Abstract

Context

Pain of the coccyx, coccydynia, is a common condition with a substantial impact on the quality of life. Although most cases resolve with conservative care, 10 % become chronic and are more debilitating. Treatment for chronic coccydynia is limited; surgery is not definitive. Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) is the application of manually guided forces to areas of somatic dysfunction to improve physiologic function and support homeostasis including for coccydynia, but its use as a transrectal procedure for coccydynia in a primary care clinic setting is not well documented.

Objectives

We aimed to conduct a quality improvement (QI) study to explore the feasibility, acceptability, and clinical effects of transrectal OMT for chronic coccydynia in a primary care setting.

Methods

This QI project prospectively treated and assessed 16 patients with chronic coccydynia in a primary care outpatient clinic. The intervention was transrectal OMT as typically practiced in our clinic, and included myofascial release and balanced ligamentous tension in combination with active patient movement of the head and neck. The outcome measures included: acceptance, as assessed by the response rate (yes/no) to utilize OMT for coccydynia; acceptability, as assessed by satisfaction with treatment; and coccygeal pain, as assessed by self-report on a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS) for coccydynia while lying down, seated, standing, and walking.

Results

Sixteen consecutive patients with coccydynia were offered and accepted OMT; six patients also received other procedural care. Ten patients (two males, eight females) received only OMT intervention for their coccydynia and were included in the per-protocol analysis. Posttreatment scores immediately after one procedure (acute model) and in follow-up were significantly improved compared with pretreatment scores. Follow-up pain scores provided by five of the 10 patients demonstrated significant improvement. The study supports transrectal OMT as a feasible and acceptable treatment option for coccydynia. Patients were satisfied with the procedure and reported improvement. There were no side effects or adverse events.

Conclusions

These data suggest that the use of transrectal OMT for chronic coccydynia is feasible and acceptable; self-reported improvement suggests utility in this clinic setting. Further evaluation in controlled studies is warranted.

Coccydynia, or pain of the coccyx, is a common form of low back pain that can dramatically impact quality of life. Up to 10 % of cases are refractory to conservative therapy and become chronic and often debilitating. The population impact is unclear, although prevalence among women is five times that of men [1]. The precise etiology of the pain is multifactorial given the complex anatomical relationships and functional roles of the coccyx. In addition to female sex, major predisposing factors include external or internal trauma, including childbirth. Dysfunction of the pelvic floor muscles, surrounding soft tissue structures, bony alignment, and ganglion impar, are understood to contribute to pain.

Treatment options for refractory coccygeal pain are limited and include physical therapy, manual medicine, injections, and less often surgery, with mixed results [1, 2]. Over-the-counter and opioid pain medication are often utilized; each one has known harms when utilized chronically, and the harms associated with opioid prescription therapy are epidemic [3]. The identification of safe, effective treatment for low back pain, including coccygeal pain, remains a public health priority [4].

The anterior of the coccyx, like the rest of the spinal column, is inaccessible to manual treatment from outside the body. The coccyx and its supporting soft tissues, including the sacrococcygeal ligament, are unique among the major areas of the spine and accessible to manual treatment via the rectum, transrectally. Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) is a core element of osteopathic medicine [5], with a long history of safe use for a variety of conditions, including coccygeal pain [6].

Transrectal OMT has been assessed for coccygeal pain; studies are limited to case reports and studies pairing transrectal OMT with other therapies, or physical therapy not involving other areas of the spine [7]. Concomitant patient-initiated movement of the head and neck during transrectal OMT theoretically supports normalization of soft tissue tension, bony alignment, and mechanics via direct anatomical structural relationships and continuity [8]. It is part of routine care for chronic coccydynia in our (BN) practice and is covered by third-party payers that cover OMT. We therefore undertook a quality improvement (QI) study to explore the feasibility, acceptability, and clinical effects of transrectal OMT for chronic coccydynia in a primary care setting.

Methods

The QI project took place from May 2016 to January 2019 in an academic family medicine practice at the University of Wisconsin. In accordance with federal regulations, Institutional Review Board review was not required because this work was deemed to be a QI project and not research as defined by 45 CFR 46.102(d); this report follows the Squire 2 QI reporting guidelines [9]. All patients provided written informed consent for the OMT procedures described and for the use of their de-identified data for analysis and publication. Written and verbal consent were obtained by the treating physician in the presence of a chaperone at the time of each clinical visit and before any procedures.

Patients eligible for the procedure were 18–65 years old with self-reported coccyx pain sufficient to limit comfortable sitting for at least 3 months, a clinical diagnosis of coccydynia (ICD-10 code M53.3), and who were refractory to nonsurgical standard of care. Assessment included coccygeal radiograph if the tip of the coccyx was not appreciated on palpation.

Patients not eligible for the procedure included those with potential coccygeal fracture or tumor, or other forms of untreated low back pain. Sexual abuse history was assessed; those with a history of sexual abuse were asked to establish counseling relationships to discuss the procedure and to determine whether to participate. The procedure was described to the patient in the presence of a same-sex medical assistant by the treating physician (BN). Written informed consent for the procedure and for the use of de-identified data in QI work was obtained from each interested patient. Patients received no financial compensation to participate. A same-sex medical assistant was present for the entire procedures.

Intervention

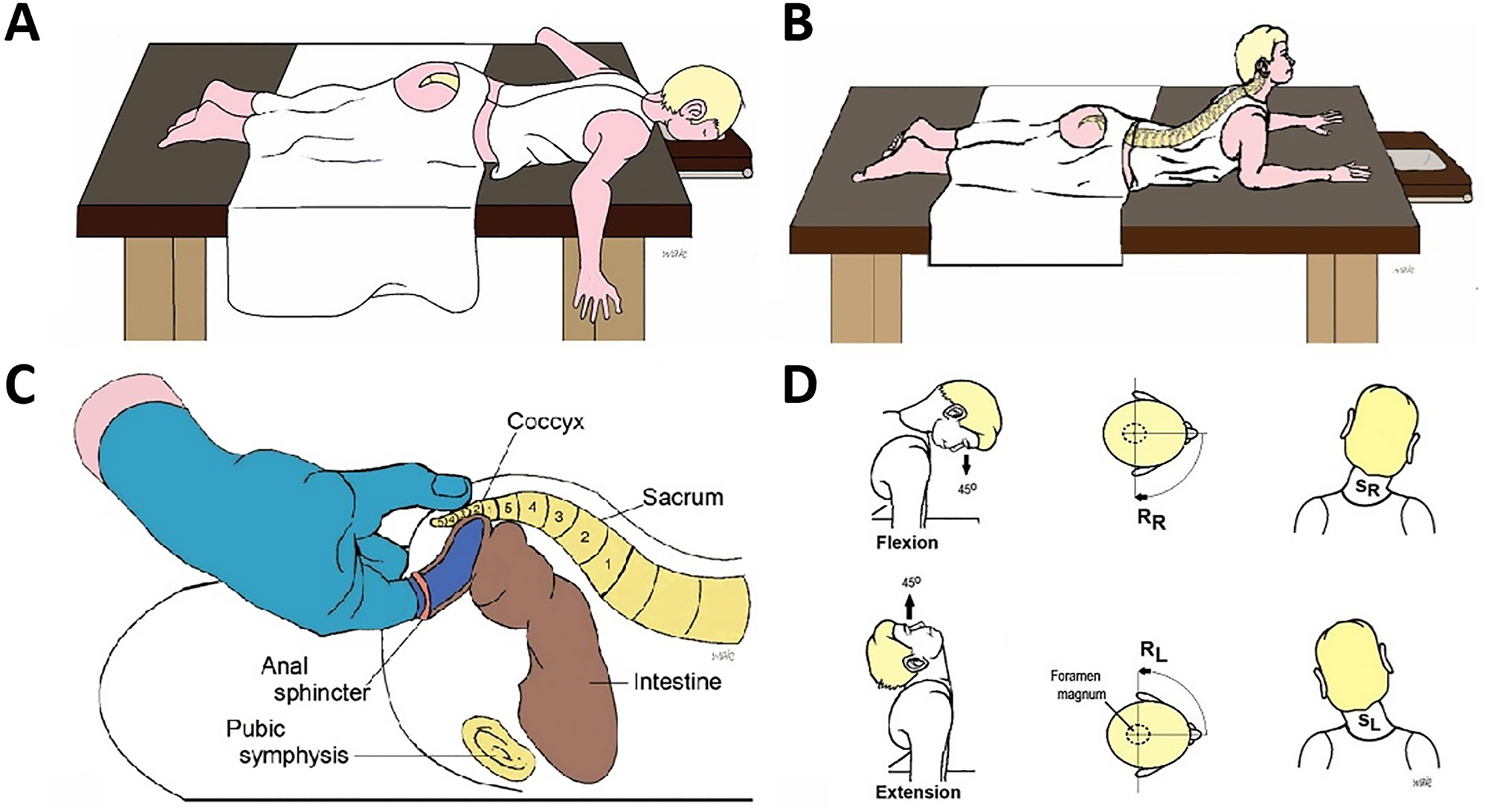

The full protocol has been published [8, 10]. Briefly, one treating osteopathic physician (BN) assessed and treated all participants. At treatment, the patient was placed in a prone position; the physician inserted a gloved, lubricated index finger transrectally, internally contacting the anterior coccyx while palpating the posterior coccyx externally with the thumb (Figure 1A–D). Treatment is focused on local soft tissue and bony structures. While propped on their elbows to induce spinal extension, the patients facilitated localization of the sacrococcygeal dysfunction by flexing, rotating, and sidebending their cervical spine as directed. Direct and indirect myofascial release and balanced ligamentous tension were applied with active patient assistance during the procedure, which lasted 2–6 min. Patients had the option to repeat the procedure in 1–2 weeks if pain resolution was less than satisfactory or if the pain returned.

Illustration of transrectal treatment and positions. (A) Patient is prone, face down with chest resting on the examination table. The prone position is utilized during Parts 1 and 3 of transrectal treatment when the provider is contacting and treating soft tissue structures. (B) The prone-propped patient position (sphinx position) for Part 2 of the treatment technique targeting the bony structures. Note the lumbar hyperextension, patient support utilizing their forearms, and chest and head lift as tolerated. (C) The clinician’s transrectal finger contacts the anterior sacrococcygeal surface while the external thumb contacts the posterior surface. This is utilized during Part 2 of treatment focusing primarily on the bony structures. (D) Three planes of cervical motion, including flexion/extension, rotation, and sidebending by the patient, utilized in combination with transrectal OMT during Part 2 of treatment.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were feasibility of transrectal OMT in our clinic, as defined by acceptance (rate of patients who accepted the procedure among all those offered it), adherence (rate of follow-through with one or more procedures and postprocedural care), and anecdotally assessed satisfaction with the procedure.

The secondary outcome was coccygeal pain as assessed by a numerical rating scale (NRS; 0–10 points). Patients were asked to identify pain scores utilizing the statement: “What is your pain on a 0–10 scale, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain you can imagine?” immediately before the procedure, immediately after the procedure, and at longer-term follow-up of at least 1 week. Pain was assessed immediately before and after the procedure in four different activities for each patient: lying down, seated, standing, and walking. We attempted to assess follow-up pain scores within 1 month. The NRS score for pain is commonly utilized in studies of chronic low back pain (CLBP) [11]. The minimal important change (MIC) in the NRS when assessing CLBP is 2.0 points or a 30 % change from baseline [12].

Analysis

Uptake of transrectal OMT has not been assessed. R 3.5.1 was utilized for all analyses. The ‘lme4’ package was utilized to fit linear mixed effects models and to construct confidence intervals and p values [13, 14]. Descriptive statistics were performed to describe outcomes at baseline and each time point; average value±standard deviation (SD) was reported at baseline unless otherwise specified.

Linear mixed effects models were utilized to examine the association between pain scores before or after treatment. Because pain scores were collected immediately before and after treatment at point of care, and then collected again at follow-up, two different models were fit to the data. The “acute” model utilizes the pain score immediately before and after treatment as the outcome, whereas the “follow-up” model utilizes only the pain score immediately before the first treatment and the pain score at follow-up as the outcome.

For both models, fixed-effects covariates included an indicator of whether the score was before or after treatment, patients’ position-specific score while laying, sitting, standing, or walking, sex of the patient, and age of the patient at scoring; random effects included subject-specific random intercepts. Statistical significance was assessed at the α=5 % level utilizing confidence intervals.

Due to the small sample size, bootstrap methods were utilized for inference instead of the typical asymptotic properties of mixed models. Confidence intervals were constructed utilizing the percentile method on parametric bootstrapping of the fitted models over 2,000 iterations [15]. p values were calculated by the proportion of times the t statistic for a covariate, from a simulated null distribution, was equal to or greater in magnitude than the associated statistic in the fitted model on the data, utilizing 10,000 bootstrap iterations [15].

Missingness occurred in both the acute model, in which posttreatment scores were not available for all positions, and in the follow-up model because not all subjects could be reached for follow-up assessment. In both cases, missingness was not explicitly addressed and was treated as missing-at-random (MAR). Demographic comparisons between those who did and did not have follow-up were examined, and although the statistical tests did not show any difference, they are likely underpowered to detect any difference that might exist, given the small number of subjects in each group. Mixed-effects models allowed the use of all data present, even if both pre/posttreatment pain scores were not available for a given position and subject.

Model diagnostics yielded no major concerns for residual trends, outliers, nonnormal residuals, nonnormal random effects, or dependency between residuals and random effects. There is a small residual heteroscedasticity concern for the follow-up model driven by the discrete/bounded nature of the data, but maintaining interpretability was felt to be more important here than utilizing transformations to fix this small issue in the follow-up model.

Results

Sixteen patients met the procedural criteria and were offered transrectal OMT care; 16 (100.0 % acceptance rate) agreed and received one treatment session of OMT. After one session of OMT, six patients received other care. Therefore, 10 patients (two males, eight females) received OMT intervention alone for coccydynia. Five received one procedure and five received two procedures, and these 10 patients were included in the per-protocol analysis. They were 44.7±12.9 years old, had a body mass index of 31.0±7.1 kg/m2, and had coccygeal pain for 6.4±6.0 years (Table 1).

Demographics.

| Range | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | 10 | |

| Male (N, %) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Mean age, years, SD | 44.7 (12.9) | 31.2–64 |

| Mean pain duration, years, SD | 6.4 (6.0) | 0.9–20 |

|

|

||

| No. of total treatments, % | ||

|

|

||

| 1 | 10 (100.0) | |

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | |

| Follow-up obtained, % | 5 (50.0) | |

| Mean follow-up length, months, SD | 1.6 (1.4) | 0.8–4 |

|

|

||

| Race, % | ||

|

|

||

| White | 7 (70.0) | |

| Unknown | 3 (30.0) | |

|

|

||

| Ethnicity, % | ||

|

|

||

| Hispanic/Latino | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 7 (70.0) | |

| Unknown | 3 (30.0) | |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2, SDa | 31.0 (7.1) | 23.6–44.9 |

-

aBMI is missing from three patients. BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Satisfaction was clinically observed to be high per follow-up with patients in clinic and or via telephone communication. In general, primary complaints of pain with sitting improved, as well as overall comfort with activity. Side effects included expected localized soft tissue soreness that resolved spontaneously in 1–2 days. We did not receive any negative feedback from patients.

In both the acute and follow-up models, posttreatment scores were significantly improved compared with pretreatment scores (Table 2, Figures 2 and 3). In the acute model (n=10), scores after treatment were 2.68 points lower (95 % CI, −3.50 to −1.83; p<0.001) than scores before treatment. Follow-up pain scores provided by five of the 10 patients at 1.62±1.38 months was 2.3 points lower (95 % CI, −3.29 to −1.17; p<0.001) than preprocedure. In regression models, the intercept comprises the estimated mean pain scores for subjects before treatment and in the “laying” position (and for female subjects in the acute model). The position coefficients represent the estimated change in the mean pain score compared to the “laying” position for both the pretreatment and posttreatment scores, and the “after treatment” coefficient (the estimated change in pain after treatment for all positions). The “seated” position being the only positive position estimate indicates that seated is the most painful position in the acute model, and the negative treatment estimates indicate that OMT is associated with a pain decrease across all positions in both the acute and follow-up models.

Pretreatment and posttreatment scores in the overall statistical model.

| Acute model | Follow-up model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observations | 71 | 40 | ||||

| Subjects | 10 | 5 | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Coefficient | Estimate | 95 % CI | p Value | Estimate | 95 % CI | p Value |

|

|

||||||

| After treatment | −2.68 | −3.50 to −1.83 | <0.001 | −2.28 | −3.29 to −1.17 | <0.001 |

| Seated position | 0.37 | −0.76–1.46 | 0.519 | 0.15 | −1.41–1.66 | 0.850 |

| Standing position | −0.41 | −1.53–0.68 | 0.473 | 0.00 | −1.47–1.58 | 1.000 |

| Walking position | −0.69 | −1.78–0.40 | 0.231 | 0.30 | −1.17–1.82 | 0.704 |

| Male | −1.89 | −4.60–0.96 | 0.227 | |||

| Age, years | −0.03 | −0.12–0.05 | 0.476 | |||

-

aModel reference categories (the intercept) are before treatment scoring, laying position, and female. CI, confidence interval. Significant values represented in bold.

The mean pain scores from before treatment, after treatment, and at follow-up. The most significant change is in the seated position.

The individual patient scores before and after treatment. As seen in clinical care, primary improvement is in the seated position.

Four of 10 patients in the acute model reported two or more points of improvement in the seated position in the acute model, whereas two of five patients reported two or more points of improvement in the seated position in the follow-up model (Figure 2).

There were no adverse events, including no reported emotional discomfort. OMT procedural fees were covered by third-party payers. Three patients reported increased pain immediately postprocedure acutely but improved compared to baseline status in the follow-up model. Patients in this study (n=4) who previously had a coccygeal manipulation procedure outside of the context of this project noted better pain reduction with active participation of head and neck movements.

Discussion

This QI study of participants with coccydynia treated with transrectal OMT and active patient participation with head movement has three main findings, First, feasibility of the procedure in this primary care clinic appears to be robust. Patients accepted transrectal OMT when offered. In general, patients expressed positive verbal satisfaction of the procedure and clinical outcome. The addition of active head and neck movement is new and may add to the effectiveness of the procedure. Second, data collection utilizing primarily electronic self-report resulted in missing data; adequate data collection will require more dedicated engagement by clinical staff regardless of data collection platform. Third, the clinical response appears to be positive and consistent with a small body of published literature.

While OMT appears to be feasible in our clinic setting and acceptable to patients, a procedure that depends upon a transrectal approach deserves comment, given the privacy issues and potential stigma associated with rectal anatomy. We followed the standards of medical professionalism in providing excellent musculoskeletal medical care informed by clear doctor–patient communication, the biopsychosocial model, and informed consent. These elements appear to have earned our patients’ trust. Clinically, conduct of the transrectal procedure falls well within convention. OMT is recognized as effective for many forms of musculoskeletal chronic pain, is commonly performed, and is covered by most third-party payers. Transrectal OMT for coccydynia is not often performed, but the procedure is otherwise consistent with OMT. Other medical procedures depend upon a transrectal approach for diagnostic and treatment procedures For example, assessment of rectal tone is routinely documented as part of the digital rectal examination in a workup of fecal incontinence, and colonoscopy is guideline-recommended care for colon cancer as well as for screening and treatment of other colonic conditions. Patients who might benefit from a transrectal diagnostic or treatment approach deserve this care option.

Our results add to the coccydynia treatment literature. Although most coccydynia patients improve with conservative management, treatment results for patients with refractory coccygeal pain are inconsistent. Techniques such as levator ani stretch, pelvic floor massage, and coccyx mobilization are associated with limited improvement in pain and quality of life compared with placebo [16]. A case report noted short-term relief of coccydynia utilizing transrectal OMT with supplemental anesthesia [17]. Combination therapy pairing manual techniques with other treatments have also produced positive but inconsistent results [18], [19], [20]. Positive results in a case report utilizing an identical OMT protocol were reported by the current team [10]. Other manual treatment, including a transrectal approach, is thought to reduce muscle tension [21] and relieve soft tissue irritation [16]. Multiple manual adjustment techniques have been described by Thiele [22] and Maigne [23]. Goals vary from mobilizing a stiff coccyx, coccygeal circumduction, and massage of the levator ani, piriformis, and coccygeus muscles [22]. Results have been mixed and may depend on the degree of coccygeal movement comparing standing vs. seated X-rays [16, 23]; none have been found to be uniformly effective. Improvement with manual therapies is reported to be associated with angulation of 5–20° between seated and standing radiographs; patients outside this range are more likely to require combined treatment modalities or surgery [16].

Mechanism

The precise mechanism of action OMT in coccydynia is not well understood. The procedure is consistent with other OMT procedures; therefore, the mechanism is likely also the same as that proposed for other OMT procedures. In general, providers attempt to restore biomechanics and physiologic function utilizing techniques targeting somatic dysfunctions of soft tissue and skeletal structures. Specific to coccydynia, transrectal OMT likely supports normalization of tonic muscles, soft tissue, sacrococcygeal mobility, and dural tension by dynamically treating the proximal and distal ends of the continuous anatomical structures. Unlike previous descriptions of transrectal OMT, the current version adds active patient movement of the head and neck to normalize the tone of the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments and the dura, with a likely effect of allowing the patient to control tension of the tissue manipulated by the provider. Patient participation through head movement and verbal feedback informs the clinician, allowing him or her to adjust the location and intensity of manipulation.

Limitations

This QI project is limited by small sample size, although an initial cohort of 16 and a final cohort of 10 participants approaches criteria for feasibility studies [24]. Follow-up and outcomes heterogeneity limits our ability to compare our results with those of other studies. Determination of causality between transrectal OMT and pain reduction is limited by the lack of a control group, although our patients had chronic pain that improved rapidly after the OMT procedure, suggesting a correlation between procedure and effect. There is substantial missing data, suggesting the need for more active data capture techniques.

Conclusions

These results suggest that transrectal OMT for coccydynia is feasible and acceptable to primary care patients. Most patients reported decreased pain on self-assessment immediately after the procedure and in follow-up. This QI study suggests the need for a larger and more formal study of transrectal OMT utilizing patient-assisted craniocervical movements directed by the provider for coccydynia.

Funding source: Financial grants for student support were provided by University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine and Community Health Summer Student Research and Clinical Assistantship Program, University of Wisconsin Shapiro Summer Research Program, and University of Wisconsin Medical Scientist Training Program Rural and Urban Scholars in Community Health.

Acknowledgments

The authors value and thank University of Wisconsin students Ross Gilbert, MSII; David Marshall, MSII; and Amy Fulcher for assisting with data collection, patient interviews, and research of anatomical relationships. The authors appreciate the generosity of Susan Standring, PhD, DSc, MBE Editor-in-Chief of Gray’s Anatomy, for review of the cranial–coccygeal anatomical relationships presented in this manuscript.

-

Research ethics: This project was identified as IRB-exempt by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board. In accordance with federal regulations, Institutional Review Board review was not required because this work was deemed to be a QI project and not research as defined by 45 CFR 46.102(d); this report follows the Squire 2 QI reporting guidelines.

-

Informed consent: All participants provided informed consent with the opportunity to ask any questions for clarification before receiving evaluation and treatment. Additionally, patients signed written informed consent forms for the treatment procedure.

-

Author contributions: All authors provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; all authors drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Competing interests: None declared.

-

Research funding: Financial grants for student support were provided by University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine and Community Health Summer Student Research and Clinical Assistantship Program, University of Wisconsin Shapiro Summer Research Program, and University of Wisconsin Medical Scientist Training Program Rural and Urban Scholars in Community Health.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Lirette, LS, Chaiban, G, Tolba, R, Eissa, H. Coccydynia: an overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. Ochsner J 2014;14:84–7.Search in Google Scholar

2. Howard, PD, Dolan, AN, Falco, AN, Holland, BM, Wilkinson, CF, Zink, AM. A comparison of conservative interventions and their effectiveness for coccydynia: a systematic review. J Man Manip Ther 2013;21:213–19. https://doi.org/10.1179/2042618613Y.0000000040.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Park, PW, Dryer, RD, Hegeman-Dingle, R, Mardekian, J, Zlateva, G, Wolff, GG, et al.. Cost burden of chronic pain patients in a large integrated delivery system in the United States. Pain Pract 2016;16:1001–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12357.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Pizzo, P, Clark, N, Carter-Pokras, O. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Mil Med 2016;181:397–9. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Seffinger, M. Foundations of osteopathic medicine: philosophy, science, clinical applications, and research, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

6. Barber, E. Osteopathy complete. Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing; 1898.Search in Google Scholar

7. Scott, KM, Fisher, LW, Bernstein, IH, Bradley, MH. The treatment of chronic coccydynia and postcoccygectomy pain with pelvic floor physical therapy. Pharm Manag R 2017;9:367–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.08.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Nourani, B, Huff, R. Long lever techniques: an illustrated guide for practitioners to treat neuro-musculoskeletal pain, 1st ed. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books; 2022.Search in Google Scholar

9. Goodman, D, Ogrinc, G, Davies, L, Baker, GR, Barnsteiner, J, Foster, TC, et al.. Explanation and elaboration of the SQUIRE (standards for quality improvement reporting excellence) guidelines, V.2.0: examples of SQUIRE elements in the healthcare improvement literature. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:e7–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004480.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Nourani, B, Gilbert, R, Rabago, D. The treatment of coccydynia and headache with transrectal OMT: a case report. Scholar: Pilot and Validation Studies 2020;1:14–18. https://doi.org/10.32778/spvs.71366.2020.4.Search in Google Scholar

11. Manchikanti, L, Cash, KA, McManus, CD, Pampati, V, Fellows, B. Results of 2-year follow-up of a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of fluoroscopic caudal epidural injections in central spinal stenosis. Pain Physician 2012;15:371–84. https://doi.org/10.36076/ppj.2012/15/371.Search in Google Scholar

12. Ostelo, RW, Deyo, RA, Stratford, P, Waddell, G, Croft, P, Von Korff, M, et al.. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine 2008;33:90-4. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing [computer program]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

14. Bates, D, Maechler, M, Bolker, B, Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Software 2015;67:1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Search in Google Scholar

15. Efron, B, Tibshirani, R. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993.10.1007/978-1-4899-4541-9Search in Google Scholar

16. Maigne, JY, Chatellier, G, Faou, ML, Archambeau, M. The treatment of chronic coccydynia with intrarectal manipulation: a randomized controlled study. Spine 2006;31:E621–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000231895.72380.64.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Emerson, SS, Speece, AJ. Manipulation of the coccyx with anesthesia for the management of coccydynia. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2012;112:805–7.Search in Google Scholar

18. Wray, CC, Easom, S, Hoskinson, J. Coccydynia. Aetiology and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991;73:335–8. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.73b2.2005168.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Khatri, S, Nitsure, P, Jatti, R. Effectiveness of coccygeal manipulation in coccydynia: a randomized control trial. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther 2011;5:110–12.Search in Google Scholar

20. Wu, CL, Yu, KL, Chuang, HY, Huang, MH, Chen, TW, Chen, CH. The application of infrared thermography in the assessment of patients with coccygodynia before and after manual therapy combined with diathermy. J Manip Physiol Ther 2009;32:287–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.03.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Maigne, JY, Chatellier, G. Comparison of three manual coccydynia treatments: a pilot study. Spine 2001;26:E479–484. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200110150-00024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Thiele, GH. Coccygodynia and pain in the superior gluteal region: and down the back of the thigh: causation by tonic spasm of the levator ani, coccygeus and piriformis muscles and relief by massage of these muscles. J Am Med Assoc 1937;109:1271–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1937.02780420031008.Search in Google Scholar

23. Maigne, JY, Maigne, R. Trigger point of the posterior iliac crest: painful iliolumbar ligament insertion or cutaneous dorsal ramus pain? An anatomic study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1991;72:734–7. https://doi.org/10.5555/uri:pii:000399939190260P.10.1097/00042752-199207000-00019Search in Google Scholar

24. Julious, SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharmaceut Stat 2005;4:287–91.10.1002/pst.185Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2023-0001).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Innovations

- Original Article

- The sternal brace: a novel osteopathic diagnostic screening tool to rule out cardiac chest pain in the emergency department

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- An analysis of osteopathic medical students applying to surgical residencies following transition to a single graduate medical education accreditation system

- An assessment of surgery core rotation quality at osteopathic medical schools

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Social determinants of health in patients with arthritis: a cross-sectional analysis of the 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Transrectal osteopathic manipulation treatment for chronic coccydynia: feasibility, acceptability and patient-oriented outcomes in a quality improvement project

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Evaluating attitudes among healthcare graduate students following interprofessional education on opioid use disorder

- Letter to the Editor

- Identified strategies to mitigate medical student mental health and burnout symptoms

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Innovations

- Original Article

- The sternal brace: a novel osteopathic diagnostic screening tool to rule out cardiac chest pain in the emergency department

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- An analysis of osteopathic medical students applying to surgical residencies following transition to a single graduate medical education accreditation system

- An assessment of surgery core rotation quality at osteopathic medical schools

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Social determinants of health in patients with arthritis: a cross-sectional analysis of the 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Transrectal osteopathic manipulation treatment for chronic coccydynia: feasibility, acceptability and patient-oriented outcomes in a quality improvement project

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Evaluating attitudes among healthcare graduate students following interprofessional education on opioid use disorder

- Letter to the Editor

- Identified strategies to mitigate medical student mental health and burnout symptoms