Abstract

In this article, I outline the need to theorise a Dialogic Ethical Criticism that maps the spectrum of real student readers’ interpretive responses to what Suzanne Choo calls the »referent other« (2021, 88). I start with a brief historical overview of the ethical praxis of literature instruction, from didactic to dialogic practices, and three key complementary (and sometimes overlapping) movements of ethically-oriented literature pedagogies, which I define as lessons or teaching units of literary texts where the text selection, instructional strategies, and interpretive focus – verbal and/or written – centres around the literary representation of the »referent other«, i. e. the »fictional other in the text who, as an imagined construct, makes reference and points to real others in the world undergoing similar forms of injustice« (ibid.). Based on these considerations, I highlight two practical challenges of enacting ethically-oriented literature pedagogies: The first relates to managing student resistance, as well as divergent and limiting responses. The second concerns balancing the tension of enacting a pedagogy of discomfort and the promise of a safe classroom space, and the risk of committing ethical violence on students. I then explain the lack of colligation between the field of ethical criticism in literary studies and empirical studies of ethically-oriented literature pedagogies concerning the ethical meaning-making of real readers.

Next, I offer an overview of the field of ethical criticism, drawing upon Suzanne Choo’s (2023) survey of the three key strands of ethical criticism: relational, analytical, and historical, showing how they are informed by an underlying cosmopolitan other-centric ethics. How can literature educators attend closely to the turn-by-turn realities of intersubjective interpretation of the referent other in the ethically-oriented literature classroom? Within the field of ethical criticism, I consider three existing dialogic practices that offer possible solutions: namely Wayne Booth’s ›coduction‹, Peter Rabinowitz’s ›lateral ethics‹ and Suzanne Choo’s ›dispositional routines‹. Although these three disparate and complementary practical concepts of ethical criticism do address the above limitations of ethically-oriented literature pedagogies, I argue that a clear gap remains, which shows that educators still need a practical theory of ethical criticism that can help them anticipate, strategise, and address the simultaneous and complex nuances of student responses when dialogically conversing about the referent other.

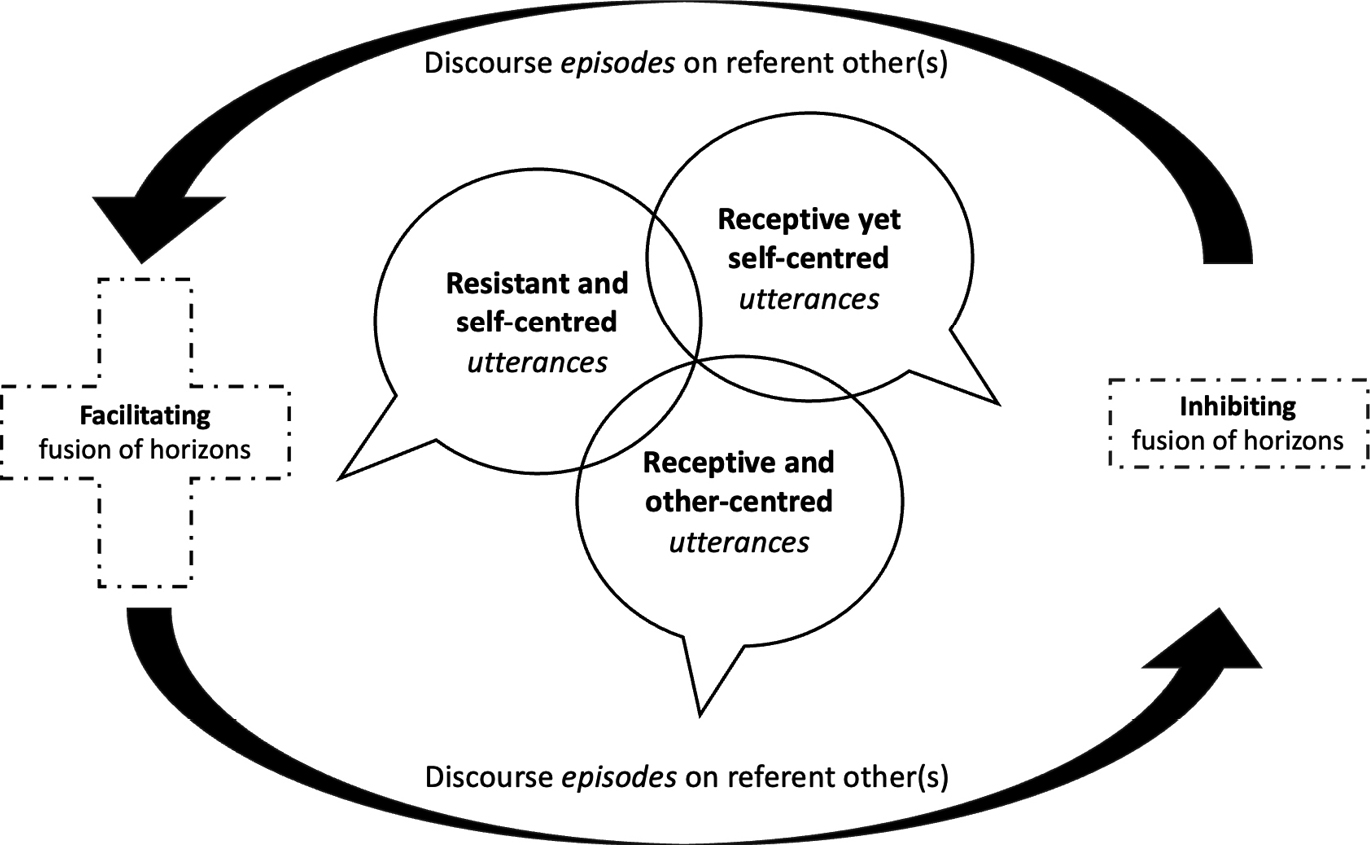

Following these overviews, I theorise what I have called a ›Dialogic Ethical Criticism‹ to look at how real interlocutors come together in interpretive communities of the classroom. I establish its fundamental tenets of Emmanuel Levinas’ ethical responsibility to the other, its awareness of the constant tension of representational violence in language, and its commitment to support ethical interruptions of one’s prejudices. To account for the ways real readers respond to the referent other and discursive conditions within a classroom’s lateral ethics, I combine Hans-Georg Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics and empirical studies of student responses to the referent other in classroom discourse to formulate the framework for a Dialogic Ethical Criticism. I show how despite Levinas and Gadamer’s fundamental differences in the ontology and epistemology of alterity, Gadamer’s concepts of prejudice, hermeneutic conversation, and the fusion of horizons reflect the ethical interruptions of one’s prejudices that students experience in classrooms. Here, I introduce a diagrammatic framework of Dialogic Ethical Criticism that helps explain the dialogic process of ethical utterances and episodes about the referent other in classroom interactions.

Using Gadamer’s dialectic of the I-Thou, I discern three orientations of student responses to the referent other: resistant and self-centred stances; receptive yet self-centred stances; and receptive and other-centred stances. I also present a preliminary taxonomy of how these stances can be expressed by drawing upon twelve empirical studies of secondary-level student responses to the referent other. I illustrate this taxonomy by applying it to a reading of a translated poem on migrant worker conditions during COVID-19 lockdowns in Singapore called »First Draft« by Bangladeshi poet Zakir Hossain Khokan. I then briefly explain my existing theorisation of Dialogic Ethical Criticism that adopts Gadamer’s concept of hermeneutic conversation to chart a preliminary taxonomy of discursive acts that either facilitate or inhibit the fusion of horizons between reader, text, and the referent other.

Finally, I contend that Dialogic Ethical Criticism can serve as a practical theory for literature educators to better discern the ethical stances of interpretive claims and to prepare for the practical challenges of navigating conflicting, controversial, and confounding interpretive claims by students. I comment on its implications for the moral development of adolescent students. I further propose that in the context of teacher education and professional development, educators can examine these ethical utterances and episodes about the referent other to sensitise themselves to the nuanced tensions of classroom discourse. While the generative framework of Dialogic Ethical Criticism may elide paralinguistic resources of meaning-making, or not fully accommodate classroom particularities across different contexts, ultimately it aims to serve the cause of what Choo (2024a) calls »hermeneutical justice«, one where applications of critical interpretive approaches are grounded in an ethics of truth-seeking, wisdom, and justice for the other (cf. 3 sq.).

1 The Ethical Praxis of Literature Instruction: From Didactic to Dialogic and Ethically Oriented Literature Pedagogies

Ethical orientations in literature instruction concerned with how humans negotiate values that influence one’s behaviour and conduct with others are not new. Didactic pedagogies have dominated the ethical praxis of teaching literature, framing students as passive recipients of moral, colonial, and humanistic values, beginning with Plato’s condemnation of tragedy’s emotional manipulation of audiences. In its early institutionalisation as a discipline in 19th-century India, literature was used to school colonial subjects in English values (Viswanathan 2015). This proclamation of English literature as cultural heritage – promoted by Matthew Arnold – was taken up by F. R. Leavis and colleagues in the 1930s, positing literature as a universal humanistic antidote to the modern world’s obsession with scientific rationality and productive efficiency (Goodwyn 2021; Leavis/Thompson 1933).

In the 1960s, the ›personal growth‹ model of literature instruction popularised by John Dixon (1969) after the 1966 Dartmouth Conference and the uptake of Louise Rosenblatt’s (1983) reader-response criticism in high school classrooms helped develop dialogic pedagogies of literature instruction, positioning students as active interpreters of meaning in literary texts. Both focus on the adolescent student reader’s desire for self-knowledge and personalised responses to texts in schools, opposing the New Critics’ deferential, technical, and text-centric approach. Rosenblatt’s student-centric pedagogy also recognised that »the teaching of literature inevitably involve[s] the conscious or unconscious reinforcement of ethical attitudes« (1983, 16).

From the 1980s, three complementary (and sometimes overlapping) movements of ethically-oriented literature pedagogies emerged in secondary and high school literature classrooms, which, as I argue, were put into practice as lessons or units on literary texts where the text selection, instructional strategies, and interpretive focus – verbal and/or written – centre on the literary representation of what Suzanne Choo calls the »referent other« (2021, 88). A referent other is the »fictional other in the text who, as an imagined construct, makes reference and points to real others in the world undergoing similar forms of injustice« (ibid.). In short, the interpretive focus of ethically-oriented literature pedagogies foregrounds the experiences and subjectivities of characters and personas who are marginal(ised) or othered in a given social context.

First, ethically-oriented literature educators seek to expose students to marginal groups and foreign others by enacting various multicultural, world, and cosmopolitan literature pedagogies. Collectively, they aim to increase cultural awareness both locally and globally, and cultivate empathy and openness in students toward the other, by introducing them to texts about those deemed different or marginalised. Multicultural literature started to gain prominence in US, Australian, and British secondary-level schools in the 1980s (Gunew 1987; Johnstone 2011; Norton 1990) with many studies of classroom practices (Loh 2009). World literature and cosmopolitan literature pedagogies at secondary level were enacted in the 2000s and 2010s respectively, in response to increasing polarisation arising from terrorism (Qureshi 2006) and globalisation, where teachers aimed to sensitise often apathetic students to local and global socio-political concerns (Choo 2017; Gauci/Curwood 2017).

A second movement encouraged students to identify and critique ideological beliefs that perpetuate injustice and discrimination through an array of critical literacy pedagogies, which Allan Luke (2012) defines as an »overtly political orientation« (5) towards texts that »analyze, critique, and transform the norms, rule systems, and practices governing the social fields of everyday life« (ibid.). Literature educators have developed and applied critical antiracist pedagogies to disrupt dominant racial ideologies, including Critical Race Theory and Critical Whiteness Studies (Borsheim-Black/Sarigianides 2019; Dyches/Thomas 2020), Critical Race English Education (Johnson 2018), as well as critiquing dominant cultural values within the (English) literary canon (Dyches 2018).

A third movement applies culturally relevant and social justice pedagogies to affirm and present positive portrayals of oppressed individuals and groups while addressing taboo and overlooked injustices. For one, educators have aimed to increase the representation of aboriginal literature (Bacalja/Bliss 2019; Wiltse/Johnston/Yang 2014) and culturally relevant literature to recognise the rich funds of knowledge and experience of minority group students (Ladson-Billings 2021). Among others, literary texts are used as conduits to confront taboo topics such as sexual trauma (Malo-Juvera 2014) and destigmatising LGBTQ discrimination (Blackburn/Clark/Nemeth 2015).

What these complementary and overlapping movements of ethically-oriented literature pedagogies share is their practical commitment to engage students in dialogic conversation about the other within the classroom and social contexts. However, these pedagogies raise several challenges in enactment.

2 Practical Challenges of Enacting Ethically-Oriented Literature Pedagogies

Firstly, empirical classroom research of ethically-oriented literature pedagogies in Anglophone contexts shows that teachers face challenges in managing student resistance as well as divergent and limiting responses. Often, students from a dominant group express discomfort and resentment towards worldviews from teachers or peers that challenge their prevailing beliefs of those who are different (Borsheim-Black 2015; Dyches/Thomas 2020; Yandell 2008). Students might also enact dialogic but uncritical discussions at small-group and whole-class levels, reinforcing prejudicial or deficit notions of the referent other. Pre-assigned discussion roles might be used procedurally rather than critically, or reinforce hierarchical roles that inhibit dialogue (Lloyd 2006; Thein/Guise/Sloan 2011). This disparity arises when educators focus on eliciting student responses to literary representations of otherness based on New Criticism and/or personal response, without either problematising students’ self-oriented responses or consciously facilitating an other-oriented interpretive stance (Beach 1997; Ginsberg/Glenn 2019; Thein/Guise/Sloan 2011).

Secondly, ethically-oriented literature educators struggle to balance the tension of enacting a »pedagogy of discomfort« and the promise of a »safe classroom space« (Zembylas 2015, 164–167). Megan Boler (1999) posits that a ›pedagogy of discomfort‹ assumes that discomforting feelings are crucial in unsettling students’ »cherished beliefs and assumptions« (176) of normative practices that perpetuate social inequities, to induce individual and social transformation. Concurrently, Davis and Steyn (2012) challenge pedagogical assumptions of ensuring classroom safety and centring personal experience as prerequisites for social justice education. Dominant-group students might abuse the promise of a safe space because »safety is too often mistaken for comfort« (ibid., 33) or freedom of speech, leading them to belittle oppressed groups in their personal responses without reflecting on their privileged positions. Here, literature educators may struggle or choose not to intervene following prejudicial comments and leaving them unchecked, owing to a lack of efficacy in facilitating ethically-charged dialogue, or defaulting to the premise of classroom safety and respecting all opinions (Bender-Slack 2010; Mohamud 2020). Minority-group students have experienced harm from teachers who introduce difficult topics such as racism, LGBTQ+, immigration, and xenophobia in classes on the premise of exposing the reality of injustice in society (Homrich-Knieling 2020). They experience what Judith Butler (2005) – drawing from Theodor Adorno’s conception – terms ›ethical violence‹, which occurs when ethical norms are imposed on individuals via ethical claims to universality (e. g., democracy, justice) while ignoring existing social conditions and failing to offer practical ways to enact them (cf. 5 sq.). Regardless of how noble a teacher’s intentions are, »how does the teacher make sure that marginalized students are not forced to be representative of a homogenized group or privileged students are not forced to make their transformation ›evident‹ in public?« (Zembylas 2015, 170).

These challenges raise the need to theorise students’ dialogic and ethical responses to the other in literary texts. In so doing, I address the hitherto »little attempt to place the field of ethical criticism in colligation with existing studies that examine student responses to ethically oriented Literature pedagogies« (Nah 2024). While both scholars of ethical criticism in literary studies and secondary-level literary educators have advocated the personal and social affordances of reading ethically since the 1980s, these pedagogical challenges raise a conceptual gap between literary theorists who often write about ethical effects on hypothetical readers, and existing empirical research by literature educators who examine student responses in specific classroom contexts, albeit without making theoretical connections to ethical meaning-making (Nah 2024).

3 Three Key Strands of Ethical Criticism: Relational, Analytical, Historical

In this section, I outline three major strands of ethical criticism that conceptualise approaches to ethical meaning-making, before highlighting three dialogic practices that scholars of ethical criticism have proposed for intersubjective meaning-making between multiple interlocutors, which are relevant to ethically-oriented literature pedagogies.

As a field, ethical criticism is an »interpretive paradigm that explores the nature of ethical issues from their considerable roles in the creation and interpretation of literary works« (Womack 2006, 167), and does not have a unifying theoretical or methodological approach (Eaglestone 2011). Marshall Gregory observed that ethical criticism is not new, dating from Plato’s attack on tragedy to 19th-century Victorian critics, only to be neglected in the mid-20th century (Gregory 2010). Robert Eaglestone (2011) observed two distinct intellectual trajectories that informed the (re)turn of ethical criticism since the 1980s. The first follows the intense growth and later disillusionment of literary theory that pushed political and ideological critiques of literary texts from a multitude of intersections of gender, sexuality, class, race, (post)colonialism, etc., along with deconstructionist and postmodernist movements that insisted on the radical indeterminacy of meaning (cf. ibid., 582). Critchley (2014) explains how these critical literary theorists were fundamentally concerned with how language normalised ethical issues of power, privilege, and inequality. Second, the return of ethical criticism was catalysed by two convergences between ethical philosophy and literature as a site for ethical reflection: The first relates to the 1983 winter issue of New Literary History on »Literature and/as Moral Philosophy« yoking literature and moral philosophy, introducing newer voices and generating conversations on ethical criticism (Nussbaum 2009). Elsewhere, Anglophone literary critics discovered Emmanuel Levinas’ ethical philosophy of prioritising responsibility to the other and began drawing connections to literary criticism, partly through Derridean critics such as Derek Attridge, and scholars examining trauma (cf. Eaglestone 2011, 584).

Most recently, Suzanne Choo (2023) surveyed the field of ethical criticism and charted three major strands of ethical criticism which she calls ›relational ethical criticism‹, ›historical ethical criticism‹ and ›analytical ethical criticism‹ respectively. First, Choo identifies Wayne Booth and Martha Nussbaum as catalysts of what she terms ›relational ethical criticism‹, where »engagements with literature enact ethical relationships among readers, authors, fictional characters, and their real-world referents« (ibid., 29). For Booth, stories and their implied narrators offer companionship to readers, which is implied by his use of the metaphor of books as friends (Booth 1980). He explains how readers can relate to the nature of the friendship offered by a book’s implied narrator, while critically discerning this relation by evaluating the characters’ (and text’s) values, justifications, and coherence (cf. Booth 1988, 169–198, 265–291). Nussbaum (1997) extends this text-as-friend view from a personal to cosmopolitan level by grappling with the ethical question of how one should live as a citizen and social being (cf. 90). Similarly, by relating with narrators, characters, and stories, readers can cultivate their »narrative imagination« (ibid.) and civic consciousness as they develop their »sympathetic responsiveness to another’s needs, and understand the way circumstances shape those needs while respecting separateness and privacy« (ibid.).

In this context, Choo outlines the strand of ›historical ethical criticism‹ (2023) emerging from Chinese literary scholars who aimed to distinguish it from ›western‹ ethical criticism. Founded as ›Ethical Literary Criticism‹ by Nie Zhenzhao, Choo refers to this strand as ›historical ethical criticism‹ to highlight how it positions the reader to »honour the ethics of the text and its various dimensions« (ibid., 32). Scholars from this movement have critiqued relational ethical criticism’s tendency to impose presentist values when interpreting texts with their personal responses (Nie 2015). Instead, Nie holds that ethical criticism should interpret the text’s ethics in its historical context for readers’ ethical insight. Nie seeks to »conduct an objective ethical analysis and clarify various social life phenomena in literature«, one which »requires the critic to be placed in the historical period of the literary work and act as an agent of a character in the particular situation and context of the literary work – a defense lawyer of the character, that is to say – to empathize deeply with the character« (2021, 192). However, while Nie asserts that »the ethical value of literature is historical, stable and objective, regardless of the changes undertaken in today’s moral principles« (2015, 100), Choo surmises that one limitation of historical ethical criticism lies in how it »promotes a positivistic and romanticized view of history« (2024b, 178) where ethical critique remains contained within the text so that an author’s contextual assumptions and ethical bias are not sufficiently interrogated.

Choo’s critique of historical ethical criticism is informed by a third strand of ›analytical ethical criticism‹ where scholars are »driven by a cosmopolitan ethical analytical approach arising from a concern about the propensity for discourse to perform hermeneutical violence and objectification of the other« (2023, 31). This skeptical stance connects literary theorists informed by the ideological critique of post-structuralists and postmodernists together with the school of critics drawing inspiration from Levinas’ philosophy of alterity. Here, Choo cites Derrida’s later work on cosmopolitan ethics and hospitality, Butler’s analysis of the hermeneutics of violence and non-violence, and Spivak’s conceptions of radical alterity and planetarity as key examples (cf. 30). At one level, relational and analytical ethical criticism both share concerns with the other. However, Choo (2023) observes that the latter problematises the former’s assumptions of empathetic imagination and affiliation, pushing readers to be more critically reflexive with the referent others they do and do not empathise with in literary texts, grounded by a call for justice to recognise the fullness of the other’s humanity (cf. 31 sq.). Even so, Nie (2015) cautions against the risk of relegating the literary text as a secondary instrument serving prefigured ideological systems of thought (cf. 87).

Taken together, Choo surmises that despite their differences, the three strands remain informed by an underlying cosmopolitan, other-centric ethics that de-centres prioritising the reader’s response and the text’s aesthetics – the latter two which have dominated pedagogical practices in the 20th and 21st century (cf. Choo 2023, 33). To connect such a ›cosmopolitan ethical criticism‹ with literature education is to »[de-centre] the reader and the interpretive community’s egotistical impulses to claim knowledge of the other« such that »a multiplicity of views beyond any monolithic cultural, ideological, identity perspective becomes possible« (ibid., 41).

Yet in practice, how can literature educators attend closely to the turn-by-turn realities of intersubjective interpretation in the ethically-oriented literature classroom to open ethical meaning-making on the other (Nah 2024)? Here, I propose the need to conceptualise a ›Dialogic Ethical Criticism‹ that accounts for such intersubjective ethical meaning-making. In the following section, I offer a short overview of three existing but disparate dialogic practices suggested by three ethical critics that are relevant to ethically-oriented literature pedagogies.

4 Mapping a Theory of Dialogic Ethical Criticism

4.1 Existing Dialogic Practices in Ethical Criticism

The first dialogic practice of ethical criticism is Wayne Booth’s term ›coduction‹ where he theorises how real readers can engage in dialogic acts of interpretation to help circumvent individual biases of ethical meaning-making in textual interpretation: »When [coduction] is performed with genuine respect both for one’s intuitions and for what other people have to say, it is surely a more reasonable process than any deduction of quality from general ethical principles could be« (Booth 1988, 76).

A neologism from co (»together«) and ducere (»to lead, draw out, bring, bring out«), Booth outlines how practising a dialogic openness with an interlocutor’s alternative perspective to one’s tentative interpretations posits an embodied practice of peer review with multiple, reliable interlocutors, where »the validity of our coductions must always be corrected in conversations about the coductions of others whom we trust« (ibid., 73). He illustrates how his late colleague Paul Moses precipitated his interpretive shift on Huckleberry Finn »from untroubled admiration to restless questioning« (ibid., 477 sq.). Unsettling fellow white colleagues, Moses spoke up as the lone black faculty in Booth’s English department, problematising Mark Twain’s white liberal depiction of slavery’s consequences, the treatment of liberated slaves, and how slaves were expected to behave to whites (cf. ibid., 3). In literature education, Sheridan Blau (2003) adopts Booth’s notion of coduction to advocate for reading as »a social process, completed in conversation […] students will learn literature best and find many of their opportunities for learning to become more competent, more intellectually productive and more autonomous readers of literature through frequent work in groups with peers« (54). Co-duction’s emphasis on genuine respect in conversation for the referent other and one’s interlocutors can help mitigate concerns of ethical violence arising from mismanaged dialogue.

Second, Peter Rabinowitz (2010) outlined the notion of ›lateral ethics‹ to account for the ethical considerations of teaching ethically problematic literary texts within specific classroom dynamics – defining ethics as both acts and relations between people in a specific context, and literary reading as a social activity (cf. 159). Reflecting on his refusal to teach Pauline Réage’s pornographic classic The Story of O in an undergraduate module, Rabinowitz explained that rather than personal, practical, or historical considerations, it was the intricate responsibility of negotiating the live classroom dynamics in teaching the text that informed his choice (cf. ibid., 158). He argued we cannot compartmentalise our private aesthetic response to texts from our public social response in a classroom, for »reading has a lateral dimension that involves groups of people in particular situations, groups with which we have ethical relations that are only secondarily connected to the ethics of the author-text-reader relationship« (ibid., 159, emphasis original). This leads Rabinowitz to first ask »what’s the ethics of requiring someone to read the text?« (ibid., 163, emphasis original). Text selections imply a teacher’s value judgements about the students and institution they engage with, which warrants justification should students challenge the teacher’s choice. Next, Rabinowitz asks »what’s the ethical effect of requiring my students to read the novel in this particular group?« (ibid., emphasis original). Text selection criteria must include considering whether a class demographic and context can cultivate »an environment where students can be honest and open as they discuss serious and controversial issues« (ibid., 164). Otherwise, without conscious intervention, texts may privilege some students and engender anxiety in others. Rabinowitz’s notion of lateral ethics speaks to an ethically-oriented educator’s balancing act of enacting a pedagogy of discomfort to unsettle students’ preconceived notions whilst ensuring a safe classroom space for dialogic conversations about otherness.

Third, Suzanne Choo conceptualises dispositional routines for the literature classroom to cultivate students’ ethical values of empathy, hospitality, and responsibility. Choo begins by establishing a cosmopolitan literature pedagogy framework, anchored in Levinasian ethical philosophy that »encourages in students a commitment towards understanding others, particularly those who are in the minority and those who hold different beliefs from themselves« (2021, 111). Crucially, Choo recognises that literature pedagogies are enacted in schools where students risk being socialised into obedience through school rules and routines. To extend students’ concern for the other beyond authority figures to include »diverse others in the world« (ibid., 114), she connects phronesis (practical wisdom as determined by character dispositions) with Confucian concepts of humaneness (仁, rén) – of cosmopolitan love to one’s family, community and distant others, and the practice of rituals of respectful interaction (礼, lǐ) to facilitate the development of ethical dispositions.

Choo recommends two conscious social routines to cultivate ethical values: »listening routines« (ibid., 129–131) and »bridge-building routines« (ibid., 131–134). Listening routines help »[disrupt] the tendency to become absorbed in one’s ideas« (ibid., 130) to practice an embodied openness to others. This is exemplified by a Grade 10 Literature class in Singapore, where students in groups actively listen as a peer shares for a minute uninterrupted, followed by 30 seconds of silent written reflection. Students are also instructed to build on peers’ comments and affirm others’ insights in group annotations, hence developing a classroom culture of respect and openness to peers’ responses. Next, bridge-building routines can be set up in small-group discussions where students from different backgrounds are invited to share about their experiences on a given ethical concern while witnessing and appreciating each other. Students practise hospitality by valuing differences and suspending judgement which »facilitate[s] relational learning and ways to foster deeper commitments to one another« (ibid., 131). Through these routines, students can create conducive environments for respectful coduction to take place, and foster greater trust between classmates to approach discomforting issues.

Although these three disparate and complementary practical concepts of ethical criticism address the challenges of teaching literature with an ethical orientation, educators lack a practical theory of ethical criticism that can help them anticipate, strategise and address the simultaneous and complex nuances of student responses when dialogically conversing about the referent other. For one, Booth’s notion of coduction does not catalogue the different types of discursive acts and conditions that facilitate or inhibit ethical meaning-making about the other in dialogic discussions. Similarly, Rabinowitz’s notion of lateral ethics does not illuminate the range of positive and problematic ethical responses toward the other from students. Lastly, Choo’s dispositional routines, while offering structure and repeated practice, may remain subject to student resistance. All three practices risk students limiting their responses to perceived ›emotional rules‹ of how teachers expect students to share their responses (Zembylas 2002), or when minority or sensitive political opinions are silenced to preserve harmony and avoid open disputes with others (Poyas/Elkad-Lehman 2020).

4.2 Towards a Theory of Dialogic Ethical Criticism

In the following, I will further develop what I have termed ›Dialogic Ethical Criticism‹ (Nah 2023b) to examine how real interlocutors come together in interpretive communities of the classroom. Dialogic Ethical Criticism maps the spectrum of real (student) readers’ interpretive responses to the referent other – from resistant to receptive, self-centred to other-centred – while charting »dialogic acts that can facilitate and inhibit possibilities of ethical meaning-making« (ibid., 5). Grounded in empirical studies of classroom discourse, I trace its roots in Levinasian strands of ethical criticism and explain how Hans-Georg Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics informs the framework of Dialogic Ethical Criticism.

On Levinasian Ethical Responsibility

Dialogic Ethical Criticism begins with Levinasian notions of ethical responsibility to the other. Firstly, it accepts that one is faced with an integral responsibility towards the other that originates even before one comes into being, which »commands me and ordains me to the other […] it provokes this responsibility against my will, that is, by substituting me for the other as a hostage« (Levinas 2006, 11). Here, truly encountering the other means to confront what Levinas calls »the face […] which resists possessions, resists my powers« (Levinas 2007, 197) and cannot be fully grasped by the self.

Second, Dialogic Ethical Criticism recognises the constant state of tension of representational violence in language. Levinas’ concern is that understanding the other results in »a reduction of the other to the same by interposition of a middle and neutral term that ensures the comprehension of being« (ibid., 43). Speaking of the other in language paradoxically limits their subjectivity as seen in the concepts of the ›Saying‹ and the ›Said‹ which exist in a constant state of tension. The ›Saying‹ is the unquantifiable subjectivity of »the unqualifiable one, the pure someone, unique and chosen« (Levinas 2006, 50) embodied in being, who forestalls any fixed meanings of their identity that I may limit and impose on them. Yet the ›Said‹ refers to the moment when the saying enters into language and the act of naming occurs, also known as ›thematisation‹. Eaglestone (1997) reconciles this contradiction for literature by advocating a reflexive understanding of language’s limitations, using language’s ability to continually interrupt itself in representation.

Third, Dialogic Ethical Criticism supports ethical interruptions of one’s prejudices by mapping a spectrum of interpretive utterances and episodes that occur in the discursive space about the other. Extending Eaglestone’s notion of interruption is Derek Attridge, who warns of complacent and presumptive practices of reading texts that dismiss one’s responsibility to the other: »[a] reading that glides over the work’s challenges, or converts otherness to sameness by imposing a common meaning on an uncommon one, or that disregards the context within which the work is being read, is refusing to accept the responsibility being demanded« (2015, 121). Ideally, individuals learn to enact a »responsible reading« of the other, which means to »find a means to destabilize or deconstruct the set of norms and habits that give me the world« (ibid., 71) and »with an openness to that which one has never encountered before« (ibid., 72 sq.). However, Amiel-Houser and Mendelson-Maoz (2014) caution against a universalist conception of empathetic readings which can easily disregard examples of distress not conventionally recognised as suffering, and »risk ignoring the concrete circumstances and the radical uniqueness of the sufferer« (204).

Synthesising Levinasian Ethics and Gadamerian Hermeneutics

Not only does Dialogic Ethical Criticism map the ways in which real readers respond to the referent other; it also accounts for the discursive conditions and acts (including and beyond ›coductions‹ and ›dispositional routines‹) within a classroom’s ›lateral ethics‹ that facilitate and inhibit students’ movement along the continuum of ethical responses, be they receptive or resistant to the other. It also must account for how students’ and teachers’ »idioculture« influence one’s interpretation of the other – of one’s »complex of attitudes, aptitudes, habits of thought and feeling, and pieces of knowledge formed as the impress of the broader culture around me in a constellation that includes traces of my past cultural experiences« (Attridge 2015, 53).

Next, I introduce Hans-Georg Gadamer’s concepts of hermeneutical understanding to further develop the philosophical foundation of Dialogic Ethical Criticism. Gadamer’s hermeneutical model of understanding holds that our consciousness is constituted by historical and cultural contexts in language when we set out to interpret texts. For him, interpretation is an intersubjective act, given that our experiences are inherently constituted in language, that »we are always already at home in language, just as much as we are in the world« (Gadamer 2008, 63). David Haney highlights the conceptual alignment between Gadamer and Levinas, where the former’s case for the literary text’s autonomy maintains »a kind of ethical autonomy that imposes a claim stronger than that of an ordinary partner in the hermeneutical conversation«, such that the literary text »begins to resemble the nonreciprocal Levinasian other« (Haney 1999, 40). Although Frimberger (2023) recognises a fundamental ontological difference – while Gadamerian alterity remains bound within a common world and humanity and potentially intelligible in the back-and-forth of dialogue, Levinasian alterity is existentially unassailable (cf. 285 sq.) –, Gadamer’s accommodation of strangeness in interpretation through dialogue is more applicable to students’ encounters with texts in literature classrooms.

Gadamer (2013) points out that prejudices – »judgement[s] that [are] rendered before all the elements that determine a situation have been finally examined« (283) – are inevitable. This aligns with Attridge’s ›idioculture‹ and leads Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics to stress the need for an interpretive relation between self and text, self and other as one based on dialogical principles. For Gadamer, interpretive truth is manifest through authentic dialogue (or hermeneutic conversation), characterised by constant questioning and answering with a text. To understand a text with its embedded historicity, the reader centres the text, while being receptive to the other’s voice, and the preconceptions (or ›prejudices‹) they bring to bear: »The important thing is to be aware of one’s own bias so that the text can present itself in all its otherness and thus assert its own truth against one’s own fore-meanings« (Gadamer 2013, 282).

I use Gadamer’s (2013) notion of the »fusion of horizons« where we »regain the concepts of a historical past in such a way that they also include our own comprehension of them« (382) to theorise how students can extend their original horizons of understanding to fuse with the possibilities offered by the text. With the pedagogical aim of expanding students’ horizons of ethical understanding, I amplify Xu Wenying’s (1996) connection of Gadamerian hermeneutics with the teaching of multicultural literature. For Xu, Gadamer’s ›fusion of horizons‹ can help teachers remind students that »enabling themselves to understand radically different worlds does not mean that they must embrace these other ways of living or forfeit all ability to criticize aspects of these ways of living« (Xu 1996, 52). Xu’s epistemological stance reflects the ideological reassurance students need when experiencing ethical interruptions of their prejudices in classrooms.

A Theoretical Framework for Dialogic Ethical Criticism

A Conceptual Framework of Dialogic Ethical Criticism

To illustrate the framework of Dialogic Ethical Criticism, I synthesise 12 empirical studies of student responses from Anglophone contexts to ethically-oriented literature pedagogies (Beach 1997; Borsheim-Black 2015; Boyd 2002; Dyches/Thomas 2020; Ginsberg/Glenn 2020; Louie 2005; Lloyd 2006; Nah 2023a; Thein/Guise/Sloan 2011; Thein/Sloan 2012; Xerri/Agius 2015; Yandell 2008) with Gadamer’s concept of the I-Thou relation in hermeneutic experience to explain individual stances to the other. Next, I apply his notion of hermeneutic conversation that facilitates and inhibits one’s fusion of horizons (Nah 2023b). Per Figure 1, my unit of analysis of classroom discourse follows what I call ›ethical utterances‹ and ›ethical episodes‹. The former extends what Marshall/Smagorinsky/Smith (1995) call ›utterances‹ – of a remark or group of remarks on a common subject – to that of the referent other. The latter extends what are known as ›episodes‹ to denote a series of turns that relate to the referent other.

4.3 Resistant to Receptive Stances: Three Orientations of Student Utterances About the Other

From Gadamer’s I-Thou relations, I discern three stances of student responses to the referent other where scholars and educators can chart the spectrum of resistance to receptive stances students express in their interpretive utterances. He posits the ›I-Thou‹ relationship across three forms of dialogical encounters, characterised by varying degrees of nondomination, mutuality, and non-judgemental stances. Figure 1 illustrates how these different stances can occur simultaneously in a single pedagogical event, uttered by the same or different students in small-group and whole-class dialogic settings.

To illustrate these stances, I use a preliminary literature review of 12 empirical studies, and apply them to conjecture possible student responses to a reading of the poem »First Draft« by Bangladeshi poet Zakir Hossain Khokan, translated from Bengali by Debabrota Basu.[1] Written from a communal narrator’s voice, the poem illustrates the pervasive fear, confusion, and vulnerability of navigating an extended lockdown on migrant workers in cramped dormitories in Singapore, separate from the public during the COVID-19 pandemic. I chose this text as it not only centres the voice of the subaltern other but also embodies a dialogic intertwining of different perspectives, concentrated in a single speaker. The textual construction of »First Draft« exemplifies what Mikhail Bakhtin (1981) defines as a ›hybrid construction‹, where »there is no formal – compositional and syntactic – boundary between these utterances, styles, languages, belief systems; the division of voices and languages takes place within the limits of a single syntactic whole, often within the limits of a simple sentence« (305), and where the speaker presents a heteroglossia of experiences and beliefs by different stakeholders invested in the condition of migrant workers.

Resistant and Self-Centred Stances

First, we consider resistant and self-centred stances where students objectify the other or refuse to acknowledge the fullness of the other’s particularities and subjectivity. I draw from Gadamer’s first I-Thou relation where an individual is »purely self-regarding« (2013, 367) and generalises knowledge to »discover typical behaviour in one’s fellowmen and […] make predictions about others on the basis of experience« (ibid., 366). In these stances, students ignore both their own and/or the texts’ historicity while appraising the other. Instead, they show a naïve faith in objectivity, flattening and completely »ignore the specificity of the ›other‹« (Warnke 2002, 92), disregarding Levinas’ (2007) warning against »the imperialism of the same« (87).

As indicated by empirical studies, this stance can manifest in several ways when applied to interpreting »First Draft«. First, students from dominant groups can express discomfort and/or resentment at alternative perspectives that challenge their prevailing beliefs of the other (Beach 1997; Dyches/Thomas 2020; Yandell 2008). Students might insist that migrant workers are dirty and dangerous, greedy and rowdy – and bristle when called out for these prejudices, which they instead defend and claim as facts. Similarly, students might protest against perceived expectations of political correctness from their teacher (Thein/Sloan 2012) and thus resist calls to respond politely, where offensive language describing migrant workers is disallowed, claiming it restricts their freedom of speech in discussing the text. Third, students might express xenophobic fears and criticisms of the other (Xerri/Agius 2015) – claiming that male migrant workers threaten Singaporeans’ safety, especially women and girls, or are potential disease carriers on public transport. Fourth, students might practise victim-blaming, framing the other as responsible for their suffering (Lloyd 2006; Thein/Sloan 2012). Students might point out that the workers chose to seek work in Singapore and hence should be prepared to accept the realities of living in dormitories. Fifth, students might minimise the other’s suffering by dismissing the critiques of privilege as complaints (Dyches/Thomas 2020). When the speaker remarks »The state is applauded for its effort/They join the state in singing songs of praise« (Khokan), students might argue that migrant workers have nothing to complain about or fear since the Singapore government consistently reports on keeping death rates low despite high infection rates by taking swift measures and providing extensive free healthcare provisions for them (Ministry of Health, Singapore).

Receptive yet Self-Centred Stances

Secondly, students may adopt a stance that is receptive to the referent other, but ultimately still self-centred, taking the self as a referential basis to know the other: »one claims to know the other’s claim from his point of view and even to understand the other better than the other understands himself« (Gadamer 2013, 367). In Gadamer’s second I-Thou relation, this receptive yet self-centred stance presumes that one is able to overcome any historical, temporal, or cultural differences, allowing one’s current prejudices to prevail, where »the claim to understand the other person in advance functions to keep the other person’s claim at a distance« (ibid., 368). Warnke (2002) explains that »this experience of the thou claims an empathy with others that presumes to understand them better than they understand themselves« (92). Put differently, the individual assumes that empathetically identifying with the other affords them a definitive understanding of the other, without checking for their preconceived notions. Here, a Levinasian caution against universalising empathetic responses to the other is needed, recognising that the desire for empathetic imagination and identification risks committing epistemic violence on the other’s subjectivity (Amiel-Houser/Mendelson-Maoz 2014).

Similarly, as suggested in existing studies, students can express this stance in several ways, which is further posited in discussing »First Draft«. First, students can pity the other as suffering victims of injustice while still being suspicious (Borsheim-Black 2015; Xerri/Agius 2015). Students may pity migrant workers for their living conditions and enforced regulations that are outside their control during COVID-19, but still suspect that they are somehow responsible for their hygiene, citing the poem’s stanza on their aversion to the using and cleaning of toilets. Second, students may accept the other, but only as a collective entity at a distance (Ginsberg/Glenn 2020). Given the speaker’s repetition of the collective pronoun ›they‹, students may positively address migrant workers as a community but with little individuality and one that exists outside students’ reality, thereby reflecting and reinforcing the spatial marginalisation of workers’ dormitories in Singapore. Third, students can romanticise the other’s marginal condition (Thein/Guise/Sloan 2011), positioning them as the noble, hardworking poor coming from poverty to a first-world country, when in reality many workers themselves have educational qualifications and are skilled. Fourth, students might express self-serving gratitude and appreciation for the privileges of living in a first-world country (Louie 2005) from the same juxtaposition of their lives with the workers. Conversely, students might respond with personal distress, where »one observes another person in distress and reacts by becoming distressed himself […] typically engag[ing] in self-directed behaviours designed to alleviate their own discomfort« (Coplan 2011, 12). Here, students’ self-oriented perspective taking may manifest as guilt or shame at newly realising their privilege and/or the other’s suffering (Beach 1997; Xerri/Agius 2015), especially as they perceive the unfairness of living in relative shelter and comfort with their families compared to the migrant workers.

Receptive and Other-Centred Stances

Lastly, students can adopt a receptive and other-centred stance in apprehending the referent other. According to Gadamer, it is only in the third dialogic I-Thou relationship that genuine understanding of the other can emerge, when one does »not to overlook his claim but to let him really say something to us« (Gadamer 2013, 369) and the self remains open to the other’s claims without infringement. This form of openness also requires »recognizing that I myself must accept some things that are against me, even though no one else forces me to do« (ibid.), thus exemplifying the hermeneutical experience which allows for the other to speak on their terms to the self without interruption or violation. Here, the dialogical relationship avoids the objectification and self-oriented forms of understanding the other in the first two I-Thou relations. Instead, the individual encounters alterity as an involuntary demand that cannot be anticipated or assimilated into pre-existing categories. This recalls Levinas’ (2007) conception of the primary ethical relation, where the understanding of the other must necessarily resist full comprehension, and include a radical openness to what the other can teach us: »[The other’s] alterity is manifested in a mastery that does not conquer, but teaches« (171).

Students may express this stance in several ways, which can be further illustrated using the poem »First Draft«: Firstly, students might validate the other’s suffering, especially with circumstances they do not have control over (Lloyd 2006; Xerri/Agius 2015) after learning about the impossibility of social distancing measures in dormitories and the hypocrisy of authorities in requiring them to wear masks during the pandemic while not giving them any. Second, students can question dominant ideologies and power relationships that oppress the other (Dyches/Thomas 2020), by affirming and further developing the speaker’s critiques of the government and employers that »company and state feed on each other« (Khokan). Third, students might resist the single story about the other’s community (Ginsberg/Glenn 2020), especially that of victimhood, by questioning the tone-policing of workers’ voices by »literary folks and intellectuals« who encourage them to express themselves »but emphasise that their art should be calm and not explosive« (Khokan). Fourth, students might show an increased openness to the other after acquiring new knowledge (Ginsberg/Glenn 2020) about the migrant workers’ conditions and grow more welcoming of them outside of school. Fifth, students might affirm the other by contextualising the implications of the speaker’s tone (Nah 2023a), especially in the cumulative indignation, defiance, and resentment of the speaker in »First Draft« in reflecting the fear of migrant workers in extended lockdown.

4.4 Facilitating and Inhibiting Fusion of Horizons

The framework of Dialogic Ethical Criticism in Figure 1 extends my initial framework (Nah 2023b) and encapsulates the continual dialogic process of ethical utterances and episodes about the referent other. The semi-circular arrows that encircle the three stances of utterances connect the plus and minus signs which signify the »discursive conditions of classroom interactions that help facilitate or inhibit students’ ethical possibilities of meaning-making to move towards a fusion of horizons with the otherness depicted in texts« (ibid., 7) I previously developed. In short, I adopt Gadamer’s concept of hermeneutic conversation, via his elaboration on the logic of question and answer (cf. Gadamer 2013, 372–76), to chart a set of positive and negative valences in a preliminary taxonomy of discursive acts that either facilitate or inhibit the fusion of horizons between reader, text, and the referent other (Nah 2023b).

5 Discussion and Recommendations

In the present time of heightened polarisation across political, ethnic, religious, and other ideological lines, the function of reading literature to cultivate empathetic thinking for the other and dialogic understanding across individuals of different positionalities of other cultures, ethnicities, or social standings is more crucial than ever, especially for adolescents growing up while navigating an array of ideologically driven content online. A dialogic and ethically-oriented literary education can contribute to adolescent students’ moral development and examine what Lawrence Kohlberg (1981) calls »conventional morality« (18) where students are primarily concerned about acting in ways that measure up to others’ expectations. Since the 1980s, studies of literary education have integrated Kohlberg and Piaget’s stages of moral deliberation and judgement to explore and help cultivate students’ capacity to dialogue and consider other perspectives in the classroom (Spinner 1989; 2022). Yet Spinner (1989; 2022) cautions that attempts to assign students and texts to Kohlberg’s stages of moral development can be problematic because they risk creating rigid pedagogical practices where students learn that teachers desire certain moral types of argumentation. Instead, teachers should use dialogic discussion and text selection to open up ethical meaning-making opportunities for students. Furthermore, Kohlberg acknowledges that the mere »awareness of value conflict is not enough to stimulate movement toward principled morality« (1981, 239), which empirical studies of ethically-oriented literature instruction corroborate in the troubling finding that long-term transformative impacts on students’ ethical dispositions after engaging with literary texts are not guaranteed (Boyd 2002; Choo 2021; Ginsberg/Glenn 2020; Nah 2024; Thein/Sloan 2012; Xerri/Agius 2015).

Dialogic Ethical Criticism serves as a practical theory for ethically-oriented literature educators to discern the ethical stances of interpretive claims and to prepare for the pedagogical challenges of navigating conflicting, controversial, and confounding interpretive claims by students. Applied to teacher education and professional development, educators can examine these ethical utterances and episodes about the referent other to sensitise themselves to the nuanced tensions of classroom discourse. Where students are resistant or reserved, educators can heed Zembylas’ recommendation to exercise ›strategic empathy‹ by withholding their ethical judgement on students’ interpretive claims, and teachers can prescind from making dialogic moves that inadvertently close down ethical meaning-making by pushing students into particular responses. For example, Zembylas cautions teachers about letting marginalised students respond as a community representative or spokesperson, or coerce privileged students into performing their ethical transformation in front of others (cf. 2015, 171 sq.). Instead, they should retain an openness as they »empathise with students’ troubled knowledge« (ibid.) by first accepting seemingly unacceptable resistant and self-centred responses, or problematic receptive yet self-centred ones, before probing further.

However, the current theory of Dialogic Ethical Criticism has two limitations. First, its emphasis on verbal classroom discourse may elide other fine-grained paralinguistic resources of meaning-making such as intonation, rhythm, volume, etc., which are elsewhere examined in John Gordon’s (2021) model and method of ›Pedagogic Literary Narration‹, along with body language, gaze, gesture and facial expressions which inform ethical responses in subtle and significant ways. Secondly, its reliance on Anglophone contexts of empirical classroom research thus far may fail to accommodate the particularities of classrooms across different linguistic, socio-cultural, and national contexts.

By attending to the turn-by-turn realities of dialogic conversation about the referent other, Dialogic Ethical Criticism can help teachers better gauge how their ethically-oriented instructional strategies align or veer from advocating what Suzanne Choo (2024a) terms »hermeneutical justice«, where the literature classroom remains »grounded on an ethics of truth-seeking that seeks a holistic understanding of the other, premised on wisdom to navigate conflicting truth claims, and driven by responsibility for another expressed in terms of a concern for just outcomes« (3).

Acknowledgement

The author received financial support from the Nanyang Technological University Research Scholarship during the authorship of this article. The views expressed in this chapter are the author’s and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIE or NTU. The author also wishes to express his gratitude to Associate Professor Suzanne Choo for her insightful comments which have helped to develop some of the arguments presented in this paper.

References

Amiel-Houser, Tammy/Adia Mendelson-Maoz, Against Empathy. Levinas and Ethical Criticism in the 21st Century, Journal of Literary Theory 8:1 (2014), 199–218.Search in Google Scholar

Attridge, Derek, The Work of Literature, Oxford/New York, NY 2015.Search in Google Scholar

Bacalja, Alexander/Lauren Bliss, Representing Australian Indigenous Voices. Text Selection in the Senior English Curriculum, English in Australia 54:1 (2019), 43–52.Search in Google Scholar

Bakhtin, Mikhail, The Dialogic Imagination. Four Essays, transl. by Michael Holquist and Caryl Emerson, Austin, TX 1981.Search in Google Scholar

Beach, Richard, Students’ Resistance to Engagement with Multicultural Literature, in: Theresa Rogers/Anna O. Soter (eds.), Reading Across Cultures. Teaching Literature in a Diverse Society, New York, NY 1997, 69–94.Search in Google Scholar

Bender-Slack, Delane, Texts, Talk…and Fear? English Language Arts Teachers Negotiate Social Justice Teaching, English Education 42:2 (2010), 181–204.Search in Google Scholar

Blackburn, Mollie V./Caroline T. Clark/Emily A. Nemeth, Examining Queer Elements and Ideologies in LGBT-Themed Literature. What Queer Literature Can Offer Young Adult Readers, Journal of Literacy Research 47:1 (2015), 11–48.Search in Google Scholar

Blau, Sheridan, The Literature Workshop. Teaching Texts and Their Readers, Portsmouth, NH 2003.Search in Google Scholar

Boler, Megan, Feeling Power. Emotions and Education, New York, NY/London 1999.Search in Google Scholar

Booth, Wayne, »The Way I Loved George Eliot«. Friendship with Books as a Neglected Critical Metaphor, The Kenyon Review 2:2 (1980), 4–27.Search in Google Scholar

Booth, Wayne, The Company We Keep. An Ethics of Fiction, Berkeley, CA/Los Angeles, CA/London 1988.Search in Google Scholar

Borsheim-Black, Carlin, »It’s Pretty Much White«. Challenges and Opportunities of an Antiracist Approach to Literature Instruction in a Multilayered White Context, Research in the Teaching of English 49:4 (2015), 407–429.Search in Google Scholar

Borsheim-Black, Carlin/Sophia Tatiana Sarigianides, Letting Go of Literary Whiteness. Antiracist Literature Instruction for White Students, New York, NY 2019.Search in Google Scholar

Boyd, Fenice B., Conditions, Concessions, and the Many Tender Mercies of Learning through Multicultural Literature, Reading Research and Instruction 42:1 (2002), 58–92.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, Judith, Giving an Account of Oneself, New York, NY 2005.Search in Google Scholar

Choo, Suzanne S., Globalizing Literature Pedagogy. Applying Cosmopolitan Ethical Criticism to the Teaching of Literature, Harvard Educational Review 87:3 (2017), 335–356.Search in Google Scholar

Choo, Suzanne S., Teaching Ethics through Literature. The Significance of Ethical Criticism in a Global Age, Abingdon/New York, NY 2021.Search in Google Scholar

Choo, Suzanne S., The Cosmopolitan Foundations of Ethical Criticism. Perspectives from the ›East‹ and the ›West‹, Migrating Minds: Journal of Cultural Cosmopolitanism 1:1 (2023), 26–47.Search in Google Scholar

Choo, Suzanne S., Hermeneutical Justice as the Foundation of Cosmopolitan Literacy in a Post‐Truth Age, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy (2024), 1–7 (Choo 2024a).Search in Google Scholar

Choo, Suzanne S., Applying Chinese Ethical Criticism in the Teaching of Stories for Moral Education, in: John Chi-Kin Lee/Kerry J. Kennedy (eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Life and Values Education in Asia, Abingdon/New York, NY 2024, 172–181 (Choo 2024b).Search in Google Scholar

Coplan, Amy, Understanding Empathy. Its Features and Effects, in: A.C./Peter Goldie (eds.), Empathy. Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives, Abingdon 2011, 3–18.Search in Google Scholar

Critchley, Simon, The Ethics of Deconstruction. Derrida and Levinas, Edinburgh 2014.Search in Google Scholar

Davis, Danya/Melissa Steyn, Teaching Social Justice. Reframing Some Common Pedagogical Assumptions, Perspectives in Education 30:4 (2012), 29–38.Search in Google Scholar

Dixon, John, Growth through English. A Report Based on the Dartmouth Seminar, London 1969.Search in Google Scholar

Dyches, Jeanne, Critical Canon Pedagogy. Applying Disciplinary Inquiry to Cultivate Canonical Critical Consciousness, Harvard Educational Review 88:4 (2018), 538–564.Search in Google Scholar

Dyches, Jeanne/Deani Thomas, Unsettling the ›White Savior‹ Narrative. Reading Huck Finn through a Critical Race Theory/Critical Whiteness Studies Lens, English Education 53:1 (2020), 35–53.Search in Google Scholar

Eaglestone, Robert, Ethical Criticism. Reading after Levinas, Edinburgh 1997.Search in Google Scholar

Eaglestone, Robert, Ethical Criticism, in: R.E. (ed.), Literary Theory from 1966 to the Present (The Encyclopedia of Literary and Cultural Theory), Chichester et al. 2011, 581–586.Search in Google Scholar

Frimberger, Katja, ›Reading Intercultural Encounters as Art‹. The Call of the Other and the Relevance of Beauty, Pedagogy, Culture & Society 31:2 (2023), 283–304.Search in Google Scholar

Gadamer, Hans-Georg, Philosophical Hermeneutics [1976], ed. and transl. by David E. Linge, Berkeley, CA/Los Angeles, CA/London 2008.Search in Google Scholar

Gadamer, Hans-Georg, Truth and Method [1961], transl. by Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall, London/New York, NY 2013.Search in Google Scholar

Gauci, Regan/Jen Scott Curwood, Teaching Asia. English Pedagogy and Asia Literacy within the Australian Curriculum, Australian Journal of Language & Literacy 40:3 (2017), 163–173.Search in Google Scholar

Ginsberg, Ricki/Wendy J. Glenn, Moments of Pause. Understanding Students’ Shifting Perceptions during a Muslim Young Adult Literature Learning Experience, Reading Research Quarterly 55:4 (2020), 601–623.Search in Google Scholar

Goodwyn, Andy, Newbolt to Now. An Interpretation of the History of the School Subject of English in England, Changing English 28:2 (2021), 223–240.Search in Google Scholar

Gordon, John, Researching Interpretive Talk around Literary Narrative Texts. Shared Novel Reading, New York, NY/Abingdon 2021.Search in Google Scholar

Gregory, Marshall W., Redefining Ethical Criticism. The Old vs. the New, Journal of Literary Theory 4:2 (2010), 273–302.Search in Google Scholar

Gunew, Sneja, Why and How Multicultural Writing Should Be Included in the English Curriculum, English in Australia 82 (1987), 29–35.Search in Google Scholar

Haney, David, Aesthetics and Ethics in Gadamer, Levinas, and Romanticism. Problems of Phronesis and Techne, PMLA 114:1 (1999), 32–45.Search in Google Scholar

Homrich-Knieling, Matthew, Centering and Reflecting on Students’ Experiences Navigating Tough Topics in Classrooms, Voices from the Middle 27:3 (2020), 39–41.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, Lamar L., Where Do We Go from Here? Toward a Critical Race English Education, Research in the Teaching of English 53:2 (2018), 102–124.Search in Google Scholar

Johnstone, Patrick, English and the Survival of Multiculturalism. Teaching ›Writing from Different Cultures and Traditions‹, Changing English 18:2 (2011), 125–133.Search in Google Scholar

Khokan, Zakir Hossain, »First Draft«, transl. by Debabrota Basu, Southeast Asia Globe [2020], https://southeastasiaglobe.com/migrant-worker-poem-singapore/ (11.05.2020).Search in Google Scholar

Kohlberg, Lawrence, Essays on Moral Development, Vol. 1: The Philosophy of Moral Development, San Francisco, CA 1981.Search in Google Scholar

Ladson-Billings, Gloria, Three Decades of Culturally Relevant, Responsive, & Sustaining Pedagogy. What Lies Ahead?, The Educational Forum 85:4 (2021), 351–354.Search in Google Scholar

Leavis, Frank Raymond/Denys Thompson, Culture and Environment, London 1933.Search in Google Scholar

Levinas, Emmanuel, Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence [1974], transl. by Alphonso Lingis, Pittsburgh, PA 2006.Search in Google Scholar

Levinas, Emmanuel, Totality and Infinity. An Essay on Exteriority [1961], transl. by Alphonso Lingis, Pittsburgh, PA 2007.Search in Google Scholar

Lloyd, Rachel Malchow, Talking Books. Gender and the Responses of Adolescents in Literature Circles, English Teaching: Practice and Critique 5:3 (2006), 30–58.Search in Google Scholar

Loh, Chin Ee, Reading the World. Reconceptualizing Reading Multicultural Literature in the English Language Arts Classroom in a Global World, Changing English 16:3 (2009), 287–299.Search in Google Scholar

Louie, Belinda, Development of Empathetic Responses with Multicultural Literature, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 48:7 (2005), 566–578.Search in Google Scholar

Luke, Allan, Critical Literacy. Foundational Notes, Theory Into Practice 51:1 (2012), 4–11.Search in Google Scholar

Malo-Juvera, Victor, Speak. The Effect of Literary Instruction on Adolescents’ Rape Myth Acceptance, Research in the Teaching of English 48:4 (2014), 407–427.Search in Google Scholar

Marshall, James D./Peter Smagorinsky/Michael W. Smith, The Language of Interpretation. Patterns of Discourse in Discussions of Literature, Urbana, IL 1995.Search in Google Scholar

Ministry of Health, Singapore, Measures to Contain the COVID-19 Outbreak in Migrant Worker Dormitories, https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/measures-to-contain-the-covid-19-outbreak-in-migrant-worker-dormitories (14.12.2020).Search in Google Scholar

Mohamud, Libin, Talking about ›Race‹ in the English Classroom, Changing English 27:4 (2020), 383–392.Search in Google Scholar

Nah, Dominic, ›Oh No, the Poem Is in Malay‹. Examining Student Responses to Linguistic Diversity in Two Multicultural Asian Classrooms, Changing English 30:3 (2023), 249–262 (Nah 2023a).Search in Google Scholar

Nah, Dominic, Towards a Dialogic Ethical Criticism. Examining Student Responses in Classroom Debates of Poems with Ethical Invitations, L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature 23:2 (2023), 1–33 (Nah 2023b).Search in Google Scholar

Nah, Dominic, Intersubjective Interpretations from Ethical Criticism and Student Responses to Ethically Oriented Literature Pedagogies. An Integrative Literature Review, Australian Journal of English Education 58:2 (2024) [in press].Search in Google Scholar

Nie, Zhenzhao, Towards an Ethical Literary Criticism, Arcadia 50:1 (2015), 83–101.Search in Google Scholar

Nie, Zhenzhao, Ethical Literary Criticism. A Basic Theory, Forum for World Literature Studies 13:2 (2021), 189–207.Search in Google Scholar

Norton, Donna E., Teaching Multicultural Literature in the Reading Curriculum, The Reading Teacher 44:1 (1990), 28–40.Search in Google Scholar

Nussbaum, Martha C., Cultivating Humanity. A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education, Cambridge, MA/London 1997.Search in Google Scholar

Nussbaum, Martha C., Ralph Cohen and the Dialogue between Philosophy and Literature, New Literary History 40:4 (2009), 757–765.Search in Google Scholar

Poyas, Yael/Ilana Elkad-Lehman, Facing the Other. Language and Identity in Multicultural Literature Reading Groups, Journal of Language, Identity & Education 21:1 (2020), 15–29.Search in Google Scholar

Qureshi, Kira Subhani, Beyond Mirrored Worlds. Teaching World Literature to Challenge Students’ Perception of »Other«, English Journal 96:2 (2006), 34–40.Search in Google Scholar

Rabinowitz, Peter J., On Teaching The Story of O. Lateral Ethics and the Conditions of Reading, Journal of Literary Theory 4:1 (2010), 157–166.Search in Google Scholar

Rosenblatt, Louise M., Literature as Exploration [1938], New York, NY 41983.Search in Google Scholar

Spinner, Kaspar H., Literaturunterricht und Moralische Entwicklung, Praxis Deutsch 16:95 (1989), 13–19.Search in Google Scholar

Spinner, Kaspar H., Literarisches Lernen. Aufsätze, Stuttgart 2022.Search in Google Scholar

Thein, Amanda Haertling/Megan Guise/DeAnn Long Sloan, Problematizing Literature Circles as Forums for Discussion of Multicultural and Political Texts, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 55:1 (2011), 15–24.Search in Google Scholar

Thein, Amanda Haertling/DeAnn Long Sloan, Towards an Ethical Approach to Perspective-Taking and the Teaching of Multicultural Texts. Getting Beyond Persuasion, Politeness and Political Correctness, Changing English 19:3 (2012), 313–324.Search in Google Scholar

Viswanathan, Gauri, Masks of Conquest. Literary Study and British Rule in India, New York, NY/Chichester 2015.Search in Google Scholar

Warnke, Georgia, Hermeneutics, Ethics, and Politics, in: Robert J. Dostal (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Gadamer, Cambridge 2002, 79–101.Search in Google Scholar

Wiltse, Lynne/Ingrid Johnston/Kylie Yang, Pushing Comfort Zones. Promoting Social Justice through the Teaching of Aboriginal Canadian Literature, Changing English 21:3 (2014), 264–277.Search in Google Scholar

Womack, Kenneth, Ethical Criticism, in: Julian Wolfreys (ed.), Modern North American Criticism and Theory. A Critical Guide, Edinburgh 2006, 167–175.Search in Google Scholar

Xerri, Daniel/Stephanie Xerri Agius, Galvanizing Empathy through Poetry, English Journal 104:4 (2015), 71–76.Search in Google Scholar

Xu, Wenying, Making Use of European Theory in the Teaching of Multicultural Literature, Modern Language Studies 26:4 (1996), 47–58.Search in Google Scholar

Yandell, John, Exploring Multicultural Literature. The Text, the Classroom and the World Outside, Changing English 15:1 (2008), 25–40.Search in Google Scholar

Zembylas, Michalinos, »Structures of Feeling« in Curriculum and Teaching. Theorizing the Emotional Rules, Educational Theory 52:2 (2002), 187–208.Search in Google Scholar

Zembylas, Michalinos, ›Pedagogy of Discomfort‹ and its Ethical Implications. The Tensions of Ethical Violence in Social Justice Education, Ethics and Education 10:2 (2015), 163–174.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- JLT-Gespräch: Die Praxis der Literaturtheorie

- Performatives Theoretisieren: Geschriebene Vernetzungsdynamiken zwischen Theorie und Praxis in Roland Barthes’ Essay Die Lust am Text

- Articles

- Sharper Distinctions for Debates over »Realism« in German Literature and Theater

- Mapping a Theory of Dialogic Ethical Criticism

- ›Less Voice, more Viewpoint‹ – Towards a Cognitive Reconceptualization of the Centres of Orientation in Poetry

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- JLT-Gespräch: Die Praxis der Literaturtheorie

- Performatives Theoretisieren: Geschriebene Vernetzungsdynamiken zwischen Theorie und Praxis in Roland Barthes’ Essay Die Lust am Text

- Articles

- Sharper Distinctions for Debates over »Realism« in German Literature and Theater

- Mapping a Theory of Dialogic Ethical Criticism

- ›Less Voice, more Viewpoint‹ – Towards a Cognitive Reconceptualization of the Centres of Orientation in Poetry