Abstract

A number of studies on transitivity systems of languages have been conducted in the field of Systemic Functional Linguistics. Different linguists have described the transitivity systems of English, French, German, Japanese, Tagalog, Chinese, Vietnamese, Telugu, and Pitjantjatjara, adopting an upward approach which is not effective enough for discourse analysis. So far, there has been no description of the transitivity system of Myanmar in literature. The purpose of this paper is to put forward a clear description of the transitivity system of Myanmar that functions as one of the clause analysis methods from the experiential perspective. To construct a workable transitivity system of Myanmar, the present study follows He’s (forthcoming) (He, Wei. forthcoming. Categorization of experience of the world and construction of transitivity system of Chinese) new description of the Chinese transitivity system containing 32 types of processes that represent our experience of the world. Unlike previous studies, He (forthcoming) proposes autonomous and influential processes of action, mental, and relational clauses with no description of ergativity hypothesized by Halliday (1985) (Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1985. An introduction to functional grammar. London: Arnold) and Matthiessen (1995) (Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. 1995. Lexicogrammatical cartography: English systems. Tokyo: International Language Sciences Publishers). This new model is more comprehensive and effective than previous ones because it adopts a downward approach which can smoothly be applied to discourse analysis. In this paper, the transitivity analysis of Myanmar clauses is performed in accordance with the theories put forward by He (forthcoming) and the semantic configurations of 32 processes in Myanmar transitivity system are illustrated with authentic examples. Findings show that the proposed transitivity system of Myanmar can analyze clauses effectively and it is compatible with the discourse analysis of Myanmar. These findings will make an important contribution to further study of the systemic functional grammar of Myanmar.

1 Introduction

Among the three metafunctions: ideational (including experiential and logical), interpersonal, and textual in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL hereafter; Halliday 1985, 1994; Halliday and Matthiessen 2004, 2014), the experiential metafunction refers to the representation of the experience of the world as different types of processes, which construes our experience in the physical, social, mental, and abstract world by the process types in transitivity system (He forthcoming). In the field of SFL, there have been a growing number of studies on modeling the transitivity systems of languages. Halliday (1985), Matthiessen (1995), Martin et al. (2010), and Fawcett (1980, 1987, forthcoming) are famous scholars who have developed the English transitivity system. Following Halliday (1985) and Matthiessen (1995), Caffarel (2004), Steiner and Teich (2004), Teruya (2004), Martin (2004), Halliday and McDonald (2004), Thai (2004), Prakasam (2004), and Rose (2004) have put forward the transitivity systems of French, German, Japanese, Tagalog, Chinese, Vietnamese, Telugu, and Pitjantjatjara respectively in Caffarel et al. (2004). Despite an increase in transitivity studies, no systemic functionalist has described the transitivity system of Myanmar so far. Thus, the present study investigates how Myanmar people’s experience of the world is categorized and how many types of processes can be distinguished in Myanmar transitivity system.

Previous studies on transitivity deploy an upward approach which is not powerful enough to be applied to discourse analysis. Li and Song (2005) criticize Halliday and Matthiessen’s (2004) description of participants and combination of transitivity analysis and ergativity analysis (as quoted in He et al. 2017: 14). When Halliday’s (1985) description of the English transitivity system is applied to the discourse analysis of Myanmar clauses, many ambiguous matters are encountered in the categorization of participant roles and processes. By criticizing the previous descriptions of the transitivity system of Chinese, He (forthcoming) presents a new model of the Chinese transitivity system with detailed categorization of 32 processes. Unlike previous scholars, including Fawcett, her new model adopts a downward approach which is an effective method of discourse analysis. It has been proved to be feasible by being applied to the transitivity analysis of more than 200 Chinese texts. It makes the indeterminate participant roles and processes in some Myanmar clauses soluble. Thus, this study employs He’s (forthcoming) new model to construct a Myanmar transitivity system. The result forms part of a larger study of the other two metafunctions: interpersonal and textual to propose the systemic functional grammar of Myanmar.

2 Previous studies on the transitivity systems of particular languages

In recent years, transitivity studies, especially the constructions of the transitivity systems that represent the experience of the world through process types, have gained considerable ground within the field of SFL. As an effective tool for discourse analysis, Halliday (1985, 1994 presents a description of English transitivity. Based on Halliday’s hypotheses, Matthiessen (1995) proposes his own transitivity system network. Later, Halliday and Matthiessen (2004, 2014 modify Halliday’s (1994) work.

According to Halliday (1985, 1994 and Halliday and Matthiessen (2004, 2014, there are six major types of processes: material, mental, verbal, relational, behavioral, and existential. Material processes consist of two subtypes: doing type that shows action and happening type that shows event. There are two main participants in this process: Actor and Goal. Actor is an inherent participant serving as the doer of the action in both intransitive and transitive material clauses, whereas Goal is inherent in transitive material clauses serving as a second participant affected by the action. In addition to these two participants, the additional ones that may be involved in the material processes are Scope, Recipient, Client, and Attribute. Recipient and Client are the participants taking the semantic role of the beneficiary of the process of giving goods and services respectively. Scope represents the domain over which the process takes place; for example, a newspaper as in He is reading a newspaper. Attribute is the participant that construes the resultant qualitative state of Actor or Goal after the process has been completed; for example, clean as in You should keep the surroundings clean. Mental processes are known as processes of sensing: feeling, wanting, thinking, and perceiving. These processes contain two participants: Senser and Phenomenon. Verbal processes are processes of saying which have four participants: Sayer, Receiver, Verbiage, and Target. Relational processes contain three major subtypes: intensive, circumstantial, and possessive and two modes: attributive and identifying. Each mode combines with three types, so there are altogether six relational processes. The main participants involved in these processes are Carrier and Attribute in intensive/circumstantial attributive relational processes, Identified-Identifier/Token-Value in intensive/circumstantial identifying relational processes, Carrier–Attribute/Possessed–Possessor in possessive attributive relational processes, and Identified–Identifier/Token–Value/Possessed–Possessor in possessive identifying relational processes. Behavioral processes express human behavior both physiologically and psychologically, including breathing, coughing, laughing, smiling, dreaming, staring, and peeping. Typically, there is only one participant in behavioral processes, i.e. Behaver; for instance, he as in He’s yawning. But another participant, the Behavior may be involved in some behavioral processes; for instance, a great yawn as in He gave a great yawn. This participant is equivalent to the Scope of a material clause (Halliday and Matthiessen 2004: 251). Existential processes represent the existence or the events of both animate and inanimate things. These processes include only one pivotal participant, the Existent. Another special category of processes between the existential and the material is meteorological processes which represent our direct experience of events relating to weather and have no participant. In these processes, the subject may be either it or there, which has no function in transitivity (Halliday and Matthiessen 2004: 259). In terms of Halliday and Matthiessen (2004), onto the table as in Ma Aye Phyu put the bag onto the table is classified as a Circumstance. It is an essential part of the clause, without which the clause sounds odd. So it is more concrete to classify it as a participant rather than as a Circumstance in the transitivity structure. This makes it clear that Halliday and Matthiessen (2004) do not go further to standardize the differentiation of participant roles from circumstances, and a more delicate classification of participants is needed.

Unlike Halliday (1985, 1994, the major six process types are contracted to four by Matthiessen (1995). They are the material, mental, relational, and verbal processes. The behavioral process is incorporated into the material process, and the existential process is incorporated into the relational process. An experiential clause simplex is composed of two regions: circumstantial and nuclear transitivity. Circumstantial transitivity is formed by various types of circumstance such as cause, location, manner, and other circumstantial systems, while nuclear transitivity is the combination of process type (material/mental/verbal/relational) and agency (effective/middle), functioning as a two-dimensional paradigm. As regards classification of participants, Matthiessen (1995) tries to combine the transitivity analysis of the process-type specific functions of Actor, Senser, Sayer, etc. and the ergative analysis of the generalized ones of Agent, Medium, and Range. Although there is the convergence of these two modes of analysis in participant functions of all process types, Matthiessen’s (1995: 207) transitivity system network only illustrates this convergence in the material process, rather than in all the types of processes (as quoted in He et al. 2017: 12). Matthiessen’s (1995) effective material, mental, and relational clauses in agency system are analogous to He’s (forthcoming) influential processes of action, mental, and relational clauses. However, there are no transitivity structures of effective clauses in behavioral, verbal, and existential processes in Matthiessen (1995). The clause The news made her very happy is classified as the effective attributive relational clause by Matthiessen (1995: 208). In this effective process, there is a causer the news, i.e. the Agent that brings about the emotive mental process of being happy rather than the attributive relational process. Thus, it is more concrete to take this clause as the effective emotive mental process rather than the effective attributive relational process.

Based on Halliday’s (1985, 1994 and Matthiessen’s (1995) hypotheses on transitivity, Caffarel’s (2004) description of the transitivity system of French is presented from two perspectives: the transitive (process type system) and the ergative (agency system). From the transitive perspective, French clauses construe different domains of experience (doing-&-happening, sensing-&-saying, and being-&-having) through three major process types: doing, projecting, and being processes. From the ergative perspective, a process type is recognized as the effective one that is brought about by an external cause or the middle one that is not brought about by an external cause. Although Caffarel (2004) adopts two models of transitivity: the ergative model and the transitive model in her description of the transitivity system of French, she does not specify the ergative analysis of participant functions in all process types.

In terms of Halliday (1985) and Matthiessen (1995), Steiner and Teich (2004) describe the German transitivity system containing four major types of processes: material, mental, relational, and verbal. The participants involved in these processes are Actor + Goal for material processes, Senser + Phenomenon for mental processes, Attribute + Carrier for relational processes, and Sayer + Verbiage for verbal processes. Since German is an inflectional language, it has a case system which marks syntactic functions. In this description of the German transitivity system, the participants are realized in nominative, dative or accusative case according to their syntactic functions. Steiner and Teich (2004) assert that the syntactic means of the ergative pattern in German are more complex than those in English. Like Caffarel (2004), they do not make a specification of the ergative pattern in all the process types. In their description of the German transitivity system, the morphological case system is extensively used to realize the participant roles.

Based on Halliday and Matthiessen (1999), Teruya (2004) puts forward the transitivity system of Japanese in terms of two primary systems: nuclear transitivity and circumstantial transitivity. His process type system in Japanese has four major processes: verbal, mental, relational, and material. The participant functions in processes are realized by grammatical markers which differentiate the participants from circumstances.

Martin (2004) presents the transitivity system of Tagalog containing three primary types of processes: mental, material, and relational whose aspects are realized by a range of affixation. The categorizations of process types and participants are marked by focus affixes and markers in his transitivity system of Tagalog.

Halliday and McDonald (2004) propose the Chinese transitivity system containing four major types of processes: material, mental, verbal, and relational. This transitivity system mainly focuses on nuclear transitivity but briefly on circumstantial transitivity and agency system. Thai’s (2004) Vietnamese transitivity system also consists of four major types of processes: material, mental, verbal, and relational which are basically coextensive with those in Matthiessen (1995). His categorizations of process types and participant roles are specified in terms of the transitive model but not the ergative model in agency system.

With reference to Halliday’s (1967, 1968) operative-receptive orientation at the rank of clause, Prakasam (2004) presents five classes of Telugu clauses which have no active-passive distinction from the experiential perspective, namely: identificatory, possessive, mental, existential, and material. Rose (2004) describes the transitivity system of Pitjantjatjara including three figure types: action, signification, and relation. His action processes with two subtypes of effective and non-effective cover Halliday’s material and behavioral processes. His signifying processes are composed of mental and verbal processes. His relational processes cover Halliday’s attributive and identifying relational processes. Following Matthiessen (1995), the generalized ergative functions are mapped onto the process-type specific transitive functions in participant identification in Rose (2004).

All earlier works on transitivity adopt an upward approach. Unlike previous studies, this paper focuses on a downward approach practiced by He’s (forthcoming) new model of the Chinese transitivity system in conducting the discourse analysis of Myanmar clauses effectively from the experiential perspective. He’s (forthcoming) new description of the Chinese transitivity system consists of 32 processes that represent our direct experience of the physical, social, mental, and abstract world. The three major types of processes in this new model are action, mental, and relational processes. Each process can be either autonomous or influential. Autonomous processes represent our direct experience of goings-on, whereas influential processes construe our experience of entities or events influencing goings-on around us and inside us. An outside participant that is the Agent of the influenced process becomes involved in influential processes. Action processes are further divided into four subtypes: happening, doing, creating, and behaving. Mental processes are classified into five subcategories: emotive, desiderative, perceptive, cognitive, and communicative. Relational processes have seven subtypes: attributive, identifying, locational, directional, possessive, correlational, and existential. He (forthcoming) makes a specific categorization of process types and participant roles, including simple participant roles and compound participant roles in her new model of the transitivity system of Chinese. Although Halliday (1985, 1994 puts forward the transitivity structures of effective and middle clauses in the ergative analysis which is also known as the agency system in Matthiessen (1995), they cannot make a much more delicate description of effective structures in all the types of processes, especially in behavioral, verbal, and existential processes. He (forthcoming) makes a further description of the transitivity structures of influential clauses in all the types of processes. Therefore, the present study, following He’s (forthcoming) hypotheses on transitivity, will put forward a systematic and comprehensive transitivity system of Myanmar.

3 Construction of the transitivity system of Myanmar

Transitivity system is concerned with the construal of the experience of the world around us and inside us. As the transitivity system shows the experiential meanings, it has a one-to-one relationship with experience and exists at the semantics level of language, so it can be applied to discourse analysis. Following all the major processes proposed by He (forthcoming) in her description of the transitivity system of Chinese, the present study constructs the transitivity system of Myanmar in that the Myanmar people’s experience of the physical, social, mental, and abstract world is construed by autonomous and influential processes of three primary types of processes: action, mental, and relational in accordance with those psychological features that make people easy to perceive, to form a mental image, to communicate with others, to learn, to remember, and to use. All these subcategories have great significance in the hierarchy of categorization of process; and distinguishing between each other makes an important contribution to a more revealing text analysis. The frequent semantic configurations of Myanmar transitivity are demonstrated by Table 1.

The frequent semantic configurations of Myanmar transitivity.

| Process type | Autonomous/influential | Process subtype | Semantic configuration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action process | Autonomous | Happening | Ag + Pro Af + Pro |

| Doing | Ag + Pro Af + Pro Ag + Af + Pro Ag + Ra + Pro Dir: Des + Ag-Ca + Pro Af-Ca + Dir: So + Dir: Des + Pro Ag + Af-… + Af-… + Pro |

||

| Creating | Cre + Pro Ag + Cre + Pro |

||

| Behaving | Behr + Ra + Pro Behr + Pro |

||

| Influential | Happening | Ag + Af[[Af + Pro]] | |

| Doing | Ag + Af[[Af + Pro + Ag]] + Pro Ag + Af [[Ag + Af + Pro]] + Pro Ag + Af[[Ag + Pro]] + Pro |

||

| Creating | Ag + Af[[Ag + Cre + Pro]] + Pro | ||

| Behaving | Ag + Af[[Behr + Pro]] | ||

| Mental process | Autonomous | Emotive | Em + Ph + Pro Em + Pro |

| Desiderative | Desr + Ph + Pro Ph + Desr + Pro |

||

| Perceptive | Perc + Ph + Pro | ||

| Cognitive | Cog + Ph + Pro Ag-Cog + Ph + Pro |

||

| Communicative | Comr + Comee + Pro Comd + Comr + Pro Comr-Comee + Pro Comr + Comd + Pro Comr + Comee + Comd + Pro Comee + Comr + Comd + Pro |

||

| Influential | Emotive | Ag + Af[[Em + Pro]] + Pro | |

| Desiderative | Ag + Af[[Desr + Ph + Pro]] + Pro | ||

| Perceptive | Ag + Af[[Perc + Ph + Pro]] + Pro | ||

| Cognitive | Ag + Af[[Cog + Ph + Pro]] | ||

| Communicative | Ag + Af[[Comr + Comd + Pro]] | ||

| Relational process | Autonomous | Attributive | Ca + Pro Ca + At + Pro |

| Identifying | Tk + Vl + Pro | ||

| Locational | Ca + Loc + Pro Ag-Ca + Loc + Pro Af-Ca + Loc + Pro |

||

| Directional | Ca + Dir: So + Dir: Des + Pro Dir: Des + Ca + Pro |

||

| Possessive | Posr + Posd + Pro | ||

| Correlational | Cor1-Cor2 + Pro Cor1 + Cor2 + Pro |

||

| Existential | Ext + Loc + Pro Loc + Ext + Pro |

||

| Influential | Attributive | Ag + Af[[Ca + Pro]] + Pro | |

| Identifying | Af[[Tk + Vl]] + Ag + Pro | ||

| Locational | Ag + Af[[Ca + Loc + Pro]] + Pro | ||

| Directional | Ag + Af[[Ca + Dir: Des + Pro]] + Pro | ||

| Possessive | Ag + Af[[Posr + Posd + Pro]] | ||

| Correlational | Af[[Cor1 + Cor2]] + Ag + Pro | ||

| Existential | Ag + Af[[Loc + Ext + Pro]] |

The detailed accounts of all the subtypes involved in autonomous and influential processes of action, mental, and relational clauses in Myanmar are given in Sections 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3 below.

3.1 Autonomous and influential action processes

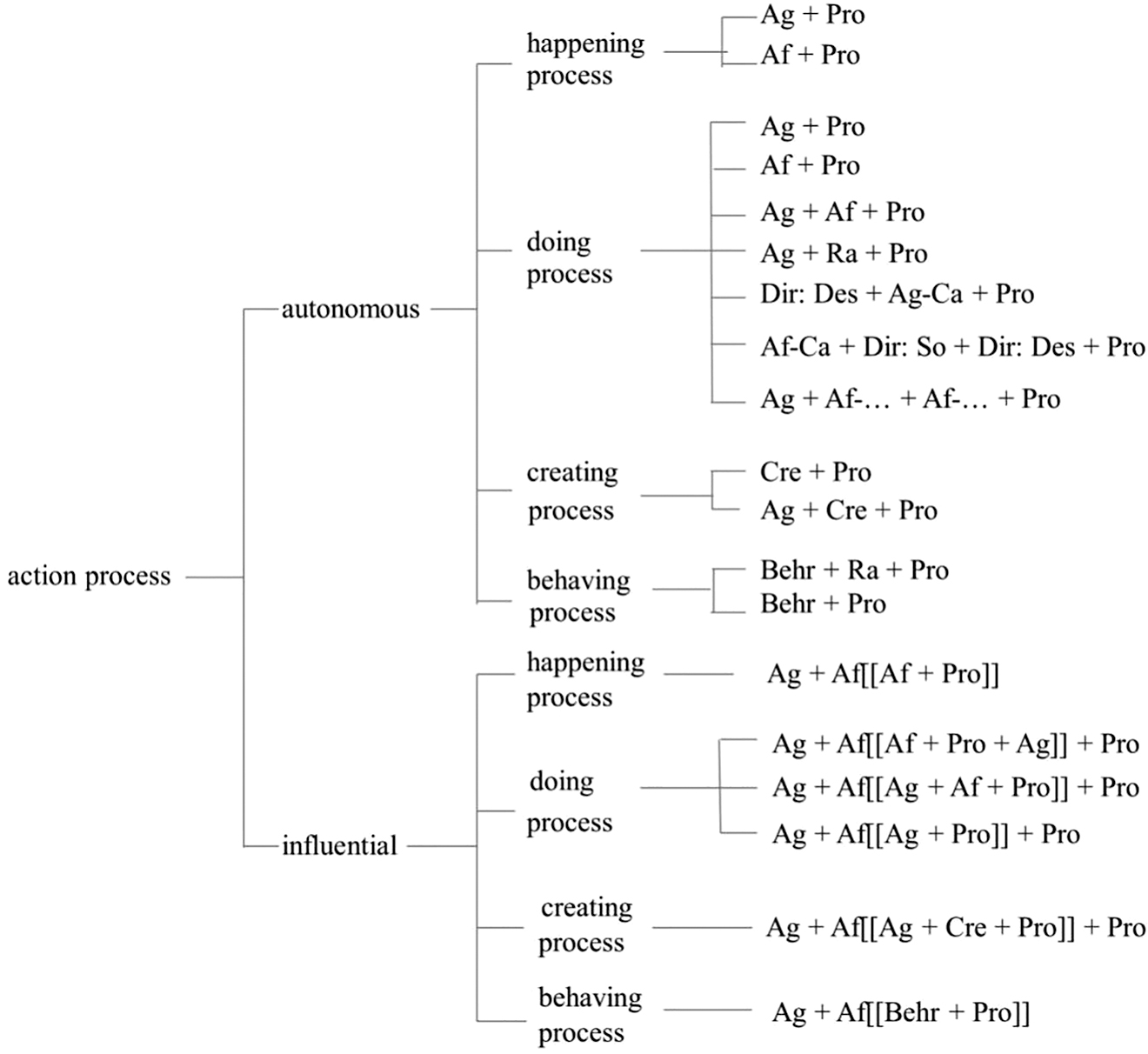

Our experience of the physical and the social world is construed by autonomous and influential action processes (He forthcoming). They can be distinguished into autonomous and influential happening, doing, creating, and behaving action processes. The common participant role configurations in each subtype are shown in Figure 1.

Major options of participant role configurations in action processes.

3.1.1 Autonomous happening action process

He (forthcoming) states that our direct experience of a variety of happenings in the physical and social world is described by autonomous happening action processes which contain one PR that may take the role of the Agent or the Affected. See examples (1) and (2).

| moe=le | ywar-ze-bin. |

| rain=addconn | fall-still.prog-decl.sentsuf |

| Ag | Pro |

| ‘It is still raining.’ | |

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 50) | |

| tharrgyee | maunpyonn | sonn-shar-bye. |

| elder.son | Mg.Pyone | die-compa-pfv.decl.sentsuf |

| Af | Pro | |

| ‘The elder son, Mg Pyone has died.’ | ||

| (Lae Twin Thar Saw Chit 2004: 276) | ||

Influential happening action processes are the processes where happenings in the physical and social world are influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). Two main PRs: The Agent and the Affected are involved in these processes. The Affected is an event brought about by the Agent. This influenced event is construed by a happening action process as shown in example (3) below.

| ahmaik | meeshotchinn-the | meelaunhmu-go | phyitpwarr-zay-the. |

| garbage | burning-sbjmark | fire-objmark | break.out-caus-prs.decl.sentsuf |

| Ag | Af[[Af | Pro]] | |

| ‘Burning the garbage causes fire.’ | |||

| (http://sealang.net/burmese/bitext.htm) | |||

3.1.2 Autonomous doing action process

He (forthcoming) defines that our direct experience of doings in the physical and social world is represented by autonomous doing action processes, in which there may be one, two, or three PRs. In one-role processes, there is only one pivotal PR that is either the Agent or the Affected, as shown in examples (4) and (5).

| lay-the | meepho | dagarrbauk-dwinnthot | toewin-nay-the. |

| wind-sbjmark | kitchen | door-into.all | blow-prog-decl.sentsuf |

| Ag | Cir: Pl | Pro | |

| ‘The wind is blowing into the door of the kitchen.’ | |||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 154) | |||

| phwinthtarrthaw | dagarr-myarr-go | paik-i. |

| open.mod | door-plmark-objmark | close-prs.decl.sentsuf |

| Af | Pro | |

| ‘The open doors are closed.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 29) | ||

In two-role processes, another PR, the Affected or the Range is involved. Range is a kind of Affected which is hardly impacted by the action. It is, in fact, the scope of the action. Examples (6) and (7) illustrate the semantic configurations of two-role action processes.

| thetthet-the | hla-go | phet-laik-the. |

| Thet.Thet-sbjmark | Hla-objmark | hug-pfv-decl.sentsuf |

| Ag | Af | Pro |

| ‘Thet Thet hugged Hla.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 47) | ||

| maunlueaye:=le | thadinnzar-go | phat-hlyetnay-i. |

| Mg.Lu.Aye.m=addconn | newspaper-objmark | read-prog-decl.sentsuf |

| Ag | Ra | Pro |

| ‘Mg Lu Aye is reading a newspaper.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 19) | ||

Examples (8) and (9) are compound processes in that the autonomous doing action process is conflated with the autonomous directional relational process. A detailed account of the autonomous directional relational process will be given in Section 3.3.

| akhann-htethot | maunlueaye: | winywaytthwarr-i. |

| room-into.all | Mg.Lu.Aye | enter.pfv-decl.sentsuf |

| Dir: Des | Ag-Ca | Pro |

| ‘Mg Lu Aye entered the room.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 29) | ||

Example (8) consists of two participants. One is a compound PR, the Ag-Ca, which takes the roles of two participants, the Agent and the Carrier by performing the action of going into a certain place and as a result achieving a certain attribute of reaching there. Another PR is a simple one, the Direction, which can be further classified into three subtypes: Source, Path, and Destination.

| mortorkarr-thonn-laye:-see-dot-hmar=le | yaukkyarr | |

| car-three-four-clf-plmark-sbjmark=addconn | husband(gen) | |

| Af-Ca | Dir: So | |

| ein-hma | ||

| house-from.ablmark | ||

| meinnma | ein-thot | saiksaikmyaikmyaik |

| wife(gen) | house-to.all | directly.mod |

| Dir: Des | Cir | |

| thwarr-gya-gon-i. | ||

| go-plmark-pfv-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘Three or four cars directly went from the groom’s house to the bride’s house.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 24–25) | ||

Example (9) consists of another compound PR, the Af-Ca, which takes the roles of two participants, the Affected and the Carrier by being affected by the action and as a result achieving a certain attribute. Three-role processes include three participants, the Agent and two Affected PRs, as shown in example (10). These two Affected PRs are usually compound participant roles which are related to each other as a result of the action of possessing.

| mayre-the | onnthee-chauk-ta-lonn-go | aphoegyee-arr |

| Mary-sbjmark | coconut-dried.mod-one-clf-acc | old.man-dat |

| Ag | Af-Posd | Af-Posr |

| paye:-laik-the. | ||

| give-pfv-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘Mary has given a dried coconut to the old man.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 119) | ||

Influential doing action processes are the processes where doings in the physical and the social world are influenced by our experience of entities or events (He, forthcoming). They consist of an additional PR, the Agent that brings about a doing action process, as shown in examples (11) and (12) below.

| mayre-the | kowinnmaun=hnint | kobasoe-dot | |

| Mary-sbjmark | Ko.Win.Mg=and.conj | Ko.Ba.Soe-plmark(gen) | |

| Ag | Af[[Cir: Pl | ||

| bagan-htethot | |||

| plate-into.all | |||

| htaminn | htetpaye:-yan | bwain-arr | sauntyethnyunpyasaykhainn-nay-the. |

| rice | put-inf | boy-objmark | instruct-prog-decl.sentsuf |

| Af | Pro | Ag]] | Pro |

| ‘Mary is instructing the boy to put the rice into the plates of Ko Win Mg and Ko Ba Soe.’ | |||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 106) | |||

| maunlueaye:=le | mamyathann-arr | ||

| Mg.Lu.Aye[nom.m.sg]=addconn | Ma.Mya.Than-objmark | ||

| Ag | Af[[Ag | ||

| thalungalaye:-portwin | |||

| bed-on.loc | |||

| Cir: Pl | |||

| mimi-hnintatue | laryauk | htain-yan | khor-i. |

| 1sg-together.with.com | come | sit-inf | invite.prs-decl.sentsuf |

| Cir: Acc | Pro]] | Pro | |

| ‘Mg Lu Aye invites Ma Mya Than to come and sit with him on the bed.’ | |||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 29) | |||

3.1.3 Autonomous creating action process

He (forthcoming) asserts that our direct experience of creating in the physical and the social world is construed by autonomous creating action processes which may include one or two PRs. If there is only one PR in the creating process, it is the Created as shown in example (13). If two PRs exist in the process, they are the Agent and the Created, as shown in example (14).

| minnbue:nayyauncheswanninthonndatarrpaye:setyon-go | |

| Minbu.Solar.Power.Plant-objmark | |

| Cre | |

| akaunahtephor | tesauk-lyetshi-bar-the. |

| implement | build-prog-polmark-decl.sentsuf |

| Pro | |

| ‘The Minbu Solar Power Plant is being implemented.’ | |

| (Myanma Alinn Daily Newspaper 2019: 3)[1] | |

| mayre-hmar | hinnkhatmasalar-go-bin | kodain-phor-the. |

| Mary-sbjmark | spices-objmark-empmark | refl-make.prs-decl.sentsuf |

| Ag | Cre | Pro |

| ‘Mary makes spices herself.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 117) | ||

Influential creating action processes are the processes where creations in the physical and the social world are influenced by our experience of entities or events (He, forthcoming). They consist of an additional PR, the Agent that brings about a creating action process, as shown in examples (15) and (16) below.

| mayre-the | yarthealaik | pannmyoeson |

| Mary-sbjmark | seasonal | a.variety.of.flower |

| Ag | Af[[Cre- | |

| hinntheehinnywetmyoeson-dot | saikpyoe-zay-the. | |

| a.variety.of.vegetable-plmark | grow-caus.prs-decl.sentsuf | |

| Pro]] | ||

| ‘Mary makes the gardener grow a variety of seasonal flowers and vegetables.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 159) | ||

| htaminnchet-go | acheinme | sarrpwe | pyin-nain-yan | |

| cook-objmark | in.time | table | make-capamod-inf | |

| (Ag) | Af[[Ag | Cir | Cre | Pro]] |

| kyatmathnoesor-nay-ya-the. | ||||

| instruct-prog-oblg-decl.sentsuf | ||||

| Pro | ||||

| ‘Mary is instructing the cook to be able to make the table in time.’ | ||||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 105) | ||||

3.1.4 Autonomous behaving action process

He (forthcoming) states that our direct experience of activities out of the physiological and psychological needs in the physical world is identified by autonomous behaving action processes which may contain one or two PRs. If there is one PR, it is the Behaver as shown in example (17). If there are two PRs, they are the Behaver and the Range functioning as an independent entity to extend the meaning of the process, as shown in example (18).

| maunlueaye:=le | pyonn-lyetnaylay-the. |

| Mg.Lu.Aye[nom.m.sg]=addconn | smile-prog-decl.sentsuf |

| Behr | Pro |

| ‘Mg Lu Aye is smiling.’ | |

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 63) | |

| thue-the | thu-maye:-go | let-hnint |

| he.3sg-sbjmark | his.gen.3sg-chin-objmark | hand-with.ins |

| Behr | Ra | Cir: Ins |

| put-nay-the. | ||

| rub-prog-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘He is rubbing his chin with his hand.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 75) | ||

Influential behaving action processes are the processes where activities out of the physiological and psychological needs in the physical world are influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). They consist of an additional PR, the Agent that brings about a behaving action process, as shown in example (19) below.

| kyaukmetphweyar | athan-gyee-ga | mayre-go |

| frightening | sound-big.mod-sbjmark | Mary-objmark |

| Ag | Af[[Behr | |

| tonye-zay-khet-the. | ||

| shiver-caus-pst-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro]] | ||

| ‘Frightening sound made Mary shiver.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 189) | ||

3.2 Autonomous and influential mental processes

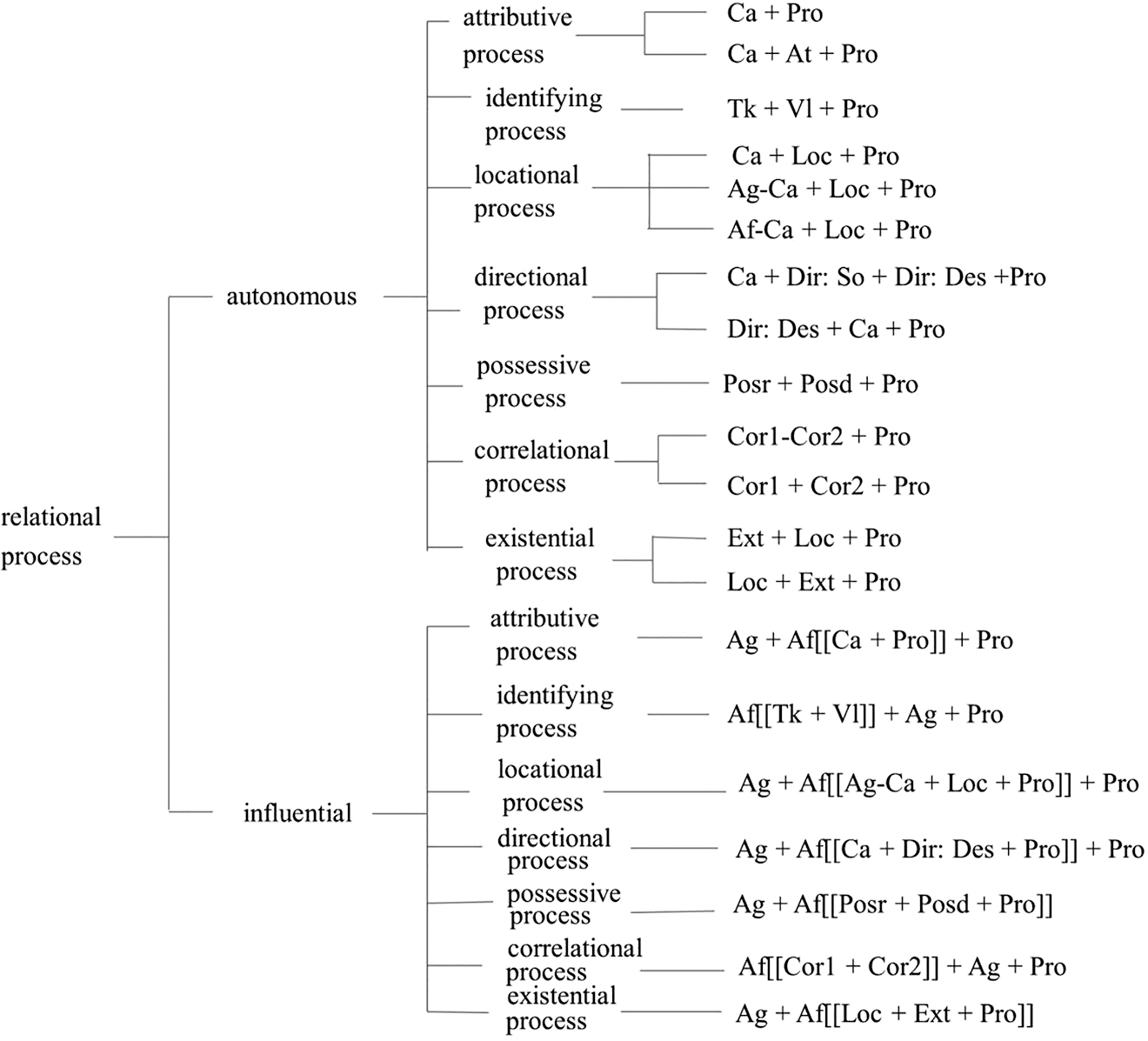

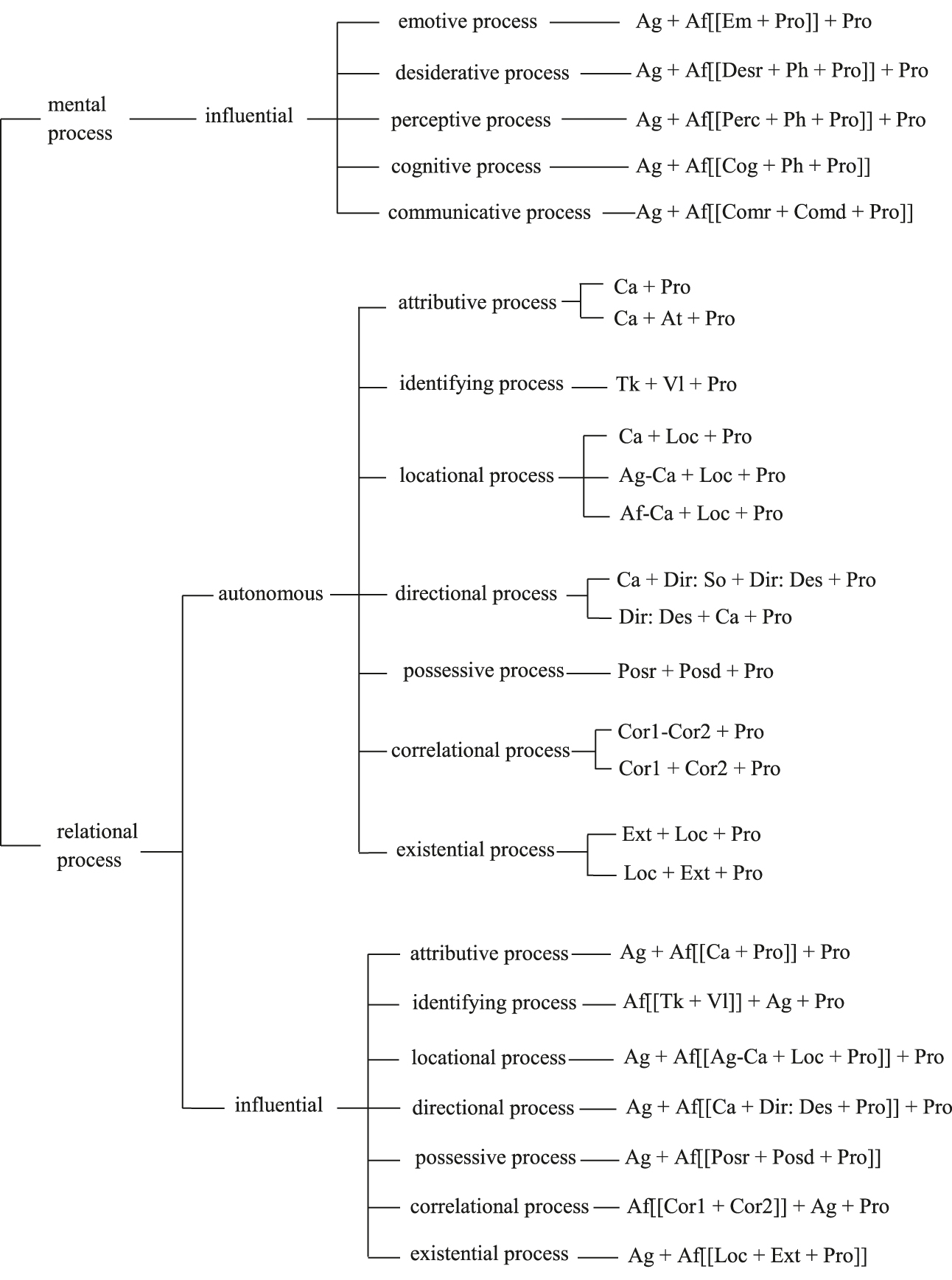

According to He (forthcoming), autonomous and influential mental processes are classified into five subtypes: emotive, desiderative, perceptive, cognitive, and communicative. A network of major participant role configurations in autonomous and influential mental processes is identified as in Figure 2.

Major options of participant role configurations in mental processes.

3.2.1 Autonomous emotive mental process

According to He (forthcoming), our direct experience of inner feelings and emotions is characterized by autonomous emotive mental processes which may consist of one or two PRs. The primary PR in a mental process is the Emoter which is generally a conscious being as shown in example (20). If there are two PRs, one is the Emoter and another is the Phenomenon as shown in example (21).

| maunlueaye:-the | hteikywaytthwarr-i. |

| Mg.Lu.Aye-sbjmark | shocked.pfv-decl.sentsuf |

| Em | Pro |

| ‘Mg Lu Aye was shocked.’ | |

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 26) | |

| mayre-hmar | sarrzayeik | tetkar | akonakya | pomyarrlar-hmar-go |

| Mary-sbjmark | food.price | rising | expense | become.more-fut-objmark |

| Em | Ph | |||

| kyeikywayt | puebin-thwarr-the. | |||

| secretly | worried-pfv-decl.sentsuf | |||

| Cir | Pro | |||

| ‘Mary was secretly worried about becoming more expense as food prices rise.’ | ||||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 160) | ||||

Influential emotive mental processes are the processes where emotions in the human mind are influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). They consist of an additional PR, the Agent that causes an emotive mental process, as shown in example (22) below.

| thetthet-ga | hla-arr | ma-kyauk-yan | ahtethtet |

| Thet.Thet-sbjmark | Hla-objmark | neg-fear-inf | repeatedly |

| Ag | Af[[Em | Pro]] | Cir |

| arrpaye:-ya-the. | |||

| encourage.prs-oblg-decl.sentsuf | |||

| Pro | |||

| ‘Thet Thet has to repeatedly encourage Hla not to fear.’ | |||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 17) | |||

3.2.2 Autonomous desiderative mental process

He (forthcoming) defines that our direct experience of actions that come out of our desires in the mental world is represented by autonomous desiderative mental processes consisting of two main PRs, the Desiderator and the Phenomenon, as shown in examples (23) and (24).

| maunlueaye:-the | khetngengegabin | luebyogyee | loke-naymye=hu |

| Mg.Lu.Aye-sbjmark | in.his.youth | bachelor | do-fut=that.comp |

| Desr | Cir: TP | Ph | |

| sonnphyathtarr-khet-i. | |||

| decide-pst-decl.sentsuf | |||

| Pro | |||

| ‘Mg Lu Aye decided to be a bachelor in his youth.’ | |||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 23) | |||

| ethot | tayaukhte | einathonnasaun-anenge-hmya |

| ana | alone | furniture-a.little.det-only.excl |

| Pheno- | ||

| asaykhan-ta-yauk-hna-yauk-hmya-hnint | ||

| servant-one-clf-two-clf-only.excl-com | ||

| nayhtain-yathe-go | myethue | hnitthet-par-antnee? |

| live-oblg-objmark | who | like.prs-polmark-int.sentsuf |

| -menon | Desr | Pro |

| ‘Who likes to live only with a little furniture and one or two servants?’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 17) | ||

Influential desiderative mental processes are the processes where actions that come out of our desires in the mental world are influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). They consist of an additional PR, the Agent that causes a desiderative mental process, as shown in example (25) below.

| maunlueaye:-hmar | thu-seikkue:-go | mamyathann |

| Mg.Lu.Aye-sbjmark | his.gen.3sg-idea-objmark | Ma.Mya.Than |

| Ag | Af[[Ph | Desr |

| thabawkya-aun | taiktunn-ya-baymye. | |

| like-inf | urge-oblg-fut.decl.sentsuf | |

| Pro]] | Pro | |

| ‘Mg Lu Aye will have to urge Ma Mya Than to like his idea.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 24) | ||

3.2.3 Autonomous perceptive mental process

He (forthcoming) states that our direct experience of actions coming out of our perception in the mental world is represented by autonomous perceptive mental processes. These processes involve two PRs, the Perceiver and the Phenomenon, as shown in example (26) below.

| maunlueaye:-garr | bargohmya | ma-myin. |

| Mg.Lu.Aye-sbjmark | anything | neg-see.prs |

| Perc | Ph | Pro |

| ‘Mg Lu Aye does not see anything.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 27) | ||

Influential perceptive mental processes are the processes where actions that come out of our perception in the mental world are influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). They consist of an additional PR, the Agent that brings forth a perceptive mental process, as shown in example (27) below.

| ue:minnhan-the | mayre-arr | aporhtet-go | kyi | khwintpyu-laiklay-the. |

| U.Min.Han-sbjmark | Mary-dat | upstairs-acc | see | let-pfv-decl.sentsuf |

| Ag | Af[[Perc | Ph | Pro]] | Pro |

| ‘U Min Han let Mary see upstairs.’ | ||||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 91) | ||||

3.2.4 Autonomous cognitive mental process

He (forthcoming) affirms that our direct experience of actions coming out of our cognition and thoughts in the mental world is identified by autonomous cognitive mental processes. These processes usually consist of two main PRs, the Cognizant and the Phenomenon, as shown in example (28) below.

| maunlueaye:=le | behmarhtainyahmann | ma-thi. |

| Mg.Lu.Aye[nom.m.sg]=addconn | where.to.sit | neg-know.prs |

| Cog | Ph | Pro |

| ‘Mg Lu Aye does not know where to sit.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 27) | ||

The autonomous cognitive mental process can also be conflated with another process, the autonomous doing action process, as shown in example (29) below. This compound process, which is known as the autonomous doing action and cognitive mental process, consists of two PRs. One is a compound PR, the Agent-Cognizant, which takes the roles of two participants by initiating the thinking, knowing or understanding process, and the other is a simple PR, the Phenomenon.

| dutiyathamada-ga | thelawarahtue:seepwarryaye:zon-i |

| Vice.President-sbjmark | Thilawa.Special.Economic.Zone-gen |

| Ag-Cog | Ph |

| aseyinkhanzar-go | laytlarkyi-the. |

| report-objmark | study.prs-decl.sentsuf |

| Pro | |

| ‘The Vice President studies Thilawa Special Economic Zone’s report.’ | |

| (Myanma Alinn Daily Newspaper 2019: 7)[2] | |

Influential cognitive mental processes are the processes where actions coming out of our cognition and thoughts in the mental world are influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). They consist of an additional PR, the Agent that brings forth a cognitive mental process, as shown in example (30) below.

| thuema-i | mahmyorlintbeahmatmahtin | athwinapyinpyaunnnaythaw |

| she-gen | unexpectedly | changed |

| Ag | ||

| thadan-the | ue:minnhan-arr | mayre-hma |

| appearance-sbjmark | U.Min.Han-objmark | Mary-empmark |

| Af[[Cog | Ph | |

| hokeyetlarr=hu | yoketayet | htinhmatmi-zay-the. |

| whether.or.not=that.comp | suddenly | consider-caus.prs-decl.sentsuf |

| Cir | Pro]] | |

| ‘Her unexpectedly changed appearance suddenly makes U Min Han consider whether she is Mary or not.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 136) | ||

3.2.5 Autonomous communicative mental process

He (forthcoming) claims that our direct experience of exchanging information through language is construed by autonomous communicative mental processes including two or three PRs. The three major PRs that may involve in the communicative process are the Communicator, the Communicated, and the Communicatee. Examples (31) to (34) illustrate the semantic configurations of autonomous communicative mental processes.

| dedort | thu-atwinnwin-ga | rose-go |

| then.conn | his.gen.3sg -secretary- sbjmark | Rosy-objmark |

| Comr | Comee | |

| pyaw-de. | ||

| tell.prs-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘Then his secretary tells Rosy.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 52) | ||

| lagaunndot-ga-thar | zagarrpyaw-nay-gya-i. |

| they.3PL-sbjmark-only.excl | talk-prog-plmark-decl.sentsuf |

| Comr-Comee | Pro |

| ‘Only they are talking.’ | |

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 28) | |

| dagahmue:-ga | tangarthe-arr | “thin | yashi=thaw |

| chamberlain-sbjmark | fisherman-objmark | you[nom.2sg] | get=rel |

| Comr | Comee | Com- | |

| sulet-i | tawet-go | kyanoke-arr | paye:=hmathar |

| reward-gen | half-acc | 1sg-dat | give=only.if.conj |

| -muni- | |||

| thint-go | nannsaun-htethot | win-khwintpyu-mye”=hu | |

| you.2sg-objmark | palace-into.all | enter-let-fut=that.comp | |

| -cated | |||

| so-i. | |||

| say(pst)-decl.sentsuf | |||

| Pro | |||

| ‘The Chamberlain said to the fisherman, “I will let you in only if you give me half of your reward.”’ | |||

| (Maung Htin Aung 1962: 103) | |||

| shaye:ue:swar | dutiyathamada-arr | thelawarahtue:seepwarryaye:zon |

| firstly.conn | Vice.President-dat | Thilawa.Special.Economic.Zone |

| Comee | Cir: Pl | |

| shinnlinnsaun-hnaik | ahtue:seepwarryaye:zon | baholokengannaphwet |

| briefing.hall-in.loc | Special.Economic.Zone | Executive.Working.Group |

| Commu- | ||

| okekahta, | seepwarryaye:=hnint | kue:thannyaunnweyaye: |

| chairman | commerce=and.conj | trade |

| -nicator | ||

| wungyeehtarna | pyehtaunsuwungyee | dauktarthannmyint-ga |

| ministry | Union.Minister | Dr.Than.Myint-sbjmark |

| ahtue:seepwarryaye:zon | semangeinn-myarr | saunywet-lyetshi=thi |

| Special.Economic.Zone | project-plmark | carry.out-prog=rel |

| Comd | ||

| achayanay-go | shinnlinn | tinpya-the. |

| situation-objmark | explain | report.prs-decl.sentsuf |

| Pro | ||

| ‘The Vice President is first briefed by the Chairman of the Executive Working Group, who is Union Minister for Commerce, Dr. Than Myint, on the progress of the Thilawa Special Economic Zone’s various projects in the briefing hall.’ | ||

| (Myanma Alinn Daily Newspaper 2019: 7)[3] | ||

Influential communicative mental processes are the processes where interactions are influenced by our experience of events (He forthcoming). They consist of an additional PR, the Agent that gives rise to a communicative mental process, as shown in example (35) below.

| thetthet-ga | ue:gyee-go | thuedot-dadway-yet | nanme-dway-go |

| Thet.Thet-nom | U.Gyi-dat | they.3pl-assoc-gen | name-plmark-acc |

| Ag | Af[[Comr | Comd | |

| htokephor | ma-pyaw-zay-chin-bue: | ||

| reveal | neg-tell.prs-caus-opt-negdecl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro]] | |||

| ‘Thet Thet wants U Gyi not to reveal their names.’ | |||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 41) | |||

3.3 Autonomous and influential relational processes

In accordance with He (forthcoming), autonomous and influential relational processes are divided into seven subtypes: autonomous and influential attributive, identifying, locational, directional, possessive, correlational, and existential relational processes. A network consisting of major participant role configurations in autonomous and influential relational processes is developed as in Figure 3.

Major options of participant role configurations in relational processes.

3.3.1 Autonomous attributive relational process

He (forthcoming) states that our direct experience of attributing features or members to their units is represented by autonomous attributive relational processes. These processes may consist of one or two PRs. If there is one PR, it is the Carrier whose feature is expressed in the Process element, as shown in example (36). If there are two PRs, one is the Carrier and the other is the Attribute, as shown in example (37).

| thahtaye: | ue:kywe-i | thamee | mahlatin-hmar |

| rich.man | U.Kyawe-gen | daughter | Ma.Hla.Tin-sbjmark |

| Ca | |||

| yokelechaw | thabawlekaunn | apyawlepar-i. | |

| beautiful | good-natured | good.at.speaking.prs-decl.sentsuf | |

| Pro | |||

| ‘Ma Hla Tin, the daughter of a rich man, U Kyawe, is beautiful, good-natured and good at speaking.’ | |||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 21) | |||

| khinthannmyint-galaye:-garr | athet | hnase-khant-thar |

| Khin.than.myint-affmark-sbjmark | age | 20-about-only.excl |

| Ca | At | |

| shi-thaye:-i. | ||

| cop-prs-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘Khin Than Myint is only about 20 years old.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 58) | ||

Influential attributive relational processes are the processes where attributing features or members to their units are influenced by our experience of events (He, forthcoming). They contain an additional PR, the Agent that gives rise to an attributive relational process, as shown in example (38) below.

| etkhann-go | hlapa-aun | |

| living.room-objmark | beautiful-inf | |

| (Ag) | Af[[Ca | Pro]] |

| munnmanpyinsin-gya-the. | ||

| decorate.prs-plmark-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘The living room is decorated.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 109) | ||

3.3.2 Autonomous identifying relational process

He (forthcoming) asserts that autonomous identifying relational processes construe our direct experience of representing entities or events as members of a class through their tokens or values. The two main PRs involved in these processes are the Token and the Value as shown in example (39) below.

| tayokepye=net | myanmarpye-har | arshanainngan-dway |

| China=and.conj | Myanmar-sbjmark | Asian.country-plmark |

| Tk | Vl | |

| phyit-kya-bar-de. | ||

| cop.prs-plmark-polmark-postdecl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘China and Myanmar are Asian countries.’ | ||

| (Zhao 2011: 40) | ||

Influential identifying relational processes are the processes where the identification of entities as members of a class through their tokens or values is influenced by our experience of events (He forthcoming). They include an additional PR, the Agent that brings about an identifying relational process as shown in example (40) below.

| asaykhan-yelotmyarrdort | kyanaw-gaasa | taeinlonn-ga | |

| servant-appel | 1sg.m-incl | all-sbjmark | |

| Af [[(Tk) | Vl]] | Ag | |

| thabaw<ma>htarr-bar-bue:. | |||

| regard.prs<neg>-polmark-negdecl.sentsuf | |||

| Pro | |||

| ‘All including me don’t regard you as a servant.’ | |||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 73) | |||

3.3.3 Autonomous locational relational process

He (forthcoming) claims that autonomous locational relational processes construe our direct experience of the connection between one entity and its location. They usually consist of two PRs, the Carrier and the Location as shown in example (41) below.

| myanmarpye-har | tayokepye-yet | anauktaunphet-hmar |

| Myanmar-sbjmark | China-gen | southwest-loc |

| Ca | Loc | |

| teshi-bar-de. | ||

| exist.prs-polmark-postdecl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘Myanmar is situated to the southwest of China.’ | ||

| (Zhao 2011: 40) | ||

The autonomous locational relational process can be conflated with another process, the autonomous doing action process. This compound process is known as the autonomous doing action and locational relational process. It consists of two PRs. One is a compound PR which takes the roles of two participants, the Agent or the Affected and the Carrier; and the other is a simple PR, the Location. See examples (42) and (43) below.

| mimi | ingalanpye | auk(s)phot | myot-twin | tayaukhte |

| 1sg.nom | England | Oxford | town-in.loc | alone |

| Ag-Ca | Loc | Cir | ||

| thwarryauk | nayhtain-khet-phue:-i. | |||

| go | stay-pst-exper-decl.sentsuf | |||

| Pro | ||||

| ‘I stayed alone in Oxford, England.’ | ||||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 46) | ||||

| atankyarhlyin | mawtawkarr-dot=le | mamyathann-dot |

| after.some.time | car-plmark=addconn | Ma.Mya.Than-plmark(gen) |

| Cir: TP | Af-Ca | Loc |

| ein-shayttwin | saik-kya-gon-i. | |

| house-in.front.of.LOC | reach-plmark-pfv-decl.sentsuf | |

| Pro | ||

| ‘After some time, the cars reached in front of Ma Mya Than’s house.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 25) | ||

As shown in example (42) above, the Agent-Carrier serves as a compound PR in such a way that the Agent itself performs the static action of staying and remains in a certain place for a period of time as a result of the action. Similarly, the Affected-Carrier in example (43) also functions as a compound PR in such a way that the Carrier is affected by someone to be in a certain location.

Influential locational relational processes are the processes where the connection between one entity and its location is influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). They include an additional PR, the Agent that brings forth a locational relational process, as shown in example (44) below.

| maunlueaye:-the | etthe-myarr-go | mimi | ein-twin |

| Mg.Lu.Aye-sbjmark | guest-plmark-objmark | 1sg(gen) | house-loc |

| Ag | Af[[Ag-Ca | Loc | |

| tanya | tekho | khwintpyu-laik-i. | |

| one.night | stay | let-pfv-decl.sentsuf | |

| Cir | Pro]] | Pro | |

| ‘Mg Lu Aye let the guests stay in his house for one night.’ | |||

| (http://sealang.net/burmese/bitext.htm) | |||

3.3.4 Autonomous directional relational process

He (forthcoming) states that autonomous directional relational processes identify our direct experience of events that are related to their directions: Source, Path, and Destination. These processes contain two PRs: The Carrier and the Direction as shown in examples (45) and (46) below.

| bagan-har | myanmaamwayahnit-ganay | gabhaamwayahnit-go |

| Bagan-sbjmark | Myanmar.heritage-from.ablmark | world.heritage-all |

| Ca | Dir: So | Dir: Des |

| tethlann-thwarr-nain-bye. | ||

| step.up-pfv-capamod-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘Bagan has been able to step up from a national heritage to a world heritage.’ | ||

| (Myanma Alinn Daily Newspaper 2019: 5)[4] | ||

| maunlueaye:-thot=le | thannwaychinn | yawgar |

| Mg.Lu.Aye-all=addconn | yawning | disease |

| Dir: Des | Ca | |

| kue:setpyantpwarr-i. | ||

| spread.prs-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘Yawning spreads to Mg Lu Aye.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 28) | ||

Influential directional relational processes are the processes where the relation between one entity and its direction: Source, Path, or Destination is influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). They involve an additional PR, the Agent that causes a directional relational process, as shown in example (47) below.

| ue:minnhan-the | einthotapyan | thu-karr-go | |

| U.Min.Han-sbjmark | on.the.way.home | his.gen.3sg-car-objmark | |

| Ag | Cir | Af[[Ca | |

| yeye-dot | ein-betthot | kwayt | maunn-larlay-the. |

| Yee.Yee-plmark(gen) | house-towards.all | turn | drive-prs-decl.sentsuf |

| Dir: Des | Pro]] | Pro | |

| ‘On the way home, U Min Han drives his car to Yee Yee’s house.’ | |||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 82) | |||

3.3.5 Autonomous possessive relational process

According to He (forthcoming), autonomous possessive relational processes represent our experience of relation between entities and their possessors. They consist of two primary PRs, the Possessor and the Possessed, as shown in example (48).

| khayeethwarrlokengann | myinttet=lardarnetahmya | ||

| tourism | develop=as.long.as.conj | ||

| Af | Pro | ||

| ‘As long as tourism develops …’ | |||

| daythakhanpyethue-dway | alokeakain | akhwintalann-dway | ya-larme. |

| local.resident-plmark | job | prospect-plmark | get-fut.decl.sentsuf |

| Posr | Posd | Pro | |

| ‘…the local residents will get job prospects.’ | |||

| (Myanma Alinn Daily Newspaper 2019: 5)[5] | |||

Influential possessive relational processes are the processes where the relation between entities and their possessors is influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). They contain an additional PR, the Agent that brings about a possessive relational process, as shown in example (49) below.

| khayeethwarrlokengann | toetetlarhmu-the | |

| tourism | development-sbjmark | |

| Ag | ||

| daythakhanpyethue-dway-go | alokeakain | akhwintalann-dway |

| local.resident-plmark-objmark | job | prospect-plmark |

| Af[[Posr | Posd | |

| ya-zay-de. | ||

| get-caus.prs-postdecl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro]] | ||

| ‘The development of tourism makes the local residents get job prospects.’ | ||

| (Myanma Alinn Daily Newspaper 2019: 5)[6] | ||

3.3.6 Autonomous correlational relational process

He (forthcoming) affirms that our direct experience of relation between two entities or events is characterized by autonomous correlational relational processes containing two PRs, the Correlator1 and the Correlator2, as shown in examples (50) and (51) below.

| hnanainngan | pyethue-dway-har | swaymyoepaukphor-lo |

| two.country | the.People-plmark-sbjmark | kin-like.cmpr |

| Cor1-Cor2 | Cir | |

| khinminyinnhnee-gya-bar-de. | ||

| friendly-plmark-polmark-postdecl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘The people from two countries have close friendship like kin.’ | ||

| (Zhao 2011: 40) | ||

| ue:minnhan-the | yeye-hnint | saytzat-htarr-the. |

| U.Min.Han-sbjmark | Yee.Yee-with.com | engaged-pfv-decl.sentsuf |

| Cor1 | Cor2 | Pro |

| ‘U Min Han has been engaged with Yee Yee.’ | ||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 81) | ||

Influential correlational relational processes are the processes where our experience of entities or events influences the relation between two entities or two people (He forthcoming). They consist of an additional PR, the Agent that gives rise to a correlational relational process, as shown in example (52) below.

| tayoke | myanmar | meikswayphyitsetsanyaye:-go |

| China | Myanmar | friendly.relationship-objmark |

| Af[[Cor1 | Cor2]] | |

| hnanainngan | gaunnsaun-dway-kodain | |

| two.country | leader-plmark-refl | |

| Ag | ||

| pyuzupyoehtaun-gya-bar-de. | ||

| develop-plmark-polmark-postdecl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘The leaders of the two countries develop themselves the friendly relationship between China and Myanmar.’ | ||

| (Zhao 2011: 41) | ||

3.3.7 Autonomous existential relational process

He (forthcoming) states that our direct experience of spatial or temporal locations related to existents is construed by autonomous existential relational processes including two common PRs, the Location and the Existent, as shown in examples (53) and (54) below.

| maunlueaye:=hnint | mamyathann-dot-tharhlyin | akhann-htehnaik |

| Mg.Lu.Aye=and.conj | Ma.Mya.Than-plmark-only.excl | room-in.loc |

| Ext | Loc | |

| kyan-dort-i. | ||

| remain-prs-decl.sentsuf | ||

| Pro | ||

| ‘Only Mg Lu Aye and Ma Mya Than remain in the room.’ | ||

| (Science Mg Wa 1998: 29) | ||

| ein-i | myethnazar-twin | myetkhinngyee | shi-i. |

| house-gen | front-loc | lawn | exist.prs-decl.sentsuf |

| Loc | Ext | Pro | |

| ‘There is a lawn at the front of the house.’ | |||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 68) | |||

Influential existential relational processes are the processes where spatial or temporal locations relating to existents are influenced by our experience of entities or events (He forthcoming). They include an additional PR, the Agent that causes an existential relational process, as shown in example (55) below.

| mayre-the | satokhann-htehnaik | sanoe | seoe-sathi |

| Mary-sbjmark | storeroom-in.loc | pot.of.rice | pot.of.oil-etc. |

| Ag | Af[[Loc | Exist- | |

| einthonnsarrkonthaukkon-myarr | thohlaunhtarr-zay-the. | ||

| grocery-plmark | store-caus.prs-decl.sentsuf | ||

| -ent | Pro]] | ||

| ‘Mary has groceries such as pot of rice and pot of oil stored in the storeroom.’ | |||

| (Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay 1957: 116) | |||

Based on He’s (forthcoming) new model of the transitivity system of Chinese, the present study has attempted to construct a comprehensive transitivity system of Myanmar and present a system network of transitivity system of Myanmar, as shown by Figure 4.

A system network of transitivity system of Myanmar.

4 Discussion

He (forthcoming) recognizes more types of processes and participant roles including compound processes and compound PRs than Halliday (1985, 1994 and Halliday and Matthiessen (2004, 2014. Based on the findings of the transitivity analysis of the selected text by the adoption of Halliday’s (1985) model and He’s (forthcoming) new model of transitivity, the following presents the contrastive study between these two models from the perspective of the classification of process types, participant roles, and circumstances.

As illustrated by Table 2, “with everyone” cannot be classified as any existing participant role in Halliday’s intensive attributive relational process, whereas it can be classified as the Correlator2 in terms of He’s (forthcoming) autonomous correlational relational process. Thus, He (forthcoming) goes further to categorize participant roles.

Comparison between the two transitivity analyses of a relational clause in terms of Halliday’s (1985) model and He’s (forthcoming) new model.

| mauntinmaun-hmar | thuedagar-hnint=le | mathintmatintphyit-i. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg.Tin.Mg-sbjmark | everyone-com=addconn | be.on.bad.terms.prs-decl.sentsuf | |

| Halliday (1985) | Carrier | Process: rel, attri, intensive | |

| He (forthcoming) | Correlator1 | Correlator2 | Process: autonomous correlational relational |

-

‘Mg Tin Mg is on bad terms with everyone.’ (Science Mg Wa 1998: 21).

As suggested by Table 3, “I had stayed alone in Oxford, England” is categorized as a material process comprising only one participant, the Actor, “I” by means of Halliday (1985), while it is categorized as a compound process, the autonomous doing action and locational relational process, by virtue of He’s (forthcoming) model. In the configuration of this compound process, “I” is taken as a compound PR, the Agent-Carrier which takes the roles of two participants, the Agent and the Carrier in such a way that the Agent itself performs the action of staying and achieves a certain attribute of remaining in a certain place for a period of time as a result of the action. This makes it clear that He’s (forthcoming) classifications of process types and participant roles are more delicate than Halliday’s (1985). Besides simple PRs, compound PRs are identified in her compound processes. Furthermore, “in Oxford, England” is classified as a participant, the Location by He (forthcoming), whereas it is taken as a Circumstance by Halliday (1985). Classifying this element as the participant instead of the Circumstance is more reasonable because the clause sounds odd if it is omitted. Therefore, He (forthcoming) goes further to distinguish participant roles from circumstances. See also Table 4 below as another example that shows He’s (forthcoming) more specific classification of process types and differentiation between participant roles and circumstances than Halliday’s.

Comparison between the two transitivity analyses of a material clause in terms of Halliday’s (1985) model and He’s (forthcoming) new model.

| mimi | ingalanpye | auk(s)phot | myot-twin | tayaukhte | thwarryauk | nayhtain-khet-phue:-i. | |

| 1sg.nom | England | Oxford | town-loc | alone | go | stay-pst-exper-decl.sentsuf |

| Halliday (1985) | Actor | Circumstance | Circumstance | Process: material |

| He (forthcoming) | Agent-Carrier | Location | Circumstance | Compound process: autonomous doing action and locational relational |

-

‘I had stayed alone in Oxford, England.’ (Science Mg Wa 1998: 46)

Comparison between the two transitivity analyses of a material clause in terms of Halliday’s (1985) model and He’s (forthcoming) new model.

| maunlueaye:-the | ein-thot | hmaun-hma | pyanyauk-i. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg.Lu.Aye-sbjmark | home-all | dark-ablmark | arrive.prs-decl.sentsuf | |

| Halliday (1985) | Actor | Circumstance | Circumstance | Process: material |

| He (forthcoming) | Agent-Carrier | Direction: destination | Circumstance | Process: autonomous doing action and directional relational |

-

‘Mg Lu Aye arrives home when it is dark.’ (Science Mg Wa 1998: 18).

As demonstrated by Table 4, the Myanmar clause “Mg Lu Aye arrives home when it is dark” is categorized as a material process consisting of only one participant, i.e. the Actor, “Mg Lu Aye” by means of Halliday’s (1985) model. On the other hand, in terms of He’s (forthcoming) new model of transitivity system of Chinese, this clause is classified as a compound process, i.e. the autonomous doing action and directional relational process in which “Mg Lu Aye” is taken as a compound PR, namely the Agent-Carrier which takes the roles of two participants, the Agent and the Carrier in such a way that the Agent itself performs the action of returning home and achieves a certain attribute of arriving home as a result of the action. This shows that He’s (forthcoming) classifications of process types and participant roles are more detailed and convincing than Halliday’s (1985). Moreover, “to home” is an essential constituent of the clause to make meaning. Therefore, following He’s (forthcoming) new model, it should be taken as a participant, the Direction: Destination rather than a Circumstance.

As represented by Table 5, it is more reasonable and acceptable to categorize “the whole surface of the water” as the Affected rather than the Actor because it is not the doer of the action but is affected by the moonlight to bring about the process of shining. He’s (forthcoming) categorization of participant roles is, therefore, more concrete than Halliday’s.

Comparison between the two transitivity analyses of a material clause in terms of Halliday’s (1985) model and He’s (forthcoming) new model.

| amyemapyat | seesinn-lyetnay=thaw | ayyarwademyit-porthot | layaun | kya-lyetnay=thawgyaunt | ||

| continuously | flow-prog=rel | Ayeyarwaddy.River-onto.all | moonlight | fall-prog=as.conj | ||

| Halliday (1985) | Circumstance | Actor | Process: material | |||

| He (forthcoming) | Direction: Destination | Carrier | Process: autonomous directional relational | |||

| ‘As the moonlight has been falling onto the continuously flowing Ayeyarwaddy River…’ | ||||||

| myit-takhulonn | ayauntauk-lyetnaybay-i. | |||||

| river-whole | shine-prog-decl.sentsuf | |||||

| Halliday (1985) | Actor | Process: material | ||||

| He (forthcoming) | Affected | Process: autonomous happening action | ||||

-

‘…the whole surface of the water is shining.’ (Science Mg Wa 1998: 18–19).

With regard to the participant functions, as shown by Table 6, “face” cannot perform the action by itself for being an inanimate being but is affected by the covert animate being to perform the action of looking at the sky and achieve a certain attribute of remaining in an upright position as a result of the action. Therefore, classifying this element as a compound PR, the Affected-Carrier instead of the Actor is more feasible. Furthermore, “to the sky which is twinkling with stars” is an essential part for the completion of the meaning of the clause. Thus, this element should be taken as a participant rather than a Circumstance in the transitivity structure. With reference to He’s (forthcoming) new model, it is classified as a compound PR, the Affected-Direction: Affected-Destination of the compound process, the autonomous doing action and directional relational process. This makes it clear that He’s (forthcoming) categorization of process types and participant roles is much more convincing and workable than Halliday’s (1985).

Comparison between the two transitivity analyses of a material clause in terms of Halliday’s (1985) model and He’s (forthcoming) new model.

| myethnar-garr | kye-dwayason-phyint | htunnlinn-lyetnay=thaw | kaunnkin-thot | mort-nay-i. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| face-sbjmark | star-plmark-com | twinkle-prog=rel | sky-all | up-prog-decl.sentsuf | |

| Halliday (1985) | Actor | Circumstance | Process: material | ||

| He (forthcoming) | Affected-Carrier | Affected-Direction: Affected-Destination | Process: autonomous doing action and directional relational | ||

-

‘Face is up to the sky which is twinkling with stars.’ (Science Mg Wa 1998: 19).

As illustrated by Table 7, the Myanmar clause “Mg Lu Aye has thrown the newspaper onto the floor” is categorized as a material process by virtue of Halliday’s (1985) model. This process consists of two participants: the Actor, “Mg Lu Aye” and the Goal, “newspaper”. The prepositional phrase “onto the floor” is taken as a Circumstance. On the other hand, following He’s (forthcoming) new model of transitivity, this clause is classified as an autonomous doing action process comprising three participant roles: two simple PRs and one compound PR. “Mg Lu Aye” is regarded as the Agent. “Newspaper” is taken as a compound PR, the Affected-Carrier taking the roles of two participants: the Affected and the Carrier, while “onto the floor” is taken as the Direction: Destination because these two PRs are related to each other as a result of the action undertaken by the Agent. In these two configurations of processes, He (forthcoming) goes further to categorize participant roles than Halliday (1985). Results show that He’s (forthcoming) model is better than Halliday’s with regard to the modeling of the transitivity system of Myanmar.

Comparison between the two transitivity analyses of a material clause in terms of Halliday’s (1985) model and He’s (forthcoming) new model.

| maunlueaye:-the | thadinnsar-go | kyann-porthot | pyitcha-laik-i. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg.Lu.Aye-sbjmark | newspaper-objmark | floor-all | throw-pfv-decl.sentsuf | |

| Halliday (1985) | Actor | Goal | Circumstance | Process: material |

| He (forthcoming) | Agent | Affected-Carrier | Direction: Destination | Process: autonomous doing action |

-

‘Mg Lu Aye has thrown the newspaper onto the floor.’ (Science Mg Wa 1998: 19).

5 Conclusion

This study is conducted by constructing a comprehensive and systematic transitivity system of Myanmar with reference to autonomous and influential action, mental, and relational processes in He’s (forthcoming) new model of Chinese transitivity system. In section 2, previous descriptions of the transitivity systems of English, French, German, Japanese, Tagalog, Chinese, Vietnamese, Telugu, and Pitjantjatjara have been evaluated. They adopt an upward approach; consequently, they are not workable enough to construct a transitivity system of Myanmar which is applicable to the discourse analysis of Myanmar texts.

Unlike previous studies, He’s (forthcoming) new model of the Chinese transitivity system employs a downward approach which is effective to be applied to the discourse analysis of Myanmar texts. This new model is more concrete than Halliday’s (1985) English transitivity system in categorizing processes and participants as well as in differentiating participants from circumstances. Furthermore, it has been successfully applied to analyzing many Chinese texts. This paper, therefore, focuses on He’s (forthcoming) new description of Chinese transitivity to propose the Myanmar transitivity system. In section 3, Myanmar transitivity configurations of 32 processes, which are the representative categories of the Myanmar people’s experience of the world, have been demonstrated with authentic examples. Section 4 presents the contrastive study of the two transitivity analyses of the selected text by the adoption of Halliday’s (1985) model and He’s (forthcoming) new model. The result shows that the Myanmar transitivity system which is put forward in this paper has been proved to be feasible by being applied to analyzing many Myanmar texts.

The present model of the Myanmar transitivity system is a pioneering work in the history of transitivity studies in Myanmar and it is significantly applicable and effective in the discourse analysis of Myanmar texts. This study has clear implications for further research on the systemic functional grammar of Myanmar. So far, there has been no systemic functional study of Myanmar in literature. Thus, further research is clearly necessary in this area.

Abbreviations

- Special abbreviations

- Af

-

Affected

- Af-Ca

-

Affected-Carrier

- Af-Posd

-

Affected-Possessed

- Af-Posr

-

Affected-Possessor

- Ag

-

Agent

- Ag-Ca

-

Agent-Carrier

- Ag-Cog

-

Agent-Cognizant

- At

-

Attribute

- Behr

-

Behaver

- Ca

-

Carrier

- Cir

-

Circumstance

- Cir: Pl

-

Circumstance: Place

- Cir: TP

-

Circumstance: Time position

- Cog

-

Cognizant

- Comd

-

Communicated

- Comee

-

Communicatee

- Comr

-

Communicator

- Cor1

-

Correlator1

- Cor2

-

Correlator2

- Cre

-

Created

- Des

-

Destination

- Desr

-

Desiderator

- Dir

-

Direction

- Em

-

Emoter

- Ext

-

Existent

- Loc

-

Location

- Perc

-

Perceiver

- Ph

-

Phenomenon

- Posr

-

Possessor

- Posd

-

Possessed

- PR

-

Participant Role

- Pro

-

Process

- Ra

-

Range

- So

-

Source

- Tk

-

Token

- Vl

-

Value

- Abbreviations also found in the Leipzig Glossing Rules

- 3pl

-

third person plural

- 1sg

-

first person singular

- 2sg

-

second person singular

- 3sg

-

third person singular

- ablmark

-

ablative marker

- acc

-

accusative

- addconn

-

additive connective

- affmark

-

affectionate marker

- all

-

allative

- ana

-

anaphoric

- appel

-

appellative

- assoc

-

associative

- capamod

-

capability modality

- caus

-

causative

- clf

-

classifier

- cmpr

-

comparative

- com

-

comitative

- comp

-

complementizer

- compa

-

compassion

- conj

-

conjunction

- conn

-

connective

- cop

-

copula

- dat

-

dative

- decl.sentsuf

-

declarative sentence suffix

- det

-

determiner

- dim

-

diminutive

- du

-

dual

- empmark

-

emphatic marker

- excl

-

exclusive

- exper

-

experiential

- f

-

female

- fut

-

future

- gen

-

genitive

- incl

-

inclusive

- inf

-

infinitive

- ins

-

instrumental

- int.sentsuf

-

interrogative sentence suffix

- loc

-

locative

- m

-

male

- mod

-

modifier

- neg

-

negative

- negdecl.sentsuf

-

negative declarative sentence suffix

- nom

-

nominative

- objmark

-

object marker

- oblg

-

obligation

- opt

-

optative

- pfv

-

perfective

- plmark

-

plural marker

- polmark

-

polite marker

- postdecl.sentsuf

-

positive declarative sentence suffix

- prog

-

progressive

- prs

-

present

- pst

-

past

- purp

-

purposive

- refl

-

reflexive

- rel

-

relative

- sbjmark

-

subject marker

- sup

-

superlative

Funding source: Beijing Foreign Studies University

Award Identifier / Grant number: 19ZDA319

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my special thanks to my supervisor, Professor He Wei who gave me full guidance on the accomplishment of this paper.

-

Research funding: This study is funded by Major Program of National Social Science Fund of China: Database Construction of Language Resources of Those Countries along the Belt and Road and Contrastive Studies between Chinese and Foreign Languages (grant number 19ZDA319).

References

Caffarel, Alice, James Robert Martin & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen (eds.). 2004. Language typology: A functional perspective. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.253Search in Google Scholar

Caffarel, Alice. 2004. Metafunctional profile of the grammar of French. In Alice Caffarel, James Robert Martin & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen (eds.), Language typology: A functional perspective, 77–138. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.253.04cafSearch in Google Scholar

Fawcett, Robin P. 1980. Cognitive linguistics and social interaction: Towards an integrated model of a systemic functional grammar and the other components of a communicating mind. Heidelberg: Groos.Search in Google Scholar

Fawcett, Robin P. 1987. The semantics of clause and verb for relational processes in English. In Michael Alexander Kirkwood Halliday & Robin P. Fawcett (eds.), New developments in systemic linguistics: Theory and description, 130–183. London: Printer.Search in Google Scholar

Fawcett, Robin P. forthcoming. The functional semantics handbook: Analyzing English at the level of meaning. London: Equinox.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1967. Notes on transitivity and theme in English: Part 2. Journal of Linguistics (3). 199–244.10.1017/S0022226700016613Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1968. Notes on transitivity and theme in English: Part 3. Journal of Linguistics (4). 179–215.10.1017/S0022226700001882Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1985. An introduction to functional grammar. London: Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1994. An introduction to functional grammar, 2nd edn. London: Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen. 1999. Construing experience through meaning: A language-based approach to cognition. London & New York: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen. 2004. An introduction to functional grammar, 3rd edn. London: Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar, 4th edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203783771Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood & Edward McDonald. 2004. Metafunctional profile of the grammar of Chinese. In Alice Caffarel, James Robert Martin & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen (eds.), Language typology: A functional perspective, 305–396. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.253.08halSearch in Google Scholar

He, Wei, Ruijie Zhang, Xiaohong Dan, Fan Zhang & Rong Wei. 2017. Yingyu gongneng yuyi fenxi. [Functional semantic analysis of English]. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Search in Google Scholar

He, Wei. Forthcoming. Categorization of experience of the world and construction of transitivity system of Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

Journal Kyaw Ma Ma Lay. 1957. Thuema [She]. Yangon: Shwe Lin Yone.Search in Google Scholar

Lae Twin Thar Saw Chit. 2004. Kyanoramonnzonnkyanor [The person I hate most is me]. http://www.myanmarbookshop.com/MyanmarBooks/BookDetails/19951 (accessed 17 April 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Li, Jie & Chengfang Song. 2005. Gongneng yufa daolun disanban shuping [Review of An introduction to functional grammar, 3rd edn.]. Waiyu Jiaoxue yu Yanjiu [Foreign Language Teaching and Research] (4). 315–318.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, James Robert, Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen & Clare Painter. 2010. Deploying functional grammar. Beijing: The Commercial Press.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, James Robert. 2004. Metafunctional profile of the grammar of Tagalog. In Alice Caffarel, James Robert Martin & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen (eds.), Language typology: A functional perspective, 255–304. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.253.07marSearch in Google Scholar

Matthiessen, Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin. 1995. Lexicogrammatical cartography: English systems. Tokyo: International Language Sciences Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Maung Htin, Aung. 1962. Burmese law tales. London: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Prakasam, Vennelakanti. 2004. Metafunctional profile of the grammar of Telugu. In Alice Caffarel, James Robert Martin & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen (eds.), Language typology: A functional perspective, 433–478. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.253.10praSearch in Google Scholar

Rose, David. 2004. Metafunctional profile of the grammar of Pitjantjatjara. In Alice Caffarel, James Robert Martin & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen (eds.), Language typology: A functional perspective, 479–536. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.253.11rosSearch in Google Scholar