Abstract

This paper reports the findings of a corpus-based study of prescriptive and normative discourses in Late Modern English review periodicals, using a purpose-built diachronic corpus of review articles published during the period 1750–1899. Drawing on established protocols from Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies and systematic comparison of 15 sub-corpora, it identifies decades during which prescriptive discourses were most frequent. This distributional pattern provides empirical evidence of an ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ in periodical reviewing, during which prescriptive discourses reached their zenith. Whilst the label ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ has been applied to a number of periods of English in recent decades, the findings reported here show clearly that the eighteenth century was the locus of prescriptive activity in the review periodical genre. The innovative application of corpus-based discourse-analytic methodologies for the identification of normative trends reported in this paper also has potential implications for studying prescriptivism as a sociohistorical linguistic phenomenon in other diachronic contexts.

1 Introduction

The Late Modern (LMod) period, defined in this paper as the period of English language history between 1700 and 1900, is associated in the modern linguistic consciousness with the pervasive stereotype of normativity. It is often assumed that because normative practices of codification proliferated at an unprecedented rate during the eighteenth century, the LMod period (or discrete sub-periods within it) can be labelled as English’s ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ (cf., inter alia, Anderwald 2014; Baugh et al. 2012; Leonard 1929; McIntosh 1998; Milroy and Milroy [1992] 2012). Hence, as Anderwald has pointed out, it is “taken for granted that … prescriptivism was all-pervasive” (Anderwald 2019: 89) as a sociolinguistic phenomenon during this period.

Despite this stereotype, the label ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ has, in fact, been applied variously to several different periods of English, depending on the model of standardization applied (cf. Haugen 1997; Milroy and Milroy 2012), and often also on the basis of attempts to chart empirically changes hypothesized to have been prompted by prescriptivism. Thus, in The Subjunctive in the Age of Prescriptivism, Auer (2009) identifies the eighteenth century as the ‘Age of Prescriptivism’, whereas Anderwald (2016) uses the phrase in relation to the nineteenth century. Shifting the focus beyond usual periodizations of LMod English, Tieken-Boon van Ostade has argued that the eighteenth century should “more properly be designated the Age of Codification, as it is the codification of the language that characterises the period, not the effects of prescriptivism, or even prescription” (2019: 8; emphasis original). For Tieken-Boon van Ostade, prescriptivism “represents yet a further stage in the process, during which there is an excessive focus on the question of what is correct usage” (2019: 8), and on this basis, she concludes that “the Age of Prescriptivism is now” (2019: 9).

Differences in defining the Age of Prescriptivism in English, and their relevance to the research reported here, will be explored in Section 2.3. The purpose of this paper is not, however, to make generalizable claims about an Age of Prescriptivism in English. Instead, building on earlier research which used Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies (CADS) to identify prescriptive discourses (Malory 2024), the work reported here explores whether CADS also makes possible the pinpointing of an Age of Prescriptivism in the literary review periodical genre, in a way that may ultimately allow similar research to be conducted at a more general level. The review periodical genre is ideally suited to this purpose because, as will be outlined in Section 2.2, previous scholarship on review periodicals in LMod English has implicated this genre as a significant source of prescriptivism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (McIntosh 1998; Percy 2009, 2010). The purpose-built review periodical corpus introduced in Section 3 therefore provides a convenient pilot dataset for testing a methodological approach which uses corpus-based discourse analysis to explore prescriptive and normative trends diachronically. This approach shows promise; the findings reported in Section 4 indicate that prescriptivism is an ephemeral feature of the review periodical genre, and that a discrete ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ can indeed be identified. These findings are of significance for our understanding of the sociolinguistic role played by these publications in Late Modern Britain. They also showcase the potential for a methodology which uses discursive identifiers of prescriptivism to allow for diachronic charting of prescriptivism and normativity in other contexts.

In Section 2, relevant literature will be used to contextualise the findings of the study reported here. In Section 2.1, foundational definitions of concepts such as ‘prescriptivism’ and ‘normativity’ will be provided. In Section 2.2, previous research focusing on the review periodical genre as a prescriptive force in eighteenth-century culture will be outlined. In Section 2.3, previous scholarship identifying an ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ in English will be explored in detail. Section 3 will then outline the corpora used in this study, and the details of the methodological approach employed, before Section 4 reports the findings of the study and Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 Literature review

2.1 Defining prescriptivism and normativity

There is some fluidity around definitions of prescriptivism, normativity, and language planning. This section will therefore outline precisely how these concepts are understood for the purposes of this paper, and how they will be used during the analysis reported in Section 4.

For the purposes of this paper, prescriptivism is considered to be the attempted enforcement or imposition of language rules, as distinct from the outlining of how something could be done, which language planning entails (Calvet 2017). Both these concepts are considered distinct from descriptivism; the neutral, or objective, description of linguistic usage. Prescriptivism is also sometimes considered distinct from normativity, though these words are also often used interchangeably. This paper will follow Straaijer’s (2009) definition of normativity as “a more general ideology”, with “the terms prescriptive and descriptive refer[ring] to a more specific practice expressing that ideology” (80). This distinction will also be used throughout this paper, but the phrase ‘linguistic criticism’ will be used as an umbrella term to encapsulate both normativity and prescriptivism.

2.2 Review periodicals: a prescriptive genre?

For decades, it has been noted that the popular review periodicals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries contained linguistic criticism. As early as 1998, McIntosh concluded that the Monthly and Critical reviews “made a speciality of savaging what [they] considered bad English” (184). Carol Percy, who has written extensively on reviewer prescriptivism, has likewise concluded that eighteenth-century reviewers “regularly and publicly subjected writers to imperfectly-codified grammatical standards” (2009: 138). In order to reach this conclusion, Percy spearheaded the construction of a database of linguistic criticism in eighteenth-century periodical reviews. This database contains over 10,000 records for instances of linguistic critique and is coded according to themes such as “ungrammatical”, “incorrect”, and “inaccurate”, as well as the genres of text being reviewed (Percy 2000a). Percy has used this resource to research many specific aspects of eighteenth-century review normativity, for example stereotypes about the language of women (2000b) and prescriptions for “manly” English (2008), as well as to draw general conclusions about the role of periodical reviewing in eighteenth-century linguistic culture (2009, 2010).

Percy’s database and research using it have advanced understanding of the mechanisms of eighteenth-century review periodical prescriptivism hugely, but there remain gaps in our knowledge of the genre and how it functioned as a normative force in Late Modern English. Advances in corpus methodologies in recent decades provide an opportunity for these gaps to be addressed. The first gap relates to coverage; Percy’s database contains linguistic criticism from only the eighteenth-century, and only the two most successful periodicals of the mid-century, the Critical Review and the Monthly Review. Given the highly labour-intensive nature of compiling such a database, this makes sense. These seem to be the periodicals most associated with review prescriptivism, and were much more widely-circulated than any rival publications in the mid-eighteenth century (Donoghue 1996). However, the drawback of this focus is that it is not possible to use such a database to draw conclusions about the role these review periodicals played within the wider periodical marketplace, nor the Late Modern period more broadly. For this, a corpus of randomly-sampled periodical articles from the range of available reviews is needed. This corpus also needs to comprise not only eighteenth-century periodical reviews, but also those published during the nineteenth century, if review prescriptivism is to be demonstrated empirically to have been primarily an eighteenth-century phenomenon.

The Corpus of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century English Reviews (CENCER), which will be introduced in Section 3, meets these criteria. The findings it has facilitated therefore allow such studies as the one reported here to build on the work of Percy and others, in utilising cutting-edge corpus methodologies to advance understanding of the mechanisms of review prescriptivism.

2.3 An Age of Prescriptivism?

Uncertainty about what defines the ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ in English appears to result from two data gaps in the field. Firstly, there is the data gap to which Tieken-Boon van Ostade refers obliquely, above. In arguing that the eighteenth century should “more properly be designated the Age of Codification, as it is the codification of the language that characterises the period, not the effects of prescriptivism, or even prescription” (2019: 8; emphasis original), Tieken-Boon van Ostade highlights the importance of gauging prescriptive impact, if we are truly to understand the workings of prescriptive phenomena. The quantification of prescriptive impact has, however, proven a significant challenge, both in English (cf. Anderwald 2012, 2014, 2019; Auer and González-Díaz 2005; Malory 2022; Yáñez-Bouza 2008) and in other languages with prescriptive traditions, such as Dutch (Krogull 2018) and French (Poplack and Dion 2009). For the purposes of this paper, however, a more pertinent data gap is that relating to the scarcity of empirical evidence not, to borrow Tieken-Boon van Ostade’s words once again, for the “effects of prescriptivism” (2019: 8; emphasis added), but for codification itself.

Much research at the interface of codification and prescription has been conducted, but there is also much that is still unclear. It has been shown, for example, that many of the figures most associated with codification in English, such as Lowth and Priestley, are often descriptive in their approach to language. Addressing the “widespread view of Lowth as an icon of prescriptivism” in a monograph on his famous grammar book, Tieken-Boon van Ostade for instance argues that “[a]ctual analysis of his so-called strictures demonstrates a descriptive rather than the alleged prescriptive approach” (2011: 1). Straaijer’s (2009) findings, in testing a quantitative approach to identifying prescriptive and descriptive passages in early editions of the grammars of Lowth and Priestley, are similar. Straijjer reports that deontic and epistemic modal auxiliaries “appear to be adequate indicators of prescriptive and descriptive language” (2009: 58) in these texts. On the other hand, Vorlat’s (1996) analysis of Murray’s grammar finds that his “overwhelming use of deontic modals in the wording of [language] rules”, means that “the prescriptive character” of his grammar is inarguable (168).

Corpus research has therefore provided evidence of both prescriptivism and descriptivism in some of the most famous codifying texts of the eighteenth century. However, so intense has been the focus on prescriptivism as a hallmark of codification in LMod English that no attempt seems to have been made to conduct a more systematic, large-scale investigation of changing trends in codification. Arguably the most systematic treatment of eighteenth-century codification is Sundby et al.’s (1991) Dictionary of Normative English Grammar, 1700–1800. Although an invaluable resource for studying processes of standardization in English, this volume exemplifies the potential for confirmation bias in the study of Late Modern codification. With ‘normative’ in its very title, Sundby et al.’s (1991) Dictionary was never going to comprehensively challenge the notion that eighteenth-century grammarians were mostly prescriptive in their codification of English. Moreover, its narrow focus on the eighteenth century, though understandable given the vast scope of the undertaking, makes it impossible to compare practices of codification across different centuries and periods of English. This contributes to the gap in knowledge of how codification practices in English have changed over centuries and periodization thresholds.

Another reason for there to be a gap in our understanding of how codification practices compare between the Late Modern period and Present-Day English is the methodological challenge which researching practices of prescriptivism poses. Percy (e.g. 2008, 2009, 2010) and others (e.g. Basker 1988; Donoghue 1996; McIntosh 1998) who have identified prescriptive or normative discourses in review periodicals have employed primarily qualitative methods, relying on manual explorations and close analysis. These approaches use relatively small datasets, for reasons of manageability. Few attempts seem to have been made to use corpus methodologies to find an automated means of retrieving instances of prescriptivism. Those studies referenced above, Vorlat’s (1996) and Straaijer’s (2009), are amongst the few attempting to do this, and both focus on synchronic usage, rather than diachronic change.

As outlined above, Vorlat (1996) uses deontic modal auxiliary verbs as indicators of prescriptivism in Murray’s grammar, contending that, given “Murray’s overwhelming use of deontic modals in the wording of the rules”, “there is no denying the prescriptive character” of his grammar (168). In particular, Vorlat concludes the verb forms ought to, must, and should to be particularly indicative of prescriptivism. Straaijer (2009) considers the frequency of deontic and epistemic modal auxiliaries in early editions of both Lowth and Priestley’s grammars, concluding that these verbs “appear to be adequate indicators of prescriptive and descriptive language” (2009: 58). These approaches are strongly hypothesis-driven, relying on indicators of prescriptivism that must be pre-defined by the researcher, rather than being guided by the data. They also do not seek to explore diachronic trends in prescriptivism.

The present study, which uses protocols from Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies (Marchi 2010) to identify indicators of prescriptivism, and then tracks their usage over a 150-year period, is therefore a departure from previous research in this field. In Section 3, the corpora and methods of analysis used in this research will be outlined, before its findings are reported in Section 4.

3 Corpora and methods of analysis

3.1 Corpora

The study reported here used a purpose-built corpus of review articles from the Late Modern period of English, known as the Corpus of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century English Reviews (CENCER). CENCER is a 1.2-million-word corpus of review periodical articles published in Britain between 1750 and 1899. It comprises 15 sub-corpora, each a decade long and containing approximately 80,000 words. Table A1 in Appendix A provides a breakdown of the number of text files and words in each of these sub-corpora.

CENCER was constructed using review periodicals from ProQuest’s ‘British Periodicals’ database. At the time of construction, this database contained full print runs of 472 different historical British periodicals published between 1681 and 1939. Only regular, national publications exclusively providing content intended to evaluate the general contemporaneous output of publishing houses were considered eligible for inclusion in CENCER. 46 periodicals met these criteria. From these, articles were sampled in the construction of the CENCER corpus. The corpus was compiled one decade at a time, using a random number generator in the software environment R (cf. Desagulier 2017).

The files downloaded from the ‘British Periodicals’ database for the compilation of the CENCER corpus were graphics rather than text files. For the corpus to be compiled, these were converted into a machine-readable format using OCR software, and manually post-edited to achieve a clean, machine-readable corpus, which could be run through WordSmith (Scott 2020).

The reference corpus used to generate keyword lists for each of the CENCER sub-corpora was the Corpus of Late Modern English Texts 3.0 (De Smet et al. n.d.). CLMET is a large multi-genre corpus of Late Modern English, which is comprised of five major genres; narrative fiction, non-fiction, drama, letters, and treatises, in addition to some further unclassified texts. It contains approximately 34 million words from between 1710 and 1920, and is sub-divided into three 70-year sub-periods.

3.2 Methods of analysis

As has already been established, the findings reported in Section 4 of this paper rely upon a methodological approach which uses protocols from Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies (CADS) to identify and track indicators of prescriptivism and normativity. CADS research combines corpus approaches and discourse studies, often using what Marchi (2010) refers to as a “funnelling” approach, whereby the research progresses from macro- to micro-level analysis, using the following stages:

Using word lists and keyword lists to identify key semantic domains

Using collocation to identify patterns of behaviour for keywords

Using concordance lists to explore dominant patterns in context

In line with this, the first stage in the analysis reported in Section 4 was to attain a keyword list for each CENCER sub-corpus, in order to explore the “aboutness” (Scott 2001) of the individual CENCER sub-corpora. The keywords generated were used inductively; they provided insight into the most characteristic language and themes in the review genre, during the period 1750–1899. The statistical test used for the keyword calculations was log-likelihood. This was chosen as the most appropriate test of statistical significance in this instance, since “[log-likelihood] based keyword calculations … often work best with … moderately large collections of text”, and log-likelihood is particularly good at revealing both the “thematically prominent” features of a text, and “features likely to be foregrounded/deviant/salient/marked” (Jeaco 2020: 148). As each CENCER sub-corpus is moderately large, and that the purpose of the study reported here is to determine what are thematically prominent discourses, log-likelihood is an appropriate metric for keyword calculation in this instance.

For each of the 15 CENCER sub-corpora, a keyword list of between 117 and 308 words (mean = 197) was returned. In order for each of these keywords to be thematically categorized manually, a p-value threshold of 0.0000000001 was implemented. This low p-value cut-off increased selectivity and ensured that manual analysis was manageable for a single researcher. Having grouped the keywords for each CENCER sub-corpus into semantic categories, to establish themes, collocational patterns and concordance lines were then considered. This phase of analysis allowed conclusions to be drawn as to the patterns of co-occurrence between keywords of relevance and other lexical items.

Collocation and concordancing were not used in a stepwise fashion, as is perhaps implied by March’s (2010) stages, cited above. Instead, an iterative methodology was employed, with the analysis moving fluidly between the two analytical approaches. Thus, whilst keyword analysis was the starting point through which the first words used in tracing diachronic trends in review prescriptivism, thereafter collocation and concordancing were used to explore the data.

Collocations have been calculated using Mutual Information (MI) and t score. As Brezina notes, MI “has traditionally been used in discourse analysis” because it “highlights rare and unique combinations” (2018: 274). The drawback of MI is that it does not take account of the size of a corpus. For this reason, t score has also been used in this study, since the moderately sized sub-corpora in CENCER are considered individually, and t score results are much more dependent on the size of a corpus. Collocates were ordered by MI score, and included in the study only if they had an MI score above 3, a t score above 2, and occurred at least 5 times with the node word. Following McEnery et al. (2010), a L4<R4 span has been used.

Concordancing has allowed the context of every hit for an item of interest to be examined in detail. This was a more time-consuming choice than if sampling had been used, but one considered appropriate to the iterative nature of the research methodology employed. The procedures used for identifying lexical items which function as effective, independent, indicators of prescriptivism or normativity are outlined in detail elsewhere (Malory 2024), so only the salient details will be provided here. This methodology rested on the generation of possible indicators of prescriptivism or normativity, via keyness analysis, collocation, or concordancing. The indicators were then examined in context, and coded as occurring within prescriptive, descriptive, normative, or other non-pertinent discourses. This approach yielded 10 items which function as independent indicators of prescriptivism and normativity in the CENCER corpus; that is to say, their semantic profile is narrow enough that they can be used to predict reliably where prescriptive or normative discourses may be found. These 10 items are all either evaluative adjectives such as ungrammatical and incorrect, and evaluative nouns such as vulgarism and solecism.

The 10 indicators of prescriptivism and normativity used to track trends in these phenomena were identified using a variety of strategies. The initial keyness analysis yielded 2 words which act in this way, either across the CENCER corpus as a whole, or in particular sub-corpora. Further indicators were found via examination of these keywords’ collocates and during concordancing of both the keyword indicators and collocate indicators. A system of coding allowed for the identification of these indicators, and the quantification of prescriptivism and normativity. A 70 % threshold for considering a word an indicator of prescriptivism or normativity was used, whereby a lexical item had to be coded as appearing in prescriptive or normative contexts at least 70 % of the time (either across the corpus as a whole, or in a discrete sub-period). These procedures are outlined in much greater detail elsewhere (Malory 2022, 2024) and only entered into here so far as is necessary for communication how the trends reported in Section 4 were identified.

4 Findings

The purpose of the research reported here was to determine whether the linguistic criticism previously noted to occur in eighteenth-century literary review periodicals (see e.g. McIntosh 1998; Percy 2009, 2010) was a hallmark of the Late Modern (LMod) English genre, or an ephemeral phenomenon within the wider lifespan of the review periodical genre. This Section will be concerned with data analysis which will allow conclusions to be drawn as to an ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ in the CENCER corpus. As was outlined in Section 3, the starting point for this analysis will be keyword data. As such, in Section 4.1, relevant trends in keyness across the 15 10-year sub-corpora covering the period 1750–1899 will be outlined.

4.1 Shifting focus

The keywords for each of the CENCER sub-corpora were categorized thematically, and those belonging to the semantic field of language and grammar were then investigated further. The ultimate objective of this investigation was to determine whether any of the keywords in this category functioned as independent indicators of prescriptivism or normativity within the CENCER corpus. Each of the 15 CENCER sub-corpora yielded a list of between 3 and 32 keywords which fell into this semantic category, with considerable overlap between respective keyword lists.

As the keywords for each sub-corpus were grouped according to thematic categories, it is possible to consider how many keywords belong to the semantic field of language and grammar for each sub-corpus. This preliminary analysis reveals that this semantic field is a consistent feature of all 15 keyword lists. Figure 1, below, shows the frequency of keywords from this semantic field; both in terms of raw frequency and when expressed as a proportion of the overall number of keywords for a given sub-corpus.

Proportional and raw frequency of keywords relating to language and grammar across the CENCER sub-corpora.

Figure 1 shows a rapid increase in the number and proportion of keywords from this semantic category during the later eighteenth century, with a peak in the 1790–1799 sub-corpus. This peak is followed by a sharp downturn in the numbers of keywords of this kind appearing in sub-corpora keyword lists. This provides an early indication that review periodicals became increasingly preoccupied with issues surrounding language and grammar as the eighteenth century progressed, and that this preoccupation may have reached its zenith around the turn of the nineteenth century.

Of course, any such preoccupation with linguistic matters does not equate to prescriptivism or even normativity, and close qualitative analysis is required, to tease out the findings of the keyness analysis. In order to do this, each of the keywords in this semantic category for each of the CENCER sub-corpora were examined in context, using concordancing. This allowed each hit within the corpus for each keyword to be coded according to its prescriptivism, normativity, descriptivism (neutrality), or irrelevance to the present study. This system of coding allowed for the quantification of prescriptivism and normativity, using the 70 % threshold for considering a word an indicator of prescriptivism or normativity that was introduced in Section 3. This approach yielded only 2 keywords which were shown to occur in the context of linguistic criticism in over 70 % of their occurrences, either across the entire corpus, or within certain sub-corpora. These were grammatical and ungrammatical. Section 4.2 will outline the means by which the usage of these words was investigated further.

4.2 Keywords of interest: Grammatical and ungrammatical

The presence of grammatical within the keyword list of a sub-corpus is, of course, not a guarantor of the presence of linguistic criticism. It is, however, an indication that issues surrounding grammaticality are being discussed more often than in the reference corpus used. As a starting point, therefore, the frequency of grammatical across the CENCER corpus can be considered. Figure 2, below, thus shows the raw frequency data for the usage of grammatical in all contexts, across the CENCER sub-corpora.

Raw frequency of grammatical, and grammatical in the context of linguistic criticism by reviewers, across the sub-corpora.

As was the case with Figure 1, above, Figure 2 indicates that concern with issues around grammaticality may have peaked in the final decade of the eighteenth century. Both use of grammatical in the context of linguistic criticism (as determined by concordancing and manual coding) and in all other contexts peak during this sub-corpus.

Further examination revealed that, across the 15 sub-corpora, grammatical occurs in the keyword lists of all but 4 sub-corpora (the exceptions are the 1750-59, 1860-69, 1880-89, and 1890-99 sub-corpora). This means that grammatical is key in 10 consecutive sub-corpora, spanning the century from 1760 until 1859.

It is important to note that grammatical remains key in some of the later nineteenth-century sub-corpora. However, close analysis reveals that whilst it occurs frequently in the context of linguistic criticism in earlier sub-corpora, this is a much less pronounced trend by the latter half of the nineteenth century. Across the corpus as a whole, grammatical occurs in contexts coded as prescriptive or normative only 49 % of the time. However, it is coded as occurring in such contexts in some of the eighteenth-century sub-corpora at least 70 % of the time. Figure 3 exemplifies this, demonstrating how the proportion of instances of grammatical which occur in the context of linguistic criticism changes between 1750 and 1899.

Proportion of occurrences of grammatical in the context of linguistic criticism, across the CENCER corpus.

Figure 3 shows that only in the final sub-corpus of CENCER, that covering 1890–1899, do 100 % (n = 1) of occurrences of grammatical relate to linguistic criticism. However, this represents only a single instance, and can be treated as an anomaly. As Figure 1 also shows, apart from this, the 70 % threshold for considering grammatical an indicator of prescriptivism or normativity is met only during the 1790s, 1800s, and 1810s, and it is thus only within these sub-corpora that grammatical can be considered to function in this way. This is an interesting finding, in terms of the research objective of trying to identify whether the eighteenth-century is an ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ in periodical reviewing, as has previously been suggested (Percy 2009, 2010). It also demonstrates that within these sub-corpora, discourses of grammaticality warrant further investigation, as will be discussed in Section 4.3.

Unlike grammatical, ungrammatical does not appear in CENCER at all after 1819. Concordancing moreover revealed that in every sub-corpus from the beginning of the study period until 1819, if we encounter ungrammatical, then the overwhelming likelihood is that it is in the context of linguistic criticism. In fact, only a single instance of ungrammatical in CENCER does not occur in prescriptive or normative context, as Figure 4 shows.

Proportion of occurrences of ungrammatical in the context of linguistic criticism across the CENCER corpus.

This means that there is very clearly a discrete period during which ungrammatical acts as an indicator of linguistic criticism. It also means that ungrammatical is a much more reliable indicator of prescriptivism or normativity than grammatical; since 97 % of hits for ungrammatical occur in the context of linguistic criticism.

Frequency trends for CENCER keywords grammatical and ungrammatical therefore indicate that prescriptivism and normativity are hallmarks of eighteenth-century and very early nineteenth-century periodical reviewing. Grammatical and ungrammatical both occur in a mixture of (nonspecific) normativity and (specific) prescriptivism during this period, with ungrammatical overwhelmingly occurring in such contexts until it disappears from the corpus from 1820 onwards. Grammatical is used much more consistently throughout the corpus, but can only be considered an effective indicator of linguistic criticism for the discrete period of time covered by the 1790–1819 sub-corpora.

Exploration of these keyword trends therefore yielded useful preliminary findings which indicate that prescriptivism and normativity were an ephemeral feature of the review periodical genre. Subsequent investigations using collocation and further examination of concordance lines in Section 4.3 will explore this apparent trend in more detail.

4.3 An Age of Prescriptivism?

So far in this Section, data from keyword analysis of the CENCER corpus has been used to begin to establish whether any of the sub-corpora can be considered more focused on linguistic criticism than others. In Section 4.1, aggregated keyword data showed how many keywords from each sub-corpus belong to the semantic field of language and grammar. In Section 4.2, frequency data for the keywords grammatical and ungrammatical in contexts of linguistic criticism were reported. On the basis of these findings, the late eighteenth-century seems so far to be the most likely candidate for the ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ label. However, the sub-corpora keyword lists were only a starting point in identifying indicators of prescriptivism and normativity, and 7 others were found in the course of collocation analysis and concordancing. It is important to reiterate at this juncture that the purpose of this paper is not to evaluate the methodology used here (cf. Malory 2024), but rather to report the findings it facilitated, and the light they shed on the sociolinguistic phenomenon of review prescriptivism.

It was reported in Section 4.2 that ungrammatical can be considered a reliable indicator of linguistic criticism, since more than 70 % of its hits in CENCER are found to occur in the context of normativity or prescriptivism. Of the 31 hits for ungrammatical across the corpus, 30 (97 %) are found in such contexts. Figure 5 shows the distribution of these hits across CENCER.

Raw frequency of hits for ungrammatical in the CENCER sub-corpora.

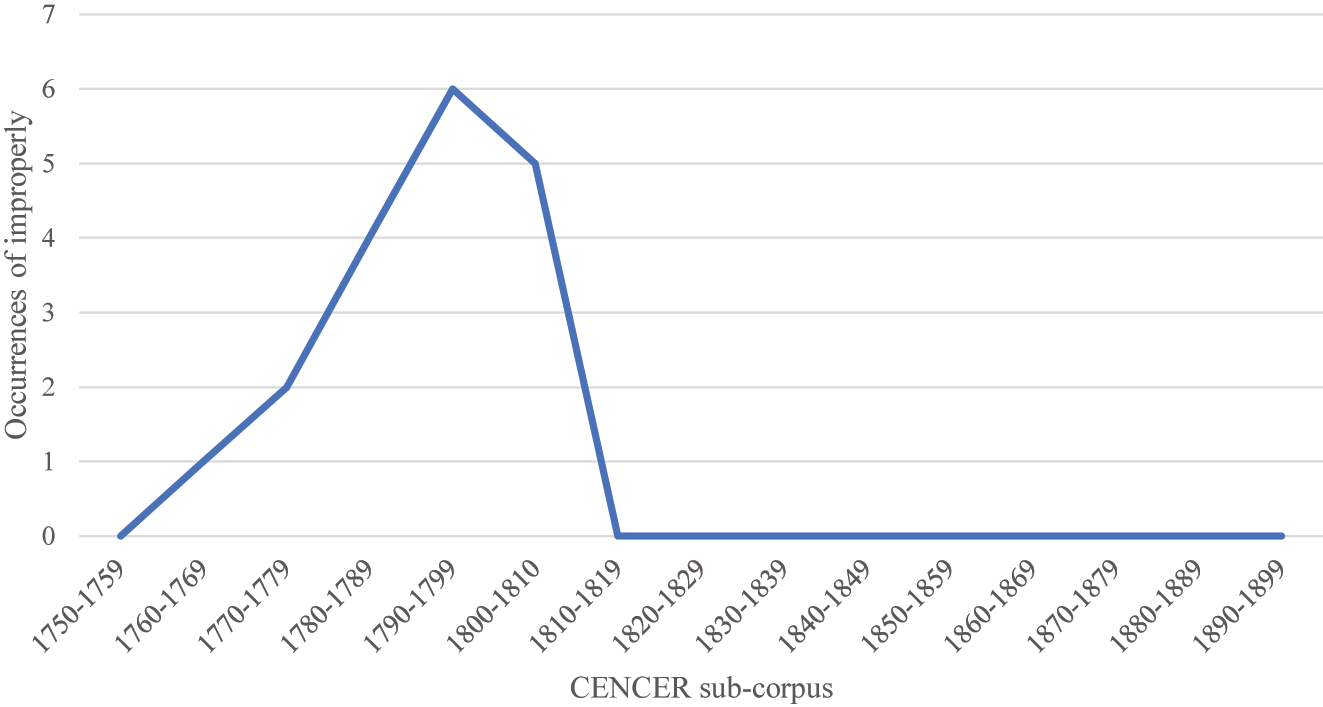

It is notable that, as aforementioned and as Figure 5 shows, the word ungrammatical does not appear at all in the CENCER corpus after 1820. This is also the case for improperly, another lexical item identified as an indicator of linguistic criticism during concordancing. Improperly occurs 18 times in the corpus, and 13 times (72 %) in the context of linguistic criticism. Figure 6 shows this pattern, which again manifests as a gradual rise in the late eighteenth century, followed by a peak and steep decline.

Occurrences of improperly in the CENCER sub-corpora.

Another indicator of linguistic criticism identified during concordancing is inelegant. Inelegant has only 13 hits in the CENCER corpus, but 100 % of these are found in the context of linguistic criticism. Figure 7 shows that its dispersion across the sub-corpora is reminiscent of the frequency patterns for both ungrammatical and improperly. Once again, a gradual rise is followed by a peak in the late eighteenth century, and a dramatic reduction in occurrences.

Occurrences of inelegant in the CENCER sub-corpora.

As Figure 8 shows, use of the phrase error/s of the press also shows a gradual increase, with clear peak in the final decade of the eighteenth century, though is also used several times in the 1830–1839 sub-corpus.

Occurrences of error/s of the press in the CENCER sub-corpora.

The phrase error/s of the press was likewise found to function as an indicator of linguistic criticism. Error was found to be statistical collocate of grammatical, but by itself has too broad a semantic profile to function as an independent indicator. Concordancing revealed, though, that error/s of the press occurs 13 times in the sub-corpus, always in the context of linguistic criticism.

Inaccuracies was also found, during concordancing, to function as an indicator of linguistic criticism, and frequency data for inaccuracies across the CENCER sub-corpora exhibit a similar pattern to that exemplified in the figures for ungrammatical, inelegant, improperly, and error/s of the press, as Figure 9 shows. Inaccuracy/ies appears 29 times in the CENCER corpus, and 27 of these hits, or 93 %, are found to occur in the context of linguistic criticism.

Occurrences of inaccuracy/ies in the CENCER sub-corpora.

Since usage of inaccuracy/ies persists past 1820, and continues until the 1860s and 1870s, its pattern of dispersion is less clear-cut, but a peak in the late eighteenth century may still clearly be discerned. This is likewise the case for solecism/s, as is shown in Figure 10, below. Solecism/s was identified as an indicator during concordancing of grammatical, and occurs 10 times in the CENCER corpus, with 80 % of these instances found to be in the context of linguistic criticism.

Occurrences of solecism/s in the CENCER corpus.

Figure 10 shows a slightly different frequency distribution from that exhibited in earlier figures in this section. Frequency of solecism/s peaks in the 1770–1779 sub-corpus. This early peak is unusual amongst the indicators of linguistic criticism identified. Most, as has been demonstrated, peak in the 1790–1799 sub-corpus, and ungrammatical peaks in the 1780–1789 sub-corpus. Vulgarism/s, which was identified as an indicator of linguistic criticism via concordancing of errors, a statistical collocate of grammatical, likewise displays an unusual frequency distribution As Figure 11 shows, its usage peaks twice; firstly in the 1770–1779 sub-corpus, and later in the 1790–1799 and 1800–1809 sub-corpora.

Occurrences of vulgarism/s in the CENCER corpus.

The later of these twin peaks indicates that use of vulgarism/s is relatively high during the final decade of the eighteenth century, and the first decade of the nineteenth, in line with the findings for other indicators of linguistic criticism considered above. Although vulgarism/s is seldom used, only 11 times across the CENCER corpus, it occurs 100 % of the time in the context of normativity or prescriptivism, making it an extremely reliable indicator of linguistic criticism.

The findings reported in this section so far exhibit a clear pattern, whereby the later eighteenth century and early nineteenth century are a locus for use of lexical items which have been found to function as independent indicators of linguistic criticism. The remaining two indicators of linguistic criticism to be discussed exhibit a later or more sustained peak in usage. This is exemplified by Figure 12, below, which shows the raw frequency of correctness, a word noted in concordancing of grammatical to occur regularly in the context of linguistic criticism.

Occurrences of correctness in the CENCER corpus.

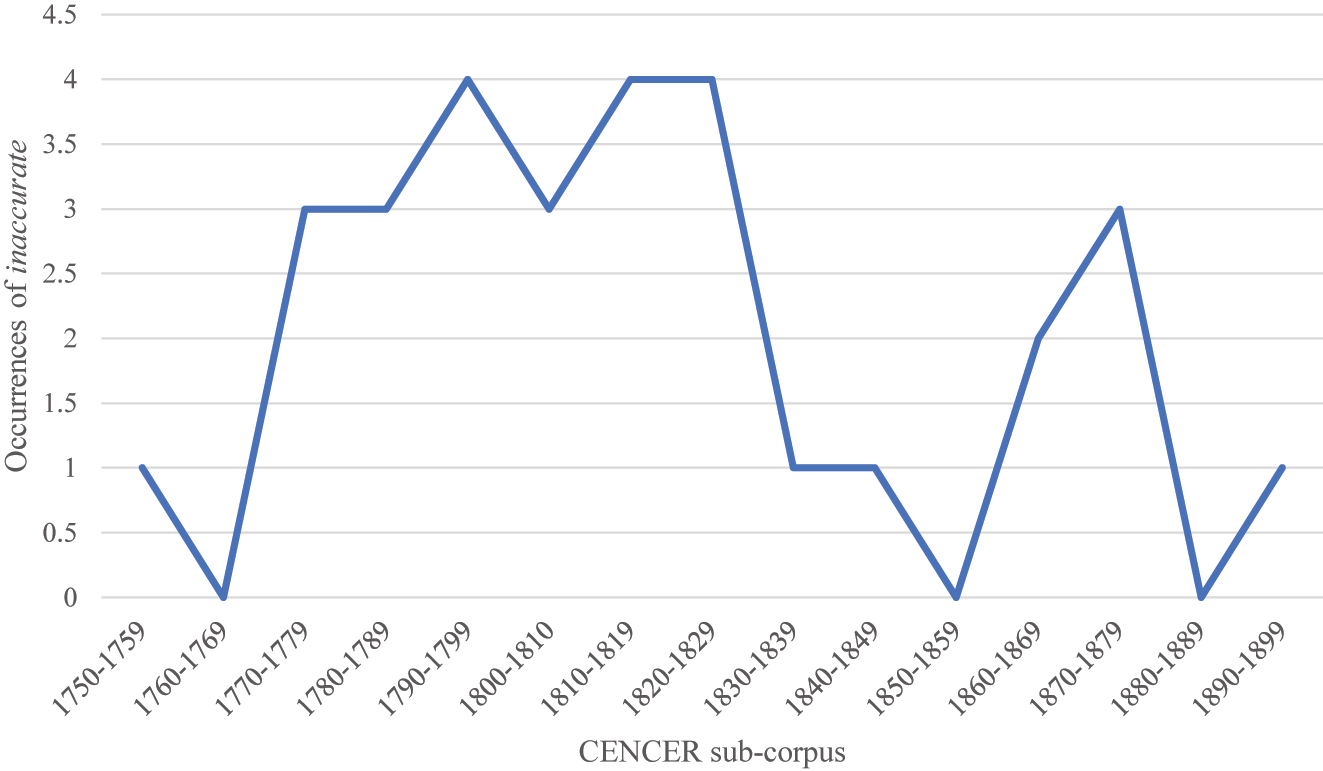

Correctness appears 35 times in the CENCER corpus, with 29 of these hits, or 83 %, found to be in the context of linguistic criticism. Use of correctness peaks in the 1800–1809 sub-corpus, and remains at this level in the 1810–1819 sub-corpus, before falling dramatically in the following decade and rising to a secondary peak in the mid to late nineteenth century. Interestingly, a similar pattern of distribution can be discerned for inaccurate, which was likewise found during examination of concordance lines for grammatical to occur regularly in relevant contexts. Figure 13 shows the dispersion across the sub-corpora of hits for inaccurate, which occurs 30 times in the CENCER corpus, and 22 times (73 %) in the context of linguistic criticism. As Figure 13 shows, occurrences of this word peak between the 1790–1799 sub-corpus and the 1810–1819 and 1820–1829 sub-corpora, before a secondary peak after the mid-century.

Occurrences of inaccurate in the CENCER corpus.

The distributional pattern of usage for correctness and inaccurate is notable, not just because it differs from the other indicators of linguistic criticism identified earlier in this section of the analysis, but also because it is somewhat surprising that these words, which might be expected to have broad semantic profiles, can function as independent indicators of linguistic criticism in CENCER at all. It might be expected that they would appear more in general senses than in contexts of linguistic criticism, but concordancing did not bear this out. Despite these items’ unusual frequency distributions, however, it remains possible to aggregate the data from the indicators of linguistic criticism identified and thereby identify a portion of the study period during which linguistic criticism appears to have reached its peak. Figure 14 shows the amalgamation of all of these indicators, clearly indicating that this peak begins in the late eighteenth century.

Occurrences of indicators of linguistic criticism in the CENCER corpus.

On the basis of these amalgamated data, the period 1770–1819 may be considered the portion of the study period during which most linguistic criticism occurs. This period may therefore be considered an era of linguistic criticism for the review periodicals. As noted in Section 2, linguistic criticism is used here as an umbrella term for all prescriptive and normative activity. However, closer analysis is needed to determine whether the peak in linguistic criticism shown in Figure 14 represents specific prescription, and therefore constitutes an Age of Prescriptivism in periodical reviewing, or merely represents a tendency to posit linguistic performance in a normative way, thereby constituting what we might call an ‘Age of Normativity’. This question will be addressed in the final portion of this section, in Section 4.4.

4.4 An Age of Prescriptivism, or an Age of Normativity?

Upon close examination of the contexts in which the 10 items identified in Section 4.3 as functioning as indicators of linguistic criticism across the CENCER corpus in its entirety occur, 5 are shown to function as indicators of prescriptivism, and 5 of normativity.

On the one hand, error(s) of the press, improperly, inaccuracy, inaccuracies, and inaccurate are associated with specific linguistic criticism and exemplification which is pre- or proscriptive in character. To firstly consider error(s) of the press, close examination of the 13 hits for this phrase across the CENCER corpus revealed that 85 % (n = 11) occur in the context of specific prescriptivism. Often, this takes the form of error exemplification through quotation, as in the following passages from CENCER:

One instance of her failing, in this respect, will suffice:- ‘I never had more inclination to write you, p.2 If a longing lady had said to her husband, “I never had more inclination to bite you,” – or a quarrelsome one, “to fight you,” – or a malicious one “to spight you,”- it had been English.

The above instance does not arise from an error of the press, for the same phrase occurs in several different places, among her best specimens.

Instead of ‘or’ we should read ‘nor’. The mistake is not very capital, and we might have taken it for an error of the press, had not a similar one occurred again in the same page.

Similarly, of the 18 hits for improper(ly) in the corpus, 13 (72 %) occur in the context of linguistic criticism specific enough to be categorized as prescriptive. Again, this often takes the form of error exemplification through quotation, as in the following passages from CENCER:

With respect to the last paragraph, it may also be observed, that the personal pronoun who is improperly used for the government, and that a pest is not the object of extirpation

The fifth is where the definite article ‘the’ is improperly used

This tendency for indicators of prescriptivism to be associated with exemplification of perceived errors is likewise observable in the concordance lines for inaccuracies, inaccurate, and inaccuracy, as demonstrated in the following passages from CENCER:

[A] few grammatical inaccuracies, such as is for are, page 3; began for begun, page 7; is for are, line 16, page 114

“Aims perfection’s goal,” in the same stanza, is also inaccurate, the verb “to aim” requiring a preposition

Of the 29 instances of inaccuracy/ies in CENCER, 93 % (n = 27), occur in the context of linguistic criticism. Of the 30 hits for inaccurate, 73 %, (n = 22) occur in such contexts.

Error(s) of the press, improperly, inaccuracy, inaccuracies, and inaccurate are thus associated with specific linguistic criticism and exemplification which is pre- or proscriptive in character and can be considered reliable means of identifying and retrieving prescriptive dogma in the CENCER corpus. On the other hand, ungrammatical, solecism(s), inelegant, correctness, and vulgarism(s) function as indicators of normativity, due to their association with nonspecific linguistic criticism which nonetheless upholds the standard language ideology. Ungrammatical appears 31 times across the CENCER corpus, with 84 % (n = 26) of these hits occurring in the context of normativity and only 13 % (n = 4) in the context of specific prescriptivism. The following examples from CENCER exemplify the kinds of nonspecific linguistic criticism usually associated with the presence of ungrammatical in the corpus.

In the second volume we meet with many examples of ungrammatical and vulgar language.

A superficial declamation, in a mean and ungrammatical style, on the want of ready employment for manufacturers

Likewise, solecism(s), inelegant, correctness, and vulgarism(s) are associated with nonspecific linguistic criticism, and function as indicators of discourses which construct grammaticality as fixed and binary but are less useful in identifying specific instances of prescription or proscription. These indicators of normativity, as opposed to prescriptivism, are however valuable in facilitating the exploration of language attitudes, and the discursive construction of grammaticality during the Late Modern period of English.

5 Concluding remarks

This paper has been concerned with determining whether it is possible to use protocols from Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies (CADS) to identify a historical period during which prescriptive activity was at its height within a specific genre of English publication. This genre, the literary review periodical, is one that is thought to have played a significant role in the social history of the English language, by bringing prescriptive and normative discourses to much wider audiences than contemporaneous codifying texts were able to (McIntosh 1998; Percy 2009, 2010). In demonstrating that these periodicals’ intense preoccupation with matters of grammaticality was ephemeral and confined to the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, the findings reported here therefore shed new light on the genre of the review periodical and its role in Late Modern British society. These findings indicate that CADS methodologies may be useful in future work considering how interest in grammaticality has changed over time during the past centuries, which contain a number of periods previously labelled as an ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ (Anderwald 2016; Auer 2009; Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2019).

As was outlined in Section 1, the purpose of this paper is not to make generalizable claims about an Age of Prescriptivism in English, but rather to contribute to the body of knowledge of how different contexts and variables condition our perception of an Age of Prescriptivism in English. The methodology employed here therefore suggests one way of identifying and approaching ephemeral periods of intense preoccupation with grammatical correctness. In closing, however, it behoves us to ask whether a label as nebulous and context-dependent as the ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ has value, or whether it contributes to the kind of overly-simplistic conceptions of Late Modern English bemoaned by Anderwald (2019: 89) and others (cf. Jones 1989: 279) in recent decades. From the narrow perspective of studying the sociolinguistic role of Late Modern review periodicals, the findings reported here are helpful. From a broader perspective of understanding prescriptive phenomena, the finding of a discrete ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ in the review genre may contribute to the incremental advancement of understanding of how normativity functions diachronically, as a sociolinguistic and cultural phenomenon. Much further work is needed, however, before a holistic understanding of prescriptive and normative phenomena are achieved. This paper has presented one possible avenue for further investigation, by suggesting a CADS-based methodology which might be useful.

Funding source: Arts and Humanities Research Council UK (AHRC)

-

Research funding: This work was funded br Arts and Humanities Research Council UK (AHRC).

Text files and words in each sub-corpus and in CENCER in total.

| Sub-period | Number of text files | Sub-corpus word count |

|---|---|---|

| 1750–59 | 23 | 79,764 |

| 1760–69 | 31 | 81,534 |

| 1770–79 | 29 | 80,133 |

| 1780–89 | 37 | 82,605 |

| 1790–99 | 34 | 81,133 |

| 1800–09 | 30 | 82,746 |

| 1810–19 | 24 | 82,411 |

| 1820–29 | 11 | 82,315 |

| 1830–39 | 8 | 82,158 |

| 1840–49 | 9 | 80,962 |

| 1850–59 | 8 | 81,159 |

| 1860–69 | 7 | 83,005 |

| 1870–79 | 5 | 79,978 |

| 1880–89 | 6 | 80,051 |

| 1890–99 | 7 | 81,508 |

| 1749–1899 | 269 | 1,221,462 |

References

Anderwald, Lieselotte. 2012. Clumsy, awkward or having a peculiar propriety? Prescriptive judgements and language change in the 19th century. Language Sciences 34(1). 28–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2011.06.002.Search in Google Scholar

Anderwald, Lieselotte. 2014. Measuring the success of prescriptivism: Quantitative grammaticography, corpus linguistics and the progressive passive. English Language and Linguistics 18(1). 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674313000257.Search in Google Scholar

Anderwald, Lieselotte. 2016. Language between Description and prescription: Verbs and verb categories in nineteenth-century grammars of English. Oxford Studies in the History of English. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190270674.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Anderwald, Lieselotte. 2019. Empirically charting the success of prescriptivism: Some case studies of nineteenth-century English. In Carla Suhr, Terttu Nevalainen & Irma Taavitsainen (eds.), From Data to evidence in English language research, vol. 83. Language and Computers, 88–108. Leiden; Boston: Brill.10.1163/9789004390652_005Search in Google Scholar

Auer, Anita. 2009. The subjunctive in the Age of Prescriptivism: English and German developments during the eighteenth century. Basingstoke [England]; New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/9780230584365.Search in Google Scholar

Auer, Anita & Victorina González-Díaz. 2005. Eighteenth-century prescriptivism in English: A re-evaluation of its effects on actual language usage. Multilingua – Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication 24(4). 317–341. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult.2005.24.4.317.Search in Google Scholar

Basker, James G. 1988. Tobias smollett, critic and journalist. Newark: London: University of Delaware Press; Associated University Presses.Search in Google Scholar

Baugh, Albert, C. & Thomas Cable. 2012. A history of the English language. London: Routledge. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=EmJcMAEACAAJ.Search in Google Scholar

Brezina, Vaclav. 2018. Statistical choices in corpus-based discourse analysis. In Charlotte Taylor & Anna Marchi (eds.), Corpus approaches to discourse: A critical review, 259–280. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315179346-12Search in Google Scholar

Calvet, Louis-Jean. 2017. La sociolinguistique. 9e éd. mise à jour. Que sais-je ?, n° 2731. Paris: Que sais-je ?.10.3917/puf.calve.2017.01Search in Google Scholar

De Smet, Hendrik, Hans-Jürgen Diller & Jukka Tyrkkö. n.d. The corpus of Late Modern English texts, version 3.0. The Corpus of Late Modern English Texts, Version 3.0. https://perswww.kuleuven.be/∼u0044428/clmet3_0.htm (accessed 26 September 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Desagulier, Guillaume. 2017. Corpus linguistics and statistics with R: Introduction to quantitative methods in linguistics. New York, NY: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.10.1007/978-3-319-64572-8Search in Google Scholar

Donoghue, Frank. 1996. The fame machine: Book reviewing and eighteenth-century literary careers. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Haugen, Einar. 1997. Language standardization. In Nikolas Coupland & Adam Jaworski (eds.), Sociolinguistics: A reader, 341–352. London: Macmillan Education UK.10.1007/978-1-349-25582-5_27Search in Google Scholar

Jeaco, Stephen. 2020. Key words when text forms the unit of study: Sizing up the effects of different measures. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 25(2). 125–154. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.18053.jea.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, Charles. 1989. A history of English phonology. Longman Linguistics Library. London; New York: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Krogull, Andreas. 2018. Policy versus practice: Language variation and change in eighteenth-and nineteenth-century Dutch. Utrecht: Netherlands Graduate School of Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Leonard, Sterling Andrus. 1929. The doctrine of correctness in English usage, 1700–1800. Studies in Language and Literature – University of Wisconsin. Madison, Wisconsin: Columbia University. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=fs9ZAAAAMAAJ.Search in Google Scholar

Malory, Beth. 2022. The transition from Abortion to Miscarriage to describe early pregnancy loss in British Medical Journals: A prescribed or natural lexical change? Medical Humanities March. 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2021-012373.Search in Google Scholar

Malory, Beth. 2024. “A vulgarity of style which lies deeper than grammatical solecisms”: Developing a corpus-assisted approach to identifying prescriptive and normative discourses. Corpora 19(2).10.3366/cor.2024.0306Search in Google Scholar

Marchi, Anna. 2010. “The Moral in the Story”: A diachronic investigation of lexicalised morality in the UK Press. Corpora 5(2). 161–189. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2010.0104.Search in Google Scholar

McEnery, Tony, Richard Xiao & Yukio Tono. 2010. Corpus-based language studies: An advanced resource book. Reprinted. Routledge Applied Linguistics. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

McIntosh, Carey. 1998. The evolution of English prose, 1700–1800: Style, politeness, and print culture. Cambridge [England]; New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511582790Search in Google Scholar

Milroy, James & Lesley Milroy. 2012. Authority in language: Investigating standard English. In Routledge linguistics classics. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Percy, Carol. 2000a. ‘Project overview’. Database. A database of linguistic and stylistic criticism in eighteenth-century periodical reviews the monthly review, first series (1749–1789) & the critical review, first series (1756–1789). 2000. Available at: https://cpercy.artsci.utoronto.ca/reviews/overview.htm.Search in Google Scholar

Percy, Carol. 2000b. “Easy women”: Defining and confining the “Feminine” style in eighteenth-century print culture. Language Sciences 22(3). 315–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0388-0001(00)00009-7.Search in Google Scholar

Percy, Carol. 2008. Liberty, sincerity, (In)Accuracy: Prescriptions for manly English in 18th-century reviews and the “Republic of Letters”. In Joan C. Beal, Carmela Nocera & Massimo Sturiale (eds.), Perspectives on prescriptivism. Linguistic Insights, v. 73, 113–147. Bern; New York: P. Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Percy, Carol. 2009. Periodical reviews and the rise of prescriptivism: The monthly (1769–1844) and critical review (1756–1817) in the eighteenth century. In Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade & Wim van der Wurff (eds.), Current issues in Late Modern English, vol. 77. Linguistic Insights, 117–152. Bern; New York: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Percy, Carol. 2010. How eighteenth-century book reviewers became language guardians. In Päivi Pahta, Minna Nevala, Arja Nurmi & Minna Palander-Collin (eds.), Pragmatics & beyond new series, vol. 195, 55–85. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/pbns.195.04perSearch in Google Scholar

Poplack, Shana & Nathalie Dion. 2009. Prescription vs. Praxis: The evolution of future temporal reference in French. Language 85(3). 557–587. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.0.0149.Search in Google Scholar

Scott, Mike. 2001. 3. Comparing corpora and identifying key words, collocations, and frequency distributions through the word smith tools suite of computer programs. In Mohsen Ghadessy, Alex Henry & Robert L. Roseberry (eds.), Studies in corpus linguistics, vol. 5:47. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/scl.5.07scoSearch in Google Scholar

Scott, Mike. 2020. WordSmith Tools Version 8. Stroud: Lexical Analysis Software.Search in Google Scholar

Straaijer, Robin. 2009. Deontic and epistemic modals as indicators or prescriptive and descriptive language in the grammars by Joseph Priestley and Robert Lowth. In Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade & Wim van der Wurff (eds.), Current issues in Late Modern English, vol. 77. Linguistic Insights, 57–87. Bern; New York: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Sundby, Bertil, Anne Kari Bjørge & Kari E. Haugland. 1991. A dictionary of English normative grammar, 1700–1800. Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science, v. 63. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: J. Benjamins Pub. Co.10.1075/sihols.63Search in Google Scholar

Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. 2011. The Bishop’s grammar: Robert Lowth and the rise of prescriptivism in English. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199579273.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. 2019. DESCRIBING PRESCRIPTIVISM: Usage guides and usage problems in British and American English. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429263088Search in Google Scholar

Vorlat, Emma. 1996. Lindley Murray’s prescriptive canon. In Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), Two hundred years of Lindley Murray, 163–182. The Henry Sweet Society Studies in the History of Linguistics, v. 2. Münster: Nodus Publikationen.Search in Google Scholar

Yáñez-Bouza, Nuria. 2008. Preposition stranding in the eighteenth century: Something to talk about. In Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), Grammars, grammarians and grammar-writing in eighteenth century England, 251–277. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110199185.4.251Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Out of the mouths of babes: children and the formation of the Río de la Plata Spanish address system

- The role of nativeness in early modern foreign language learning: evidence from teaching materials

- ‘The seas was like mountains’: intra-writer variation and social mobility in Irish emigrant letters

- Locating the ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ in Late Modern periodical reviews: a corpus-assisted discourse analytic approach

- Language maintenance and shift in a Swiss community on the Black Sea

- Book Reviews

- Ivor Timmis: The discourse of desperation: late 18th and early 19th century letters by Paupers, Prisoners, and Rogues

- Kai Witzlack-Makarevich: Sprachpurismus im Polnischen. Ausrichtung, Diskurs, Metaphorik, Motive und Verlauf. Von den Teilungen Polens bis zur Gegenwart

- Olga Timofeeva: Sociolinguistic variation in Old English: Records of communities of people (Advances in historical sociolinguistics 13)

- Anna D. Havinga & Bettina Lindner-Bornemann: Deutscher Sprachgebrauch im 18. Jahrhundert: Sprachmentalität, Sprachwirklichkeit, Sprachreichtum (Germanistische Bibliothek 71)

- Megumi Sato: Sprachvariation und Sprachwandel im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Untersuchungen zur Kasusrektion der Präpositionen wegen, statt, während und trotz

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Out of the mouths of babes: children and the formation of the Río de la Plata Spanish address system

- The role of nativeness in early modern foreign language learning: evidence from teaching materials

- ‘The seas was like mountains’: intra-writer variation and social mobility in Irish emigrant letters

- Locating the ‘Age of Prescriptivism’ in Late Modern periodical reviews: a corpus-assisted discourse analytic approach

- Language maintenance and shift in a Swiss community on the Black Sea

- Book Reviews

- Ivor Timmis: The discourse of desperation: late 18th and early 19th century letters by Paupers, Prisoners, and Rogues

- Kai Witzlack-Makarevich: Sprachpurismus im Polnischen. Ausrichtung, Diskurs, Metaphorik, Motive und Verlauf. Von den Teilungen Polens bis zur Gegenwart

- Olga Timofeeva: Sociolinguistic variation in Old English: Records of communities of people (Advances in historical sociolinguistics 13)

- Anna D. Havinga & Bettina Lindner-Bornemann: Deutscher Sprachgebrauch im 18. Jahrhundert: Sprachmentalität, Sprachwirklichkeit, Sprachreichtum (Germanistische Bibliothek 71)

- Megumi Sato: Sprachvariation und Sprachwandel im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Untersuchungen zur Kasusrektion der Präpositionen wegen, statt, während und trotz