Abstract

We adopt an ethnographic approach grounded in Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to examine the controversies surrounding student performance in a Brazilian State School recovering from a post-disaster scenario. By tracing the networks of actors – school staff, students, educational regulations, and community concerns – we illustrate how translation processes shape and stabilise organisational actions. The analysis reveals that controversies over project-based versus traditional learning approaches prompted continuous renegotiation of roles, interests, and goals. These renegotiations drew on output-based regulations, prior award-winning educational projects, and local socio-environmental issues to enact a provisional future that the school should achieve. Our findings suggest that contradictory interests in highly regulated public institutions do not necessarily mean a lack of success in achieving collective objectives but instead create opportunities for their creative redefinition. We demonstrate how past experiences and imagined futures influence public managers’ and employees’ decisions in negotiating these controversies, temporarily stabilising organisational practices.

1 Introduction

In 2016, we conducted an ethnographic actor-network study of the Final Grades of Primary Education at a Brazilian State Elementary and High School (State School) in the state of Espírito Santo. We observed controversies that arose regarding regulation, in terms of metrics of student performance, of the organisation and its employees. The State School is one of 497 overseen by the State Secretariat of Education (SSDU). Rather than being bastions of professional autonomy and discretion (Lipsky 2010; Taylor 2007), State School professionals grapple with national curriculum mandates, mandatory school attendance laws, assessment tests, and accountability measures (Bush 2007). Governance is present in schools through regional education departments acting as a governmental and regulatory state (Donadelli and Van der Heijden 2024). Regulations permeate public sector organisations’ reality (Jakobsen and Mortensen 2016). Regulation, as government-imposed rules and penalties, frames the behaviour of these organisations and their members (Ortmann 2010), especially where these intersect with governmental notions of the welfare of society and the public interest (Engwall and Morgan 2002). Regulation is fundamental to organisational governance (Jakobsen and Mortensen 2016). SSDU limits the maximum number of students who can repeat each year to 10 % of the total student population. Significantly, the constitution of this constraint entails agency.

The State School lies near rivers impacted by a major environmental disaster. On November 5, 2015, a tailings dam owned by Samarco Mineração S.A., Vale S.A., and BHP Billiton ruptured, spilling over 43 million cubic meters of mine waste into the Rio Doce (Sweet River). This toxic mudflow travelled 853 km through Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo states, reaching the Atlantic Ocean 17 days later and contaminating the Black River near Vila Regência, just a few blocks from the school. Responding to these local environmental issues, the State School engaged students in project-based education addressing pollution’s impact on the community’s vital resources, the Sweet and Black Rivers (Stengers 2015). The Sweet and Black Rivers became significant actants for the school, with changes in their flow, constituents and effects becoming a focus for school projects. Educational projects are regulated by SSDU. By the second and third trimesters, it became clear that many students were performing below expectations and, as the school struggled to meet the 10 % rule, implementing project-based teaching in State School became a contentious issue. A major reason was the additional responsibilities they created for educational professionals at the State School (Taylor 2007). Despite the school’s longstanding commitment to project-based learning, some staff suggested a shift toward a focus on curricular content, with daily tests and resit exams, as a potentially more effective strategy to meet the 10 % rule. State School used project-based education to convey curriculum content, following SSDU regulations. Project-based education allowed it to address local challenges. It had won awards for these in the recent past as best practices in education, the prize money for which was reinvested in new educational projects. These had further potential to tackle local issues and to win awards. Low academic performance, identified in the second trimester of 2016, ignited controversies that arose in a situation in which the present principal was due to retire at the end of the school year. A new educationalist with a background in religious and private schools joined the school that year. She did not advocate project-based learning; instead, she prioritised curricular teaching and family engagement. Conflicts between the two approaches of delivering the curriculum through projects or formal classes became common.

In employing an ethnographic, actor-network approach, this article investigates the negotiation of controversies surrounding student performance in State School. To do so, we address controversies over workplace relations and conduct by examining as our research question, how professionals in a highly regulated State School navigate its order. From the analysis of controversy, we offer two contributions. First, by exploring regulatory and social controversies in the same terms, we shed light on how highly regulated educational institutions are constituted by intricate organisational dynamics and tensions that negotiate the order presumed to be regulated. Schools, as organisations, are not simply passive objects that state regulation frames. We offer valuable insights into modes of ordering that constitute regulation-in-practice (Latour 2005; Latour and Woolgar 1986; Stengers 2015). We show how a State School with limited resources can navigate organisational controversies and regulations (Bush 2007; Lipsky 2010; Taylor 2007). In doing so, unlikely actants, such as educational regulations and the Sweet and Black Rivers, afforded improbable alliances empowering public sector managers’ organisational preparedness and enhancing their developmental capabilities to generate common goals where previously conflicting interests flourished (Hussenot 2014; Tureta, Americo, and Clegg 2021; Venturini and Munk 2021). Second, we highlight how present conflicts are intertwined with both the past (Tureta, Americo, and Clegg 2021) and the future (Hernes and Schultz 2020; Sharma et al. 2022). Once taken-for-granted practices are questioned, past experiences and imagined futures frame actors’ decisions in negotiating their different interests in resolving controversy (Buchanan and Badham 1999; Hunton and Rose 2011; Latour 2005; Tureta, Americo, and Clegg 2021). We adopt a critical perspective in understanding the regulated legal and social reality of the State School (Callon 1984; Evetts 2002; Latour 2005). We do so by exploring controversies that serve as analytical devices for surfacing occluded issues (Hussenot and Missonier 2010; Law and Mol 2002; Novicevic and Mills 2019; Venturini and Munk 2021). Given that controversies arising from regulation may not be immediately or entirely resolved (Mol 2002), it is relevant to analyse how disputation and differences are managed in situ (Hussenot 2014; Mol 2002; Secord and Corrigan 2017; Stengers 2015). We use the notion of translation (Callon 1984) to understand how disputes are negotiated to modify and stabilise an actor-network (Ferratti, Neto, and Candido 2021; Kolloch and Dellermann 2018) in the public school. Once a controversy is triggered, the translation process enables the actors to learn from disputes and embody new perspectives on a specific problem, facilitating creative solutions for the disagreement at stake (Tureta and Américo 2020). Public managers, in managing organisational change and development (Hussenot 2014; Tureta, Americo, and Clegg 2021), need to know how to steer controversies (Buchanan and Badham 2020).

We draw on actor-network theory as the theoretical and methodological framework underlying the mapping of controversies (Venturini and Munk 2021) to describe the association and disassociation of actors and networks (Callon 1984). Venturini (2010a) states that a cartography of controversies can be depicted using ANT. So, in step with Venturini and Munk (2021), we explore controversies as actor-networks. We operationalise a controversy mapping method through ethnographic observation, interviews, and document collection, which allows us to follow the actions of human and non-human actors, their assembling, detouring, and being (Høyrup and Munk 2007; Latour 2005; Venturini and Munk 2021). The notion of translations (Callon 1984) is used to follow actors and describe the traces left by disputed actions (Latour 2005) as they appear, are modified, or are excluded in negotiating controversies in always-evolving processes of organisations (Hussenot 2014, p. 374).

2 Translating Controversies as Actor-Networks

Beyond the traditional view of translation as a linguistic activity, Callon (1984) highlighted how the intricate dynamics of translation allow meaning, practices, and cultural elements to be negotiated and transformed in social interactions in a specific context. Translation occurs as actors negotiate and define their identities, the potential for interaction, and manoeuvring of boundaries. Translation involves negotiation between actors’ interests, in which interpretations are invariably contested (Callon 1984; Hussenot 2014; Mol 2002; Tureta, Americo, and Clegg 2021). Since Callon’s (1984) groundbreaking study of the sociology of translation, empirical analysis of situated actions involving controversies is evident in numerous accounts (cf. Ferratti, Neto, and Candido 2021; Kolloch and Dellermann 2018; Novicevic and Mills 2019; Tureta, Americo, and Clegg 2021). These investigate translational practices’ precarious (dis)ordering mechanisms, identifying heterogeneous parts mobilised to achieve organisational purposes (Law 1992, 1994; Law and Mol 2002; Mol 2002) and mapping controversies.

Humans and non-humans are entangled and inextricably related ( Feldman and Orlikowski 2011). For instance, Cabantous and Gond (2015) analysed the 1950s emergence of decision analysis, focusing on attempts by some scholars to integrate Bayesian concepts into the management field. Drawing on ANT, the authors showed that artefacts, such as decision trees, facilitated translating Bayesian ideas into business research that helped materialise abstract notions, enabling tools for practical use. Orlikowski and Scott (2015) explored the modern hospitality industry by examining TripAdvisor web postings. These rely on the relationship between humans and non-humans, as “service innovations cannot be realised without processes of materialisation that draw together and thread through tangibility and intangibility, agency and structure, words, things, and deeds” (pp. 209–210). Their research revealed that digital service innovation is deeply embedded with heterogenous sociomaterial practices, including search engines and user-driven reviewing and ranking mechanisms. Translations of practices into ratings raise controversies involving heterogeneous actors (cf. Callon 1984). Translations, constituting networks of actors, map controversies positioning power relations (Ferratti, Neto, and Candido 2021; Kolloch and Dellermann 2018; Tureta and Américo 2020).

2.1 Controversy Mapping

Controversy mapping is a method informed by actor-network theory that allows us to study collective situations through their associations and oppositions (Venturini and Munk 2021). ANT follows three guiding principles aimed at freeing empirical investigation from rigid theoretical constraints (Callon 1984). These principles – agnosticism, generalised symmetry, and free association – discourage privileging any particular viewpoint, as well as distinguishing between human and non-human agency or imposing a pre-existing analytical framework (Venturini and Munk 2021). Instead, ANT requires the observer to consider all actors’ arguments impartially, study scientific and social elements together, and allow the actors to define their categories and relationships. This approach provides a flexible, descriptive toolkit that prioritises empirical observation over theoretical preconceptions, enabling a nuanced understanding of how actors build and interpret their world (Latour 2005).

As a research method, mapping controversies initially focused on disagreements over the interpretation of data, ideas, and worthwhile pursuits in the constitution of scientific knowledge (Venturini and Munk 2021). According to Latour (2005), mapping controversies enables identifying and tracking debates surrounding the constitution of social facts (Hussenot and Missonier 2010; Venturini 2010a, 2010b; Venturini and Munk 2021). Once triggered, controversies translate into diverse, often contradictory, interests (Latour 1987). For example, previously taken-for-granted situations can escalate into snowballing issues – that is, problems or concerns that start narrowly focused but expand as they attract more stakeholders, additional perspectives, and heightened scrutiny (Hussenot 2008; Novicevic and Mills 2019; Venturini 2010a). In Tureta et al.’s (2021) account, what began as a series of late payments between a labour services company and a public university hospital grew into a considerably larger controversy that jeopardised the smooth implementation of their contract. Initially, late payments might have seemed like an isolated administrative lapse; however, as questions emerged about budget oversight, labour rights, and ethical obligations to staff and patients, the issue became more complex and contentious. In this case, the organisation’s primary goal was to re-establish stability and uphold its commitment to patients and families. In organisational settings, such disputes require episodic translations of controversies to maintain temporary stability (Lanzara and Patriotta 2001). However, these stabilisations are more akin to a truce than a lasting peace (Wiedemann, Pina e Cunha, and Clegg 2021) since further disagreements often arise (Mol 2002; Stengers 2015). Hence, controversies between actors should be understood as continuous processes of alternate translations aimed at reconciling contradictory interests (Latour 1999).

2.2 Ordering Observed Controversies with Translation

Actor-network theory concerns itself with how different elements and actors interact and influence each other across time and space, revealing the complexities of social and technical relationships and allowing detailed analysis of controversies and negotiation in organisations (Latour 2005). This analytical approach examines workplace relations and behaviours by exploring interaction practices amongst essential roles played by human and non-human actors enacting various practices (Kolloch and Dellermann 2018; Orlikowski and Scott 2015). Scott and Orlikowski (2014, p. 879) state that “a practice can have no meaning or existence without the specific materiality that produces it”. Through network translation, practices continuously shape and reconfigure order (Latour 1987). Translation is a contingent, localised process that integrates previously distinct interests and activities, mobilising various actants – such as an organisation (Latour 2005) – to act within a network, entangling and coordinating various social and material actants (Latour 1999; Scott and Orlikowski 2014). In this sense, agency, associating humans and non-humans, is a distributed capacity to act (Latour 2005). Instead of seeing actors as self-contained entities, “previously taken-for-granted boundaries are dissolved” (Orlikowski and Scott 2008, p. 455). Relations are foregrounded to show how phenomena are enacted in practice (Scott and Orlikowski 2014).

The integration of previously distinct interests and operations mobilising actors (Latour 1999) can be traced by analysing controversies generated by translation processes (Callon 1984; Latour 2005; Venturini 2010a). For example, using controversy analysis, Mills, Novicevic, and Roberts (2022) show how various interests were translated into management to develop a functionalist paradigm of organisation theory. Tracing an actor-network centred on James March, the authors describe the process of constructing a knowledge field as “the outcome of the shared and conflicted worldviews of multiple actors” (p. 134). While some actors become central, others become peripheral. This complex process implies controversies and conflicts, which usually occlude marginal voices (Mills, Novicevic, and Roberts 2022).

Controversial events and practices serve as objects of translation for actors (Latour 2005; Venturini 2010a; Venturini and Munk 2021; Stengers 2015) and objects of analysis for theorists. Drawing on ANT and a cartography of controversies, Ferratti et al. (2021) analyse the conflicts involved in an information technology startup. The authors reveal various controversies related to labour practices, especially those creating job fulfilment and autonomy imaginaries in startup workplaces. The translation process of different interests “reinforced precarious work practices, promises of future prosperity, ludic ambiences, and the blurring between professional and domestic domains” (p. 2).

Translations are fundamental to understanding and ordering how controversies are initiated and temporarily stabilise as actors translate and negotiate meanings, roles, and actions (Hussenot 2014; Kolloch and Dellermann 2018; Mills, Novicevic, and Roberts 2022). Tureta and Américo (2020) argue that sociomateriality constitutes a space for negotiation where human actors can debate controversies and translate interests. Initial disagreement and subsequent discussion provide potential learning opportunities for actors to embody new knowledge and points of view, allowing creative solutions to stabilise controversial issues (Tureta and Americo 2020). Secord and Corrigan (2017) studied the history of the management practices of colonial privateers, the translations of their interests, and the controversies around transforming pirating practices into lawful activities, supporting British objectives. The authors showed that actors may translate controversial and problematic issues into accepted versions of reality, recorded as legitimate historical accounts.

Controversies reveal the underlying dynamics between heterogeneous elements hidden in the absence of conflict or disagreement. Translation is not just a means of understanding disputes but a way to represent how social orders are constructed and maintained (Latour 2005). By exploring controversies through ethnography and representing them through the notion of translation, we can follow shifts in power relations and alliances, making it possible to see how organisational practices are shaped, questioned, and sometimes redefined. Ultimately, the method highlights that organisational stability is usually provisional, emerging from ongoing negotiations and the temporary alignments of interests that can continually be reconfigured (Venturini 2010a; Venturini and Munk 2021). Thus, translations are crucial because they reveal the complex processes that sustain or challenge organisational realities, allowing researchers to understand the evolution and resolution of controversies (Hussenot 2014).

3 Context and Methods

3.1 Phases

The research was developed in two phases. The first phase involved identifying the role of project-based education and performance management in the State School. SSDU promotes project-based education among the schools comprising its education network. State School uses project-based education to address local issues and differentiate itself from other schools in the education network. It received SSDU awards twice previously for outstanding educational practices for projects in 2012 and 2015. SSDU also manages performance by requiring schools to communicate academic performance through progress and report cards that monitor the 10 % rule. According to regulations, schools face potential interventions by SSDU (cf. Kim, Bansal, and Haugh 2019) if insufficient students graduate.

The second phase of the research involved directly observing actors in relation to the controversies surrounding project-based education, exploring an actor-network based on the representativeness, influences, and interests of the actors’ viewpoints (Hussenot 2014; Venturini 2010a, 2010b; Venturini and Munk 2021). Local perspectives on the consequences of the community’s exposure to environmental catastrophes caused by multinational mining companies were pivotal (Venturini and Munk 2021). The organisational controversies reached their peak with the Tree Day event. Hence, this investigation focuses on controversies before and after this event, analysing how the dispute was temporarily stabilised (Lanzara and Patriotta 2001). The compromise that silenced the controversy (Venturini 2010a; Venturini and Munk 2021; Stengers 2015) and the emergent relations between actors were analysed (Hussenot and Missonier 2010), following methodological steps that will be presented below. Controversies covered diverse aspects, from adherence to SSDU regulations to varying viewpoints on project-based education and its influence on students’ academic performance. We delineate how the actors formed networks around project-based education and were associated or disassociated as controversies emerged and intensified (Callon 1984). We do so by employing translations to represent these controversies by tracing how actors’ interests were negotiated and redefined through alliances, revealing the dynamic shifts in power and relationships that shaped the evolving network of project-based education (Callon 1984; Latour 2005).

3.2 Data Collection

Accessing multiple data sources allows researchers to grasp different actors’ points of view (Venturini 2010b; Venturini and Munk 2021). Data collection occurred through observation, informal interviews, and document curation. Data included discussions of past events, compromise actions, and spatial elements involving the State School and SSDU. Regarding observation, from March to December 2016, the first author conducted 15 hours weekly of immersive fieldwork, chronologically documenting controversies about report card production and project-based education. Observations spanned the school’s areas, documented in two field notebooks, and transcribed into a comprehensive Word document with multimedia materials, interview transcripts, and drawings. Observing the actors’ actions helped us better understand the arguments and various points of view that emerged in controversies. Observation gradually shifted from non-participant to observant participation (Seim 2024).

Access was initially partial. While the principal facilitated research access and sought the School secretary’s cooperation, teacher participation remained voluntary. The research purpose was unclear to them and, in their eyes, was not easily separated from an inspectorial role. Initially, there was some suspicion about the first author’s involvement, but over time, he gained the members’ trust. He did so by helping with exam administration, supervising students when a teacher was absent, supporting teachers with their organisational and personal academic projects, observing the activities of educational projects on site, and joining in end-of-year events. Deeper involvement in educational project development and teachers’ initiatives fostered a receptive atmosphere among initially sceptical research interlocutors (Mol 2002).

Ethnographic questioning (Spradley 1979) guided the informal interviews. These interviews sought to clarify critical issues about controversies and understand the different viewpoints of peripheral and central actors. The diversity of perspectives on the same problem is a central assumption in controversy analysis, allowing researchers to identify silenced voices (Venturini 2010a, 2010b). Therefore, asking probing questions throughout the investigation (Latour 2005), we interviewed several network members involved in controversies, including the principal, nine Final Grade teachers, the coordinator, the educationalist, the caregiver, the school secretary, and the meal team. Each interview averaged 40 min, resulting in over 10 h of transcribed and organised data in Word. Responses were audio recorded and captured in a field notebook.

Past awards for educational projects were integral to State School’s narrative and were woven into its network stabilisation processes. As data documenting past projects, we gathered educational project lists, grant proposals, and reference documents. The school principal, a gatekeeper to archival materials, provided access to communication channels with school entities and regulatory bodies. Crucial documents (e.g., resolutions, decrees, laws, e-mails, past reports, and the school calendar) were carefully integrated into the analysis of network actors’ arguments. For instance, we accessed resolution CEE/ES nº 3.777/2014, which establishes norms for the Education System of the State of Espírito Santo. For instance, the resolution directs the school to perform day-to-day resit exams so that few students fail. For instance, this resolution was used to comprehend how school report cards and educational projects were organised. We also accessed the Black River Invites and The Drop of Water educational projects’ products. We did so to be able to map the professionals, organisations, artefacts, and natures associated with teaching through projects. The action network unfolding through project-based education revealed controversies (Venturini 2010a; Venturini and Munk 2021), which the documents helped analyse because they traced actors’ paths from the past to the present (Tureta, Americo, and Clegg 2021), identifying practices prevailing at the school and the actors’ reasons for implementing them.

3.3 Data Analysis

As data was collected, we digitised and analysed it, treating data collection and analysis as interrelated processes (Corbin and Strauss 1990) to gain insights that could be used to collect new data or clarify some unclear points. In analysing the data, we followed the technique of codification and categorisation (Bryant 2017; Corbin and Strauss 1990; Glaser and Strauss 2006) to trace controversies in the translation process (Callon 1984; Latour 1999).

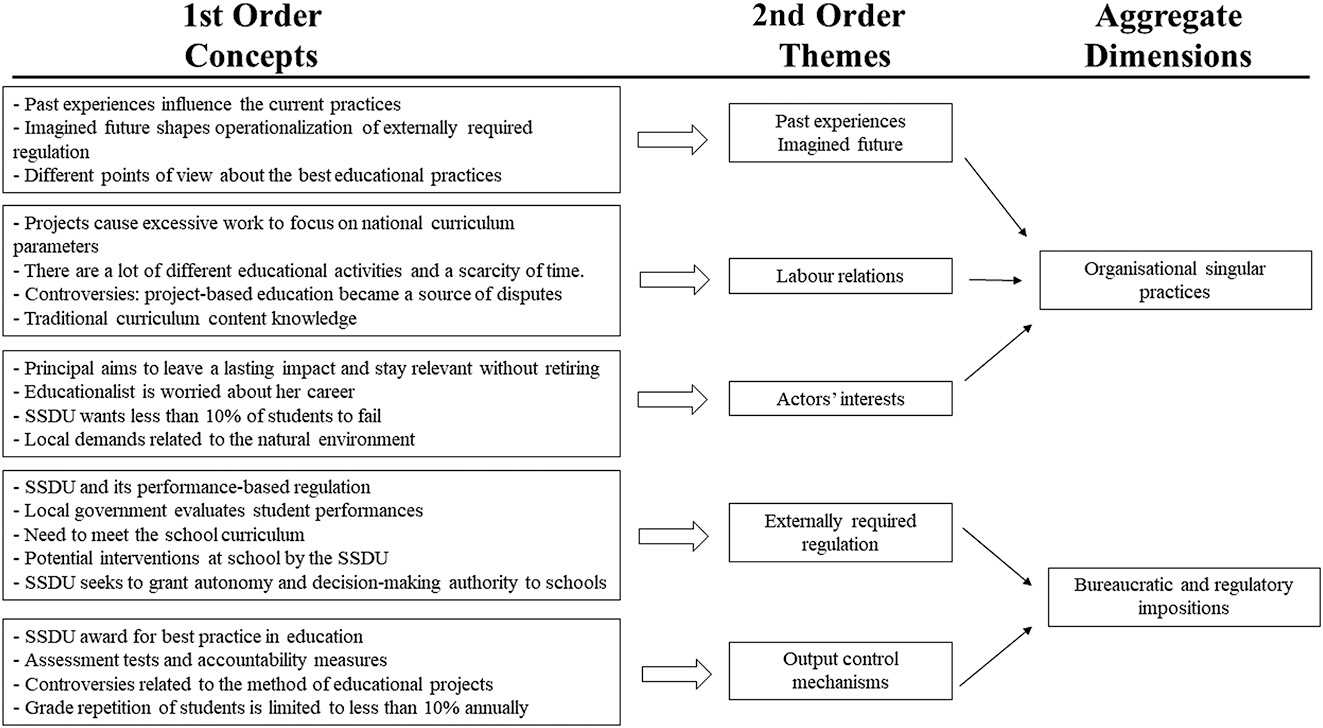

First, we ordered the data chronologically to obtain an overview of the chain of events giving rise to the controversies. In doing so, we could identify the issues that triggered the disputes and conflicts between actors. Next, we explored the network of actors formed around report card production and project-based education over time to understand the underlying principles (and controversies) guiding organisational life (Langley 1999). Various actors were involved, from educators, students, and administrators to rules, regulations, and state organisations. After reading all the material and coding texts and documents about the controversies, we employed constant comparison (Corbin and Strauss 1990) between events, school practices, and actors’ interactions. This analysis allowed us to find similarities and differences in report cards, project-based education controversies, and various regulation and control mechanisms. For instance, we identified the importance of addressing the ‘school singular practice’ of teaching through projects in relationship with ‘past education experiences’ and ‘visions of the future.’ State School constitutes external regulation by SSDU in its practices. Hence, two categories become aligned: organisationally singular practices and bureaucratic and regulatory impositions. These categories synthesise the translation process around controversies.

Subsequently, we established the relationships between these categories and the controversies, their consequences, and how they were negotiated (Bryant 2017). In this phase of the analysis, we observed that professionals ‘negotiate controversies’ by balancing personal and organisational goals (Buchanan and Badham 1999; Hunton and Rose 2011), including personal aspirations, the desire for dignity, as well as the promotion of social issues and support for students (Kuusisto and Rissanen 2023). Following this process allowed us to identify actors negotiating the resolution of controversies through enacting shared goals, even when starting from contradictory objectives. As we made constant comparisons (Corbin and Strauss 1990) between the categories, we identified two moments of translating interests around controversies to achieve a common goal. First, the approaching retirement of the school principal; second, the detailed analysis of data regarding student performance. In these moments, controversies developed, actors negotiated, and disputes were stabilised. The data showed that this translating process enacts the legal and social ‘reality’ in which regulated organisations, such as public schools, act. Legal reality relates to bureaucratic and regulatory impositions from SSDU, while social reality refers to organisational practices performed by actors in their daily school lives. These have to become aligned (see Figure 1).

Data structure. Note. The authors elaborated the figure.

4 Findings

4.1 Controversy Scanning: Leveraging Tools and Strategies for Resolution

In 2016, State School saw Maria, with over a decade of experience in private schools, enter a public school as an educationalist for the first time. Accustomed to an emphasis on delivering curricular content and conducting tests in private schools, she slighted the non-mandatory initiatives that SSDU endorsed. Maria’s priority was to support teachers in advancing curriculum content knowledge and adhering to the schedule. Maria knew she would work at the school for only a year as her employment contract was temporary. She wanted to do a good job and achieve good results that could be useful for her in seeking a new position where she could progress in her career, preferably in her hometown.

Glory, the school principal, actively crafted the State School’s distinctive education approach, emphasising, “Our way, through which we stand out in the State School Education Network, is to offer education through instructive, environmental, cultural projects – ours and the government’s.” After decades of service to the school, Glory risked being made compulsorily redundant by the SSDU because of her age. She wanted good results in that school year to convince everyone that her presence was still necessary and that she could continue to lead the school as a principal.

On September 21, 2016, during Tree Day, around 10:00 a.m., Theresa, the school secretary, was updating a school record when Maria approached, seeking to review the Congo Bantam Band project submitted for the 10th edition of the SSDU award for Best Practices in Education. The SSDU had returned it to the State School for corrections. Maria mentioned, “Glory wants me to see it.” As Maria read the project on Theresa’s computer, Glory entered quietly and unexpectedly raised questions.

Glory: Today is Tree Day. What is the educational action, Maria?

Maria: They will do an educational activity in the afternoon [referring to the Early Grades of Primary Education].

Glory: So, this is it. The small ones reforest, and the big ones destroy!

Maria: That is not it. You know, we identified low academic performance among the students at the end of the first trimester. If the year ended after the first trimester, 25 % of the students would have failed, and we need to stay below 10 % to comply with SSDU regulations. We are in the final moments of the second trimester, and I have opted to prioritise continuing classes. If it is so important, can we do it tomorrow?

Glory: No! Today is the day! An educational activity like this does not happen without the production of interdisciplinary knowledge, whose construction and learning can be assessed by teachers and converted into extra points for students, thus aiding in improving the school’s overall academic performance. If we need to reverse the low performance, I do not see a better way than through educational projects. Talk to your group! [Field notes].

At about 10:30 a.m., without speaking, Maria turned her back on us, heading to the staff room to gather the group. Nevertheless, before she managed to get out, Glory continued:

Here, we teach this way. It is not just about planting the tree. We teach by planting trees with teachers, emphasising the act’s significance in our lives and connecting it to science, history, math, and geography. Educational projects reach fruition through research, schoolwork, corrections, and presentations. Our school and village thrive with activities addressing water quality, Tree Day, the environment, and the river. The embrace of the Black River and the Tree Day, in which we reforested the riparian forest of the Black River, go together! It signifies the State School’s dedication to the local environment, especially since winning the SSDU award for best education practices in 2012 with the Black River Invites project! [Field notes]

Glory, possibly sensing Maria’s frustration, suggested, “Let us talk to the group together.” Around 10:40 a.m., we headed to the staff room to participate in the Final Grades meeting, which detailed the steps for conducting the Tree Day activities. The school staff discussed how to improve the pass rate and address and organise differences about how to do so within the school’s practices. Following a group meeting, it was decided to reschedule planning Tree Day activities for the next day.

Despite the scheduled Tree Day activities, nothing happened on September 22, 2016. Theresa worked in the Liedi due to the secretariat’s lack of Internet access. Around 09:30 a.m., Maria arrived to open her email, in which Theresa had forwarded an email from SSDU to Maria containing a spreadsheet, The Espírito Santo Basic Education Assessment Program (PAEBES), that needed to be filled with the names of inspectors for the Final Grades. Maria suggested Marieta (mathematics) and Mike (geography) as inspectors. Maria appeared visibly troubled with the numerous tasks on her plate.

We left the laboratory with Maria, who headed to the staff room. The first named researcher encountered Polly, who was preparing for the Tree Day action:

Yesterday, Maria called me asking if I could be here today to organise the action. I discussed it with her a month ago, and she ignored me! Glory must have reprimanded her, am I right? After many months of working here, she still does not know the school! [Field notes]

The Tree Day event commenced on September 26, 2016. Maria entered the secretariat the following day, September 27, expressing dissatisfaction with the school’s priorities: “I have never seen a school with so many meetings and projects. After the Tree Day, we still have the Black Consciousness Day and the Science Fair. There are too many actions and little time to close the year.” Subsequently, Glory entered the secretariat, where Theresa reviewed employees’ contracts. Maria informed Glory about the previous day’s Tree Day activities and outlined plans for the upcoming grades. In response, Glory said:

Yesterday, students with special needs went on an outing in Linhares. Unfortunately, our school did not participate. Despite receiving an invitation forwarded by Theresa, no teachers attended. The decision to abstain was solely yours.

Glory stated that the State School’s interests and unique qualities were being set aside for the newcomer educationalist’s beliefs, as she phrased it, “who arrived yesterday” [field notes]. The following day, September 28, 2016, around 8:00 a.m., Polly coordinated further Tree Day activities at the school. Around 10:00 a.m., just after the break, Maria summoned us to the 9th-grade class, joined by Glory, Polly, and Morena. Maria informed the students about an educational activity with Polly, the biology teacher, celebrating Tree Day on September 21. The focus was on identifying potential natural seedlings, primarily those of Ipe trees. Polly clarified the objectives: (1) identify Ipe tree seedlings, (2) learn proper removal techniques, and (3) plant and water the seedlings. After the briefing, the small 9th-grade class engaged in the activity. Polly, who had initially identified one seedbed, pointed out additional options, suggesting students could replant them in various locations for better development, such as at home or in the riparian forest. After walking a few blocks through Vila Regência, we reached a spacious area with numerous mature Ipe trees. Polly pointed out the “natural seeding” beneath these trees, and once we were all gathered, the class commenced.

After uprooting, the students planted the seedlings around Vila Regência – in the riparian forest along the Black River and Sweet River, at their homes, along the streets, and within the State School. They utilised spades, fertiliser, and water buckets. Following the seedling removal and planting activity with the 9th-grade students, Polly repeated the process with the 8th-grade students, who were with Julieta. Julieta is a science teacher recently hired at the State School after passing a public exam. As the last action of the day, everyone returned to the State School. However, it was still necessary for future award submissions to document and structure a pedagogical report embracing the Black River and to post it on Facebook.

A few weeks later, on October 13, 2016, at 08:00, Maria was in the secretariat talking to Julieta. She complained about the overload of tasks that teachers must carry out and began to question the taken-for-granted school practice of teaching through educational projects:

It is too much for me because we are at the end of the second trimester. We must pass the knowledge content, prepare tests, and close the year, and we still have Black Consciousness Day and the Science Fair! [Field notes].

Not everyone in the school liked the idea of providing education through educational and environmental projects – Maria certainly did not. Julieta agreed: “It is complicated going through all the formal educational activities imposed by SSDU plus developing projects, activities, and actions” [Field notes]. Although a common practice, project-based education became a source of disputes. A few new employees, led by the educationalist, disagreed with the majority, questioning what was traditionally accepted and influencing the school’s management during the 2016 school year. These lively disputes led to escalating problems. The educationalist and the science teacher were interested in reversing the students’ negative performance by leaving project-based education aside. Their argument was consistently reiterated: to enhance students’ performance, preserve the school’s autonomy, and prioritise public discretion for school professionals, the primary focus should be on teaching curricular content knowledge and revising for exam tests. They were confident that aligning around this goal would benefit all parties involved. The others addressed their teaching goals through social issues.

SSDU offers various engagement strategies and instruments, such as training sessions, pedagogical interventions, and norms that allow constant resit exams to be applied. While the SSDU promotes project-based education, it also maintains strict regulations through output control mechanisms (e.g., parameters, resolutions, and incentives), granting schools autonomy and decision-making authority but emphasising results. The aim is to reduce the number of students retained or held back, aligning with SSDU’s performance-based objectives. Different points of view emerged. The educationalist and the science teacher could not independently achieve their desires for a more formal organisation of activities focused on national curriculum parameters. Meanwhile, the principal, eager to leave a lasting impact and remain relevant within the school, saw an opportunity to improve student performance, particularly by leveraging the local environmental context, such as the Sweet River and Black River, which had been severely affected by the 2015 environmental disaster, to cement her legacy of project-based education. These rivers, along with the Tree Day event, played a significant role in shaping the school’s project-based approach, intertwining local ecological concerns with educational goals.

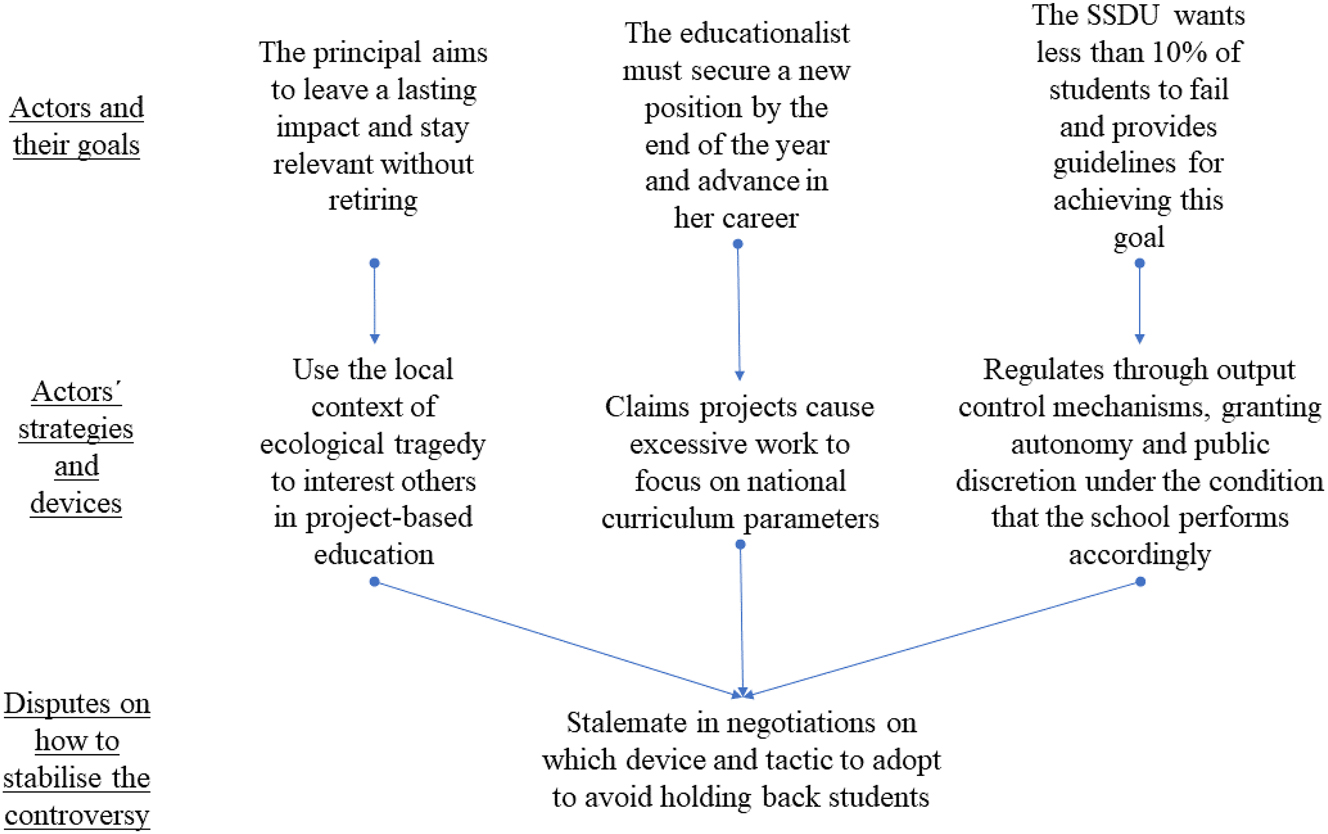

By the final stretch of the second trimester of the 2016 school year, the question of which alternative to follow to turn student performance around was still unclear. Teachers were uncertain whether to prioritise curricular activities according to the school calendar and conduct daily resit exams or to emphasise educational projects and interdisciplinary approaches to education, which connected the students’ learning to local ecological issues, to improve academic performance that way. Both options were highlighted in national curriculum parameters and SSDU resolutions as viable paths to follow. However, the lack of agreement on which strategy to adopt – whether project-based education tied to the local context or a traditional curriculum approach – led to a stalemate in negotiations. This lack of focus was detrimental to everyone involved. The controversy underscored the different associations between activities, tools, events, and actants, on which an alliance to improve student academic performance had not yet formed (see Figure 2).

Associations around controversies defining actants’ identities and interests. Note. The authors elaborated the figure based on Callon (1984).

The school principal and the educationalist differed in their understanding of their roles, objectives, motivations, and interests, which led each to reject the other’s approach. The principal aimed to leave a legacy by advocating project-based education using the environmental context. At the same time, the educationalist sought a more traditional approach, arguing that projects caused excessive work and diverted focus from national curriculum goals. Despite these differences, both actors recognised that full autonomy in defining their roles and strategies was unattainable.

4.2 Coordinating and Mobilising Actors Around the Stabilisation of Controversies

Despite the SSDU’s clear framework and strategic arguments, the State School struggled to implement its goals. Competing perspectives on whether to focus on project-based teaching or traditional curriculum content knowledge created a fragmented response to the 10 per cent standard. The SSDU’s emphasis on school-level autonomy and discretion did not guarantee success; rather, the State School had to designate concrete tools and strategies – be they project-based, traditional, or both – to coordinate teachers, the educationalist, and the director around a shared approach. Clearly assigned roles, founded on a provisional agreement to use both project-based activities and more conventional study guidelines, helped align the actors’ efforts.

Nevertheless, the process of coordinating and engaging these actors was fraught with negotiations, demonstrations of authority, and tactical manoeuvres. Student participation, already challenging, became more complicated when teachers and school administrators pursued multiple, uncoordinated strategies. Attempts to improve student performance splintered across various isolated activities, undermining cohesive progress. On October 14, 2016, a series of simulated PAEBES tests exemplified these efforts. Maria, the educationalist, also introduced a standardised format for “study guidelines for the final resit exam,” aiming to raise grades and document improvement steps for the SSDU. While initially appearing as yet another isolated initiative, this format was designed to protect teachers and administrators from potential criticism if students did not meet the 10 % regulation.

Two pivotal events then propelled the school toward a more unified approach. First, on October 17, the impending retirement of the school principal, Glory, was confirmed. The announcement of public recruitment for her replacement signalled impending leadership change, making it urgent for the school to coalesce around a clear plan. Second, on October 19, Maria and Glory conducted a more detailed analysis of student performance data, discovering that approximately 25 % of Final Grade students were still struggling. This moment prompted a shift in perception: there was limited time left in the semester, but enough to intervene effectively if the school focused its efforts.

In this context, what had seemed like extraneous activities – such as the Science Fair and Black Consciousness Day – suddenly emerged as opportunities. Maria recognized that these events could serve as vehicles for engaging students, boosting attendance, and integrating the “study guidelines for the final resit exam” within more interactive, project-based experiences. By blending project-based components with traditional study guidelines and reinforcement classes, teachers, the educationalist, the principal, and other staff rallied around raising student performance. Although lingering doubts remained about whether project-based teaching alone could achieve the necessary improvement, the competing arguments temporarily converged on one definitive statement: student performance would improve, and the SSDU standard would be met. This newly shared commitment stabilised the controversy for now, even if it did not resolve all underlying tensions or uncertainties.

The principal’s pending retirement and the analysis of student performance data were turning points in the dynamics of the controversies. Glory was interested in leaving a positive legacy regarding school management. Maria now had a more concrete view of the problem of student performance and realised that the clock was ticking. Therefore, she could better understand what would be necessary to do her job well and progress in her career. Achieving the school’s objective of meeting the standard was valuable for both. An alliance between the actors emerged as a strategic path to address a combination of objectives, including regulatory requirements, local concerns, and personal ambitions. In doing so, the actors simultaneously addressed regulatory, local, and personal challenges. Meeting SSDU demands and providing evidence of methods that could improve student performance on standardised tests was critical to avoid future interventions. Additionally, adhering to project-based education allowed the incorporation of local issues, such as environmental and family-related concerns, as well as afforded Glory the possibility of a lasting legacy. Maria also sought professional advancement and stable employment after her contract ended. Avoiding future interventions from SSDU because of the students’ poor performance was critical for all actors.

What the director and the educationalist assumed as the best way to overcome the students’ poor academic performance became accepted by everyone. By agreeing, these two professionals came to represent all other teachers. They spoke on behalf of the school’s strategy to comply with SSDU regulations, reverse students’ poor performance, and address local issues. The question “How many students will fail in the 2016 school year?” concerns negotiations on how these regulations should be met by the school professionals. Their discussion about numbers stemmed from negotiations surrounding the tools and strategies offered by SSDU to ensure compliance with its regulations (e.g., norms, decrees, parameters, and incentives) and with the perspectives of school professionals regarding the number of students who can progress successfully to the next academic year. Counting the potential students with good academic performance at the end of the 2016 school year serves as a measure of what State School professionals can use in their negotiations with SSDU and its bureaucrats about their efforts to avoid failures, aiming to safeguard the State School’s autonomy and the discretion of its employees. The number of students who pass is crucial to convince SSDU bureaucrats of the validity and effectiveness of the choices made by the State School in terms of tools and strategies used to fail fewer students.

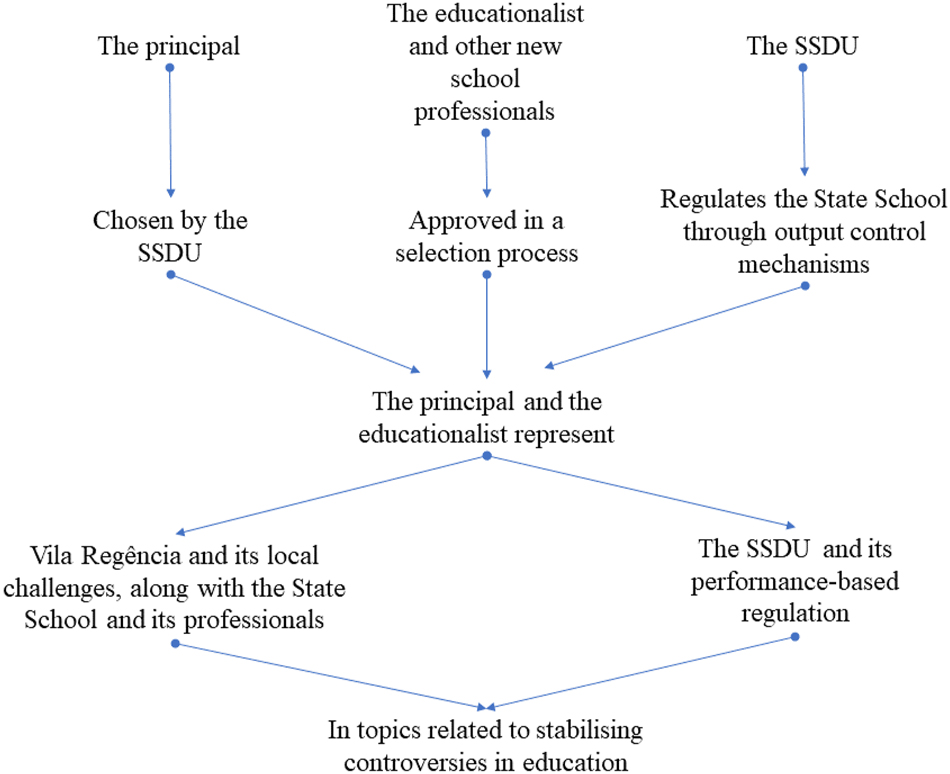

A balance was achieved between the controversies of the legal world of SSDU regulation and the social world of the State School professionals. Nevertheless, the realities of SSDU regulations, the school curriculum, the social realities of teachers and students, the local context, Tree Day, the Sweet River, the Black River, and environmental disasters did not construct or determine the practices used in the school. Such enactments aligned with both social and legal ‘reality’. Project-based education, as ‘organisationally singular practices’, was legitimately enacted, just as it was silenced by other regarding addressing local problems as extra work, actors that found affordance in SSDU’s ‘bureaucratic and regulatory impositions’ as tools and strategies (see Figure 3).

The construction of actors through the mediation of representatives. Note. The authors elaborated the figure based on Callon (1984).

Once the director and the educationalist reached a consensus, the controversy around improving students’ performance stabilised, and teachers and other employees in the school had little room to disagree or act differently. Different actants were marshalled. One actant that played a key role was the broader environmental catastrophe, with the Science Fair addressing the problem of access to water in the area due to the environmental tragedy caused by the mining companies. Other State School professionals relied on SSDU regulations as actants in developing new formats for helping students improve their performance and protect the State School in case of insufficient student grade improvement. The assembly of actors and actants was essential in synchronising contributions, persuading the educationalist to embrace project-based learning, and influencing SSDU in refraining from intervention. In practice, identities were redefined, enabling decisions and educational practices to take shape accordingly. Since the start of the controversy, there has been complex coordination among human and non-human actors to stabilise the controversy by negotiating tools and strategies with which to address identified problems.

5 Discussion

5.1 Negotiating Controversies

As we have shown, the disagreement at school around the educational strategy was a dynamic process, for it changed as actors discussed their different points of view. The educationalist and the principal initially sought to impose their beliefs during the school year. After numerous discussions and negotiations, they decided to focus on educational projects and the school curriculum as tools that would enable them to execute their joint strategy to reverse students’ poor performance. In doing so, they could address local and professional issues and SSDU regulatory output-based control problems. An uncertain and debatable social and legal ‘reality’ emerged from the controversy (Callon 1984). Subsequently, both actors became concerned with generating justification to convince the SSDU that everything possible had been done to avoid failing many students as they grappled with the demands of organisational professionalism (Evetts 2011; Rolandsson 2022) as well as bureaucratic controls and hierarchical frameworks (Evetts 2009; Freidson 2001). Over the trimesters, considering the limited public resources available for the SSDU to be present in its 497 schools, those working there became concerned with understanding whether their tools and strategies for organising public education were followed on a case-by-case basis. They would analyse what had not worked to improve their practices for the next school year. Beyond assessing how its tools and strategies were deployed, SSDU also chose a new principal for State School.

In this translation process, actors primarily altered identities and interests in relation to available tools and strategies, allowing the State School to manage the 2016 school year failure rate from the SSDU point of view. Conflicting narratives about the past (Janssen 2013; Maclean et al. 2014; Mena, Rintamäki, and Fleming 2016; Smith et al. 2022) were used to present divergent social and legal descriptions of future scenarios (Callon 1998, p. 11; Maclean et al. 2023). The principal’s assertion of project-based education as the State School’s historic way of teaching, setting this school apart from others in the education network, was opposed by the educationalist’s perspective that project-based education was increasingly overwhelming professional energies. These differing interpretations were utilised to propose distinct strategies and tools to enhance future student performance. At the same time, the former advocated a focus on educational projects, and the latter prioritised the core curriculum and school calendar. They altered and updated historical narratives to make sense of situations (Maclean et al. 2014). Organisational forgetting of past achievements, such as awards for best practices in education, occurred. Concerns by employees about overload were silenced, erasing questionable incidents from the historical narrative (Janssen 2013; Mena, Rintamäki, and Fleming 2016). Negotiation comprehending and managing controversies was framed with a view to the future (Blagoev, Felten, and Kahn 2018; Maclean et al. 2023; Stengers 2015).

Facts, such as output-based regulation applied to education and project-based learning, as well as values, such as addressing local contexts simultaneously with education practices, were entangled (Callon 1998; Latour 2005; Scott and Orlikowski 2014). Different versions of past educational experiences and envisioned futures clashed and influenced the State School’s execution of SSDU’s externally mandated regulations in the 2016 school year. At State School, negotiating solutions to emerging problems by integrating ‘organisationally singular practices’ with ‘bureaucratic and regulatory impositions’ established a specific way of organising to fit the temporary needs of its actors. Accomplishments in project-based education, including SSDU guidelines for organising and outlooks regarding professionals’ workload and the critical local context, were entwined within ongoing stakeholder debates.

5.2 From Controversies to Enacting Shared Goals by Assembling Actants, Coordinating Contributions, Changing Trajectories, and Redefining Identities

Exploring the controversies enacted on the occasion of Tree Day as actor-networks (Venturini and Munk 2021), the landscape of the 2016 academic year was shaped by the assembly of heterogeneous actors, including education professionals, regulatory frameworks, past educational practices, and visions of the school’s future in the context of Sweet River’s environmentally fragile ecosystem. The assembly included the rivers, animals, and local inhabitants who depend on the ecosystem for survival. The entanglement of the social and material was evident in the organisational life of the school as these heterogeneous actors were constitutively entangled and inextricably related (Feldman and Orlikowski 2011; Scott and Orlikowski 2014). Drawing on ANT and analysing controversies as actor networks, we approached the school context and actors’ actions from a relational, productive perspective. Instead of considering education professionals, regulations, calendar, and rivers as self-contained separate entities, we dissolved their boundaries to bring their entanglement to life and to show how actors enact controversies in practice (Orlikowski 2010; Orlikowski and Scott 2008; Scott and Orlikowski 2014). The academic year was enacted by coordinating and aligning these actants and navigating controversies while identities and interests shifted over time (Venturini and Munk 2021). Consequently, the agency of ‘organisationally singular practices’ and ‘bureaucratic and regulatory impositions’ became possible, with their effects materialising by aligning individual and organisational goals.

Finishing the year with report cards that met the standard was especially crucial for both Maria and Glory. Glory, facing pressure to retire, could at least leave a legacy involving the practice of designing and implementing educational projects that not only facilitated teaching and learning processes but also engaged with local environmental and social challenges, as well as the curriculum. Thereby, she would be embedding her legacy within the school’s broader actor-network. Maria, who would need to find another school to work in by the end of the year, saw in the students’ good performance and successful educational projects an opportunity to attest to her professional credibility. The SSDU needed to adhere to the National Education Guidelines and Framework Law. Among other topics, this addresses the requirement for all students who do not reach the minimum passing grade to undergo resit exam tests. In light of the legal understanding that improving academic performance is optional for students, the SSDU requested explanations from the State School regarding the observed lack of success. The translation process around the controversy was a learning opportunity in the school. It allowed the actors to take on each other’s perspective, facilitating the enactment of a shared goal in which both Maria and Glory could understand each other’s concerns, work together in the same direction, and try to meet the SSDU objectives.

To meet the output goals, State School employees aligned their aspirations with SSDU’s organisational objectives (Kuusisto and Rissanen 2023). Glory redirected Maria´s actions, while the educationalist changed her trajectory. Doing this enabled them to integrate project-based education and curricular content knowledge to enhance students’ academic performance by the end of the third trimester. This way, both local norms and SSDU guidelines for organising could be satisfied. SSDU did not just have power over State Schools; SSDU also facilitated opportunities for positive power using different pedagogic disciplines (Clegg 2023; Cunha et al. 2021). SSDU’s output-based regulation extended beyond merely achieving goals; SSDU’s regulations alone could not determine a school’s employee structure, tools, or actions. The idea that a seemingly coherent set of regulations could exert unified control over diverse entities, such as a network of public schools, is implausible (Evetts 2002, 2011; Mol 2002). Instead, dynamic flows and flat organisational ontology enabled actors to form alliances for which regulatory frameworks become affordances (Callon 1984; Clegg 2023). Rather than being a form of control, the regulatory environment proved to be a generative device producing consent (Cameron 2024). The case exhibits the enactment of complex relationships amongst overlapping agencies, objects, and organisations engaged in everyday politics (Mol 2002).

At the end of the second trimester, the principal and the educationalist aligned in advocacy of project-based learning as a necessary means for redefining the situation (Klemsdal and Clegg 2022; Callon 1984). Poor student performance led to an embrace of the potential impact of project-based education on long-term environmental recovery efforts for the school’s short-term goals (Kim, Bansal, and Haugh 2019). Engaging in negotiations, school professionals anticipated prospective scenarios yet to unfold (Sharma et al. 2022); for example, when the educationalist produced guidelines for the final resit exam, aiming to safeguard school employees and the State School from potential future SSDU questioning regarding educational methods. State School discussions intertwined various elements, including work overload, local environmental recovery, and legal considerations, the results of which redefined their identities and interests within SSDU’s output-based regulations. Interests and identities emerged from these discussions differently (Law 1994). School representatives, SSDU’s regulations and bureaucracy, teachers’ efforts, local ecosystem rehabilitation, and student performance were all in flux. After the taken-for-granted educational project practices were questioned and actors surfaced their concerns, individual and organisational ‘goals’ were aligned with legal and social ‘reality’.

In summary, translating different interests and establishing a clear direction helped the actors find common ground in performing their tasks. In the end, Maria and Glory could facilitate revisions and simulated exams to enhance students’ performance in upcoming assessments and plan and implement educational projects. Negotiations via emails, meetings, and various material practices gradually rendered project-based learning an “obligatory passage point” (Clegg 2023; Latour 2005; Novicevic and Mills 2019). The reality, operability, and stability of project-based learning at the close of 2016 should be viewed as the provisional outcome of these ongoing translation processes (Latour and Woolgar 1986).

Nevertheless, controversies are rarely linear (Michaud 2014), translation can lead to betrayal (Callon 1984), and regulation itself can be challenged (Mol 2002; Stengers 2015). The 2016 school year did not hinge on a single, unified regulation of educational provision (Hussenot 2014; Hussenot and Missonier 2010) but rather on translation processes that fostered only temporary consensus and alliances (Callon 1984; Lanzara and Patriotta 2001). Past educational experiences – central to organisational storytelling (Boje 2017) – and evolving visions of State School’s future (Augustine et al. 2019; Blagoev, Felten, and Kahn 2018; Hernes and Schultz 2020; Zundel, Holt, and Popp 2016) shaped the present. By evaluating poor student performance, considering the SSDU’s actions, acknowledging new leadership, and tying these concerns to the recovery of the Black and Sweet Rivers, the school collectively embraced controversies as an “engine for knowledge creation and organizational change” (Lanzara and Patriotta 2001, p. 966).

6 Conclusions

This article investigated the negotiation of controversies as actor-networks surrounding student performance in a Brazilian State School. We studied how actors in a highly regulated context, one punctuated by problematic events, translated their interests when controversies arose, and they started to question taken-for-granted practices. Using controversy analyses and actor-network theory, we followed the actors as they accomplished their tasks and dealt with regulations relating to student performance. The findings showed that past experiences lodged in organisational storytelling and imagined futures defining professional aspirations influenced public managers’ and employees’ decisions in negotiating controversies.

The contribution of this article is twofold. First, the study reveals how actors within highly regulated organisations, such as State Schools with limited resources, can leverage the affordances of regulation to reconcile controversial challenges and constraints. Regulations do not simply control and discipline but can generate creative, positive power responses. Controversies are a space for negotiation, enabling actors to make the best use of available resources and explore alternative solutions under challenging contexts, rather than necessarily being a distraction from organizational objectives. Second, the process of exploring these controversies demonstrates how present disputes are deeply interconnected with both past experiences and future aspirations. The dynamics of past events influence current decisions, while visions of the future shape how actors engage with present challenges. In this context, macro-level policies of regulation manifest in diverse ways depending on local situations, creating varying impacts across different settings.

While ANT and controversy mapping provided a strong foundation for understanding the actants and dynamics within the case, the originality of this research lies in how we interpreted and applied these frameworks to reveal new organisational insights. By focusing on the negotiations that took place in the school, we observed that the heterogeneous actors – teachers, administrators, students, SSDU, and the environment – were not simply controlled by regulations but actively shaped them through their everyday interactions and improvisations. The key finding from this research is how such actors used the controversy around environmental crises and educational standards to create temporary solutions that stabilised the situation in ways driven by local actors’ ingenuity rather than overarching policies. Doing this, they produced practices that signalled productive consent, rather than submission, to regulations. Their improvisational ability highlights the importance of understanding controversies not just as moments of conflict but as opportunities for creative problem-solving, in which actors redefine their roles and responsibilities in response to emerging challenges. Moreover, this study shows that controversies are central to how public organisations, such as schools, relate to external pressures, utilising the diverse capacities of their members to manage complex regulatory environments that are more than a disciplinary apparatus. This approach underscores how organisational realities are constructed through negotiations involving singularly local practices as well as bureaucratic and regulatory impositions, offering fresh perspectives on how we understand management in resource-constrained and highly regulated environments. Agency resides at the heart of regulation.

Knowledgeable actors combined with local resources to achieve desired policy ends. That these goals were achieved is a result of the improvisational bricolage of actor and actant networks in the local situation. A mining disaster 600 km away changed the Sweet River irrevocably; it transformed the life of the village at the river’s mouth, with unsettling results on student attendance and performance in the local State School, an outpost of state regulation. Local actors used the situation and its controversial effects to translate their way out of a crisis that could have led to extraordinary measures. The school provided a flat ontological site in which social, natural, and legal realities were constructed locally, in a frame provided by regulations, punctuated by events, and interpreted through differing definitions of the situation by professionals aspiring to do the best for their reputations and their students.

References

Augustine, G., S. Soderstrom, D. Milner, and K. Weber. 2019. “Constructing a Distant Future: Imaginaries in Geoengineering.” Academy of Management Journal 62 (6): 1930–60. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.0059.Search in Google Scholar

Blagoev, B., S. Felten, and R. Kahn. 2018. “The Career of a Catalogue: Organizational Memory, Materiality and the Dual Nature of the Past at the British Museum (1970–Today).” Organization Studies 39 (12): 1757–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618789189.Search in Google Scholar

Boje, D. M. 2017. “The Storytelling Organization: A Study of Story Performance in an Office-Supply Firm.” In The Aesthetic Turn in Management, edited by S. Minahan. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.10.4324/9781351147965-10Search in Google Scholar

Bryant, A. 2017. Grounded Theory and Grounded Theorizing: Pragmatism in Research Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199922604.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Buchanan, D., and R. Badham. 1999. “Politics and Organizational Change: The Lived Experience.” Human Relations 52 (5): 609–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679905200503.Search in Google Scholar

Buchanan, D., and R. Badham. 2020. Power, Politics, and Organizational Change: Winning the Turf Game. Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Bush, T. 2007. “Autonomy and Accountability in Higher Education.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 35 (4): 443–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143207081057.Search in Google Scholar

Cabantous, L., and J. P. Gond. 2015. “The Resistible Rise of Bayesian Thinking in Management: Historical Lessons from Decision Analysis.” Journal of Management 41 (2): 441–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314558092.Search in Google Scholar

Callon, M. 1984. “Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St Brieuc Bay.” The Sociological Review 32 (1): 196–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954x.1984.tb00113.x.Search in Google Scholar

Callon, M. 1998. “An Essay on Framing and Overflowing: Economic Externalities Revisited by Sociology.” The Sociological Review 46 (1): 244–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954x.1998.tb03477.x.Search in Google Scholar

Cameron, L. D. 2024. “The Making of the “Good Bad” Job: How Algorithmic Management Manufactures Consent Through Constant and Confined Choices.” Administrative Science Quarterly 69 (2): 458–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/00018392241236163.Search in Google Scholar

Clegg, S. R. 2023. Frameworks of Power, 2nd ed. London: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 1990. “Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria.” Qualitative Sociology 13 (1): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00988593.Search in Google Scholar

Cunha, M. P., S. R. Clegg, A. Rego, and M. Berti. 2021. Paradoxes of Power and Leadership. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.10.4324/9781351056663Search in Google Scholar

Donadelli, F., and J. Van der Heijden. 2024. “The Regulatory State in Developing Countries: Redistribution and Regulatory Failure in Brazil.” Regulation & Governance 18 (2): 348–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12459.Search in Google Scholar

Engwall, L., and G. Morgan, eds. 2002. Regulation and Organisations: International Perspectives. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.10.4324/9780203064733Search in Google Scholar

Evetts, J. 2002. “New Directions in State and International Professional Occupations: Discretionary Decision-Making and Acquired Regulation.” Work, Employment and Society 16 (2): 341–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/095001702400426875.Search in Google Scholar

Evetts, J. 2009. “The Management of Professionalism. A Contemporary Paradox.” In Changing Teacher Professionalism. International Trends, Challenges and Ways Forward, edited by Sharon Gewirtz, Mahony Pat, Hextall Ian, and Cribb Alan. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Evetts, J. 2011. “A New Professionalism? Challenges and Opportunities.” Current Sociology 59 (4): 406–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392111402585.Search in Google Scholar

Feldman, M. S., and W. J. Orlikowski. 2011. “Theorizing Practice and Practicing Theory.” Organization Science 22 (5): 1240–53. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0612.Search in Google Scholar

Ferratti, G. M., S. M. Neto, and S. E. A. Candido. 2021. “Controversies in an Information Technology Startup: A Critical Actor-Network Analysis of the Entrepreneurial Process.” Technology in Society 66: 1–13.10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101623Search in Google Scholar

Freidson, E. 2001. Professionalism: The Third Logic. Cambridge, UK: Polity.Search in Google Scholar

Glaser, B. G., and A. Strauss. 2006. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategy for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine.Search in Google Scholar

Hernes, T., and M. Schultz. 2020. “Translating the Distant into the Present: How Actors Address Distant Past and Future Events Through Situated Activity.” Organization Theory 1 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631787719900999.Search in Google Scholar

Høyrup, J. F., and A. K. Munk. 2007. “Translating Terroir: Sociomaterial Potentials in Ethnography and Wine-Growing.” Ethnologia Scandinavica 37: 5–20.Search in Google Scholar

Hunton, J. E., and J. M. Rose. 2011. “Retracted: Effects of Anonymous Whistle-Blowing and Perceived Reputation Threats on Investigations of Whistle-Blowing Allegations by Audit Committee Members.” Journal of Management Studies 48 (1): 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00934.x.Search in Google Scholar

Hussenot, A. 2008. “Between Structuration and Translation: An Approach of ICT Appropriation.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 21 (3): 335–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810810874813.Search in Google Scholar

Hussenot, A. 2014. “Analyzing Organization through Disagreements the Concept of Managerial Controversy.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 27 (3): 373–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/jocm-01-2012-0006.Search in Google Scholar

Hussenot, A., and S. Missonier. 2010. “A Deeper Understanding of Evolution of the Role of the Object in Organizational Process: The Concept of “Mediation Object”.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 23 (3): 269–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811011049608.Search in Google Scholar

Jakobsen, M. L., and P. B. Mortensen. 2016. “Rules and the Doctrine of Performance Management.” Public Administration Review 76 (2): 302–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12409.Search in Google Scholar

Janssen, C. I. 2013. “Corporate Historical Responsibility (CHR): Addressing a Corporate Past of Forced Labor at Volkswagen.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 41: 64–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2012.731698.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, A., P. Bansal, and H. Haugh. 2019. “No Time like the Present: How a Present Time Perspective Can Foster Sustainable Development.” Academy of Management Journal 62: 607–34. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.1295.Search in Google Scholar

Klemsdal, L., and S. R. Clegg. 2022. “Defining the Work Situation in Organization Theory. Bringing Goffman Back In.” Culture and Organization 28 (6): 471–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2022.2090563.Search in Google Scholar

Kolloch, M., and D. Dellermann. 2018. “Digital Innovation in the Energy Industry: The Impact of Controversies on the Evolution of Innovation Ecosystems.” Technological Forecasting & Social Change 138: 254–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.033.Search in Google Scholar

Kuusisto, E., and I. Rissanen. 2023. “Kohti päämäärätietoista yhteiskunnallista opettajuutta? Opettajaopiskelijoiden tulevalle työlleen asettamat päämäärät.” Kasvatus 54 (4): 385–98. https://doi.org/10.33348/kvt.138074.Search in Google Scholar

Langley, A. 1999. “Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data.” Academy of Management Review 24: 691–710. https://doi.org/10.2307/259349.Search in Google Scholar

Lanzara, G. F., and G. Patriotta. 2001. “Technology and the Courtroom: An Inquiry into Knowledge Making in Organization.” Journal of Management Studies 38 (7): 943–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00267.Search in Google Scholar

Latour, B. 1987. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Tthrough Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Latour, B. 1999. “On Recalling ANT.” In Actor-Network Theory and After, edited by J. Law, and J. Hassard, 15–25. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1111/j.1467-954X.1999.tb03480.xSearch in Google Scholar

Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199256044.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Latour, B., and S. Woolgar. 1986. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400820412Search in Google Scholar

Law, J. 1992. “Notes on the Theory of the Actor-Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity.” Systems Practice 5 (4): 379–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01059830.Search in Google Scholar

Law, J. 1994. Organizing Modernity. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Law, J., and A. Mol. 2002. Complexities: Social Studies of Knowledge Practices. Durham: Duke University Press.10.1215/9780822383550Search in Google Scholar

Lipsky, M. 2010. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. Russell Sage Foundation.Search in Google Scholar

Maclean, M., C. Harvey, J. A. A. Sillince, and B. D. Golant. 2014. “Living Up to the Past? Ideological Sensemaking in Organizational Transition.” Organization 21: 543–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508414527247.Search in Google Scholar

Maclean, M., C. Harvey, R. Suddaby, and D. M. Coraiola. 2023. “Multi-Temporality and the Ghostly: How Communing with Times Past Informs Organizational Futures.” Journal of Management Studies 61: 3401–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.13022.Search in Google Scholar

Mena, S., J. Rintamäki, and P. Fleming. 2016. “On the Forgetting of Corporate Responsibility.” Academy of Management Review 41: 720–38.10.5465/amr.2014.0208Search in Google Scholar

Michaud, V. 2014. “Mediating the Paradoxes of Organizational Governance through Numbers.” Organization Studies 35 (1): 75–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613495335.Search in Google Scholar

Mills, A. J., M. M. Novicevic, and F. Roberts. 2022. “Anti-History of the Functionalist Paradigm in Organization Theory: Using the Lens of March and Simon’s Organizations.” Journal of Management History 28 (1): 134–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmh-03-2021-0021.Search in Google Scholar

Mol, A. 2002. The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. Durham: Duke University Press.10.1215/9780822384151Search in Google Scholar

Novicevic, M. M., and A. J. Mills. 2019. “Controversy as a Non-corporeal Actant in the Community of Management Historians.” In Connecting Values to Action: Non-corporeal Actants and Choice, edited by C. M. Hartt, 129–43. London: Emerald Publishing.10.1108/978-1-78973-307-520191010Search in Google Scholar

Orlikowski, W. J. 2010. “The Sociomateriality of Organisational Life: Considering Technology in Management Research.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34 (1): 125–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep058.Search in Google Scholar

Orlikowski, W. J., and S. V. Scott. 2008. “Sociomateriality: Challenging the Separation of Technology, Work and Organization.” The Academy of Management Annals 2 (1): 433–74. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520802211644.Search in Google Scholar

Orlikowski, W. J., and S. Scott. 2015. “Exploring Material-Discursive Practices.” Journal of Management Studies 52 (5): 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12114.Search in Google Scholar

Ortmann, G. 2010. “On Drifting Rules and Standards.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 26 (2): 204–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2010.02.004.Search in Google Scholar