Abstract

Context

There has been a steady increase in the number of osteopathic (DO) medical students in the United States without a corresponding increase in DO representation in competitive specialties.

Objectives

To investigate the trends and impact of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) single accreditation system on DO match rates into dermatology and other competitive specialty programs.

Methods

Information was collected through public databases (Electronic Residency Application Service [ERAS]; National Resident Matching Program [NRMP]; Association of American Medical Colleges [AAMC]; National Match Service, Inc. [NMS]; and the ACGME) to evaluate the match statistics of competitive specialties, including dermatology, otolaryngology, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and plastic surgery. Residency program and medical school websites and residency communications were used to confirm whether the match placements were to programs that had traditionally been ACGME-accredited or former American Osteopathic Association (AOA) programs.

Results

From 2012 to 2016 (pre-unification), osteopathic graduates comprised only 0.5% of the matches the specific specialties studied here and only 0.9% of ACGME dermatology positions. Post-unification (2017–2019), DOs comprised 2.0% of the matches into these specialties and 4.4% of the total ACGME dermatology positions. This apparent increase is misleading, as it is solely due to the transition of formerly AOA programs to ACGME status. The true post-unification DO match rate to traditionally ACGME programs is actually 0.6% for all competitive specialties and 0.4% for dermatology. Post-unification, 27.6% of formerly AOA positions in these competitive specialties were filled by allopathic (MD) applicants.

Conclusions

DO match rates into dermatology and other competitive specialties were poor prior to GME unification and continue to remain low. This situation, when coupled with the closing of many AOA programs and MDs matching into former AOA positions, threatens the future of osteopathic physicians in competitive specialties. Osteopathic recognition is one way to potentially help preserve osteopathic representation and philosophy in the single accreditation system era. Programs should not be hesitant to consider osteopathic applicants for competitive specialties.

The year 2020 represented a new era for residency programs. After July 2020, all American Osteopathic Association (AOA) residencies were required to apply to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) if they intended to train residents [1]. In theory, under a single graduate medical education (GME) accreditation system, allopathic (MD) and osteopathic (DO) students should have equal opportunities in obtaining residency positions. Historically, however, equal opportunity has not translated into equal acceptance and representation. This is particularly true in competitive specialties such as dermatology.

There has been a steady increase in the number of osteopathic medical students in the United States, with seven new osteopathic medical schools having opened in the past five years alone [2]. One in four medical students attend an osteopathic college of medicine in the United States [3], [4]. Yet there has not been a corresponding increase in DO representation among competitive specialties.

Methods

The online public databases Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS), National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), National Match Service, Inc. (NMS), and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) were used to gather statistics that evaluated USMLE and COMLEX scores, total applications, and unmatched applicants. Dermatology, otolaryngology, neurosurgery, plastic surgery (integrated), and orthopedic surgery were identified as some of the most competitive specialties [5], [6]. The NRMP also referred to these specialties as “traditionally competitive specialties” in 2019 [5].

The public databases were also used to compile annual match statistics from 2012 to 2019 for DO and MD candidates to the selected specialties. For dermatology, advanced (program year 2 [PGY-2]), categorical (PGY-1), and physician positions were included. All other included competitive specialties only match categorical (PGY-1) positions.

Data on DO and MD match placement that were not included in the above sources were gathered through residency program websites, medical school websites, and residency program communication. From 2017 to 2019, total available ACGME residency positions include both former AOA (newly ACGME-accredited) and historical ACGME programs (those previously accredited through the ACGME).

Results

Match statistics for the studied specialties from 2012 to 2019 are shown in Table 1A. Prior to implementation of single GME accreditation (2012–2016), herein referred to as “preunification,” DOs comprised only 0.5% of matches (47 of 8695) into competitive specialties (Table 1B). Newly ACGME-accredited (former AOA) programs first participated in the NRMP in 2017. After GME unification (2017–2019), herein referred to as “postunification,” DOs appeared to comprise 2% of these specialties (11 of 5785). However, when former AOA programs were excluded from the calculation of total postunification DO match rates into these specialties, the true DO match rates into traditionally ACGME positions was 0.6% (34 of 5658). At the time of this study, the total number of DO matches for 2020 was known for all competitive specialties; however, data about whether the matches were into former AOA or traditional ACGME positions was not yet known.

Number of matched applicants out of available ACGME competitive specialty positions before and after single graduate medical education accreditation transition.

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Pre-unification | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Post-unification | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derm | DO to total available ACGME | 3/363 | 4/407 | 3/414 | 5/427 | 4/440 | 19/2,051 (0.9%) | 8/463 | 16/472 | 40/504 | 64/1,439 (4.4%) | 83/3,490 (2.4%) |

| DO to traditionally ACGME | 3/363 | 4/407 | 3/414 | 5/427 | 4/440 | 19/2,051 (0.9%) | 2/453 | 1/447 | 2/450 | 5/1,350 (0.4%) | 24/3,401 (0.7%) | |

| DO to former AOA | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6/10 | 15/25 | 38/54 | 59/89 (66.3%) | 59/89 (66.3%) | |

| MD to former AOA | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2/10 | 6/25 | 14/54 | 22/89 (24.7%) | 22/89 (24.7%) | |

| ENT | DO to total available ACGME | 0/285 | 1/292 | 0/295 | 2/299 | 1/304 | 4/1,475 (0.3%) | 1/305 | 3/315 | 13/328 | 17/948 (1.8%) | 21/2,423 (0.9%) |

| DO to traditionally ACGME | 0/285 | 1/292 | 0/295 | 2/299 | 1/304 | 4/1,475 (0.3%) | 1/305 | 2/314 | 3/318 | 6/937 (0.6%) | 10/2,412 (0.4%) | |

| DO to former AOA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1/1 | 10/10 | 11/11 (100%) | 11/11 (100%) | |

| MD to former AOA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0/1 | 0/10 | 0/11 (0%) | 0/11 (0%) | |

| Ortho | DO to total available ACGME | 2/682 | 6/693 | 1/695 | 3/703 | 4/717 | 16/3,490 (0.5%) | 3/727 | 5/742 | 15/755 | 23/2,224 (1.0%) | 39/5,714 (0.7%) |

| DO to traditionally ACGME | 2/682 | 6/693 | 1/695 | 3/703 | 4/717 | 16/3,490 (0.5%) | 1/723 | 4/736 | 7/744 | 12/2,203 (0.5%) | 28/5,693 (0.5%) | |

| DO to former AOA | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2/4 | 1/6 | 8/11 | 11/21 (52.4%) | 11/21 (52.4%) | |

| MD to former AOA | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2/4 | 5/6 | 3/11 | 10/21 (47.6%) | 10/21 (47.6%) | |

| Neurosurgery | DO to total available ACGME | 1/196 | 2/204 | 3/206 | 0/210 | 0/216 | 6/1,032 (0.6%) | 2/218 | 3/225 | 4/232 | 9/675 (1.3%) | 15/1,707 (0.9%) |

| DO to traditionally ACGME | 1/196 | 2/204 | 3/206 | 0/210 | 0/216 | 6/1,032 (0.6%) | 2/218 | 1/222 | 3/229 | 6/669 (0.9%) | 12/1,701 (0.7%) | |

| DO to former AOA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2/3 | 1/3 | 3/6 (50%) | 3/6 (50%) | |

| MD to former AOA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1/3 | 2/3 | 3/6 (50%) | 3/6 (50%) | |

| Plastic surgery | DO to total available ACGME | 0/101 | 0/116 | 0/130 | 1/148 | 1/152 | 2/647 (0.3%) | 1/159 | 2/168 | 2/172 | 5/499 (1.0%) | 7/1,146 (0.6%) |

| DO to traditionally ACGME | 0/101 | 0/116 | 0/130 | 1/148 | 1/152 | 2/647 (0.3%) | 1/159 | 2/168 | 2/172 | 5/499 (1.0%) | 7/1,146 (0.6%) |

Abbreviations: Derm, dermatology; ENT, otolaryngology; Neurosurgery, neurologic surgery; Ortho, orthopedic surgery; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; AOA, American Osteopathic Association. aTotals may not add up to 100% as some years had unmatched positions. Plastic surgery (integrated) did not have any former AOA positions. ‘–’ No data available for that year.

Totals of competitive specialty-matched applicants before and after single graduate medical education accreditation transition.

| Preunification | Postunification | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total DO to total available ACGME | 47/8,695 (0.5%) | 118/5,785 (2.0%) | 165/14,480 (1.1%) |

| Total DO to traditionally ACGME | 47/8,695 (0.5%) | 34/5,658 (0.6%) | 81/14,353 (0.6%) |

| Total DO to former AOA | – | 84/127 (66.1%) | 84/127 (66.1%) |

| Total MD to former AOA | – | 35/127 (27.6%) | 35/127 (27.6%) |

‘–’ No data available for that year. ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; AOA, American Osteopathic Association.

Given our specialty, we paid particular attention to dermatology match data. In 2017, 2018, and 2019, there was an apparent increase in DOs who matched into ACGME dermatology programs. Preunification, DOs matched to 0.9% (19 of 2051) of the total ACGME dermatology positions. Postunification, DOs matched to 4.4% (64 of 1439) of the total ACGME dermatology positions. However, in 2017, 6 of the 8 (75%) DO dermatology matches were into former AOA positions. In 2018, 15 of the 16 (93.8%) DO dermatology matches were into former AOA positions; only 1 (0.2%) DO matched into a traditional ACGME position, the lowest DO-to-ACGME dermatology match rate observed over the previous seven years. In 2019, 38 of the 40 (95%) DO dermatology matches were into former AOA positions. Therefore, the true postunification DO match rate to traditionally ACGME dermatology programs was 0.4% (5 of 1,350). Approximately two fewer DOs matched per year to traditionally ACGME programs compared to preunification. From 2017 to 2019, only five DOs matched into 1,350 available traditional ACGME dermatology positions (0.4%).

DOs matching into other traditional ACGME competitive specialty positions have also experienced low match rates. When averaging DO match rates to ACGME positions from 2012 to 2019 (Table 1), DOs represented less than 1.0% (81 of 14,353) of all matches in otolaryngology, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and plastic surgery.

With the unification of GME, MD applicants are matching into former AOA positions that now have ACGME accreditation. Since unification, 27.6% (35/127) of former AOA positions in these competitive specialties have been filled by MDs (Table 1B). By specialty, MDs filled 24.7% (22 of 89) of dermatology, 0% (0 of 11) of otolaryngology, 47.6% (10 of 21) of orthopedic surgery, and 50% (3 of 6) of neurosurgery positions which were formerly AOA accredited. Integrated plastic surgery had no matches to formerly AOA accredited positions. Conversely, DOs only filled 0.6% (29 of 5159) of traditionally ACGME positions in these competitive specialties.

Discussion

Without careful interpretation of match data, it can appear that osteopathic match rates to ACGME competitive specialties are increasing. This increase is misleading and is due to the transition of former AOA programs into ACGME accreditation status and participation in the NRMP. When former AOA positions are excluded from the calculation of postunification DO match rates, the true DO match rates into traditionally ACGME positions remain alarmingly low.

Dermatology specialty data were extensively evaluated. Dermatology match procedures had historically differed between the NMS and NRMP. For DOs, dermatology was an “option 3” residency in the NMS, meaning applicants could only apply and match into dermatology as interns or after a research fellowship (PGY-1). For MDs, applicants classically applied and matched as fourth year medical students for categorical or advanced dermatology positions with few matching into physician positions (those reserved for physician applicants that did not match in PGY-4 and/or chose to complete a research fellowship or other residency). With GME unification, former AOA programs that have transitioned to ACGME accreditation must now adopt NRMP procedures in which they match fourth year medical students instead of interns. While evaluating the data, it became apparent that each former AOA program must now undergo a unique NRMP match year where they match both fourth year medical students and interns, essentially recruiting two class years simultaneously. This causes the match data and the number of DOs matching into ACGME dermatology to appear further inflated. This skew will be present in annual match data until all former AOA programs exclusively match 1 class year in the NRMP. It is also important to recognize that since unification, MD applicants now have the opportunity to match into former AOA (newly ACGME-accredited) positions that previously were available only to DO applicants.

While the unification of graduate medical education has many benefits, it also has contributed to AOA program closures. Of the specialties included in this study, 15 out of 91 former AOA programs have either not participated in the NRMP, have not yet achieved ACGME accreditation, or have voluntarily withdrawn (presumed closing) [7]. The decreasing DO match rates, coupled with the closing of AOA programs and MDs matching into former AOA positions, threatens the future of osteopathic physicians in competitive specialties. If the trends evidenced above continue, it will effectively decrease opportunities for osteopathic applicants to pursue competitive specialties and dramatically reduce the representation of osteopathic physicians practicing in those specialties. Losing this diversity within healthcare, especially losing osteopathic qualities that are known to benefit healthcare teams and patient experience [8], is something the medical community as a whole should adamantly try to prevent.

Healthcare is shifting to become more patient-centered and team-based, which is already aligned with existing osteopathic values [8]. The osteopathic philosophy, also known as osteopathic principles and practice (OPP), encompasses core principles that are taught from day one of medical training. Specifically, these principles stem from the osteopathic tenets: the body is a unit, the person is a unit of body, mind, and spirit; the body is capable of self-regulation, self-healing, and health maintenance; structure and function are reciprocally interrelated; and rational treatment is based on an understanding of these principles [8]. The osteopathic community has been utilizing this holistic approach to patient care since its inception and osteopathic physicians are an indispensable asset in the changing tides of medical care.

Maintaining residency positions designed to support and develop the osteopathic philosophical mindset and/or osteopathically-trained physicians is essential to the ongoing evolution of our healthcare system across all specialties. A recent study [9] suggested that osteopathic medical students experience a less significant decrease in empathy throughout their four years of medical school compared to their allopathic counterparts. Differences have also been found between osteopathic and allopathic physicians in communication with patients [8]; osteopathic physicians were shown to communicate in a more personal manner compared to their allopathic counterparts. Osteopathic physicians undergo extensive training in osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT), which requires a thorough understanding of the fundamental relationship between structure and function. This ultimately leads to a deep understanding of anatomy and the development of refined palpatory skills, both of which are valuable in nearly every medical specialty, especially dermatology, orthopedic surgery, and other surgical specialties. This reinforces the importance of accepting osteopathic physicians into all specialties and supports the benefits to patient care.

Osteopathic recognition (OR) has the potential to preserve the osteopathic philosophy and culture in the single accreditation era. Programs may apply for OR once ACGME accreditation is obtained; this designation demonstrates a program’s commitment to teaching and instilling OPP at the GME level [10]. For this reason, more programs should consider pursuing OR. Of the specialties reviewed, which included over 600 programs, only nine have pursued OR as of September 2020 (four are dermatology; four are orthopedic surgery; one is otolaryngology) [11].

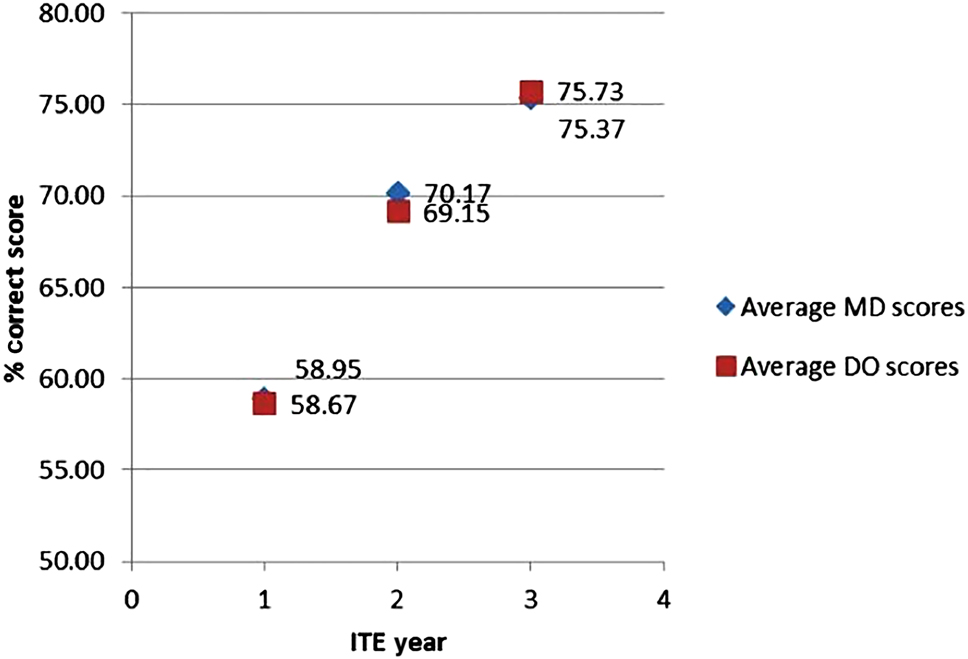

Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center (UH-CMC) dermatology program in Cleveland, Ohio is a large residency program accepting six residents per year; it was ranked as the 10th best dermatology program based on academic achievement in 2018 [12]. UH-CMC has consistently accepted two DO candidates and four MDs every year since 2003. In our internal review of a 14-year period at this institution, there was no statistical difference between the MD and DO dermatology residents’ scoring on the In-Training Exam (Figure 1) [13]. While this data is representative of only one program, it should encourage traditional ACGME programs to consider and match DOs just as formerly AOA programs have been considering and matching MDs.

In-training exam percent (%) correct score average comparison of osteopathic (DO) and allopathic (MD) graduates, 2005–2018.

Conclusions

DOs are highly underrepresented in competitive medical specialties. DO match rates into dermatology and other competitive specialties were poor prior to GME unification and continue to remain low. DOs – with a holistic approach to patient care, high levels of empathy, enhanced palpatory skills, and anatomical knowledge – are indispensable assets in the healthcare system and should be represented in competitive specialties. OR is a means to help potentially preserve the osteopathic philosophy and may assist in alleviating the DO representation disparity in the single accreditation system era. While continued data collection is warranted, ACGME programs of all specialties should not be hesitant to consider osteopathic applicants.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Kevin Cooper for his help in the creation of Figure 1 from data at our institution.

Research funding: None declared.

Author contributions: All authors provided substantial contribution to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; all authors drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

1. Buser, BR, Swartwout, J, Gross, C, Biszewski, M. The single graduate medical education accreditation system. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2015;115:251–5. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2015.049.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. U.S Osteopathic Medical Schools by year of inaugural class. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. https://www.aacom.org/docs/default-source/data-and-trends/u-s-osteopathic-medical-schools-by-year-of-inaugural-class.pdf?sfvrsn=dc9e2997_20 [Accessed 5 Sept 2020].Search in Google Scholar

3. Association of American Medical Colleges. Total enrollment by U.S. Medical School and Sex, 2015–2016 through 2019–2020; 2019. https://www.aamc.org/download/321526/data/factstableb1-2.pdf [Accessed 5 Jan 2020].Search in Google Scholar

4. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. Preliminary enrollment report fall; 2018. https://www.aacom.org/docs/default-source/data-and-trends/preliminary-enrollment-report-fall-20180c104f43514d6e069d49ff00008852d2.pdf?sfvrsn=54422197_8 [Accessed 5 Jan 2019].Search in Google Scholar

5. National Resident Matching Program. Results and data: main residency match 2012–2019. http://www.nrmp.org/report-archives/.NRMP [Accessed 2 Aug 2020].Search in Google Scholar

6. Association of American Medical Colleges. Historical specialty specific data, ACGME & AOA residency. https://www.aamc.org/eras-statistics-2019 [Accessed 2 Aug 2020].Search in Google Scholar

7. Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education. List of programs that applied for accreditation under the single accreditation system by specialty. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/Report/18 [Accessed 1 Sept 2020].Search in Google Scholar

8. Carey, T, Motyka, T, Garrett, J, Keller, R. Do osteopathic physicians differ in patient interaction from allopathic physicians? An empirically derived approach. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2003;103:313–8.Search in Google Scholar

9. McTighe, A, DiTomasso, R, Felgoise, S, Hojat, M. Effect of medical education on empathy in osteopathic medical students. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2016;116:668–74. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2016.131.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Osteopathic recognition requirements. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/801OsteopathicRecognition2018.pdf?ver=2018-02-20-154513-650 [Accessed 1 Nov 2019].Search in Google Scholar

11. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. List of programs applying for and with osteopathic recognition. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/Report/17 [Accessed 1 Nov 2019].Search in Google Scholar

12. Namavar, AA, Marczynski, V, Choi, YM, Wu, JJ. US dermatology residency program rankings based on academic achievement. Cutis 2018;101:146–9.Search in Google Scholar

13. Cooper, K. Sharing Insights on the first approved ACGME Osteopathic Recognition Dermatology Residency program [keynote address]. In: Maintaining an osteopathic presence in an ACGME World. Washington, D.C; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Elise Craig et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Registering your research: What’s required?

- General

- Brief Report

- A survey on health professionals’ understanding of federal protections regarding service dogs in clinical settings

- Innovations

- Original Article

- The use of 3D printing for osteopathic medical education of rib disorders

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- Teaching and use of cervical high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulation at colleges of osteopathic medicine

- The Philadelphia surgery conference: a value analysis of a hands-on surgical skill-building event

- Medical Education

- Brief Report

- Poor match rates of osteopathic applicants into ACGME dermatology and other competitive specialties

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Review Article

- Osteopathic model of the development and prevention of occupational musculoskeletal disorders

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Review Article

- Support for osteopathic manipulative treatment inclusion in chronic pain management guidelines: a narrative review

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- An analysis of research quality underlying IDSA clinical practice guidelines: a cross-sectional study

- Clinical Images

- Papillary fibroelastoma: an unexpected finding on the aortic valve

- Superior vena cava syndrome from extensive lung cancer

- Letter to the Editor

- New clinical research urgently needed for adjunctive OMT treatment in elderly patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Registering your research: What’s required?

- General

- Brief Report

- A survey on health professionals’ understanding of federal protections regarding service dogs in clinical settings

- Innovations

- Original Article

- The use of 3D printing for osteopathic medical education of rib disorders

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- Teaching and use of cervical high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulation at colleges of osteopathic medicine

- The Philadelphia surgery conference: a value analysis of a hands-on surgical skill-building event

- Medical Education

- Brief Report

- Poor match rates of osteopathic applicants into ACGME dermatology and other competitive specialties

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Review Article

- Osteopathic model of the development and prevention of occupational musculoskeletal disorders

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Review Article

- Support for osteopathic manipulative treatment inclusion in chronic pain management guidelines: a narrative review

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- An analysis of research quality underlying IDSA clinical practice guidelines: a cross-sectional study

- Clinical Images

- Papillary fibroelastoma: an unexpected finding on the aortic valve

- Superior vena cava syndrome from extensive lung cancer

- Letter to the Editor

- New clinical research urgently needed for adjunctive OMT treatment in elderly patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia