Abstract

The use of high-fidelity camera-vision and Doppler tracking systems in Major League Baseball (MLB) has created an influx of advanced analytics that have transformed game and personnel strategy. However, due to the cost and complexity of these systems, advanced statistics are severely limited in most amateur games. In this work, we develop a robust pitch reconstruction methodology using artificial neural networks (ANN) and a three-point reconstruction technique, requiring the knowledge of only three baseball spatiotemporal locations. The ANN models were trained to predict the initial baseball speed and spin rate, which are then used as initial conditions to integrate the full pitch trajectory. We use numerically simulated baseball pitches to train two ANN models, each with clean and noisy training inputs, respectively. We then performed a robustness analysis to test ANN performance with increasingly noisy data to simulate low-fidelity camera tracking systems. Probability distributions of predicted model output are calculated using the Monte Carlo method to quantify model uncertainty. We show that the ANN models accurately predict the true baseball trajectory from both high-fidelity and noise-injected testing data. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of ANN models for quick and robust pitch trajectory reconstruction using minimal input data, even in the presence of noise. The present methodology provides a first step towards enabling pitch tracking and advanced analytics in a wider variety of baseball games.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable as there were no human subjects and IRB approval is not applicable.

-

Author contributions: R. DeBoskey – Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing. V. Hasti – Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Resources, Supervision, Writing – reviewing and editing. V. Narayanaswamy – Supervision, Resources, Writing – reviewing and editing.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Research funding: This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Ryan DeBoskey was supported by the National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship.

-

Data availability: Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Appendix A: Baseball trajectory model

Equation (1) is the governing equation for baseball trajectory, derived from Newton’s second law of motion. The equation is a simplified version derived from Aguirre-López et al. (2018), which assumed the centrifugal and Coriolis body forces are both negligible. The centrifugal and Coriolis forces are approximately two orders of magnitude smaller than the magnus force and are generally negligible to trajectory calculation (Robinson and Robinson 2017). The drag force, f D , was given by Giordano (1996):

where v is the velocity vector, v is the velocity magnitude, and v d = 35 m/s and Δ = 5 m/s are calibrated model constants. The magnus force, f M , is present and plays a prominent effect in the physics of ball trajectory in many sports (Kray et al. 2014; Sayers and Hill 1999). The force is oriented orthogonal to the spin axis and velocity, resulting in the well-known curving of baseball pitches. By Bernoulli’s principle, the net force was given by the cross product (×) of velocity about the spin axis:

where B = 0.00041 is a non-dimensional scaling factor given by Giordano (1996) for baseballs. We assumed a constant acceleration due to gravity, g = −9.81 m/s2, in the z-direction. We solved Equation (1) using 4th-order Runge–Kutta time integration (Lomax et al. 2001) with a fixed time step, Δt = 2.083 ms.

Several simplifying assumptions were made in the current work. First, we neglected the orientation of the baseball seams. Extremely complicated physics, including the seam-shifted wake phenomenon (Smith and Smith 2021), arise from the transition and break-up of the boundary that develops over the ball due to the presence and orientation of the seams on an otherwise smooth sphere (Higuchi and Kiura 2012). This results in small fluctuations to the baseball trajectory, which may not be negligible compared to magnus forces (Borg and Morrissey 2014; Higuchi and Kiura 2012; Smith and Smith 2021).

Secondly, the batch simulations assume a fixed spin axis, ϕ = 45°, fixed launch angle α = 1°, and constant release point, x o = (0, 0, 0). In addition to the speed and spin rate, the spin axis is very important for pitch classification (the constant angles of ϕ = 45° and α = 1° used in the present study correspond roughly with a curveball from a right-hand pitcher). The magnus force is directed orthogonal to the spin axis and velocity (via Eq. (10)) which causes the breaking direction of the pitch. With differing amounts of break and velocity, the pitcher must adjust the launch angle accordingly between pitches. The fixed angles and constant release point were used in the present work to reduce dimensionality to demonstrate the use of an ANN as a proof-of-concept for pitch reconstruction. Higher dimensional prediction output (necessary to predict spin axis, launch angle, and initial condition) requires a much larger ANN model and substantially more training data (curse of dimensionality), which is outside the scope of the present work. The spatiotemporal release point of the baseball must be known to determine the relative deflection of the pitch. We assumed a known release point in this paper, which in practice must be determined by the system to fully reconstruct trajectory. This introduces an additional data point (and associated uncertainty) to collect and process within a real-world pitch tracking system.

Lastly, we sampled the training data for the ANN at a fixed constant interval (t1 = 0.467 s, t2 = 0.483, and t3 = 0.5s). The selection of time interval in the present work was arbitrary, where t3 is the (approximate) time required for an 80 mph pitch to reach home plate without consideration of the pitcher’s extension from the rubber. Sampling at the same three time points (relative to release) cannot be realized in practice, particularly for a low-cost vision tracking system. The relative time from release would need to be varied for a real-world system, providing another layer of complexity.

Appendix B: ANN sensitivity study

We performed a sensitivity study to determine the training batch size, activation function for the hidden layers, and number of hidden layers to be used by the final model. Table 8 summarizes the range of hyperparameters tested in this sensitivity study. We used minimization of the mean-squared training and testing loss as the parameter to evaluate the ANN performance. The sensitivity study was performed only on the Quiet ANN model, as a larger number of training epochs was required to train this model. The decrease in time required to train the Noisy ANN model was indicative of a less complex mapping due to lower-fidelity input data.

Summary of ANN hyperparameter sensitivity study.

| Hyperparameter | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch size | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| Activation function | sigmoid | tanh | relu | leakyrelu |

| Hidden layers | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

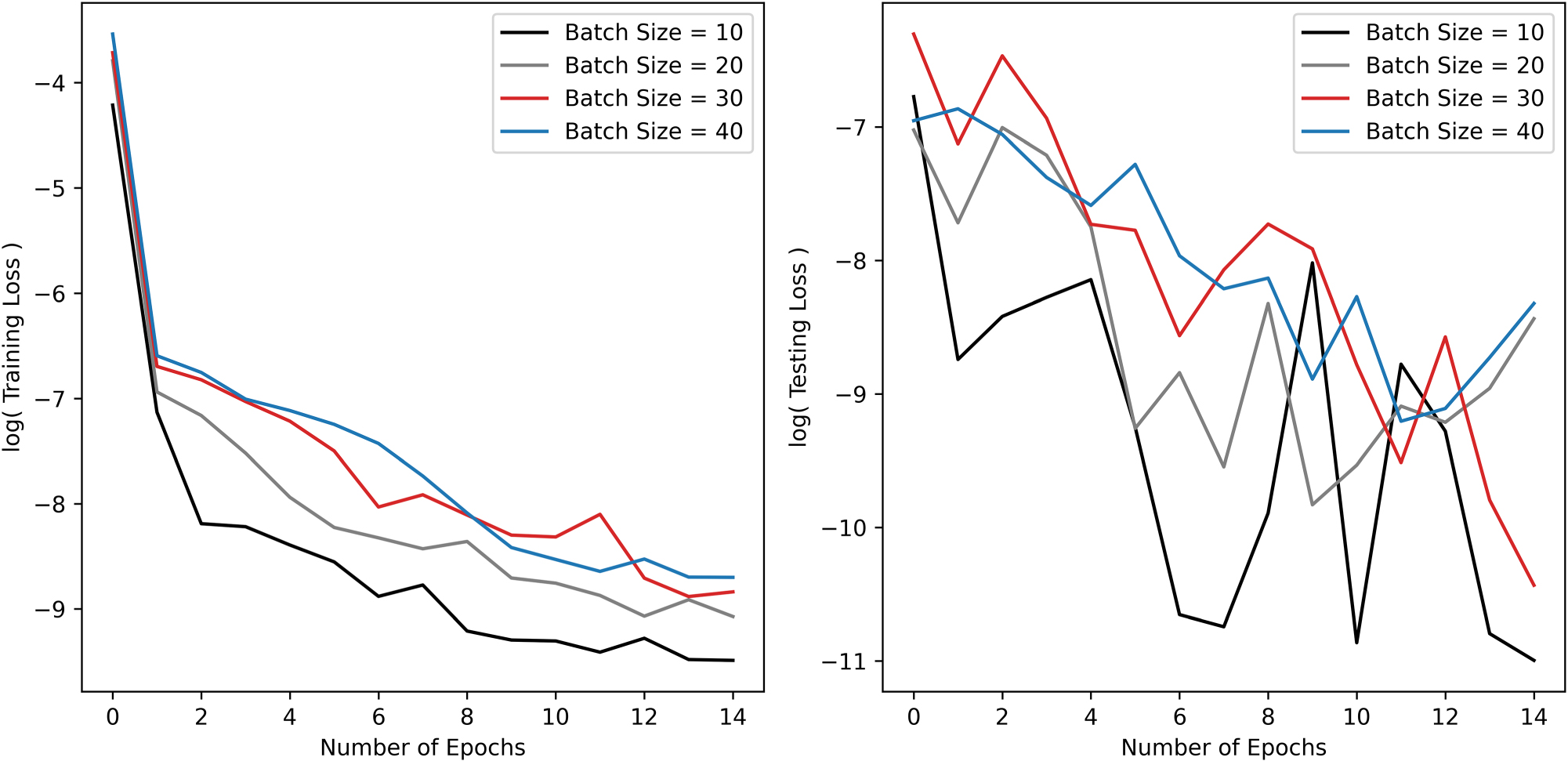

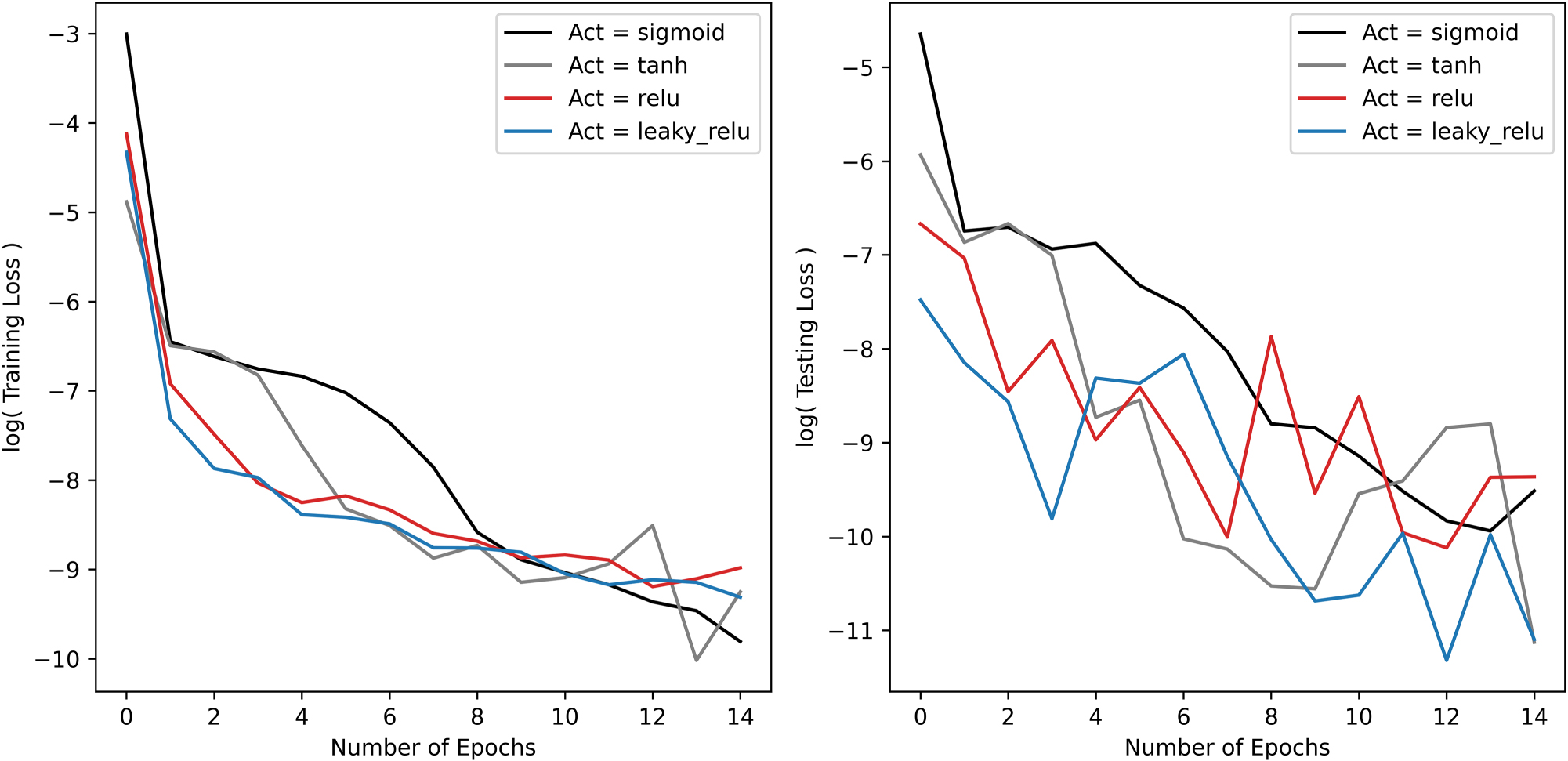

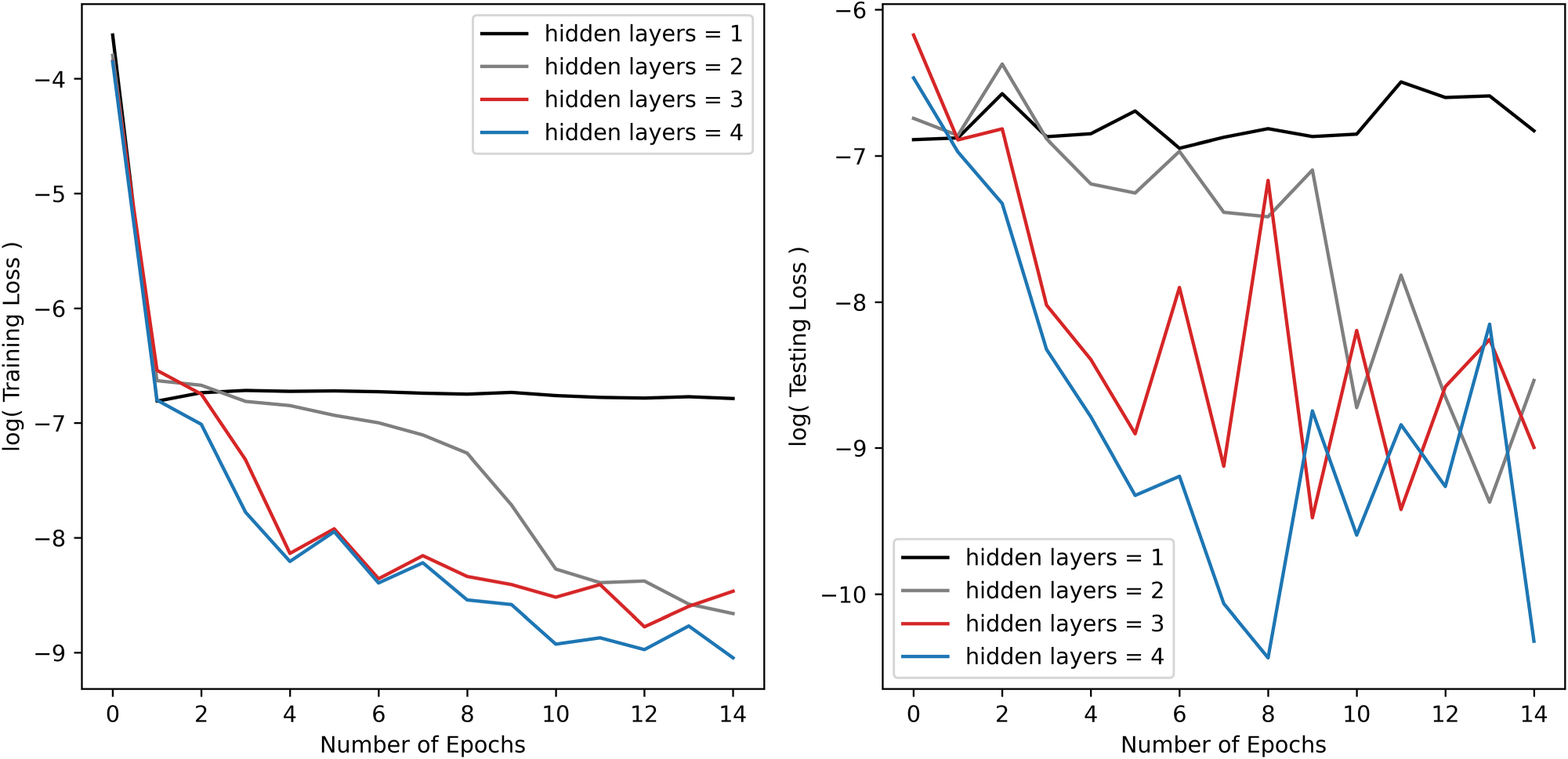

Figures 13–15 show the results of the sensitivity analysis for batch size, activation function, and number of hidden layers, respectively. For all plots, the logarithm of the testing and training loss was taken to better visualize the relative differences between model parameters. The ANN training time was largely insensitive to batch size. Although the loss decreases significantly with fewer epochs, a smaller batch size required more computation as the network parameters were updated more frequently. A batch size of 20 is taken in the final model architecture, as a compromise between number of epochs and speed of training. The ANN was insensitive to activation function and we used the ReLu activation function, R(ζ), in the hidden layers, represented mathematically as:

Sensitivity study on batch size showing its effect on the training and testing MSE loss (Eq. (3)) versus epoch for the Quiet ANN model.

Sensitivity study on activation function showing its effect on the training and testing MSE loss (Eq. (3)) versus epoch for the Quiet ANN model.

Sensitivity study on number of hidden layers showing its effect on the training and testing MSE loss (Eq. (3)) versus epoch for the Quiet ANN model.

The ANN requires 2 hidden layers or greater to accurately model the nonlinear relationship of velocity and spin rate. Once the model is larger than 2 hidden layers it was relatively insensitive to an increasing number of layers. To ensure that the model was able to capture the nonlinear trends, the final model architecture contains 3 hidden layers.

References

Abadi, M., Agarwal, A., Barham, P., Brevdo, E., Chen, Z., Citro, C., Corrado, G.S., Davis, A., Dean, J., and Devin, M. (2016). Tensorflow: large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.04467.Search in Google Scholar

Aguirre-López, M.A., Morales-Castillo, J., Díaz-Hernández, O., Santos, G.J.E., and Almaguer, F.-J. (2018). Trajectories reconstruction of spinning baseball pitches by three-point-based algorithm. Appl. Math. Comput. 319: 2–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2017.01.016.Search in Google Scholar

An, P.-Y. (2024). Sports broadcasting: how big data technology impacts the viewer experience in baseball broadcasting. Eng. Proc. 74, https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2024074060.Search in Google Scholar

Borg, J.P. and Morrissey, M.P. (2014). Aerodynamics of the knuckleball pitch: experimental measurements on slowly rotating baseballs. Am. J. Phys. 82: 921–927, https://doi.org/10.1119/1.4885341.Search in Google Scholar

Collins, H. and Evans, R. (2008). You cannot be serious! public understanding of technology with special reference to “hawk-eye”. Publ. Understand. Sci. 17: 283–308, https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662508093370.Search in Google Scholar

Deshpande, S.K. and Wyner, A. (2017). A hierarchical bayesian model of pitch framing. J. Quant. Anal. Sports 13: 95–112, https://doi.org/10.1515/jqas-2017-0027.Search in Google Scholar

Escalera Santos, G.J., Aguirre-López, M.A., Díaz-Hernández, O., Hueyotl-Zahuantitla, F., Morales-Castillo, J., Almaguer, F. (2019). On the aerodynamic forces on a baseball, with applications. Front. Appl. Math. Statistics 4: 379640, https://doi.org/10.3389/fams.2018.00066.Search in Google Scholar

Fawzi, A., Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.-M., and Frossard, P. (2016). Robustness of classifiers: from adversarial to random noise. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 29.Search in Google Scholar

Fawzi, A., Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.-M., and Frossard, P. (2017). The robustness of deep networks: a geometrical perspective. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 34: 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2017.2740965.Search in Google Scholar

Giordano, N.J. (1996). Computational physics. Prentice Hall, Hoboken, New Jersey.Search in Google Scholar

He, Z., Rakin, A.S., and Fan, D. (2019). Parametric noise injection: trainable randomness to improve deep neural network robustness against adversarial attack. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. Computer Vision Foundation, New York, NY, pp. 588–597.Search in Google Scholar

Healey, G. (2017). The new moneyball: how ballpark sensors are changing baseball. Proc. IEEE 105: 1999–2002, https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2017.2756740.Search in Google Scholar

Higuchi, H. and Kiura, T. (2012). Aerodynamics of knuckle ball: Flow-structure interaction problem on a pitched baseball without spin. J. Fluids Struct. 32: 65–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2012.01.004.Search in Google Scholar

Hintz, E.S. (2022). Moneyball: the computational turn in professional sports management. In: Papers of the business history conference. https://par.nsf.gov/biblio/10346961.Search in Google Scholar

Hsieh, J. (2024). Neural network-based tracking and 3d reconstruction of baseball pitch trajectories from single-view 2d video, https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.16296.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, M.-L. and Li, Y.-Z. (2021). Use of machine learning and deep learning to predict the outcomes of major league baseball matches. Appl. Sci. 11: 4499, https://doi.org/10.3390/app11104499.Search in Google Scholar

Jeong, K.-S., Kim, J.-H., and Han, Y.-H. (2017). A prediction of baseball game results using recurrent neural netowrks. In: Proceedings of the Korea information processing society conference. Korea Information Processing Society, Seoul, South Korea, pp. 873–876.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, J., Ra, M., Lee, H., Kim, J., and Kim, W.-Y. (2019). Precise 3d baseball pitching trajectory estimation using multiple unsynchronized cameras. IEEE Access 7: 166463–166475. https://doi.org/0.1109/ACCESS.2019.2953340.Search in Google Scholar

Kingma, D.P. and Ba, J. (2014). Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980.Search in Google Scholar

Koseler, K. and Stephan, M. (2017). Machine learning applications in baseball: a systematic literature review. Appl. Artif. Intell. 31: 745–763, https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2018.1442991.Search in Google Scholar

Kray, T., Franke, J., and Frank, W. (2014). Magnus effect on a rotating soccer ball at high reynolds numbers. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerod. 124: 46–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jweia.2013.10.010.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, J.S. (2022). Prediction of pitch type and location in baseball using ensemble model of deep neural networks. J. Sports Anal. 8: 115–126, https://doi.org/10.3233/JSA-200559.Search in Google Scholar

Lomax, H., Pulliam, T.H., and Zingg, D.W. (2001). Fundamentals of computational fluid dynamics (scientific computation), 2001st ed. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.Search in Google Scholar

Metropolis, N. and Ulam, S. (1949). The monte carlo method. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 44: 335–341, https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1949.10483310.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Nathan, A.M. (2007). Analysis of pitchf/x pitched baseball trajectories. In: The Physics of Baseball. University of Illinois,Champaign, IL, https://baseball.physics.illinois.edu/Analysis.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Nickels, K. and Hutchinson, S. (2002). Estimating uncertainty in SSD-based feature tracking. Image Vis. Comput. 20: 47–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-8856(01)00076-2.Search in Google Scholar

Park, D.J., Kim, B.W., Jeong, Y.-S., Ahn, C.W., and Jeong, Y.S. (2018). Deep neural network based prediction of daily spectators for korean baseball league: focused on gwangju-kia champions field. Smart Media J. 7: 16–23, https://doi.org/10.30693/SMJ.2018.7.1.16.Search in Google Scholar

Park, J. and Park, S. (2017). A study on prediction of attendance in korean baseball league using artificial neural network. KIPS Trans. Software Data Eng. 6: 565–572, https://doi.org/10.3745/KTSDE.2017.6.12.565.Search in Google Scholar

Rahimian, P. and Toka, L. (2022). Optical tracking in team sports: a survey on player and ball tracking methods in soccer and other team sports. J. Quant. Anal. Sports 18: 35–57, https://doi.org/10.1515/jqas-2020-0088.Search in Google Scholar

Robinson, G. and Robinson, I. (2017). Are inertial forces ever of significance in cricket, golf and other sports? Phys. Scr. 92: 043001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/aa634e.Search in Google Scholar

Rubinstein, R.Y. and Kroese, D.P. (2016). Simulation and the Monte Carlo method. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey.Search in Google Scholar

Santos-Fernandez, E., Wu, P., and Mengersen, K.L. (2019). Bayesian statistics meets sports: a comprehensive review. J. Quant. Anal. Sports 15: 289–312, https://doi.org/10.1515/jqas-2018-0106.Search in Google Scholar

Sayers, A. and Hill, A. (1999). Aerodynamics of a cricket ball. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerod. 79: 169–182, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6105(97)00299-7.Search in Google Scholar

Shum, H. and Komura, T. (2004). A spatiotemporal approach to extract the 3d trajectory of the baseball from a single view video sequence. In: 2004 IEEE International conference on multimedia and expo, 3. IEEE, pp. 1583–1586.Search in Google Scholar

Shum, H. and Komura, T. (2005). Tracking the translational and rotational movement of the ball using high-speed camera movies. In: IEEE International conference on image processing 2005, 3. IEEE, p. III-1084.Search in Google Scholar

Sietsma, J. and Dow, R.J. (1991). Creating artificial neural networks that generalize. Neural Netw. 4: 67–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/0893-6080(91)90033-2.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, L. and Downey, J. (2009). Predicting baseball hall of fame membership using a radial basis function network. J. Quant. Anal. Sports 5, https://doi.org/10.2202/1559-0410.1157.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, A.W. and Smith, B.L. (2021). Using baseball seams to alter a pitch direction: the seam shifted wake. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. - Part P: J. Sports Eng. Technol. 235: 21–28, https://doi.org/10.1177/1754337120961609.Search in Google Scholar

Theobalt, C., Albrecht, I., Haber, J., Magnor, M., and Seidel, H.-P. (2004). Pitching a baseball: tracking high-speed motion with multi-exposure images. In: ACM SIGGRAPH 2004 papers. Association for Computing Machinery, Los Angeles, California, pp. 540–547.Search in Google Scholar

Umemura, K., Yanai, T., and Nagata, Y. (2021). Application of vbgmm for pitch type classification: analysis of trackman’s pitch tracking data. Jpn. J. Stat. Data Sci. 4: 41–71, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42081-020-00079-8.Search in Google Scholar

Weller, E. (2020). The data revolution: an examination of the use of scouting and analytics in major league baseball front offices, https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1306.Search in Google Scholar

Willman, D. (2023). Baseball savant, https://baseballsavant.mlb.com.Search in Google Scholar

Young, W.A., Holland, W.S., and Weckman, G.R. (2008). Determining hall of fame status for major league baseball using an artificial neural network. J. Quant. Anal. Sports 4, https://doi.org/10.2202/1559-0410.1131.Search in Google Scholar

Zou, J., Han, Y., and So, S. (2009). Overview of artificial neural networks. Artif. Neural Net.: Methods Appl.: 14–22, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-101-1_2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2026 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston