Abstract

Since 2014, more and more Chinese dramas have been streamed on international platforms such as YouTube, Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hulu, as well as on regional ones such as Viu, Naver, etc. Among those sites, Viki, with its special affordance features, has become a major platform for Chinese TV dramas to reach a global audience. The presence of Chinese TV dramas on Viki is a successful case of contra-flow of media products propelled by political, economic, technological and cultural factors. Based on the political economy and platform affordance theory, this paper explores why and how Chinese TV dramas offer new ways of presenting audiovisual content. It starts by laying out the political-economic context of the globalization of Chinese TV dramas and then focuses on how Viki has become a streaming hub. It examines the motivations of TV drama producers and distributors in the distribution of Viki and investigates the role of Viki from its specific platform affordances. The principal data sources of this study are market reports, news, and online observation. They show the internationalization process of Chinese TV dramas on Viki. The findings of this study share insights into how Chinese TV dramas as a kind of cultural product become internationalized in the platformization age of video-streaming and what the contra-flow of entertainment content implicates.

1 Introduction

The streaming era of TV signaled by Netflix is referred to as the “post-network era” of television, in which digital convergence significantly moved TV content from TV sets via cables to portable devices on streaming platforms (Lotz, 2017). Oh and Nishime (2019) argued that this is also marked as post-national television as the transnational flow of TV content has been greatly facilitated by streaming platforms such as YouTube, Netflix, and Viki. The global spread of Chinese TV dramas also showed a similar digital turn. In the past decade, by exporting TV dramas to international streaming platforms and expanding Chinese video platforms to foreign markets, Chinese TV industry has made much headway in globalizing Chinese TV dramas. More and more Chinese dramas are streamed on international platforms such as YouTube, Netflix, Amazon Prime, Hulu, regional platforms such as ViuTV, Naver, and international sites of WeTV, iQIYI, Youku, etc. Among those, Viki, with its special affordance features, has become a major platform for Chinese TV dramas to reach audiences across languages and cultures. The presence of Chinese TV dramas on Viki is an interesting case of transcultural flow of media product propelled by political, economic and technological factors.

Frame grab of Viki.com’s main page (Viki, 2022d).

Frame grab of Viki.com’s request page (Viki, 2022a).

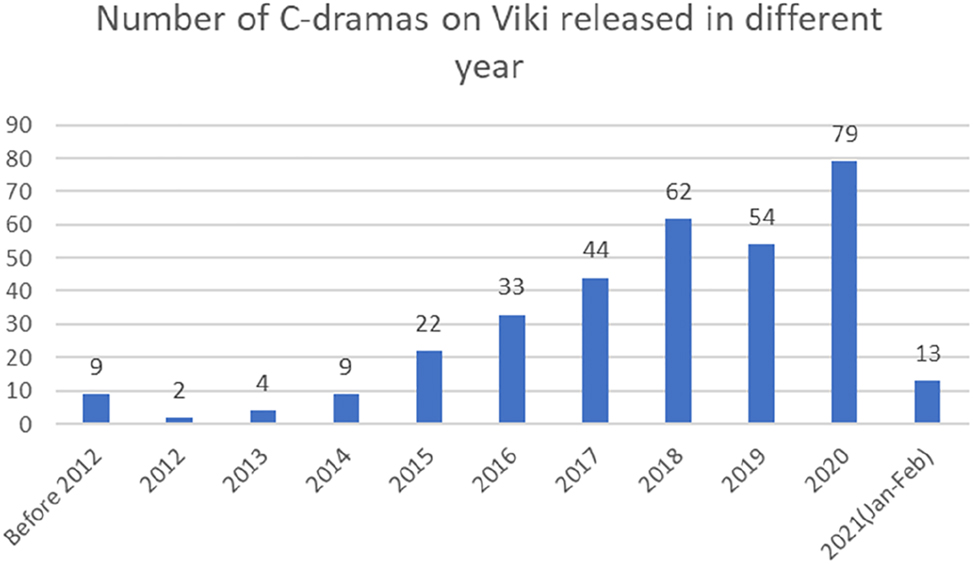

Number of C-dramas released on Viki released in different years (as of Feb 15th, 2021).

List of top10 C-dramas based on the number of ratings (as of Feb 15th, 2021).

|

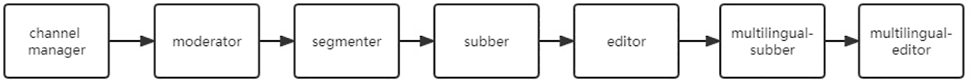

Process chart of fansubbing on the Viki.com.

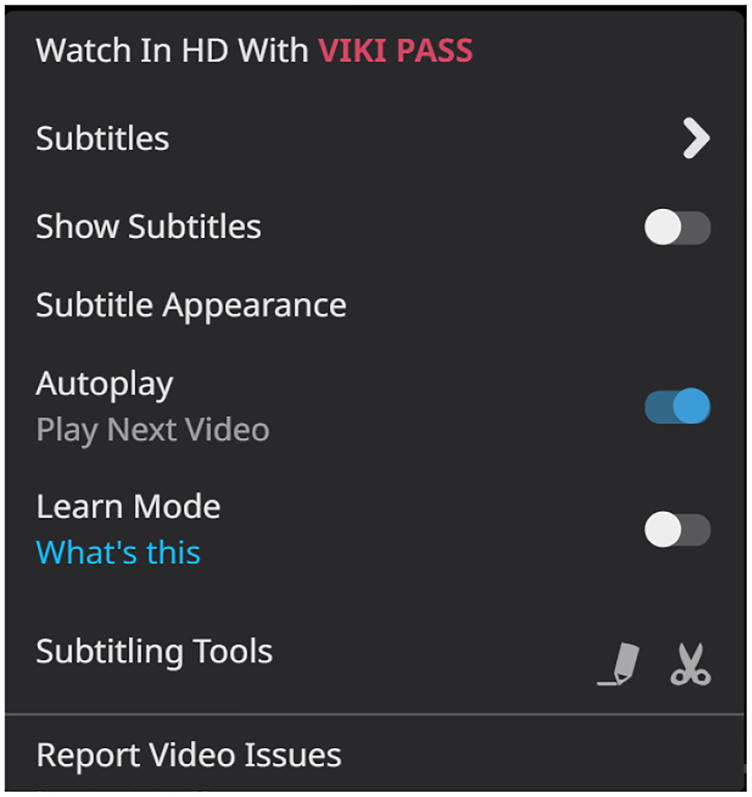

Frame grab of subtitle tools on Viki.com.

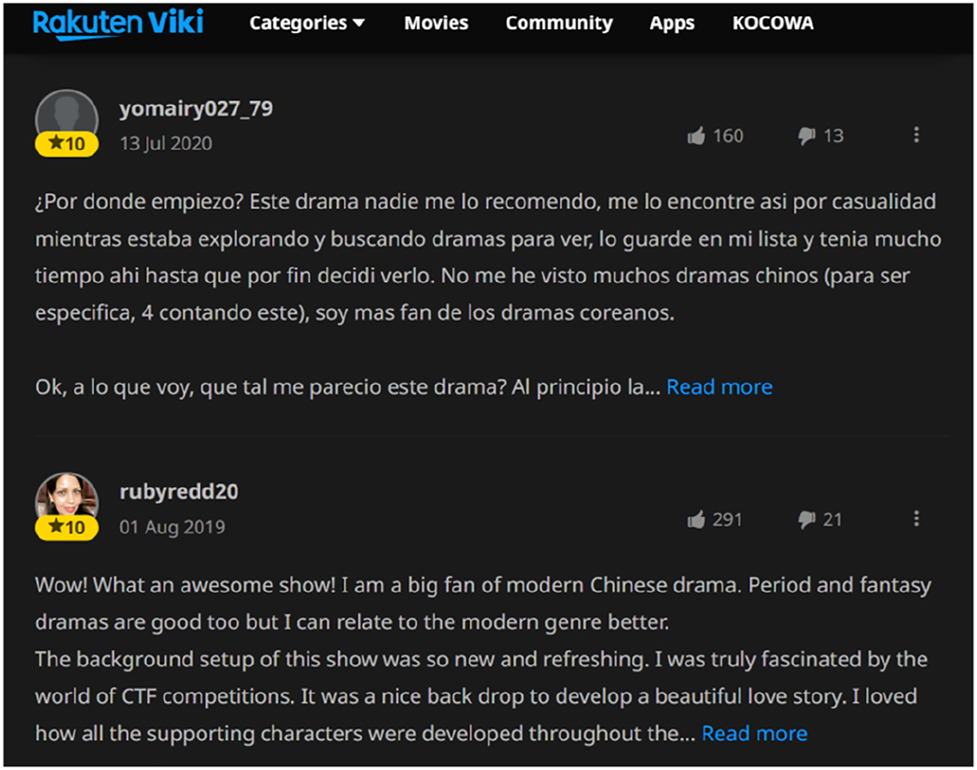

Snapshot showing user comments as interaction on Viki.

While the concept of cultural proximity (Straubhaar, 1991) has come to dominate the discussions on the transnational flow of Chinese dramas, it cannot explain the rising of Viki as a hub for global audiences across the world, many of whom do not share with China any linguistic, or cultural commonalities. To provide insights into the transcultural flow and consumption of C-dramas on Viki, this paper aims to offer a political-economic analysis and explore the specific affordances that Viki has enabled as a streaming platform and fan community.

2 Contextualizing the Globalization of C-Dramas: A Brief Overview

Chinese TV broadcasting started in 1958, under the name Beijing Television (it was changed to China Central Television, in 1978), marking the beginning of Chinese television production and broadcasting. Since the 1980s, with the advancement of China’s reform and opening up and the development of globalization, Chinese TV dramas, as a major type of cultural product, have begun to go overseas. The global reach of Chinese TV dramas have undergone several important stages (He, 2012). The first period is the Budding era (1980–1991) when early historical costume dramas like Journey to West, Dreams of Red Chamber were exported to other Asian countries, mostly as a means of cultural diplomacy. The second period is the Growth era (1992–1999) which is characterized by the early commercial efforts to sell C-dramas abroad. Dramas like Three Kingdoms and My Fair Princess (Huanzhu Gege) were well received in South Asian markets. This era was followed by a Challenge period (2000–2012) when exports experienced setbacks and lost competitiveness against the South Korean dramas in Asia. In 2005, while the hours of imported TV programmes amounted to 72,644, only 6680 h of Chinese TV programs were exported. Beyond Asia, because of political, linguistic and cultural reasons, China’s television exports to other parts of the world were much more limited (Zhang, 2007). Then, this paper argues that, from 2013 till now, supported by government policies and featured by increased exports to streaming platforms, this period has been marked by the platformatization of C-dramas exports. C-dramas have been increasingly available on global, regional and local streaming platforms to reach wider audiences. Internationalization moves of WeTV, iQIYI and Youku have also brought C-dramas to some overseas markets. To better understand this platform turn of C-dramas exports, we need to situate this transition in political and economic contexts.

2.1 Political Factor

The international dissemination of TV programs helps to enhance the country’s soft power, so national policies often play an important role in it (Nam, 2013). Since the 21st century, the Chinese government has paid increasing attention to the promotion of national soft power, constantly emphasizing the role of film and television cultural works in promoting international cultural exchanges, and actively promoting the “going-out” of film and TV programs, which is embodied in various cultural industry policies issued by the central and local governments (Zhang, 2011). For example, in 2001, several ministries released Regulations for the Implementation of “Going Global Project” of Radio, Film and Television, setting up a leadership workforce for “going-out” and requesting the establishment of international distribution firms. Thereafter, the Chinese government has implemented many taxation and funding policies to promote the selection, dubbing and international distribution of Chinese TV series and other contents (Dou, 2020). The National Radio and Television Administration set up the mechanism of China Pavilion, organizing Chinese producers and distributors to attend international film and TV fairs. At the provincial and city levels, local governments have also taken measures to facilitate the growth of the international export of TV programs. A salient example is Zhejiang province which set up the Experimental Zone for Chinese TV/Film Internationalization in 2018 and encouraged exports through financial rewards and launched the Chinese TV Drama (Web Series) Export Alliance.

2.2 Economic Factor

Economic considerations are another important drive from Chinese distributors to seek international markets. Compared with South Korean TV dramas, which have been popular in Asia since the late 1990s, the export of Chinese TV dramas started late. One of the important reasons is that the overseas market was difficult to expand and the profits were very small compared to the domestic market. When the costs were high and profits were low, most Chinese film and television producers did not have strong motivation to explore the international market before 2013 (Shangguan News, 2020). Only several leading enterprises have established overseas marketing teams to explore international distribution, such as Huace Film and Television, Hualu Baina, Keton Media, etc. However, since 2013, propelled by “going-out” policies, the fast growth of Chinese TV production and the booming of video streaming platforms across the world, some Chinese firms began to seriously look at the overseas market. New firms such as the Century UU specifically targeted at the international streaming sites YouTube and Viki for initial business contacts. As Li Fude, the founder of the Century UU said in an interview, he believed that there would potential overseas market for C-dramas and streaming platforms would be new avenues of outreach in times of media convergence due to the lower cost and less competition in the field of online distribution (Meng, 2017). The production capacity improvement also drove more Chinese companies to set eyes on overseas markets. According to statistics, 254 TV drama series were produced in China in 2019 alone, with 10,646 episodes. In addition, the quantity and the quality of C-dramas, especially web C-dramas have improved notably, which constitute a considerable proportion of exported dramas. According to a research report, 252 web series were released in China in 2021, accounting for 55.3% of the total dramas released (DataENT, 2022).

3 Theoretical Framework

3.1 Transcultural Flow and Platformization

Flow as an important concept in international communication has entered academic spotlight since 1970s. Major western countries especially the United States, dominated the international flow of audio-visual products, resulting in the one-way flow of media content from the West to the rest of the world (Schiller, 1976). In the US-dominated global media landscapes, scholars have also noted some cases of “contraflows” of media content disseminating from peripheral to center countries or within regional markets, including examples of Bollywood, K-pop etc (Iwabuchi, 2007; Thussu, 2019).

As platformization “entails the rise of the platform as dominant infrastructural and/or economic model in the industry” (Evens & Donders, 2018, p. 4). The growth of global video-streaming platforms has been fundamentally transforming the production, distribution and dissemination processes of cultural content (Nieborg & Poell, 2018). In the past two decades, platforms such as YouTube, Netflix, Amazon Prime, Hulu, etc., emerged as global platforms that enabled the convenient distribution and consumption of video programs over the internet across the borders (Lotz, 2017) and promoted the global fandom (Hills, 2018). The platformization of video-streaming also boasts important features like interactive communication, the productivity of multiple websites, and diversity of audience’s interpretation and usage patterns (Curtin, 2009).

With the global accessibility and connectivity of these platforms, counter-flow or two-way flow may be too narrow to account for the phenomenon which can rather be approached as transcultural flow. The term transcultural highlights the interactions in which participants can transgress and transcend languages and cultures (Baker, 2022, p. 288; Thussu, 2021). The burgeoning of video streaming platforms has opened up new academic discussions about whether global video platforms contributed to more transcultural flows or serve as a new form of “digital platform imperialism” (Jin, 2015). There are also concerns about the potential impacts of platform capitalism and algorithms on the free flow of media content (Lotz, 2021; Özgün & Treske, 2021) and the potential reconfigurative or disruptive influences on the national TV markets (Cunningham & Scarlata, 2020).

In this context, it is of great significance to probe into “how far other flows of media and cultural products have contributed to a more diverse transcultural media environment, reflecting the complexities of a more polycentric world” (Thussu, 2021, p. 21).

3.2 An Affordance Perspective

The concept of affordance was first proposed by Gibson (1986) in the field of ecological psychology to describe the possibilities of action offered for animals in relation to the properties of an environment. He conceptualized affordance as relational, depending on “the particular ways in which an actor, or set of actors, perceives and uses [an] object” (Gibson, 1986, p. 145). Norman (1999) used the term of “perceived affordances” to note that users’ use of affordances is based on their subjective perception of them. This conceptualization highlighted the user agency in using technologies. Besides, affordances are taken as ecological (Gibson, 1986). Chemero (2003) proposed to situate affordances at the interrelationships of artifacts, actors, and situations. Davis and Chouinard (2017) also argued to study affordances through interrelationships of perception, dexterity, and cultural and institutional legitimacy.

Scholars have attempted to synthesize the technological and social aspects of affordance. Hutchby (2001b) stressed that the concept of affordance advocates “a way of analyzing the technological shaping of sociality” (p. 444). According to him, affordances are both functional and relational. The functional nature stresses the materiality of technology that both enables and constrains actions while the relational nature highlights those affordances are specific to the perceiver and the context. Markus and Silver (2008) also emphasized that “functional affordance” is the “the possibilities for goal-oriented action afforded by technical objects to a specified user group by technical objects (p. 625)”. On the other hand, Hutchby (2001b, p. 30) highlighted the relational aspect of affordances by defining “communicative affordances” as “possibilities for action that emerge from the affordances of given technological forms”. Other communication scholars expanded the relational dimension of affordances. For example, communicative affordances are defined as “an interaction between subjective perceptions of utility and objective qualities of the technology that alter communicative practices or habits” (Schrock, 2015, p. 1232). Therefore, the concept of affordances avoids the limits of technological determinism and social constructivism of technologies, trying to reaching a balance between the two (Hutchby, 2001b, p. 448). In research, it is important to ‘locates affordances as part of communicative actions and can be best studied in and through the kinds of practices that technology allows for or constrains’.

Thus, when we aim to examine how Viki as a platform affords the content viewing, translating and viewer participation in C-dramas, the perspective of affordances could be of great value.

4 Case and Methods

4.1 The Case of Viki

Based in San Mateo, California, Viki was launched in 2007 as a video streaming site for Asian TV content and was acquired by Rakuten Viki in 2015. The platform prides itself on offering online viewing of Asian films and television entertainment programs with multilingual subtitles as its main business, serving users all over the world. After years of growth, now Viki has an ad-supported free model as well as an ad-free subscription model. Subscribers can enjoy priority access to new TV content as well as some movies.

Different from Netflix which positions itself as a digital broadcaster and producer, Viki from its birth is closely knitted with its users. Viki is meant to be a mix of the word “video” and “Wiki”, playing on the idea that the subtitles are user-generated, like content produced by users on the site Wikipedia. Since the model of crowd-sourcing subtitle translation is based on the participation of its users, Viki is not only a streaming site but also a fan community. The co-founder recognized the critical contribution of fans by saying “The idea morphed from a language-learning model into a global TV one, but powered by fans. The spine of Viki remains to be the passionate community of volunteer contributors” (Wee, 2014).

In 2017, American users made up over 30 percent of Viki’s international subscriber base, with France, Canada, the United Kingdom, Brazil and Mexico as the next five largest markets. Users are 73% female and 65% under the age of 34 years old (Cain, 2017). The company announced it reached more than 15 million subscribers globally (including those watching free with ads) in 2020, up 50% from a year ago (Klinge, 2020). In the first half of 2020, Viki enjoyed growth of over 50% in its subscription business, surpassing 15 million monthly active users among more than 32 million registered (Rakuten Today, 2020). In June, 2022b, Viki offers more than 1,700 shows and movies, including originals from South Korea, Japan, China and Thailand, etc. Among the shows, about 1,100 came from South Korea, and about 430 came from Chinese mainland.

4.2 Methods

This study mainly used three sources of material: virtual ethnography, industry press releases and users’ online discussions. The author has been conducting virtual ethnography (Hine, 2000) on Viki by watching Chinese TV shows regularly, observing user reviews, discussion forums and taking notes. In order to get first-hand experience of C-drama subbing, the author worked as a subber from Chinese to English for When a Snail Falls into Love (Ruguo Woniu You Aiqing). Besides, in order to gain an overview of the presence and reception of C-dramas on the site, the author collected the titles, number of views and number of reviews of all C-dramas on Viki, as well as all review texts of Go Go Squid (Qinai de, Reai de), Go Ahead (Yi Jiaren zhi Ming) and The Untamed (Chen Qing Ling) in February, 2021. This study collected news reports about Viki and C-dramas including interviews of industry professionals talking about Viki and C-dramas.

In order to understand how Viki audiences perceive C-dramas on the site, the study adopted “snapshot” technique by collecting popular user discussions on C-dramas on Viki Forum (by searching keyword: Cdrama) and discussion threads about Viki on Cdrama/reddit.com (by searching keyword: Viki). Top 10 threads on each forum were collected according to Most Relevance sorting. Viki Forum was chosen because it was the main venue where Viki users interact with each other while Cdrama/reddit.com was chosen because it was a very global online group where Viki users are very active. The collected texts from the discussion threads include Viki users’ expressions of their experiences and opinions of watching C-dramas on Viki, Viki’s translation quality, etc.

5 Analyzing the Transcultural Flow and Consumption of C-Dramas on Viki from the Lens of Platform Affordances

The content flow, consumption and platform attributes are deeply interwoven (Kiesow et al., 2021). In Viki’s case, the platform features itself as a streaming platform affording Asian content accessibility, fansubbing productivity as well as user interactivity and connectivity. This part will analyze how Viki’s platform affordances work in promoting the transcultural flow and consumption of C-dramas.

5.1 Content Accessibility

The availability of programs on the platform would be critical in defining the platform’s identity (Jenner, 2016). As a video streaming platform, the core affordance of Viki is the accessibility of video viewing. From the technological perspective, by browsing the Viki website or using Viki apps, users can conveniently watch videos on mobile devices or on big screens through projection. Users can browse the content either using the free model with ads or by paying a subscription for high-definition quality videos without ads (e.g., a monthly Viki Pass standard is 4.99 dollars in the US region).

From the content perspective, Viki distinguishes itself for its specialized Asian content accessibility for users, in response to users’ preference unveiled from the early phase of the site (Wee, 2014). The Asian content on Viki includes heavy South Korean TV content, considerable Chinese content, some Japanese and Thai content and so on (Figure 1). The specific content offering has made Viki a platform enabling the transcultural flow of Asian content to global audiences who may not share cultural proximity but share cultural interests.

Viki content distributors and Viki fans play an important role in deciding the content availability or the catalog on the site. Viki’s curation of Asian content is mainly bounded by copyright licensing agreements with distributors. After being acquired by Rakuten, Viki has undergone a legitimization process in which it removed unlicensed dramas from fan channels and committed itself to legitimately licensed dramas only. This transition put a limit on the range of content available on the site but enacted a commercial development for fansubbed TV content. After Viki has the license of streaming the dramas, commercial agreements may require Viki to block certain geographical areas for legal compliance. Geo-block has become an important tool employed by platforms to control the availability of their content (Lobato, 2019). Geo-blocking has been applied to C-dramas on Viki as well, which means a viewer in one region may not be able to access certain C-drama content. In response to this, some tech-savvy viewers would use VPN to go by the blocking mechanism and share the tips on online forums as fandom expertise. In addition to Viki and distributors, Viki users could also have a say in suggesting what dramas to license. Viki has been seeking the participation of users by soliciting requests for preferred dramas by users. Users can express their wishes for new dramas in the Viki Discussion forum (Figure 2). Therefore, the content accessibility of Chinese dramas is affected by complex dynamics between Viki, Chinese distributors and the users.

Viki started to stream Chinese dramas on the site from 2013 when the Sohu Video reached out to Viki to license its TV drama content. From 2014, more Chinese companies began to set eyes on expanding overseas market for C-dramas. In 2014, the Chinese film and television company Hualu Baina signed a cooperation agreement with Viki. Drama series such as the Happy Life of Golden Wolf were broadcast on the Viki platform. In the same year, the Century UU, a newly founded Chinese distributor, reached an agreement with Viki. The hit series Nirvana in Fire were streamed on Viki and translated into more than 10 languages. At present, Viki’s Chinese TV drama content partners include the Century UU, Hualu Baina, Huace Film and Television, etc.

According to the statistics of C-dramas streamed on Viki, as of February 15th, 2021, there are 414 Chinese film and TV dramas on the platform. After excluding movies and variety shows, there are 332 C-dramas, with the annual distribution as shown in the following figure (Figure 3). The number shows increasing content catalog of C-dramas on Viki, indicating its growing transcultural flow. Due to copyright reasons, the C-dramas launched on Viki may be available for an agreed time and then later be removed. So, far more C-dramas appeared on the Viki platform than 332. According to Jin (2017), up to July 24th, 2017, there had been 604 TV dramas and 149 films from Chinese mainland. According to a report of the Globe magazine by May 2018, 321 C-dramas had been translated or were being translated on Viki at that time. Therefore, we can see that the availability of C-dramas have been changing on the site, mostly due to copyright licensing reasons.

Viki audiences have shown a strong affection for modern romance dramas, which is different from traditional perceptions of C-drama consumption. The statistics of drama ratings further reveals that modern romance is the most popular genre of C-dramas on Viki, followed by costume dramas (Table 1). Of the top 10 C-dramas with the highest number of ratings, all of them belong to the modern romance genre, including some low-budget web dramas. If we look at the top 20, we’ll find a few costumes Xianxia/fairy drama and costume Xuanhuan/fantasy drama, such as The Untamed (56,328 ratings). This shows the Viki audience’s notable preference for modern romance dramas, although some popular ones are low-budget productions. One possible explanation might be that the audiences of Viki under the influence of K-dramas may have a similar inclination toward modern C-dramas. Costume dramas, including Wuxia, Xuanhuan and Xianxia are the second most popular genres, which correspond to the general international consumption pattern of C-dramas.

However, the presence of other actors in the streaming ecology would challenge Viki’s capacity in licensing Chinese drama content. Chinese streaming players, such as WeTV, iQIYI, Youku and Mango TV have been working to expand international markets in the last three years by setting up their own platform services in countries outside China. They have become more inclined to keep their original productions exclusively on their own platforms at release as a way to attract and retain international viewers. For example, big hits such as The Untamed, You Are My Glory didn’t become available on Viki until months later after their releases on WeTV. On the other hand, as C-dramas gain increasing market acceptance, more of them are sold to big streaming players like Netflix and Amazon, which would also increase content competition for Viki. Lacking the latest airing has become a new challenge for Viki in attracting viewers for C-dramas as content availability is an important factor that influences audiences’ migration across streaming platforms. For example, a Viki user said in one post, “since Viki does not cater to my tastes recently and all the dramas I really want to see are ‘out there’ so I am forced to find my ‘sources of entertainment’ outside lately …” (Viki, 2017).

5.2 Multilingual Fansubbing Productivity

Hutchby (2001a, p. 26) argued, “different technologies possess different affordances”. That is, technologies constrain the ways that they can be perceived and used. Viki’s unique technological affordance lies in the multilingual subtitle translation mechanism enabled by Viki’s technological functions that provide for crowdsourced translation work and by Viki’s participatory community culture involving thousands of translation volunteers, or so-called fansubbers. Fansubbing, as a fan participation practice, has been developing for several decades, mostly bypassing copyright laws in order to do so and making their translations available for free on the internet (Dwyer, 2016). Viki is among the very few that manages to build a business model on fansubbing legitimately licensed content. Typically, translation on Viki can be completed in a very short time by the way of crowdsourced translation. After the online date of the new series is determined, the interested subtitle team will recruit video syncopators to segment the video and translators in various languages to participate in translation. Through self-management and collaboration, volunteers from all over the world have completed a series of multilingual subtitle translation film and television works. Up to June, 2021, the platform’s subtitle translation volunteers have translated more than 2 billion words, equivalent to more than 20,000 novels (ChinaPavilion, 2020). The multilingual subtitles provided by Viki and the volunteer community helped global Viki users to “transgress and transcend linguistic and cultural borders” (Baker, 2022, p. 288). The following chart shows the multilingual subtitling process on Viki (Figure 4).

The multilingual subtitling is made possible with the technological and collaboration mechanisms of Viki. Firstly, Viki offers the online subtitling system to make it easy for subbers, called Contributor Tools (Segment Timer, Subtitle Editor, Team Discussions, etc.). This is an easy-to-use online system which does not require professional technological expertise. Once admitted to the subbing team, a subber can easily click on subtitling webpage and input the translation text without prior technical training (Figure 5). Secondly, Viki has established a set of community practices from recruiting volunteers, training segments, rewarding contributors to maintain the volunteer system. Viki makes subtitling open to any user to participate in, conducive to a sense of community. On the other hand, this also results in uneven translation quality of subtitles. As viewers commented, the quality of Viki translation depends on the teams. In order to attract volunteers and recognize their valuable work, Viki has developed a crowd-sourcing community culture such as listing all members of the Subtitling Team on the drama page and displaying Awesome Contributors monthly chart and a benefit system for Qualified Contributors recognized as the “most active and supportive community members”. Channel mangers can post recruitment information on the discussion forum or subbers can message the channel managers or any moderator to be admitted.

For C-dramas, multilingual subtitles offered by Viki serve as the most salient feature of the platform that attracts both Chinese distributors and global C-drama viewers. The typical process is to set up a subbing team who will translate the Chinese subtitles into English, and then other language subbers will translate from English to other languages. According to the author’s personal experience, the English subtitle translation of a TV series that was put on simultaneously in Viki can be completed within 24–36 h of broadcasting in China (a 40-min episode is usually cut into four parts, and each part lasts for about 10 min, and can be claimed and translated by four translators at the same time), and then translated into other languages by other volunteers.

Although C-dramas on Netflix and YouTube also offer subtitles in major languages, the unparalleled linguistic diversity of subtitles empowered by legitimated fansubbing remains a defining platform feature of Viki (Jin, 2017). Based on online observations, popular C-dramas are often translated into more than 10 languages, including some minor languages in the world. For example, Go Ahead was translated to 21 languages, including Dutch and Telugu. The Untamed was translated into 32 languages, including Croatian, Bulgarian, Czech, Swedish, Slovak, Serbian, Tagalog and so on. In addition, the translation quality of Viki is often appreciated as an outcome of dedicated volunteer efforts. According to audience discussions on Cdrama/reddit.com, Viki’s translation quality is often applauded by C-drama fans. It’s mentioned by many that Viki’s translation usually offers more cultural explanations than those of Netflix, partly because fansubbers usually have more interest and affection to uncover the cultural connotations in the drama. For example, in posts discussing translation quality, discussants mentioned that Viki subtitles are translated by “volunteers who know the culture and contexts very well” and can “best explain cultural contexts” (Reddit, 2021, 2022).

The fansubbing mechanism and practices have produced quality subtitles for C-dramas that attract Chinese distributors to license their works. As the general manager of Hualu, Xiang Jing acknowledged in a media interview that Hualu was attracted to Viki mainly for two reasons: first, Viki was open to drama selections and second, the multilingual subtitles of Viki could help Hualu dramas reach the wider audience (Yin, 2019). On the other hand, as the multilingual subtitles also play significant roles in enabling global viewers to consume the Chinese content, Viki fansubbers empowered change in the transcultural flow of C-dramas by serving the role of “new cultural intermediaries” (Lee, 2012). Viki CEO Sam Wu also acknowledged that the high-quality subtitles contributed by Viki community fans have reduced language and cultural barriers, and the global audience can better understand Chinese stories and be attracted by wonderful Chinese stories. With the increase in audience’s interest in Chinese content, Viki has naturally increased its purchasing volume of Chinese content (ChinaPavilion, 2020).

Yet, the relationships among Viki, fansubbers and viewers can become tense at times. Viewers expect fast-speed and quality translation of the subtitles while the subbing team, most of whom are volunteers could feel pressured by the demand from viewers. This problem is precipitated by the fact the C-dramas usually release more episodes per week than K-dramas. Fan-subbing also triggered heated debates on digital labor. Viki has been accused of exploiting fans’ digital labor for making commercial profits. Obviously, Viki would not give up this unique signature service that has defined its genes and sustained its growth in the past years. Therefore, we can see tensions and negotiations going on between the fansubbing community and Viki management, which would be affecting Viki’s future growth.

5.3 Transcultural Social Affordances—Interactivity and Connectivity

In the technology context, social affordances are empowered by technology’s material features (Treem & Leonardi, 2012), which can enable social interactions (McGrath et al., 2016). Viki associates itself with Asian-drama fandom and brands itself a site not only made for fans, but “powered by fans” (Viki, 2022c). As a fandom-driven site, Viki prides itself on a variety of features that enable communication and contribute to fandom building. Besides fansubbing, user reviews, fan forums, and timed comments all contribute to the site’s sense of community.

Each drama page offers a rating and commenting function (Figure 6). Viewers are encouraged to rate the dramas they have watched and leave comments in the Comment section. They can also vote up the comments they agree with so that these comments would be seen first according to popularity filtering. Viewers could read others’ reviews about the dramas and post their own reviews to contribute. These features are conducive to enhancing interaction among users and users’ identification with the site. This paper collected viewer comments from Go Go Squid, Go Ahead and The Untamed (February, 2021). Among the 12,147 reviews of Go Go Squid, reviews in English account for 40%; reviews in Portuguese and Spanish account for 20% respectively, with French reviews accounting for 3.7% and Italian reviews 2%. In the reviews of Go Ahead, English, Spanish, Portuguese, and French account for 44, 32, 16 and 3% of the 6282 reviews respectively. For The Untamed, there are 7500 reviews, including 3176 in English, accounting for nearly 50%, and 2746 in Portuguese and 1681 in Spanish, accounting for 37 and 22% respectively. As non-English native users may also use English, the international common language, to make comments and facilitate communication, it should be noted that English comments are not necessarily from native English speakers. Many of the Spanish and Portuguese reviews came from Latin America users, as Viki boasts a growing presence in the region (Davis, 2021).

Timed Comments (similar to Danmu on Chinese video streaming sites) is another special feature of Viki introduced in 2020 that allows users to leave comments in a video at a certain point of time. Thus, viewers can read others’ comments while watching and make their own comments as if having conversations with other viewers. This practice adds a communal layer of the drama reception by audiences (Locher & Messerli, 2020).

Co-viewing helps build a communal watching experience. To further enhance the sense of community, Viki launched a Watch-party function in May, 2020, enabling viewers across the world to watch the same episode at the same time and “synchronously post comments at any timestamp inside the video content” (Lin et al., 2018, p. 274). Sometimes Viki plans the watch party itself, announces the arrangements and any of its users can join. Users can also organize a private watch party and invite others to join. Although most digital streaming sites are proud of personalized viewing schedules, this feature offered by Viki aims at providing a simultaneous watching experience and creating virtual connections for viewers located in different places. This practice revolts against the idea of personalized schedules characterizing streaming platforms, and highlights the idea of community and sharing.

As mentioned earlier, there are some important ways for Viki users participate in interaction on the Viki Discussion forum, where it’s common to find posts discussing C-dramas and related topics. For example, in a post titled “C-dramas you loved the most”, users talked about their favorite dramas. It is also an important venue for subbing teams to recruit members by posting a recruitment message. There are posts recruiting subbers, segmenters, etc. The forum also serves as a channel for the Viki Team to communicate with users and elicit user feedback. For example, a post in the forum asked users about their opinions on what C-dramas to license. Users can also post a message in the forum, inviting people to request Viki to consider the interested drama. This shows that users are aware of their agency over the platform content and are willing to execute it.

It should be noted that viewers of Viki not only participate on Viki but also on cross-platforms. For example, some users set up Discord groups and moved there for discussions. Multi-platform migration has to some extent deactivated discussions on Viki which is manifested in the less active updates in discussions in recent years.

6 Conclusion

Relying on the multilingual subtitles produced by its technological attributes and the global user community, Viki has empowered the transcultural flow and consumption of Asian content. While the dissemination of C-dramas on Viki was propelled by political and economic factors in the past decade, we can see that Viki has played an active role in helping C-dramas reach audiences across languages and cultures with its unique platform affordances. In terms of content curation, Viki as a platform has not only focused on Asian content but also provided a niche venue for global audiences who have shared interest and taste in Asian culture and TV productions. In this sense, Viki users consume C-dramas more out of cultural affinity rather than cultural proximity (Morimoto & Chin, 2013). Unlike many illegal sites, Viki managed to do so through legitimate licensing of content and profit from advertising and subscriptions. Success of Viki can be taken as an example of transcultural flow enabled by the combination of corporate capitalism, platform affordances and transcultural fandom.

The success of Viki lies to a great extent in the multilingual fan-subtitling enabled by the platform, which is in essence the main attraction for both Chinese distributors and Viki users. For the former, Viki’s affordance in subtitles has made it possible for C-dramas to go beyond the Asian market and reach global audiences by crossing diverse language barriers. For the users, Viki differs from Netflix in emphasizing that user choices may reflect a move considering viewers as customers (Johnson, 2019). Instead, Viki created the lore branding itself as a community and viewers as participants. It builds up technological features and community culture to encourage users to participate in fan-translation. The social affordances of Viki also contribute to the making of a global C-drama fandom. By rating or posting reviews, organizing or joining watch parities, viewers share with each other ideas and feelings about C-dramas.

Meanwhile, as C-dramas are becoming accessible through more diverse platforms for global diffusion, Viki is facing its own dilemmas, especially in licensing new dramas and applying geo-blocking as licenses stipulate. This means study of streaming platforms should be situated in the wider ecology of global video streaming platforms.

This research has its own limitations. One major limitation is that it primarily focused on the materiality of Viki and used online ethnography for observing user interactions with Viki. Future work can look further in the following areas. First, the study of C-dramas on Viki needs to further investigate the audience’s perception and actions in order to better understand the audience community. Existing studies about C-dramas on Viki are mostly confined to translation studies, which means there is a gap to fill to in terms of audience studies. Second, future research needs to situate the globalization of C-dramas in the fluid context of video streaming platforms. Viki is one of the many platforms via which C-dramas are streamed and accessed by international audiences. The relationship between Viki and other platforms is both complementary, mutually beneficial and competitive. Other platforms including Netflix, Chinese platforms such as WeTV, iQIYI, Youku also deserve academic attention.

Future research could be conducted from these perspectives to offer a more nuanced and complex understanding of the new streaming and consumption practices within the larger context of streaming platforms and seek to understand how this conduces to counter-flow of cultural products in the Global South in particular.

Funding source: Ministry of Education, Project of Humanities and Social Sciences

Award Identifier / Grant number: Project No. 17YJC860035

-

Research funding: This research is supported by MOE (Ministry of Education of China) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (Project No. 17YJC860035).

References

Baker, W. (2022). From intercultural to transcultural communication. Language and Intercultural Communication, 22(3), 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2021.2001477.Search in Google Scholar

Cain, R. (2017, October 24). Viki.com is the most innovative streaming video service you haven’t heard about. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/robcain/2017/10/24/viki-com-is-the-most-innovative-streaming-video-service-you-havent-heard-about/?sh=743f46bd2ff9Search in Google Scholar

Chemero, A. (2003). An outline of a theory of affordances. Ecological Psychology, 15, 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326969eco1502_5.Search in Google Scholar

ChinaPavilion (2020, August 12). 干货!Viki首席执行官解密爆款国剧出口经验 (中英双语) [Viki’s CEO reveals his experience in exporting popular Chinese TV dramas]. Weixin Official Accounts Platform. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=Mzg3MTc1MDQwMg==&mid=2247505058&idx=1&sn=22a4a536a45a961887af9e5f9a68a239&source=41#wechat_redirectSearch in Google Scholar

Cunningham, S., & Scarlata, A. (2020). New forms of internationalisation? The impact of Netflix in Australia. Media International Australia, 177(1), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878x20941173.Search in Google Scholar

Curtin, M. (2009). Matrix media. In J. Tay, & G. Turner (Eds.), Television studies after TV: Understanding television in the post-broadcast era (pp. 9–19). Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

DataENT. (2022, January 5). 2021 连续剧网播表现及用户分析报告 [2021 Series webcast performance and user analysis report]. Front-Page Story of Tencent. https://new.qq.com/omn/20220105/20220105A0AAM800.htmlSearch in Google Scholar

Davis, J. L., & Chouinard, J. B. (2017). Theorizing affordances: From request to refuse. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 36(4), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467617714944.Search in Google Scholar

Davis, K. (2021, January 20). How Rakuten Viki is promoting K-drama to a global audience. MarTech. https://martech.org/how-rakuten-viki-is-promoting-k-drama-to-a-global-audience/Search in Google Scholar

Dou, J. Q. (2020). China on screen: Review the going out of Chinese TV and films in the new era. PhD Dissertation. Shanxi Normal University.Search in Google Scholar

Dwyer, T. (2016). Multilingual publics: Fansubbing global TV. In P. Marshall, G. D’Cruz, S. McDonald, & K. Lee (Eds.), Contemporary publics. Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/978-1-137-53324-1_10Search in Google Scholar

Evens, T., & Donders, K. (2018). Platform power and policy in transforming television markets. Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-319-74246-5Search in Google Scholar

Gibson, J. J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual perception. Psychology Press.Search in Google Scholar

He, X. (2012). Intercultural communication of Chinese TV Dramas in the globalization context. PhD Dissertation. China Art Research Institute.Search in Google Scholar

Hills, M. (2018). Netflix, transfandom and “trans TV”: Where data-driven fandom meets fan reflexivity. Critical studies in television. The International Journal of Television Studies, 13(4), 495–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749602018797738.Search in Google Scholar

Hine, C. (2000). Virtual ethnography. Sage Publications.10.4135/9780857020277Search in Google Scholar

Hutchby, I. (2001a). Conversation and technology: From the telephone to the internet. Polity.Search in Google Scholar

Hutchby, I. (2001b). Technologies, texts and affordances. Sociology, 35(2), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/s0038038501000219.Search in Google Scholar

Iwabuchi, K. (2007). Contra-flows or the cultural logic of uneven globalization? Japanese media in the global agora. In D. Thussu (Ed.), Media on the move: Global flow and contra-flow (pp. 67–84). Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Jenner, M. (2016). Is this TVIV? On Netflix, TVIII and Binge-watching. New Media & Society, 18(2), 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814541523.Search in Google Scholar

Jin, D. Y. (2015). Digital platforms, imperialism and political culture (1st ed.). Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Jin, H. (2017). Fan translation and internationalization of Chinese dramas-case of Viki. TV Research, 10, 85–88.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, C. (2019). Online TV. Routledge.10.4324/9781315396828Search in Google Scholar

Kiesow, D., Zhou, S., & Guo, L. (2021). Affordances for sense making: Exploring their availability for users of online news sites. Digital Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1989316Search in Google Scholar

Klinge, N. (Ed.). (2020, July 22). Watch parties and K-pop. How San Mateo streamer Rakuten Viki is growing in a pandemic. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/business/story/2020-07-22/kpop-rakuten-viki-korean-dramas-streaming-watch-parties-parasite1Search in Google Scholar

Lee, H.-K. (2012). Cultural consumers as ‘new cultural intermediaries’: Manga scanlators. Arts Marketing: An International Journal, 2(2012), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1108/20442081211274011.Search in Google Scholar

Lin, X., Huang, M., & Cordie, L. (2018). An exploratory study: Using Danmaku in online video-based lectures. Educational Media International, 55(3), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2018.1512447.Search in Google Scholar

Lobato, R. (2019). Netflix nations. In Netflix Nations. New York University Press.10.18574/nyu/9781479882281.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Locher, M. A., & Messerli, T. C. (2020). Translating the other: Communal TV watching of Korean1 TV drama. Journal of Pragmatics, 170, 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.07.002.Search in Google Scholar

Lotz, A. D. (2017). Portals: A treatise on internet-distributed television. University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.9699689Search in Google Scholar

Lotz, A. D. (2021). In between the global and the local: Mapping the geographies of Netflix as a multinational service. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(2), 195–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877920953166.Search in Google Scholar

Markus, M. L., & Silver, M. S. (2008). A foundation for the study of IT effects: A new look at DeSanctis and Poole’s concepts of structural features and spirit. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 9(10/11), 609–632. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00176.Search in Google Scholar

McGrath, A. R., Tsunokai, G. T., Schultz, M., Kavanagh, J., & Tarrence, J. A. (2016). Differing shades of colour: Online dating preferences of biracial individual. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(11), 1920–1942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1131313.Search in Google Scholar

Meng, X. (2017, August 22). 作为《琅琊榜》海外发行方, 世纪优优着力布局视频、游戏及网文出海 [As the overseas publisher of Nirvana in Fire, Century Youyou focuses on the distribution of videos, games and online articles]. Iyiou.com. https://www.iyiou.com/news/2017082253351Search in Google Scholar

Morimoto, L., & Chin, B. (2013). Towards a theory of transcultural fandom. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 10(1), 92–108.Search in Google Scholar

Nam, S. (2013). The cultural political economy of the Korean1 wave in East Asia: Implications for cultural globalization theories. Asian Perspective, 37(2), 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2013.0008.Search in Google Scholar

Nieborg, D., & Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4275–4292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769694.Search in Google Scholar

Norman, D. A. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design. ACM.10.1145/301153.301168Search in Google Scholar

Oh, D. C., & Nishime, L. (2019). Imag(in)ing the post-national television fan: Counter-flows and hybrid ambivalence in Dramaworld. The International Communication Gazette, 81(2), 121–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048518802913.Search in Google Scholar

Özgün, A., & Treske, A. (2021). On streaming-media platforms, their audiences, and public Life. Rethinking Marxism, 33(2), 304–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2021.1893090.Search in Google Scholar

Rakuten Today. (2020, November 13). Rakuten Viki launches private Watch Parties to bring fans together. https://rakuten.today/blog/rakuten-viki-launches-private-watch-parties.html.Search in Google Scholar

Reddit. (2021, September 21). Translation question. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/CDrama/comments/psucd4/translation_question/Search in Google Scholar

Reddit. (2022, September 13). Subtitles – Netflix v iqiyi v Viki. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/CDrama/comments/xcskv4/subtitles_netflix_v_iqiyi_v_viki/Search in Google Scholar

Schiller, H. I. (1976). Communication and cultural domination. International Arts and Sciences Press.Search in Google Scholar

Schrock, A. R. (2015). Communicative affordances of mobile media: Portability, availability, locatability, and multimodality. International Journal of Communication, 9, 1229–1246.Search in Google Scholar

Shangguan News. (2020, March 15). 揭秘! “三生三世” 等国产热剧在海外受热捧, 做对了什么? [Revelation! Domestic hits such as “Three Lives and Three Lives” are gaining popularity overseas. What are they doing right?]. New.qq.com. https://new.qq.com/omn/20200315/20200315A0DT9O00.htmlSearch in Google Scholar

Straubhaar, J. D. (1991). Beyond media imperialism: Assymetrical interdependence and cultural proximity. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 8(1), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295039109366779.Search in Google Scholar

Thussu, D. (2019). International communication: Continuity and change. Bloomsbury Academic.Search in Google Scholar

Thussu, D. (2021). Transcultural communication for a polycentric world. Journal of Transcultural Communication, 1(1), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtc-2021-2003.Search in Google Scholar

Treem, J., & Leonardi, P. (2012). Social media use in organizations: Exploring the affordances of visibility, editability, persistence, and association. Communication Yearbook, 36, 143–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2013.11679130.Search in Google Scholar

Viki. (2017, July 9). Cdrama lovers, what are you watching now in Viki? Viki Discussions. https://discussions.viki.com/t/cdrama-lovers-what-are-you-watching-now-in-viki/16434Search in Google Scholar

Viki. (2022a, January 4). Request a TV show or movie. Viki. https://support.viki.com/hc/en-us/articles/360034633713-Request-a-TV-Show-or-MovieSearch in Google Scholar

Viki. (2022b, October 19). Watch Korean1 dramas, Chinese dramas and movies online. https://www.viki.com/explore?country=mainland-china&sort=all_timeSearch in Google Scholar

Viki. (2022c, October 19). https://rakuten.wd1.myworkdayjobs.com/zh-CN/RakutenVikiSingapore. https://Rakuten.wd1.Myworkdayjobs.com. https://rakuten.wd1.myworkdayjobs.com/zh-CN/RakutenVikiSingaporeSearch in Google Scholar

Viki. (2022d, October 20). Watch Korean1 dramas, Chinese dramas and movies online. https://www.viki.com/explore?country=mainland-china&sort=all_timeSearch in Google Scholar

Wee, W. (2014, April 21). Tech in Asia – Connecting Asia’s startup ecosystem. Techinasia. https://www.techinasia.com/story-of-viki-and-razmig-hovaghimianSearch in Google Scholar

Yin, K. (2019). Over one hundred C-dramas were sold overseas. Retrieved from. http://www.xinhuanet.com/zgjx/2019-01/11/c_137735222.htmSearch in Google Scholar

Zhang, H. (2011). The globalization of Chinese television. International Communication Gazette, 73(7), 573–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048511417156.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, X. (2007). Globalisation of Chinese TV drama: Challenges and opportunities. Critical Studies in Television, 2(2), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.7227/cst.2.2.5.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The Mediated Engagement of Switzerland with BRI: A Transnational Comparative Framing Analysis

- Game Playing in the Platform Society: A Cultural-Political Economy Analysis of the Live Streaming Industry in China

- “Platform Amphibiousness” in Covid-19: The Construction and Communication of National Image in the Global South in the Polymedia Use of Chinese Overseas Students

- Exploring How Chinese TV Dramas Reach Global Audiences via Viki in the Transnational Flow of TV Content

- Transformation in Gender Narrative in the Context of Globalization – Study on the Screen Image of Mulan

- Commentary

- Imagining the New Global Village

- Book Reviews

- Balbi, G. et al. Eds. (2019). China and the Global Media Landscape: Remapping and Remapped. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing

- Internationalizing “International Communication”

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The Mediated Engagement of Switzerland with BRI: A Transnational Comparative Framing Analysis

- Game Playing in the Platform Society: A Cultural-Political Economy Analysis of the Live Streaming Industry in China

- “Platform Amphibiousness” in Covid-19: The Construction and Communication of National Image in the Global South in the Polymedia Use of Chinese Overseas Students

- Exploring How Chinese TV Dramas Reach Global Audiences via Viki in the Transnational Flow of TV Content

- Transformation in Gender Narrative in the Context of Globalization – Study on the Screen Image of Mulan

- Commentary

- Imagining the New Global Village

- Book Reviews

- Balbi, G. et al. Eds. (2019). China and the Global Media Landscape: Remapping and Remapped. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing

- Internationalizing “International Communication”