Abstract

The COVID-19 Pandemic created a need for a vaccine that would need to be rapidly created, tested and approved in order to reduce the pandemic’s tremendous impact on human life and the economy. This article discusses the vaccine development process as well as Operation Warp Speed, the United States plan for emergency vaccine development in a pandemic situation. Written before the approval of the currently available COVID-19 vaccines, this article also discusses the implications of a speedier vaccine development process as well as recommendations to the standard process.

1 Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, which causes the disease COVID-19, has developed into a pandemic that has tested the United States in many ways: from stretching healthcare systems to their limits, to revealing questions on the extent of governmental authority over even the most mundane aspects of everyday life, and having to deal with the grief of human and economic loss. With no cure or current vaccines for COVID-19, attention has focused on the need to develop a vaccine in record time to reel in the pandemic’s impact and reduce loss of life. However, while current programs for expediting vaccines might be able to speed up vaccine development by a few years, they would not be adequate to facilitate the development of a vaccine in a matter of months. In response, on May 15, 2020, the White House announced Operation Warp Speed (OWS), a national program to accelerate the development, manufacturing, and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics.[1]

2 Background: The Cutter Incident

Before talking about the vaccine approval process, it is important to understand why it is as rigorous and lengthy as it is. In 1952, polio was running rampant in the United States with over 59,000 cases reported.[2] Jonas Salk had developed a vaccine that consisted of an inactive strain of the poliovirus, inactivation occurring with a formaldehyde treatment.[3] By 1954, Salk had developed a 55 page protocol detailing the vaccine’s production.[4] However, the protocol was eventually reduced to just five pages during mass production.[5] At this point, the vaccine was then moved on to licensing.[6] The licensing process took a mere 3 h.[7] In 1955, millions of doses of the polio vaccine, manufactured by Cutter Laboratories, were sent across the United States.[8] However, Salk’s original protocol was not followed in manufacturing which resulted in a live virus strain in the doses.[9] This caused over 220,000 polio infections paralyzing 164 people and 10 succumbing to the disease.[10] The fault essentially lay in the lack of regulations requiring that vaccine manufactures follow Salk’s original protocol.[11] This incident emphasizes the need for regulation, and eventually led to the creation of a better system for overseeing vaccine development.[12]

3 The Vaccine Approval Process

The Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), part of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), is the federal agency that deals with the vaccine approval process.[13] Within CBER, the Office of Vaccine Research and Review, the Office of Compliance and Biologics Quality, and the Office of Biostatistics and Epidemiology are the offices that handle vaccine review.[14] CBER’s legal authority to regulate vaccines is derived from § 351 of the Public Health Service Act and several sections within Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act.[15]

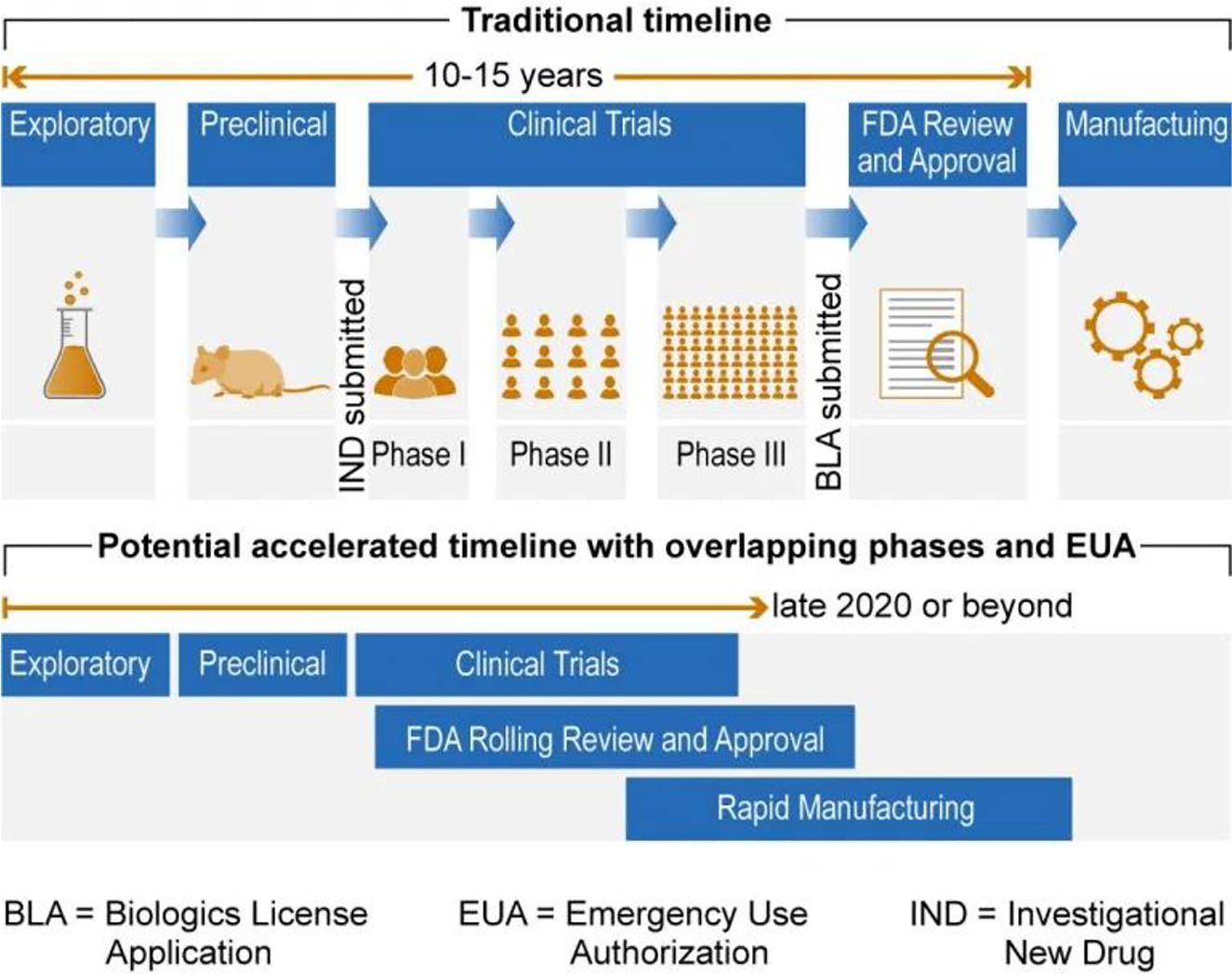

The process for vaccine development and approval can be broken down into the following steps: Exploratory stage, Preclinical Trials, Clinical Trials, and FDA Review and Approval.[16] Typically, the entire process will take around 10 to 15 years.[17] Additionally, the FDA provides nonbinding guidance documents to assist in the vaccine development and approval process (Figure 1).[18]

Vaccine approval process.23

3.1 Exploratory Stage

The exploratory stage typically consists of development of vaccine candidates and in vitro testing.[19] Here, researchers are identifying natural or synthetic molecules that may show promise in developing immunogenicity.[20] This stage’s length will vary, but will generally take several years.[21] Once a vaccine candidate has been identified and tested through various lab methods, the process will progress to the preclinical trial stage.[22]

3.2 Preclinical Stage

In this stage, more experimentation and animal testing is done to ensure enough data is gathered to file an Investigational New Drug Application (IND).[23] [24] While it is not necessary to notify the FDA of preclinical testing at this point, the preclinical testing is governed by FDA regulations known as the Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) regulations.[25] The GLP regulations set out minimum standards for laboratory work and facilities for nonclinical studies that will be used to support an IND.[26] Areas governed by the GLP include personnel, facilities, equipment, operating procedures, animal care, study protocols, record keeping, and reporting.[27] The GLP regulations also allow the FDA to inspect the facilities and records to ensure compliance.[28] If the regulations are not followed, the FDA can impose sanctions, disqualify testing facilities, disregard preclinical studies, and may even withdraw the application’s approval.[29]

3.3 Clinical Trial Stage

After preclinical testing is completed, the next step is to conduct clinical trials in humans.[30] However, to be allowed to test vaccines in humans, the sponsor must apply for an IND. The IND application includes data from preclinical studies and lays out the sponsor’s plan for conducting the clinical trials.[31] The FDA will evaluate the data based on how sound it is, whether the methods used were adequate, and whether the vaccine is safe enough for use in humans subjects.[32] If the FDA finds issues with the application, they may issue a clinical hold to prevent the sponsor from beginning clinical test trials.[33] If the FDA does not object to the IND within 30 days of submitting the application, the sponsor may begin clinical tests.[34]

Once the IND has been approved, the clinical testing of the vaccine may begin.[35] The clinical testing stage is generally split into three phases called Phase 1, Phase 2, and Phase 3, respectively.[36] These phases may overlap, and Phase 1 and 2 trials may have to be repeated as new data becomes available.[37] Phase 1 trials are typically designed to determine the safety and tolerability of the vaccine to obtain preliminary immunogenicity data.[38] These trials are conducted with around 20 to 80 human subjects that are closely monitored for adverse effects.[39] Phase 2 trials are used to further evaluate immunogenicity, provide rates of common adverse effects, and obtain data needed to design Phase 3 studies.[40] Phase 2 trials are conducted with several hundred human subjects.[41] Phase 3 trials are large in scale and can involve several thousand human subjects.[42] The goal of Phase 3 trials is to obtain critical safety and efficacy data needed to support licensure.[43] Efficacy should be shown in randomized, double-blind, and well-controlled studies that may involve up to tens of thousands of human subjects.[44]

3.4 FDA Review and Approval

Once clinical test trials are completed, the next step is to file a Biologics License Application (BLA).[45] A BLA is a request to introduce a biological product to interstate commerce.[46] The BLA will contain data from clinical and nonclinical studies that show that the vaccine meets the requirements for safety, purity, and potency.[47] The BLA will also contain information regarding manufacturing, compliance of GLP regulations, data regarding the stability of the vaccine through a dating period, samples representing the vaccine, and information regarding the equipment and facilities used for manufacturing.[48] A CBER review team will review the BLA and determine if the vaccine is safe and effective.[49] The review team may also request that the sponsor present the data to the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC).[50] The VRBPAC is an FDA advisory committee that is made up of scientific experts and clinicians, consumer representatives, and nonvoting members from industry.[51] The role of the VRBPAC is to evaluate the clinical data and comment on the data’s adequacy.[52] CBER’s decisions are strongly influenced by the VRBPAC’s findings.[53]

4 FDA Expedited Programs

If there is an unmet medical need or there is a serious or life-threatening condition, the FDA may expedite the approval of a drug or biologic if the new treatment is superior to existing available therapies.[54] A serious condition or disease is defined as:

A disease or condition associated with morbidity that has substantial impact on day-to-day functioning. Short-lived and self-limiting morbidity will usually not be sufficient, but the morbidity need not be irreversible, provided it is persistent or recurrent. Whether a disease or condition is serious is a matter of clinical judgment, based on its impact on such factors as survival, day-to-day functioning, or the likelihood that the disease, if left untreated, will progress from a less severe condition to a more serious one.[55]

A life-threatening condition or disease is defined as “[a] stage of disease in which there is reasonable likelihood that death will occur within a matter of months or in which premature death is likely without early treatment.”[56] Before the COVID-19 Pandemic, the FDA had several established tracks for expediting review and approval.[57] These tracks are: Fast Track designation, Breakthrough Therapy designation, Accelerated Approval, and Priority Review.[58]

4.1 Fast Track Designation

Fast Track designation was implemented by Congress in the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 because they were concerned about the length of time that a new drug or therapy may take to develop and review, particularly in emergencies.[59] A sponsor may request Fast Track designation if the new therapy demonstrates the potential to address unmet medical needs or a serious condition.[60] The amount of data needed will depend on the stage of development.[61] If the therapy is in an early stage of development, then evidence of activity in nonclinical models, mechanistic rationale, or pharmacological data may be considered to show the therapy’s potential.[62]

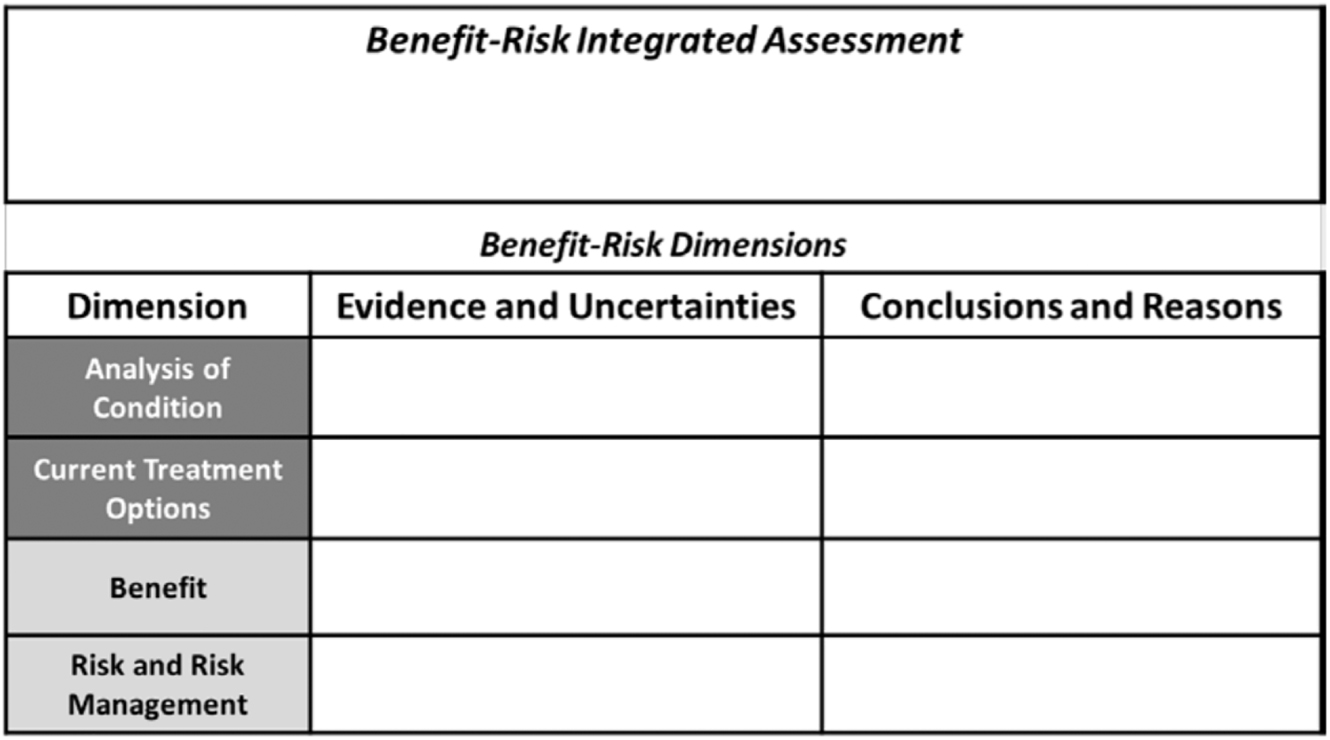

Fast Track Designation allows or more frequent opportunities of interaction with the review team of the fast track therapy.[63] These interactions could include meetings with the FDA, pre-IND meetings, end of Phase 1 meetings, end of Phase 2 meetings, meetings to discuss study design, meetings regarding the safety data required to support approval, etc.[64] If the FDA determines that the fast track product may be effective, then the Fast Track designation allows for rolling review of portions of the marketing application before the sponsor completes and submits the BLA.[65] The FDA will analyze the protect’s benefit and safety using a qualitative benefit- risk assessment pictured below (Figure 2).[66] [67]

FDA benefit-risk assessment framework.67

There is a question however, of whether Fast Track designation would be “speedy” enough for a situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where a vaccine may have to be developed and approved in a matter of months. The issue would lie with the fact that while Phase 3 clinical trials may not be necessary at the time of BLA approval, Phase 1 trials and at least one Phase 2 trial will be necessary for the therapy to be approved.[68] While this may drastically speed up the timeline when compared to the traditional process, approval may still take too much time in scenarios such as a pandemic involving an easily transmittable disease.

4.2 Breakthrough Therapy Designation

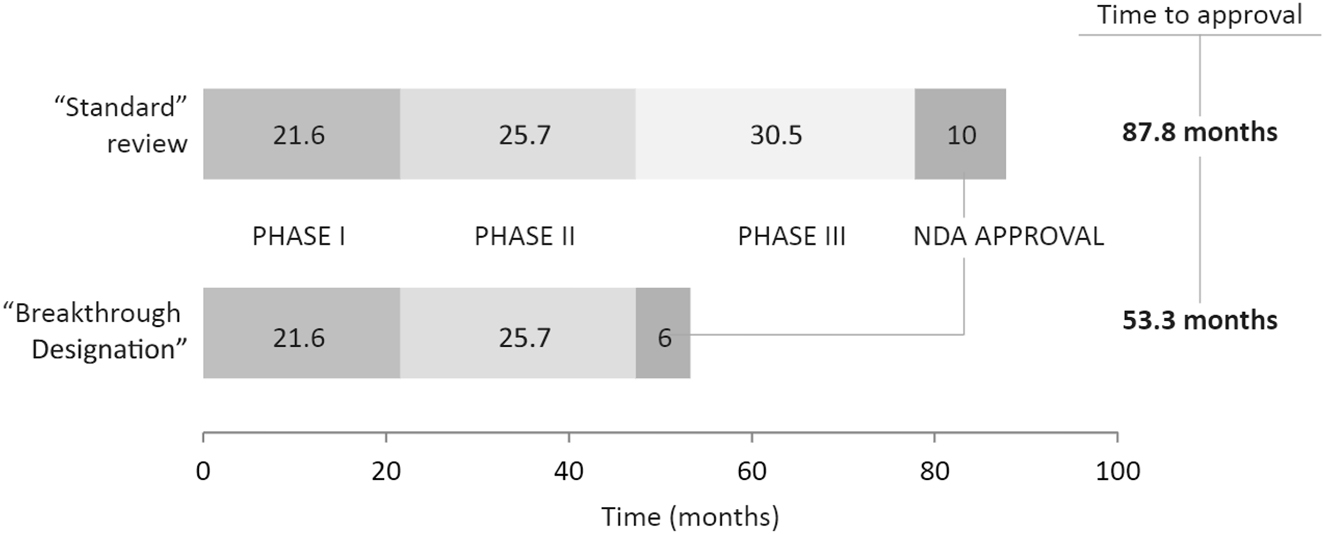

Breakthrough Therapy designation was created by the Food and Drug Administration and Safety and Innovation Act of 2012 as another method of decreasing the time for drug development and review.[69] A sponsor must show substantial improvement over existing therapies in one clinically significant “endpoint” during early development in order to request breakthrough therapy designation.[70] A clinically significant end point is “an endpoint that measures an effect on irreversible morbidity or mortality (IMM) or on symptoms that represent serious consequences of the disease.”[71] This designation requires preliminary clinical evidence; however, the standard for reviewing the evidence is not as high as in the traditional process.[72] In this case, preliminary clinical evidence is defined as “evidence that is sufficient to indicate that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement in effectiveness or safety over available therapies, but in most cases is not sufficient to establish safety and effectiveness for purposes of approval.”[73] While not as stringent of a standard, the FDA will still focus on ensuring that the therapy is safe and has the appropriate level of efficacy.[74] If the FDA notes that subsequent data no longer shows the therapy as providing a substantial improvement, then the FDA may withdraw the designation (Figure 3).[75]

Breakthrough therapy designation process/timeline.76

Achieving Breakthrough Therapy designation allows the sponsor to begin receiving advice from the FDA as early as Phase 1 of clinical trials as well as guidance from a proactive collaborative team of reviewers.[76] [77] In addition, the designation allows for rolling review of marketing application as well as assistance in obtaining priority review at the time the BLA is submitted.[78] While the Breakthrough Therapy Designation may decrease the time it would normally take to get a therapy approved, timelines show that the approval process is cut down by a couple of years at most, resulting in a process that would still take several years to complete.[79]

4.3 Accelerated Approval

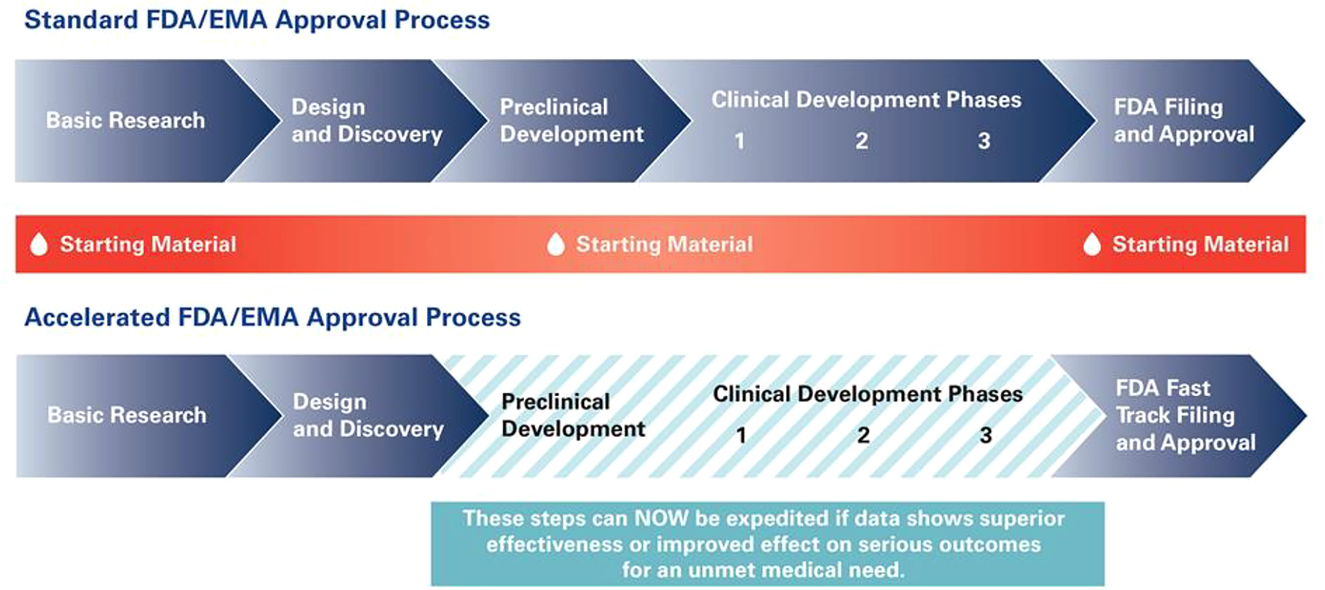

Accelerated approval was implemented under the original Prescription Drug User Fee Act of 1992 (PDUFA) and was a response to criticism of the lengthy approval process timeline for drugs and biologics.[80] Accelerated Approval is used for circumstances where the approval process for a promising therapy should be expedited so that patients with serious conditions may access the treatment.[81] Accelerated Approval is based on a surrogate endpoint which is a sort of marker such as “a laboratory measurement, radiographic image, physical sign or other measure that is thought to predict clinical benefit, but is not itself a measure of clinical benefit.”[82] It may also be based on intermediate clinical endpoints which are measurements of therapeutic effect that can be measured earlier than an effect on IMM and is considered to be reasonably likely to predict the drug’s effect on IMM or other clinical benefit.[83] Whether the endpoint would reasonable predict clinical benefit depends of the biological plausibility of the relationship between the endpoint, the disease, the desired effect, and the evidence to support the relationship (Figure 4).[84] [85]

Accelerated approval process/timeline.85

4.4 Priority Review

In addition to Accelerated Review, the PDUFA also established a two tiered system of review times consisting of Standard Review and Priority Review.[86] If an application is designated under Priority Review, then the FDA’s must take action on the application within six months instead of 10 months as is with Standard Review.[87] An application will receive this designation if the therapy treats a serious condition and would provide a significant improvement in safety or effectiveness.[88] Once the designation has been given, attention and resources will be directed towards the speedy evaluation of the therapy.[89]

A significant improvement in safety or effectiveness against a serious condition can be shown through evidence of increased effectiveness in treatments, prevention or diagnosis of the condition, the elimination or substantial reduction of treatment-limiting adverse reaction, the documented enhancement of patient compliance that would lead to improvement in serious outcomes, or evidence of safety, and effectiveness in a new subpopulation.[90]

4.5 Fast Enough?

While the programs the FDA has in place for expediting drugs and vaccines may help to get a new therapy out to the public a few years sooner that initially expected, an unprecedented event, such as a pandemic, may require a much quicker timeline than the current programs would be able to provide, even if working in conjunction with one another. In 2001, the European Commission held a conference in Brussels called “Pandemic Preparedness in the Community” in which the commission concluded that the next pandemic was imminent, and that the world was not prepared for it.[91] Vaccine availability being one of the factors for that conclusion.[92]

5 Operation Warp Speed Overview

On January 31, 2020, the Secretary of Health and Human Services declared a public health emergency due to confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States pursuant to authority under Section 319 of the Public Health Service Act.[93] On March 13, 2020, President Donald J. Trump declared the COVID-19 outbreak a national emergency.[94] OWS was announced on May 15, 2020, as public-private partnership between the government and the private sector meant to facilitate the development, manufacturing, and distribution of COVID-19 countermeasures, which includes vaccines.[95] Federal agencies involved with this partnership include the United Staes Department of Defense and the Department of Health and Human Services, which includes the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA).[96] Initial funding for OWS was directed by Congress through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Securities Act (CARES Act) that consisted of almost $10 billion, of which $6.5 billion was designated for countermeasure development through BARDA and $3 billion designated for NIH research.[97] Specific authority is derived through the 21st Century Cures Act, which authorizes BARDA to establish public-private partnerships to foster and accelerate medical countermeasures, such as vaccine development.

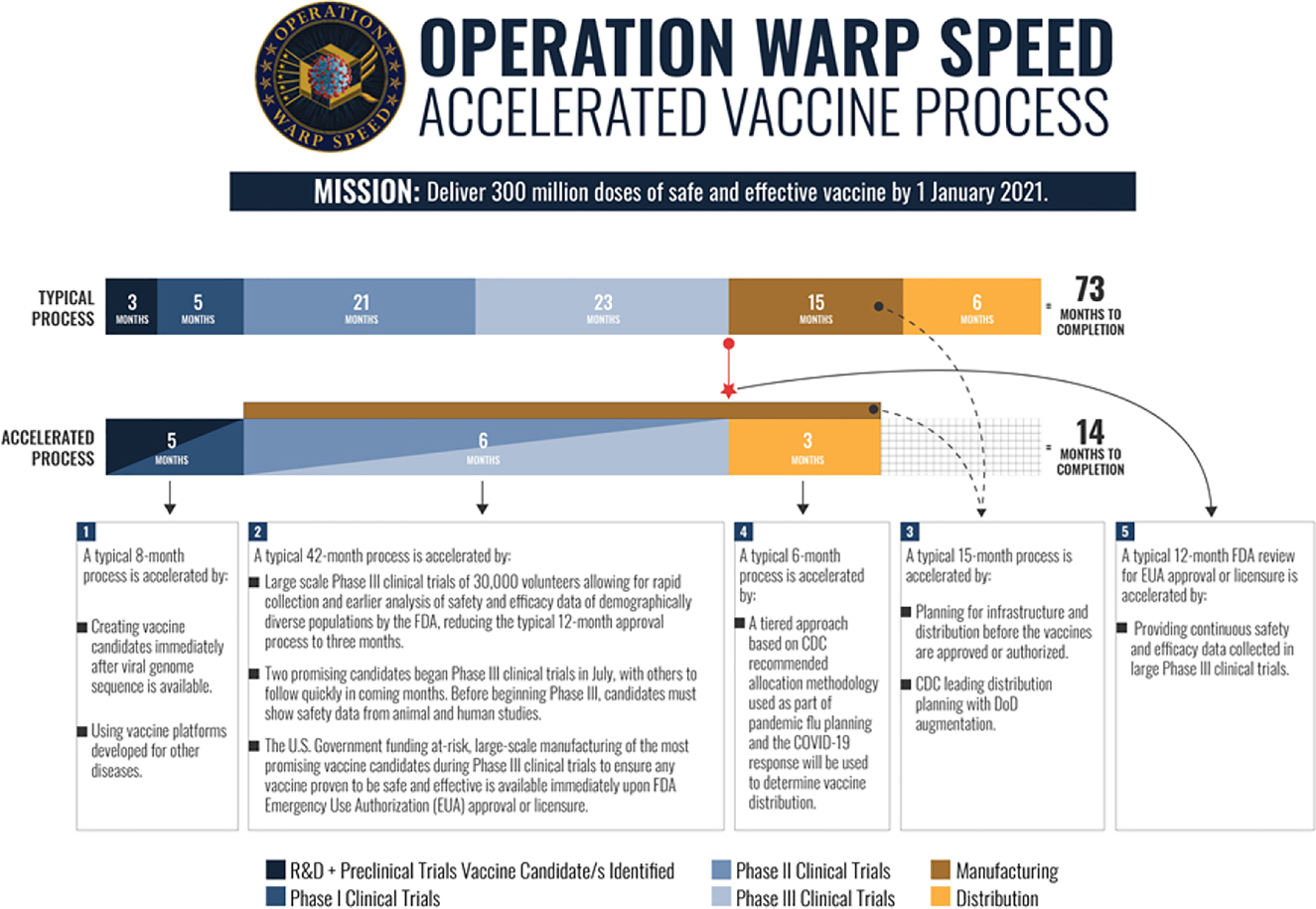

The objective of OWS is to deliver millions of doses of a safe COVID-19 vaccine that is approved and authorized by the FDA to the United States populace towards the end of 2020.[98] The way OWS works to achieve this goal is by harmonizing the various steps of the vaccine approval process and providing selected sponsors with guidance along all steps.[99] Governmental involvement through the process ensures that there are no “technical, logistic, or financial hurdles hindering vaccine development or deployment.”[100] The first announcement of selected vaccines occurred about a month after the announcement of OWS with more vaccine candidate selections being announced thereafter (Figure 5).[101]

Operation warp speed process.102

The first candidates were selected based on certain criteria.[102] [103] Candidates must have robust preclinical safety or early-stage clinical trial data that supports their potential for clinical safety and efficacy; they must have the potential (with accelerated support) to enter large Phase 3 field-efficacy trials by summer or fall of 2020, and they must deliver efficacy outcomes by the end of 2020/beginning 2021.[104] To be considered, the candidate must be based on a vaccine platform technology that allows for quick and effective manufacturing, and the sponsors must show the industrial process scalability, yields, and consistency that is necessary to produce 100 million doses by mid 2021.[105] The candidate must also use one of the four vaccine platform technologies deemed most likely to be safe and effective.[106] These technologies include the mRNA platform, the replication defective live vector platform, the recombinant subunit adjuvanted protein platform, and the attenuated replication live vector platform.[107]

OWS’s strategy is focused on three principles.[108] The first principle deals with developing a diverse candidate group of two candidates per technology platform to mitigate the risk of failure by allowing the possible selection of different vaccine platforms for different subpopulations, if necessary.[109] The second principle involves the acceleration of the development and approval process by running some of the steps in parallel, leading up to large Phase 3 trials (30,000 to 50,000 human subjects).[110] These Phase 3 trials can be prepared for while Phase 1 and 2 trials are being conducted due to the financial investment from OWS, meaning that Phase 3 trials can begin as soon as the FDA approves the IND for the candidate.[111] Similarly, the third principle focuses on developing the manufacturing and scale up processes for the candidate vaccine while the preclinic or early clinical stages are in progress so that the manufacturing processes are ready for FDA inspection at the end of Phase 3 trials.[112] A goal of OWS is to have vaccine doses manufactured and stockpiled so that they can be distributed immediately once the vaccine has been FDA approved.[113]

In June 2020, the FDA released a guidance titled “Development and Licensure of Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19: Guidance for Industry” which contains nonbinding recommendations for development and testing of vaccine candidates.[114] This guidance sets forth key considerations to satisfy regulatory requirements for IND regulations in 21 C.F.R. 312 and licensing regulations in 21 C.F.R. 601.[115] While speed is important, the vaccine candidate must still meet statutory and regulatory requirements for vaccine development and approval set out in Section 351(a) of the Public Health Service Act.[116] Development and manufacturing must be in accordance with the good manufacturing practice.[117] Additionally, vaccine development may be accelerated due to knowledge from similar products manufactured with a same well-characterized platform technology.[118] Clinical studies may be completed in discreet phases with separate studies or may be done using a more seamless method, however, data summaries must be submitted at each development milestone for FDA review.[119]

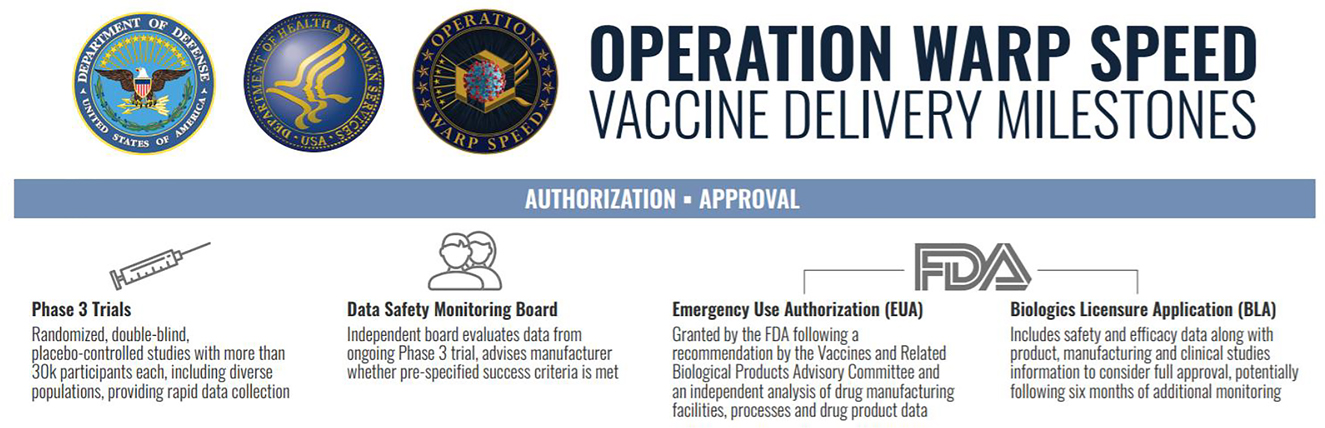

When acceptable preclinical data is collected, early phase studies involving 10–100 healthy subjects may be conducted.[120] Sponsors should evaluate clinical safety immunogenicity data for each dose and age-group before progressing clinical development to involve larger groups and groups with higher risks of severe COVID-19.[121] Data should involve the potential risk for developing Vaccine-associated Enhanced Respiratory Disease, although thorough post vaccination challenge studies in animal models are recommended to address these risks.[122] To meet BLA approval standards, late phase clinical trials will need to show vaccine efficacy in trials involving thousands of participants, which should include subjects with medical comorbidities to assess protection against severe COVID-19.[123] Additionally, clinical testing should encourage enrollment of diverse populations, particularly those most affected by COVID-19.[124] The FDA may also require post marketing studies of trials to examine potential or known serious risks.[125] After the candidate has met the criteria set forth and has been “approved” by the FDA, the sponsor may then apply for an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).[126]

5.1 FDA Emergency Use Authorization

EUA allows for temporary FDA authorization for unapproved emergency uses of a medical product.[127] The Pandemic and All-Hazards Reauthorization Act of 2013 (PAHPRA) added sections that describe the use of EUAs in response to a chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CRBN) agent.[128] When the Secretary of Health and Human Services issues an emergency declaration regarding a CRBN, EUA may begin to take place.[129] To be granted EUA, the FDA must making the following findings: The CBRN threat is able to cause serious or life-threatening disease or condition; the EUA candidate may be effective to prevent, diagnose, or treat the condition; the known and potential benefits of the product seeking the EUA outweigh the known and potential risks; and there are no adequate, approved, and available alternative to the product to be authorized.[130]

Previously, EUAs were established for the Zika Virus, Ebola Virus, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), H1N1 Influenza, and Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (AVA).[131] The FDA may issue EUAs for as long as the PAHPRA emergency declaration is active.[132] The EUA will be considered terminated once the HHS Secretary has declared that the PAHPRA emergency has ended, the FDA approves a marketing application for the EUA which renders it moot, or the FDA revokes the EUA (Figure 6).[133]

Emergency use authorization with OWS.134

In October 2020, the FDA published a nonbinding guidance document called Emergency Use Authorization for Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19: Guidance for Industry.[134] [135] Once a vaccine candidate has been reviewed by the FDA, the sponsor may then request an EUA for the vaccine.[136] The issuance of the EUA would hinge on a determination by the FDA on whether the vaccine’s benefits outweigh the risks based on the data collected from at least one well-designed Phase 3 trial.[137] The data would have to demonstrate, in a clear and compelling manner, that the vaccine is safe and effective.[138] Additionally, the sponsor would have to show an adequate plan for the collection of safety data of people vaccinated under the EUA, as well as show a plan for ongoing clinical trials to assess long-term safety and efficacy.[139] At this point, a BLA has not been issue, therefore, the sponsor would also have to apply for the BLA.[140] As of November 18, 2020, there are currently no vaccines that have been issued an EUA, but there are some vaccine candidates reporting satisfactory safety and efficacy data that may be applying soon.[141]

6 Liability Issues

The most obvious differences between the standard vaccine approval process and OWS are the timelines involved and the use of EUAs. However, another difference lies in the immunity from liability for manufacturers of the vaccines. For vaccines approved through the standard process, Under the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act (NCVIA), manufacturers will generally not be liable for in any civil action for damages associated with the administration of the vaccine unless it is shown by clear and convincing evidence that the manufacturer failed to exercise due care.[142] This created significant tort liability protection and essentially eliminated manufacture liability for unavoidable, adverse side effects. The act was originally developed due to the growing amount of lawsuits towards vaccine manufactures and the fear that the potential for lawsuits would discourage vaccine manufactures from further developing vaccines.[143] NCVIA also established the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), a program designed to provide financial compensation for those who file a petition and are found to have been injured by a VICP covered vaccine.[144] VICP covered vaccines include: diphtheria; haemophilus influenza type b polysaccharide conjugate vaccines; hepatitis A and B; Human papillomavirus; and seasonal influenza.[145]

Petitions are filed with the United States Court of Federal Claims were HHS medical staff review the petition to see if it meets criteria for compensation and then make a recommendation.[146] Afterwards, the United States Department of Justice creates a report that includes the medical recommendation as well as a legal analysis then submits it to the Court.[147] The report is presented to a court appointed special master who decides whether compensation should be granted and, if so, how much the compensation should be.[148] If the petition is dismissed, the decision may be appealed, or the petitioner may file a civil suit against the vaccine company.[149]

As mentioned before, the VICP is only for injuries sustained from the administration of a covered vaccine.[150] There are a number of currently available vaccines not covered, including a potential COVID-19 vaccine.[151] This makes sense because there are a myriad of potential issues that could occur when dealing with a therapy that has had to be approved through the use of an EUA. In response to this issue, the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act of 2005 (PREP Act) established the Countermeasures Injury Compensation Program (CICP).[152] The CICP is a federal program designed to provide benefits for those that are injured as a result of the administration of use of a covered countermeasure.[153]

Because COVID-19 vaccines would come into the marketplace under EUA, any injuries sustained because of the vaccine would fall under the CICP.[154] Other medical countermeasures that have been covered by the CICP include: Ebola, Nerve agents and certain insecticides, Zika, Pandemic Influenza, Anthrax, Acute Radiation Syndrome, Botulinum Toxin, and Smallpox.[155] Claims through the CICP are conducted in an administrative process, and claims are either approved or denied by the HHS.[156] Claimants have one year after the administration or use of the medical countermeasure to file for compensation from alleged injury from the countermeasure.[157]

7 Recommendations for Future Emergency Vaccine Approval Plans as well as Recommendations for Standard Vaccine Process

7.1 Automatic Integration of FDA Guidance and Review throughout Clinical Trial Phases

The integration of FDA guidance and review throughout the entire vaccine development process in OWS is a huge reason that vaccine development for a COVID-19 vaccine has been able to maintain standards for safety and efficacy while remaining speedy. Although in a non-pandemic situation such a quick turn around would not be necessary, automatic, early integration of FDA guidance and review would likely greatly decrease the time frame for the development of needed vaccines and drugs so that they could be put out to the public more readily. Although it would not be feasible to have early FDA intervention with every therapy candidate, a higher standard of evidence showing potential to treat conditions could help with prioritizing which therapies the FDA chooses to guide through the process.

7.2 Increased Funding for Conducting Clinical Phase Trials

Another reason why OWS has been as successful as it has is due to the funding available for conducting trials, which removes the financial hurdle of being able to complete the trials. For therapies that show high promise in drastically changing the outcome of a serious condition, the FDA should more readily offer funding so that trials can be conducted seamlessly without the burden of waiting for financial backing from outside sources. The FDA could provide an application process to request funding similar to how the application processes are for the current expedited programs.

7.3 Provide Incentives for Development of Accelerated Vaccine and Drug Approval Plans for Different Scenarios

OWS was started from the ground up as a novel plan for major expedition for vaccine development in a pandemic scenario. While OWS provides a good groundwork for other situations, the FDA should incentivize scientists and experts to come up with thorough plans for other events that may occur, such as a biological attack or a radiation attack. Having multiple fleshed out plans for different scenarios could greatly increase the chance of mitigating huge economic and human loss simply because the United States would be prepared and would have ideas for development, manufacturing, and distribution already in place.

7.4 Increasing Time for Vaccination Injury Compensation

In the case of injury from a COVID-19 vaccine, the deadline for filing a claim should be increased from one to several years. This is because of long-term, adverse side effects would not be known because the vaccine was delivered so quickly, so people would not have fair notice of possible long-term effects until it happens to them, and by then it would be too late to file. While post market surveillance and use of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System may help to mitigate the effects of an adverse event, it would not be equitable to only allow people a short time to be compensated for injury, especially since manufacturers, distributors, healthcare providers administering medical countermeasures, state and federal government, and their agents are given further broad liability protection from the PREP Act.[158] Under the PREP Act, an actor would only be liable if willful misconduct that caused death or serious injury is shown.[159]

8 Conclusion

OWS seemed like a far-fetched endeavor when it was first announced, due to the standards already in place for vaccine development and approval. However, OWS has shown that it is possible to create a safe and effective therapy in a quick amount of time due to the partnerships of multiple federal agencies and the private sector. This quick turn around for COVID-19 vaccine development will hopefully help to control the disease, help to save lives, and may help the return to normalcy.

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Introduction to Volume XIII

- Articles

- Operation Warp Speed: A Legal Analysis of the Vaccine Development Process and How We Got Here

- Attempting to Mitigate COVID-19: Does the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act Provide Patent Infringement Immunity?

- Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio Public Health Ordinance During COVID-19. Are They Constitutional?

- Contact Tracing in the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Digital Contact Tracing Affects Our Individual Rights

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Introduction to Volume XIII

- Articles

- Operation Warp Speed: A Legal Analysis of the Vaccine Development Process and How We Got Here

- Attempting to Mitigate COVID-19: Does the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act Provide Patent Infringement Immunity?

- Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio Public Health Ordinance During COVID-19. Are They Constitutional?

- Contact Tracing in the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Digital Contact Tracing Affects Our Individual Rights