Compound heterozygous ROBO1 gene variants in a neonate with congenital hypopituitarism, dysmorphic features and midline abnormalities: a case report and review of the literature

-

Panagiota Markopoulou

, Amalia Sertedaki

, Eirini Nikaina

Abstract

Objectives

The majority of congenital hypopituitarism (CH) cases remain genetically unexplained. The transmembrane receptor Roundabout-1 (ROBO1), activated through interaction with SLIT-family proteins, plays crucial role in axonal guidance, branching, targeting, and midline axonal crossing. ROBO1 variants have been associated with pituitary stalk interruption syndrome and highly variable pituitary-phenotypes, ranging from isolated growth hormone deficiency (IGHD) to combined pituitary hormone deficiency (CPHD). This study aimed to investigate the genetic basis of CH in a newborn and to review current evidence linking ROBO1 variants with CH.

Case presentation

We report the presence of two ROBO1 variants in compound heterozygosity, the NM_002941:c.2914G>A, p.(Ala972Thr) and the novel NM_002941:c.3757G>A, p.(Val1253Met), as well as the identification of the novel NOTCH3 variant NM_000435:c.1505C>T, p.(Ser502Phe) and the novel GPR161 variant NM_001375883.1:c.1117C>T, p.(His373Tyr), in a newborn with CPHD, dysmorphic features and midline abnormalities.

Conclusions

This case, together with accumulating evidence, supports ROBO1 as a potential causative gene for CH. ROBO1 should be considered during genetic evaluation of patients with CH and midline abnormalities. The co-occurrence of NOTCH3 and GPR161 variants raises the possibility of an oligogenic or multigenic etiology. The cross-talk between ROBO/SLIT and NOTCH signaling pathways may contribute to the complex phenotype observed and warrants further functional investigation.

Introduction

The pituitary gland, known as “the master gland”, is the central endocrine regulator of growth, metabolism, reproduction, response to stress and homeostasis [1]. Congenital hypopituitarism (CH) is characterized as the deficiency of one or more of the hormones produced by the anterior or the posterior pituitary [1]. The most common deficiency in patients with CH is growth hormone deficiency (GHD), either isolated (IGHD) or as part of combined pituitary hormone deficiency (CPHD) [2], 3]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that CH is a complex disorder with great heterogeneity, related to highly variable clinical phenotypes [2], 4], 5]. Its incidence is estimated between 1 in 4,000 and 1 in 10,000 live births [2], and its etiology might be either genetic or acquired [6].

CH may result from developmental defects of the pituitary gland and may be associated with extrapituitary congenital anomalies, such as craniofacial, midline structural brain and/or eye abnormalities, usually due to various gene pathogenic variants. On neuroimaging, the pituitary gland may appear normal; however, in some patients, anterior pituitary hypoplasia, ectopic posterior pituitary, hypoplastic or absent pituitary stalk, and agenesis of the corpus callosum have been identified [4], 7]. Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome (PSIS) is a key structural abnormality associated with CH. It is characterized by a thin or absent pituitary stalk, ectopic or absent posterior pituitary, and hypoplasia or aplasia of the anterior pituitary [8], 9]. PSIS is often linked to multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies and may present with variable phenotypic features, including midline defects and ocular anomalies [7], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14].

To date, pathogenic variants in more than 40 genes have been identified in patients with CH, with PROP1 gene variants being the most frequent cause of both familial and sporadic cases [2]. Less frequently, genetic mutations in transcription factors involved in the early stages of pituitary development/ontogenesis, such as HESX1, LHX3, LHX4, SOX3, GLI2, and OTX2, are associated with syndromic features, with or without additional structural abnormalities, including PSIS, septo-optic dysplasia (SOD), and holoprosencephaly (HPE). Among these, ROBO1, a gene involved in axonal guidance and midline crossing, has been recently linked to PSIS, supporting its potential involvement in the genetic aetiology of CH [7], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. The implementation of next generation sequencing (NGS) methodologies has facilitated the identification of novel genes expressed during the development of the head, hypothalamus and/or pituitary. However, the genetic diagnosis rate in CH remains low, with the majority of cases (approximately 85 %) still lacking an identified genetic cause [4], 7].

In this article, we present the case of a newborn with CH who was identified by Exome Sequencing (ES) as a compound heterozygote for ROBO1 variants.

Case presentation

A male (46, XY) neonate, the second child of non-consanguineous Greek parents, was delivered by caesarean section at 37 weeks of gestation, with a birth weight of 3,220 g (appropriate for gestational age), a length of 49 cm, and a head circumference of 36.5 cm. Prenatal ultrasound revealed no specific findings, except for micrognathia. The family history of the patient was unremarkable; both parents and the patient’s female sibling exhibited normal stature, no signs of gonadotropic deficiency, normal thyroid function, and no dysmorphic features. After birth, the neonate was admitted to our Neonatology Unit for further evaluation due to congenital abnormalities.

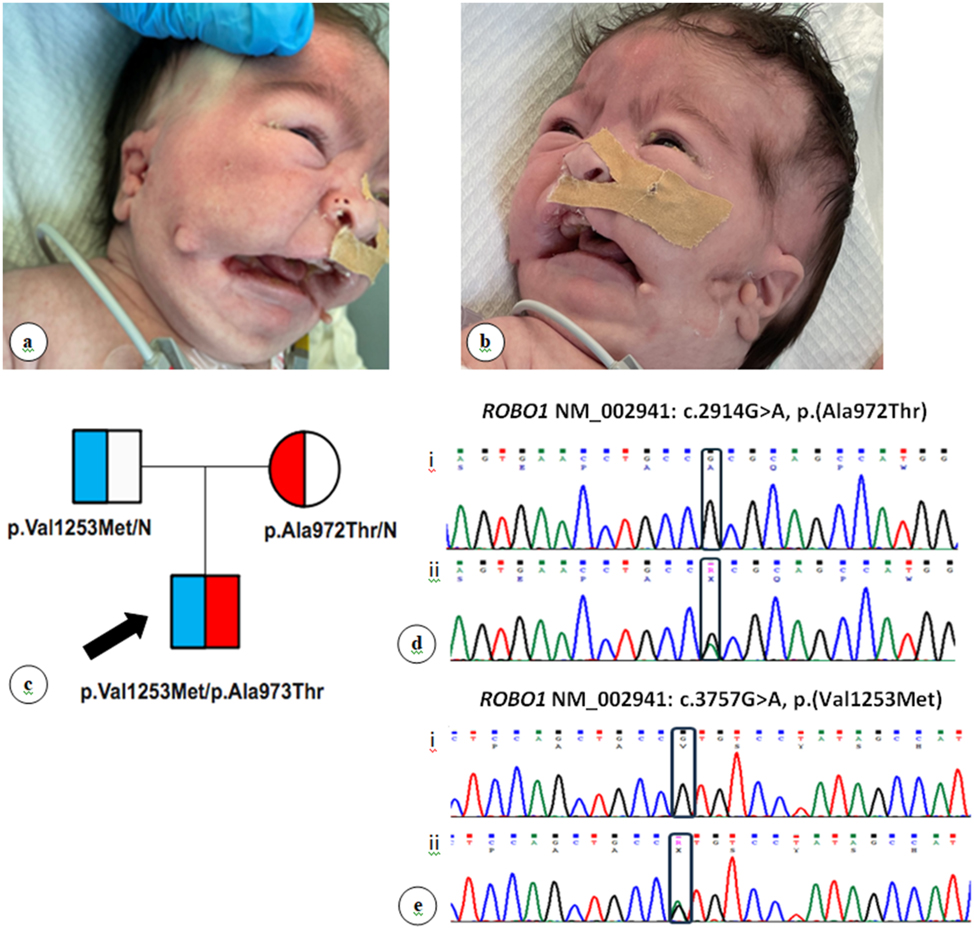

On physical examination, the baby exhibited a cleft palate, bilateral cleft lip, micrognathia, highly arched eyebrows, a sunken nasal bridge, and low-set ears with bilateral preauricular appendages. Multiple accessory auricles were noted, arranged in a curved triangular pattern extending from the oral commissure groove to the anterior auricle between the helical spine and the earlobe (Figure 1A and B). Additional findings included bilateral syndactyly of fourth and fifth toes, micropenis (penile length 0.7 cm) with bilaterally palpable small testes (testicular volume <1 mL as assessed by orchidometer), and subcoronal hypospadias. Shortly after admission, the neonate presented an episode of cyanosis with sudden oxygen desaturation and apnea, secondary to hypoglycemia (plasma glucose 5 mg/dL). Hormonal evaluation revealed multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies, including central hypothyroidism, secondary adrenal insufficiency (ACTH deficiency), hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, and growth hormone deficiency (Table 1). MRI showed a hypoplastic anterior pituitary, while the posterior pituitary and pituitary stalk appeared normal (Figure 2a and b). Abdominal ultrasound revealed a midline liver, while echocardiography and renal ultrasound showed no pathological findings. Ophthalmological examination was also normal. Replacement therapy with hydrocortisone and levothyroxine was initiated, and testosterone was administered during the mini-puberty period. Cleft lip and palate was surgically repaired; however, due to feeding difficulties and poor sucking, placement of a gastrostomy (G-tube) was required.

Clinical and genetic features of the patient. (A, B) Distinct craniofacial dysmorphism characterized by highly arched eyebrows, sunken nasal bridge, low-set ears with bilateral preauricular appendages, and multiple accessory auricles distributed within a curved triangle extending from the oral commissure groove to the anterior auricle between the helical spine and the ear lobe. Informed consent for publication of these images was obtained from the patient’s parents. (C) Family pedigree chart depicting ROBO1 gene variants segregation. Square, male; circle, female; half-filled square or circle: Heterozygote. The black arrow indicates the index case. (D) Part of ROBO1 exon 22 Sanger sequencing chromatogram. i. Normal; ii. Heterozygote. Black box depicts the position of the variants in the sequences. (E) Part of ROBO1 exon 26 Sanger sequencing chromatogram. i. Normal; ii. Heterozygote. Black box depicts the position of the variants in the sequences.

Laboratory hormone tests of the newborn patient with congenital hypopituitarism (CH).

| Hormones | Patient | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| GH | <0.05 | 5–40 ng/mL |

| IGF-1 | <0.25 | 15–129 ng/mL |

| Cortisol | 0.062 | 6.24–18 μg/dL |

| ACTH | <5 | 7–63 pg/mL |

| TSH | 6.67 | 0.5–5 μIU/mL |

| FT4 | 0.63 | 0.8–1.8 ng/dL |

| LH | <0.10 | <1.4 mIU/mL |

| FSH | <0.10 | <2.4 mIU/mL |

| Total testosterone | <0.20 | 0.75–4 ng/mL |

| 17-OH progesterone | 1.08 | 1.4–16.8 ng/mL |

| Prolactin | 0.93 | 5–20 ng/mL |

-

GH, growth hormone; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; FT4, free thyroxine; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; 17-OH progesterone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in the patient (a) Sagittal T1-weighted MRI showing a hypoplastic anterior pituitary (A), with normal pituitary stalk (B) and normal posterior pituitary bright spot (C). (b) Coronal T1-weighted MRI demonstrating a normal pituitary stalk (B) and normal posterior pituitary bright spot (C). (c) Axial T2-weighted MRI at neonatal age showing normal lateral ventricles (D). (d) Axial T2-weighted MRI at nine months of age showing enlargement of both lateral ventricles (D).

During regular follow-up, the infant exhibited severe delay in developmental milestones. Furthermore, both transient evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAE) and auditory brainstem responses (ABR) were repeatedly abnormal. At nine months of age, a repeat MRI revealed enlargement of the lateral and third ventricles, while the fourth ventricle remained of normal dimensions (Figure 2c and d). At one year of age, recombinant growth hormone (GH) replacement therapy was initiated due to persistent growth failure and confirmed GH deficiency. Τhe initial episodes of hypoglycemia resolved after initiating hydrocortisone replacement and did not recur during follow-up. Recombinant GH replacement therapy has been continued to date, with the patient now aged 32 months.

Genetic testing was performed after written informed consent was obtained from both parents. DNA was extracted from whole blood using standard methods, followed by sxome Sequencing (ES) using the Human Core Exome kit from Twist Bioscience. Paired-end sequencing of the resulting library was carried out on an Illumina NextSeq 500. Computational analysis included read alignment to the human genome reference sequence (GRCh37/hg19), base quality score recalibration, indel realignment, and variant calling, using the SOPHiA DDM® platform (Sophia Genetics, SA). Variants were annotated with the ANNOVAR algorithm and filtrated using VarAFT v2.16 (http://varaft.eu) application. An extended CPHD gene panel was searched for pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants. Variant classification was based on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria [15]. DNA from the patient and his parents underwent PCR amplification and bidirectionally sequencing using the Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on an ABI 3500 genetic analyzer (ABI 3500; Applied Biosystems) to verify the presence of the three genes variants found to be related to patient’s phenotype, as well as their mode of inheritance.

ES revealed that our patient is a compound heterozygote for two ROBO1 gene variants, the previously reported maternal variant NM_002941: c.2914G>A, p.(Ala972Thr) in exon 22 and the novel paternal variant NM_002941: c.3757G>A, p.(Val1253Met) in exon 26 (Table 2 and Figure 1C–E). Furthermore, ES identified two additional gene variants in NOTCH3 NM_000435: c.1505C>T, p.(Ser502Phe) and in GPR161 NM_001375883.1: c.1117C>T, p.(His373Tyr), both paternally inherited (Table 2). The Copy Number Variants (CNVs) reported in the analysis provided by SOPHiA DDM® platform did not include any finding relevant to our patient’s phenotype.

Pathogenic variants detected by exome sequencing (ES) in the newborn patient with congenital hypopituitarism (CH).

| Gene | Transcript | Nucleotide variant | Aminoacid variant | dbSNP | Inheritance | gnomAD exomes | gnomAD genomes | ClinVar Accession/Classification |

ACMG Classification/Criteria |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROBO1 | NM_002941 | c.2914G>A | p.Ala972Thr | rs371174175 | M | 0.0000252 | 0.0000957 | 001290238.1 VUS |

VUS PM2, BP4 |

Calloni SF, et al. [20] |

| ROBO1 | NM_002941 | c.3757G>A | p.Val1253Met | rs768909585 | P | 0.0000406 | 0.0000319 | NR | VUS PM2 |

NR |

| NOTCH3 | NM_000435 | c.1505C>T | p.Ser502Phe | rs778571943 | P | 0.000077 | 0.0000637 | 001288521.7 VUS |

VUS PM2, PM1, PP2 |

NR |

| GPR161 | NM_001375883.1 | c.1117C>T | p.His373Tyr | rs760550716 | P | 0.0000322 | Not found | 003855208.1 VUS |

VUS PM2 |

NR |

-

dbSNP, database single nucleotide polymorphism; gnomAD, genome aggregation database; ACMG, american college of medical genetics; M, maternal; P, paternal; VUS, variant of unknown significance; NR, not reported.

Methods (literature search)

All previously published ROBO1 gene variants associated with CH were retrieved from PubMed. The genetic, clinical, and MRI findings of these patients categorized as CH patients with PSIS and CH patients without PSIS were then summarized.

Discussion

In this study, the application of ES in a newborn with CPHD revealed compound heterozygosity for two ROBO1 variants, NM_002941: c.2914G>A, p.(Ala972Thr) previously reported, and the novel NM_002941: c.3757G>A, p.(Val1253Met) of maternal and paternal origin, respectively. Two additional novel heterozygous variants were also identified in NOTCH3 and GPR161 genes, both paternally inherited. The above genetic profile is associated with congenital hypopituitarism, midline brain abnormalities and dysmorphic craniofacial features.

The transmembrane receptor Roundabout 1 (ROBO1), a member of the immunoglobulin gene (Ig) superfamily, is located on human chromosome 3p12.3 [16]. The ROBO1 receptor is activated through interactions with extracellular matrix SLIT-family proteins [17]. The ROBO/SLIT signaling pathway plays a crucial role in axonal guidance, branching, and targeting; commissural axon pathfinding; cell differentiation; migration and formation of neuronal precursor cells, as well [18], 19]. Moreover, several studies underline the role of ROBO1 receptor as a gatekeeper for axonal midline crossing [10], 18].

Interestingly, in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), ROBO1 gene (Phenotype MIM Number 602430) was recently associated with pituitary hormone deficiency (combined or isolated) phenotypes. The association of ROBO1 gene variants and pituitary phenotypes, ranging from IGHD to CPHD, and PSIS, is supported by several reports [7], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Notably, ROBO1 was recently identified as the most frequent affected gene in a large cohort of CH patients from Argentina [7]. The majority of the reported ROBO1 variants are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. However, in the case presented herein, the compound heterozygosity points towards an autosomal recessive inheritance, in accordance with a previously reported homozygote patient with PSIS [10] and a compound heterozygote patient presenting with global developmental delay, severe intellectual disability, hyperactivity, spastic diplegia and ataxia [20].

ROBO1 gene variants associated with PSIS or CH are characterized by extremely variable phenotypes among family members exhibiting incomplete penetrance. The variable expressivity is exemplified in a recent study, where monozygotic twins carrying identical ROBO1 variants displayed phenotypic differences indicating the possible involvement of modifier alleles [7]. Regarding the type of variants, patients with PSIS predominantly carry nonsense or frameshift variants, while those with CH, including the patient described herein, more commonly harbor missense variants. The vast majority of these missense variants are currently classified as VUS, when applying the ACMG criteria, likely due to limited evidence linking these genetic changes to the disease pathogenesis [11].

Both ROBO1 variants identified in our patient are located on the CCO and CC1 segments of the ROBO1 intracellular domain (Figure 3) which, as has already being stated, plays a crucial role in regulating axon guidance and cell migration, and is involved in various cellular processes including proliferation, adhesion and potentially RNA processing [21]. It undergoes proteolytic cleavage and translocates to the nucleus, where it can influence gene expression [21]. Specifically, the novel ROBO1 variant identified in our patient is located in the distal part of the ROBO1 intracellular domain (cytoplasmic tail), which may still alter intracellular protein interactions, signaling dynamics and/or receptor stability [21]. The substitution of a conserved valine residue with methionine within the intracellular domain of the ROBO1 protein may play a key role in downstream signaling. However, further functional studies are required in order to specify the effect of the novel ROBO1 variant identified herein and to define its role in the pathogenesis of CH.

![Figure 3:

Schematic representation of ROBO1 variants related to congenital hypopituitarism (CH). Domain structure of the ROBO1 protein with annotated variants. The extracellular region includes five immunoglobulin-like (Ig) domains and three fibronectin type III (FNIII) domains. The intracellular region contains four conserved cytoplasmic motifs (CC0–CC3). The novel variant identified in this study, NM_002941: c.3757G>A, p.(Val1253Met) is highlighted in green font. Figure adapted from Xu F, et al. (2015), Nature Communications [45], with modifications. Figure was created in BioRender. (https://BioRender.com/wokoi3x).](/document/doi/10.1515/jpem-2025-0086/asset/graphic/j_jpem-2025-0086_fig_003.jpg)

Schematic representation of ROBO1 variants related to congenital hypopituitarism (CH). Domain structure of the ROBO1 protein with annotated variants. The extracellular region includes five immunoglobulin-like (Ig) domains and three fibronectin type III (FNIII) domains. The intracellular region contains four conserved cytoplasmic motifs (CC0–CC3). The novel variant identified in this study, NM_002941: c.3757G>A, p.(Val1253Met) is highlighted in green font. Figure adapted from Xu F, et al. (2015), Nature Communications [45], with modifications. Figure was created in BioRender. (https://BioRender.com/wokoi3x).

Based on MRI findings, most ROBO1 variants reported in the literature have been associated with PSIS; to date, 13 cases of ROBO1 variants linked to PSIS have been described [7], 10], [12], [13], [14] (Table 3). PSIS is characterized by a thin or absent pituitary stalk and is often accompanied by hypoplasia or aplasia of the anterior pituitary and an ectopic or absent posterior pituitary [8], 9]. Additional MRI findings reported in patients with ROBO1 variants include isolated anterior pituitary hypoplasia, pituitary stalk duplication, thinning or dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, hypoplasia of the pons and midbrain, absent septum pellucidum, rounded medial convexities (Probst bundles), and hydrocephalus [10], [11], [12], [13, 22]. The maternally inherited p.(Ala972Thr) variant identified in our patient was previously reported as NM_133631.3: c.2779G>A, p.(Ala927Thr) in compound heterozygosity with variant NM_133631.3: c.2096 G>A, p.(Ser699Asn) in a patient with global developmental delay, severe intellectual disability, hyperactivity, spastic diplegia, and ataxia [20]; it is noteworthy that the above patient exhibited no symptoms or signs of CH. Brain imaging in the reported case revealed pontine hypoplasia, thinning of the anterior commissure and corpus callosum, and absence of the transverse pontine fibers [20].

Clinical and genetic features of patients with pituitary stalk interruption syndrome (PSIS), congenital hypopituitarism (CH) and ROBO1 gene variants.

| Bashamboo et al. [13] | Bashamboo et al. [13] | Bashamboo et al. [13] | Bashamboo et al. [13] | Bashamboo et al. [13] | Dateki et al. [10] | Liu et al. [14] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 2.6 years | 2.6 years | 1 year | 3.9 years | 27.7 years | 18 months | 4 years | ||||||

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male | ||||||

| Ethnicity | French | French | French | French | French | Japanese | Chinese | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| ROBO1 variants | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Allele 1 | c.2928_2929delG p.Ala977GInfs*40 | c.2928_2929delG p.Ala977GInfs*40 | c.3450G>T p.Tyr1114Ter* | c.719G>C p.Cys240Ser | c.719G>C p.Cys240Ser | c.1342+1G>A | c.1690C>T p.Pro564Ser | ||||||

| Allele 2 | – | – | – | – | – | c.1342+1G>A | – | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Birth history | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Gestational age, weeks | 39 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 39 | 38 | 39 | ||||||

| Birth weight, gr | 2,800 | 2,950 | 3,580 | 3,270 | N/A | 3,280 | 2,860 | ||||||

| Birth length, cm | 48 | 49 | 48.5 | 49 | N/A | 50 | 50 | ||||||

| Birth head circumference, cm | 34 | 34 | 36 | N/A | N/A | 37.5 | N/A | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Family history | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Twins | Twins | None | Paternal aunt with CPHD-Paternal grandfather with short stature | Paternal niece is the previous patient of Table 3 | Consanguineous parents | Mother with short stature – maternal grandmother with short stature, strabismus | |||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Clinical findings | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Affected anterior pituitary hormones | GH | GH | GH | GH, TSH | GH, TSH, ACTH, FSH, LH | GH, TSH, ACTH, FSH, LH, PRL | GH, TSH, ACTH | ||||||

| Posterior pituitary dysfunction | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Short stature | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Micropenis | – | N/A | – | N/A | N/A | + | – | ||||||

| Cryptorchidism | – | N/A | – | N/A | N/A | + | – | ||||||

| Hypotonia | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | ||||||

| Developmental delay | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | ||||||

| Intellectual disability | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | ||||||

| Ophthalmologic defects | Hypermetropia, strabismus | Hypermetropia, strabismus, white perimacular granulations | Ptosis | Strabismus | – | Strabismus | Strabismus | ||||||

| Hearing loss | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | ||||||

| Dysmorphic facial features | – | – | – | – | – | Broad forehead, micrognathia, broad philtrum, arched eyebrows | – | ||||||

| Cardiovascular anomalies | – | – | – | Cardiomyopathy | – | – | – | ||||||

| Renal defects | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Other findings | – | – | – | – | – | Hyperbilirubinemia | Hyponatremia | ||||||

| Martinez-Mayer et al. [7] | Martinez-Mayer et al. [7] | Martinez-Mayer et al. [7] | Martinez-Mayer et al. [7] | Martinez-Mayer et al. [7] | Misgar et al. [12] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.7 years | |||||||

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male | |||||||

| Ethnicity | Argentinian | Argentinian | Argentinian | Argentinian | Argentinian | Kashmiri | |||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| ROBO1 variants | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Allele 1 | c.1463G>A p.Trp488* | c.4510C>T p.Arg1504* | c.730A>G p.Asn244Asp | c.4821G>A p.Met1607Ile | c.2647C>T p.Gln883* | c.4852del p.Glu1618AsnfsTer5 | |||||||

| Allele 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Birth history | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Gestational age, weeks | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Full-term | |||||||

| Birth weight, gr | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3,000 | |||||||

| Birth length, cm | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||

| Birth head circumference, cm | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Family history | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| None | None | None | None | Twins | None | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Clinical findings | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Affected anterior pituitary hormones | GH | GH, TSH, ACTH, FSH, LH | GH | GH, TSH, ACTH, FSH, LH | GH, TSH, ACTH, FSH, LH | GH, TSH, ACTH | |||||||

| Posterior pituitary dysfunction | – | – | – | – | – | + (diabetes insipidus) | |||||||

| Short stature | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| Micropenis | – | – | – | – | N/A | – | |||||||

| Cryptorchidism | – | – | – | – | N/A | – | |||||||

| Hypotonia | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Developmental delay | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Intellectual disability | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Ophthalmologic defects | – | Optic nerve hypoplasia, blindness | – | – | – | Blue sclera | |||||||

| Hearing loss | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Dysmorphic facial features | – | – | – | – | – | Prominent forehead, mid-facial hypoplasia | |||||||

| Cardiovascular anomalies | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Renal defects | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Other findings | – | – | – | – | – | Hypoglycemia and hyperbilirubinemia during neonatal period | |||||||

-

GH, growth hormone; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; PRL, prolactin; CPHD, combined pituitary hormone deficiency; N/A, not applicable.

Beyond pituitary abnormalities, ROBO1 gene variants have also been associated with several ophthalmic disorders, including optic nerve hypoplasia, microphthalmia/anophthalmia, hypermetropia, strabismus, and ptosis [7], 10], [12], [13], [14, 23]. Previous studies have shown that ROBO1 influences retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axon divergence at the optic chiasm and determines the relative positioning of the optic chiasm at the ventral midline of the developing hypothalamus [24]. The ROBO/SLIT signaling pathway is also implicating in ocular neovascularization, with ROBO1 expression reported to have both pro- and anti-angiogenic effects in ocular neovascular diseases [24]. In addition, ear abnormalities and hearing impairment, such as sensorineural hearing loss, have been linked to ROBO1 variants [10], 25]. ROBO1 and ROBO2 gene expression play a crucial role in the development and morphology of the pinna, with loss-of-function variants reported to cause microtia, crumpled helices, and uplifted lobes [25].

Characteristic facial features have been reported in patients with ROBO1 variants, including a broad forehead and philtrum, triangular face, dolichocephaly, micrognathia, cleft lip, high arched palate, downslanting palpebral fissures, hypoplastic supraorbital ridges, and arched eyebrows [10], [11], [12, 22]. The ROBO/SLIT signaling pathway plays a critical role in the regulation of craniofacial neural crest cell (NCC) migration and differentiation. ROBO1 and ROBO2 are expressed in cranial NCCs that migrate to the pharyngeal arches and contribute to craniofacial morphogenesis and cranial bone development [26]. Furthermore, ROBO1 has been implicated in the genetic pathogenesis of craniofacial microsomia (CFM), a congenital anomaly affecting derivatives of the 1st and 2nd pharyngeal arches, from which most craniofacial structures originate [27]. In mouse models, ROBO1 is significantly expressed in the pharyngeal arches and their derivatives of CFM-related craniofacial structures, such as jaw, ear, and eye [27].

Furthermore, ROBO1 variants have been reported in individuals with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract, including unilateral or bilateral kidney agenesis, vesicoureteral junction obstruction, vesicoureteral reflux, and posterior urethral valve, as well as in cases with proteinuria, genital malformations, hypospadias and increased renal echogenicity [11]. These findings underscore the critical role of the ROBO/SLIT signaling pathway in kidney development [28], 29]. Moreover, ROBO1 variants have been identified in individuals with cardiovascular disorders, such as cardiomyopathy, tetralogy of Fallot, and ventricular or atrial septal defects [13], 22], 30]. The SLIT/ROBO signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in the heart tube development in Drosophila [31]. Loss of ROBO1 function has also been associated with septal defects and conotruncal amomalies in mouse models, as well as cardiac tube defects in zebrafish [32], 33]. Other congenital anomalies reported in cases of ROBO1 loss of function variants include diaphragmatic hernia, vocal cord paresis and rhizomelia [30], 34].

ROBO1 gene variants have been also associated with hypotonia, psychomotor developmental delay, and severe intellectual disability [10], 20], 22]. Moreover, a monoallelic ROBO1 variant has been reported in a patient with early-onset epileptic encephalopathy [35]. Beyond its role in axon guidance, the ROBO/SLIT signaling pathway plays a critical role in cortical progenitor cell proliferation, dendritic formation and neocortical development. It has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as dyslexia and autism spectrum disorder [36].

The genetic and clinical characteristics of PSIS patients, as well as the genetic, clinical, and MRI findings of patients with CH only, reported to harbor ROBO1 variants, are summarized in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. A visual representation of previously reported ROBO1 variants associated with CH, alongside with the novel variant identified in our study have been also demonstrated onto the ROBO1 protein domain structure (Figure 3).

Clinical and genetic features, as well as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of patients with congenital hypopituitarism (CH) without pituitary stalk interruption syndrome (PSIS) and ROBO1 gene variants.

| Scala et al. [22] | Woodring et al. [11] | Martinez-Mayer et al. [7] | Martinez-Mayer et al. [7] | Martinez-Mayer et al. [7] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 4.5 years | 9 days | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Male | Male |

| Ethnicity | Italian | White | Argentinian | Argentinian | Argentinian |

|

|

|||||

| ROBO1 variants | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Allele 1 | 343.7 kb deletion of 3p12.3 encompassing ROBO1 | c.107G>T p.Arg36Met |

c.2647C>T p.Gln883* |

c.1529dupT p.Gln511fs |

c.234T>G p.Ile78Met |

| Allele 2 | – | c.4610G>A p.Gly1537Glu |

– | – | – |

|

|

|||||

| Birth history | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Gestational age, weeks | Full-term | 29+4 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Birth weight, gr | 2,900 | 740 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Birth length, cm | 44 | 30 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Birth head circumference, cm | 35 | 23 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

|

|||||

| Family history | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Father with frontal bossing, sparse eyebrows, bulbous nasal tip, deep philtrum and pointed chin. Hypoplasia of the anterior pituitary and ectopic posterior lobe | None | Twins | None | None | |

|

|

|||||

| Clinical findings | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Affected anterior pituitary hormones | GH, PRL | GH, ACTH | GH | GH | GH |

| Posterior pituitary dysfunction | – | – | – | – | – |

| Short stature | + | + | + | + | + |

| Micropenis | N/A | – | N/A | – | – |

| Cryptorchidism | N/A | – | N/A | – | – |

| Hypotonia | – | – | – | – | – |

| Developmental delay | + | – | – | – | – |

| Intellectual disability | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ophthalmologic defects | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hearing loss | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dysmorphic facial features | Prominent forehead, down-slanting palpebral fissures, depressed nasal bridge, low-set ears with bilateral agenesis of helical crus, pointed chin | Triangular face, long philtrum | – | – | – |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | Atrial septal defect | – | – | – | – |

| Renal defects | – | Multiple bilateral cortical cysts, proteinuria, grade 3 vesicoureteral reflex | – | – | – |

| Other findings | Hypoglycemia | Hypospadias, retractile testes | – | – | – |

|

|

|||||

| MRI findings | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Anterior pituitary hypoplasia | + | – | – | – | – |

| Ectopic or absent posterior pituitary | – | – | + | – | – |

| Absent or thin pituitary stalk | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dysgenesis/Hypoplasia of corpus callosum | – | + | – | – | – |

| Hypolastic pontine | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hypoplastic midbrain | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hydrocephalus | – | + | Intrasellar arachnoidocele | – | – |

| Other findings | Peculiar duplication of pituitary stalk | Absent septum pellucidum, probst bundles | |||

-

GH, growth hormone; PRL, prolactin; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; N/A, not applicable; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

In this study, ES revealed that our patient, in addition to the major finding of ROBO1 compound heterozygosity, was heterozygous for two novel variants; the NM_000435: c.1505C>T, p.(Ser502Phe) variant in NOTCH3 gene, and the NM_001375883.1: c.1117C>T, p.(His373Tyr) variant in GPR161 gene, both paternally inherited. The classification of these novel variants as VUS, according to ACMG criteria, is based mainly on their rarity in gnomAD database (Table 2). NOTCH3 is classified as VUS based on the criteria of rarity, PM2 extremely low frequency in gnomAD, as well as PM1 and PP2, and it is reported by ClinVar as VUS by two entries. Similarly, the GPR161 variant is classified as VUS based solely on the criterion of frequency PM2 (f=0.00 in the European Non-Finnish population). However, it has been very recently (April 2025) been reported by ClinVar, also, as a variant of uncertain significance [37]. Both NOTCH3 and GPR161 variants are classified as of uncertain pathogenicity according to the aggregated in silico prediction tool REVEL.

However, VUS results should not be disregarded, as their uncertainty does not imply a lack of significance [11], 38]. Patient’s father does not exhibit any pituitary characteristics, which may be interpreted as evidence against the pathogenicity of the above variants. However, the established involvement of NOTCH3 and GPR161 genes in critical pituitary developmental processes and midline formation raise the possibility that they may contribute to the observed phenotype in a multigenic or oligogenic manner. Further functional and segregation studies are necessary to clarify the potential pathogenic relevance of the above NOTCH3 and GPR161 variants with the genetic basis of CH.

Specifically, the NOTCH signaling pathway plays a critical role in pituitary gland development by mediating the proliferation and differentiation of pituitary cell lineages and supporting the maintenance and expansion of pituitary progenitor cells [39]. A significant cross-talk interaction between the ROBO/SLIT and NOTCH signaling pathways has been reported. ROBO1 enhances Hes1, a key component of the NOTCH pathway, which plays a pivotal role in guiding hypothalamic axons towards the pituitary gland and promoting pituitary cell differentiation [36], 40]. Transcriptional activation of Hes1 also regulates the production of intermediate progenitor cells from apical radial glial cells of the neocortex [36] and may contribute to dysregulation of ROBO1 signaling in patients with PSIS [13]. Furthermore, ROBO1 and ROBO2 receptors upregulate the NOTCH ligands, Jag1 and Jag2, while down-regulating Dll1 expression. This cross-talk modulates neurogenesis in the neocortex and may also influence midline crossing and structural formation [36], 41].

Regarding the GPR161 gene, it encodes the orphan G protein-coupled receptor 161, a key negative regulator of the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway [42], 43]. Although a direct interaction between ROBO/SLIT signaling and GPR161 has not been described, previous studies have reported that the ROBO/SLIT pathway can be activated by SHH [44], which in turn is negatively regulated by GPR161. Further research is needed to explore potential interactions between ROBO1 and GPR161 receptors and their signaling pathways, in the context of multigenic or oligogenic pathogenesis of CH.

We strongly emphasize that the compound heterozygous ROBO1 variants identified in our patient represent the primary and most likely pathogenic finding, given their established association with congenital hypopituitarism and midline defects. However, in light of the midline brain anomalies, distinct dysmorphic craniofacial features, and the complex phenotype of hypopituitarism observed in our patient, the additional variants in NOTCH3 and GPR161 -particularly the NOTCH3 variant- may exert a modifying or synergistic effect on the phenotype. Notably, our patient exhibits craniofacial dysmorphisms, not previously reported in ROBO1-related cases, suggesting potential genetic contributions beyond ROBO1. Furthermore, specific midline anomalies, such as the enlargement of both the lateral and third ventricles on brain MRI and the presence of a midline liver, are described here for the first time in association with ROBO1 variants. These findings support the emerging concept of an oligogenic etiology in CH, where co-occurrence of NOTCH3 and GPR161 variants may interact to shape the final phenotype. Further functional studies are required to determine whether these NOTCH3 and GPR161 variants contribute synergistically to the pathogenesis of CH.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the genetic etiology of CH remains unknown in most patients, suggesting that additional genes involved in pituitary development are yet to be discovered. In this study, we identified compound heterozygosity in the ROBO1 gene in a newborn with CPHD and multiple dysmorphic features. Our case together with previously reported patients, support ROBO1 as a potential causative gene in CH. The role of ROBO1 in our patient’s phenotype is further reinforced by coexisting anomalies, including craniofacial abnormalities, hearing impairment, hypospadias, severe neurodevelopmental delay, and, notably, enlargement of the lateral and third ventricles on brain MRI, and a midline liver, findings not previously described in association with ROBO1 variants. To our knowledge, the unique combination of clinical features alongside a novel ROBO1 variant has not been reported in CH. Moreover, the possible cross-talk between ROBO/SLIT and NOTCH signaling pathways highlights an oligogenic or multigenic basis for CH. Given the variable penetrance and expressivity of ROBO1-related pituitary and extrapituitary phenotypes, ROBO1 should be considered in genetic investigations of patients with CH and midline abnormalities.

Learning points

ROBO1 is a potentially causative gene of congenital hypopituitarism (CH) and should be included in genetic investigations of patients with CH, especially those with midline abnormalities and/or craniofacial dysmorphic features.

ROBO1 gene variants are associated with a broad spectrum of pituitary-phenotypes, ranging from isolated growth hormone deficiency (IGHD) to combined pituitary hormone deficiency (CPHD), and pituitary stalk interruption syndrome (PSIS), as well as with diverse extrapituitary manifestations.

ROBO1-related CH can exhibit phenotypic heterogeneity within families and incomplete penetrance.

Next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies are crucial for elucidating the genetic basis of CH and identifying causative variants.

What is new?

This study describes a novel compound heterozygosity of ROBO1 gene variants, alongside with two previously unreported variants in NOTCH3 and GPR161, identified by exome sequencing (ES), in a newborn with CPHD, dysmorphic features and midline abnormalities.

The patient presented a distinctive phenotype comprising CH, craniofacial dysmorphism, hearing impairment, hypospadias, severe neurodevelopmental delay, ventriculomegaly (enlargement of the lateral and third ventricles on brain MRI), and a midline liver.

The interplay between ROBO/SLIT and NOTCH signaling pathways supports a potential oligogenic or multigenic contribution to CH pathogenesis in this case.

Funding source: Hellenic Academic Libraries Link

Acknowledgments

The publication of the article in OA mode is financially supported by HEAL-Link.

-

Research ethics: This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research and Ethics committee of “Aghia Sofia” Children’s Hospital, Athens, Greece corresponding to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from patient’s parents for genetic testing, as well as for participating in our study. Written informed consent was obtained from patient’s parents for publication of this case report and for accompanying images.

-

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from patient’s parents for genetic testing, as well as for participating in our study. Written informed consent was obtained from patient’s parents for publication of this case report and for accompanying images.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, visualization, and writing of the original draft: PM, AS, TS and CKG; data curation: PM, AS; methodology, software, validation, formal analysis and project administration: AS; investigation: PM, MB, IF, EN, TS and CKG; funding acquisition: AS, TS, CKG; resources, supervision and writing – review and editing: TS and CKG. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The publication of the article in OA mode is financially supported by HEAL-Link.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Davis, SW, Ellsworth, BS, Peréz Millan, MI, Gergics, P, Schade, V, Foyouzi, N, et al.. Pituitary gland development and disease: from stem cell to hormone production. Curr Top Dev Biol 2013;106:1–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-416021-7.00001-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Bosch, I, Ara, L, Katugampola, H, Dattani, MT. Congenital hypopituitarism during the neonatal period: epidemiology, pathogenesis, therapeutic options, and outcome. Front Pediatr 2020;8:600962. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.600962.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Cherella, CE, Cohen, LE. Congenital hypopituitarism in neonates. NeoReviews 2018;19:e742–52. https://doi.org/10.1542/neo.19-12-e742.Search in Google Scholar

4. Gregory, LC, Cionna, C, Cerbone, M, Dattani, MT. Identification of genetic variants and phenotypic characterization of a large cohort of patients with congenital hypopituitarism and related disorders. Genet Med Off J Am Coll Med Genet 2023;25:100881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2023.100881.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Sertedaki, A, Tatsi, EB, Vasilakis, IA, Fylaktou, I, Nikaina, E, Iacovidou, N, et al.. Whole exome sequencing points towards a multi-gene synergistic action in the pathogenesis of congenital combined pituitary hormone deficiency. Cells 2022;11:2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132088.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Munoz, A, Urban, R. Neuroendocrine consequences of traumatic brain injury. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2013;20:354–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/med.0b013e32836318ba.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Martinez-Mayer, J, Vishnopolska, S, Perticarari, C, Iglesias Garcia, L, Hackbartt, M, Martinez, M, et al.. Exome sequencing has a high diagnostic rate in sporadic congenital hypopituitarism and reveals novel candidate genes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2024;109:3196–210. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgae320.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Pinto, G, Netchine, I, Sobrier, ML, Brunelle, F, Souberbielle, JC, Brauner, R. Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome: a clinical-biological-genetic assessment of its pathogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:3450–4. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.82.10.4295.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Voutetakis, A. Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome. Handb Clin Neurol 2021;181:9–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820683-6.00002-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Dateki, S, Watanabe, S, Mishima, H, Shirakawa, T, Morikawa, M, Kinoshita, E, et al.. A homozygous splice site ROBO1 mutation in a patient with a novel syndrome with combined pituitary hormone deficiency. J Hum Genet 2019;64:341–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s10038-019-0566-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Woodring, TS, Mirza, MH, Benavides, V, Ellsworth, KA, Wright, MS, Javed, MJ, et al.. Uncertain, not unimportant: callosal dysgenesis and variants of uncertain significance in ROBO1. Pediatrics 2021;148:e2020019000. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-019000.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Misgar, RA, Chhabra, A, Qadir, A, Arora, S, Wani, AI, Bashir, MI, et al.. Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome due to novel ROBO1 mutation presenting as combined pituitary hormone deficiency and central diabetes insipidus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2024;37:477–81. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2023-0541.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Bashamboo, A, Bignon-Topalovic, J, Moussi, N, McElreavey, K, Brauner, R. Mutations in the human ROBO1 gene in pituitary stalk interruption syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:2401–6. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-1095.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Liu, Z, Chen, X. A novel missense mutation in human receptor roundabout-1 (ROBO1) gene associated with pituitary stalk interruption syndrome. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2020;12:212–7. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2019.2018.0309.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Richards, S, Aziz, N, Bale, S, Bick, D, Das, S, Gastier-Foster, J, et al.. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med Off J Am Coll Med Genet 2015;17:405–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.30.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Tong, M, Jun, T, Nie, Y, Hao, J, Fan, D. The role of the slit/robo signaling pathway. J Cancer 2019;10:2694–705. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.31877.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Brose, K, Bland, KS, Wang, KH, Arnott, D, Henzel, W, Goodman, CS, et al.. Slit proteins bind robo receptors and have an evolutionarily conserved role in repulsive axon guidance. Cell 1999;96:795–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674-00-80590-5.Search in Google Scholar

18. Andrews, W, Liapi, A, Plachez, C, Camurri, L, Zhang, J, Mori, S, et al.. Robo1 regulates the development of major axon tracts and interneuron migration in the forebrain. Dev Camb Engl 2006;133:2243–52. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.02379.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Blockus, H, Chédotal, A. The multifaceted roles of slits and Robos in cortical circuits: from proliferation to axon guidance and neurological diseases. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2014;27:82–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2014.03.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Calloni, SF, Cohen, JS, Meoded, A, Juusola, J, Triulzi, FM, Huisman, TAGM, et al.. Compound heterozygous variants in ROBO1 cause a neurodevelopmental disorder with absence of transverse pontine fibers and thinning of the anterior commissure and corpus callosum. Pediatr Neurol 2017;70:70–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.01.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Miller, P. Itinerancy between attractor states in neural systems. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2016;40:14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2016.05.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Scala, M, Accogli, A, Allegri, AME, Tassano, E, Severino, M, Morana, G, et al.. Familial ROBO1 deletion associated with ectopic posterior pituitary, duplication of the pituitary stalk and anterior pituitary hypoplasia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2019;32:95–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2018-0272.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Dattani, MT. Congenital hypopituitarism - novel phenotypes, novel mechanisms. Rev Esp Endocrinol Pediatr 2020;11:26–38.Search in Google Scholar

24. Erskine, L, Williams, SE, Brose, K, Kidd, T, Rachel, RA, Goodman, CS, et al.. Retinal ganglion cell axon guidance in the mouse optic chiasm: expression and function of Robos and slits. J Neurosci 2000;20:4975. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.20-13-04975.2000.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Quiat, D, Kim, SW, Zhang, Q, Morton, SU, Pereira, AC, DePalma, SR, et al.. An ancient founder mutation located between ROBO1 and ROBO2 is responsible for increased microtia risk in amerindigenous populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A 2022;119:e2203928119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2203928119.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Li, Y, Zhang, XT, Wang, XY, Wang, G, Chuai, M, Münsterberg, A, et al.. Robo signaling regulates the production of cranial neural crest cells. Exp Cell Res 2017;361:73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.10.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Zhang, YB, Hu, J, Zhang, J, Zhou, X, Li, X, Gu, C, et al.. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for craniofacial microsomia. Nat Commun 2016;7:10605. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10605.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Münch, J, Engesser, M, Schönauer, R, Hamm, JA, Hartig, C, Hantmann, E, et al.. Biallelic pathogenic variants in roundabout guidance receptor 1 associate with syndromic congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Kidney Int 2022;101:1039–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2022.01.028.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Feng, L, Shu, HP, Sun, LL, Tu, YC, Liao, QQ, Yao, LJ. Role of the SLIT-ROBO signaling pathway in renal pathophysiology and various renal diseases. Front Physiol 2023;14:1226341. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2023.1226341.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Kruszka, P, Tanpaiboon, P, Neas, K, Crosby, K, Berger, SI, Martinez, AF, et al.. Loss of function in ROBO1 is associated with tetralogy of fallot and septal defects. J Med Genet 2017;54:825–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104611.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Medioni, C, Astier, M, Zmojdzian, M, Jagla, K, Sémériva, M. Genetic control of cell morphogenesis during Drosophila melanogaster cardiac tube formation. J Cell Biol 2008;182:249–61. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200801100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Mommersteeg, MTM, Yeh, ML, Parnavelas, JG, Andrews, WD. Disrupted slit-robo signalling results in membranous ventricular septum defects and bicuspid aortic valves. Cardiovasc Res 2015;106:55–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvv040.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Fish, JE, Wythe, JD, Xiao, T, Bruneau, BG, Stainier, DYR, Srivastava, D, et al.. A slit/miR-218/Robo regulatory loop is required during heart tube formation in zebrafish. Development 2011;138:1409–19. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.060046.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Petek, E, Windpassinger, C, Simma, B, Mueller, T, Wagner, K, Kroisel, PM. Molecular characterisation of a 15 Mb constitutional de novo interstitial deletion of chromosome 3p in a boy with developmental delay and congenital anomalies. J Hum Genet 2003;48:283–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10038-003-0023-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Huang, Y, Ma, M, Mao, X, Pehlivan, D, Kanca, O, Un-Candan, F, et al.. Novel dominant and recessive variants in human ROBO1 cause distinct neurodevelopmental defects through different mechanisms. Hum Mol Genet 2022;31:2751–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddac070.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Gonda, Y, Namba, T, Hanashima, C. Beyond axon guidance: roles of slit-robo signaling in neocortical formation. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020;8:607415. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.607415.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. National Center for Biotechnology Information. ClinVar; [VCV003855208.1]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/VCV003855208.1.Search in Google Scholar

38. Chen, E, Facio, FM, Aradhya, KW, Rojahn, S, Hatchell, KE, Aguilar, S, et al.. Rates and classification of variants of uncertain significance in hereditary disease genetic testing. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2339571. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.39571.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Ge, X, Weis, K, Raetzman, L. Glycoprotein hormone subunit alpha 2 (GPHA2): a pituitary stem cell-expressed gene associated with NOTCH2 signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2024;586:112163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2024.112163.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Bando, H, Urai, S, Kanie, K, Sasaki, Y, Yamamoto, M, Fukuoka, H, et al.. Novel genes and variants associated with congenital pituitary hormone deficiency in the era of next-generation sequencing. Front Endocrinol 2022;13:1008306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1008306.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Cárdenas, A, Villalba, A, de, JRC, Picó, E, Kyrousi, C, Tzika, AC, et al.. Evolution of cortical neurogenesis in amniotes controlled by robo signaling levels. Cell 2018;174:590–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Mukhopadhyay, S, Wen, X, Ratti, N, Loktev, A, Rangell, L, Scales, SJ, et al.. The ciliary G-protein-coupled receptor Gpr161 negatively regulates the sonic hedgehog pathway via cAMP signaling. Cell 2013;152:210–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.026.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Hoppe, N, Harrison, S, Hwang, SH, Chen, Z, Karelina, M, Deshpande, I, et al.. GPR161 structure uncovers the redundant role of sterol-regulated ciliary cAMP signaling in the hedgehog pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2024;31:667–77. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-024-01223-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Liu, J, Wang, X, Li, J, Wang, H, Wei, G, Yan, J. Reconstruction of the gene regulatory network involved in the sonic hedgehog pathway with a potential role in early development of the mouse brain. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10:e1003884. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003884.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Xu, F, Wu, LY, Chang, CK, He, Q, Zhang, Z, Liu, L, et al.. Whole-exome and targeted sequencing identify ROBO1 and ROBO2 mutations as progression-related drivers in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Commun 2015;6:8806. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9806.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Spatiotemporal associations between incidence of type 1 diabetes and COVID-19 vaccination rates in children in Germany – a population-based ecological study

- Continuous glucose monitoring evidence of celiac disease in type 1 diabetes

- Impact of race and delayed adoption of diabetes technology on glycemia and partial remission in type 1 diabetes

- Immunogenetic profiling of type 1 diabetes in Jordan: a case-control study on HLA-associated risk and protection

- Annual case counts and clinical characteristics of pediatric and adolescent patients with diabetes in Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. A 14 year retrospective study

- Real-world effectiveness of sodium glucose transporter 2 inhibitors among youth with type 2 diabetes

- Investigation of the association between nitric oxide synthase gene variants and NAFLD in adolescents with obesity

- Cardiometabolic outcomes in girls with premature adrenarche: a longitudinal analysis of typical vs. exaggerated presentations

- A disease that is difficult to predict: regional distribution and phenotypic, histopathological and genetic findings in McArdle disease

- Causal analysis of uterine artery pulsatility index-related proteins and the risk of precocious puberty in girls: a Mendelian randomization study

- Case Reports

- Understanding rickets in osteopetrosis via a case: mechanisms and treatment implications

- A case of JAGN1 mutation presenting with atypical diabetes and immunodeficiency

- Compound heterozygous ROBO1 gene variants in a neonate with congenital hypopituitarism, dysmorphic features and midline abnormalities: a case report and review of the literature

- Phenotypic variation among four members in a family with DAX1 deficiency

- MMP13-related metaphyseal dysplasia: a differential diagnosis of rickets

- Congress Abstracts

- JA-PED | Annual Meeting of the German Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Endocrinology and Diabetology (DGPAED e. V.)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Spatiotemporal associations between incidence of type 1 diabetes and COVID-19 vaccination rates in children in Germany – a population-based ecological study

- Continuous glucose monitoring evidence of celiac disease in type 1 diabetes

- Impact of race and delayed adoption of diabetes technology on glycemia and partial remission in type 1 diabetes

- Immunogenetic profiling of type 1 diabetes in Jordan: a case-control study on HLA-associated risk and protection

- Annual case counts and clinical characteristics of pediatric and adolescent patients with diabetes in Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. A 14 year retrospective study

- Real-world effectiveness of sodium glucose transporter 2 inhibitors among youth with type 2 diabetes

- Investigation of the association between nitric oxide synthase gene variants and NAFLD in adolescents with obesity

- Cardiometabolic outcomes in girls with premature adrenarche: a longitudinal analysis of typical vs. exaggerated presentations

- A disease that is difficult to predict: regional distribution and phenotypic, histopathological and genetic findings in McArdle disease

- Causal analysis of uterine artery pulsatility index-related proteins and the risk of precocious puberty in girls: a Mendelian randomization study

- Case Reports

- Understanding rickets in osteopetrosis via a case: mechanisms and treatment implications

- A case of JAGN1 mutation presenting with atypical diabetes and immunodeficiency

- Compound heterozygous ROBO1 gene variants in a neonate with congenital hypopituitarism, dysmorphic features and midline abnormalities: a case report and review of the literature

- Phenotypic variation among four members in a family with DAX1 deficiency

- MMP13-related metaphyseal dysplasia: a differential diagnosis of rickets

- Congress Abstracts

- JA-PED | Annual Meeting of the German Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Endocrinology and Diabetology (DGPAED e. V.)