Intra-partum and perinatal outcomes in fetuses exhibiting ZigZag pattern on cardiotocography trace: a systematic review and meta-analysis

-

Luca Finadri

, Asma Khalil

, Alessandro Lucidi

, Marco Liberati

Abstract

Objectives

Historically, baseline fetal heart rate variability (FHRV) with an amplitude of greater than 25 beats per minute, and lasting for more than 30 min, was defined as the saltatory pattern. Several experimental animal models have reported an association between saltatory pattern and poor perinatal outcomes. However, recent studies have suggested that the classically defined saltatory pattern is very uncommon during labor, and a new CTG pattern, called the “ZigZag” pattern (ZZP), has been reported. ZZP has been defined as a rapid, erratic repetitive oscillations in the FHR with an amplitude of >25 bpm and has been claimed as a potential marker to identify fetuses at risk of intra-partum and perinatal compromise during labour. A recent international expert consensus has recommended that ZZP persisting for >1 min requires an urgent intervention to avoid poor perinatal outcomes. The aim of the present systematic review was to determine the intra-partum and perinatal outcomes of fetuses with the ZZP compared to the control group not showing the ZZP during labor.

Methods

Medline, Embase and Cochrane databases were searched. Inclusion criteria were studies reporting the intra-partum and perinatal outcome of fetuses showing compared to those not showing ZZP during labour. The outcomes observed were operative vaginal delivery, caesarean section, umbilical artery pH<7.1, base excess <−11, mean pH and base excess, admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), abnormal post-natal brain imaging and occurrence of late decelerations later on the CTG trace. Random-effect meta-analyses were used to combine data and results reported as pooled odd ratios (OR) for categorical and pooled mean differences (MD) for continuous variables with their 95 % confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Six studies (18,136 fetuses) were included. Fetuses showing ZZP on CTG trace during labor had a higher risk of operative vaginal delivery (OR: 2.22, 95 % CI 1.69–2.91; p<0.001), cesarean delivery (OR: 1.71, 95 % CI 1.37–2.15; p<0.001), umbilical artery pH<7.1 (OR: 2.48, 95 % CI 1.56–3.94; p<0.001), Apgar score <7 at 5 min (OR: 2.13, 955 CI 1.05–4.31; p=0.004) and the occurrence of late decelerations later on during labor (OR: 9.51, 95 % CI 7.80–11.61; p<0.001) compared to those not showing this pattern, while there was no difference in the risk of NICU admission (p=0.209) and respiratory support after birth (p=0.755). Likewise, umbilical artery pH was significantly lower in fetuses showing compared to those not showing ZZP during labour (pooled MD: −0.10, 95 % CI −0.11 to −0.09; p<0.001), while there was no difference in the value of mean base excess between the two groups (p=0.156).

Conclusions

Fetuses showing the ZZP on CTG trace during labour are at higher risk of operative vaginal delivery, caesarean section and adverse intrapartum and perinatal outcomes.

Introduction

Cardiotocography (CTG) is a widely utilized tool in obstetrics for monitoring fetal heart rate (FHR) and uterine contractions and was intended to allow clinicians to assess fetal well-being and make timely interventions to prevent adverse outcomes [1]. Since its development in the 1960s, CTG has been widely implemented into clinical practice to help identify potential fetal compromise by providing a detailed information on FHR baseline, variability, accelerations, decelerations, and contraction patterns, each of which can offer insights into fetal oxygenation and health status [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7].

The autonomic nervous system regulates FHR regulation and influences the patterns observed on CTG [8], 9]. While fetal heart rate variability is commonly attributed to a “push-pull” interaction between parasympathetic and beta-sympathetic branches, direct evidence supporting this model remains limited [10]. In an investigation by Dalton et al., autonomic blocking in fetal lambs demonstrated that beta-sympathetic blockade alone did not alter heart rate variability, while parasympathetic blockade reduced, but did not eliminate, variability. Interestingly, dual blockade of both autonomic branches left approximately 35–40 % of heart rate variability intact, implying a significant non-neural component in fetal heart rate modulation [10].

However, CTG interpretation remains challenging, with substantial subjectivity and complexity in assessing patterns, leading to variability in clinical decision-making [6], 11]. These interpretative challenges often result in either false positives, contributing to unnecessary interventions like operative vaginal delivery or emergency cesarean sections, potentially impacting neonatal outcomes [7], 12]. To address these limitations, recent efforts have focused on standardizing interpretation guidelines, which may improve both diagnostic accuracy and consistency in fetal monitoring [4], 7], [13], [14], [15].

Traditionally, a FHRV greater than 25 beats per minute lasting more than 30 min, was defined as saltatory pattern, is considered to carry an increased risk of poor perinatal outcomes [16], [17], [18]. However, recent studies have reported that the classically defined saltatory pattern is uncommon during labor and there is no is no international consensus yet regarding its definition, duration, interpretation and management [19].

More recently, a new CTG pattern, the “ZigZag” pattern (ZZP), has been reported and defined as a rapid, erratic, repetitive oscillations in the FHR baseline, most of the times at a variability above 25 bpm for at least 1 min [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. This pattern has garnered attention for its potential association with fetal hypoxia and metabolic acidosis, conditions that warrant close monitoring and often requiring an urgent clinical intervention to improve fetal oxygenation [22], [23], [24], [25]. Despite its potential clinical relevance, the ZZP remains a controversial marker due to limited consensus on its diagnostic accuracy and specificity. Some studies suggest that the ZZP reliably signals rapidly evolving hypoxic episodes, while others note its appearance in non-pathological scenarios, complicating its use as a definitive marker of fetal compromise [17], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26, 29], 30]. Therefore, the ZZP may represent an important sign fetal compromise both during a rapidly evolving hypoxic stress, and in fetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS), as well as when there is a transfer of inflammatory cytokines from the maternal environment.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to report the intra-partum and perinatal outcomes of fetuses with ZZP compared to those not showing ZZP during labor.

Methods

Protocol, information sources and literature search

This review was performed according to an a-priori designed protocol and recommended for systematic reviews and meta-analysis [31], [32], [33]. Medline, Embase and Cochrane databases were searched electronically on the 10/09/2024 utilizing combinations of the relevant medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, key words, and word variants for “ZigZag”, “Saltatory” patterns, “increased variability” and “outcome”. The search and selection criteria were restricted to the English language. Reference lists of relevant articles and reviews were hand-searched for additional reports. The PRISMA guidelines were followed [34].

Outcomes measures, study selection and data collection

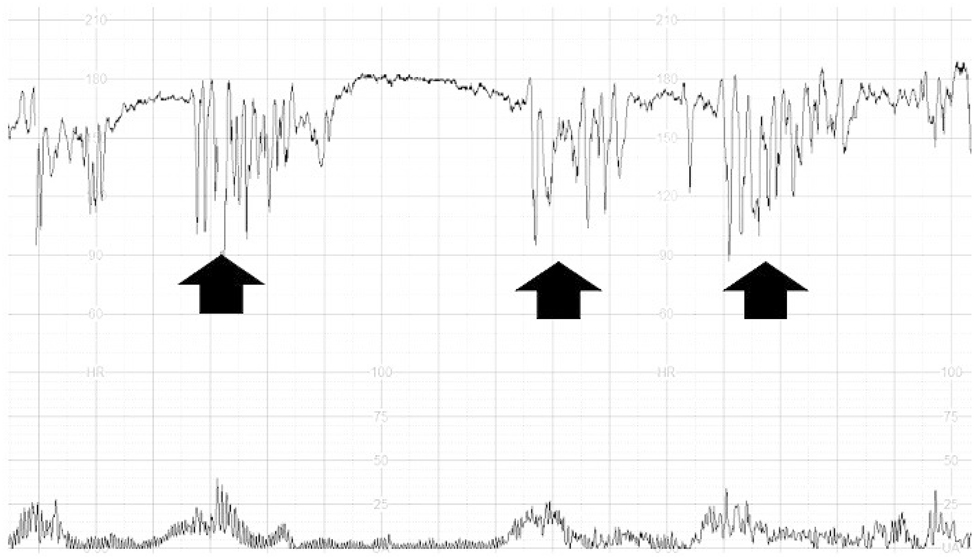

We included studies reporting the intra-partum and perinatal outcome of fetuses showing compared to those not showing ZZP, defined as a rapid, repetitive oscillations in the FHR baseline, most of the times at a variability above 25bpm for at least 1 min, at CTG trace during labour (Figure 1).

Zig-Zag pattern on a CTG trace during labour.

The outcomes observed were:

Operative vaginal delivery

Caesarean delivery

Umbilical artery pH<7.1

Base excess <−11

Mean pH and base excess

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)

Abnormal post-natal brain imaging, defined as the presence of intra-ventricular haemorrhage or periventricular leukomalacia or at post-natal imaging

Occurrence of late decelerations later on the CTG trace

We also reported the distribution of different pregnancy and fetal characteristics including:

Maternal age

Gestational age at birth

Nulliparity

Spontaneous or induced labor

Term pregnancies

Prolonged or post-term pregnancies, defined as pregnancies progressing beyond 41 and 42 weeks of gestation respectively

Data extraction, quality assessment, risk of bias and statistical analysis

Two independent investigators (LF, GO) selected studies in two stages. The abstracts of all potentially relevant papers were examined individually for suitability. Papers were excluded at this stage only if they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining papers were obtained in full text and were assessed independently for content, data extraction and analysis. Disagreements between the two original reviewers were resolved by discussion with a third investigator (FDA). Study characteristics were extracted using a predesigned data extraction protocol. If more than one study was published on the same cohort with identical endpoints, the report containing the most comprehensive information on the population was included to avoid overlapping populations.

Only full-text articles were considered eligible for inclusion. Studies not reporting the comparison between fetuses showing and those not showing ZZP on CTG trace during labour, those including only the role of CTG in specific pregnancy complications (such as those affected by infection or medical conditions complicating pregnancy) and those not reporting the occurrence of the observed outcomes were excluded. Case reports, conference abstracts and case series with<10 cases were also excluded to avoid publication bias. We excluded studies published before 2010 because we think that advances in the comprehension of CTG trace during labour make them less relevant.

Quality assessment of the included studies was performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for case-control studies [35]. According to NOS, each study is judged on three broad perspectives: the selection of the study groups; the comparability of the groups; and the ascertainment of the outcome of interest.

Random-effect meta-analyses were used to combine data and results reported as pooled odd ratios (OR) and pooled mean differences (MD) for categorical continuous variables respectively [36], 37]. Funnel plots displaying the outcome rate from individual studies vs. their precision (1/standard error) were carried out with an exploratory aim, but were not used when the total number of publications included for each outcome was less than 10. In this case, the power of the tests is too low to distinguish chance from real asymmetry [37].

Between-study heterogeneity was explored using the I2 statistic, which represents the percentage of between-study variation that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. All analyses were performed using StatsDirect Statistical Software (StatsDirect Ltd Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

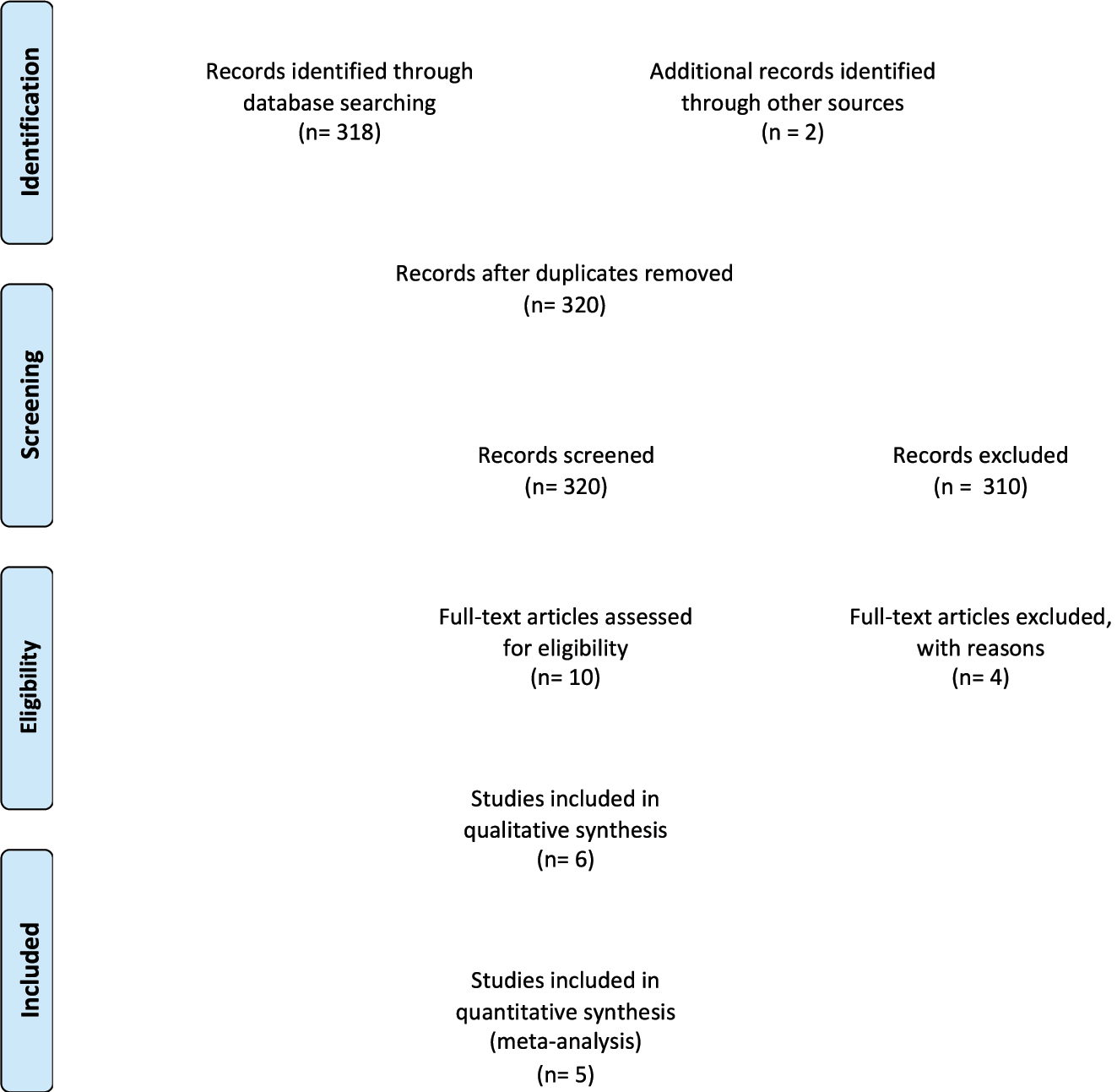

The literature search identified 320 articles, 10 of which were assessed for eligibility for inclusion, and six studies were included in the systematic review (Table 1, Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1) [19], [21], [22], [23], [24, 30]. These six studies included (after removing the studies including overlapped cases) 18,136 fetuses.

General characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review.

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | Period considered | Inclusion criteria | Inclusion of pregnancies complicated by placental insufficiency or pre-eclampsia | Definition of Zig-Zag pattern | Primary outcome | Pregnancies (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loussert [21] | 2022 | France | Prospective | 2019 | All pregnancies ≥37 weeks | Yes | Definition of marked variability: variability greater than 25 beats per minute, with a minimum duration of 1 min | Neonatal acidosis | 4,394 |

| Tarvonen [24] | 2020 | Finland | Retrospective | 2012 | Pregnancies >33 weeks of gestation | Yes | FHR baseline amplitude changes of >25 bpm with a duration of 2–30 min | Umbilical artery (UA) blood gases, Apgar scores, neonatal respiratory distress, and neonatal encephalopathy | 5,150 |

| Tarvonen [25] | 2020 | Finland | Retrospective case control | 2012 | Pregnancies >33 weeks of gestation | Yes | Definition of saltatory pattern: FHR baseline amplitude changes of >25 bpm with an oscillatory frequency of >6/min with a minimum duration of 2 min | pH, base excess, pO2 and erythropoietin on umbilical cord | 245 |

| Gracia-Perez-Bonfils [30] | 2020 | Spain | Retrospective cohort | 2020 | Pregnancies in patients with symptomatic COVID-19 infection | Yes | Variability >25 bpm during 1 min or more | Apgar score at 5 min and umbilical cord pH | 12 |

| Gracia-Perez-Bonfils [19] | 2019 | United Kingdom | Retrospective | 2018–2019 | Singleton term pregnancies between 37 and 42 weeks of gestation | No | Variability >25 bpm during 1 min or more | Apgar scores, umbilical cord pH values and admission to NICU | 500 |

| Polnaszek [23] | 2019 | United States | Prospective cohort | 2010–2015 | All pregnancies ≥37 weeks | No | Definition of marked variability: fluctuations in FHR amplitude of >25 beats per minute based on 10-min epochs | Neonatal morbidity and abnormal arterial cord gases | 8,580 |

Prisma flow-diagram.

The results of the quality assessment of the included studies using the NOS scale are presented in Table 2. Most of the included studies showed an overall moderate score regarding the selection and comparability of study groups, and for ascertainment of the outcome of interest. The main weaknesses of these studies were their retrospective design, and heterogeneity of outcomes observed.

Methodological assessment of included studies based on Newcastle – Ottawa Score (NOS).

| Author | Year | Selection | Comparability | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loussert | 2023 | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ |

| Tarvonen | 2023 | ★★ | ★ | ★★ |

| Gracia-Perez-Bonfils | 2023 | ★★ | ★★ | ★★ |

| Gracia-Perez-Bonfils | 2023 | ★★ | ★ | ★★ |

| Tarvonen | 2022 | ★★ | ★★ | ★★ |

| Polnaszek | 2022 | ★★ | ★★ | ★★ |

Synthesis of the results

When comparing the maternal and pregnancy characteristics, there was no difference in maternal age (p=0.878) and term labor between cases showing and those not showing ZZP on CTG. Conversely, there was a higher prevalence of nulliparity (p<0.001), prolonged or post-term pregnancies (p<0.001) and women undergoing induction of labor (p=0.002) between women showing compared to those not showing ZZP at CTG assessment during labor (Table 3).

Odd ratios and mean differences for the different maternal and pregnancy characteristics in the present systematic review in fetuses presenting compared to those not present ZZP at CTG during labor (95 % CI between parantheses).

| Categorical variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Studies | Patients (n/N vs. n/N) | Pooled odd ratio (95 % CI | I2 (%) | p-Value |

| Nulliparity | 3 | 750/1,149 vs. 7,727/16,975 | 2.40 (1.63–2.56) | 65.4 | <0.001 |

| Spontaneous labor | 3 | 734/1,149 vs. 11,090/16,975 | 0.78 (0.68–0.89) | 0 | 0.002 |

| Induced labor | 3 | 415/1,149 vs. 5,585/16,975 | 1.28 (1.13–1.46) | 0 | 0.002 |

| Term labor | 3 | 0/1,149 vs. 16,415/16,975 | 0.01 (0.001–1.79) | 0 | 0.078 |

| Post-term labor | 2 | 84/972 vs. 398/12,758 | 1.76 (1.37–2.28) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Continuous variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Raw mean (patients) | Pooled mean difference (95 % CI) | I2 (%) | p-Value | |

| Maternal age | 3 | 29.97 ± 3.93 (1,149) vs. 30.07 ± 3.70 (16,975) | −0.093 (−1.28 to 1.095) | 97.23 | 0.878 |

| Gestational age at birth | 3 | 39.90 ± 1.27 (1,149) vs. 39.50 ± 1.13 (16,975) | 0.363 (0.13 to 0.60) | 92.93 | 0.003 |

Fetuses showing ZZP on CTG trace during labor had a higher risk of operative vaginal delivery (OR: 2.22, 95 % CI 1.69–2.91; p<0.001), cesarean delivery (OR: 1.71, 95 % CI 1.37–2.15; p<0.001), umbilical artery pH<7.1 (OR: 2.48, 95 % CI 1.56–3.94; p<0.001), Apgar score <7 at 5 min (OR: 2.13, 955 CI 1.05–4.31; p=0.004) and the occurrence of late decelerations later on during labor (OR: 9.51, 95 % CI 7.80–11.61; p<0.001) compared to those not showing this pattern, while there was no difference in the risk of NICU admission (p=0.209) and respiratory support after birth (p=0.755), while it was not possible to performed a comprehensive pooled data synthesis for abnormal brain imaging as only one study reported this outcome (Table 4). When considering the continuous variables, umbilical artery pH was significantly lower in fetuses showing compared to those not showing ZZP during labour (pooled MD: −0.10, 95 % CI −0.11 to −0.09; p<0.001), while there was no difference in the value of mean base excess between the two groups (p=0.156) (Table 4).

Pooled odd ratios and mean differences (95 % CI) for the different maternal and perinatal outcomes.

| Categorical outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Studies | Fetuses (n/N vs. n/N) | Pooled OR (95 % CI) | I2, % | p-Value |

| Operative vaginal delivery | 2 | 93/567 vs. 370/12,407 | 2.22 (1.69–2.91) | 23.2 | <0.001 |

| Cesarean section | 2 | 109/421 vs. 1,398/8,353 | 1.71 (1.37–2.15) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Umbilical artery pH<7.1 | 3 | 49/717 vs. 386/12,757 | 2.48 (1.56–3.94) | 39.6 | <0.001 |

| Apgar score<7 at 5 min | 4 | 36/748 vs. 281/12,920 | 2.13 (1.05–4.31) | 56.1 | 0.004 |

| Respiratory support or intubation | 2 | 29/567 vs. 637/12,407 | 0.67 (0.05–8.38) | 94.2 | 0.755 |

| Admission to NICU | 2 | 21/327 vs. 148/4,576 | 3.14 (0.53–18.69) | 85.7 | 0.209 |

| Abnormal brain imaging | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Late decelerations occurring later on the CTG trace | 2 | 542/759 vs. 2,044/8,785 | 9.51 (7.80–11.61) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Continuous outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Raw mean (patients) | Pooled mean difference (95 % CI) | I2, % | p-Value | |

| pH | 3 | 7.19 ± 0.07 (571) vs. 7.23 ± 0.12 (8,703) | −0.10 (−0.11 to −0.094) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Base excess | 2 | −8.08 ± 4.05 (421) vs. −6.24 ± 2.75 (8,353) | 1.75 (−0.67 to 4.16) | 92.3 | 0.156 |

Discussion

Summary of the main findings

The findings from this systematic review showed that fetuses showing ZZPon CTG trace during labor had a higher risk of operative vaginal delivery, cesarean section, abnormal Apgar score, pH<7.1 compared to those not showing this pattern during labour. The observed increase in the ZZP in post-term fetuses (p<0.001) who have reduced placental reserves and increased likelihood of umbilical cord compression due to relative reduction in amniotic fluid volume, and in fetuses who were exposed to induction of labor (p=0.002), supports the hypothesis that ZZP reflects a rapidly evolving hypoxic stress. This is because increased umbilical cord compression and reduced utero-placental insufficiency in the former and increased uterine activity in the latter would increase the likelihood of a rapidly evolving hypoxic stress in late first or second stage of labor, leading to the onset of ZZP on the CTG trace.

Comparison with other systematic reviews, strengths and limitations

The multitude of outcomes observed, and thorough literature search are main strengths of the present systematic review, while the small number of included cases, retrospective study design and lack of standardised criteria for intra-partum management in case of ZZP represents its main weaknesses. Furthermore, some maternal and pregnancy characteristics were unbalanced between the two different study groups, including nulliparity, induction of labour and post-term pregnancies, thus potentially representing a source of bias for the reported results.

Clinical and research implications

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) and the FIGO classification system [4], 7], 14] for CTG was developed to standardize the interpretation of FHR patterns during labor, grouping tracings into three primary categories based on specific criteria:

Category I (FIGO=Normal): Patterns with a low risk of hypoxia, typically requiring no intervention.

Category II (FIGO=Suspicious): Patterns that are inconclusive and warrant closer monitoring.

Category III (FIGO=Pathological): Patterns with a high likelihood of fetal hypoxia, necessitating prompt intervention.

While these frameworks support labor management by establishing universal categories, these categories, being too rigid, may overlook the complexity of individual cases. For example, a growth restricted fetus may not have sufficient physiological reserves to be rigidly classified into these “fixed categories”. However, exposure to chronic utero-placental insufficiency or an intraamniotic inflammation and/or chorioamnionitis may lead to multiple pathways of compromise. More importantly, its focus on technical criteria can limit a deeper understanding of the underlying pathophysiology, as it does not differentiate the causes of FHR variations or consider fetal adaptation to potentially hypoxic stress. This limitation may restrict clinicians’ insights into the physiological context of specific FHR patterns. These classification systems also do not address features of fetal inflammation, and therefore, may have some limitations when interpreting atypical patterns that do not fit neatly within these three categories.

The Saltatory pattern, for instance, has historically remained a controversial and poorly understood entity, with no established consensus on its pathophysiology and management. The saltatory pattern, as defined by FIGO guideline has been reported to occur rarely during labour. More recently, a new CTG feature during labor, the ZZP, which has been defined as a rapid, erratic, oscillations in FHRV with an amplitude of >25 bpm has been reported to be a transient sign suggesting a higher risk of fetal hypoxemia and/or an ongoing fetal inflammation. Recently, an international expert consensus has provided the definition and the maximum duration of the ZZP to be considered as abnormal [3]. Furthermore, the interpretation tools recommended by this international expert consensus panel classify the CTG traces based on the types of hypoxia and fetal inflammation and have included the ZZP both in subacute hypoxia (rapidly evolving hypoxic stress) and in chorioamnionitis (neuroinflammation).

Although the pathophysiology of ZZP has not been clearly described yet, it is likely to reflect a disordered or hyperactive autonomic response potentially triggered by rapidly evolving hypoxia or acidosis. When hypoxia progresses quickly, the fetus may not maintain baseline heart rate long enough to oxygenate critical organs, leading to erratic sympathovagal responses aimed at balancing oxygen delivery and cerebral perfusion. The sympathetic nervous system rapidly attempts to increase the FHR to obtain oxygenated blood while the parasympathetic nervous system tries to reduce the heart rate to protect the myocardial workload. This autonomic imbalance, likely caused by a sudden drop in oxygenation or acidosis, produces the pronounced FHR fluctuations seen as the ZZP, signalling that the fetus’s regulatory system may be under strain.

This rapid increase and decrease in the FHR may be seen on the CTG as variability exceeding 25 bpm in a shape of an irregular ZZP, defined by many authors as variability >25 bpm lasting at least 1 min. The appearance of this pattern during labor may represent an early sign of fetal hypoxia or acidosis, particularly when accompanied by other concerning signs, such as decreased long-term variability or late decelerations. A recent study has concluded that in the presence of features of fetal neuroinflammation on the CTG tracer which includes the ZZP, the levels of IL-6 in the umbilical cord, which is a marker of ongoing fetal inflammation is increased approximately 4-fold [29]. Moreover, it has been shown that injection of boluses of LPS (bacterial toxins) in sheep was associated with increased fetal heart rate variability, which also coincided with episodes of fetal hypotension [37]. Therefore, ZZP in chorioamnionitis may signify a late stage in fetal inflammatory response, requiring an urgent intervention.

We have reported a higher risk of operative delivery, abnormal Apgar score and umbilical artery pH in fetuses showing compared to those not showing ZZP during labour, thus highlighting the potential role of such sign in identifying fetuses at higher risk of progressive hypoxemia and acidosis.

Identification of fetuses exposed to a rapidly evolving hypoxic stress during labour is crucial as potential interventions, stopping the oxytocic drugs, administration of tocolytics, and intra-venous fluids if appropriate, cessation of active maternal pushing and changing maternal position, may help restore fetal oxygenation. This may not only help avoid poor perinatal outcomes due to the progression of the rapidly evolving fetal hypoxemia leading to fetal metabolic acidosis., but also unnecessary intrapartum operative interventions by normalising the CTG trace. Therefore, our systematic review, first in our best knowledge which determined the association between the ZZP and perinatal outcomes may have important clinical impact and help modify clinical practice.

Conclusions

Fetuses showing ZZP during labour are at higher risk of operative vaginal delivery, caesarean section and adverse intrapartum and perinatal outcome. The results from this study support the use of the ZZP as a sign for fetal compromise during labour. However, we acknowledge that further large studies showing objective shared protocols for intrapartum management of fetuses with ZZP and including homogenous populations of women are needed to support the emerging consensus that ZZP is an important marker for subsequent adverse perinatal outcomes.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable, as this a systematic review of published studies.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: F. D’Antonio, L. Finadri. Data curation: F. D’Antonio, L. Finadri. Writing – original draft: F. D’Antonio, L. Finadri. Writing – review and editing: Asma Khalil, Ilenia Mappa, Giuseppe Rizzo, Alessandro Lucidi, Marco Liberati, Edwin Chandraharan. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Data available on request.

References

1. Steer, PJ. Has electronic fetal heart rate monitoring made a difference. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2008;13:2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2007.09.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Chudácek, V, Spilka, J, Lhotská, L, Janku, P, Koucký, M, Huptych, M, et al.. Assessment of features for automatic CTG analysis based on expert annotation. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2011;2011:6051–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/iembs.2011.6091495.Search in Google Scholar

3. Chandraharan, E, Pereira, S, Ghi, T, Gracia Perez-Bonfils, A, Fieni, S, Jia, YJ, et al.. International expert consensus statement on physiological interpretation of cardiotocograph (CTG): first revision (2024). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2024;302:346–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2024.09.034.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Ayres-de-Campos, D, Spong, CY, Chandraharan, E. FIGO Intrapartum Fetal Monitoring Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO Intrapartum Fetal Monitoring Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on intrapartum fetal monitoring: cardiotocography. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Zanardo, V, Straface, G. Intrapartum cardiotocography. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024;231:e114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2024.05.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Hernandez Engelhart, C, Gundro Brurberg, K, Aanstad, KJ, Pay, ASD, Kaasen, A, Blix, E, et al.. Reliability and agreement in intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring interpretation: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2023;102:970–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14591.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. FIGO. Guidelines for the use of fetal monitoring. Int J Gynecol Obstet 1986;25:159–67.Search in Google Scholar

8. Schneider, U, Bode, F, Schmidt, A, Nowack, S, Rudolph, A, Dölker, EM, et al.. Developmental milestones of the autonomic nervous system revealed via longitudinal monitoring of fetal heart rate variability. PLoS One 2018;13:e0200799. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200799.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Assali, NS, Brinkman, CR3rd, Woods, JRJr, Dandavino, A, Nuwayhid, B. Development of neurohumoral control of fetal, neonatal, and adult cardiovascular functions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1977;129:748–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(77)90393-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Dalton, KJ, Dawes, GS, Patrick, JE. The autonomic nervous system and fetal heart rate variability. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1983;146:456–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(83)90828-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Thellesen, L, Bergholt, T, Sorensen, JL, Rosthoej, S, Hvidman, L, Eskenazi, B, et al.. The impact of a national cardiotocography education program on neonatal and maternal outcomes: a historical cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2019;98:1258–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13666.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Arnold, JJ, Gawrys, BL. Intrapartum fetal monitoring. Am Fam Physician 2020;102:158–67.Search in Google Scholar

13. Rei, M, Tavares, S, Pinto, P, Machado, AP, Monteiro, S, Costa, A, et al.. Interobserver agreement in CTG interpretation using the 2015 FIGO guidelines for intrapartum fetal monitoring. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016;205:27–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.08.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 106. Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:192–202.10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181aef106Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Chandraharan, E, Pereira, S, Ghi, T, Gracia Perez-Bonfils, A, Fieni, S, Jia, YJ, et al.. International expert consensus statement on physiological interpretation of cardiotocograph (CTG): first revision (2024). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2024;302:346–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2024.09.034.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Di Pasquo, E, Fieni, S, Chandraharan, E, Dall’Asta, A, Morganelli, G, Spinelli, M, et al.. Correlation between intrapartum CTG findings and interleukin-6 levels in the umbilical cord arterial blood: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2024;294:128–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2024.01.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Magawa, S, Lear, CA, Beacom, MJ, King, VJ, Kasai, M, Galinsky, R, et al.. Fetal heart rate variability is a biomarker of rapid but not progressive exacerbation of inflammation in preterm fetal sheep. Sci Rep 2022;12:1771. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05799-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Nunes, I, Ayres-de-Campos, D, Kwee, A, Rosén, KGR. Prolonged saltatory fetal heart rate pattern leading to newborn metabolic acidosis. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2014;41:507–11. https://doi.org/10.12891/ceog17322014.Search in Google Scholar

19. Gracia-Perez-Bonfils, A, Vigneswaran, K, Cuadras, D, Chandraharan, E. Does the saltatory pattern on cardiotocograph (CTG) trace really exist? The ZigZag pattern as an alternative definition and its correlation with perinatal outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2021;34:3537–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2019.1686475.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Galli, L, Dall’Asta, A, Whelehan, V, Archer, A, Chandraharan, E. Intrapartum cardiotocography patterns observed in suspected clinical and subclinical chorioamnionitis in term fetuses. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2019;45:2343–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.14133.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Loussert, L, Berveiller, P, Magadoux, A, Allouche, M, Vayssiere, C, Garabedian, C, et al.. Association between marked fetal heart rate variability and neonatal acidosis: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2023;130:407–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17345.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Nunes, I, Ayres-de-Campos, D, Kwee, A, Rosén, KG. Prolonged saltatory fetal heart rate pattern leading to newborn metabolic acidosis. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2014;41:507–11. https://doi.org/10.12891/ceog17322014.Search in Google Scholar

23. Polnaszek, B, López, JD, Clark, R, Raghuraman, N, Macones, GA, Cahill, AG. Marked variability in intrapartum electronic fetal heart rate patterns: association with neonatal morbidity and abnormal arterial cord gas. J Perinatol 2020;40:56–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0520-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Tarvonen, M, Sainio, S, Hämäläinen, E, Hiilesmaa, V, Andersson, S, Teramo, K. Saltatory pattern of fetal heart rate during labor is a sign of fetal hypoxia. Neonatology 2020;117:111–17. https://doi.org/10.1159/000504941.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Tarvonen, M, Hovi, P, Sainio, S, Vuorela, P, Andersson, S, Teramo, K. Factors associated with intrapartum ZigZag pattern of fetal heart rate: a retrospective one-year cohort study of 5150 singleton childbirths. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2021;258:118–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.12.056.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Blix, E, Maude, R, Hals, E, Kisa, S, Karlsen, E, Nohr, EA, et al.. Intermittent auscultation fetal monitoring during labour: a systematic scoping review to identify methods, effects, and accuracy. PLoS One 2019;14:e0219573. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219573.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Tarvonen, MJ, Lear, CA, Andersson, S, Gunn, AJ, Teramo, KA. Increased variability of fetal heart rate during labour: a review of preclinical and clinical studies. BJOG 2022;129:2070–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17234.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Sukumaran, S, Pereira, V, Mallur, S, Chandraharan, E. Cardiotocograph (CTG) changes and maternal and neonatal outcomes in chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis confirmed on histopathology. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2021;260:183–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.03.029.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Di Pasquo, E, Fieni, S, Chandraharan, E, Dall’Asta, A, Morganelli, G, Spinelli, M, et al.. Correlation between intrapartum CTG findings and interleukin-6 levels in the umbilical cord arterial blood: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2024;294:128–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2024.01.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Gracia-Perez-Bonfils, A, Martinez-Perez, O, Llurba, E, Chandraharan, E. Fetal heart rate changes on the cardiotocograph trace secondary to maternal COVID-19 infection. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;252:286–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.06.049.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Henderson, LK, Craig, JC, Willis, NS, Tovey, D, Webster, AC. How to write a Cochrane systematic review. Nephrology (Carlton) 2010;15:617–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01380.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York (UK): University of York; 2009. Available at: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

33. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al.. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;134:103–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta- analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.Search in Google Scholar

35. Manzoli, L, De Vito, C, Salanti, G, D’Addario, M, Villari, P, Ioannidis, JP. Meta-analysis of the immunogenicity and tolerability of pandemic influenza A 2009 (H1N1) vaccines. PLoS One 2011;6:e24384. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024384.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Hunter, JP, Saratzis, A, Sutton, AJ, Boucher, RH, Sayers, RD, Bown, MJ. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:897–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Lear, CA, Davidson, JO, Booth, LC, Wassink, G, Galinsky, R, Drury, PP, et al.. Biphasic changes in fetal heart rate variability in preterm fetal sheep developing hypotension after acute on chronic lipopolysaccharide exposure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2014;307:R387–95. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00110.2014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2025-0279).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.