Abstract

Context

There is not much current literature looking at anxiety and depression in athletes transitioning out of college sports into the real world. This study identified gaps in the current mental health literature for former college athletes and what interventions are currently being offered to help them. By utilizing the gaps identified in the current literature, we provided recommendations for educational programs that are modeled on the programs that professional sports leagues offer while utilizing the existing college infrastructure. We also encourage future research to perform longitudinal studies following these athletes as they transition from sports.

Objectives

Collegiate sports participation is integral to culture and identity. Transitioning from athletics to regular life often leads to significant mental health concerns. Abrupt lifestyle and identity changes can result in dietary, career, and health consequences that impact athletes’ mental well-being. While some data addresses this transition, research focused on developing best practices to support athletes during this period remains limited. This study aims to conduct a systematic review to identify the existing research and gaps concerning the described supports in mental health, particularly depression and anxiety, in retired athletes.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines. We analyzed original research, literature reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical trials, and case studies. Articles were sourced from PubMed (MEDLINE), Embase, Scopus, Cochrane, and Web of Science.

Results

A total of 169 articles were identified, with 61 selected for full-text screening and nine included in the study. These nine articles comprised four cross-sectional studies analyzing survey data, four systematic or scoping reviews, and one qualitative analysis. While all articles addressed depression or anxiety, most focused on individuals returning to exercise post-injury and quality of life.

Conclusions

Current research highlights the needs of collegiate, professional, and retired athletes. Limited literature exists on former collegiate athletes, with available studies emphasizing university programs to ease transitions and help athletes apply their skills in retirement. Research gaps include examining programs across divisions and sports, minimizing self-reporting surveys, and conducting longitudinal studies. Future efforts should focus on addressing these gaps to better support athletes transitioning to life beyond sports.

The transition from collegiate sports to life beyond athletics is a critical period marked by significant changes in identity, routine, and lifestyle. For many former athletes, these changes are compounded by mental health challenges, particularly depression and anxiety, which often go unaddressed during this pivotal phase. College athletes face several unique stressors, and these factors have been shown to contribute to a higher prevalence of mental disorders in athletes when compared to the general population [1]. There is a limited amount of quantifiable research looking at the prevalence and severity of these issues in former athletes. Insight from research concerning these mental health issues in current athletes shows concerning trends. A systematic review looking at the occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former athletes found that 34 % of current athletes reported symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders. That number remained high at 26 % of retired athletes. They reported that the causes of this distress in the former athletes stemmed from injuries and chronic pain, poor retirement planning, low educational achievement, unemployment, and a lack of athletic identity [2]. A recent study showed also that the importance of gender and sport mattered when looking at the prevalence of these disorders. They concluded that female athletes and athletes in an individual sport reported feeling anxious or depressed at a higher rate than male athletes and athletes in team sports [3]. Altogether, the increased stress placed upon current athletes can induce anxiety and depressive disorders that if not better confronted, will continue to follow these athletes into their postathletic lives. Although underrepresented in research, retired collegiate athletes are a large group of athletes in the United States.

Over 520,000 student-athletes currently compete in the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA)-regulated sports across all college divisions in the United States, which has increased significantly over the past 40 years [4]. Student-athletes spend 28–33 h a week training for their sport. In addition to athletics, academics are an integral part of being a college athlete and come with their own demands and constraints. Further, other commitments to meet financial obligations may include internships, jobs, and other activities, often not leaving time for mental health or emotional support. For athletes, trying to perform at the highest personal level in each of these domains can lead to striving for perfectionism [5], which can be conducive to further mental health problems [6]. Many athletes will become defined by their athletic identity throughout their collegiate career [2], leaving a void to be filled in athletic retirement upon college graduation [2].

Losing this construct of self-identity can cause athletes to feel lost as to how they should move forward with their lives. Departing from their habitual routine of diet, exercise, and sleep, as well as the close community of their team, may lead to decreased self-worth [2]. Transitioning from athletics occurs in athletes either voluntarily or involuntarily, and it can be classified as successful or a crisis. Most voluntary retirements are associated with positive outcomes, whereas involuntary retirements are often associated with states of crisis in which athletes run into trouble in their postathletic lives. Either type of retirement can be difficult for athletes; however, research has shown that athletes who are forced to retire involuntarily can experience psychological and emotional issues, including but not limited to anxiety/depressive disorders, along with substance misuse at a higher rate than those who voluntarily retire. These athletes tend to put so much time and energy into their sport that they do not have an identity outside of it, which can give rise to these problems in their postretirement life and make them more susceptible to mental health issues [7].

Given the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in current college athletes and the complications in retired athletes, we are conducting a systematic review to identify the research gaps that exist in the mental health literature when discussing depression and anxiety that may exist in retired athletes and highlight existing interventions benefiting these athletes. With the ever-increasing participation in college athletics and the decreasing stigma around reporting mental health symptoms, this issue will become more prevalent in the coming years. Current literature suggests programs geared toward helping the student remain physically active or offering educational courses provided by the college or university. By identifying the research gaps that exist in the current interventions provided to student-athletes now to help with their transition to the real world, we can work to find solutions to help counteract the effects of these lifestyle changes.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review to investigate the breadth of literature focusing on anxiety and depression among former collegiate athletes according to the Scoping Review guidelines from the Joanna Briggs Institute [8]. To conduct this review, we performed systematic searches of five databases – PubMed (MEDLINE), Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. The search strings for each database are listed in Supplementary Material. These databases are the most comprehensive medical libraries available and relevant to the present study. Our rationale for prioritizing medical databases was based on our study’s primary focus on the prevalence of anxiety and depression in former college athletes, which aligns closely with the fields of medicine and public health. To perform these searches, a systematic review librarian constructed search strings for each database. This study did not meet the requirements for human subjects research and was not submitted for ethics review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The searches were conducted on December 11, 2023. The studies were first screened by title and abstract to include only studies that pertained to anxiety or depressive disorders in former collegiate athletes by two authors in a masked, duplicative fashion. The types of studies included were original research articles including letters and briefs, literature reviews, systematic reviews or meta-analyses, clinical trials, and case studies. We excluded conference posters or presentations, commentaries, and editorials. The studies were also limited to those published in English within the last 10 years.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by two authors – also in a masked, duplicative fashion. After the extraction was completed, the author reconciled data to reach 100 % inter-rater agreement. In instances when agreement between the two extractors (M.R. and B.E.) could not be reached, a third author (M.H.) acted as an arbiter. Data extracted from the studies included author, year of publication, title, location (country/state), journal, type of article, type of research, sport, age of participants, sex, enrollment, intervention, type of mental health disorder, symptomology, and duration of symptoms.

Results

Search strategy results

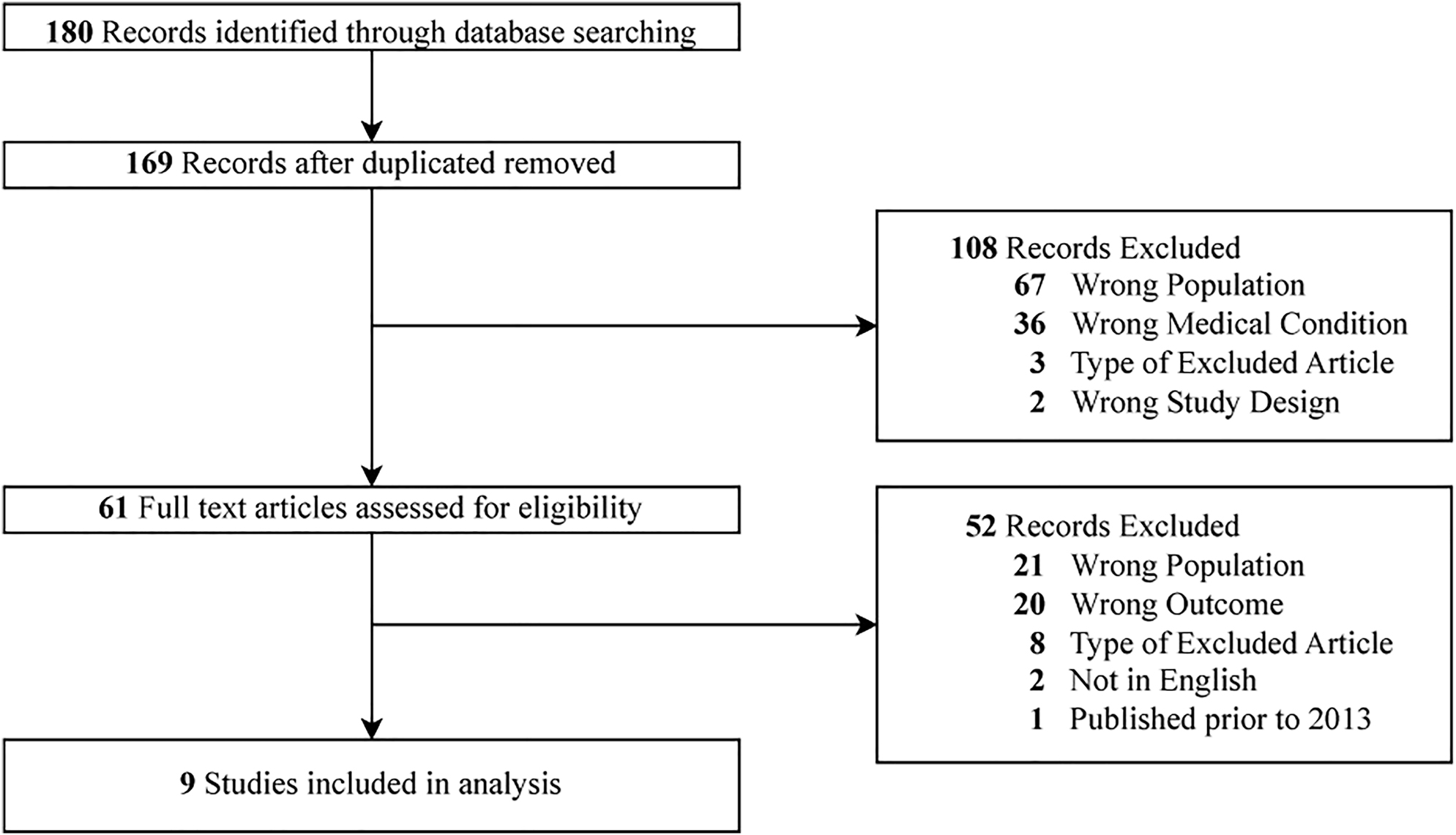

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Figure 1) shows the search string results for our scoping review. There was a total of 180 articles from PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library. After duplicates were removed, there were 169 articles left for screening. These articles were screened by both title and abstract for the inclusion criteria. We determined that 61 articles fit our criteria and were selected for full-text analysis. The articles not selected were excluded because they reported on the wrong target population or medical condition, had an excluded study design, or were a type of predetermined excluded article. From the 61 full-screen articles, an additional 52 were further excluded. These 52 articles were excluded for the following reasons: 21 had the wrong target population, 20 had the wrong medical condition, eight were a type of excluded article, two were not in English, and one was published 27 years ago. Therefore, a total of nine articles were included in this scoping review.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) diagram for article inclusion in this review.

Article analysis

Two authors reviewed all nine included articles. The details of each article including author, publication year, type of research, sport, age of participants, sex, intervention, enrollment, and symptoms for each article are presented in Table 1. The included studies consisted of cross-sectional surveys, systematic/scoping reviews, literature reviews, and qualitative research. Most articles involved multiple sports. All included articles mentioned anxiety and/or depression in regard to former collegiate athletes. An interventional tool was analyzed in each article, and the most common type of intervention was staying active after retirement (n=4) followed by educational approaches for the transitioning athlete (n=2). Other interventional strategies observed were mental health screening before retirement (n=1), maintaining social groups (n=1), and having physicians be aware of athlete-specific determinants of anxiety symptoms (n=1).

Studies included in the scoping review analysis and article characteristics.

| Study, year | Type of research | Sport | Age of participants, years | Sex | Intervention | Enrollment | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrara et al. 2023 [9] | Qualitative research | Multiple | 22–26 | All | Cognitive-behavioral strategies to maintain exercise | 17 former division I athletes | NA |

| Moore et al. 2022 [10] | Systematic review | Multiple | 18–28 | All | Social support/education for managing post-athletic transition | 17 former division I and II athletes | Loss of identity and social isolation |

| Shander and Petrie 2021 [11] | Cross-sectional design/survey | Swimming, gymnastics | 26 | Females | Staying active, post-sports | 217 former division I female swimmers and gymnasts | Lack of interest in life |

| Rice et al. 2019 [12] | Systematic review | Multiple | NA | All | Be aware of athlete-specific determinants of anxiety symptoms | 61 articles total, 27 of which were suitable for meta-analysis | NA |

| Voorheis et al. 2023 [13] | Scoping review | Multiple | NA | All | Nonathletic career counseling | NA | NA |

| Haslam et al. 2021 [14] | Cross-sectional design/survey | Multiple | 16-48 (average, 28) | All | Maintained/gained social groups | Chinese sample was 183, western countries was 94 | NA |

| Ling et al. 2023 [15] | Cross-sectional design/survey | Soccer | NA | Females | Continued participation in sports/exercise | 560 retired college or professional women’s soccer players | NA |

| Dimitriadou et al. 2022 [16] | Cross-sectional design/survey | Artistic, rhythmic, and acrobatic gymnastics | 20–59 | All | Exercise | 114 former gymnasts | NA |

| Montero et al. 2022 [7] | Literature review | NA | NA | All | Mental health screening | NA | NA |

-

NA, not applicable.

Ferrara et al

A study published in 2023 explored former NCAA Division I college athletes’ experiences with physical activity after retiring from their college sport. They identified three domains that affected a former college athlete’s physical activity postsport. Domain I included transitional lifestyle shifts (postsport break, loss of the team, shifting perceptions of healthy physical activity) that affected physical activity. Domain II described possible barriers (negative athletic experiences, monetary cost, resource quality/availability, lack of time, and physical limitations) that affected physical activity. Domain III described enablers (enjoyment, familiarity, staying healthy, mood-enhancing atmosphere, and an inclusive/motivating community) that promoted physical activity. By taking these concerns into account, this study employed cognitive behavioral strategies that enhanced collegiate athlete performance and in other adult populations [9].

Shander and Petrie

A study published in 2021 looked at the association between psychosocial aspects of sports transition with body satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and life satisfaction in former NCAA athletes. Their research showed that athletes who focused on something other than their sport while they participated in it and those who remained active in the sport in some capacity after retirement tended to be more satisfied with their lives. Both groups displayed fewer depressive symptoms as well [11].

Ling et al

A study published in 2023 investigated the risks and benefits of elite soccer athletes in five health domains, including mental health. For the mental health screening, athletes were given a survey that asked them questions about their mental health and screened for anxiety and depression. The results found that the longer the athlete had been retired, the less anxiety and depressive symptoms they had. The article suggested that staying active and involved in physical activity alleviated these symptoms. The article suggested that there needed to be better counseling for younger athletes who have or are actively transitioning out of their sports [15].

Dimitriadou et al

A study was published in 2022 that assessed the quality of life, anxiety, and depression levels in former gymnasts and nonathletes. Their study found that the former gymnasts had lower levels of anxiety and depression than the nonathlete group and a better quality of life. Within the retired gymnasts, they found that those who were still physically active tended to have lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to their peers who led more of a sedentary lifestyle [16].

Moore et al

A systematic review published in 2022 reported on three different studies. One of the studies looked at former NCAA Division I and II athletes who experienced a season- or career-ending injury. They interviewed those athletes about their career transitions and experiences with career-ending injuries. The researchers concluded that these athletes usually faced not only physical complications but also psychosocial challenges, which resulted in emotional and behavioral reactions for these athletes, such as feeling hopeless and having a sense of lack of control over their lives. They encouraged athletes to maintain social support groups and receive postathletic career counseling [10], 17].

Voorheis et al

A scoping review published in 2023 reviewed academic literature that addressed athletes’ experience while transitioning to life postsports. It aimed to identify how athletes can be supported through this process as well as possible barriers that could lead to a challenging postsport transition. A total of 8 reviews demonstrated a relationship between athletic retirement and mental health outcomes. Most of them found a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression in retired athletes compared to the general population. To help counteract this, they suggested introducing athletes to nonathletic career counseling before retirement [13].

Montero et al

A literature review published in 2022 aimed to present the current literature on sleep and mental health disorders. The article pointed out how athletes, specifically those who retire involuntarily, suffered from mental health issues. They also pointed out that there were not a lot of studies comparing current and former athletes’ mental health, nor was there a consistent way to compare the two. Overall, the article acknowledged that this was a growing issue and that more mental health screening was needed to better understand the true number of athletes affected [7].

Haslam et al

A study published in 2021 looked at how higher levels of competitive sports impact certain variables that play a critical role in retirement adjustment. Retired athletes from Western and Eastern regions were given a survey that evaluated athletic identity, social group memberships, and adjustment. In both groups, the loss of athletic identity had negative effects on postsport transition. However, it also showed that maintaining or gaining social groups could negate the negative effects of losing one’s athletic identity [14].

Rice et al

A systematic review published in 2019 looked to identify, quantify, and analyze determinants of anxiety symptoms experienced by elite athletes. This review looked at studies from multiple countries. Results showed an increased level of anxiety in female athletes and those who took part in individual sports. The article called for sports medicine practitioners to look for athlete-specific factors, career dissatisfaction, and musculoskeletal injury as potential factors that could influence mental health as a way to plan for postsport transition for the athlete [12].

Discussion

The current study focused on identifying studies that provide insight into supporting or minimizing risks of depression and/or anxiety in retired college athletes. Although the search string utilized in our study was designed to cast a broad net and capture an abundance of literature, after the screening, only 9 articles met the inclusion criteria, with research being largely inconsistent about the applied interventions. While every year thousands of US college athletes retire, this staggering lack of research indicates how little has been done to support this group of individuals during or after their retirement. Moreover, his lack of available research demonstrates the need for additional studies regarding mental health postathletic retirement. As such, the main and foremost conclusion of this study is a call for a systematic effort to better understand how to better support this population, with particular emphasis on the prevention of depression and anxiety.

Among the identified articles, there was a lack of consistency regarding intervention type – most of which focused on staying active after retirement from competitive sport [9], 11], 15], 16]. However, several themes emerged in our search, including coaching the athletes to develop a goal-oriented and active lifestyle. Ferrara et al. [9] suggested that athletic personnel (coaches and athletic trainers) encourage athletes to analyze how they think about improving their performance during college athletics to help maintain the same mentality postcollege. These included goal-setting, finding a type of physical activity the athlete enjoyed doing, finding a workout place that feels comfortable and has the necessary resources, and many more behavioral mentalities [9]. The other articles that mentioned remaining physically active postretirement as the best intervention to preventing anxiety and depressive disorders in former college athletes echoed similar thoughts [11], 15], 16].

The second most popular intervention type among the nine articles was the completion of educational courses for transitioning college athletes regarding their adjustment to the real world [10], 13]. Moore et al. [10] encouraged athletes to “find a larger sense of purpose that drives them to improve as an individual” and to find their social networks outside of sports. Overall, the authors stressed the importance of athletes proactively developing strategies for postcollege transition – utilizing resources provided by the college in the form of mental health counselors, lifestyle coaches, educational materials, and individualized mentorship [10]. Voorheis et al. [13] support the same type of programs mentioned in the Moore et al. [10] article; both believe it is important to help the transitioning athlete apply their unique skills learned through sports to their new life [13]. Beyond this theme, the remaining articles mentioned that obtaining mental health screening should be a routine part of collegiate athletics to identify early signs of anxiety and depressive disorders [7], and to make appropriate referrals to medical professionals [12].

Identified gaps in mental health research for former collegiate athletes

Our review also analyzes gaps listed in each article. Gaps identified in the selected articles encouraged future research to look at all divisions of semi-professional sports [9] and to compare how varying sports affect athletes differently [13]. Others pointed out that further research needs to be done without utilizing self-reporting surveys to eliminate bias or misunderstanding of symptoms [12]. None of the articles that utilized surveys to collect data followed up with the athlete after the initial survey. Shander and Petrie [11] pointed out the lack of longitudinal studies on athletes transitioning out of sport, which this review agrees with, especially for our target population. Most of the selected articles mentioned that future studies should include the effect of interventions or pretransition planning on this group of athletes [9], 12], 13].

Where these limitations are present in our target population, professional sports leagues in the United States can combat them. The National Football League (NFL) has programs in place through the Players Association (NFLPA) that allow athletes to access career-advising services and career counseling [18]. They have also started a program called AthleteAnd, which offers a variety of services to the players to grow their lives “outside the locker room [19].” Major League Baseball (MLB), the National Hockey League (NHL), and Major League Soccer (MLS) offer similar programs to their athletes. The NHL Players Association offers a mental health training course specifically designed to address issues faced by players and their families [20], whereas MLS offers players the chance to shadow the league office for a day to learn more about the business side of soccer [21]. Whereas these professional leagues have a multitude of money and resources compared to colleges, it would still be possible for colleges and universities to offer similar programs through existing resources through career development offices, student success, and athletic departments.

Implications and recommendations

The findings of this scoping review reveal important implications for both the understanding and treatment of mental health issues among college athletes, particularly during their transition into postathletic life. While a substantial body of research highlights high rates of anxiety and depression among professional athletes, particularly in leagues like the NFL [22], it is likely that similar mental health challenges are prevalent among competitive athletes at lower levels. Moreover, many existing studies focus predominantly on male professional athletes [23]. Studies included in our review show that the intense demands placed on student-athletes – balancing academics, athletic performance, and financial responsibilities – create an environment conducive to mental health disorders among all genders [23]. Among any athlete, however, the physical demands of the sport and related lifestyle changes, as well as the loss of athletic identity and the transition into retirement, especially involuntarily, can exacerbate mental health issues [23].

Given the disparity in funding for professional sports and college athletics, we support the recommendations and strategies put forth by Moore et al. and Voorheis et al., in utilizing existing infrastructure for mental health support at the collegiate level. This could be a collaborative effort across multiple sports at each institution to spread the costs associated with employing mental health professionals, conducting screenings, and making referrals when the need arises. Additionally, Voorheis et al., proposed a four-step framework to help athletes transition away from athletics to reduce the impact of retirement on mental health. These steps included: 1) preparation for retirement – seeing retirement as a transition rather than an ending; 2) curating self-identity – understanding strengths and identifying transferable skills; 3) gaining control of the process – preparing to adjust to a life without sports through shifting time management, being aware of grief, vocational planning, establishing a social support network, maintaining physical activity, and thinking about how to make money outside of sports; and 4) normalizing the transition – including former athletes, coaches, and mental health providers in sport in the process can show that all athletes can move into postsports life in a positive, effective way [13]. Given the long-term mental health impact on former athletes, the NCAA should consider requiring colleges to implement an exit training module as part of graduation or before the next semester for nongraduating athletes. This training module should include elements to support the eight dimensions of wellness – physical, intellectual, emotional, social, spiritual, vocational, financial, and environmental [24]. Schools could have their exercise science or kinesiology departments create workouts that are shorter and suited for public gym use available for download within the module. Nursing or dietitian programs could provide a brief overview of nutritional requirements and caloric intake for nonathletes. If athletes wish to continue their education postgraduation, the module could provide resources to potential programs that fit their skill set through continuing education programs on campus. The college or university’s career services department could provide something similar to the NFL program mentioned above that links athletes with potential career paths that fit their unique skills. All students are required to complete an exit counseling through Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) when they graduate or drop below full-time enrollment. However, the financial services department at schools could provide additional counseling to athletes including how to manage Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) funds as well as budgeting for food and other necessities. The community outreach and involvement departments could provide links to social groups – churches, adult sports leagues, etc – within the community so athletes could start to build their social networks outside of school. Finally, mental health screenings evaluated by the school’s mental health provider and the athletic training department can identify athletes at an increased risk for anxiety and depressive disorders and provide them with the resources they need for their transition. Overall, this transition module would require multi-departmental cooperation in order to best benefit the transitioning athlete.

Furthermore, we recommend that more research needs to be conducted in this field of study so that athletes can have access to the best resources during this transition time. Given that the included articles do not mention changes in the athletes’ relationships or dietary, career, and health changes, future studies should focus on these aspects of the postcollege athletic transition. Utilizing the increased research, the addition or expansion of educational courses could be implemented across all collegiate athletic departments, which would greatly benefit athletes during this transition period.

Strengths and limitations

A notable strength of the current review was that we searched the five largest databases to include a wide range of literature specific to anxiety and depression as medical conditions among athletes. While this allowed for an accurate depiction of the currently available medical research, literature that was not available through these databases may limit our findings, as databases emphasizing psychological research may yield research on other aspects of athlete mental health, particularly regarding psychosocial factors and career transition experiences. Additionally, the use of three reviewers optimized the selection process. A notable limitation of this study resulted from the use of articles only written in English within the last 10 years – possibly excluding articles that could have been beneficial to the study. Additionally, we did not search grey literature, nor clinical trial registries to retrieve nonpublished items.

Conclusions

This systematic review provided a summary of the current literature related to the prevalence of anxiety and depression in former college athletes. The majority of articles mentioned that remaining physically active after college mitigates these disorders. Gaps we identified in the literature include the use of educational programs and resources available for these student-athletes to help with that transition. The use of the existing collegiate infrastructure and personnel to address mental health screening and needs may be a viable option to pool resources, compared to professional sports, where available funds are often more abundant. Given the limited number of included articles, we also note that there is a critical need for further research regarding mental health in this population.

-

Research ethics: This study does not meet the criteria for human subjects research by the Oklahoma State University Institutional Review Board, and was not submitted for ethics review. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors are directly involved with the program under study. Dr. Hartwell has received research funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U54HD113173), Human Resources Services Administration (U4AMC44250-01-02 and R41MC45951), and from the National Institute of Justice (2020-R2-CX-0014).

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Rice, SM, Purcell, R, De Silva, S, Mawren, D, McGorry, PD, Parker, AG. The mental health of elite athletes: a narrative systematic review. Sports Med 2016;46:1333–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Gouttebarge, V, Castaldelli-Maia, JM, Gorczynski, P, Hainline, B, Hitchcock, ME, Kerkhoffs, GM, et al.. Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:700–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100671.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Sanfilippo, JL, Haralsdottir, K, Watson, AM. Anxiety and depression prevalence in incoming division I collegiate athletes from 2017 to 2021. Sport Health 2023:19417381231198537.10.1177/19417381231198537Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. NCAA Sports Sponsorship and Participation Rates Report. Indianapolis, IN: National Collegiate Athletic Association; 2022.Search in Google Scholar

5. Stoeber, J. Theppsychology of perfectionism: theory, research, applications. New York, NY: Routledge; 2017.10.4324/9781315536255Search in Google Scholar

6. Sirois, FM, Molnar, DS. Perfectionism, health, and well-being. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2015.10.1007/978-3-319-18582-8Search in Google Scholar

7. Montero, A, Stevens, D, Adams, R, Drummond, M. Sleep and mental health issues in current and former athletes: a mini review. Front Psychol 2022;13:868614. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.868614.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Peters, MDJ, Marnie, C, Tricco, AC, Pollock, D, Munn, Z, Alexander, L, et al.. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement 2021;19:3–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/xeb.0000000000000277.Search in Google Scholar

9. Ferrara, PMM, Zakrajsek, RA, Eckenrod, MR, Beaumont, CT, Strohacker, K. Exploring former NCAA Division I college athletes’ experiences with post-sport physical activity: a qualitative approach. J Appl Sport Psychol 2023;35:244–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.1996482.Search in Google Scholar

10. Moore, HS, Walton, SR, Eckenrod, MR, Kossman, MK. Biopsychosocial experiences of elite athletes retiring from sport for career-ending injuries: a critically appraised topic. J Sport Rehabil 2022;31:1095–9. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2021-0434.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Shander, K, Petrie, T. Transitioning from sport: life satisfaction, depressive symptomatology, and body satisfaction among retired female collegiate athletes. Psychol Sport Exerc 2021;57:102045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102045.Search in Google Scholar

12. Rice, SM, Gwyther, K, Santesteban-Echarri, O, Baron, D, Gorczynski, P, Gouttebarge, V, et al.. Determinants of anxiety in elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:722–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100620.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Voorheis, P, Silver, M, Consonni, J. Adaptation to life after sport for retired athletes: a scoping review of existing reviews and programs. PLoS One 2023;18:e0291683. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291683.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Haslam, C, Lam, BCP, Yang, J, Steffens, NK, Haslam, SA, Cruwys, T, et al.. When the final whistle blows: social identity pathways support mental health and life satisfaction after retirement from competitive sport. Psychol Sport Exerc 2021;57:102049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102049.Search in Google Scholar

15. Ling, DI, Hannafin, JA, Prather, H, Skolnik, H, Chiaia, TA, de Mille, P, et al.. The women’s soccer health study: from head to toe. Sports Med 2023;53:2001–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01860-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Dimitriadou, K, Dallas, C, Papouliakos, S, Dallas, G. Quality of life, level of anxiety and level of depression among former artistic gymnasts, former gymnasts from other sports and non-athletes. Sci Gymnast J 2022;14:391–9. https://doi.org/10.52165/sgj.14.3.391-399.Search in Google Scholar

17. Moore, MA, Vann, S, Blake, A. Learning from the experiences of collegiate athletes living through a season- or career-ending injury. J Amat Sport 2021;7. https://doi.org/10.17161/jas.v7i1.14501.Search in Google Scholar

18. Career Development. NFL players association. https://nflpa.com/active-players/career-development [Accessed 9 November 2024].Search in Google Scholar

19. #AthleteAnd. NFL players association. https://nflpa.com/athleteand [Accessed 9 November 2024].Search in Google Scholar

20. First line. https://www.nhlpa.com/the-pa/pa-programs-and-partnerships/first-line [Accessed 9 November 2024].Search in Google Scholar

21. Player Engagement. Mlssoccer. https://www.mlssoccer.com/playerengagement/resources [Accessed 9 November 2024].Search in Google Scholar

22. DeFreese, JD, Walton, SR, Kerr, ZY, Brett, BL, Chandran, A, Mannix, R, et al.. Transition-related psychosocial factors and mental health outcomes in former National Football League players: an NFL-LONG study. J Sport Exerc Psychol 2022;44:169–76. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2021-0218.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Irandoust, K, Taheri, M, Chtourou, H, Nikolaidis, PT, Rosemann, T, Knechtle, B. Effect of time-of-day-exercise in group settings on level of mood and depression of former elite male athletes. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2019;16:3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193541.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Stoewen, D. Dimensions of wellness: change your habits, change your life. Can Vet J 2017;58:861–2.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2025-0008).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.