Abstract

This study investigates the diachronic semantic evolution of the Chinese character jie (解) guided by dynamic categorization theory. It aims to trace the pathway from a concrete action verb to a modal auxiliary and to identify the cognitive mechanisms that drive each stage. Methodologically, this research adopts a diachronic and qualitative analysis using three tagged sub-corpora of the Academia Sinica Ancient Chinese Corpus. The findings reveal that jie follows three stages of dynamic categorization: (1) it underwent conservative gradual change within its category, driven by the base/profile mechanism; (2) it extended across similar or adjacent categories via metaphor and metonymy, shifting from physical actions to abstract concepts; (3) it experienced decategorization driven by metaphor and metonymy, grammaticalizing into an auxiliary verb expressing ability, possibility, and inevitability. The study concludes that dynamic categorization theory provides a robust framework for explaining the full semantic trajectory of jie, demonstrating its explanatory power beyond classical and prototype theories. This study not only illuminates the dynamic nature of Chinese lexical semantics but also offers theoretical insights for future research on semantic evolution.

1 Introduction

As a critical tool for human communication, language undergoes continuous evolution. Word meanings change to reflect users’ deepening cognition of the world and language’s dynamic adaptation to shifting social contexts (Johnson 1987; Lakoff 1987; Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Zeng and Wen 2025). This process of change is reflected in the continual reorganization of semantic categories, which structure the mental lexicon (Lakoff 1987; Rosch 1973, 1975). Within cognitive linguistics, categorization theory serves as a framework for investigating word meaning. Critically, semantic categories are not static. As Wen and Yang (2022) emphasize, the dynamic evolution of categories results from interactions between internal category factors and language users. Such interactional dynamics challenge the adequacy of earlier static theories, namely classical and prototype theories, and necessitate a more dynamic theoretical framework. To capture this dynamic nature of meaning, the focus of cognitive linguistics has shifted from classical and prototype categorization theories toward dynamic categorization, which emphasizes the diachronic evolution of semantic categories across historical periods.

The Chinese character jie (解) serves as a prototypical example of polysemy, exhibiting an extensive range of semantic changes across historical periods. Its meanings encompass diverse domains, from physically unbinding objects to abstract notions of comprehension and interpretation. Previous studies have revealed that the meanings of jie have continuously expanded and become more abstract, gradually transcending their original physical domains into deeper cognitive and psychological spheres (Fan 2022; Jiang 2007; Yang 2001). However, these studies have neither systematically explained the cognitive mechanisms driving this trajectory nor integrated their findings within a unified theoretical framework. This study seeks to fill these gaps by applying dynamic categorization theory to systematically trace the diachronic semantic trajectory of jie and explore its intra- and inter-categorical dynamic development. Specifically, we seek to address the following research questions: (1) What dynamic categorization stages has the Chinese character jie undergone in its semantic evolution? (2) What mechanisms facilitate the semantic extensions of the Chinese character jie? (3) How can dynamic categorization theory effectively explain the semantic evolution of the Chinese character jie?

Methodologically, we adopt a diachronic and qualitative analysis (Creswell and Creswell 2023) guided by the theory of dynamic categorization, analyzing three tagged sub-corpora of the Academia Sinica Ancient Chinese Corpus. The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature, Section 3 introduces the theoretical foundation of dynamic categorization, Section 4 outlines the methodology, data collection and analysis procedures, Section 5 provides a foundational semantic analysis of jie. Sections 6–8 then offer a detailed analysis of jie’s semantic evolution through the three stages of conservative gradual change, interaction/spanning between adjacent/similar semantic categories, and decategorization. Finally, Section 9 concludes the paper. Through this investigation, this study contributes not only to a deeper understanding of the dynamic characteristics of Chinese lexical semantics but also provides theoretical insights for future studies on semantic evolution.

2 Literature review

Research on the diachronic semantics of Chinese has become an important sub-field within linguistics, with a primary focus on tracing how word meanings evolve over time in response to communicative needs, cognitive patterns, and sociocultural contexts. Early work concentrated on documenting lexical changes in classical and medieval Chinese, identifying patterns of semantic expansion, narrowing, and shift (Lü 2014; Ota 2003). Later studies examined high-frequency words and functional items, revealing that many undergo regularized developmental paths shaped by recurrent usage contexts (Jiang 2011, 2017). Scholars have explored the semantic trajectories of modal verbs and adverbs, often combining diachronic corpus analysis with grammatical analysis to trace their transformations (Jiang 2007; Yin and Li 2021). More recent research has emphasized the necessity of integrating cognitive linguistic perspectives into semantic studies in order to explore the diachronic evolution and underlying cognitive mechanisms of Chinese character meanings (Zeng 2025). This shift has laid the groundwork for exploring the cognitive mechanisms that underlie semantic change.

Cognitive linguistics has provided important explanatory tools for semantic change in Chinese, particularly through mechanisms such as metaphor and metonymy. Jiang (2013) argues that different word meanings arise primarily from metaphor, metonymy, and grammaticalization, and that this phenomenon is a result of semantic evolution. Chai (2014) points out that, from the perspective of human subjective cognition, metaphor and metonymy constitute the primary cognitive patterns that drive the semantic change of Chinese words. Zhang (2019) analyzes the semantic change of the term daka (打卡, ‘clock in/out’) and points out that this change is mainly driven by metonymic mechanisms, which include the type “means-to-result metonymy” and the type “means-to-feature metonymy.” This conclusion confirms the view in cognitive linguistics that semantic change relies on mechanisms such as metaphor and metonymy. Zeng (2025) reviews the development of dynamic categorization theory, emphasizing the importance of accounting for conservative gradual change within categories, interaction and spanning between adjacent or similar categories, and decategorization, each driven by cognitive mechanisms. This body of research provides methodological and theoretical resources for examining the multi-stage semantic trajectory of jie.

Yang (2001) traces the semantic and grammatical development of jie from its earliest meaning of “to separate into parts” to its emergence as a modal auxiliary. She identifies three auxiliary functions, expressing subjective ability, possibility, and inevitability. Jiang (2007) examines the parallel development of jie, hui (会, ‘can’), and shi (识, ‘know’), showing that all three originated in verbs of knowing and followed comparable but distinct grammaticalization paths toward auxiliary status. Fan (2022) analyzes Late Imperial and modern Chinese corpora to map the semantic domains of ability modal, including jie, locating it within both ability and possibility subdomains. These studies establish the developmental stages of jie’s semantic change, but they have not systematically situated its development within the framework of dynamic categorization theory or examined the precise cognitive mechanisms driving each stage.

Although previous research has documented the distinct meanings and functions of jie, two main gaps still remain. First, no existing study has applied dynamic categorization theory to explain the full trajectory of jie from its lexical origin to its auxiliary uses. Second, existing accounts often describe cognitive mechanisms such as metaphor and metonymy without situating them within a systematic stage-based model. The present study seeks to provide an integrated account of jie’s diachronic semantic development by linking linguistic evidence with dynamic categorization theory. Drawing on this theory, the present study aims to trace jie’s evolution from a lexical verb to an auxiliary, identify the cognitive mechanisms at each stage, and explain these mechanisms within the theory.

3 Theoretical foundation

Categorization theory constitutes one of the foundational frameworks in cognitive semantics research on word meanings (Zeng 2020). Categorization theory has progressed from classical and prototype models to frameworks that also account for processes like decategorization. Zeng (2018) argues that earlier studies primarily emphasized static analyses of lexical extension and deepening at a synchronic level, neglecting the inherently dynamic nature of semantic categorization at diachronic and immediate-context levels. To address this shortcoming, Wen and Zeng (2018) and Zeng and Wen (2019) formally proposed dynamic categorization theory. Zeng (2018, 2020) further clarifies three critical aspects of dynamic categorization theory. First, dynamic categorization refers to the immediate change or diachronic evolution of semantic categories at the lexical, sentence and discourse meaning levels under the influence of metaphor, metonymy, base/profile and other working mechanisms. At the lexical level, this categorization concerns lexical features and relations. At the sentence level, it primarily addresses categorization of grammatical terms and the structural relationships. At the discourse level, it focuses on the categorization of the evaluation meaning. Second, semantic dynamic categorization is influenced by both objective and subjective motivations. Third, dynamic categorization can be classified into two types: dynamic categorization within individual semantic categories and within composite semantic categories.

3.1 Three stages of dynamic categorization

There are three principal stages in the process of dynamic categorization as follows:

The first stage is conservative gradual change within categories, which refers to adjustments in the status of members within a category, resulting in a realignment of typicality and membership. The second stage is interaction/spanning between adjacent/similar semantic categories, which refers to the process of mutual expansion between adjacent or similar categories, allowing for the blurring of categorical boundaries and the emergence of hybrid meanings. The third stage is decategorization, as an open-ended transformation, which represents a more radical form of change, where words may undergo complete recategorization or decategorization, moving beyond their original categorical framework. (Zeng 2025)

Initially, semantic evolution involves conservative gradual change within categories, characterized by internal adjustments among category members without breaching established category boundaries. Specifically, these gradual changes rely heavily on the base/profile mechanism, whereby core semantic meanings (base) are highlighted (profile) in specific contexts. It is the interaction between the base and its salient aspects, rather than either element alone, that determines word meaning (Wen and Yang 2022).

As category membership enriches, the second stage emerges, characterized by interaction and spanning between adjacent or similar categories. At this stage, cognitive mechanisms such as metaphor and metonymy facilitate semantic expansion beyond original category boundaries, demonstrating linguistic cognitive flexibility and creativity.

Finally, the decategorization stage occurs, wherein word meanings typically become more abstract, transcending their initial concrete or abstract categories and often evolving into function words or grammatical markers, thus losing their original concrete-action connotations. We must point out that the three stages collectively form a continuum of dynamic categorization for an individual semantic category, in which some words experience only the first two stages, others proceed directly and radically through decategorization, whereas most words develop sequentially along the continuum (Zeng 2018).

3.2 Mechanisms of dynamic categorization

Zeng (2018) identifies four main mechanisms of dynamic categorical development: (1) base/profile mechanism; (2) metaphor; (3) metonymy; and (4) shifts in image schemas.

The meaning of a word can be described in terms of base and profile. The base refers to the domain foundation within which the expression is construed, and it constitutes the cognitive domain of the word’s meaning. When a specific part of the base receives prominence, it functions as the profile. This profile constitutes the meaning of the expression. By profiling different parts within the semantic domain, one can dynamically construct category members that share the same base (Langacker 1991; Zeng 2021). Metaphor facilitates semantic comprehension and expression by mapping attributes from one category, usually concrete and easily comprehensible, onto another category, often abstract and less tangible. Metonymy, by contrast, establishes new meanings through contiguity, mapping specific properties or components of one category onto an adjacent category. Image schemas, formed through bodily experience, provide basic cognitive frameworks, such as path schemas and container schemas, that underpin dynamic semantic categorization.

3.3 The application of dynamic categorization theory

This study adopts dynamic categorization theory as its core analytical framework. The necessity of this approach is rooted in the high degree of complexity and the significant diachronic characteristics inherent in the research subject, the character jie. The character jie is not a static collection of polysemous meanings but rather a semantic network that has evolved over several millennia. The evolution of its meaning involves not only the derivation of new senses but also the dynamic adjustment of typicality status between core and peripheral meanings.

Traditional and static theories of categorization exhibit clear limitations in their explanatory power when applied to such a complex diachronic process (Liu 2006; Zeng 2025). Classical categorization theory, for instance, is based on necessary and sufficient conditions, and its rigid category boundaries cannot accommodate two seemingly disparate meanings within the same category. Prototype theory, while depicting the structure of jie’s semantic network at specific historical cross sections by introducing family resemblance and typicality effects, remains essentially synchronic. It focuses on describing what a category looks like but fails to adequately explain the dynamic process of how a category came to be this way.

Dynamic categorization theory precisely compensates for this core deficiency. The fundamental advantage of this theory lies in its shift of focus from static structure to dynamic process. It attends not only to the diachronic evolution of semantic categories over the long course of history but also to the immediate emergence of meaning in specific usage contexts. Therefore, the theory provides a unified perspective that enables a systematic investigation of how every subtle change in jie occurs under the impetus of cognitive mechanisms. It is this emphasis on process and mechanism that makes dynamic categorization theory the more suitable and explanatorily powerful theoretical tool for analyzing the semantic evolution of jie.

4 Methodology

This study employs an interpretive qualitative research approach (Creswell and Creswell 2023). Its purpose is to investigate in detail the semantic development path of the Chinese character jie throughout its evolution and the cognitive mechanisms that underlie this process. The study also uses corpus data to test, exemplify, or refine a pre-existing theoretical framework, specifically the theory of dynamic categorization. Through this method, it systematically organizes and interprets the example sentences that are obtained from the corpora. The analytical procedure is strictly structured around the study’s theoretical foundation.

4.1 Corpus

The primary data for this research are from the Academia Sinica Ancient Chinese Corpus, which is an authoritative resource for Chinese linguistics. To enable a comprehensive diachronic analysis, this study utilizes three of its tagged sub-corpora: the Old Chinese Corpus (pre-Qin to Western Han), the Middle Chinese Corpus (Eastern Han to Northern and Southern dynasties), and the Early Mandarin Chinese Corpus (Tang and later). The use of these tagged corpora provided the reliable linguistic examples necessary for the qualitative analysis. As secondary data, this study consults Glossary of Terms and Expressions in Chinese Poetry, Lyrics, and Songs (诗词曲语辞汇释, Shiciqu Yuci Huishi) (Zhang 1977 [1953]), which records the historical variation and transformation of terms in Chinese poetry, lyrics, and songs. Its focus on lexical fluidity and diachronic change provides essential evidence that supplements corpus findings on semantic evolution.

4.2 Data collection

The primary data for this study were collected and processed directly within the online interface of the Academia Sinica Ancient Chinese Corpus. The initial step involved using the retrieval function to search for all occurrences of the character jie within the three designated historical sub-corpora.

The subsequent filtering and analysis were conducted using the platform’s advanced processing tool. The initial search results were reviewed online, and irrelevant instances, such as those where jie appeared as part of a proper name, a place name, or in corrupted or contextually ambiguous sentences, were manually identified and excluded from consideration for the final analysis. The valid examples were then examined and categorized chronologically directly within the corpus environment, forming the basis for tracing jie’s semantic evolution.

4.3 Data analysis

Before the diachronic analysis could be conducted, a foundational analysis of the character’s core semantic properties is necessary. This preliminary step is methodologically essential because it establishes a stable baseline from which all subsequent changes can be explained.

This foundational analysis is approached from four perspectives, and each perspective provides an indispensable tool for the main diachronic investigation. First, the application of the base/profile mechanism deconstructs the character’s meaning into its core semantic components. This deconstruction provides the analytical framework that is necessary to track precisely how these components are later altered, abstracted, or eliminated over time. Second, the identification of associated image schemas reveals the underlying cognitive structures. These structures are what enable the metaphorical and metonymic extensions from concrete to abstract domains, so their identification is crucial for explaining the logic of those extensions. Third, an assessment of the character’s potential for categorical extension clarifies its cognitive status as a basic-level category. This assessment explains why jie is a productive source of semantic change and justifies its selection as a suitable subject for a study on dynamic categorization. Finally, an examination of dictionary definitions and ancient written forms serves to ground the analysis in historically attested meanings. This step corroborates the identified prototype meaning and ensures that the entire diachronic analysis begins from a verifiable starting point.

The main diachronic analysis proceeds after this foundational work. We conduct an in-depth reading and systematic summary of the corpus examples from each historical period. The semantic evolutionary path of jie is divided into three levels for analysis. The first level is gradual change within its basic semantic category. The analysis examines how jie combines with different types of nouns, a process that results in an initial extension of its meaning. The second level is interaction and spanning of jie between adjacent or similar semantic categories. The study investigates how jie achieves a transition from the concrete physical domain to the abstract conceptual domain. This transition occurs through cognitive mechanisms such as metaphor and metonymy. The final level is decategorization. The analysis explains how jie gradually detaches from its original verbal category and evolves into a function word with a more abstract role. It also organizes the different functional stages that appear during its decategorization process. In each step of the analysis, we identify and explain the cognitive mechanisms that drive the semantic changes.

5 Semantic analysis of jie

The Chinese character jie is a frequently used yet semantically complex word. This section conducts a detailed semantic analysis of jie from four perspectives: (1) its semantic base, (2) image schemas, (3) possibilities for categorical extensions, and (4) dictionary definitions.

5.1 Semantic base of jie

The original meaning of jie pertains to actions such as releasing, separating, or untying, categorizing it as a verb denoting a change of state. When examining its primitive meaning, one typically envisions a scenario where an agent or force acts upon an object, causing it to become free from a state of constraint or fixation. The semantic base of jie thus encompasses two fundamental components: the instrument and the state change. The instrument generally refers to a hand or a physical tool, while the state change denotes the transition of an object from a fixed or bound state to a released or loosened one. The patient is the object undergoing this transformation.

In practical contexts, the instrument applied by the agent could be human or non-human forces. For example, when we use the expression jie sheng (解绳, ‘untie a rope’), the instrument involved might be the hand itself, scissors, or a knife blade. Essentially, the instrument is pivotal in altering the current state, facilitating the transition of the object from one state into another (Hopper and Thompson 1980).

The core semantic feature of jie is state change, specifically describing the transformation of an object from a condition of constraint, fixation, or closure into a state of release, looseness, or openness. Such a change constitutes the direct outcome of the action implied by jie. For example, jie suo (解锁, ‘unlock’) clearly signifies the transformation from a locked state to an open state.

Result marks the ultimate manifestation of the action of jie. It not only indicates completion but also highlights the effect brought about by the action. In contexts involving jie, the result typically features a significant alteration in the patient’s state. Examples include jie kun (解困, ‘resolve difficulties’) representing the elimination of troubles, and jie huo (解惑, ‘resolve confusion’) denoting the clarification of doubts.

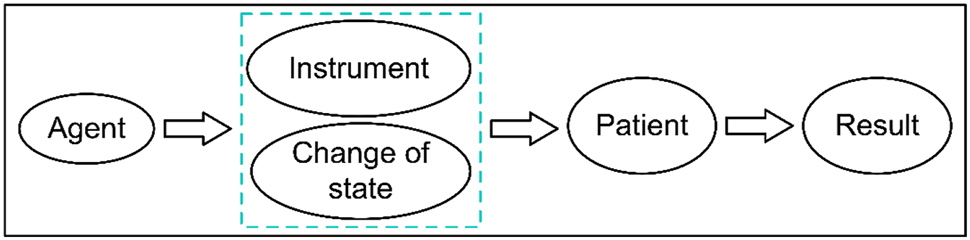

Figure 1 illustrates its core components as revealed through base/profile analysis.

Semantic base of jie.

According to the base/profile theory, nouns typically foreground entities, whereas verbs foreground relationships (Evans and Green 2006; Langacker 1987; Zeng 2021). In the verb jie, at least two components are prominently highlighted. For instance, in jiehuo, jie foregrounds both the instrument (thinking or explanation) and the state change (transition from confusion to clarity). Similarly, jiesuo (解锁) foregrounds the instrument (key-turning action) and the state change (transition of the lock from closed to open).

5.2 Image schemas associated with jie

Johnson (1987) and Lakoff (1987) initiated the theory of image schemas within cognitive linguistics. Commonly identified image schemas include path schema, container schema, force schema, part-whole schema (Wen and Yang 2024). Johnson (1987) identifies many other image schemas, such as balance schema, compulsion schema, blockage schema, counterforce schema, restraint removal schema, enablement schema, attraction schema, mass-count schema and link schema. However, he also thinks that these image schemas are highly selective, and we cannot list all of them.

Analyzing jie through the lens of its fundamental meaning and usage contexts, we identify several relevant schemas – force schema, container schema, path schema, and part-whole schema.

Firstly, jie prominently involves the force schema. An agent purposefully applies an instrument onto a patient, producing a result. Such an instrument could be a human hand or another facilitating device. From the semantic base, it is evident that jie connects two entities – typically the hand or an auxiliary tool, and the patient – through the action itself. Consequently, jie fundamentally implies an action involving force transfer, including dynamics such as propulsion, compulsion, obstruction, reaction, transformation of force, removal of constraints, granting force, attraction, and repulsion.

Secondly, jie involves the container schema, prominently evident in meanings associated with removing restrictions or releasing constraints, such as jietuo (解脱, ‘extricate oneself’) and jiebang (解绑, ‘unbind’). This schema represents a shift from containment (restricted internal state) to freedom (external state). The inside-outside opposition within the container schema is highly applicable here, vividly symbolizing the transition from being bound to becoming free.

Thirdly, the path schema is essential when jie denotes comprehension or problem-solving processes. In contexts such as solving or explaining issues, cognitive processes traverse from confusion to clarity, metaphorically moving along a mental pathway from the initial problem state (uncertainty) to the final understanding (clarity).

Finally, the part-whole schema is activated in contexts such as jiepou (解剖, ‘dissect’) or jiegou (解构, ‘deconstruct’), where jie involves separating specific parts from a larger whole. Here, jie signifies the isolation or identification of discrete components within an entity, as exemplified by detailed anatomical dissection.

Therefore, jie encompasses diverse image schemas which transition from constraint to freedom, from obscurity to clarity, and from whole to parts. Depending on context, these schemas may vary in prominence, always capturing the essence of transition between distinct states. For example, problem-solving typically emphasizes the path and force schemas, whereas untying a knot highlights containment and part-whole schemas. This flexible combination enriches the dynamic semantic characteristics of jie.

5.3 Possibilities for categorical extension of jie

Generally, cognitive categorization occurs across three hierarchical levels: superordinate, basic-level, and subordinate categories. Typically, superordinate categories are collective nouns, basic-level categories are countable nouns, and subordinate categories, sharing family resemblances, represent parasitic categories possessing more precise information than basic-level categories (Wen and Yang 2024).

Basic-level terms are most frequently utilized in daily language (Wen 2014). Jie belongs precisely to the basic-level category because encountering jie spontaneously conjures images of a person using hands or tools to untie or release something. Hence, jie represents a prototypical action event, encompassing an agent, patient, action, and resultant state. As human actions commonly involve hand participation, jie notably emphasizes bodily movements, classifying it as a prototypical bodily-action verb. Its semantic concreteness forms distinct cognitive imagery, making jie cognitively prominent. Basic-level words usually form the cognitive foundation, upon which superordinate and subordinate categories build, thereby granting them the highest morphological productivity. Jie, as a fundamental bodily-action term, easily combines with similar basic-level words to generate terms such as jiekai (解开, ‘untie’) and jiemi (解密, ‘decode’).

Considering the base/profile mechanism, the fundamental meaning of jie, releasing or untying, expands into more specific actions or states through contextual highlighting. Examples include jiebang (解绑, ‘unbind’), highlighting removal of constraints, and jiemi, emphasizing revelation of secrets. Metaphor extends categories through conceptual similarity mappings. Metonymy, which operates on the principle of contiguity rather than similarity, shifts meanings to adjacent domains – for example, jieshuo (解说, ‘commentate’) transfers explanatory meanings into sports commentary contexts. Image schema shifts facilitate domain-crossing applications, extending jie beyond physical separations into broader cognitive areas, such as psychological state alterations and relationship dissolutions. Nevertheless, despite these cross-domain extensions, jie consistently maintains its core semantics of separation or release.

Thus, the categorization of jie is dynamic and multifaceted which evolves divergently through multiple linguistic mechanisms and cognitive pathways. Far from being simple linear extensions, these developments pivot around jie’s core meanings, diversifying semantic richness in varied contexts. For example, expressions such as jiedu (解毒, ‘detoxification’) and jiema (解码, ‘decode’) both originate from the prototypical meaning of jie. Through various mechanisms, their meanings have been extended and enriched, representing the dynamic process of categorization and highlighting both the vitality of language and the flexibility of human cognition.

5.4 Dictionary definitions of jie

The earliest depiction of jie appears in oracle bone inscriptions from the Shang dynasty, depicting two hands separating a bull’s horn, thus originally signifying “to separate or dissect.” In seal script, the “horn” (角, jiao) component is shifted to the left, the “hand” (手, shou) is transformed into a “knife” (刀, dao) and placed in the upper right, while the “ox” (牛, niu) is positioned in the lower right. However, the overall meaning of the character remains unchanged. Xu (2018) defines jie as “judgment or division, derived from using a knife to cut a bull’s horn,” symbolizing division and discrimination. Jiang (2006) emphasizes detailed semantic analysis and categorization when researching word meanings. Based on authoritative dictionaries, including Modern Chinese Dictionary (7th edition), Xinhua Dictionary, Standard Dictionary of Modern Chinese, and Commonly Used Characters in Classical Chinese, we refine the meanings of jie into essential semantic categories: (1) to untie bound objects; (2) separate; (3) remove; (4) explain; (5) understand; and (6) escort goods or prisoners. Defining the meanings of jie will be helpful to corroborate the identified prototype meaning and ensures that the entire diachronic analysis begins from a verifiable starting point as we mentioned in Methodology.

6 Conservative gradual semantic change of jie within its category

6.1 The prototypical meaning of jie

Ma (2015) argues that verbs typically denote actions, behaviors, existence, changes, or intentions. We posit that the semantic dynamism of a verb largely corresponds to its degree of transitivity. As mentioned earlier, the Chinese character jie first appeared in Shang dynasty oracle bone inscriptions, and judging from its ancient form, it clearly possesses a strong dynamic quality.

| 兵车之属六, 乘车之会三, 诸侯甲不解缧, 兵不解翳, 弢无弓, 服无矢。(春秋《国语》)[There were six classes of military chariots and three categories of ceremonial chariots; the armor of feudal lords was not to be unbound, nor were soldiers to uncover their weapons; bows were not removed from cases, nor arrows from quivers. Guoyu (Spring and Autumn Period, 770 BC–403 BC)] |

| 解其长剑, 而受教于子, 天下皆曰孔丘能止暴禁非。(战国《庄子》)[If violent men were to unbuckle their swords and receive your teachings, the world would proclaim that Confucius could restrain violence and prohibit wrongdoing. Zhuangzi (Warring States Period, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

From Examples (1) and (2), it is evident that in the structure “jie + noun,” when the object is a concrete entity, the meaning of jie prominently foregrounds two key components of its semantic base: the action itself and the patient undergoing this action. Within the framework of the base/profile (Langacker 1987), the semantic base of jie encompasses the entire event of removal, including the agent, the instrument, the object, and the resultant state. What the verb profiles, however, is specifically the interaction between the action and its patient, thereby highlighting transitivity. Both sentences involve distinct agents with strong individuality; specifically, the actions of unbinding armor (解缧, jieluo) and unbuckling one’s sword (解其长剑, jieqi changjian) are swift, deliberate, and goal-oriented. The verb jie, in these contexts, strongly emphasizes the exertion of force and a completed action resulting in tangible consequences. Example (1) stresses that the armor of feudal lords and coverings of soldiers’ weapons were not to be removed, while Example (2) implies that removing swords symbolized acceptance of moral guidance, thereby reducing violence and wrongdoing. Clearly, jie demonstrates a high level of transitivity within the construction “jie + noun (concrete object),” thus marking it as a strongly dynamic verb.

In cognitive linguistics, transitivity is understood not as a simple binary property, but as a continuum describing the degree to which an action is effectively transferred from an agent to a patient (Hopper and Thompson 1980). High transitivity is characterized by features such as a volitional, agentive subject acting upon a concrete, highly affected patient, resulting in a clear change of state. The use of jie in constructions like jieqi changjian (解其长剑, ‘to unbuckle one’s sword’) is an example of high transitivity; a clear agent purposefully acts on a specific object, fundamentally altering its state. This high degree of transitivity is directly linked to its dynamic quality and its status as the prototypical meaning of jie. Such actions represent prototypical events in human cognition – they are salient, physically grounded experiences that serve as cognitive reference points. Because the meaning of jie in the “jie + noun (patient object)” construction so perfectly captures this dynamic, high-transitivity event, it became established as its prototypical sense. Consequently, the basic dictionary definition is typically listed as “to untie something bound or fastened.” As Jiang (2006) points out, during historical semantic evolution, basic meanings gradually extend into derived meanings, some closer to the original, others more distant. Thus, a thorough analysis of jie’s extended meanings must begin with this cognitively foundational, prototypical usage.

6.2 Gradual semantic change of jie

The semantic evolution of jie exhibits conservative gradual change within its semantic category, developing multiple derived meanings primarily from the original core meaning of “separating a bull’s horn with hands,” gradually expanded through varying object types in verb-object constructions without departing from its foundational semantic domain.

6.2.1 Semantic change in “jie + noun (living entity)”

According to our investigation, semantic shifts of jie were evident as early as pre-Qin literature based on the corpora we selected. At this stage, it no longer exclusively meant “separating bull horns,” nor necessarily involved hands directly. Instead, jie evolved to mean “using concrete tools to separate physical entities,” illustrated by the Examples (3)–(5).

| 及入, 宰夫将解鼋,相视而笑。(春秋《左传》) [Upon entry, the chef was about to dismember the giant turtle; the men looked at each other and smiled. Zuo Zhuan (Spring and Autumn Period, 770 BC–403 BC)] |

| 庖丁为文惠君解牛。(战国《庄子》) [Cook Ding butchered an ox for Lord Wenhui. Zhuangzi (Warring States Period, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

| 始臣之解牛之时, 所见无非全牛者。(战国《庄子》)[When I first began to butcher oxen, all I saw was the whole ox. Zhuangzi (Warring States Period, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

In Example (3), jie involves the dissection of a turtle rather than bull horns. Examples (4) and (5) describe Cook Ding dissecting an ox with a sharp knife. Here, jie simply refers to dismembering living creatures using sharp instruments. These uses of jie are structured by the part–whole image schema, since animals are construed as integrated wholes that can be divided into distinct parts. They also draw on a force schema, as the action involves applying external force with a sharp tool to overcome resistance and achieve separation. At the same time, they instantiate a metaphorical mapping whereby the physical act of cutting and partitioning an organism is conceptualized as segmenting a unified body into manageable sections, projecting embodied experience of physical division onto linguistic expression. Although jie functions as a transitive verb directly preceding objects in these sentences, we also find occurrences in pre-Qin literature where the patient object precedes the verb jie, which will be illustrated in Examples (8) and (9).

Additionally, jie came to denote “escorting prisoners”:

| 你不得打! 才打他一拳, 我便解你去官里治你。(宋代《朱子语类》) [You must not beat him! If you hit him once more, I shall escort you to the authorities to be punished. Zhuzi Yulei (Song dynasty, 960 AD–1279 AD)] |

| 那两个公人, 领了文, 押解了武松, 出孟州衙门便行。(明代《水浒传》) [The two officers received the warrant and escorted Wu Song out of the Mengzhou government office. Water Margin (Ming dynasty, 1368 AD–1644 AD)] |

In Examples (6) and (7), jie indicates “escorting prisoners or persons,” a frequent usage in Classical Chinese. In Example (6), the object “you” directly follows jiè, while the phrase “to + location + verb” further clarifies the destination and purpose. In Example (7), jiè combines with ya (押) to form the compound verb yajie (押解), denoting escort and supervision. These uses instantiate the path schema: the escorted individual is construed as moving from a source, along a trajectory, toward a goal (typically an authority). They also involve metonymy: naming the transport phase (jiè) stands for the transfer event under official control.

| 杀于庙门西, 主人不视豚解。(春秋战国《仪礼·士虞》) [Sacrificed at the west gate of the temple, the host did not observe the pig’s dissection. Yili Shiyu (The Spring and Autumn and the Warring States Period, 770 BC–221 BC)] |

| 虽体解吾犹未变兮, 岂余心之可惩。(战国《离骚》) [Though my body be torn apart, my resolve shall remain unchanged. Lisao (Warring States period, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

According to Huang (2008), the Chinese language began shedding most of its synthetic features as early as the Han, Wei, and Six dynasties period, gradually transforming into a largely analytic system. This implies that before this linguistic shift, Chinese still retained noticeable elements of a synthetic structure. Here, “豚解” (tunjie, ‘pig’s dissection’) and “体解” (tijie, ‘body be torn apart’) adopt passive constructions, highlighting semantic flexibility. Example (8) implies the pig was slaughtered without the host’s observation, while Example (9) conveys resilience despite bodily dismemberment. These uses of jie are grounded in the part–whole schema, in which a living organism is conceptualized as an integrated whole that can be divided into constituent parts. Simultaneously, they instantiate a force schema, since an external force is applied to the body of the pig or to the speaker’s own body, overcoming resistance and resulting in physical separation. Despite positional shifts, these cases do not diminish jie’s transitivity; indeed, syntactic inversions reinforce semantic connections between the action and patient. In the book Yili, there is also the expression “豚解”, but its structure differs from that in Example (8).

| 离肺, 豕亦如之, 豚解,无肠胃。(春秋战国《仪礼》)[The lungs are removed, and the same procedure applies to the sacrificial pig. The animal is dismembered limb by limb, with the intestines and stomach discarded. Yili (The Spring and Autumn and the Warring States Period, 770 BC – 221 BC)] |

In the phrase “豚解”, “豚” functions as an adverbial of manner rather than as an object, indicating “to dismember a pig in the same way as one would dismember a suckling pig.” This sentence also instantiates the part–whole schema and force schema like Examples (8) and (9). From Examples (1) to (10), regardless of whether the object of jie is preposed or postposed, its transitivity is not diminished; on the contrary, these special syntactic structures actually reinforce the relationship between the action and the patient. Even when the object does not occupy its conventional position, the integrity of the transitive verb can still be maintained through means such as preposing or anaphoric reference. Ultimately, the Chinese character jie remains a highly transitive verb. In subsequent sections, we will further discuss instances where jie may also function as an intransitive verb.

6.2.2 Semantic change in “jie + noun (non-living entities)”

Beyond biological dissections, jie’s usage extends into abstract or non-living domains:

| 桓公解管仲之束缚而相之。(战国《韩非子》) [Duke Huan freed Guan Zhong from his bindings and made him prime minister. Hanfeizi (Warring States Period, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

| 至齐, 见辜人焉, 推而强之, 解朝服而慕之。(战国《庄子》) [Arriving in Qi, Qu Boyu saw a convict’s corpse; moved by compassion, he removed his official robe and covered the body. Zhuangzi (Warring States Period, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

In Examples (11) and (12), the verb jie (解) denotes “to remove,” “to relieve,” or “to take off.” In Example (11), Duke Huan untied the ropes binding Guan Zhong and appointed him as his prime minister. In Example (12), when Qu Boyu arrived in the state of Qi, he saw the corpse of a criminal, approached to move the stiff body, and then removed his official robe to cover it. In both cases, the Chinese character jie does not refer to the dismemberment of an organism; rather, the action is performed using human hands as the primary instrument. From a cognitive perspective, these uses of jie instantiate a means-for-result metonymy, where the physical act of untying or taking off stands for the resulting state of release or removal. In Example (11), the act of untying the bindings stands for Guan Zhong’s liberation, while in Example (12), the act of taking off the robe stands for the state of no longer wearing it and for its new function as a cover.

| 晋文公解曹地以分诸侯。(春秋《国语》) [Duke Wen of Jin partitioned the lands of Cao to distribute among feudal lords. Guoyu (Spring and Autumn Period, 770 BC– 403 BC)] |

| 晋始伯而欲固诸侯, 故解有罪之地以分诸侯。(春秋《国语》) [Jin first became hegemon, partitioning lands of guilty lords to strengthen alliances. Guoyu (Spring and Autumn Period, 770 BC–403 BC)] |

In Examples (13) and (14), the verb jie signifies “to divide a tangible entity using a physical instrument.” During the Western Zhou period, the system of enfeoffment was originally an exclusive privilege of the Son of Heaven; however, the state of Jin, as a hegemon, assumed this prerogative. Example (13) describes how Duke Wen of Jin divided up the territory of Cao to enfeoff other feudal lords, while Example (14) explains that, in order to consolidate its dominance over the vassal states, Jin partitioned the lands of those who were guilty and distributed them among other nobles. In these instances, the Chinese character jie does not refer to the dismemberment of a living entity, yet the instrument involved remains a sharp blade. The narrative depicts Duke Wen as if wielding a knife to cut apart the lands of Cao and those of the guilty lords. This reflects the part-whole schema in which a unified entity is segmented into smaller parts, and it further illustrates a metaphorical mapping whereby land is conceptualized as a body that can be cut. At the same time, the verb operates metonymically, since the action of cutting with a blade stands for the political act of redistribution. This semantic extension, from the dismemberment of organisms to the partition of inanimate objects, demonstrates the verb’s capacity for transitive expansion. Moreover, this metaphorical usage marks the beginning of semantic generalization through rhetorical extension (Yang 2001).

| 缘上面自要许多用, 而今县中若省解些月桩, 看州府不来打骂么? (宋代《朱子语类》) [The higher authorities demand substantial funds; if the county now reduces its regular contributions, won’t the prefecture come to reprimand us? Zhuzi Yulei (Song dynasty, 960 AD – 1279 AD)] |

| 前日多累你押解老爷行李车辆, 又救得奶奶一命。(明代《金瓶梅》) [The other day, thanks to your effort in escorting the master’s luggage and carts, you also saved the lady’s life. Jinpingmei (Ming dynasty, 1368 AD–1644 AD)] |

In the above two examples, jie denotes “to escort or deliver property.” In Example (15), the verb phrase shengjie (省解) forms a compound structure, referring to the reduction or exemption of funds such as monthly stipends or allowances that local governments are required to remit to higher authorities. In Example (16), yajie (押解) is a verb-object construction meaning to escort luggage and vehicles. yajie was a specialized term in official and yamen (衙门,‘administrative office’) parlance, originally referring to the guarded transport of criminal offenders, but later extending to property as well. These uses of jie are grounded in the path schema, which structures the notion of movement from a source, along a trajectory, toward a goal. In Example (15), the delivery of funds is conceptualized as property moving upward along an institutional path from county to prefecture. In Example (16), the act of escorting similarly instantiates this schema, with the addition of metonymic extension: a term originally applied to the transport of offenders is extended to cover the transport of goods. This combination of path schema and metonymy illustrates how jie broadened from concrete human escort to the regulated delivery of property.

All of the examples cited above illustrate the use of jie as a transitive verb. As previously mentioned, the Chinese character jie can also function intransitively, in which case its meaning shifts to “to separate.” More specifically, it can be understood as “to cause something to separate through intangible forces.”

| 天地解而雷雨作, 雷雨作而百果草木皆甲坼。(西周《周易》)[Heaven and earth separate, and thus thunder and rain arise; with thunder and rain, all fruits and plants burst forth from their shells. Zhouyi (Western Zhou Period, 1046 BC–771 BC)] |

| 今王亡地数百里, 亡城数十, 而国患不解, 是王弃之, 非用之也。(西汉《战国策)[Now the king has lost hundreds of li of territory and dozens of cities, yet the crisis of the state remains unresolved. This is because the king has abandoned worthy talents rather than employing them. Zhanguo Ce (Western Han Period, 202 BC–9 AD)] |

Example (17) means that “heaven and earth begin to separate. The movement of yin and yang follows, and then thunder and rain appear. When the thunder and rain come, all fruits and plants sprout and break through their shells.” More specifically, this refers to the vital energies of heaven and earth that open up from winter’s dormant state and enter the generative state of spring. This process symbolizes the renewal of all things in nature. This usage of jie reflects the container schema, in which the cosmos is conceptualized as a closed container that becomes open, allowing the flow of energy and the emergence of life. The abstract cosmological process is thus structured through embodied experience with containment and release. In Example (18), the Chinese character jie denotes the failure of the national crisis to be resolved. This usage is motivated by metaphor: the political crisis is conceptualized as a knot or entanglement, and jie signifies the act of loosening or releasing it. In both examples, the Chinese character jie serves as an intransitive verb and the force that acts in jie is intangible.

6.2.3 Semantic change in “jie + noun (event)”

As the semantic evolution continued, the patient of jie began to shift from simple physical entities to more complex targets. An important development in this process was its application to event-like locations, which foreshadows the move into fully abstract domains discussed later.

Since the Warring States period, the types of objects governed by the verb jie have shown a clear trend of expansion. The focus of the patient has shifted from concrete, tangible entities to event-like locations. This shift reflects a generalization in the semantic scope of its objects. Please see the following examples.

| 孙膑宜走大梁而解邯郸之围。(宋代《孙子集注》)[Sun Bin should proceed to Daliang to relieve the siege of Handan. Sunzi Jizhu (Song dynasty, 960 AD–1279 AD)] |

| 汝可去解樊城之围。(元末明初《三国演义》)[You must go to lift the siege of Fancheng. Romance of the Three Kingdoms (The late Yuan and early Ming period, late 14th to early 15th century)] |

In these examples, “the siege of Handan” (邯郸之围, handan zhiwei) and “the siege of Fancheng” (樊城之围, fancheng zhiwei) refer to specific military encirclement events that occurred in historical or narrative contexts. The word wei (围, ‘siege’) refers to an observable physical act of military encirclement, which has a definite time, location, and set of participants. The geographical markers “Handan” and “Fancheng” anchor the meaning of wei within a concrete spatial domain. Therefore, although the object centers on a place name, it already carries the features of an event. It serves as a target location for the verb jie.

The semantic extension of jie to event-like locations reflects a cognitively motivated shift grounded in both ontological metaphor and image-schematic structure. Specifically, the siege is conceptualized as a reified entity through an ontological metaphor, allowing a complex military event to function grammatically as a manipulable object. Simultaneously, this activates the container schema, in which the besieged city is construed as a bounded space enclosed by external forces. The act of jie metaphorically corresponds to removing or breaching this boundary, thereby restoring permeability between interior and exterior. The convergence of these two cognitive mechanisms, entity construal and spatial containment, underpins the abstract yet embodied understanding of jie in its extended usage.

As demonstrated, the initial evolution of jie involved conservative changes, where its application expanded to new types of concrete and event-like objects while remaining tethered to its core physical sense. However, this was only the first phase of its development. The next stage, as we will now explore, involves an equally significant cognitive leap: the extension of jie across categorical boundaries from the physical domain into the realm of abstract concepts.

7 Interaction and spanning of jie between adjacent or similar semantic categories

In this section, we examine how jie demonstrates semantic interaction and cross-category extension across multiple constructions. Among these, the “jie + abstract noun” construction provides a representative case. With the evolution of language, the semantic scope of jie has expanded from its original reference to concrete physical actions into increasingly abstract conceptual domains. In this process, the abstraction of nominal objects has had a significant impact on the interpretation of jie, revealing not only inter-category interaction but also the role of conceptual metaphor. According to Zeng (2018), such abstraction manifests along three main trajectories: patient objects evolve from material to abstract entities; instrumental objects shift from tangible to intangible forms; and resultative objects transition from concrete outcomes to virtual or inferred states. The semantic extension of jie from concrete to abstract is not merely a linguistic phenomenon but also reflects the metaphorical nature of human cognition.

7.1 Patient objects: from material to abstract entities

As an intentional action verb, the Chinese character jie typically involves a human agent acting upon an object to produce a change of state. In the historical development of Chinese, the patient object of jie underwent a significant semantic shift from material entities to abstract concepts. This shift reflects both internal linguistic evolution and broader developments in human cognitive modeling.

Zeng (2018) argues that early human conceptualization is rooted in material experience. Abstract and ambiguous notions, such as emotions, mental activities, events, and states, are often metaphorically construed as physical entities in order to make them cognitively accessible. As the patient object of jie transitioned from the physical to the abstract domain, the verb itself developed new interpretive potentials.

| 遂以解国之大患, 除国之大害, 成于尊君安国, 谓之辅。(战国《荀子》)[Thus he relieved the state of its great afflictions, eliminated major harms, and brought about peace and reverence for the ruler – this is what is called a worthy minister. Xunzi (Warring States, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

| 天下之士悦之, 人之所欲也, 而不足以解忧。(战国《孟子》) [Although beloved by all scholars and much desired by men, it could not dispel their sorrows. Mencius (Warring States, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

| 今有一言, 除将军之辱, 解燕国之耻, 将军岂有意乎? (东汉《燕丹子》)[Now I have a proposal that can remove your disgrace and alleviate the shame of the Yan state – General, would you consider it? Yan Danzi (Eastern Han, 25 AD–220 AD)] |

In early usage, the object of jie typically referred to concrete entities (e.g. 解鼋 jieyuan, ‘cutting up a softshell turtle’, 解牛, jieniu, ‘butchering an ox’). In Examples (21)–(23), the patient objects are concrete and visible entities. The action of jie directly operates on these physical objects through specific and observable manipulation. In contrast, the examples above involve abstract nouns such as “患” (huan, ‘affliction’), “忧” (you, ‘sorrow’), and “耻” (chi, ‘shame’). These instances reflect a metaphorical mapping in which abstract psychological or social conditions are conceptualized as bounded entities that can be untied, dismantled, or resolved. This metaphorical extension is consistent with theories of embodied cognition, which posit that abstract thought is grounded in sensorimotor experience (Lakoff and Johnson 1980). This shift further implies that interpretations of jie may hinge less on its lexical meaning and more on the grammatical framework it occupies – much like how the English term whole acquires its part-structure sense through the classifier head rather than the word itself (Liao 2015). Consequently, the object of jie shifts from being physically manipulable to representing complex emotional or social conditions.

Compared with removing physical objects, removing abstract ones departs further from the original sense of jie. This shift represents a further extension of its meaning. The transition from the concrete to the abstract not only illustrates the flexibility of linguistic expression but also reveals the essential role of metaphor in human cognitive construction. Therefore, the evolution of patient object types associated with jie reflects not only a natural process of diachronic semantic change but also a concrete manifestation of the interaction between cognitive experience and bodily perception.

7.2 Instrument: from tangible to intangible

Parallel to the abstraction of patient objects, the instrumental tools of jie have undergone a similar shift from tangible tools to intangible cognitive resources. In earlier usages, the instrument associated with jie was typically a physical tool, such as a key in jiesuo (解锁,‘unlocking’). Here, the verb denotes a concrete physical action directly dependent on material implements. Over time, however, jie came to be used with cognitive or linguistic instruments, tools of the mind, such as logic, knowledge, or insight. For instance, in jieti (解题,‘solve a problem’), the action of jie no longer relies on physical manipulation but rather on abstract reasoning or comprehension. This shift has led to two principal semantic developments: (1) the meaning “to explain or analyze a principle verbally,” and (2) “to understand or grasp intuitively.” Examples (24)–(26) illustrate the first semantic development.

| 案往旧造说, 谓之五行。甚僻违而无类, 幽隐而无说, 闭约而无解。(战国《荀子》)[The old doctrine, called the Five Phases, is obscure and illogical – difficult to explain, lacking coherence, and beyond elucidation. Xunzi (Warring States, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

| 孔子自解, 安能解乎。(东汉《论衡》)[“Confucius attempted to explain himself – how could such an explanation be sufficient?” Lunheng (Eastern Han, 25 AD–220 AD)] |

| 解释经义, 须是实历其事, 方见着实。(宋朝《朱子语类》)[To interpret the meaning of the classics, one must have directly experienced the events therein, in order to truly grasp their substance. Zhuzi Yulei (Song dynasty, 960 AD–1279 AD)] |

In Example (24), Xunzi criticizes the Five Elements theory proposed by Zisi and Mencius as obscure, difficult to comprehend, and logically incoherent. In this case, the implied instrument is verbal competence. Example (25) describes how Confucius responded to contradictions in his statements by offering self-justifications, although these often failed to stand up to scrutiny. The tool in this case is the legitimacy of discourse and the force of logical reasoning. In Example (26), the emphasis falls on the necessity of firsthand experience in interpreting classical texts, as only through such experience can one attain genuine understanding. The tool here consists of direct experience and the capacity for insight.

In all three cases, the tools involved belong to the abstract domain. The semantic range of the verb jie is influenced by its adjacent object, and there is a marked tendency toward abstraction. When the tool functions as the object, a conceptual similarity arises between the concrete and abstract uses of jie. This resemblance forms the basis for metaphor. The agent must use a tool or method to carry out an action. These actions produce either concrete or abstract outcomes. The process also involves physical or cognitive effort on the part of the agent. Based on this parallel, ontological metaphor enables a transition in the meaning of jie: from the tangible to the intangible, and from the concrete to the abstract. The semantics of jie demonstrate interaction and transference between analogous domains, leading to increasing abstraction and generalization. The original concrete sense – physically separating an object – becomes mapped onto an abstract sense, such as analyzing and articulating an argument. As a result, the verb jie comes to highlight interpretive and justificatory meanings, such as explaining and defending.

Examples (27)–(29) illustrate the second semantic pathway – jie as “to understand or grasp intuitively”:

| 大惑者终身不解, 大愚者终身不灵。(战国《庄子》)[The gravely deluded remain unenlightened for life; the profoundly ignorant remain uncomprehending forever. Zhuangzi (Warring States, 475 BC–221 BC)] |

| 轲不解音。(东汉《燕丹子》)[Jing Ke could not comprehend the music. Yan Danzi (Eastern Han, 25 AD–220 AD)] |

| 王武子善解马性。(南朝《世说新语》)[Wang Wuzi had a deep understanding of the temperament of horses. Shishuo Xinyu (Southern dynasties, 420 AD–589 AD)] |

In Examples (27)–(29), the instrument associated with jie remain situated in a highly abstract and intangible domain, manifesting as human cognitive capacities and psychological mechanisms. The semantics of jie further generalize in these contexts to denote “comprehension” or “awareness” of external phenomena.

In Example (27), the phrase “remain unenlightened throughout life” points implicitly to cognitive and perceptual faculties of the individual. What is emphasized here is the subject’s inability to overcome internal psychological or spiritual obstacles, which prevents the attainment of truth. In Example (28), “music” as the object of jie carries inherent abstraction. It refers not only to audible sound but also to the more nuanced realm of musical theory and cultural understanding. Jing Ke’s failure to comprehend is not due to a deficit in auditory perception, but to a lack of knowledge in musical principles and cultural context. This further underscores the shift in jie’s instrument from the concrete toward the domain of abstract cognition. In Example (29), the usage of jie expands its cognitive scope even further. The object here implies a kind of interspecies psychological sensitivity and perceptiveness, belonging to a more complex system of cognition and experiential knowledge. Wang Wuzi’s insight results from long-term observation and accumulated experience. His ability to grasp the disposition of horses is entirely abstract and no longer relies on any physical instrument. This exemplifies a full semantic generalization of jie into the realm of mental activities such as awareness and understanding. These examples illustrate the operation of ontological metaphor, whereby abstract mental states such as confusion, knowledge, or animal cognition are reified and conceptualized as concrete entities that can be unlocked, removed, or grasped.

Through the mechanisms of metaphor, metonymy and image schemas, the Chinese character jie successfully traversed from concrete physical actions to abstract cognitive processes, marking the second stage of its dynamic evolution. While these changes were profound, the character largely retained its status as a lexical verb. The final and most radical stage of its transformation, which the next section addresses, involves decategorization, where jie begins to shed its core lexical meaning and grammaticalize into an auxiliary verb.

8 Decategorization of jie

Following its conservative intragroup changes and cross-category semantic extensions, certain senses of the Chinese character jie stabilized as canonical dictionary entries. Yet, its semantic development did not cease. Instead, the Chinese character jie continued to undergo dynamic reanalysis, progressively distancing itself from its original lexical verb category and entering a process of decategorization – most notably, into the realm of auxiliary verbs.

Shimura (1995) observes that one of the hallmark outcomes of verbal evolution is the grammaticalization of verbs into auxiliaries. Yang (2001) identifies three primary uses of jie as an auxiliary verb, all of which originate from its core meaning of “being able to do.” These include: (1) expressing subject’s ability or capacity; (2) expressing objective potentiality; and (3) expressing futurity or inevitability. According to Yang (2001), this development reflects a gradual semantic bleaching of jie. We further argue that these three uses illustrate a continuum of abstraction, whereby jie’s auxiliary function evolves from a partially lexical to a fully grammatical status. Before proceeding with the analysis, it should be noted that the three auxiliary uses of jie proposed by Yang (2001) may appear to be three parallel functional categories. Our study, however, reveals that they in fact constitute a dynamic continuum of semantic evolution. Yang (2001) did not explicitly identify this point, and it is within the framework of dynamic categorization theory that the present study reinterprets these uses, highlighting the continuity and dynamicity that jie exhibits in the processes of decategorization. From this theoretical perspective, we examine the following three stages in sequence.

First, we examine Examples (30)–(32) where jie expresses the meaning of “subjective ability or capacity”.

| 酒能祛百虑, 菊解制颓龄。(东晋陶渊明《九日闲居》)[Wine dispels myriad worries; chrysanthemums can counter the decline of aging. Jiuri Xianju by Yuanming Tao (Eastern Jin, 317 AD–420 AD)] |

| 月既不解饮, 影徒随我身。(唐代李白《月下独酌四首》)[The moon, unable to drink, follows me in vain. Yuexia Duzhuo Sishou by Bai Li (Tang dynasty, 618 AD–907 AD)] |

| 百尺穿成连夜井, 千金购得解飞人。(宋代苏轼《王莽》)[A hundred-foot well dug overnight; a man capable of flight acquired at great expense. Wang Mang by Shi Su (Song dynasty, 960 AD–1279 AD)] |

Before the auxiliary huì (会, “to be able to”) gained prominence in denoting ability, the Chinese character jie served this grammatical function (Fu and Zhu 2004). Ota (2003) notes that by the Tang dynasty, the Chinese character jie had begun to take on a similar function. After the Song dynasty, however, the Chinese character jie largely ceased to be used in this way. In other words, during this earlier stage, the Chinese character jie served to express “ability or capability.”

In Example (30), the Chinese character jie indicates that chrysanthemums possess the medicinal property of resisting aging. This reflects an inherent functional attribute of the plant. From the perspective of cognitive linguistics, the Chinese character jie metaphorically maps this internal property onto an agentive capacity, treating medicinal efficacy as a kind of active competence. In Example (31), the phrase “the moon is unable to drink” expresses that the moon lacks the capacity to perform a behavior exclusive to humans. Here, the Chinese character jie emphasizes the semantic feature of something being performable within the bounds of one’s ability. From a cognitive standpoint, drinking is a social behavior requiring physiological and cognitive faculties that the moon, as a non-human entity, naturally lacks. The Chinese character jie thus metaphorically extends physical action into the realm of cognitive potential. In Example (32), “a man capable of flight” refers to someone who possesses an extraordinary ability. The Chinese character jie directly conveys the subject’s superhuman capability through metaphor and highlights the notion of feasibility at the level of potential action.

In these three examples, the Chinese character jie expresses the semantic notion of “subjective ability or capacity” through metaphorical mechanism, underscoring the subject’s feasibility in terms of ability. This development represents an important stage in jie’s semantic expansion toward increasingly abstract domains.

Second, we examine examples where jie expresses the meaning of “objective potentiality”.

| 肠断关山不解说, 依依残月下帘钩。(唐代王昌龄《青楼怨》)[With heart torn, the mountains cannot express my sorrow, beneath the lingering moon at the window hook. Qinglou Yuan by Changling Wang (Tang dynasty, 618 AD–907 AD)] |

| 那解将心怜孔翠, 羁雌长共故雄分。(唐代李商隐《题鹅》)[Who could bring themselves to pity the peacock’s sorrow, forever parted from her mate. Ti E by Shangyin Li (Tang dynasty, 618 AD–907 AD)] |

| 无花解比, 似一钩新月, 云际初生。(宋代晁补之《紫玉箫》)[No flower could compare to the crescent moon, newly born from the clouds. Ziyu Xiao by Buzhi Chao (Song dynasty, 960 AD–1279 AD)] |

| 沉恨细思, 不如桃杏, 犹解嫁东风。(宋代张先《一丛花令》)[On reflection, I envy the peach and apricot, they still know how to wed the east wind. Yicong Hua Ling by Xian Zhang (Song dynasty, 960 AD–1279 AD)] |

When jie extends from indicating an agent’s ability to a broader sense of “objective potentiality,” it demonstrates a clear trend toward semantic bleaching. The meaning shifts from expressing the subject’s internal capacity to describing conditions or tendencies inherent in the external world. In this stage, the Chinese character jie no longer emphasizes the agent’s initiative or potential, but instead refers to the natural properties or predispositions of events and entities under certain conditions.

In Example (33), the mountains (关山, guanshan) represent a natural setting that cannot possibly articulate human sorrow. The phrase “cannot express” (不解说, bu jieshuo) does not imply a lack of ability in the human sense, but rather indicates the absence of any such possibility in the objective world. In Example (34), the context highlights an external constraint: no individual or being is able to extend empathy toward the peahen’s plight. The focus is not on human capacity, but on the lack of situational conditions for compassion. Example (35) conveys that, objectively, no flower can match the crescent moon. Here, “could compare” (解比, jiebi) refers to an inherent lack of comparable beauty or quality, not to a subjective capability. In Example (36), the phrase “still bloom for the eastern wind” (犹解嫁东风, youjie jia dongfeng) attributes to peach and apricot blossoms a natural response to seasonal change. The Chinese character jie does not describe the plants’ volition, but rather the inevitable result of spring’s arrival.

These four examples share a key semantic feature: the Chinese character jie has fully detached from any sense of subjective agency. It instead refers to qualities and tendencies that exist naturally within external objects or circumstances. This reflects a semantic progression in which jie evolves from denoting specific physical acts, to abstract representations of capability, and ultimately to expressions of objective possibility. These examples illustrate metonymy, where jie undergoes a semantic evolution from denoting subjective ability to expressing potentiality based on objective tendencies or inherent properties of external entities or contexts. Such development illustrates the cognitive path by which jie undergoes further grammaticalization in Classical Chinese, shifting from a marker of “subjective ability or capacity” to a fully bleached form denoting “objective potentiality.”

The distinction between expressing “objective potentiality” and “futurity or inevitability” is subtle yet crucial for understanding the final step in jie’s decategorization. While the former describes a potential inherent in a present situation, the latter represents a more advanced degree of semantic bleaching by projecting an expected or inevitable outcome into the future. This evolution marks its final detachment from concrete lexical meaning. At last, we investigate examples where jie expresses this meaning.

| 未会子孙因底事, 解崇台榭为西施。(唐代罗隐《姑苏台》)[Who would have thought that future generations would build lofty pavilions for Xi Shi? Gusu Tai by Yin Luo (Tang dynasty, 618 AD–907 AD)] |

| 入春解作干般语, 拂曙能先百鸟啼。(唐代王维《听百舌鸟》)[As spring arrives, the birds naturally break into myriad songs, heralding dawn before all others. Ting Baisheniao by Wei Wang (Tang dynasty, 618 AD–907 AD)] |

| 无人解爱萧条境, 更绕衰丛一匝看。(唐代白居易《衰荷》)[No one will come to love this desolate scene, nor circle once more around the withered grove. Shuai He by Juyi Bai (Tang dynasty, 618 AD–907 AD)] |

In its most advanced stage of semantic bleaching, the Chinese character jie ceases to denote current or latent abilities and instead anticipates future states or inevitable outcomes. These usages no longer depend on subjective volition or present contextual affordances, but rather on generalized, culturally or naturally expected tendencies.

In Example (37), the Chinese character jie conveys a historically fated sequence of events, implying that the building of elaborate pavilions for Xi Shi was a foreseeable historical outcome. In Example (38), it anticipates the routine emergence of birdsong in spring as an inevitable seasonal behavior. In Example (39), the Chinese character jie prefigures emotional disaffection, expressing a social inevitability rather than a specific agent’s choice. These examples illustrate metonymy, where jie no longer denotes capability or potentiality, but expresses a shift from current conditions to inevitable outcomes. Thus, in this third auxiliary function, jie expresses a modality of futurity and inevitability, marking the terminal point in its semantic trajectory from concrete verb to highly abstract modal operator.

Through the above analysis, we find that, from a semantic perspective, when jie expresses the meaning of “futurity or inevitability”, it has indeed completely lost its original lexical meaning, having been grammaticalized into a function word and completed decategorization. Yet, from the perspective of its lexical category (part of speech), because auxiliary verbs are considered a subclass of verbs (Shi 2010), it has not entirely departed from the verbal category. Therefore, it has only undergone partial decategorization. During the process of analyzing jie, we also confirm the close relationship between grammaticalization and decategorization. Decategorization is a broader cognitive process that refers to the dynamic evolution of a word as it detaches from its original core categorical features. Grammaticalization, in turn, is the concrete path of realization and the result of this process within the language, wherein a word evolves into a functional word that assumes grammatical functions. In other words, while grammaticalization necessarily involves decategorization, this does not imply that all instances of decategorization are a result of grammaticalization. Subjectivization may also lead to decategorization (Zeng 2018).

9 Conclusions

Given the thousands of years of historical development of the Chinese language and the exceptionally rich documentary resources it preserves, it is our responsibility to analyze and synthesize the historical evolution of commonly used words on the basis of this extensive linguistic evidence, and to identify the types and patterns of semantic change (Jiang 2021). This study traces the Chinese character jie’s development from a concrete verb of physical action to an abstract auxiliary verb of modality and identifies the cognitive mechanisms at work in each stage under the guidance of dynamic categorization theory.

The major findings can be summarized as follows. First, the Chinese character jie exhibits a diachronic trajectory that aligns with the three stages of dynamic categorization. It began with conservative gradual change within its original category, driven by the base/profile mechanism. It then extended across adjacent categories through metaphor and metonymy, shifting from physical actions to the psychological domain. It finally underwent decategorization, grammaticalizing into an auxiliary verb that marks ability, possibility, and inevitability. Second, the analysis demonstrates that these changes can be fully accounted for within the framework of dynamic categorization, since each stage of jie’s evolution from conservative gradual change to decategorization finds a precise explanation in the theory. Third, the case of jie demonstrates that the prototypical meaning “to untie bound objects” serves as the cognitive foundation for a wide network of derived meanings, thereby illustrating the productivity of basic-level categories in semantic evolution.

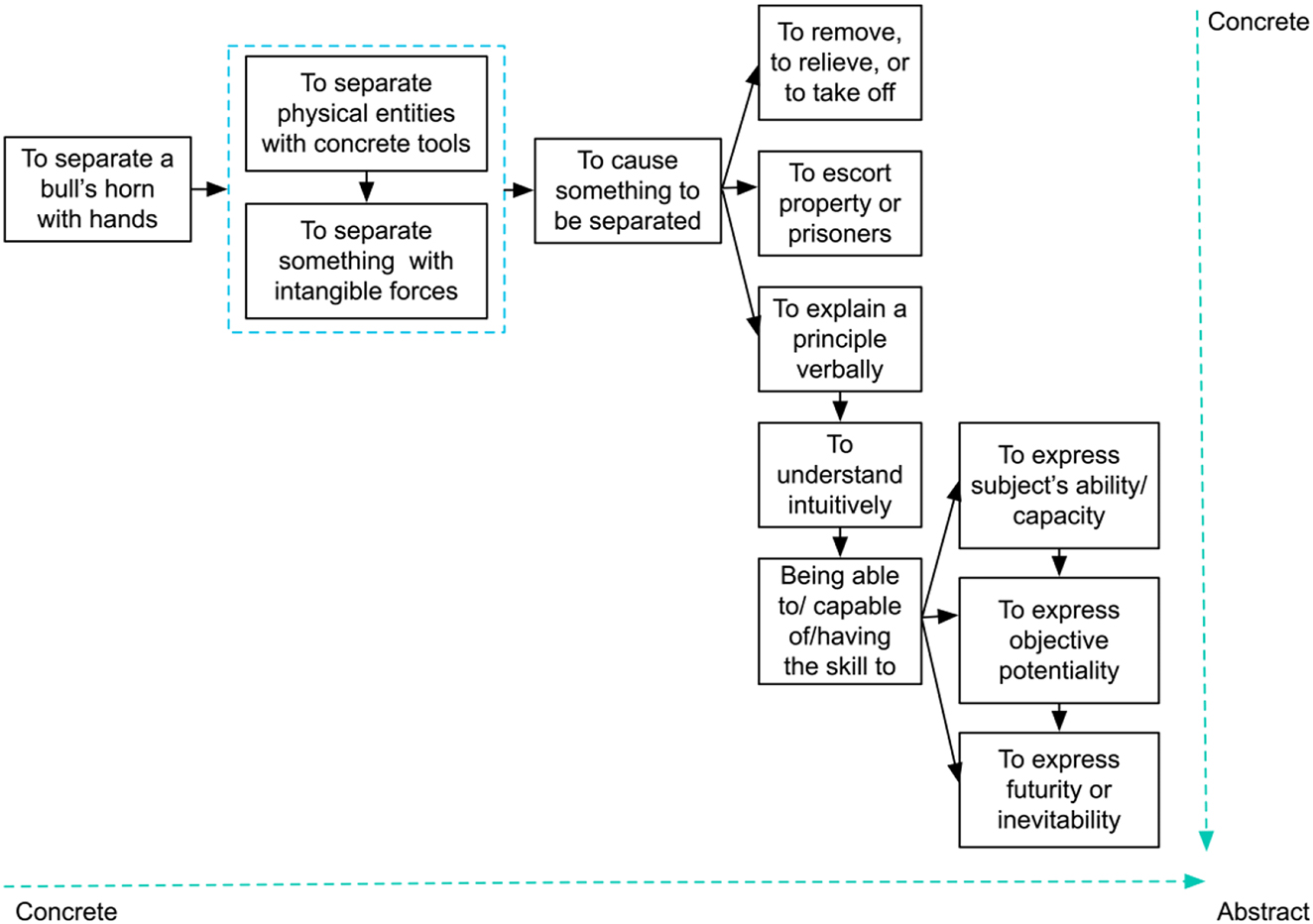

This study explicitly demonstrates how dynamic categorization theory accounts for the semantic evolution of jie. According to the theory, the semantic development of an individual category proceeds through three stages and the evolution of jie follows this trajectory, thereby confirming the explanatory power of the theory beyond what classical categorization theory or prototype theory can offer. The identification of cognitive mechanisms, such as base/profile, metaphor, metonymy, and image schemas, within this framework further illustrates the theory’s effectiveness. Therefore, the findings confirm that dynamic categorization theory not only describes but also effectively explains the diachronic semantic trajectory of jie, as shown in Figure 2.

A semantic evolution trajectory chart of jie.

The study also carries theoretical implications. The diachronic trajectory of jie supports the validity of the three stages of dynamic categorization. At the same time, the case of jie shows that decategorization has a dual character. From a semantic perspective, the Chinese character jie has fully grammaticalized into a functional word and has thus achieved complete decategorization. From a grammatical (or part-of-speech) perspective, however, the Chinese character jie has developed into an auxiliary verb, which remains a subclass of the verbal domain, thus representing only partial decategorization. This dual feature illustrates that decategorization does not necessarily involve a uniform and complete shift, but may instead display asymmetry across different linguistic dimensions.

Future research can extend this work in two directions. One is to apply dynamic categorization theory to other high-frequency verbs in Chinese to further test its explanatory power. Another direction is to conduct quantitative and corpus-based empirical studies, which can test the effectiveness of dynamic categorization theory with large-scale linguistic data and provide measurable evidence for its application to semantic evolution.

Funding source: The National Social Science Fund of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: No. 21BYY168

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China “A Study on the Dynamic Categorization of Chinese Verb Meanings” (grant number 21BYY168).

-

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chai, Hongmei. 2014. Hanyu ciyi yanbian jizhi li tan [A case exploration of the evolutional mechanism of Chinese words meaning]. Zhejiang Shehui Kexue [Zhejiang Social Sciences] (6). 142–147.Search in Google Scholar

Creswell, John W. & J. David Creswell. 2023. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 6th edn. Los Angeles: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Evans, Vyvyan & Melanie Green. 2006. Cognitive linguistics: An introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Fan, Jiandi. 2022. Jindai hanyu nengli lei qingtai zhudongci yuyi yanbian yanjiu: Yi “neng” “hui” “jie” wei li [A study on the semantic evolution of modal auxiliaries of ability in early modern Chinese: A case study of “neng”, “hui”, and “jie”]. Yuyan yu Fanyi [Language and Translation] (3). 11–19.Search in Google Scholar

Fu, Shuling & Jianjun Zhu. 2004. Zhudongci “hui” de qiyuan xintan [A new study of the origin of Chinese auxiliary verb “hui”]. Yantai Daxue Xuebao (Zhexue Shehui Kexue Ban) [Journal of Yantai University (Philosophy and Social Science)] 17(3). 357–360.Search in Google Scholar

Hopper, Paul J. & Sandra A. Thompson. 1980. Transitivity in grammar and discourse. Language 56(2). 251–299. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1980.0017.Search in Google Scholar