Abstract

This study adopts a system perspective to explore how inventory, process, and constraint function to shape the complexity of syllable onsets in Southern Min. Only 15 onsets are phonemic, but they present several typologically uncommon features and are rich in allophonic variations. About 57 variants are identified that are triggered by only three distinct features from subsequent segments, and involve processes of dentalization, palatalization, labialization, lenition, lamination, glottalization, nasalization, and prenasalization. The usage frequency of onsets and their combinability with other syllable components are severely constrained, leading to more than 71% of theoretically possible syllables failing to be attested. The nasality feature from nuclei, labial feature within syllables, complexity of final types, diachronic requirements for assigning tones with respect to syllable onsets and codas, and the nature of onsets can all evoke constraints. This exploration has significant implications for our knowledge of segmental phonetics, segmental phonology, and segmental phonotactics in this language. It is hoped that this study will contribute to the understanding of the importance of inventory, process, and constraint in the phonological research of specific languages, and shed light on adopting the perspective of system to investigate other phonological categories and stretch our cognition of natural languages.

1 Introduction

Phonology concerns the sound system of a language. It deals with inventories within a system that engage with how many contrastive consonants, vowels, and suprasegments (tones, stresses etc.) are used to make lexical distinctions (e.g. Bickford and Floyd 2006; Gimson 1980; Ladefoged and Disner 2012; Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996; Maddieson 2013a; Maddieson 2013b; Szigetvári 2010; Yule 2010). It cares about processes within a system that engage with how the system is dynamic in real-world utterances, such as how assimilatory adjustments of phonemes are made to adapt to the nature of surrounding surrounds, and how reductions may occur in a non-prominent position (cf. Anderson 1978; Cohn 2007; Gurevich 2011; Hyman 1975; Kochetov 2011; Ohala 1993; Pike 1947). It also addresses constraints within a system that engage with how the distribution of phonemes, their relative frequency, and interrelationships with other elements are constrained (e.g. Algeo 1975; Celata and Calderone 2015; Clements 1988; Duanmu 2003; Kager 1999; Kirby and Yu 2007; Pearce 2007; Zec 1995; Zhang 2006). As indicated, inventories, processes, and constraints are essential portions of a system that form the core of phonology. A sound knowledge of the phonology of specific languages or language families is expected to provide a clear understanding of how inventories, processes, and constraints function as parts of a system. However, in conventional models of phonological descriptions of individual languages, attention is predominantly given to encoding inventories and less time is spent on processes and constraints. This is noted by Maddieson (2023) that, ‘information on inventories is more uniformly present in language descriptions… whether they come in the form of a chapter or so in a descriptive grammar, as a dedicated paper or book on the phonology of language X or the introductory pages to a bilingual dictionary.’ Likewise, in a considerable number of phonological databases, such as PBase (Mielke 2008), UCLA Phonological Segment Inventory Database (UPSID, Maddieson and Precoda 1990), Lyon-Albuquerque Phonological Systems Database (LapSyd, Maddieson et al. 2013), the Database of Eurasian Phonological Inventories (EURPhon, Nikolaev 2018), PHOIBLE 2.0 (Moran and McCloy 2019), SegBo (Grossman et al. 2020), BDPROTO 1.1 (Moran et al. 2021), and Phonotacticon 1.0 (Joo and Hsu 2025), they exclusively document inventories for a large and diverse sample of languages, and rarely archive processes and constraints. A similar situation can also be seen in studies of phonological typology, in which the focus is dominantly on the areal and genealogical distribution of inventories. As can be seen, our understanding and research efforts in phonology tend to be imbalanced. Information on processes and constraints is relatively limited.

This study is grounded in the perspective of system to undertake an in-depth exploration of inventories, processes, and constraints of speech sounds in languages. It will specifically focus on the phonological category of consonants that function as syllable onsets, typically before nuclei (cf. Blevins 1995; Davis 1982; Fudge 1969; Selkirk 1982). Cross-linguistically, onsets can be characterized using diverse dimensions, from the manner of articulation, the place of articulation, laterality, nasality, phonation, aspiration, airstream mechanism, to vocal fold vibration (e.g. Bickford and Floyd 2006; Ladefoged and Disner 2012; Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996; Maddieson 2013a, 2013b; Szigetvári 2010; Yule 2010). For example, depending on where the airstream is initiated and in which direction it flows within a vocal tract, onsets can be divided into pulmonic egressive, glottalic egressive (ejective), glottalic ingressive (implosive), and velaric ingressive (click) (Bickford and Floyd 2006). Likewise, depending on whether the vocal folds vibrate over production, they can be classified as either voiced or voiceless. Languages vary in the consonants that can occur as onsets. For example, consonant clusters are permitted in English, as in the words strong, spring, and splash (Yule 2010), but are banned in Sinitic and Fijian languages (Zec 1995). In most conventional studies, the descriptions are restricted to providing a list of onset phonemes and showing how they are distinguished. They pay less systematic attention to exploring how the continuous motion of human vocal apparatus induces diverse surface outputs of onset phonemes, the phenomenon of which can be captured as allophonic variations (e.g. Bickford and Floyd 2006; Ladefoged and Disner 2012; Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996; Maddieson 2013a, 2013b; Szigetvári 2010; Yule 2010) and that belongs to the concern of processes within the perspective of system. They also pay less systematic attention to examining whether onset phonemes can randomly combine with other syllable components to generate linguistic entities, such as syllables and morphemes, for the purpose of communication, a phenomenon that can be captured as phonotactics (e.g. Algeo 1975; Celata and Calderone 2015; Clements 1988; Duanmu 2003; Kirby and Yu 2007; Pearce 2007; Zec 1995; Zhang 2006), which belongs to the concern of constraints from the perspective of the system.

This study aims to uncover how inventories, processes, and constraints work to encode onset consonants as a system and to manifest their complexity and dynamics in a specific language. The exploration is based on the Sinitic language of Southern Min, commonly referred to as Hokkien or Min Nan, which has significant implications for expanding our phonological knowledge. Diachronically, this language is asserted to have split off from mainstream Sinitic languages in the transition period between Western and Eastern Han (roughly 50 BCE–50 CE) and has been regarded as a living fossil by historical linguists to construct the proto-language of Old Chinese around 1200 BC (cf. Baxter and Sagart 2014; Matisoff 1973; Michaud and Sands 2020; Norman 1991). For example, no labial-dental fricative onset phoneme is postulated in Old Chinese, and this can be justified in Southern Min because no words are attested beginning with onsets such as /f/ and /v/. On the contrary, such onsets are widely reported in other Sinitic languages, such as the words /fa55/ ‘deliver’, and /fo35/ ‘buddha’ in Mandarin; /vu3/ ‘father’ and /fu1/ ‘husband’ in Shanghainese (Chen and Gussenhoven 2015), and /fa1/ ‘flower’, /fat6/ ‘method’ in Cantonese (Bauer and Benedict 1997). Synchronically, this language encodes syllable onsets in a highly complex, dynamic, and constrained manner. It has an inventory of only 15 onset phonemes, which is smaller than that of a vast variety of languages worldwide. However, it has several typologically uncommon characteristics. For example, the aspiration and voicing features are distinct in formulating a three-way contrast among supraglottal stops (/p, t, k/ vs. /pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/ vs. /ɓ, ɗ, ɠ/); the ingressive airstream mechanism is phonemic in constructing implosive onsets of three places of articulation (/ɓ, ɗ, ɠ/). No nasal consonants are phonemic at the onset position while nasal vowels, syllabic nasals and nasal codas are extensively used by native speakers. Moreover, the processes of allophonic variations are extraordinarily dynamic among onset consonants. A single onset phoneme can surface several variants, and over 50 variants can be derived at the output. For example, the glottal stop /ʔ/ has six variants: [ʔ], [ʔj], [ʔw], [mʔ], [nʔ], and [ŋʔ]. Three implosive onsets /ɓ, ɗ, ɠ/ can surface eleven variants: [ɓ], [β], [m], [ɗ̪], [lʷ], [n], [ɗ], [ɠʲ], [ɣʷ], [ŋ], and [ɠ]. The processes of variation are triggered by only three distinctive features (palatal, nasality, and labial) from subsequent sounds, but they can induce a variety of changes on target onsets, which include altering airstream mechanism, manner of articulation, active articulator, location of primary constriction, and a secondary articulation. In addition, the usage frequency of individual onsets and their combinability with other syllable components (finals and tones) are severely constrained, leading to more than 71% of syllables, which are theoretically possible to occur, failing to be attested in the field. The constraints are dominantly invoked by the nasality feature of nuclei, the co-occurrence restriction of the labial feature, the complexity of internal structures, the diachronic restrictions of assigning tones with respect to syllable onsets and codas, and the nature of onset phonemes. For example, voiced onsets are banned from occurring before syllabic nasals, and labial onsets are not allowed to co-occur with codas of the same labial feature. As illustrated above, the system of syllable onsets in Southern Min is far more complex than expected, but it provides an important basis to stretch our knowledge of how inventories, processes, and constraints work to shape a complex system in specific languages.

This study incorporates field linguistics, phonetic and phonological theories, and Sinitic dialectology to conduct an in-depth and comprehensive exploration of the onset system in Southern Min. It addresses three main research questions that correspond to three main aspects (inventories, processes, and constraints) of a system.

How many onset phonemes are contrastive, and what is their typological significance?

How do onset phonemes change their forms to react to the featural properties of subsequent segments, and how can their allophonic processes be interpreted using rules within the paradigm of generative phonology?

How can the usage frequency of onset phonemes and their combinability with other syllable components be constrained to generate the linguistic entities of monosyllabic morphemes, and what factors may trigger phonotactic constraints?

This research is data-driven, but each research task will particularly focus on its phonological and typological background and significance. In the inventory section, both typologically common and uncommon characteristics of onset phonemes in this language will be discussed. In the section of processes, attention will focus on exploring how varying triggers from vocalic segments impact the surface forms of onset phonemes, and how onset phonemes react differently to their occurring environments. It will examine all possible processes and discuss the mechanisms behind the asymmetrical reactions of onsets and the asymmetrical distributions of allophonic processes. In the section of phonotactics, it will build upon an exhaustive examination of all possible combinations of onsets, finals (a term that is created in Sinitic convention to refer to all syllable components except onset), and tones. It will focus on how the usage frequency of onset phonemes is constrained at the syllable level and what factors constrain the onset-final and onset-tonal combinations over the generation of syllables for communication. It is hoped that this in-depth examination of Southern Min onsets will contribute to an understanding of the importance of inventories, processes, and constraints in the phonological research of natural languages, shed light on adopting the perspective of system to investigate phonological categories other than consonants, and expand our knowledge of languages.

2 Southern Min and Zhangzhou speech

Southern Min (ISO 639-3 [nan]) originates from two cities of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou in Fujian Province along the southeast coast of China; however, it is transnational in nature. This is because, as early as the 6th century, the Southern Min ethnic group has been migrating to a wide range of regions in the world, particularly in Southeast Asia, such as Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Thailand (cf. Ding 2016; Jones 2009; Kwok 2019; Sew 2020). The language of Southern Min, known as Hokkien for the colloquial pronunciation of its birthplace of Fujian, had long served as a lingua franca among overseas Chinese populations in history. Thus, Southern Min, in a broader sense, should incorporate the varieties spoken outside Fujian in China. This study is based on the speech sounds of Zhangzhou, one of the two birthplaces of Southern Min. Zhangzhou is a prefecture-level city situated in the southern seaward part of Fujian Province in China, with a registered population of approximately 5.05 million and an area of approximately 12,600 square kilometers in the 2020 census (Huang 2021). The colloquial language in Zhangzhou is Southern Min, which is mutually intelligible with other Southern Min varieties in Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taiwan, and overseas, but is uncommunicable with other Sinitic languages such as Hakka, Wu, Cantonese, and Jin. However, Mandarin has replaced Southern Min as the mother tongue among younger generations because of its dominant status as the only official language in China.

The Zhangzhou dialect is a variety of Southern Min. The City of Zhangzhou governs eleven administrative areas, and certain regional variations can be observed in their sound systems. For example, Yangru tone (Tone 7 in this study), which is diachronically related to syllables with voiced onsets and obstruent codas, has been transcribed as a short high contour [4] in Longhai District, a mid-level contour [33] in Changtai District, a low-rising contour [13] in Dongshan and Zhao’an Counties, and as a convex contour of either [121] or [131] elsewhere (Yang 2008). Because this study is not designed to examine the socio-phonetic variation of onsets across different regions in this city, the research locality is strictly restricted to the urban area of Xiangcheng and Longwen Districts, which is conventionally considered to be historically, socially, culturally, and linguistically representative of Zhangzhou and has received the most attention in the literature (e.g. FJG 1998; Gao 1999; Huang 2018, 2019, 2021, 2023a, 2023b, 2024; Ma 1994; Schlegel 1886; Xie 1818; Yang 2008; ZZG 1999). The data were mainly from two sources: (a) field data collected by the author in Xiangcheng and Longwen in 2015 and 2025, and (b) rhyme tables that Huang (2021) compiled to tabulate all possible combinations of syllable onsets, finals, and tones in the generation of monosyllabic morphemes.

Lexical morphemes in this language are dominantly monosyllabic, such as /tĩ35/ ‘sweet’, /tŋ̩22/ ‘long’, /ke35/ ‘chicken’, and /ɗɔ33/ ‘road’, while multisyllabic morphemes are also used by communities, such as /ɗɐj32.tsi35/ ‘litchi’, /ɗiŋ22.kɐn/ ‘longan’, /pi33.pɛ22/ ‘loquat’, and /ɓɐ̃35.ɗiŋ33.tsi22/ ‘potato’. Syllables can be generalized as having a C(G)V(X) structure in which the onset consonant (C) and nucleus (V) are compulsory, whereas the prevocalic glide (G) and coda (X) are optional (Huang 2021). An inventory of 15 onsets, 2 prevocalic glides, 13 nuclei, and 8 codas can be posited as phonemically distinctive, as summarized in Table 1. Segments that can function as nuclei are diverse, including oral vowels, nasal vowels, and syllabic nasals. This reflects the distinctive function of the nasality feature in the vocalic system, which is typologically rare in spoken languages. Likewise, segments that can serve as codas are diverse, including glides, nasal consonants, and obstruent stops. Consonantal clusters are banned from occurring in both onset and coda positions.

Segmental inventory of Zhangzhou Southern Min.

| Component | Phoneme | |

|---|---|---|

| C | onset | p, pʰ, ɓ, t, tʰ, ɗ, k, kʰ, ɠ, ts, tsʰ, s, z, ħ, ʔ |

| G | glide | j, w |

| V | nucleus | i, e, ɛ, ɐ, ɔ, ɵ, u, ĩ, ɛ̃, ɐ̃, ɔ̃, m̩ ŋ̩ |

| X | coda | j, w, m, n, ŋ, p, t, k |

As a typical Sinitic language, tones in Zhangzhou are contrastive to deliver lexical meanings. All conventional documents posited seven tones but with inconsistent transcriptions in pitch (FJG 1998; Gao 1999; Guo 2014; Lin 1992a; Lin 1992b; Lin 1992c; Ma 1994; Medhurst 1832; Schlegel 1886; Xie 1818; Yang 2008; Zhou 2006; ZZG 1999). Huang (2018) proposed a system of eight tones based on a multidimensional investigation of tonal properties in different contexts. The eighth tone emerges from those syllables that are conventionally transcribed with a glottal stop coda in Yangru tone (Tone 7 in this study), a Middle Chinese (MC) tonal category, but the glottal stop coda is found to have undergone deletion, rendering its related syllables open and have different tonal manifestations. Table 2 summarizes the eight tones in this language, along with their names in the MC tonal category, to make them diachronically traceable and synchronically comparable with other Sinitic languages. This tonal inventory serves as a foundation for exploring how onset-tone alignments are constrained at the syllable level. It should be noted that in this language, tones that share a similar F0 contour can differ considerably in other parameters (Huang 2018). For example, Tone 4 (/ti41/ ‘drop’) and Tone 6 (/tit41/ ‘bamboo’) both show a mid-high falling contour in citation, but tone 6 is shorter, and its related high vowels are diphthongized. Likewise, Tone 2 (/pɛ22/ ‘crawl’) and Tone 8 (/pɛ22/ ‘white’) both present a low-level contour in citation, but in a non-rightmost (sandhi) position, Tone 2 shows a mid-level contour (/pɛ33.ħiŋ22/ ‘crawl forward’) while Tone 8 (/pɛ32.sik41/ ‘white color’) shows a mid-falling contour.

Examples of Zhangzhou tones.

| Tone | Pitch citation | Duration citation | Pitch sandhi | Example 1 | Example 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yinping | [35] | extra-long | [33] | /tɐŋ35/ ‘east’ | /kɔ35/ ‘mushroom’ |

| 2 | Yangping | [22] | extra-long | [33] | /tɐŋ22/ ‘copper’ | /kɔ22/ ‘glue’ |

| 3 | Shang | [51] | medium | [35] | /tɐŋ51/ ‘to wait’ | /kɔ51/ ‘drum’ |

| 4 | Yinqu | [41] | medium | [63] | /tɐŋ41/ ‘frozen’ | /kɔ41/ ‘look after’ |

| 5 | Yangqu | [33] | extra-long | [32] | /tɐŋ33/ ‘heavy’ | /ħɔ33/ ‘rain’ |

| 6 | Yinru | [41] | short | [65] | /tɐp41/ ‘answer’ | /kɔk41/ ‘country’ |

| 7 | Yangru | [221] | long | [32] | /tsɐp221/ ‘ten’ | /tɔk221/ ‘poison’ |

| 8 | Yangru | [22] | extra-long | [32] | /tsi22/ ‘tongue’ | /kɔ̃22/ ‘snore’ |

3 Inventory of onset phonemes in Zhangzhou

3.1 The size of onset inventory

In this language, only 15 onsets are phonemically contrastive to make lexical distinctions. They are summarized in Table 3 and illustrated in Table 4 with (near-) minimal pairs. The size of this onset inventory is smaller than that of most languages and/or dialects in China and many others worldwide. For example, among a sample of 70 Chinese dialects (Zee and Zee 2014), the number of onset phonemes ranges from 14 in Putian of Middle Min and Ningde of Northern Min to 29 in Xinhua of the Xiang language. Thus, it seems that only a few languages in China have a smaller onset inventory than this language. Likewise, in a cross-linguistic survey of 317 languages worldwide (Maddieson 1984), the East Papuan language Rotokas has the lowest number of 6, whereas the Khoisan language! Xũ has the greatest number of 46, which is primarily due to the large number of clicks and laryngeal contrasts exploited by both click and non-click consonants (Gordon 2016; Maddieson 1984). As can be predicted, the number of 15 onset consonants in Zhangzhou is supposed to be lower than many of the world’s languages. The reason why the onset inventory is small in this language is unclear, but it might be ascribed to a compensatory relationship between the number of vowels and onset consonants. For example, Zee and Zee (2016) report that among 70 dialects in China, the number of vowels ranges from a low of 3 in Yongding of the Hakka language to a high of 13 in Ningbo of the Wu language. Maddieson (1984) reports that the vast majority of languages have between five and seven vowels (64.7 %), with the modal number being five (30.9 %). In Zhangzhou, a total of 11 vowels (7 oral vowels and 4 nasal vowels) is predictable to be larger than in most of the world’s languages, and this might potentially reduce the number of consonants to function as onset phonemes in this language.

Onset system of Zhangzhou Southern Min.

| Manner | Bilabial | Alveolar | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p | pʰ | ɓ | t | tʰ | ɗ | k | kʰ | ɠ | ʔ | |

| Fricative | s | z | ħ | ||||||||

| Affricate | ts | tsʰ | |||||||||

Examples of Zhangzhou onset phonemes.

| Onset | Example 1 | Example 2 | Example 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| /p/ | /pi35/ ‘sad’ | /pɐŋ35/ ‘help’ | /pu33/ ‘hatch’ |

| /pʰ/ | /pʰi35/ ‘drape’ | /pʰɐŋ35/ ‘fragrant’ | /pʰu33/ ‘boil and spill out’ |

| /ɓ/ | /ɓi35/ ‘squint’ | /ɓɐŋ35 / ‘do not’ | /ɓu33/ ‘frog’ |

| /t/ | /ti35/ ‘pig’ | /tɐŋ35/ ‘east’ | /tu22/ ‘kitchen’ |

| /tʰ/ | /tʰi35/ ‘sticky’ | /tʰɐŋ35/ ‘window’ | /tʰu41/ ‘to shovel’ |

| /ɗ/ | /ɗi41/ ‘tear’ | /ɗɐŋ35/ ‘barracuda’ | /ɗu33/ ‘slip’ |

| /k/ | /ki35/ ‘base’ | /kɐŋ35/ ‘river’ | /ku33/ ‘old; worn’ |

| /kʰ/ | /kʰi35/ ‘deceive’ | /kʰɐŋ35/ ‘empty’ | /kʰu33/ ‘mortar’ |

| /ɠ/ | /ɠi35/ ‘childish’ | /ɠɐŋ22/ ‘raise’ | /ɠu33/ ‘giggle (infant)’ |

| /ts/ | /tsi35/ ‘grease’ | /tsɐŋ35/ ‘brown’ | /tsu33/ ‘self; from’ |

| /tsʰ/ | /tsʰi35/ ‘idiotic’ | /tsʰɐŋ35/ ‘spring onion’ | /tsʰu33/ ‘slippery’ |

| /s/ | /si35/ ‘poetry’ | /sɐŋ35/ ‘relax’ | /su33/ ‘thing; issue’ |

| /z/ | /zi35/ ‘money’ | /zin22/ ‘people’ | /zu33/ ‘affluent’ |

| /ħ/ | /ħi35/ ‘weak’ | /ħɐŋ35/ ‘dry’ | /ħu33/ ‘father’ |

| /ʔ/ | /ʔi35/ ‘he/she’ | /ʔɐŋ35/ ‘husband’ | /ʔu33/ ‘have’ |

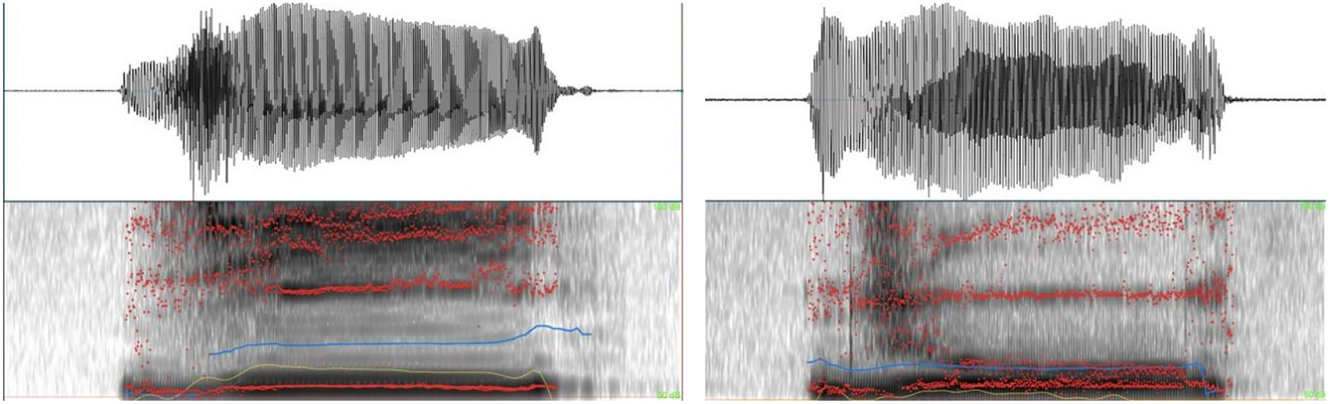

It should also be noted that conventional work all posited 15 onset phonemes for this language (FJG 1998; Gao 1999; Guo 2014; Lin 1992a, 1992b, 1992c; Ma 1994; Medhurst 1832; Schlegel 1886; Xie 1818; Yang 2008; Zhou 2006; ZZG 1999), with four voiced onsets transcribed differently from this study. They all documented a voiced alveolar affricate /dz/, but this onset was found to be a fricative /z/ in the empirical data across speakers. This can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the spectrograms of morphemes /zi33/ ‘character’ and /zu22/ ‘such as.’ No voiced bars or burst releases were identified before frication for either morpheme. This indicates that no oral constriction is created during their production. In other words, they are not articulated with an affricate manner of articulation, as transcribed as /dz/ in previous work. Instead, they are produced with a fricative manner of articulation, and this onset should thus be posited as /z/ to reflect the reality in the field.

Spectrograms of /zi33/ ‘character’ (left) and /zu22/ ‘such as’ (right).

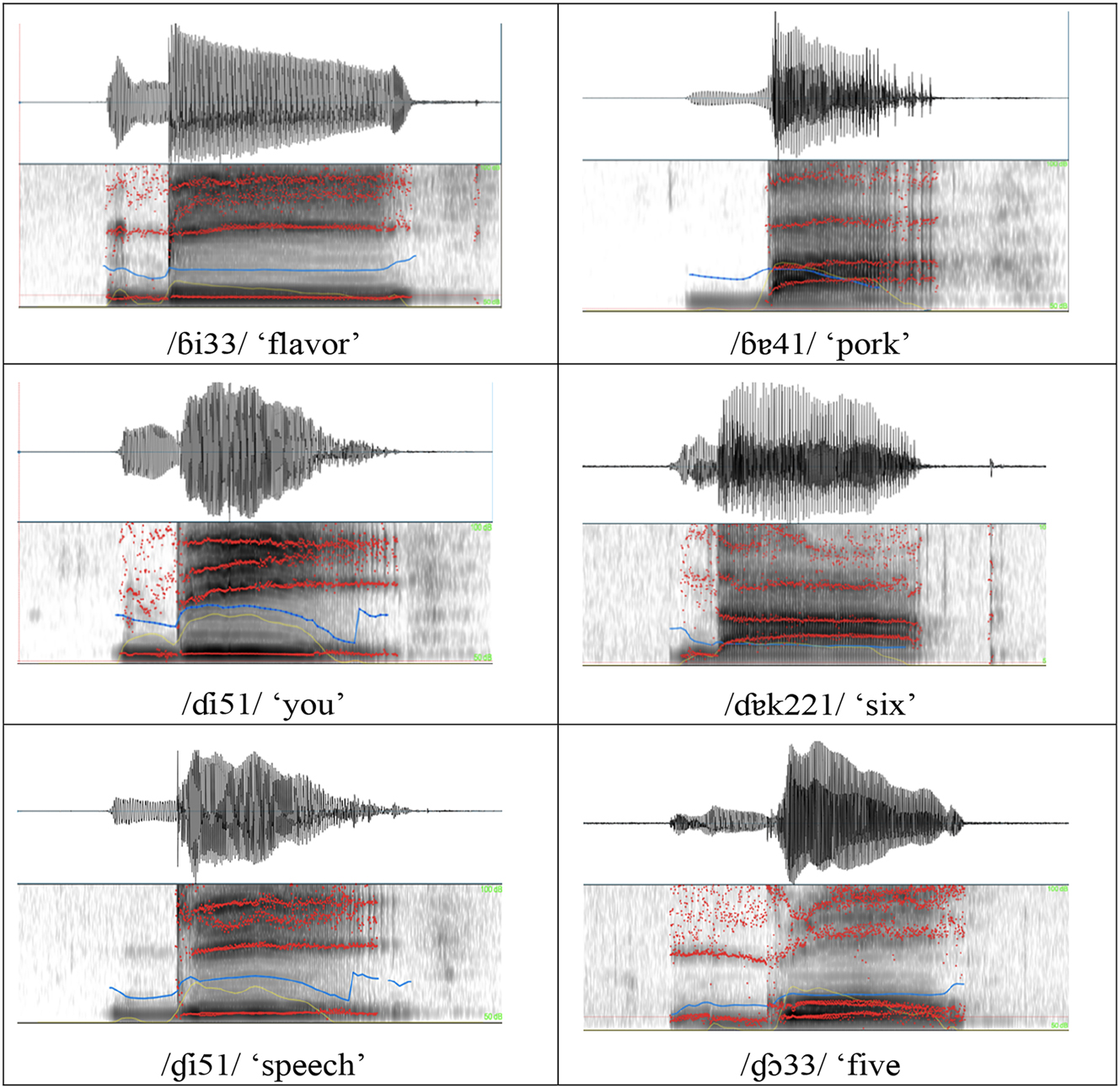

Prior work documented voiced onsets /b/, /l/, /g/ in their segmental inventory (e.g., FJG 1998; Gao 1999; Guo 2014; Lin 1992a; Lin 1992b; Lin 1992c; Ma 1994; Medhurst 1832; Schlegel 1886; Xie 1818; Yang 2008; Zhou 2006; ZZG 1999); however, these onsets are separately produced as implosives /ɓ/, /ɗ/, /ɠ/ in unmarked environments by native speakers regardless of genders and ages, and have several allophonic variants which will be discussed in the next section. Their implosive articulation can be demonstrated in the spectrograms. As shown in Figure 2, a voiced bar can be clearly identified before the formant patterns across all morphemes. This signifies a voiced manner of articulation and indicates that over the production of related onsets, a complete oral constriction is formed at a certain point in the speaker’s oral cavity, depending on their place of articulation, and the vocal folds vibrate in a regular fashion. In addition, the amplitudes of the air pressure fluctuations in the waveforms were maintained without significant change over the entire portion of the onsets, rather than dropping to zero before the release of oral constriction. This indicates a special ingressive glottalic airstream for implosive sounds. It occurs because speakers block off their glottis during articulation but continually suck in airflow from outside into their mouth until they achieve a maximum amount of air pressure, after which they open their glottis and release the constriction to let the air pressure from both lungs and mouth flow out of the vocal tract (Clements and Osu 2002; Cun 2010; Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996; Mori 2023). As such, it is empirically justifiable to propose implosives /ɓ, ɗ, ɠ/ as onset phonemes that falsify prior transcriptions but advance our knowledge of this language.

Spectrograms and waveforms of Zhangzhou implosives.

3.2 Typologically common and uncommon characteristics

The onset system of this language can be characterized in several ways. It shows several universals in phonemic distribution but also presents several typologically uncommon features that contribute to our understanding of human language diversity. These onsets present a five-way contrast in terms of the place of articulation, which includes bilabial /p, pʰ, ɓ/, alveolar /t, tʰ, ɗ, s, z, ts, tsʰ/, velar /k, kʰ, ɠ/, pharyngeal /ħ/, and glottal /ʔ/. Seven of the 15 onsets were alveolars, accounting for 47 % of the total onsets. This indicates the high contribution of the front of the tongue and the alveolar place in speech production in this language. This reflects a universal tendency; for example, 97.5 % of the 317 languages in Maddieson ’s (1984) survey have alveolar sounds, followed by velars in 89.3 % and bilabials in 82.9 %. Likewise, these onsets present a three-way contrast in terms of the manner of articulation, including plosive /p, pʰ, ɓ, t, tʰ, ɗ, k, kʰ, ɠ, ʔ/, fricative /s, z, ħ/, and affricate /ts, tsʰ/. It can be seen that plosive sounds occupy as many as 67 % of the total onsets, implying that complete constriction is the dominant manner of articulation in speech distinction in this language. It also reflects the universality that languages most commonly contrast unaffricated plosives, particularly at three places of articulation (labial, alveolar, and velar) (e.g. Gordon 2016; Maddieson 1984; Nikolaev 2022).

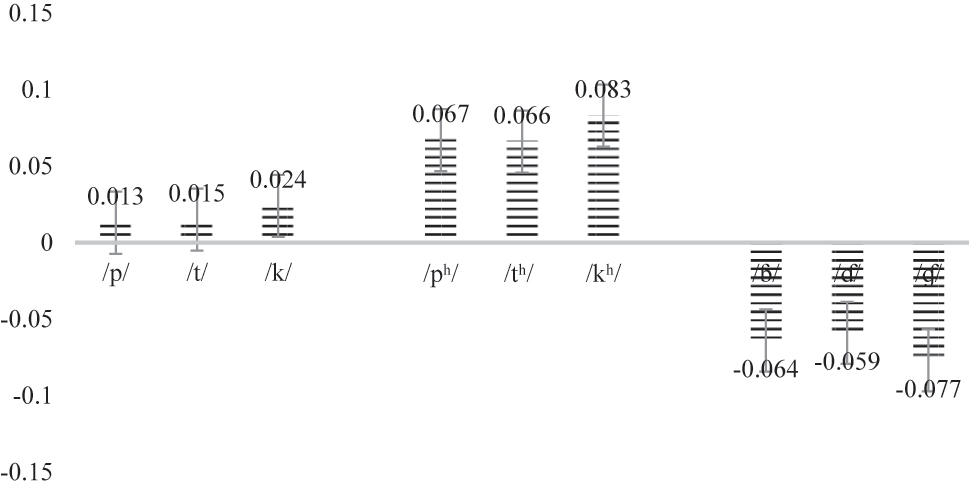

Supraglottal plosives can be further classified into three subcategories in terms of aspiration and voicing: voiceless unaspirated /p, t, k/, voiceless aspirated /pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/, and voiced /ɓ, ɗ, ɠ/. This is typologically uncommon. For example, according to Maddieson’s (1984) survey of 317 languages, less than 24.0 % of languages present a three-way laryngeal contrast on unaffricated oral stops, while over 51.1 % of languages present a two-way contrast between voiceless and voiced stops (Gordon 2016). In addition, this language is typologically uncommon because it employs a special ingressive glottalic airstream to construct implosive onsets of three places of articulation. This is because only 10 % (Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996) to 20 % (Clements and Osu 2002; Cun 2010) of the world’s languages are reported to have an implosive articulation at an underlying level. The three-way contrast among supraglottal plosives can be demonstrated by the acoustic parameter of voice onset time (VOT), which is the time between the release of an oral constriction for plosive production and the onset of vocal fold vibration (Abramson and Whalen 2017). This is shown in Figure 3. The VOT value is slightly above zero across voiceless unaspirated plosives /p, t, k/, reflecting that speakers vibrate their vocal folds immediately after the release of oral constriction. The VOT value is steeply positive from 0.067 to 0.083 s across voiceless aspirated plosives /pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/, reflecting that after an oral constriction is released, there is a period of articulation for aspiration, which could induce a delay in vocal fold vibration. In contrast, the VOT value is steeply negative between −0.077 and −0.064 s for voiced sounds /ɓ, ɗ, ɠ/, reflecting that speakers vibrate their vocal folds before releasing an oral constriction.

VOT of Zhangzhou occlusive onsets.

An additional typologically uncommon feature of this onset system is that nasal consonants are not phonemic in this onset position. This is cross-linguistically unusual. In Maddieson (1984)’s survey, only seven of 317 languages (2.2 %) lacked phonemic nasal consonants. In Zee and Zee (2014)’s survey of 70 Chinese dialects, only one dialect lacked a labial nasal onset, 12 dialects lacked a velar nasal onset, and 14 dialects lacked an alveolar nasal onset. This language is among the very few to lack any of nasal onsets. It should be noted that while nasal onsets are not attested, the nasality feature is extensively used to construct nasal vowels, syllabic nasals, and nasal codas in this language. For example, four of seven oral vowels can be nasalized and used phonemically, such as /ti35/ ‘pig’ versus /tĩ35/ ‘sweet’, /kɛ35/ ‘home’ versus /kɛ̃35/ ‘net’, /kɐ/35/ ‘glue’ versus /kɐ̃35/ ‘prison’, /kɔ22/ ‘past’ versus /kɔ̃22/ ‘snore’. The bilabial syllabic nasal /m̩/ can carry five different pitch contours to differentiate five different words, such as /ʔm̩24/ ‘drink’, /ʔm̩22/ ‘flower bud’, /ʔm̩51/ ‘aunt’, /ʔm̩41/ ‘affirmative’, and /ʔm̩33/ ‘negative’. The velar syllabic nasal /ŋ̩/ can combine with twelve out of fifteen onsets to create monosyllabic morphemes, such as /pŋ̩51/ ‘list of names’, /pʰŋ̩51/ ‘ebb tide’, /tŋ̩35/ ‘wait’, /tʰŋ̩41/ ‘hot’, /ɗŋ̩22/ ‘small taro’, /sŋ̩51/ ‘play’, /tsŋ̩35/ ‘village’, /tsʰŋ̩22/ ‘bed’, /kŋ̩41/ ‘steel’, /kʰŋ̩41/ ‘hind’, /ħŋ̩35/ ‘prescription’, and /ʔŋ̩35/ ‘centre’. In the meanwhile, nasal codas of a three-way contrast in the place of articulation can be identified, such as /sim35/ ‘heart’, /sin35/ ‘new’, and /siŋ35/ ‘rise’.

Such an asymmetrical distribution of the nasality feature is also typologically rare enough. Because it is common for languages to possess nasal onsets only and lack nasal vowels and syllabic nasals in their phonemic inventory. In contrary, it is uncommon for languages to possess nasal vowels, syllabic nasals and nasal codas and do not have any nasal onset at the underlying level. However, this does not mean that the nasality feature does not perform any function on syllable onsets in this language, instead, it can affect their phonetic realizations and induce diverse outputs at the surface level. This will be discussed in detail in next section.

3.3 Distinctive features

As introduced above, this language possesses an onset system smaller than many of languages in the world. It presents several universals, such as the preference of the alveolar sounds and plosive manner of articulation, reflecting cross-linguistic tendencies in the construction of onset consonants in natural languages. It reveals several typologically unusual characteristics, such as the three-way contrast of supraglottal stops, the phonemic usage of implosive sounds, and the lack of nasal onsets, contributing to the typology of speech sounds and our understanding of the diversity of human languages. However, in spoken languages, speech sounds do not always act independently, instead, multiple sounds often participate in the same sound patterns (Mielke 2008). In other words, a group of sounds in an inventory may behave similarly because of specific properties, rather than because of the sounds themselves (Kennedy 2016; Mielke 2008). To capture the way that speech sounds function as a system, the concept of natural class is proposed in literature to refer to a group of sounds within a language that may either trigger or undergo the same phonological process, and the concept of distinctive features is proposed to group them into natural classes (cf. Arthur 1983; Chomsky and Halle 1968; Clements 2003; Hyman 1975; Keating 1991; Kennedy 2016; Lisker and Abbramson 1971; McCarthy 1988; Mielke 2008). Distinctive features have been widely assumed to be part of Universal Grammar since the mid-twentieth century and have been considered as the building blocks of phonological patterns (Kennedy 2016; Mielke 2008). They decode components of individual phonemes that help distinguish them from others, but also express phonemes formally as groups because they share one or more features.

In this language, a set of ten distinctive features are posited, as presented in Table 5. They cover three major categories, including features of the place of articulation ([labial], [coronal], [dorsal], [pharyngeal]), features of the manner of articulation ([voice], [spread glottis], [constricted glottis]), and laryngeal features ([continuous], [sibilant/strident], [delay release]). The binary features are used to specify onset phonemes, with a positive value [+] denoting the presence of a specific feature, and a negative value [−] indicating the absence of a feature.

Distinctive features for Zhangzhou syllable onsets.

| Class | Feature | p | pʰ | ɓ | t | tʰ | ɗ | k | kʰ | ɠ | ts | tsʰ | s | z | ħ | ʔ |

| Place | labial | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| coronal | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| dorsal | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| pharyngeal | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| glottal | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | ||

| Laryngeal | voice | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| spread glottis | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| constricted glottis | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Manner | continuant | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| sibilant/strident | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| delay release | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

As indicated in the table, these ten distinctive features form a geometry to characterize the components of individual onset phonemes in this language. For example, the bilabial implosive /ɓ/ can be denoted as [+labial, +voice, +continuant]. They can also effectively group a set of onsets as a natural class because of sharing one or more distinctive features. For example, the onsets /ɓ, ɗ, ɠ, z/ form a natural class because of the common distinctive feature [+voicing]. This feature geometry is important to serve as a base to explore how onset phonemes change their quality at the surface level; what specific features trigger their alternations, and how their alternations can be expressed using rules within the paradigm of generative phonology.

4 Allophonic variation of Zhangzhou onsets

Phonology is the study of the organization of sounds in human languages. Each language has a fixed set of sounds (known as phonemes) that are contrastive and combinable into longer sequences in patterned ways, to which meanings and function are in turn associated (Gordon 2016; Kennedy 2016; Mielke 2008). For example, in this language, fifteen onsets are tested to be phonemic. However, phonemes are symbols. They are part of the knowledge that represents the mental activity of speakers of a language and that exist within the lexicon of underlying forms in a language. In real-world utterances, phonemes may change their forms because of the nature of adjacent sounds, and the term phonological process is used to express the phenomenon in which the phonetic form of a phoneme changes based on context, and the term allophones are used to refer to different surface forms of a common phoneme if they never occur in equivalent environments. This reflects the manifestations of phonemes adapting to their environments (cf. Arthur 1983; Gordon 2016; Hyman 1975; Kennedy 2016; Mielke 2008). Likewise, the term alternation is used to refer to the phonological process in which a phoneme takes one form in one context, and a different form in some other context. It reflects the reaction of phonemes to the presence of adjacent or proximate segments by changing their forms. The phonological process and alternation are universals that are widely observed in the phonology of the world’s languages. Their existence may induce multiple consequences at the level of segments, such as alternate and constrain the featural properties of sounds (e.g. assimilation and dissimilation), change in the number of sounds (deletion, insertion), and even alternate in the ordering of adjacent or nearby sounds (metathesis) (Gordon 2016). As such, the goal of this phonological analysis of Southern Min onset system should not be restricted to uncover evidence of phonemic contrasts but should include uncovering evidence of allophonic variations and distributions of those contrastive onsets.

Zhangzhou has an onset inventory smaller than many other languages, but this does not mean that its onset system is simple. Phonological processes are incredibly active in this language. Individual onset phonemes can have several variants that are complementary to occur in different environments, for example, the three implosive onsets /ɓ/, /ɗ/, and /ɠ/ surface eleven variants that include [ɓ], [β], [m], [ɗ̪], [lʷ], [n], [ɗ], [ɠʲ], [ɣʷ], [ŋ], [ɠ] (Huang and Hyslop 2022). As a whole, over fifty variants can be derived from its fifteen onsets, which are summarized in Table 6. The symbol * indicates no empirical data are attested in the field. The allophonic alternations of onset phonemes do not randomly occur, instead, they are dominantly triggered by three features from their immediately subsequent sounds, which incorporate the palatal feature from the high vowel /i/ and palatal glide /j/, the labial feature from the round vowel /u/ and labial glide /w/, and the nasality feature from nasal vowels and syllabic nasals. In other words, the phonological processes of onset alternation are local, in which the target (onset consonant) and trigger (subsequent vocalic segment) are adjacent. Moreover, the phonological processes are diverse that can be captured as dentalization, palatalization, labialization, lenition, lamination, glottalization, and nasalization among others. The phenomenon of allophonic variation from a phonetic perspective reflects continuous motions of articulatory apparatus of human beings, leading phonemes to be manifested differently in sequencing. From a phonological perspective, it reflects a universal of assimilation, involving alternating featural properties of sounds because of the nature of adjacent sounds. This section will provide an in-depth exploration into the distributional constraints and alternations of onset phonemes in Zhangzhou Southern Min.

Allophonic variation of Zhangzhou onsets.

| Manner | Place | Onset | Allophonic Variant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| _/ [i; j] | _/ [u; w] | _/[Ṽ] | _/[N̩] | Elsewhere | |||

| Plosive | bilabial | /p/ | p | p | mp | mp | p |

| /pʰ/ | pʰ | pʰ | mpʰ | mpʰ | pʰ | ||

| /ɓ/ | ɓ | β | m | * | ɓ | ||

| alveolar | /t/ | t̪ | t̻ʷ | nt | nt | t | |

| /tʰ/ | t̪ʰ | t̻ʰʷ | ntʰ | ntʰ | tʰ | ||

| /ɗ/ | ɗ̪ | lʷ | n | * | ɗ | ||

| velar | /k/ | kʲ | kʷ | ŋk | ŋk | k | |

| /kʰ/ | kʰʲ | kʰʷ | ŋkʰ | ŋkʰ | kʰ | ||

| /ɠ/ | ɠʲ | ɣʷ | ŋ | * | ɠ | ||

| glottal | /ʔ/ | ʔʲ | ʔʷ | nʔ | mʔ, ŋʔ | ʔ | |

| Fricative | alveolar | /s/ | ɕ | ʃʷ | ns | ns | s |

| /z/ | ʑ | ʒʷ | * | * | * | ||

| pharyngeal | /ħ/ | ħʲ | hʷ | nɦ | mɦ, ŋɦ | ħ | |

| Affricate | alveolar | /ts/ | tɕ | tʃʷ | nts | nts | ts |

| /tsʰ/ | tɕʰ | tʃʰ | ntsʰ | ntsʰ | tsʰ | ||

4.1 Palatal-conditioned variation

The high front vowel /i/ and palatal glide /j/ are active to trigger allophonic alternation on syllable onsets of this language. The trigger can be further specified as the [+palatal] feature that is shared by these two front vocoids, and it is further observed affecting the surface of onset phonemes in three different ways, depending on their place of articulation at an underlying level. This is generalized in Table 7.

palatal feature-induced variation on Zhangzhou onsets.

| Process | Onset | Before [i] | Before [j] |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) dentalization | /t/ | [t̪i35] ‘pig’ | [t̪jɐ41] ‘pluck’ |

| /th/ | [t̪ʰi51] ‘tear’ | [t̪ʰjɐ41] ‘crack’ | |

| /ɗ/ | [ɗ̪i33] ‘filter’ | [ɗ̪jɐ41] ‘pry open’ | |

| (b) alveolar-palatalization | /s/ | [ɕi22] ‘time’ | [ɕju22] ‘swim’ |

| /z/ | [ʑi22] ‘press’ | [ʑju22] ‘rub’ | |

| /ts/ | [tɕi22] ‘potato’ | [tɕjɵ22] ‘stone’ | |

| /tsh/ | [tɕhi22] ‘support’ | [tɕhjɵ22] ‘bamboo mat’ | |

| (c) palatalization | /k/ | [kʲi22] ‘flag’ | [kʲjɐ33] ‘steep’ |

| /kʰ/ | [kʰʲi22] ‘leech’ | [kʰʲjɐ33] ‘stand’ | |

| /ɠ/ | [ɠʲi22] ‘doubt’ | [ɠʲjɐ22] ‘carry’ | |

| /ħ/ | [ħji22] ‘fish’ | [ħjjɐ33] ‘tile’ | |

| /ʔ/ | [ʔji22] ‘mother’s sister’ | [ʔjjɐ33] ‘night’ |

(a) Alveolar plosives /t/, /tʰ/ and /ɗ/, regardless of their manners of articulation, are found to be dentalized and become [t̪], [t̪ʰ] and [ɗ̪], respectively, in this palatal environment. This is posited because over the articulation, native speakers do not raise their tongue to the alveolar ridge, but rather raising their tongue against the back of upper incisor. For example, the morpheme /ti35/ ‘pig’ is produced as [t̪i35] by native speakers, and the morpheme /tʰi51/ ‘tear’ is uttered as [t̪ʰi51] in real-world utterances. As can be seen, the alternation between /t, tʰ, ɗ/ and [t̪, t̪ʰ, ɗ̪] involves shifting the location of primary constriction from the alveolar ridge to the back of upper incisor. As such, this allophonic process can be expressed as dentalization, which can be characterized using the distinctive feature [-distributed] (Kochetov 2011). Likewise, the three alveolar plosives that participate in this dentalization process can be grouped as a natural class using the distinctive features [+alveolar; -strident]. Correspondingly, this palatal feature-induced dentalization can be formally expressed using Rule (1) as shown below.

| Dentalization of alveolar plosives |

| C [+alveolar; −strident] → C [−distributed]/_[+palatal] |

(b) Alveolar affricates /ts/ and /tsʰ/ and fricatives /s/ and /z/ are found to surface as alveolar-palatal sounds [tɕ], [tɕʰ], [ɕ], and [ʝ], respectively, in this palatal context. For example, the morpheme /tsi22/ ‘potato’ is pronounced [tɕi22], and the morpheme /zi/ ‘press’ is produced as [ʑi22] in utterances. This can be justified by speakers’ articulatory gesture. They are observed moving their tongue backward to the hard palate to create constriction, rather than maintaining their tongue around the alveolar ridge. As can be seen this alternation between /ts, tsʰ, s, z/ and [tɕ, tɕʰ, ɕ, ʝ] involves shifting the primary place of constriction from the alveolar ridge to the hard palate. As such, this process can be considered as alveolar palatalization and can be interpreted using the feature [-anterior]. The four alveolar affricates and fricatives can also be grouped as a natural class using the distinctive features [+alveolar; +continuous; +anterior]. Correspondingly, the whole alternation can be expressed using Rule (2), as shown below.

| Alveolar palatalization of alveolar affricates and fricatives |

| C [+alveolar; +continuous; +anterior] → C [−anterior]/_[+palatal] |

(c) Onset phonemes that have a place of articulation after the alveolar ridge, like /k/, /kʰ/, /ɠ/, /ħ/, and /ʔ/, are found to undergo palatalization and surface as [kj], [kʰj], [ɠj], [ħj], and [ʔj], respectively, before the high front vowel /i/, and palatal glide /j/. Because native speakers move their tongue forward to the hard palate, but do not arrive the hard palate. For example, the morpheme /ki22/ ‘flag’ is pronounced as [kʲi22], and the morpheme /ħi22/ ‘fish’ is uttered as [ħji22] ‘fish’ by native speakers. As can be seen, this alternation between /k, kʰ, ɠ, ħ, ʔ/ and [kj, kʰj, ɠj, ħj, ʔj] does not involve shifting the primary place of articulation of related onset consonants, as found in other processes on alveolar onsets, but rather, they acquire a secondary articulation of palatalization because of the [+palatal] feature from their subsequent sounds. As such, the alternation can be characterized as palatalization using the feature [+palatal], and the five phonemes can be grouped as a natural class using the features [−bilabial; −alveolar]. Corresponding, the whole alternation can be expressed using Rule (3), as shown below.

| Palatalization of non-labial and non-alveolar onsets |

| C [−bilabial; −alveolar] → C [+palatal]/_[+palatal] |

As discussed above, all onset phonemes, except labial plosives /p, pʰ, ɓ/, are easily affected by the palatal feature from their subsequent sounds and change their forms at the surface level. Labial onsets are exceptional to an alternation in this context, and this may be ascribed to their different articulator at lips, while the palatal-inducing process dominantly affects the tongue, as generalized by Gordon (2016), based on the 100-language WALS sample. In addition, it can be observed that, the alternations with alveolar onsets exclusively involve shifting the location of the primary constriction to either before the alveolar ridge as in dentalization for alveolar plosives /t, tʰ, ɗ / or after the alveolar ridge as in the alveolar palatalization for alveolar affricates and fricatives /ts, tsʰ, s, z/. In contrary, the alternations with onsets that are non-labial and non-alveolar exclusively involve superimpositions of a secondary gesture of palatalization. As such, it can be generalized that, the impact of the palatal feature from vocalic sounds on syllable onsets is asymmetrical in this language, and this is dominantly determined by the place of articulation of target onsets at the underlying level. There appears to be a tendency that alveolar sounds are more likely to be affected by the palatal nature of surrounding sounds and are more likely to shift their primary place of constriction because of the impact.

4.2 Labial-conditioned variation

The high back round vowel /u/ and the labial-velar glide /w/ appear to be the most active to trigger allophonic variations on onsets of Zhangzhou. The trigger can be further specified as [+labial], which is discovered impacting syllable onsets of this language in six different ways, depending on the nature of target onsets. This is generalized in Table 8.

labial feature-induced variation on Zhangzhou onsets.

| Process | Onset | Before [u] | Before [w] |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) lenition, labialization | /ɓ/ | [βu33] ‘frost’ | [βwi35] ‘smile’ |

| /ɠ/ | [ɣʷu22] ‘cow’ | [ɣʷwɐ51] ‘I’ | |

| (b) lenition, laminalization, labialization | /ɗ/ | [lʷu51] ‘female’ | [lʷwɐ22] ‘spicy’ |

| (c) laminalization, labialization | /t/ | [t̻ʷu35] ‘pile, heap’ | [t̻ʷwɐ41] ‘belt’ |

| /tʰ/ | [t̻ʰʷu41] ‘to shovel’ | [t̻ʰʷwɐ35] ‘drag’ | |

| (d) alveolar-palatalization, labialization | /s/ | [ʃʷu22] ‘word’ | [ʃʷwɐ35] ‘sand’ |

| /z/ | [ʒʷu22] ‘such as’ | [ʒʷwɐ22] ‘hot’ | |

| /ts/ | [tʃʷu22] ‘merciful’ | [tʃʷwɐ51] ‘paper’ | |

| /tsʰ/ | [tʃʰʷu33] ‘slippery’ | [tʃʰʷwi41] ‘mouth’ | |

| (e) glottalization, labialization | /ħ/ | [hʷu22] ‘help’ | [hʷwɐ35] ‘flower’ |

| (f) labialization | /k/ | [kʷu35] ‘beetle’ | [kʷwɐ35] ‘song’ |

| /kʰ/ | [kʰʷu35] ‘human body’ | [kʰʷwɐ35] ‘boast’ | |

| /ʔ/ | [ʔʷu33] ‘have’ | [ʔʷwɐ35] ‘a branch of plant’ |

(a) All onset phonemes surface a labial feature before the vowel /u/ or the labial glide /w/. This is because native speakers are found rounding their lips over their articulation of any onset consonant in this labial environment, such as the morpheme /ku35/ ‘beetle’ is pronounced as [kʷu35], the morpheme /kʰwɐ35/ ‘boast’ is produced as [kʰʷwɐ35], and the morpheme /ʔu33/ ‘have’ is uttered as [ʔʷu33] by speakers. This phenomenon is articulatorily understandable and is phonologically predictable, because it is a natural process for onset consonants to acquire a secondary articulation of labialization due to the labial nature of their immediately subsequent sounds. As such, the alternation can be characterized as labialization and expressed using the Rule (4), as shown below. It should be noted that, the three labial plosives are already characteristic of the [+labial] feature themselves. It is thus redundant to impose a labialization effect on their surface form.

| Labialization of onset phonemes |

| C → C [+labial]/_[+labial] |

(b) The labial implosive /ɓ/ and the velar implosive /ɠ/ are found to separately become a labial voiced fricative [β] and a labialized velar voiced fricative [ɣʷ] in this labial context. Because no complete constriction can be observed from speakers’ articulatory gesture, and the airflow from their lungs can be continuously perceived over the production of related tokens. Such as the morpheme /ɓu33/ ‘frost’ is pronounced as [βu33], and the morpheme /ɠu22/ ‘cow’ is produced as [ɣʷu22] by speakers. As can be seen, the alternation between /ɓ, ɠ/ and voiced [β, ɣʷ] involves shifting the airstream mechanism from glottalic ingressive to pulmonic egressive and changing the manner of articulation from implosive to fricative. As such, this process can be considered as lenition, which is also known as spirantization or fricativization in literature (Gordon 2016; Kennedy 2016). In addition, the voiced velar onset acquires the labial feature as a secondary feature from its immediately subsequent sound. In other words, there are two different processes of lenition and labialization occurring on non-alveolar implosive onsets. As such, the lenition process can be characterized using the distinctive features [+continuous; +strident], and the labial and velar implosives /ɓ, ɠ/ can be grouped as a natural class using the features [−alveolar; −strident; +voiced], while the whole alternation can be formally expressed using Rule (5), shown below.

| Lenition and labialization of non-alveolar implosives |

| C [−alveolar; −strident; +voiced] |

| → C [+labial; +continuous; +strident]/_[+labial] |

(c) The alveolar implosive /ɗ/ is observed to surface as a labialized approximant [lʷ] before the labial segments /u/ or /w/. For example, the morpheme /ɗu51/ ‘female’ is produced as [lʷu5], and the morpheme /ɗwɐ22/ ‘spicy’ is uttered as [lʷwɐ22] by speakers. This occurs because speakers move the central part of their tongue, rather than the tongue tip, nearly approaching but not touching the alveolar ridge to form a constriction that is slightly wider than the constriction needed for fricative sounds. Meanwhile, the airflow can be continually perceived passing through the constriction, while speakers’ lips are rounded over the production. As can be seen, the alternation between /ɗ/ and [lʷ] involves shifting the airstream mechanism from glottalic ingressive to pulmonic egressive, altering the manner of articulation from plosive to approximant, changing the active articulator from the tongue tip to the central part of the tongue, and acquiring a secondary articulation of labialization from subsequent sounds. The allophonic alternation of this alveolar implosive in this labial context can thus be considered as a compounding effect of lenition, laminalization, and labialization, and can be formally expressed using Rule (6), as shown below.

| Lenition, laminalization, and labialization of alveolar implosive |

| /ɗ/→[lʷ]/_[+labial] |

(d) The voiceless alveolar plosives /t/ and /tʰ/ are observed to separately surface as [t̻ʷ] and [t̻ʰʷ] in this labial context. This is because native speakers raise up their tongue blade, rather than their tongue tip, to form an oral obstruction at the alveolar ridge, while their lips are rounded over the production. For example, the morpheme /tu35/ ‘pile, heap’ is pronounced as [t̻ʷu35], while the morpheme [tʰu41] ‘to shovel’ is produced as [t̻ʰʷu41] by speakers. As can be seen, the alternation between /t, tʰ/ and [t̻ʷ, t̻ʰʷ] mainly involves shifting the active articulator from the tongue tip to the tongue blade and acquiring a secondary articulation of labialization. The alternation can thus be considered as a compounding effect of laminalization and labialization, which can be characterized using the features [+laminal; +labial]. The two alveolar plosives /t/ and /tʰ/ can also be grouped as a natural class of the [+alveolar; −voiced; −continuous] features. Correspondingly, their allophonic alternation in this labial context can be formally expressed using Rule (7), as shown below.

| Laminalization and labialization of alveolar voiceless plosives |

| C [+alveolar; −voiced; −continuous] |

| → C [+labial; +laminal]/_[+labial] |

(e) The alveolar fricatives /s/ and /z/ and affricates /ts/ and /tsʰ/ are found to surface as palatal-alveolar sounds [ʃʷ], [ʒʷ], [tʃʷ], and [tʃʰʷ], respectively, in this labial setting. This is because speakers are observed to move their tongue body from the alveolar ridge towards the hard palate to form a constriction, while rounding their lips. For example, they produce the morpheme /su22/ ‘word’ as [ʃʷu22] and the morpheme /zu22/ ‘such as’ as [ʒʷu22]. As can be seen, the alternation between /s, z, ts, tsʰ/ and [ʃʷ, ʒʷ, tʃʷ, tʃʰʷ] involves shifting the location of primary constriction from the alveolar ridge to palatal-alveolar and acquiring a secondary articulation of labialization. The alternation can thus be considered as a compounding effect of alveolar-palatalization and labialization and can be interpreted as [−anterior; +labial]. The four alveolar onsets /s, z, ts, tsʰ / can be grouped as a natural class for sharing distinctive features [+alveolar; +distributed; +strident]. As such, their allophonic alternation can be expressed using Rule (8), as shown below.

| Alveolar-palatalization and labialization of alveolar non-plosive onsets |

| C [+alveolar; +distributed; +strident] |

| → C [−anterior]/_[+labial] |

(f) The pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ is found to surface as a labialized glottal fricative [hʷ] before the labial segment /u/ or /w/. This is because speakers reported they made a partial constriction at the glottis, rather than in the pharyngeal cavity, while rounding their lips over the production of related tokens. For example, they produce the morpheme /ħu22/ ‘help’ as [hʷu22], and the morpheme /ħwɐ35/ ‘flower’ as [hʷwɐ35]. As can be seen, the alternation between /ħ/ and [hʷ] involves shifting the location of primary constriction from the pharyngeal cavity to the glottis and acquiring a secondary articulation of labialization. The allophonic alternation of this onset can thus be considered as a compounding effect of glottalization and labialization, and can be expressed using Rule (9), as shown below.

| Glotalization and labialization of pharyngeal fricative |

| /ħ/→[hʷ]/_[+labial]. |

As discussed above, the allophonic alternations of syllable onsets in this language are much more complex in the labial context than in the palatal context. It can be observed that the labial-inducing impacts on onset phonemes are diverse, which include (a) changing the airstream mechanism, such as from the glottalic ingressive to pulmonic egressive as found in implosive onsets; (b) changing the manner of articulation, such as from implosive to fricative as found in /ɓ, ɠ/, or from implosive to approximant as found in /ɗ/; (c) shifting the active articulator, such as from the tongue tip to the central part of the tongue as found in /ɗ/, and from the tongue tip to the tongue blade as found in /t, tʰ/; (d) shifting the location of primary constriction, such as from alveolar ridge to palatal-alveolar as found in /s, z, ts, tsʰ/, and from the pharyngeal cavity to the glottis as found in /ħ/; and (e) acquiring a secondary articulation of labialization as found in all onsets except the labial plosives, because they have already had the labial feature on their own. Likewise, the types of allophonic processes are also diverse, which include labialization, lenition, laminalization, alveolar-palatalization, and glottalization. In addition, the allophonic processes mostly do not operate on their own, instead, they compound with other process (es) to impact the surface forms of target onsets. For example, the alternation between the alveolar implosive /ɗ/ and the labialized approximant [lʷ] involves lenition, laminalization, and labialization. In general, except the voiceless labial plosives, the two voiceless velar plosives /k, kʰ/ are the least affected in the labial context, because their alternation only involves acquiring a secondary articulation of labialization.

4.3 Nasality-conditioned variation

The nasal vowels /Ṽ/and syllabic nasals /N̩/ can also induce allophonic alternations on onset phonemes of this language. The trigger can be specified as the [+nasal] feature as shared by these two types of nuclei. The alternations mainly manifest in three different ways, depending on the nature of target onsets. This is generalized in Table 9, in which the symbol * indicates no empirical data were tested in the field.

Nasal feature-induced variation on Zhangzhou onsets.

| Process | Onset | Before [Ṽ] | Before [ N̩] |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) nasalization | /ɓ/ | [mɛ̃33] ‘scold’ | * |

| /ɗ/ | [nɔ̃33] ‘two’ | * | |

| /ɠ/ | [ŋɛ̃33] ‘hard’ | * | |

| (b) glottalization, voicing, pre-nasalization | /ħ/ | [nɦɛ̃41] ‘rest’ | [mɦm̩41] ‘hit with a stick’ |

| [nɦɐ̃41] ‘scorching’ | [ŋɦŋ̩35] ‘recipe’ | ||

| (c) pre-nasalization | /p/ | [mpĩ33] ‘weave’ | [mpŋ̩51] ‘board, list’ |

| /pʰ/ | [mpʰĩ41] ‘slide’ | [mpʰŋ̩41] ‘high tide’ | |

| /t/ | [ntɛ̃33] ‘press’ | [n tŋ̩22] ‘long’ | |

| /tʰ/ | [ntʰɛ̃41] ‘lift up’ | [ntʰŋ̩22] ‘sugar’ | |

| /k/ | [ŋkɐ̃51] ‘dare’ | [ŋkŋ̩35] ‘vat’ | |

| /kʰ/ | [ŋkʰɛ̃35] ‘hollow’ | [ŋkʰŋ̩41] ‘hid’ | |

| /ts/ | [ntsɛ̃35] ‘compete’ | [ntsŋ̩35] ‘dress’ | |

| /tsʰ/ | [ntsʰɛ̃35] ‘star’ | [ntsʰŋ̩35] ‘warehouse’ | |

| /s/ | [nsɐ̃35] ‘three’ | [nsŋ̩35] ‘frost’ | |

| /z/ | * | * | |

| /ʔ/ | [nʔĩ35] ‘sleep’ | [mʔm22] ‘berry’ | |

| [nʔɛ̃35] ‘infant’ | [ŋʔŋ̩35] ‘central’ |

(a) Implosive onsets /ɓ/, /ɗ/, and /ɠ/ are observed to surface as their corresponding homorganic nasal plosives [m], [n], and [ŋ], respectively, in a nasal context. Because speakers are found to release the airflow through their nose, rather than through their mouth, when they produce these onsets before nasal vowels. For example, they pronounce the morpheme /ɓĩ33/ ‘noodle’ as [mĩ33], and the morpheme /ɗɔ̃33/ ‘two’ as [nɔ̃33]. It should be also noted that implosive onsets are not attested to occur before syllabic nasals in this language. As can be seen, the alternation between /ɓ, ɗ, ɠ/ and [m, n, ŋ] involves shifting the manner of articulation from oral to nasal. It thus can be considered as an effect of nasalization. The three implosive onsets can be grouped as a natural class, using the features [+voiced; -strident] and the nasalization process can be formally expressed using Rule (10).

| Nasalization of implosive onsets |

| C [+voiced; −strident] → [+nasal]/_[+nasal] |

(b) The pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ is observed to surface as a prenasalized breathy onset with three different forms that include [mɦ], [nɦ], [ŋɦ], depending on the nature of its subsequent nasal segments. This occurs because speakers reported they moved a constriction from the pharynx to the larynx where they continuously generated airflow from lungs and let them freely pass through their vocal tract. They also reported before the articulation of this onset, their velum had already been lowered as that the airflow could also rush out through their nose. For example, they produce the morpheme /ħɛ̃41/ ‘rest’ as [nɦɛ̃41], the morpheme /ħm̩41/ ‘beat’ as [mɦm41], and the morpheme /ɦŋ̩35/ ‘recipe’ as [ŋɦŋ̩35]. As can be seen, the alternation between the pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ to three forms of prenasalized breathy onset [mɦ, nɦ, ŋɦ] involves shifting the location of primary constriction from pharynx to larynx, creating voicing for the airflow, and acquiring an articulatory gesture of nasalization before onsets. The alternation can thus be considered as a compounding effect of glottalization, voicing, and pre-nasalization. The three surface forms differ in the place where a constriction is created in the oral cavity for the articulation of subsequent nasal sounds. Specifically, the form [mɦ] occurs before the labial syllabic nasal, the form [nɦ] occurs before nasal vowel, while the form [ŋɦ] occurs before the velar syllabic nasal. As such, the allophonic alternations of this onset can be formally expressed using Rule (11).

| Glottalization, voicing, pre-nasalization of pharyngal fricative |

| /ħ/ → N[ɦ]/_[+nasal] |

(c) All other onsets that are non-voiced and non-pharyngal are found to surface a nasal feature in this nasal context. This is because before the articulation of onset consonants, speakers are observed to lower their velum and get an articulatory gesture ready for a nasal production. For example, they produce the morpheme /tɛ̃33/ ‘press’ as [ntɛ̃33], the morpheme /pĩ 35/ ‘weave’ as [mpĩ33], and the morpheme /kɐ̃51/ ‘dare’ as [ŋkɐ̃51]. As can be seen, the alternation involves acquiring an additional articulatory gesture of nasalization before onset articulation and assimilating the place of nasal articulation to that of the target onset. For example, the alveolar plosive /t/ surfaces as [nt], the labial plosive /p/ surfaces as [mp], and the velar plosive /k/ surfaces as [ŋk]. As such, the alternation can be considered as a prenasalization as an impact of the nasal feature from subsequent nasal vowels and syllabic nasals. It can be expressed formally using Rule (12).

| Pre-nasalization of non-voiced and non-pharyngal onsets |

| C [−voiced; −pharyngal] → NC/_[+nasal] |

As discussed in this section, the allophonic alternations of syllable onsets are incredibly active in this language. Twelve different types of alternation processes are generalized from empirical data and are formally expressed using rules within the paradigm of generative phonology. They manifest varying impacts of featural properties of triggers from the vocalic segments, but also reflect varying reactions of onset phonemes in different phonological environments. In general, the labial-inducing alternations are much more complex and diverse that account for half of the total alternation types and involve changing the airstream mechanism, manner of articulation, active articulator, the location of primary constriction, and acquiring a secondary articulation. In most cases, the individual process compounds with other process(es) to impact the surface of onsets. The nasal-inducing alternations are less complex that involve changing the manner of articulation from oral to nasal, shifting the location of primary constriction, and generating pre-nasalization. However, the nasal-inducing alternations can cause certain onsets to have more than one surface form, for example, the pharyngal fricative onset /ħ/ has three surface forms [mɦ], [nɦ], and [ŋɦ], so does the glottal stop with three variants [mʔ], [nʔ], and [ŋʔ]. The palatal-inducing alternations seem the least complex that mainly involve shifting the location of primary constriction on alveolar onsets or acquiring a secondary articulation of palatalization on velar onsets, while labial onsets are not affected in the palatal context.

As for the onset phonemes, they suffer varying impacts from their immediately subsequent sounds. Alveolar and velar onsets, except the voiced fricative /z/, have four surface forms; the pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ and the glottal stop /ʔ/ both have as many as six variants at the output; the labial implosive /ɓ/ has three forms while the other two voiceless labial plosives only have two surface forms. This suggests that the voiceless labial stops are the least affected by their subsequent sounds, while onsets with a place of articulation outside the oral cavity are the most valuable to the featural properties of their subsequent sounds. In addition, voiced onsets are more likely to change the manner of articulation as an impact of their following segments, while voiceless onsets have different reactions. In general, voiceless alveolar onsets are more likely to shift the location of primary constriction, change an active articulator, and/or acquire an additional secondary feature, while voiceless velar onsets largely involve acquiring a secondary feature of articulation. Voiceless labial onsets are the least easy to be affected but if yes, they only involve acquire an additional secondary feature. As indicated, the featural impacts of vocalic segments appear to be most severe on alveolar sounds that involve the engagement of the front of the tongue in this language. This tends to be a cross-linguistic tendency, as Gordon (2016) observed among 100-language WALS sample. It may be ascribed to the fact that the front of tongue executes faster gestures than both dorsum and lips, as such it is more prone to be overlapped by surrounding sounds (Gordon 2016).

5 Phonotactic constraints of Zhangzhou onsets

Each language has an inventory of phonemes that undoubtedly forms an essential part of its phonology. Several phonological databases have been developed, as introduced in Section 1, to compile commensuration data on phoneme inventories of consonants and vowels and their phonological traits for a relatively large and diverse sample of languages, while some may also cover tonemic inventory, and possible forms of syllable onset, nucleus, and coda as shown in the Phonotacticon 1.0 (Joo and Hsu 2025) for 516 lects spoken in the Eurasian macro area. However, those established phonological databases and most descriptive phonological work of natural languages are limited in providing systematic information on encoding the frequency behaviours and distributional characteristics of individual phonemes, and the constraints on their occurrence and combinability with other phonemes within specific entities, although few quantitative research can be found in literature. For example, Hayes and Wilson (2008) advocate using a maximum entropy model, also known as the UCLA Phonotactic Learner, to characterize the grammatical knowledge that permits native speakers to make phototactically well-formed judgements. In this model, the well-formedness is interpreted as probability, and an infinite set Ω consisting of all universally possible Ω phonological surface forms are supposed to be stated in the chosen representative vocabulary. As a cross-linguistic phenomenon, constraints are supposed to occur on the onset system of Zhangzhou Southern Min. This is because phonemes of a given language are not equally active in the construction of linguistic entities, like syllables, morphemes and words. Likewise, phonemes of any language cannot randomly combine with each other to make lexical distinctions. As such, within a wider set of phonological patterns, there are constraints, known as phonotactics, governing their distribution, relative frequency, and inter-relationship with other phonemes within the same constituents (cf. Algeo 1975; Celata and Calderone 2015; Duanmu 2003; Gordon 2016; Joo and Hsu 2024; Kennedy 2016; Kirby and Yu 2007; Maddieson 2023; Pearce 2007; Zec 1995; Zhang 2006).

This section will systematically explore this issue by examining the usage frequency of individual syllable onsets in this language, and the phonotactic constraints on their co-occurrences with other syllable components, tones and finals in particular, in the formation of monosyllabic morphemes. It will fill the research gap in conducting an in-depth analysis of phonotactics in a specific language and will provide new insight and methodology to understand how phonemes are utilized for constructing linguistic entities, like syllables and morphemes; how phonemes are distributed in relation to one other; how phonemes can be combined with other phonemes in a system, and how the occurrence of phonemes may be constrained. Differing from Hayes and Wilson’s model, the phonotactic constraints in this study are not assigned with probabilities and are not calculated from their constraint violations and the weights, instead, their analyses are based on the gap between the theoretically assumed number and the exact number that is obtained in the real world. In addition, this study does not use marked constraints to assess forms for their phonotactic legality, instead, it exhaustively examines all possible combinations of individual onset phonemes and other syllable components, finals and tones in particular, to assess their capability to generate linguistic entities of syllables and monosyllabic morphemes that are empirically used in the speech community. It is hopped the descriptive analysis can stretch our knowledge of the phonological patterns of the onset system in this language and contribute to the understanding of phonotactics as an important phenomenon in human languages. It is also hopped that it can provide a well-established dataset to examine the phonotactic grammar of Southern Min onsets using other quantitative methods, such as Hayes and Wilson’s model.

5.1 Usage frequency of Zhangzhou onsets

Tracing back to the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD), Chinese scholars had devised the method of Fanqian to document the pronunciation of Chinese Characters, which were monosyllabic, through using two other characters (Dong 2023). The first character represents the initial of the character being referred, which corresponds to a syllable onset in modern linguistics, while the second character represents its final, which refers to the constituent that covers all syllable components except onset. In other words, within the Sinitic convention, individual syllables have long been considered to incorporate two parts of Initial and Final (Dong 2023; Duanmu 1990, 1999; Huang 2021; Li and Yao 2008; Třísková 2011; Zhang 2006). This fanqie approach has thereafter been prevalent as an effective tool to indicate speech sounds of Chinese languages over history. During the Six Dynasties period (220–589 AD), a series of rhyme dictionaries were compiled using this method, such as Lu Fayan’s Qieyun, which are regarded as the earliest and most direct reference to the study of the phonological system of the Early Middle Chinese and above (Dong 2023). In these dictionaries, each rhyme can be seen as a range of rhyming characters for poetry and prose compositions, and characters sharing the same pronunciation are listed together. As such, rhyme dictionaries contain all possible characters being practically used. For example, there are about 12,000 characters in Lu Fayan’s rhyme book Qieyun. They also contain the maximum types of initials and finals, as well as their combinations to formulate monosyllabic characters.

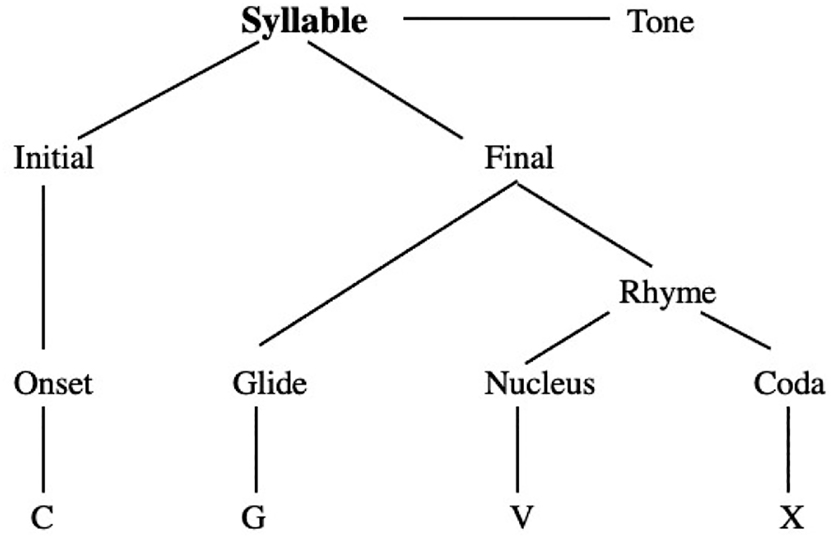

This study adopts the Sinitic convention of syllabification and rhyme dictionary to examine the phonotactics of syllable onsets in Southern Min. Each syllable is divided into two parts of Initial that corresponds to onset and Final that covers all other syllable components. This is hierarchically represented in Figure 4. In total, 15 syllable onsets (initials) are contrastive, as described in Section 3. Likewise, 61 finals can be generalized from the empirical data, as summarized in Table 10 with examples. They can be four types: V, GV, VX, and GVX, in which V covers oral vowels, nasal vowels, and syllabic nasals, while X covers nasal codas, obstruent codas and glide codas. The 15 onsets and 61 finals will serve as an important base to explore how the onset phonemes of this language are distributed in relation to different finals (or final types), and how their combinations may be constrained at the syllable level.

Syllable modelling in this study.

Examples of finals in Zhangzhou.

| Types | Onset | Examples | Types | Examples | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V | /e/ | ke41‘calculate; plan’ | VX | /iŋ/ | kiŋ41‘respect’ |

| /i/ | ki41‘remember’ | /ɔŋ/ | kɔŋ41‘tribute’ | ||

| /u/ | ku41‘sentence’ | /ɐw/ | kɐw41‘enough’ | ||

| /ɔ/ | kɔ41‘look after’ | /ɐ̃w/ | ɠɐ̃w33‘root of lotus’ | ||

| /ɛ/ | kɛ41‘frame; shelf’ | /ɐj/ | kɐj41‘boundary’ | ||

| /ɵ/ | kɵ41‘tell; sue’ | /ɐ̃j/ | kɐ̃j41‘how about’ | ||

| /ɐ̃/ | kɐ̃41‘yeast’ | /ɐp/ | kɐp41‘pigeon’ | ||

| /ĩ/ | kĩ41‘see; meet’ | /ip/ | kip41‘anxious; urgent’ | ||

| /ɔ̃/ | ɓɔ̃41‘emit; pop up’ | /ɔp/ | ħɔp41‘catch with a cover’ | ||

| /ɛ̃/ | kɛ̃41‘quantifier for machine’ | /ɐt/ | kɐt41‘tie; knot’ | ||

| /m̩/ | ʔm̩41‘oh; all right’ | /it/ | kit41‘orange’ | ||

| /ŋ̩/ | kŋ̩41‘steel’ | /ut/ | kut41‘bone’ | ||

| GV | /jɐ/ | kjɐ41‘post’ | /ɐk/ | kɐk41‘horn; angle’ | |

| /ju/ | kju41‘save; rescue’ | /ik/ | kik41‘leather; transform’ | ||

| /jɔ/ | ħjɔ41‘yes’ | GVX | /ɔk/ | kɔk41‘country; nation’ | |

| /jɵ/ | kjɵ41‘call; order’ | /jɐw/ | kjɐw41‘seize; hand over’ | ||

| /jɐ̃/ | kjɐ̃41‘mirror; glass’ | /jɐ̃w/ | ɠjɐ̃w41‘stingy’ | ||

| /jɔ̃/ | tsjɔ̃41‘dipping sauce’ | /wɐj/ | kwɐj41‘strange; to blame’ | ||

| /jũ/ | ɗjũ51‘turn; tweak’ | /wɐ̃j/ | ʔwɐ̃j51‘sprain; wrench’ | ||

| /wɐ/ | kwɐ41‘hang’ | /jɐm/ | kjɐm41‘sword’ | ||

| /we/ | kwe41‘pass through’ | /jɐn/ | kjɐn41‘build; found’ | ||

| /wi/ | kwi41‘expensive’ | /jɐŋ/ | kʰjɐŋ41‘capable; competent’ | ||

| /wɐ̃/ | kʰwɐ̃41‘look; see’ | /jɔŋ/ | kjɔŋ51‘arch’ | ||

| /wĩ/ | kwĩ41‘volume’ | /wɐn/ | kwɐn41‘be used to’ | ||

| VX | /ɐm/ | kɐm41‘supervise’ | /jɐp/ | kjɐp41‘take by force’ | |

| /im/ | kim41‘prohibit’ | /jɐt/ | kjɐt41‘bear fruit; connect’ | ||

| /ɔm/ | ɗɔm41‘sloshy; muddy’ | /jɐk/ | kjɐk41‘screech’ | ||

| /ɐn/ | kɐn41‘separate’ | /jɔk/ | kjɔk41 ‘chrysanthemum’ | ||

| /in/ | kin41‘strength’ | /wɐt/ | kwɐt41 ‘determine’ | ||

| /un/ | kun41‘stick’ |

The phonotactic exploration in this study is data driven. It is built upon 61 rhyme tables that Huang (2019) adopts the conventional notion of rhyme dictionary to tabulate combinations of individual onsets, finals, and tones to generate syllables in this language. Table 11 illustrates the rhyme table under the final /ɐ/, while Table 12 illustrate the rhyme table under the final /ɐ̃w/. The top row indicates the final being addressed; the second rows list the eight tones in sequence while the leftmost column lists the 15 onset phonemes. Each slot in the table represents a combination of an onset, a final, and a tone to generate a syllable in this language. If a syllable is empirically attested, a represented character is put in that correspondingly represents one or more monosyllabic morpheme(s). For example, the syllable /kɐ35/ in Table 11 is attested because it can generate lexical morphemes like ‘glue’ in Chinese character 胶 ( jiāo ). Likewise, the syllable /ɓɐ̃w33/ in Table 12 can generate a lexical morpheme like ‘appearance’ in Chinese character 貌 ( mào ). In contrast, if a slot is left empty, indicating that its related syllable is theoretically possible to occur, but it is not attested in the field. For example, the syllable /kɐ22/ is not attested, because it is not related to any of morphemes in this language.

Rhyme table of the final /ɐ/ in Zhangzhou.

| Onset | T1 [35] | T2 [22] | T3 [51] | T4 [41] | T5 [33] | T6 [41] | T7 [221] | T8 [22] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | 巴 ‘tailor’ | 饱2 ‘full; not hungry’ | 霸 ‘overlord; bully’ | |||||

| pʰ | 脬 ‘bladder; sponge’ | 拍 ‘beat; hit’ | 泡2肿水泡 ‘blister’ | |||||

| ɓ | 疤2 ‘quantifier for bump’ | 麻2 ‘numb’ | 肉2 ‘meat’ | 密2紧紧 ‘close’ | 觅2 ‘seek; look for’ | |||

| t | 焦2 ‘withered; dry; burnt; fragile’ | ◯婴儿吃 ‘(infant) eat’ | 搭2 ‘put up; travel by’ | 踏2 ‘step on; trample’ | ||||

| tʰ | 塔 ‘tower; pagoda’ | 叠2 ‘pile up’ | ||||||

| ɗ | 拉 ‘pull’ | 蜊 ‘clam’ | 邋 ‘sloppy; dowdy’ | ◯搅动 ‘stir’ | 蜡 ‘wax’ | |||

| k | 胶 ‘glue’ | 绞 ‘twist; wring’ | 教2 ‘teach’ | 咬 ‘bite’ | ||||

| kʰ | 脚 ‘foot’ | 卡2 ‘card’ | 敲2 ‘knock’ | |||||

| ɠ | 牙2败牙; 螺丝牙 ‘screw thread’ | |||||||

| ts | 查2查甫; 查某 ‘bound morpheme for man and woman’ | 早 ‘early; long ago’ | 扎2携带; 提 ‘bring along; pull out; tie’ | 闸 ‘brake; gear; penstock’ | ||||

| tsʰ | 差2 ‘difference; weak’ | 柴 ‘firewood’ | 吵 ‘noisy; wrangle’ | 插2 ‘insert’ | ||||

| s | 捎 ‘grasp; take along’ | 傻 ‘foolish’ | 洒 ‘sprinkle’ | 煠沸水快煮 ‘cook in boiled water’ | ||||

| z | ||||||||

| ħ | 哈 ‘sound of laughter’ | 孝2 ‘filial piety’ | ||||||

| ʔ | 鸦 ‘crow’ | 仔 ‘nominative and diminutive suffix’ | 鸭 ‘duck’ | 盒 ‘small box or base’ |

Rhyme table of the final /ɐ̃w/ in Zhangzhou.

| Onset | T1 [35] | T2 [22] | T3 [51] | T4 [41] | T5 [33] | T6 [41] | T7 [221] | T8 [22] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | ||||||||

| pʰ | ||||||||

| ɓ | 茅 ‘reeds’ |

◯牙齿脱落; 说话跑气 ‘speak indistinctly for missing teeth’ | 貌 ‘appearance’ | |||||

| t | ||||||||

| tʰ | ||||||||

| ɗ | 脑 ‘brain’ | 闹2 ‘noisy’ | ||||||

| k | ||||||||

| kʰ | ◯啃东西的声音 ‘gnawing sound’ | |||||||

| ɠ | 熬2 ‘stew’ | 藕 ‘root of lotus’ | ◯吠叫 ‘bark’ | |||||

| ts | ||||||||

| tsʰ | ||||||||

| s | ||||||||

| z | ||||||||

| ħ | ◯芋头没煮熟; 口感不佳 ‘flavour of undercooked taro’ | |||||||

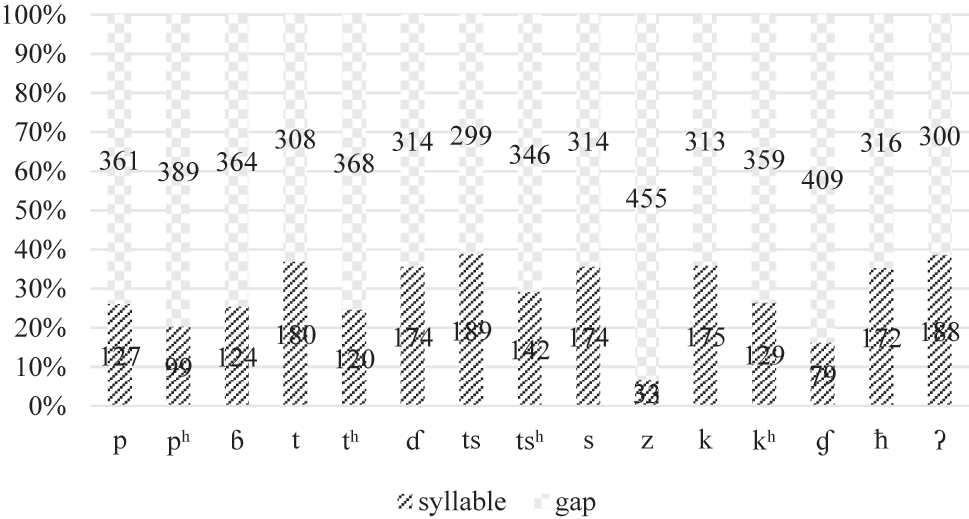

| ʔ | ◯说话支支吾吾 ‘hum and haw’ |