Gibraltar’s streetnames: an eighteenth-century Western Mediterranean spatial practice of civilian fort-servicers

-

Daniel Weston

Abstract

This article relates Gibraltar’s historic half-oral, half-written bilingual streetname system to its eighteenth-century founding multilingual population. Using the geolinguistic concept of types of mobilities, we demonstrate the existence of communities of spatial practice who serviced forts in Gibraltar, Menorca, Ceuta and Melilla, and who predominantly hailed from Britain, Genoa, Menorca, Morocco and Portugal. We use the term ‘spatial practice’ in the sense that these speakers made recurrent journeys around Western Mediterranean forts over generations, establishing a conduit of language interchange. The linguistic feature studied here is surnames integrated into Gibraltar’s streetnames over a period of time, constituting an archaeological trace of a subset of British Gibraltar’s founding families. Gender is implicated in this account, as the Llanito (the contact variety of Spanish spoken in Gibraltar) streetnames were transmitted by Spanish women who married Gibraltarians, creating Gibraltarian hispanophone domestic environments. These are now in the process of being lost as the older generation has ceased speaking Llanito to children, a consequence of Franco’s closure 1969–1985 of the land-border. This loss of cultural heritage is significant as the concept of a historical Gibraltarian identity is challenged whenever politicians question Gibraltar’s sovereignty. Our analysis demonstrates that the continuity of a cohesive tricentenarian community is audible (if only partially visible) in its bilingual streetscape.

1 Introduction

In common with other British territories such as the Channel Islands, or former colonies such as Hong Kong, Gibraltar has a bilingual streetname system. Unlike these other territories, however, there is a modal disjunction between the variants: English variants are official, written on street signs, maps, and GPS systems, while Llanito variants are unofficial and oral only.[1] This modal disjunction is accompanied by a referential disjunction, as the English and Llanito variants do not typically translate each other. The street named irish town, for example, was known in Spanish as Calle de Santa Ana.[2] This system demonstrates the superimposition of British rule on a built environment established in antecedent periods of Moorish and Spanish sovereignty. It also reflects the dominance of the British garrison over the initially multilingual, then predominantly Llanito-speaking, now predominantly English-speaking, civilian population that grew up to service it. In this sense, this bilingual system indexes and particularizes how different speakerships memorialize the names of the spaces they inhabit, as shaped by asymmetries in power and status.

Unsurprisingly, given its history, Gibraltar is typically positioned as a site of dichotomies: garrison/town (Weiss Muller 2013), British/Spanish (Gold 2005), English/Spanish (Kramer 1986). In this article, we position Gibraltar as a node in a network of eighteenth-century Western Mediterranean forts. In so doing, our approach aligns itself with the tenets of lexical sociolinguistics (Wright 2023). The task of the lexicographer is to discover a word’s etymology; the task of the lexical sociolinguist is to discover what kind of speaker used that word in which social circumstances, and how it spread to other sorts of speakers. Accordingly, our overarching research questions in this paper are: how do Gibraltar streetnames demonstrate the movement of people from place to place, and how does this inform the bigger picture of Gibraltar’s linguistic history? What relevance does this have for present-day Gibraltarians? What would be lost should the Llanito variants be forgotten?

One of the advantages of taking a lexical sociolinguistics approach is that lexical influencers can sometimes be identified (Wright 2023: 102–120), a methodological affordance that is fundamental to our investigation. Our method has been to amass an onomasiological set relating to the concept of the ‘Gibraltarian streetname’. Using census data available online at the Gibraltar National Archives, we identify and plot social networks and communities of practice, and consider motivations for types of mobilities (Britain 2002, 2010). The families from Tetuan, Menorca, Genoa and other places (Tables 3 and 4) who have left their trace in Gibraltar’s onomasiological set of streetnames are identified, and their movements plotted around Western Mediterranea forts (see Section 4). We demonstrate that the personal names that appear across both the English and Llanito streetname variants memorialize the people who made a living from servicing these forts. Families went from Genoa to Fort St Philip in Menorca, then from Menorca to Gibraltar; from Tetuan and Ceuta (especially Jews, when expelled) to Gibraltar and Menorca, so that, over generations, a network of family relationships arose between these places. For example, Solomon Benzimra, a Jewish merchant recorded in the 1817 census as arriving in Gibraltar in 1782, was born in Menorca, had family roots in Tetuan, and owned residences in Gibraltar and Malta. His name occurs in Gibraltar’s Benzimra’s Alley , Benzimra Lane, Benzimra Passage, Pasage de Benzimbra, Callejon Benzimbra.[3]

We focus here on one type of mobility, spatial practice, from Lefebvre’s (1974) theory that spatial lived experience is produced socially. In Dennis’s (2009: 1) translation and interpretation of Lefebvre, representation of space is the conceptual intention of the powerful (here, the Gibraltar ministers who commission English-language streetsigns); representational space is usage regardless of planners’ intent (here, speakers continuing to use Llanito streetnames rather than English ones); and spatial practice:

[…] could be interpreted as the material expressions of these representations in action and movement: actually building an environment of boulevards or apartment blocks, or introducing regulations to control land use or manage traffic; or occupying space, not just symbolically, as in carnival, but in the practices of everyday life, the routine of the journey to work […] (Dennis 2009: 1)[4]

Significant words here are action, movement, routine. Speakers act and move, and do so repeatedly and did so historically, and this is one of the motivators for the spread of linguistic features. We interpret spatial practice to refer to the places to which individuals repeatedly journeyed. This is comparable to Dennis’s ‘routine of the journey to work’, highlighted by Britain (2012) as a significant present-day mobility – albeit in a historical context over a wider spatial and temporal range than a daily commute, with family members originating in one part of the Western Mediterranean, settling in another but remaining in contact, passing on skills, moving through the same waystations, and visiting back and forth over subsequent generations. Our understanding of ‘spatial practice’ thus merges with the notion of the ‘community of practice’ (Lave and Wenger 1991) to depict an endeavour – itinerant fort-servicing – in which members were communally engaged, and in which they developed competence over many generations.

Although our exploration of Gibraltarian streetnames draws on the principles of lexical sociolinguistics, it is also relevant to the study of linguistic landscapes. As scholars within this field have demonstrated (Jaworski and Thurlow 2010; Pennycook 2010), space and place are dynamic social constructions. Urry (2000: 149) describes place as:

a set of spaces where ranges of networks and flows coalesce, interconnect

and fragment. Any such place can be viewed as the particular nexus between,

on the one hand, propinquity characterised by intensely thick co-present

interaction, and on the other hand, fast flowing webs and networks stretched

corporeally, virtually and imaginatively across distances.

Our own investigation sees Gibraltar’s relationship with the wider Mediterranean in comparable terms. However, where the study of linguistic landscapes typically privileges semiotic, virtual and imaginative flows and networks, we are particularly concerned with the corporeal; that is to say, how and where human bodies moved, and what happened to the lexemes they took with them.

In Section 2 we provide a brief introduction to the history of British streetnames. In Section 2.1, we outline Gibraltar’s socio-political history and orography, and how these brought about its streetname system. In Section 2.2 we describe the impact of this socio-political history on the repeopling of British Gibraltar, and how this community came to service the garrison. This provides context for Section 3, where we present Gibraltar’s streetnames. In Section 4, we cast our gaze further afield to the forts and littorals of the Mediterranean, whose records help to situate Gibraltar as a node in the spatial practice of eighteenth-century fort-servicers. In Section 5 we highlight how women, in particular, propagated Llanito streetname variants, and how Gibraltar’s ongoing language shift from Llanito to English impacts this inheritance.

2 Introduction to streetnames

Personal-name constituents are found amongst the earliest streetnames, such as the Via Traiana named after the Emperor Trajan (98–117 CE) in whose reign the street was completed; or in an English-language context, Alwarnestret, Winchester, c.1110, ‘Æðelwaru’s Street’ (Biddle 2020: ch. 2). Ekwall (1954: 41–2) shows that the earliest streetnames in English record navigational perspectives, as shown in Table 1.

Navigational perspectives in some early English streetnames.

| Geographical destination | e.g. wistræt, Canterbury, 868 CE, ‘street leading to Wye’ |

| Geographical position | e.g. norðstræte, Winchester, 901–4 CE, ‘north street’ |

| Activities and occupations of those who worked in the street | e.g. ceap stræt, Winchester, 909 CE, ‘market street’ |

| Names of people who lived in the street | e.g. Cecile Lane, London, c.1200, after Cecile de Turri |

| Distinguishing features | e.g. Brad(e)strate, London, c.1200, ‘broad street’ |

Within Britain, its Crown Dependencies and Ireland, bilingual streetnames occur in areas where more than one historic language is or was spoken, as shown in Table 2.

A comparison of some bilingual streetnames in Britain, Crown Dependencies and Ireland.

| Irish/English | Bóthar Waterloo/Waterloo Road, Dublin, Ireland |

| Welsh/English | Stryd y Senedd/Parliament Street, Rhuddlan, Denbighshire |

| Scottish Gaelic/English | Straid Chrombail/Cromwell Street, Stornoway, Outer Hebrides |

| Manx/English | Bayr Ny Killane/Road of the Brushwood, Ballaugh, Isle of Man |

| Jèrriais/English | La Neuve Route/Victoria Road, St Aubin, Jersey, Channel Islands |

| Guernesiais/English | La Rue des Forges/Smith Street, St Peter Port, Guernsey, Channel Islands |

| Cornish/English | Stret Gwartha an Varhas/Higher Market Street, Penryn, Cornwall |

Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Cornwall, the Isle of Man, the Channel Islands, all have bilingual streetnames on streetsignage. In the case of Manx and Cornish, however, these are no longer mother-tongues but are spoken as revived languages. In modern times these bilingual streetsigns serve to assert the presence of speakerships which are now minorities in their own homelands, but in none of these areas do bilingual streetsigns carry the primary function of orientation for monolingual readers of these languages, as there are no literate natives who cannot also read English. Rather, the function of historic languages on bilingual streetsigns is one of cultural identity. Bilingual streetsigns in Britain and its Crown Dependencies nowadays are indexical of the cultural groups that have lived for centuries in these domains, regardless of the linguistic competencies of present-day speakerships: “feelings of ethnic identity, certainly when buttressed by religion or by any institutional maintenance of political or cultural traditions, or by traditional economic roles, can survive total language loss” (Le Page and Tabouret-Keller 1985: 239–40).

A multiplicity of names for one road is not, in itself, an unusual linguistic phenomenon. Wright (2023) illustrates this with the creation in 1970 of a new motorway through London which at the time of opening had managed to acquire four names. Three of these constitute representations of space names (here, governmental townplanners): The London to Fishguard Trunk Road (A40), used in legislation; The A40(M), used on roadsigns and by radio commentators broadcasting about traffic, and The Westway, used on maps and streetsigns; plus a representational space name (here, local residents): the elevated road. The longer a road is in existence, the more scope there is for it to acquire multiple names. In Spain, representations of space names have changed in line with the political sympathies of the governing classes. Streets honouring General Franco and his supporters 1939–1979 have been renamed by successive democratic governments – yet streets honouring King Juan Carlos I, who is credited with aiding the transition to democracy, have also been renamed due to recent disapproval of his comportment (e.g. Avenida Juan Carlos 1 in Salburua, Gasteiz/Vitoria was changed to Avenida de 8 de Marzo in 2020). Left-wing townhalls use Law 52/2007 Ley de Memoria Histórica (‘Historical Memory Law’) to justify changing streetnames they find disagreeable, and subsequent right-wing townhalls then use the same law to change them back again (Guilat and Espinosa-Ramírez 2016; González Faraco and Murphy 1997).

Since the nineteenth-century expansion of the built environment, a new ideological naming-motivation has come into being where ‘X’s street’ preserves the memory not of someone who lived in the street but an unaffiliated personage who was admired by officialdom, e.g. Raglan Street, Kentish Town, London, named after Lord Raglan who commanded the British Army in the Crimean War (died 1855, street built shortly thereafter), and the acts of such personages, such as Trafalgar Square, 1805, after the Battle of Trafalgar, 1805. In twentieth-century Gibraltar, male British politicians were commemorated in this way: Winston Churchill Avenue, Sir Herbert Miles Road, Dudley Ward Way. In the later twentieth century the streetname as act of social justice came into being, e.g. Mandela Close, London Borough of Brent, 1981, commemorating the African nationalist resistance-fighter Nelson Mandela, who was imprisoned at the time. The naming of streets as an act of social justice is not representational space naming as it does not spring from community usage, but neither is it an uncomplicated representation of space naming as it is often bestowed by local officialdom in opposition to the party in power – in the case of Mandela Close, Brent, by the Labour Party; and in the case of Avenida de 8 de Marzo in Salburua, by the Mayor, a member of the Basque Nationalist Party. We return to streetnaming as act of restitutional social justice in Section 4.

2.1 Historical context of Gibraltar’s bilingual streetnames

The Rock of Gibraltar was known in antiquity as Mons Calpe, one of the two pillars of Hercules. It is a Jurassic limestone promontory, just under half a kilometre in height (426 m), tapering on its Western side where the majority of inhabitants have always resided. The name Gibraltar derives from Jabal (‘mount’) Ṭāriq, honouring Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād who captured the peninsula in 711. The first permanent settlement was built by Moors in the twelfth century. Control passed back and forth between the Moors and various Spanish kingdoms until 1462, when Gibraltar was conclusively captured, becoming part of the now-united Kingdom of Spain in 1501 (Finlayson et al. 2024: 193, 281).

The transition to British rule was heralded by the Anglo-Dutch annexation of Gibraltar in August 1704 and legalized in the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713. British rule represented an abrupt severing of the Rock’s socio-political ties with Spain at every level. Owing to anxieties about mistreatment by Anglo-Dutch Protestant troops, nearly the entire population of Spanish Gibraltar – over 5,000 people – departed the Rock upon its annexation, fleeing to the Campo de Gibraltar and leaving just 25 Spanish and Genoese families and their servants, plus a few others and some Catholic clergy (Ballesta Gómez 2007: 157; Constantine 2009: 15).

This was the first time in recorded history that Gibraltar had been definitively cut off from the surrounding region. The word Campo is Spanish for ‘field’ or ‘country(side)’ and indexes the symbiotic relationship between the resource-poor yet fortifiable Rock and its hinterland, where the former Spanish inhabitants grew their food. This contrasts with the nomenclature of military lines which emerged when British Gibraltar became partitioned from the Campo de Gibraltar, which remained under Spanish control. The Spanish military line closest to the Rock was called La Línea de Gibraltar in the eighteenth century, and is now the Spanish town of La Línea de la Concepción.

The built environment required significant reconstruction after its capture in 1704, although its basic design remains intact, as Sanguinetti’s sketched comparison of the old city in 1627 and 1973 demonstrates (Benady 1996: 8). While Gibraltarians overwhelmingly voted to remain British in a sovereignty referendum conducted in 1967 (99.64 %), they nevertheless fold their history into the Rock’s longer chronicle of habitation: General Franco’s hermetic sealing of Gibraltar in 1969 was known locally as the fifteenth siege, in a long line that stretches back to Moorish attempts to fend off Castilian forces in the fourteenth century (the first siege), as well as the equally unsuccessful attempt to repel the Anglo-Dutch invasion force in 1704 (the eleventh siege).[5]

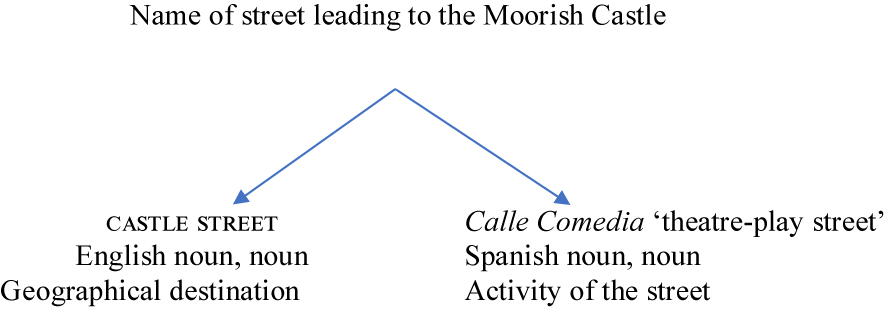

The bilingual streetname system began to emerge after the Anglo-Dutch annexation, with some variants preserved through cultural memory (see Figure 1). (Spanish Gibraltar was itself a superimposition on its Moorish antecedent: the Spanish name for the district surrounding the central thoroughfare was La Turba, perhaps from Arabic Turba al-Hamra ‘red soil’ (Benady 1996: 10).) English and non-English vernacular variants (Spanish, Genoese, Menorcan Catalan, Sephardic Jewish Haketian) would have emerged and fallen out of use over time.[6] Figure 2 is one such example with referential disjunction.

Example of a street with variants established in the respective British and Spanish eras of sovereignty.

Example of referential disjunction between a streetname’s English and Llanito variants.

Streetnames express the orography of the Rock, with generics ramp, steps, hill and specifics upper, lower, top of conveying degrees of verticality in English, and cuesta, escalera, arriba correspondingly in Llanito. Such generics contrast with the names given to streets built on land reclaimed from the sea throughout the twentieth century which have no traditional variants: a foreshadowing of the loss of historical multilingualism (for which, see Section 4).

2.2 Communities of spatial practice in early British Gibraltar

Gibraltar’s civilian inhabitants have always had symbiotic relationships: firstly, with the Campo de Gibraltar which they farmed to feed themselves, and which in turn benefitted from Gibraltar’s trade; secondly, with the military that guaranteed the civilians’ safety, and drew on their services. While the basic requirements of food and safety persisted, the populace changed completely after 1704, and as a consequence so did these relationships. From being a Spanish city in character and law, British Gibraltar was forced to look outwards towards the Mediterranean to secure supplies. The personal-name constituents in historic streetnames (Section 2) are testament to this reorientation.

Perhaps the most important feature of British Gibraltar was that its founding civilian population was far more diverse than in Spanish times. Upon the destruction of the built environment that followed the Anglo-Dutch invasion, the Prince of Hesse-Darmstadt declared Gibraltar a ‘free port’; a status it had previously held in the fifteenth century under Spanish rule (Constantine 2009: 16–17). Unlike the previous Spanish free port however, the allies’ declaration made British Gibraltar far more cosmopolitan in character as it drew its resident population from across the Western Mediterranean and beyond. The migrants who came in significant numbers were Genoese, and to a lesser extent Catalans and Menorcans, Spaniards and Jews, as well as British and Portuguese, with Maltese arriving in greater numbers during the nineteenth century. In early census records, these national groupings are amalgamated by religion: Protestants (mostly British), Jews, and Roman Catholics, all of whom were ruled by British garrison governors whose edicts were a product of autocratic whim and compliance (or not) with directives from London.

The varied national and religious groupings that comprised the founding population of British Gibraltar formed communities of spatial practice that serviced the Rock in a variety of ways, some of which were more valorized than others. This resulted in a class structure that is reflected in streetnaming practice across the assemblage of English and Spanish variants. At the top of this hierarchy came garrison governors. Each governor’s approach depended on his (always his) experience and disposition. Many were military men to the core, bringing with them experience of martial discipline and governance, as well as a resentment of the perceived impingement of the civilian residents. This attitude is exemplified in 1756 by Lord Tyrawley, who recommended that “Gibraltar … be restored to its first intention, une place de guerre: whereas it has dwindled into a trading town for Jews, Genoese and pickpockets” (quoted in Constantine 2009: 75). Yet civilian fort-servicers were a sine qua non of the garrison’s existence. What governors really objected to, as Lord Tyrawley’s comments reveal, was the foreign provenance of the civilian population. The original intention was for British Gibraltar to be peopled by British Protestants, not unlike an Iberian Portsmouth. To this end, governors enacted various prejudicial orders-in-council (local laws) to choke off the growth of resident Jews and Roman Catholics, from onerous levels of surveillance to strict controls on permits and prohibitions on owning property. These measures were, however, unsuccessful: the census of 1777 gives a total figure of 506 for (mostly British) Protestant Inhabitants, 1832 for Roman Catholics and 863 for Jews.[7]

By the early nineteenth century, governors appear to have made their peace with the resident population’s foreign ancestry, not least because the nations of the Rock had had time to prove their worth. This was particularly true of the Jewish community, which counted – along with British Protestants – among the economic elite of the civilian residents (Constantine 2009). They rose to this lofty position against all the odds. In keeping with the expulsion of Jews and Moors in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, Spain insisted that the Treaty of Utrecht include a clause explicitly prohibiting both of these peoples from residing within the new British territory. While the British government in London protested – less because of its racism and more because it resented being told what to do within its own borders – it eventually acquiesced. In practice, however, this clause was not enforced, largely because it conflicted with another clause prohibiting the import of fresh produce overland from Spain.[8] It was convenient, to say the least, to welcome North African Jews who, after annexation, came ‘daily in great numbers from Barbary, Leghorn and Portugal’ (Benady 2001b: 75). This community was vital to the wellbeing of the garrison as they had connections with Haketia (Judeo-Spanish) speaking Jews in North Africa, and could secure the requisite food supplies. Multilingual and multicultural skills elevated certain Jews into diplomatic roles between London, Gibraltar and Morocco (Benady 1997: 20; 1993: 41). But not all Gibraltarian Jews were wealthy; many performed the workaday duties that the garrison required. In this they resembled the Genoese, whose mercantile background and seafaring history also connected Gibraltar to a network of trading and familial ties. Some Gibraltar Genoese prospered financially (Finlayson 2002: 33–34), others less so (Constantine 2009: 57). The same is true of Catalan-speaking Menorcans. Like Gibraltar, Menorca had been captured by the British in 1708 during the Spanish War of Succession, and was subsequently ceded to Britain in the Treaty of Utrecht, facilitating the passage of people between these two British territories. It also led to the arrival of Menorcan priests (Crespo i Sala 2018), who tended to the spiritual needs of the Roman Catholic population without alarming garrison governors (Benady 2000: 129).

In his (1782) History of Gibraltar, López de Ayala states that the Rock’s “excellent situation makes it an Emporium for Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Ocean”. While this is true, it was also, crucially, the family and trading networks of the civilian population that made this emporium possible. In return for such service, the British garrison provided safety – hedged, it must be added, with often execrable treatment – that would have been impossible under Spanish rule. For Jews, the very right to live on Iberian soil was utterly dependent on the British. The existential threat posed by Spain is evident in the Jewish response to the sieges that characterized eighteenth-century Gibraltar. Following the thirteenth siege of 1727, for example, “The Jews were not a little serviceable, they wrought in the most indefatigable manner, and spared no pains when they could be of any advantage, either in the siege or after it” (Anonymous 1728). Although the threat to the Genoese was less ominous, Napoleon Bonaparte’s occupation of their homeland in 1805 made Gibraltar an attractive prospect. This is apparent in the influx of Genoese fleeing conscription into Napoleon’s army, and Genoese sailors seeking the protection of the Royal Navy in the form of a British Mediterranean Pass (Benady 2001a: 92–93). These passes, based on those derived from a British-Moroccan treaty, ensured Gibraltarian Genoese ships would not be fired upon by the Royal Navy, despite Genoa being reclassified as enemy (French-occupied) territory.

The Great Siege of 1779–1783 was the apotheosis of this symbiotic relationship. It posed an existential threat to both the garrison and to the resident population, many of whom left temporarily. Although Gibraltar’s built environment was almost completely destroyed (Drinkwater 1785), the rebuilding and renaming of streets commemorate civilians who served the garrison. Many civilian evacuees never returned, and yet a comparable demographic of Jews, Roman Catholics and British Protestants resettled the territory. Those who did return found prosperity, particularly during the Peninsular Wars. The genealogies of contemporary Gibraltarians typically date from this period (Finlayson 2002), as do many of the historic streetnames. These streetnames also reflect the embedding of a gendered class system that saw men from these immigrant populations flourish ahead of later arrivals, many of whom were women whose names go unsung. Benady (2001b: 97) notes that descendants of the old Genoese, Jewish-Moroccan and Portuguese gardeners, hawkers, porters and boot makers became the nucleus of the Gibraltar middle class. Constantine (2009: 63) also describes how this propertied middle class often had humble origins, but “with good luck and management (and a capacity to tolerate heat, the levanter and the manners of the garrison), one could get on”.

Such opportunities were only available to men. Spanish women – who comprised 43 % of all brides in 1834 (Sawchuk and Burke 1997: 20–2) – married mostly working-class Genoese and Portuguese men, and British soldiers (Stockey 2019). These women appear to be directly responsible for the fact that the vernacular variants in Gibraltar’s bilingual streetname system prevailed in hispanicised form. Eighteenth-century Gibraltar was a highly multilingual community, and early nineteenth-century garrison governors continued to communicate with the civilian population through bandos (proclamations) written in English, Italian and Spanish. Yet these only hint at the variety of spoken languages, which included Genoese, Spanish, English, Catalan, Haketia and Portuguese, with the Western Mediterranean lingua franca pidgin acting as a link language (Drinkwater 1785; López de Ayala 1782; Nolan 2020). It is therefore likely that the streets were known by a variety of names in a variety of different languages, but evidence for the vernacular streetname variants dates from the nineteenth century when Gibraltarian society coalesced around the use of Llanito. As Weston (2011: 349) notes, this shift towards Llanito was likely accelerated by the communal (and often cramped) living quarters and their adjacent patios, which accommodated working class families. The propagation of these hispanophone domestic environments and a fortiori the cultural hispanicization of Gibraltar was a trend that did not go unnoticed by the garrison authorities. The Governor of 1842–1844 noted that British interests in the fortress were threatened by inhabitants who “were technically British subjects because born in Gibraltar but who were Spanish by ethnic origin, family connections, language, culture, even residence and, he feared, allegiance” (Constantine 2009: 111). Successive governors tried to keep these Spanish brides out of the garrison by requiring them to give birth outside Gibraltar to ensure their children were not British according to the rights granted by jus soli. The territory’s vernacular streetnames are their linguistic legacy.

3 Sources of evidence for Gibraltar’s streetnames

Our data is gleaned from the Gibraltar National Archives censuses. In Section 2.1 we present Gibraltar’s historic English streetnames by their generic elements, a process we then repeat for Llanito.[9] Appendix 1 is a parallel list of streetnames in their English and Llanito variants, while Appendix 2 relates these streetnames to the family names of Gibraltar residents 1704–1834.

3.1 Nineteenth-century streetnames arranged by generic elements

3.1.1 Assemblage of English streetnames from 1814, 1834, 1871, 1878, 1891 censuses

Surveyed online at https://www.nationalarchives.gi/Default.aspx (accessed 29 March 2022).[10]

Alley: Benzimra’s Alley, Pitman’s Alley

Bay: Camp Bay, Catalan Bay

Court: Bedlam Court

Entrance: Giro’s Entrance

Flats: Europa Flats

Front: North Front, Prince Albert’s Front, Wellington Front

Garden: Library Garden, Rodger’s Garden, Rosia Gardens

Guard: Castle Guard

Gully: Bruce’s Gulley, Castle Gully, Upper Castle Gully, Lime Kiln Gully

Hill: Civil Hospital Hill, Cumberland Hill, Naval Hospital Hill, Rosia Hill, Scud Hill, Windmill Hill

Lane: Arengo’s Lane, Back Lane,[11] Bell Lane, Benzimra Lane, Bomb House Lane, Cannon Lane, Chicardo’s Lane, Church Lane, City Mill Lane, Cloister Lane, College Lane, Cooper(age) Lane, Cornwall’s Lane, Crooked Billet Lane,[12] Crutchett’s Lane, Engineers Lane, George’s Lane, Glynn’s Lane, Governor’s Lane, Green Market Lane, Gunner’s Lane, Hargrave’s Lane, Head Lane,[13] Horse Barrack Lane, King’s Yard Lane, Lewis’s Lane, Line Wall Lane, Lynch’s Lane, Market Lane, Mess House Lane, Ord(nance) H(ou)se Lane, Packet Office Lane, Parliament Lane, Rosia Lane, Secretary’s Lane, Serruya’s Lane, Tuckey’s Lane, Turnbull’s Lane, Victualling Office Lane

Market: Green Market, Butcher’s Market/Meat Market

Parade: Cornwall’s Parade, F(renc)h Parade, Governor’s Parade, Gunner’s Parade, Hargrave’s Parade, (New) Mole Parade, Rosia Parade, South Barracks Parade

Pass: Europa Pass

Passage: Abecasis Passage, Ansaldo’s Passage, Arengo’s Passage, Baca’s Passage, Baker’s Passage, Banasco’s Passage, Benoliel’s Passage, Benzimra Passage, Booth’s Passage, Carreras Passage, Chicardo’s Passage, Giro’s Passage, Johnson’s Passage, Lime Kiln Passage, Parody Passage, Richardson Passage, Serfaty’s Passage, Shakery’s Passage, Skinner’s Passage, Willis’s Passage, Wilson’s Passage

Place: Convent Place, Cumberland Place, Don Place, Paradise Place

Ramp: Aloof’s Ramp, Ansaldo’s Ramp, Bedlam Ramp, Blue Barrack Ramp, Boschetti’s Ramp, Castle Ramp, Castle Tank Ramp, Charles V Ramp, (Civil) Hospital Ramp, Civil Pris(on) Ramp, Cloister Ramp, Crutchett’s Ramp, Dalmaya’s Ramp, Danino’s Ramp, Fountain Ramp, Fraser’s Ramp, Gowland’s Ramp, Library Ramp, Lopez’s Ramp, Marcello’s Ramp, Morello’s Ramp, Paradise Ramp, Parliament Ramp, Play House Ramp, Prince Albert’s Ramp, Prince Edward’s Ramp, Lynch’s Ramp, Richardson’s Ramp, Rodger’s Ramp, Serruya’s Ramp, Willis’s Ramp, Wilson’s Ramp

Range: Pavilion Town Range, Back/Rear of Town Range, Town Range

Road: Arengo’s Palace Road, Castle Road, Lower Castle Road, Upper Castle Road, Centre Pavilion Road, Civil Hospital Road, Crutchett’s Road, Cumberland Road, Lower Cumberland Road, Upper Cumberland Road, Europa Road, Europa Main Road, Flat Bastion Road/Road to Flat Bastion, Road to the King’s Lime Kiln, Line Wall Road, Low r(oa)d f(ro)m the Mole/Road to the Mole, Moorish Castle Road, Naval Hospital Road, North Pavilion Road, Road leading to/from library to Prince Edward’s Gate, Prince Edward’s Road, Queen’s Road, Road to Devil’s Gap, Road to the Lines, Rodger’s Road, Rosia M(ain) Road, B(ac)k R(oa)d/Road f(ro)m Sand Pit, Scud Hill Road, South Barrack Road, South Barrack Yard Road, South Pavilion Road, Upper Road, Willis’s Road, Road to Wind Mill Hill

Row: Paradise Row

Side: Hill Side

Square: Cathedral Square, Commercial Square

Steps: Arengo’s Steps, Castle Steps, Lower Castle Steps, Upper Castle Gully Steps, Chicardo’s Steps, Crutchett’s Steps, Cumberland Steps, Palace Gully Steps, Top of Palace Gully Steps, Queen’s Street Steps, Rosia Steps, Sunny Side Steps, Upper Gully Steps

Street: Artillery Street,[14] Castle Street, Upper Castle Gully Street, Church Street, Civil Hospital Street, Cumberland Street, Engineer Street, George’s Street, Governor’s Street, Gunner’s Street, King Street, Landport Street, Library Street, Main Street, Market Street, New Street, Queen Street, South Port Street, Synagogue Street,[15] Waterport Street

Terrace: Wheatley Terrace

Town: Irish Town

Vista (borrowed into English): Buena Vista

Wall: Line Wall

Yard: Aloof’s Yard, Arengo’s Yard, Mule Yard, Old Barrack Yard, Wood Yard

Table 3 is an analysis of the specific elements.

Gibraltar English streetnames by category.

| Locational | Monarchy and military | Common English streetnames | Governors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44.4 % (91/205) | 11.7 % (24/205) | 8.8 % (18/205) | 1.5 % (3/205) |

| English civilian personal name constituents | Genoese personal name constituents | Jewish personal name constituents | Catalan/Menorcan personal name constituents | Portuguese personal name constituents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.1 % (31/205) | 10.2 % (21/205) | 4.4 % (9/205) | 2.9 % (6/205) | 1 % (2/205) |

-

(Figures in parentheses refer to the number of streetnames in a given category out of a total of 205 English streetnames.)

The military character of the Rock is amply apparent in English streetname generics such as Range, Parade, Front, Ramp, and in occupational and locational specifics such as bomb house lane, town range, horse barrack lane, flat bastion road, victualling office lane.[16] Garrison governors (hargrave’s parade , don place), and soldiers (Cornwall’s Parade, Skinner’s Passage, Willis’ Road, Wheatley Terrace) are honoured, as is monarchy (king’s street, queen street, prince edward’s road, prince albert’s front), including one holdover from Spanish rule, charles v steps (Escaleras de Carlos V) (Drinkwater 1785). In our survey of English-language streetnames 1705–1834 we count 24 ‘monarchy and military’ variants versus 69 civilian personal-name variants. Spanish surname-constituents are virtually non-existent, but across the Jewish and Genoese personal-name constituents there is evidence of the opportunities afforded to the self-made men of the early nineteenth century. For example Abecassis, Aloof, Morello, Serfaty, Serruya counted among the eighteenth-century porters of the garrison but their descendants obtained wealth via Western Mediterranean trading networks. As illustration, the census of 1784 includes Solomon Benoliel, born in Tetuan, proprietor of the Gibraltar Exchange and Commercial Library. Solomon’s son Judah became a trading magnate via his diplomatic position as Moroccan Consul General in Gibraltar (Brown 2012: 108): his banking portfolio included the financial transactions of the British Governor of Malta, his Gibraltar mansion had 18 rooms, and he ended his business career “as an international banker with clients who included the future Pope Pius IX” (Constantine 2009: 55).

3.1.2 Llanito streetnames in 1884, 1899 and 1939

The generic elements of the Llanito variants are as follows:[17]

Baños: Baños de Scotto

Calle: Calle Alta, Calle del Castillo, Calle Comedias, Calle de la Cuesta, Calle de los Cordoneros, Calle de los Cuarteles, Calle del Gobernador, Calle de la Iglesia, Calle de los Ingenieros, Calle que va a la Plazuela de don Juan Serrano, Calle de la Merced, Calle Angosta de Miguel de Ribera, Calle del Muro, Calle Peligro, Calle de la Policia, Calle Puerta Nueva, Calle Real, Calle de San Jose, Calle de Santa Ana, Calle de las Siete Revueltas, Calle Sinsalida, Calle que sube al Castillo, Calle del Vicario (Viejo)[18]

Calleja que va a la calle Alta de los Cuarteles

Callejon: Callejon del Alcalde, Callejon del Antiguo Baño, Callejon Benzimbra, Callejon de Bobadilla, Callejon de la Bomba, Callejon de los Cañoneros, Callejon del Cantarero, Callejon de la Carniceria, Callejon de Chiappi, Callejon de Cureto Mio, Callejon de Dolores Corbe, Callejon de Fonseca, Callejon de la Fuente, Callejon de la Garloza, Callejon del Horno del Rey, Callejon del Hospicio, Callejon del Jarro, Callejon del Lazareto, Callejon de los Masones, Callejon de Morello, Callejon del Moro, Callejon de la Pasiega/Paciega, Callejon del Palacio, Callejon de la Paloma, Callejon de Parody, Callejon del Perejil, Callejon de Pitman, Callejon de la Policia, Callejon de Rizo/Riso/Risso, Callejon de San Francisco, Callejon de San Juan de Dios, Callejon de Segui, Callejon Sin Sol, Callejon de Tady, Callejon del Tio Pepe

Callejuela de Zurita

Calera: La Calera, La Calera de Mr Gaya

Camino: Camino del Castillo, Camino del Pabellon Central/de los Pabellones, Camino Principal de Europa, Camino del Principe, Camino de Rod(o)ger

Cuesta: Cuesta del Ball Alley/Balili, Cuesta de mistebon/Mr. Bourn, Cuesta de Morelo, Cuesta del Castillo, Cuesta de la Cebada, Cuesta de Carlos Maria, Cuesta del Hospital, Cuesta del Sagrado Corazón, Cuesta de Sandunga/Sandura

Detras: Detras de la Iglesia, Detras de los Cuartos

Escalera: Escalera de Arriba, Escalera de Benoliel, Escalera del Caracol, Escalera de Cardona, Escaleras de Carlos V, Escalera del Espino, Escalera de Maqui, Escalera del Monte, Escalera del (H)Ospicio, Escalera de Piri

La Escalerita de Pili

Esplanada: la Esplanada

Frente: Frente al Café Universal, Frente a la Iglesia Católica, Frente a la Policia, Frente al Sailor’s Home

Huerta: Huerta de Riera

Jardin: Jardin de Glynn

Junto al Tribunal Supremo

Pasaje: Pasage de Benzimra, Pasaje de Giro, Pasaje de Johnston, Pasaje de Shakery

Patio: Patio de los Caballeros, Patio Carrera, Patio del Catalano

La Piazza

Plaçalito: Placalito del Convent/Convento

Plaza: Plaza de Artilleros/del Artilleria, Plaza de Cañoneros, Plaza de la Catedral (Protestante), Plaza de la Iglesia, Plaza Mayor, Plaza del Muelle Nuevo, Plaza del Tuerto, Plaza de la Verdura

Plazuela: Plazuela de los Artificers, Plazuela de Artilleros, Plazuela de los Ingenieros, Plazuela de don Juan Serrano, Plazuela/Plaza del Martillo, Plazuela de San Juan de Letrán

Puerta: Puerta del Gobernor, Puerta de la Mar, Puerta Nueva, Puerta de San Rosario, Puerta de la Tierra

Senda: Senda del Moro, Senda del Pastor

Vista: Buena Vista

Table 4 is an analysis of the specific elements.

Llanito streetnames by category.

| Locational | Common Spanish streetnames | Activity/character associated with the street | Catholicism | Monarchy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39.9 % (50/126) | 15.9 % (20/126) | 12.7 % (16/126) | 5.6 % (7/126) | 0.8 % (1/126) |

| Iberian personal name constituents | Genoese personal name constituents | English personal name constituents | Jewish personal name constituents | Other/unknown personal name constituents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.7 % (11/126) | 7.9 % (10/126) | 4 % (5/126) | 3.2 % (4/126) | 1.6 % (2/126) |

-

(Figures in parentheses refer to the number of streetnames in a given category out of a total of 126 Llanito streetnames). Total number of streetnames = 126. Combined percentages do not equal 100% due to rounding.

Most of the Llanito variants were neonyms introduced by civilians under British rule, with a few holdovers from the era of Spanish sovereignty – Calle de las Siete Revueltas repeats over 40 times in Spain (Weston and Wright 2025). Orography is apparent in generics Cuesta ‘rise’ and Escaleras ‘steps’. Specifics are occupational (Callejon de la Carniceria), locational (Calle de la Iglesia), and related to the fort (Callejon de la Bomba, Callejon de los Cañoneros). These similarities notwithstanding, the assemblage of Llanito variants differs in certain respects from the English counterparts. The Catholic faith of Gibraltar’s resident majority is apparent: Calle de San Jose, Calle de Santa Ana, Callejon de San Francisco, and commensurately missing from the English variants. Llanito streetnames are also richer in affect than the English variants. Affect with regard to the linguistic landscape is defined as “states or capacities that would not be prototypically considered emotions. Such states or capacities include being socially resilient” (Wee 2016: 107). Social resilience is exemplified by civilians ignoring the garrison (Flat Bastion Road) and registering instead the usefulness of Mr Bourn’s shop (Cuesta de Mistebon), remaining oblivious to the activities of the militia (Horse Barrack Lane) but being aware of a civilian’s residential tenement (Patio del Catalano), and by disregarding official commemoration altogether (Cuesta de Carlos Maria instead of Prince Edward’s Ramp).

A striking feature of the Llanito variants is the way they capture the life and voices of the street. While the English variants comprise Fronts and Parades named after grand Dukes and Princes who might never have visited the territory, there is little reference to these in the Llanito streetnames, which depict instead the characters and types who inhabited its passages and alleyways, including Callejon del Moro ‘the Moor’s alley’, Callejon del Tio Pepe ‘Uncle Joe’s alley’ (a hypocoristic form of José), and Cuesta de Mistebon (‘Mr Bourne rise’), whose pronunciation reflects the assimiliation of an English name to the Llanito of the streets. It is telling that while very few streetnames are named after women, only the ramp which is likely to have been named after the Widow Fraser is in English. In the case of Callejon de Dolores Corbe (Lime Kiln Road), it is also likely that the honorand’s probable Spanish heritage is obscured through patronymic naming customs, perhaps here from the Savoyard Corbeille. If so, this is a foreshadowing of how the Rock’s Spanish foremothers have been erased from cultural memory (see Section 5).

These streetnames are broadly testament to the lived experience of the civilian residents, overlapping with that of the garrison as the common military referents attest, but diverging in ways that have led to linguistic doublets. Library Ramp, for example, is where the Garrison Library stands, yet civilian residents were denied membership. They were aware instead of the racquet club in the vicinity, leading to the variant Cuesta de Balalí (‘ball alley rise’). The non-British social elite occupied an important position in this respect. First, as civic intermediaries between the governors and the resident population they would have used both variants, just as they were familiar with the concerns of both sections of the community. This intermediary role was a vital function in Gibraltar, where garrison governors feared the allegiances of a resident population they barely tolerated, and whom they considered antithetical to the Rock’s military raison d’être. This also explains why the Llanito vernacular variants include only a smattering of English personal name constituents (4 %), compared with a higher number of Iberian (Portuguese, Menorcan Catalan, Spanish) and Genoese names (approximately 20 % in total). Monolingual English speakers were simply less central to the everyday lives of the resident population.

4 The wider Western Mediterranean context

Gibraltarian streetnames bespeak a spatial practice of the journeys around the Western Mediterranean forts undertaken by family members over numerous generations. However, we look in vain for streetnames reflecting this spatial practice in other eighteenth-century fort locations such as Ceuta, Melilla, Menorca or Malta, as streetnames there have largely been modernized. Only Gibraltar now retains this archaeological trace. Nevertheless, family names recorded in Gibraltar’s streets continue on in these places: there are still people named Ansaldo, Risso and Parodi in Genoa; Carreras, Cardona and Giró in Menorca; although subsequent generations named Benoliel, Benzimra, Serfaty, Serruya left Morroco due to worsening conditions there for Jews. Twenty-five kilometres away across the Straits lies Ceuta, another exclave fort on a peninsula connected to a foreign mainland by an isthmus. Ceuta has been owned by Spain since 1668 (Kirschen 2014: 6) and is joined to Morocco. Eighteenth-century plans of Ceuta are labelled with vocabulary similar to that of Gibraltar.[19] Generic and specific streetname elements in modern Ceuta are also comparable with Llanito variants though they do not contain the same degree of personal names, as shown in Table 5.

Streetnames in Ceuta and Gibraltar taken from Ceuta en la Mano (1934) and the Callejero Fiscal de la Ciudad Autónoma de Ceuta (2014).

| Ceuta | Gibraltar |

|---|---|

| Calle Ingenieros | Calle Ingenieros |

| Calle Peligros | Calle Peligro |

| Cuesta del Hacho | Cuesta del Castillo |

| Esplanada Espino | La Esplanada |

| Foso de la Muralla | Las Murallas |

| Huerta de la Guarnición | Huerta Riera |

| Llano de las Damas | Europa Flats |

| Muelle de Comercio | Plaza del Muelle Nuevo, Commercial Square |

| Patio de Benasayag | Patio Moro |

| Rampa de los Abastos | Castle Ramp |

Gómez Barceló (1995: 300, 308) has surveyed the historic streetnames of Ceuta in archive records from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. They either referenced built features, such as the walls of the fortification, churches, gunpowder stores and barbican, or were navigational: Rúa que va para las Vendederas desde la Plaza; Rúa que va para la Aduana. As Ceuta had previously been owned by the Portuguese, early streetnames contained Portuguese personal names. Modern Ceuta streetnames comprise surnames that match those in Gibraltar’s early censuses: Calle Benali, Calle Benasayag, Calle/Pasaje Bentolila, Patio Hachuel, Callejon Martín Cebollino, Calle Mohamed Hamed Abderrahaman – as do the streets in nearby Tetouan named Abuderham, Benzaquen, Cazes (Ortega 1917: 278, 280). Modern Ceuta’s politicians also use streetnames as a locus of restitutional social justice – Ceuta too has its Plaza de Nelson Mandela. Gómez Barceló (2014: 266–267) reports that on 27 November 2008, the Ceuta Assembly commemorated through streetnames local citizens: José Alfón Benoliel (cf. Gibraltar’s Benoliel’s Passage, Escalera de Benoliel; the name Benoliel is recorded in Gibraltar’s census records in 1777); Fortunato Bendaham Abecasis, who was executed by the Francoist government in 1937 (cf. Gibraltar’s Abecasis Passage; Bendaham recorded in 1784 and Abecasis in 1774 in Gibraltar’s records); and Moisés Benhamú Benzaquén, who was executed by the Francoist government in 1937 (both names recorded in Gibraltar’s records in 1777).[20] The Assembly also honoured by streetname Menahem Gabizón Benhamu (Gabizon recorded in 1784 in Gibraltar’s records), and José Benoliel Bentata (Bentata recorded in 1819 in Gibraltar’s records). Thus streetnames both sides of the Straits honour members of the same families.

Like Gibraltar, the language of Ceuta’s garrison, Spanish, differs from that of its hinterland, where Darija (Moroccan Arabic) and Tamazight (Berber) are spoken. As in Gibraltar, present-day Ceuta street signage is in the language of the fort rather than the language of the mainland. Unlike Gibraltar, this is contentious because use of monolingual Spanish serves to background the Muslim population (González Enríquez 2007: 12). Fernández García, who has investigated present-day language use in both Ceuta and Melilla, reports that there are no historic streetnames in Arabic or Berber that preserve an oral streetnaming culture like Gibraltar’s.[21] Melilla’s fort lies 145 nautical miles away from Gibraltar. It was built between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries and is also owned by Spain and joined to Morocco. The language of the fort is Spanish, and the language of the hinterland is Tamazight, known in Spanish as Cherja. Historic Melillan Jewish family names that also occur in Gibraltar’s censuses include Benaim, Benhamú, Bensusan, Benzaquén, Chocrón, Hadida (Gómez Barceló 2014: 263).

Gómez Barceló (2007: 104) details how the fleeing Spanish inhabitants of 1704 were replaced by Genoese families, some of whom then travelled on after a time to settle in Ceuta. Genoese families who settled in both Gibraltar and Ceuta include Brusco, Raggio, Risso, Schiaffino (cf. Gibraltar’s Callejon de Risso). Other Genoese settled in Fort St Philip in Menorca, some of whom then travelled on to Gibraltar (Crespo i Sala 2018). Genoese families feature in Gibraltar’s Ansaldo’s Passage/Ramp, Baca’s Passage, Chicardo’s Lane/Passage/Steps, Morello’s Ramp , Callejon de Chiappi, Escalera de Piri, Los Baños de Scotto. Genoa too has a Vico Ansaldo. 571 nautical miles away from Gibraltar lies Menorca, which was under British control for most of the eighteenth century. The Castell de Sant Felip, built by the Spanish, was known in English as Fort St Philip, but its civilian settlement was re-sited in 1771 so its early streetnames are not known (Crespo i Sala 2014a: 169). The Castell de Sant Antoni was built in the seventeenth century and its civilian settlement still exists, but it was retaken by Spain in 1782 and its streetnames were modernized. By 1816, Gibraltar’s civilians counted 2,742 Spaniards, 1,818 Genoese, 1,312 Portuguese, 1,117 Britons, 410 Menorcans (Crespo i Sala 2014a: 173). Gibraltarians from Menorca that feature in Gibraltar streetnames are Solomon Benzimra (Benzimra’s Alley/Lane/Passage/ Pasaje/Callejon), Antonio Cardona (Escalera de Cardona), Sebastian Carreras (Carreras Passage), John Giro (Giro’s Passage), Francisco Sequi (Callejon de Segui).[22] The Genoese Cardona family, for example, settled in Menorca and Gibraltar (Crespo i Sala 2015: 388). Another group of Catalan-speaking early settlers came from the mainland; one such was the market-gardener Miquel Riera of Sabadell, who features in Gibraltar’s Huerta Riera (Crespo i Sala 2014b: 372). Catalan Bay is a very small settlement at the base of Gibraltar’s steep Eastern side. Finlayson et al. (2024: 60–63) discuss evidence for the origin of this name, concluding that it was bestowed some time between 1622 and 1740, deriving from seasonal fishing there by Catalans. The settlement was built considerably later between 1775–1805, although by 1805 it still consisted of no more than two stone houses with a shed and couple of outhouses. The built settlement seems to have been established by Genoese fishermen, although by 1814 Portuguese, Spanish, Italian and British as well as Genoese and native-born inhabitants are listed as resident.

5 Language shift and the loss of cultural heritage in contemporary Gibraltar

Gibraltarians are presently in the process of a language shift towards English, with knowledge of Llanito in steep decline among the youngest generation (Canessa 2019; Enriles 1992; Kellerman 2001; Levey 2008: 58; Weston 2013). Canessa (2019: 8) reports that only a minority of Gibraltarians now speak Llanito to their children. As a result, the Llanito streetname variants are falling into disuse, eradicating a system that has existed for over three hundred years. This is not a conscious act of forgetting, nor a deliberate disinheritance. The siege warfare of the eighteenth century eventually gave way to a more peaceful relationship between Spain and Gibraltar, and helped the latter to become a prosperous civil mercantile society. This was facilitated by the influx of Spanish brides, who instigated the hispanicisation of Llanito (Weston 2011). While a common language undoubtedly helped bring together the ancestrally-disparate nations of this new civil society, Gibraltarians remained keenly aware that Gibraltar was more affluent than its Spanish campo, and that this affluence was based – authoritarian caprice notwithstanding – on British sovereignty. As such, the mutual dependence that existed between the garrison and the population perdured. Yet despite the prevailing use of Llanito in the nineteenth century, we find a disavowal of Gibraltar’s Spanish ancestry. W. H. Rule, a resident British missionary and educator, wrote in 1844 that “there is an unchristian prejudice among many persons against all that is Spanish, of which the natives themselves unhappy partake” (Rule 1844: 367). Richard Thomsett, a British naval officer, referred to two classes of Gibraltarian, the first “a polite English speaking person … the shop-keeper of Gibraltar” and the second “who knows but a few words in broken English … yet he loves to be thought English” (Thomsett 1890/1999: 74).

At the start of the twentieth century, only the social elite of the colony were bilingual in Llanito and English (Kellerman 2001; Weston 2011). The marriage patterns that had prevailed throughout the nineteenth century continued into the early twentieth, reinforcing the use of Llanito among Gibraltar’s residents. In 1944, Professor Hayek of the London School of Economics reported that “a very high proportion of Gibraltarian men marry Spanish women … who usually speak no English at all” (quoted in Benady 2000: 135). Stockey (2019: 166, citing John Pau) explains this trend with reference to the relative prosperity of Gibraltar, which attracted “girls over the other side of the border who wanted to improve their lot”. It is unclear, however, whether their new life on the Rock lived up to expectations. As monolingual citizens of a war-torn country traditionally inimical to British Gibraltar, they were disadvantaged in multiple ways in a territory where the garrison elite were typically male, English-speaking and British. The intersectional disadvantages experienced by Spanish women may help to explain why, even today, Gibraltarians disavow the Spanish ancestry of their foremothers, who “have been erased from official and person(al) historical consciousness” (Canessa 2019: 20–21). What is also clear, however, is that life on the Rock during the twentieth century proved to be a transformative experience, for them and particularly their children and grandchildren.

By the end of the century, Kellerman (2001: 92) notes that “through a striking process of partial language shift … Gibraltar’s predominantly monolingual Spanish-speaking classes became bilingual”. This shift can be attributed to four consequential events, which collectively convinced Gibraltarians that Britain was its future, and the language they needed for that future was English. These were the resumption of the old antagonisms of Spain following the Francoist victory in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939); the evacuation of Gibraltar’s women and children to English-speaking territories during World War Two (1940); the post-war revitalization of the housing stock and education system, emphasizing knowledge of English (Archer and Traverso 2004); and Franco’s sealing of the border from 1969 to 1985. The first of these events led directly to an influx of between 5,000–10,000 Spanish refugees, depending on sources.[23] While only a minority of these monolingual Spanish speakers were permitted to remain, the Spanish regime became an object of hatred for Gibraltarians. During World War Two, women and children were evacuated to London, Madeira and Jamaica, where their knowledge of English dramatically improved. A civil servant visiting an English school of Gibraltarians noted “Two years ago they knew no word of English; now they prattle bilingually” (Finlayson 1990: 94). These linguistic gains were further consolidated in two ways when Gibraltarians returned to the Rock. First, Gibraltarians adopted an anglophone education system modelled on Britain’s. Second, land reclamation allowed for new housing blocks to be built, which dispersed the multigenerational dwellings and patios that otherwise served to maintain the use of Spanish (Weston 2013: 260). The conditions for language shift towards English were then speeded by the border closure, when “Gibraltarians’ only link with the outside world being travel by air to London … inevitably strengthened their ties with Britain in every way” (Garcia 1994: 157). Weston (2013) demonstrates that the border closure was a sociolinguistic watershed, when many Gibraltarians started to speak to their children in English at home.

Events that brought about a partial language shift towards Llanito-English bilingualism in the twentieth century (2001) are also responsible for a shift towards monolingual English in the twenty-first. Weston (2011, 2015) and Suárez-Gomez (2020) capture this shift through the lens of Schneider’s (2007) Dynamic Model of Postcolonial English, and Buschfeld and Kautzsch’s (2017) Extra- and Intra-territorial Forces Model, respectively. While Kellerman points to the focusing of a local Gibraltarian accent, Enriles (1992) demonstrates how this local variety is also losing Spanish-contact features and moving towards a Southern Standard British English norm. This shift is apparent not just to linguists, but to Gibraltarians themselves, many of whom regret the loss of the cultural and linguistic “privilege of living and being bilingual” (Weston 2013: 6). This process of language shift is not yet one of wholesale replacement of Llanito by monolingual English. Rather codeswitching, long practised on the Rock since the period of British sovereignty, now demonstrates ratios increasingly dominated by English (Rodríguez García 2024; Weston 2013: 6).

As is apparent from Tables 3 and 4, irrespective of whether the streetname generics are from English or Llanito, the specifics are from a range of languages, as has been the case since 1704. Multilingualism and language mixing has long been Gibraltar’s norm. What is new is the lack of replenishment of Spanish from the Campo de Gibraltar into the home. Buchstaller et al. (2023: 6) observe that “the citytext, and especially the memorialisation therein, is interpreted as the selective memory of a society”, and “the sedimented citytext is a palimpsest of, sometimes antithetical, versions of history, none of which are ideologically neutral” (2023: 12). This lack of replenishment of Spanish from the Campo de Gibraltar means that the memory of Gibraltar’s streetscape is becoming even more selective. Aware of this impending break in the transmission of Llanito, the Gibraltar Ministry for Traffic, Transport and Technical Services has recently positioned Gibraltar Heritage plaques adjacent to eleven streetsigns, explaining “local colloquial heritage regarding Gibraltar’s old street names”, not for the benefit of Gibraltarians, however, but tourists.[24] This is a representation of space acknowledgement of the social value of the Llanito variants (although only some of those plaques contain Llanito). As observed in Section 1, bilingual streetsigns proclaim identity, and Llanito variants convey and transmit identity just as much as the English variants. Nevertheless Smith and Akagawa (2009: 4) make the point that it is often theatrical examples of intangible cultural heritage that fit Western preconceptions of what heritage is. By contrast, something as mundane as a Llanito streetname passes unnoticed.

6 Conclusions

The analysis of streetnames and surnames presented here is a demonstration of lexical sociolinguistics. The argument is based on a survey of the historic onomasiological set, and on applying the concept of communities of spatial practice, which merges the community of practice (the civilian fort-servicers) and their spatial practice mobility (fort-servicing as a motivation for migration around the Western Mediterranean forts). The economic attraction of providing services to the garrison caused people to move to Gibraltar, which was a node in a fort-servicing network, with the concomitant effect of lexemes passing from surnames to streetnames over generations. We have examined the social value of the onomasiological set of streetnames and what would be lost if the Llanito variants were abandoned altogether. We have drawn attention to the unique properties of Gibraltar’s streetname assemblage: (a) the inclusion of the names of eighteenth-century Western Mediterranean fort-servicing personnel, (b) the oral preservation until recent times of Llanito variants, some with proximal affect not encoded in English variants, (c) the unusual referential disjunction between English and Llanito variants, and (d) the preservation of a density of eighteenth-century fort-vocabulary of ramps and fronts, parades and ranges, walls, barracks, bomb-house and bastions. Gibraltar’s half-written, half-oral personal-name streetname assemblage records a cohesive core of eighteenth-century families whose settlement seeded the stability of Gibraltar’s civilian population, whose descendants continue to bear their names in Gibraltar today. Although the legitimacy of the Gibraltarian identity has been challenged by successive Spanish governments, this unbroken lineage is testament to the generational spatial practice of civilian residents. We asked whether this has any relevance for present-day Gibraltarians. We suggest that it does, being relevant to personal ancestry, identity and belonging. We have questioned what would be lost if the Llanito variants were forgotten, and concluded that their loss equates to a loss of cultural heritage.[25] Gender is implicated, heritage plaques notwithstanding, as Llanito has largely been maintained and replenished by the female line due to an economic imbalance between’ Gibraltarian men and Spanish women. Its loss can be equated with a termination of the historic female voice, the result of a “profound ambivalence towards Spanish, the language of mothers (and grandmothers)” (Canessa 2019: 8).

Appendix 1: Gibraltarian bilingual streetname equivalents

Streetnames sources: Patterson (1884), Bandury (1890) copied from Benady (1996: 57) and López Zaragoza (1899) (see footnote 17 ), Ellicott (n.d., possibly 1970s), Road-Book (1939), The History of Gibraltar’s Street Names leaflet, Galliano (2022), Chipulina’s blog. For more bilingual equivalents as used in the twentieth century see Vallejo (n.d.). Richard Garcia, Joshua Marrache and Mario Nunez have provided expert opinion on GNA holdings.

| Abecasis’ Passage | Callejon de la Pasciega (Gilbard), Callejon de la Paciega (López Zaragoza) |

| Arengo’s (Palace) Lane | Callejon del Palacio (Patterson), Callejon de Chiappi (Gilbard, López Zaragoza), Galliano reports that Chiappi is the equivalent of Police Barracks Lane. GNA, Special File No. 53 of 1913 explains “Present name: Arengo’s Lane. Proposed name: The lane round Arengo’s palace to be called Arengo’s Lane - Callejon de Chiappi to be called Police Barracks Lane. Ratified 5 February 1914 “Arengo’s Lane To be called “Police Bks Lane” |

| Bell Lane | “A house in a Back street formerly called La Calle del Governador being the Corner of a Lane now called Bell Lane and formerly the Callejuella de Fonseca” (1749, GNA, Crown Lands Series A, General Bland’s Court of Enquiry, fo 171). Calle del Governador was the Spanish-period name for Engineer Lane (Galliano). Callejon del Lazareto (Patterson), but Galliano says there is no evidence for the ‘Lazareto’ variant |

| Benzimra’s Alley/Lane | Callejon del Moro (López Zaragoza) |

| Bomb House Lane | Callejon de la Bomba (Patterson); La Calle que va a la Plazuela de Juan Serrano (Benady, Galliano) |

| Boschetti’s Ramp/Steps | Escalera del Espino (Patterson), Callejon del Tio Pepe (Gilbard, López Zaragoza) |

| Cannon Lane | Detras de la Iglesia (Gilbard); Callejon de la Iglesia (Vallejo) |

| Carrera’s Passage | Patio de Carreras (Road Book) |

| Casemates Square | La Esplanada (Gilbard) |

| Castle Ramp | Calle del Castillo (Gilbard); GNA, Special File No. 53 of 1913 says Castle Row and Castle Ramp are both to be named Castle Ramp |

| Castle Street | Calle Comedias (Gilbard); top end Caño Real (Vallejo). Galliano says known earlier as Calle de la Cuesta and Calle Alta, citing Barrantes Maldonado (1566). However Chipulina suggests these were variants for Castle Road |

| Charles V Steps/Ramp | Escaleras de Carlos V (López Zaragoza) |

| Church Street | Calle de la Iglesia (Gilbard) |

| City Mill Lane | Calle de las Siete Revueltas (Gilbard), Callejon de Cureto Mio (Patterson), upper part La Calle Angosta de Miguel de Ribera (Galliano, citing López de Ayala 1782: 254); southern part Whirligig Lane (Galliano, citing James 1771: 250). Chipulina identifies Patio Currito el Meo as 56, City Mill Lane. The eponymous corn mill was on the corner of City Mill Lane and Governor’s Street: Gibraltar Chronicle, 12 September 1839 (Richard Garcia). Weston and Wright (2025) discuss the prevalence of streets named Siete Revueltas elsewhere in the Iberian Peninsula |

| Civil Hospital Lane | Callejon de San Juan de Dios (Patterson) |

| Civil Hospital Ramp | Cuesta del Hospital (Gilbard) |

| Cloister Ramp | Los Baños de Scotto (Gilbard), Callejon del Antiguo Baño (Patterson) |

| College Lane (earlier Jenkin’s Lane) | Callejon de Risso (Gilbard), de Rizo (Patterson), Callejon de Amar (Vallejo), Callejon del Europa (Vallejo) |

| Commercial Square/John Mackintosh Square | La Plaza Mayor (Galliano, citing Hernández del Portillo 1622 [1994]: 89); The Parade (James), Plazuela del Martillo (Gilbard), La Piazza (Chipulina) |

| Convent Place | Placalito del Convent (Galliano) |

| Cooperage Lane | Callejon de la Garloza (Patterson, with meaning unknown); Calle del Caño de Machín (Galliano, citing Hernández del Portillo 1622 [1994]: 157); Callejon de la Plaza/Mercado (Vallejo) |

| Cornwall’s Parade (earlier Green Market) | Plaza de la Verdura (Galliano) |

| Crutchett’s, or Portuguese Town | La Calera (Gilbard) |

| Cumberland Steps | La Escalerita de Pili (Chipulina)/Piri (Road Book) (/l/is pronounced [r] between vowels in Llanito) |

| Danino’s Place | Patio de los Caballeros (Patterson); equivalent name for Palace Gully (Mario Nunez) |

| Devil’s Gap (Gilbard), Devil’s Gap Steps (Bandury), Lopez’s Ramp and Devil’s Gap Road (Chipulina), Devil’s Gap Road (Road Book) | Escalera del Monte (Gilbard); 1915, GNA, List of all Properties in Gibraltar in Alphabetical Order of New Street Names: Sanitary Commissioner’s Office: Devil’s Gap Road “also forms part of No. 2 Lopez’s Ramp”; Lime Kiln Road “also forms part of Nos. 1 & 3 Lopez’s Ramp”; Devil’s Gap Road “also forms part of No. 4 Lime Kiln Road” |

| Engineer Lane | Calle del Gobernador (Galliano, Spanish period); Calle Ingenieros (Gilbard), Calle de los Cordoneros (Patterson) |

| Fish Parade | Callejon de la Plaza (Galliano) |

| Flat Bastion Road | Cuesta de mistebon/Mr Bourne (Gilbard, Bandury, Galliano); earlier Senda del Moro, Senda del Pastor (Patterson) |

| Fountain Ramp | Callejon de la Fuente (Gilbard) |

| Fraser’s Ramp, named after Widow Fraser (Richard Garcia) | Escalera de Benoliel (Gilbard). Fraser’s Ramp is the alley that runs East-West and Benoliel’s Passage is the alley in the middle leading northwards, marked in GNA, Land Properties Book (Joshua Marrache) |

| George’s Lane | Calle Vicario el Viejo (Gilbard), Calle del Vicario (Patterson), el Vicario Viejo (Benady) |

| Giro’s Passage | “A place called the Callejuella de Zorita” (1749, GNA, Crown Lands Series A, General Bland’s Court of Enquiry, fo 26, but with no indication where situated); Callejuela de Zurita (Ballesta Gómez 2008) |

| Governor’s Lane | Callejon de San Francisco (Patterson) |

| Governor’s Parade (earlier French Parade, also Gunner’s Parade, Galliano) | Plaza de Artilleros (Gilbard, Bandury) del Artilleria (Patterson), Plazoleta de la Reina (Vallejo) |

| Governor’s Street | Calle Cordoneros (Gilbard, Bandury) |

| Gowland’s Ramp | Callejon del Hospicio (Gilbard) |

| Hargrave’s Parade | Plazuela de los Artificios (Gilbard), Artificers (Bandury), de los Ingenieros (Patterson) |

| Horse Barrack Lane | Patio del Catalano (Patterson) |

| Hospital Ramp | Escalera del Ospicio (Patterson, but Galliano says Escalera del Ospicio was Gowland’s Ramp); Cuesta del Hospital (Bandury) |

| Hospital Steps (previously Rogers Ramp) | Los Espinillos |

| Irish Town | “A house in Irish Town formarly called Calle de Meradd fronting Officers Barr.s”; “the street called Calle St Anna”; 1749, GNA, General Bland’s Court of Enquiry, fo 134 and fo 40); Calle de Santa Ana (Patterson) |

| King Street | Callejon de la Paloma (Patterson) |

| King’s Yard Lane | Callejon de la Paloma (Gilbard, Bandury), Callejon del Horno del Rey (Patterson) |

| Library Gardens | Huerta Riera (Gilbard) |

| Library Ramp | Callejon de Balali (Gilbard); Cuesta del Ball Alley (Bandury) |

| Lime Kiln Road | Callejon de Dolores Corbe (Gilbard) |

| Lime Kiln Gully | Callejon de Segui (Gilbard) |

| Line Wall Road (earlier Lover’s Lane) | Las Murallas (Gilbard) |

| Lynch’s Lane | Jardin de Glynn (Bandury), Calle que sube al castillo (Chipulina) |

| Main Street (at different points Waterport Street, Church Street and Southport Street) | Calle Real (Patterson) |

| Market Lane | Callejon de la Carniceria (Gilbard, Bandury), Callejon del Cantarero (Patterson) |

| Market Street | Callejon de la Policia |

| New Passage | Calle Peligro (Bandury) see Serruya’s Lane |

| Paradise Ramp | Escalera de Cardona (Gilbard) |

| Parliament Lane (earlier Callwell’s Lane, Galliano) | Callejon de la Fonda de los Masones (Gilbard) |

| Prince Edward’s Ramp | Cuesta de Carlos Maria (Gilbard) |

| Prince Edward’s Road | Cuesta de Sandunga (Gilbard, Bandury); Camino del Principe (Patterson); Cuesta de la Cebada (Road Book) |

| The Road to the Lines | Callejon Sin Sol (Vallejo, Galliano) |

| Roger’s Road | Calle de San Jose (Chipulina) |

| Secretary’s Lane | Callejon del Alcalde (Patterson); Callejon de la Secretaria (Galliano) |

| Serfaty’s Passage | Callejon de Bobadilla (Gilbard) |

| Serruya’s Ramp | Escalera de Maqui (Gilbard) |

| Serruya’s Lane | Calle Peligro (Gilbard, López Zaragoza) |

| Southport Street | Calle Puerta Nueva (López Zaragoza) |

| Sunnyside Steps | La Escalera del Caracol (Chipulina) |

| Town Range (earlier Prince’s Street, New Barracks Street, Queen Street, Galliano) | Calle Cuarteles (Gilbard) |

| Turnbull’s Lane | Calle del Garrapo (1798–1802, GNA, Civil Court Minute Book 16, p. 245, identified in Land Property Book 1–94, p. 272, Map of Town District No. 3); Detras de los Cuartos (Gilbard) |

| Tuckey’s Lane | Callejon del Jarro (Gilbard) |

| Victualling Office Lane | Callejon del Perejil (Gilbard) |

| Willis’ Road | La Buena Vista (Gilbard) |

Appendix 2: Personal names in Gibraltar streetnames matched to residents 1705–1834

Names are located in Gibraltar National Archives census data (https://www.nationalarchives.gi/Inhabitants.aspx); before the nineteenth century addresses were not routinely recorded. The family-members listed here are not necessarily the street-honorands as our purpose is to show that the families bearing the name in question were resident in Gibraltar 1705–1834, by which date streetnames stabilised as streets had largely been built.

| First date of streetname in censuses | Early Gibraltarians bearing the name | Date of source documentation of bearer | Origins of bearers | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abecasis Passage 1868 | Meshod Abecasis, born Tetuan, age 40, resident 24 years 1777; Mair Abecasis, born Tangier, age 56, resident 43 years 1777; Jewish porters of the garrison | 1774 | Tetuan, Tangier | Honorand is Haim Abecasis (Ellicott n.d.: 10). Arabic ‘man of tales’ (Beider 2017: 284) |

| Aloof’s Ramp 1814, Aloof’s Yard 1814 | Abram Aluff, Jewish, age 40, resident 30 years | 1777 | Tetuan | |

| Ansaldo’s Passage 1868, Ansaldo’s Ramp 1878 | John Baptist Ansaldo, landowner since 1710;a Baptista Ansaldo, landowner since 1718 | 1705–1729 | Genoa | Honorand is John Ansaldo (Ellicott n.d.: 10) |

| Arengo’s Lane 1834, Arengo’s Ramp 1868, Arengo’s Steps 1868, Arengo’s Yard 1871, Arengo’s Passage 1878 | Bartholomew Arengo, landlord in Main Street | 1756 | Genoa | Honorand is Francisco Arengo (Ellicott n.d.: 10) |

| Baca’s Passage 1891 | Giuseppe Baca, Labourer | 1822 | Genoa | |

| Baker’s Passage 1868 | William Baker, Henry Baker | 1805 | ||

| Banasco’s Passage 1891 | Domingo Banasco, age 60, resident 48 years | 1777 | Mayorca | |

| Benoliel’s Passage 1881, Escalera de Benoliel 1884 (Patterson) | Solomon Benoliel, Jew, born Tetuan, age 38, resident 23 years | 1777 | Tetuan | Hebrew ‘son of sick one’ (Beider 2017: 548) |

| Benzimra’s Alley 1871, Benzimra’s Lane 1878, Benzimra’s Passage 1878, Pasaje de Benzimra 1899 (López Zaragoza), Callejon Benzimra 1899 (López Zaragoza) | Moses Benzimra, Jewish, huckster; Solomon Benzimra, Hebrew, born Menorca, merchant, age 48, resident 35 years, 1817 | 1784 | Hebrew ‘son of Zemerro’ (Beider 2017: 287). | |

| Callejon de Bobadilla 1884 (Patterson) | Joaquin Bobadilla, physician, age 45, resident 10 years | 1817 | Spain | dead by 1817 |

| Booth’s Passage 1871 | Thomas Booth, landowner since 1717 | 1728–29 | Britain | |

| Boshitti Ramp 1814, Boschetti’s Steps 1940 | Giovanni Maria Boshetti, mason, age 32, born Graglio, in Gibraltar 1784b | 1791 | Lombardy | Honorand is John M. Boschetti, born Italy, architect, age 58, resident 34 years, 1817 (i.e. the same individual) (Ellicott n.d.: 10). |

| Bracebridge Gardens 1834 | Edward Bracebridge, age 50, painter, resident 26 years | 1834 | Britain | |

| Bruce’s Gully 1834 | John Bruce, age 48, shoemaker | 1777 | Britain | dead by 1777 |

| Caballero’s Yard 1868 | Mathias Caballero, age 20 | 1791 | Spain | |

| Escalera de Cardona 1884 (Patterson) | Antonia Cardona | 1740s | Arrabal de San Felipe, Menorca | Crespo i Sala (2015: 388) |

| Cuesta de Carlos Maria 1884 (Patterson) | Anto’ Maria | 1736 | ||

| Carreras Passage 1868 | Antonio Carreras, landowner since 1717; Sebastian Carreras, born Menorca, patron of ferry boat, age 42, resident 24 years, 1817 | 1717 | Spain | |

| Callejon de Chiappi 1884 (Patterson) | Carlos Chiappe, age 36, resident 16 years | 1777 | Genoa | |

| Chicardo’s Passage 1868, Chicardo’s Steps 1878, Chicardo’s Lane 1891 | Law Sicardo 1736; Domingo Chicardo, born Genoa, age 38, patron, resident 22 years, 1777 | 1736 | Genoa | |

| Cooper’s Lane 1814 | William Cooper, merchant | 1816 | ||

| Cornwall’s Lane 1868, Cornwall’s Parade 1868 | Vice Admiral Charles Cornwall | 1717 | Britain | Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet 1717–1718 |

| Crutchett’s Ramp 1871, Crutchett’s Steps 1871 | John Crutchett, owner of a limekiln in early 18th cc | 1751 | Benady (1996: 6) | |

| Cumberland Place 1868, Cumberland Ramp 1868, Cumberland Road 1868, Cumberland Hill 1871, Cumberland Steps 1878 | Probable honorand Duke of Cumberland, who visited Gibraltar 1768d | |||

| Dalmaya’s Ramp 1878 | Jose Da’maia, age 24; Jose Peres Da Maya, born Portugal, trader, age 26, resident 12 years, 1817 | 1791 | Portugal | |

| Danino’s Ramp 1878, Danino’s Place 1884 (Patterson) | Augustin Danino bought land from Governor Elliott in 1706; Francisco Danino sold land in 1726e | 1705–1729 | Genoa | |

| Fraser’s Ramp 1834 | Mr Fraser, landlord | 1756 | Britain | |

| George’s Lane 1756, George’s Street 1871 | George, late landlord in Southport Street | 1756 | ||

| Giro’s Entrance 1814, Giro’s Passage 1871, Pasaje de Giro (López Zaragoza 1899) | John Giro, merchant, age 55, resident 35 years | 1817 | Menorca | |

| Gusto’s Ramp 1868, Gusto’s Road 1868 | John Gusto, wine house, age 42, resident 34 years | 1816 | Germany | |

| Jardin de Glynn 1890 (Bandury), Glynn’s Lane 1871 | John Glynn, merchant, age 19 | 1791 | Ireland | Honorand is Charles Glynn, early 19th c. merchant (Chipulina n.d.) |

| Gowland’s Ramp 1871 | John Gowland, mason, age 32, | 1791 | Britain | |

| Hargrave’s Lane 1871, Hargrave’s Parade 1871 | Colonel Hargrave, landowner since 1718 | 1705–1729 | Britain | Commanding Officer 1728–29 |

| Johnson’s Passage 1868 | Majr. Robert Johnston, landowner since 1726 | 1705–1729 | Britain | Honorand is probably Robert Johnston, merchant (Chipulina n.d.) |

| Justo Row 1868 | Giacome Justo, keeper of a hotel, resident 6 years | 1817 | Genoa | |

| Lewis’s Lane 1756 | Lewis Butler; Lewis Garcia 1749, John Lewis 1809 | 1756 | Landlord Billet Lists 1756 ID 64, 65, 66, 67, 73 | |

| Lopez’s Ramp 1868 | Joseph Lopez, born Portugal, master mason, resident 18 years; Manuel Lopez, Stone cutter, age 26, resident 4 years | 1777 | Portugal | |