Abstract

We develop a model of international agreements to price a transboundry externality and provide a new heuristic to aid in interpreting negotiation behavior. Under conservative assumptions, a country’s net benefits will be positive under an efficient pollution price if its share of global damages is less than half its share of worldwide abatement costs. We solve for a permit allocation scheme consistent with that heuristic such that every region will have positive net benefits in an agreement to price the pollution externality at the globally efficient level. We then apply this framework to climate change using regional data from Integrated Assessment Models and test the feasibility of a global climate change treaty. The results indicate that several regions have positive net benefits from a globally efficient price on carbon, including Western Europe, South Asia (including India), and Latin America. We then solve for a permit allocation scheme that should produce worldwide agreement on a climate treaty. Using the same model, we show that differential carbon taxes aimed at producing universal agreement would produce tax rate differences of an order of magnitude. We also argue that shares of global GDP might be an appropriate proxy for exposure to climate damages and find that a global climate treaty would be cost-benefit justified for all countries without transfers when that assumption is used.

Appendix

Constant Damage Function

This appendix explores the impact of unilateral emissions reductions on the decision to enter a global climate treaty. Define a new emissions level  that is the global level of emissions under unilateral action. If each country reduces emissions to the domestically efficient level by emitting where the MDi=MACi, ignoring any spillover effects, then they will emit

that is the global level of emissions under unilateral action. If each country reduces emissions to the domestically efficient level by emitting where the MDi=MACi, ignoring any spillover effects, then they will emit  In this case, a country would never abate past its domestically efficient emissions level. Low-cost abatement opportunities in low-damage countries would not be employed, while relatively higher cost abatement in high-damage countries would be used.

In this case, a country would never abate past its domestically efficient emissions level. Low-cost abatement opportunities in low-damage countries would not be employed, while relatively higher cost abatement in high-damage countries would be used.

Assume (for the time being) that marginal damages are constant. Define a set of useful marginal damage levels:

| Domestic damages | Global damages | |

|---|---|---|

| Unilateral Action |  |  |

| Global Agreement | MDi(E*) | MDG(E*) |

| No Regulation | MDi(EM) | MDG(EM) |

The pollution tax rate in country i is simply the domestically efficient environmental tax, which (under the constant damage function assumption) is the same under unilateral or global action,  =MDi(E*)=MDi(EM). Similarly,

=MDi(E*)=MDi(EM). Similarly,  =MDG(E*)=MDG(EM). The benefits and costs of each type of emissions reductions are:

=MDG(E*)=MDG(EM). The benefits and costs of each type of emissions reductions are:

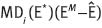

| Benefits under a global agreement | Costs under a global agreement | |||

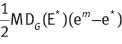

| MDi(E*)(EM–E*) |  | |||

| Benefits under unilateral action | Costs under unilateral action | |||

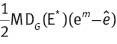

|  |

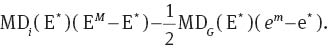

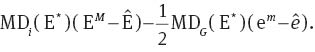

The net benefits of a global climate treaty for country i is:  The net benefits of unilateral action to reduce climate change for country i is:

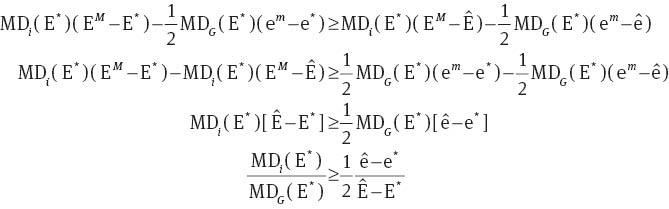

The net benefits of unilateral action to reduce climate change for country i is:  If the net benefits in country i of global action exceed the net benefits of unilateral action, then country i will join a global climate treaty. Comparing those net benefits we find:

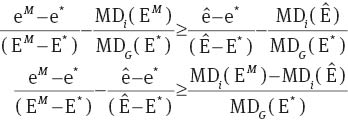

If the net benefits in country i of global action exceed the net benefits of unilateral action, then country i will join a global climate treaty. Comparing those net benefits we find:

A country will join a global agreement if its share of global damages exceeds half of its share of emissions reductions from the unilateral to the globally efficient level. This is a simple extension of the previous model, where emissions reductions are measured relative to the unilateral-action emissions level  rather than the unregulated emissions level (eM).

rather than the unregulated emissions level (eM).

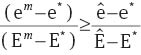

Ignoring the option for unilateral action will be a conservative assumption (in the sense that it will avoid the possibility of falsely identifying treaty signatories) if a region is more likely to agree to a global treaty when considering opportunity costs than when ignoring them. We can estimate when this will happen by comparing the condition for acceptance with and without opportunity cost. If

holds, then ignoring unilateral action is a conservative assumption.

Increasing Damage Function

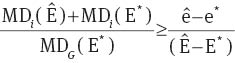

Using the same notation, consider the case of a linear but monotonically increasing damage function. For this case, we redefine the benefits of entering a global treaty as the benefits of moving the unilaterally efficient emissions level  Rearrange equation to describe the benefits of moving from the unilateral to globally efficient level of emissions as:

Rearrange equation to describe the benefits of moving from the unilateral to globally efficient level of emissions as:

This assumption will be conservative if

The left hand side of the inequality is positive if a country’s share of global abatement moving from no emissions reduction to the globally efficient level is greater than its share of abatement moving from the unilateral action outcome to the globally efficient level. The right hand side is the reduction in a country’s marginal damage between EM and  as a fraction of the global damages at the efficient level.

as a fraction of the global damages at the efficient level.

- 1

See Barrett (2005) for a summary of the literature.

- 2

We choose to focus on an efficient solution to a global externality, but our model is sufficiently flexible to allow for any level of reduction in the externality.

- 3

We abstract from the treaty negotiation process and compliance issues to focus on identifying potential free riders. See Barrett (2005) and Barrett and Stavins (2003) for analysis of those issues.

- 4

We put off the form this treaty takes (emissions taxes or permit schemes) till the next section.

- 5

These sub-global climate coalitions and the associated free-rider problem is important in the context of international climate change negotiations. See Nagashima and Dellink (2008). This assumption allows us to detect potential free riders by identifying nations with positive net benefits under a climate agreement. If those countries attempt to hold out of an agreement, they will be recognized as free riders, presumably reducing their bargaining power. This assumption allows us to focus on the cost-benefit justification of international environmental agreements while putting aside the issues of external or internal stability that have been debated in the literature.

- 6

Linear MAC curves are consistent with the metastudy conducted by Fischer (2006). Ellerman (1998) finds quadratic functions fit most regional MACs very well, but (with the exception of Brazil) the coefficients on the quadratic term are very small.

- 7

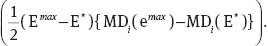

To see this simply, separate the area of benefits into two pieces, the rectangle below the optimal tax rate (Emax–E*)*MDi(E*) and the remaining area below the marginal damages curve and above the tax rate:

Sum these two areas and then combine terms.

Sum these two areas and then combine terms. - 8

This equality holds comes from the definition of the efficient tax, which equates global marginal damages with global marginal costs.

- 9

D’Aspremont, Jacquemin, Gabszewicz, and Weymark (1983) first describe coalition stability in collusive price cartels, but the International Environmental Agreement literature has adopted this terminology as well. See Barrett (1994) for an early paper that analyzes coalition stability using a similar cost-benefit-style framework.

- 10

See Chander and Tulkens (1992) for an early example of how international transfers can help form cooperative agreements and Rotillon and Tazdat (1996) for an example of the form those transfers might take.

- 11

Of course, much of the difficulty in creating efficient international environmental policy is due to the lack of a social planner.

- 12

See Eyckmans and Tulkens (2003), Carraro, Eyckmans, and Finus (2006, p. 3), and Carraro and Siniscalco (1993). This ensures that utility is transferable across countries, meaning that transfers are equally weighted. It would be straightforward to extend this analysis to unequal weights using a social welfare matrix that weights transfers. This approach ignores numerous equity and political issues with these transfers that are beyond the scope of this paper.

- 13

The construction of the marginal damage and marginal benefits curves ensure that the last unit of pollution abated generates the least net benefits. This means any reduction in the environmental tax will increase the average net benefits of emissions reductions.

- 14

See chapter 6 of Stern (2006) for descriptions of the issues and techniques used in Integrated Assessment Modeling and the current state of the IAM literature as well as Tol (2009) for a meta-analysis of recent models.

- 15

Detailed regional definitions for the WITCH model are detailed in Table 1.

- 16

Climate damages are a function of the stock of pollution, while emissions are directly related to abatement costs. We use the terms abatement and emissions avoided interchangeably.

- 17

It is important to note that these estimates are sensitive to the IAMs used to calculate marginal benefits and marginal damages. If these models are incorrect about the distribution of future damages from climate change, that error will be propagated in our estimates.

- 18

Because of the relatively consistent emissions reductions estimates, the results are not sensitive to using other plausible measures.

- 19

The assumption is conservative in the sense that constant marginal damages minimizes the total benefits of joining a climate change treaty to lower emissions to a given level. Any country that would agree to a climate change treaty under constant marginal damages would agree if its marginal damage function was increasing.

- 20

It should be noted that these estimates are based on the conservative assumptions laid out above. As the slope of the marginal damage curve increases, there are thresholds over which both countries become better off under a globally efficient climate treaty. If the damages curve for China is steep enough so that MDi(Emax) is 10.5 times greater than MD(E*), then China would be better off under a global climate change treaty even if its share of global damages is only 2.2%. For the US, the comparable figure is 3.9. If the unregulated level of damages exceeds the domestically efficient level by more than 3.9 times, then the US would be better off under a global climate treaty using even the smallest share of global benefits as the basis for our estimate.

- 21

See Eyckmans and Tulkens (2003), Carraro et al. (2006), and Germain, Toint, Tulkens, and de Zeeuw (2003), among many others.

- 22

For example, marginal damage curves could shift due to better scientific understanding of the damages of climate change or regime shifts due to increasing stock of pollutants. Similarly marginal abatement costs could shift due to technological breakthroughs in carbon capture and sequestration or geoengineering.

References

Ackerman, F., Stanton, E. A., & Bueno, R. (2010). Fat tails, exponents, extreme uncertainty: Simulating catastrophe in DICE. Ecological Economics 69(8), 1657–1665.10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.03.013Search in Google Scholar

Barrett, S. (1994). Self-enforcing international environmental agreements. Oxford Economic Papers 46, 878–894.10.1093/oep/46.Supplement_1.878Search in Google Scholar

Barrett, S. (2002). Consensus treaties. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) 158(4), 529–547.10.1628/0932456022975169Search in Google Scholar

Barrett, S. (2005). The theory of international environmental agreements. In K. G. Maler & J. R. Vincent (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Economics (Vol. 3 of Handbook of Environmental Economics, chapter 28, pp. 1457–1516). Amsterdam: Elsevier.Search in Google Scholar

Barrett, S., & Stavins, R. (2003). Increasing participation and compliance in international climate change agreements. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 3(4), 349–376.10.1023/B:INEA.0000005767.67689.28Search in Google Scholar

Bosetti, V., Carraro, C., De Cian, E., Massetti, E., & Tavoni, M. (2012). Incentives and stability of international climate coalitions: An integrated assessment. CEPR Discussion Papers 8821, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers.10.2139/ssrn.1991775Search in Google Scholar

Bosetti, V., De Cian, E., Sgobbi, A., & Tavoni, M. (2009). The 2008 WITCH Model: New model features and baseline. FEEM Working Paper Series (085).Search in Google Scholar

Bossetti, V., Carraro, C., Cian, E. D., Duval, R., Massetti, E., & Tavoni, M. (2009). The incentives to participate in and the stability of international climate coalitions: A game-theoretic approach using the WITCH model. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 702, OECD Publishing.10.2139/ssrn.1513294Search in Google Scholar

Bréchet, T., Gerard, F., & Tulkens, H. (2011). Efficiency vs. stability in climate coalitions: a conceptual and computational appraisal. Energy Journal 32(1), 49–76.Search in Google Scholar

Carraro, C., Eyckmans, J., & Finus, M. (2006). Optimal transfers and participation decisions in international environmental agreements. The Review of International Organizations 1, 379–396.10.1007/s11558-006-0162-5Search in Google Scholar

Carraro, C., & Siniscalco, D. (1993). Strategies for the international protection of the environment. Journal of Public Economics 52(3), 309–328.10.1016/0047-2727(93)90037-TSearch in Google Scholar

Chander, P., & Tulkens, H. (1992). Theoretical foundations of negotiations and cost sharing in transfrontier pollution problems. European Economic Review 36(2–3), 388–399.10.1016/0014-2921(92)90095-ESearch in Google Scholar

D’Aspremont, C., Jacquemin, A., Gabszewicz, J. J., & Weymark, J. A. (1983). On the stability of collusive price leadership. The Canadian Journal of Economics 16(1), 17–25.10.2307/134972Search in Google Scholar

Ellerman, A. Denny., & Decaux, A. (1998). Analysis of post-Kyoto CO2 emissions trading using marginal abatement curves, Working Paper Series 40, MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.Search in Google Scholar

Eyckmans, J., & Tulkens, H. (2003). Simulating coalitionally stable burden sharing agreements for the climate change problem. Resource and Energy Economics 25(4), 299–327.10.1016/S0928-7655(03)00041-1Search in Google Scholar

Fawcett, A. A. (2009). Waxman-Markey discussion draft preliminary analysis: EPA preliminary analysis of the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009, Technical report.Search in Google Scholar

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Atmospheric Programs.Search in Google Scholar

Finus, M., Altamirano-Cabrera, J.-C., & Van Ierland, E. (2005). The effect of membership rules and voting schemes on the success of international climate agreements. Public Choice 125, 95–127.10.1007/s11127-005-3411-xSearch in Google Scholar

Fischer, Carolyn, & Morgenstern, R. (2006). Carbon abatement costs: Why the wide range of estimates?. Energy Journal 27(2), 73–86.10.5547/ISSN0195-6574-EJ-Vol27-No2-5Search in Google Scholar

Germain, M., Toint, P., Tulkens, H., & de Zeeuw, A. (2003). Transfers to sustain dynamic core-theoretic cooperation in international stock pollutant control. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 28(1), 79–99.10.1016/S0165-1889(02)00107-0Search in Google Scholar

Nagashima, M., & Dellink, R. (2008). Technology spillovers and stability of international climate coalitions. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 8(4), 343–365.10.1007/s10784-008-9079-1Search in Google Scholar

Nordhaus, W., & Boyer, J. (2000). Warming the World: Economics Models of Global Warming, Boston, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.10.7551/mitpress/7158.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Nordhaus, W. D. (2008). A question of balance: Weighing the options on global warming policies. Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rotillon, G., & Tazdat, T. (1996). International bargaining in the presence of global environmental change. Environmental & Resource Economics 8(3), 293–314.Search in Google Scholar

Stern, N. (2006). The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Tol, R. S. (2012). On the uncertainty about the total economic impact of climate change. Environmental and Resource Economics 53(1), 97–116.10.1007/s10640-012-9549-3Search in Google Scholar

Tol, R. S. J. (2005). The marginal damage costs of carbon dioxide emissions: an assessment of the uncertainties. Energy Policy 33(16), 2064–2074.10.1016/j.enpol.2004.04.002Search in Google Scholar

Tol, R. S. J. (2009). The economic effects of climate change. Journal of Economic Perspectives 23(2), 29–51.10.1257/jep.23.2.29Search in Google Scholar

Weitzman, M. L. (2009). On modeling and interpreting the economics of catastrophic climate change. The Review of Economics and Statistics 91(1), 1–19.10.1162/rest.91.1.1Search in Google Scholar

Weitzman, M. L. (2010). What is the “damages function” for global warming and what difference might it make?. Climate Change Economics 1(01), 57–69.10.1142/S2010007810000042Search in Google Scholar

©2013 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Regional variation, holdouts, and climate treaty negotiations

- A cost-benefit framework for evaluating conditional cash-transfer programs

- A cost-benefit analysis: implementing temporary disability insurance in Washington State

- Cost-benefit analyses of sprinklers in nursing homes for elderly

- The value of a statistical life: some clarifications and puzzles

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Regional variation, holdouts, and climate treaty negotiations

- A cost-benefit framework for evaluating conditional cash-transfer programs

- A cost-benefit analysis: implementing temporary disability insurance in Washington State

- Cost-benefit analyses of sprinklers in nursing homes for elderly

- The value of a statistical life: some clarifications and puzzles