Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a buzzword around the globe. For many, AI was once contained in high-tech labs and has now been released out into the world for the rest of us to use. Generative AI, which is what Microsoft, Apple, and OpenAI have recently offered, is only one version of AI – probably the one with the most ‘curb appeal’. In fact, AI dates to the 1950s and has offered much more banal – by today’s standards – innovations. This case study represents an effort to demystify popular notions of AI and take a first baby step toward developing AI literacy among international development practitioners. We offer two cases of courses that we developed to build appropriate bridges to the future, to show AI is not like the discovery of fire – a gift from the gods – but rather a technology that is a baby step forward in data analytics.

When the media talks about AI, they think of it as a single entity. It is not. What I would like to see is more nuanced reporting.

David Reid, Liverpool Hope University.

(BBC 13 March 2024)

Some AI advocates even claim that AI’s impact will be as profound as “electricity or fire” that it will revolutionize nearly every field of human activity. This enthusiasm has reached international development as well.

Amy Paul, Craig Jolley, and Aubra Anthony, USAID (2018 )

1 Introduction

ChatGPT has told us that it does not know the number of articles published in 2023 on Artificial Intelligence (AI) by Reuters, The New York Times, or The Economist. It does offer that AI content has risen significantly in the past year or two. Fortunately, Zhai et al. (2020) conducted a study, albeit before ChatGPT, and perhaps AI itself, became a household name, and found that over 11,000 articles were published between 1980 and 2019. Since then, Cools et al. (2024) identified – albeit with a different sampling strategy – a similar number of articles (10,089 from 1985 to 2020). Cools et al. (2024) went further to examine how AI (and automation) had changed in the public discourse, as represented by The Washington Post and The New York Times. Their research supported the “AI winter” thesis, which is a period where AI, automation, and computing shifted from being perceived by the public from a utopian lens to a dystopian one. Indeed, ICT had a very long run of positive public perception, since Turing’s first publication in the 1950s until the 1990s (Fast and Horvitz 2016).

Post ‘Y2K’, ICT in general, and AI and automation, in particular have shifted back and been understood in more positive terms by the public. Cools et al. (2024) also found that news outlet coverage changed during the first two decades of the 21st century beginning with a jumble of 10 topical areas, down to just four capturing the most media attention: work, health, education, and art.

More recently, we would argue, anecdotally, that the media has portrayed AI with increasing skepticism. Privacy issues (who can sell and use your data), social justice infractions (training sets for ML, LLMs, and Pattern Recognition), and deep fakes (the ability of AI to produce ‘reality’ for nefarious purposes) sit alongside production efficiencies, speedy data collection and analysis, self-driving cars, and plain old convenience. Despite this, many remain mystified about AI and its capacity to impact their lives. Certainly, the reach of AI is global, no matter whether you are a programmer in Brooklyn, an autoworker in Japan, or a subsistence farmer in Ethiopia. Companies investing in AI are coming for you. This paper seeks to make three points: 1) AI is not magic; 2) AI has developed unevenly across the globe; and 3) these claims provide an opportunity to connect the notion of AI in the public interest, as a public interest technology, in the global space. Rather than sit back and complain, however, we seek to offer some solutions to the frenzy around AI, what it is and what it isn’t in the domain of international development.

Our paper unfolds through the following sections. First, we examine the myths of AI through a media analysis of people’s perceptions of AI and a brief overview of the main AI regulatory regimes – laissez-faire, which we call “The Windows 95 Approach,” and, lastly, the all-bluster approach. Next, we examine AI in the context of international development and seek to link it with a “Global Public Interest Technology” perspective. Finally, we offer two options training global development partners, policy and program monitoring and evaluation of practitioners, and those who simply want to develop their AI literacy. A closing section discusses the implications of the approach and how it could be rolled out.

2 Debunking the magic of AI?

In 2018, Brennen et al. reported on how the UK media covered AI. In their study, Brennen et al. (2018) examined all mainstream media sources in the UK over an eight-month period that included a review of around 760 articles. The study found that nearly 60 % of the articles published were shaped by industry – products, initiatives, and special announcements. Academia was covered around 30 % of the time, and around 5 % were developed from government sources. Nearly 12 % of the articles directly reference Elon Musk.

Given this range of sources, it should be surprising that AI was portrayed as a relevant and competent commercial solution to a range of public problems, with little acknowledgement of AI’s potential impacts. It is also not surprising that AI was politicized by the political right and left. For the right, automation and the future of work and geopolitical threats to national security were of the greatest concern. For the left, issues of ethics, including discrimination, algorithmic bias, and privacy were among the most reported stories. Finally, the report notes – what for many today is obvious – that media attention needs to move beyond one-sided “AI industry” foci to a broader public dialogue that engages scientists, activists, and others who can provide a range of views beyond its current binary: a world-ending disruption of life as we know it, to a powerful set of tools that support human productivity, creativity, and aspirations.

It would be easy to say that all this has changed since November 30th, 2022, when ChatGPT was launched, and the public received an immersive and involuntary exposure to a powerful technology that could magically answer your questions, write your college essay, design (or replicate) images in a certain artistic style. Like COVID-19, ChatGPT spread rapidly and was the topic (and in the case of AI, the source) of misinformation. In contrast to COVID-19, no one, as far as we know, has died from this exposure, but millions of people have been affected by its availability without being inoculated with basic knowledge about what AI actually is and how it works. To paraphrase Meredith Broussard et al. (2019), you do not need to know linear algebra to understand the basics of creating artificial intelligence (Broussard et al. 2019).

Fast forward to this year, another study published by Fletcher and Nielsen (2024), found that while 60 % of their respondents had heard of ChatGPT, only 1 % had actually used it. Many people are reading about it, but precious few have actual experience with it. As Fletcher and Nielsen (2024, p. 6) point out, “There are many powerful interests at play around AI, and much hype – often salesmanship but sometimes wildly pessimistic warnings about the possible future risks that might even distract the public from already present issues.”

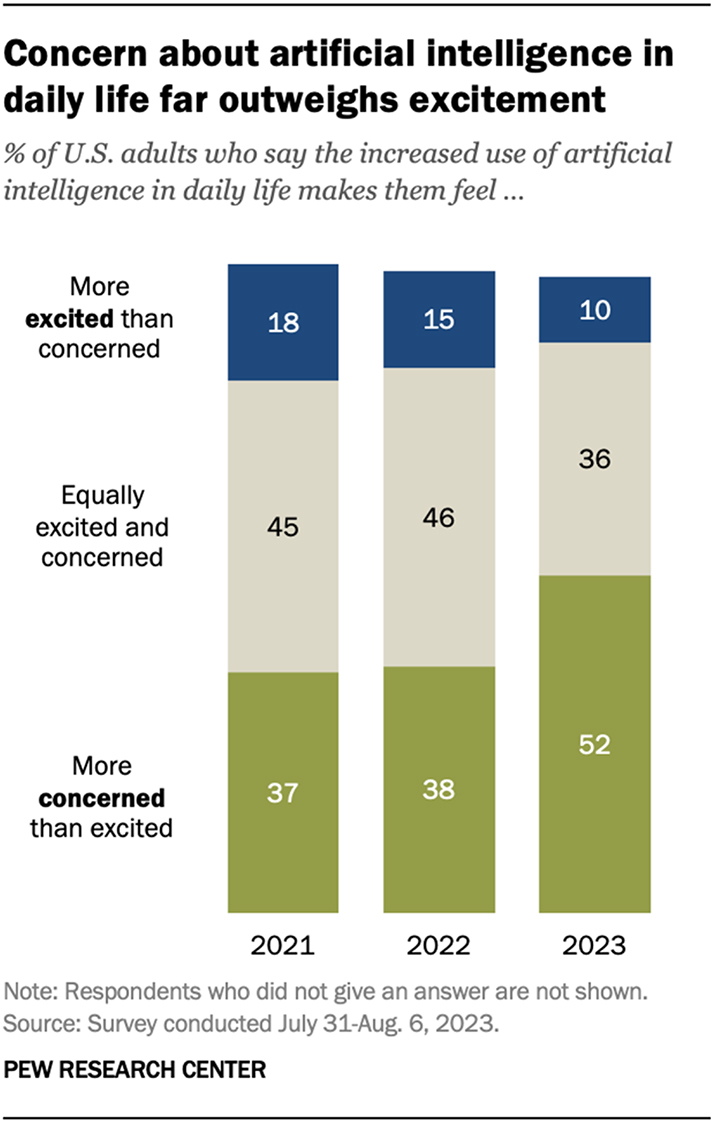

The Pew Research Center, in a study conducted in 2023 in the US, found that the trends identified by (Brennen et al. 2018) in the UK were starkly different in the post-ChatGPT internet (Nielsen 2024) (see Figure 1). These data suggest that the public remains unsure about the implications of AI, generative or otherwise, will make their own lives, or society, better or worse. This is not surprising since so many are aware of these products, and few have ever knowingly used them. As we type this essay, AI is making recommendations for completing our sentences and altering our grammar, our web searches are recorded and used to predict future web-search topics. Indeed, as we type this on the enterprise version of Word, which is saved on Microsoft’s ‘one-drive’ AI is, indeed, having its way with us.

Concerns about AI.

Even the most banally sensible of media outlets The Economist reported in the run up to the British government’s AI Safety Summit was full of hyperbole. In reference to the Betchley Park Safety Summit, an editor wrote, “And the question they will strive to answer is epochal: how to ensure that artificial intelligence neither becomes a tool of unchecked malfeasance nor turns against humanity”.

As western governments go, the traditional route of regulating new technology ranges from silence to chaotic. The Brits have stuck their heads in the sand. The EU has constructed an entire new regime, that looks somewhat like what the upgrade from Windows 95 to 97 would have looked like, to the US where we hear strong words from Biden through executive orders that have no teeth nor mechanism for enforcement. Until then, it will be the technology that regulates us as ‘thought leading’ wonks such as Elon Musk, Sam Altman, or Mark Zuckerburg, established firms and start-ups alike will create the rules and the frames for AI.

The current technology-policy-society ecosystem that supports AI is dysfunctional. For those of us who seek to shift the framing of AI to the public interest the times are both trying, at times maddening, but always full of opportunity. We have an obligation to extend current laws and precedents to meet the new requirements AI brings to the all-persons social contract. There are ethical, economic, colonial, racist, and sexist imprints on how the AI ecosystem currently functions.

In this case study, we offer our own small contribution to improving this through training and education. We focus on the international development community because it is here that we see a fresh round of extractive colonialism making its way through the Global South. Indeed, raw materials, food, energy, and water, are extracted from the Global South at record levels. We are not talking about this kind of extraction. Rather, we are concerned with contributing to the use of responsible AI by the international development community that one helps them to co-create, co-design, and develop implementing partnerships with communities they collaborate with.

3 Demystifying AI for global development

AI is everywhere. Many drones fly by AI, such as Zipline drones that deliver blood, anti-venom, and other medical supplies to villages far away from hospitals. Farmers in Africa use drones and AI to test crop health, water needs, and for diseases. So called MHealth is another way physicians and nurses use AI in places without expensive facilities. Technicians have used AI-powered apps on tablets and cell phones to check for dysplasia, other treatable precancerous conditions, and for cancer. But AI is no panacea for the rest of the world, and policy makers in Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and other regions recognize this. Fayaz King, Deputy Executive Director, Field Results and Innovation for the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), said necessary strategies were important to ensure that all approaches to AI from development to deployment to use are in the public interest. “In the effervescent realm of AI, the known, the unknown and the unknowable is best addressed through governance with humanity at its centre, for what AI giveth, AI also taketh” (United Nations 2024).

In rural India, the concept of a ‘smart village’ is one with excellent connectivity and reasonable bandwidth for communicating to the outside world, whether Bangalore or Silicone Valley. Why is this important? India has one of the most highly educated populations in ICT. Connectivity enables them to do work in their rural villages, living in proximity to their family or their partner’s family, and work in the IT industry. Here is an example of where AI giveth and taketh away. While jobs are accessible to these rural workers, they are paid pennies on the dollar in comparison to their urban, North American, or European counterparts. This represents an extractive economy in much the same way tea once was to the British Empire (Krueger et al. 2023).

Some scholars have tried to reappropriate the concept of ‘smart villages’ and transform it from its colonial roots to something generative (Krueger et al. 2023). Here we follow Eglash et al.’s (2021) concept of generative economies that enable communities to have agency in the production of their local economies. Toward this end, some multilateral donors have adopted a public interest technology perspective to ensure fair and equitable economies, privacy, and human rights and governance to name a few.

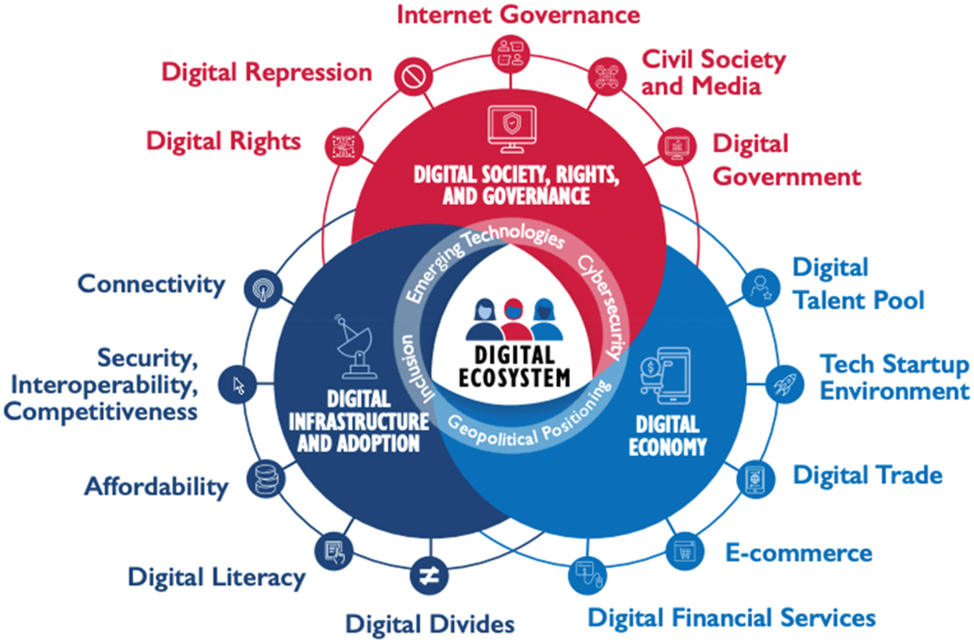

In 2019, USAID established its digital development strategy for the agency and its partners, including the U.S. Department of State and USAID contractors and implementing partners. In July 2024, after years’ research, beta testing, and assessment the agency elevated the plan to a policy (USAID 2022). The Digitial Development Policy is far reaching and takes on themes such as digital society, rights and governance, the digital economy, and digital infrastructure and adoption (see Figure 2).

Digital development policy (USAID 2022).

In parallel, countries like Kenya and Rwanda have developed complex AI policies designed to enable stable economic growth locally rather than exporting surplus value abroad. Rwanda’s policy, for example, privileges AI literacy for young professionals and apprenticeship programs. Indeed, Rwanda not only has national aspirations for how to use AI in its health, commercial, and educational ecosystems, but also how to be competitive on the global stage by creating opportunities for practitioners and scholars trained in Rwanda to interact in peer-to-peer relationships with those from places known for ICT and AI.

USAID recognizes that the digital ecosystem is only part of the story. This is why, in 2022, the agency developed an Artificial Intelligence Action plan to complement the larger digital strategy. This plan is critically important because it calls for encouraging inclusive equitable development in AI, a sector that has become increasingly centralized in Europe, North America, and Asia.

This has been a selective review of policies, plans, and strategies for integrating AI with international development, both in terms of providers and beneficiaries. What they all have in common is they represent examples of global public interest technology initiatives. With distinct histories from the US public interest technology movement, the commitment is the same.

As with any technology or policy, the proponent needs to offer training. Implementing good ideas is hard enough. There is bureaucratic inertia, human inertia, administrative changes and priority reshuffling. Given the hype around AI, many feel that it is too much of a leap to catch up with this new technology. This is not the case. Like any new technology, there are bits that are new and those that are familiar. Often, people conflate ChatGPT and generative AI technologies to AI. However, AI takes on many different forms, and these forms often rely on easy pivots in database development and statistics. Toward this end, we discuss two educational modules created at Worcester Polytechnic Institute’s Development Design Lab meant to demystify AI, with a particular focus on its applications to the international development context.

4 AI in the global public interest

Today, AI is a versatile tool that can be applied across a wide array of tasks, making it accessible and valuable to nearly every profession. From using its machine learning models to a very fundamental physics concept (Friedman et al. 2024; Khanmohammadi et al. 2024) to use neural network for image classification (Ganj et al. 2023, 2024) or large language models for clinical trials protocols (Maleki 2024) and clustering for analyzing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (Maleki and Ghahari 2024). Its ability to generate text, images, and videos through generative AI, as well as its predictive capabilities in supervised learning models, has transformed it into a tool that can be integrated with virtually any job. Much is said about the jobs of tomorrow being replaced by AI. While this may be true it is also overstated. AI cannot work without humans to direct it. Those who have developed a literacy in AI will enjoy the fruits brought by the future of work. Despite its potential for positive (or negative) change the fact remains that people outside the computer science field do not truly understand what AI is in order to 1) understand or demystify it or 2) use it in simple ways to support their needs.

5 Our approach and educational pedagogy

This paper is about taking a first step toward demystifying AI so that people can better understand it, what its current capabilities are, and what the future might bring. To do this, we present a case study of our own efforts to develop practical ways to demystify AI. We created a short, Open Educational Resource (OER), and a semester-equivalent course called AI and Society.

5.1 Open Educational Resource

This Open Educational Resource (or OER) was titled “An Introduction to Data Science for Development Policy and Practice”. The target audience for this course was those working in international development or policy with little technical background in data science concepts. Our ultimate goal was to help professionals in policy making and international development build a deeper, more interdisciplinary view of the changing landscape in which future development policy will be created and implemented.

The main objective of this course was to demystify the tools and concepts of data science for those who worked in traditional social science fields, specifically development policy. As we planned the course, we felt that there was a gap between social scientists and data scientists. Tools such as machine learning and artificial learning carry great potential for advancing development policy, but we recognized there was little dialogue between experts in these respective fields. This course was developed by an undergraduate student with an academic background in both. Built by someone with experience in both these fields, she was able to shape the course as someone who hopes to pursue a career where she can utilize her technical data science skills within a broader social science context. Throughout the course, various case studies of current data science and AI implementations in development are offered. Such examples are a testament to her own desire to apply these technologies in a human-centered way that can create sustainable change and build more equitable communities. We hoped that through this OER, we could help social scientists develop a similar understanding of AI and data science technologies and their potential to redefine policy making in international development.

Our OER was split into three modules. The first module tried to answer the question: what is data? Our second module sought to offer a glance into the data science process by discussing the data science lifecycle both in theory and in action. Our final module was more open-ended, leaving students to explore for themselves what data science looked like beyond the lifecycle, specifically different elements of artificial intelligence.

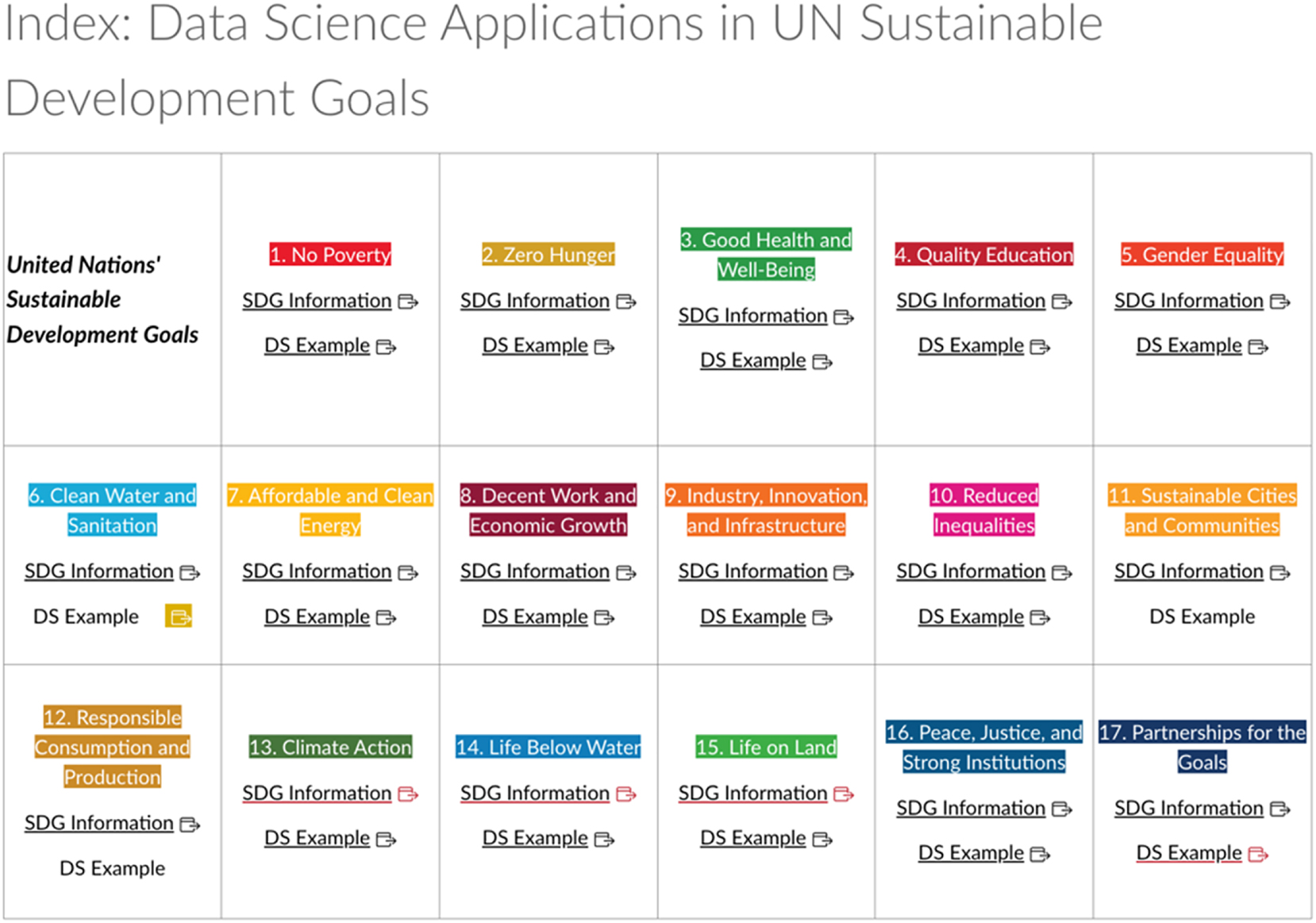

The first module asked a simple question: what is data? First the course established basic definitions of common statistical and data science concepts. The module also distinguished the differences between traditional and big data, explored different examples of different types of data in a real-world context, and examined what specific data used in development may look like. The module also provided examples of data science principles and methods, culminating in an index that examines the UN’s various sustainable development goals and data science-oriented solutions (see Figure 3).

Data science application in UN sustainable development goal.

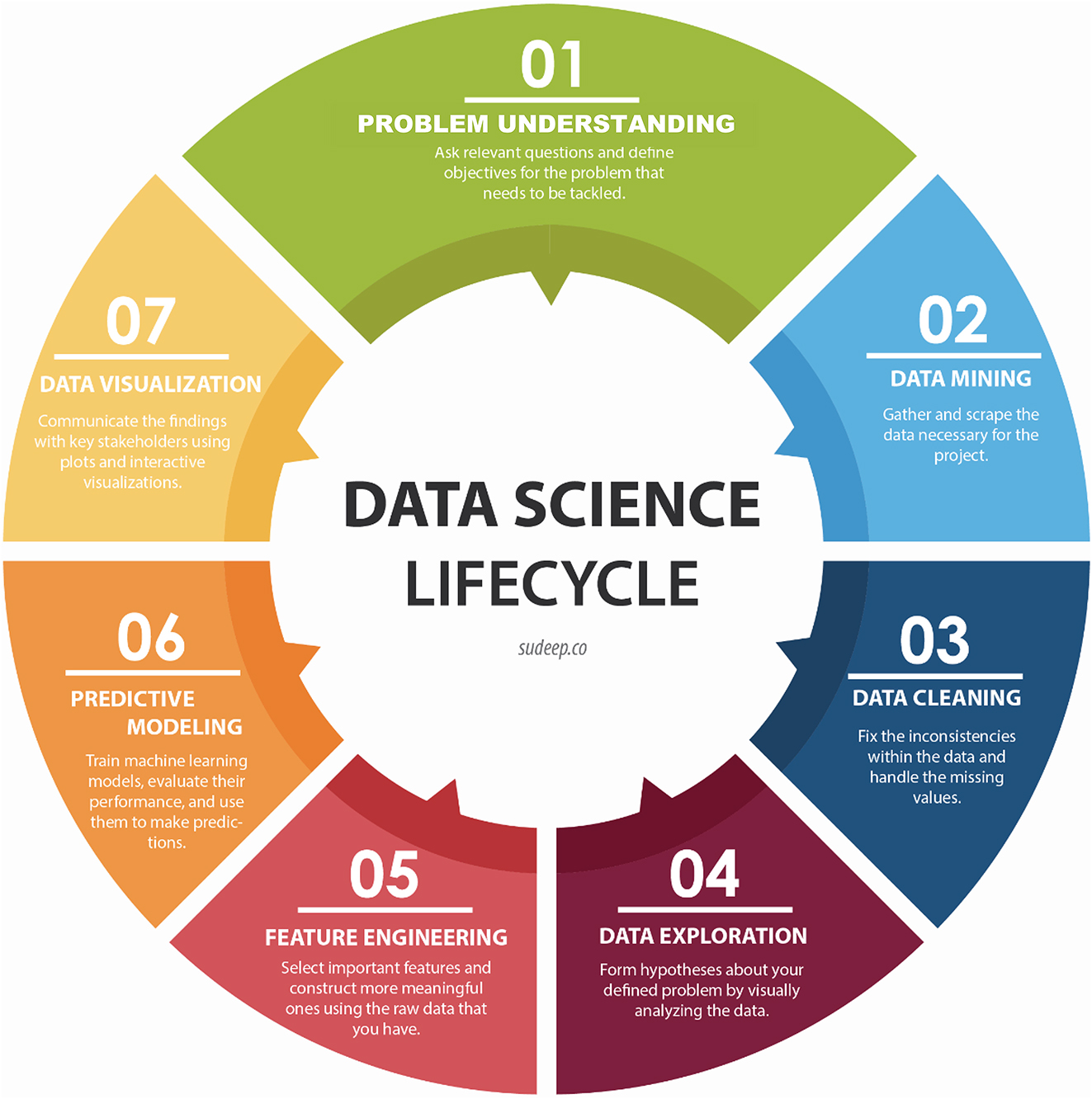

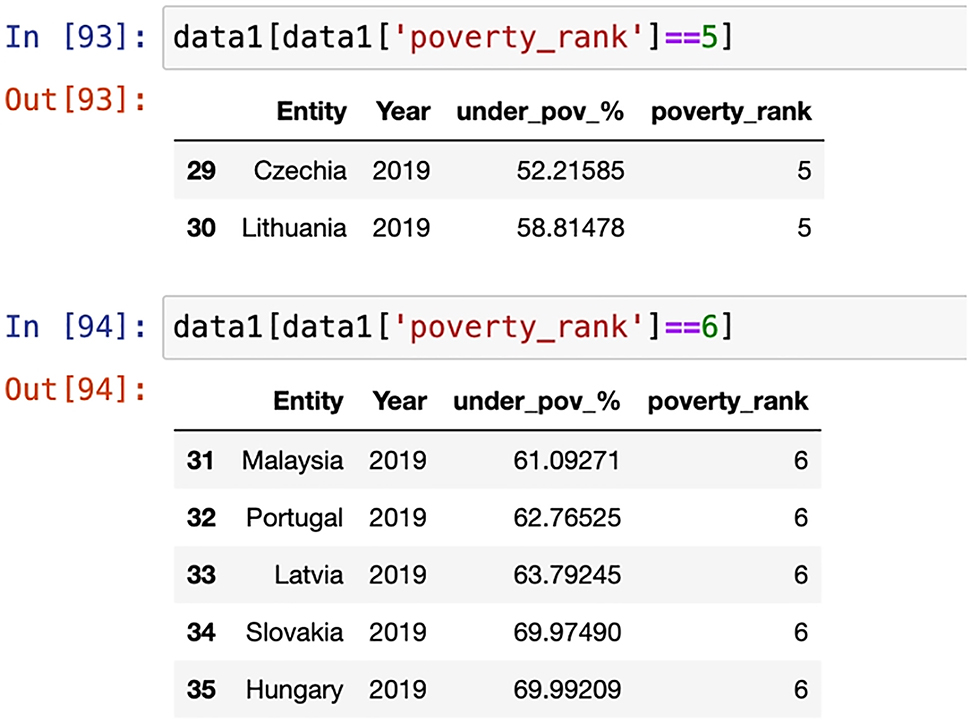

The second module walked through the data science lifecycle (see Figure 4) and how it can be applied to a real-life dataset. We worked with a dataset that tracked poverty rates in different countries from 1980 to 2020. The module first presented the theoretical steps behind the data science lifecycle, then showed example python code for each step of the cycle. The objective of the course was less about teaching its participants how to code, but rather how to understand basic elements of code and their applications: we offered the python code we used during the data science lifecycle as a course resource (see Figure 5). The second part of the module focused on machine learning, specifically decision trees. It introduced machine learning conceptually and then included an interactive activity that walked through each step of applying a decision tree to a dataset. While the activity did not involve any code, it helped break down a foreign, technical concept into easily understandable steps. Once again, the objective was not for participants to understand how to design a machine learning model from scratch, but rather how a machine learning model could be used to shape policy solutions.

Data science lifecycle.

Python code sample.

The third module was the most open-ended. It starts with a video discussing the basic tenets of AI, then offers various resources on more specific AI categories. The module directs participants to explore these resources to develop a better understanding of different AI categories, which included generative AI, machine learning, and deep learning (see Table 1).

Different AI categories.

| Type of AI | Definition | Example of use |

|---|---|---|

| Generative AI | Generative AI is defined as AI models that can create new content based on preexisting input data. Content produced includes text, images, audio, videos, or even code, depending on the scope of the model. A common example is chatbots | Generative AI could be used to simulate potential outcomes of different development policy solutions by generating predictive data results based on preexisting input data |

| Machine learning | Machine learning is defined as a subset of AI that involves training algorithms to find patterns and make predictions within data | Machine learning could be used to predict annual crop yields for farmers by analyzing sources of data such as weather patterns, satellite imagery, and historical agricultural data, in order to help farmers and other stakeholders allocate their resources effectively |

| Deep learning | Deep learning is defined as a subset of machine learning based on multiple layers of neural networks that enable the system to extract progressively higher-level features from the data, allowing computers to recognize patterns and manage more complex tasks | Deep learning can aid in healthcare diagnostics, especially in areas with weak healthcare infrastructure: deep learning models can analyze medical images such as X-rays or MRIs to detect common diseases, which can enable faster diagnoses and broaden healthcare access |

The module and course are concluded with an evaluative activity, where participants are asked to reflect on the various data science concepts they’ve reviewed and whether they can envision themselves implementing the various tools they’ve learned into their own respective fields. AI is demystified.

5.2 AI for society: semester-long asynchronous course

AI for Society is a course designed specifically for students without a computer science or data science background. Our motivation for the course stemmed from AI impact that extends far beyond the realm of technical expertise. We seek to develop AI literacy among those who, when they think of a ‘python’ think of a snake, not a programming language. Literacy among those who, in the human services, when they see the outputs of a machine learning model can critically evaluate the findings and assumptions behind the model that produced them. The course is an effort to bring those individuals into the fold who may lack the technical expertise. The truth is AI is only as good as the people who create it and deploy it. Given this, the more AI literate professionals we have the better AI will fulfill its promise as being a tool to serve many needs. The primary goal of this course is to empower those who complete it to navigate the emerging AI-driven landscape.

The course is uniquely shaped by the perspective of its designer, a PhD student in an interdisciplinary field that combines data science and social science. The instructor’s academic journey began in physics and evolved into research in AI. Her experience of transitioning from a field outside computer science to becoming an AI researcher inspired her to create this course. This personal narrative of exploring AI as an outsider makes the course particularly suited for participants from diverse backgrounds, offering them a clear path to understanding and utilizing AI in their respective disciplines.

Throughout the course, we guide participants through the fundamental concepts of AI, explore and examine its current capabilities, and unlock its vast potential for the future. By the end, students have developed a basic understanding of AI’s core principles and the critical thinking skills needed to approach it responsibly. This course is designed asynchronously to overcome geographical barriers for participants. To foster a dynamic and engaging learning experience we applied different methods of learning. Table 2 shows the steps to solidify the learning process for students.

Steps of learning.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Spark curiosity (interactive discussion) | Interactive discussions at the start of each week encourage brainstorming and exploration of real-world applications, creating active engagement before diving into material |

| 2. Weekly roadmap (concise summary) | Participants receive a concise overview of key topics for the week, helping them stay focused and prepared for the learning journey ahead |

| 3. Dive deeper (multimedia resources) | A diverse set of learning resources, including engaging text and video lectures, caters to different learning styles and ensures comprehensive understanding |

| 4. Solidify knowledge (practical assignment) | Practical assignments challenge participants to apply the week’s concepts to real-world scenarios, testing knowledge and building valuable skills |

| 5. Go beyond the syllabus (optional readings) | Additional resources are available for participants who wish to explore topics further, offering deeper insights beyond the core syllabus |

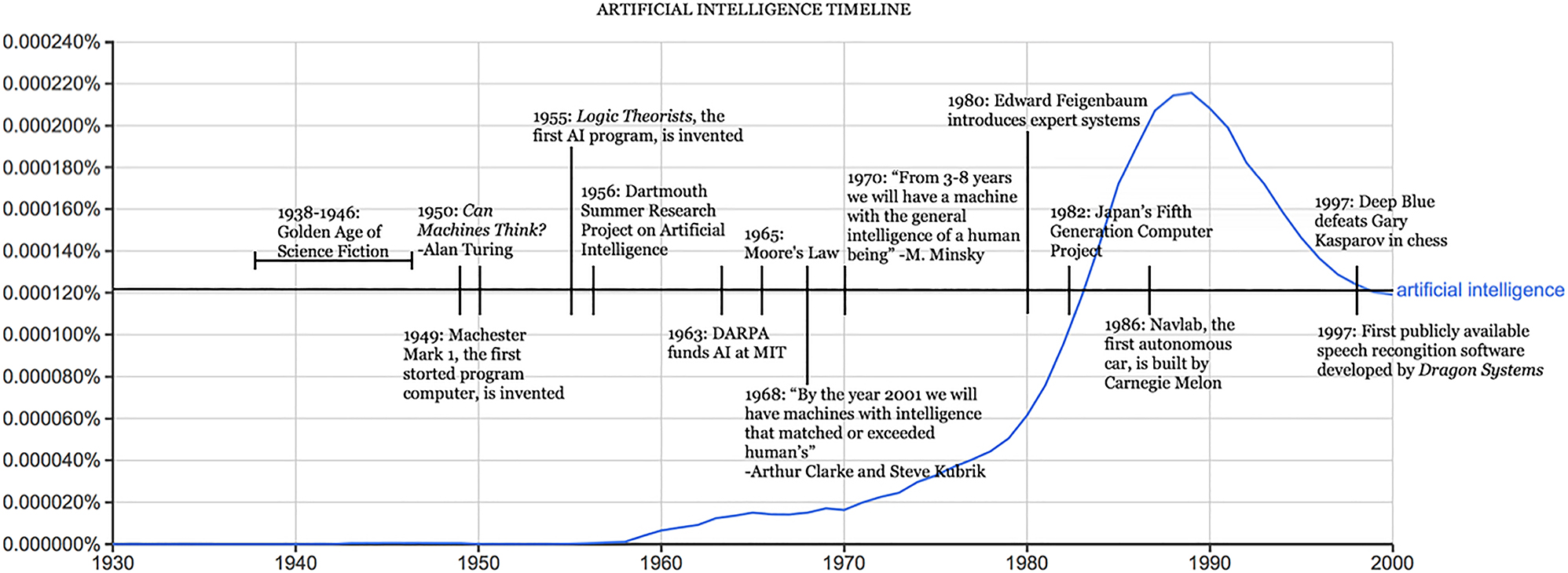

The course begins by defining the concept of AI. Establishing a shared understanding of AI is essential to prevent misconceptions and ensure clarity throughout the course. This is critical because AI is often sensationalized in the media, leading to both inflated expectations and unnecessary fears. By grounding the discussion in the seminal moments of AI’s history, such as the Dartmouth Conference of 1956 (Russell and Norvig 2016), students are better equipped to appreciate the gradual evolution of the field. This historical perspective also underscores the fact that AI is not a sudden, revolutionary technology, but rather the product of decades of research, which helps temper both over-optimism and undue anxiety. Figure 6 demonstrates the AI timeline that students will learn about in the course (Anyoha 2017).

AI development timeline (Anyoha 2017).

We followed up this historical context with a focus on the core principles of AI, focusing on key concepts such as machine learning, deep learning, and generative AI. This section aims to equip students with an understanding of how these subfields contribute to the broader AI landscape, enabling them to grasp the technical underpinnings that power contemporary AI systems. These subfields form the backbone of most modern AI applications, from recommendation algorithms to image recognition, and exploring them in detail allows students to see AI as a collection of technologies rather than a monolithic entity. Understanding these nuances is crucial in discussions about AI’s future trajectory and its potential limitations. For example, the limitations of current AI systems, particularly in terms of data dependency and interpretability, become evident when students explore how machine learning and deep learning models are trained and function.

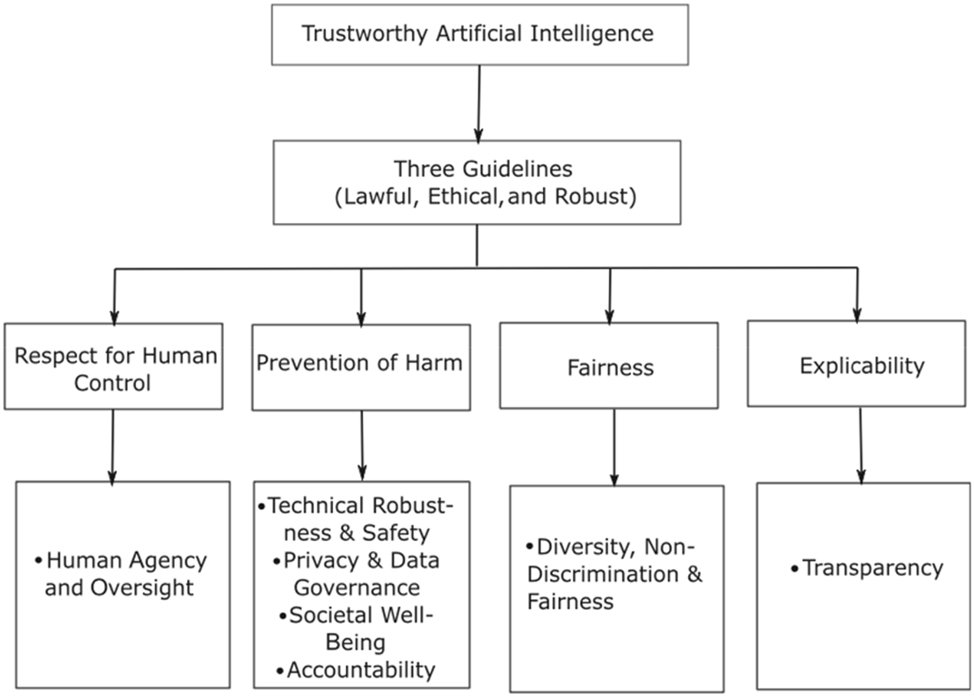

The course next addresses ethical considerations surrounding AI. As AI systems increasingly influence society, understanding their potential biases and ethical pitfalls becomes crucial. Students are introduced to the challenges of bias in AI algorithms and are guided on how to design trustworthy AI systems that promote fairness and transparency (European Commission 2019). The EU framework was introduced to students as a guideline for designing and developing trustworthy AI (see Figure 7).

Trustworthy AI framework (Kaur et al. 2022).

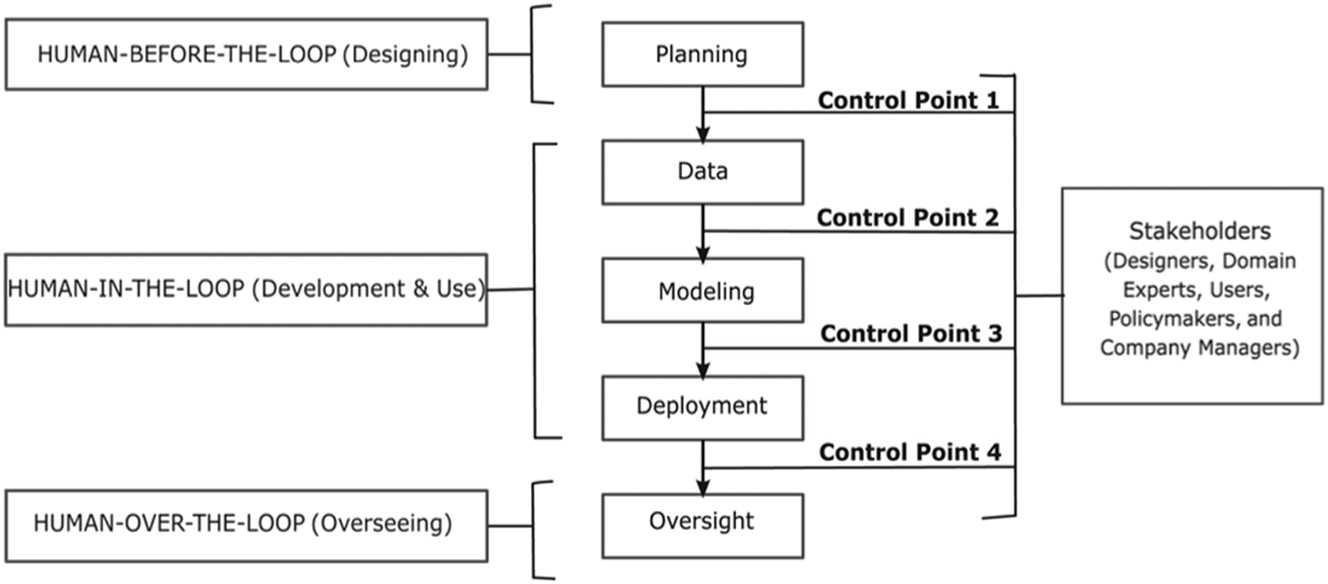

The discussion on how to design trustworthy AI systems resonates deeply with ongoing global conversations around the ethical deployment of AI technologies. We provided a “Trustworthy AI” review paper as the main resource for this part in which they recommend human involvement in AI lifecycle for the effectiveness of Trustworthy AI (Kaur 2022; see Figure 8). A critical aspect of this discussion is the awareness that biases in AI are often reflections of the biases embedded in the data on which these models are trained. This makes ethical AI design not just a technical problem, but a socio-technical one that requires interdisciplinary thinking.

Different level of human involvement (Kaur et al. 2022).

One of the most significant contributions of the course is its comparative analysis of regulatory frameworks from various global regions. This discussion allows students to see how different cultural, political, and economic contexts shape AI governance. The European Union’s stringent AI regulations, emphasizing human rights and data privacy, contrast sharply with the more innovation-driven and business-friendly approach of the United States. Meanwhile, emerging AI regulations in African countries highlight different priorities, such as economic development and the digital divide. By engaging with these global perspectives, students are encouraged to critically evaluate how AI should be governed in a way that balances innovation with social responsibility.

The course concludes with a forward-looking discussion on the potential impact of AI on society. We introduce the concept of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) and review the levels proposed by OpenAI, providing insights into what the future of AI might look like. This section also includes an analysis of the implications of AI for developing countries, the evolving nature of work in an AI-driven economy, and the transformation of education and creative industries.

The section on the potential impacts of AI provides the foundation for a larger discussion about the future of society in an AI-driven world. The introduction of AGI allows for reflection on the possible shifts in the human-AI relationship, especially in terms of autonomy and decision-making. Discussions about the future of work, particularly how automation might reshape labor markets, bring a practical dimension to the course by encouraging students to think critically about their own career trajectories in an AI-infused economy. The implications for developing countries are particularly important, as these regions face unique challenges and opportunities in adopting AI technologies. The course encourages students to think beyond the usual Western-centric focus and consider how AI could either exacerbate existing inequalities or be leveraged for sustainable development.

Moreover, the discussions on the creative industries and education illustrate how AI is not just a tool for automating routine tasks but is also reshaping human creativity and learning. By exposing students to the potential transformations in these fields, the course fosters a broader understanding of AI’s role in the future of human expression and knowledge acquisition.

In summary, this course not only equips students with a technical understanding of AI, but also challenges them to engage with the ethical, regulatory, and societal dimensions of this rapidly evolving field. It emphasizes that shaping the future of AI is a collective responsibility and encourages students to think critically about how AI can be harnessed for the public good. The course’s holistic approach, combining historical, technical, ethical, and forward-looking perspectives, ensures that students emerge with a well-rounded understanding of AI’s potential and its challenges, both for themselves and for society as a whole.

By the end of this course, participants are able to:

Grasp core AI concepts. Gain a solid foundation in the fundamentals of AI.

Understand AI’s impact on society. Explore the social and ethical implications of AI.

AI impact on future. Acquire insights into how AI might be used in different fields and affect us in future.

6 Conclusions

The way we nurture AI in its formative years will determine how it grows up. At this early stage, we have the opportunity to shape AI into a tool that aligns with societal values, ethical considerations, and the public interest. If we neglect this responsibility, however, AI may evolve into a disruptive force, becoming a ‘rebel adult’ that could profoundly and unpredictably influence our future. Given the deep and direct effects AI has on society, it is essential that society plays an active role in shaping its trajectory. This requires fostering widespread public understanding of AI’s true nature, beyond the exaggerated portrayals in science fiction or the often selective narratives promoted by technology corporations. Only through informed public engagement, education, and critical examination we can ensure that AI is developed in ways that enhance social welfare and align with the broader interests of humanity, rather than being driven solely by technological and commercial imperatives. As a result, individuals must seek knowledge from diverse sources, including scientific literature, policy discussions, and ethical debates, rather than relying on popular media or corporate messaging that may obscure the true implications and potential of AI.

To address this need, we developed two distinct courses: one aimed at younger generations in academia who lack a computer science background, and the other designed for experienced professionals in the development field. Each course is tailored to its specific audience, taking into account their prior knowledge and expertise, ensuring that participants are equipped with the tools and understanding necessary to engage with AI responsibly and effectively in their respective contexts.

While both courses aim to bridge knowledge gaps between technical fields and their broader societal applications, they differ in their specific focus and depth of exploration. The first course centers on Artificial Intelligence (AI), guiding students from foundational definitions to advanced topics like machine learning, deep learning, and Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), with a strong emphasis on ethical considerations, regulatory frameworks, and the societal impact of AI. In contrast, the second course focuses more narrowly on data science, using the Open Educational Resource (OER) format to introduce social scientists to data-driven methodologies through practical applications such as the data science lifecycle, machine learning (specifically decision trees), and real-world datasets related to poverty analysis.

A key similarity between the two is their objective to demystify complex technical concepts – AI in the first course and data science in the second – making them accessible to non-technical audiences, particularly those in social science and policy fields. Both courses also incorporate interactive activities and practical examples to help students engage with the material, ensuring that theoretical knowledge is grounded in real-world applications.

The main difference lies in the scope and emphasis: while the AI course takes a broad, multidisciplinary approach and explores global regulatory issues and future impacts of AI, the OER is more focused on providing specific tools and processes that can be directly applied to development policy. The AI course engages with more philosophical and ethical discussions about the future of technology, whereas the data science course is more practical, providing a hands-on introduction to applying data-driven approaches within the context of social sciences.

Both courses play a significant role in demystifying AI and data science, especially for non-technical audiences, by breaking down complex concepts into understandable, relatable components and focusing on the real-world implications of these technologies. In doing so, they contribute not only to education, but also to promoting public interest by empowering individuals, particularly those in policy and social science, to critically engage with AI and data science rather than viewing them as inaccessible or overly technical fields.

In both courses, the focus on public interest is clear. By providing participants with the tools and knowledge to engage with AI and data science, these courses ensure that non-technical audiences are not left behind in the rapidly evolving technological landscape. Social scientists, policy makers, and development practitioners, armed with a clearer understanding of these fields, are better positioned to advocate for ethical and equitable applications of AI and data science in their respective domains. This empowerment of traditionally underrepresented voices in the AI and data science discourse is essential for ensuring that the development and implementation of these technologies serve the broader public good rather than perpetuating existing inequalities or concentrating power in the hands of a few technology corporations.

In sum, both courses contribute to demystifying AI and advancing public interest by making complex technical concepts accessible, fostering critical discussions about the ethical and societal implications of AI, and providing non-technical audiences with the knowledge they need to engage with these powerful tools in their own work. This democratization of AI and data science knowledge is crucial for ensuring that these technologies are developed and used in ways that align with the values and needs of society as a whole.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: To edit grammar and improve language for a few paragraphs.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Anyoha, R. (2017). The history of artificial intelligence. Science in the News, Available at: https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2017/history-artificial-intelligence/Search in Google Scholar

Brennen, J.S., Howard, P.N., and Nielsen, R.K. (2018). An industry-led debate: how UK media cover AI. Factsheet, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://doi.org/10.60625/risj-v219-d676.Search in Google Scholar

Broussard, M., Diakopoulos, N., Guzman, A.L., Abebe, R., Dupagne, M., and Chuan, C.-H. (2019). Artificial intelligence and journalism. JMCQ 96: 673–695, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699019859901.Search in Google Scholar

Cools, H., Van Gorp, B., and Opgenhaffen, M. (2024). Where exactly between utopia and dystopia? A framing analysis of AI and automation in US newspapers. Journalism 25: 3–21, https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849221122647.Search in Google Scholar

Eglash, R., Bennett, A., Lachney, M., and Babbitt, W. (2021). Evolving systems for generative justice: decolonial approaches to the cosmolocal. The Cosmo-Local Reader. Futures Lab, Melbourne, pp. 60–67.Search in Google Scholar

European Commission. (2019). Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. Digital Strategy. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai Search in Google Scholar

Fast, E. and Horvitz, E. (2016). Long-term trends in the public perception of artificial intelligence. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 31, https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v31i1.10635.Search in Google Scholar

Fletcher, R. and Nielsen, R. (2024). What does the public think of generative AI in the news? Report, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Oxford University Research Archive, Available at: https://doi.org/10.60625/risj-4zb8-cg87.Search in Google Scholar

Friedman, K.K., Khanmohammadi, S., Morissette, E.M., Doiron, C.W., Stoflet, R., Koski, K.J., Grimm, R.L., Ramasubramaniam, A., and Titova, L.V. (2024). Ultrafast shift current in SnS2 single crystals: structure considerations, modeling, and THz emission spectroscopy. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202400244.Search in Google Scholar

Ganj, A., Ebadpour, M., Darvish, M., and Bahador, H. (2023). LR-net: a block-based convolutional neural network for low-resolution image classification. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 47: 1561–1568, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40998-023-00618-5.Search in Google Scholar

Ganj, A., Zhao, Y., Galbiati, F., and Guo, T. (2024). Toward scalable and controllable AR experimentation. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Workshop on Mobile Immersive Computing, Networking, and Systems, pp. 237–246.10.1145/3615452.3617941Search in Google Scholar

Khanmohammadi, S., Kushnir Friedman, K., Chen, E., Kastuar, S.M., Ekuma, C.E., Koski, K.J., and Titova, L.V. (2024). Tailoring ultrafast near-band gap photoconductive response in GeS by zero-valent Cu intercalation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16: 16445–16452, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c19251.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kaur, D., Uslu, S., Rittichier, K.J., and Durresi, A. (2022). Trustworthy artificial intelligence: a review. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 55: 1–38, https://doi.org/10.1145/3491209.Search in Google Scholar

Krueger, R., Vedogbeton, H., Fofana, M., and Soboyejo, W. (Eds.). (2023). Smart villages: generative innovation for livelihood development, Vol. 2. Walter de Gruyter GmbH and Co KG, Berlin/Boston.10.1515/9783110786231Search in Google Scholar

Maleki, M. (2024). Clinical trials protocol authoring using llms. arXiv preprint arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.05044.Search in Google Scholar

Maleki, M. and Ghahari, S. (2024). Comprehensive clustering analysis and profiling of covid-19 vaccine hesitancy and related factors across us counties: insights for future pandemic responses. Healthcare 12: 1458.10.3390/healthcare12151458Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Nielsen, R.K. (2024). How the news ecosystem might look like in the age of generative AI, Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/how-news-ecosystem-might-look-agegenerative-ai.Search in Google Scholar

Russell, S.J. and Norvig, P. (2016). Artificial intelligence: a modern approach. Pearson.Search in Google Scholar

United Nations (2024). Artificial intelligence and Africa. Africa Renewal, Available at: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/march-2024/artificial-intelligence-and-africa (Accessed 24 October 2024).Search in Google Scholar

USAID (2018). Reflecting on the past, shaping the future: making AI work for international development, Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/digital-development/machine-learning/AI-ML-in-development (Accessed 21 September 2024).Search in Google Scholar

USAID (2022). Digitial development strategy, Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/Digital_Strategy_Factsheet_Feb2022.pdf (Accessed 20 September 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Zhai, Y., Yan, J., Zhang, H., and Lu, W. (2020). Tracing the evolution of AI: conceptualization of artificial intelligence in mass media discourse. Info. Discov. Deliv. 48: 137–149, https://doi.org/10.1108/idd-01-2020-0007.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Public interest technology and why it’s important to create an outlet for it?

- Interview

- Redesigning the future: how public interest technology can reclaim justice in the digital age – a conversation with PIT leader Dr. Latanya Sweeney

- Viewpoint

- Towards defining the public interest in technology: lessons from history

- Research Articles

- Examining generative image models amidst privacy regulations

- Can public interest technology serve people who have disabilities?

- Trust and Safety work: internal governance of technology risks and harms

- Black-oriented EdTech and public interest technology: a framework for accessible and ethically designed technology for K-12 students

- “The 21st century professionalization?”: online education as an instrument for bolstering individual welfare and societal equality

- Case Report

- Demystifying artificial intelligence for the global public interest: establishing responsible AI for international development through training

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Public interest technology and why it’s important to create an outlet for it?

- Interview

- Redesigning the future: how public interest technology can reclaim justice in the digital age – a conversation with PIT leader Dr. Latanya Sweeney

- Viewpoint

- Towards defining the public interest in technology: lessons from history

- Research Articles

- Examining generative image models amidst privacy regulations

- Can public interest technology serve people who have disabilities?

- Trust and Safety work: internal governance of technology risks and harms

- Black-oriented EdTech and public interest technology: a framework for accessible and ethically designed technology for K-12 students

- “The 21st century professionalization?”: online education as an instrument for bolstering individual welfare and societal equality

- Case Report

- Demystifying artificial intelligence for the global public interest: establishing responsible AI for international development through training