Abstract

How do we change social orders to deliver a sustainable future? A growing literature in organization studies argues that meta-organizations are part of the answer. Meta-organizations have been shown to be well equipped for tackling grand challenges, yet paradoxically they also tend to resist change due to their inertia. In this paper, we move beyond the question of whether and how meta-organizations act as vectors of transition to address the question of how some of the defining organizational attributes of meta-organizations – which we call ‘meta-organizationality’ – create tensions for sustainability transitions. We argue that these tensions result from frictions between the imperatives of transitions, i.e. conditions for achieving broad socio-technical transformations for sustainability, and the imperatives of meta-organizations, i.e. the implications resulting specifically from their meta-organizationality. We unpack four tensions, which we frame as ‘multi-referentiality–directionality’, ‘layering–diffusion’, ‘dialectical actorhood–coordination’, and ‘multi-level decidedness–reflexivity’. We argue that transformative meta-organizations are those that successfully navigate these tensions to produce sociotechnical system changes. This work has several implications for organization studies, meta-organization studies and transition studies, and offers several avenues for research.

1 Introduction

Tackling grand challenges like ocean pollution or biodiversity losses requires profound changes in today’s social orders. Transition studies in particular argue that we need multi-level transformations in our modes of consumption and production, and that transition intermediaries are needed to translate, facilitate and accelerate such transitions (Kanda et al. 2020; Kivimaa et al. 2019). A growing literature in organization studies argues that meta-organizations, i.e. organizations whose members are themselves other organizations, are by nature well equipped to act as transformative agents and valuable facilitators for these sustainability transitions (Alo and Arslan 2023; Berkowitz and Gadille 2022; Bor and O’Shea 2022; Fernandes and Lopes 2022; Lupova-Henry and Dotti 2022; Valente and Oliver 2018). Even further, one can argue that transitions pathways and transition intermediaries co-constitute one another. However, transition studies rarely dialogue with organization studies, and we still understand relatively little about how the way meta-organizations are organized affects their transformative capacity (Köhler et al. 2019).

This gap means there is still only limited understanding of meta-organizational effectiveness, which hinders successful sustainability transitions. For instance, what are the effects of diversity of membership in transformative meta-organizations? What are the impacts of the specific dynamics of actorhood in meta-organizations? Building on decisional organization theory (Grothe-Hammer, Berkowitz, and Berthod 2022), which itself draws on systems theory (Luhmann 2018), organizationality (Dobusch and Schoeneborn 2015) and meta-organization (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008), we make the key assumption that different organizational dimensions of meta-organizations have varying effects on their ability to act as transition intermediaries. It is essential to examine whether these organizational dimensions are aligned with principles for sustainability transitions in order to understand how certain dimensions of meta-organizations facilitate transformative change in social orders (Lupova-Henry and Dotti 2022). Without this insight, efforts to address pressing global challenges like climate change and social injustice may fall short of their intended impact, thus impeding progress toward a more sustainable and equitable future (Ciplet 2022; Köhler et al. 2019). Therefore, gaining a deeper understanding of how these meta-organizational intermediaries are structured and whether and how their specific ontologies are congruent with principles for societal transformation is a critical step towards effecting meaningful change.

Meta-organizations populate all modern societies, where they play incredibly important roles. They establish norms, articulate objectives, set out means–end criteria for achieving adaptation to climate change (Chaudhury et al. 2016), and they can even build their members’ capacity for sustainable innovation and sustainable practices (Alo and Arslan 2023; Berkowitz 2018; Berkowitz, Bucheli, and Dumez 2017). However, while meta-organizations can act as facilitators of change (Bor and O’Shea 2022), their very nature means that they also produce an inertia that can ultimately resist change (König, Schulte, and Enders 2012). The nature of meta-organizations makes them liable to work against attribution of responsibility, aggravate imbalanced power dynamics, and resist change (Carmagnac, Touboulic, and Carbone 2022). Some scholarship further argues that organizational dimensions of meta-organizations affect their outcomes (Berkowitz and Gadille 2022; Chaudhury et al. 2016). The academic discourse around meta-organizations appears to carry an underlying and unthought contradiction between transformation and inertia, as meta-organizations are depicted simultaneously as slow, near-inert devices (Berkowitz and Dumez 2016; König, Schulte, and Enders 2012) but also as adaptive transition intermediaries (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Bor and O’Shea 2022).

In this paper, we move beyond the question of whether and how meta-organizations act as transition intermediaries. Rather, we address the contradictions or paradoxical tensions that meta-organizations face as they attempt to foster transformative change for sustainability transitions. We contend that meta-organizations present specific organizational attributes, which we refer to here – borrowing and building on Dobusch and Schoeneborn (2015) – as ‘meta-organizationality’. These attributes result from the intrinsic nature of meta-organizations, as ‘organizations of organizations’. Meta-organizationality includes, for instance, multi-referentiality and dialectical actorhood, which can either foster or clash with the principles of sustainability transitions. We argue that these tensions emerge from the inherent conflicts between the external imperatives of sustainability transitions, which revolve around the prerequisites for achieving comprehensive socio-technical transformations for sustainability, and the internal imperatives of meta-organizations, i.e. their distinctive attributes or specific meta-organizationality. We believe these tensions between the imperatives of transitions and the organizational imperatives of the transition intermediary are a major blind spot in both transition studies and organizational sociology or organization studies.

Here, bridging meta-organization theory and transition studies, we discuss four sets of tensions. These tensions arise from complex interplays between imperatives of sustainability transitions and the unique attributes of meta-organizations that make them paradoxical in nature as they embody potential for change but also create inertia within the transition process. On this basis, we argue that transformative meta-organizations, i.e. that produce transformative outcomes for sustainability transitions, are meta-organizations that manage to successfully navigate such tensions. We contribute to both transition studies and organization studies by shedding light on this complex interplay of imperatives and tensions that meta-organizations, as transition intermediaries, have to contend with.

The paper is organized as follows. First we review meta-organization theory, focusing on the key intrinsic organizational parameters that affect meta-organizations’ actions and impacts on society. We go on to review the literature on sustainability transitions and clarify the conditions required for sustainability transitions to achieve transformative outcomes, i.e. changes that produce broader sociotechnical regime transformation towards more sustainable practices, systems, actors, behaviors, values, and so on. Then, working up from this basis, we analyze certain tensions that emerge at the intersection of meta-organization theory and sustainability transitions.

2 Imperatives of Meta-Organizations

2.1 Definitions and Contributions to Sustainability Transitions

Meta-organizations are organizations whose members are themselves organizations (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008). Meta-organization theory argues that meta-organizations are conceptually distinct from organizations formed of individuals (i.e. firms, administrations, clubs etc.) and from other forms of collective action such as networks and institutions (Ahrne, Brunsson, and Seidl 2016; Berkowitz and Bor 2018). Meta-organizations exhibit three inherent characteristics: (1) they are associative, i.e. organizations voluntarily establish and join a meta-organization; (2) they are organizations, i.e. decided social orders; and (3) their members are themselves organizations, i.e. the members are themselves decided social orders (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008). Meta-organization theory thus presents obvious connections with concepts such as partial organization (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008) but also organizationality (Dobusch and Schoeneborn 2015) and systems theory (Luhmann 2018), as all four concepts or perspectives put back at the core of organizations (see Grothe-Hammer, Berkowitz, and Berthod 2022).

The distinctive nature of meta-organizations means that the significance of their decisions shapes their functionality and dynamics (Berkowitz et al. 2022; Berkowitz and Bor 2018; Bor and Cropper 2023; Garaudel 2020). For example, members collectively form the center of authority of the meta-organization and draw on a variety of resourcing flows (Bor and Cropper 2023). As membership is voluntary, decisions often are made by consensus (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008), and meta-organizations generally aim to represent the interests of their members (Berkowitz and Bor 2018). This makes it important for meta-organizations to be recognized as a social actor, i.e. to exhibit actorhood (Grothe-Hammer 2019). However, members themselves are typically reluctant to surrender (too much of) their decisional autonomy to the meta-organization, as it would risk undermining their ability to make decisions on their own and even their ability to assert that they are independent, autonomous organizations (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008; Ahrne, Brunsson, and Seidl 2016). As a result, members also tend to resist providing the meta-level actor with organizational elements that would intrude on or limit the members’ ability to make their own decisions, such as monitoring or sanctioning of members’ actions and behaviors (Ahrne, Brunsson, and Seidl 2016; Berkowitz and Bor 2022).

2.2 Salient Attributes of Meta-Organizations: The Notion of Meta-Organizationality

In this section, we discuss four key attributes that meta-organizations exhibit as a result of their specific nature or ontology, which we call ‘meta-organizationality’. In using the term meta-organizationality, we anchor ourselves in decisional organization theory (Grothe-Hammer, Berkowitz, and Berthod 2022). Decisional organization theory is an overarching approach that combines elements of Luhmann’s (2018) systems theory, Dobusch and Schoeneborn’s (2015) organizationality theory, and Ahrne and Brunsson’s (2008, 2019 conceptualization of partial organization and meta-organization. The approach argues that organizations or decided orders can be viewed as a continuum combining both structural organizationality or organizational components (membership, hierarchy, rules, monitoring, and sanction) and entitative organizationality (i.e. actorhood, collective identity, and interconnected decision-making processes). Drawing on the definition of decision as a communication event that has paradoxical consequences (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008; Luhmann 2018), the approach also describes the specificities of decided orders in terms of decidability, change, and layering of social orders in contemporary society.

Here, we mobilize this conceptualization and describe four salient dimensions of meta-organizationality that are significant for meta-organizations as transition intermediaries (1) multi-referentiality, (2) layering of social orders, (3) dialectical actorhood, and (4) multi-level decidedness. Our conceptualization thus means that meta-organizationality may present other dimensions, but we do not review them all here.

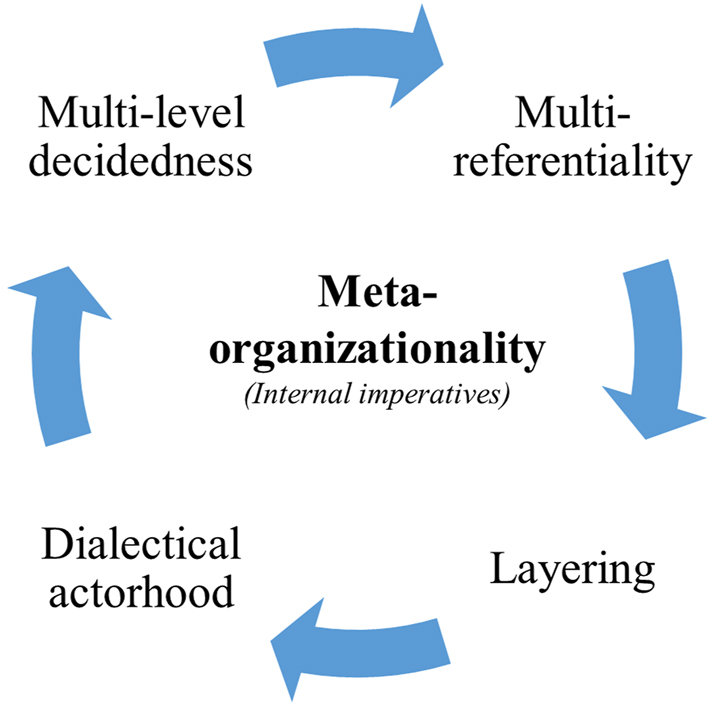

We synthesize the interconnected imperatives in Figure 1.

Meta-organizationality: internal imperatives of meta-organizations as transition intermediaries.

First, multi-referentiality in meta-organizations refers to the diverse range of norms, values, and perspectives brought together by the multiple constituent organizations that are its members, each with its unique identity, values, logics, and structures (Apelt et al. 2017; Berkowitz and Grothe-Hammer 2022). This multiplicity often encompasses a spectrum of potentially conflicting or divergent norms and values within the meta-organization. Moreover, we suggest that multi-referentiality also has a recursive dimension and implies that members and meta-level actors may evaluate or prioritize the meta-organization differently. While meta-organizations are by nature multi-referential, meta-organizational membership can be more, or less, homogeneous.

Multi-referentiality is heightened in multi-stakeholder meta-organizations as they have members from multiple stakeholder groups and bring together organizations from various spheres of society, each with various levels of expertise and various perspectives on certain issues (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020). Multi-referentiality challenges the ability of the meta-organization to create and draw on a collective identity. It also challenges the ability of the meta-organization to formulate a collective goal, and may generally make it harder for the meta-organization to make decisions. However, even though increased multi-referentiality might make decision processes more difficult, meta-organizations still serve as valuable spaces for collective decision-making (Berkowitz 2018). Indeed, they offer a place where differences can be brought together in one overarching forum that makes the collective decision possible (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Corazza, Cisi, and Dumay 2021). Meta-organizations can bring together multiple stakeholders, even with very divergent interests, and enable them to make joint decisions and co-regulate themselves on strategies for protecting common goods (Corazza, Cisi, and Dumay 2021; Fernandes and Lopes 2022).

Second, meta-organizations are by nature complex, as they consist in a layering of social orders (Grothe-Hammer, Berkowitz, and Berthod 2022). Existing social orders (those of member organizations) are brought together to create a new overarching layer of social order (the meta-organization). Note that this does not supplant or substitute the existing social orders; rather, it adds a new layer. This complexity often grows further as meta-organizations tend to become part of meta-meta-organizations (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008; Brankovic 2018; Karlberg and Jacobsson 2015), and even extreme cases of meta-meta-meta-meta-meta-organizations (see Grothe-Hammer, Berkowitz, and Berthod 2022). What happens is that for each additional layer to be relevant, they need a mandate, i.e. a set of questions or issues they can make decisions about, which means that a lower layer needs to vest some of its decisional authority to the higher layer (Bor and Cropper 2023). However, as layers get added, it becomes increasingly difficult to know who has the authority to make decisions and who is accountable for having made these decisions (Bor 2014). The complexity of this social order layering also means that decisions need to be taken at multiple levels – at the level of the members, at the level of the meta-level actor, and at any further levels layered on – which can typically result in slow decision-making, especially in areas where no decisional authority was previously vested or given to a higher level. Furthermore, meta-organizations may find it difficult to trigger transformations and react to external change (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008; Kerwer 2013; König, Schulte, and Enders 2012). Its members will likely have the power and motivation to resist any decisions that would demand significant changes from themselves as member organizations, which thus results in inertia.

Third, and in relation with multi-referentiality and layering, meta-organizations present a form of dialectical actorhood . We define dialectical actorhood as the complex and dynamic equilibrium that meta-organizations need to maintain between the autonomy, collective identity, accountability, and responsibility of both its members and the meta-level actor. Dialectical actorhood involves an internal facet focused on the capacity to collectively make decisions and exist as a social actor (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Fredriksson 2023), which is shaped by the autonomy–dependency interplay between members and the meta-level actor, but at the same time it also involves a relational dimension with nonmembers, i.e. the capacity to be recognized and addressable as a social actor in its environment (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Grothe-Hammer 2019).

The paradox inherent in meta-organizational dialectical actorhood arises from members’ simultaneous desire to preserve their autonomy while recognizing that they have to surrender a portion of their autonomy in order to establish an effective meta-organization that acts on their behalf (see Fredriksson (2023) on dual actorhood). Members therefore consistently seek to strike a delicate balance between maintaining their independence and ceding some control to the meta-level actor. Similarly, members have to navigate the complex task of preserving their identity while also contributing to the collective identity of the meta-organization. As Ahrne and Brunsson (2008) argue, the creation of a collective identity is needed in all meta-organizations, and it is usually made relatively easy by the homogeneity of members. However, this pursuit becomes more complex within the context of multi-stakeholder meta-organizations, as they have to grapple with the challenge of accommodating diverse perspectives and interests (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020), all while striving to establish a unified identity that can be recognized and engaged with externally (Laviolette et al. 2022).

Dialectical actorhood has significant implications for accountability and effectiveness of meta-organizations as agents of change in complex societal transitions. Accountability in meta-organizations appears to be a necessary condition for achieving sustainable transformative change (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Berkowitz and Gadille 2022). However, in meta-organizations, accountability is far from straightforward: not only is it highly complex (Bor 2019), it is also multi-directional, i.e. from members to meta-organization, from meta-organization to members, from meta-organization to environment, and from members to environment. Accountability is therefore pivotal to the dialectical nature of actorhood in meta-organizations.

Fourth, meta-organizations are characterized by multi-level decidedness , which poses specific challenges. Indeed, as mentioned earlier, meta-organizations are made up of decided social orders, meaning that one of their core characteristics is that they revolve around decisions (Grothe-Hammer, Berkowitz, and Berthod 2022), which is precisely where meta-organizations diverge from networks or institutions (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008). We therefore propose the terms “multi-level decidedness”. We define decidedness as an attribute of social orders in general and one that is particularly valuable in the context of meta-organizations. Decidedness captures the fact that social orders can be explicitly and recursively determined through nested decision-making processes, which will cumulatively generate additional and interconnected decisions, at different levels (meta-level actors, members, individuals, and nonmembers), hence the qualifier “multi-level” in the attribute of “multi-level decidedness” in meta-organizations.

Recent scholarship has unpacked the particularities of decided social orders in which the central defining features is that they revolve around decisions (Ahrne, Brunsson, and Seidl 2016; Apelt et al. 2017; Grothe-Hammer, Berkowitz, and Berthod 2022). Ahrne, Brunsson, and Seidl (2016) argue that decisions are inherently attempts to fix meaning, yet they remain subject to scrutiny and subsequent decisions prompt contestation. Decidedness further implies two characteristics: decisionality and decidability. Decisionality represents the extent to which organizationality is itself subject to decision-making (Berkowitz and Bor 2022). For instance, the decisionality of membership can vary depending on factors such as formalization of membership, self-determination of the meta-organization, categories of membership, members’ autonomy in deciding to stay, and the diversity of their contributions. Decisionality of hierarchy hinges on whether and how authority is delegated within the meta-organization. The decisionality of rules, monitoring and sanctions can be based on considerations like affordances, procedural aspects, and actual usage. On this basis, Berkowitz and Bor (2022) further emphasize the potential for meta-organizations and the dynamic processes of meta-organizing to harbor varying levels of “thinness” (with low degrees of decisionality) or “thickness” (with high degrees of decisionality). They thus distinguish between thin and thick meta-organizing. Decidability, on the other hand, relates to decidedness as it describes the actors’ ability to reach collective decisions and change social orders (Berkowitz and Grothe-Hammer 2022). The intertwining of decided and emergent social orders can lead to conflicts and potential lock-ins of social orders, which are therefore no longer decidable. This has potential impact on meta-organizations as agents for transformative change.

2.3 Meta-Organizations as Agents for Transformative Change

A growing number of meta-organizational scholars argue that meta-organizations are structurally or organizationally well equipped to tackle sustainability challenges (Alo and Arslan 2023; Berkowitz et al. 2022; Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Berkowitz and Gadille 2022; Bor and O’Shea 2022; Bor, O’Shea, and Hakala 2024; Chaudhury et al. 2016; Fernandes and Lopes 2022; Saniossian, Beaucourt, and Lecocq 2022; Saniossian, Lecocq, and Beaucourt 2022b; Valente and Oliver 2018; Vifell and Thedvall 2012). For instance, their voluntary and associative nature together with their cost-effective structure facilitates the development of efficient collaborative solutions (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020). Meta-organizations also tend to foster deliberate, grassroots-driven, consensus-driven changes within industries (Berkowitz 2018; Dotti and Lupova-Henry 2020). Meta-organizations are inclined to cultivate soft laws or standards that facilitate self-regulation across an industry (Berkowitz and Souchaud 2019; Megali 2022). Standards are seen as possible ways in which monitoring and sanctioning can be done, as it remains up to each member to choose to whether implement a given standard (Ahrne and Brunsson 2012). This literature has also demonstrated that meta-organizations can act as transition intermediaries and thus contribute to climate change adaptation (Chaudhury et al. 2016), market transformation (Valente and Oliver 2018), capacity-building or diffusion of sustainable innovation (Berkowitz 2018; Bor, O’Shea, and Hakala 2024; Saniossian, Lecocq, and Beaucourt 2022b), and commons governance and conservation (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Corazza, Cisi, and Dumay 2021; Fernandes and Lopes 2022).

Even though meta-organizations conduct various activities that can contribute to sustainability, such as capacity-building, advocacy work, or governance activities (Berkowitz et al. 2022), it is important to realize that meta-organizations can play different roles in transitions (see Bor and O’Shea 2022), from (1) member harmonizer, which might involve preserving sectoral commons (Berkowitz and Bor 2018), to (2) change protector, protecting the collective’s interest (Laurent et al. 2020), and on to (3) innovation supporter, through collective learning, capacity-building (Berkowitz 2018) and pushing certain practices among its members (Garaudel 2020), and ultimately (4) change facilitator, by effectively achieving external influence (Ahrne and Brunsson 2005), developing strategic planning (Cropper and Bor 2018) and co-constructing practices (Berkowitz and Souchaud 2019). This means that some meta-organizations might aim to actively resist change or be unable or unwilling to play a role as transition intermediary (Bor and O’Shea 2022).

Some scholars have started to investigate the darker side of meta-organizations (Carmagnac, Touboulic, and Carbone 2022) and argue that meta-organizations need to meet certain specific conditions in order to become transformative, i.e. to produce sustainability-forward change (Berkowitz and Gadille 2022). Some argue that necessary conditions for tackling ecological problems and acting as a change agent include gaining actorhood, i.e. being recognized as a social actor that is able to take decisions and being able to be held accountable for decisions made, as well as being spatially embedded, i.e. being interconnected with and influenced by a physical geographic location or territorial context, and having a multi-stakeholder membership, i.e. a diversity of members from various domains (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020).

Furthermore, another key condition enabling a meta-organization to act as a transition intermediary is “responsible actorhood” (Berkowitz and Gadille 2022). Responsible actorhood implies a number of dimensions, such as being held responsible for decisions but also ecological impacts, having reflexivity about such impacts, and jointly transforming the capacities, knowledge and work of member organizations. Under such organizational conditions, the meta-organization can ease some of the lock-ins of sustainability transition, such as path dependence of growth or competency traps. Conversely, single-stakeholder meta-organizations, such as business-only meta-organizations, can become actors that effectively resist change, as Alo and Arslan (2023) recently showed in African contexts, which reemphasizes the importance of multi-stakeholderness in membership composition.

Furthermore, some meta-organizations may perpetuate power imbalances that have adverse effects or enhance resistance to change, especially when larger players hold dominant positions and manage to elude responsibility (Carmagnac, Touboulic, and Carbone 2022). On the other hand, single-stakeholder meta-organizations may become passive or non-engaging, as the changes that are discussed affect their members differently, making it impossible for the meta-organization to find consensus on the way forward (Bor and O’Shea 2022). König, Schulte, and Enders (2012) argued that an elitist identity, which enhances a sense of superiority of the members and leads to not seeing a need for change, and a lack of champions, i.e. key promoters of change, will contribute to inertia.

This stream of literature thus highlights that specific organizational structures or organizational attributes of meta-organizations affect the meta-organization’s ability to produce transformative outcomes (Berkowitz and Gadille 2022; Chaudhury et al. 2016). However, it remains unclear whether and how this connects with principles of sustainability transitions, which is the question we now turn to.

3 Imperatives of Sustainability Transitions

Sustainability transitions are concerned with change in sociotechnical regimes. Sociotechnical regimes can be understood as “patterns of artefacts, institutions, rules and norms assembled and maintained to perform economic and social activities” (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004). Originally, the core of transition studies (Geels 2005; Geels and Raven 2006; Rip and Kemp 1998) saw sociotechnical transformation as the slow, bottom-up process of a system changing to a new equilibrium (the niche-based model; Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004). Studies on sustainability transitions (Grin, Rotmans, and Schot 2010; Loorbach 2007; Markard, Raven, and Truffer 2012) assert that sociotechnical regimes may change when demand for more sustainable sociotechnical systems is high, as it opens opportunities for sociotechnical niches to gain a foothold and challenge the existing sociotechnical regime. Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling (2004) highlight that these transitions may be coordinated, intentional efforts, either in the form of endogenous renewal – “a conscious effort [by regime actors] to find ways of responding to a perceived competitive threat to the regime” (p. 68) – or in the form of purposeful transitions, i.e. change “intended and pursued to reflect the expectations of a broad and effective set of interests, largely located outside the regimes in question” (p. 68). Our focus here is on purposeful transitions.

3.1 Characteristics of Sustainability Transitions

Sustainability transitions have several defining characteristics (Köhler et al. 2019). When sociotechnical systems develop, they tend to create stable, interlocking elements of technology, education, policy, science, etc. that make the system function effectively. Existing sociotechnical systems exhibit high degrees of inertia (Markard et al. 2020) due to interlock. As these systems are multidimensional, their elements are interconnected, which means that they co-evolve (Köhler et al. 2019). As the norms, values and understanding of the ecological and social environment are changing, there is growing demand to change this interlocked system, i.e. to make sustainability transitions. The overall goal or direction needed for the change may be fairly clear: as Köhler et al. (2019) highlighted, a sustainability transition has a normative directionality, so there is often contestation around how to get the system moving and what system elements need replacing, changing, etc. And once a change starts to happen, this creates uncertainty for the multiple actors involved in the system as the process is open-ended and often takes a long time to evolve into its new stable, interlocked system. The stream of scholarship on purposeful transitions contends that we can impact the speed of this change and thus reduce some of the uncertainty. In other words, we can actively manage these transitions.

For purposeful transitions to happen or be speeded up (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004; Markard, Raven, and Truffer 2012, 2020; Weber and Rohracher 2012) requires four key ‘ingredients’. First, there is a need to bring the various actors together to decide or explicitly articulate the desired changes, the vision of the desired future, or at least the desired direction of travel for the change (directionality; Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004; Weber and Rohracher 2012). Second, to see whether we can create the desired impact and prevent unexpected and unwanted impacts, we need to experiment, test different ideas, see whether they work and what needs changing, and then work to diffuse or scale up those ideas and the allied learning, innovation and practices that show promising results (diffusion; Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004). Third, to enable these experiments to expand, we likely need to change the policies that stand against them or put new policies in place to support coordinated change towards the same direction (coordination; Weber and Rohracher 2012). The change may well involve public policy but it can and often does also include self-regulation of an industry or domain (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004). Fourth, there is a need for a feedback system and reflexivity in order to make needed adjustments on the way (reflexivity; Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004; Weber and Rohracher 2012). Reflexivity requires information and knowledge about the various elements needed to support the new sociotechnical system, i.e. the skills and competencies, technologies, infrastructures, etc. to develop. There is a need to understand and react to unintended consequences, i.e. to adjust the vision of the desired future or the identified pathways towards it.

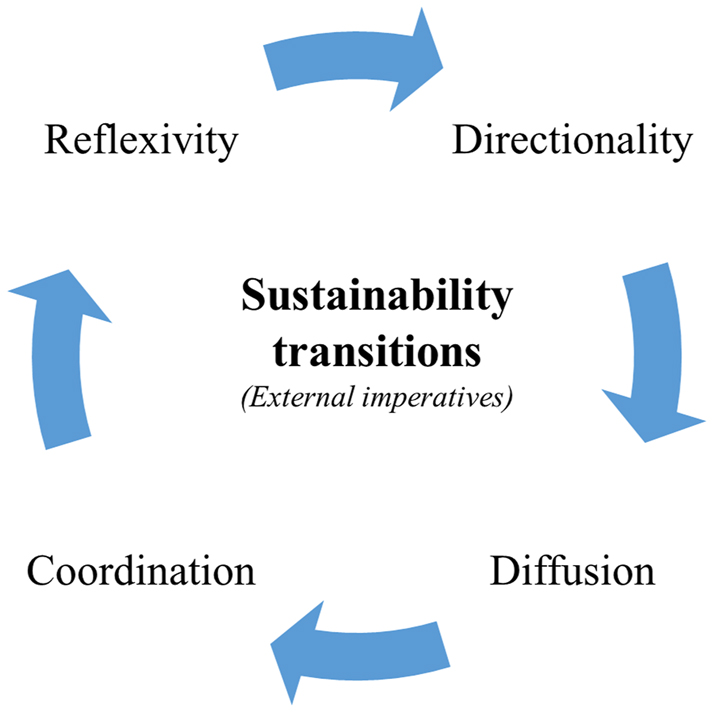

3.2 The External Imperatives of Transitions

Another angle on the above principles is that failure to achieve these four core elements can lead to specific transformational failures, as articulated by Weber and Rohracher (2012). These elements thus form the external imperatives of the sustainability transition. These external imperatives are interconnected, as schematized in Figure 2. First, transformational failures may feature a ‘directionality failure’. Directionality failure relates to the lack of guidance and sufficiently clear goal-orientation that would bring together different values that should be articulated in a common vision (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004), and so “directionality” is the first imperative. Next, a demand articulation failure, or what we will call here a ‘diffusion failure’, points to insufficiently developed markets and a failure to generalize or diffuse innovation. Indeed, developing niche innovations and experiments that can be scaled up to disrupt regime systems still requires an articulation between innovation and market demand (Markard, Raven, and Truffer 2012; Weber and Rohracher 2012). This is the “diffusion” imperative. Then, a ‘coordination failure’ highlights the importance of policy intervention and coordination across different domains, actors, sectors, etc., including through industry self-regulation. This is the “coordination imperative”. Finally, there may be a ‘reflexivity failure’ when sociotechnical systems resist adaptations, for instance when no new competencies and skills are built up or adapted, when the vision is not reformulated, and when regime systems are not transformed. This is the “reflexivity imperative”.

External imperatives of sustainability transitions.

3.3 The Importance of Transition Intermediaries

Transition research has highlighted the important roles played by transition intermediaries in the management of transitions (Kanda et al. 2020; Kivimaa et al. 2019; Mignon and Kanda 2018). These transition intermediaries have been categorized based on roles and interventions as (1) systemic intermediaries who promote an explicit transition agenda and aim to effect change on the whole system level, (2) regime-based transition intermediaries tied to the prevailing socio-technical regime but with a mandate to promote transition, (3) niche intermediaries that experiment and advance niche activities while influencing the prevailing sociotechnical system, (4) process intermediaries that facilitate change processes in support of context-specific or external priorities, and (5) user intermediaries who bridge niche technologies with other actors and translate user preferences to developers and regime actors (Kivimaa et al. 2019). Transition intermediaries are needed to achieve directionality, diffusion, coordination, and reflexivity for transformative change. However, while we understand a lot about the typologies of intermediaries based on their interventions (Kivimaa et al. 2019; Mignon and Kanda 2018), we still understand relatively little about their organizationality (Berkowitz and Souchaud 2024). Taking a closer look at systemic intermediaries for instance (Kanda et al. 2020; Kivimaa et al. 2019), we see that some of them, such as energy agencies, are individual-based organizations, whereas others, such as the Finnish Clean Energy Association, are meta-organizations.

Focusing on meta-organizations and how their internal imperatives (meta-organizationality) might facilitate or conflict with the imperatives of transitions, we turn to discuss how intermediaries organized as meta-organizations could navigate the potential tensions between their internal imperatives and the external imperatives for transition management.

4 Meta-Organizations for Transitions: Navigating Tensions

Based on the sustainability transition literature, meta-organizations that function as transformative transition intermediaries have to contribute to our specific transition principles or imperatives, i.e. direction, diffusion, coordination, and reflexivity. However, as we noted earlier, meta-organizations also present distinct meta-organizational imperatives due to their inherent characteristics. Here we focus on multi-referentiality, layering, dialectical actorhood, and multi-level decidedness.

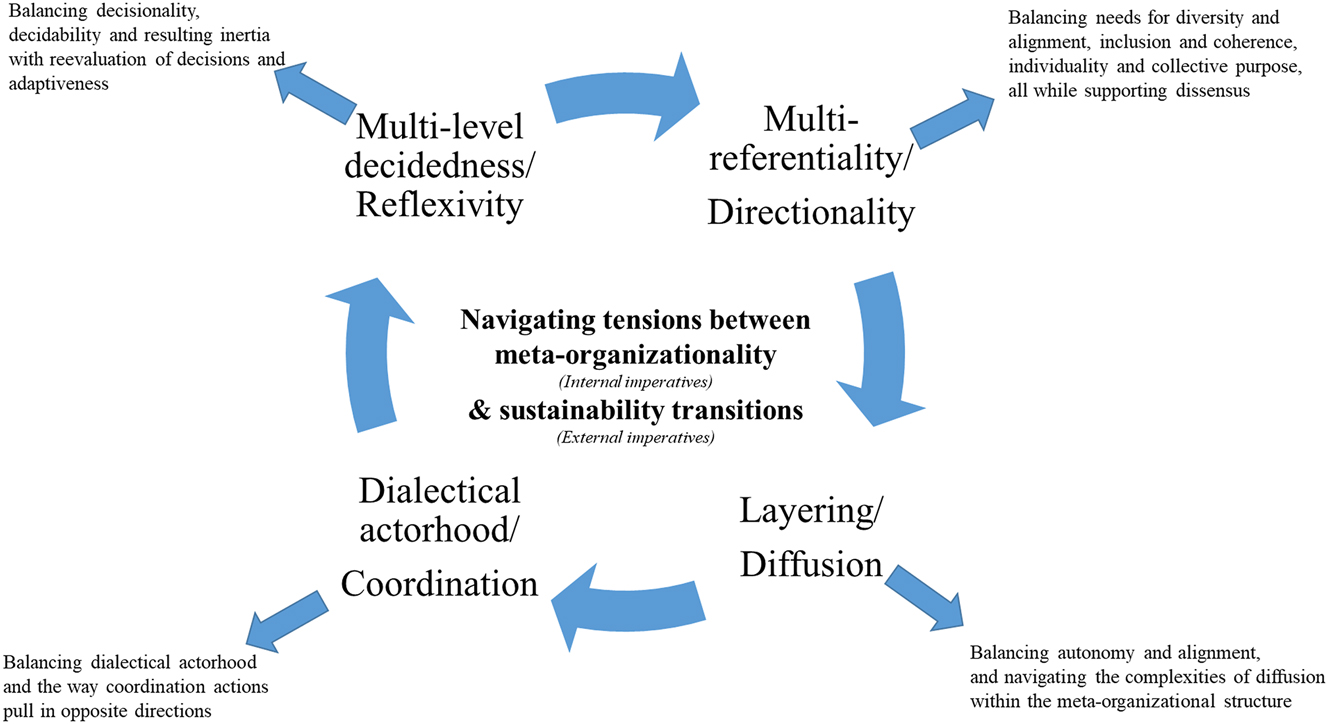

We argue that this gives rise to tensions within the meta-organizational context, as meta-organizationality and transition imperatives may involve contradictory demands or dynamics. These tensions arise from the complex interplay between imperatives of sustainability transitions and the unique attributes of meta-organizations that make them paradoxical in nature as they embody potential for change but also create inertia within the transition process. We discuss four couples of tensions (although we are aware there may be more and that they are not necessarily as tightly bounded as we present them): (1) the multi-referentiality–directionality tension, (2) the layering–diffusion tension, (3) the dialectical actorhood–coordination tension, and (4) the decidedness–reflexivity tension. Figure 3 is a schematic depiction of our analysis.

Navigating tensions between the imperatives of meta-organizationality and the imperatives of sustainable transitions.

4.1 The Multi Referentiality–Directionality Tension

This first tension lies in the inherent conflict between the necessity of multi-referentiality and the requirement for directionality within meta-organizations. On one hand, multi-referentiality is essential because it brings together diverse organizations with varying expertise, perspectives, and values, enriching the collective knowledge and fostering inclusivity. This diversity is crucial for addressing complex societal challenges and ensuring that a wide range of stakeholders have a voice in decision-making, which aligns with principles of equity and democracy: this has been shown in the case of fisheries management or crowdfunding governance (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Berkowitz and Souchaud 2019). On the other hand, directionality is equally vital in sustainability transitions (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004; Markard, Raven, and Truffer 2012), as it provides a sense of purpose, a common goal, and a roadmap for collective action. Without clear direction, efforts may become fragmented, and progress can stall.

The transition literature places emphasis on the inclusive composition of the membership, i.e. what kind of organizations can become members, and how varied that composition may be. Transition scholars argue that to deliver transformative solutions, diverse actors with a variety of motivations and priorities (Schot and Steinmueller 2018) need to gather to work together. It is crucial to bring different sets of expertise to the table, such as scientific organizations, civil society or public actors (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Caniglia et al. 2021). When several players with varying knowledge and perspectives are willing to work toward solutions, it provides a better platform to innovate and coordinate the changes needed (de Bakker, Rasche, and Ponte 2019; Loorbach 2007). Thus, multi-stakeholder meta-organizations are expected to be better geared to become transformative agents than business-only or state-only meta-organizations (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Carmagnac and Carbone 2019). However, achieving alignment on a shared vision and values is typically easier in more homogeneous meta-organizations (Matinheikki et al. 2017), and the very nature of multi-referentiality in meta-organizations introduces inherent diversity and divergence, making it harder to establish a clear direction.

Meta-organization theory has highlighted the need for similarity among members and has argued that diverse and inclusive membership creates difficulties reaching decisions and makes it hard for members to find the shared identity needed to keep them together (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008). This is particularly true of meta-organization tackling grand challenges, as the actors involved may have radically different views. There may also be significant divergences between members and the secretariat in those meta-organizations that have one (Garaudel 2020). Meta-organizations are therefore more likely to be transformative if they aim to create alignment among their members and use participation to find collective solutions as a leveler for shared identity (Weber and Rohracher 2012). However, they will also needs to accommodate dissensus, which is paradoxically needed for sustainability transitions (Schormair and Gilbert 2021). This implies the need to create long-term trust to ensure collective engagement and a collaborative mindset (Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020). In that perspective, a smaller membership size might help reach agreement more easily (Corazza, Cisi, and Dumay 2021) while also helping to align of interests and forge cohesiveness (Marques 2017).

The multi referentiality–directionality tension emerges from the need to balance these two contrasting imperatives. Meta-organizations must harness the advantages of multi-referentiality while still finding ways to establish sufficient direction to drive transformative change effectively. Striking this balance is a complex task, as it requires navigating the tensions between diversity and alignment, inclusion and coherence, and individuality and collective purpose, all while accommodating and addressing dissensus among their members.

4.2 The Layering–Diffusion Tension

The tension between the diffusion imperative for sustainability transitions and the layering and nesting characteristics of meta-organizations is rooted in the complexities involved in disseminating innovations and practices within such multi-level, interconnected structures.

The diffusion imperative in sustainability transitions captures the need to experiment with and scale up innovations and foster widespread adoption of new practices that further disrupt sociotechnical regimes (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004; Markard, Raven, and Truffer 2012). However, the layering and nesting of social orders in meta-organizations introduces certain complexities. Within meta-organizations, decision-making processes are deeply interconnected, involving multiple levels, including within the meta-level actor itself as well as its member organizations. This interconnectedness can make it challenging to achieve effective diffusion, because decisions taken at different levels may not align with each other. As discussed earlier, member organizations often maintain their autonomy while simultaneously yielding some authority to the meta-organization, which can lead to resistance to decisions that require significant changes. Furthermore, the layering and nesting of social orders in meta-organizations creates a boundary between the organization and its external environment, which may sometimes shift the priority to protecting and promoting the interests of their members. This inward orientation can prevent meta-organizations from effectively producing transformations (Bor and O’Shea 2022).

However, some works argue that meta-organizations can be powerful agents for change because they can regulate the actions of members and even nonmembers, especially through co-regulation and self-regulatory capacity (Berkowitz and Souchaud 2024; Malcourant, Vas, and Zintz 2015). Developing soft laws and standards is central for meta-organizations, because they tend to have limited possibilities for monitoring and sanctioning (Ahrne and Brunsson 2012). Standards make it possible for members to remain autonomous and in control of their decisions (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008). Although members are not technically forced to comply, they still tend to do so. Even further, decisions, including standards and norms, tend to affect nonmembers as well (Kerwer 2013). Meta-organizations also build members’ capacities, for instance for sustainable innovation, thus contributing to diffusion (Berkowitz 2018), but the existence of standards and rules like best practices can also become a source of inertia, in that members may not wish to change the standards once they have managed to secure an agreement on them.

Here, the contradiction between layering and diffusion arises from the tension between the imperative of diffusion, which requires coordinated and widespread adoption of innovations, and the intricate interconnected decision-making processes within layered and nested meta-organizations. This layering creates opportunities for diffusion, typically through capacity-building and self-regulation, but at the same time potentially creates inertia and resistance to change. This tension can impact the meta-organization’s ability to successfully drive sustainability transitions, as they have to grapple with balancing autonomy and alignment and navigating the complexities of diffusion within their unique organizational structure.

4.3 The Actorhood–Coordination Tension

The actorhood–coordination tension arises from the need for effective coordination of various actors to drive sustainability transitions and the imperative of maintaining dialectical actorhood. Dialectical actorhood creates complexities for coordination, because members have to balance their decisional autonomy, identities, accountability and responsibility with the imperative for collective decisions, collective identity, and the accountability and responsibility of the meta-level actor, and with meta-organization’s capacity to recognized and addressed as a social actor. This results in further complex accountabilities that affect the coordination imperative.

In sustainability transitions, there is a need to coordinate different policies, regulations, actors, domains and sectors so that they can work together and create a movement that pushes broader sociotechnical system change (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004; Bor, O’Shea, and Hakala 2024). In the case of a sustainability transition in energy, we would need to have directionality, e.g. agreement on the acceptability of citizen-created energy (via wind, sun, or in other ways), but we then need to coordinate the different aspects and decisions needed to make or speed up the transition, from licenses for citizens to deliver energy on to tax reductions on buying or installing solar panels or wind turbines and on further to support for innovations and services that help citizens use self-produced energy (from upgrading stoves and heating systems to infrastructures for electric vehicles). Coordinating the timing of these changes is also crucial, as some transformations are contingent on the realization of other changes in the system (e.g. innovation capabilities, development of a batteries sector, etc.).

It may seem too straightforward to propose that meta-organizations could play a coordinating role with their members and with actors of other domains, but note that the inherent dialectical actorhood of meta-organizations introduces tensions that can challenge their capacity to effectively coordinate their own members’ actions. Indeed, meta-organizations have be able to reach consensus and decide on desirable directions while holding members accountable for changes or lack of change. Members of meta-organizations, driven by the need to maintain their autonomy, may be reluctant to fully align with top-down coordinated actions, particularly if these coordinated actions appear to compromise their interests or strategies. Further, the internal dynamics of dialectical actorhood, with all its necessary negotiations and balancing acts, can heavily complexify decision-making processes for the meta-level actor. Coordinating action across different domains requires prompt decision-making, but the tensions between autonomy and collective identity at different levels may slow down the decision-making process. Dialectical actorhood also introduces complex multi-directional accountability and responsibility attribution mechanisms. The coordination imperative requires a high degree of accountability and clear attribution of responsibility, which is by nature a challenge in meta-organizations.

Here the contradiction lies in reconciling the need to balance the meta-organization’s dialectical actorhood with the imperative of coordinating actions, policies, and decisions among members to advance sustainability goals. Balancing these two aspects together is a challenge, as they might pull in opposite directions, creating a tension that meta-organizations addressing complex societal transitions have to navigate.

4.4 The Decidedness–Reflexivity Tension

The decidedness–reflexivity tension in meta-organizations is characterized by the interplay between their inherent decidedness and the imperative for reflexivity in order to negotiate sustainability transitions.

The imperative for reflexivity in sustainability transitions underscores the need for social actors in general, and meta-organizations in particular, to engage in continuous self-assessment, learning, and adaptation. Reflexivity is crucial for making necessary adjustments during the transition process, responding to unintended consequences, and ensuring that actions remain aligned with the envisioned future state of sociotechnical systems. This same reflexivity is also needed to adapt and transform skills and competences in response to the local needs of the transitions (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004; Markard, Raven, and Truffer 2012). This can be achieved in transformative meta-organizations that foster organized and decided reflexivity around ecological impacts and that facilitate the resulting transformation of labor through negotiations (Berkowitz and Gadille 2022).

However, decidedness is both needed for reflexivity and at the same time creates challenges for reflexivity. As we saw earlier, decidedness refers to the core characteristic of meta-organizations as social orders that are explicitly and recursively determined through nested decision-making processes. This recursive nature implies that decisions generate more decisions. Decidedness is further complicated by the fact that decisions are tentative attempts at fixing meaning but remain subject to scrutiny and contestation. Higher decisionality and thick meta-organizing might create inertia or even lead to a loss of decidability. We can assume that decidability is needed for reflexivity to happen. Decidability loss might lead to inertia and make change impossible (Berkowitz and Grothe-Hammer 2022).

The paradox emerges from the tension between these two imperatives. Decidedness in meta-organizations implies both stability and instability. Reflexivity demands an ongoing reevaluation of decisions and a willingness to adapt to changing circumstances, which can be either facilitated by or impeded by the decidedness of social orders in meta-organizations. This tension can be challenging for meta-organizations, as they have to balance the effects of decidedness, decisionality, decidability and inertia with the need to remain adaptable and responsive in the face of complex sustainability challenges.

5 Discussion

How do we change social orders to deliver a sustainable future? This was our initial inquiry. Existing social orders are both at the root of the problems we are facing (biodiversity loss, climate crisis, growing inequalities, etc.) yet at the same time they provide the basic foundations for developing solutions but they need to be changed before we can actually solve these problems. A growing number of studies have argued that meta-organizations are particularly well equipped to tackle such problems (Alo and Arslan 2023; Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Chaudhury et al. 2016; Valente and Oliver 2018) and therefore contribute to sustainability transitions. However, we also know that meta-organizations can be slow and near-inert devices (Berkowitz and Dumez 2016; König, Schulte, and Enders 2012). In this paper, we decided to move beyond the question of whether and how meta-organizations are transition intermediaries to address the inherent tensions that arise from meta-organizations acting as transition intermediaries. To do so, we analyzed the interrelations and contradictions between the specific organizational attributes of meta-organizations or meta-organizationality (i.e. internal imperatives), and transformative principles for sustainability transitions (external imperatives).

We started with a review of the meta-organization literature, and identified some key attributes of meta-organizationality that result from putting decision at the core of the organizational theory. Meta-organizationality includes multi-referentiality, layering of social orders, dialectical actorhood, and multi-level decidedness. Multi-referentiality in meta-organizations encompasses the presence of diverse norms, values, and perspectives from the constituent organizations, which may lead to potential conflicts and differences in evaluations. Multi-referentiality acknowledges both the variety of reference points within meta-organizations and the recursive manner in which members and meta-level actors may assess or prioritize the meta-organization differently. Layering of social orders refers to the intricate and interconnected social structures within meta-organizations, where both decided and non-decided (emerging) social orders coexist, intersect, and potentially conflict at different levels. Dialectical actorhood describes the complex and dynamic balance between autonomy, collective identity, accountability, and responsibility that needs to be maintained between members and meta-level actors within the meta-organization and nonmembers, externally. Lastly, multi-level decidedness refers to the key characteristic of meta-organizations that are explicitly and recursively determined through nested decision-making processes. As these decisions accumulate over time, they generate additional decisions that recursively affect various levels within and outside the meta-organization, including meta-level actors, members and nonmembers.

Next, we reviewed the literature on sustainability transitions to unpack the transformational principles or imperatives that are key to bringing about change for sustainability, i.e. directionality, diffusion, coordination, and reflexivity. Directionality describes the necessary guidance and sufficiently clear goal-orientation that brings together different values articulated into a common vision for the transition (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004). Diffusion describes the generalization of niche innovations and experiments that disrupt regime systems (Weber and Rohracher 2012). Coordination is required to facilitate policy interventions across domains, actors and sectors (Markard, Raven, and Truffer 2012). Lastly, reflexivity describes the transformation of skills and competencies and the restatement of vision needed to transform regime systems (Berkhout, Smith, and Stirling 2004).

On this basis, we analyzed certain tensions that arise from the required yet complex task of achieving transitional imperatives while meeting the meta-organization’s organizational imperatives. The multi-referentiality–directionality tension revolves around the need to balance the diversity of perspectives and inputs (multi-referentiality) within a (multi-stakeholder) meta-organization with the need to establish clear direction and goals (directionality) for effective transformative change. Transformative meta-organizations are those that successfully manage the dichotomy between embracing dissensus and diverse viewpoints while striving for alignment and a common vision in a bottom-up manner. Next, the layering–diffusion tension relates to the challenge of managing the co-existence of layered social orders within a meta-organization (layering) while ensuring that successful innovations and practices get scaled up and disseminated (diffusion). Transformative meta-organizations successfully address this tension through capacity-building and self-regulation while also managing potential inertia and resistance to change. The actorhood–coordination tension then arises from the imperative for meta-organizations to act as effective coordinators of diverse actors (coordination) while maintaining a balance between their own and their own members’ identity and autonomy as actors within the broader context (dialectical actorhood). Transformative meta-organizations can navigate this tension by preserving dissensus, individuality and contributing to the collective identity of the meta-organization while finding consensus on actions. Lastly, the decidedness–reflexivity tension centers on the attribute of social orders being explicitly determined through nested, recursive and cumulative decision-making processes (multi-level decidedness) and the need for feedback mechanisms and reflexivity (reflexivity) to transform existing systems. Transformative meta-organizations can navigate this tension by facilitating collective interactions and discussions without requiring decisions.

These tensions reflect the complex and often contradictory dynamics that meta-organizations have to address when they operate as transition intermediaries in their pursuit of sustainability transitions. A caveat is warranted here. We do not claim to have identified all tensions – we simply focus on four tensions that we think are particularly salient. The combinations of imperatives we selected captures the essence of these tensions and provides valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of meta-organizations operating in the context of sustainability transitions. There are clearly some overlap or forms of redundancies between certain imperatives and tensions. For instance, reflexivity implies directionality. Dialectical actorhood and multi-level decidedness both imply layering. Layering of social orders can sometimes be redundant (in terms of theoretical implications) with dialectical actorhood. The boundaries between layering–diffusion tensions and actorhood–coordination tensions may seem blurry at times. It therefore appears crucial to recognize and acknowledge these interconnections and the overlaps among dimensions, as they contribute to the complex web of challenges that meta-organizations face in their multifaceted roles as agents of change for sustainability transitions. This paper constitutes a first step in disentangling all these aspects.

5.1 Contributions and Research Agenda

Our work contributes to both organization studies and sustainability transition research by shedding light on the intricate interplay of imperatives and tensions that meta-organizations face in their role as transition intermediaries.

Organization studies and meta-organization theory. This work contributes to organization studies and meta-organization theory by extending recent efforts to conceptualize social orders in general and meta-organizations in particular, through the lens of decision (Apelt et al. 2017; Berkowitz and Bor 2022; Berkowitz and Grothe-Hammer 2022; Garaudel 2020; Grothe-Hammer, Berkowitz, and Berthod 2022; Lupova-Henry, Blili, and Dal Zotto 2021). Drawing specifically on decisional organization theory (Grothe-Hammer, Berkowitz, and Berthod 2022), we identify four dimensions of meta-organizations, or meta-organizationality, that also have importance from a transition perspective: (1) multi-referentiality, (2) layering of social orders, (3) dialectical actorhood, and (4) multi-level decidedness.

Furthermore, we have enriched understanding of the organizational dynamics and theoretical implications of meta-organizations. We propose to define a transformative meta-organization as one that not only plays a role in governing and coordinating sustainability transitions and producing changes in members and nonmembers, but that also navigates the tensions resulting from the imperatives of transitions and the imperatives of meta-organizationality. We therefore add to the growing literature on meta-organizations and sustainability broadly (Berkowitz 2018; Berkowitz, Crowder, and Brooks 2020; Berkowitz and Gadille 2022; Bor and O’Shea 2022; Bor, O’Shea, and Hakala 2024; Chaudhury et al. 2016; Lupova-Henry and Dotti 2022; Valente and Oliver 2018).

More work is needed to theoretically develop this framework and empirically investigate whether and how meta-organizations can be designed to present optimal multi-referentiality, layering, dialectical actorhood and decidedness, and ultimately successfully navigate their tensions (and what successful actually means). Indeed, our paper has focused on unpacking how meta-organizationality works and interacts with imperatives of transitions, but not how meta-organizations can be organized to manage these tensions. For instance, how much multi-referentiality is needed and how does it translate into membership composition and boundaries? How do meta-organizations actually manage multi-referentiality and to what extent does it affect their activities? How can we account for the recursive dimension of multi-referentiality, i.e. both the diversity of reference points in meta-organizations and the diverse assessments made of the meta-organization by its members and meta-level actors? How do we evaluate layering and its effects?

Looking even further, meta-organizations can set up other meta-organizations, creating (meta-…)meta-meta-organizations (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008; Brankovic 2018; Karlberg and Jacobsson 2015). What are the implications of that much layering? How many meta-levels can there be without becoming unmanageable? What strategies can meta-organizations deploy to effectively manage the dialectical tension between preserving the individuality of members and fostering collective identity and purpose at the meta-level?

And ultimately, how does the degree of decidedness influence the adaptability and responsiveness of meta-organizations to complex sustainability transitions? Is there a threshold of decidedness that makes meta-organizations unready for action, either because the decisionality is too high and meta-organizations are no longer adaptable enough or because undecidability emerges? How can we identify such thresholds? Are there more facets to decidedness that we need to account for?

We believe that it would be valuable and instructive to conduct both in-depth case studies and comparative analyses to explore these questions. We can also assume that different types of domains (social movements or civil society, scientific domain, etc.) might disclose different organizational profiles, with higher multi-referentiality and weaker actorhood for instance in the case of Les Soulèvements de la Terre [the French ‘Earth Uprisings Collective’] that was administratively dissolved by the French government in June 2023 yet is still active as of February 2024. Addressing these questions through theoretical and empirical research could provide valuable insights into the operational mechanisms of meta-organizations.

While our framework was specifically designed for meta-organizations, some elements of it might still be relevant for other organizations. It would be interesting to compare and contrast individual-based organizations with meta-organizations based on the four attributes we outlined here and to see whether and how transpositions are possible and relevant.

Transition studies. We also contribute to transition research by unpacking the salient tensions that transition intermediaries are likely to face due to their organizational nature. Most of the transition research has focused on the roles and functions of transition intermediaries in the broader systemwide approach to sustainability transitions. This has led to a variety of typologies of intermediaries based on their level, stage of transition, etc. (Kanda et al. 2020; Kivimaa et al. 2019; Mignon and Kanda 2018). Here, by developing a more organizational sociology-forward perspective on the issue, we emphasize the importance of two neglected aspects: the organizational nature of intermediaries, in this case meta-organizations, and their intrinsic organizational characteristics, in this case multi-referentiality, layering of social orders, dialectical actorhood, and multi-level decidedness. However, we have not applied this analysis to the various typologies of transition intermediaries. We can reasonably assume that meta-organizations exist in all categories, but more work is needed to understand how meta-organizationality interacts with and influences the effectiveness of different types of transition intermediaries in their pursuit of directionality, diffusion, coordination and reflexivity for transformative change within sustainability transitions.

Future work might compare different cases of meta-organizations as systemic intermediaries, regime-based intermediaries, niche intermediaries, and process intermediaries, so as to investigate whether certain tensions become more salient than others depending on their organizational categories but also their sectors. For instance, intermediaries aiming to phase out fossil fuels, a sector with high regime resistance, might be particularly confronted with multi-referentiality–directionality tension and layering–diffusion tension. Further work is also needed to understand whether transformative meta-organizations need to successfully navigate all tensions or whether they only need to address a couple of them.

Here again, it would be interesting and instructive to compare multiple cases, potentially across sectors and levels of action, to get an understanding of the effects of different industries and spatial embeddedness. This paper remains fairly conceptual, and more empirical work is needed to unpack the conditions and mechanisms that govern whether meta-organizations succeed or fail to navigate the tensions. In-depth case studies as well as comparative case studies might be of value here as well. This again ties back to the question of the effectiveness of meta-organizations as transition intermediaries, and how several meta-organizations might compete for transformation.

Lastly, we contribute more generally to the literature on social change (Ciplet 2022; Köhler et al. 2019) by identifying organizational tensions that result from the nature of a transition intermediary and the underlying paradigm of changes. However, more work is needed to connect this approach with work on other related concepts, such as social movements as already advocated in previous transitions research (Hess 2018; Köhler et al. 2019). Any type of collective may face some of these tensions. Social movements, for instance, might address tensions primarily through different aspects, like power relations, disruption of existing social orders, etc. It would be instructive to systemically connect with these literatures to enrich our framework. In addition, social movements may organize in meta-organizations, as is the case for Extinction Rebellion, the Climate Justice Alliance, older associations like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, and other players like the A22 Network that gathers other social movements including Just Stop Oil in the UK, or Les Soulèvements de la Terre. These examples provide fruitful cases that could be used to analyze social movements in transition studies through a meta-organizational lens.

It would be equally instructive to compare meta-organizations to other kind of collectives of organizations. For instance, meta-organizations have been linked to ecosystems (Battisti, Agarwal, and Brem 2022), platforms (Megali 2022), and even formal networks (Corazza, Cisi, and Dumay 2021), which raises the question of how to contrast imperatives and the resulting tensions based on the type of collective and its organizational nature? What kind of key attributes, like meta-organizationality here, can we tease out, and how would these attributes conflict with or advance the imperatives of sustainability transitions?

5.2 Conclusions

Meta-organizations appear as compelling agents of transformative change, enabling to collectively tackle many of today’s biggest societal problems. Meta-organizations can fill gaps in governance and tackle problems where states, markets, organizations, and individuals may be otherwise failing. However, here we bring a more nuanced framework that consciously acknowledges how meta-organizations, just like any organization, ecosystem, network or social movement, can face tensions that need to be navigated. These tensions arise from the different demands that arise from both the imperatives of transitions and the more specific imperatives of meta-organizationality. As we navigate the challenges of sustainability transitions, transformative meta-organizations stand at the intersection of diversity and alignment, autonomy and collective purpose, and the layers of decisions that shape our shared future.

Funding source: Agence Nationale de la Recherche

Award Identifier / Grant number: ANR-22-CE26-0004

Funding source: Initiative d’Excellence d’Aix-Marseille Université AMIDEX

Award Identifier / Grant number: AMX-21-PEP-036

-

Research funding: This work received support from the ANR (ANR-22-CE26-0004) and Initiative d’Excellence d’Aix-Marseille Université AMIDEX (AMX-21-PEP-036).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

Ahrne, G., and N. Brunsson. 2005. “Organizations and Meta-organizations.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 21 (4): 429–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2005.09.005.Search in Google Scholar

Ahrne, G., and N. Brunsson. 2008. Meta-organizations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781848442658.00005Search in Google Scholar

Ahrne, G., and N. Brunsson. 2012. “How Much Do Meta-organizations Affect Their Members?” In Weltorganisationen, edited by M. Koch, 57–70. Wiesbaden: Springer.10.1007/978-3-531-18977-2_3Search in Google Scholar

Ahrne, G., and N. Brunsson. 2019. Organization Outside Organizations. The Abundance of Partial Organization in Social Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108604994Search in Google Scholar

Ahrne, G., N. Brunsson, and D. Seidl. 2016. “Resurrecting Organization by Going beyond Organizations.” European Management Journal 34 (2): 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.02.003.Search in Google Scholar

Alo, O., and A. Arslan. 2023. “Meta-organizations and Environmental Sustainability: An Overview in African Context.” International Studies of Management & Organization 53 (2): 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2023.2184119.Search in Google Scholar

Apelt, M., C. Besio, G. Corsi, V. von Groddeck, M. Grothe-Hammer, and V. Tacke. 2017. “Resurrecting Organization without Renouncing Society: A Response to Ahrne, Brunsson and Seidl.” European Management Journal 35 (1): 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2017.01.002.Search in Google Scholar

Battisti, S., N. Agarwal, and A. Brem. 2022. “Creating New Tech Entrepreneurs with Digital Platforms: Meta-organizations for Shared Value in Data-Driven Retail Ecosystems.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 175: 121392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121392.Search in Google Scholar

Berkhout, F., A. Smith, and A. Stirling. 2004. “Socio-technological Regimes and Transition Contexts.” In System Innovation and the Transition to Sustainability. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781845423421.00013Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H. 2018. “Meta-organizing Firms’ Capabilities for Sustainable Innovation: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Cleaner Production 175: 420–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.028.Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., and S. Bor. 2018. “Why Meta-organizations Matter: A Response to Lawton et al. and Spillman.” Journal of Management Inquiry 27 (2): 204–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492617712895.Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., and S. Bor. 2022. “Meta-organisation as a Partial Organisation: An Integrated Framework of Organisationality and Decisionality.” In Clusters and Sustainable Regional Development. A Meta-organisational Approach, edited by Evgeniya Lupova-Henry, and N. F. Dotti, 25–41. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003215066-4Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., N. Brunsson, M. Grothe-Hammer, M. Sundberg, and B. Valiorgue. 2022. “Meta-organizations: A Clarification and a Way Forward.” M@n@gement 25 (2): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.37725/mgmt.v25.8728.Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., M. Bucheli, and H. Dumez. 2017. “Collective CSR Strategy and the Role of Meta-Organizations : A Case Study of the Oil and Gas Industry.” Journal of Business Ethics 143 (4): 753–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3073-2.Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., L. B. Crowder, and C. M. Brooks. 2020. “Organizational Perspectives on Sustainable Ocean Governance: A Multi-Stakeholder, Meta-organization Model of Collective Action.” Marine Policy 118: 104026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104026.Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., and H. Dumez. 2016. “The Concept of Meta-organization : Issues for Management Studies.” European Management Review 13 (2): 149–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12076.Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., and M. Gadille. 2022. “Meta-organising Clusters as Agents of Transformative Change through ‘Responsible Actorhood’.” In Clusters and Sustainable Regional Development: A Meta-Organisational Approach, edited by H. Lupova-Henry, and N. F. Dotti. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003215066-6Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., and Grothe-Hammer. 2022. “From a Clash of Social Orders to a Loss of Decidability in Meta-organizations Tackling Grand Challenges: The Case of Japan Leaving the International Whaling Commission.” Organizing for Societal Grand Challenges. Research in the Sociology of Organizations 79: 115–38.10.1108/S0733-558X20220000079010Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., and A. Souchaud. 2019. “(Self-)regulation in the Sharing Economy: Governing through Partial Meta-Organizing.” Journal of Business Ethics 159 (4): 961–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04206-8.Search in Google Scholar

Berkowitz, H., and A. Souchaud. 2024. “Filling Successive Technologically-Induced Governance Gaps: Meta-organizations as Regulatory Innovation Intermediaries.” Technovation 129: 102890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102890.Search in Google Scholar

Bor, Sanne. 2014. A Theory of Meta-Organisation: An Analysis of Steering Processes in European Commission-Funded R&D ‘Network of Excellence’ Consortia. Helsinki: Hanken School of Economics. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/144154.Search in Google Scholar

Bor, S. 2019. “Understanding Accountability in the Context of Meta-organizations.” In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Conference of the British Academy of Management. Birmingham: British Academy of Management.Search in Google Scholar

Bor, S., and S. Cropper. 2023. “Extending Meta-organization Theory: A Resource-Flow Perspective.” Organization Studies 44 (12): 1939–60, https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406231185932.Search in Google Scholar

Bor, S., and G. O’Shea. 2022. “The Roles of Meta-organizations in Transitions: Evidence from Food Packaging Transition.” In Clusters and Sustainable Regional Development: A Meta-Organisational Approach, edited by E. Lupova-Henry, and N. F. Dotti, 143–59. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Bor, Sanne, Greg O’Shea, and Henri Hakala. 2024. “Scaling Sustainable Technologies by Creating Innovation Demand-Pull: Strategic Actions by Food Producers.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 198 (122941), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122941.Search in Google Scholar

Brankovic, J. 2018. “How Do Meta-organizations Affect Extra-Organizational Boundaries? The Case of University Associations.” In Towards Permeable Organizational Boundaries ? Research in the Sociology of Organizations, edited by L. Ringel, P. Hiller, and C. Zietsma, 259–82. Leeds: Emerald Publishing.10.1108/S0733-558X20180000057010Search in Google Scholar

Caniglia, G., C. Luederitz, T. von Wirth, I. Fazey, B. Martín-López, K. Hondrila, A. König, H. von Wehrden, N. A. Schäpke, M. D. Laubichler, and D. J. Lang. 2021. “A Pluralistic and Integrated Approach to Action-Oriented Knowledge for Sustainability.” Nature Sustainability 4 (2): 93–100, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00616-z.Search in Google Scholar

Carmagnac, L., and V. Carbone. 2019. “Making Supply Networks More Sustainable ‘Together’: The Role of Meta-Organisations.” Supply Chain Forum 20 (1): 56–67, https://doi.org/10.1080/16258312.2018.1554163.Search in Google Scholar

Carmagnac, L., A. Touboulic, and V. Carbone. 2022. “A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: The Ambiguous Role of Multistakeholder Meta-organisations in Sustainable Supply Chains.” M@n@gement 25: 45–63. https://doi.org/10.37725/mgmt.v25.4235.Search in Google Scholar

Chaudhury, A. S., M. J. Ventresca, T. F. Thornton, A. Helfgott, C. Sova, P. Baral, T. Rasheed, and J. Ligthart. 2016. “Emerging Meta-organisations and Adaptation to Global Climate Change: Evidence from Implementing Adaptation in Nepal, Pakistan and Ghana.” Global Environmental Change 38: 243–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.03.011.Search in Google Scholar

Ciplet, D. 2022. “Transition Coalitions: Toward a Theory of Transformative Just Transitions.” Environmental Sociology 8 (3): 315–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2022.2031512.Search in Google Scholar

Corazza, L., M. Cisi, and J. Dumay. 2021. “Formal Networks: The Influence of Social Learning in Meta-organisations from Commons Protection to Commons Governance.” Knowledge Management Research and Practice 19 (3): 303–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2019.1664270.Search in Google Scholar

Cropper, S., and S. Bor. 2018. “(Un)bounding the Meta-organization: Co-evolution and Compositional Dynamics of a Health Partnership.” Administrative Sciences 8 (3): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8030042.Search in Google Scholar

de Bakker, F. G., A. Rasche, and S. Ponte. 2019. “Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives on Sustainability : A Cross-Disciplinary Review and Research Agenda for Business Ethics.” Business Ethics Quarterly 29 (3): 343–83, https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2019.10.Search in Google Scholar