Abstract

This study aims to examine the linguistic features, emotional self-disclosure, and thematic patterns of the online self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression in China. First, the study findings indicate several key linguistic characteristics in the online self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression in China. Specifically, regarding the use of personal pronouns, the highest frequency is observed for the singular first-person pronoun “I”, which demonstrates the self-focused narrative mode prevalent in Chinese online depression discourse. Notably, the use of third-person pronouns constructs a state of isolation in terms of both external identity and internal emotions, further highlighting the confrontational nature of the discourse. Besides, in terms of lexical usage features, the online self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression in China can be categorized into three main types: (i) frequent use of disease-related vocabulary, (ii) frequent use of negative terms like as “no” or “not”, and (iii) frequent use of emotional words. Second, regarding emotional self-disclosure, the use of negative emotional words significantly outweighs the use of positive ones, resulting in an overall dominance of negative sentiment. Additionally, the emotional orientation of the semantic content should be interpreted in the specific contextual meaning. Third, as for topic characteristics, the online self-disclosure on social media reveals five key topics: emotional representation, emotional challenges, life status, pathological manifestations, and emotional needs. In light of these findings, this study aims to enrich the research on emotional health discourse to some extent and provide a comprehensive perspective to enhance social understanding of individuals with depression, with the hope of contributing to the improvement of overall mental health in society.

1 Introduction

With the burgeoning awareness of mental health issues, depression has emerged as a significant public health challenge globally, exerting a profound impact on the quality of life and mental well-being of affected individuals. The disorder not only amplifies the global burden of disease but also inflicts profound distress on the families of those affected (Herrman et al. 2019). However, mainstream media portrayals of individuals with depression tend to be oversimplified, reinforcing stigmatization and neglecting the complexities of their lived experiences (Hu 2023). As the prevalence of depression continues to rise worldwide, addressing this issue has transcended the realm of healthcare to become a critical social concern. In this context, social media serves as an indispensable communication tool in modern society, providing a new platform for those with depression to express emotions and seek assistance (Brookes and Harvey 2016; Yan and Liu 2022). With the advent of the internet era, online communities such as “超话” (chaohua, ‘super topics’) on “微博” (Weibo, ‘Microblog’), “豆瓣小组” (Douban Xiaozu, ‘Douban Groups’), “知乎” (Zhihu, ‘Do you know’), and “百度贴吧” (Baidu Tieba, ‘Baidu Post Bar’) have gradually emerged as significant spaces for health-related discourse. These virtual spaces not only serve as crucial platforms for self-presentation and communication among individuals with depression but also provides new perspectives for academic research. As Huang and Zhou (2021) stated, emerging studies based on social media data can mitigate some limitations found in traditional depression research methodologies, further validating existing findings and yielding novel insights. Furthermore, due to its large and diverse user base, high anonymity, and rich, sustained depression-related discussions facilitated by intelligent topic recommendation, the “depression super topics” community on Microblog offers an ideal platform for analyzing the self-disclosure behaviors and emotional expressions of individuals with depression.

Accordingly, the present study delves to systematically analyze online discourse within “depression super topics” on Microblog by employing natural language processing (NLP) tools and sentiment lexicon analysis. Specifically, this research explores the linguistic features, emotional self-disclosure and topic characteristics in the online self-disclosure among individuals with depression in China. By providing a comprehensive depiction of depression-related online discourse, this study aims to enhance social understanding of the depression community while offering linguistic support to foster the well-being and social integration of vulnerable groups.

2 Literature review

2.1 Multidisciplinary studies on depression discourse

Depression, as a global mental health issue, has attracted widespread academic attention both domestically and internationally. With increasing mental health awareness and the proliferation of social media, research on depression discourse has gradually expanded beyond traditional fields such as psychology and sociology to include computational science, communication studies, and linguistics.

First, in the field of psychology, depression discourse research is closely linked to mental health studies. The language used by individuals with depression is often regarded as a critical reflection of their psychological state. Studies have shown that individuals with depression tend to use first-person singular pronouns and negative emotion words more frequently, indicating heightened self-focus and negative affectivity. Additionally, distinct linguistic patterns have been observed among different psychological disorders (Lyons et al. 2018). Besides, in recent years, research on depression has shifted from a traditional realist perspective to a constructivist paradigm, focusing on how depression is discursively constructed. For example, Dixon (2016) highlighted that from a constructivist perspective, the concepts of depression and recovery evolve over time and across sociocultural contexts, demonstrating that depression and recovery are socially constructed. Dixon’s research found that adolescents employ four major discourse patterns to conceptualize depression and recovery, revealing the disempowerment experienced by young people in their depression narratives.

Second, with increasing social mobility and societal change, the issue of social support for individuals with depression has become a significant topic in sociology. Research in this field ranges from macro-level social support mechanisms to micro-level discourse characteristics, deepening the understanding of depression from multiple perspectives. For instance, Johnson et al. (2012) explored how men with depression navigate help-seeking behaviors. The study found that men’s help-seeking decisions were influenced by five discourse frameworks, including self-reliance, responsible action in seeking treatment, cautious vulnerability, despair, and genuine connection. This research contributes to a broader discussion on gender discourse, help-seeking narratives, and depression discourse, providing valuable insights into the intersection of masculinity and mental health.

Third, the field of computational science focuses on using technological methods to analyze discourse for the identification and prediction of depression. For instance, Dao et al. (2014) analyzed posts from online depression communities using machine learning methods, finding that users’ emotional states, age, and social connectivity significantly influenced their linguistic style and discussion topics. The study successfully differentiated between high and low depressive mood users based on their discourse patterns. These findings demonstrate that computational methods effectively capture depression-related discourse features, offering important insights for depression screening and intervention.

Fourth, communication studies primarily examine how depression is constructed in public discourse. Traditional research has focused on media representation of depression. For example, Fan (2022) analyzed linguistic patterns in media discourse on depression, while Zhang (2022) explored how individuals with depression are portrayed in the media. With the rise of social media, research has shifted towards analyzing the online discourse ecology of depression communities (Thompson and Furman 2018).

Fifth, linguistic research focuses on a multidimensional analysis of depression discourse from a linguistic perspective. For instance, according to Reali et al. (2016) depression is frequently metaphorically constructed as a spatial entity or an adversarial opponent. These linguistic frameworks not only shape public understanding of depression but also influence societal attitudes toward individuals with depression. Besides, some studies examine how self-disclosure functions as a social action within online self-help groups for anxiety and depression (Yip 2024).

In conclusion, existing multidisciplinary research on depression discourse, spanning psychology, sociology, computational science, communication studies, and linguistics, has provided insights into its broader characteristics. Notably, a growing body of literature reveals a clear shift from traditional domains to the online context (Koteyko and Hunt 2018; Sharma and Sirts 2024; Valiakalayil 2015), with increasing academic attention directed toward self-disclosure as a central communicative practice, particularly in online depression communities.

2.2 Self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression on social media

With the widespread use of social media, self-disclosure among individuals with depression in online platforms has become a focal point of research. Self-disclosure not only serves as a crucial means for individuals with depression to express emotions and share experiences but also provides them with channels for emotional support and social connection. Studies have shown that self-disclosure discourse among individuals with depression exhibits distinct linguistic features, emotional expression patterns, and social support functions, offering valuable insights into understanding their psychological states, identifying language patterns, and designing personalized intervention strategies.

First, self-disclosure is an essential means for individuals with depression to express their emotions and experiences, with research indicating that their discourse exhibits a strong individualized and emotion-oriented linguistic style. There are notable differences in language use between individuals with depression and the general population. For example, Huang and Zhou (2021) found that individuals with depression tend to use first-person singular pronouns and negative emotion words more frequently, while using first-person plural pronouns and positive emotion words less frequently. Besides, social media discourse has become an important resource for understanding and detecting mental health issues. For instance, Rosario (2023) examined self-disclosure discourse on Reddit among users who self-identified as having depression, revealing age-specific linguistic patterns. Their study found significant differences between adolescents and adults in their expressions of depression, particularly in terms of social concerns, temporal focus, emotions, and cognition. These findings highlight the potential role of self-disclosure discourse in precise classification and personalized interventions for different age groups.

Second, in the social media environment, self-disclosure among individuals with depression involves not only linguistic patterns but also distinctive emotional expression styles. Research suggests that individuals with depression tend to display higher emotional intensity in self-disclosure and favor the use of negative emotion words (Huang and Zhou 2021). However, some studies indicate that self-disclosure can influence mental well-being positively. By allowing individuals to express negative emotions, self-disclosure can alleviate depressive moods and improve psychological health, making it a valuable therapeutic tool. Sharing personal experiences with others can also enhance psychological resilience (Shi and Khoo 2023).

Third, social media offers individuals with depression a relatively safe space where they can freely express their emotions and receive emotional support from the community. Previous studies have emphasized that self-disclosure plays a key role in reducing loneliness, thereby alleviating symptoms associated with mental health issues. It is widely recognized as a common social practice within online support groups, fostering relationship-building through participant interaction (Yip 2024). For example, Shi and Khoo (2023) analyzed self-disclosure behaviors within online health communities, finding that self-disclosure is significantly correlated with social network structures. Frequent self-disclosure was shown to help individuals establish stable social connections and receive increased interaction and support. Similarly, Zhu (2011) highlighted that self-disclosure is a prevalent communicative practice in online support groups and is characterized by high intimacy. Messages containing self-disclosure were more likely to receive social support than those without self-disclosure. This study underscores self-disclosure as a continuous and interactive process, playing a dual role in enhancing social support exchange and influencing the psychological adjustment of individuals with depression.

In conclusion, research on self-disclosure discourse among individuals with depression has identified distinctive patterns in linguistic features, emotional disclosure, and social support functions. These studies have not only advanced the understanding of self-disclosure behaviors in individuals with depression but have also provided critical insights for early detection, personalized intervention, and the development of effective social support mechanisms.

Despite these significant advancements, several research gaps remain. First, existing studies predominantly focus on Western contexts, with limited attention to self-disclosure discourse among individuals with depression in China, particularly in the context of Chinese social media platforms. Second, research on the emotional and thematic dimensions of online self-disclosure remains relatively underexplored, particularly in terms of the finer-grained categorization of emotions and the detailed distribution of thematic content. Third, previous studies have primarily adopted single-method approaches, lacking a comprehensive and integrative examination of linguistic features, emotional disclosure and topic characteristics.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research questions

To bridge these gaps, this study seeks to address the following three questions:

What are the linguistic features of online self-disclosure among individuals with depression in China?

What is the emotional disclosure of individuals with depression in China?

What topics are disclosed by individuals with depression in China?

3.2 Data collection

This paper selects user posts from the “抑郁症超话” (yiyuzheng chaohua, ‘depression super topics’) community on Microblog for discourse analysis, as its broad user base, high engagement, and weak social ties enable more diverse and authentic self-disclosure among individuals with depression. Additionally, Microblog’s digital traces are more accessible and suitable for large-scale analysis, making it an ideal platform for studying depression-related discourse. To ensure the representativeness of the data, this study employed stratified sampling and data cleaning to construct the final corpus. First, we randomly collected 1,000 posts from the “depression super topics” community on Microblog, covering a one-month period from June 2024 to July 2024. Subsequently, we conducted random sampling to extract 700 posts, which not only ensured an adequate overall sample size for the study but also facilitated the unbiased selection of user discourse. Based on this data, we performed data cleaning, removing irrelevant posts such as advertisements and automatically generated content, eliminating duplicate entries, filtering out excessively short texts (fewer than five characters), and discarding meaningless symbols. Ultimately, after screening and optimization, we retained 593 high-quality posts, ensuring that the overall text length was appropriate and thematically relevant to support further analytical procedures.

3.3 Research framework

Fairclough (2013) proposed a three-dimensional framework, comprising text, discursive practice, and social practice, to analyze discourse from both micro and macro levels. This study focuses on the textual dimension of Fairclough’s framework to examine the characteristics of self-disclosure discourse among individuals with depression in Chinese online communities. Specifically, this study employs text analysis methods (Fairclough 2003), including word frequency analysis, sentiment lexicon analysis, and topic modeling. By utilizing these analytical approaches, the study aims to systematically identify the linguistic features, emotional self-disclosure, and topic characteristics in the self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression. Notably, linguistic features and emotional disclosure are clearly distinguished in this study based on their differing analytical objectives. First, linguistic features, including pronoun usage and lexical usage, are examined as surface-level textual characteristics. In contrast, emotional disclosure focuses on the emotional orientation and expressive functions conveyed through discourse, utilizing sentiment lexicon analysis as a methodological tool. In this context, emotional vocabulary is not the primary object of analysis but rather serves as a technical means of identifying emotional expression.

3.3.1 Data preprocessing

Initially, we import and process the collected corpus using “Pandas” in Python. To ensure the accuracy of the data, basic cleaning tasks are conducted, including the removal of unnecessary symbols, spaces, and other special characters that might affect the analysis. Given that the comments are expressed in Chinese, we utilize “Jieba” (Chinese text segmentation: built to be the best Python Chinese word segmentation module) to remove irrelevant punctuation and whitespace information. This step is crucial for accurately conducting the corpus analysis in this study.

3.3.2 Word frequency analysis

Word frequency analysis is a content analysis method used to identify the focus and key words in a text (Mao et al. 2023). First, in terms of linguistic features, this study primarily employs word frequency analysis. Specifically, regarding the usage patterns of personal pronouns, we use Python’s Pandas library in combination with Excel tools to conduct the analysis and tabulation. Initially, we load the data into a DataFrame using “read_excel” function from the provided Excel file, facilitating subsequent data processing and analysis. Next, we define a list of eight Chinese personal pronouns (“I”, “We”, “You”, “He”, “She”, “It”, “They”) and tally the occurrence of each pronoun in each statement within the “Statement Content” column of the DataFrame. enabling efficient data processing. To examine lexical usage, we also conducted word frequency analysis on the study corpus, with the results visualized as a word cloud generated in Python.

3.3.3 Sentiment analysis

Sentiment analysis involves the extraction of subjective information from text using techniques such as text mining. Currently, there are two primary methods for conducting sentiment analysis: one is based on sentiment lexicon, and the other employs machine learning techniques (Peng et al. 2024). The lexicon-based sentiment classification approach utilizes well-established sentiment dictionaries to calculate the emotional value of sentiment words found in the text, which then determines the overall sentiment polarity of the text through weighted calculations (Wang et al. 2022). This study employs the Affective Lexicon Ontology (Xu et al. 2008) developed by Dalian University of Technology. However, recognizing the limitations of this approach, which include an over-reliance on the construction of sentiment dictionaries and the inability to consider context and situational nuances, this research aims to optimize by integrating Python and Gephi software to visualize the co-occurrence network of prominent sentiment word frequencies, thereby further verifying the accuracy of the results.

3.3.4 Topic analysis: based on LDA model

Topic modeling, particularly the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model, is widely used in text data mining to uncover latent semantic relationships between documents and words (Ding and Wu 2023). The LDA model treats documents as a mixture of topics, where each topic is a probability distribution of words, enabling efficient text information processing. In this study, the LDA model is employed to analyze the implicit semantic structures of online self-disclosure discourse among depression patients on microblog. The model identifies the distribution probabilities of topics within documents and terms within topics (Fan and Liu 2023), grouping related terms to represent corresponding themes (Chen et al. 2022).

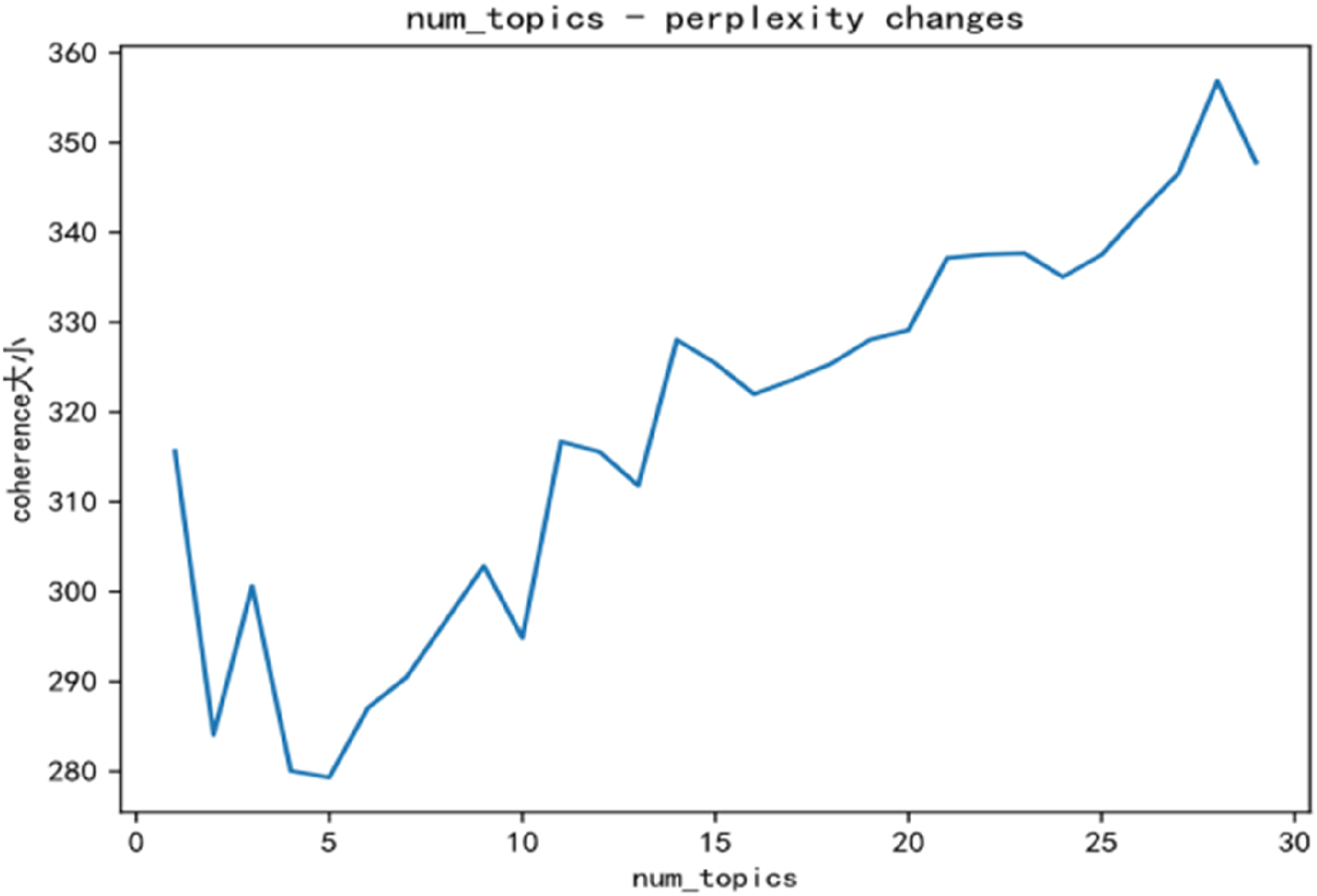

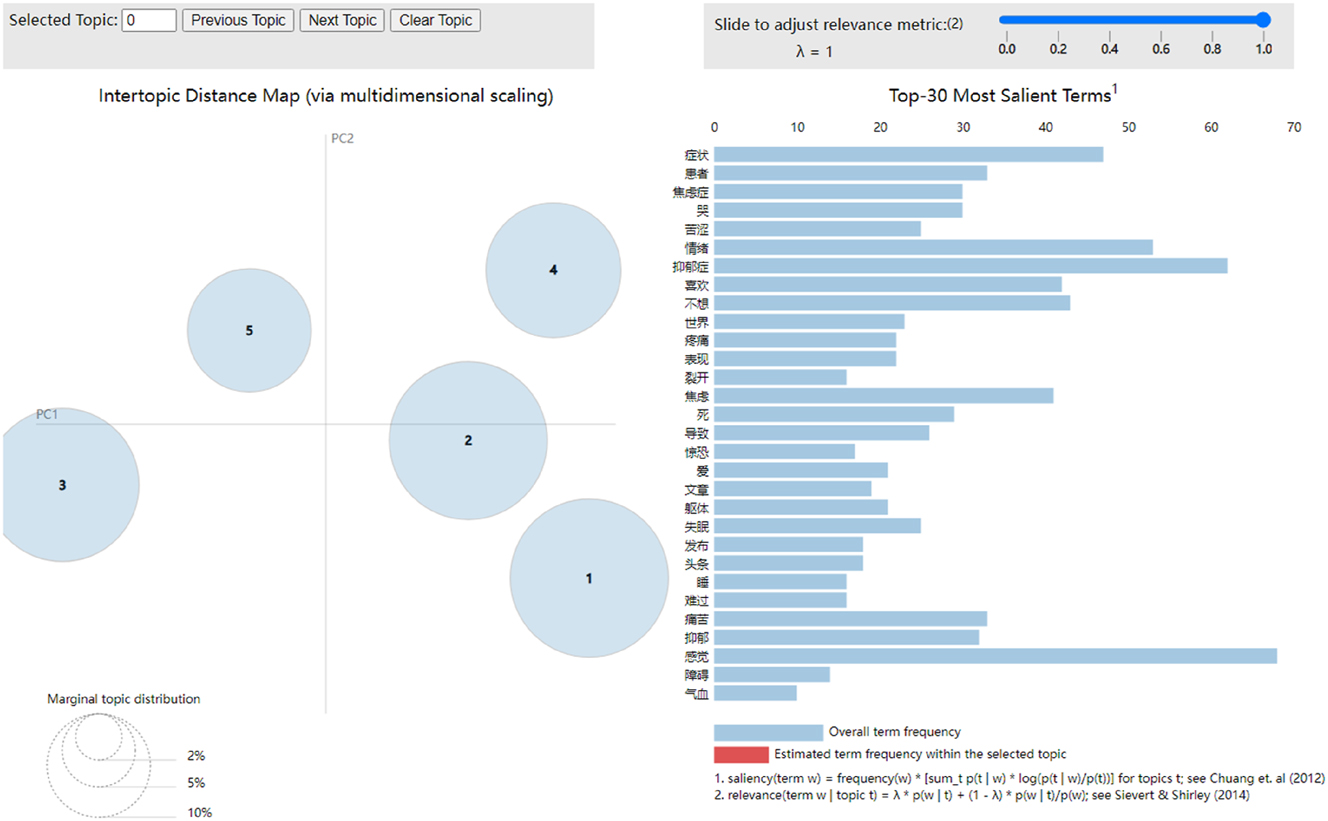

The LDA model requires the determination of the optimal number of topics, K, to ensure effective topic extraction (Ding and Wu 2023). In this study, perplexity is calculated to determine the optimal number of topics, with lower perplexity indicating better clustering performance. As shown in Figure 1, when the number of topics is set to 5, the perplexity of the topics mined by the LDA reaches a local minimum, indicating optimal clustering results at this topic number.

Confusion degree change of topics.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Linguistic features

4.1.1 Pronoun usage characteristics

This section aims to conduct a detailed analysis of personal pronouns used in the online discourse of individuals with depression on social media. Specifically, it aims to analyze the frequency of first-person, second-person, and third-person pronouns (see Table 1) in the corpus to examine the degree of self-focus (see Figure 2) in the context of Chinese online self-disclosure among individuals with depression. By exploring the patterns of personal pronoun usage in these self-disclosures, this study seeks to uncover how such linguistic choices reflect the psychological states of individuals with depression and shape their interpersonal interactions in online communication.

Usage of personal pronouns.

| Category | Singular | Frequency (Singular) | Plural | Frequency (Plural) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First person | I | 1,207 | We | 35 | 1,242 |

| Second person | You | 199 | You | 16 | 215 |

| Third person | He/she/it | 282 (141/120/21) | They | 38 | 320 |

| Total | – | 1,688 | – | 89 | 1,777 |

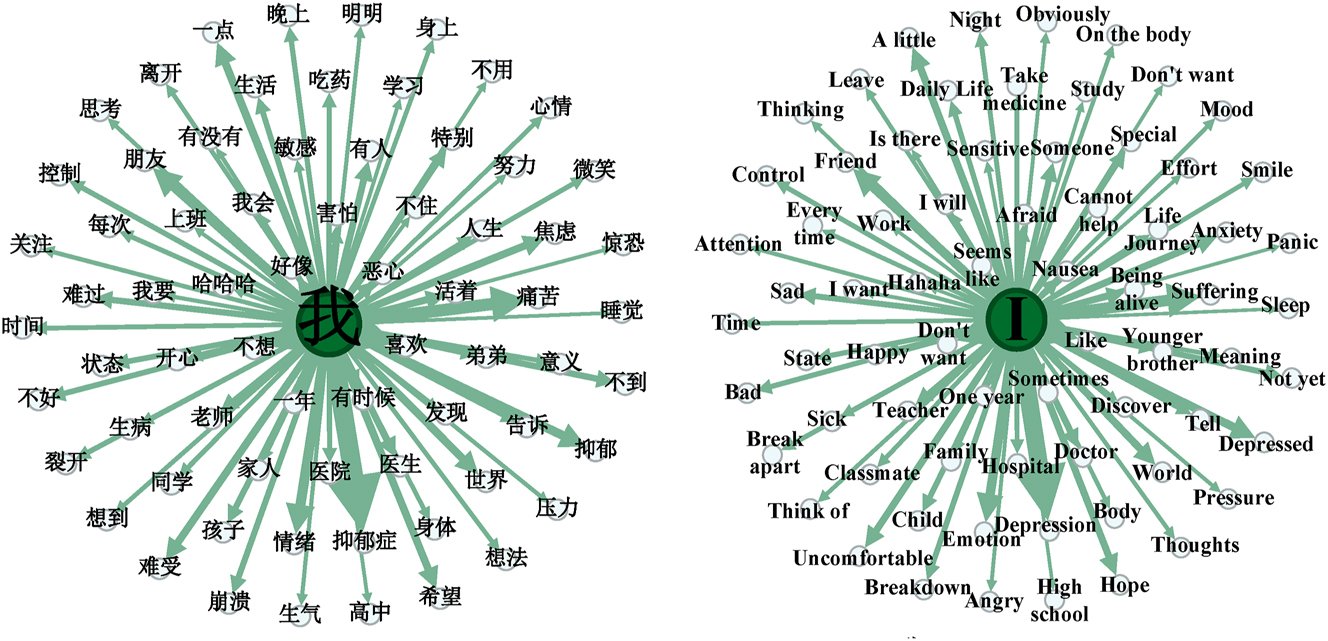

Online self-disclosure discourses related to “我” (wo, ‘I’) by individuals with depression.

The results from Table 1 demonstrate the usage patterns of personal pronouns in the online self-disclosure of individuals with depression. First, the most frequently used pronouns are first-person pronouns, with a frequency of 1242, among which the first-person singular “I” registers the highest frequency across all categories (Huang and Zhou 2021); this is followed by third-person pronouns with a frequency of 320, and second-person pronouns with a frequency of 215. This indicates that the online self-disclosure discourse of those with depression in China on social media also tends to be highly self-focused (Ding and Wu 2023), which will be analyzed in detail in the following sections (see Figure 2). Notably, as an affective positioning resource (Giaxoglou 2015), the use of third-person pronouns in Chinese online depression discourse constructs a state of isolation in terms of external identity and internal emotions. Furthermore, third-person pronouns serve to reinforce a confrontational context, where individuals describe their emotional experiences from an external perspective while simultaneously linking negative evaluations to the discourse of others, thereby creating a tension and conflict between self-position and external discursive frameworks.

| 他们骂我, 如果我生气他们就会说我敏感, 如果我说我不敏感, 他们就会搬出谁谁谁, 某个亲戚或熟人, 也说过我敏感, 给我举一些例子, 这里的敏感可以替换成别的词。他们在平时会无意透露某个人人品很差, 不喜欢他, 等到吵架的时候, 他们就会说, 你就像XXX, 你连XXX都不如。[They criticize me, and if I get angry, they say I’m being too sensitive. If I say I’m not sensitive, they bring up someone, like a relative or acquaintance, who also mentioned that I’m sensitive, and give me examples. “Sensitive” could be replaced with other terms. In daily interactions, they may casually reveal that someone has a bad character or that they dislike him. When a quarrel breaks out, however, they will say things like, “You’re just like XXX,” or “You’re even worse than XXX.”] |

In Example (1), the speaker uses the third-person plural “他们” (tamen, ‘they’) to describe their relationship and communication with their parents. This usage linguistically constructs a clear identity opposition and reflects significant social and emotional distance between the speaker and their parents. Initially, by categorizing the parents as “他们” (tamen, ‘they’) the speaker not only emphasizes a physical separation but also expresses an opposition and estrangement on a psychological and emotional level (Hu 2023). Moreover, attributing the emotional conflicts between “我” (wo, ‘I’) and parents to an external“他们” (tamen, ‘they’) is a strategy of externalization employed by the speaker, demonstrating a mechanism of self-protection. The interaction described by the speaker is filled with accusations and criticisms, such as the parents unfavorably comparing the patient to others and labeling them as “敏感” (mingan, ‘sensitive’). In describing the actions and words of the parents, the speaker uses the third person to maintain a certain degree of objectivity and distance (Liu and Li 2012), thus helping the patient to emotionally delineate boundaries. Through this approach, the speaker not only protects themselves from direct harm but also attempts to voice their complaints within the online community (Zhang and Shuai 2023), seeking empathy and support.

Second, the use of singular pronouns (frequency: 1688) significantly surpasses that of plural pronouns (frequency: 89) in the online self-disclosure language of individuals with depression. This indicates that self-disclosure on social media by those with depression is often more personalized (Sun 2023). The frequent use of singular pronouns may be related to their expression of personal emotions and requests for help, while the less frequent use of plural pronouns (e.g. “我们”, ‘we’ frequency: 35) suggests that building interactions and resonances with others on social media is relatively limited. Specifically, the first-person singular “我” (‘I’) (frequency: 1207) is the most frequently used, which re-emphasizes the self-focused nature of the language used by those with depression in articulating their feelings and experiences (Ding and Wu 2023) and the introspective monologue style of their speech.

| 我最近很不好, 我生病了, 我得了抑郁症, 我不知道为什么生病的是我, 我好痛苦。我今年没有参加高考, 因为我生病了, 昨天晚上我吞了三十颗安乐片, 喝了一点农药, 我不知道为什么我这么痛苦, 医生一直劝我, 告诉我我的人生才刚刚开始, 可是我已经不想开始了。我该怎么办。[I haven’t been doing well lately. I’m sick. I have been diagnosed with depression, and I don’t understand why it had to be me. I am in so much pain. I didn’t take the college entrance exam this year because of my illness. Last night, I swallowed thirty sleeping pills and drank some pesticide. I don’t know why I am suffering so much. The doctor keeps trying to persuade me, telling me that my life has just begun, but I no longer want to begin it. What should I do?] |

In Example (2), the individual with depression emphasizes his or her personal experiences and emotional state by consistently using the first-person singular “我” (‘I’), as seen in statements such as “我生病了” (wo shengbing le, ‘I’m sick’), “我得了抑郁症” (wo dele yiyuzhheng, ‘I have been diagnosed with depression’) and “我好痛苦” (wo hao tongku, ‘I am in so much pain’). Such expression not only demonstrates how the individual connects life’s setbacks and personal illness to form a negative life narrative, but it also reflects the personalized and introspective monologue style of language used in self-disclosures on social media. This is a primary linguistic characteristic of how this group presents themselves online.

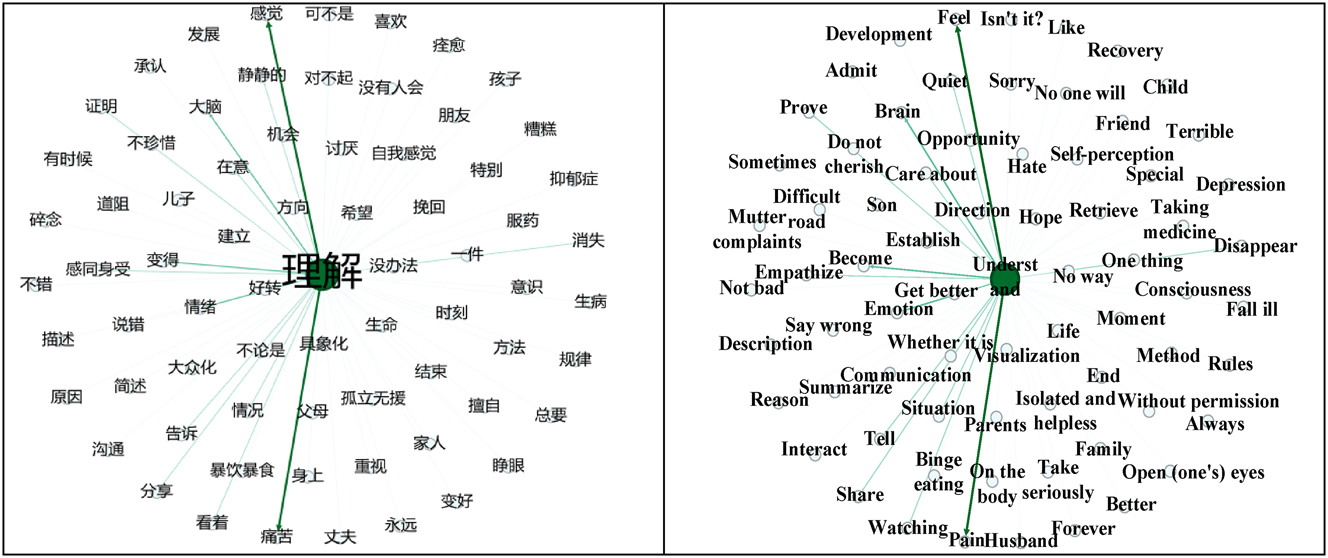

To further explore the self-focused content in the Chinese online self-disclosure of individuals with depression, this study conducted a semantic network analysis on the corpus of utterances related to the pronoun “我” (wo, ‘I’). We selected “我” (wo, ‘I’) as the keyword, filtering out 303 relevant comments, and retained texts longer than two words and ranked within the top 70 by significance. The cleaned data was then visualized using Gephi to create a semantic network diagram (see Figure 2). Semantic network analysis allows for the assessment of co-occurrence relationships between words, where the density of the lines indicates the closeness of the relationships, and the denser the lines, the stronger the association between the words (Lin and Meng 2020). As demonstrated in Figure 2, the following three conclusions can be drawn.

First, the online self-disclosure utterances about “我” (wo, ‘I’) among individuals with depression demonstrate their self-focus on emotional states. The central term “我” (wo, ‘I’) is closely linked with various words related to emotions and psychological states, revealing the emotional self-focus in the online discourse of those with depression on social media. Specifically, the links between “我” (‘I’) and terms like “情绪” (xingxu, ‘emotion’), “痛苦” (tongku, ‘pain’), “焦虑” (jiaolv, ‘anxiety’), “害怕” (haipa, ‘afraid’), “难受” (nanshou, ‘discomfort’), and “崩溃” (bengkui, ‘collapse’) highlight the core emotions frequently expressed by those with depression. The dense connectivity of these emotional words illustrates how often individuals discuss their negative feelings on social media platforms (Fan and Liu 2023; Vedula and Parthasarathy 2017).

Second, the co-occurrence network vividly illustrates the focus of individuals with depression on their own life states on social media. The central word “我” (wo, ‘I’) is closely linked with multiple terms related to everyday life, such as “抑郁症” (yiyuzheng, ‘depression’), “世界” (shijie, ‘world’), “活着” (huozhe, ‘living’), “意义” (yiyi, ‘meaning’), “睡觉” (shuijiao, ‘sleeping’), “生病” (shengbing, ‘sickness’), and “状态” (zhuangtai, ‘state’). The frequent appearance of these words reveals the patients’ focus on their own health status, physiological conditions, and daily challenges, and even extends to broader existential questions, such as worldviews and the meaning of life (Ding and Wu 2023).

Third, a range of terms associated with “我” (wo, ‘I’) such as “朋友” (pengyou, ‘friends’), “家人” (jiaren, ‘family’), “老师” (laoshi, ‘teachers’), and “同学” (tongxue, ‘classmates’) prominently reflect the focus of individuals with depression on their interpersonal relationships on social media. Through social media, patients share their personal interpersonal experiences from real life, primarily disclosing challenges they face such as social pressures and feeling marginalized within their social circles (Lian 2020). This also highlights their deep need for understanding and acceptance.

In summary, regarding the use of personal pronouns, the self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression predominantly employs first-person pronouns, followed by third-person pronouns and second-person pronouns. Pronouns serve as tools for online self-disclosure practices and emotional regulation, achieving effects of emotional immersion and detachment, thus reflecting the strategic use of language by the speaker. Moreover, the discourse of individuals with depression online primarily exhibits a self-focused narrative pattern (Ding and Wu 2023), characterized by a focus on one’s own emotions, life circumstances, and interpersonal relationships.

4.1.2 Lexical usage characteristics

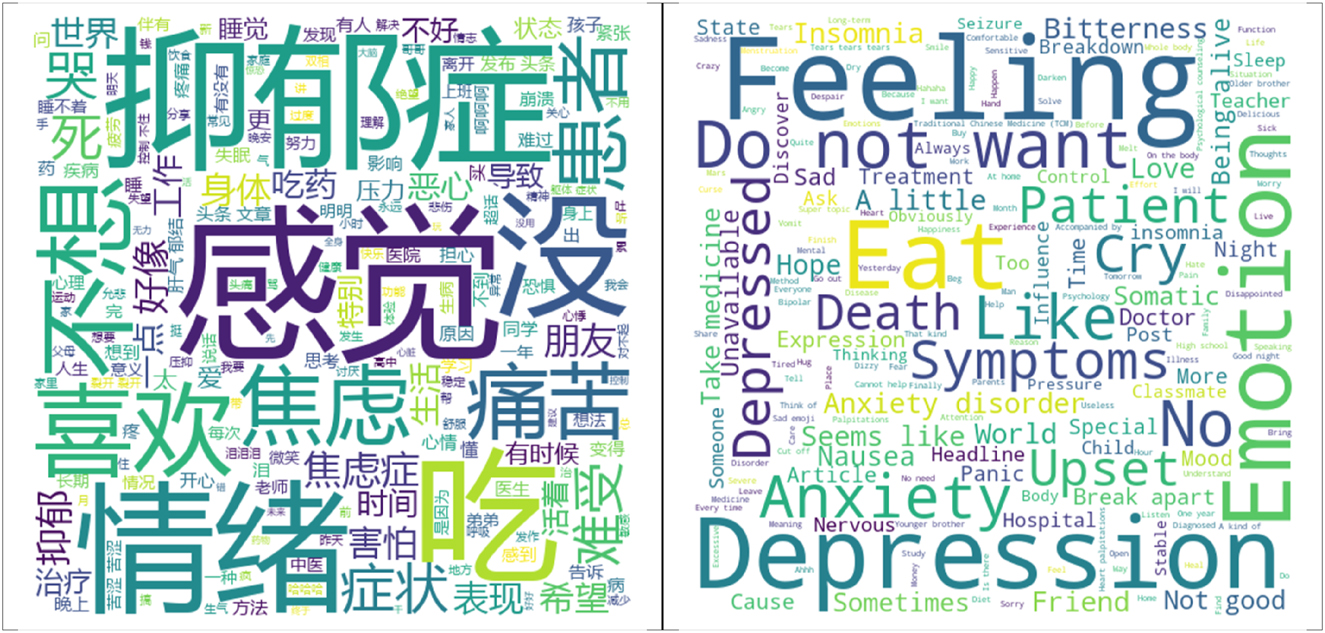

To visually understand the vocabulary features of depression patients’ online discourse on the microblog platform, this study conducted word frequency statistics on the selected corpus and used Wordcloud in Python to generate a high-frequency word cloud (see Figure 3). Figure 3 displays the common vocabulary in the online discourse of the depression community, with larger fonts indicating higher frequency of use of the corresponding words.

Word cloud of online discourse from the “depression super topics”.

Based on Figure 3, the most frequently occurring words include “感觉” (ganjue, ‘feeling’), “抑郁症” (yiyu, ‘depression’), “情绪” (qingxu, ‘emotion’), “症状” (zhengzhuang, ‘symptoms’), “不想” (buxiang, ‘don’t want’), “焦虑” (jiaolv, ‘anxiety’), “喜欢” (xihuan, ‘like’), “患者” (huanzhe, ‘patient’), “痛苦” (tongku, ‘pain’), “抑郁” (yiyu, ‘depressed’), and “难受” (nanshou, ‘discomfort’). Therefore, the linguistic features of the online discourse of individuals with depression on social media can be categorized into three main aspects: i) frequent use of disease-related vocabulary; ii) frequent use of negative expressions; iii) frequent use of emotional vocabulary.

First, individuals with depression frequently use disease-related vocabulary on social media, such as “抑郁症” (yiyuzheng, ‘depression’), “症状” (zhengzhuang, ‘symptoms’), “患者” (huanzhe, ‘patient’) and “抑郁” (yiyu, ‘depressed’). The high frequency of these words indicates their focus and awareness of their own health conditions. Additionally, through these words, patients not only describe their pathological states but also seek relational connections and identity affirmation within the online community (Hu 2023).

Second, the frequent use of negative terms like “不”(‘no’ or ‘not’) is another significant characteristic of the online self-disclosure language of individuals with depression, often linked to their negative thinking patterns and sense of uncertainty (Yan and Liu 2022). The use of these words typically reflects the patients’ uncertainty about the future, dissatisfaction with their current conditions, or an escapist attitude.

Third, another noteworthy linguistic feature is the frequent use of emotional vocabulary. Emotional words such as “情绪” (qingxu, ‘emotion’), “焦虑” (jiaolv, ‘anxiety’), “喜欢” (xihuan, ‘like’), “痛苦” (tongku, ‘pain’) and “难受” (nanshou, ‘discomfort’) reflect the emotional fluctuations and psychological states expressed in the online self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression (Huang and Zhou 2021).

4.2 Emotional self-disclosure

Emotions are central to the self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression, shaping their linguistic expressions and interactions online. This section examines sentiment polarity, specific emotional categories, and semantic co-occurrence patterns to provide a structured analysis of emotional tendencies in depression-related discourse. First, sentiment polarity analysis identifies the overall emotional orientation, distinguishing between positive and negative emotions. Second, specific emotion category analysis explores the frequency of key emotional expressions such as anger, sadness, and fear, which are closely linked to depression. Finally, semantic co-occurrence analysis investigates how different emotional words are interconnected, revealing patterns in emotional expression. Together, these analyses offer a comprehensive insight into the emotional landscape of depression-related self-disclosure on social media. To further analyze the overall emotional orientation and specific emotion categories in the self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression, Table 2 presents a detailed classification of emotions.

Classification of emotions.

| Emotional tendency | Major category | Sub-category | Frequency | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Joy | Happiness, reassurance | 445 | 2,136 |

| Goodness | Respect, praise trust, fondness, well-wishing | 1,691 | ||

| Negative | Anger | Anger | 160 | 9,838 |

| Sorrow | Sadness, disappointment, guilt | 1,405 | ||

| Fear | Panic, fear, embarrassment | 672 | ||

| Disgust | Annoyance, aversion, blame, envy, doubt | 7,601 |

As shown in Table 2, the use of negative emotional vocabulary in the self-disclosure of depression patients on social media far exceeds that of positive emotional vocabulary. This phenomenon is consistent with previous research, which indicates that individuals with depression generally hold a pessimistic outlook on life and exhibit negative emotional tendencies (Fan and Liu 2023). Particularly, the emotional category of “恶” (wu, ‘disgust’) (frequency: 7601)”, dominates the corpus, reflecting their tendency to express negative and hostile emotions when facing life’s frustrations and difficulties (Zhang 2022). Additionally, the emotional category of “好” (hao, ‘Goodness’), representing positive emotions, ranks second in frequency, which seems contradictory to the findings of previous studies that suggest depression patients rarely express positive emotions. Therefore, to further investigate the reasons behind the relatively frequent use of positive emotional vocabulary in the depression-related corpus, we generated a word cloud (see Figure 4) based on the positive emotional vocabulary in this study’s corpus and validated the findings through a semantic network analysis (see Figure 5).

Positive emotion word cloud.

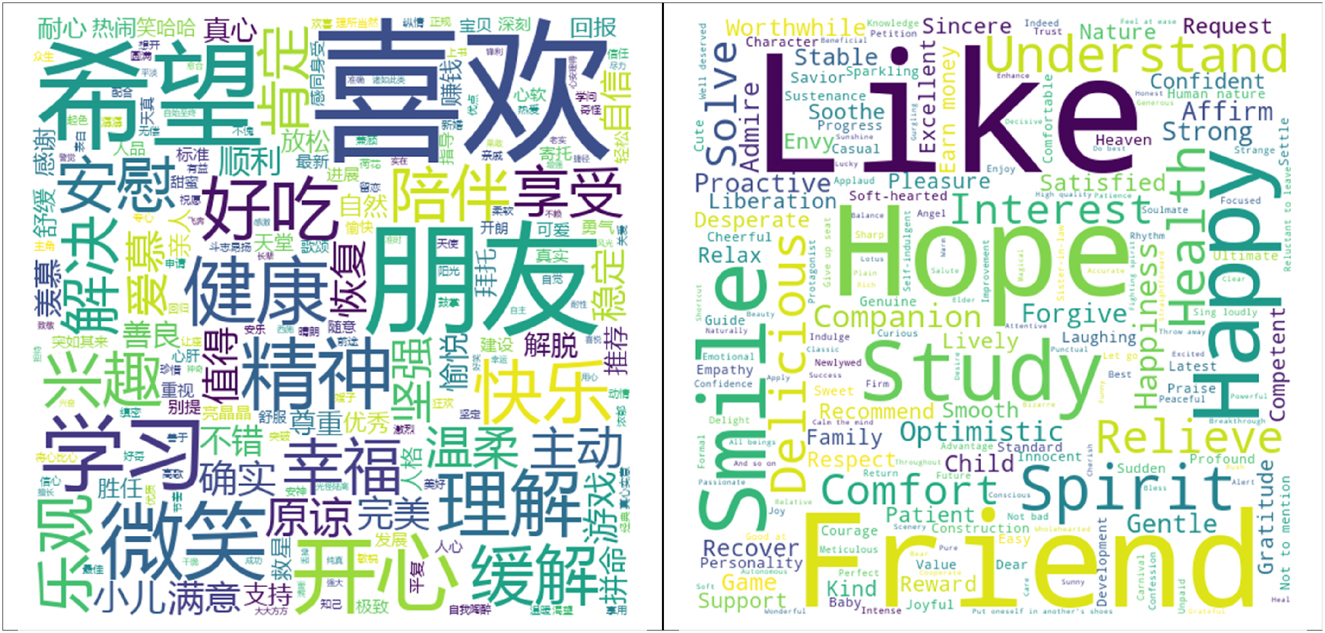

Co-occurrence network of “understand” in positive emotion.

As shown in Figure 4, the key terms in the positive emotional word cloud include “喜欢” (xihuan, ‘like’), “朋友” (pengyou, ‘friend’), “希望” (xiwang, ‘hope’), “开心” (kaixin, ‘happy’), “微笑” (weixiao, ‘smile’), “精神” (jingshen, ‘spirit’), “理解” (lijie, ‘understand or understanding’), “健康” (jiankang, ‘health’), and “快乐” (kuaile, ‘joy’). To some extent, this suggests that despite facing numerous challenges, depression patients still retain certain positive emotions and a hopeful outlook on the future. These factors may contribute to the establishment of a more positive self-perception and attitude towards life among the patients. Moreover, the presence of these positive emotional words also indicates that online social media platforms serve as a medium for emotional expression and social interaction for depression patients.

However, the high frequency of positive emotional vocabulary in the corpus does not equate to a substantial presence of positive emotional semantics. Specifically, it indicates that even typically positive vocabulary in specific contexts may carry negative emotional undertones. Therefore, interpreting such terms requires careful consideration of their contextual semantics and emotional associations within the discourse of depression. As shown in Figure 5, the word “理解” (ljie, ‘understand or understanding’) serves as a notable example. Although this word is generally categorized as a positive emotional term and appears frequently in the corpus, its strong association with words such as “感觉” (ganjue, ‘feeling’) and “痛苦” (tongku, ‘pain’) reveals a crucial phenomenon: in the discourse of individuals with depression, the word “理解” (ljie, ‘understand’) does not solely convey a positive emotional experience. Instead, this term is often closely linked to negative emotions such as “痛苦” (tongku, ‘pain’), suggesting that when individuals with depression discuss “理解” (ljie, ‘understand or understanding’), they are frequently expressing an awareness of their emotional state, particularly their experience of suffering, as illustrated in Example (3) below.

| 感觉自己经常在向别人证明自己非常痛苦。别人的理解对我非常重要, 这让我感觉自己不是孤立无援。但是不论是家人还是朋友其实都没办法完全理解我。为什么我总要把变好的方法建立在别人身上呢。有时候甚至会为了让别人能理解我的有多痛苦, 会擅自让一些本有机会挽回的事情朝糟糕的方向发展, 总是想让痛苦变得具象化, 变得大众化, 变得直接, 那样才能让别人真的意识到我处在非常痛苦的情绪当中。[I often feel like I’m constantly trying to prove to others just how much I’m suffering. Other people’s understanding matters a lot to me, which makes me feel like I’m not completely alone. But in reality, neither family nor friends can fully understand me. Why do I always base my recovery on others? Sometimes, I even let situations that could have been salvaged deteriorate just so others can understand how much pain I’m in. I always want my suffering to take a tangible form, to become something universally recognizable, something direct. Only then do I believe that others will truly realize the depth of my emotional distress.] |

In Example (3), the three occurrences of “理解” (lijie, ‘understand or understanding’) reflect different emotional orientations and meanings in the self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression. The first “understanding” signifies the speaker’s strong need for emotional support, hoping that being understood by others can alleviate their feelings of loneliness and helplessness. While this carries a positive emotional connotation, it is fundamentally rooted in the recognition of negative emotions. The second “understand” conveys disappointment and frustration over others’ inability to fully comprehend the speaker’s suffering, reinforcing a negative emotional outlook and intensifying their sense of isolation. The third “understand” reveals an extreme desire for others to recognize their pain, to the extent that the speaker resorts to self-destructive behaviors as a means of achieving this recognition. This carries a complex emotional significance, simultaneously reflecting the individual’s longing for emotional connection and the struggle and helplessness embedded in their emotional expression. Therefore, as a positive emotional term, “理解” (lijie, ‘understand or understanding’) in the self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression reflects complex emotional semantics through its collocation with different words.

4.3 Thematic topics

To uncover the core topics in the online self-disclosure of individuals with depression, this study employs the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic model to analyze the corpus. The LDA model extracts latent topics from textual data, enabling the identification of primary discussion topics within the online discourse of individuals with depression. Utilizing the LDAvis visualization tool, the self-disclosure discourse is categorized into five distinct topics (see Figure 6), reflecting key dimensions of their experiences: Emotional Representation, Emotional Challenges, Life Status, Pathological Manifestations, and Emotional Needs. The detailed analysis of each topic is presented in Table 3.

LDA model visualization.

Distribution of high-frequency words and weights in LDA model.

| Serial number | Topic category | HFW/W | HFW/W | HFW/W | HFW/W | HFW/W | HFW/W | HFW/W | HFW/W | HFW/W | HFW/W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic 1 | Emotional representation | Emotion/0.032 | Like/0.025 | Breakdown /0.016 | Lead to /0.016 | Insomnia/0.015 | Sad/0.013 | Influence/0.013 | Symptom/0.013 | Afraid/0.012 | Stable/0.012 |

| Topic 2 | Emotional challenges | Feeling/0.027 | Don’t want to /0.026 | Cry/0.025 | Bitterness /0.022 | Death/0.018 | Hard to bear/0.017 | Take medicine/0.015 | Like/0.014 | Pain/0.013 | Sleep/0.013 |

| Topic 3 | Life status | Depression /0.029 | Feeling /0.023 | Depression /0.020 | Pain/0.015 | Emotion /0.011 | Teachers/0.011 | Medicine/0.010 | Friends/0.010 | Illness/0.010 | Hospital/0.010 |

| Topic 4 | Pathological manifestations | Symptom /0.037 | Patient /0.029 | Anxiety disorder /0.026 | Anxiety/0.025 | Pain/0.017 | Somatic/0.016 | Panic/0.014 | Article /0.013 | Decline /0.013 | Performance /0.013 |

| Topic 5 | Emotional needs | Depression /0.027 | World /0.020 | Living/0.013 | Not reaching/0.013 | Love/0.013 | Hope/0.012 | Feeling/0.011 | Like/0.010 | Decline/0.013 | Hug/0.010 |

-

HFW, high frequency words; W, weights.

4.3.1 Topic one: emotional representation

The topic of Emotional Representation primarily addresses how individuals with depression express their emotional fluctuations and psychological experiences online via social media. This topic typically reveals the direct emotional states of the patients and how these emotions impact their daily lives. High-frequency words in this topic, such as “情绪” (qingxu, ‘emotion’), “喜欢” (xihuan, ‘like’) and “难过” (nanguo, ‘sad’) indicate that patients express a wide range of emotions on social media. This not only reflects the volatility of their emotions but also demonstrates the varying intensity of these emotions. For instance, “喜欢” (xihuan, ‘like’) might refer to moments of positive emotion, whereas “难过” (nanguo, ‘sad’) and “害怕” (haipa, ‘afraid’) reflect deeper negative emotional experiences (Herrman et al. 2019). Additionally, words like “裂开” (liekai, ‘break down’), “导致” (daozhi, ‘lead to’), ‘失眠” (shimian, ‘insomnia’), and “影响” (yingxiang, ‘influence’) suggest that patients are concerned not only with the emotions themselves but also with the long-term effects of emotional fluctuations on their health (Fan and Liu 2023). In summary, the self-disclosure discourse under this topic primarily reveals how individuals with depression navigate their complex inner experiences through diverse and intense emotional expressions on social media. These emotional expressions are not only direct reflections of their psychological states but also serve as a means for them to release emotions and alleviate the stress brought on by those emotions.

4.3.2 Topic two: emotional challenges

The topic of Emotional Challenges pertains to the specific difficulties patients encounter when managing their personal emotions and psychological distress. This often includes the struggle against deep emotional pain and the search for ways to cope with such suffering. High-frequency words like “苦涩” (kuse, ‘bitterness’) and “痛苦” (tongku, ‘pain’) highlight the intense inner conflict and struggles faced by patients (Zhang 2022), while “吃药” (chiyao, ‘take medicine’) and “睡觉” (shujiao, ‘sleep’) reflect the practical measures they take to alleviate these emotions, sometimes even extending to extreme solutions like “死” (si, ‘death’). Additionally, high-frequency words like “哭” (ku, ‘cry’) and “不想” (buxiang, ‘don’t want’) may express a psychological state of avoidance and resistance (Zhang 2022), which are natural reactions for patients facing extreme emotional pressure. The online discourse in topic two focuses on how individuals with depression manage intense emotions, revealing the severe health crises they face. Consequently, this category serves as a crucial linguistic marker for mental health professionals when providing support and intervention.

4.3.3 Topic three: life status

The topic of Life Status in the online discourse of individuals with depression focuses on aspects of their daily lives affected by depression, particularly in terms of social interactions, health management, and overall quality of life. Patients often express difficulties related to communication with “朋友” (pengyou, ‘friends’) and “老师” (laoshi, ‘teachers’) on social media, reflecting potential interpersonal relationship barriers they face in social settings (Yan and Liu 2022), as illustrated in Example (4).

| 老师只喜欢成绩好的学生, 人真的能在不被爱和不被关注的情况下枯萎窒息。[Teachers only favor students with good grades. A person can truly wither and suffocate when they are neither loved nor noticed.] |

Example (4) illustrates the speaker’s discomfort and feelings of alienation during social activities. This social difficulty is not limited to interactions with friends and within educational environments but may extend to a broader social circle, demonstrating how depression can impair patients’ social abilities and participation in society. Additionally, words like “药” (yao, ‘medicine’) and “医院” (yiyuan, ‘hospital’) reveal the reality that patients must rely on the medical system to manage depressive symptoms, while “生病” (shengbing, ‘illness’) further indicates that, beyond mental health issues, patients may also be dealing with other health problems. This suggests that the impact of depression is comprehensive, affecting not only mental health but also overall physical well-being.

4.3.4 Topic four: pathological manifestations

This topic focuses on the physiological impacts and physical symptoms brought about by depression, offering a direct description of the patients’ health status. Depression is not only an abnormal psychological state but also triggers a range of physical symptoms, such as chronic pain, sleep disorders, and digestive issues (Lian 2020). In the health discourse on social media, patients frequently mention issues related to “疼痛” (tengtong, ‘pain’) and “躯体” (quti, ‘somatic’), which not only reflect their daily struggles but also highlight the inseparable connection between mental and physical health, as illustrated in Example (5).

| 有时候想死并不是因为想不开或者想开了, 纯纯是因为躯体化症状太痛苦[苦涩]头痛, 呕吐, 心悸, 胸闷气短,浑身发抖到底有没有缓解的办法啊。[Sometimes, the thought of death does not stem from an inability to resolve life’s complexities or from having resolved them entirely. Instead, it arises simply because the somatic symptoms of depression are unbearably painful. The headaches, nausea, heart palpitations, chest tightness, shortness of breath, and full-body tremors. Is there truly any way to alleviate them?] |

In Example (5), the patient, by describing a series of specific physiological sensations, not only conveys a direct experience of their symptoms but also attempts to seek understanding and potential solutions. In this context, social media serves not only as a channel for expressing and sharing the pain caused by the illness but also as a means to seek concrete solutions.

4.3.5 Topic five: emotional needs

This topic in online discourse highlights the need for emotional support and understanding among depression patients on social media, clearly indicating their intent to seek help and support. High-frequency words such as “爱” (ai, ‘love’), “希望” (xiwang, ‘hope’) and “抱抱” (baobao, ‘hug’) directly reveal their need for emotional comfort (Hu 2023), as illustrated in Example (6).

| 我是个孤独的人 但我也渴望爱与被爱。[I am a lonely person, but I still long to love and be loved.] |

Example (6) reveals the deep sense of loneliness experienced by the patient, along with a strong desire for emotional support. As a result, individuals with depression use social media platforms to express their emotional needs, attempting to break through the isolation imposed by depression. This further indicates that under the dual pressures of inner turmoil and social barriers caused by depression, the “抑郁症超话” (yiyuzheng chaohua, ‘depression super topics’) online community on social media serves as a crucial channel for social and emotional support. Through this platform, patients can connect with others who may be experiencing similar feelings, which not only helps to alleviate the despair and loneliness felt in real-life social interactions but also contributes to the construction of a supportive online social network (Yan and Liu 2022).

In summary, this section, through the use of the LDA topic model, delves into the online self-disclosure discourse of depression patients on social media, revealing five key topics: emotional representation, emotional challenges, life status, pathological manifestations, and emotional needs. Together, these topics paint a comprehensive picture of how individuals with depression express their complex emotional experiences and life challenges in the digital space, while also highlighting their urgent need for social support and emotional understanding. Notably, beyond the direct negative impacts of their life status and physical health, the emotional representations of fluctuations, crises, and needs are critical factors that cannot be overlooked in the process of supporting and understanding depression individuals with depression.

5 Conclusions

In this study, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the online self-disclosure discourse of depression patients within the “抑郁症超话” (yiyuzheng chaohua, ‘depression super topics’) community on microblog in China, focusing on three aspects: linguistic features, emotional self-disclosure, and topic characteristics. By integrating natural language processing tools, this research revealed the primary linguistic usage features, emotional tendencies and categories, and primary topics in the discourse of individuals with depression. The findings are as follows: First, the highest frequency is observed for the singular first-person pronoun “我” (wo, ‘I’) demonstrating the self-focused narrative mode prevalent in Chinese online depression discourse. Notably, the use of third-person pronouns constructs a state of isolation between individuals with depression and the external world in terms of both external identity and internal emotions, further highlighting the confrontational nature of the discourse. Besides, in terms of lexical usage features, the online self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression in China can be categorized into three main types: i) frequent use of disease-related vocabulary, ii) frequent use of negative terms such as “no” or “not”, and iii) frequent use of emotional words. Second, the online self-disclosure discourse of individuals with depression in the Chinese context primarily exhibits a negative emotional orientation; however, the emotional orientation of the semantic content should be interpreted within the specific contextual meaning. Third, as for topic characteristics, the online self-disclosure on social media reveals five key topics: emotional representation, emotional challenges, life status, pathological manifestations, and emotional needs.

However, certain limitations should be acknowledged, notably those concerning the representativeness of the data sources as well as the broader consideration of cultural and contextual dimensions. These limitations suggest that future research needs to adopt more diverse data sources and methodologies to explore the expression of depression across different cultural contexts and to develop more targeted support and intervention strategies. In conclusion, this study reveals the expressive patterns and psychosocial needs of individuals with depression on social media, thereby offering a reference for advancing the understanding of this population. It is hoped that the findings of this study will encourage further research into the online self-disclosure discourse of the broader depression population and provide empirical support for advancing public health initiatives.

References

Brookes, Gavin & Kevin Harvey. 2016. Examining the discourse of mental illness in a corpus of online advice-seeking messages. In Lucy Pickering, Eric Friginal & Shelley Staples (eds.), Talking at work: Corpus-based explorations of workplace discourse, 209–234. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/978-1-137-49616-4_9Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Guangyu, Zhongting Yi & Yi Guan. 2022. Xiaofeizhe wanggou putaojiu de yingxiang yinsu ji yingxiao celue yanjiu [Research on the influencing factors and marketing strategies of consumer online wine purchases]. Zhongwai Putao yu Putaojiu [Sino-Overseas Grapevine & Wine] (5). 106–111.Search in Google Scholar

Dao, Bo, Thien Nguyen, Dinh Phung & Svetha Venkatesh. 2014. Effect of mood, social connectivity and age in online depression community via topic and linguistic analysis. In The 15th international conference on web information systems engineering (WISE). Thessaloniki, Greece: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.10.1007/978-3-319-11749-2_30Search in Google Scholar

Ding, Yating & Lin Wu. 2023. Qingnian qunqun yiyu huayu de fuhao biaozheng he hudong celue [The hidden and the visible: Symbolic representations and interaction strategies of depressive discourse among youth on “NetEase Cloud Music”]. Dangdai Qingnian Yanjiu [Contemporary Youth Research] (1). 98–111.Search in Google Scholar

Dixon, Melissa. 2016. Adolescents’ conceptualisations of depression and recovery: A discourse analysis. Nottingham: University of Nottingham Press PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Fairclough, Norman. 2003. Analysing discourse. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203697078Search in Google Scholar

Fairclough, Norman. 2013. Language and power. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315838250Search in Google Scholar

Fan, Hongshuo. 2022. Yiyuzheng baodao de baozhi huayu fenxi (2000–2020) [Newspaper discourse analysis of depression reports (2000–2020)]. Haikou: Hainan Normal University Press MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Fan, Wenrong & Feng Liu. 2023. Jiyu yiyuzheng huanzhe weibo pingtai shuju de wenben yuyi wajue yu qinggan fe [Text semantic mining and sentiment analysis based on Weibo platform data of depression patients]. Ruanjian Daokan [Software Guide] 22(10). 171–177.Search in Google Scholar

Giaxoglou, Korina. 2015. ‘Everywhere I go, you’re going with me’: Time and space deixis as affective positioning resources in shared moments of digital mourning. Discourse, Context & Media 9. 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2015.06.004.Search in Google Scholar

Herrman, Helen, Christian Kieling, Patrick McGorry, Richard Horton, Jeffrey Sargent & Vikram Patel. 2019. Reducing the global burden of depression: A Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission. The Lancet 393(10189). 42–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32408-5.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Jiayi. 2023. Yinmi yu kejian: Wangluo shipin zhong yiyuzheng huanzhe de jitong xushi yanjiu [Hidden and visible: A study on the pain narratives of depression patients in online videos]. Wuhan: Central China Normal University Press MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Guanlan & Xiaolu Zhou. 2021. Yiyuzheng huanzhe de yuyan shiyong moshi [The linguistic patterns of depressed patients]. Xinli Kexue Jinzhan [Advances in Psychological Science] 29(5). 838–848. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1042.2021.00838.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, Joy L., John L. Oliffe, Mary T. Kelly, Paul Galdas & John S. Ogrodniczuk. 2012. Men’s discourses of help-seeking in the context of depression. Sociology of Health & Illness 34(3). 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01372.x.Search in Google Scholar

Koteyko, Nelya & Daniel Hunt. 2018. Special issue: Discourse analysis perspectives on online health communication. Discourse, Context & Media 25. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2018.08.002.Search in Google Scholar

Lian, Yufang. 2020. Ziwo biaolu shijiao xia yiyuzheng qunti de shejiao meiti shiyong yanjiu [Research on social media use among depression groups from the perspective of self-disclosure]. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Lin, Deyu & Zimin Meng. 2020. Jiyu wangluo wenben fenxi yu ASEB zhage fenxi de bowuguan youke ganzhi yanjiu – Yi Guangdong Sheng Bowuguan wei li [Museum visitors’ perception based on online text analysis and ASEB grid analysis: A case study of Guangdong Museum]. Kexue Jiaoyu yu Bowuguan [Science Education and Museum] 6(4). 243–251.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Zhengguang & Yuchen Li. 2012. Zhuguanhua yu rencheng daici zhicheng youyi [Subjectification and pronominal reference shifts]. Waiguoyu [Foreign Languages] 35(6). 27–35.Search in Google Scholar

Lyons, Minna, Nazli D. Aksayli & Gayle Brewer. 2018. Mental distress and language use: Linguistic analysis of discussion forum posts. Computers in Human Behavior 87. 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.035.Search in Google Scholar

Mao, Taitian, Yuhao Wu & Wenjia Huang. 2023. Zizhiqu minzu bowuguan de youke zaixian dianping neirong wajue yu qinggan fenxi [Analysis of visitor online reviews and sentiment at regional ethnic museums]. Jingji Dili [Economic Geography] 43(8). 229–236.Search in Google Scholar

Peng, Zhikang, Xiaoming Jiang & Jiaxing Shi. 2024. Zhishi tupu he zhuti fenxi shiyu xia jin 20 nian (2003–2023) shejiao meiti wangluo qinggan huayu tezheng de yanjiu qushi fenxi [Research trends in social media network emotional discourse features over the past 20 years (2003–2023) from the perspective of knowledge graphs and thematic analysis]. Waiyu Yanjiu [Foreign Language Research] 41(4). 36–43, 75.Search in Google Scholar

Reali, Florencia, Tania Soriano & Daniela Rodríguez. 2016. How we think about depression: The role of linguistic framing. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 48(2). 127–136.10.1016/j.rlp.2015.09.004Search in Google Scholar

Rosario, Charlotte. 2023. Age-specific linguistic features of depression via social media. In Paper presented at the 8th Student Research Workshop associated with the International Conference Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing. Varna, Bulgaria, 6–8 September.Search in Google Scholar

Sharma, Neha & Kairit Sirts. 2024. Context is important in depressive language: A study of the interaction between the sentiments and linguistic markers in Reddit discussions. In Proceedings of the 14th workshop on computational approaches to subjectivity, sentiment, & social media analysis. Stroudsburg, PA: The Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2024.wassa-1.28Search in Google Scholar

Shi, Jiayi & Zhaowei Khoo. 2023. Online health community for change: Analysis of self-disclosure and social networks of users with depression. Frontiers in Psychology 14. 1092884. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1092884.Search in Google Scholar

Sun, Tiange. 2023. In sanshi nian Hanyu rencheng daici yanjiu zongshu [A review of research on Chinese personal pronouns over the past thirty years]. Jingu Wenchuang [Jingu Literature & Culture] 43. 128–130.Search in Google Scholar

Thompson, Riki & Rich Furman. 2018. From mass to social media: Governing mental health and depression in the digital age. Sincronia 73. 398–429.Search in Google Scholar

Valiakalayil, A. Aleyamma. 2015. Stress and depression discourses on self-help websites: What is their relation in the online context? Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan Press PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Vedula, Nikhita & Srinivasan Parthasarathy. 2017. Emotional and linguistic cues of depression from social media. In Proceedings of the 2017 international conference on digital health. London, UK: ACM Special Interest Group on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining.10.1145/3079452.3079465Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Yingjie, Jiuqi Zhu, Zuming Wang & Xiaowei Zhang. 2022. Ziran yuyan chuli zai wenben qinggan fenxi lingyu yingyong zongshu [A review of natural language processing applications in text sentiment analysis]. Jisuanji Yingyong [Journal of Computer Applications] 42(4). 1011–1020.Search in Google Scholar

Xu, Linhong, Hongfei Lin, Yu Pan, Hui Ren & Jiangmei Chen. 2008. Qinggan cihui benti de gouzao [Construction of the affective lexicon ontology]. Qingbao Xuebao [Journal of the China Society for Scientific and Technical Information] 27(2). 180–185.Search in Google Scholar

Yan, Qing & Yu Liu. 2022. Shejiao meiti pingtai yiyu qunti de shehui zhichi xunqiu yanjiu – jiyu dui Weibo “Yiyuzheng Chaohua” de kaocha [Research on social support seeking of depressive groups on social media platforms: An investigation based on Microblog “depression super topics”]. Xinwenjie [Journalism World] (6). 45–56, 64.Search in Google Scholar

Yip, Jesse W. C. 2024. A mediated discourse analysis of self-disclosure in online self-help groups for anxiety and depression. Digital Applied Linguistics 1. 2309. https://doi.org/10.29140/dal.v1.2309.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Yue. 2022. Yiyuzheng huanzhe meijie xingxiang jiangou dui gongzhong taidu de yingxiang yanjiu [Research on the impact of media image construction of depression patients on public attitudes]. Nanchang: Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics Press MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Pengrong & Shizhaoyun Shuai. 2023. Yiyuzheng huanzhe qinggan biaozheng de yuyong yanjiu – yi Weibo Chaohua wei li [Pragmatic study of emotional representation in depression patients: A case study of Microblog super topics]. Zhejiang Waiguoyu Xueyuan Xuebao [Journal of Zhejiang International Studies University] (6). 36–46.Search in Google Scholar

Zhu, Qiaoyun. 2011. Self-disclosure in online support groups for people living with depression. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.