Abstract

Scholarship about the effectiveness of programs related to promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in college suggests that increasing the presence of marginalized students does not necessarily result in producing inclusion and a sense of belonging in science. Recruiting and retaining marginalized students in science-related fields and comparing them with students from dominant groups is assimilationist because the presence of different people does not inherently create a diverse school setting. The central goal of this viewpoint paper is to propose a holistic view of diversity at the university level. Particularly, I discuss a conceptual framework that frames diversity as a process that entails inducing, orchestrating, utilizing, valuing, and honoring the heterogeneity of ways of thinking, doing, and being of individuals to learn. To translate commitments to enact diversity in daily teaching practices, specifically in the chemistry classroom, I analyze culturally relevant pedagogy as a productive tool to encourage students and instructors to develop and leverage a robust repertoire of thoughts, practices, and identities to learn disciplinary concepts and solve problems that matter to students. To support the operationalization of diversity in science classrooms in higher education, researchers and practitioners should identify and value the coexistence of different thoughts, practices, and identities in the school to create a safe and intellectually challenging learning setting where thinking, doing, and being different is an asset toward learning.

1 Introduction

Diversity, equity, and inclusion are critical constructs that inform the current academic agenda of several universities in the U.S. To advance the social development of the country, universities are committed to fostering the representation and participation of all students, including those from historically marginalized groups (females, people with special needs, first-generation college students, indigenous communities, people of color, LGBTQIA + individuals, and people of low socioeconomic status) (hereafter called marginalized students). In the science field, faculty, students, staff, and administrators tend to frame diversity as the mere difference of observable characteristics that make individuals unique in the school setting (Goethe and Colina 2018). Based on this lens, diversity-driven interventions focus on recruiting and retaining students from different races, ethnicity, language, gender, disability, migration history, sexual orientation, etc. Administrators, faculty, and staff rely on measuring the numbers, retention, and achievements of marginalized students to examine the relative success of these interventions compared to the performance of students from dominant groups. However, measuring the numbers, retention, and achievements of marginalized students in science is an assimilationist approach to prove the benefit of diversity-focused interventions (Rogers and Pagano 2022). Critical scholars have argued that increasing the presence of marginalized students does not necessarily produce students’ inclusion, sense of belonging, or persistence in the science field (Ono-George 2019). Scholarship has shown that disparities in access and participation still exist in several disciplines, such as chemistry, despite institutional, departmental, and instructional efforts to increase the statistical representation of marginalized students in universities (Ryu et al. 2021). Restricting the access and participation of marginalized students in scientific disciplines makes these students experience the educational system as an unwelcoming space that was not designed for them (Doucette et al. 2022). The bright side of these parameters is that they shed light on critical insights and incite us to identify alternative and holistic ways of framing diversity in the U.S. higher education system. Undoubtedly, encouraging students from different backgrounds to be part of and participate in the science field is an urgent need in higher education; however, the presence of various people does not inherently create a diverse school setting (Goethe and Colina 2018). For instance, a relatively large number of marginalized students can be in a chemistry classroom, but if their ways of thinking, doing, and being are ignored and not valued, any effort related to recruiting and retaining these students is in vain. To transform the science field into a diverse learning environment, diversity-oriented interventions must be deployed in the classroom. Doing so will foster systemic changes by disrupting settled forms of teaching and researching that both maintain barriers to scientific disciplines and ignore the presence of marginalized students.

This paper provides my viewpoint on how science classrooms, in particular chemistry classrooms, can be transformed into diverse learning settings in which intentional teaching-learning and assessment processes occur. My assumption is that designing and deploying such learning environments will contribute to decreasing disparities in access and participation of marginalized students in the chemistry classroom in college. This work is organized as follows: first, I share ideas from different scholars about a need to re-frame the construct and diversity; second, I propose a conceptual framework that can function as a tool to translate diversity into teaching daily practices; third, I share examples of culturally relevant pedagogy-based activities and one example of a formative assessment instrument that promotes diversity in the chemistry classroom; lastly, I share my final thoughts and ask questions that can be addressed by researchers and educators who are interested in bringing diversity to their interventions.

Regarding my positionality, I share my point of view and reflections about diversity as a multilingual learner, Latinx educator, and scholar who focuses on chemistry education research to design, explore, and enact culturally relevant pedagogies and assessments. My identity as a scholar and instructor in higher education is also influenced by my commitment to social justice and equity. I consider that education is not a neutral process. I am critical of the issues related to power, privilege, and inclusion that are present in science education. Based on my knowledge and beliefs, I propose that problematizing our ways of conceptualizing and enacting science education is one of the multiple means that are essential to disrupting inequities and injustices in our academic institutions.

2 Reframing diversity and highlighting its importance

In the higher educational system, diversity-oriented interventions in the science field encompass the interaction of faculty, students, staff, and administrators to dismantle systemic issues that constrain student learning. To begin disrupting systemic issues through diversity-oriented interventions in the classroom, instructors and students should be guided toward re-framing approaches to develop and use diversity to learn science (de Royston et al. 2020; Gutiérrez and Rogoff 2003; Warren et al. 2020). A means to support instructors in fostering diversity in their classroom is through offering alternative ways of conceptualizing and enacting diversity in the classroom. From my own perspective and as an alternative view, I understand diversity in the classroom as a process that entails inducing, orchestrating, utilizing, valuing, and honoring the heterogeneity of ways of thinking, doing, and being of individuals to learn. Diversity is not only a characteristic but also a tool that depends on social interactions and can be developed and employed by students and instructors in a learning setting. In this vein, Goethe and Colina (2018) propose to design and employ pedagogical methods or approaches to activate diversity in the classroom. Employing such pedagogical tools can begin dismantling traditional learning settings that ignore alternative ways of thinking, doing, and being of students, particularly marginalized students (Warren et al. 2020). Instructors and students should be encouraged to represent and vocalize different thoughts, practices, and identities to introduce, irradiate, and utilize a robust set of perspectives to understand disciplinary concepts and solve problems in the classroom.

One of the benefits of eliciting and utilizing different perspectives to understand disciplinary concepts and solve problems is that it creates an intellectually challenging learning environment in which instructors and students work with their repertoire of thoughts, practices, and identities. Several scholars have shared several benefits regarding the enactment of diversity in the classroom, such as.

Individuals have the right to be valued, respected, and treated fairly, regardless of their academic performance or background. Based on this commitment, enacting diversity in the classroom involves supporting students to become visible by acknowledging, valuing, and including their lives in the process of learning (Mehta et al. 2018).

Instructors should teach students to activate and use different practices learned from cultures different from the one we belong to. In this regard, diversity entails developing awareness of a variety of ways to produce knowledge to frame teaching and learning as cross-cultural processes (Diller and Moule 2004; Rahmawati et al. 2017).

People with more diverse backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives are excellent contributors to science as a social activity. In this vein, diversity encompasses identifying, developing, and deploying forms of innovation and creativity to address needs and issues in our society (Goethe and Colina 2018; Mehta et al. 2018).

It can be noted that diversity in education requires an asset-based perspective that includes thinking about people’s differences in experiences, interests, and backgrounds as entry points to expand repertoires of ways of thinking, doing, and being related to science. However, openness to alternative thoughts, practices, and identities represents a challenge in scientific disciplines where chemistry is not the exception. To address this challenge, researchers and educators in science fields should be equipped with novel paradigms and critical reflections on what learning is according to diversity-oriented classrooms. The overarching goal is to translate commitments to employ diversity into teaching daily practices.

3 Toward a holistic view of diversity in science classrooms

Learning is “an essential life function that involves all aspects of what it means to be human (de Royston et al. 2020, p. 10).” According to this view, learning involves culturally organized activities that occur in people’s everyday lives, both inside and outside of schools. According to sociocultural approaches, learning is mediated by social interactions between oneself and both the world and other individuals. If learning encompasses all components of individuals’ lives, schools should create settings, curricula, interactions, and assessments that encourage students and instructors to leverage their culture-based thinking, practices, and identities as resources to make sense of disciplinary concepts and solve problems. In this vein, culture should be understood not only as the context in which learning happens but also as the primary resource for people to learn.

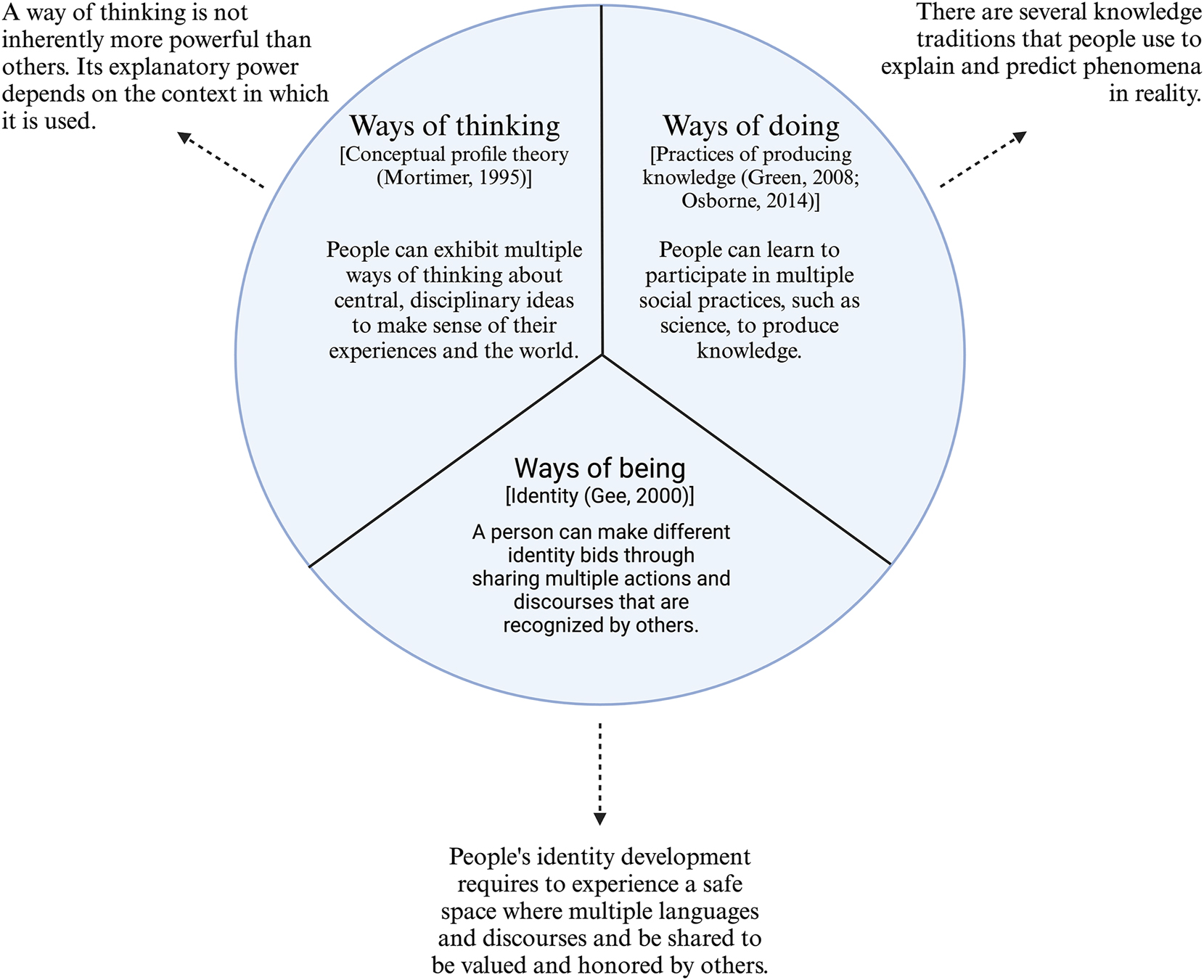

Science classrooms are complex social settings where different ways of thinking, doing, and being coexist. Classrooms are inherently diverse. Diverse ways of thinking coexist in the classrooms because there are multiple ways of knowing. These multiple ways of knowing can be described based on the conceptual profile theory (Mortimer and El-Hani 2014). The conceptual profile theory is grounded in the assumption that people have varied ways of experiencing interactions with people and the world to make sense of experiences in multiple contexts. This theory proposes to model people’s different ways of thinking through conceptual profiles. These multiple ways of thinking present in conceptual profiles are called profile zones. Each zone represents a unique way of thinking about central ideas of science, such as energy, life, and atom. People can have multiple conceptual profile zones about a disciplinary idea, but they will employ a particular way of thinking depending on the context they encounter. For instance, a person can think about energy as something that living entities use to do certain actions, as a material entity that can be stored in several systems and transferred to other systems, and as a subject of conservation, degradation, transformation, and transfer (Aguiar et al. 2018). If a person is trying to explain the function of a battery, this person can think of energy as something that can be stored in a device. If this person is talking about working out in the gym, this individual might think about energy as something that they need to lift dumbbells. It can be noted that a way of thinking is not inherently more powerful than others, it depends on the context that this particular way of thinking is used for.

Diverse ways of doing that coexist in the classroom can be understood based on multiple forms to produce knowledge (Jiménez-Aleixandre and Crujeiras 2017; Osborne 2014). According to this view, it is important that students and teachers understand different practices of knowledge production as human, social activities. Also, it is essential to understand that there are several knowledge traditions across different spaces and timescales (Green 2008). Practices of knowledge production focus on observing, experimenting, measuring, and testing entities and processes in the real world to create creative thinking and reasoning about these entities and processes (Osborne 2014). Creative thinking and reasoning function as fantastic tools to explain and predict phenomena in the real world. For example, knowledge traditions have used analogies to explain and predict observable phenomena. In Palikur (indigenous people located in Brazil and French Guiana) astronomy, to explain the relationships between constellations’ annual movements and seasonal rains, constellations are represented as boats of shamans who bring seasonal rains (Green 2008). In chemistry, to explain the octet rule in Lewis dot structures, the use of metaphors is common to describe that carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and fluorine “want” to attain eight electrons around them. These analogies and metaphors are powerful in specific contexts and purposes.

Diverse ways of being that coexist in the classroom can be grasped through frameworks about identity that are grounded in the actions and languages of individuals (Gee 2001). A person irradiates their personality through communicating and acting with others. According to this framework, a person can show their identity as a student by being in class on time and employing academic vocabulary to participate in the classroom (Wade-Jaimes et al. 2023). This action-language move is called an identity bid (Gee 2001). Following the example, the student-related identity of this person must also be acknowledged implicitly or explicitly by others in the person’s life. In this vein, an instructor can ask a student questions to share their thinking with the whole group and praise the student in class. These two dimensions are essential in identity development. In the science classroom, there are several students who want to become professionals in their fields. If a student is sharing actions and discourses that relate to specific scientific sub-fields with their instructor and/or peers, these identity bids should be valued, legitimized, and honored in the classroom.

To offer an overarching view of this holistic view of diversity, Figure 1 shows a conceptual framework that integrates the theoretical frameworks that support the idea of reframing diversity as a process that entails inducing, orchestrating, utilizing, valuing, and honoring the heterogeneity of ways of thinking, doing, and being of individuals to learn. The purpose of this conceptual framework is to make the operationalization of diversity in higher education classrooms more accessible for instructors and students. The frameworks that are part of this conceptual framework are an illustration of how critical and humanizing perspectives can be employed to expand our understanding of diversity in practice.

Conceptual framework to operationalize a holistic view of diversity in science classrooms.

4 Teaching and assessment tools to enact diversity in chemistry college classrooms

To make the operationalization of diversity in higher education classrooms more accessible and concrete, I propose the example of chemistry classrooms. The main goal is for us to think about possible entry points for translating commitments to diversity into daily teaching and assessment practices. I propose the case of chemistry classrooms because chemistry curriculum and assessments in many universities in the U.S. may not have an emphasis on eliciting, revealing, and using students’ thoughts, practices, and identities related to their culture, perspectives, and experiences (Sanders Johnson 2022). Also, instructors in chemistry lectures and laboratories rarely promote discussions about students’ lives because it might be thought of as irrelevant or unnecessary to teach and learn disciplinary concepts and solve problems (Goethe and Colina 2018). As Zollman (2012) stated, scientific disciplines should “go beyond learning for knowing and doing to learning to live together and learning to be (p. 15).” This view of learning emphasizes the need to respect students’ lives and their various repertoires of thinking, doing, and being to participate in science. While social science classrooms have illuminated teaching-learning and assessment approaches that recognize individuals’ cultural backgrounds as a cornerstone to producing knowledge in the classroom, this relative openness is still a challenge in chemistry education (Goethe and Colina 2018). Chemistry instructors and students encounter several challenges when framing classrooms as spaces in which heterogeneity of thoughts, practices, and identities are vocalized, represented, and employed to teach, learn, and assess sense-making. In this regard, chemistry, as well as several scientific disciplines, encounter a critical challenge: Make instructors and students engage in inclusive instructional units, activities, experiments, and assessments that connect to students’ repertoire of thoughts, practices, and identities to transform the chemistry classroom into a safe and diverse setting where everyone can learn from each other (de Royston et al. 2020).

A means to transform the chemistry classroom into a diverse setting is through employing culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings 1995). Culturally relevant pedagogy (CRP) is a pedagogical approach that engages diverse students in learning through recognizing and utilizing their differences as essential components of instruction and assessment. CRP requires instructors to shift from ignoring students’ lives to embracing their potential contributions and assets to participate in the learning process in the classroom. According to this perspective, instructors are encouraged to design and create an inclusive learning environment in which a variety of thoughts, practices, and identities can be vocalized and leveraged. CRP includes several components of teaching, such as curriculum content, learning context, classroom environment, student-teacher interactions, instructional activities, and assessment instruments. For instance, in a general chemistry course, instructors and students can set a culturally relevant learning context by discussing how polymerization was produced in Mesoamerican cultures (Pliego and Bloxham 2023). In a general, organic, or material chemistry classroom, instructors can share with students that the Mayan people were the pioneers to begin contributing to polymer production. Mayans worked with rubber from rubber trees and mixed them with juice from different plants, such as morning glory, to produce different elastic materials. One of these elastic materials enabled them to produce rubber balls. Rubber balls were utilized to play the Mesoamerican ball game with religious purposes in pre-Hispanic civilizations. Based on this specific activity, instructors can promote different ways of doing and being in science. Instead of introducing polymerization chemistry with the example of Goodyear’s work as an industrial process, instructors can leverage knowledge traditions from ancient civilizations that have contributed to the synthesis of new materials for our society. Also, it is a fantastic entry point to promote Hispanic students’ ways of being by making them proud of their heritage, as well as empowering them to think of themselves as and externalize their identity bids about being potential scientists/inventors in the field.

There are several examples in the chemistry education research literature that instructors can draw from to implement CRP in their classrooms to promote diversity. Collins et al. (2023) propose to design and deploy storytelling as a pedagogical tool to teach general chemistry. An illustrative approach involves integrating the stories of scientist of color and their contributions to chemistry content knowledge. The authors suggest using a fictional element, Vibranium (Vb) (Collins and Appleby 2018), an element shown in the Black Panther movie, to teach periodic trends. Students are asked where to locate Vb on the periodic table if the element has an atomic number of 119. Based on the overarching prompt, students can be encouraged to think about electron configuration, quantum numbers, atomic numbers, atomic structure (Bohr model), and oxidation states. It has been posited that students increased their interest in chemistry by connecting pop culture with chemistry concepts. According to the holistic view of diversity in the classroom, students can bring multiple ways of thinking about periodic properties and ways of being about their interest to learn in a general chemistry course. Another example is culturally relevant laboratory activities (Younge et al. 2022). To address students’ humanity, intersectional identities (i.e., multiple identities and how they shape social interactions), and centering black women in the creation of scientific knowledge, the authors designed and deployed several activities to bring diversity to the chemistry classroom and laboratory. One of the activities enacted in the laboratory was “Beyond the experiment,” in which students extended their understanding of the application of disciplinary concepts and practices in their community and personal lives. This activity has several stages that were related to students’ synthesis of aspirin experiment: (1) introduction to the origins of aspirin and its relation to the medicinal properties of willow black; (2) information about the baobab trees and their fruits that are highly concentrated in vitamins and used in traditional medicine, as well as how the fruits’ exportation has changed the ecosystem and economic situation of Senegal (showing the example of a cooperative of women who use the baobab to improve the economy of their community); (3) exploration of the use of natural or alternative products for pain relief in different communities by interviewing a family member of the students; (4) presentation of interview results to learn about alternative medicinal products in communities from different regions and cultures. Diverse ways of doing to relief pain emerged from the exploration of the use of natural products in students’ communities. Students shared several natural products, such as cerasee (from the Bahamas), noni juice (from Southeast Asia), soursop (from Jamaica), and peppermint oil (from the USA). This activity also enabled students to display their ways of being by collaborating with people from their community and bringing experiences, knowledge, and practices they learned from this cultural interaction. The authors claimed that the activity improved students’ cultural competence by connecting several cultures.

An example of a formative assessment that can be employed to elicit, reveal, and work with students’ ways of thinking, doing, and being is Szteinber et al. (2014) instrument for decision-making processes in chemistry. Overarchingly, formative assessments have been understood as activities (a problem, question, experiment, etc.) that are employed by instructors and students to identify, act in response to, and enhance student learning (Bell and Cowie 2001). The “GoKart” formative assessment instrument (Szteinber et al. 2014) is grounded in an evaluation task in which students are asked to decide and explain their reasons for choosing one fuel over others to power a GoKart. The fuel options are gasoline derived from petroleum, gasoline derived from wood pellets, E85 (an ethanol-gasoline blend), and natural gas. This instrument can be deployed by instructors to elicit, reveal, and move forward students’ ways of thinking, doing, and being about chemical identity and benefit-cost-risks related to fuels. The GoKart formative assessment instrument can elicit students’ ways of thinking of fuels as substances with different chemical structures and bonds with different enthalpies, reactants that participate in combustion reactions, agents of pollution that affect the environment of the earth, or/and energy sources that impact the economy of a society. Also, by explaining their reasons for choosing a fuel over the other options, student can share their ways of doing by employing knowledge traditions that evaluate systems depending on the source where they can be obtained. For instance, natural gas might be perceived as friendly to the environment because of the word “natural,” gasoline as a substance that should be avoided based on climate change news in social media, and/or E85 as a substance that has “a perfect balance” between a fuel that can be obtained from sugarcane (ethanol) and gasoline. Regarding ways of being, the instrument can elicit and reveal students’ identities toward being scientific professionals who frame the evaluation of benefits-costs-risks of several systems. For instance, a student can share discourses and actions about being a potential green scientist who pays attention to natural gas and E85 because of the relationships that methane and ethanol have with sustainable ways of producing fuels; on the other hand, another student can make identity bids to share their ways of being as a potential economist-scientist who pays attention to the input and output cost of producing and burning gasoline as the most effective system to power vehicles. The responsibility of the instructor is to put into dialogue students’ repertoire of thoughts, practices, and identities to make them aware of the pragmatic value of their learning and empower their participation in society.

5 Envisioning positive changes: an overarching reflection about reframing diversity in the college science classroom

Science is an excellent tool to address serious challenges that human beings face in this world. For instance, to help our society, chemists work on mitigating global warming, controlling pandemics, ceasing hazardous waste, among others. Regarding chemistry education, instructors focus on teaching concepts, practices, and identities to guide students through learning how to analyze, synthesize, and transform matter (Sevian and Talanquer 2014). However, is this teaching approach a potential tool to bring diversity to the classroom? Our society is currently facing new paradigms about practices of knowledge production (e.g., the use of AI) and self-identity (e.g., gender identity), to mention a few of them. These new paradigms and the culture of a society influence the way science is conducted to address our needs and issues. If research is shaped by these social phenomena, then science education should attend to the present and future of our society. In his article “Chemistry: Who are you? Where are you going? How do we catch up with you? [translated from Spanish]”, Talanquer (2009) shared his chemistry education perspective by thinking that we (instructors) learned 19th century-related chemistry content in the 20th century and aim to teach students who are currently living in the 21st century.

If someone asks me to describe society in this current century in one word, I will say “diverse” without hesitation. I do not think that diversity emerged suddenly in our society; I do think diversity has always been there, but we are more aware of it now. We see not only its importance and benefits but also the challenges and tensions that are involved in having a variety of entities, processes, and events in our lives. For many years in science education, we have tended to ignore diversity. It is when we ask students to engage in problem-solving or project-based learning that we expect them to use their repertoire of thoughts, practices, and identities to propose a solution. However, we tend not to explicitly teach them how to use diversity in the science classroom. To navigate the higher education system, students tend to sacrifice essential parts of their humanity to be recognized as legitimate and active participants in the classroom (Warikoo and Carter 2009). For this reason, we should think of diversity as an asset instead of a deficit. Instructors should be aware of their students’ repertoires of ways of thinking, doing, and being to design and deploy pedagogical tools that can activate diversity in the classroom (Goethe and Colina 2018).

Answering the above question about whether it is productive to teach students how to analyze, synthesize, and transform matter to activate diversity in the classroom, my answer is ‘yes’; however, we should be intentional about what, how, and why we teach chemistry. Instead of teaching a collection of isolated disciplinary topics and models, we should teach chemistry as a practice (Sevian and Talanquer 2014). Teaching chemistry as a practice will enable students to develop and use their multiple ways of doing to analyze, synthesize, and transform matter. It will center chemistry as a social practice to produce knowledge. Think about the example of natural products or alternative remedies that students’ communities have used to relieve pain. Students’ communities are engaged in the practices of analyzing, synthesizing, and transforming matter. This can enable students to be aware of multiple knowledge traditions and social practices to generate knowledge. Alternative methods of analysis, synthesis, and transformation of substances can enable students to use their repertoire of ways of thinking to evaluate the benefit-cost-risk (Banks et al. 2014) of these procedures. Think about the example of Vibranium, a fictitious chemical element that can enable students to predict properties (based on periodic trends) and applications based on the movie; students can evaluate the benefit-cost-risk of Vibranium employing both their chemistry- and Black Panther-related thoughts. Learning about how their own community analyzes, synthesizes, and transforms matter can empower students to develop science identities that they can use to become what they want to be. Recall the example of Mesoamerican polymerization methods; students’ communities (e.g., Hispanic groups) have been engaged in analyzing, synthesizing, and transforming matter for centuries. This can help students position themselves as potential scientists who are able to create methods to change the lives of people (including themselves).

The ideas and voices of those who are promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion through the interaction among faculty, students, and staff must seek to translate their commitments into every single layer of the higher education system: the institution itself, departments/centers, and classrooms. Regarding the science classroom, I consider that the first step for us as instructors is to humanize our teaching practice by identifying the inherent heterogeneity of social interactions that occur in our classroom. Instructors and students frame the classroom in different ways. We tend to privilege one single voice in science, the voice of the correct answer; however, the problems students will solve in their future work lack correct answers. It is when we identify and analyze alternatives that our decision-making process becomes clearer. The same occurs when learning. It is when we see alternative ways of thinking, doing, and being in science that our problem-solving approaches are diversified. The coexistence of different thoughts, practices, and identities is essential not only to solve problems in real-world scenarios but also to learn to live together and learn from each other.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Aguiar, O., Sevian, H., and El-Hani, C.N. (2018). Teaching about energy. Application of the conceptual profile theory to overcome the encapsulation of school science knowledge. Sci. Edu. 27: 863–893, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-018-0010-z.Search in Google Scholar

Banks, G., Clinchot, M., Cullipher, S., Huie, R., Lambertz, J., Lewis, R., Ngai, C., Sevian, H., Szteinberg, G., Talanquer, V., et al.. (2014). Uncovering chemical thinking in students’ decision making: a fuel-choice scenario. J. Chem. Educ. 92: 1610–1618, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00119.Search in Google Scholar

Bell, B. and Cowie, B. (2001). The characteristics of formative assessments in science education. Sci. Educ. 85: 536–553, https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.1022.abs.Search in Google Scholar

Collins, S.N. and Appleby, L. (2018). Black Panther, vibranium, and the periodic table. J. Chem. Educ. 95: 1243–1244, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00206.Search in Google Scholar

Collins, S.N., Steele, T., and Nelson, M. (2023). Storytelling as pedagogy: the power of chemistry stories as a tool for classroom engagement. J. Chem. Educ. 100: 2664–2672, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.3c00008.Search in Google Scholar

Diller, J.V. and Moule, J. (2004). Cultural competence: a primer for educators. Wadsworth, Belmont, California.Search in Google Scholar

Doucette, D., Daane, A.R., Flynn, A., Gosling, C., His, D., Mathis, C., Morrison, A., Park, S., Rifkin, M., and Tabora, J. (2022). Teaching equity in chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 99: 301–306, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00415.Search in Google Scholar

de Royston, M.M., Lee, C., Nasir, N.S., and Pea, R. (2020). Rethinking schools, rethinking learning. Phi Delta Kappan 102: 8–13, https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721720970693.Search in Google Scholar

Gee, J.P. (2001). Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Rev. Res. Educ. 25: 99–125.10.2307/1167322Search in Google Scholar

Goethe, E.V. and Colina, C.M. (2018). Taking advantage of diversity within the classroom. J. Chem. Educ. 95: 189–192, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.7b00510.Search in Google Scholar

Green, L.J.F. (2008). ‘Indigenous knowledge’ and ‘Science’: reframing the debate on knowledge diversity. Archaeologies 4: 144–163, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-008-9057-9.Search in Google Scholar

Gutiérrez, K.D. and Rogoff, B. (2003). Cultural ways of learning: individual traits or repertoires of practices. Educ. Res. 32: 19–25, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x032005019.Search in Google Scholar

Jiménez-Aleixandre, M.P. and Crujeiras, B. (2017). Epistemic practices and scientific practices in science education. In: Taber, K.S. and Akpan, B. (Eds.). Science education: an international course companion. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam, pp. 69–80.10.1007/978-94-6300-749-8_5Search in Google Scholar

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 32: 465–491, https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465.Search in Google Scholar

Mehta, G., Yam, V.W.W., Krief, A., Hopf, H., and Matlin, S.A. (2018). The chemical sciences and equality, diversity, and inclusion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 57: 14690–14698, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201802038.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mortimer, E.F. and El-Hani, C.N. (2014). Conceptual profiles: a theory of teaching and learning scientific concepts, Vol. 42. Springer Science & Business Media, Dordrecht.10.1007/978-90-481-9246-5Search in Google Scholar

Ono-George, M. (2019). Beyond diversity: anti-racist pedagogy in British History departments. Women’s Hist. Rev. 28: 500–507, https://doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2019.1584151.Search in Google Scholar

Osborne, J. (2014). Teaching scientific practices: meeting the challenge of change. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 25: 177–196, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-014-9384-1.Search in Google Scholar

Pliego, D.A. and Bloxham, J.C. (2023). Hispanic excellence in chemical engineering: practical examples for the classroom. Educ. Chem. Eng. 42: 61–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ece.2023.01.001.Search in Google Scholar

Rahmawati, Y., Achmad Ridwan, N., and Nurbaity (2017). Should we learn culture in chemistry classroom? Integration ethnochemistry in culturally responsive teaching. AIP Conf. Proc. 1868: 030009, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4995108.Search in Google Scholar

Rogers, R. and Pagano, T. (2022). Catalyzing the advancement of diversity, equity, and inclusion in chemical education. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 52: 3–8.10.1080/0047231X.2022.12315654Search in Google Scholar

Ryu, M., Bano, R., and Wu, Q. (2021). Where does CER stand on diversity, equity, and inclusion? Insights from a literature review. J. Chem. Educ. 98: 3621–3632, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00613.Search in Google Scholar

Sanders Johnson, S. (2022). Embracing culturally relevant pedagogy to engage students in chemistry: celebrating black women in the whiskey and spirits industry. J. Chem. Educ. 99: 428–434, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00504.Search in Google Scholar

Sevian, H. and Talanquer, V. (2014). Rethinking chemistry: a learning progression on chemical thinking. Chem. Educ. Res. Prac. 15: 10–23, https://doi.org/10.1039/c3rp00111c.Search in Google Scholar

Szteinber, G., Balicki, S., Banks, G., Clinchot, M., Cullipher, S., Huie, R., Lambertz, J., Lewis, R., Ngai, C., Weinrich, M., et al.. (2014). Collaborative professional development in chemistry education research: bridging the gap between research and practice. J. Chem. Educ. 91: 1401–1408, https://doi.org/10.1021/ed5003042.Search in Google Scholar

Talanquer, V. (2009). Química: ¿quién es, a dónde vas y cómo te alcanzamos? Educación Química 20: 220–226, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0187-893x(18)30056-9.Search in Google Scholar

Younge, S., Dickens, D., Winfield, L., and Sanders Johnson, S. (2022). Moving beyond the experiment to see chemists like me: cultural relevance in the organic chemistry laboratory. J. Chem. Educ. 99: 383–392, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00488.Search in Google Scholar

Wade-Jaimes, K., Ayers, K., and Pennella, R.A. (2023). Identity across the STEM ecosystem: perspectives of youth, informal educators, and classroom teachers. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 60: 885–914.10.1002/tea.21820Search in Google Scholar

Warikoo, N. and Carter, P. (2009). Cultural explanations for racial and ethnic stratification in academic achievement: a call for a new and improved theory. Rev. Educ. Res. 79: 366–394, https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308326162.Search in Google Scholar

Warren, B., Vossoughi, S., Rosebery, A.S., Bang, M., and Taylor, E.V. (2020). Multiple ways of knowing: Re-imagining disciplinary learning. In: Nasir, N.S., Lee, C.D., Pea, R., and McKinney de Royston, M. (Eds.). Handbook of the cultural foundations of learning. Routledge, New York, pp. 277–294.10.4324/9780203774977-19Search in Google Scholar

Zollman, A. (2012). Learning for STEM literacy: STEM literacy for learning. Sch. Sci. Math. 112: 12–19.10.1111/j.1949-8594.2012.00101.xSearch in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Fostering a new field of integrated global STEM

- Research Articles

- Manufacturing sustainable composite building materials: from waste, to the lab, to the community

- Making exploratory search engines using qualitative case studies: a mixed method implementation using interviews with Detroit Artisans

- What do college students think about artificial intelligence? We ask them

- Viewpoints

- Environmental effects of plastic pollution and sustainability: where are we now?

- Re-framing and enacting diversity in science education: the case of college chemistry classrooms

- Case Report

- Imagining just futures through interdisciplinary pedagogies: cultivating communities of practice across the sciences and humanities

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Fostering a new field of integrated global STEM

- Research Articles

- Manufacturing sustainable composite building materials: from waste, to the lab, to the community

- Making exploratory search engines using qualitative case studies: a mixed method implementation using interviews with Detroit Artisans

- What do college students think about artificial intelligence? We ask them

- Viewpoints

- Environmental effects of plastic pollution and sustainability: where are we now?

- Re-framing and enacting diversity in science education: the case of college chemistry classrooms

- Case Report

- Imagining just futures through interdisciplinary pedagogies: cultivating communities of practice across the sciences and humanities