Abstract

Context

With the advent of the Single Accreditation System (SAS) within the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), few programs have achieved Osteopathic Recognition (OR) status to date. OR is an accreditation that graduate medical education (GME) programs can achieve to distinctly acknowledge the additional focus on osteopathic training. There is an effort by national osteopathic organizations to determine barriers for programs to achieve OR and what innovative methods might help overcome them. In identifying its own barriers, a central Ohio hospital created a unique Program Director for Osteopathic Medical Education (PDOME) role to assist its 10 programs in achieving OR.

Objectives

The objectives of this study were to determine the effect that a PDOME role has through measures of the numbers of programs achieving OR and standards met, as well as the perceived ‘helpfulness’ of the role based on surveys of program leadership.

Methods

Upon initiation of the PDOME in July 2021, the PDOME assessed applications, citations, and curriculums of the 10 hospital programs with varied OR status to help determine curricular goals. Additional osteopathic activities, evaluation tools and faculty development were subsequently offered based on this information and needs assessments of the programs. A survey was sent to all programs at intervals of 12 and 18 months after role inception to be utilized as process improvement. Comparisons were made between surveys, as well as between the total number of programs with continued OR status and the total OR requirements achieved before and after PDOME. A chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test when the ‘n’ was too small) was utilized for significance, and the p value was set at 0.05.

Results

After the PDOME, there was a significant increase in the number of OR standards met across programs (p<0.001). Although not significant, the number of programs achieving continued OR increased from 4 to 8 (p=0.168). Due to many positive responses in both surveys, there was no significance between surveys in the “helpfulness” of PDOME; however, there was a significant increase in the number of respondents from 13/67 (or 19.4 %) to 32/67 (or 47.8 %) (p<0.001), indicating increased engagement among respondents.

Conclusions

This study suggests that a PDOME role in medical education may be well received and may assist GME programs in achieving OR. Implementation of a similar role elsewhere could help programs overcome barriers and stir growth in OR programs nationwide.

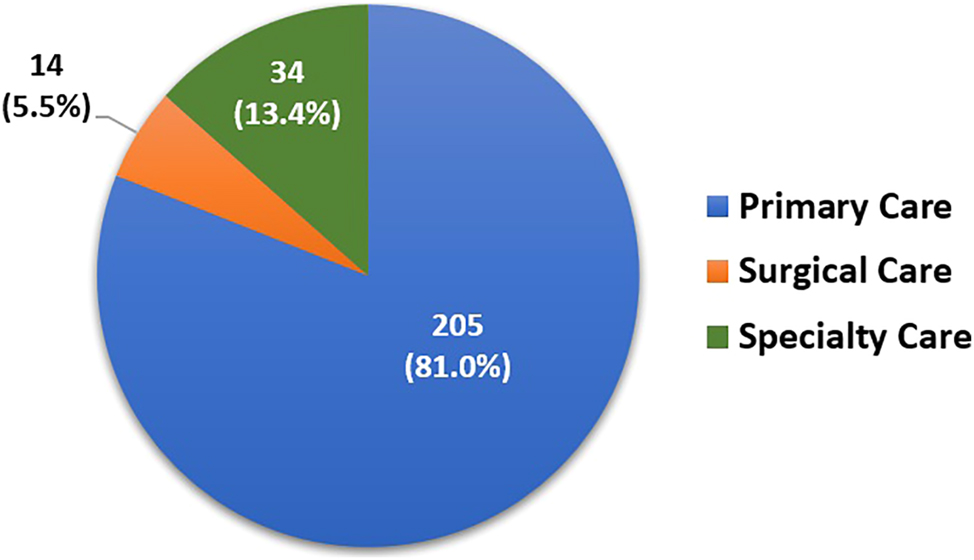

The five-year transition to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Single Accreditation System (SAS) was completed in June 2020. With the formation of the SAS, the ACGME established an additional accreditation status known as Osteopathic Recognition (OR) that distinctly acknowledges the additional focus on Osteopathic Principles and Practice (OPP) in the training of residents or fellows [1]. Once a program has achieved ACGME accreditation by their specialty review committee, they can apply for OR status [1]. Of the 877 osteopathic programs previously accredited with the American Osteopathic Association (AOA) prior to the SAS [2], only 253 programs have applied for or have achieved OR status thus far, and most of those are in primary care [3] (Figure 1). While research is beginning to determine the barriers that prevent graduate medical education (GME) programs in applying for OR [4], it has been reported in a recent survey of 280 program directors that 31.4 % of the programs would apply for OR if resources were more readily available to do so [5]. Therefore, it is important to identify innovative resource methods that assist programs in achieving OR status to ensure that there is optimal availability for osteopathic training across specialties within GME programs.

The distribution of graduate medical education (GME) training programs that have applied for or have achieved osteopathic recognition (OR) at the time of this study.

OR provides GME programs with tangible reported benefits. The status allows programs to apply osteopathic principles to fields of interest by supporting education around quality holistic care, osteopathic manipulation, and osteopathic research [1]. The osteopathic approach to care has been found to both improve patient satisfaction and lower cost [6]. In addition, graduate Doctors of Osteopathic Medicine (DOs) continue to express interest in furthering their training in the philosophy of osteopathic medicine [7], thereby validating the work for programs to achieve OR. Thus, OR status has been perceived as a recruiting tool among program directors to increase both the number of qualified osteopathic applicants, as well as those allopathic students interested in learning osteopathic skills [5], 6]. Lastly, the promotion of OR is vital to the profession because the post-graduate period has been found to be the most critical in learning OPP if physicians are to retain their skills in osteopathic medicine [8].

As one of the largest independent osteopathic training institutions in the United States, the medical education department of a mid-sized community-based hospital in central Ohio has a mission to become a “Premier Center for Osteopathic Education.” To meet this mission, they realized that it was vital to achieve and meaningfully maintain OR status in all its primary care, subspecialty, and surgical GME programs. The hospital faced the challenge of navigating both ACGME specialty accreditation and the additional requirements for achieving OR. This process increased administrative demands for program directors, regardless of their MD/DO background, particularly in curriculum development, faculty development, and OPP proficiency. In response, the medical education leadership created a unique Program Director for Osteopathic Medical Education (PDOME) role to provide administrative and strategic support for these programs. The PDOME role was responsible for working with program leadership to enrich the osteopathic training by developing innovative educational activities, promoting osteopathic care, collaborating with educational partners, connecting with the community, furthering osteopathic research, and advocating for the profession. A similar role at other institutions has not been documented in the literature.

The purpose of this retrospective quality improvement (QI) project was to determine the effect that this PDOME role has had on the hospital residency training programs at this site through surveys of program leadership and objective measures. This study aimed to:

Determine the number of OR standards that programs had achieved prior to and following implementation of the PDOME role.

Compare the number programs achieving Continued Recognition before and after implementation of the PDOME role.

Determine the satisfaction level that the role creates for the osteopathic faculty of the programs.

Utilize survey information in the name of QI to adapt/implement additional changes and respond to the needs identified.

The hypothesis of this study was that the PDOME would effectively increase both the number of OR standards achieved and the number of programs with Continued Recognition (particularly in the surgical and subspecialty fields), as well as to be a helpful addition to medical education staff.

Methods

This study was evaluated by the OhioHealth Office of Human Subjects Protections and deemed exempt from review as a QI project from its Institutional Review Board (IRBNet# 1915535–1). As a QI project, survey participants were not deemed human subjects and informed consent was not necessary. There was no identified risk to the participants in the survey because they were not given identifiers and information was collected anonymously in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system. The study did not receive any funding, and the survey participants participated voluntarily and were not provided any financial compensation.

Upon initiation of the role in July 2021, the PDOME reviewed the OR applications, citations, and curriculums of all 10 of its GME programs. These programs included Anesthesia, Emergency Medicine, Family Medicine, General Surgery, Internal Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Orthopedic Surgery, and Otorhinolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery residencies and the Cardiology and Pulmonary-Critical Care fellowships. At baseline, four programs had already achieved Continued Recognition status (Emergency Medicine, Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, and Obstetrics and Gynecology). The Emergency Medicine Service Fellowship was excluded due to the inapplicability of OR to the specialty. The OR standards achieved prior to the creation of the PDOME role were documented in a common graph to be compared to the same list of standards achieved at the completion of the study period. The PDOME and program coordinator for OR then set up initial meetings with osteopathic program faculty to further assess their needs. Program Directors, Directors of Osteopathic Education (DOEs), and program coordinators reviewed the data assessed and created a plan to meet additional OR standards. Common areas of deficiency from the 10 programs were identified to determine priorities of focus for further curricular development. These common areas included: osteopathic faculty development, evaluations of learners, osteopathic scholarly work, and the teaching of osteopathic skill. Based on the common needs identified among programs from these meetings, the PDOME then worked with programs to initiate osteopathic activities in five categories to ensure optimal success in meeting OR standards and to increase opportunity (Table 1).

The five categories of osteopathic activities created by PDOME based on the deficiencies/needs of OR programs and the activities implemented.

| Category name | Activities/change implemented |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

CORTEx, Clinical Osteopathic Recognition Training Exam; OMM, Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine; OPP, Osteopathic Principles and Practice; OR, Osteopathic Recognition; OUHCOM, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine; PDOME, Program Director for Osteopathic Medical Education.

A survey (Table 2) was created and distributed to DOEs, osteopathic faculty, and program coordinators from each of the 10 programs (67 total individuals) regarding the effectiveness of the PDOME role in helping programs meet standards or enhance osteopathic learning opportunities. This survey has not been validated. The survey was administered anonymously via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) at 12 months (in July 2022) and 18 months (in December 2022) after initiation of the PDOME role. The 12-month survey responses were utilized by the PDOME to create and/or alter planned osteopathic opportunities to better satisfy the needs of programs as the process of continuous improvement ensued. Administration of the survey at 18 months reflected feedback from the programs in response to the implementation of additional change from the 12-month survey.

Survey on PDOME effectiveness sent to the leadership and coordinators in 10 Osteopathic Recognized programs.

| Question | Available responses |

|---|---|

| How often have you, your osteopathic faculty, or your residents/fellows met with the program director for osteopathic education (PDOME)? |

|

| What areas has the PDOME helped you, your program, or faculty/learners? |

|

| How helpful have you found the implementation of the PDOME role at the hospital for implementing standards? |

|

| What feedback do you have to improve the work of the PDOME? | (Free text box available) |

| What needs in osteopathic recognition are not met? |

|

| What areas would you like to see the PDOME work on in the future? | (Free text box available) |

-

ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; PDOME, Program Director for Osteopathic Medical Education.

Survey responses from the participants were reported utilizing frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and utilizing means and standard deviations and/or medians and ranges for continuous variables. For reporting purposes, we calculated the combined number (percent) of positive responses (extremely helpful+somewhat helpful). The comparison of pre-post survey responses, and other collected objective data, were performed utilizing the chi-square test. When the sample size was very small, Fisher’s exact tests were utilized to detect statistical significance. The p value for the significance for these was set at 0.05 for all tests.

Results

Upon the establishment of the PDOME role, there were 180 hospital-wide standards of OR completed out of a total of 260 (Table 3). Among the 10 programs, four had achieved OR status at baseline, whereas the remaining six programs faced impending site visits with the ACGME. The timing of these additional six program site visits all fell within the designated study time frame of this project. An additional 70 standards were achieved across the 10 specialty programs at 18 months after implementation of the PDOME role. This was found to be a statistically significant increase in the number of standards met across programs (χ2=65.84, p<0.001) (Table 3). As a result of meeting these additional standards, the number of programs receiving Continued OR status also increased from four having OR at baseline to eight (adding Anesthesia, General Surgery, Otolaryngology/Head and Neck surgery, and the Cardiology Fellowship) during the study period (18 months) (Table 3). Although this was not statistically significant (p=0.168), when adding the two remaining programs (Orthopedic Surgery residency and Pulmonary-Critical Care Fellowship) that did eventually achieve Continued OR (and underwent site visits within the 18-month study period but had not yet received their notification letters by the end of the study), the value becomes significant (p=0.011). None of these 10 programs received a warning or probationary status, and all 10 continue with Continued Recognition status today.

The effects of PDOME on Osteopathic Recognition (OR) in hospital programs on achieving Continued Osteopathic Recognition Status and meeting OR standards.

| Hospital programs with ‘continued recognition’ status | OR standards met – all programs | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-PDOME role | 4/10 (40 %) | 180/260 (69.2 %) |

| After PDOME (at 18 months) | 8/10 (80 %) | 250/260 (96.2 %) |

| P Value |

a0.168 | χ2=65.84 P<0.001 |

-

PDOME, Program Director for Osteopathic Medical Education. aIndicates Fisher’s exact test.

Regarding the feedback from the survey administered at 12 months following the implementation of the PDOME role, only 13/67 (or 19.4 %) of the possible participants responded on the first survey. However, all 13 thought the PDOME was either “extremely helpful” or “somewhat helpful.” At the follow-up survey at 18 months after the implementation of the PDOME, 32/67 (or 47.8 %) of the possible participants responded on the second survey, with 31 expressing that the PDOME was either “extremely helpful” or “somewhat helpful” (Table 4). The difference in PDOME “helpfulness” was not determined to be significant between surveys; however, the increase in the number of respondents (from 13 respondents in the first survey to 32 respondents in the second) from 12 to 18 months was significant (χ2=12.08, p<0.001).

Satisfaction survey results among osteopathic faculty and staff at 12 months and 18 months after the initiation of the Program Director for Osteopathic Medical Education (PDOME) role (survey question: “How helpful have you found the implementation of the Program Director for Osteopathic Medical Education at the hospital for implementing OR standards?”).

| Response | Survey 1 (July 2022) | Survey 2 (Dec 2022) |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely helpful | 11 | 29 |

| Somewhat helpful | 2 | 2 |

| Neutral | 0 | 1 |

| Somewhat unhelpful | 0 | 0 |

| Not helpful at all | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 13/67 total | 32/67 total |

Discussion

The number of OR programs by the ACGME has been relatively stagnant and low over the last few years [2]. In response to the low number of OR programs, the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM) initiated a study in 2023 to determine the barriers that programs face in applying for OR voluntarily withdrawing OR status [4]. This comprehensive study was supported by the Osteopathic Heritage Foundation [4]. Data collection took place through surveys of programs (including those that had never applied for OR and those who withdrew their status), focus groups, and semi-structured interviews. Results from the 178/519 programs who responded reported the following barriers to achieving OR: administrative burden, lack of funding/support, evaluation requirements, and insufficient time to pursue OR [4]. Although direct interviews and focus groups indicated an acknowledgement of value in OR, discordance in perceptions led to general recommendations for improvements in OR for the future. These include the pursuit of collaborative opportunities, research into OR effects on osteopathic medical education, faculty development, exploration of ways to support programs, and input from institutions who have successfully achieved OR in its programs [4]. The success of a unique program director role for OR described in the current study is timely and summarizes one method to achieve many of these new initiatives outlined in the AACOM report.

In this study, a separate PDOME role ensured that there was devoted staff to work on specific osteopathic educational and administrative activities, allowed unloading of work from programs, and ensured innovation. The idea of creating this role to champion OR in an institution with multiple programs certainly goes beyond the 2014 white paper recommendations from the AACOM [9] or the ACGME OR-Review Committee core faculty requirements [1]. However, after implementation of the PDOME role and an organized plan to address common gaps in deficiency, the number of standards achieved among all 10 programs increased significantly. In addition, the survey results suggested that there was positive feedback for the PDOME role with increasing engagement of respondents in the osteopathic curriculum as time progressed, all affirming the hypothesis of this study.

When considering limitations of the study, it is important to note that positive feedback from survey responses in the study may have occurred regardless of PDOME effectiveness simply due to the burden of work that was removed from programs in the process. Also, the PDOME championing osteopathic training may have created some of the positive responses on the feedback survey. Nonetheless, these effects constitute reasoning for implementation of a PDOME role rather than limitations of the study in view of its authors. It is the experience of the authors that the mechanism of success of the PDOME is not solely attributed to the adding of resources or having a dedicated faculty member. Rather, the presence of PDOME in a leadership role overseeing and guiding program DOEs, while role modeling osteopathic care and education, were the keys to success. When considering other limitations of the study, it is difficult to determine if programs would have been able to achieve the documented success within the study period alone but without the PDOME role. However, a control group was not justified because it would not have created inequity in the educational environment among programs and trainees. In addition, the ability for the PDOME to create learning activities in a collaborative basis prevented duplication of work and produced an increased number of learning opportunities that might not otherwise have been possible if done individually by programs. Finally, the institutional site in the study had DO program directors in nine out of 10 of the programs at the time of PDOME role initiation, some which acted as the DOEs. The high presence of DO leadership in these programs may also have assisted in efforts toward achieving OR status outside. On the other hand, this number of DO program directors did decrease throughout the study (to 7/10 by study end), although the number of OR standards met in the programs increased, which speaks against this as an impactful variable in the study.

The largest challenge for other institutions replicating this educational innovation is the cost of an additional faculty member and administrative program coordinator. Initial support for the PDOME pilot was achieved through philanthropic requests. With the success of the pilot, the hospital made a commitment to continue supporting this role going forward. Additional challenges included a need for supplementary osteopathic teachers outside of the PDOME role, the need for specialty-specific osteopathic learning opportunities, and the amount of time needed to implement change. Joint osteopathic manipulative medicine (OMM) labs and learning activities, organized goals/objectives of the PDOME role, and more recently, collaboration with other institutions throughout the country with multiple programs, have been some ideas to overcome these challenges. Furthermore, osteopathic organizations like AACOM or the AOA could support a strategy around the implementation of roles like the PDOME and utilization of shared resources for smaller institutions needing additional osteopathic educational support.

Areas for future research include identifying specialty-specific barriers that individual programs face in achieving OR and how the PDOME role could help address these unique barriers. In addition, a longitudinal study comparing osteopathic education sites with and without the presence of the PDOME would be beneficial. Ultimately, this information could assist the OR-Review Committee in determining if and how to revise accreditation standards. Further study regarding the effect of the PDOME role on institutional utilization of OMM (via the training of additional GME providers), and the effects that the role has on osteopathic consultation, would be enlightening. Through these studies, any influences that the PDOME role has on the cost of care would also be worthy of exploration. Any financial benefit shown could certainly help to justify the position elsewhere.

Conclusions

Considering the additional requirements for programs to achieve ACGME accreditation for OR, hospital systems may consider the creation of a separate Osteopathic Program Director role to lead this effort. This innovative model could assist hospitals working to increase the variety and number of programs with OR. As a consequence of collaboration among PDOME, DOEs, and osteopathic faculty in these programs, postgraduate osteopathic learning experience could be optimized for generations to come.

-

Research ethics: The local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. ACGME Osteopathic Recognition Standards. Accreditation Council for graduate medical education; 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/801_osteopathicrecognition_2021v2.pdf [Accessed 21 March].Search in Google Scholar

2. List of programs that applied for accreditation under the Single accreditation system by specialty. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/ReportRun [Accessed Aug 8 2023].Search in Google Scholar

3. Former AOA Programs that have Transitioned to the ACGME Accreditation. Am Osteopath Assoc. https://osteopathic.org/index.php?aam-media=/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/single-gme-transitioned-program-opportunities.pdf [Accessed 8 Aug 2023].Search in Google Scholar

4. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM). Landmark study answers question: what’s next for osteopathic recognition? 2022. https://www.aacom.org/news-reports/news/2022/12/06/aacom-awarded-grant-to-conduct-national-first-of-its-kind-review-of-osteopathic-recognition.Search in Google Scholar

5. Maier, R, Weaver, J, Ginoza, JA, Meyer, D, Gothard, D. Perceived value of osteopathic recognition. Fam Med 2023;55:107–10. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2023.853908.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Rue, K, Stutzman, K, Chadek, M. The value of osteopathic recognition. Ann Fam Med 2021;19:86–7. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2663.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Hempstead, LK, Harper, DM. Incorporating osteopathic curriculum into a family medicine residency. Fam Med 2015;47:794–8.Search in Google Scholar

8. Rakowsky, A, Backes, C, Mahan, JD, Wolf, K, Zmuda, E. The development of a pediatric osteopathic recognition track. Acad Pediatr 2019;19:717–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.06.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. Next steps for graduate medical education: osteopathic graduate medical education and the Single graduate medical education accreditation system. Chevy Chase, MD; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Clinical Practice

- Improving peripheral artery disease screening and treatment: a screening, diagnosis, and treatment tool for use across multiple care settings

- General

- Brief Report

- Trends of public interest in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) from 2004 to 2022

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Effectiveness of a program director for osteopathic medical education to support osteopathic recognition at a training site with multiple programs

- Review Article

- A comprehensive review of clinical experiences and extracurricular activities for US premedical students applying to osteopathic medical schools

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Review Article

- The role of osteopathic manipulative treatment for dystonia: a literature review

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Modeling the importance of physician training in practice location for Ohio otolaryngologists

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Clinical Practice

- Improving peripheral artery disease screening and treatment: a screening, diagnosis, and treatment tool for use across multiple care settings

- General

- Brief Report

- Trends of public interest in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) from 2004 to 2022

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Effectiveness of a program director for osteopathic medical education to support osteopathic recognition at a training site with multiple programs

- Review Article

- A comprehensive review of clinical experiences and extracurricular activities for US premedical students applying to osteopathic medical schools

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Review Article

- The role of osteopathic manipulative treatment for dystonia: a literature review

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Modeling the importance of physician training in practice location for Ohio otolaryngologists