Abstract

This article examines three lost short comedies produced alongside Labourer’s Love by the Mingxing Film Studio in 1922: The King of Comedy Visits Shanghai (Huaji dawang you hu ji), Havoc in a Bizarre Theatre (Danao guai xichang), and The Naughty Kid (Wantong). I propose to look beyond the extant Labourer’s Love and instead to delve into the broader intertextual, intermedial fabric of early film comedy for a re-evaluation of this neglected genre. Drawing on advertising texts, stills, and film reviews, this study corrects misinformation and supplements new data, based on which I posit two notions for a reconceptualization of early Chinese comedy film. First, I propose the Chinese concept of renao (“hot noise”) as a particular sensorial-somatic mode of experience to account for the Chinese engagement with film comedy in the tumultuous 1920s. Second, I borrow the Chinese poetic device of allusion to interpret their widespread references to Hollywood films in structural, narrative, and visual terms. Through the prism of allusion, the appropriation and re-production of Hollywood elements can be regarded as a means of adding authority to inchoate Chinese filmmaking, while at the same time complicating familiar topoi, symbols, and imageries in culturally sensitive ways.

As Zhang Zhen puts it, it is surprising that Labourer’s Love (Laogong zhi aiqing 勞工之愛情, 1922), such a “noncanonical” or even “frivolous” film, “should have survived the ravages of history and stands now as the ‘beginning’ of Chinese cinema” (Zhang 1999, 27). Its unintended becoming one of the “first” attests to the trick of historical contingency, the trick of illuminating certain things, while obscuring others. Being the sole “brand ambassador” of Chinese silent-era comic shorts, Labourer’s Love has entered privileged retrospective programmes, film history courses worldwide, and the horizon of scholarly inquiries, representing a slice of post-May-Fourth Chinese society, the Shanghai-based vernacular mass culture, a sample of Hollywood-inspired filmic language, and a remnant of the pioneering Mingxing Company’s filmmaking enterprise (Dong 2008; Huang 2014, 34–38; Rea 2021, 21–37; Zhang 1999). Yet, what if the whimsical magician of history had picked, say, The King of Comedy Visits Shanghai (Huaji dawang you Hu ji 滑稽大王遊滬記, 1922, hereafter King of Comedy), to survive the passage of time? Would the beginnings of Chinese film history have to be rewritten, accordingly?

This article is an attempt to tap into the obscured “others”—the three lost shorts produced alongside Labourer’s Love by Mingxing in its first year of existence: King of Comedy, Havoc in a Bizarre Theatre (Danao guai xichang 大鬧怪戲場, hereafter Havoc), and The Naughty Kid (Wantong 頑童, hereafter The Kid). My aim is not so much to consider the counterfactual scenario as to draw attention to the forgotten for a rethinking of early Chinese film comedy, a largely neglected genre in the historiography of Chinese cinema. Inasmuch as the survival of Labourer’s Love grants us precious access to this early visual world, its very preservation may have unwittingly obstructed our view of a bigger picture. Looking beyond Labourer’s Love would allow us to conduct a still much-needed “cultural archaeology of the new medium” (Elsaesser 1990, 1) on the Chinese site of laughter in the early 1920s.

Drawing on advertising texts, stills, and film reviews, the first part of this article presents a contextualization of the lost Mingxing comedies, clearing up widespread misconceptions regarding their narrative, filmic, and extra-filmic facets. I propose the Chinese notion of renao 熱鬧 (boisterous; literally, “hot noise”) as a particular sensorial-somatic mode of experience to account for the Chinese engagement with early film comedy. On this basis, in the second part I locate the films in a network of generic conventions, aesthetic tropes, and cross-cultural references in and outside the cinematic field. I borrow the notion of allusion (diangu 典故), an essential technique in classical Chinese poetry, to conceptualize early Chinese film comedy as a dynamic brew of creativity and cultural appropriation. Through the Chinese conceptual lens, I re-position the genre inside its original milieu of emergence.

1 The Ambience of Hot Noise

Although Chinese film historiography tends to canonize narrative film, or “serious feature-length moral drama” (changpian zhengju 長片正劇), we should not forget that of approximately 50 fictional films made in China before 1923, 24 are short comedies (Dong 2008, 2; Rao 2005, 2–3), and Labourer’s Love is only one of them. Zhang Zhen’s seminal essay aptly defines Labourer’s Love as a hybrid text, one that was situated in the indigenous teahouse culture of Shanghai, while displayed stylistic features akin to those of “cinematic bricolage” or the “cinema of attractions” in early film traditions (Zhang 1999). The latter aspect is taken up in more detail in Dong Xinyu’s compelling reading of Labourer’s Love in relation to a range of genre conventions of slapstick comedy. She considers the film as “a mischief comedy of inventions,” embodying “a locally- and globally-informed operational aesthetic” that centres on a “playful display of play” (5).

These interpretative frameworks are valid to suggest the overall features of early Chinese screen comedy, and the affective modes of laughter, astonishment, and fascination as the earliest movie-going experience. However, if we delve into a larger repertoire of textual sources, in juxtaposition with the only visual residue, what else can we glean? The following discussion takes up this task, drawing primarily on theatre advertisements. It is worth re-emphasizing the importance of this material in early film studies. At the textual level, advertising bears faithful witness to the when, where, and what questions foundational to any historical inquiry into the fragmented kaleidoscope of early cinema. Moreover, advertisements function intertextually, in a dynamic dialogue with the filmic text through the common practice of signposting visual attractions for contemporary movie-goers. To a certain degree, the silent-era film advertisement resembles the present-day trailer. Furthermore, if reading film advertisements contextually, within a wider economy of popular entertainment (the advertisements for which normally inhabit the same newspaper spaces), an understanding of the situatedness of early cinema may be achieved. My examination of the three lost films will be textually guided and intertextually/contextually informed by two advertisements posted by Mingxing in the leading Shanghai newspaper Shenbao (Figures 1 and 2).

Advertisement for King of Comedy and Labourer’s Love. Source: Shenbao Oct. 5, 1922: 9.

Advertisement for Havoc and The Kid. Source: Shenbao Jan. 28, 1923: 17.

The textual side of the two advertisements clarifies the misty scene as to the basic historical facts that have been inaccurately presented in existing literature.[1] Starting on October 3, 1922, Mingxing placed a series of advertisements on the front pages and advertising pages of Shenbao, announcing the screening of its first output, the comic duo King of Comedy and Labourer’s Love. Premiered at the Olympic Theatre (Xialing peike 夏令配克) on October 5, the Moon Festival, they were initially scheduled to show three times a day for two days, but the programme extended for two more days, which implies its appeal to the Chinese spectating masses. The second cluster of films were released three months after, including another comic duo (Havoc and The Kid) and three actuality films under the rubric of “Shanghai news” (Shanghai xinwen 上海新聞). Supplying the factual data aside, the promotional material suggests two important areas open to further interpretation from alternative theoretical lenses.

The first concerns the exhibition format and perception mode. The Mingxing programme shown at Olympic from January 26 to 28, 1923 opened with a musical overture performed by a Philippine orchestra, followed by three “Shanghai news” actualities (gymnastics performances, athletic games, and a ceremonial parade), interspersed with a live acrobatic performance, and completed with the three-reel Havoc and one-reel The Kid (Figure 2; also see Anonymous 1923a). The textual witness to the programme indicates that these short comedies were experienced fundamentally differently from the way we watch Labourer’s Love today. Scholars have argued that the early movie-going experience was “essentially a theatre experience, not a film experience” (Hansen 1991, 99; based on Koszarski 1990, 9–61). The variety format (a mix of live acts, musical performances, newsreels, comedy shorts, cartoons, etc. that prevailed in the first few decades of film in the USA and elsewhere) constituted part of “the system of attraction” in Tom Gunning’s frame (2006, 386). Writing about mid-1920s Berlin picture palaces, Siegfried Kracauer observed: “The discontinuous sequence of splendid sense impressions” (afforded by the variety format) conveyed “precisely and openly to thousands of eyes and ears the disorder of society,” enabling them “to evoke and keep awake the tension that must precede the inevitable radical change” (Hansen 2012, 69). Hinging upon such “a structurally distinct mode of perception,” Kracauer saw the political significance of the cinema in its capacity of “distraction” (Zerstreuung) and as a blueprint for a masses-oriented “alternative public sphere” (ibid., 69–70). In Zhang Zhen’s discussion of Shanghai amusement halls (youle chang 游樂場) which hosted a variety of live performances and attractions (including earliest film screenings), she asserts that such venues fostered “an embodied metropolitan mode of spectatorship with a mobilized gaze” (2005, 64).

All the angles can partly explain the film-going experiences of Shanghai “petty urbanites” (xiaoshimin 小市民). Here I briefly venture to put forward a proposition, one that locates the therapeutic role of comedy and the variety format in the Chinese perception mode of renao, hot noise. Denoting “the festive ambience generated through an assembly of warm bodies, a polyphony of participatory voices, and a kaleidoscope of sense impressions” (Li 2020, 7–8), the notion of renao is central to Chinese experiences of popular religion, traditional theatre, festivals, and even Mao-era open-air cinema. Christopher Rea has also explored this aesthetic of excitement (he translated as “heat and uproar”) in post-war comedy film culture (2021, 265–71). The Chinese penchant for renao, I contend, also accounts for the appeal of comedy film and the variety format. The Mingxing programme of January 1923, for example, must have generated an electrifying vibe: sonic stimulation from the live music, animated physicality conveyed through the athletic and ceremonial events on screen and the acrobatic performance on stage, and excitement of the filmic “havoc” (danao 大閙), a traditional theatrical element to produce the effect of renao.[2]

Seen contextually, this multisensory, multimedial feast was part and parcel of the mass entertainment scene of 1920s Shanghai, with renao as a key feature. For example, on the Shenbao page where the advertisement for Labourer’s Love and King of Comedy appeared, six theatres posted their programmes, among which two make explicit reference to the renao quality: a “civilized play” (wenmingxi 文明戲) and a Peking opera that both culminate in ceremonial assemblies. Another Peking opera programme highlights its “intricate stage set and elaborate props” (huanshu jiguan, quanxin bujing 幻术机关, 全新布景). An all-female Cantonese opera troupe presents a detective drama titled “A Monk in Boiled Water” (gunshui lu heshang 滾水淥和尚), with “a bizarre set” (peijing liqi 配景離奇). Interestingly, there is a scene in Labourer’s Love in which the fruit vendor pushes a ruffian into a tub of hot water. Dong Xinyu points out that a hot water gag in Buster Keaton’s 1921 film The Haunted House might be the inspiration for this scene (18). This Cantonese drama, however, indicates an indigenous fascination with hyperbolic sensorial stimuli. Facilitated by the emergence of new-style theatres in the late 1900s, there arose a widespread obsession with technically intricate stage sets, eye-catching props, and overstimulation adopted by both traditional genres of theatre and the new civilized play (especially the comic play quju 趣劇 sub genre). Screening the early film comedies should be located within this shifting “representational regime of the new-style theatre space” (Goldstein 2003, 770–773; the quoted phrase on 773). Not only a clone of Western film-going norms, but their exhibition format was also grounded on the ingrained popular taste for renao and the modern psychological needs for stimulation in the colonial-industrial world of China’s treaty ports. The sensory-somatic space of renao warrants further research in Chinese silent film studies.

The second arena unveiled by the publicity material is the narrative and visual features of the lost films. As is seen in Figures 1 and 2, these “textual trailers” are elaborate, listing the key attractions emblazoned either with bigger font size or with the recurring cue “very funny” (feichang youqu 非常有趣). A common advertising policy in Hollywood as well, Tom Gunning regards the stylistic feature of emblazoning (often using “See!”) as illustrative of the “primal power of the attraction running beneath the armature of narrative regulation” (2006, 387). A comparison of the extant copy of Labourer’s Love [3] and its advertising text (Figure 1) testifies the interplay of narrative and attraction. Among the seven features enumerated, the first five are presented chronologically in accordance with the plotline. The fruit-peddler Carpenter Zheng is introduced in the first feature, highlighting his peculiar skills as a bricoleur as well as the “operational aesthetic” at work. The second feature is concerned with Doctor Zhu, his “charlatan” (jianghu langzhong 江湖郎中) status, and his misfortunes. The next two are dedicated to the hot water gag and the boisterous kids stealing fruit, whereas the dramatic climax (the staircase scene) is introduced as the fifth feature. The last two emphasize the use of local settings and the diversity of its characters. In short, the advertising text faithfully reflects both the narrative and attractions of Labourer’s Love. Having established the visual–textual link, we can venture into piecing together the jigsaw puzzles of the lost films. The features of King of Comedy are introduced as:

The King of Comedy stands astride two automobiles, flirting with two women. The adventurous plot is very funny. 滑稽大王脚踏兩汽車, 同二女郎一路講情話。冒險情節, 非常有趣。

The King of Comedy arrives at the office, encounters a fatty, gets involved in exciting fights, does dramatic somersaults. Very funny. 滑稽大王到公司, 惹出一個大胖子來, 造成幾場奇巧的打局, 翻出幾多奇巧的筋斗。非常有趣。

The King of Comedy goes to the countryside, sits in a sedan chair, with his oversized leather shoes poking out the bottom, walking with the sedan chair. Even funnier. 滑稽大王下鄉, 大座其通天轎, 一雙大皮鞋脚, 露出在轎肚底下, 一步步跟著走。更加非常有趣。

A baby drives an oxcart in the field, a water buffalo listening to his commands. Very funny. 田間一個小寶寶, 能夠斗牛車; 柵中一只老黃牛, 聼他的號令。非常有趣。

The King of Comedy gets entangled in a village couple’s waterwheel, like a frog dangling from a fishing rod. Very funny. 滑稽大王被踏水車的鄉下夫妻大吊其田鷄, 非常有趣。

The King of Comedy visits a scholar’s house, makes ludicrous mistakes when eating and sleeping, taking a wardrobe as his bed. Very funny. 滑稽大王作客紳士家, 吃也閙笑話, 悃也闖窮禍, 把衣櫥當作床鋪。非常有趣。

A humorous couple has a whimsical fantasy, bringing the real and fake Kings of Comedy to meet each other. Very funny. 一對滑稽夫妻, 異想天開, 弄得真假滑稽大王兩碰頭。非常有趣。

This “textual trailer” adds details to the well-known generic storyline of “the copycat Chaplin ‘going native’” (Zhang 2005, 13). The January 1923 advertisement (Figure 2), however, reveals that the widely held assumption of Havoc as another “Chaplin-in-China” film (where Chaplin and Harold Lloyd make a big scene in a theatre) is categorically wrong (Cheng et al. 1963, 58; Dong 2008, 11–12; Zhang 2005, 13). In fact, a close-up shot of Lloyd that opens the film only functions as a hoax until when the camera zooms out, disclosing that it is just a photo on the wall of a movie fan’s bedroom. The movie fan, a chef (played by the “Carpenter Zheng” actor Zheng Zhegu 鄭鷓鴣), is the true protagonist of this comedy. Preoccupied with his star dream, the absent-minded chef serves up uncooked living animals as dishes—an unintended literal allusion to the cinematic medium as “distraction.” Quitting his chef’s job and failing to secure a new job as an actor owing to his “unnatural acting,” the distraught man gets involved in a series of chases and beatings. In a park, he spots a man stealing sugar, and he replaces sugar with gravel, causing the thief’s teeth to fall; an exciting scene of slapstick naturally follows. Later he sneaks into a “bizarre theatre” (guai xichang) and gets into trouble when he debunks the scam of a double-headed freak. As he busies himself in a Chaplinesque chase, his naturalistic performance impresses the film director in the studio, and the chef’s silver dream finally comes true (Anonymous 1923b; Shuang 1923).

The same advertisement also brings to light that the one-reeler The Kid was in fact a Mingxing production, whereas it has been credited to the Shanghai Shadowplay Company (Shanghai yingxi gongsi 上海影戲公司) in standard history (Cheng et al. 1963, 525).[4] A probable tribute to Lumière’s L’Arroseur Arrosé (The Sprinkler Sprinkled, 1895), The Kid features a mischievous child (played by Dan Erchun 但二春, the earliest Chinese child film star), who “knows how to tease the police, to get free food by force, to steal duck eggs, and to drive a car…”

What else, other than the operational aesthetic and cinematic bricolage detectable in Labourer’s Love, can we read from these jigsaw puzzles? The following investigation aims to identify a larger repertoire of cinematic idioms and clichés in these early Chinese film comedies. The first three decades of film history witnessed a collective building of visual icons, repeated images, and prototypes. Despite the commonplace industrial practice of borrowing and recycling across national borders, this aspect has been often obscured in the nationalism-infused discourse of Chinese cinema (Dong 2008, 14–15). My anatomy of the “borrowed” visual lexicon, however, illuminates not the lack of originality but the creative vibrancy of early Chinese filmmaking. This Chinese economy of laughter, as “eclectic and ‘opportunistic,’ tongue-in-cheek and playful, iconoclast and sarcastic” as what Elsaesser has observed about early 1920s Weimar cinema (2000, 37–38), embodies what I call an art of allusion that knows no national and cultural boundary.

The use of allusions (diangu) is a literary device characteristic of classical Chinese poetry. Its function, as James Liu sees it, is not “as a display of erudition but as an organic part of the total poetic design” (Liu 1962, 136). Employed to reveal an analogy or a contrast, allusions are a means of adding “the authority of past experience to the present occasion” and “introducing additional implications and associations” (ibid., 135–136). Therefore, Liu argues that “a poem that uses derived ideas and expressions can yet be original in the way these ideas and expressions are put together” (ibid., 145). It is in this spirit that I consider the early Chinese lexicon of film comedy analogous to the poetic repertoire of allusions. Just like learned Chinese poets and readers were well-versed in literary history, 1920s Shanghai filmmakers and audiences equally commanded a high level of film literacy. Building on this foundation, the Chinese cinematic art of allusion should be conceived as a means of calling up a chain of associations embedded in the global family of film comedy, while responding to specific cultural sensibilities.

2 An Art of Allusion

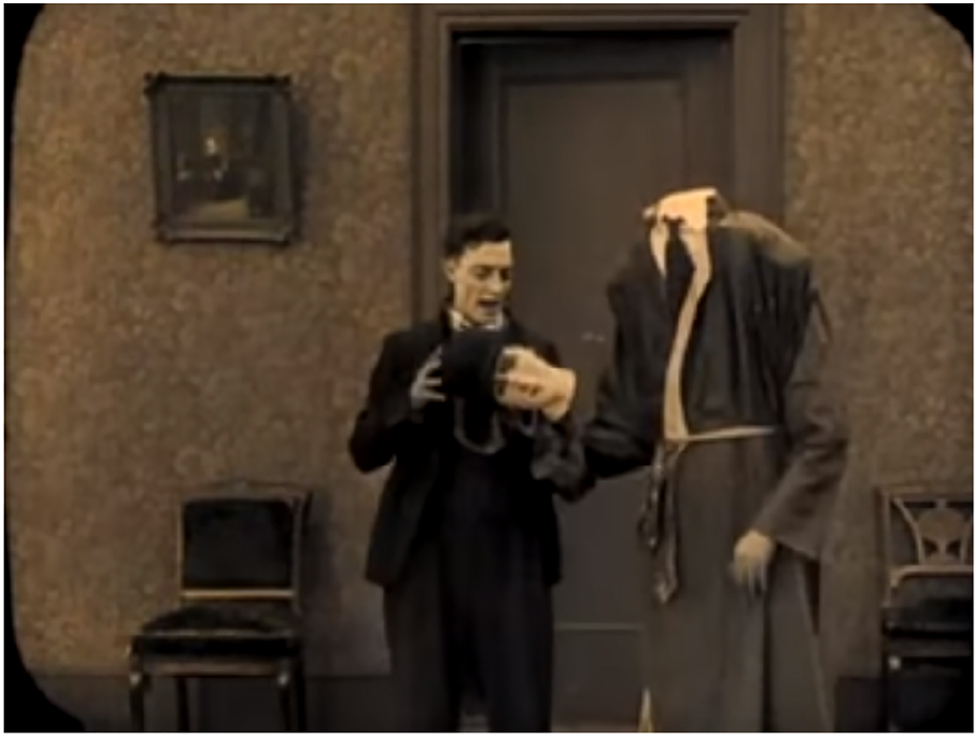

There is a general allusion in the Mingxing comedies to the “pie and chase” schema. In his influential essay on the American slapstick comedy of the 1910s and 1920s, Donald Crafton identifies a dialectical relationship between “the vertical domain of slapstick” (the arena of spectacle he dubs as “pie”) and “the horizontal domain of the story” (the arena of “chase”) (1995, 107). Put another way, the slapstick genre is a “gag-driven cinema” with “a simple plot which frames the gags” (ibid., 109). King of Comedy and Havoc manifestly display this structural attribute,[5] which was confirmed by a contemporary critic: “the story (shi 事) [of Havoc] is simple, but the gags (chuancha 穿插) are intriguing” (Shuang 1923). Framed by the meta-narrative of the chef’s silver dream, the horizontal development of Havoc is driven by three chase and fight sequences (in the kitchen, the park, and the bizarre theatre). Reading the advertising text, we can picture the slapstick visuality of these chases. The chef’s “grappling” (punao 撲閙) with the thief and “pratfalls” (pengdie 碰跌) in the theatre (Anonymous 1923b) can be visualized as the Chaplinesque “emphatic, violent, embarrassing gesture[s]” (Crafton 1995, 108) that one also sees in the hot water shop and all-night club scenes in Labourer’s Love. Non-narrative gag elements (“pie”) are highlighted in its advertisement in large, bold font: living fish, living crabs, living pigeons, living mice, a [double-headed] freak (lao huoguai 老活怪), a dwarf (da xiaonan 大小囝). Notably, the double-headed freak in the bizarre theatre may allude to The Haunted House, which features such a freak with a detachable head in a bizarre house (Figure 3), alongside a sliding staircase and a hot water scene (borrowed by Labourer’s Love).

The freak with a detachable head in The Haunted House.

This reading shows the dialectic interplay of gag and narrative in this early comedy, with multiple chases as the axis. King of Comedy also adopts the pie and chase structure, though the metaphor of chase takes the concrete form of an adventure. Opening with the arrival of Chaplin (played by Richard Bell, a Chaplin impersonator in a Shanghai entertainment hall), riding two cars racing through the Shanghai streets, the film firmly sets its tone as an “adventure,” as stressed in its textual trailer (Figure 1, feature 1, hereafter F1, and so on). Undoubtedly the narrative of “the copycat Chaplin ‘going native’” was a natural attraction to the Chinese audience; yet, as I will show, mutually informed and intertwined allusions from the Hollywood film repertoire and Chinese cultural sensibility exoticized the quotidian nativeness and provincialized Hollywood at once, producing a refreshing comic effect. We can identify the following visual allusions that Zhang and Zheng referenced in baking their Chinese “pies.”

The “Fatty”. The rotund figure is squarely in the idiom of Hollywood comedy. The “skinny” Chaplin often engages in amusing interactions with a “fatty,” as one can see in his early film The Masquerader (Keystone, 1914) and many others. Whereas the traditional Chinese theatre relies on a different set of stylistic conventions to establish the comic figure, Zhang Shichuan and Zheng Zhengqiu decisively incorporated an allusion to Hollywood, arranging a Chinese “fatty” to initiate a characteristic Chaplin-style slapstick scene (F2). The legacy of this seemingly insignificant character is the introduction of a new visual icon to the Chinese lexicon of laughter. Rotund comic actors such as Huang Junfu 黃君甫, Yin Xiucen 殷秀岑 (with Han Langen 韓蘭根 as Chinese Laurel and Hardy), and You Guangzhao 尤光照 shone on the Republican-era screen, and this comic cliché was even inherited by socialist-era film.[6]

The countryside and the sedan chair. The King of Comedy’s adventure in China mainly takes place in a village, and we should comprehend this setting in a web of cross-cultural allusions. A concomitant of industrial capitalism and urbanization, the early cinema generally preferred the setting of city than that of countryside. Within the Chaplin oeuvre, the 1919 Sunnyside is an exception, set in a little village with the Chaplin character (Charlie) as a “farm hand.” Typically, the rusticity of the countryside supplies humour, presented as a discordance vis-à-vis the sophistication of the city. While it is a “convenient” delight to have a frying pan in hand for a hen to lay an egg and to put milk in the tea straight from the cow, the bleating of a goat adds a note of discord to the civilized piano music Charlie is playing to please his sweetheart. Furthermore, the arrival of a “city chap” poses a palpable challenge to Charlie’s love interest and represents an allegorical antithesis to the countryside. The King of Comedy’s visit to the Chinese village is likely an allusion to the theme of Sunnyside, playing on the same city/countryside dichotomy to amuse predominantly urban-based film audiences in China. However, the Chinese art of allusion encompasses more layers of meaning situated distinctively in the context of colonial modernity.

On the one hand, one may argue that inviting this Charlie to the Chinese village is a self-orientalizing act, especially the use of the clichéd sedan chair (Figure 4). Coded as a symbol of the Oriental charm of quaintness, the sedan chair is one of the most popular objects associated with China in Western travel writings and photo albums of the period (e.g. Gamble 1988, 19). On the other hand, one may raise a counterargument: by exposing the ludicrousness of the culturally ignorant Chaplin, these mischief gags carry an undertone of nationalist and anti-imperialist critique. Seen through the theoretical prism of allusion, I argue, these designs are a playful blend of hybrid allusions to elicit a knowing smile and laugh. Therefore, the sedan chair is not only an Orientalist symbol, but also a cinematic device that facilitates the comic spectacle of showing Chaplin’s trademark shoes and physicality. Interestingly, the web of visual allusions had its uncanny resonance outside the silver screen. American scholar Sidney Gamble’s camera captured a funeral procession in 1920s Beijing, within which four bearers were carrying a paper automobile in the same way as carrying a sedan chair (Figure 5). This “visual spectacle” can be conceived as a real-life allusion to the car versus sedan chair scenes in King of Comedy, in the same playful spirit that fertilizes border-crossing imaginings.

A still from King of Comedy. Source: Zhang 2005, 14.

“Carrying Funeral Auto, Peking”, 1920s. Source: Gamble 1988, 125.

The baby and the water buffalo. The two imageries allude to the comedy genre conventions of world cinema. From the prototypical rascal in L’Arroseur Arrosé to the troublesome kid in the Harold Lloyd film I do (1921), from the hen, the cow, and the goat in Sunnyside to the Chaplin classic A Dog’s Life (1918), the silent film archive teems with kids and animals. In King of Comedy, the baby who is driving an oxcart and the water buffalo who listens to his command (F4) are not an action packed gag, but the “comic views,” another staple component of early comedy that Tom Gunning defines as “a mirthful scene of some subject that was considered humorous by the culture of the filmmakers” (1995, 93). What specific cultural ingredients are introduced to the universally humorous comic views of animals and kids in these Chinese films? The “living fish, living crabs, living pigeons, living mice” in Havoc is a good example for a further reading. The choice of crab, pigeon, and especially the hyperbolic mouse alludes to Orientalist stereotypes of Chinese culinary culture, reminiscent of such clichéd depictions of Chinese street food in Victorian travel writing: “There is abundance also of odds and ends of edibles that are nameless to us, and shall remain so—messes chiefly fried in nut-oil, tasting queer and smelling worse.” (Dukes 1885, 27) However, by translating a discriminatory “culinary melodrama” (Dupée 2004, 262) into laughable film language, the Chinese filmmakers relieved a tension through the invention of self-mocking, self-reflective humours.

Much the same can be said of the naughty child in The Kid. Competent in teasing the cop and getting free food from the rich by ruse, this kid is a typical early comedy hero of trickster. Although the “desire-driven, often antisocial figure” can be interpreted both negatively and positively (Karnick and Jenkins 1995, 76), in the Chinese context the allusive symbol of the kid conveys a social message of revolt against colonial authority (the cop) and power (the rich). This child in the forgotten one-reeler prefigured the immensely popular cartoon character Sanmao 三毛 of the 1930s and 1940s (Farquhar 1995). In short, the Mingxing filmmakers transformed tension-ridden social dramas into jocular farces through a culturally sensitive use of allusions in the tradition of the “nonanthropocentric tendency” and the “dehierarchization of the human figure in relation to the inanimate but lived environment, a materialist interplay between humans and things,” the features of early film celebrated by Walter Benjamin (Hansen 2012, 97).

The waterwheel. The scene in which Chaplin is entangled into a waterwheel, “like a frog dangling from a fishing rod” (F5), is another compelling illustration of the “materialist interplay between humans and things.” The visual metaphor of frog is an allusion to “animalism” associated with film comedians in early cinema (Karnick and Jenkins 1995, 76). The waterwheel is a localized “mechanical device,” which is a prevalent trope in silent cinema, dating back to the hose in L’Arroseur Arrosé, the famous sausage machine in Lumière’s Charcuterie Mecanique (Mechanical Butcher, 1896), and culminating in the canonical Modern Times (1936). As Tom Gunning observes, the key fascination of the mechanical lies in the “non-psychological action,” a pure revelation of “the way things work, the operational aesthetic” (1995, 99, 103). Moreover, these mechanical gags are often regarded as a comment on the absurdist nature of the industrial age (ibid.).

Mingxing reproduced the operational aesthetic masterfully in Labourer’s Love in the inkpot-swing[7] and the sliding staircase scenes (Dong 2008, 13–20). The waterwheel scene in King of Comedy possibly referenced Harold Lloyd’s 1921 film Never Weaken, from which Labourer’s Love “borrowed” the main storyline (ibid., 28).[8] While the first part of Never Weaken revolves around the hoax of turning people into patients, the second part unfolds a “thrill” comic gag about the Lloyd figure’s failed suicide attempts, with him ending up dangling from a tall building because the girder on a crane from a construction site accidentally lifts him into the air. The mechanical device of the girder as well as a vicarious bird’s-eye view of the modern American city crammed with skyscrapers and new constructions are unquestionably a comment on modernity and its perils. The Chinese art of allusion replaces the industrial-flavoured crane with the idyllic waterwheel, one of the traditional Chinese agricultural devices often marvelled at by foreign travellers of the period. A practical low-budget solution aside,[9] the waterwheel functions effectively as a self-deprecating humour (on the lack of sophistication compared to Lloyd’s high-budget crane gadget) and a proud showcase of native wisdom and inventiveness. Moreover, we may even argue that in contrast to the undertone of stress and anxiety associated with hypermodern Hollywood devices, the rustic Chinese mechanics display the harmonious interplay between humans and things, effecting a different affective reaction among the Chinese viewing public. If sophisticated gadgets and filming techniques bring a thrill, the simplicity of things induces equally gratifying laughter.

The scholar-gentry. A similar dynamic regarding toying with Chineseness is played out in Chaplin’s visit to the village scholar’s house, where he makes a string of silly mistakes (F6, Figure 6). These scenes seemingly allude to a sequence in Chaplin’s 1917 film The Adventurer. Charlie, the escaped convict, rescues Edna and her mother from the water, and is taken back to their house as a hero. He is feasted at a house party and gets involved in a succession of chases and dramas. Whereas class difference supplies the humour here, the Chinese story replaces this ingredient with cultural difference, a playful engagement with Orientalism in much the same way as in the previous gags. The village gentry represented the last preservation of Confucian culture and lifestyle in 1920s China, and the air of “authenticity” made Charlie’s cultural ignorance all the more ludicrous for a Chinese audience. There is no shortage of mutual cultural shock in contemporary anecdotal accounts of China-meets-West. For example, after an elaborate depiction of an exquisite Chinese feast and Chinese table manners, American missionary Isaac Headland comments (Headland 1914, 179):

It will be observed the Chinese do everything the opposite of what we do. They live on the under side of the world—their feet are in this direction and their heads in the opposite from our own, and so they seem to do everything contrary to what we do. […] At any rate, they take their fruit and nuts at the beginning of their meal and their soup at the end.

“Chaplin in the kitchen,” a still from King of Comedy. Source: Libailiu (Saturday), no. 181 (1922).

On the contrary, a Chinese gentleman observes (quoted in Brown 1904, 88):

You cannot civilize these foreign devils. They are beyond redemption. They will live for weeks and months without touching a mouthful of rice, but they eat the flesh of bullocks and sheep in enormous quantities. That is why they smell so badly; they smell like sheep themselves. […] Nor do they eat their meat cooked in small pieces. It is carried into the room in large chunks, often half raw, and they cut and slash and tear it apart. They eat with knives and prongs. It makes a civilized being perfectly nervous. One fancies himself in the presence of sword-swallowers.

The comedic materials the Mingxing filmmakers played with in the scholar-gentry scene are most likely this kind of remarks on opposing customs and habits. The culturally specific humour would certainly elicit an explosion of laughter.

The double. Slapstick and masquerade are deemed the defining characteristics of film comedy (Karnick and Jenkins 1995, 76). Allusions to the masquerade trope abound in the repertoire of early Chinese film. The finale of King of Comedy is a drama of the encounter between the real and fake Chaplins as a result of a local couple’s whimsical fantasy (F7). Probably out of the “spoiler” concern, the advertisement gives no further detail about what exactly happens, and no clue can be drawn from the two surviving stills (Figures 7 and 8). Showing a married couple in bed on the silver screen must have been frowned upon by a moralist, but remained a titillating attraction for the “plebeian” taste. Yet an outburst of laughter must have been evoked from the dramatic meeting of the true Charlie and his double. Chaplin played two roles in his 1921 film The Idle Class: Charlie the tramp and a rich man whose relationship with his wife is broken. The climax takes place at a masquerade ball, where Charlie sneaks in and causes comical confusions, until he meets his double, the husband. Although how this particular trope unfolds in King of Comedy remains unknown, this sequence is nevertheless a pioneer in Chinese film history, which would witness a lasting fascination with “the double” in the decades to come.[10] The Chinese allusion to the Chaplinesque cinematic lexicon sheds light on the possibility of “a universal language of mimetic transformation that would make mass culture an imaginative horizon for people trying to live a life in the war zones of modernization” (Hansen 2012, 64). Moreover, as film historians have agreed that the cultural legacy of slapstick comedy had seeped into the lineage of narrative film and other genres (Dong 2008, 33–34; Gunning 2006, 387), unearthing these forgotten origins help us better understand the historicity of Chinese film within a broader context.

“Real and fake Chaplins meet,” a still from King of Comedy. Source: Libailiu (Saturday), no. 183 (1922).

“A lazy couple,” a still in King of Comedy. Source: Banyue 2, no. 4 (1922).

3 Coda

Looking beyond Labourer’s Love, this article undertakes an “archaeological” study of the three lost films made by Mingxing in 1922, especially through positioning them in their intertextual, intermedial, and international networks. Apart from correcting misinformation and supplementing new data, this study posits two notions for a rethinking of the neglected genre of early Chinese comedy film. First, I argue that the ambient, bodily sensations of renao can be an alternative angle to understand the Chinese reception of comedy films in the tumultuous 1920s. My investigation demonstrates that film comedies were experienced not only among a programme of musical prologues, newsreels, and live performances, but also as a broader theatre experience that centred on the appeal of novel devices, hyper-stimulation, or “hot noise.” The therapeutic mechanism of thrill and laughter was deeply anchored in what Christopher Rea calls “the age of irreverence,” when “breaking rules, disobeying authorities, making mischief, mocking intransigent behaviour and thought, and pursuing fun all contributed to an atmosphere of cultural liberalization” (2016, 10). Moreover, this cacophonous Shanghai mediascape likewise gave rise to “a distinct socioeconomic and cultural formation that […] addressed itself to the masses, thus constituting a specifically modern form of subjectivity,” as Kracauer saw in the cinema and popular entertainments in Weimar Germany (Hansen 2012, 65).

Second, my reading of the advertising texts and other printed sources pinpoints an expanded vocabulary of what Zhang Zhen calls the “pidgin versions of a global cinematic vernacular à la Shanghaiese” (2005: 13–14). I borrow the Chinese poetic device of allusion to interpret the widespread references to Hollywood films in structural, narrative, and visual terms. Through the prism of allusion, the appropriation and re-production of Hollywood elements can be regarded as a means of adding authority to fledgling Chinese filmmaking, while at the same time complicating familiar topoi, symbols, and imageries in culturally sensitive ways. In this sense, deprecating these films as escapist, frivolous, and vulgar is deeply unfair; rather, the early Chinese filmmakers’ experimental spirit, masterful cleverness, and erudition in the realms of world cinema and native knowledge made the Chinese cinematic art of allusion a unique gem in the comic film tradition.

Last but not least, let me end this essay with Chaplin’s another two “encounters” with Shanghai. The first occasion is a virtual one, in his 1915 film entitled Shanghaied. Shanghai’s image as an alluring, mysterious city made its name into a debased verb in the English vocabulary, as Leo Ou-fan Lee elucidates: “to shanghai” is “to render insensible, as by drugs [read opium], and ship on a vessel wanting hands” or “to bring about the performance of an action by deception or force,” according to Webster’s Living Dictionary (Lee 1999, 4). Charlie the tramp is involved in helping a captain shanghai some seamen, but he in turn is shanghaied. The rest of the film takes place in the rolling ship—the cinematographic effect of the rolling is so true to life that makes the spectator vicariously seasick. Being “shanghaied” is being entangled in a world of plot, hazard, and intrigue. Vis-à-vis this Orientalist allusion to the city of Shanghai, Chaplin’s fictitious visit to Shanghai as devised by the Chinese filmmakers gains another layer of meaning. Interestingly, in 1936, Chaplin paid a real visit to Shanghai. Warmly welcomed by his Chinese fans, the aura of his comedic screen persona was replaced by celebrity glamour (Anonymous 1936). There was no adventure to the rustic China to make himself a laughing stock, and certainly no chance to be shanghaied. When the anxious Chinese fans were preoccupied with Chaplin’s impressions of China, we realize that the laughter induced by the fictitious Charlie on-screen was such a much-needed corrective to the anxiety of the age trapped in the cycle of humiliation and nationalism for the Chinese.

References

Anonymous. 1923a. “Zuowan xialing peike zhi yingpian ji yishu 昨晚夏令配克之影片及藝術 (The film at Olympic last night and its artistic achievement).” Shenbao January 27: 17.Search in Google Scholar

Anonymous. 1923b. “Zai zhi xialing peike zhi yingpian ji yishu 再志夏令配克之影片及藝術 (On the film at Olympic last night and its artistic achievement again).” Shenbao January 28: 17.Search in Google Scholar

Anonymous. 1936. “Shijie zhumu de yinmu xiaochou Zhuobielin dao Shanghai yipie 世界注目的銀幕小丑卓別林到上海一瞥 (The celebrated film comedian Chaplin’s visit to Shanghai).” Yingwu xinwen 影舞新闻. 2 (9): 7.Search in Google Scholar

Bao, Y. 2008. “The Problematics of Comedy: The New China Cinema and the Case of Lü Ban.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 20 (2): 185–228.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, A. J. 1904. New Forces in Old China: An Unwelcome but Inevitable Awakening. New York: F. H. Revell Co.Search in Google Scholar

Cheng, J. 程季華, S. Li 李少白 and Z. Xing 邢祖文, eds. 1963. Zhongguo dianying fazhanshi 中國電影發展史 (A History of the Development of Chinese Cinema). Beijing: Zhongguo dianying chubanshe.Search in Google Scholar

Crafton, D. 1995. “Gag, Spectacle and Narrative in Slapstick Comedy.” In Classical Hollywood Comedy, edited by K. B. Karnick and H. Jenkins, 106–19. New York, London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Dong, X. 2008. “The Laborer at Play: ‘Laborer’s Love’, The Operational Aesthetic, and the Comedy of Inventions.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 20 (2): 1–39.Search in Google Scholar

Dukes, E. J. 1885. Everyday Life in China; or, Scenes Along River and Road in Fuh-Kien. London: Religious Tract Society.Search in Google Scholar

Dupée, J. N. 2004. British Travel Writers in China: Writing Home to a British Public, 1890–1914. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press.Search in Google Scholar

Elsaesser, T. 1990. “General Introduction. Early Cinema: From Linear History to Mass Media Archaeology.” In Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative, edited by T. Elsaesser, 1–8. London: BFI Publishing.10.5040/9781838710170.0004Search in Google Scholar

Elsaesser, T. 2000. Weimar Cinema and After: Germany’s Historical Imaginary. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Farquhar, M. A. 1995. “Sanmao: Classic Cartoons and Chinese Popular Culture.” In Asian Popular Culture, edited by J. A. Lent, 139–58. Boulder: Westview Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gamble, S. 1988. Sidney D. Gamble’s China 1917–1932, Photographs of the Land and Its People. Washington D. C.: Alvin Rosenbaum Projects.Search in Google Scholar

Goldstein, J. 2003. “From Teahouse to Playhouse: Theaters as Social Texts in Early-Twentieth-Century China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 62 (3): 753–79, https://doi.org/10.2307/3591859.Search in Google Scholar

Gunning, T. 1995. “Crazy Machines in the Garden of Forking Paths: Mischief Gags and the Origins of American Film Comedy.” In Classical Hollywood Comedy, edited by K. B. Karnick and H. Jenkins, 87–105. New York, London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Gunning, T. 2006/1986. “A Cinema of Attraction(s): Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde.” In The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, edited by W. Strauven, 381–8. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hansen, M. 1991. Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hansen, M. 2012. Cinema and Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor W. Adorno. Berkeley: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Headland, I. T. 1914. Home Life in China. New York: Macmillan Co.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, X. 2014. Shanghai Filmmaking: Crossing Borders, Connecting to the Globe, 1922–1938. Leiden: Brill.Search in Google Scholar

Karnick, K. B., and H. Jenkins. 1995. “Introduction: Funny Stories.” In Classical Hollywood Comedy, edited by K. B. Karnick and H. Jenkins, 63–86. New York, London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Koszarski, R. 1990. An Evening’s Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928. Detroit: Charles Scribner’s Sons.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, L. O. 1999. Shanghai Modern: the Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930–1945. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674274716Search in Google Scholar

Li, J. 2020. “The Hot Noise of Open-Air Cinema.” Grey Room 81: 6–35, https://doi.org/10.1162/grey_a_00307.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, J. J. Y. 1962. The Art of Chinese Poetry. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rao, S. 饒曙光 2005. Zhongguo xiju dianying shi 中國喜劇電影史 (The History of Chinese Film Comedy). Beijing: Zhongguo dianying chubanshe.Search in Google Scholar

Rea, C. 2016. The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China. Oakland, California: University of California Press.10.1525/california/9780520283848.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Rea, C. 2021. Chinese Film Classics, 1922–1949. New York: Columbia University Press.10.7312/rea-18812Search in Google Scholar

Shuang, Q. 爽秋 1923. “Ji Mingxing erci chupin 記明星二次出品 (On Mingxing’s second output).” Shenbao February 5: 8.Search in Google Scholar

Xu, C. 徐恥痕. 1927. Zhongguo yingxi daguan 中國影戲大觀 (Film in China). Shanghai: Hezuo chubanshe.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Z. 1999. “Teahouse, Shadowplay, Bricolage: ‘Laborer’s Love’ and the Question of Early Chinese Cinema.” In Cinema and Urban Culture in Shanghai, 1922–1943, edited by Y. Zhang, 27–50. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Z. 2005. An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896–1937. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Filmography[11]

The Adventurer (Mutual, 1917)Search in Google Scholar

L’Arroseur Arrosé (The Sprinkler Sprinkled, Lumière Company, 1895)Search in Google Scholar

Charcuterie Mecanique (Mechanical Butcher, Lumière Company, 1896)Search in Google Scholar

Danao guai xichang 大鬧怪戲場 (Havoc in a Bizarre Theatre, Mingxing, 1922)Search in Google Scholar

A Dog’s Life (First National, 1918)Search in Google Scholar

The Haunted House (Metro, 1921)Search in Google Scholar

Huaji dawang you Hu ji 滑稽大王游滬記 (The King of Comedy Visits Shanghai, Mingxing, 1922)Search in Google Scholar

I do (Hal Roach, 1921)Search in Google Scholar

The Idle Class (First National, 1921)Search in Google Scholar

The Kid (First National, 1922)Search in Google Scholar

Laogong zhi aiqing 勞工之愛情 (Labourer’s Love, Mingxing, 1922)Search in Google Scholar

The Masquerader (Keystone, 1914)Search in Google Scholar

Modern Times (Chaplin-United Artists, 1936)Search in Google Scholar

Never Weaken (Rolin, 1921)Search in Google Scholar

Shanghaied (Essanay, 1915)Search in Google Scholar

Sunnyside (First National, 1919)Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Special Section: The Centenary of Labourer’s Love; Guest Editor: Huang Xuelei

- Editorial

- Editor’s Introduction

- Research Articles

- Alternative Readings of Labourer’s Love: The Shakespearean, Pan-Laborist, and Technological Uncanny

- Laborer’s Love: An Anthropotechnogenetic Mediation Between Cinematism and Animetism

- Zheng Zhegu and Performances in Early Chinese Film

- Beyond Labourer’s Love: Rethinking Early Chinese Film Comedy

- Articles outside Special Section

- Interview

- Detective Chinatown Pursues the “Tao” First: An Interview with Director Chen Sicheng

- Research Articles

- The Development and Challenges in Chinese Film Research over the Past Seventy Years and Future Trends

- Chinese Film in the 1930s: Potential Energy and “Left-Wing” Influence

- Study on the Phenomenon of Film Rereleasing in China in the Post-Pandemic Era: Cultural Significance and Industrial Mechanisms

- The “Collapsing Ending” as a Turning Point in Contemporary Cinematic Narrative

- “The age of Camille Is Gone!”: Youth Culture in Qiong Yao Films of the 1970s

- Heroes and Other Men: Masculinity and Nationalism in The Eight Hundred

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Special Section: The Centenary of Labourer’s Love; Guest Editor: Huang Xuelei

- Editorial

- Editor’s Introduction

- Research Articles

- Alternative Readings of Labourer’s Love: The Shakespearean, Pan-Laborist, and Technological Uncanny

- Laborer’s Love: An Anthropotechnogenetic Mediation Between Cinematism and Animetism

- Zheng Zhegu and Performances in Early Chinese Film

- Beyond Labourer’s Love: Rethinking Early Chinese Film Comedy

- Articles outside Special Section

- Interview

- Detective Chinatown Pursues the “Tao” First: An Interview with Director Chen Sicheng

- Research Articles

- The Development and Challenges in Chinese Film Research over the Past Seventy Years and Future Trends

- Chinese Film in the 1930s: Potential Energy and “Left-Wing” Influence

- Study on the Phenomenon of Film Rereleasing in China in the Post-Pandemic Era: Cultural Significance and Industrial Mechanisms

- The “Collapsing Ending” as a Turning Point in Contemporary Cinematic Narrative

- “The age of Camille Is Gone!”: Youth Culture in Qiong Yao Films of the 1970s

- Heroes and Other Men: Masculinity and Nationalism in The Eight Hundred