Abstract

There is a growing interest in deepening our understanding of variations in professionals’ boundary work. How healthcare professionals work to change or maintain power and practice domains is embedded in their efforts to collaborate across organizational and professional boundaries. Drawing on a comparative interview study from the Danish eldercare sector, we explore how nurses and care workers in two different organizational contexts articulate their boundary work strategies. Our findings illustrate ways in which organizational context may influence boundary work. In one organizational context, nurses and care workers worked from separate functional units and had limited opportunities for interactions to collaborate and build trust across professional boundaries. This was linked to competitive boundary work strategies. In the other organizational context, nurses and care workers worked together in integrated units, providing opportunities to build trustful relationships and familiarity with each other. This was linked to collaborative boundary work strategies. Furthermore, we found that boundary work was not only influenced by the organizational context but also influenced the organizational context in return. The nurses in the functional units defended and created new boundaries that hindered engagement in collaborative-oriented strategies. Our study contributes by demonstrating how elements of the organizational context can influence boundary work through relational aspects, while boundary work, in turn, can influence the organizational context. This suggests an interplay between organizational context and boundary work that resembles a reciprocal relationship, potentially differing from previous assumptions in the boundary work literature. This interplay may help us better understand variations in professionals’ boundary work.

1 Introduction

Increasing specialization and fragmentation of healthcare services have created complex care pathways that simultaneously demand – and challenge – interprofessional collaboration across organizational and professional boundaries (Axelsson and Axelsson 2006; Beijer et al. 2018; Gudnadottir, Bjornsdottir, and Jonsdottir 2019; Meier 2024). To support interprofessional collaboration among healthcare professionals striving to deliver holistic and coherent services, there has been an upsurge in organizational initiatives aimed at structuring how professionals work and collaborate in patient pathways (Hald et al. 2024b). Interprofessional collaboration involves boundary work (Weber et al. 2022), particularly when professionals navigate roles, responsibilities, and workflows within newly established or changed organizational contexts (Comeau-Vallée and Langley 2020; Duner 2013; Liberati, Gorli, and Scaratti 2016; MacNaughton, Chreim, and Bourgeault 2013).

The concept of boundary work has been widely used to study the strategies enacted by healthcare professionals in response to such initiatives in various organizational contexts (Dahle 2003; Eliassen and Moholt 2023; Farchi, Dopson, and Ferlie 2023; Järvinen and Kessing 2021; Langley et al. 2019; Meier 2015). The term boundary work refers to the efforts professionals undertake to demarcate, change, or maintain the boundaries between groups, professions and organizations (Gieryn 1983; Langley et al. 2019). Two modes have been conceptualized: Competitive boundary work where boundaries function as barriers that promote separation, and collaborative boundary work where boundaries work as junctures to enable collaboration (Langley et al. 2019; Quick and Feldman 2014). The literature includes a growing number of empirical studies of professionals’ micro-strategies (Comeau-Vallée and Langley 2020; Lindberg, Raviola, and Walter 2017; Liberati 2017), and we therefore have a great deal of knowledge about the various strategies professionals draw on. However, we know less about why certain strategies for boundary work are adopted while others are not.

For the last decade, scholars have therefore called for studies that address variations in boundary work based on different elements of the organizational context articulated as constraints (Weber et al. 2022), context factors (Liberati 2017) or conditions and contingencies (Langley et al. 2019). For example, Liberati (2017) applied a comparative framework that allowed her to identify how different context factors influenced the construction of the “medical-nursing” boundary across three hospital wards. She found that the patient’s state of awareness, the type of clinical approach adopted by doctors and nurses, and the level of acuity on the ward are connected to different types of boundary work. Weber et al. (2022) studied interprofessional collaboration across general practice and nurses in nursing homes as boundary work in response to contextual constraints stemming from legislation and time pressure. The authors found that these constraints impacted whether the professional groups limited or opened up their boundary. The literature thus points to a possible interplay between boundary work and organizational context.

To contribute to this area, this study investigates the articulation of boundary work strategies in two different organizational contexts. We focus on differences in how the organizational boundaries are drawn in either separating or integrating professional groups organizationally. To do this, we adopt an approach to context that underscores how phenomena such as ‘organizational boundaries’ are continually constructed (e.g., through boundary work) in relation to the context people understand and enact them in (Meier and Dopson 2019). Our study is set in the Danish eldercare sector and designed as a comparative interview study. This sector serves as an excellent setting for examining how healthcare professionals’ boundary work is linked to different organizational contexts. First, nurses and care workers must work together within the same municipal administrative organization to provide care to elderly citizens in their homes. Second, they do so within two highly different settings. They either have to work together across organizational boundaries that functionally separate healthcare units of nurses from home care units of care workers, or they work together within integrated units that bring the two professional groups together organizationally. We compare how these two professional groups discursively construct their boundary work strategies within each of these two organizational contexts by asking the following research question: How do healthcare professionals articulate boundary work in two different organizational contexts?

We found that nurses and care workers articulated both competitive boundary work and collaborative boundary work. Competitive boundary work dominated the articulations of nurses and care workers in functionally organized health care and home care units, whereas collaborative boundary work dominated the articulations of care workers and nurses in integrated units. Moreover, we found that elements of the two organizational contexts were important for relational aspects of boundary work. Strategies of demarcation and defending boundaries in the functional units were connected to limited interaction across professional groups, while such interactions were articulated as necessary for working together and building trustful relationships. The integrated units, however, were characterized by close proximity and interactions, which were believed to foster trust between nurses and care workers. This, in turn, enabled them to draw on collaborative-oriented strategies of negotiation and downplaying boundaries. Interestingly, we also found evidence that boundary work strategies influenced the elements of organizational contexts mentioned above. This was particularly salient in some of the nurses’ efforts to defend and construct new boundaries to demarcate their work from that of care workers. Taken together, our findings suggest an important interplay between boundary work and organizational context.

The paper is organized as follows. First, we discuss existing literature on boundary work and present our theoretical framework. Then, we describe the research design, the empirical setting of the study, and the methods we have used. Following this, we present the analyses of boundary work articulations in each of the two organizational contexts. We then compare findings across cases, discussing how our findings of an interplay between boundary work and organizational context add to the literature. We end the paper by suggesting future avenues for boundary work research.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Boundaries and Boundary Work

The concept of boundary work was originally coined by Gieryn (1983) to illustrate the demarcation of science from non-science. It can be studied by examining how professionals socially construct professional or disciplinary boundaries individually and collectively through discursive, cognitive, material, and embodied practices (Langley et al. 2019). A great deal of boundary work literature employs the notion of professional boundaries to understand professions, professional identities and projects, and how these professional interests influence interprofessional collaboration (Bucher et al. 2016; Bos-de Vos, Lieftink, and Lauche 2019; Järvinen and Kessing 2021; van Bochove et al. 2018). Making, negotiating, or maintaining boundaries can be significant for a professional’s claim of a practice domain. Embedded in the sociology of professions (Abbott 1988), the notion of boundary work typically refers to fights for jurisdictions among professional groups who strive to demarcate exclusive rights to specialized knowledge and jurisdictional control (Liu 2018; Feyereisen and Goodrick 2019). The ongoing construction and negotiation of boundaries marks who belongs to a professional group and who does not. Negotiating boundaries can thus be used to stress the differences between “us” and “them” in interprofessional collaborations as an exclusion mechanism or to use references to difference as occasion for including members of other disciplines or professions into collaboration (Meier 2015). Hence, interprofessional collaboration implicitly involves boundary work, which in turn has consequences for establishing and reproducing professions and professional projects (Bucher et al. 2016; Fournier 2000; Järvinen and Kessing 2021).

Boundary work has therefore often been applied to study professionals’ responses to organizational change or new interprofessional collaboration initiatives (Lindberg, Raviola, and Walter 2017; Weber et al. 2022). For example, Liberati, Gorli, and Scaratti (2016) found that interprofessional collaboration in a hospital setting remained challenging even after reorganizing from functional units to multidisciplinary teams. The professionals sought to maintain their occupational identity, making it challenging to bridge professional boundaries. Consequently, disputes over boundaries stood in the way of improving integrated care. And Eliassen and Moholt (2023) studied boundary work between therapists and home trainers in reablement teams within a municipal home care set-up. They found that reablement teams were either hierarchical (drawing on demarcation strategies) or symbiotic (drawing on collaborative strategies).

Although professionals often collaborate towards achieving a common goal for their citizens, they also have their own distinctive professional goals and are thus in competition with each other (Wackerhausen 2009) which influence their boundary work (Comeau-Vallée and Langley 2020). Bucher et al. (2016) studied how field-level professionals responded to a proposal for interprofessional collaboration that would potentially change their jurisdictional boundaries and professional practices. The study found that the professionals used different discursive boundary work strategies that reflected the status of their professions. The higher-status professions engaged in “generic naturalistic framing” in that they emphasized maintaining the status quo and did not question current boundaries, presenting other professions as being less important. Professions with lower status engaged in “targeted evidence-based framing” of other professions to explicitly renegotiate boundaries to deconstruct the generic naturalistic framing of the higher-status professions based on evidential and experiential resources.

In another study, Bos-de Vos, Lieftink, and Lauche (2019) showed how architects in inter-organizational settings responded to threats of marginalization and increasingly unstable role structures by engaging in different types of boundary work: reinstating, bending, and pioneering role boundaries. These strategies enabled the professionals to reconcile project demands with their professional values and beliefs (Bos-de Vos, Lieftink, and Lauche 2019). Building on this work, Taminiau and Heusinkveld (2020) explored how professional groups with different statuses in accounting firms responded to institutional pressures. They found that the higher-status professionals (accountants) applied competitive boundary work strategies, which in turn spurred competitive strategies from the lower-status professionals (tax advisors).

An important insight from this line of research is the theorization of a relationship between social position and boundary work at the meso and micro level of organizations and how this relationship impacts boundary negotiations. Higher-status professionals tend to make efforts to naturalize clear boundaries, while lower-status groups tend to blur boundaries to advance their position (Comeau-Vallée and Langley 2020; Langley et al. 2019). The body of literature on boundary work shows that despite the intention to dismantle organizational and hierarchical boundaries to deliver holistic and coordinated care, existing power dynamics and status struggles may be reproduced in interprofessional settings (Finn 2008; Järvinen and Kessing 2021; Liberati, Gorli, and Scaratti 2016; Nugus et al. 2010; Wackerhausen 2009). Accordingly, the ongoing negotiation of boundaries means reorganizing for more coherent care does not necessarily imply the integration of work across disciplines (Liberati, Gorli, and Scaratti 2016).

2.1.1 Collaborative and Competitive Boundary Work

The literature has thus far conceptualized two overall modes of boundary work: collaborative forms, where boundaries work as junctures that enable connection, and competitive forms, where boundaries function as barriers that promote separation (Comeau-Vallée and Langley 2020; Nugus et al. 2010; Quick and Feldman 2014). In this study, we use this conceptualization as a theoretical framework for operationalizing the notion of boundary work, which is a rather broad concept that refers to social, symbolic, discursive, physical and embodied practices.

We draw on a seminal review by Langley et al. (2019) to develop our theoretical framework further (see Appendix for Table A1, illustrating our theoretical framework). In their review, the authors identify various micro-strategies within the modes of collaborative and competitive boundary work. They relate the competitive mode to the original work of Gieryn (1983) and Abbott (1988) “which conceived boundaries as mechanisms that clarify differences and establish divisions” (Langley et al. 2019: 22). Competitive boundary work is performed when professionals defend, contest, or create boundaries that confer legitimacy, power, and privilege on themselves. In these instances, boundary relations are often constructed as a dichotomy that assigns superior legitimacy and power to the favored side while excluding the other (Langley et al. 2019). Collaborative boundary work is when professionals accommodate or overcome boundaries to collaborate (Langley et al. 2019). Professionals negotiate, embody or downplay boundaries to develop and sustain patterns of collaboration and coordination in settings where groups cannot achieve collective goals on their own. In the boundary work literature, collaborative boundary work is thus expected to support interprofessional collaboration whereas competitive boundary work is viewed as a hindrance for collaboration to efficiently be enacted.

2.2 Boundary Work and Organizational Context

Recently, boundary- work research has emphasized the importance of understanding the different contexts and conditions surrounding the professionals being studied (Langley et al. 2019; Liberati 2017; Lindberg, Raviola, and Walter 2017; Weber et al. 2022). Professionals’ boundary work is increasingly understood as shaped not only by elements found at the professional level (e.g., identities) but also by elements found at the organizational level (e.g., contextual constraints). Considering different ways of organizing, Stjerne and Svejenova (2016) investigated permanent and temporary organizational structures in a Danish film production company. These authors drew on boundary work to reveal how tensions were resolved at different levels to shape a complex and dynamic connection between temporary and permanent organizational structures. In their study, Lindberg, Walter, and Raviola (2017) emphasized changes in the organizational context for boundary work following the introduction of new practices in a hybrid operating room in a hospital. Specifically, they found that new technologies and material artifacts conditioned the performance of boundary work. However, to our knowledge, only a few empirical studies have focused explicitly on how the context within which boundaries, groups, tasks or collaboration unfold matters for professionals’ boundary work. When the literature does include context as relevant, this is primarily articulated as a relatively stable, rather general and often disembedded background to the professionals’ everyday boundary work.

Increasingly, however, researchers recognize that context is much more dynamic and interlinked with phenomena than previously theorized (Meier and Dopson 2021; Murdoch et al. 2023) and this may also apply to the relationship between boundary work and organizational context. Carmel (2006), for example, found that the efforts of doctors and nurses to obscure their professional boundaries ended up reinforcing the organizational boundaries. Boundaries are “an intrinsic element of organizing”, as Stjerne and Svejenova (2016: 1773) state and we should not assume a simple, one-directional relationship. Considering ‘context’, Meier’s (2015) study of collaboration in hospital wards found that a range of conditions related to the nature and organization of healthcare work, e.g., the degree of urgency, input uncertainty, and severity of the patient’s illness, influenced the professionals’ boundary work. Similar results were described by Liberati (2017) in a study of how context influences the regulation of the medical-nursing boundary in three hospital wards. This author found three types of context factors: patients’ state of awareness, the type of clinical approach adopted by nurses and doctors, and the level of acuity on the ward.

Such knowledge of the interplay between context and boundary work is important because it nuances our understanding of how and why professionals draw boundaries in certain ways and with which effects. These studies highlight an important, and so far, underexplored point in the literature on boundary work: a link can be made between organizational context and professionals’ boundary work and as Liberati (2017) argues, the current literature fails to sufficiently examine and theorize the “negotiation context” in which professionals draw boundaries.

3 Methods

This paper draws on a qualitative comparative case study (Eisenhardt 2021) set in the Danish eldercare sector, where nurses and care workers provide care for elder and vulnerable citizens in their homes. The data for this study was produced in 2021 and the research aimed to understand the advantages and disadvantages of different ways of drawing organizational boundaries in the sector – specifically, in functional units of health care and home care versus integrated home and health care units. The terms of ‘functional’ and ‘integrated’ units are drawn from terminology used in existing literature (e.g. Liberati, Gorli and Scaratti 2016).

3.1 Research Context

In Denmark, municipal authorities provide care-needing older adults with publicly funded home care and home healthcare. The Danish Social Services Act regulates home care (personal care and domestic help), while the Danish Health Act regulates home healthcare. The eldercare workforce consists of nurses (approx. 14 %), social and healthcare assistants (approx. 32 %), social and healthcare helpers (approx. 37 %), and unskilled labor (approx. 10 %) (Vinge and Topholm 2021).

Based on educational level, clinical decision making and autonomy over work, nurses are the higher-status group with a minimum education at the Bachelor level, corresponding to level 6 on the international EQF scale (Kjellberg et al. 2022). In Danish eldercare, nurses perform healthcare tasks that cannot be delegated to care workers with lower competence levels and are responsible for managing complex care pathways, such as those of terminally ill citizens. Non-complex tasks such as stable wound care, simple medicine dosages, injections, medicine administration, and compression socks are typically delegated to care workers (Vinge and Topholm 2021). Care workers, which include social and healthcare assistants and social and healthcare helpers, also provide personal care and domestic help, such as bathing, dressing, and nutrition, for which the needs are assessed and allocated by administrative personnel (typically with a background in nursing, physiotherapy, or occupational therapy). Social and healthcare assistants have a vocational education corresponding to level 4 on the international EQF scale, while social and healthcare helpers are trained at level 3 on the same scale (Kjellberg et al. 2022). For the analysis, we were interested in the boundary between health care and home care and therefore grouped social and health care assistants and helpers under the term ‘care workers’. These care workers form the lower-status group based on lower education levels, clinical competence, and reduced autonomy over work compared to nurses.

The need for interprofessional collaboration (i.e., working together) between nurses and care workers is substantial in this sector (Hald et al. 2024a). For example, if a citizen receives both complex wound care from a nurse and help with bathing and dressing from care workers, the nurse and care workers must coordinate when each carries out their tasks and keep each other informed about the citizen’s health progress regarding the wound. Another example is when a nurse has been performing complex care tasks that have stabilized, e.g. medication dosages, in which case the nurse would delegate the task to the care workers and supervise the care pathway, necessitating continual communication. This makes interprofessional collaboration between nurses and care workers, regardless of its form, an ongoing process of coordination, communication, and delegation (Hald et al. 2024b).

This ongoing process is structured through formal documentation systems (electronic patient records), where professionals can record observations, agreements, and tasks for one another, and can be supplemened with weekly or bi-weekly in-person meetings to facilitate coordination, communication, and discuss potential challenges or difficult tasks. Moreover, interprofessional collaboration can also occur informally, with professionals coordinating and communicating via text, phone calls, or casual conversations when they meet at the office or at the citizen’s home (Hald et al. 2024a). However, it is important to note that while this interprofessional collaboration is greatly needed and the municipalities have different ways of organizing for it, it does not always occur as expected. Despite the formal systems and expectations for interprofessional collaboration, the findings illustrate that it is not always enacted in practice, meaning professionals do not always collaborate across boundaries as intended.

In the case of functional units, nurses are organized in healthcare units with nursing managers, and care workers are organized in home care units with home care managers. These units are usually not co-located, with professionals working from different offices and sometimes not even sharing the same citizen base. This means that the functional units are viewed as separate entities with interprofessional collaboration occurring across the organizational boundaries between the two types of units. In contrast, in the integrated units, nurses and care workers report to the same manager, work from the same location and office space, and share the same citizens. These integrated units are typically organized in smaller interprofessional ‘groups’ or ‘teams’ and the interprofessional collaboration thus happens within the unit.

Consequently, although the expectations towards interprofessional collaboration are the same in both cases, the organizational context differs significantly. In this study, we explore possible connections between these different organizational contexts and the boundary work strategies of nurses and care workers.

3.2 Case Selection

To examine how and why different organizational contexts are connected to different forms of boundary work, we chose two cases for comparison: A case of boundary work articulations in functionally organized units (three research sites) and a case of boundary work articulations within integrated units (two research sites). The two cases of boundary work articulations were chosen to vary on how the organizational boundaries are drawn, serving as polar cases (Eisenhardt 2021). We were able to recruit five municipalities as research sites to participate in the study. Three municipalities were recruited serving as cases of functionally organized units, and two municipalities were recruited as cases of organizing in integrated units. The participating municipalities differed in size and geographical location because they were only sampled on this aspect of the organizational context. However, they were otherwise similar in terms of how the nurses and care workers were expected to work together in the care pathways.

3.3 Data Collection Through Interviews

We conducted in-depth semistructured group interviews with members of each professional group. This method produced knowledge on how the professionals articulated their own and the other group’s collaborative efforts and their experiences of how their practices were related to the organizational context they worked within. The purpose of interviewing each professional group individually was to gain insight into their experience and perceptions of working together across professional groups and to ensure openness among each group (see e.g. Bach, Kessler, and Heron 2012).

Access to interview participants was obtained through the local managers in each municipality. In total, 12 nurses and 19 care workers participated in the study. Table 1 presents an overview of the number of participants within the two professional groups from each municipality. Data consisted of a total of 15 qualitative group interviews conducted by the first author in October and November 2021. Interviews were held in the municipalities or online if requested by the municipalities due to the risk of COVID-19. Each group interview lasted between 90 and 120 minutes.

Overview of participants.

| Nurses | Care workers | |

|---|---|---|

| Case: functional units | ||

| Municipality 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Municipality 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Municipality 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Case: integrated units | ||

| Municipality 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Municipality 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 12 | 19 |

The interviews were structured around a thematic interview guide which was tailored to each of the three professional groups but centered around the following themes: 1) perceived advantages and disadvantages of the organizational context, 2) the professional role and task domains of each professional group, 3) task allocation practices, and 4) ways of collaborating across professional and/or organizational boundaries. The interview participants discussed the functioning of working together, coordination and communiation, how it was organized for in their local context, and how this impacted their professional interests. The interviews gained insights into each professional group’s articulated practices and experiences of whether and how they worked together across professional boundaries, and thus, into how they articulated boundary work efforts.

3.4 Data Analysis

The interviews were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed. As a first step, we wrote up brief case narratives (Miles and Huberman 1994) to understand the local organizational context of the professionals and how interprofessional collaboration was organized for, e.g. mutual meetings, phone contact or informal interactions. The coding progressed in three steps drawing on an abductive analysis strategy (Thompson 2022). The aim was first to characterize how the two professional groups discursively constructed boundary work strategies and to compare these articulations across the two cases to investigate whether and how there was a relation between boundary work and organizational context. For this, the transscribed inteview data was pooled into each case to allow for within-case analysis of boundary work articulations in functional units and integrated units respectively. In this second reading of the material, data were coded following the theoretical concepts of collaborative and competitive boundary work, as shown in Table A1 in the appendix. These overall concepts guided an initial open coding. We then analyzed the coded paragraphs to identify specific micro-strategies concerning the two professional groups. We also coded instances where these strategies were connected to the organizational context. In this step, we were guided by the micro-strategies already identified in the literature while remaining open to additional or contrasting findings. For example, we interpreted it as competitive boundary work when nurses talked about how much they valued being organized in their own unit and what this meant for their professionalism (“defending”). Or, when care workers, rather than resisting or trying to create new boundaries, made excuses for why nurses often did not attend mutual case conferences, we interpreted this as collaborative boundary work (“accommodation”). The majority of the most salient micro-strategies we identified corresponded with the literature (e.g., “differentiation”), while a few appeared to us to suggest new formulations (e.g., “withdrawal”). The outcome of the analysis is illustrated in Table A2 in the appendix.

Then, we conducted a cross-case analysis by 1) juxtaposing the articulated boundary-work strategies of each professional group in the two cases and 2) juxtaposing the strategies connected to nurses and care workers, respectively, between cases. We did this to examine the differences and similarities in articulated strategies across the two organizational contexts to draw out the important elements for boundary work. Additionally, we wanted to examine the differences and similarities in boundary work across the two professional groups to draw out their relations to hierarchical status. We saw that care workers drew on similar types of boundary work in the two cases. In contrast, the articulations of the nurses’ boundary work varied with each case. Our case analyses are illustrated in Table 2.

Findings on the interplay between elements of the organizational context and boundary work.

| Case | Elements of the organizational context | Relational aspects | Articulated boundary-work strategies for nurses | Articulated boundary-work strategies for care workers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional units | Separated units of nurses and units of care workers working from different locations, with each their managers, and often also client bases Formal interactions through case conferences Phone contact is limited due to phone hours in the nursing units |

Trust is viewed as a prerequisite for collaboration, but it is difficult to build due to limited face-to-face dialogue. Hierarchical relations dominate the interactions | Defending professional and organizational boundaries (competitive) Creating organizational boundaries (competitive) Blurring (collaborative) |

Differentiation (collaborative) Withdrawal (competitive) Accommodation (collaborative) |

| Integrated units | Integrated units with co-location, mutual management, and mutual client base Everyday interactions (both formal and informal) |

Trust is built through daily interactions and enables collaborative boundary work | Differentiation (collaborative) Negotiation (collaborative) Downplaying (collaborative) Demarcation (competitive) |

Differentiation (collaborative) Negotiation (collaborative) |

4 Findings

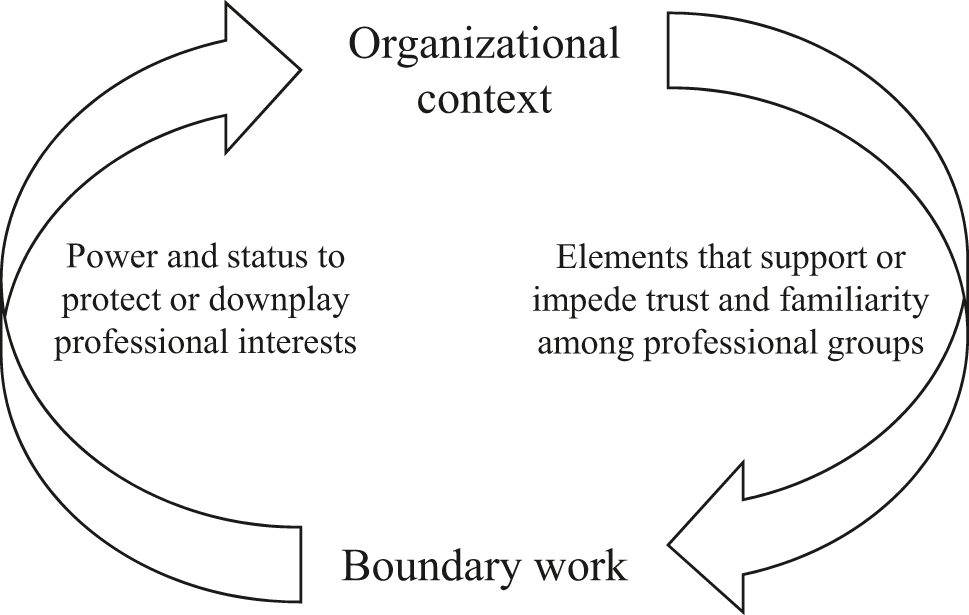

Our findings reveal that the most salient boundary work articulations among the professional groups varied with the organizational context. In the organizational context of separate functional units, nurses and care workers had limited opportunities for interactions and for building trust across organizational and professional boundaries. This was linked to articulations of competitive-oriented boundary work strategies through acts of ‘withdrawal’, ‘defending’ and ‘creating’ boundaries. In contrast, the context of integrated units provided opportunities to build trustful relationships and familiarity among nurses and care workers. These elements of the organizational context were linked to collaborative-oriented boundary work strategies of ‘differentiation’, ‘negotiation’, and ‘downplaying’ boundaries. Moreover, our findings show that boundary work was not only shaped by the organizational context but also shaped the organizational context in return. Particularly the nurses in the functional units engaged in efforts to defend professional boundaries by creating new organizational boundaries that impeded engagement in relational aspects to support collaborative boundary work. This interplay between boundary work and organizational context is illustrated in Figure 1.

An interplay of boundary work and organizational context.

4.1 A Competitive Boundary Work Mode in the Functional Units

4.1.1 Organizational Boundaries as a Barrier for Relational Aspects

The professionals working from functionally organized units viewed their professional differences in practice domains, knowledge, and clinical competence as a basis for collaboration. Especially the care workers emphasized the necessity of discussing care pathways with the nurses as the nurses were responsible for making decisions, reacting to their observations of changes in the citizens’ illness, and delegating healthcare tasks. Knowing and trusting the nurses in the healthcare units was an enabler for contacting and sharing their observations with them. However, the care workers found it challenging to establish trustful relationships with the nurses as the two groups were organizationally and physically separated. Consequently, there were few opportunities for face-to-face interactions. Both nurses and care workers associated the challenges of building trustful relationships with the organizational context, as exemplified here:

It would be better if they [the nurses] met here because there is actually only very formal dialogue. We benefit a lot from each other, but the way we are organized makes it difficult. Task performance would be better if we had better access to the nurses. (Care worker)

Besides written communication in the care systems, case conferences appeared as a central forum for formal interprofessional interactions. Despite the importance of case conferences, nurses found it difficult to prioritize these meetings amongst acute tasks and busy schedules. When they canceled, sent a substitute nurse, or participated in an unengaged manner, the care workers perceived this as a lack of acknowledgment of their work and the citizens, and it emphasized feelings of hierarchical rather than collaborative relations with the nurses.

4.1.2 Defending Professional Boundaries through Organizational Boundaries

The nurses in the nursing unit made efforts to defend the existing professional boundaries between nursing and care work. They emphasized the need for a community of nurses “because we need that dialogue with our colleagues”. They also defended the organizational boundaries demarcating healthcare from home care as they preferred to “maintain the separated organization but build more bridges” to improve interprofessional collaboration. Defending the organizational boundaries entailed that the nurses could “protect” their time and resources for their tasks and citizens rather than “servicing home care”. This is exemplified in this nurse’s fear of post-its with tasks she needs to respond to:

Personally, I do not have a need to eat lunch in the home care group. I’d rather eat lunch in the nursing group. I would risk getting three post-its with stuff I need to react on when I leave there. That could lead to us getting involved earlier [in the citizen pathways], but I am also under pressure. I also sometimes do what is easiest for me. (Nurse)

This example illustrates the nurses’ efforts to defend professional and organizational boundaries and their need to prioritize their own work due to perceived time pressure, although they also acknowledged that such efforts did not enable them to work closer together with care workers.

4.1.3 Creating New Organizational Boundaries

The nurses also protected their time and resources by constraining interactions with care nurses. A central example in the interviews was that of “telephone hours”. Restricted telephone hours had been implemented in the health care units to limit direct access to the nurses: “We have been working on that for a long time because it is a matter of interrupting the nurse working in the field”. It meant that the care workers could only access the health care units at a fixed time during the day through a nurse coordinator, who forwarded their inquiry to the responsible nurse. Again, the efforts to defend the nurses’ needs and preferences served as barriers to discuss citizen matters:

We are challenged by not having any [nurses] in our group. We have to call someone. We can’t always get through to them, and they don’t always have the time to come to us or the citizen when there is a problem. […] I think this can be a problem—that we don’t have them close by. (Care worker)

As shown in the above extract, the limited access to the nurses was associated with the organizational and physical separation of the professional groups constructed by the organizational context.

4.1.4 Withdrawal in Response to Organizational Distance

The care workers associated the salient efforts of nurses to defend boundaries with hierarchical relations. A frequently reported example regarded the nurses’ tendency to call the home care units and ask them to come to a citizen’s home to change a diaper while the nurse is conducting nursing tasks:

I can feel a hierarchy with the nurses. For example, when there is a nurse in a home, and the citizen has defecated, then the nurses do not want to help, and then they call us, and I do not think that is OK. (Care worker)

These actions served to demarcate practice domains. The care workers would typically respond to such experiences by withdrawing from interactions. Lack of access, trust, and feelings of hierarchical relations made the care workers less inclined to contact the nurses or share their observations, e.g. in case conferences. Another care worker explained the role the organizational context played:

The disadvantage [with functional units] is that it creates distance in our contact. They [the nurses] need to send written tasks where two words spoken could have solved it. We don’t work together when working with the citizens, but in parallel […] I am like: “What do we do in this case?” And then I do what I think, and others do what they think. (Care worker)

The care workers did not possess the autonomy and power to influence boundary work efforts, and they associated this lack of influence not only with their position in the hierarchy but also the organizational context they worked within. They expressed feeling “left alone” in the citizen pathways and, as a consequence, would move on with their work without counseling the nurses and “just do it myself”. This emphasized feelings of “losing out” as a consequence of being at “the bottom of the hierarchy” in a position where they depended on the nurses to give them tasks “appropriate for our level of education”. This withdrawal strategy was associated with temporary breakdowns in collaboration across boundaries and was interpreted as a competitive form of boundary work, occurring in response to the defending and creating strategies connected to the nurses’ practices.

4.1.5 Accommodating to Restore Relations across Boundaries

Another, more collaborative, response strategy for the care workers was accommodating to the defensive boundary work of nurses. This strategy was evident in how care workers explained or defended the nurses’ lack of prioritization of interprofessional interactions. A common explanation made by the care workers was that the nurses had even busier schedules than their professional group and, therefore, could not prioritize participating in case conferences:

Sometimes, none of them come [nurses to the case conferences], and [if they come] they’re not prepared. They are not interested. They are under extreme pressure, more than the rest of us, and you’ve got to bear that in mind. (Care worker)

Thus, care workers would justify the nurses’ defending practices by referring to the conditions they worked under or by doing the tasks themselves—such as driving to a citizen’s home to change a diaper. The purpose of this strategy seemed to be to ensure future connection.

4.1.6 Reworking Organizational Noundaries to Enable Connection

The interviews did report examples of professionals sharing their direct phone numbers with each other in order to work closely together in complex care pathways. However, such blurring of boundaries was coined as acts of “civil disobedience”, and it seemed to only take place when the nurses experienced that the organizational context prevented them from collaborating efficiently with care workers:

We have a few terminal patients. Then they [care workers] get our direct number, so they don’t have to go through a switchboard […] You could call it civil disobedience […]. There’s a huge value in this. Because we know the care workers and their competencies […] and that they can give a quick answer. (Nurse)

A central prerequisite for effective phone contact, however, was mutual trust and familiarity, as emphasized by the nurse in the extract above. The extract also shows that only the nurses had the ability to shift the boundary work mode, but when they did so, it was connected to experiences of working together across boundaries.

4.2 A Collaborative Boundary Work Mode in the Integrated Units

4.2.1 Familiarity and Trust Enable Collaboration through Differentiation

Nurses and care workers in the integrated units experienced working closely together in the care pathways. They viewed collaboration across boundaries as necessary because each professional group depended on the other’s area of expertise: “We are better prepared to deliver care when we discuss the citizens together”. Despite their different professional training, the two groups were able to discuss and share knowledge through a clear division of roles and acknowledgment of each other’s contributions to the care pathways. Thus, valuing the professionals’ differences served as the basis for collaboration, as evidenced here:

[…] Conversely, the nurses came to us for information. It was nice that we could use each other in that way. […] I definitely felt that our views were heard, so we had a good professional discussion. We were all able to contribute something to the different professional groups. (Care worker)

The care workers emphasized that their knowledge of the citizens “was heard” and applied by the nurses. Similarly, the nurses explained that they depended on the care worker’s knowledge to perform their tasks in the care pathways. That both professional groups drew on collaborative strategies through their professional differences is exemplified here:

In citizen pathways, we use the knowledge of the patients that the care workers have. I really make use of their knowledge. There’s no reason to arrive in the middle of the midday nap and really start off on the wrong foot in a pathway. (Nurse)

The professionals also valued being organized together in integrated units because they experienced having easy access to each other given that they worked from the same office spaces. This enabled them to get to know and trust each other’s skills over time and was typically referred to as “knowing what our colleagues stand for”.

4.2.2 Negotiation on the Basis of a Shared Citizen Base

It was also evident in the interviews that the professionals worked together around the citizens serving as boundary objects (Meier 2015). This was possible because the nurses and care workers shared a small citizen base. A clear distinction of roles based on knowledge and competencies further enabled the professionals to distribute tasks flexibly. They explained that they would renegotiate tasks and responsibilities according to each citizen’s needs typically at case conferences, in morning meetings or by phone throughout the shift. The professionals valued this opportunity to flexibly divide tasks because they associated such boundary negotiations with increased continuity and quality in care delivery. A care worker, for example, explained that “one of the good things about working in a team” is that the professionals can cross boundaries to help each other in a collaborative way and that this “swapping both ways” would not lead to “any frustration”. The nurses also valued this way of working where professional boundaries were drawn situationally based on the citizen’s needs and the resources at hand:

If someone is sick, and I am going to the citizen anyway, then I might as well empty the trash can while taking care of the wound. It releases some energy to the others and gives a better collaboration. I don’t think people are that afraid of calling each other if there is something we are worried about. (Nurse)

For the care workers, this flexible division of tasks was furthermore associated with recognition from the nurses, “a pat on the shoulder”, and professional development because it increased the amount of healthcare tasks they performed.

4.2.3 Building Mutual Trust through Downplaying Boundaries

As exemplified in the extract above, the nurses and home care workers reported that they were “not afraid” to reach out to each other when they needed to discuss matters concerning the citizens. Trustful relations appeared as the basis for negotiating boundaries. Nurses needed to be able to trust the care workers when delegating tasks and responsibilities, and the care workers needed to trust the nurses when sharing their knowledge and observations: “When we have meetings, it’s important that you feel safe to say something without sounding stupid”, a care worker framed it. A strategy of downplaying boundaries enabled building trustful relationships, and the nurses did this by acknowledging the care workers’ efforts:

We have had a lot of staff turnover in our team but it is about creating relations and discussing the citizen, so we know we can call each other. That gives a lot of security. By [nurses’] highlighting and acknowledging our efforts, we are better able to carry out our tasks. So, relations between professionals working together are very important. (Care worker)

The interviewed nurses had experienced that they could contribute to relations based on equality and trust by acknowledging care workers’ contributions and emphasizing similarity with them (rather than affirming superiority): “I’m not just a nurse, but also the person [name], and I think that’s important too” (Nurse). A care worker similarly coined this downplaying strategy of the nurses showing they are “just as human as we are”.

4.2.4 Demarcation as a Prerequisite for Collaboration

The professionals emphasized that the use of these strategies of differentiation and negotiation of responsibilities, roles and tasks was based on a high competence level of each professional group. While the care workers’ professional development was ensured through interactions with nurses, the nurses emphasized a need to have access to talk to other nurses. They explained that their professional development and ability to take on an authoritative role as the clinical leaders in the care pathways relied on being able to discuss tasks and complex citizen cases with other nurses: “It’s important that I have nursing colleagues that I can ask for advice”. Thus, they clearly demarcated nursing work from care work and pointed to a need for their professional group to have certain privileges:

The way we’re organized is best for the quality of the care we provide to the citizens, but the nurses have to be able to sit together. All occupational groups need to be able to discuss citizen-related matters with each other. But when you think of all the situations we encounter, I would say our need is even greater. (Nurse)

As is seen here, the nurses created physical and organizational boundaries between them and the care workers. These boundaries included having their own lunch breaks and own office space, and prioritizing competence development activities with other nurses. This demarcation strategy reflected a competitive mode but was framed as a basis for engaging in collaborative boundary work. However, while the care workers would “prefer to always have the nurses around”, they expressed understanding of the nurses’ need to develop their skills and knowledge together, as “they bring a higher level of professionalism in order to make us better equipped”.

5 Discussion

By identifying an interplay between organizational context and boundary work, we contribute to ongoing discussions in organization studies on how elements of organizational context influence variations in professionals’ boundary work. While most studies have focused on the one-way impact of organizational context on boundary work, we show how elements of the organizational context shape boundary work through relational aspects and also how boundary work may shape the organizational context, suggesting a reciprocal relationship. Based on our findings, we argue that our contribution to the literature on boundary work can be articulated in three ways.

First, our study demonstrates how elements of the organizational context can support or hinder relational aspects essential for collaborative boundary work. This aligns with previous studies that have emphasized the importance of face-to-face interactions, proximity, and co-location in fostering familiarity and trust (Hinds and Bailey 2003; Hinds and Mortensen 2005; King and Ross 2004) as facilitators of interprofessional collaboration (Hald, Bech, and Burau 2021) and coordination (Räcker, Geiger, and Seidl 2024). It also aligns with research linking trust and familiarity to collaborative boundary work, such as Meier (2015), who shows how mutual trust fosters collaboration between healthcare professionals in hospital wards, and Weber et al. (2022), who theorize that trust in the collaborating partner is a necessity for collaborative forms of boundary work. We extend the literature by connecting these perspectives and showing that elements of the organizational context influence the development of relational aspects like trust and familiarity, and, consequently, professionals’ ability to enact collaborative-oriented strategies. Specifically, we show that in integrated units, the close physical proximity of nurses and care workers facilitated trust-building and familiarity, which, in turn, enabled collaborative boundary work. In contrast, the organizational and physical separation in functional units limited face-to-face interactions and hindered trust-building, particularly for care workers, whose hierarchical distance from nurses exacerbated distrust and fostered competitive strategies. These findings thus underscore the critical role of organizational context in fostering or hindering the relationship dynamics connected to collaborative boudary work strategies.

Second, we show how the organizational context interacts with professional status to influence how different professional groups engage in boundary work. While previous studies have found that higher-status professionals often defend the status quo and lower-status professionals seek to expand or change boundary configurations (Bucher et al. 2016; Comeau-Vallée and Langley 2020), our findings suggest that these tendencies vary depending on the organizational context. In functional units, the organizational separation compounded care workers’ lower status by further limiting their ability to influence boundary negotiations. This led them to rely more heavily on accommodating defensive practices or withdrawing from interactions altogether. In contrast, the proximity and shared responsibilities in integrated units empowered care workers to leverage their knowledge and professional contributions, enabling them to negotiate professional boundaries. For nurses, functional units fostered competitive boundary work, where they actively defended organizational and professional boundaries to protect their interests or selectively blurred boundaries when it suited their interests. By comparison, in integrated units, nurses adopted collaborative boundary work strategies, emphasizing negotiation and downplaying boundaries to build stronger relationships with care workers. Thus, the boundary work modes of professionals were influenced not only by their hierarchical status but also by the organizational context. While lower-status professionals typically aim to expand or change professional boundaries, as found in integrated units, when the organizational context limits their capacity to do so, as in functional units, they may adopt accommodating or withdrawing practices that reinforce existing demarcations. Similarly, higher-status professionals may generally seek to defend the status quo, as seen in functional units, but in organizational contexts that support trustful relationships, they may be more willing to negotiate and downplay boundaries.

Third, we argue that professionals’ boundary work is not only influenced by the organizational context but also actively shapes it. The literature has only minimally addressed this reciprocal relationship (e.g., Carmel 2006; Mørk et al. 2012). Instead, most studies focus on how contextual factors and professional identities shape boundary work (e.g., Liberati 2017; Weber et al. 2022) and primarily frame boundary work as a response to organizational triggers (e.g., Järvinen and Kessing 2021). Our findings thus contribute to the literature by demonstrating this two-way relationship between organizational context and boundary work. This was especially visible through nurses’ efforts to protect their professional interests by establishing and maintaining organizational boundaries. In integrated units, nurses created mono-professional spaces, such as dedicated offices or nursing-only meetings, to separate their work from that of care workers. In functional units, they defended existing boundaries between nursing and care work and implemented elements like restricted telephone hours, significantly limiting interprofessional interactions. These deliberate actions illustrate how boundary work can shape the organizational context by solidifying boundaries that restrict interactions and define who participates in joint tasks (Räcker, Geiger, and Seidl 2024). By reinforcing professional and organizational boundaries, nurses contributed to the dominance of competitive boundary work in functional units, which perpetuated organizational separation and hindered the development of collaborative relationships, thereby reshaping the organizational context itself. This ability to influence elements of the organizational context through boundary work varied with the hierarchical status of the professional groups, where nurses, as the higher-status group, had this ability, while care workers, as the lower-status group, did not. In line with this, Hald et al. (2024a) found that nurses and therapists – in contrast to care workers – have the capacity to influence interprofessional collaboration by “inventing and establishing new mechanisms” with this ability varying according to the relative autonomy of the professional groups. Our findings nuance the currently under-theorized relationship between organizational context and boundary work identified in the literature, showing that organizational context is neither stable nor disembedded from the professionals’ everyday practices. This suggests that the interplay between boundary work and organizational context is both dynamic and mutually constitutive.

Altogether, the findings of our study may have significant implications for practice, particularly regarding interprofessional collaboration between nurses and care workers in the eldercare sector. Our study emphasizes that the organizational context can either support or hinder this collaboration. When nurses and care workers had limited interactions, trust-building was hindered, which in turn impeded interprofessional collaboration. Conversely, organizational contexts that promoted proximity, co-location, and frequent interactions facilitated trust-building, thereby supporting interprofessional collaboration. These insights align with previous research on interprofessional collaboration (Hald, Bech, and Burau 2021; Hald et al. 2024b; Johnson et al. 2020; Seaton et al. 2020) and suggest that improving collaboration requires an organizational context that enables frequent face-to-face interactions, allowing professionals to build trust and familiarity. Additionally, although both nurses and care workers valued their distinct professional identities and competencies, our findings show that delivering holistic care required minimizing hierarchical divides and fostering shared responsibilities across professional boundaries, which strengthened the sense of professionalism among care workers. In organizational contexts where interprofessional collaboration was difficult to achieve, our findings suggest that the professional development of lower-status groups, such as care workers, was hampered. It is therefore crucial to create policies and organizational initiatives that promote shared responsibility, particularly in the eldercare sector, where integrated, high-quality care depends on strong interprofessional relationships (Reeves et al. 2017).

Finally, a limitation of this study is the reliance on interviews rather than ethnographic methods to examine boundary work. Future studies could address this by further nuancing and unfolding the complex interplay between boundary work and organizational context and the multiple ways these may interact. We suggest that boundary work research explore broader aspects of organizational context, as current studies have often focused narrowly on micro-level features, such as task urgency (e.g. Liberati 2017; Nugus et al. 2010). A way forward may be to step outside of the healthcare sector, particularly the hospital setting, to pursue insights into diverse contextual features and situatedness of professionals’ practices (Reay et al. 2017). In accordance with other scholars (Langley et al. 2019; Liberati 2017), we therefore argue that comparative and ethnographic approaches would provide a richer understanding of not only how, but also why professionals engage in boundary work in specific ways under varying conditions.

Funding source: Danish Ministry of Social Affairs, Housing and Senior Citizens

Theoretical framework.

| Form | Modes | Examples of micro-strategies from empirical studies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative boundary work | Negotiating boundaries Embodying boundaries Downplaying boundaries |

|

|

|

|

||

| Blurring boundaries to prevent unequal power relations | Eliassen and Moholt (2023) | ||

| Bending role boundaries in pursuits of more fluid role demarcations | Bos-de-Vos, Lieftink and Lauche (2019). | ||

| Competitive boundary work | Defending boundaries Contesting boundaries Creating boundaries |

|

Comeau-Vallée and Langley (2020) |

| Making boundaries to construct a hierarchical division of roles | Eliassen and Moholt (2023) | ||

|

Bos-de-Vos, Lieftink and Lauche (2019) | ||

Overview of types of boundary work articulated in the data material.

| Micro-strategies of boundary work | Examples from the data material | |

|---|---|---|

| The competitive mode |

Defending

Professionals defend existing professional/or organizational boundaries to support and protect the task domains Defending serves to limit occasions for interprofessional coloration and interactions characterized by hierarchical relations with reference to the needs of one’s own professional group Defending professional boundaries can be seen when the professionals emphasize what they gain from having access to and interactions with members from their own professional group, e.g. by not eating lunch with the other professional groups Examples of defending organizational boundaries are when the professionals are occupied with showing resistance towards management proposals to integrate home and health care |

“Personally, I do not have a need to eat lunch in the home care group. I’d rather eat lunch in the nursing group. I would risk getting three post its with stuff I need to react on when I leave there. That could lead to us getting involved earlier [in the client pathways] but I am also under pressure. I also sometimes do what is easiest for myself”. (Nurse) “I can feel like home care is a bit far away. On the other hand, I do not want to be separated from my nursing colleagues, because I think the sparring is great, so I do not want to sit in home care”. (Nurse) “I can feel a hierarchy with the nurses. For example when there is a nurse in a home, and the client has defecated, then the nurses do not want to help, and then they call us and I do not think that is OK”. (Care worker) |

|

Creating

New organizational structures are created to protect the professional groups’ time and resources, e.g. when phone hours are implemented in the health care units to lower the inquiries from home care Employing this strategy serve as a barrier for interprofessional collaboration Profession boundaries are also created by refraining to conduct certain tasks, e.g. when nurses refrain from conducting personal care tasks with reference to their professionalism Creating is based on differentiation as the professional groups have different knowledge and conduct different tasks, and create professional or organizational boundaries with reference to the professional differences |

‘Telephone contact – they [care workers] are not allowed to do that. We have been working on that for a long time because it is a matter of interrupting the nurse working in the field. It turned out that they should call the emergency phone. The challenge is that it is very difficult to get through’. (Nurse) “[The nurses] talk a lot about how we disturb them too much. I have no way of knowing how busy they are, but when we have something that really belongs under the nurse then she is also the person we need to contact. Years back, it didn’t use to be like that, it has gotten worse”. (Care worker) ‘We are challenged by not having any [nurses] in our group. We have to call someone. We can’t always get through to them, and they don’t always have the time to come to us or the patient when there is a problem. They say, “We’ll come by later”, and we can say this to our patient and then they have to wait. I realize they can’t be there in 5 min because they have to cover a large area. I think this can be a problem – that we don’t have them close by’. (Care worker) |

|

|

Demarcation

Demarcation serve to confer privilege to the professional group by marking the differences between “them and us” The purpose is to create spaces to allow focus on each professional group to support each groups’ professional development ‘Monoprofessional’ spaces concern office spaces, lunch breaks, educational activities, meetings |

“The way we’re organized is best for the quality of the care we provide for the patients, but the nurses have to be able to sit together. All occupational groups need to be able to spar with each other. But when you think of all the situations we encounter, I would say our need is even greater”. (Nurse) | |

|

Withdrawal

Withdrawing from interprofessional interactions occurs when professionals are met with competitive boundary work practices or non-functioning organizational structures and leads to momentary break downs in collaboration Not attempting to collaborate, e.g. not calling each other on the phone Not sharing observations or refraining from dialogue during collaborative interactions due to lack of familiarity and trust Attempts to collaborate is hampered by the organizational structures, e.g. limited phone access |

“It [telephone contact] takes a lot of time, when you don’t have enough time for it. You keep being passed on to someone else, until you get hold of someone [a nurse] who is willing to take care of it. […] It’s a bit like, “I’m very busy, call her”, or “that’s not my area”. I think it varies a lot whether the collaboration works well”. (Care worker) “Our assistants have been in situations where they are told that they [the nurses] can’t pay visits now. These situations are unpleasant for both the patient and the assistant, where you don’t feel you get any support. This is inacceptable, and they feel insecure because they really have no one to call”. (Care worker) “You can feel left alone. There are multiple times where I have thought ‘I’ll just do it myself’, because when I tell the nurses about a problem with a client they say: ‘We are just getting started on that’” (Care worker). “The disadvantage [with separated organizing] is that there is a long way for contact. They [the nurses] need to send written tasks where two words spoken could have solved it. We don’t work together around the clients, but in parallel” (…) “There is no mutual plan. The different professions do different things. I am like: ‘What do we do in this case?’ and then I do what I think, and others do what they think” (Care worker) |

|

| The collaborative mode |

Differentiation

Differentiation serves as the basis for collaboration due to the difference in tasks, knowledge, competencies and level of authority among the professional groups The differentiation strategy appears when the professionalsvalue and draw on each other’s knowledge and competencies and experience contributing to the client pathways Seeking dialogue in efforts to share observations and knowledge about the clients Seeking dialogue in efforts to delegate tasks in the client pathways Relations based on familiarity, trust, and knowledge of each other’s competencies are prerequisites for collaboration through differentiation |

“In my opinion, when we work with the nurses who know us, then they also know what they can expect of us. I feel that I get help and sparring from them. We really need them, but the problem is that we don’t have very good access to them”. (Care worker) “It would be better if they [the nurses] met here, because there is actually only dialogue which becomes very formal. We benefit a lot from each other, but the organization makes it difficult. Task solution would be better if we had better access to the nurses”. (Care worker) “Conversely, the nurses came to us for information. It was nice that we could use each other in that way. […] I definitely felt that our views were heard, so we had a good occupational sparring. We were all of us able to contribute something in the different occupational groups”. (Care worker) “When we are such a small group we get to know each other well and we know how to talk to each other. We also know each other’s competencies. It is important for my work to be familiar with the care workers, because if I know what the others can do, then it is easier for me to delegate”. (Nurse) ‘It definitely gives a better client pathway when we all talk together and can talk so informal within our team because then everyone knows what is going on. We update each other all the time. It gives better care for the clients. (Care worker) |

|

Accommodation

The accommodation strategy serves to accept competitive practices in order to enable collaboration at a later time. Silent acceptance of rejections to collaborate from other professionals Efforts to explain, defend or justify rejections to collaborate from other professionals |

‘Sometimes, none of them come [nurses to the case conferences], and they’re not prepared. They are not interested. They are under extreme pressure, more than the rest of us, and you’ve got to bear that in mind’. (Care worker) | |

|

Blurring

The purpose of blurring boundaries is to enable collaboration when collaboration is not otherwise possible, e.g. by enabling direct phone contact although this is not the formal ways of doing Blurring is based on trustful relations among individuals who know of each other’s competencies |

“It’s an advantage to have known the nurses for many years, so you can ask them and talk to them, but this isn’t the proper chain of command. This [the familiarity] is lost when the old ones [care workers] move on, because the new ones never get to know the nurses like the old ones used to”. (Care worker) | |

|

Negotiation

Negotation refers to practices of flexible task delegation which is based on each client’s need, e.g. when a nurse gives a shower together with wound care Collaboration through differentiation serves as a basis for negotiation Negotiation occurs through the client as a boundary object and the ability to effectively arrange bed side training Knowledge of each other’s competencies is a prerequisite for flexible task delegation |

“The care workers often call if they are unsure of something. The communication between the professional groups is good, and we don’t mind doing each other’s’ tasks if there’s a lot to do”. (Nurse) “When you have meetings, it is important that you feel you can say something without worrying about it sounding stupid. People aren’t afraid to speak their mind in a small group where you know each other and the patients. So it gives a kind of security that know each other’s’ competencies and the colleagues that we work with”. (Care worker) |

|

|

Downplaying

Acknowledging and drawing on each other’s contributions in the client pathways Emphasizing similarity with the other professional groups and downplaying hierarchical differences |

“I’m not just a nurse, but also the person [name], and I think that’s important too. I don’t mind mixing with the other occupational groups, I don’t feel that’s beneath me, but some people do. […] no one is indispensable. All the occupational groups are equally important”. (Nurse) ‘We have had a lot of staff turnover in our turn, but it is about creating relations and discussing the client, so we know we can call each other. It gives a lot of security. By high lighting and acknowledging our efforts we are better able to carry out our tasks. So relations between professionals working together is very important’ (care worker). ‘They [the nurses] come to me, they come to us, and come to the assistants to ask about things. They are just as human and insecure as we are. They are just as important regarding certain things as we are. I think it is a well-spent effort that they do that. Because it used to be a bit like the nurses were better than us, but I don’t feel it’s like that anymore’. (Care worker) |

References

Abbott, Andrew. 1988. The System of Professions. An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226189666.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Axelsson, Runo, and Susanna Bihari Axelsson. 2006. “Integration and Collaboration in Public Health–A Conceptual Framework.” The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 21 (1): 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.826.Search in Google Scholar

Bach, Stephen, Ian Kessler, and Paul Heron. 2012. “Nursing a Grievance? the Role of Healthcare Assistants in a Modernized National Health Service.” Gender, Work and Organization 19 (2): 205–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00502.x.Search in Google Scholar

Beijer, Ulla, Emme-Li Vingare, Hans G. Eriksson, and Oie Umb Carlsson. 2018. “Are Clear Boundaries a Prerequisite for Well-Functioning Collaboration in Home Health Care? A Mixed Methods Study.” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 32 (1): 128–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12438.Search in Google Scholar

Bos-de Vos, Mariana, Bente M. Lieftink, and Kristina Lauche. 2019. “How to Claim what Is Mine: Negotiating Professional Roles in Inter-organizational Projects.” Journal of Professions and Organizations 6 (2): 128–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joz004.Search in Google Scholar

Bucher, Silke V., Samia Chreim, Ann Langley, and Trish Reay. 2016. “Contestation about Collaboration: Discursive Boundary Work Among Professions.” Organization Studies 37 (4): 497–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615622067.Search in Google Scholar

Carmel, Simon. 2006. “Boundaries Obscured and Boundaries Reinforced: Incorporation as a Strategy of Occupational Enhancement for Intensive Care.” Sociology of Health and Illness 28 (2): 154–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00486.x.Search in Google Scholar

Comeau-Vallée, Mariline, and Ann Langley. 2020. “The Interplay of Inter- and Intraprofessional Boundary Work in Multi-Disciplinary Teams.” Organization Studies 41 (12): 1649–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084061984802.Search in Google Scholar

Dahle, Rannveig. 2003. “Shifting Boundaries and Negotations on Knowledge: Interprofessional Conflicts between Nurses and Nursing Assistants in Norway.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 23 (4/5): 139–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330310790552.Search in Google Scholar

Duner, Anna. 2013. “Care Planning and Decision-Making in Teams in Swedish Elderly Care: A Study of Interprofessional Collaboration and Professional Boundaries.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 27 (3): 246–53. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.757730.Search in Google Scholar

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 2021. “What Is the Eisenhardt Method, Really?” Strategic Organization 19 (1): 147–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127020982866.Search in Google Scholar

Eliassen, Marianne, and Jill-Marit Moholt. 2023. “Boundary Work in Task-Shifting Practices – a Qualitative Study of Reablement Teams.” Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 18 (1): 2106–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2022.2064380.Search in Google Scholar

Farchi, Tomas, Sue Dopson, and Ewan Ferlie. 2023. “Do We Still Need Professional Boundaries? the Multiple Influences of Boundaries on Interprofessional Collaboration.” Organization Studies 44 (2): 277–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406221074146.Search in Google Scholar

Feyereisen, Scott, and Elizabeth Goodrick. 2019. “Who Is in Charge? Jurisdictional Contests and Organizational Outcomes.” Journal of Professions and Organization 6 (2): 233–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joz008.Search in Google Scholar

Finn, Rachael. 2008. “The Language of Teamwork: Reproducing Professional Divisions in the Operating Theatre.” Human Relations 61 (1): 103–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707085947.Search in Google Scholar

Fournier, Valérie. 2000. “Boundary Work and the (Un)making of Professions.” In Professionalism, Boundaries and the Workplace, edited by M. Nigel, 67–87. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Gieryn, Thomas F. 1983. “Boundary-Work and the Demarcation of Science from Non-science: Strains and Interests in Professional Ideologies of Scientists.” American Sociological Review 48 (6): 781–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095325.Search in Google Scholar

Gudnadottir, Margret, Kristin Bjornsdottir, and Sigridur Jonsdottir. 2019. “Perception of Integrated Practice in Home Care Services.” International Journal of Integrated Care 27 (1): 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICA-07-2018-0050.Search in Google Scholar

Hald, Andreas Nielsen, Mickael Bech, and Viola Burau. 2021. “Conditions for Successful Interprofessional Collaboration in Integrated Care – Lessons from a Primary Care Setting in Denmark.” Health Policy 125 (4): 474–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.01.007.Search in Google Scholar

Hald, Andreas Nielsen, Mickael Bech, Ulrika Enemark, J. Shaw, and Viola Burau. 2024a. “‘Trying to Patch a Broken System’: Exploring Institutional Work Among Care Professions for Interprofessional Collaboration.” Journal of Professions and Organization 11 (1): 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joad027.Search in Google Scholar

Hald, Andreas Nielsen, Mickael Bech, Ulrika Enemark, Jay Shaw, and Viola Burau. 2024b. “What Makes Communication Work and for Whom? Examining Interprofessional Collaboration Among Home Care Staff Using Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 38 (6): 1050–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2024.2404640.Search in Google Scholar

Hinds, Pamela J., and Diana E. Bailey. 2003. “Out of Sight, Out of Sync: Understanding Conflict in Distributed Teams.” Organization Science 14 (6): 615–32. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.14.6.615.24872.Search in Google Scholar

Hinds, Pamela J., and Mark Mortensen. 2005. “Understanding Conflict in Geographically Distributed Teams: The Moderating Effects of Shared Identity, Shared Context, and Spontaneous Communication.” Organization Science 16 (3): 290–307. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0122.Search in Google Scholar