such as the sniffing in the third frame), the participants that do them (the squirrel) and the circumstances in which they sit (the background).

In relation to sound as a key filmic resource, we can see music and sound effects typically mimic the pace and action of an activity, as well as creating a sense of a location, making what we see on the screen more lifelike and believable (Winokur and Holsinger 2001).

5.1 Naturalistic sound representing figures

Some naturalistic sound effects can represent an activity in themselves. At the beginning of the Coraline movie, for example, the audience can recognise the sound of a cat meowing or a car honking without the visual image of these figures not yet being on screen. Similarly, in the Gruffalo movie, the chirping and trilling sounds of the jungle can give hints to the audience about small birds due to their high pitch level. This is due to the affordances of the sound design instruments that allows them to mimic the properties of the represented sounds. In this case, film sound can work independently to make meaning.

5.2 Music and other sound effects representing properties of activities

In a similar way, music and other sound effects can represent properties of activities rather than whole activities themselves. When making sound effects, foley artists often use ordinary objects to simulate extraordinary sounds because they share the same properties. The sound of one character in the Coraline film biting on a chocolate beetle (shown in Figure 19) would have the same ‘crispiness’ property as when a foley artist crushes on crispy vegetables such as an iceberg lettuce.

Chewing on a beetle.

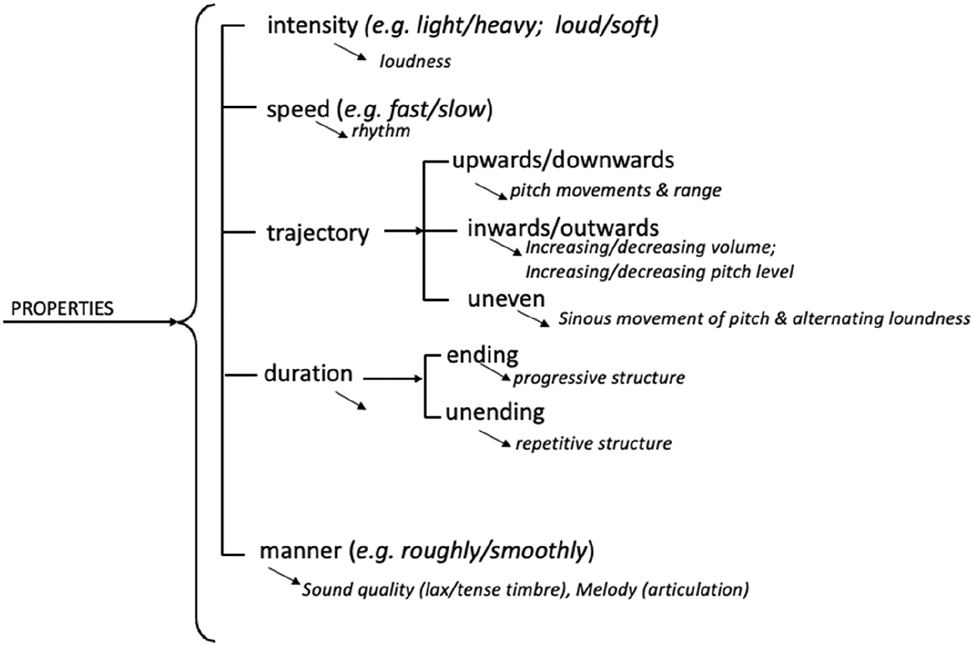

Film sound represents activities by mimicking their properties such as their speed, intensity, trajectory and duration and continuity. The affordances for music and sound effects that allow this are the observable properties described in Section 4: rhythm, melody (pitch movement and range), sound quality and composition. Activities, and their corresponding music and sound effects, can have rhythm and speed (fast/slow), intensity (hard/gentle), trajectory (downward/upward, leftward/rightward), ending/unending duration and continuity (connective/disjunctive). This aspect of ideational meaning potential of music and sound effect is presented in Figure 20, and in the following section we will overview each in turn.

Film sound representing properties of activities.

5.2.1 Intensity and speed of motion

Both sound effects and music can represent intensity and speed of the motion in activities. In the Coraline film, for example, the sound effect accompanying a cat walking versus the same cat hopping away is distinguished via loudness and rhythm. The walking action is softer in intensity (or loudness) and slower in tempo, while the hopping is by louder and faster.

5.2.2 Trajectory of motion

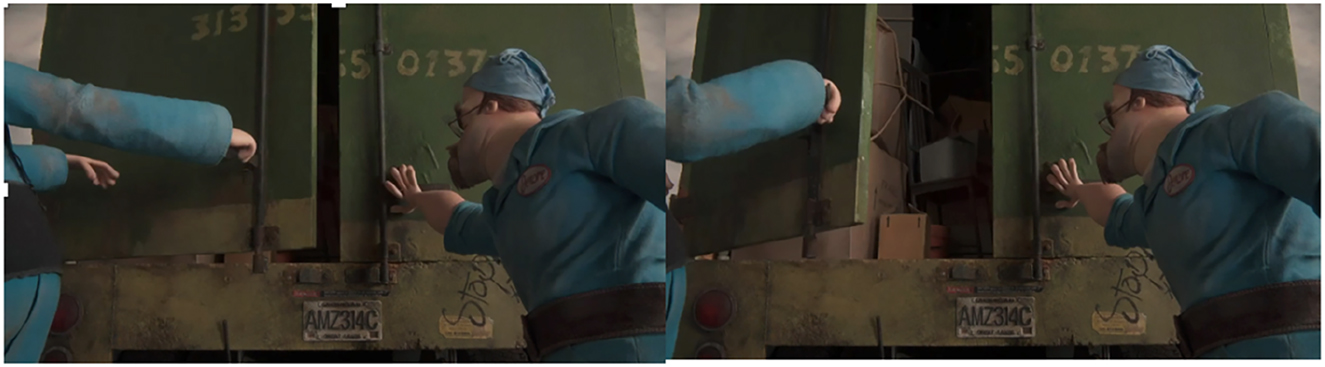

Sound effect and music can represent trajectory of motions through pitch movement, pitch range, variation in loudness and the combination of pitch movement and loudness. Visual motions that have a downwards trajectory, such as a drooping in posture by a removalist in Coraline, can be accompanied by a downward trajectory in the music, such as through a fall in pitch range, as occurs in this Coraline scene. Similarly, an outwards motion, such as the opening of a removalist truck doors in Coraline (Figure 21), can be accompanied by a sound that mimics this motion – in this case a ‘twang’ sound that moves from softer to louder (i.e. increasing volume) and from lower pitch to higher pitch (i.e. increasing pitch).

‘Twang’ sound effect representing outwards action trajectory.

5.2.3 Manner of motions

A motion can be smooth or rough in terms of manner. Music and sound effects can represent this through their sound qualities and melody articulation (see Section 4). A smooth manner is often presented by sound quality features such as connective articulation, soft volume and lax timbre while rough manner involves disruptive sound articulation, louder volume and tense timbre. The contrast can be seen in two different manners of the water flowing in The Gruffalo film. In one scene where the Mouse is taking a stroll by the stream (Figure 22A), the manner of water is gentle, represented by connective, soft and lax sound effects. In contrast, in the scene where the Mouse is confronted by the owl (Figure 22B), the manner of water flowing is vigorous, represented by disruptive, loud, fast and tense sound effects.

Differences in manner of motions.

The gentle water flowing in Figure 22A also represents a peaceful ambience of the setting while the vigorous water flowing in Figure 22B represents the tension in the atmosphere.

An activity can be described in terms of all of the features above. For example, the differences between Coraline’s walking upstairs can be compared with the removalist’s walking as they were carrying heavy furniture. Coraline’s walking has moderate intensity, moderate speed (two beats per phrase), a level trajectory and is smooth. The removalists’ walking, in contrast, is heavy (high intensity), moderately slow speed (one beat per phrase), a level trajectory and is smooth.

5.2.4 Duration of activity

Some series of activities have a repetitive pattern while others are progressive. Examples of activities with a repetitive pattern include the turning of the windmills and water flowing, where there is an indefiniteness in the continuity of the action. By contrast, events with a progressive structure typically have a beginning, peak and ending. The structure of repetitive and progressive music texts (see Section 4) can again mimic these two patterns of activities. The repetitive structure of the water flowing in The Gruffalo scene above represents the indefinite cycles of the water flowing activities. The music text accompanying the mother squirrel going out to look for nuts, encountering the owl and running home safely is an example of a progressive text structure. It starts with a gentle music sound, medium pitch and narrow pitch range before rising higher and louder with percussion before dropping in pitch and loudness. The gentle-peak-release progressive music text structure represents the definiteness of the duration of activities. Progressive music text structures can help realise a linear narrative arc. Naturalistic sound effects have the potential to realise figures while music and more indicative sound effects can only realise properties of motions (including speed, intensity, trajectory, and manner), and the relative duration of an activity sequence. These meanings together help construe kinds of activities occurring in a plot.

6 Conclusions

This paper has presented the conceptualisation of the semiotics of film sound from which the metalanguage for ‘talking’ about the functions of music and sound effects in fictional media and how it contributes to the understanding of film plot is developed. The paper detailed the semiotics conceptualisation procedure from inventorizing film sounds to describing sound qualities as signifiers and examining film data for the actual use of sounds to identify their meaning potential. Within the scope of this paper, only the ideational meaning potential related to activities has been discussed. Film sound can represent other ideational meanings, including the locale, time and temporal settings. And it of course can also realise interpersonal and textual meanings that are essential for understanding literary elements and effects.

Nonetheless, this paper has demonstrated the application of the SFS to developing a metalanguage for film sounds that can be used by language arts teachers. The distinctive advantage of a pedagogical SFS approach to film sound is that we can build a catalogue of ‘observable’ parameters of film sounds that are hearable by the lay observer, using accessible terminology such as ‘fast’, ‘loud’, ‘tense’, ‘high’, etc. Such a metalanguage can then support teachers to guide their students into targeted listening for film sounds, in ways that can connect with similar multimodal filmic understandings in the classroom, and ultimately comparable SFL-based metalanguages for monomodal reading and writing.

This research has extended on Bateman’s pioneer work on a SFS approach to the semiotics of films (Bateman 2007; Bateman and Schmidt 2012; Bateman and Wildfeuer 2016; Bateman et al. 2017). It has added sound to the existing body of research in SFS studies of film visual and editing, enabling film analysts to conduct a more comprehensive study on all participating semiotic resources in films.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability: The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

ACARA. 2024. Australian curriculum: English. https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/teacher-resources/understand-this-learning-area/english (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Audissino, Emilio. 2017. Film/music analysis: A film studies approach. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-61693-3Search in Google Scholar

Bateman, John A. 2007. Towards a grande paradigmatique of film: Christian Metz reloaded. Semiotica 167(1/4). 13–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem.2007.070.Search in Google Scholar

Bateman, John & Karl-Heinrich Schmidt. 2012. Multimodal film analysis: How films mean. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203128220Search in Google Scholar

Bateman, John A. & Janina Wildfeuer. 2016. Bringing together new perspectives of film text analysis. In Janina Wildfeuer & John A. Bateman (eds.), Film text analysis: New perspectives on the analysis of filmic meaning, 1–23. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Bateman, John, Janina Wildfeuer & Tuomo Hiippala. 2017. Multimodality: Foundations, research and analysis – A problem-oriented introduction. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110479898Search in Google Scholar

Bordwell, David, Kristin Thompson & Jeff Smith. 2018. Film art: An introduction, 12th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.Search in Google Scholar

British-Colombia-Government. 2019. British Colombia’s new curriculum-English language arts. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/english-language-arts (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Cameron, James. 1997. Titanic. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titanic_(1997_film) (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Chbosky, Stephen. 2017. Wonder. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wonder_(film) (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Chion, Michel. 2009. Film, a sound art. Translated by Claudia Gorbman. New York: Columbia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cope, Bill & Mary Kalantzis (eds.). 2000. Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Coppola, Francis F. 1972. The Godfather. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Godfather (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Department-for-Education-England. 2014. National curriculum in England: English programmes of study. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-english-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-english-programmes-of-study#key-stage-3 (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Dibell, Ansen. 1988. Plots: Elements of fiction writing. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest Books.Search in Google Scholar

Doran, Yaegan J. & James R. Martin. 2021. Field relations: Understanding scientific explanations. In Karl Maton, James R. Martin & Yaegan J. Doran (eds.), Teaching science: Knowledge, language, pedagogy, 105–133. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781351129282-7Search in Google Scholar

Golden, John. 2001. Reading in the dark: Using film as a tool in the English classroom. Illinois: National Councils of Teachers of English.Search in Google Scholar

Gorbman, Claudia. 1987. Unheard melodies: Narrative film music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1978. Language as a social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Armold.Search in Google Scholar

Hao, Jing. 2020. Analysing scientific discourse from a systemic functional linguistic perspective: A framework for exploring knowledge building in biology. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781351241052Search in Google Scholar

Kracauer, Siegfried. 1985. Dialogue and sound. In Elisabeth Weis & John Belton (eds.), Film sound: Theory and practice, 126–144. New York: Columbia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther & Theo van Leeuwen. 2021. Reading images: The grammar of visual design, 3rd edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003099857Search in Google Scholar

Lang, Max & Jakob Schuh. 2009. The Gruffalo. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Gruffalo_(film) (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Mancini, Mark. 1985. The sound designer. In Elisabeth Weis & John Belton (eds.), Film sound: Theory and practice, 361–368. New York: Comlumbia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Manvell, Roger & John Huntley. 1957. The technique of film music. London: Focal Press.Search in Google Scholar

Manvell, Roger & John Huntley. 1975. The technique of film music. Revised and enlarged by Richard Arnell & Peter Day. New York: Hastings House.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. & David Rose. 2007. Working with discourse: Meaning beyond the clause, 2nd edn. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. & David Rose. 2008. Genre relations: Mapping culture. London: Equinox.Search in Google Scholar

Murch, Walter. 1990. The sound designer. In Roy P. Madsen (ed.), Working cinema: Learning from the masters. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.Search in Google Scholar

New-Zealand-Ministry-of-Education. 2020. The New Zealand curriculum online: English. https://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/The-New-Zealand-Curriculum/English (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Ngo, Thu, Susan Hood, James R. Martin, Clare Painter, Bradley A. Smith & Michele Zappavigna. 2022. Modelling paralanguage from the perspective of systemic gunctional semiotics: Theory and application. London: Bloomsburry.Search in Google Scholar

Ngo, Thu & Len Unsworth. 2026. Digital multimodal adaptations of children’s literature: Semiotic analyses and classroom applications. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Phillips, William H. 2009. Film: An introduction, 4th edn. Boston: St. Martin’s.Search in Google Scholar

Rose, David. 2021. The baboon and the bee: Exploring register patterns across languages. In Yaegan J. Doran, James R. Martin & Giacomo Figueredo (eds.), Systemic functional language description: Making meaning matter, 273–306. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781351184533-9Search in Google Scholar

Selick, Henry. 2009. Coraline. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coraline_(film) (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Singapore-MOE. 2019. English language and literature. https://www.moe.gov.sg/education/syllabuses/english-language-and-literature (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Stotsky, Sandra. 2013. An English language arts curriculum framework for American public schools: A model. https://www.nonpartisaneducation.org/Review/Resources/Stotsky-Optional_ELA_standards.pdf (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Sullivan, Kevin. 1985. Anne of green gables. https://www.anneofgreengables.com/ (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo van. 1999. Speech, music, sound. London: Macmillan.10.1007/978-1-349-27700-1Search in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo van. 2005. Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203647028Search in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 2025. Sound bites: Avenues for research in the study of speech, music, and other sounds. Journal of World Languages. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0037.Search in Google Scholar

Winokur, Mark & Bruce Holsinger. 2001. The complete Idiot’s guide to movies, flicks, and film. Indianapolis, IN: Alpha Books.Search in Google Scholar

Zemeckis, Robert. 2004. The polar express. https://polarexpress.fandom.com/wiki/The_Polar_Express_(film) (accessed 10 November 2025).Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.