Abstract

Given the escalating crisis of environmental degradation, textbooks play a crucial role in cultivating students’ eco-awareness by incorporating ecological themes into language education. However, the way textbooks frame eco-awareness can either challenge or reinforce existing dominant worldviews. This study sheds light on how eco-awareness is represented in Indonesian EFL (English as a Foreign Language) textbooks and unearths the worldviews underlying the representation. Employing a qualitative case study, this study integrates critical multimodal discourse analysis with an ecolinguistic lens to facilitate an in-depth exploration. The findings reveal a pattern of inclusion and exclusion of social actors. When included, these actors are shown engaging with environmental actions or expressing responses (reactions). In contrast, exclusion is commonly realized through visual techniques such as conversion and decontextualized settings, as well as linguistic choices like nominalizations and epithets which obscure human agency. These strategies generate ambivalent discourses that seem to support environmental care while subtly advancing an anthropocentric worldview and individual responsibility, which aligns with neoliberal environmentalism. Consequently, this study suggests that textbooks should better connect images with texts, highlight human agency, and provide real-life examples that promote meaningful ecological engagement.

1 Introduction

Broadly recognized, the global human race is facing a plethora of environmental problems such as global warming, climate change, and pollution. Addressing these issues must be done by global stakeholders, including the Indonesian government. Consequently, raising public awareness and knowledge of environmental issues has become the main concern of the stakeholders. One of the key strategies is integrating environmental education into classroom activities (Maley 2022; Micalay-Hurtado and Poole 2022) or school subjects (Akçesme 2013; Ma 2023; Sharma and Buxton 2015; Triyono et al. 2023; Zahoor and Janjua 2020). In this regard, Zahoor and Janjua (2020) argue that ELT (English Language Teaching) should focus on strengthening English language skills and raising awareness of issues affecting students’ lives. In the Indonesian educational context, ELT should support students in developing social attitudes or competencies such as responsibility, empathy, and determination in their interactions with both social and natural environments as outlined in the national learning outcomes (Triyono et al. 2023).

Environmental education is now included in school textbooks that are used as learning sources and essential teaching tools (Curdt-Christiansen 2020; He and Shen 2023; Suwandi et al. 2018). This integration appears across a wide range of school subjects, including language subjects like English. Within these textbooks, environmental topics are presented through various learning themes and reflect the growing focus on sustainability in education (Faramarzi and Janfeshan 2021; Pratiwi et al. 2021; Suwandi et al. 2018). In this sense, teachers use the textbooks to help students gain knowledge and build awareness of environmental issues. Given their central role in the classroom, textbooks are essential in promoting eco-awareness among students.

The terms “eco-awareness” and “environmental awareness” are used interchangeably in this study. Eco-awareness refers to a multidimensional concept that includes knowledge (an understanding of environmental systems and the human impact on nature), attitudes and values (a sense of ethical responsibility and care for the environment), and behavioral intentions (a commitment to engage in sustainable practices such as recycling and energy conservation) (Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002; Otto and Pensini 2017; Roczen et al. 2014). Eco-awareness does not develop in isolation. As a matter of fact, it is shaped by environmental discourses, which refer to the language and other communicative practices used to represent environmental issues (Yuniawan et al. 2017). The discourses are structured by green ideology, which provides the broader political and ethical framework for promoting environmental values and practices in society (Stavrakakis 1997). These three concepts are interconnected and operate on different levels. In this sense, eco-awareness is shaped through discourses which are framed by green ideology.

Accordingly, raising students’ environmental awareness through textbooks is not only providing information about the environment and ecology. It also requires fostering environmental awareness and understanding of the interconnected relationship between humans and nature. The former role of textbooks is often referred to as shallow environmentalism (Stibbe 2004; Xiong 2014). This perspective highlights ecological problems by emphasizing the physical symptoms, but it fails to explore the underlying causes behind ecological destruction (Stibbe 2004). However, there is now a growing consensus that school textbooks should help students recognise the link between human life and the non-human world. This perspective is aligned with the principle of deep ecology (Raphael and Nandanan 2024; Zahoor and Janjua 2020). From this viewpoint, textbooks should guide students to demystify the political and cultural beliefs that shape how environmental problems are framed and understood.

Textbooks have been recognized not only as a medium for transmitting knowledge but also as a tool that shapes readers’ perception, thought, and experience (Kramer et al. 2003). As the product of governmental policies, sociocultural contexts, and educational beliefs, textbooks are inherently laden with certain culturally appropriate values, social norms, and ideologies (Canale 2020; Curdt-Christiansen 2020). Through their contents and designs, textbooks influence their readers in interpreting social meanings and enable them to align with a community or position them in relation to other groups (Curd-Christiansen 2017). In this way, textbooks serve as a socialization tool that can help students be part of specific cultural communities.

Considering this view, much research has shown that contemporary textbooks do not rely only on written language to communicate messages (e.g. Chen 2021; Lee 2023; Liu and Qu 2014; Weninger 2020). These textbooks integrate various modes of communication such as linguistic, visual, and spatial to shape how knowledge is presented. For instance, Ibrahim (2024) and Ibrahim and Damayanti (2024) found that environmental topics are communicated through both written text and pictures to make students feel more connected to the topic and shape their understanding of environmental issues. The way these multimodal elements are arranged is not neutral. They reflect certain cultural values, social norms, and viewpoints (Machin and Mayr 2012; Serafini 2014).

Recent studies in ecolinguistics have used multimodal discourse analysis (MDA) and critical discourse analysis (CDA) to examine how environmental messages are constructed and communicated across different forms of communication (Choi and Lee 2024; Lee and Kang 2023; Shah et al. 2025; Ponton 2023; Tatin et al. 2024; Triyono et al. 2023). When these approaches are applied to investigate school textbooks, they help reveal whether the textbooks encourage students to protect the environment or support harmful practices (Stibbe 2021). From this perspective, textbooks are more than just pedagogical tools. They carry powerful messages that influence how students understand and interact with the environment.

While many studies have explored how environmental messages are multimodally constructed in textbooks, research in Indonesia has largely focused on linguistic and content analysis of environmental themes in educational materials. More recently, there is a growing body of studies that examine stories which underline environmental education using multimodal analysis combined with ecolinguistics in primary (Tatin et al. 2024) and selected secondary textbooks (Triyono et al. 2023). These studies have given useful insight into how environmental education is presented visually and linguistically. However, there remains a gap in the comprehensive application of multimodal critical discourse analysis to examine how social actors, social actions, and settings are represented in EFL (English as a Foreign Language) textbooks at the secondary level. In fact, these elements are crucial in shaping how students perceive their roles and responsibilities in relation to the environment. They also potentially serve as role models and influence students’ awareness.

This study addresses the gap by applying multimodal critical discourse analysis (MCDA) within an ecolinguistic perspective to investigate how Indonesian EFL textbooks represent eco-awareness. The present study is guided by the following research questions: (1) In what ways are the representations of social actors, social actions, and settings constructed through visual and linguistic elements in the textbooks, and what ideologies do these representations carry? (2) What worldviews are reflected in the representations of social actors, actions, and settings in the textbooks? By exploring these aspects, the present study aims to reveal the worldviews embedded in educational materials and support the development of language education that is more ecologically aware.

2 Literature review

Research on how the environment or nature is represented in school textbooks has been widely conducted across the globe. Some studies have focused specifically on content analysis that examines how environmental messages are included in educational materials. For instance, Liu et al. (2024) investigated 12 series of English language textbooks used in Chinese universities. They found that the textbooks addressed key environmental semantic domains such as nature, technology, agriculture, and living beings. Sustainability topics were also critically discussed to promote students’ knowledge, competencies, and future-oriented attitudes toward environmental challenges. In another study, Ekasiswi and Bram (2023) investigated five government-published textbooks. Their findings showed that ecolinguistic elements appeared in only three of the five textbooks. Pratiwi et al. (2021) conducted a content analysis of environmental themes in BIPA (Indonesian Language for Foreign Speakers) textbooks. This study revealed the presence of environmental themes, eco-lexicons, and euphemisms in the BIPA textbooks under investigation. These studies highlight that content analysis helps identify what environmental topics are prioritized, marginalized, or omitted in school textbooks.

Another stream of ecolinguistics studies emphasizes linguistic analysis. Most studies take a critical orientation in their analyses and emphasize the biases in the way textbooks represent environmental problems or ecology. To name a few, Stibbe (2004) examined the presence of shallow environments in Japanese ELT textbooks. Meanwhile, Akçesme (2013) investigated ELT coursebooks used globally and discovered that nature was constructed in multiple ways and how various representations promoted certain eco-ideologies. Zahoor and Janjua (2020) analyzed how nature was represented in ELT textbooks used in Pakistani schools and revealed that the relationship of humans and nature in the textbook underscored an anthropocentric worldview. Likewise, Ma (2023) investigated Chinese language textbooks and highlighted how elements of nature were interconnected in the texts. He and Shen (2023) examined the discursive representations of non-human animals in primary school Chinese language textbooks. Lee (2023) examined Chinese language textbooks for ethnic Koreans. The study found that these materials tended to shift environmental blame to the global community and oversimplify pollution causes. Furthermore, they aligned with corporate and state interests while overlooking the impact of pollution on local citizens and students.

More recently, researchers have employed multimodal analysis to examine how various semiotic resources work together to construct environmental discourses. Lee and Nguyen (2024) investigated environmental literacy in Vietnamese ELT textbooks and found that environmental literacy was shallow, human-centred, and focused on economic and technological solutions with little emphasis on behavior change and a misleading view of environmental harm. Lee and Kang (2023) analyzed textbooks for ethnic Koreans in China. These materials emphasized behavioral change and environmental knowledge but avoided current issues. The study also highlighted a pattern of blaming groups and called for integrating more critical perspectives into education. In the Indonesian context, Triyono et al. (2023) revealed that selected government-issued EFL textbooks promoted eco-beneficial discourses and suggested a growing environmental consciousness in educational policy. Similarly, Tatin et al. (2024) examined Indonesian elementary EFL textbooks and revealed that the textbooks include some environmental education, but the content remained largely anthropocentric. The study emphasized the limited student engagement and called for a stronger integration of ecolinguistic perspectives to enhance environmental learning outcomes.

Despite these valuable contributions, notable gaps remain particularly in the Indonesian context. Some previous studies have examined how images and text construct narratives in government-issued EFL textbooks. However, only a few have applied a comprehensive approach like multimodal critical discourse analysis to explore how social actors, social actions, and settings are represented at the secondary school level. In fact, these elements are crucial in shaping how students perceive their roles and responsibilities in relation to eco-awareness. In response to this, the present study offers a new perspective. It applies multimodal critical discourse analysis within an ecolinguistic framework to analyse how these elements are portrayed in Indonesia’s latest government-issued EFL textbooks for Indonesian secondary schools. This study also investigates the stories or worldviews embedded in these representations.

3 Theoretical foundations

3.1 Discourse(s) and representation

The term “discourse” has been defined in various ways. Broadly, it refers to oral and written texts used for meaningful communication (e.g. Canning and Walker 2024). However, this study adopts van Leeuwen’s (2015) conceptualization as a starting point. Discourses are defined as socially constructed ways of aspects of the world. In this sense, discourses are shaped by social context and reflect the interests of people involved in the social context (van Leeuwen 2005). Fairclough (2003) explains that discourses do not reflect reality exactly as it is. Instead, they construct possible versions of reality that may differ from the actual world. This means the same object or event can be represented in different ways, depending on the context and the interests of the people. Thus, discourses can be understood as a form of social practice.

Discourses can be expressed in different forms. As van Leeuwen (2005) explains, they may take a certain representation such as speech, writing, or action. The term “representation”, according to Hall (1997), refers to the process of creating meaning in the mind. This meaning is made real through language or other semiotic modes such as images and gestures. In other words, language and semiotic resources are used to create “meaningful signifiers to what we want to represent” (Heritage and Taylor 2024: 5). For example, Ponton (2022) demonstrates how language and images are carefully selected to represent narratives of industrial destruction and natural recovery in the Priolo site. Such representations are never neutral. They convey social and ideological stances. As Heritage and Taylor (2024) further argue, constructing representations is part of social practice. Consequently, representations can normalize viewpoints about social groups or issues.

This study views discourses as a socially constructed way of representing the world. It reflects the views and interests of certain groups of people within specific situations. Building on the works of van Leeuwen and Fairclough, this study sees discourses as a form of social practice which creates meanings through language and other forms of communication. These meanings are shaped by social contexts and particular beliefs.

3.2 Multimodal critical discourse analysis

Multimodal critical discourse analysis, as Machin and Mayr (Machin and Mayr 2023; see also Machin 2013) describe, is an approach that integrates critical discourse analysis/critical discourse studies (CDS) and multimodality. As a critical approach, CDA/CDS investigates how discourses are used to maintain or challenge power, expose ideologies, and shape social relations (see van Leeuwen 2015; Weiss and Wodak 2003; Wodak and Meyer 2015). Originally, CDA/CDS focuses primarily on texts and talks. It scrutinizes how words and clauses in political speeches, media, school textbooks, and everyday conversations reflect underlying social issues or perpetuate inequalities (e.g. Chilton and Schäffner 2003; Martin and Wodak 2003). However, CDA/CDS now extends its analysis by incorporating other semiotic modes (e.g. Lassen et al. 2006; van Leeuwen 2008) as discussed in the field of multimodality (Ledin and Machin 2020; Kress and van Leeuwen 2021). This expansion plays a major part in contemporary communication since modern media often combine various semiotic modes to construct meaning.

The combination of multimodality and CDA/CDS creates a powerful framework called MCDA. This approach enables a comprehensive examination of meaning-making in contexts where language alone does not capture the full message. The purpose of this approach is to denaturalize representations of other semiotic modes. In other words, it examines the kinds of “ideas, absences, and taken-for-granted assumptions” in images, texts and others with the purpose of revealing the kinds of power interests manifested in them (Machin and Mayr 2012: 10). In images, for instance, features such as vectors, shot size, gaze, and camera angle play an important role. Vectors refer to lines of movement within the image and suggest that an action is taking place. Shot size can indicate how emotionally close or distant viewers are positioned in relation to the represented participants in images. Gaze can suggest whether viewers are invited to engage directly with the given images. Camera angle can reflect the level of power or involvement with viewers (see Kress and van Leeuwen 2021). As exemplified by van Leeuwen (2008: Ch. 8), these visual tools are useful for exploring how people and their actions are represented.

Several analytical frameworks are commonly employed in MCDA including representing social actors, social actions (Machin and Mayr 2023; van Leeuwen 2008) and settings (Ledin and Machin 2018). The analysis of social actors and actions is carried out to investigate the detailed pattern of how participants are depicted in the textbook and agency attributed to the actors. Due to space constraints, the analysis of social actors, actions, and settings focuses only on selected features as discussed below.

3.2.1 Social actors

In analyzing discourse, particular attention is given to how participants in social events are represented through language and image. These participants referred to as social actors are individuals or groups engaged in social practices whose presence or absence in a text can reflect underlying social and ideological meanings (van Leeuwen 2008). In both visual and linguistic representations, social actors can be either included or excluded from a text (Machin and Mayr 2023; van Leeuwen 2008). Exclusion occurs when social actors are not shown or mentioned. In this way, there is no visual or textual reference in images or written content. This strategy generally is a meaningful choice as it can influence how readers understand who is important and who is not. In contrast, inclusion means that social actors are clearly shown or mentioned in the text. When included, they can be represented in different ways. They may appear as individuals (individualized) which highlight their personal action and identity or as part of a group (collectivized) which emphasizes shared roles or experiences. Additionally, they can be represented in a general way (generic) which is realized through broad terms such as students and people or a specific way (specific) in which individuals are clearly named or identified.

3.2.2 Social actions

While the representation of social actors has received considerable attention, it is equally important to examine how social actions are portrayed across different modes of communication. Social actions refer to the activities, behaviors, or processes carried out by social actors within a given context. These actions can be represented visually or linguistically. Unlike social actors, social actions are differently represented in visual and linguistic modes. According to Kress and van Leeuwen (2021), social actions can be visually classified into two types, namely narrative and conceptual processes. Narrative processes show actions or events that happen over time. They can be further divided into two types, namely agentive and non-agentive (also called conversion). Agentive processes involve actions where an actor is clearly performing an activity. These align with Halliday and Matthiessen’s (2014) types of processes such as material, behavioral, mental, and verbal processes. In contrast, non-agentive processes refer to actions shown in an abstract way such as in diagrams or charts where no clear actor is involved. On the other hand, conceptual processes do not show actions but focus on the representation of ideas, structures, or relationships. These are usually realized through classification (grouping things), analytical processes (showing part-whole relationships), and symbolic processes (showing meaning or identity). Each type of process plays a different role in shaping how information and meaning are constructed in both images and written texts.

In language, social actions can generally be divided into two main types, namely actions and reactions. According to van Leeuwen (2008), actions include material actions which can be either transactive (where an actor does something to someone or something) or non-transactive (where there is no clear goal or target). Actions also include semiotic processes which can be behavioral (related to physical or social behavior) or non-behavioral (such as showing, quoting, or describing something using circumstances or prepositional phrases). In contrast, reactions refer to responses and can be categorized as unspecified, cognitive (about thinking), affective (about feelings), or perceptive (about sensing). These actions and reactions can be expressed in either active or deactivated forms. When activated, they appear in the verbal group of a non-embedded clause which is clearly showing who is doing what. When deactivated, they are expressed through nominalization (turning actions into nouns) or epithets (descriptive phrases) for nouns which can obscure actors or make actions appear more abstract.

3.2.3 Settings

In addition to the representation of social actors and their actions, it is important to consider the role of contextual elements in both visual and written texts. Among these, the setting plays a significant role in helping audiences interpret what they see or read. Typically, social actors and their actions are accompanied by various types of circumstances that provide additional context to what is being shown. One important type is setting. As Ledin and Machin (2020) explain, settings are not merely background elements. They carry cultural meanings and show shared ideas in society. Settings help situate the action in a familiar context which can shape how people understand the message. However, sometimes images may lack this context and appear decontextualized. It means the background is intentionally removed. This way allows props or objects to be shown in ways that would not be possible in real-life environments and change the meaning of the images. In contrast, contextualized settings include visual or textual details that help viewers recognize and make sense of the environment. Settings operate on both denotative and connotative levels. On the denotative level, they show the physical location where something happens such as a classroom, city street, or farmland. This level simply provides information about the location. On the connotative level, settings carry deeper symbolic or cultural meanings. For example, a classroom may represent more than just a learning space. It might also suggest authority or formal education. How people interpret this depends on the cultural context.

In summary, settings function more than physical locations. They are culturally meaningful elements that influence how viewers understand the actions and messages in a text. Whether contextualized or decontextualized, they contribute to both the literal and symbolic meanings of a representation.

3.3 Ideology and ecosophy

Ecolinguistics emerges as a critical analysis of language using a certain theoretical framework that examines how the natural world and human-nature relations are constructed (Bellewes 2024; Cavallaro 2024; Steffensen 2024, 2025; Zhdanava et al. 2021). The analysis in this field goes beyond simply describing texts. It further investigates how certain linguistic choices influence people to reflect on and treat the environment and unearths the stories that lead to ecological destruction or nature protection (Stibbe 2014, 2021). Alternatively stated, ecolinguistics particularly focuses on how language and other semiotic modes can either perpetuate destructive environmental practices or promote more sustainable relationships with nature.

Ecolinguistics provides specific analytical tools for examining how language and other semiotic modes shape our understanding of environmental issues (Steffensen 2024, 2025). Ma and Stibbe (2022) and Stibbe (2021) outline several cognitive frameworks that help investigate ecological discourse. These include ideology, framing, metaphors, evaluation, identity, conviction, erasure, and salience. Ideology is “a belief system about how the world was, is, will be, or should be which is shared by members of a group” (Stibbe 2021: 224). In ecolinguistics, when studying ideology, linguists analyse the linguistic or other semiotic manifestations in discourses to see whether they encourage people to destroy or nurture the ecosystems that support life. As Stibbe (2024) describes, ecolinguistics should reveal whether the discourses are categorized as destructive discourses that normalize harmful practices or ignore environmental issues, beneficial discourses that support sustainable and respectful relationships with nature, or ambivalent discourses that have mixed effects. This ecolinguistic analysis demystifies how textbooks unconsciously support worldviews that sustain environmental degradation such as consumerism or anthropocentrism (human-centred thinking). At the same time, it also supports discourses that value biodiversity and conservation as well as reflect biocentrism (life-centred thinking). It should be noted here that there are no objective ways to decide whether discourses are destructive, ambivalent, or beneficial.

Ecolinguists rely on the ecosophy that they hold dear to judge whether the discourses align with their ecosophy or work against it. Accordingly, the notion of ecosophy is central to ecolinguistics. Ecosophy, a shortening of ecological philosophy, is a set of philosophical frameworks that includes environmental values and principles to guide how humans interact with nature (Naess 1995). Ecosophy plays an important role in ecolinguistics. When conducting analysis, ecolinguists should use their ecosophy as a guideline for conducting analyses and making judgments on the discourses under investigation (Xue and Xu 2021). Stibbe (2024) further describes that an ecosophy provides the basis for determining whether the discourses promote action to nurture living beings or ecosystems (beneficial), promote action that harms individuals and ecosystems (destructive), or promote both beneficial and destructive aspects (ambivalent). This study follows the ecosophy of “Living!” from Stibbe (2021, 2024) as a criterion to examine how Indonesian EFL textbooks represent environmental awareness. This ecosophy aims to cherish different forms of life and to appreciate environmental boundaries, resilience, and social justice.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research method

This study employs a qualitative case study research design since it explores a single case (i.e. the stories and worldviews behind the representation of eco-awareness) in depth within its context (Creswell and Poth 2018), that is, in an educational setting. To present an in-depth exploration, the study adopts MCDA integrated with ecolinguistic perspectives. MCDA offers a more comprehensive analytical lens by examining how text, images, and design interact to construct meanings within discourses (Kress and van Leeuwen 2021; Weninger 2020). Unlike basic content analysis in ecolinguistics, MCDA reveals hidden ideologies, emotional appeals, and subtle anthropocentric biases embedded in both language and images (Machin and van Leeuwen 2016). In this context, MCDA examines how various semiotic resources work together to represent environmental awareness in Indonesian EFL textbooks. For this reason, MCDA is especially useful for identifying how textbooks may promote or undermine eco-awareness among students.

4.2 Data collection

The data were taken from Indonesian EFL textbooks used in secondary education, specifically focusing on textbooks issued by the Ministry of Education for grades 10–12. The textbooks are selected based on the following criteria: (1) their current use in Indonesian secondary schools, (2) their adherence to the most recent national curriculum, namely Kurikulum Merdeka (‘Freedom Curriculum’), and (3) their incorporation of environmental topics or themes. Five textbooks were chosen for analysis in this present study. These textbooks represent different grade levels to ensure a comprehensive representation of how environmental awareness is represented in Indonesian EFL education.[1] The data collection procedures include the identification and documentation of environmentally related content in these textbooks. This encompasses (1) chapters that are specifically designed to address environmental themes; (2) visual elements that illustrate nature or environmental concerns; and (3) textual elements (captions and labels) that accompany visual elements. Each identified element is digitally documented using a database, along with their contextual information, such as unit theme and page.

4.3 Data analysis

This study integrates MCDA with ecolinguistic perspectives. This approach can help facilitate a fine-grained analysis of images and their related texts while considering their wider social and ecological implications. The analysis is carried out in three main stages. The first phase examines discursive strategies used to represent environmental issues. This includes identifying key elements such as social actors, social action, and settings. The second phase investigates how such representations are used to construct environmental meanings within texts. The last phase focuses on analyzing the ideological implications of multimodal choices and stories. As previously stated, the analysis uses Stibbe’s (2021) ecosophy “Living!” to evaluate whether the identified patterns contribute to beneficial, ambivalent, or destructive environmental stories. This integrated approach allows for a deeper understanding of the ways environmental awareness is presented in educational materials and highlights the underlying ideologies that may influence students’ views.

5 Findings and discussion

5.1 Representation of social actors

The authors and illustrators of the textbooks use social actors as one of the representational choices to show environmental awareness. Both visual and linguistic social actors are observed in this study. Table 1 shows how social actors are visually represented in Indonesian EFL textbooks. The data show that inclusion strategies (38 instances or 67 %) are more prevalent than exclusion strategies (19 instances or 33 %). This finding indicates a general tendency to visually represent social actors rather than omit them. Among the inclusion types, generic representations (26 occurrences or 68 %) are more common than specific ones (12 occurrences or 32 %) (see Table 2). This suggests that the textbooks prefer to show social actors in general, likely to make the content more relatable for students from different backgrounds. Additionally, individualized and collectivized representations appear equally (see Table 3). The equal frequency of individualized and collectivized visuals also indicates an effort to balance personal and group representation.

Visual representation of social actors in Indonesian EFL textbooks.

| Strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusion | 19 | 33 % |

| Inclusion | 38 | 67 % |

Visual representation of social actors in terms of generic and specific actors.

| Inclusion strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Generic | 26 | 68 % |

| Specific | 12 | 32 % |

Visual representation of social actors in terms of individualized and collectivized actors.

| Inclusion strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Individualized | 19 | 50 % |

| Collectivized | 19 | 50 % |

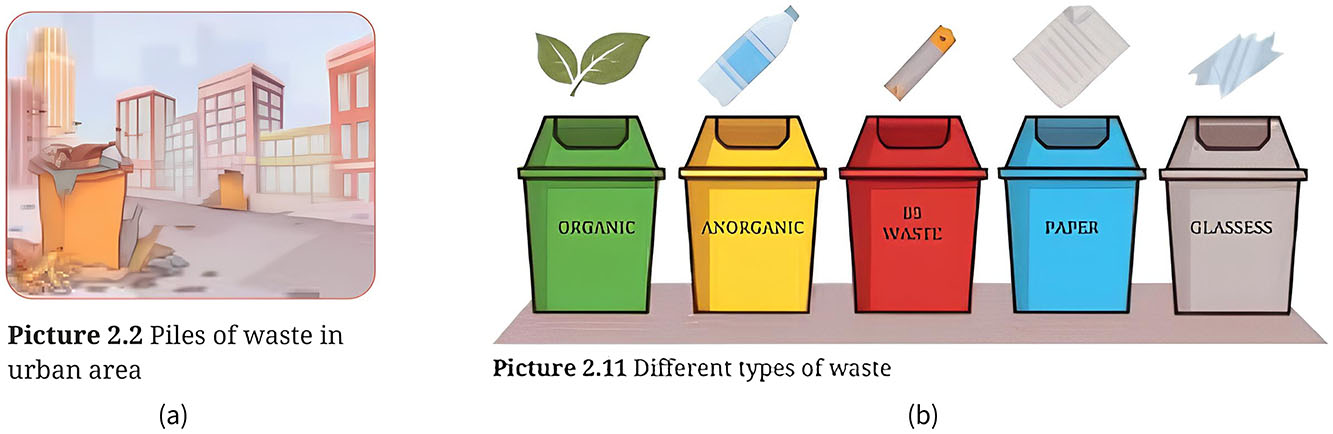

In some cases, social actors are entirely excluded as illustrated in Figure 1(a). The image shows a school corridor with an overflowing rubbish bin and litter scattered on the floor. However, it does not show who is responsible for the mess. This absence of agency demonstrates how exclusion occurs through the omission of those who contribute to the untidiness of the school environment. A similar form of exclusion is evident in the depiction of environmental degradation as shown in Figure 1(b). The image displays factories, industrial sewage, vehicles, and piles of waste. The image suggests an unhealthy environment and symbolizes pollution and environmental damage. This visual representation carries a strong negative message about the consequences of human industrial activities and emphasizes pollution as a dominant aspect of the landscape. However, the image does not show the individuals or groups responsible for this damage. The powerful actors responsible for these industrial practices are absent. As a result, this representation reinforces the exclusion of key social actors and shifts the focus away from human accountability.

Exclusion of social actors in school areas and polluted surroundings ((a) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 62; (b) excerpted from Afrilyasanti 2021: 131).

In contrast, some instances in the textbooks present social actors, particularly when promoting positive actions such as environmental change as shown in Figure 2. The examples show how inclusion is used to highlight responsibility and positive behavioral change. In such representations, social actors may be portrayed as individualized or collectivized. For instance, Figure 2(a) shows a woman alone in a natural setting. It is captured from a long shot which enables viewers to clearly see the actor and her surroundings. Importantly, there is no direct gaze between the represented participant and viewers. This lack of eye contact indicates that the image is intended to provide information. As Kress and van Leeuwen (2021) explain, this type of image is categorized as an offer rather than a demand. It means the image invites the viewers to observe rather than participate. This choice highlights an individualized representation which emphasizes personal responsibility and agency to address environmental problems. By focusing on a single person in natural settings, the image invites viewers to see themselves as capable of making meaningful contributions to environmental sustainability.

Inclusion of social actors in terms of individualized actors and collectivized actors ((a) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 62; (b) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 167).

Social actors are also visually represented as a large group which is commonly shown in long shots and from frontal angles. The use of long shots enables viewers to clearly observe the entire group against the background, which often serves to emphasize collective action. This perspective tends to minimize individual distinctions and instead highlights social cohesion and unity. This depiction creates a sense of uniformity or the impression that “they are all the same” (van Leeuwen 2008: 146) due to similar poses and clothing. At the same time, the frontal angle positions the viewer as directly facing the group which fosters a sense of involvement or engagement. For example, Figure 2(b) shows a group of people participating in environmentally responsible activities and reflects the concept of collectivized social actors. This representation highlights shared responsibility for environmental care and places greater emphasis on community participation over individual agency. Furthermore, by portraying social actors in this collective manner, viewers are encouraged to align themselves with the group and take similar actions to protect the environment. This visual element forms positive judgement (Economou 2012; Martin and White 2005) where viewers are invited to see their act as eco-friendly behavior.

Moreover, social actors are included in the textbooks as either generic or specific participants. Most of them are depicted with a direct gaze and a frontal angle. This creates a sense of direct engagement and positions viewers to face the represented actors. This visual choice helps promote a feeling of shared responsibility. Generic social actors are visually represented as groups of people. For example, Figure 3(a) illustrates a group of people engaged in environmentally responsible activities and reflects generic social actors. In contrast, specific social actors are portrayed visually as identifiable individuals. For instance, Figure 3(b) shows a girl standing amidst piles of plastic waste which represents a specific participant. In this context, she is primarily defined by her functional role in which she acts against environmental pollution rather than by personal characteristics. Such representation frames her as a committed individual who is actively working to address a serious environmental issue.

Inclusion of social actors in terms of generic actors and specific actors ((a) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 62; (b) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 62).

Tables 4, 5 and 6 display the linguistic representation of social actors in the same textbooks. Unlike the visual content, the written texts show more exclusion (20 instances) than inclusion (25 instances) (see Table 4). This finding indicates that social actors are more often omitted or backgrounded in written texts. Within the inclusion strategies, individualized actors (15 occurrences or 60 %) occur more frequently than collectivized ones (10 instances or 40 %) (see Table 5). Similarly, generic participants (13 instances or 52 %) appear slightly more often than specific ones (12 instances or 48 %) (see Table 6). This pattern suggests that when social actors are linguistically included in the text, they tend to be presented as individual entities rather than groups. This representation may reflect an emphasis on personal agency or responsibility.

Linguistic representation of social actors in Indonesian EFL textbooks.

| Strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusion | 20 | 44 % |

| Inclusion | 25 | 46 % |

Linguistic representation of social actors in terms of individualized and collectivized actors.

| Inclusion strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Individualized | 15 | 60 % |

| Collectivized | 10 | 40 % |

Linguistic representation of social actors in terms of generic and specific actors.

| Inclusion strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Generic | 13 | 52 % |

| Specific | 12 | 48 % |

As shown in Table 4, it is recognized that social actors are also linguistically excluded in the textbooks. Exclusion is evident in phrases such as “piles of waste in urban areas”, “unorganized dust bin at school”, and “unhealthy environment”. In the first phrase, agency is unclear because it only mentions the object and its setting without identifying who created the waste. Similarly, the second phrase merely describes the location and omits the actor responsible for the disorganization. The third phrase refers to the consequence of certain actions, namely an unhealthy environment without specifying who is responsible for causing this outcome. These examples demonstrate how linguistic choices can obscure agency and effectively exclude the social actors behind environmental problems.

Inclusion can be identified through the presence of participants in the accompanying texts. Social actors can be included either as individuals or as members of a collective. For instance, the clause “a woman is planting flowers in the garden” presents an individualized actor whereas the phrase “young environmental activists” refers to collectivized social actors. Social actors can also be presented in a generic or specific way. Generic social actors are typically realized through plural forms such as in the clause “people are queuing at a waste bank”. The word “people” refers to a general group without specifying individuals. In contrast, specific social actors are identified through proper names as seen in “Aeshnina Azzahra”. In this case, the use of a name specifies the actor and adds a personal dimension to her role. It potentially fosters respect and admiration for her environmental efforts. This strategy of inclusion emphasizes agency and helps readers connect more deeply with the individuals or groups depicted.

To put it succinctly, the analysis of environmental awareness in the textbooks reveals social actors are represented selectively with a strong focus on including positive figures. Both visual and linguistic elements work together to construct idealized environmental identities. Through these representational choices, textbook authors seek to bring readers closer to individuals (Machin and Mayr 2023) who contribute to environmental protection. At the same time, these portrayals invite viewers to positively evaluate the depicted figures and build emotional connections with them (Economou 2009, 2012). While the textbooks promote caring for the environment, they mostly show students or general groups like “people” as the ones taking action. They rarely mention institutions or companies that also contribute to environmental problems. This pattern is similar to what Tatin et al. (2024) found in which students are presented as the main agents of change. However, such a focus might unintentionally downplay systemic causes of environmental issues and shift attention away from more powerful actors who play a significant role.

In ecolinguistics, the way people and actions are represented is important because it shapes how readers understand who is responsible for environmental problems and justice. This is not just a local issue. For instance, in the United States, Sharma and Buxton (2015) found that a science textbook for seventh-grade students in Georgia reduces the role of humans and presents environmental problems as if they happen on their own. Similarly, Mliless and Larouz (2018) found that English textbooks in Morocco do not mention institutions as major contributors to environmental harm. Gugssa et al. (2021) also observed that English textbooks in Ethiopia often hide human involvement in causing environmental damage. These studies reflect a broader pattern in educational materials across countries. Textbooks emphasize individual responsibility for environmental care, while the role of institutions and larger systems is rarely discussed. Such an approach can unintentionally promote the idea that powerful groups are not responsible, while ordinary people such as students and the general public are expected to carry the burden of solving environmental problems.

5.2 Representation of social action

Social actions are represented in the textbooks under investigation. These actions indicate how agency is distributed in the materials. An analysis of social actions helps identify the roles and responsibilities assigned to individuals or groups. In the images, social actions are presented through three main types: conceptual, agentive, and non-agentive (also known as conversion) representations as shown in Table 7. In the written texts, social actions are described either through what people do (actions) or how they respond (reactions). These can be further divided into two categories. They are called activated when the actors are clearly shown doing something, and deactivated or deactivated when the actors are backgrounded as presented in Table 8.

Visual representations of social actions in Indonesian EFL textbooks.

| Strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual | 16 | 28 % |

| Non-agentive (conversion) | 6 | 10 % |

| Agentive | 35 | 62 % |

Visual representation of social actions in terms of agentive actions.

| Agentive strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Material | 24 | 69 % |

| Mental | 1 | 3 % |

| Verbal | 1 | 3 % |

| Behavior | 9 | 25 % |

Table 7 indicates that the most frequently used visual strategy is the agentive type which appears 35 times. Within this category, material processes where people are shown doing physical actions dominate with 24 occurrences (69 %). It is followed by behavioral (9 instances or 25 %), mental (one occurrence or 3 %), and verbal (one occurrence or 3 %) processes. Conceptual visuals which usually do not show action and focus on classifying or identifying occur 16 times (28 %). Meanwhile, non-agentive (conversion) visuals where actions are shown without a visible actor appear only 6 times (10 %). This suggests that Indonesian EFL textbooks often portray individuals or entities doing concrete actions. The strong focus on doing rather than thinking or feeling implies that the images may give more importance to showing eco-friendly behaviors than to encouraging students to think deeply or talk about environmental issues.

One of the most common visual representations of social actions in the textbooks is the depiction of action as illustrated in Figure 4. These actions are generally categorized as either transactive where actions have a clear effect on others or non-transactive where the actions do not directly affect others or the environment. For instance, Figure 4(a) shows two people weighing plastic waste. One holds the waste and the other uses the scale. This scene foregrounds a clear interaction between the actors and the objects (the plastic waste and the scale) and illustrates a transactive material process. The image highlights specific and goal-oriented actions related to waste management and presents social actors as active participants in environmental solutions.

Visual social actions in terms of transactive action and non-transactive action ((a) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 74; (b) excerpted from Sunengsih et al. 2022: 111).

The study also found that some visual elements depict social actors engaged in non-transactive material processes as illustrated in Figure 4(b). These actions are classified as non-transactive because they do not involve clear interaction with other people or objects that leads to a visible result (van Leeuwen 2008). In this image, the actor is snorkelling, namely an activity that focuses on personal enjoyment. There is no sign of meaningful interaction with the environment in this activity. The action is thus considered non-transactive because it is performed for pleasure rather than interaction with the surroundings. As a result, nature is mainly shown as a scenic backdrop for personal recreation. This representation supports Akçesme’s (2013) findings which show that nature is often shown as a source of aesthetic pleasure. In this view, the natural environment is seen more as something to enjoy visually than as something to care for or engage with.

The study also reveals that some social actors are visually depicted through behavioral processes. In Figure 5(a), for example, a woman is standing next to an elephant and gently touching it. Her smile and gentle movement suggest that she cares about the animals and shows respect for wildlife. The visual details such as her facial expression, smile, and gesture can be interpreted as signs of behavioral processes as described by van Leeuwen (2008). The use of a frontal angle and close-up shot help highlight her emotional involvement and position her as open and approachable. This perspective allows viewers to engage more personally with the actor and feel emotionally connected to the scene. It also invites viewers to see her in a positive light and creates a sense of empathy and social credibility. Furthermore, it allows viewers to associate her actions with genuine concern for the environment.

Visual social actions in terms of behavioral processes ((a) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 172; (b) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 154).

Figure 5(b) also illustrates a behavioral process. The image depicts a girl holding a traditional musical instrument in a natural setting. Her calm facial expression and the gentle way she holds the instrument suggest that she respects both her cultural heritage and the natural environment. Her smile, as noted by van Leeuwen (2008), conveys emotion or feeling. Her traditional clothing and calm appearance further position her as someone who proudly represents her cultural identity. The direct gaze between the represented actor and viewers creates a personal connection and makes the viewers feel directly addressed. This gaze invites viewers to connect with the image and the values that it represents such as cultural pride and environmental awareness. The medium shot which clearly shows her upper body and face adds emotional impact and builds a sense of trust and sincerity.

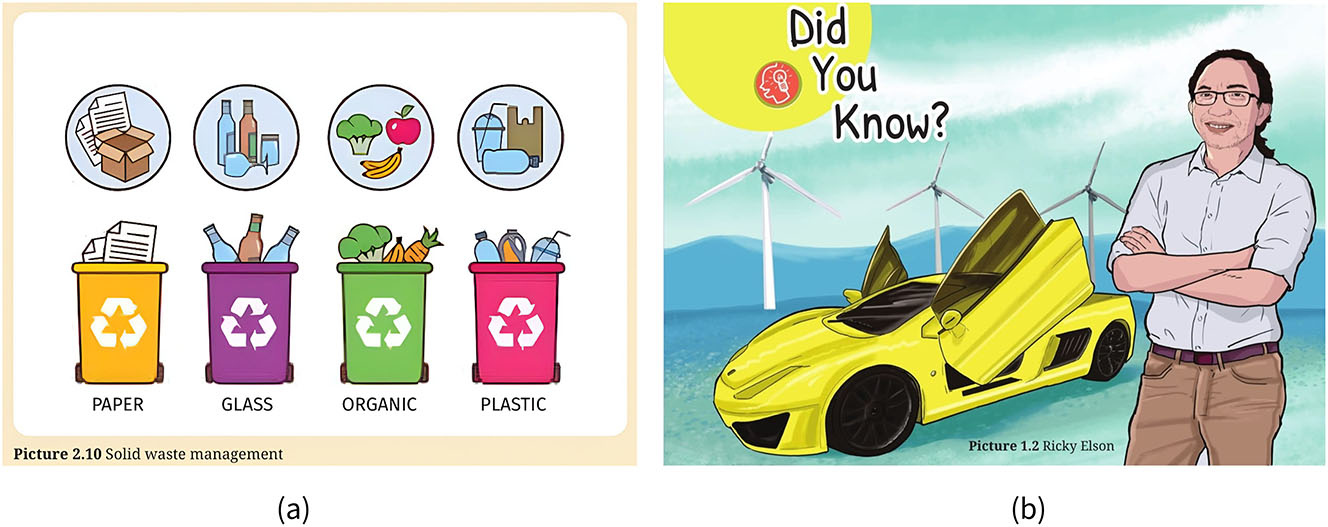

Some images in the textbooks illustrate conceptual processes. These types of visuals focus on ideas, activities, or prominent figures rather than showing people as active participants. For example, Figure 6(a) shows how waste is sorted based on type but the people doing this are not shown. This makes the action seem separate from any individual and forms depersonalization. This type of visual representation emphasizes the process rather than agency. In Figure 6(b), the authors use conceptual visuals to link well-known figures to environmental actions. However, these figures are shown symbolically rather than actually doing something. As a result, these representations may oversimplify environmental commitment and ignore the challenges of real-life involvement.

Conceptual processes in terms of classificational process and analytical process ((a) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 64; (b) excerpted from Hardini et al. 2022: 3).

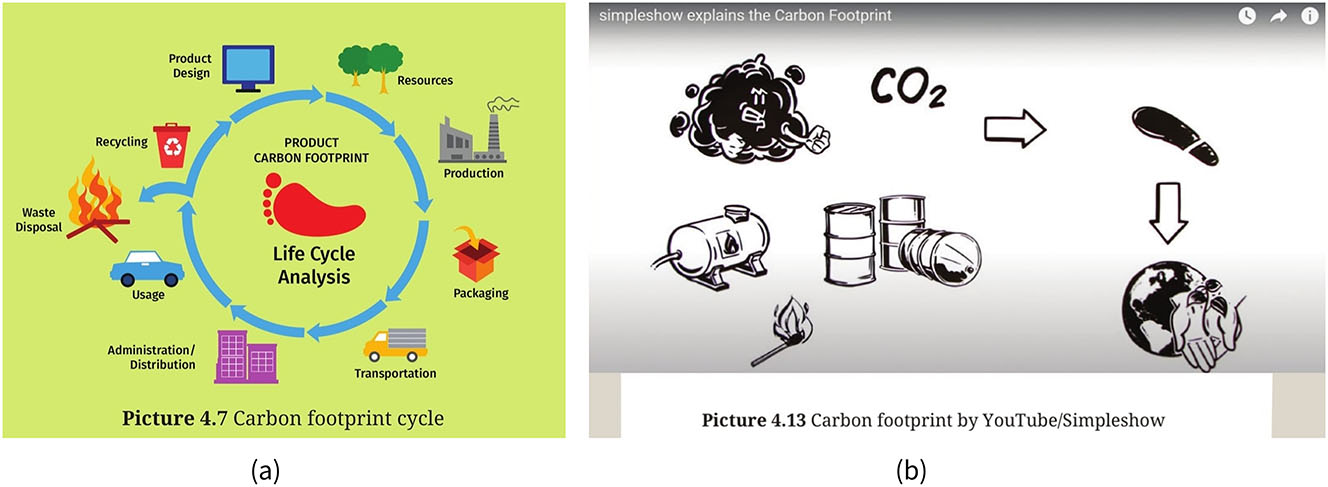

Some social actions are represented as non-agentive, which are also known as conversion processes. In these cases, actions are shown without showing the responsible actors as illustrated in Figure 7. For example, Figure 7(a) presents a circular diagram which visualizes a sequence of activities connected by arrows. This design gives the impression of a repeated cycle and implies that carbon emissions are a recurring and systemic issue contributing to global environmental problems. However, a closer examination reveals that the agents who are responsible for these activities are entirely absent. The absence of human beings constructs the cycle as an automatic and inevitable process. Such representation can lead viewers to perceive environmental degradation as a natural part of modern life rather than the result of specific human choices. As a result, the image may reduce the viewers’ responsibility and lessen the urgency to make meaningful changes.

Conversion processes ((a) excerpted from Hardini et al. 2022: 154; (b) excerpted from Hardini et al. 2022: 183).

Similarly, Figure 7(b) provides another example of a conversion structure. In this image, the sources of CO2 emissions are explicitly labeled and arrows are used to show how these sources lead to environmental damage. The arrows function as vectors and create a clear and linear progression that simplifies the process of pollution for viewers. Although the diagram shows specific activities that contribute to carbon emissions, it tends to obscure the deeper systemic factors such as government rules, business practices, and economic systems that drive these activities. In other words, the image does not address why society continues to rely on fossil fuels or why large-scale factory farming continues. This narrow perspective may lead viewers to believe that environmental problems are mainly caused by personal choices and oversimplifies the issue. Ultimately, such representation may reduce critical reflection on broader structural causes and emphasize the notion that environmental responsibility lies primarily with individuals.

Table 9 presents how social actions are represented through language in the analyzed textbook. The most frequently observed strategy is action which occurs 32 times. This occurrence indicates a strong emphasis on doing or performing activities through language. On the other hand, reaction appears only once. This suggests emotional responses receive very little attention. In terms of how actions are presented, activation (where the actor is clearly shown) occurs 19 times while deactivation (where the actor is hidden) appears 14 times (see Table 10). This occurrence shows a relatively balanced use of both. These findings show that the textbooks tend to emphasize action and agency in their written content. This probably aligns with pedagogical goals that aim to get students actively involved and relate such actions to their everyday activities.

Linguistic representations of social actions in Indonesian EFL textbooks.

| Strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Action | 32 | 97 % |

| Reaction | 1 | 3 % |

Social action modes in Indonesian EFL textbooks.

| Strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Activation | 19 | 54 % |

| Deactivation | 14 | 46 % |

Linguistically, action is mainly conveyed through material processes such as “weighing plastics”, “queuing at the waste bank”, “sorting waste”, “compiling sorted waste”, and “a granny planting some trees”. These actions mostly involve ordinary people or students and emphasize environmentally responsible behavior through goal-oriented activities. In some cases, actions are expressed through behavioral processes such as “watching TV” or “students watching a video on a cell phone”. These actions show passive involvement where people learn about the environment by watching rather than doing something. Compared to the images, the linguistic representation of social actions is more limited and shows simpler actions. The captions merely describe what is seen without giving much detail or encouraging deeper thinking. As a result, the texts often lead to only a basic understanding of caring for the environment and miss the opportunity to encourage more active engagement.

In addition, the actions in the accompanying texts are presented through activation and deactivation. Activated actions are marked by verb phrases in main clauses (van Leeuwen 2008: 63) such as in “students calculated their carbon footprint” or “a female student booked an online means of transportation”. These constructions attribute actions to specific actors and make the agency visible. However, some actions are also deactivated. A common form of deactivation occurs through nominalisation where verbs are turned into nouns as seen in phrases like “solid waste management” and “diet emission”. Such nominalized forms obscure the actors responsible for the actions and reduce transparency. Deactivated actions also appear in descriptive forms, particularly through epithets (adjectives). Examples from the data include “polluted beach”, “unorganized rubbish bin at school”, “organized and unorganized waste”, and “the polluted Indonesia”. In these cases, adjectives like polluted, unorganized, and organized draw attention to the result or condition of something, but those mask the agents behind them. This linguistic strategy distances the actors from responsibility and limits critical engagement with the causes of environmental problems.

The analysis of the textbooks reveals a strong emphasis on actions in environmental care. These actions are typically represented through material and behavioral processes which involve students or ordinary people. In the images, social actions are often clearly depicted so that those provide a sense of agency and direct involvement. However, the accompanying texts tend to offer a more limited representation. Linguistically, agency is frequently omitted and obscured through nominalization and epithets which describe outcomes without identifying responsible actors. This creates a mismatch between the pictures and the text. The images show people actively caring for the environment, but the texts often describe these actions in a vague or passive way. This makes the message less powerful.

These findings align with a growing body of research that criticizes how school textbooks or learning modules place the blame for environmental problems on individuals while neglecting systemic, institutional, and economic contributors to ecological degradation. For instance, Zhu (2024) highlighted how grammatical structures like nominalization and passive voice in environmental discourse obscure agency and reduce the sense of responsibility among readers. Similarly, Pratolo et al. (2024) found that English textbooks tend to promote individual responsibility for environmental issues without considering broader social, political, and economic structures. This strategy enables powerful actors such as industries and governments to avoid taking responsibility and put the responsibility on individuals to protect the environment. Moreover, research in ecolinguistics emphasizes how language choices can remove the human element from environmental problems and shift attention away from those truly responsible.

5.3 Representation of settings

The analysis shows that settings are clearly observed in the textbooks. Some images provide detailed environmental backgrounds known as contextualized settings. The settings are constructed through elements such as objects, shots, angles, and composition that communicate wider meanings. In contrast, some images present decontextualized settings in which the background is intentionally removed and leave only key objects such as pollution, waste, or factories which are isolated from any surrounding environment. Notably, this setting appears only observed in images. Table 11 gives a summary of these findings.

Visual and linguistic representations of settings in Indonesian EFL textbooks.

| Settings | Visual texts | Linguistic texts | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |

| Contextualized | 42 | 72 | 20 | 100 |

| Decontextualized | 16 | 28 | – | 0 |

Table 11 displays the distribution of contextualized and decontextualized settings in visual and linguistic texts from Indonesian EFL textbooks. In the visual texts, 42 instances (72 %) are contextualized while 16 instances (28 %) are decontextualized. In the linguistic texts, all 20 occurrences (100 %) are contextualized. This shows that contextualized settings are more prevalent than decontextualized ones across both modes of representation. This strong tendency suggests that social actions are typically represented with environmental or situational details that help students understand the context and meaning of the actions. The use of contextual elements such as background settings in images and descriptive language in texts reinforces the link between human activity and its environmental consequences. In contrast, the limited use of decontextualized visuals, where backgrounds are intentionally removed or simplified, may serve as a complementary strategy to draw attention to specific actions or ideas.

As a dominant visual feature, contextualized settings convey specific details about environmental problems as illustrated in Figure 8(a). This figure depicts a messy urban street with tall buildings, an overflowing trash bin, and scattered litter. Denotatively, it shows an untidy city street without any people present. Although the image appears to raise awareness of urban pollution, its visual choices can normalize environmental degradation and hide the social and political factors which contribute to it. This scene is captured from an oblique angle. As noted by Kress and van Leeuwen (2021), this angle connotatively creates a sense of distance and positions viewers as passive observers instead of involved participants. This perspective suggests emotional or moral detachment from the waste issue. The absence of people further removes a sense of responsibility and makes it appear as if no one is accountable for the problem. Consequently, the image may present urban pollution as an inevitable condition shaped by circumstance without acknowledging the role of human agency or institutional failure.

Contextualized settings and decontextualized settings ((a) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 56; (b) excerpted from Astuti et al. 2022: 65).

Some images in the textbook are presented in decontextualized settings where the original backgrounds are removed and replaced with a plain background. These design choices signal that the images are meant to present general ideas or concepts (Machin and van Leeuwen 2007) rather than real-life activities. As illustrated in Figure 8(b), different types of waste are displayed against a white background. This suggests that the image is intended to introduce the concept of waste categorization in a simplified and abstract form, rather than to show the actual process of sorting waste in a real setting. While such representations may support vocabulary development and conceptual understanding, they may also limit students’ ability to connect the topic to everyday environmental actions such as proper waste separation and disposal.

Linguistically, decontextualized settings were not identified in the present study. Instead, most of the settings are expressed in a contextualized manner as shown through prepositional phrases such as “piles of waste in urban areas”, “piles of waste in the house”, “piles of waste in the industrial area”, and “at the waste bank”. These phrases carry denotative meanings. It indicates specific physical locations where environmental issues occur. In addition, some expressions like “populated beaches” and “unhealthy environment” go beyond literal descriptions and convey negative connotations. These phrases suggest underlying problems such as overcrowding, pollution, or poor sanitation. The use of both denotative and connotative language strengthens the environmental message by grounding it in real-world contexts while also encouraging emotional and evaluative responses from readers. This linguistic strategy helps students not only understand where environmental problems take place but also how to interpret their seriousness.

The analysis of settings in the textbooks shows a common pattern in how environmental issues are represented. Some images use contextualized settings. It means that the environments are shown in detail and in ways that students can easily recognize and relate to. However, other settings are less recognizable or relevant to students’ daily experiences which may reduce their impact. Similar patterns were identified by Hansen and Machin’s (2008: 785) study which found that so-called “generic settings” in Getty Images were commonly used to represent environmental themes. The study also found several decontextualized settings where backgrounds are simplified or removed. These representations enable the information in this case environmental care and problems to be presented in abstract or conceptual ways (Hansen and Machin 2008; Machin and van Leeuwen 2007). While these strategies may aim to highlight key ideas, they can also hide the real processes and human roles behind environmental problems. As a result, the textbooks may unintentionally encourage a passive understanding of environmental issues, rather than fostering critical awareness and active engagement. This reflects a missed opportunity for EFL textbooks to support deeper and more participatory forms of environmental learning. These findings echo earlier research (Benjaminsen 2021; Hansen and Machin 2008; Wang and Liu 2024) which points to the decontextualization and aestheticization of environmental discourse especially in how settings are constructed.

5.4 Worldviews behind the representations

As previously mentioned, the ideologies identified through critical analysis are not inherently good or bad. They are considered good if they resonate with the analysts’ ecosophy while being bad if they contradict the ecosophy. This study uses the ecosophy “Living!” to assess the representations in Indonesian EFL textbooks. According to Stibbe (2021), this ecosophy positively values the well-being of all species, focuses on reducing consumption, or promotes resource redistribution. It views negatively any representation that treats people and other species as resources for exploitation and promotes unequal resource distribution. Table 12 summarizes how worldviews appear in the textbooks.

Worldviews occurrences in Indonesian EFL textbooks.

| Worldviews | Grade 10 | Grade 11 | Grade 12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |

| Beneficial | – | 0 | 23 | 64 | 9 | 41 |

| Ambivalent | – | 0 | 13 | 36 | 12 | 55 |

| Destructive | – | 0 | – | 0 | 1 | 4 |

Some representations of environmental themes in Indonesian EFL textbooks reflect an underlying worldview that promotes beneficial discourses. Those emphasize environmental care and responsibility. This can be seen in the portrayal of social actors who engage in eco-friendly activities such as planting trees or sorting waste. These actors are presented either as individuals or as a collective group in a positive way. When individualized, they are captured from frontal angles or presented using proper names. In this way, readers are encouraged to relate to these figures and their crucial personal action to protect the environment. On the other hand, when collectivized, they are depicted as anonymous groups and presented using plural forms in texts. This presentation fosters a sense of shared responsibility. These visual and linguistic choices foreground beneficial discourses since the semiotic choices promote empathy, encourage community action, and offer an optimistic perspective on environmental stewardship.

However, the beneficial discourses are not consistently maintained throughout all representations in the investigated textbooks. In some instances, social actors are excluded from scenes that depict environmental problems such as pollution and waste. Linguistically, this exclusion is often realized through nominalizations such as “waste management” and epithets like in “polluted beach” and “unorganized waste” which obscure the actors who are responsible for the actions. Visually, the absence of identifiable individuals or groups means it is unclear who is responsible for the environmental damage. This is further emphasized using oblique which creates a sense of detachment and positions viewers as a passive observer rather than an engaged participant. This combination of linguistic and visual contents creates an ideological tension. While the textbooks aim to promote environmental awareness, the exclusion of human agency and the distancing effects of the imagery reflect an ambivalent ecosophy. This may make it harder for students to critically engage with the root causes of environmental problems and understand their role in addressing them.

Furthermore, the strong emphasis on individual responsibility without sufficient attention to systemic or institutional contributors to environmental damage reveals an underlying ideological bias in the textbooks. This perspective aligns with what scholars describe as neoliberal environmentalism (Pratolo et al. 2024). This viewpoint foregrounds individual responsibility, that is, an approach that places the responsibility for environmental protection mainly on individuals rather than on larger actors such as governments or corporations (Baatz 2014; Kent 2009; Placani 2024). Although encouraging personal action is important, presenting it without reference to broader structural issues such as industrial emissions can lead to an oversimplified understanding of the problem. This narrow framing may normalize existing power structures and shift attention away from the need for collective and policy-based solutions. Consequently, the textbooks at times promote an ambivalent ecosophy. In this context, the textbooks support environmentally positive behavior. However, they fail to fully acknowledge the broader social, political, and economic dimensions of environmental responsibility.

In some instances, this ambivalence continues to shape the representation of environmental issues, particularly when problems such as pollution or degradation are shown without the presence of social actors or any proposed solutions. The repeated absence of human figures in these scenes tends to portray environmental damage as natural, unavoidable, or outside human influence. The absence of clear human action in these texts can cause students to feel powerless or less interested especially when they are expected to take part in solving environmental problems in the future. According to Stibbe (2004), such representations contribute to shallow environmentalism. They often show the effects but do not explain the deeper causes, such as human choices, economic systems, or political decisions. As a result, although the textbooks aim to promote care for the environment, their inconsistent and often passive portrayals show an underlying anthropocentric ideology that prioritizes human needs and comforts over the health of nature (Cavallaro 2024). This limits the impact of environmental education and may make it harder for students to understand and respond to the main causes of environmental problems.

In general, the portrayal of environmental problems in the Indonesian EFL textbooks could be interpreted as ambivalent. These visual representation choices bring a dual message regarding human interaction with the environment. While they draw attention to environmental problems, they often fail to present clear narratives or solutions for sustainable action. This ambivalence can be beneficial since the representations help raise students’ awareness of environmental problems. However, it can also be destructive because it conveys the message that pollution and environmental neglect are inevitable parts of modern life. Without deeper contextualization or empowering narratives, these portrayals may present ecological issues as fixed rather than solvable. Thus, the overall message in these representations remains unclear. Although the texts offer useful information, they often appear passive, as they do not explicitly support or critically engage with efforts to promote strong environmental awareness.

6 Conclusions

This study examined how eco-awareness is portrayed in Indonesian EFL textbooks through the representation of social actors, actions, and settings. The analysis shows that to some extent the textbooks promote beneficial discourses. Social actors are often included and shown engaging in environmentally responsible behaviors either as individuals or as groups. These actors are framed both visually and linguistically in ways that encourage readers to relate to them and emphasize personal and shared responsibility for protecting the environment. Through this way, the textbooks aim to raise awareness and encourage students to adopt positive attitudes toward the environment.

However, the beneficial discourses are not always consistent. In several cases, social actors are excluded from images and texts especially in scenes showing pollution or waste. Visually, this exclusion appears through conversion where human presence is removed or implied without being shown. In the written texts, nominalization is used to hide who is responsible. Similarly, some contextualized settings are taken from oblique angles which create emotional and moral distance by positioning viewers as passive observers. Decontextualized settings present the environmental care as an abstract concept and further distance the viewer from active participation. As a result, some representations reflect ambivalent discourses in which environmental problems are shown as detached from human action. In more concerning cases, the complete absence of people and solutions may suggest that these problems are inevitable and risk promoting ecological indifference or fatalism among students.

These findings show that textbooks need to be designed more thoughtfully and effectively. In their current representations, Indonesian EFL textbooks often focus on individuals and overlook the larger systems that cause environmental problems. At times they obscure human agency altogether. To enhance their educational value, textbooks should offer a more holistic and realistic view of environmental issues. This can be achieved by showing both individual and collective actors. Moreover, textbook designers should make human involvement visible and balance examples of everyday behavior with references to institutional responsibilities and policy-level solutions. Both text and images should avoid being overly passive or abstract. Instead, they should use activated modes, show agencies, and include specific examples of environmental practices. Textbook designers need to improve how images and texts work together to communicate environmental messages. Visuals should not simply decorate the page but should be meaningfully connected to the written content. This can be achieved by providing relevant captions and labels that encourage students to engage critically with both the image and the text.

To ensure these textbook revisions are effective in practice, teacher training programs should support educators in building the skills needed to promote eco-literacy in the classroom. Since the textbooks often hide who is responsible or present environmental issues in unclear ways, teachers play an important role in helping students understand how both texts and images create meaning. This includes guiding them to question whose voices are included or excluded and how responsibility is assigned or hidden. Classroom activities such as critical reading, image analysis, and projects based on real environmental issues can help students think more deeply and challenge the passive or unclear messages in the textbooks. By using these strategies, teachers can create learning environments where students not only learn about the environment but also become more aware and motivated to take meaningful action.

Future research could investigate whether similar representational patterns appear in EFL textbooks from different educational or cultural contexts so that it provides a broader understanding of how environmental issues are presented around the world. Additionally, future studies could also examine how students understand and react to the visual and written messages in these textbooks. This would show how much these materials influence students’ environmental attitudes and behaviors. By focusing on messages that are inclusive and action-oriented, language learning resources can better promote ecological literacy and encourage students to take meaningful action on real environmental challenges.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest appreciation to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions and constructive feedback.

-

Data availability: The figures presented in this article are sourced from Indonesia government-issued textbooks that are publicly available and free to use. As stated on their official website (https://app.buku.kemdikbud.go.id/), Sistem Informasi Perbukuan Indonesia confirms that these materials are accessible to the public and may be used, reproduced, and distributed without restriction.

Appendix: Textbooks under investigation

Afrilyasanti, Rida. 2021. Bahasa Inggris: Tingkat lanjut untuk SMA kelas XI [English: Advanced level for senior high school grade XI]. Jakarta: Pusat Perbukuan, Badan Standar, Kurikulum, dan Asesmen Pendidikan, Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset, dan Teknologi.

Astuti, Puji, Aria S. Anggaira, Atti Herawati, Yeyet Nurhayati, Dadan & Dayang Suriani. 2022. Bahasa Inggris: English for change untuk SMA/MA kelas XI [English: English for change for senior high school/Islamic senior high school grade XI]. Jakarta: Pusat Perbukuan, Badan Standar, Kurikulum, dan Asesmen Pendidikan, Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset, dan Teknologi.

Hardini, Susanti R., Achdi Merdianto, Marjenny, Rani Nurhayati, Isry L. Syathroh & Dadan. 2022. Bahasa Inggris: Life today untuk SMA/MA kelas XII [English: Life today for senior high school/Islamic senior high school grade XII]. Jakarta: Pusat Perbukuan, Badan Standar, Kurikulum, dan Asesmen Pendidikan, Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset, dan Teknologi.

Hermawan, Budi, Dwi Haryanti & Nining Suryaningsih. 2022. Bahasa Inggris: Work in progress untuk SMA/SMK/MA kelas X [English: Work in progress for senior high school/vocational high school/Islamic senior high school grade X]. Jakarta: Pusat Perbukuan, Badan Standar, Kurikulum, dan Asesmen Pendidikan, Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset, dan Teknologi.