The assessment of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in residency: the benefits of a four-year longitudinally integrated curriculum

-

Duc Q. Le

Abstract

Context

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has diverse applications across various clinical specialties, serving as an adjunct to clinical findings and as a tool for increasing the quality of patient care. Owing to its multifunctionality, a growing number of medical schools are increasingly incorporating POCUS training into their curriculum, some offering hands-on training during the first 2 years of didactics and others utilizing a longitudinal exposure model integrated into all 4 years of medical school education. Midwestern University Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine (MWU-AZCOM) adopted a 4-year longitudinal approach to include POCUS education in 2017. There is a small body of published research supporting this educational model, but there is not much data regarding how this approach with ultrasound curriculum translates to real-world changes in POCUS use by graduate student clinicians having received this model of education.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are to determine the frequency of POCUS use by MWU-AZCOM graduates and to assess how a 4-year longitudinal ultrasound curriculum may enhance the abilities of MWU-AZCOM graduates to perform and interpret ultrasound imaging in specific residency programs.

Methods

The study was approved by the MWU Institutional Review Board (#IRBAZ-5169, approval date October 3, 2022). An anonymous novel 12-question survey was conducted utilizing Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure online platform, and distributed to MWU-AZCOM 2021 and 2022 graduates via email. Survey questions were aimed at assessing frequency of use, utilization of different imaging modalities, reasons for utilizing POCUS, barriers/enablers to utilizing POCUS, ultrasound training, and confidence in performing scans and interpreting POCUS imaging. All of the 104 surveys returned were included in the study. Statistical software R version 4.3 was utilized to conduct statistical analyses.

Results

Of the 484 surveys distributed, 104 were completed (21.5 % response rate). Responses came from residents working in 14 different specialties, 50 in primary care and 54 in nonprimary care. Of all respondents, 85.6 % currently utilize POCUS in their practice on at least a monthly basis and 77.0 % believe that their POCUS training in medical school enriches their current practice in residency. The top five modalities utilized by residents were procedures (89.9 %), cardiac (88.8 %), pulmonary (82.0 %), Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST, 73.0 %), and vascular (71.9 %). Respondents recognized POCUS as a beneficial diagnostic tool (97.8 %) and reported enhancements in physical examination skills (58.4 %) and professional growth (61.8 %). Facilitators for POCUS adoption included cost-effectiveness (82.0 %), diagnostic differentiation (78.7 %), and safety (79.8 %). Barriers included a lack of trained faculty (27.9 %), absence of necessary equipment (26.9 %), and cost of equipment (22.1 %). Participants demonstrated high confidence levels in performing (74.0 %) and interpreting (76.0 %) POCUS, with 43.3 % believing that their POCUS training enhanced their attractiveness as residency candidates.

Conclusions

This study supports the positive impact of a 4-year longitudinal POCUS curriculum on graduates’ practice. It emphasizes the link between MWU-AZCOM’s curriculum and real-world clinical needs. Addressing identified barriers and advancing hands-on training can further enhance POCUS understanding, ensuring that future physicians are well-prepared to leverage its diagnostic potential across medical specialties.

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has emerged as an invaluable tool for clinicians to rapidly facilitate diagnoses and optimize medical decision-making [1]. POCUS is increasingly being utilized by clinicians across various specialties because it provides a safe, portable, and noninvasive method to enhance detection of medical problems at a reasonable cost [2]. With its rapid integration into healthcare, POCUS training is becoming an important aspect of medical school education. Showcasing its importance, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2023 mandated guidelines for the establishment, implementation, and management of ultrasound training within family medicine residency programs for accreditation [3].

The affordability and versatility of POCUS are prompting its accelerated incorporation into the first two didactic years and even a complete integration into the traditional 4-year medical school curricula across the United States [4], [5], [6]. Studies from both allopathic and osteopathic medical schools have proposed comprehensive 4-year ultrasound curricula with similar objectives of familiarizing their students with this evolving technology and its clinical applications [7], 8]. These studies support integration of ultrasound training into early medical education to augment learning of anatomy, physiology, and clinical medicine.

Other medical schools present the idea that early ultrasound exposure is established to enhance understanding of anatomy and physical examination skills [9]. A survey of 146 first-year medical students at AZCOM found that integrating ultrasound workshops into didactic courses significantly improved their comprehension of anatomy (87.0 %) and clinical applications (91.0 %) [10]. Additionally, a study of Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine students revealed ultrasound’s perceived benefit comparable to peer-to-peer teaching [11]. Beyond improved anatomical competence, a position paper highlighted the positive impact of POCUS on comprehension in areas beyond anatomy, including physiology and pathology [12]. It is demonstrated that brief POCUS instruction, such as the assessment of ascites and hepatomegaly, can be as effectively learned as the physical examination but with greater student-perceived utility [13].

Evidence exists to suggest that the knowledge and practical skill of residents is also enhanced by POCUS education. It was demonstrated that a longitudinal POCUS curriculum within residency programs, specifically for a minimum of 6 months, increases residents’ ultrasound usage and is associated with increased comprehensive ultrasound knowledge (60.9–70.2 %), image acquisition skills, interpretation, and even psychomotor skills [14]. Additionally, early POCUS exposure allows junior general surgery residents to significantly improve their ultrasound performance after the completion of training modules compared to their senior residents [15]. Furthermore, it is shown that acute care physicians suggest that earlier and more frequent exposure to POCUS education and training increased POCUS utilization in acute care settings [16].

Although POCUS education and its implications in medical education and residency have been well studied, research aimed at identifying preclinical POCUS medical education and its effects in residency is limited. This current study augments the existing literature concerning the applications of POCUS within medical school curricula. Our focus here is to bridge the missing gap between preclinical education and residency. We aim to assess the effects of implementation of a 4-year longitudinally integrated POCUS curriculum during medical school on graduates’ confidence in ultrasound and their competence while in residency. The conclusions drawn from this study will help further galvanize the significance of POCUS training in medical education and improve the application of POCUS during this training period.

Methods

Survey development

A novel 12-question questionnaire on POCUS use was developed. The study was approved by the Midwestern University (MWU) Institutional Review Board (#IRBAZ-5169, approval date October 3, 2022). Per MWU Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines, informed consent was obtained from all participants by each participant voluntarily completing the questionnaire. The survey was implemented via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure online platform for the creation and management of surveys and databases. Questions in the survey were aimed at assessing POCUS use in the following areas: the imaging modalities utilized, reasons for use, barriers against use, enablers for use, medical school preparation, confidence in performing POCUS and evaluating images, how attractive ultrasound training has made the participant for residency, and how well the medical school’s ultrasound training aligns with the participant’s current practice. Participants were also asked to provide their clinical specialty and any thoughts regarding improvement in their school’s ultrasound curriculum or additional comments regarding POCUS use. A Likert scale was utilized for questions regarding the participants’ assessment of confidence in performing POCUS examinations and confidence in evaluating POCUS imaging. We assessed perceptions of how their medical school’s ultrasound training benefits and aligns with their current practice and how attractive it made them as an applicant for residency (from strongly agree to strongly disagree). Surveys were emailed to participants for 4 consecutive weeks from October 11 to October 31, 2022 (surveying AZCOM 2021 graduates), and again from October 9 to October 30, 2023 (surveying AZCOM 2022 graduates). The exact survey sent to participants is available as Supplementary Material.

Participants

This voluntary, anonymous survey was distributed via email to MWU-AZCOM graduates of 2021 and 2022, who were current PGY-2s at the time of the survey, across various clinical specialties. Per the MWU IRB guidelines, informed consent was expressed by those who chose to fill out the survey. For the 2022 cycle, the survey was sent to 247 participants, and 68 responses were obtained. For the 2023 cycle, the survey was sent to 237 participants, and 36 responses were obtained. The survey responses were all fully completed. No participants’ responses were removed from the analysis, and a total of 104 responses (21.5 % response rate) were included in the study analysis.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative responses from the survey were analyzed for each question, and qualitative responses were provided in a table. Descriptive statistics in terms of counts and percentages were utilized to summarize categorical question responses. Graphs were also created to look at categorical responses to three questions to see the distribution of responses. All statistical analyses were conducted utilizing the statistical software R version 4.3. The data were assessed by the members of the study group and a biostatistician from the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs at MWU.

Results

The study encompassed a total of 104 participants that were divided between primary care (N=50, 48.1 %) and other medical specialties (N=54, 51.9 %). Primary care specialties, as designated by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), include internal medicine, family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology (OBGYN), pediatrics, and psychiatry. Responses from residents in a total of 14 different clinical specialties were obtained: pathology (n=1, <1.0 %), anesthesiology (n=9, 9.0 %), emergency medicine (n=20, 19.2 %), family medicine (n=18, 17.0 %), general surgery (n=10, 10.0 %), internal medicine (n=23, 22.0 %), neurology (n=4, 4.0 %), OBGYN (n=3, 3.0 %), ophthalmology (n=1, <1.0 %), orthopedic surgery (n=1, <1.0 %), pediatrics (n=3, 3.0 %), physical medicine and rehabilitation (n=6, 6.0 %), psychiatry (n=3, 3.0 %), and radiology (n=2, 2.0 %). A subset of respondents, approximately 14 % (n=15, 14.4 %), indicated nonutilization of POCUS during their residency programs. However, most respondents (n=89, 85.6 %) confirmed the utilization of POCUS in their clinical practice, occurring at varying frequencies: daily (n=28, 31.5 %), weekly (n=39, 43.8 %), and monthly (n=22, 24.7 %).

A specific inquiry within the survey aimed to ascertain the most extensively employed imaging modalities during residency training from a selection of 10 options: pulmonary, cardiac, abdominal Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST), musculoskeletal, procedures, ocular, thyroid, OBGYN, vascular/deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and dermatology-related. Results demonstrated that the top five modalities widely utilized across diverse specialties by residents are procedures (n=80, 89.9 %), cardiac (n=79, 88.8 %), pulmonary (n=73, 82.0 %), FAST (n=65, 73.0 %), and vascular (n=64, 71.9 %).

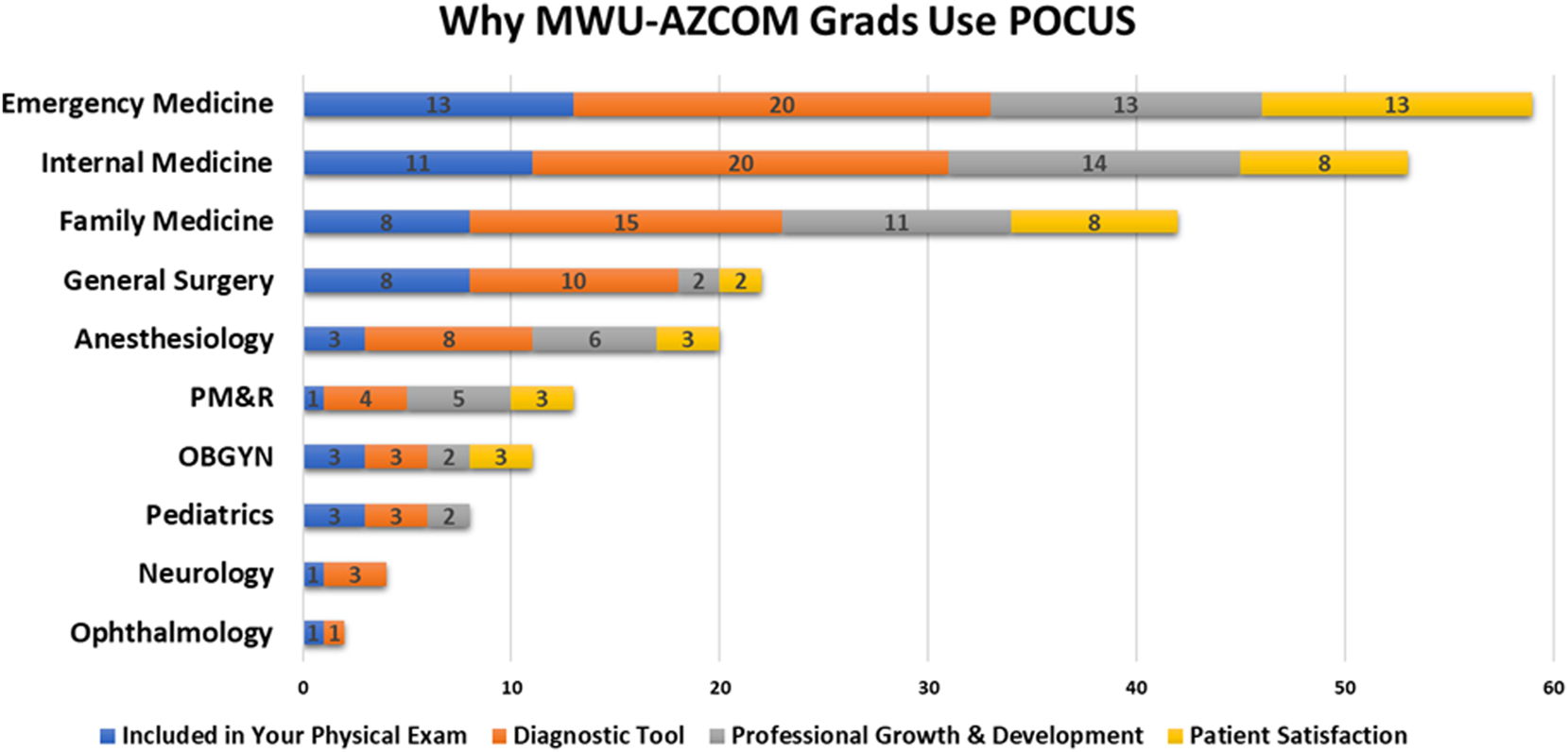

The survey also delved into why respondents incorporate POCUS into their practice. Among the 89 respondents who regularly utilize POCUS, 97.8 % (n=87) regarded POCUS as a beneficial diagnostic tool. Additionally, 52 respondents (58.4 %) recognized its role in enhancing their physical examination skills, and 55 respondents (61.8 %) believe that POCUS use contributes to their professional growth. Similarly, 40 respondents (44.9 %) reported utilizing POCUS to improve patient satisfaction. We chose to further dissect these responses by residency specialty to gain insight into specific POCUS uses of various specialties. Specialties commonly reporting POCUS as enhancing their physical examination skills include emergency medicine (n=13, 13.0 %), internal medicine (n=11, 11.0 %), family medicine (n=8, 8.0 %), and general surgery (n=8, 8.0 %). Specialties commonly reporting utilizing POCUS as a diagnostic tool include emergency medicine (n=20, 19.0 %), internal medicine (n=20, 19.0 %), family medicine (n=15, 14.0 %), and general surgery (n=10, 10.0 %). Specialties reporting POCUS use for professional growth and development include internal medicine (n=14, 14.0 %), emergency medicine (n=13, 13.0 %), and family medicine (n=11, 11.0 %). Specialties reporting POCUS use to increase patient satisfaction include emergency medicine (n=13, 13.0 %), internal medicine (n=8, 8.0 %), and family medicine (n=8, 8.0 %). This residency-specific data breakdown is represented in Figure 1.

A specialty-specific breakdown of the reasons why MWU-AZCOM graduates utilize POCUS in their practice. Residents in emergency medicine, internal medicine, and family medicine comprise most POCUS users.

The survey also aimed to highlight factors facilitating the utilization of POCUS during residency training and offered respondents options including cost-effectiveness, diagnostic differentiation, ease of use, expedited patient care, meeting residency accreditation standards, safety, and a potential no-enablers option. Notably, respondents identified key factors enabling POCUS use, with cost-effectiveness (n=73, 82.0 %), diagnostic differentiation (n=70, 78.7 %), and safety (n=71, 79.8 %) being the most prominent. Other enabling factors included ease of use (n=64, 71.9 %), expediting patient care (n=65, 73.0 %), and meeting residency accreditation standards (n=35, 39.3 %).

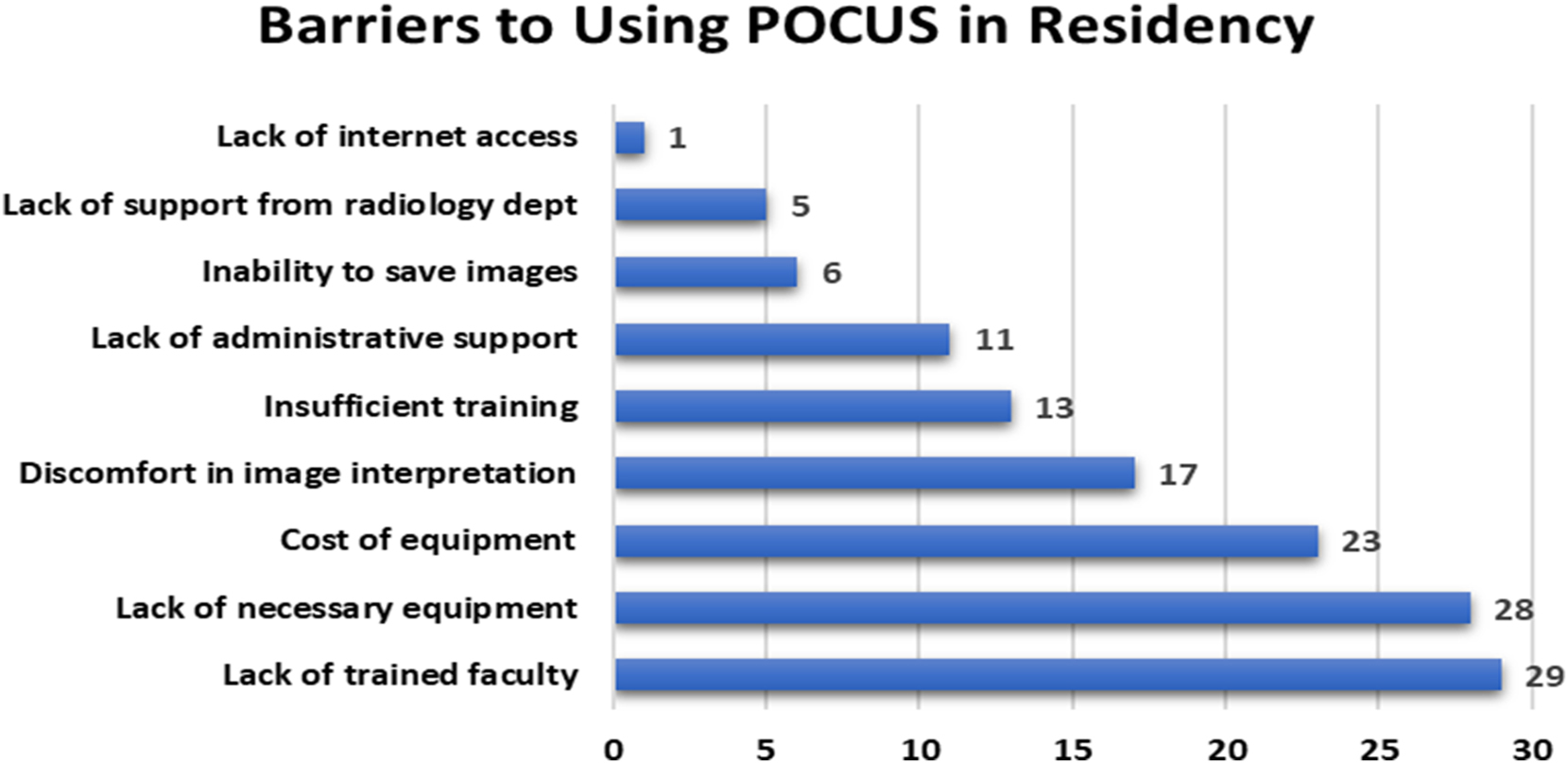

Equally significant was the identification of barriers hindering regular POCUS utilization within residency programs. All 104 participants were presented with 10 potential barriers, and the commonly indicated barriers included the lack of trained faculty (n=29, 27.9 %), absence of necessary equipment (n=28, 26.9 %), and cost of equipment (n=23, 22.1 %). Additional barriers included discomfort with image interpretation (n=17, 16.3 %), insufficient training (n=13, 12.5 %), lack of administrative support (n=11, 10.6 %), lack of support from the radiology department (n=5, 4.8 %), image acquisition issues (n=6, 5.8 %), and lack of internet access (n=1, 1.0 %). These data are visually expressed in Figure 2. Further evaluation of the data indicated that specialties citing a lack of training in residency as a barrier (n=13, 12.5 %) included internal medicine (n=5, 38.4 %), family medicine (n=4, 30.8 %), and anesthesiology (n=4, 30.8 %). Common specialties citing a lack of trained faculty (n=23, 27.9 %) at their respective programs were family medicine (n=10, 34.5 %), internal medicine (n=9, 31.0 %), and emergency medicine (n=4, 13.8 %).

MWU-AZCOM graduates commonly report a lack of trained faculty, a lack of necessary equipment, and the cost of equipment as the most prohibitive factors against POCUS use within their residency programs.

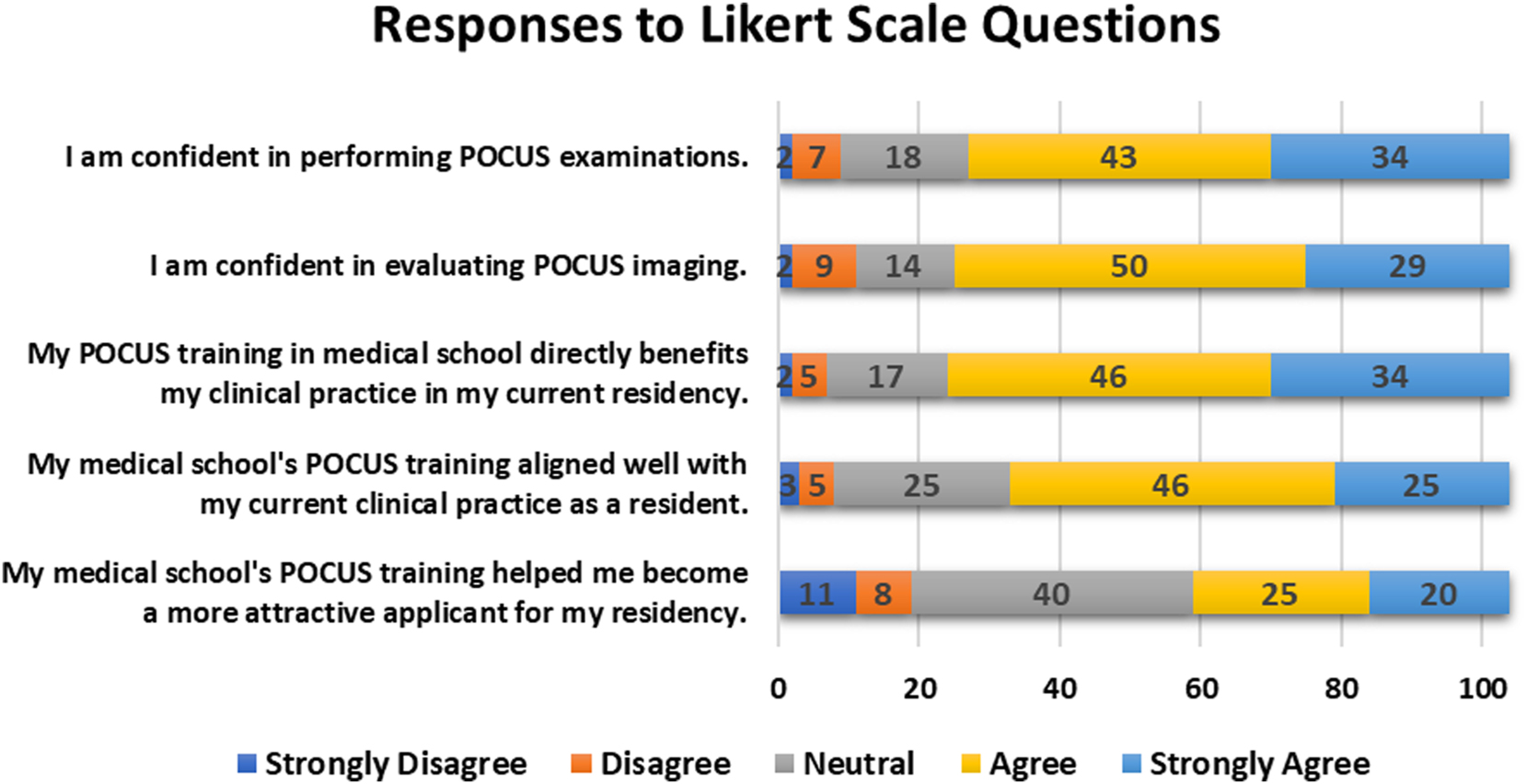

A Likert scale was implemented to gauge respondents’ perceptions of their POCUS skill sets resulting from their MWU-AZCOM education. Among those indicating POCUS use in their residency practice, a considerable portion agreed or strongly agreed that their exposure to POCUS during medical school directly enriched their clinical practice (n=80, 76.9 %). Moreover, this exposure was positively associated with increased confidence in performing POCUS evaluations (n=77, 74.0 %) and interpreting POCUS imagery (n=79, 76.0 %). Furthermore, a notable subset of participants (n=45, 43.3 %) perceived that their medical school’s POCUS training increased their attractiveness as residency candidates. These data are represented in Figure 3. Respondents suggesting that their training in medical school was a factor in successfully matching into residency (n=45, 43.3 %) mainly went into emergency medicine (n=11, 24.4 %), family medicine (n=7, 15.5 %), and internal medicine (n=7, 15.5 %). Additionally, most participants (n=71, 68.3 %) maintained that their POCUS training aligned well with their subsequent clinical practice.

Most MWU-AZCOM graduates are comfortable performing and evaluating POCUS scans and agree that their POCUS training in medical school benefits them in their current residency program.

In the survey’s optional free-response section for improvement and additional comments, 22 respondents (21.1 %) provided input. Within the Improvement section, comments encompassed suggestions to fine-tune educational strategies to better equip participants for residency. These recommendations included fostering greater familiarity with procedures, “use without having to think,” and greater emphasis on pulmonary and cardiac POCUS. In the Additional Comments section, most respondents expressed positive regard for their POCUS medical education. Notably, one comment highlighted how POCUS “helps solidify anatomy” and “highly recommend continuing for future students.” Moreover, a respondent conveyed appreciation stating, “AZCOM has a well-thought-out ultrasound curriculum that is beneficial regardless of the specialty the student chooses.” There were also two respondents who utilized this section of the survey to highlight another perceived barrier preventing residents from utilizing POCUS: time. These respondents stated that residents “simply do not have the time to use POCUS” because “residents are already busy learning the hospital system, writing various notes (H&P, progress note, and discharge/death summary), putting orders, etc…. I end up relying on an ultrasound tech to complete the exam instead….”

Discussion

As POCUS has become an increasingly versatile tool across various medical specialties, and the benefit of immersing medical students from an early stage is evident [9]. Our survey shows that 85.6 % of AZCOM graduates regularly employ POCUS in their practice, with 75.3 % utilizing it daily or weekly. Given that most of these graduates consistently utilize ultrasound during their residencies, current medical students would benefit from developing a solid foundation in ultrasound training through a comprehensive 4-year longitudinal program. High levels of confidence in both performing POCUS (74.0 %) and interpreting POCUS (76.0 %) among our surveyed graduates underscore the benefits of introducing this modality in the didactic phase and continuing it through clinical rotations.

The current ultrasound curriculum at MWU-AZCOM involves hands-on POCUS training incorporated into the anatomy, physiology, and osteopathic clinical medicine courses in the first year (11 h total) and further training in the osteopathic clinical medicine courses in second year (4 h) as well as an optional 10-week annual ultrasound elective offered for 30 second-year medical students. Additional training is afforded during core clinical rotations in year 3 (family medicine, internal medicine, OBGYN, pediatrics, and general surgery) as well as one standardized Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), and in year 4 (critical care and emergency medicine), clinical faculty chairpersons have incorporated discipline-specific learning objectives pertinent to POCUS imaging along with providing hands-on, in-person ultrasound education. As students advance into audition rotations, there is a heightened emphasis on specialized focus, with faculty dedicating more time to this aspect of training. Notably, survey results indicate that 77.0 % of recent MWU-AZCOM graduates agree or strongly agree that their POCUS training in medical school directly benefits their clinical practice. These findings demonstrate the congruency of the medical education provided at MWU-AZCOM with the clinical practice undertaken by our recent graduates.

The survey data highlights that most POCUS applications by respondents are concentrated in clinical procedures (90.0 %), cardiac tests (89.0 %), and pulmonary examinations (82.0 %). One survey respondent specifically noted the greater utility of focusing on cardiac and abdominal ultrasound training by stating, “introduction to ultrasound is an excellent use of time, cardiac and abdomen should be done twice.” This feedback suggests that dedicating more curriculum time to these high-impact areas could further enhance the readiness of MWU-AZCOM graduates for their residencies. Research supports the efficacy of ultrasound training in significantly improving students’ skills in image acquisition and interpretation [17], bolstering the case for curriculum refinement.

While the foundation of medical education is crucial, ongoing education in residency is equally important. Although 43.3 % of respondents report no barriers to POCUS utilization, over one-third of respondents specifically cite a lack of training and trained faculty as an impediment, particularly within family medicine and internal medicine. Because both specialties were among the strongest reporters of utilizing POCUS diagnostically, the importance of increasing competency within these residencies cannot be overstated. This barrier within residencies, specifically family medicine, will be addressed soon by the ACGME, which recently announced that POCUS competency will be a requirement for accreditation starting in 2024 [3]. This could explain the reports of a lack of trained faculty from residents, because prior to this requirement, the only specialty formally required to provide residents with POCUS training by the ACGME was emergency medicine. Moreover, our study reveals that the primary facilitators for POCUS adoption are its cost-effectiveness (82.0 %), contribution to patient safety (79.8 %), and diagnostic utility (78.7 %). These factors reinforce the necessity of ensuring ultrasound competency in medical education to equip future physicians for success. The utility of a longitudinal POCUS curriculum is dual: It prepares new residents for their clinical responsibilities and allows medical students to distinguish themselves during clinical rotations. According to the survey, an impressive 43.3 % of participants believed that their POCUS training during medical school helped make them a more attractive applicant when applying to residencies.

Looking ahead, the next steps in advancing POCUS education should involve addressing the identified barriers, such as the shortage of trained faculty, financial constraints, and the obstacle of navigating medical students’ demanding schedules, all while exploring innovative ways to provide comprehensive, hands-on training. Identical barriers were also identified in the recent study by Slyvka and Gwilym [18]. By investing in ultrasound education at the medical school level, these barriers can be proactively tackled without major administrative overhaul at the hospital level, and the identified shortcomings with current POCUS use in practice can begin to be addressed. If integrated into the clinical years and audition rotations, POCUS training can enhance students’ proficiency and competitiveness prior to applying to residency. This approach would provide efficient and cost-effective means to strengthen POCUS in residency and beyond, because the students empowered by this education will themselves provide the foundational basis for the next generation of physicians. To this end, it is imperative that medical schools adapt their curricula to ensure that the future physicians they produce are well-equipped to leverage the potential of POCUS to augment patient care and comfort.

Limitations

Although we obtained sufficient data for our study, we were limited by the relatively small sample size (n=104) and the potential for response bias. Because only completed surveys were analyzed, the data may be skewed toward those who are more engaged with POCUS in their practice. Also of note, ACGME did not require ultrasound integration in family medicine residencies when these surveys were administered, which may contribute to lower use in the sampled family medicine residents.

Conclusions

POCUS integration into medical education, particularly through a 4-year longitudinal curriculum, has provided significant benefits to current residents who have attended MWU-AZCOM. Our study highlights that recent AZCOM medical graduates who received POCUS training throughout their 4 years are now utilizing POCUS regularly, with the majority indicating a prominent level of confidence in both performing and interpreting ultrasound examinations. With the recent change in residency accreditation requirements, such as in family medicine, medical students must acquire proficient exposure to this modality to ensure their competitiveness. This showcases the importance of introducing POCUS as an integral part of medical school education because it enhances clinical skills and parallels the real-world integration of POCUS in medical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine and College of Graduate Studies for their support with the publishing process. Additionally, the authors would like to thank all participants for their contributions.

-

Research ethics: The study was reviewed and approved by the Midwestern University (MWU) Institutional Review Board; #IRBAZ-5169 approved 3/10/2022.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Data can be shared on request.

References

1. Moore, CL, Copel, JA. Point-of-care-ultrasonography. N Engl J Med 2011;364:749–57. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra0909487.Search in Google Scholar

2. Fox, JC, Schlang, JR, Maldonado, G, Lotfipour, S, Clayman, RV. Proactive medicine: the “UCI 30,” an ultrasound-based clinical initiative from the University of California, Irvine. Acad Med 2014;89:984–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000292.Search in Google Scholar

3. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in family medicine 2024.Search in Google Scholar

4. Hoppmann, RA, Rao, VV, Poston, MB, Howe, DB, Hunt, PS, Fowler, SD, et al.. An integrated ultrasound curriculum (iUSC) for medical students: 4-year experience. Crit Ultrasound J 2011;3:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13089-011-0052-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Bahner, DP, Goldman, E, Way, D, Royall, NA, Liu, YT. The state of ultrasound education in U.S. medical schools: results of a national survey. Acad Med 2014;89:1681–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000414.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Dinh, VA, Fu, JY, Lu, S, Chiem, A, Fox, JC, Blaivas, M. Integration of ultrasound in medical education at United States medical schools: a national survey of directors’ experiences. J Ultrasound Med 2016;35:413–9. https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.15.05073.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Bahner, DP, Adkins, EJ, Hughes, D, Barrie, M, Boulger, CT, Royall, NA. Integrated medical school ultrasound: development of an ultrasound vertical curriculum. Crit Ultrasound J 2013;5:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/2036-7902-5-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Russ, BA, Evans, D, Morrad, D, Champney, C, Woodworth, AM, Thaut, L, et al.. Integrating point-of-care ultrasonography into the osteopathic medical school curriculum. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2017;117:451–6. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2017.091.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Rempell, JS, Saldana, F, DiSalvo, D, Kumar, N, Stone, M, Chan, W, et al.. Pilot point-of-care ultrasound curriculum at harvard medical school: early experience. West J Emerg Med 2016;17:734–40. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2016.8.31387.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Nydam, R, Patel, A, Finch, C. Incorporation of clinically-based ultrasound workshops in a 1st year medical anatomy course. FASEB J 2018;32:636.5. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.2018.32.1_supplement.636.5.Search in Google Scholar

11. Miller, C, Weindruch, L, Gibson, J. Near peer POCUS education evaluation. POCUS J 2022;7:166–70. https://doi.org/10.24908/pocus.v7i1.15019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Dietrich, CF, Hoffmann, B, Abramowicz, J, Badea, R, Braden, B, Cantisani, V, et al.. Medical student ultrasound education: a WFUMB position paper, Part I. Ultrasound Med Biol 2019;45:271–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.09.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Arora, S, Cheung, AC, Tarique, U, Agarwal, A, Firdouse, M, Ailon, J. First-year medical students use of ultrasound or physical examination to diagnose hepatomegaly and ascites: a randomized controlled trial. J Ultrasound 2017;20:199–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40477-017-0261-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Boniface, MP, Helgeson, SA, Cowdell, JC, Simon, LV, Hiroto, BT, Werlang, ME, et al.. A longitudinal curriculum in point-of-care ultrasonography improves medical knowledge and psychomotor skills among internal medicine residents. Adv Med Educ Pract 2019;10:935–42. https://doi.org/10.2147/amep.s220153.Search in Google Scholar

15. Hosseini, M, Bhatt, A, Kowdley, GC. Effectiveness of an early ultrasound training curriculum for general surgery residents. Am Surg 2018;84:543–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/000313481808400428.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Kern, J, Scarpulla, M, Finch, C, Martini, W, Bolch, CA, Al-Nakkash, L. The assessment of point-of-care-ultrasound (POCUS) in acute care settings is benefitted by early medical school integration and fellowship training. J Osteopath Med 2022;123:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2021-0273.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Fox, JC, Chiem, AT, Rooney, KP, Maldonaldo, G. Web-based lectures, peer instruction and ultrasound-integrated medical education. Med Educ 2012;46:1109–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12039.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Slyvka, Y, Gwilym, JL. Teaching ultrasound in osteopathic medical schools. J Osteopath Med 2023;124:107–13. https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2023-0027.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2024-0046).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Review Article

- The negative effects of long COVID-19 on cardiovascular health and implications for the presurgical examination

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- The assessment of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in residency: the benefits of a four-year longitudinally integrated curriculum

- The impact of osteopathic recognition on multiple medical specialty residencies in a university-based setting

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- An osteopathic assessment of lower extremity somatic dysfunctions in runners

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Impact of osteopathic manipulative medicine training during graduate medical education and its integration into clinical practice

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Original Article

- Prevalence of pelvic examinations on anesthetized patients without informed consent

- Letter to the Editor

- Addressing confounding factors in the match disparities between DO and MD seniors

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Review Article

- The negative effects of long COVID-19 on cardiovascular health and implications for the presurgical examination

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- The assessment of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in residency: the benefits of a four-year longitudinally integrated curriculum

- The impact of osteopathic recognition on multiple medical specialty residencies in a university-based setting

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- An osteopathic assessment of lower extremity somatic dysfunctions in runners

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Impact of osteopathic manipulative medicine training during graduate medical education and its integration into clinical practice

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Original Article

- Prevalence of pelvic examinations on anesthetized patients without informed consent

- Letter to the Editor

- Addressing confounding factors in the match disparities between DO and MD seniors