Abstract

Our “Beacons of Organizational Sociology” series makes available, through essays or first-time translations, concepts and texts that have shaped debates in organizational sociology in non-English-speaking countries or presents reflections on such debates by established scholars. The second text in this series presents a model for holistic organizational analysis, named The Pentagon Model. The model is developed in Norway and has, during the last two decades, been successfully applied in many research projects, both basic and applied, and in different kinds of organizations. The model has also proved to be well-suited for educational purposes and for the dissemination of research-based findings. The model builds on established organization theories and rests on a basic argument that most organizational issues concerning qualities and capabilities can be fruitfully sorted into five interdependent categories: formal structure, technology, culture, interaction, and social relations and networks. This taxonomy can be used both as guidelines for data collection by qualitative or quantitative methods and for sorting findings into corresponding groups of variables. The model has proved to be widely applicable and can be used for studying phenomena on different organizational levels: individual, collective, system and ecological. It can also be used with different time perspectives: to explain things that happened in the past, to describe present-day situations, and to point to upcoming challenges and future possibilities.

1 Background

One of the distinctive features of Norwegian organizational sociology is a long tradition of openness and cooperation between academia and industry. This situation of mutual trust has made it possible to get deep insights into internal processes, strengths and problems, in both private and public organizations, and throughout the years, there have been few limitations for researchers in collecting data, both qualitative and quantitative. This has also made it possible for some of us to develop effective networks and to act as advisors in change processes and improvement projects.

When we, as sociologists, are confronted with “real” problems, we often find it necessary with comprehensive and holistic approaches. This is because challenges in complex organizations can seldom be traced back to one single factor. Quite the opposite, good explanations often rest on our ability to include many different variables in the analysis. When, e.g., trying to explain the causes behind a serious accident, or to find out why an organization succeeds in developing new products and processes, it can be necessary to consider both formal, technological and informal qualities, and to collect data from many parts and levels in the organization.

My personal experience, after almost 50 years of working in, for, and with different organizations, is that such holistic approaches should rest on a comprehensive analytical model that makes it possible to collect, categorize and analyze data in a systematic manner. The way we organize and present our data and conclusions should also be such that it can be communicated to people in the organization who are not trained as social scientists.

This paper describes such an analytical model for holistic analysis of organizations, which I have called The Pentagon Model. This model, which has been developed and refined during the last two decades, has over the years been extensively used both by researchers and students, mostly in applied research and in master thesis, but also in more basic research. Most of these works are only available in Norwegian, but some examples in English are included in the Appendix.

A pentagon is a plane geometrical figure with five angles and five straight sides. The word has its origin in ancient Greek: pentagonon, where penta = five and gonia = angle. The concept is based on experience from both basic and applied research, which has demonstrated that most issues concerning qualities and capabilities can be fruitfully analyzed by sorting influencing elements into five interconnected main categories, named respectively formal structure, technology, culture, interaction, and social relations and networks. All these elements are well-known themes in organizational theories and research literature, as well as in general sociology.

The model was first applied in a causal analysis after a major accident on the Norwegian shelf – the Snorre A gas blow–out in 2004. The overall findings revealed that the blow-out was a consequence of a gradual weakening of safety barriers and reduced organizational resilience and a result of a complex interplay between formal, technological, cultural, interactional and social factors. It became obvious that a multi-factorial approach was necessary to analyze and understand this intricate empirical material. The Pentagon model, built on an earlier model by Schiefloe (2003), was refined and applied for this purpose (Schiefloe 2005; Schiefloe and Vikland 2006, 2007). The Snorre A project is further described in the Appendix.

There are many theoretical models available for organizational research. Some of the most well-known are referred to later. Common to most of the models is that they point to the interconnectedness between different factors, both formal and informal, some also including external influences. Even if the models can reveal important insights, it is, in most cases, unclear how they should be applied for delving into specific problems and challenges. The Pentagon model aims to offer a solution to this challenge by making it possible to focus on specific issues and to include “all kinds” of relevant variables in explaining the actual performance or organizational quality.

The paper consists of four parts: (1) Modelling elements of organizations, (2) Analytical approaches, (3) The Pentagon Model, (4) Appendix.

2 Modelling Elements of Organizations

One of the classic texts in organization theory is Gareth Morgan’s “Images of Organization” (1986), where the basic premise is that ”theories and explanations of organizational life are based on metaphors that lead us to see and understand organizations in distinctive yet partial ways” (p. 12). Seven such metaphors are named: machines, organisms, brains, culture, political systems, psychic prisons, and instruments of domination.

Metaphors, or analytical frames, draw our attention towards specific aspects of an organization and can help us in highlighting and understanding certain aspects of the phenomenon we are studying, e.g., work processes, culture, or politics and conflicts. In some cases, one metaphor or frame is “sufficient” to shed light on the questions in focus. In other cases, a more diverse approach is necessary, because metaphors or frames may also have a restricting effect. Morgan (1986: 13) says that this is because a certain frame or metaphor produces a kind of one-sided insight, and in highlighting certain interpretations, tends to force others into a background role. Based on this reasoning, Morgan argues in the concluding chapter, “Developing the Art of Organizational Analysis”, that any realistic approach to organizational analysis must start from the premise that organizations can be many things at the same time. To truly understand an organization, it will therefore be necessary to take as a starting point that organizations are complex, ambiguous, and paradoxical.

A similar message can be found in another classic, Bolman & Deal’s “Reframing organization” (1984, 2008), where the authors argue for “multiframe thinking”, where interpretations of organizational reality can be approached from different viewpoints. Sometimes this means that an organization at the same time can be seen as a machine (structural frame), family (human resource frame), jungle (political frame) and theatre (symbolic frame).

What is often needed to understand an organization in a comprehensive way is analytical models that include as many as possible of the relevant aspects or dimensions, thereby creating a manageable picture that helps us grasp the complexity of the overall organizational system.

Burke (2011: 191) points to five ways in which an analytical organizational model can be useful: (1) it can help to categorize bits and pieces of information into a limited set of categories, (2) it can enhance our understanding when organizational challenges are rooted in one or several of the main categories of the model, (3) it can help to interpret data about the organization, (4) it can provide a common, shorthand language, and (5) it can help to guide action for change.

There are several well-known models of organization that can be applied for comprehensive analysis. Some of the most well-known are briefly described below:

One of the classics is “Leavitt’s diamond”, which is depicted with four corners: structure, task, technology, and people, and with interconnections between these (Leavitt 1965). Leavitt’s main point is that these four components interact and are dependent on each other in such a way that changes in one of them affect all the others, and that balancing and aligning the components is crucial for successful change management.

Scott (1981: 13–18) builds on Leavitt’s model, but with some minor conceptual modifications (task = goals, people = participants, structure = social structure). Scott says that social structure refers to all patterned and regularized aspects of relationships between participants in an organization. This includes (1) a normative structure, containing values, norms and role expectations, (2) a behavioral structure; activities, interactions and sentiments that exhibit some degree of regularity, (3) a formal social structure with defined social positions and relationships, and (4) an informal social structure. Participants are those individuals who contribute to the organization. Goals are defined as conceptions of desired ends, whereas technologies consist of machines and mechanical equipment, but also include technical knowledge and skills.

While Leavitt’s original model treats the organization as a closed system, Scott emphasizes that the organization’s environment should be included in the model, because every organization exists in a specific physical, technological, cultural and social environment to which it must adapt. A somewhat similar perspective is presented in Hatch’s “model for the concept of organization” (Hatch and Cunliffe 2006: 19). In this model, four intersecting circles represent a basic set of interrelated phenomena: social structure, culture, physical structure and technology, all contained within a specific external environment. In addition, Hatch identifies power as something that infuses all these aspects.

A common viewpoint within the contingency perspective is that an organization is an open system comprised of a set of sub-systems, where each sub-system takes care of certain necessary functions, and where certain attributes of each subsystem correspond to the environment to which the organization must adapt (Lawrence and Lorsch 1967). Five subsystems are commonly described, where each of them can be characterized as a continuous variable (Burrel and Morgan 1979: 169; Morgan 1986:63): The managerial subsystem ”controls” the organization and the mechanisms for internal coordination. The strategic control subsystem sets goals and directions and contributes to balancing between the organization and its environment. The operational subsystem - “technology” contains the production and work processes. The human and cultural subsystem consists of the participants within the organization, with their needs, motives, and interests. The build-up and functioning of the formal structure are described as the structural subsystem.

The consultancy firm McKinsey introduced in the late 1970s the 7-S Model as a framework «to address the critical role of coordination, rather than structure, in organizational effectiveness» and is marketed as «an important tool to understand the complexity of organizations» (McKinsey 2008). The 7-S model portrays seven basic elements of an organization: strategy, structure, systems, shared values, style, staff, skills, and shared values. These elements can be classified into two groups – «hard» and «soft». The «hard» ones are structure, systems, and strategy, whereas skills, staff, style and shared values constitute the «soft» side. Visually, the model is illustrated as a circle, with interconnecting lines, and with shared values in the centre. This underscores that all the elements are important, and that they cannot be arranged in a hierarchy. The model has, since the introduction, been widely used to analyse organizational qualities and for organizational development, also by academics. An example is Chmielewska et al. (2022) who studied public hospitals in Poland and concluded that social factors were most important for improving organizational performance, whereas technical elements as strategy, structure and system, had limited effects. Another example is Cox et al. (2018), who used the 7-S model to identify barriers for successful performance in academic libraries.

Another model, well-known in consultancy milieus, is Weisbord’s “six-box model” (Weisbord 1976). Weisbord says that this model is an outcome of several years of experimenting with “cognitive maps” of organizations, an endeavor he started when he realized that he knew a lot of organization theories, but that most theories were either “(1) too narrow to include everything he wished to understand, or (2) too broadly abstract to give much guidance”. The model provides six labels: purposes, structure, relationships, rewards, leadership, and helpful mechanisms, under which one can sort most of what is going on within an organization, and that allow people “to apply whatever theories they already know in doing diagnosis and to discover new connections among apparently unrelated events”.[1] The six-box model is used in organizational diagnostics to map formal and informal elements, not only for practical, but also for and academic purposes. An example is Zhang et al. (2016), who combined the six-box model with a growth management model to identify growth influence factors in a Chinese petrol company.

Other comprehensive models are Nadler & Tushman’s “congruence model” that points to four basic elements: culture, work, structure, and people (Nadler and Tushman 1980, 1997), and Harrison’s model of organizations as open systems, with the elements purposes, culture, technology, structure, and behavior and processes (Harrison 1987: 24).

When we, as researchers or practitioners, are trying to understand or improve the qualities or performances of complex organizations, we are often facing many-faceted issues, where neither causes nor effects can be reduced to one or a few factors. It is therefore important to analyse organizations as nuanced social phenomena with plural social facets. All the models referred to above are developed as tools to deal with such challenges. Common is that they underscore the necessity of holistic and comprehensive analytical approaches. A perspective shared by all is also that the different factors, or elements, are interconnected and influence each other. These basic insights also form the foundation of the pentagon model.

Even if the models may use different words, we find that they, to a large extent, contain many of the same organizational elements, some of a formal and some of an informal character. The decided formal organization, the formal structure, is highlighted as an important element in all the models mentioned above. Another important element that can be decided, technology, is underscored by Hatch and Cunliffe (2006), but is not mentioned in the majority of models. Some of the models also include factors as goals, strategy and external forces. The descriptions of the “undecidable” informal elements are varied, including factors as people, culture, relations and leadership.

Looked upon from a managerial perspective, formal elements, such as structure, strategy and technology, can be planned and controlled. Informal elements, such as culture and personal networks, are to a large extent beyond managerial control. As experience shows, they can, however, be influenced.

3 Analytical Perspectives

Organizational analysis can be approached on different levels, dependent on the locus of interest, or on what kind of phenomena a manager, consultant or researcher is trying to understand and/or cope with. Scott (1981: 10–11) distinguishes between three analytical levels, where the level chosen in each case will be determined by whether the phenomenon to be explained is (1) the behavior or attributes of individual participants, (2) the functioning or characteristics of some specific aspect or segment of the organizational structure,, or (3) the characteristics or actions of the organization viewed as a collective entity.

Following Scott’s classification, research focus on the individual level will be on explaining the behavior and attitudes of individual actors, alone, or as participants in groups and networks, within an organizational context. Scott names the second level “structural”, but as this may be interpreted in a restricted way as “formal structure”, it is better to use the term collective level. Research on this level may focus, e.g., on the situation in formal or informal subunits, authority and power, work processes, or operational quality. At the third level – system level – focus is typically on the overall system’s qualities or performance, in total, or in specific areas.

A general assumption which is common to diagnostic models is that these three levels are interconnected, and that interactions occur between individual, group/collective and system levels (Sabir 2018). Realizing that organizations are open systems, a fourth analytical level may be named ecological, studying the organization as an actor within a larger business and/or political macrosystem. Taking the multilevel perspective into account, one more requirement for an organizational model can then be added: it should be applicable for performing empirical analyses on both individual, group, system, and ecological levels.

When working with “real” issues in organizations, especially in applied research, the questions we face connected to these different analytical levels can usually be sorted into two different, but mutually dependent categories: qualities and performance. Or put in more daily terms: “How good are we?”, and “How are we doing, in general or in a specific area?”

We also meet questions connected to different time perspectives: past, present, and future. Typical backward-looking issues are: “why did this serious incident happen, and what were the root causes?”, or “what factors contributed to our success in handling an unexpected challenge?” Examples of present-day challenges may be: “Why are some of our departments more innovative than others?”, or “what factors are important for obtaining operational safety on the oil platform?” A forward-looking question can be: what are the organizational preconditions for successful implementation of a new IT system and corresponding work processes?

The Snorre A case, which is described later, illustrates that the pentagon model can be applied on all the three analytical levels: In the causal analysis we had to explain why the drilling operators misinterpreted the signals from the well, believing that the observed disturbances was due to a “gas kick”, not understanding that a massive blow-out was under way, i.e. individual level. In explaining why the crew decided not to evacuate the platform, as they should have done according to the safety regulations, we found that the most important factors were a high level of social capital, mutual trust and comradeship, i.e. collective qualities. One of the main reasons for initial mistakes in the planning of the drilling operation was that the Snorre organization, due to a recent take-over, was “socially isolated” within the larger Statoil system.[2] Lacking access to larger networks, the participants in the planning unit had limited access to experience and advice from other platforms, i.e. an attribute of the company’s informal knowledge system (Schiefloe 2005).

The causal analysis dealt with the past: What caused the blow-out, and how was it handled? A follow-up study 18 months later evaluated the effects of measures undertaken after the initial report. This evaluation focused on the present: How is the situation today, regarding general resilience and robustness in drilling operations? Part of the story is that since then, there have been no serious accidents on Snorre A. The two Snorre A reports were also forward-looking, coming up with general insights and advice for improving safety, especially concerning structure, culture and interaction. These insights have proved to be relevant, not only for the Snorre field, but also for other offshore installations (Schiefloe 2007).

4 The Pentagon Model

Common for the models of organizations referred to above is that they include both formal, decided (“hard”), and informal, undecided (“soft”) attributes, that they point to the interconnectedness between different factors, that organizational outcomes are functions of the interplay between formal and informal elements, and that they treat organizations as open systems that are dependent upon and interact with their environments.

The challenge we face as researchers is to combine the different organizational elements identified in the research literature into one operational model. Burke’s list, referred to above, points to important attributes of a good model. For a model to be really useful, however, four more requirements can be added: (1) it should be pedagogical and easy to understand, so that it can be applied not only for scientific purposes, but also by practitioners and “ordinary” organizational members, (2) it should be comprehensive and shed light on interconnectedness and dependencies between different organizational phenomena and attributes, (3) it should be applicable for performing analyses on different levels, and (4) it should open for use of relevant theories and insights from other social science fields, e.g. communication theory, network theory, theories of action and theories of power.

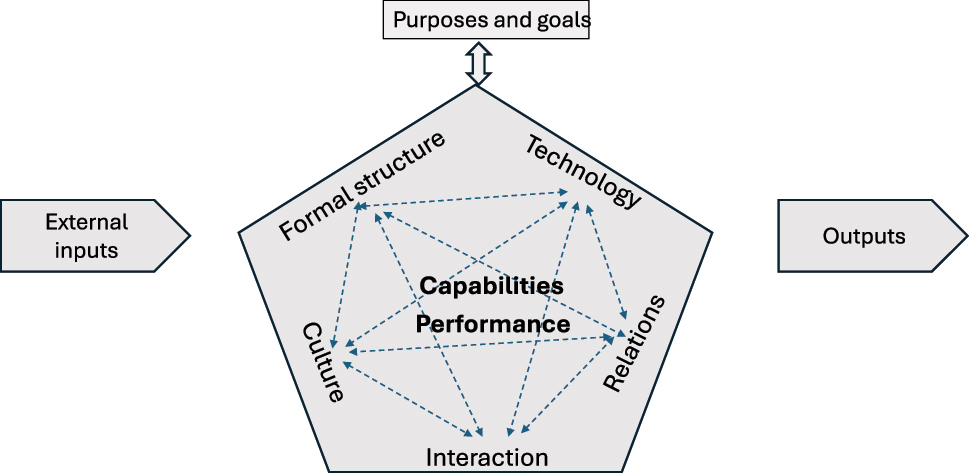

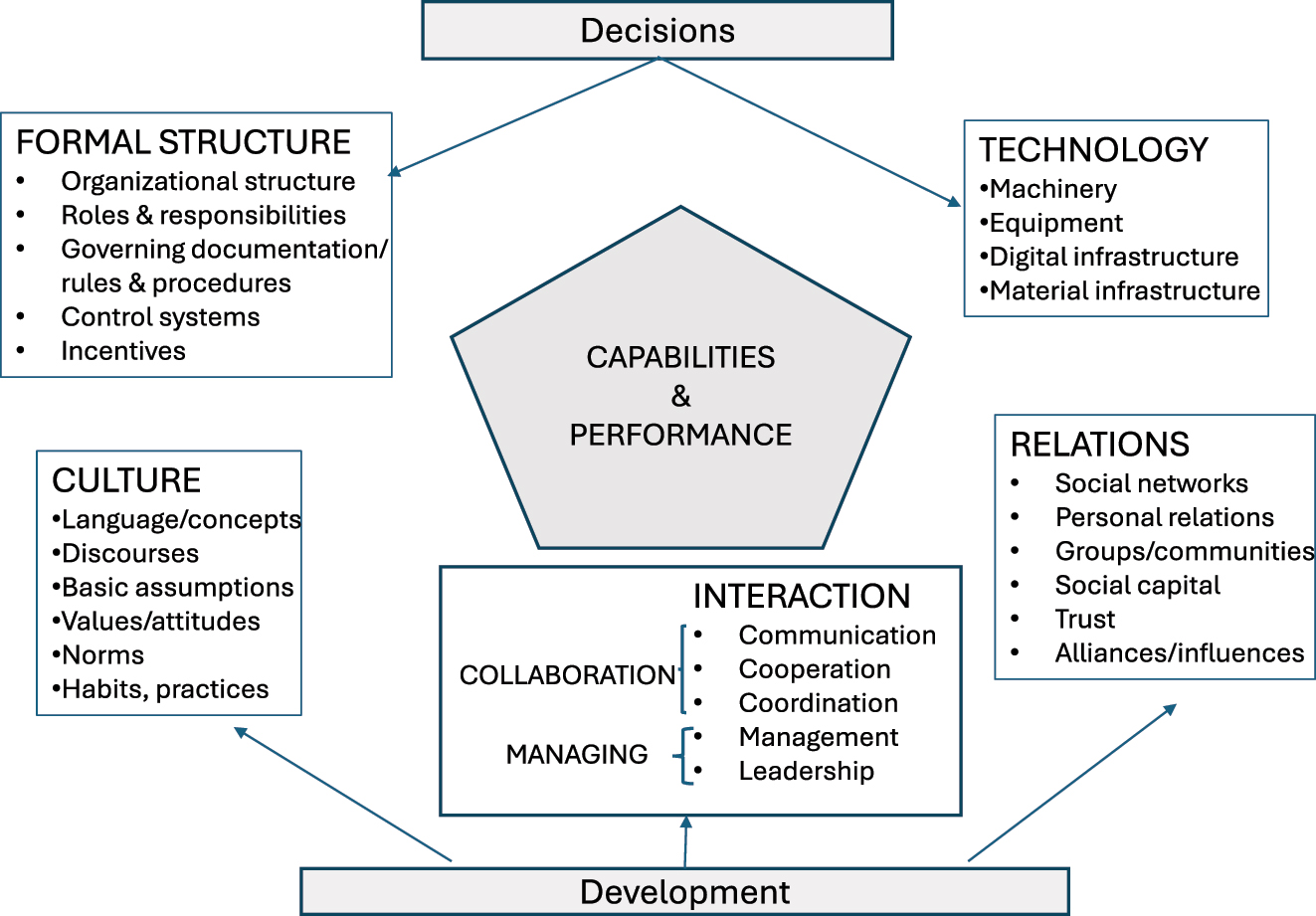

Based on many years of both basic and action-oriented research and development activities, an experience-based, and empirically tested in both basic and applied research projects, the conclusion is that the most important organizational variables can be subsumed under five broad headings, covering both formal and informal dimensions. These headings are also in line with the main variables in the referred models, and are, respectively, formal structure, technology, culture, interaction, and (social) relations. These five factors are closely interrelated and influence each other, but they may also be investigated separately. The relative importance of each of them varies, depending on the situation in the organization studied, and on what kinds of capabilities or performance are in focus. The term capabilities here refers to inherent or relatively permanent organizational qualities, whereas performance refers to specific incidents or activities. An example of a capability can be the organization’s ability to come up with innovations and new solutions. Performances can refer to both past, present and future situations (Figure 1).

Pentagon model of organization.

I have chosen the term “pentagon” because, as the figure above demonstrates, the five analytical dimensions are interdependent and can influence each other. They are not arranged hierarchically, and together they form a framework for analysis where the problem in focus is placed in the middle. The five elements of the model are briefly described below. As illustrated in the figure, the organization also interacts with and is dependent upon its environment, both for inputs and outputs. Purposes and goals are placed partly outside the pentagon, because they, in a specific situation, can be regarded as external factors, e.g., as formulated by private or public owners. The five basic sets of factors are briefly described below, each of them containing a set of more precise variables.

4.1 Formal Structure

Mintzberg (1979: 2) defines the (formal) structure of an organization as “the sum total of the ways in which it divides its labor into distinct tasks and then achieves coordination among them.” He further states that the structure must be adapted to the complexity in the organization’s tasks and the level of stability in the organization’s working environments, and that different organizational configurations are suited for different situations.

The structure is the outcome of an organizational design process composed of four broad groupings of design parameters: (1) design of positions, (2) design of superstructure, (3) design of lateral linkages and (4) design of decision-making system (Mintzberg 1983). From this follows three sets of important questions that must be answered in designing the structure:

How shall different tasks be allocated to different positions, how standardized shall the working procedures be in connection with these tasks, and what skills and knowledge shall be required for each kind of position?

How shall positions be grouped into units, how large shall the units be, how shall these units be grouped into larger units, such as departments or divisions, and what mechanisms shall be established to handle communication, adjustments and alignment within and between units?

How shall decision-making power be distributed, and what kind of formal procedures should be established to govern decision-making processes?

Ahrne and Brunsson (2011: 85) state that decisions are the most fundamental aspect of organization and define organization as “a decided order in which people use elements that are constitutive of formal organizations”. Decisions represent conscious choices by decision-makers on the allocation of tasks and how people in different positions should act. Kühl (2018: 18) says that such decided membership conditions constitute the organization’s formal structure – “the fixed or decided decision premises of an organization”. According to Ahrne and Brunsson (2011: 85), there are five constitutive elements of the formal structure: membership, hierarchy, rules, monitoring of activities, and the right to decide about positive and negative sanctions.

The formal structure is usually depicted as an organization chart, which illustrates how tasks and responsibilities are divided between departments and roles, and how formal power is situated on different organizational levels and between functions. Supplementing the organization chart are typically governing procedures, regulations, role definitions and working requirements. Other formal elements found in most organizations are budgeting and reporting routines, decision-making mechanisms, and incentive structures. The term formal structure then covers what is sometimes spoken about as “organization”.

Luhmann says that there can only be “one consistently planned, legitimate formal order of expectations” in organizations (Kühl 2018: 19). But as well-known, both from practice and theory, organizations also have an informal dimension, which may be described as relations, expectations and activity patterns that are not reflected in the organizational chart or in the governing documentation, but that may have profound influence on the organization’s qualities and operational outcomes. The fact that much of what takes place within a formal structure is unorganized is often described as “informal organization”. Kühl (2018: 19) characterizes such informal aspects of organization as “undecidable decision premises”.

4.2 Technology

Technology refers to the machinery, equipment and ICT systems that organization members are dependent on or use to perform their activities. In a wider sense, technology can also be said to include the organization’s material infrastructures. We can also talk about this factor as materiality.

Technology is important for understanding organizational phenomena in a broader sense, both on systemic and individual levels. Or to put it simpler: We can often not understand how an organization functions without taking technology into consideration, because there are close links between technology and formal structure as well as between technology and informal attributes: culture, interaction and relations. Technology is also an important factor when it comes to individual behavior and performance.

A prominent example of the importance of technology is Woodward’s classical study of the connection between technology and formal structure in successful organizations. Her main finding was that different production systems imposed different demands, which should be met by appropriate structural arrangements: Mechanistic and bureaucratic systems might be useful for companies with mass-based production technologies, whereas companies with unit-based and continuous-based technologies needed more flexible and organic structures (Woodward 1965). Another classic example is the Tavistock studies of mining technologies in the 1950s which laid the foundation for the development of socio-technical theories, with the core idea that organizational performance only can be understood, and improved, if both social and technical aspects are taken into consideration, and that technology must be adapted to the people using it.

An influential direction in the study of technology is the STS theory (Science and Technology Studies) which is an interdisciplinary field focusing on the interplay between science, society and technology. Important contributions are the Social Construction of Technology (SCOT) – studies, which take as a starting point that technologies are shaped by social groups and through negotiations. Important within this group of studies is Actor-Network Theory (ANT), which focuses on “networks” including both human and non-human “actors” (Latour 1987; Pinch and Rijker 1987).

Most writers within the field of organization and management in the last 50 years have, however, tended to ignore the impact of technology/materiality. A quote from Wanda Orlikowski’s essay Sociomaterial Practices: Exploring Technology at Work illustrates the point:

In this essay, I begin with the premise that everyday organizing is inextricably bound up with materiality and contend that this relationship is inadequately reflected in organizational studies that tend to ignore it, take it for granted, or treat it as a special case. The result is an understanding of organizing and its conditions and consequences that is necessarily limited (2007: 1435).

A search through well-known organization textbooks confirms Orlikowski’s argument; topics like production technology, ICT as tools for process control and communication, and the general impact of the material infrastructure are usually omitted. This situation also reflects the dominating research agenda: Zamutto et al. (2007: 750) found that between 1996 and 2005 only 1,2 % (14 of 1.187) of the research articles in three of the field’s top journals[3] focused on the relationship between technology and organizational form and function. According to Orlikowsky and Scott (2008: 436), technology is important for organizational outcomes, for the way organizations are structured, for norms and ways of working, for capabilities to act and interact, and for learning and innovation. With the introduction of advanced ICT, the importance of technology takes on an extra dimension. Modern technology is not only a matter of “tools” operated by individuals or groups, but is to an increasing extent also a means for changing the way we work and the organizations we work in. Groth (1999) says that the effects of these technologies are “extending the space of constructible organizations”.

In recent research, we find the term sociomateriality, which is used to describe the complex interaction between technology, material infrastructures, organizational attributes and human action. For Orlikowski, “there is no social that is not also material, and no material that is not also social (Orlikowski 2007: 1437). A logical consequence of this insight is a movement away from asking how technology influences humans, to examining how technology and materiality are intrinsic to all kinds of organizational activities and relations. Materiality also has a cultural component. A trivial example is how size, design and furniture in offices mirror power and status differences and, as such, reflect dominant cultural values.

In empirical research, it is often useful to specify technology as machinery, equipment, digital infrastructure and material infrastructure.

4.3 Culture

Deal and Kennedy (1982: 49), who were among the first to put culture on the agenda of organizational research, say that organizational culture simply can be understood as “the way we do things around here.” Reason (1997: 192) elaborates this understanding by saying that culture is: “Shared values (what is important) and beliefs (how things work) that interact with an organization’s structures and control systems to produce behavioral norms (the way we do things around here).” A more thorough definition is presented by Schein (1991: 247), who says that culture is “(1) a pattern of shared basic assumptions, (2) invented, discovered, or developed by a given group, (3) as it learns to cope with its problems of external adaption and internal integration, (4) that has worked well enough to be considered valid, and, therefore, (5) is to be taught to new members of the group as the (6) correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.” Kühl (2018: 8) takes a somewhat similar perspective, when he says that “an organizational culture is comprised of expectations of the behavior of the organization’s members.” He further states that such expectations emerge slowly and through repetitions and imitations, and that they are not made by through official management. Organizational culture can therefore be described as “those decision premises in organizations about which no decisions have been made” (2018: 14). Important to note, however, is that expectations do not function as precise recipes for correct action, instead they supply the “room for de facto behavior”, which, according to Luhmann, means that “you have to act within the channels mapped out and made acceptable by expectations” (2018: 15).

Both Deal and Kennedy, as well as Reason and Schein, are representatives of an integration perspective on culture. Looked upon this way, culture is perceived as something clear, unambiguous, and mostly shared by all members of the organization. An example is Reason’s description of an “ideal safety culture”, which is said to be characterized by reporting, just, flexible and learning (1997: 195). From such a perspective follows logically that culture can be “engineered” by a combination of structural arrangements and good leadership. Martin argues against this and points out that one cannot take for granted that an organizational culture can be described as an integrated unity. More often, at least in large organizations, cultures are either differentiated or fragmented. A differentiated culture is typically characterized by several subcultures, which may differentiate along occupational or organizational lines or have their origin in personal networks or demographic identities, e.g., gender, age, or ethnicity. Consensus and common interpretations exist primarily within subcultures, whichby may exist in harmony, independently, or in conflict with each other. A fragmentation perspective underscores that cultural manifestations may be unclear and ambiguous, there may be multiple views on many issues, and those views may be in a constant flux (Martin 2002).

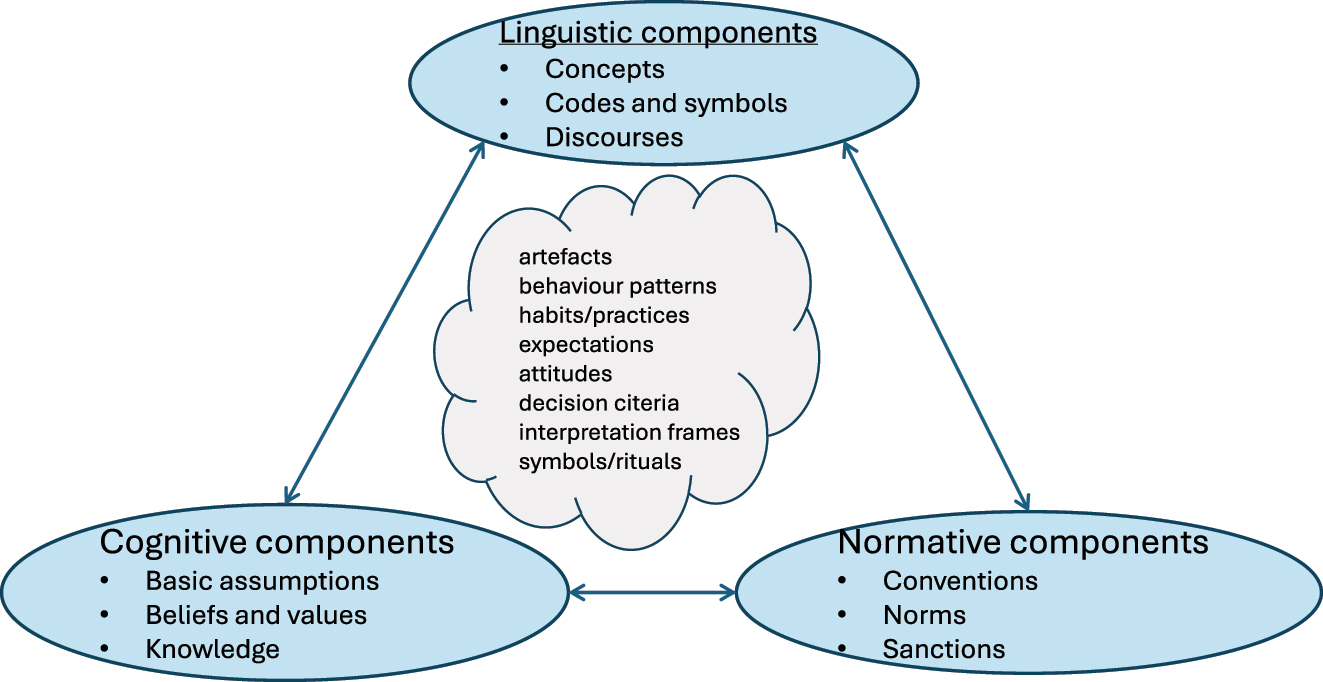

When doing research in field situations, we meet local culture in different ways, as assumptions, beliefs, norms and interpretations. We can observe it in behaviour and material manifestations, and we can listen to it by paying attention to what people say, and not say, and how they express their meanings. After many decades as a researcher, management advisor and consultant, in both small and large organizations, at all levels ranging from top executives to the ground floor, I have concluded that for analytical purposes, and as guidelines for empirical research, one can say that culture is made up of three sets of components: linguistic, normative and cognitive. The linguistic components define the frames of verbal expressions and discourses; what one has words for, can talk about and discuss. The normative components define what is allowed or accepted, and what positive and negative reactions certain kinds of behavior shall be met with. In the organization, this is manifested in conventions, norms and sanctions. Cognitive components act as a framework that guides attention, interpretation, sensemaking, evaluations and decisions, and may become visible as basic assumptions, beliefs, values, and knowledge. In an organization, we can observe the outcomes of these three basic components directly, but also indirectly in cultural traits as artefacts, behavior patterns, habits and practices, expectations, attitudes, decision criteria, frames for interpretation, symbols and rituals (Figure 2).

Components of culture (Schiefloe 2021: 120).

To what extent a certain organization is characterized by a specific internal culture is an empirical question. In some organizations, culture plays an important role, whereas in other organizations it is of lesser importance. The impact of culture will often relate to the organization’s history and accumulated experiences, recruitment patterns and the degree of turnover. Schein (1991) also points to the lasting impact of the founder’s assumptions and beliefs.

4.4 Relations

The well-known Hawthorne studies, carried out between 1924 and 1932, were the first to shed light on the importance of personal relations and informal social structures for organizational performance. By observing workers who produced telephone equipment in the “bank wiring room”, the researchers found that informal groups both developed rules of behavior as well as means to enforce them. Some of these rules set standards for “a fair day’s work”, whereas other rules served to control the interaction between the workers and their bosses. The Norwegian sociologist Sverre Lysgaard later described similar mechanisms and coined the observed informal structure as a “workers’ collective” (Lysgaard 1961). The workers’ collective served as a protective mechanism – a buffer – between the workers and the demands from the technical-economic system.

These and other early studies of informal social structures were targeted at workers “on the floor”, and from a management perspective, the existence of such mechanisms could be seen as a problem which reduced managers’ influence and control. With the development of theories and methods for systematic network studies, which took place some decades later, it gradually became clear that the existence and importance of informal social structures in organizations were not restricted to those at the bottom of the formal hierarchy. Nohria and Eccles (1992: 4) state this clearly: “All organizations are in important respects social networks and need to be addressed and analyzed as such.” Extensive research during the last 30 years has demonstrated the relevance of this statement; informal social relations and social networks pervade organizational life, are the basis for alliances and power, influence capabilities such as knowledge sharing, learning and innovation, and influence individual behavior on all levels, as well as the way the overall system functions. An illustration is the title of a book by Cross and Parker (2004): The Hidden Power of Social Networks. Understanding How Work Really Gets Done in Organizations.

Four basic principles are at the core of a social network approach to organizations (Kilduff and Krackhardt 2008: 14). The first is a focus on the importance of relations between actors, to understand interaction within the organization. The second is the emphasis on embeddedness, understanding human behavior as embedded in networks of interpersonal relationships. The third is realizing that social relations within a network are the basis of social capital, whereas the fourth has to do with analyzing the importance of the informal structural patterning within the organization.

Networks in organizations can be studied both by qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative approaches are useful for studying how networks are functioning and what role they play, for individual members as well as for the way the organization works. Quantitative approaches are used to get an overview of the informal social system and how this is built up and functions. Wellman (1988: 26) uses the term whole network studies for a structural approach mapping the comprehensive structure of relationships within a social system. The strength of such an approach is that it at the same time gives an overview of the social system (the organization) as well as of the relational location of each of the participants (the members, the employees). By different kinds of techniques one can then find patterns of connectivity and cleavage, structurally equivalent positions within the system, and how system members are directly and indirectly connected. One can also identify centrally located individuals, cliques and clusters. Many organizations now regularly employ organizational network analysis (ONA) to get a picture of the intraorganizational networks, communication and cooperation patterns, and the outcomes of social capital.

Early works on informal structures focused almost solely on their controlling and restraining effects. More recent studies with a wider scope have illustrated how participation in networks may also contribute positively to capabilities and performance by giving access to resources such as knowledge, information, and general social support. On the individual level, several studies have shown how informal relations may be beneficial not only for work, but also for career development. Participation in local networks is also crucial for identification and sense of belonging, and thereby also for turnover (Cross and Parker 2004; Cross and Thomas 2009; Cross and Velasquez 2010; Hekscher and Adler 2006).

It is important to recognize that social capital goes beyond individuals and has a collective dimension. Or, to say it with Putnam: It has both a private face and a public face (Putnam 2000:20). Leana and Van Buren (1999: 538) define social capital in organizations as “a resource reflecting the character of social relations within the firm…(which) is realized through members’ level of collective goal orientation and shared trust, which create value by facilitating successful collective action.” Two basic components of organizational social capital are associability and trust. Associability is defined as the participants’ willingness to subordinate individual to collective goals, whereas trust is said to be both an antecedent to, and a result of, successful collective action. They further point to four primary ways in which organizational social capital can lead to beneficial outcomes, both for the organization and for its individual members: It (1) justifies individual commitment to the collective good, (2) facilitates flexibility, (3) serves as a mechanism for managing collective action, and (4) facilitates the development of intellectual capital (1999: 547).

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) make a distinction between three main dimensions of social capital in an organization. The structural dimension describes the configuration of linkages between people, or what we may call “the network map”. The relational dimension covers the kind of personal relationships people have developed through a history of interactions, such as respect, friendship and trust. An important facet within the relational dimension is the existence of mutual obligations between parties. The cognitive dimension refers to shared representations, interpretations and systems of meaning.

Most studies on networks and social capital in organizations have focused on positive outcomes, but in some cases, one can also find negative effects. Burt (2005: 7) points to possible disciplining and restraining impacts in describing what he calls “network closure”, which “increases the odds of a person being caught and punished for displaying belief or behavior inconsistent with preferences in the closed network”. Two possible consequences of closed networks within an organization may be the constraining of individual freedom of action and the exclusion of knowledge originating elsewhere. Actors may also be restricted in their opportunities by negative ties, competition and conflicts.

Many studies have demonstrated the importance of trust for sustaining individual and organizational effectiveness (McAllister 1995). Trust acts as a “psychological lubricant” for smooth social processes (Igarashi et al. 2008: 88). It makes it easier to cooperate, contributes to reduced transaction costs, reduces the potential for conflicts, facilitates formulation of ad hoc groups, and promotes effective responses to crisis (Rousseau et al. 1998: 394). The opposite can be experienced in situations characterized by a lack of trust or outright distrust. In such cases, people will stick to themselves, guard their steps and be careful with what they say. Cooperation will be difficult, and transaction costs will be high.

Social relations and networks – the informal social structure – are a phenomenon that is closely connected to organizational culture. Values, norms and established ways of behavior influence the way people behave towards each other and what kind of relations are expected and accepted. On the other hand, organizational culture is developed and maintained within social networks and is managed and influences attitudes and behavior through social relations. Both culture and social relations are sources of resources as well as of constraints. Taken together, we can say that these two elements constitute a sociocultural field within the organization. Individual actions, as well as interactions involving several individuals, take place within this field.

Relations and networks are also important additions to formal power positions. Because “getting things done in an organization involves working through a complex network of individuals and groups” (Bolman and Deal 2008: 204). In a discussion of preconditions for effective change processes, John P. Kotter emphasizes the importance of creating a “guiding coalition”. This is especially important in today’s rapidly changing business environments, where “only teams with the right composition and sufficient trust among members can be highly effective” (Kotter 2012:57). Social relations and networks also form the basis for coalitions and alliances and can play important roles in competitions and conflicts.

4.5 Interaction

Mintzberg (1983: 2) points out that every organized activity gives rise to two fundamental and opposing requirements: the division of labor into various tasks and the coordination of these tasks to accomplish the activity. Another way of stating this is to say that the basic organizational process is interaction: people divide responsibilities and work between them and combine efforts to achieve specific goals.

Interaction has to do with actors consciously relating to each other and is the basic component in work processes. Interaction is a precondition for developing and maintaining social relations and networks, and is also a foundation for organizational culture, experience transfer and learning. In analyzing organizations and organizational phenomena, four specific forms of interaction should be subject to special attention: cooperation, communication, coordination and managing.

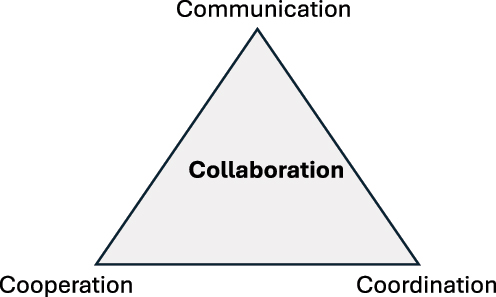

To cooperate can be defined as “to work with another person or group to do something”, or “to act in a way that makes something possible or likely: to produce the right conditions for something to happen”.[4] The terms cooperation and collaboration are often used interchangeably, but it is more accurate to say that collaboration is a specific form of cooperation, where the participants also have some kind of shared or common goal. Bedwell et al. (2012: 134) argue that it is the existence of such a shared goal that is the key element separating collaboration from other forms of shared work. In line with this, they define collaboration as “an evolving process whereby two or more social entities actively and reciprocally engage in joint activities aimed at achieving at least one shared goal” (2012: 130). Adler et al (2013) say that successful organizations can develop collaborative communities, which are formed when people work together to create shared value. People participating in such communities are motivated by a collective mission, not just personal gains or intrinsic pleasures. Collaborative communities also rest on a common cultural foundation, sharing “a distinctive set of values, which we call an ethic of contribution” (Adler and Heckscher 2006: 49).

Interaction is dependent on communication, which, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, can be defined as the exchange of meanings between individuals through a common system of symbols. A traditional understanding of communication – the Shannon-Weaver model – explains this as a process containing a set of three basic elements: A sender who encodes thoughts or feelings into a message, which is conveyed to a receiver by means of a channel, whereafter the receiver decodes the message. The channel used to communicate influences the variety of verbal and non-verbal symbols that may be used. An example is that face-to-face conversations are different from the exchange of e-mails. An earlier understanding of communication described this as a one-way process. Today, scholars agree that communication activities are better represented by a transactional communication model, which reflects the fact that the participants send and receive messages simultaneously, and that the behavior of the parties is continually influenced by the feedback they receive (Adler et al. 2001).

All communication takes place within a social and cultural context that influences ”how individuals enact, interpret, and respond to listening behaviours and their perceptions of responsiveness” (Itzchakov and Reis 2023: 2). Effective communication within an organization therefore takes place within specific cultural surroundings and is dependent on the degree of linguistic unity, i.e. the extent to which people use “the same language” and within shared frames for discourse.

National linguistic differences are easy to observe, but within an organizational setting, there may also be professional jargon and different “dialects” which make communication across departments and groups problematic. A general observation from many organizations is that the importance of common vocabulary and agreed-upon discourses is often underestimated.

Malone and Crowston (1994: 90) define coordination as: “the act of managing interdependencies between activities”. The dependencies that may have to be managed to obtain coordination of activities within an organization can be of different kinds. Four main types are:

Resource dependencies (when multiple activities share some kind of limited resources).

Sequential dependencies (producer–consumer relationships/output–input, dependencies).

Simultaneity constraints (when activities need to occur at the same time, or the opposite: cannot occur at the same time).

Task dependencies (several activities are “subtasks”, which contribute to a common goal/product).

As Mintzberg (1979) points out, coordination in organizations may be achieved by different kinds of mechanisms. Much literature has focused on structural mechanisms, such as standardization and bureaucratic routines. Schiefloe and Syvertsen (1998: 17) use the term constitutive coordination, which is described as a series of steps: “decomposition of goals, operationalization of goals into specified activities, assigning activities and responsibilities to actors, establishing procedures for handling activities and merging part results into wholes”.

Jarzabkowski et al. (2012: 907) point, however, to the fact that” coordinating mechanisms are dynamic social practices that are under dynamic construction”. From this follows that the analytic focus should be shifted from coordinating mechanisms as reified standards, rules and procedures to studying such social practices. Schiefloe and Syvertsen (1998) describe such dynamic practices as concurrent coordination, where focus is shifted from predefined procedures and fixed roles to problem solving, relations and involvement. This is in line with Okhuysen and Bechky (2009: 463), who define coordination as “the process of interaction that integrates a collective set of interdependent tasks” and can be described as “ongoing work activities that emerge in response to coordination challenges” (2009: 468).

If we consider collaboration as the most general term, we can say that successful collaboration depends on both cooperation, communication and coordination. This can be illustrated in a “collaboration triangle” (Figure 3):

Collaboration triangle.

The terms managing, management and leadership are often used interchangeably. Following Clegg et al. (2011: 8), we can look upon managing as the widest term, covering the content and expectations of the role of managers: “Managing is an active, relational practice which involves doing things. The things that managers do are supposed to contribute to the achievement of the organization’s formal goals.” Mintzberg (2011: 12) follows the same line of reasoning, defining a manager as “someone responsible for a whole organization or some identifiable part of it.”

Management has to do with the formal rationalities of the manager’s role. Clegg et al. (2011: 9) define it as follows: “Management is the process of communicating, coordinating and accomplishing action in the pursuit of organizational objectives while managing relationships with stakeholders, technologies, and other artifacts, both within as well as between organizations”. Kotter says that the most important aspects of management include planning, budgeting, organizing, staffing, controlling and problem solving (Kotter 2012:28).

In the GLOBE project, which studied culture and leadership in 62 different countries, the researchers decided on the following definition of leadership: “the ability of an individual to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute towards the effectiveness and success of the organizations of which they are members” (House et al. 2004:15). Kotter emphasizes that leadership defines what the future should look like, aligns people with that vision, and inspires them to make it happen (2012: 28).

For analytical purposes, it is possible to treat management and leadership as different aspects of managing. Mintzberg, however, argues that even if these two aspects can be separated conceptually, there is no point in doing this when it comes to practice: “…instead of distinguishing managers from leaders, we should be seeing managers as leaders, and leadership as management practiced well” (Mintzberg 2011: 8–9).

5 A Holistic Approach

Following the reasoning in general systems theory, one can say that any system is comprised of parts, or subsystems, which are both mutually dependent and interrelated, and whose relationships produce a level of order and function that transcends the sum of the parts. From this follows logically that the properties of a certain system cannot be fully understood by examining its parts in isolation. Systems theory also points to the fact that systems are nested, which means that all systems exist within higher-order systems (Hatch 2011). From this follows that we, when analyzing organizations, must take into consideration that organizations are open systems.

It is important to notice that the five factors in the pentagon are mutually dependent, and that each of them, to a greater or lesser extent, is influenced by all the others. Changes in one of the factors, e.g. formal structure, may have consequences for culture development and interaction patterns, as well as for the development and functioning of informal networks. Changes in culture may impact interaction, as well as the development of networks and social capital. The introduction of new technologies can lead to changes in communication and cooperation patterns, which again can influence informal relations, etc. The different factors in the pentagon, and the processes, capabilities and performance within the organization, are also influenced by interaction with the organizational environment: economic, political, technological, cultural and social.

The keywords under each of the headings in Figure 4 cover the main dimensions in each of the five categories, which can be used as guidelines for data collection. The lists, however, are not exhaustive and can also be further detailed. The keywords can also give some ideas of different theoretical and methodological approaches that can be applied when using the model for analytical purposes.

Foundations for holistic analysis.

Structure and technologies are formal qualities, whereas culture, interaction and relations are informal qualities. An important difference between formal and informal qualities is that formal structure and technology can be managed and decided upon, whereas cultural, interactional, and relational attributes are “undecidable decision premises” and can only be developed. Such informal qualities can be influenced and stimulated, but will never be under full management control.

6 Using the Model for Analysis

The Pentagon model can be used to study the overall capability and performance of a system, or a sub-system, in the past or present, and to what extent this can be explained by variables connected to the different Pentagon dimensions. The model can also be used for analyzing future problems and possibilities.

Focus can be on a specific capability or performance, e.g. operational safety or productivity. This can be done by putting the actual capability or performance into “the middle of the pentagon” and use the corresponding picture as a guideline for mapping possible interplay with different organizational elements. The model can also be used to map and assess organizational qualities by examining parts of the system, how these parts are connected and influence each other and how they together produce certain overall system attributes or qualities. The model is general and can be applied for studying almost any kind of organizational phenomena. In practice, a Pentagon approach can be the basis for scientific data collection and theoretically based analysis. But it can also be used as a basis for internal discussion and groupworks and development of an SWOT-analysis.[5]

Appendix: Examples of Application of the Analytical Model

The Snorre A Gas Blow-Out

Schiefloe, Per Morten and Kristin M. Vikland (2006) “Formal and informal safety barriers. The Snorre A incident” in Safety and Reliability for Managing Risk, edited by Carlos G. Soares and Enrico Zio. 419–426. London: Taylor & Francis.

Schiefloe, Per Morten and Kristin M. Vikland, (2009), “Close to catastrophe, the Snorre A gas blow-out”, paper presented at the EGOS Conference, Barcelona, July 3, 2009.

Late autumn 2004 there was a gas blow-out on the Snorre A oil platform on the Norwegian continental shelf. This resulted in an extremely dangerous situation, which developed into being very close to a major catastrophe. The later investigation by the Norwegian Petroleum Safety Authority (PSA) revealed a history of multiple failures in the process leading up to the blow-out, altogether 28 non-conformances, summed up in five main categories: failure to observe governing documentation, failure to understand and implement risk assessments, insufficient management involvement, and breaches in the requirements for well barriers. This investigation was followed by an extensive causal analysis headed by the author of this paper. The data material consisted of on-site observations and 200 h of taped interviews with 152 people from all parts of the Snorre organization, both offshore and onshore. The same sample also filled out a questionnaire, and relevant written material was also included.

The overall research question was to explain the root causes of the drift towards reduced resilience and weakened safety barriers. The overall findings revealed that the blow-out was a consequence of a gradual weakening of safety barriers and reduced organizational resilience and a result of a complex interplay between formal, technological, cultural, interactional and social factors. It became obviously clear that a multi-factorial approach was necessary to analyze and understand this intricate empirical material. The Pentagon model, built on an earlier model by Schiefloe (2003), was refined and applied for this purpose. When sorting the data material according to the five pentagon categories, a coherent picture of the factors leading up to the blow-out could be established, briefly summarized below:

Formal structure: recent and ongoing changes of operator company and drilling entrepreneur, ongoing changes in the onshore subsea planning department, and complex governing documentation, which affected large parts of both the offshore and onshore organization and resulted in time-consuming adaptations to new working conditions.

Technology: deteriorating technical standards and lack of maintenance. Important consequences were stressful working conditions and little focus on long-term planning. At the time of the blow-out, major improvement programs had just been started but had not yet had any major effect.

Culture: dominating production focus, gradually increasing risk tolerance, no acceptance or tradition for questioning decisions or plans made by the onshore organization.

Interaction: little cooperation sea-land, limited involvement of the platform in planning of drilling operations, gradually increasing bureaucratic workload for offshore managers, which diverted attention from daily operations.

Relations: weak informal integration in the operating company (due to recent takeover) and limited access to external knowledge and experience. But at the same time, there were close, long-lasting and positive relations between the people on board. These interpersonal qualities were the positive elements in the picture: When the blow-out was a fact, most of the crew evacuated to nearby platforms. But 35 people volunteered to remain on board, where they worked all through the night, under extremely demanding conditions and facing a considerable personal risk. Illustrative is the fact that they considered full evacuation three times, each time deciding to keep on fighting. In the morning, after several unsuccessful attempts, the well was brought under control, in the “very last minute”, and the blow-out was stopped, without causing any human injury or environmental damage. When asking why they volunteered to stay, despite the risk, the answers could be summed up in a few points: social integration, personal networks developed over many years, sense of belonging, and trust in the platform manager. Or in other words, local culture and social capital.

The Pentagon approach was also extensively used in the later dissemination process of the research report, on all levels in the operating company, from the executive board to the people on the platform floor. Following up, an extensive improvement program was launched, targeting all the identified organizational weaknesses.

Success in Megaprojects

Rolstadås, Asbjørn, Iris Tommelein, Per Morten Schiefloe and Glenn Ballard. 2014. “Understanding project success through analysis of project management approach”. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business. 7(4): 638–660.

The purpose of this research project was to compare three large construction projects and to show to what extent project success is dependent on the project management approach selected, relative to the challenges posed by the project. Project A concerned the planning, development and installation of a huge offshore gas plant on the Norwegian shelf. In project B, we studied the development phase of a construction project in the US that had chosen a “nontraditional solution” for the project design, whereas project C is the planning and construction of a new airport terminal in the UK. Both cases B and C were launched, requiring radically new thinking around management and execution of the projects. All cases are megaprojects with budgets exceeding one billion USD and were considered successful. Data was collected through interviews, participant observation and document studies.

The pentagon model was used for categorizing and analyzing data in all three cases and proved to be a useful tool to shed light both on differences and similarities. The main findings identified two different approaches in project management: The prescriptive approach focuses on the formal qualities of the project organization, including governing documentation and procedures. The adaptive approach focusses on the process of developing and improving project organization, project culture and team commitment. In cases A and C, the initial project management focus was on formal qualities. However, once the projects were started, informal qualities were developed in the project organization, partly influenced by management, partly developed naturally through close cooperation and physical proximity. In case B, the initial focus was on informal qualities. As the project team had developed necessary trust and committed to a common project culture, the formal qualities were addressed in cooperation among the project team and its contractors. Using the Pentagon model, the adaptive approach means entering the project from the bottom part of the model, focusing on informal qualities, whereas the prescriptive approach means entering from the top by starting the development process with deciding on formal qualities.

Modelling Project Complexity

Rolstadås, Asbjørn and Per Morten Schiefloe. 2017. «Modelling project complexity». International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 10(2): 295–314.

The purpose of this paper is to enhance the understanding of project complexity, what drivers and factors that influence complexity, and how consequences for organizational performance can be assessed. The research is explanatory and based on literature review, model development, interviews and case studies.

Based on an overview of central contributions on project complexity, the paper presents a comprehensive model that covers both the characterization of the complexity and the performance of the project organization, covering both project external and project internal factors. The model is validated through a case study of a large subsea oil and gas development project in Norway. This validation is performed by using a pentagon model of the producing system, identifying both formal and informal qualities, sorted according to the five pentagon dimensions.

Care Challenges during the Pandemic

Orru, Kati, Kristi Nero, Tor-Olav Nævestad, Abriel Schieffelers, Alexandra Olson, Merja Airola, Austėja Kažemekaitytė, Gabriella Lovasz, Giuseppe Scurci, Johanna Ludvigsen and Daniel de Los Rios Pérez, (2021). “Resilience in care organisations: challenges in maintaining support for vulnerable people in Europe during the Covid-19 pandemic”. Disasters. 45 Suppl 1 (48–75) doi:10.1111/disa.12526.

The article studies how the COVID-19 pandemic challenged the resilience of care organizations (and those dependent on them), especially when services are stopped or restricted. The study focuses on the experiences of care organizations that offer services to individuals in highly precarious situations in 10 European countries.

Four central findings were that (1) soup kitchens (food banks) could no longer serve food inside their premises, (2) the most drastic changes occurred in day centers, which were closed to clients in response to government restrictions, (3) night (temporary) shelters stayed open and, in many cases shifted to 24-h service, and (4) residential facilities stopped accepting new clients, but continued working.

The second aim of the study was to identify factors facilitating or impeding the care organizations’ abilities to provide relevant help to their users, that is, their level of resilience. This was done by using the pentagon model for collecting and categorizing data: organizational structures, technologies, infrastructure and equipment, culture, internal relations between clients and staff, leadership, social relations and networks, communication and cooperation, and external framework conditions. All these factors were found to influence how the organizations adapted to high workload and stress, and how they, in general managed to cope with the pandemic. A central finding was that the care organizations with long-term trust networks with clients and intra-organizational cooperation adapted more easily.

Improving Innovation Capabilities

Consultancy Project, Unpublished

A forward-looking, workgroup-based example of analysis can be drawn from a development project in a technological research organization. The background was an experienced need for continuous innovations and professional development, but also a history of several successful earlier innovations. The theme in focus was therefore formulated as innovation capabilities, where innovation was defined as “the ability to develop and/or utilize new knowledge for creating new or improving existing products or processes”.

In group workshops innovation was put “in the middle of the pentagon”, and the groups then systematically went through each of the five pentagon factors. The group-work resulted in the identification of a set of organizational attributes that acted as barriers or drivers for innovation, and which must be observed and addressed. The main factors are listed in the table below:

| Formal structure | – Budgeting routines – Governing documentation – Roles and responsibilities – Operational freedom and economical room for experimentation – Handling the balance between “order and chaos” |

| Technology | – Availability of laboratory and testing facilities – Infrastructure: Do buildings and office spaces invite to frequent and informal contacts within and between different parts of the organization? – ICT: flexibility, communication tools, knowledge management systems |

| Culture | – Openness for new ideas – Overlapping knowledge domains – Internal language, discourses and concepts concerning experimentation and innovation |

| Interaction | – Communication and cooperation patterns – Management support for new ideas |

| Relations | – Accessibility of existing knowledge within the organization – Experienced network brokers – Generalized trust – Possibilities for building alliances – External relations – Avoiding destructive internal conflicts and competition |

Next step in this kind of process will be to contrast the description of the current situation – “as-is”, with a future “should be” and select factors that need to be strengthened or developed. An example can be if one finds that innovation capabilities are hampered due to rigid routines, an infrastructure that makes informal contact difficult, negative attitudes towards experimenting, or distrust between departments or professional groups. Or the analysis can result in the identification of factors contributing positively. Examples are identification of network brokers who act as liaisons between different parts of the organization, a culture where it is allowed to challenge established ways of thinking, or a management that actively pushes employees to engage in experimenting and developing new ideas.

References

Adler, Paul, Charles Heckscher, and Laurence Prusak. 2013. “Building a Collaborative Enterprise.” In HBR on Collaboration, 45–58. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press (First published in Harvard Business Review, July–August 2011).Search in Google Scholar

Adler, Paul S., and Charles Hekscher. 2006. “Towards Collaborative Community.” In The Firm as a Collaborative Community, edited by C. Hekscher, and P. S. Adler, 11–105. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199286034.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

Adler, Ronald B., Lawrence B. Rosenfeld, and Russel F. Proctor. 2001. Interplay. The Process of Interpersonal Communication. Orlando: Hartcourt College Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Ahrne, Göran, and Nils Brunsson. 2011. “Organization Outside Organizations: The Significance of Partial Organization.” Organization 18 (1): 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508410376256.Search in Google Scholar

Bedwell, Wendy L., Jessica L. Wildman, Deborah Diaz Granados, Maritza Salazar, William S. Kramer, and Eduardo Salas. 2012. “Collaboration at Work: An Integrative Multilevel Conceptualization.” Human Resource Management Review 22 (2): 128–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.11.007.Search in Google Scholar

Bolman, Lee G., and Terrence A. Deal. 1984. Modern Approaches to Understanding and Managing Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Bolman, Lee G., and Terrence E. Deal. 2008. Reframing Organizations. Artistry, Choice and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Burke, W. Warner. 2011. Organization Change. Theory and Practice, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Burrel, Gibson, and Gareth Morgan. 1979. Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis. London: Heinemann.Search in Google Scholar

Burt, Ronald S. 2005. Brokerage & Closure. An Introduction to Social Capital. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199249145.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Chmielewska, Malgorzata, Jakub Stokwiszewski, Justyna Markowska, and Tomasz Hermanowski. 2022. “Evaluating Organizational Performance of Public Hospitals Using the McKinsey 7-S Framework.” BMC Health Services Research 22 (7): 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07402-3.Search in Google Scholar

Clegg, Stewart, Martin Kornberger, and Tyrone Pitsis. 2011. Managing & Organizations. An Introduction to Theory and Practice, 3rd ed. London: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Cox, Martin, Stephen Pinfield, and Sophie Rutter. 2018. “Extending McKinsey’s 7S Model to Understand Strategic Alignment in Academic Libraries.” Library Management 40 (5): 313–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/lm-06-2018-0052.Search in Google Scholar

Cross, Rob, and Andrew Parker. 2004. The Hidden Power of Social Networks. Understanding How Work Really Gets Done in Organizations. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cross, Rob., and Robert J. Thomas. 2009. Driving Results Through Social Networks: How Top Organizations Leverage Networks for Performance and Growth. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Cross, Rob, and Guillermo Velasquez. 2010. “Driving Business Results Through Networked Communities of Practice.” In The Organizational Network Fieldbook, edited by Rob Cross, Jean Singer, Sally Collela, Robert J. Thomas, and Yaarit Silverstone, 22–43. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Deal, Terrence A., and Alan Kennedy. 1982. Corporate Cultures. Reading: Addison-Wesley.Search in Google Scholar

Groth, Lars. 1999. Future Organizational Design. The Scope for the IT-based Enterprise. New York: Wiley.Search in Google Scholar

Harrison, Michael L. 1987. Diagnosing Organizations. Methods, Models and Processes. Newbury Park: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Hatch, Mary Jo. 2011. Organizations. A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/actrade/9780199584536.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Hatch, Mary Jo, and Ann L. Cunliffe. 2006. Organization Theory. Modern, Symbolic and Postmodern Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hekscher, Charles, and Paul Adler. 2006. The Firm as a Collaborative Community: Reconstructing Trust in the Knowledge Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

House, Robert J., Paul J. Hanges, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, and Vipin Gupta. 2004. Culture, Leadership and Organizations. The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Igarashi, Tsuku, Yoshihisa Kashima, Emiko S. Kashima, Tomas Farsides, Uichol Kim, Fritz Strack, et al.. 2008. “Culture, Trust and Social Networks.” Asian Journal of Social Psychology 11 (1): 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839x.2007.00246.x.Search in Google Scholar

Itzchakov, Guy, and Harry T. Reis. 2023. “»Listening and Perceived Responsiveness: Unveiling the Significance and Exploring Crucial Research Endeavours.” Current Opinion in Psychology 53: 1–6.10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101662Search in Google Scholar

Jarzabkowski, Paula A., K. Jane, and Martha S. Feldman. 2012. “Toward a Theory of Coordinating: Creating Coordinating Mechanisms in Practice.” Organization Science 23 (4): 907–27. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0693.LêSearch in Google Scholar

Kilduff, Martin, and David Krackhardt. 2008. Interpersonal Networks in Organizations. Cognition, Personality, Dynamics, and Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511753749Search in Google Scholar

Kotter, John P. 2012. Leading Change. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.10.15358/9783800646159Search in Google Scholar

Kühl, Stefan. 2018. Influencing Organizational Culture. A Very Brief Introduction. Princeton: Organizational Dialogue Press.Search in Google Scholar

Latour, Bruno. 1987. Science in Action. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lawrence, Paul R., and Jay W. Lorsch. 1967. “Differentiation and Integration in Complex Organizations.” Administrative Science Quarterly 12 (1): 1–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391211.Search in Google Scholar

Leana, Carrie R., and Harry J. van Buren. 1999. “Organizational Social Capital and Employment Practices.” The Academy of Management Review 24 (3): 538–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/259141.Search in Google Scholar