Abstract

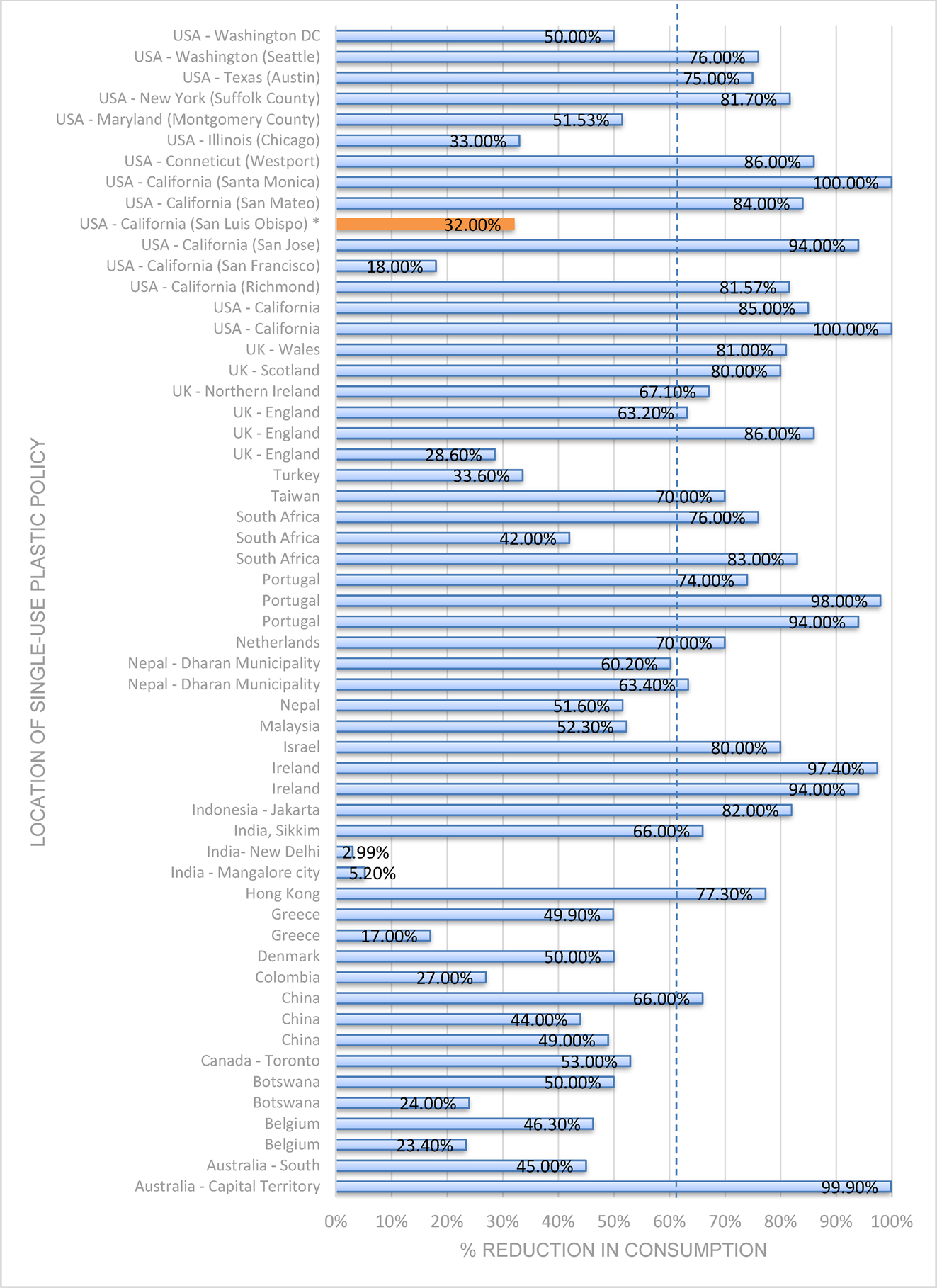

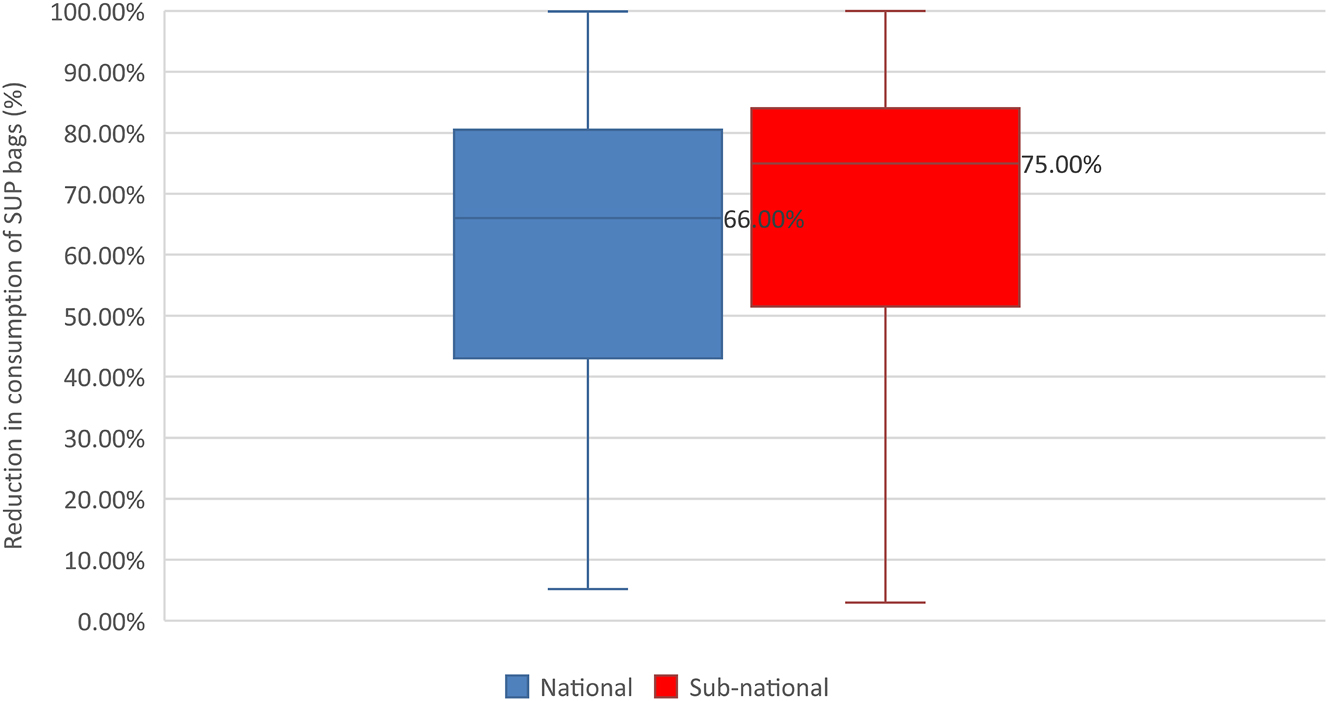

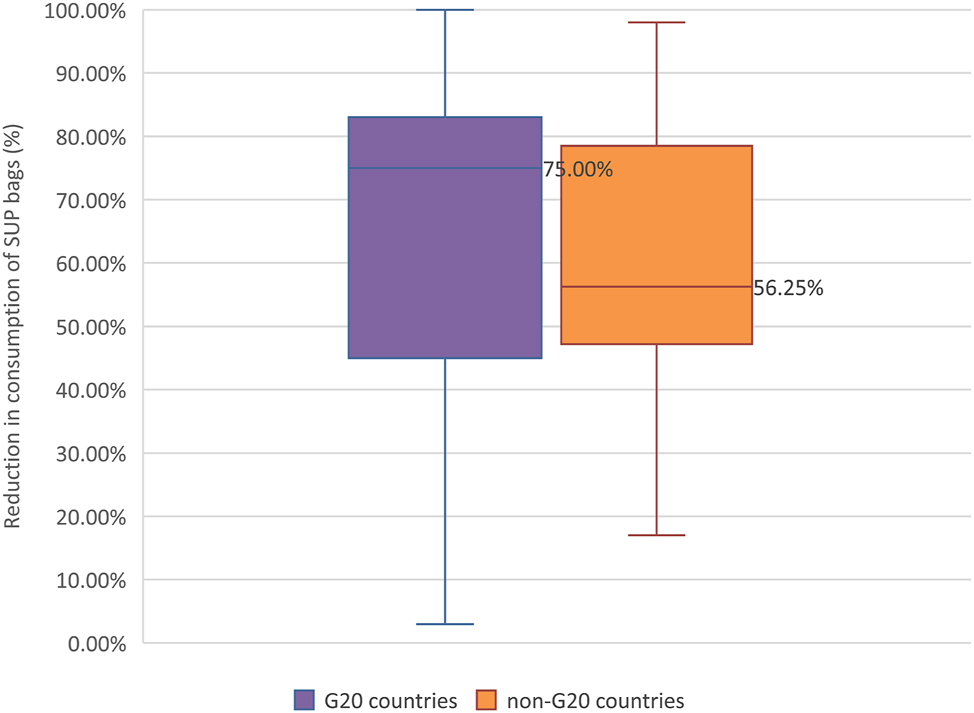

Single-use plastic (SUP) waste negatively impacts human health. While emerging jurisdictional policies target consumption of SUPs, their effects on environmental and human health remain uncertain. A systematic review of peer-reviewed and grey literature databases, using plastic and policy search terms, generated 16,684 articles. Subsequently, screening selected 51 articles, which were critically appraised. Data characterizing the types of policy and plastic, changes in consumption, and other impacts were descriptively and statistically analysed. The results span 21 countries, addressing SUP bags (49), straws (1), or mix (1). 28 papers represented national, and 23 subnational, policies that use tax-based, ban, mixed, or default-choice modification approaches. Reduction in SUP use averaged 62 %. Median reduction in bag use appeared higher for subnational (75 %) than national policies (66 %, p=0.31) and in G20 countries (75 %, vs. others, 56 %, p=0.40). Some co-benefits and unintended consequences include increased tax revenue, and increased garbage bag consumption, respectively. Considering the dataset’s limitations, policies effectively reduce SUP consumption, optimized through bottom-up policy implementation. However, G20 countries contribute most plastic pollution, which is transboundary, leaving lower-income nations astray with regulatory challenges, thereby perpetuating inequity. While co-benefits encourage policy development as a tool to reduce SUP waste, the unintended consequences must be mitigated. Additionally, knowledge gaps for certain regions, SUPs, and secondary impacts warrant further research. Ultimately, plastic pollution requires global collaboration to strive towards environmental justice.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Plastic provides a wide array of benefits to modern human life. Its lightweight, durable, and cost-effective properties bestow users with convenience, versatility, and economic attributes (Barbir et al. 2021). The world’s growing demand for plastic catalyzed its mass production, and more is made every year (Tan et al. 2021). However, plastic pollution is one of the major contributors to global environmental pollution. The World Bank estimates that 242 million tons of plastic waste are produced each year, and up to 12.7 million tons end up in the oceans (Kaza et al. 2018). Plastic can also degrade into microplastics, embed in the environment thereby polluting it, and biomagnify (Yates et al. 2021). Additionally, single-use plastic (SUP) utensils may release chemicals directly into food (Schweighuber et al. 2019). These phenomena can directly lead to negative consequences for human health, including gastrointestinal toxicity, liver toxicity, neurotoxicity, and reproductive toxicity (Chang et al. 2020).

Indirect health consequences may also arise from exposure to microplastics (Chang et al. 2020), or to pollution from other stages of the plastic’s life cycle, including greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with its production (Major 2021; Tan et al. 2021), and air pollution associated with its incineration (UNEP 2019). The burden of arthropod-borne infectious diseases associated with plastic pollution has been identified in mostly developing countries, such as Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand (Maquart et al. 2022). Notably, the extent of potential health impacts from plastic remains unclear (Yates et al. 2021). Therefore, researchers recommend the monitoring of plastic waste, reduction of plastic consumption (Palmas et al. 2022), and development of a circular economy (Agamuthu et al. 2019).

An estimated 33–50 % of plastic consumed is intended for single use (Excell et al. 2018; Tan et al. 2021). Several SUP items are termed problematic because they cannot be recycled, and are therefore more likely to exist as environmental waste (UNEP 2018a). Globally, up to five trillion SUP bags are consumed annually (UNEP n.d.). The European Union alone consumes two billion plastic takeaway containers and 36 billion straws per year (The Lancet Planetary Health 2018), while the USA consumes up to 500 million straws daily (Jonsson et al. 2021), and China about 46 billion straws per year (Qiu et al. 2021). Remarkably, G20 countries produce two-thirds of the world’s plastic waste (Fadeeva and van Berkel 2021). However, only about 9 % of all plastic waste gets recycled (Geyer et al. 2017).

Despite there not yet being a globally binding agreement on reducing plastic (Ortiz et al. 2020), governments around the world are proposing and implementing policies to mitigate the negative impacts of SUPs. Germany and Denmark were the first countries to implement a SUP reduction policy in 1991 and 1994, respectively, via a plastic bag tax (Xanthos and Walker 2017). By 2019, there were 739 national or subnational policies globally aimed to address plastic pollution, including to reduce initial plastic consumption (Karasik et al. 2020).

Despite the existance of many SUP policies, and the ongoing development of new ones, the level to which these policies are implemented, whether they achieve the desired outcome, and whether there are unintended consequences on a global level, are concepts not well outlined (Yates et al. 2021). These are important questions that researchers attempt to answer for other climate change mitigation policies as well, like the introduction of carbon taxes (Ambasta and Buonocore 2018).

A handful of reviews summarize SUP bag policies and their effectiveness in defined regions like three countries in Africa (Behuria 2021) or Europe (Kasidoni et al. 2015). However, many focus on qualitative impacts or the respondents’ perspectives on the policy, rather than environmental impact. Some also include voluntary policies, or those targeting other stages of the life cycle of plastic instead of end-user consumption. Two studies have conducted a systematic review on the effectiveness of policies limiting the use of SUP bags globally, however one focused only on bans (Muposhi et al. 2022), and the other only reviewed national-level policies (Adeyanju et al. 2021). Finally, one systematic review gathered information for several plastic items from several sources until 2018, aiming to provide an inventory of policies in all stages of the plastic’s life cycle. It did not explore global patterns of policy effectiveness specifically for policies preventing the use of SUPs, and did not discuss co-benefits (Diana et al. 2022; Karasik et al. 2020).

Many sustainable actions have the potential to provide a secondary gain, or co-benefit, to individuals or society. Some co-benefits have been identified for tax-based SUP bag policies, including revenue that is generated from sales, or an increased societal awareness of plastic pollution (Cornago et al. 2021). However, the level to which policies restricting SUP use result in co-benefits, thus potentially optimizing their uptake, needs to be better described. In contrast, there may also be trade-offs, or unintended consequences, through negative impacts on equity or consumption patterns.

This paper focuses on all preventive policies aimed at reducing consumption of SUPs, broadening the scope globally and aiming to gather evidence on co-benefits or unintended consequences associated with these policies.

2 Methods

2.1 Searching the databases

A literature search strategy was applied to four peer-reviewed literature databases and one grey literature database (Google) (Table 1).

Databases used in the literature review and their justification.

| Database | Justification |

|---|---|

| Medline (ovid) | Provides an advanced search tool and is often used for systematic level searches. It covers health and health policy. |

| Scopus | Preliminary search found papers published in this database. It includes a variety of sciences including environmental science. |

| Global health | Specializes in community and public health, and human nutrition. |

| Web of science | Contains a comprehensive selection of both science and social science articles. |

| In absence of specific search engines for impacts of plastic policies, Google is the most comprehensive and accessible grey literature resource for both publishers and authors. |

The peer-reviewed search strategy was kept broad with only two key terms, plastic and policy. This was done in an effort to capture all possible relevant papers regardless of outcome.

In Medline, the following strategy was applied:

Ovid MEDLINE(R): (8,089 articles, July 11, 2022)

ALL <1980 to 2023>

((plastic* or disposable or single-use) adj5 (single-use or straw* or bag or bags or stick* or ware)).mp.

exp Plastics/

1 or 2

(policy or policies or regulation* or guideline* or legislation* or legal* or “ban” or “bans” or banning or banned or strategy).mp.

exp Policy/

4 or 5

3 and 6

The same search strategy was applied to the three other databases by adapting the format to their own algorithm (Appendix A, Supplementary Material).

The search strategy for grey literature used three key terms, including plastic, policy, and impact, and the first 10 pages were reviewed. Subsequent searches were done using four key terms: the three above plus each of the major problematic SUPs as defined by Canada’s new policy (Appendix B, Supplementary Material). The first five pages were reviewed for each problematic SUP. Terms were chosen and refined after undergoing the peer-reviewed search, identifying the most common and correct terms used.

Finally, reference searching was applied to review papers and other articles found relevant to the topic.

2.2 Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria:

Papers presenting quantitative results from implementation of a SUP policy

Papers including at least one environmental outcome

Journal articles

Policy reports

All years of publication

Overall, a broad inclusion criterion was applied such that peer-reviewed journal articles, as well as grey literature articles and reports were included. As well, all years of publication were accepted, although a natural time limitation existed for when the first plastic policy was implemented. Finally, papers discussing an implemented SUP policy needed to include an outcome measure that demonstrates environmental impact.

Exclusion criteria:

Review papers or future modelling studies

Editorials, opinion pieces, news reports

Policy does not aim to prevent or reduce consumption of problematic SUPs

Policy described is not governmental and enforceable

Environmental impact is not measured as a change in consumption or a reasonable proxy

Non-English texts

Review papers and future modelling studies were excluded as they do not provide primary, measured data. Similarly, report styles such as editorials, opinion pieces, and news reports present uncertainty regarding bias and the source of their data, and were therefore also excluded. Further, papers were excluded if the discussed policy did not aim to reduce consumption of problematic SUPs, such as recycling policies, or if the outcome did not measure plastic reduction through a reasonable proxy. To reduce confounders and ensure comparability between policies, policies that were not governmental and enforceable were excluded. Finally, this review did not include non-English texts due to resource constraints.

The search strategy and selection criteria were cross-referenced with Adeyanju et al. 2021, but were expanded and adapted to this review’s objectives.

2.3 Screening

Peer-reviewed database results were exported to Covidence (2022) by downloading ris files from each database. Duplicates were automatically deleted on Covidence, or manually marked as duplicates. Screening was done using three stages: title, then abstract, and finally full text when applicable.

EndNote (2013) was used to acquire full texts when possible, and missing texts were searched through subscribed databases at McMaster University Health Sciences Library, University of London Online Library and LSHTM Library. A message was sent to one author through ResearchGate to access a full text, with no response.

For papers included in the review using the selection criteria, data were then extracted using Covidence and a self-created list of headings. These included the type of policy, type of plastic it targets, where and when the policy was implemented, the change in consumption of the SUP, and other impacts (Appendix C, Supplementary Material).

Grey literature searches in Google were done manually and results were cross-referenced with Covidence for duplicates. Screening was done by title, followed by full webpages. Data were then extracted into a Microsoft Excel table using the same self-created headings in Covidence. This table was also used for all reference search papers. Finally, all results were combined into one table (Appendix C, Supplementary Material). Referencing was managed using Mendeley (2022) throughout this report.

2.4 Harmonization of data

Reasonable data manipulation was done to make results more comparable. The primary outcome was a percent reduction in the consumption of SUP items at the consumer end, either by item count or by weight. When not available, reasonable proxies were deemed as follows, in order of priority: percent reduction in retailers’ acquisition of items, percent reduction in manufacturing, percent reduction in household use, and percent reduction in litter/waste collected. Lastly, percent reduction as reported by surveyed individuals was included only if the question explicitly asked if the individual reduced consumption to zero, thereby using percent reduction of individuals using SUPs as proxy. Percent reduction was calculated in relative terms by comparing the current level of use with the level of use before the policy implementation. In scenarios where several datapoints were provided for level of use over time, additional datapoints were created under the same paper for different timeframes, resulting in a larger number (56) than the total number of studies (51). Of note, one policy in Nepal, representing a partial ban on specific thin plastic bags, showed an 80 % increase in plastic use by weight because individuals used thicker, non-banned plastic bag alternatives. This value is distinctly different than all other data points and may not truly represent an increase in SUP if the thicker plastic could be re-used. Therefore, it was removed as an outlier.

2.5 Data analysis

Descriptive analysis of the entire dataset was done using Microsoft Excel and Datawrapper (Datawrapper 2025).

Statistical analysis of comparable data (aggregated SUP bag policies) was done in Stata (https://www.stata.com/). Given the data’s skewed distribution, a test for comparison of medians was done using a Mann-Whitney test.

2.6 Critical appraisal

The peer-reviewed search identified cohort, mixed methods, and cross-sectional studies. Validated tools were used to appraise the quality of each study type, including the CASP Cohort Study Checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme 2022) (Appendix D, Supplementary Material), Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Nha HONG et al. 2018) (Appendix E, Supplementary Material), and Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) (Downes et al. 2016) (Appendix F, Supplementary Material). Each question was regarded as equal in value and a point was given for each question the study scored a “yes” on (or the equivalent for low risk of bias). Questions seven and eight were omitted from the CASP Cohort Study Checklist as they were not easily applicable to the data and scoring them for risk of bias was not possible.

Grey literature was appraised using the Public Health Ontario guide to appraising grey literature (Public Health Ontario 2015) using the same scoring method (Appendix G, Supplementary Material). Data from the year 2000 or later were considered recent data for the relevant question. One peer-reviewed article was found through this search and was consequently appraised with AXIS. Reference search results were appraised accordingly, where one required a peer-reviewed appraisal tool, and the remainder qualified for the grey literature tool.

Studies that received a “yes” in more than three-quarters of the questions were identified as studies with low risk of bias. Those that received a “yes” in more than half and up to three-quarters of the questions were labelled as having a medium risk of bias. Those that only received a “yes” in half or less of the questions were labelled as having a high risk of bias. Studies of all quality were included in the review, to avoid potentially systematically excluding a certain pool of evidence.

2.7 Ethics

This project’s proposal was approved by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee.

3 Results

3.1 Overview of the available data

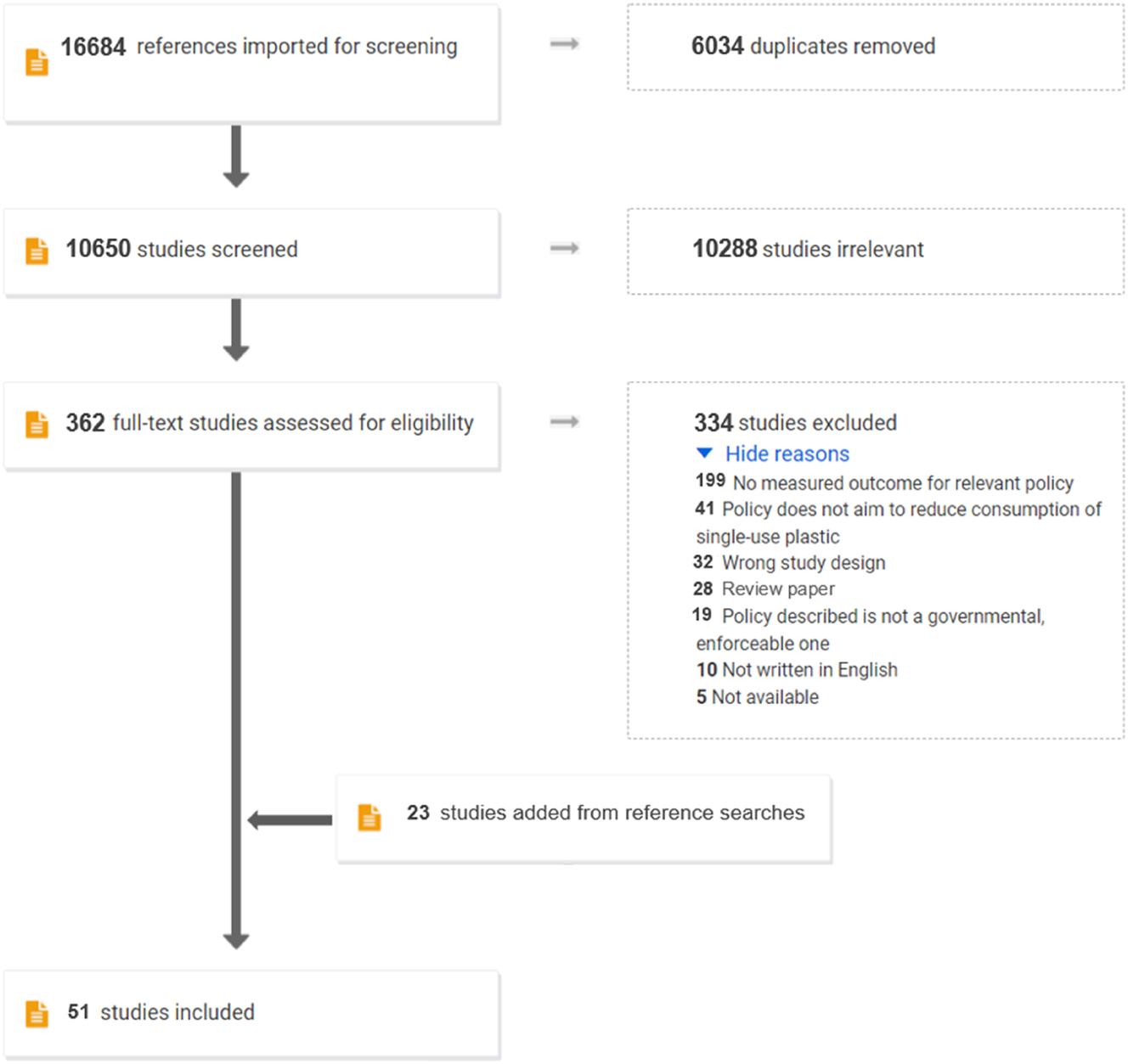

After accounting for duplicates, 10,650 titles were found through our search: 10,314 from peer-reviewed and 336 from grey literature searches. 362 articles were selected for full-text screening, 63 of which came from the grey literature. During the full-text screening, 334 papers were excluded, most commonly because the paper did not provide a measured change in SUP use or a reasonable proxy, or the policy studied was not specifically targeting the reduction in use of SUPs. Ultimately, 21 studies were selected from the peer-reviewed search, and seven from the grey literature search, in addition to 23 articles from reference searching – 22 of which were from the grey literature. Therefore, a total of 51 papers were identified for this review (Figure 1).

PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) search strategy flow diagram, combining peer-reviewed, grey literature, and reference searches. Adapted from Covidence (2022).

3.2 Descriptive analysis

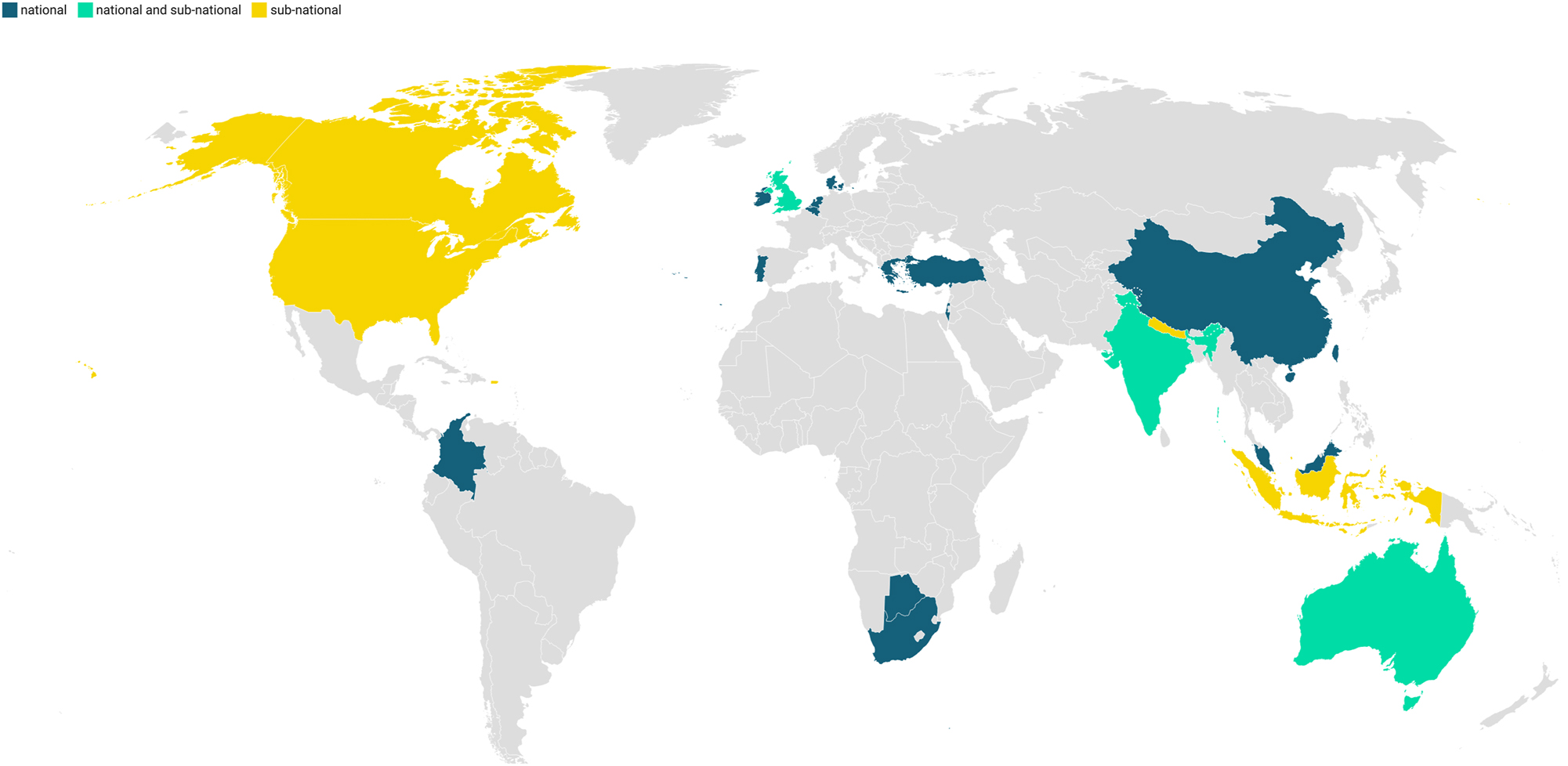

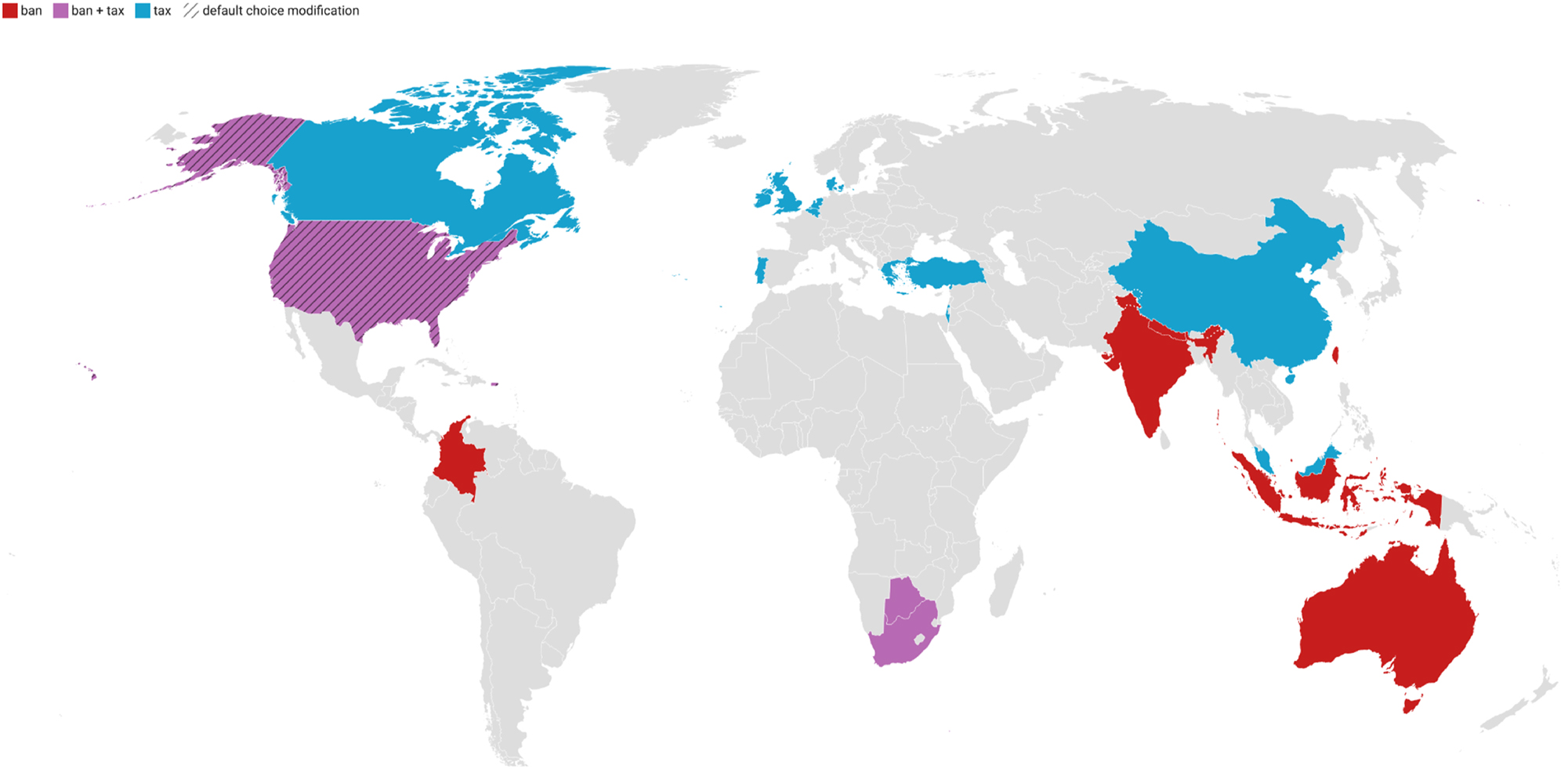

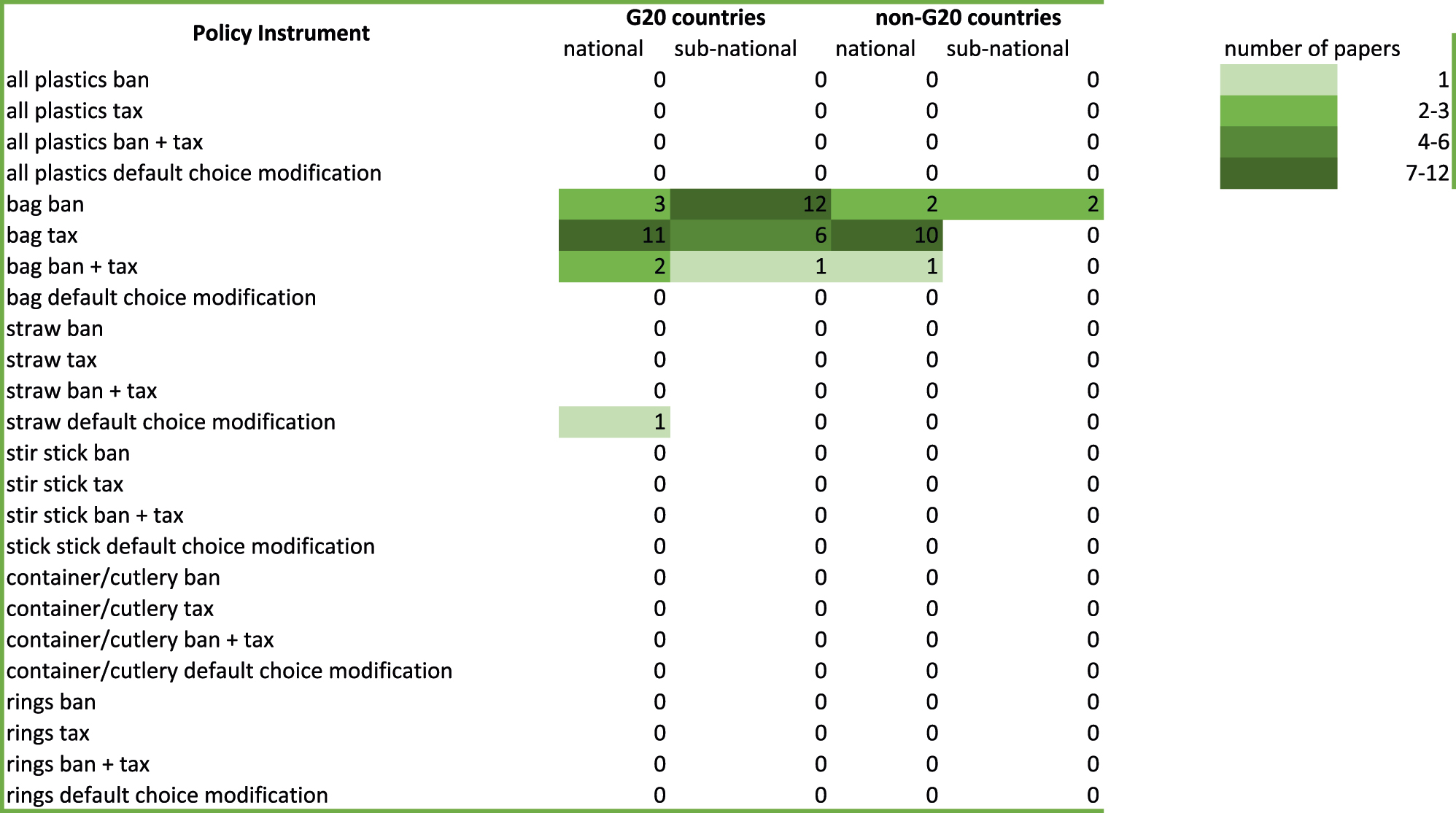

The included papers analyzed policies from 21 different countries, and these policies were implemented between the year 1994 and 2020. One paper covered a policy addressing several SUP items, another one studied single-use straws, and the remaining 49 addressed single-use bags (Table 2). Of the policies introduced, 28 were implemented nationally, and 23 were sub-national – including at the level of the city, county, region, province, or state (Figure 2). 28 of the policies taxed a SUP item, 19 policies banned the item, three presented a combination of a tax and ban, and one introduced a default-choice modification scheme (Figure 3). European countries tended to provide evidence for the effectiveness of national-level, tax-based policies, while other regions were more diverse. However, most of Africa, Asia, and South America lacked evidence on the effectiveness of any policies (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Summary of results: policies aimed at reducing SUP items and their effectiveness (see Appendix C, Supplementary Material for full details).

| Study ID | Location | Plastic type | Policy type | Level of policy | Reduction in plastic consumption | Timeframe of impact (months) | Co-benefits | Unintended consequences | Quality assessment – risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macintosh et al. (2020) | Australia – Capital Territory | Bags | Ban | National | 100 % | 8 | Increased use of bin liners | Low | |

| Aspin (2012) | Australia – South | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 45 % | 36 | Increased use of bin liners | Low | |

| EU (IBGE 2011) | Belgium | Bags + other | Tax | National | 23 % | 12 | Tax revenue | Utensils & tableware consumption did not change | Medium |

| 46 % | 24 | ||||||||

| Dikgang and Visser (2012) | Botswana | Bags | Ban + tax | National | 24 % | 1 | Larger drop in consumption in higher income retailers | Medium | |

| 50 % | 18 | ||||||||

| Solid Waste Management Services (2013) | Canada – Toronto | Bags | Tax | Subnational | 53 % | 36 | Some reduction maintained despite rescinded policy | Low | |

| He (2012) | China | Bags | Tax | National | 49 % | 6 | Reduction higher in more developed parts | Low | |

| Wang and Li (2021) | China | Bags | Ban | National | 44 % | 9 | Increased other plastic consumption | Medium | |

| O’Loughlin (2011) | China | Bags | Tax | National | 66 % | 12 | Increased use of bin liners; plastic industry affected | Low | |

| Hong Kong (Environmental Protection Department 2021) | China – Hong Kong | Bags | Tax | National | 77 % | 12 | Low | ||

| UNEP (2017) | Colombia | Bags | Ban | National | 27 % | 6 | High | ||

| (The Danish Ecological Council n.d.) | Denmark | Bags | Tax | National | 50 % | Not explicit | Tax revenue | Low | |

| Mentis et al. (2022) | Greece | Bags | Tax | National | 17 % | 12 | Reduction in use of other bags | Medium | |

| 50 % | 24 | ||||||||

| Joseph et al. (2016) | India – Mangalore city | Bags | Ban | National | 5 % | 120 | Low | ||

| Gupta (undated) | India – New Delhi | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 3 % | 24 | High | ||

| UNEP (2018c) | India – Sikkim | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 66 % | Not explicit | Medium | ||

| GIDKP (2021) | Indonesia – Jakarta | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 82 % | 12 | Decreased visible plastic waste | Medium | |

| Convery et al. (2007) | Ireland | Bags | Tax | National | 94 % | 24 | Tax revenue; reduced visible litter | Policy administration costs | Medium |

| Anastasio and Nix (2016) | Ireland | Bags | Tax | National | 97 % | 48 | Tax revenue | Plastic industry affected | Low |

| UNEP (2018b) | Israel | Bags | Tax | National | 80 % | 12 | Reduced marine litter | High | |

| Asmuni et al. (2015) | Malaysia | Bags | Tax | National | 52 % | 24 | Low | ||

| (B Bharadwaj et al. 2020) | Nepal | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 52 % | 36 | Low | ||

| Partial ban | Subnational | (+) 80 % | |||||||

| Bishal Bharadwaj et al. (2021) | Nepal – Dharan Municipality | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 63 % | 1 | Low | ||

| 60 % | 12 | ||||||||

| Government of The Netherlands, (Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment n.d.) | Netherlands | Bags | Tax | National | 70 % | Not explicit | Reduced litter | Increase in use of other bags | Medium |

| Luís et al. (2020) | Portugal | Bags | Tax | National | 94 % | 12 | Tax revenue | Medium | |

| 98 % | 24 | ||||||||

| Martinho et al. (2017) | Portugal | Bags | Tax | National | 74 % | 4 | Increased use of bin liners | Low | |

| Nhamo (2005) | South Africa | Bags | Tax | National | 83 % | 12 | Tax revenue | Medium | |

| Nhamo (2008) | South Africa | Bags | Ban + tax | National | 42 % | 3 | Plastic industry affected | Medium | |

| Johane Dikgang et al. (2012) | South Africa | Bags | Tax | National | 76 % | 60 | Plastic industry lobby reduced tax (mostly in higher-income retailers) still, increase in consumption mostly in lower-income retailers | High | |

| Tsai (2021) | Taiwan | Bags | Ban | National | 70 % | Not explicit | Medium | ||

| Senturk and Dumludag (2021) | Turkey | Bags | Tax | National | 34 % | Not explicit | Increased use of bin liners | Medium | |

| Thomas et al. (2019) | UK – England | Bags | Tax | National | 29 % | 1 | Low | ||

| UK government (Department for Environment 2022) | UK – England | Bags | Tax | National | 86 % | 48 | Tax revenue | Low | |

| Poortinga et al. (2016) | UK – England | Bags | Tax | National | 63 % | 9 | Low | ||

| UK government (Johnston 2018) | UK – Northern Ireland | Bags | Tax | National | 67 % | 60 | Tax revenue | Low | |

| Zero Waste Scotland (McElearney and Warmington 2015) | UK – Scotland | Bags | Tax | National | 80 % | 12 | Tax revenue. Saved 2,690 tonnes of CO2eq annually | Low | |

| WRAP (Quested 2013) | UK – Wales | Bags | Tax | National | 81 % | 12 | Increased use of bin liners | Low | |

| R. L. C. Taylor (2019) | USA – California | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 100 % | 12 | Increased use of bin liners | Medium | |

| CalRecycle (2019) | USA – California | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 85 % | 6 | Reduced consumption of other bags; reduced coastal litter | Low | |

| R. L. Taylor and Villas-Boas (2016) | USA – California (Richmond) | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 82 % | 3 | Increased use of paper bags | Medium | |

| Klick and Wright (2012) | USA – California (San Francisco) | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 18 % | 24 | 5.4 deaths from intestinal infection/year | Medium | |

| (City of San Jose n.d.) | USA – California (San Jose) | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 94 % | 84 | Reduced litter in river and storm drains | Low | |

| Wagner and Toews (2018) | USA – California (San Luis obispo) | Straws | Default choice modification | Subnational | 32 % | 3 | Decrease in business costs | Medium | |

| San Mateo County (2014) | USA – California (San Mateo) | Bags | Tax | Subnational | 84 % | 13 | Increased use of reusable bags or no bags | Medium | |

| Team Marine (2013) | USA – California (Santa Monica) | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 100 % | 24 | Increased use of paper bags | Medium | |

| Town of Westport, Connecticut 2010 (Brown n.d.) | USA – Connecticut (Westport) | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 86 % | 15 | Medium | ||

| Homonoff et al. (2021) | USA – Illinois (Chicago) | Bags | Tax | Subnational | 33 % | 3 | Reduction decreased after 1 year | Low | |

| Homonoff (2018) | USA – Maryland (Montgomery county) | Bags | Tax | Subnational | 52 % | 3 | Increased use of reusable bags or no bags | Low | |

| Bellone et al. (2019) | USA – New York (Suffolk county) | Bags | Tax | Subnational | 82 % | 12 | Reduced consumption of other bags; reduced shoreline litter | Low | |

| Waters (2015) | USA – Texas (Austin) | Bags | Ban | Subnational | 75 % | 6 | Increased cost to consumers and retailers | Low | |

| Howe et al. (2019) | USA – Washington (Seattle) | Bags | Ban + tax | Subnational | 76 % | Not explicit | Decrease plastic waste in landfill | Medium | |

| DC Gov, DEE (Power 2013) | USA – DC (Washington) | Bags | Tax | Subnational | 50 % | 6 | Reduced stream litter | Low |

Geographical distribution of the available evidence on the effectiveness of policies that aim to reduce the consumption of SUPs by the level of policy. Countries shaded in blue introduced a national-level policy, countries shaded in yellow introduced a sub-national-level policy, and countries shaded in green have introduced both national and sub-national level policies. Created with Datawrapper 2025 . (Map lines delineate study areas and do not necessarily depict accepted national boundaries).

Geographical distribution of the available evidence on the effectiveness of policies that aim to reduce the consumption of SUPs by the type of policy. Countries shaded in blue implemented a tax-based policy, countries shaded in red imposed a ban, and those shaded in purple have implemented various ban and tax-based policies. A striped pattern indicates a default choice modification policy, which was unique to the United States of America. Created with Datawrapper 2025 . (Map lines delineate study areas and do not necessarily depict accepted national boundaries).

Of the total papers, 23 were peer-reviewed and 28 were grey literature (Appendix C, Supplementary Material). Most papers had a low (n=26) or medium risk (n=21) of bias, with only four assessed as having high risk of bias (Table 2). When grouped by country income level, G20 countries had a higher proportion of evidence with low risk of bias when compared with non-G20 countries (65 % and 43 %, respectively). Of note, most of the evidence came from G20 countries (Figure 4). The largest amount of evidence covered SUP bag taxes, then SUP bag bans. There is a clear gap in evidence for most other SUPs, and more so in non-G20 countries (Figure 4).

Heatmap displaying the frequency of evidence for the effectiveness of SUP reduction policies, by each SUP item, each type of policy, and whether it came from a G20 country or not (n=51).

The average reduction in use of all SUPs in response to all policies was 62 %, with a median of 66 % and a very wide range encompassing a minimum of 3 % and a maximum of 100 % (Figure 5).

Percent reduction in SUP consumption due to all policies by location (n=56). * (orange) refers to straws, while the others refer to bags. Dashed line represents the overall mean reduction (62 %). One outlier removed.

3.3 Single-use plastic bags

The average reduction in consumption of SUP bags in response to a policy was 63 %. There was no apparent difference between the median effectiveness of bans (63 %) compared with taxes (64 %), nor was there a change in effectiveness with length of time passed since the policy’s implementation (Appendix H, Supplementary Material). Compared to policies implemented at a national level, those implemented sub-nationally had a 9 % higher median in reduction of use, although the difference did not reach statistical significance, and the data has a notably wide range (p=0.31, Figure 6).

Box plots showing the reduction in consumption of SUP bags by the level of the policy (p=0.31). Blue (left) represents ban and tax-based policies at a national level, while red (right) represents those at a sub-national level (n=55). The horizonal line crossing each box represents the median.

Further, the median reduction in use of SUP bags from policies in G20 countries was 19 % higher than non-G20 countries (p=0.4, Figure 7). Similarly, the difference did not reach statistical significance and the dataset has a notably wide range.

Box plots showing the reduction in consumption of SUP bags from policies implemented in G20 countries (purple, left) compared with non-G20 countries (orange, right). The horizonal line crossing each box represents the medians (p=0.4, n=55).

3.3.1 Co-benefits and unintended consequences

Of the 51 papers, 39 reported at least one co-benefit or unintended consequence. Co-benefits were reported by 22 papers, and unintended consequences were reported by 21. Compared with non-G20 countries, G20 countries reported more co-benefits and more unintended consequences.

3.3.1.1 Unintended consequences

The most prevalent unintended consequence was the increased consumption of other disposable items (n=11), including garbage bags and paper bags, followed by negative impacts surrounding the plastic industry (n=4), including factory closures, job losses, and industry lobbying against policymakers (Table 2). Three papers noted that reduction in bag use was more pronounced in wealthier parts or stores of the region where the policy was implemented. Other impacts include one report that noted an increase in intestinal infections from dirty reusable bags, two papers that noted increased costs associated with implementing new policies, and one article that noted a tax policy’s effectiveness decreased after one year of implementation.

3.3.1.2 Co-benefits

The most common co-benefits were economic (n=10) including tax revenue generated for charity, retailer profit, or governmental funding, and cost savings to retailers, followed by the reduction of visible plastic pollution (n=9) in the streets, storm drains, rivers, streams, shorelines, and the sea (Table 2). Other co-benefits included the culture shift that saw shoppers not using any disposable bags when shopping, environmentally conscious behaviour that persisted despite policies being rescinded, and estimated reductions in petroleum use and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from reduced plastic (Table 2). While tax-based policies had the unique co-benefit of revenue generation, they also led to intranational inequity in bag use reduction. Otherwise, there was no clear difference in quantity or type of co-benefits or unintended consequences between bans and taxes (Table 2). See Appendix C, Supplementary Material for more detailed descriptions of each outcome.

3.4 Other single-use plastics

It was not possible to conduct any quantitative analysis for plastics other than bags due to a lack of data. However, Belgium’s picnic tax included SUP utensils/table ware, and although not specifically quantified, consumption of utensils and table ware was reported to show no change as a result of the tax (Table 2). Tax revenue has increased since the policy’s implementation, but the items’ purchase price has increased concurrently, so consumption may have remained stable.

Additionally, San Luis Obispo, California, implemented a default-choice modification policy for SUP straws, which only provided straws to customers who requested them. Consequently, straw consumption declined by 32 % (Table 2).

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of results

Of the 51 papers identified, the overwhelming majority discussed SUP bag policies. Tax-based policies were most common, followed by ban-based policies, and most were effective in reducing consumption, with an average reduction of 62 %. There was no obvious difference in effect between bans and taxes, or with duration of time since policy implementation. Slightly more than half of the polices were implemented nationally, which appeared to be less effective than the remaining policies that were implemented sub-nationally (medians of 66 % and 75 %, respectively). Policies appeared to be more effective in G20 countries (75 %), compared with non-G20 countries (56 %). Although neither association reached statistical significance, the limitations of the available data – including small sample size and challenges with harmonization – suggest further investigations are needed to better quantify the association.

Finally, many co-benefits and unintended consequences were identified as a result of these policies. Co-benefits could indirectly improve human health; For example, reduced visible litter improves walkability of communities, while revenue collected from tax was sometimes donated to charity that supported environmental or human health causes. Other climate-friendly outcomes, like the estimated CO2 emission reductions, could help mitigate climate change. However, 11 papers noted an increase in consumption of other disposable items like garbage bags. Additional negative impacts manifested on the plastic industry, equity, and even one report of possible increased intestinal infections attributable to unsanitary reusable bag use.

4.2 Implications of this work

The review showed that both tax- and ban-based policies were effective at reducing SUP bag consumption, a default-choice modification scheme reduced SUP straw consumption somewhat, and a tax did not seem to impact SUP utensil consumption. These findings may inform future policies, although the wide range in policies’ percent reductions highlights the need to consider other factors that influence the policies’ impact.

Policy implementation can be contrasted between top-down and bottom-up approaches. Top-down implementation perceives the policy process as a linear and rational approach, where policy is developed at higher levels of a hierarchy and communicated to the frontline for implementation (Buse et al. 2012). This creates a theoretical division between formulation and implementation and fails to consider the impact those implementing the policy have on the outcome. In contrast, bottom-up implementation recognizes that those in subordinate levels have a meaningful influence on shaping policy and its outcome from what was envisaged higher up (Buse et al. 2012). Naustdalslid (2014) explains that top-down processes were used to implement policies supporting a circular economy for plastic, which are based on scientific knowledge alone, lack public support and indicators for national monitoring of impact. Additionally, Muposhi et al. (2021) conclude that critical success factors for tax-based policy effectiveness include performing a baseline assessment of the plastic problem, stakeholder involvement and acceptance of the tax, establishing proper tax governance and continuous monitoring, and enforcing the tax. Therefore, local support and consumer behaviour are key factors for effective policies that aim to reduce consumption and may be better achieved through subnational policies. A report from Germany found that sub-national authorities implement policies better than national policies due to less vertical governance logistics and administrative burdens, better engagement with stakeholders at the implementation level, and better ex ante assessment of the situation (OECD 2010). Of note, this administrative burden is consistent with the unintended consequence found by Convery et al. regarding administrative costs in Ireland’s national policy (Table 2).

4.2.1 Equity

Similarly, Mahadi et al. (2021) discovered that the success of implementing a new plastic policy, like changing petroleum-based plastic bags to biodegradable ones, depends on stakeholder responsibility, established infrastructure, supportive societal mindset, cost of alternatives and funding sources. In addition to a bottom-up approach that favours ground-level stakeholders, both Muposhi et al. (2022) and Mahadi et al. (2021) allude to the need of financial support. As higher-income countries have more resources, they may be better able to conduct the baseline assessment, establish a governance body, and monitor implementation, thereby improving the implementation of their policies. The lower risk of bias found in the quality appraisal of articles from G20 countries, compared with non-G20, may further support the notion of G20 countries’ better governance and monitoring processes. Moreover, given that policies appeared to be more effective in G20 countries, in conjunction with the identified unintended consequence that lower-income areas are less able to reduce plastic consumption, concerns surrounding equity and environmental justice arise. Climate change, and plastic pollution, are transborder issues (Ortiz et al. 2020). Globalization is defined as the processes that enhance the interconnection between humans over space and time, across economic, environmental, political, and cultural spheres (Hanefeld 2015). Consequently, it enables easier trade, including importing waste. In 2016, lower-income countries in East Asia and the Pacific imported 70 % of the plastic waste of higher-income countries (Brooks et al. 2018), increasing the burden of plastic pollution in more vulnerable countries where plastic waste is largely mismanaged (Akan et al. 2021). Additionally, as the plastic industry grows internationally, so does its financial power. Some unintended consequences highlight industry lobbying against governments, such as in South Africa (Johane Dikgang et al. 2012), which are consistent with unintended consequences found by Muposhi et al. (2022) Countries with lower income levels, and those whose economy depends on the plastic industry, may be more susceptible to this external pressure. These corporations are therefore said to hold financial power over certain governments, defined as the ability to influence agendas and control resources using money (Buse et al. 2012).

Additionally, higher education levels were associated with higher acceptance of a plastic bag ban, and consequent behaviour modification, in Pakistan (Jehangir et al. 2022). Lower literacy rates in lower-income countries (Bloom et al. 2014) may therefore contribute to the lower effectiveness of SUP bag policies in non-G20 countries, or in lower income regions within a city.

Of note, there may be other reasons for a policy to underperform, aside from poor implementation. If a ban is placed on plastic bags, one would expect a near 100 % reduction in consumption, and this was demonstrated in five articles (Figure 5). However, Kenya went as far as making plastic bags illegal, yet continues to see plastic bags in markets and as litter, which is attributable to the illicit market (Moore n.d.). Illicit markets and smaller reductions in consumption in non-G20 countries may suggest lower levels of effective regulations and regulatory bodies in lower-income countries. For these reasons, some suggest that the problem of plastic waste requires a globally binding agreement to solve (Williams and Rangel-Buitrago 2022). This demonstrates the complexity of addressing such a widespread issue that is transboundary and highlights the need for more comprehensive research in order to better protect vulnerable individuals from plastic pollution.

There are other potential impacts on inequity and human health not found in this review. Policies that aim to reduce plastic waste exclude vulnerable individuals from the decision-making table, such as those living with physical impairments or medical conditions that require a flexible plastic straw to eat, drink or take medication (Jenks and Obringer 2019). To contrast, there are other instances when medical needs have taken precedence over the environment. The SUP bag policy in Taiwan was paused during the COVID-19 pandemic (Appendix C, Supplementary Material), a global phenomenon that resulted in increased plastic waste (Tsai 2021). Rather than a blanket policy to eliminate SUPs, governments could consider targeted approaches to different settings, but they must involve key and underrepresented stakeholders in both the agenda-setting and decision-making processes.

4.2.2 Variations in consumption reduction across studies

There could be factors that influence the striking differences in percent reduction of SUP bags across studies, even when subdivided by country income or by level of policy. Illicit markets, lower regulatory capacity, and plastic industry financial power, which may not be explicitly identified in reports, can all be contributing factors. Further, there may be considerations for the policy’s local context, like if the current governing body provides a political environment that would further support or hinder such policies, or if certain industries can adapt to these policies. Ireland’s introduction of plastic policies that supported a circular economy was challenged by unique barriers faced by the healthcare manufacturing industry (Gaberščik et al. 2021). This again highlights the need for further research, specifically in local contexts, to better understand factors that impact the effectiveness of SUP policies.

4.2.3 Co-benefits and unintended consequences

The review identified a wide range of co-benefits and unintended consequences. The various unintended consequences mentioned thus far highlight the need to re-evaluate whether SUP policies are implemented carefully. Some of these consequences included increased consumption of other items, which was similarly identified by the review of Karasik et al. (2020) If garbage bag sales compensate for the reduction of SUP bags, which consumers may have repurposed for litter collection, the net plastic saved may be negligible. Additionally, organizations have been developing alternatives for SUP items. However, the preliminary scoping research found that some alternatives may introduce other environmental impacts. For example, reusable metal straws used by businesses have a worse carbon footprint when compared with SUP straws (Riofrio et al. 2022). Riofrio et al. (Riofrio et al. 2022) found that in Ecuador, sugar-cane plastic may be the best alternative given its local prevalence and existing technology. Biona et al. (2015) found that paper bags scored worse on four out of five environmental parameters compared with plastic bags, including CO2 emissions and acidification of the surroundings. New technology is developing to create biodegradable plastic, although there are still concerns with its environmental impact and degradation (Flury and Narayan 2021). This demonstrates that no single solution exists for all plastics, and we may be shifting one problem to another if policy is not implemented carefully. Governments need to ensure there are better alternatives available or being developed for the local context.

On the other hand, many co-benefits of these policies exist, including tax revenue that is sometimes donated to charitable causes, and the improvement of visible litter. This review also highlighted benefits to our planet when sustainable consumer behaviour persisted despite later rescinding a policy, and the noted CO2 emission reductions. In fact, these policies may aid in a culture shift by bringing awareness to plastic pollution and empowering individuals to take action. One report found that individuals who increased their reusable bag use also increased their purchasing of organic foods (Karmarkar and Bollinger 2015). Additionally, Foschi et al. (2020) found that ban policies motivate companies to undergo research and development to find solutions to their customers’ plastic use. Another unique co-benefit was highlighted in Kenya, where livestock ingestion of plastic bags reduced after a plastic bag ban (Lange et al. 2020). As Bachra et al. (2020) suggest, if governments become better aware of these co-benefits, which are diverse and meaningful, they would be more likely to implement policies aimed at preventing consumption of SUPs.

However, there is little evidence about the consequent impact these policies have on population health. One report from Scotland estimated 2,690 tons of CO2 emissions are saved annually from the reduction in consumption of SUP bags (McElearney and Warmington 2015). This could theoretically be extrapolated to mitigating climate change and consequently its direct health effects such as exposure to temperature extremes, pollution, and extreme weather events, as well as its indirect health effects including food insecurity, spread of vector-borne diseases, and population displacement due to sea-level rise (Hanefeld 2015). In contrast, one report from San Francisco, California identified that there are 5.4 additional deaths from intestinal infections per year that are attributed to the increased use of reusable bags (Klick and Wright 2012). Further, social determinants of health are widely recognized as key factors affecting health outcomes, one of which is employment and job security (WHO n.d.). The negative impact on the plastic industry in several countries led to job losses, and financial hardship can consequently worsen health outcomes of individuals. Ultimately, linking these policies to population health, whether from changes to consumer behaviour, plastic waste, climate change, or employment status, remains a knowledge gap and a challenge. Part of the challenge is the uncertainty associated with health impacts from plastic and climate change, as well as the difficulties in localizing and then quantifying them. To address these issues, an emerging area in research is focusing on a life cycle assessment, which is a method designed to measure impacts, including health impacts, of processes and has been applied for plastic (Deeney et al. 2022).

4.3 Strengths and limitations

This review followed a systematic approach and strategy, with multiple databases used, and produced a comprehensive output of relevant peer-reviewed articles. Although several review papers were identified for reference searching, only one new peer-reviewed paper was consequently added, and our Google search identified one additional peer-reviewed article. Further, this review employs an explicit methodology, and the search strategy is easily reproducible.

However, the grey literature search could be improved. Limited by time and resources, the search was made more specific to identify reports in the first 35 pages of Google hits. Although this search provided proportionally more articles that were ultimately included from the total hits when compared with the peer-reviewed search, the reference search identified 22 grey literature reports not otherwise found. Many of these reports would have possibly been found if the Google search was not limited to the first 35 pages. Further, in general, search engines are biased towards North America. To mitigate geographic bias, Google.com was used.

Another drawback is the language bias, as no resources were available for translation of non-English texts. The English search potentially neglected existing data in other languages, and the exclusion of non-English documents during screening removed several relevant papers, including some covering less frequently researched plastics like straws and food ware. This limitation was also noted by Diana et al. (2022).

Although a tool-based approach was used to assess the studies’ quality and risk of bias, the resulting categorization is only valid in context of the specific tool used and the cut-off scores decided.

Further, limitations in economics literacy led to the generalization of all tax policies under one category, although some taxes were applied at different points of the supply chain and may have impacted cost, price, supply, and demand differently.

Finally, the published evidence presented some strengths and limitations of our study design. First, reduction in plastic consumption is a more easily quantifiable outcome compared with other environmental policies that mitigate different outcomes, such as air pollution or GHG emissions, as it is less limited by technical knowledge or capacity. This allows a broader comparison for a better understanding of policy impacts across many countries. However, lack of data and heterogeneity of study designs, as well as the skew in literature towards plastic bag regulations, prevented further quantitative analysis, such as a meta-analysis. Additionally, it may not be a good indicator of the extent of the plastic industry’s influence on policy success. In fact, only 20 of the 56 data points in this review came from non-G20 countries despite them outnumbering G20 countries almost 10 to one.

4.4 Comparison with previous studies

Diana et al. (2022) similarly reviewed SUP policies globally. They found 40 policies, the majority of which similarly discussed SUP bags. However, their review was conducted in March 2018, and included voluntary and other policies. They graphed tax- and ban-based policies on SUP bags by percent reduction in consumption, but only for national-level policies with select subnational ones (total of 27 regions) (Diana et al. 2022). Their overall average reduction in SUP bag consumption was 66 %, which is similar to this review’s 63 % when removing the straw datapoint. They included fewer papers in their summary compared with this review, and they included three papers that did not meet inclusion criteria for this paper. They reached the same conclusion regarding the policies’ effectiveness as well as the indifference between tax- and ban-based ones (Diana et al. 2022). Additionally, they published a secondary report that mentions some of the unintended consequences identified in this review including the increased garbage bag consumption and pushback from the plastic industry (Karasik et al. 2020).

An OECD review similarly discussed SUP policies and their impacts but focused on OECD countries. It discovered more grey literature reviews by including non-English literature, and included policies targeting other stages in the plastic’s life cycle. It did not cumulatively quantify reduction of all policies, but it similarly concluded that market-based and regulatory (ban) policies, among others not relevant to enduser consumption, are effective in supporting the elimination of SUPs (Cornago et al. 2021). They discussed the need to incorporate other approaches and included qualitative context to explain policy effectiveness. For example, market-based policies’ effectiveness depended on consumers’ price elasticity of demand, while regulatory policies’ effectiveness depended on the alternatives available (Cornago et al. 2021). The report also described many co-benefits that are like the ones discovered in this review, including CO2 emission reductions and charitable donations, and unintended consequences including an increase in garbage bag consumption, impacts on the plastic industry, and administrative costs (Cornago et al. 2021).

Muposhi et al. (2022) qualitatively summarized secondary impacts of SUP bag bans. Although they discovered similar litter reductions, they also found one paper that reported no significant global marine litter reduction. There is little global evidence quantifying the impact of these policies on plastic litter and it is therefore challenging to conclude definitive impacts of these policies on a macro scale. Further research should therefore aim to assess this trend globally.

4.5 Further research recommendations

The results highlight quite well the gaps in knowledge and need for further research. As evident by the heatmap (Figure 4), data are missing on all types of policies addressing other problematic SUPs including stir sticks, carrier rings, straws, and utensils/food ware. One report from the UK noted a 46 % reduction in overall problematic plastic consumption including the above items, however, it does not specify which policies were attributed to this change and some policies, like recycling, do not aim to prevent consumption (WRAP 2021). Additionally, as previously mentioned, there was more evidence from G20 countries, suggesting more evidence, or knowledge translation, is needed from non-G20 countries, especially in Africa, South America, and Asia. Ultimately, it is difficult to make global conclusions based on evidence from 21 countries alone.

Further research is also needed to better quantify the net plastic reduction considering the possible subsequent increase in other plastic use, its impact on plastic pollution, air pollution, and climate change, and assess how those impact human health. Research is consequently needed to quantify the net impact on human health accounting for co-benefits and unintended consequences summarized here. It is important that each region produces evidence that considers its local context. One approach may include performing more informed and comprehensive life cycle assessments prior to implementing the policy in each location. Of course, timeliness is critical with climate change and there is an argument to implore the precautionary principle. The precautionary principle is the idea that policy makers should make prudent policy decisions if there is no evidence available, in order to solve a problem that is potentially more harmful than the possible consequences of their decision (Ball 2006). Collaboration with policy makers, researchers, and industry will therefore be needed.

5 Conclusions

This report presented a systematic literature review to summarize the effectiveness of policies implemented to reduce consumption of problematic SUPs globally.

Policy makers face much uncertainty when formulating these policies because many areas of knowledge gaps exist, which present opportunities for further research. Policy makers can consider that bans and taxes both appear to effectively reduce SUP bag consumption, more so in G20 countries and at a sub-national level. However, while there are co-benefits to these policies there are also unintended consequences with the potential to impact environmental and human health, which must be considered at a local context. Therefore, while policy makers may choose to proceed cautiously with this time-sensitive issue, further research is required on problematic SUPs other than bags, especially in underrepresented regions of the world, as well as to better quantify the net impact of policies on plastic and on human health while accounting for all external factors.

To enjoy the benefits of globalization, we must also take action to mitigate its negative consequences. The WHO’s SDGs communicate a vision for global collaboration in a positive direction. It is important that those responsible for the issue take greater ownership and appropriate action, and not just those who suffer the consequences, in order to reach solutions that are both timely and fair.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine’s library and research departments for support throughout the process, including from Anna Foss, Sarah Smith, Russell Burke and Kate Perris. We would also like to thank McMaster University’s library and research departments for support throughout the process, including Elizabeth Obermeyer-Kostash, Rachel Couban, and Julie Brown.

-

Research ethics: Exemption through LSHTM Board of Ethics.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Adeyanju, G.C., Augustine, T.M., Volkmann, S., Oyebamiji, U.A., Ran, S., Osobajo, O.A., and Otitoju, A. (2021). Effectiveness of intervention on behaviour change against use of non-biodegradable plastic bags: a systematic review. Discov. Sustain. 2: 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1007/S43621-021-00015-0.Search in Google Scholar

Agamuthu, P., Mehran, S.B., Norkhairah, A., and Norkhairiyah, A. (2019). Marine debris: a review of impacts and global initiatives. Waste Manag. Res. 37: 987–1002, https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X19845041/FORMAT/EPUB.Search in Google Scholar

Akan, O.D., Udofia, G.E., Okeke, E.S., Mgbechidinma, C.L., Okoye, C.O., Zoclanclounon, Y.A.B., Atakpa, E.O., and Adebanjo, O.O. (2021). Plastic waste: status, degradation and microbial management options for Africa. J. Environ. Manage. 292: 112758, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2021.112758.Search in Google Scholar

Ambasta, A. and Buonocore, J.J. (2018). Carbon pricing: a win-win environmental and public health policy. Can. J. Public Health = Rev. Can. Sante Publique 109: 779, https://doi.org/10.17269/S41997-018-0099-5.Search in Google Scholar

Anastasio, M. and Nix, J. (2016). Plastic bag Levy in Ireland, Available at: https://ieep.eu/uploads/articles/attachments/0817a609-f2ed-4db0-8ae0-05f1d75fbaa4/IE%20Plastic%20Bag%20Levy%20final.pdf?v=63680923242.Search in Google Scholar

Asmuni, S., Bashirah Hussin, N., Mhd, J., Khalili, and Zain, Z.M. (2015). Public participation and effectiveness of the No plastic bag day program in Malaysia. Proced. Soc. Behav. Sci. 168: 328–340, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2014.10.238.Search in Google Scholar

Aspin, M.M. (2012). Review of the plastic shopping bags (waste avoidance) act, Available at: https://www.greenindustries.sa.gov.au/documents/PBActReview_maspin_Nov2012_2%20-%20final.pdf?downloadable=1#:∼:text=The%20Act%20has%20been%20effective,in%20general%20has%20changed%20significantly.Search in Google Scholar

Ball, D. (2006). Environmental health policy. Open University Press, Available at: https://www.waterstones.com/book/environmental-health-policy/david-ball/9780335218431.Search in Google Scholar

Bachra, S., Lovell, A., McLachlan, C., and Minas, Angela Mae Dr. (2020). The co-benefits of climate action: accelerating city-level ambition, London, Available at: https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/reports/documents/000/005/329/original/CDP_Co-benefits_analysis.pdf?1597235231.Search in Google Scholar

Barbir, J., Leal Filho, W., Salvia, A.L., Fendt, M.T.C., Babaganov, R., Albertini, M.C., Bonoli, A., Lackner, M., and Müller de Quevedo, D.. (2021). Assessing the levels of awareness among European citizens about the direct and indirect impacts of plastics on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 18: 3116. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH18063116.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Behuria, P. (2021). Ban the (plastic) bag? Explaining variation in the implementation of plastic bag bans in Rwanda, Kenya and Uganda. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 39: 1791–1808, https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654421994836.Search in Google Scholar

Bellone, S., Tomarken, J.L., and Sortino, C. (2019). Annual recycling report, progress of single-use carryout bag reduction, Yaphank, Available at: https://www.suffolkcountyny.gov/portals/0/formsdocs/health/administration/Annual%20Report%20Final.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Bharadwaj, B., Baland, J.M., and Nepal, M. (2020). What makes a ban on plastic bags effective? The case of Nepal. Environ. Dev. Econ. 25: 95–114, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X19000329.Search in Google Scholar

Bharadwaj, B., Subedi, M.N., and Chalise, B.K.. (2021). Where is my reusable bag? retailers’ bag use before and after the plastic bag ban in Dharan municipality of Nepal. Waste Manag. (New York, N.Y.) 120: 494–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.10.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Biona, J.B.M.M., Gonzaga, J.A., Ubando, A.T., and Tan, H.C. (2015). A comparative life cycle analysis of plastic and paper packaging bags in the Philippines. In: 2015 international conference on humanoid, nanotechnology, information technology,communication and control, environment and management (HNICEM). IEEE, Available at: https://ieeexplore-ieee-org.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/document/7393237/.10.1109/HNICEM.2015.7393237Search in Google Scholar

Bloom, D.E., Goksel, A., Kothari, B., Milligan, P.A., and Chip, P. (2014). Education and Skills 2.0: new targets and innovative approaches, Geneva, Available at: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/GAC/2014/WEF_GAC_EducationSkills_TargetsInnovativeApproaches_Book_2014.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Brooks, A.L., Wang, S., and Jambeck, J.R. (2018). The Chinese import ban and its impact on global plastic waste trade. Sci. Adv. 4, https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIADV.AAT0131/SUPPL_FILE/AAT0131_SM.PDF.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, David (n.d.). Retail checkout bag surveys, Connecticut, https://www.cga.ct.gov/2015/ENVdata/Tmy/2015SB-00349-R000204-David%20Brown,%20Westport,%20CT-TMY.PDF (Accessed 28 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Buse, K., Mays, N., and Walt, G. (2012). Making health policy, Second. McGraw-Hill Education, UK.Search in Google Scholar

CalRecycle (2019). SB 270 report to the legislature: implementation update and policy considerations for management of reusable grocery bags in California, Available at: https://www2.calrecycle.ca.gov/Publications/Details/1647.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, X., Xue, Y., Li, J., Zou, L., and Tang, M. (2020). Potential health impact of environmental micro- and nanoplastics pollution. J. Appl. Toxicol. 40: 4–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.3915.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

City of San Jose (n.d.). Bring your own bag ordinance, https://www.sanjoseca.gov/your-government/environment/recycling-garbage/waste-prevention/bring-your-own-bag-ordinance (Accessed 28 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Convery, F., McDonnell, S., and Ferreira, S. (2007). The most popular tax in Europe? Lessons from the Irish plastic bags Levy. Environ. Resour. Econ. 38: 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-006-9059-2.Search in Google Scholar

Cornago, E., Börkeyi, P., and Brown, A. (2021). Preventing single-use plastic waste: implications of different policy approaches. In: OECD environment working papers, No. 182. OECD Publishing, Paris.Search in Google Scholar

“Covidence Systematic Review Software.” (2022). Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/.Search in Google Scholar

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2022). CASP-Cohort-Study-Checklist_2018. CASP UK - OAP Ltd, Available at: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Cohort-Study-Checklist_2018.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Datawrapper, Academy. (2025). Choropleth maps [Internet]. Datawrapper GmbH, Hamburg, Available at: https://academy.datawrapper.de/category/93-maps.Search in Google Scholar

Deeney, M., Green, R., Yan, X., Dooley, C., Yates, J., Rolker, H.B., and Kadiyala, S. (2022). Human health effects of recycling and reusing plastic packaging in the food system: a systematic review and meta-analysis of life cycle assessments. MedRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.22.22274074.Search in Google Scholar

Department for Environment, Food, & Rural affairs (2022). Single-use plastic carrier bags charge: Data in England for 2017 to 2018. Crown Copyright, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/carrier-bag-charge-summary-of-data-in-england/single-use-plastic-carrier-bags-charge-data-in-england-for-2017-to-2018#donations-to-good-causes (Accessed 29 July 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Diana, Z., Vegh, T., Karasik, R., Bering, J., Llano Caldas, J.D., Pickle, A., Rittschof, D., Lau, W., and Virdin, J. (2022). The evolving global plastics policy landscape: an inventory and effectiveness review. Environ. Sci. Policy 134: 34–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.03.028.Search in Google Scholar

Dikgang, J., Leiman, A., and Visser, M. (2012). Analysis of the plastic-bag levy in South Africa. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 66: 59–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2012.06.009.Search in Google Scholar

Dikgang, J. and Visser, M. (2012). Behavioural response to plastic bag legislation in Botswana. S. Afr. J. Econ. 80: 123–133, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1813-6982.2011.01289.x.Search in Google Scholar

Downes, M.J., Brennan, M.L., Williams, H.C., and Dean, R.S. (2016). Appraisal Tool for cross-sectional studies (AXIS), Nottingham, Available at: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/12/e011458/DC2/embed/inline-supplementary-material-2.pdf?download=true.10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

EndNote (2013). Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, Available at: https://endnote.com/.Search in Google Scholar

Environmental Protection Department (2021). Plastic shopping bag charging scheme. Gov. Hong Kong Special Admin. Reg., https://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/english/environmentinhk/waste/pro_responsibility/env_levy.html (16 December 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Excell, C., Salcedo-La, Viña, C., Worker, J., and Moses, E. (2018). Legal limits on single-use plastics and microplastics: a global review of national laws and regulations. In: UN environment, Available at: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/legal-limits-single-use-plastics-and-microplastics-global-review-national.Search in Google Scholar

Fadeeva, Z. and van Berkel, R. (2021). Unlocking circular economy for prevention of marine plastic pollution: an exploration of G20 policy and initiatives. J. Environ. Manage. 277: 111457.10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111457Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Flury, M. and Narayan, R. (2021). Biodegradable plastic as an integral part of the solution to plastic waste pollution of the environment. Curr. Opin. Green Sustainable Chem. 30: 100490, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COGSC.2021.100490.Search in Google Scholar

Foschi, E., Zanni, S., and Bonoli, A. (2020). Combining eco-design and LCA as decision-making process to prevent plastics in packaging application. Sustainability 12: 9738, https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12229738.Search in Google Scholar

Gaberščik, C., Mitchell, S., and Fayne, A. (2021). Saving lives and saving the planet: the readiness of Ireland’s healthcare manufacturing sector for the circular economy. Smart Innovation Syst. Technol. 200: 205–214, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8131-1_19/COVER.Search in Google Scholar

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J.R., and Law, K.L. (2017). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3, https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIADV.1700782/SUPPL_FILE/1700782_SM.PDF.Search in Google Scholar

GIDKP (2021). Jakarta announces reducing use of single-use plastic bags, Available at: https://dietkantongplastik.info/jakarta-umumkan-pengurangan-penggunaan-kantong-plastik-sekali-pakai/.Search in Google Scholar

Gupta, K. (undated). Consumer Responses to Incentives to reduce plastic bag use: evidence from a field experiment in urban India. In: Working papers 65, the south Asian network for development and environmental economics, New Delhi, 65. 11.Search in Google Scholar

Hanefeld, J. (2015). Globalization and health, Second. McGraw Hill Open University Press, Maidenhead, Available at: https://www.worldcat.org/title/globalisation-and-health/oclc/900276021.Search in Google Scholar

He, H. (2012). Effects of environmental policy on consumption: lessons from the Chinese plastic bag regulation. Environ. Dev. Econ. 17: 407–431, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X1200006X.Search in Google Scholar

Homonoff, T.A. (2018). Can small incentives have large effects? The impact of taxes versus bonuses on disposable bag use. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 10: 177–210, https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20150261.Search in Google Scholar

Homonoff, T., Taylor, R.L.C., Kao, L.S., and Palmer, D. (2021). Harnessing behavioral science to design disposable shopping bag regulations. Behav. Sci. Pol. 7: 51–61, https://doi.org/10.1353/bsp.2021.0012.Search in Google Scholar

Howe, A., Romer, J., Melliou, C., Rao, D., and Stein, J. (2019). Federal actions to address marine plastic pollution, Washington, Available at: https://law.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/PDFs/Publications/Emmett%20Institute/_CEN_EMM_PUB-Federal%20Actions%20to%20Address%20Marine%20Plastic%20Pollution.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

IBGE (2011). Eco-Taxation on disposable plastic bags, kitchen utensils, food wrap & aluminium foil (Pic-Nic Tax). European Union, Belgium, https://silo.tips/download/eco-taxation-on-disposable-plastic-bags-kitchen-utensils-food-wrap-aluminium-foi (5 May 2011).Search in Google Scholar

Jehangir, A., Imtiaz, M., and Salman, V. (2022). Pakistan’s plastic bag ban: an analysis of citizens’ support and ban effectiveness in Islamabad Capital Territory. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 24: 1612–1622, https://doi.org/10.1007/S10163-022-01429-2/TABLES/2.Search in Google Scholar

Jenks, A.B. and Obringer, K.M. (2019). The poverty of plastics bans: environmentalism’s win is a loss for disabled people. Crit. Soc. Policy 40: 151–161, https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018319868362.Search in Google Scholar

Johnston, T. (2018). Carrier bag Levy annual statistics 2017/18, Belfast, Available at: https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/publications/carrier-bag-levy-annual-statistics-201718.Search in Google Scholar

Jonsson, A., Andersson, K., Stelick, A., and Dando, R. (2021). An evaluation of alternative biodegradable and reusable drinking straws as alternatives to single-use plastic. J. Food Sci. 86: 3219–3227, https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.15783.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Joseph, N., Kumar, A., Majgi, S.M., Kumar, G.S., and Prahalad, R.B.Y. (2016). Usage of plastic bags and health hazards: a study to assess awareness level and perception about legislation among a small population of mangalore city. J. Clin. Diagn. Res.: JCDR 10: LM01–LM04, https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/16245.7529.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kasidoni, M., Moustakas, K., and Malamis, D. (2015). The existing situation and challenges regarding the use of plastic carrier bags in Europe. Waste Manag. Res. 33: 419–428, https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X15577858.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Karasik, R., Vegh, T., Diana, Z., Bering, J., Caldas, J., Pickle, A., and Rittschof, D. (2020). 20 Years of government responses to the global plastic pollution problem: the plastics policy inventory, Available at: https://nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/publications/20-years-government-responses-global-plastic-pollution-problem.Search in Google Scholar

Karmarkar, U.R. and Bollinger, B. (2015). BYOB: how bringing your own shopping bags leads to treating yourself and the environment. J. Mark. 79: 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1509/JM.13.0228.Search in Google Scholar

Kaza, S., Yao, L.C., Bhada-Tata, P., and van Woerden, F. (2018). What a waste 2.0: a global Snapshot of solid waste Management to 2050. What a waste 2.0: a global Snapshot of solid waste Management to 2050. World Bank, Washington, DC.10.1596/978-1-4648-1329-0Search in Google Scholar

Klick, J. and Wright, J.D. (2012). Grocery bag bans and foodborne illness, Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2196481Electroniccopyavailableat:http://ssrn.com/abstract=2196481.10.2139/ssrn.2196481Search in Google Scholar

Lange, C.N., Inganga, F., Busienei, W., Nguru, P., Kiema, J., and Ngeywo, S. (2020). The effect of plastic bags ban on the prevalence of plastic bags waste in the rumen of slaughtered livestock at three abattoirs in nairobi metropolis, Kenya and the implications on livestock industry. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 32, Available at: http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd32/2/nzavi32027.html.Search in Google Scholar

Luís, S., Roseta-Palma, C., Matos, M., Lima, M.L., and Sousa, C. (2020). Psychosocial and economic impacts of a charge in lightweight plastic carrier bags in Portugal: keep calm and carry on? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 161, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104962.Search in Google Scholar

Macintosh, A., Simpson, A., Neeman, T., and Dickson, K. (2020). Plastic bag bans: lessons from the Australian capital territory. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 154: 104638, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESCONREC.2019.104638.Search in Google Scholar

Mahadi, Z., Yahya, E.A., Amin, L., Yaacob, M., and Sino, H. (2021). Investigating Malaysian stakeholders’ perceptions of the government’s aim to replace conventional plastic bags with biodegradable and compostable bioplastic bags. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 23: 2133–2147, https://doi.org/10.1007/S10163-021-01278-5/FIGURES/1.Search in Google Scholar

Major, K. (2021). Plastic Waste and climate change – what’s the connection? WWF Australia, https://www.wwf.org.au/news/blogs/plastic-waste-and-climate-change-whats-the-connection (30 June 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Maquart, P.O., Froehlich, Y., and Boyer, S. (2022). Plastic pollution and infectious diseases. Lancet Planet. Health, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00198-X.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Martinho, G., Balaia, N., and Pires, A. (2017). The Portuguese plastic carrier bag tax: the effects on consumers’ behavior. Waste Manage. 61: 3–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.WASMAN.2017.01.023.Search in Google Scholar

McElearney, R. and Warmington, J. (2015). Carrier bag charge ‘one year on’ report, Available at: https://www.zerowastescotland.org.uk/content/carrier-bag-charge-%E2%80%98one-year-on%E2%80%99-report-0.Search in Google Scholar

Mendeley (2022). Elsevier, Available at: https://www.mendeley.com/search/.Search in Google Scholar

Mentis, C., George, M., Latinopoulos, D., and Bithas, K. (2022). The effects of environmental information provision on plastic bag use and marine environment status in the context of the environmental levy in Greece. Environ. Dev. Sustain.: 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02465-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment (n.d.). Ban on free plastic bags. Government of the Netherlands, https://www.government.nl/topics/environment/ban-on-free-plastic-bags (Accessed 28 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Moore, D. (n.d.). How smuggling threatens to undermine Kenya’s plastic bag ban. UN Environ., https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/how-smuggling-threatens-undermine-kenyas-plastic-bag-ban (Accessed 26 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Muposhi, A., Mpinganjira, M., and Wait, M. (2021). Efficacy of plastic shopping bag tax as a governance tool: lessons for South Africa from Irish and Danish success stories. Acta Commercii 21: 10, https://doi.org/10.4102/AC.V21I1.891.Search in Google Scholar

Muposhi, A., Mpinganjira, M., and Wait, M. (2022). Considerations, benefits and unintended consequences of banning plastic shopping bags for environmental sustainability: a systematic literature review. Waste Manag. Res. 40: 248–261, https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X211003965.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Naustdalslid, J. (2014). Circular economy in China – the environmental dimension of the harmonious society. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 21: 303–313, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2014.914599.Search in Google Scholar

Nha Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., et al.. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 user guide, Available at: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/.Search in Google Scholar

Nhamo, G. (2005). Policy instruments for eliminating plastic bags from South Africa’s environment. In: WIT transactions on ecology and the environment, Available at: https://www.witpress.com/elibrary/wit-transactions-on-ecology-and-the-environment/81/14805.Search in Google Scholar

Nhamo, G. (2008). Regulating plastics waste, stakeholder engagement and sustainability challenges in South Africa. Urban Forum 19: 83–101, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-008-9022-0.Search in Google Scholar

OECD (2010). The interface between subnational and national levels of government, Available at: https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/45049570.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

O’Loughlin, M.B. (2011). B.Y.O.B. (Bring your own bag): a comprehensive assessment of China’s plastic bag policy. Buffalo Environ. Law J. 18: 295–328, https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.1693247.Search in Google Scholar

Ortiz, A.A., Sucozhañay, D., Paul, V., and Martínez-Moscoso, A. (2020). A regional response to a global problem: single use plastics regulation in the countries of the pacific alliance. Sustainability 12: 8093. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12198093.Search in Google Scholar

Palmas, F., Cau, A., Podda, C., Musu, A., Serra, M., Pusceddu, A., and Sabatini, A. (2022). Rivers of waste: anthropogenic litter in intermittent Sardinian rivers, Italy (central mediterranean). Environ. Pollut. 302: 119073, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVPOL.2022.119073.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Poortinga, W., Sautkina, E., Thomas, G.O., and Wolstenholme, E. (2016). The English plastic bag charge: changes in attitudes and behaviour, Cardiff, Available at: https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/94652/.Search in Google Scholar

Power, L. (2013). Purpose and impact of the bag Law. Depart. Energy & Environ., Available at: https://doee.dc.gov/service/purpose-and-impact-bag-law.Search in Google Scholar

Public Health Ontario. (2015). Public health Ontario guide to appraising grey literature. Ontario Agency for Health Protect. Promot., Available at: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/A/2016/appraising-grey-lit-guide.pdf?la=en.Search in Google Scholar

Qiu, N., Sha, M., Xu, X., Zhu, J., Xiao, T., and Ge, Y. (2021). Sustainable development strategy of beverage straws for environmental load reduction. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 784: 012041, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/784/1/012041.Search in Google Scholar