Abstract

As a crucial component of the materiality of the first world empire, textile culture documented in archival cuneiform documents, visual art, and archaeological materials from 1st-millennium BC Assyria enables historians to reconstruct the social identities, power visions, and economic systems of the people who ruled the “Land of Aššur”. Through the analysis of royal clothes, it is possible to form an idea of the clothing ensemble, the aesthetic, and power visions that shaped the presence of the king and his queen in public ceremonies and in visual art narratives, and to see how royal textile art played a role in political communication. Royal garments, combined with power accessories such as royal insignia and other objects, represented a powerful means to visualize royal personhood and what the institution of Assyrian kingship meant in the imperial phase of Assyrian history. Representations of royal scenes in visual art integrate the documentary picture from texts and archaeological materials and show how the royal costume developed over the Neo-Assyrian period and how the centrality and superior status of the royal person were emphasised by visual interaction between the king’s clothes and other textiles in the scene. Queenly garments represent another channel for the communication of the success of the Assyrian imperial project. Less represented in textual sources and material evidence are other upper-class sectors of Assyrian imperial society, in which textiles equally played an important role as markers of social identity and status. Non-royal textiles were an integral part of power narratives in the Neo-Assyrian age, contributing to create the sense of a common Assyrian identity, of elite’s unity and cohesion, and full adherence to the imperial project.

1 Introduction

As a crucial although partially invisible component of the materiality of the first world empire, textile culture of 1st-millennium BC Assyria – documented in archival cuneiform documents, visual art, and archaeological materials – enables historians to reconstruct not only the economic system and the elite goods circulating within the social elite who ruled the “Land of (the god) Aššur” (māt dAššur) in the imperial age (9th to 7th century BC), but also the vision of power that informed their lives and activities and that manifested the success of the imperial project.

Research on the textile culture of the ancient world corroborates this interpretation and offers another perspective for understanding the Assyrian imperial project and the ruling elite’s culture. Textiles, especially clothes, are important not only for their intrinsic material, technical and workmanship characteristics, but also for their symbolic significance within social and political contexts.[1] The use of clothing to convey social messages such as status and affiliation to a group appears to have been a primary function almost since the beginning of history.[2] Seen in their function as a form of non-verbal social communication,[3] clothes convey the shared values of a social group, defining the individual identity of the wearer and the collective identity of the group to which he or she belongs, and constructing complex systems of signification that are projected onto the world.[4] Dress has a relational function, as it helps the individual to explicitly present his or her identity, values and attitudes to another, and to socially construct the basis for his or her interactions.[5] An individual’s dress signals to the external viewer the type of social relationship to be entertained with the wearer (equal or hierarchically subordinate) and the information it conveys is crucial in regulating the wearer’s interactions with the outside world. Clothes concur with bodies and gestures to express political norms and practices in a variety of forms, even theatricalized, of manifestation of power and play a significant role in the definition of ideological systems and as powerful carriers of political messages.[6]

Political and religious ideologies play a major role in dress. In the field of political ideologies, the dress – of the king or the political leader – expresses and consolidates power.[7] The clothed body thus becomes a fundamental vehicle of the system of values and policies to which the ruling class adheres. The body is also the privileged space of the religious identity. The religious dress concretises the values of the religious system to which the individual belongs and materialises the hierarchical position within a religious group.[8] Not only the dress itself, but also its representation in visual art plays a crucial role in political and religious communication. This aspect is of particular relevance to the way the Assyrian imperial elite constructed their cultural identity. It also plays an important role in our modern reconstruction and understanding of what Assyrian elite dress looked like. Although idealisation and symbolism play a crucial role in royal depictions and the depiction of dress was not the main focus of Assyrian artists,[9] these depictions nevertheless offer important information on how kings, queens, court dignitaries and service personnel dressed and were expected to dress. Moreover, considered in the context of the social image of an individual and, in particular, of a political leader, clothes and other personal accessories are not separate elements from the wearer’s body. Anthropological research shows that every dress can be considered from the point of view of its visible and invisible signs, the former relating to the outward features exposed to the viewer’s sight and the latter hidden from view. The information that these different signs contain makes it possible to identify the individual and the society to which he or she belongs.[10] According to the perspective of the sociological study of dress, the non-verbal communication that clothing establishes contributes to constructing the individual body as a social actor and conveys the social, political and cultural meanings that the wearer represents in a given community. Dress is also an indicator of gendered identity.[11] This leads one to see the Assyrian king’s (the queen’s and other court figures’) clothes also in the role they play in the construction of gender identity and its properties, dictated by developments in Assyrian elite’s culture. The construction of the king’s masculinity, his emphasisation or de-eroticisation, is an integral part of this process of constructing the public image of the Assyrian ruler that is visible in imperial art.[12] The study of the queen’s clothing and her clothed body represents another important field of investigation, for example to understand how the socially constructed category of femininity in Assyrian elite’s culture is expressed in relation to power and high rank.

Not unlike other civilizations of the ancient world, Assyrian society can be defined as a “clothing-society” to use Marzel’s terminology, i.e. one in which conservatism and adherence to tradition are valued as signs of social stability and order.[13] When applied to specific cases of the cultures of the ancient world, for example the dress culture of the Assyrian king and the ruling elite of the imperial age, Marzel’s definition of “clothing-society” appears too rigid in any case, as innovations in dress are certainly recognisable even in this type of society. Changes in clothing may have been determined by the variables of time and place, by the aesthetic tastes of new power groups within the imperial elite, the elite’s increased economic resources and new cultural trends that affected the court and the ruling class.[14]

In the light of these preliminary considerations, in this study I will consider three aspects that are relevant to understanding the role played by textiles in the construction of the identity of the elites that ruled Assyria, benefitting from the expansionistic project: 1) the king’s dress and its significance in the Assyrian political discourse; 2) the queenly dress as representative of the “other side of Assyrian imperialism”; and what can be termed as 3) “the textile landscape” of the empire. The analysis of these aspects reveals how clothing (and other types of textile products linked to the royal figure and the palace) constituted a powerful channel of expression of Assyrian imperialism and its success. To do this, the investigation must necessarily rely on different types of sources, written, visual and archaeological. These sources differ in context and purpose and their peculiarities will be discussed in this study. However, each of them adds an important piece in the understanding of what dress and dress practices were in the Assyrian imperial elite. As shown by other disciplinary fields of textile research on the ancient world where the corpus of organic textile finds is limited,[15] the interplay between textual, iconographic and archaeological sources appears vital for the reconstruction of what textiles were like in terms of workmanship and as vehicles of social messages.

If the items of clothing of the king and the members of the government elite of Assyria shared the common characteristic of being the product of the large-scale mobilization and centralized control of fibres, materials for textile processing, craftspeople, techniques, and artistic styles from all the near-eastern regions politically and militarily subjugated by the Assyrians – all witnesses to the success of the Assyrian expansionist project – the clothes that covered the king of Assyria were of paramount importance. The royal ensemble vestimentaire was not only central in asserting Assyria’s military and political superiority but also in communicating the specific power system that ruled Assyria, the political-religious construct that informed the office of kingship (šarrūtu) and its objectives to the internal and external recipients of this message of dominion. As vectors of social meaning, the items that made up the royal dress played a role in the construction of identity both at the level of the single individual king and the social group to which he belonged. They also played a role at the level of the ideological discourse that shaped the communication strategy underlying the Assyrian elite’s imperialistic project. In a few generations of kings, the imperialistic project led Assyria to expand enormously its political boundaries, unifying a vast area of the Near East from southern Anatolia to the Persian Gulf and from Western Iran to the Levantine area and Egypt, bringing to reality the millennia-old royal claim of universal dominion and predating the later programmes of imperial unification of the Near Eastern scenario that were launched by the Chaldean kings, the Achaemenid Persians, Alexander the Great and the Seleucid kings, the Romans, the Parthians, the Sasanians and the Arab-Islamic rulers. In Assyria, it was not only the royal insignia, namely the ḫaṭṭu, “sceptre”, the ušpāru, “ruler’s staff” or šibirru, “pastoral staff”, and the kakku, “weapon”, represented by the sword or by the bow and arrows, that materialised the royal office[16] but also all those objects that covered the royal body and that were considered befitting the king’s functions: these were the jewels (šakuttu), the ornaments (tiqnu), and the dress (lubussu).[17]

The king’s clothes embodied a full range of meanings to be conveyed visually during public ceremonies, from court meetings limited to palatine members (members of the royal family and high-ranking civil and military officials) to larger ceremonial events open to visiting foreign delegates from vassal kingdoms, as well as parades in the presence of military officials and royal troops, triumphal processions after military victories, akītu-processions and other yearly cultic festivals in the Aššur Temple of the Holy Citadel of Assur (Qal‘at Šerqāṭ) or in other shrines of the country, and oath-taking ceremonies for the stipulation of succession treaties or related to the imposition of vassalage treaties on submitted foreign rulers. The common people of Assyria would have had the opportunity to see at a remote distance the royal person during public official ceremonies, presumably without any chance to appreciate the specific details of the luxury and finely crafted items that covered his body (and that constituted the professional pride of the royal tailors and dress decorators who created them). However, the same clothes, although in simplified form and bearing no details about decoration, were also visually accessible to commoners in various regions of the empire’s territory through the media that conveyed the king’s message of dominion in the central cities of the Assyrian heartland, provincial centres, and vassal states, as the sovereign was depicted in countless royal stelae, rock carvings, and other public monuments located in different parts of Assyria to celebrate his achievements.

2 The King’s Dress and Its Significance in the Assyrian Political Discourse

Everything we know about the royal costume of 1st-millennium BC Assyria can be reconstructed on the basis of the textile terminology documented in written cuneiform sources and from representations of the Assyrian king in visual art, especially large-scale artefacts such as palace bas-reliefs, stelae, obelisks, and statuary. Both material culture terminology and visual evidence are sources that document objects in use. But both sources present a limited selection of the artefacts they refer to. Types and details of textiles mentioned in the textual evidence are subject to the purpose of the message the text was meant to convey, the interest of those who commissioned the scribes to record textiles in writing, the context of production of the message and the scribe’s ability to describe the textiles (in terms of appearance and workmanship) he had to record on texts. Representational evidence of textiles is also subject to certain constraints that are peculiar to the specific artefact, above all the type of message to be conveyed, the artist’s skills, the artistic style, the king’s personal tastes and the public it was intended for. Firstly, representations of textiles show a limited selection of products, some of which can be compared with items mentioned in contemporary texts, but many others cannot. This selection in visual art is clearly determined by the specific choices made by the kings who commissioned these artefacts. In addition, textiles represented in visual art are inserted in specific royal scenes and narratives and as such they are imbued with the notions that informed Assyrian imperial ideology. This means that these textiles (as many other categories of material culture objects) also work at symbolic or ideal level of communication, reflecting the ideological (political, religious and in general cultural) vision of the commissioner and the social and cultural group to which he belonged. Since this high-ranking social group participated in the imperial project and enjoyed its fruits in terms of possession of high-quality objects and social visibility within the court and the ruling elite, it shared the same values, ideals and visions of power of the king. These different and opposite readings of the objects represented in royal visual art – as real objects or symbols – is especially evident in the case of Neo-Assyrian bas-reliefs, a monumental medium primarily aimed at reinforcing the imperial elite’s self-image and instil fear and awe in external visitors,[18] prompting them to recognise the inevitability of the Assyrian empire and the need to submit unconditionally to it. Gods and posterity were probably other potential viewers of the images in the bas-reliefs.[19] The former would have rejoiced to see that their human protégé had fully realised the divine mission in the world, the latter, primarily future successors to the throne, would have found in this visual memory the model of perfect kingship and civilization at its highest degree of realisation. In any case, there is no explicit information as to whom the reliefs were addressed, nor is it clear whether there was a specific message that the reliefs were intended to convey.[20]

In the carved wall panels different levels of communication interpenetrate, leading to different positions regarding the degree of reliability that these monumental representations have as historical source.[21] The textiles and other royal objects represented in these artefacts certainly refer to real objects. The assumption is supported by the fact that many Assyrian royal objects match items of the archaeological evidence. Textual information, albeit scarce, incomplete, originating from specific communicative contexts and produced for specific informational purposes and target audiences, can offer a contribution to a deeper understanding of the objects depicted in visual art and found at archaeological level. The interpretation of the items depicted in the reliefs must in any case go beyond the use of the reliefs as a mere illustration of reality and of what is documented in textual documentation[22] and take into consideration other important factors, such as the artefact-specific factors that affect the representation, from the artistic and architectural programmes to which the medium belongs to the ideological message[23] and the degree of idealisation of the images depicted, not to speak of the royal culture of the specific reign period in which the medium was created. Although inspired by the reality of everyday life, the iconography selected textiles and other royal artefacts that were recognisable to viewers and reflected the perceptions, expectations and ideological systems shared by specific social groups.[24] Clothing and other textiles have a significant place in the definition of the Assyrian royal figure as transmitted through the carved wall panels and other monumental sculptures. What these visual media convey of the royal figure is an idealised image, where the material accessories that connote it contribute to constructing the values and functions of Assyrian kingship as it was conceived at that precise historical moment, rather than the peculiarities of the individual person of the sovereign. These material items associated to the royal person also act as signature elements to make the scenes depicted in the reliefs real and situated in specific events.[25] The degree of adherence to reality in the representation of textiles, i.e. the resemblance to textiles actually in use, evidently varied according to the skill of the artist, the style and the message to be conveyed. Through a visual representation apparently characterised by cultural continuity, loyalty to tradition and immutability of content, the culture of kingship, the political-religious message and the royal imagery underwent changes during the Neo-Assyrian era,[26] changes that are partly witnessed through the textiles documented in visual art.

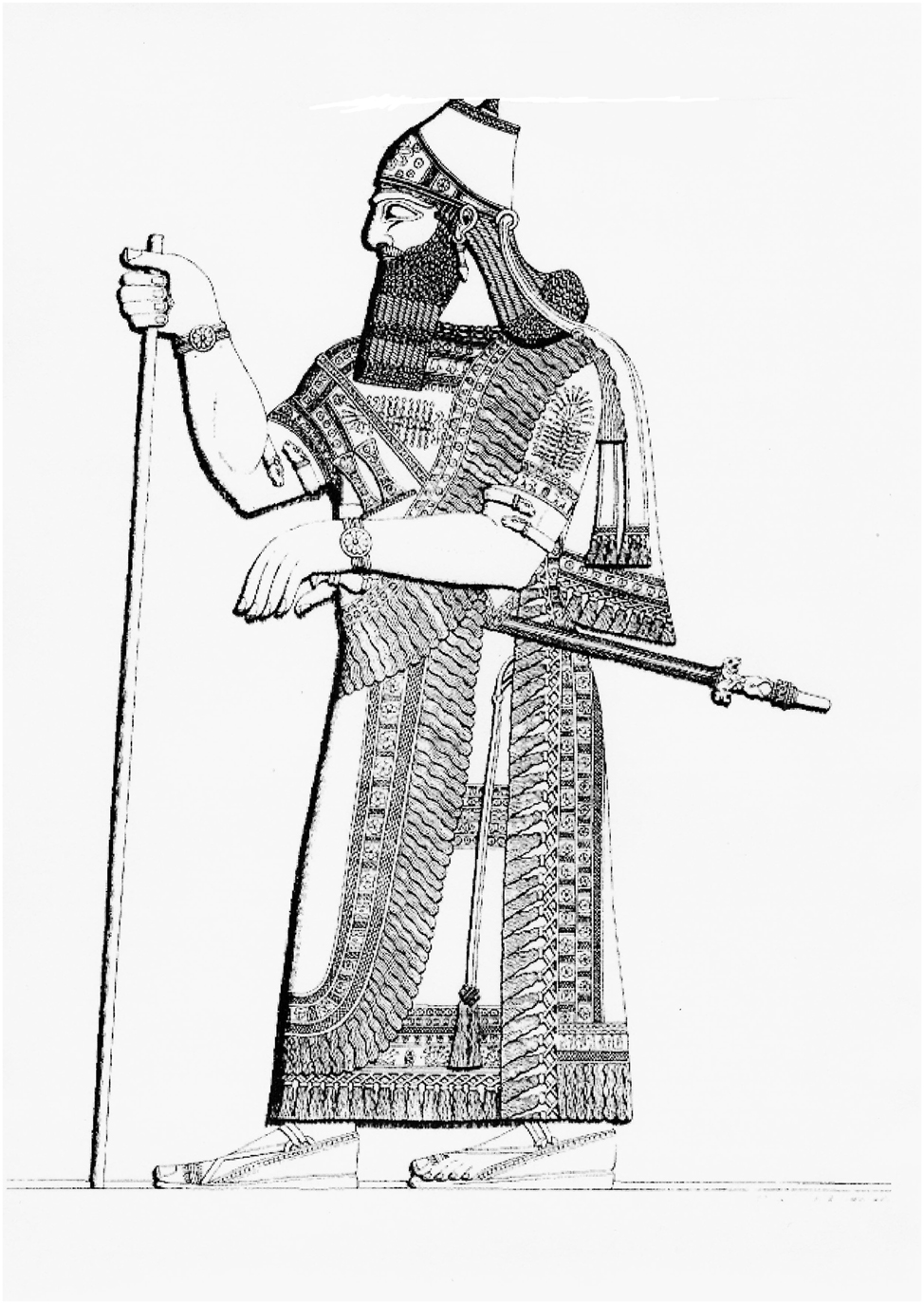

The analysis of the royal imagery shows that underlying the construction of the person of the king in visual art was a conceptualisation not only of the king’s clothing but also of his body. As royal iconography of bas-reliefs shows, the Assyrian royal figure communicated his leadership qualities through physical and postural characteristics, such as a well-formed and muscular body, an upright and proud posture and a direct gaze. Clothing and accessories, which are elements external to the person, played a key role in highlighting these physical and postural characteristics of the sovereign (or, in the case of less physically gifted rulers, presumably compensated for their absence) and communicating notions of the royalty he embodied.[27] If we compare this posture and its relation to royal dress with that of enemy rulers kneeling at the feet of the Assyrian sovereign or tearing off elements of their royal dress through convulsive acts of the body,[28] it is clear how these examples in visual art and ideologically-charged texts serve to depict the unsuitability for kingship of enemies. The enemies’ royal robes do not manifest what kingship should be and their destruction by the enemy kings themselves signals the inconsistency of their power.

In the case of the Assyrian royal dress, the main components of the outfit – the headdress; the long, short-sleeved fringed tunic; and the fringed overgarment – were not only markers of the ruler’s social identity[29] and position in the eyes of the elite and all the Assyrian subjects; they also conveyed values and meanings of crucial importance in the imperial ideology and religion of 1st-millennium BC Assyria. The royal dress contributed together with other accessories of the royal person not only to making the historical figure of each king a perfect and superhuman figure, thus demonstrating the rightness of the divine choice on that particular sovereign, but also helped to construct through the king’s clothed and accessorized body the very image of kingship (ṣalam šarrūti), i.e. the embodiment of Assyrian royalty itself. From this perspective, the royal dress represented a material vector of the ideas that in the written political communication of royal inscriptions were conveyed by the titulary and the narratives of the king’s military, ritual, and building activities. The same ideas conveyed by the royal discourse of inscriptions were also channelled by royal ritual texts and court literature, all written media that bore witness to a restricted and literate circle of recipients of the royal discourse within the ruling elite, and by oral channels to different levels of recipients within the government elite and the Assyrian urban society in the context of public ceremonial events. We can argue that the visual and material medium of the royal dress functioned as a manifesto or a political programme of Assyrian kingship, enabling the construction of Assyrian royal identity and the communication of the Assyrian king’s message of power to his subjects. Depending on social position and official circumstances, the Assyrians could have experienced in different ways the vision of the royal person in its full majesty, through direct encounter in private or official occasions, at a remote distance, or through indirect channels. Along with other material vectors of both monumental and minor arts of the Assyrian imperial age, textile art – a sector of Assyrian art and craftsmanship long neglected in studies of Neo-Assyrian art history because of the poor archaeological evidence regarding textiles, limited to representations in visual art and a few fibre remains from burial contexts – was consciously developed in the imperial period as a powerful means to spread the message of unrivalled dominion achieved by the Assyrians with their expansionist project.

Although it is possible that the Neo-Assyrian royal wardrobe included a variety of ceremonial and non-ceremonial clothes to be used on different occasions, private and public, in which the presence of the king was required, this alleged variety of the royal clothing is not documented in Assyrian art and details on the characteristics of the king’s dress, for instance in regard to colour, are very scarce. From Til Barsip wall paintings, it seems that the royal outfit was polychromatic, as shown by the red-coloured motifs and the blue background of both the shawl and the long tunic worn by the king[30] or by the representation of the monarch wearing a green tunic adorned with rosettes and a white tiara with ribbons on a 9th century BC glazed wall tile from the North-West Palace in Kalḫu (Nimrud), possibly representing a ritual scene connected to a victorious military campaign.[31] In this glazed tile, it is also interesting to note the chromatic alternance of green and yellow in the petals of the rosettes adorning the royal tunic and in the frontal rosette of the headband, in the tassels, and in the discs of the knee-high band, as well as in the round-shaped locks of the shawl’s fringes and in the ending tassels of the tiara’s ribbons. The linear borders of the tunic, included the collar, are yellow-coloured. A white tunic bordered with red and blue fringes is attested in the decoration of Residence K at Dūr-Šarrukēn (Khorsabad).[32] In the Neo-Assyrian period, tiaras could be of different chromatic combinations, due to the colour of the truncated headgear and to those characterizing the decorative horizontal bands and the ribbons.[33] The royal headdress on the above-mentioned glazed tile is characterized by a white main part with a black pointed top with a black horizontal band; the headband was white, with a frontal yellow rosette and ribbons.[34] Another example from the early Neo-Assyrian period is given by a Til Barsip wall painting in which the king’s headdress, which has no decorative bands, is completely red and equipped with blue and red ribbons on its back.[35] As far as the late Neo-Assyrian evidence is concerned, Sargon II’s headgear that we see in a Khorsabad relief shows a white background with red bands adorned with white rosettes, but other attestations of royal tiaras in imperial art show the preference for red colour and white bands with yellow rosettes or blue disc-shaped motifs.[36] The general impression is that a wide variety of chromatic combinations characterized these items of the royal dress, presumably dictated by the specific ceremonial occasion in which the monarch was involved as well as by aesthetic preferences that were specific to individual kings and historical periods. From letters of the royal correspondence we learn that Neo-Assyrian sovereigns were consulted about the quality and workmanship of royal images,[37] and it is plausible that their opinion on the shape, colours, colour combinations and decoration of the clothes depicted on statues, bas-reliefs, and other art objects was decisive to accord the materiality of the royal representation with the aesthetic vision and the political message that the kings intended to convey. In the field of textile art and royal dressmaking, given the importance that royal costume had in the presentation of the Assyrian king’s person on various ceremonial and ritual occasions, it is just as reasonable to assume that sovereigns were consulted in the choice of materials, shapes, colours, decorative themes and accessories when making a new dress. This leads one to think that every ceremonial dress worn by the king was the result of an active interaction between patron, aesthetic and dress advisors, tailors and dress decorators. Every ceremonial royal dress was therefore the material synthesis of an ideological, aesthetic, and technical project.[38]

2.1 Identifying the Royal Clothes: the Contribution of Textile Terminology

Descriptions of textiles and textile terminology that we derive from written sources can be useful for a better understanding of textile products and, in the most fortunate cases, for their identification in the light of the comparison of textual data with iconographical evidence. They can therefore complement the information provided by archaeological evidence and visual art. Indeed, the study of textiles cannot be limited to the separate study of these different sources, but must consider them together in a unified approach. However, the use of textual information is not without its problems. Its characteristics and limitations must therefore be taken into account. Neo-Assyrian textile terminology mainly concerns luxury products (of Assyrian and foreign origin) consumed by the imperial elite and personnel of the state sector. Some terms enable scholars to form an idea of the royal dress and its main components. However, the way in which textile products are qualified by the scribes diverges in the sources, clearly due to the purpose of the text in question (informative detail in the case of administrative and everyday documents, in contrast to general absence of interest in peculiarities of the textiles listed in booty and tribute enumerations of royal inscriptions). While a wide lexical variety can be found in archival and everyday documents, a generic, repetitive and rather standard terminology characterises the references to textile products acquired as tribute or booty from conquered countries in royal inscriptions’ war narratives. Formulaic expressions used by the authors of royal inscriptions usually concern garments with polychromatic trim and linen clothes, with rare exceptions, such as the šaddīnu-dress found in Taharqa’s palace, as we shall see below. Behind these generic definitions there probably was a wide variety of products of which the scribes accompanying the troops may have taken note during the military campaign. In all likelihood, these foreign products were identified by the scribes with terms in the languages currently used in the imperial administration, namely with Assyrian or Aramaic names, less likely with Assyrianised forms of the indigenous names.

Terminology can also help in understanding the dress culture of the Assyrian elite and its changes. For instance, the frequency with which certain high-class textiles (e.g., gammīdu, gulēnu, maqaṭṭu, šaddīnu and urnutu) and materials (kitû and būṣu) appear in everyday texts issued by the central state administration is probably indicative of dress preferences and new aesthetic tastes emerging in the ruling class, as well as changes in upper class fashion of the imperial age. The relationship between written sources and iconography is also not without problems. In the field of dress, a comparison between the clothes mentioned in the texts and those depicted in visual art shows a fundamental difference: while the terminology testifies to the use among the Assyrian elite of a great variety of dress elements, the iconography of dress is instead limited to a reduced and highly standardised set of dress types, with the inevitable risk of assuming that the dress types depicted were the only ones in use.[39]

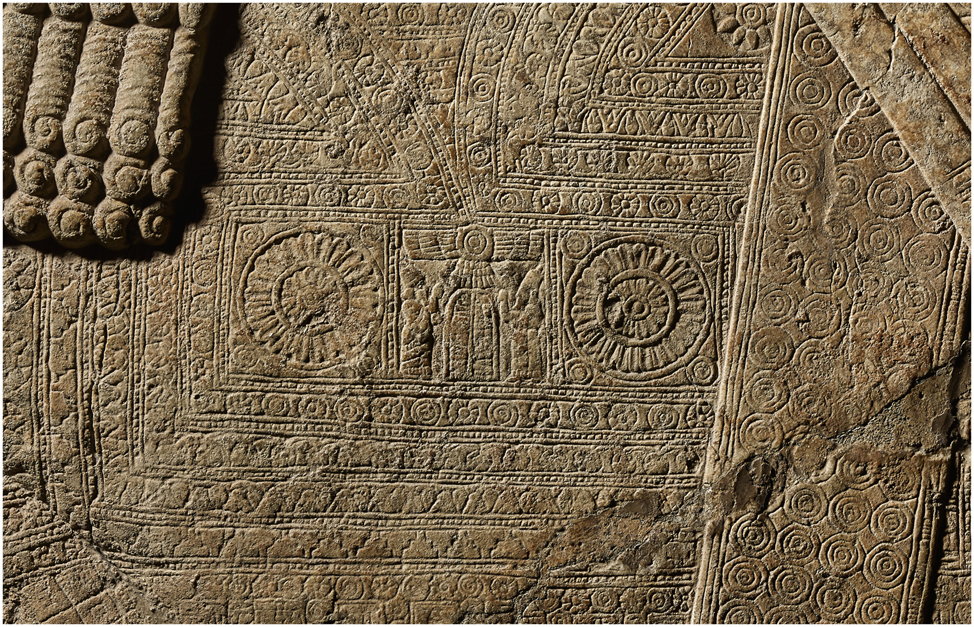

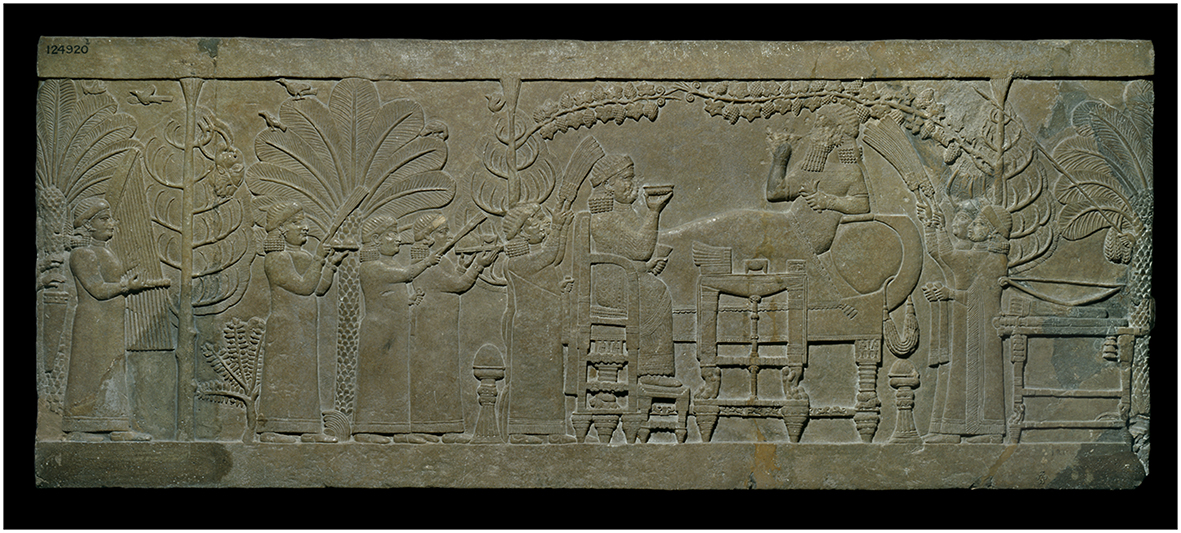

From a terminological point of view, when Neo-Assyrian texts refer to the royal dress, the word kuzippu is used. This is a versatile textile designation that also occurs for both elite and ordinary clothes in general and for female clothes as well as for military uniforms.[40] Given the main articles that composed the king’s dress and the use of more specific items of clothing, it is possible that the long, fringed tunic, made of wool or linen, was called by the term kusītu. The possibility that the king also wore an urnutu is suggested by the fact that such an item, according to an administrative record, could be decorated with figural decorations, for example bulls and goats,[41] the visual counterpart of which is provided by Assurnaṣirpal II’s tunic and shawl in the drinking scene of Reliefs 2–3 of Room G in the North-West Palace in Kalḫu,[42] which shows decorative motifs in the form of wild goats, winged bulls, lions, and supernatural beings (i.e., purifying apkallus or winged genii with the so-called “Assyrian sacred tree” or “tree of life”, a stylized palmette-type tree, and analogous beings wrestling with winged animals or lions). The tunic worn by Assurbanipal represents the 7th century version, characterized by a finely-decorated chest part as the visual focus of the whole decoration, encapsulated by rows of lotuses and buds and rows of palmettes, alternating with various rows of concentric discs and rosettes, and of crenellated structures, as we will discuss below.[43] Candidate terms for the fringed overgarment are elītu, ḫullānu, maklulu, and qirmu.[44] This piece of the royal clothing was a sort of shawl or stole that could be worn to cover the body below the waist or just the tunic’s fringed edge. The statue in the round of Assurnaṣirpal II from the sanctuary of Šarrat-nipḫi in Kalḫu, a stele, and a ritual scene on a wall-carved slab from the North-West Palace[45] show that this shawl was fastened on the top of the tunic to cover the left arm and, passing over the right shoulder, was secured to the waist-belt. The ḫullānu could be decorated with vegetal motifs, as shown by a Middle Assyrian text from Assur, perhaps similar to the vegetal decorations (i.e., rows of palmettes and buds or cone-shaped vegetal items in alternation, rows of only cone-shaped items and rows of stylized lotuses, palmettes and buds) that adorn Assurnaṣirpal II’s dress.[46] This king also used a stole decorated with large crenellated structures bordering its fringed edges.[47] A shorter version of this stole (or a simple covering for the hips) appears in a war scene, and it is decorated with concentric hexagonal motifs.[48]

Sashes or belts constituted another important article of the royal clothing, although representations of the king’s dress in visual art do not always include this item; these items were possibly called nēbettu, nēbuḫu, or ṣipirtu in Neo-Assyrian.[49] The terminology concerning parts of garments may be applied to both the royal and the queenly dress. The word aḫāte probably indicated the sleeves,[50] which in the king’s outfit are generally short while in the queenly clothes they are long. The term libānu referred to the collar of garments, which could be finely decorated.[51] Moreover, the king’s dress as well as those of the queen, crown prince and high-ranking dignitaries were also characterized by fringed borders, possibly described by the words appu, qannu, or sissiqtu.[52] The fringed edge could be made of simple loose threads or arranged in series of tassels. This was a peculiarity of Assyrian vestimentary tradition. Individuals of different social classes also wore fringed clothing, as evidenced by the reliefs,[53] but the quality, polychromy and quantity of fringes must certainly have been a characteristic element in the clothing of the Assyrian elite. The fringe communicated the social and economic status of a person and the quantity of fringes and tassels signalled the wearer’s high rank and power. Both tunics and overgarments could be edged by fringes or tassels. For instance, the feet-length overgarment could be edged both with fringes and tassels, as may be seen from the standing figure of Assurnaṣirpal II on a palace wall panel.[54] In the same scene, the king wears a tunic bordered by various decorated bands and a series of tassels. Polychromatic and decorated bands with figural decorations that adorned the edge of tunics and overgarments were called birmu.[55] These parts were woven separately and then sewn onto the item of royal clothing. With the term uṣurtu, the decorative design on clothes was indicated.[56] Within the category of uṣurtu both figural and geometrical elements were possibly included. Decorations on the garments could have been made in different ways by the royal tailors, presumably by using threads of different colours or by embroidering. Bands of previously prepared woven fabric bearing the design were then stitched onto a specific part of the garment.[57] These bands were of variable size, depending on the part of the garment to be enriched by decoration. Another method consisted of attaching metal items onto the woven cloth.[58] It is not excluded that in the middle part of small geometrical elements on these border bands, especially in concentric squares, circles, or floral motifs, the central element was a coloured stone stitched onto the cloth.

Neo-Assyrian texts show that decorative attachments were associated with certain items of clothing. Kuzippus and maklulus could be decorated by attaching beads (abnāte), presumably of different colours,[59] while urnutus were enriched by stitching eye-shaped or concentric disc-shaped elements (ēnāte).[60] Decorations in the form of rosettes and stars, both made of fabric or metal, were called aiarē (aierē, with vowel harmony) and kakkabāte.[61] Other motifs were called uznē, literally “ears”, possibly referring to ear-shaped or half-circle (or concentric half-circle) motifs adorning the borders of garments.[62] Concerning the royal headdress, the tall and truncated cone-shaped variety of tiara, which in the 8th and 7th centuries BC became the standard royal headgear, was adorned with three horizontal bands (two of which are part of the tiara while the third one is a headband or diadem with ribbons wrapped around the tiara’s base)[63] and was called by the word kubšu.[64] This item could be decorated with rosette-shaped motifs and other items as well, while with the word kulūlu both the royal headband and the crown were indicated.[65] Presumably, the design and the colours of the decoration differentiated the royal from the princely headband, but common elements could characterise both the royal and the crown prince’s headband. Another term for headband or diadem was pitūtu, which, however, referred to the headgear worn by crown princes.[66] The official outfit of princes at the Assyrian royal court consisted of a tasselled tunic around which a fringed stole or shawl was wrapped tightly in a spiral. This may be seen in the relief from Sargon II’s palace in Dūr-Šarrukēn (Khorsabad) in which the crown prince and his father are portrayed,[67] in the scene carved on a slab of the South-West Palace in Nineveh (Quyunjiq) in which Sennacherib is depicted on his throne while inspecting the booty from the captured city of Lachish and receiving the crown prince,[68] and in Esarhaddon’s stele from Sam’al (Zincirli).[69] In Esarhaddon’s stele, for example, the princes Assurbanipal and Šamaš-šumu-ukīn wear feet-length, short-sleeved tunics and headbands that were typical of the vestimentary traditions of Assyria and Babylonia, respectively.[70] This representation had the aim of emphasising through textile language the equal dignity of the two states in the unity of the empire, but also to clearly indicate the dynastic continuity of royal power in Assyria. The headbands worn by the two princes are in fact entirely different: that worn by Assurbanipal ends with a fringe and bears decorative elements that are similar to those adorning his father’s royal tiara (concentric discs),[71] while the one that encircles Šamaš-šumu-ukīn’s head is of a variety that is alien to the Assyrian dress tradition and consists of a thin band with small protruding elements along the entire edge.[72] It is also possible that the latter variety of headband may have been deliberately created by the royal tailors specifically for Assurbanipal’s brother,[73] presumably as a sign of distinction of his status to be displayed at public ceremonies involving his and Assurbanipal’s presence. It is also worth noting that the decoration of the ribbons dangling from Assurbanipal’s headband explicitly recalls that of Esarhaddon’s ribbons, while also signalling Assurbanipal’s different status (a single decorative band with discs instead of two bands, showing that he was hierarchically inferior to the king). With regard to the princes’ robes, in addition to the tasselled tunic, Assurbanipal also wears a fringed shawl that spirals around his body, covering almost the entire tunic and leaving the left shoulder uncovered. In contrast, his brother wears only a tunic. The only difference between Assurbanipal’s shawl and Esarhaddon’s is that the royal shawl also covers the shoulders. Thus, several elements in Assurbanipal’s costume signalled to the spectator the close dynastic link between him and the king of Assyria, and his royal destiny. Through this differentiated and regionally based “dress code”, the different royal destinies of Esarhaddon’s heirs are communicated in this stele. This differentiation, however, could have been an entirely iconographic creation of the royal artists, whereas in the reality of court life in Nineveh Assurbanipal’s brother must in all likelihood have been wearing a princely dress in line with the Assyrian tradition. It is hard to believe that, when he was young and living in Nineveh, he would appear at the royal palace or attend public ceremonies dressed as a Babylonian.

The designation for the princely dress is attested in another text from the reign of Esarhaddon. In the royal inscription that describes his ascent to power, Esarhaddon mentions his princely garment (ṣubāt rubûti, literally “garment of rulership”).[74] Another possible representation of princely clothes can be seen in the hunting scenes from the North Palace in Nineveh, where Assurbanipal is represented in clothes that appear more suitable to horse-riding, chariot-driving, and hunting, since he generally uses a headband and a horseman’s short-sleeved asymmetrical tunic or, as shown in the chariot-driving scenes, only a tiara and a long tunic, with no shawl.[75] If these scenes represent Assurbanipal in the period when he was crown prince, the clothes depicted were probably those used during his youth.[76] However, representations of the king without tiara or shawl, although limited, demonstrate that the presence of these items was not necessary on all the public occasions in which the monarch took part and, probably, was only required for specific events. It is clear that the tiara and the shawl were dismissed when the king was not involved in certain ceremonial events, as may be seen in the case of war-making, hunting, and private court banqueting.

2.2 Significance of the Royal Clothing in Assyrian Imperial Ideology

The use of the royal clothing in Assyria is informative as regards the significance attributed to them in royal ideology. To judge from Neo-Assyrian royal iconography, the basic elements of the royal attire remain essentially the same throughout the reigns, although important innovations emerge in certain periods. The adoption of the predecessors’ dress must have been an integral part of the new ruler’s legitimization strategy.[77] The unaltered continuity of Assyrian kingship through the royal generations found expression through the full adherence to the dress code of the royal tradition of the past, thus meeting the expectations of the more conservative elements of the Assyrian elite. The introduction of innovative features that expressed the cultural identity of new groups within the elite did not substantially alter the ruler’s overall attire, but enriched it with new meanings. That the king’s clothes embodied the royal office and its functions is evident from the ritual use of them as substitutes of the royal person in the execution of processions of gods’ statues,[78] in rites that implied interaction between the royal clothes and ritual tools,[79] and in which penitential chants aimed at obtaining the gods’ blessings in favour of the monarch were performed by the cultic singer on the king’s dress.[80] This ritual use is coherent with the Mesopotamian notion that garments were an extension of a person and its social role; as such, they were perceived as entities with an agentive role.[81] The agency of the king’s clothes is witnessed by activation rites that were performed on royal vestments and insignia with the aim of animating each royal object and, through them, enabling the wearer to acquire the dignity and functions of the royal office.[82] As an extension of personhood, possessing royal clothes belonging to the wardrobes of submitted rulers must have been of great significance for the Assyrian king’s claim of universalistic power. This substitutive and agentic use of royal clothes was also well established in Babylonia. Under Seleucid rule, the presentation of Nebuchadnezzar II’s robe to Antiochus III during his visit to Babylon in 187 BC is illustrative of how royal clothes were still seen by Babylonians as embodying the office of kingship and how, in the refiguration of Mesopotamian royal tradition by the Seleucids, possessing them may have helped the Graeco-Macedonian royal elite to legitimize their rule in Babylonia, presenting themselves as heirs of the Neo-Babylonian kings.[83]

As we read in royal inscriptions, high-class clothes with multicoloured trim and linen garments were among the wealthy booty regularly acquired by Assyrian troops during the plunder of the royal palaces of conquered kingdoms. Once carried to Assyria, these were redistributed among members of the royal family and high-ranking officials of the palace and the government sector, while others probably entered the treasuries of temples. One can suppose that these plundered foreign textiles and the textile craftsmen that were transferred from the enemy’s palace to Assyria represented precious sources of information in terms of materials, weaving and decorative techniques, and dress styles for the Assyrian artisans in charge of fabricating clothes for the king, the royal family and the palace elite. In all likelihood, these plundered elite clothes also included the dress items worn by the local ruler, as well as members of his family and court. Obtaining these high-quality products must have been another objective of the looting of enemy palaces. The royal clothes of foreign rulers symbolized the wealth, authority, and power of the defeated enemies and, as such, their appropriation by the victorious king of Assyria materialised the acquisition of the foreign king’s power into the Assyrian king’s universalistic power, thus implementing the extension of the divinely sanctioned ordered world. Once hoarded in Assyrian royal and elite residences in the major cities of central Assyria, these foreign artefacts continued to perpetuate the memory of the king’s triumph over the forces of chaos, fuelling new aesthetic tastes within the royal court and ruling class, and feeding competition for the possession of further textile products and other objects from those same enemy countries.

Two examples can be cited here of the appropriation of enemy royal clothing. In the inscriptions concerning Esarhaddon’s second campaign in Egypt (671 BC), mention is made of a garment of byssus which the Assyrian scribe, exceptionally, qualifies with the term šaddīnu, a specific designation that also occurs in administrative texts and that referred to an item of clothing of a fine quality of linen. This šaddīnu was found in Taharqa’s palace treasury in Memphis.[84] Other textiles looted by the Assyrians were innumerable choice linen robes (gadamāḫī lā nībi) and garments befitting the Kushite pharaoh’s dignity (ṣubāt bālti).[85] Further precious Kushite textiles were collected during Assurbanipal’s campaigns (667/66 and 664/63 BC) that led to the conquest and looting of Memphis and Thebes. As for the textiles from the Theban palace of Tanwetamani (Tanutamani), only two generic categories of textiles are mentioned in his inscriptions, without any specification: garments with polychromatic trims and linen clothes.[86]

In the wardrobe of the Nubian palatine elite, the Assyrians must have found a wide variety of high-quality linen clothes used by the pharaoh, members of his family, courtiers, and other high-ranking members of the Kushite royal elite. Kushite clothing of the 25th Dynasty was heavily characterized by adherence to Egyptian costumes, clearly due to assimilation to the Egyptian culture but also to the Kushite kings’ political agenda to present themselves as the legitimate heirs and proud defenders of that ancient and prestigious civilization. Consequently, representations of Kushite pharaohs as well as of high-ranking individuals of the Kushite elite show a new idiom in royal and elite dressing, marked by a revivalism of Egyptian costumes from the Old to New Kingdoms and by the addition of some ethnic features and innovations.[87] Among the items of clothing plundered by the Assyrian troops there were probably items peculiar to pharaonic clothing – revised according to the Kushite new style – and as such culturally distant from the conquerors’ dressing traditions and aesthetic sensibilities, such as the skirt with a frontal trapezoidal part (the shendjut), a royal prerogative throughout Egyptian history[88] and frequently represented in the statuary and other artworks portraying Taharqa,[89] the long kilt with a tasselled cord,[90] the short kilt decorated with rosettes,[91] the clasp straps,[92] the crossed-falcon shirt,[93] and the tightly fitting cap-crown,[94] as well as cloaks that were fastened with a knot at the right shoulder, such as the one worn by Tanwetamani in the painted decoration of the burial chamber at el-Kurru.[95] The trimmings mentioned in Assurbanipal’s texts probably refer to bands sewn onto the edges of Kushite elite tunics and garnished with tassels, cords with tassels,[96] or embroidered scenes with geometric or figurative motifs.[97]

The end of the civil war between Assyria and Babylonia (648 BC) and the defeat of the unfaithful brother and king of Babylonia Šamaš-šumu-ukīn represent another context in which textiles act as representative of royal personhood and power. These events were ceremonially sanctioned by Assurbanipal in a triumphal procession before the Assyrian king through the parade of all the royal appurtenances of the hostile brother that were carried off to Assyria. The precious objects, emblems of the Babylonian kingship that were plundered from his royal palace, included Šamaš-šumu-ukīn’s royal clothing, jewellery, and other regalia.[98]

The parade of the defeated brother’s regalia, sculpted in Room M of the North Palace, opens with a royal tiara, apparently Babylonian in style.[99] The message that these insignia of kingship communicate is clear: no longer integral parts of a unity (the Babylonian king’s clothed body, the “image of kingship”), but separate individual objects, they are now devoid of all power and become trophies glorifying the Assyrian king’s victory. Šamaš-šumu-ukīn’s royal clothing was presumably fashioned according to Babylonian clothing tradition and in line with the less richly ornamented costumes of Neo-Babylonian kings.[100] The spectacularization of victory thus found its decisive moment in the display of the enemy king’s regalia and clothes to the Assyrian public.[101]

In Assyria, royal dress materialises notions that we see at work in texts of political-religious communication and helped the ruling elite constructing the Assyrian king’s public appearance as the synthesis of the imperialistic project and the roles that he had to fulfil as the holder of Assyrian šarrūtu. Analogously to the standard titles that described the royal person and his functions in titulary sections of royal inscriptions, the components of the Assyrian king’s dress were aimed at illustrating the unrivalled qualities of the ruling king and responded to the imperatives of the divine mandate to rule the “Land of Aššur”. The royal titulary that the king “wore” on the occasion of public ceremonies highlighted his superior strength, vigour, and military capacity, his privileged status of appointee and chosen by the gods, and the god-inspired mission that informed his human rulership, the universality of his dominion. In few words, the royal dress with all its related accessories materialised the institution of Assyrian kingship and all its values, meanings, prerogatives, and functions, as well as the Assyrian elite’s expectations regarding the success of the imperialistic project in which they were involved. These functions of šarrūtu represented what the Assyrian imperial elite who lived in the major cities of central Assyria expected in terms of wealth, prestige, and power from the military expansion of the state. By covering the king’s body, these titles in the form of items of finely executed clothing enhanced the cosmic relevance of his earthly rulership, which re-enacted the gods’ combats against the chaos at the origin of the world and manifested how the king’s actions in war and peace continued the work of civilization inaugurated by his celestial counterparts in the mythical time. The way the royal items of clothing materialised the central ideas of Assyrian royal ideology and state religion probably varied according to the clothing ensemble worn by the king on the different occasions in which he took part, as well as to specific characteristics inherent to the textiles worn, such as colour combinations and decorative elements, not to mention the combination of items of clothing and accessories that expressed the royal dignity and power of the bearer.

The distinctive functions of the Assyrian king as vice-regent of the god Aššur, the true king of the country, and as chief priest of the supreme deity – two functions that were strictly intertwined with kingship in the Assyrian royal culture – were materially expressed through the characteristic truncated tiara with ribbons and the fringed overgarment or shawl. The tiara of the 9th century typology was a low, squat, fez-like cap with a pointed top adorned by only a frontal headband, while the 8th–7th centuries’ variety was taller and adorned with a headband and other decorative bands on both the headdress’ main part and the pointed top.[102] The later elongated variety probably resulted from combining the traditional squat, fez-like hat with the tall, conical headgear of priests as a reference to the king’s priestly office (sangûtu) and to the horned tiara of gods’ statues (agû), generally represented as a tall, cylindrical head covering with a pointed or rounded top. Among its meanings, the royal tiara evidently concretised the king’s role as high priest of Aššur, materialising his hierarchical position with respect to the god’s clergy. The ribbons occur as the characteristic ending part of headbands and tiaras. While the main part is plain, the ending is fringed. In some cases, the ribbon’s end is decorated by a border band bearing decorative motifs, possibly woven, and a fringe. As an alternative to fringes, ribbons can end in tassels. The tiara is a central element in the identification of the Assyrian ruler in his representations in imperial art and its visual elaboration is crucial to the message to be conveyed. In sculpted scenes, Assyrian artists evidently elongate this element of dress to make the figure of the sovereign appear taller, as well as more easily identifiable.[103] The shawl is another fundamental component of the king’s dress and of his official and public image: the monarch in his full majesty generally wears the shawl. This was a heavy overgarment that was worn differently from the stole or shawl used by princes and high dignitaries of the court. Visual depictions show that this item required a large quantity of fabric: evidently, the greater amount of fabric was itself an element that conveyed the higher status and power of the royal figure. It is unclear what determined its absence in some representations of palace reliefs, including those relating to rituals.[104] The covering of the sovereign’s shoulders perhaps also met ritual requirements[105] as well as royal protocol, but the available data do not allow any firm conclusions to be drawn on this.

The clothing ensemble consisting of tunic and shawl, both equipped with fringes, combined with the royal jewellery, the sceptre or the staff, and the ceremonial weapons, was fundamental in manifesting the king’s position vis-à-vis the closest palace entourage, the ruling elite and all his subjects. Moreover, his attire was intended to show himself as the one who, as a descendent of an ancient royal lineage and entrusted by the “great gods” (ilāni rabûti) of Assyria to expand the māt Aššur’s borders, was legitimized to rule the country. This project entailed the political mission of territorially enlarging Assyria and merged with the ideal of making the political borders of the state coincide with the extreme boundaries of the cosmos established by the gods. If the fringed and tasselled bands at the edges of the foot-length tunics were peculiar to the high-ranking members of the court, the robe worn by the king stood out from the others for the border bands, finely decorated with figural scenes, or by the interplay between a myriad of motifs scattered over the entire surface of the royal robe and those decorating the border bands and the tiara. The figural programme visible on Assurnaṣirpal II’s dress, elaborated by the expert royal tailors and decorators, shows how the king’s clothes were consciously understood as a medium of political communication. It is clear that analogously to iconography on jewels and other small-scale royal belongings,[106] figural scenes on the royal garments were only visible at a close distance. This suggests that their identity-building functions were directed to the wearer and to his closest entourage. In contrast, people who could only visually access the royal person at a remote distance would have had a more limited perception of his outfit, appreciating other traits of the royal lubussu, presumably shapes and colour combinations or the presence of elements that easily identify the wearer as a king, for example the tiara. This probably also affected the meanings that were conveyed to observers outside the king’s close entourage.

2.3 Dress Decorations as Materialisation of Key Concepts of Assyrian Royal Ideology

2.3.1 Assurnaṣirpal II’s Royal Dress

Royal robes play a leading role in the monumental art of the reliefs in the North-West Palace of Assurnaṣirpal II in Kalḫu, as shown by the numerous royal images characterised by extreme attention to garments’ details. However, it is difficult to believe that neither before nor after this king did the royal tailors not make richly ornamented robes for the rulers of Assyria. Much more likely is that only with Assurnaṣirpal II did the king’s dress become a central element in the construction and communication of the Assyrian state’s message of power, along with and in close relation to other media of imperial visual communication. The finely depicted decorations on Assurnaṣirpal II’s garments are preserved in some of the bas-reliefs from his royal residence.[107] Accurately incised on the stone of the carvings by the most talented artists, the finely embroidered scenes that decorated the king’s sumptuous garments were probably enhanced by the use of painting. This probably served as a means to give more visibility to these miniaturised motifs and to show the unrivalled richness of the royal outfit.[108] As much as Assurnaṣirpal II’s robes depicted in the reliefs contribute to the construction of an idealised image of the royal figure and the robes themselves may have been rendered by the artists in an idealised manner, they remain an important source of information on the royal attire of this period. In fact, the absence of organic remains of Neo-Assyrian decorated royal robes makes it impossible to know how realistic the depictions of dress decorations in the palace reliefs are or how much they diverge from reality, either for reasons of practical difficulty in depicting them on stone or because of stylistic choices and the message to be conveyed to the viewer. Whatever was the reality of the decorations on the royal dress, these decorations are not only revelatory of the textile art and aesthetic taste of this king (and perhaps also of other kings of Assyria who did not leave us detailed visual information on their dress). They also tell us how the king of Assyria was expected to dress and appear, and constitute important vehicles of meanings relating to the king’s image and the ideology that it embodied.

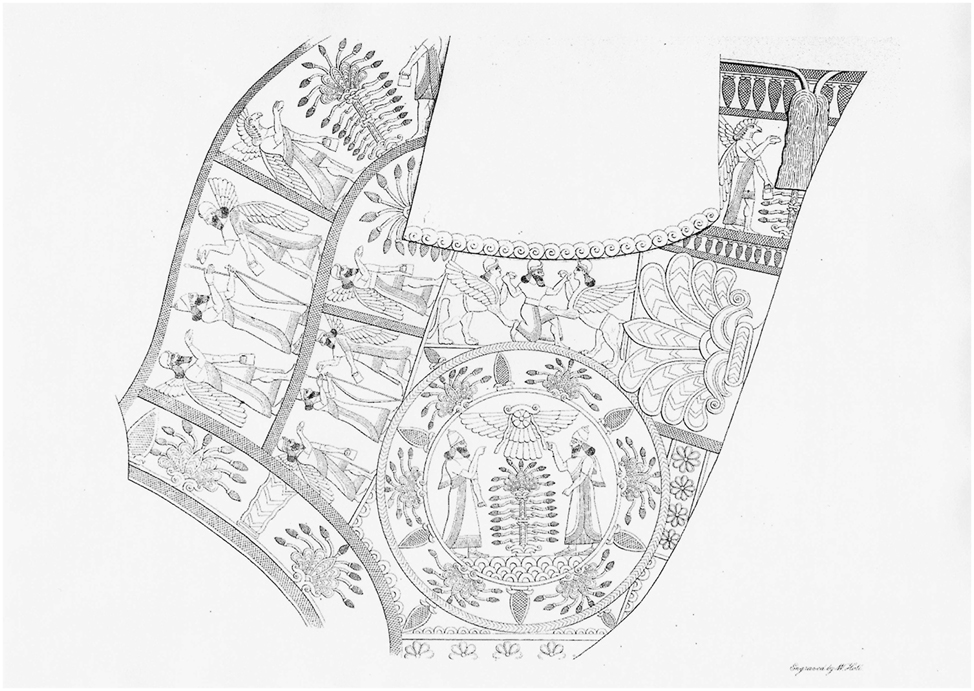

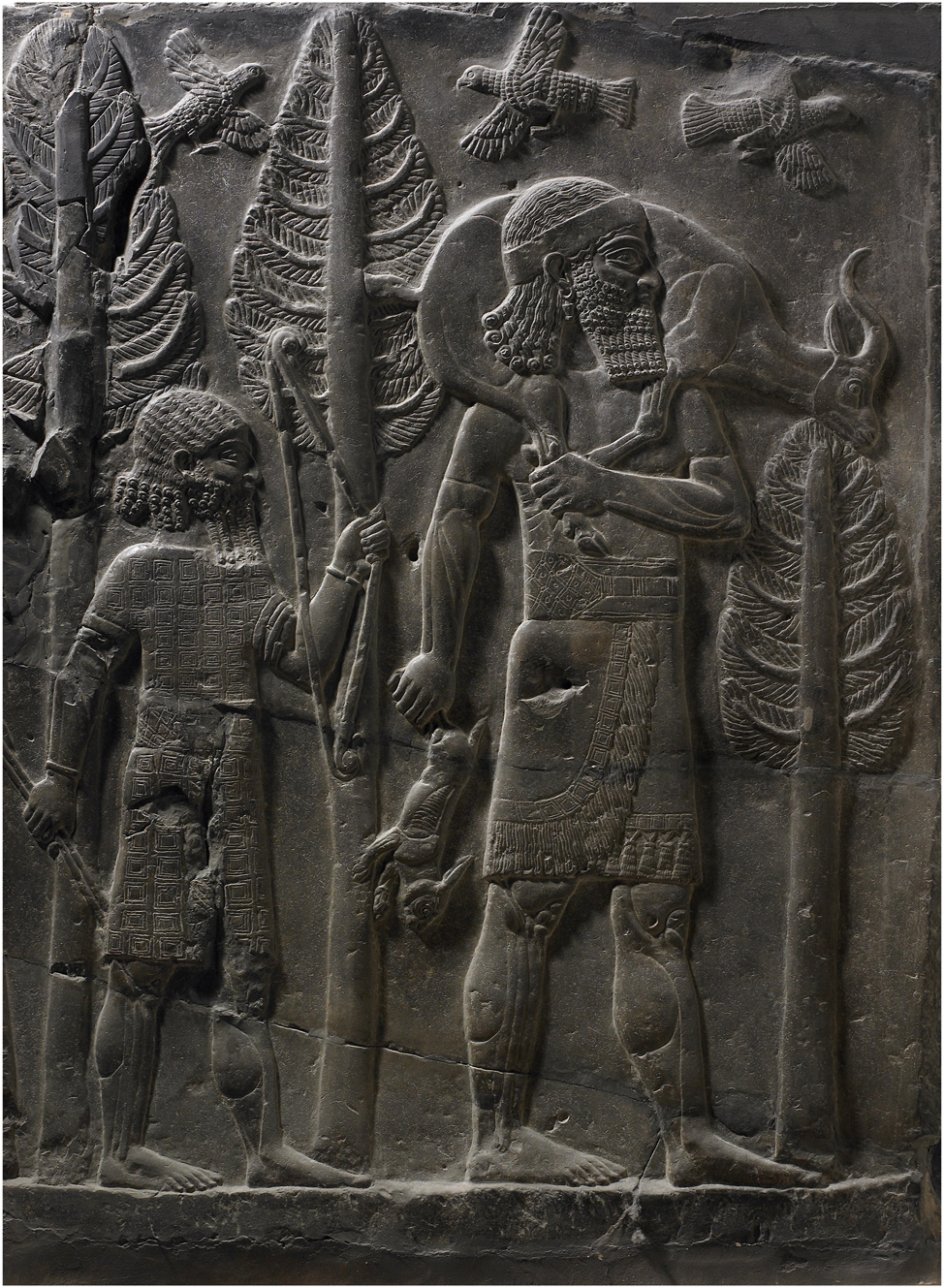

These decorations could consist of isolated motifs freely spread over the garment’s cloth and of patterned bands with continuous sequences of motifs, generally of figural, geometrical, or floral type. These bands were presumably woven separately and stitched onto the main cloth of the garment, principally onto the edges (the collar, sleeves, and edge of the tunic; the tiara; and the ribbons). In the case of the edges of the overgarment and the tunic, the band with the decorative motifs was attached to that bearing the fringes or the tassels. Alternatively, a single band with both decorations and fringes or tassels could be sewn to the dress. Also the ending part of the ribbons was adorned by stitching a decorative band. In this connection, it is worth noting that the figural scenes of winged heroes wrestling with wild or supernatural beasts, of the double royal person facing the “sacred tree”, of Aššur’s winged symbol, of protective genii with lamassus, and vegetal motifs of palmettes, flowers, and buds are abundant in the textile art evidenced by Assurnaṣirpal II’s outfit (Figure 1).[109]

A beardless lamassu grasped by a winged protective genius on the royal garment’s border band, Room G, North-West Palace, Nimrud (BM 124567, © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved).

Hunting and wrestling scenes symbolized masculine vigour and strength and were prerequisites for a successful king, as they recalled the royal obligation to defeat disruptive forces and expand the cosmic and civilizing order of the gods over the world as the human counterpart of Ninurta.[110] Royal hunts constituted the arena where the king’s function as protector of the “Land of Aššur” and the divinely sanctioned cosmic order was expressed and spectacularized.[111] These themes concur with the iconographical programme carved in the palace rooms to exalt the unrivalled heroism, strength, and military abilities of Assurnaṣirpal II. As for the vegetal motifs, these elements do not speak the language of war and the king’s unrivalled martial skills, but that of peacetime and construction. They probably referred to the prosperity of the country and the generative capacity of the Assyrian sovereign in the service of the state: the Land benefitted from the territorial expansion and agricultural exploitation of previously unproductive foreign lands resulting from the king’s warlike endeavours. The creational and generative abilities of the king were especially manifested through the construction of capital cities,[112] royal residences, and temples as centres of wealth hoarding and seats of unrivalled power, as well as of hydraulic infrastructures for the enhancement of palace gardens and the agricultural productivity of Assyria’s heartland.

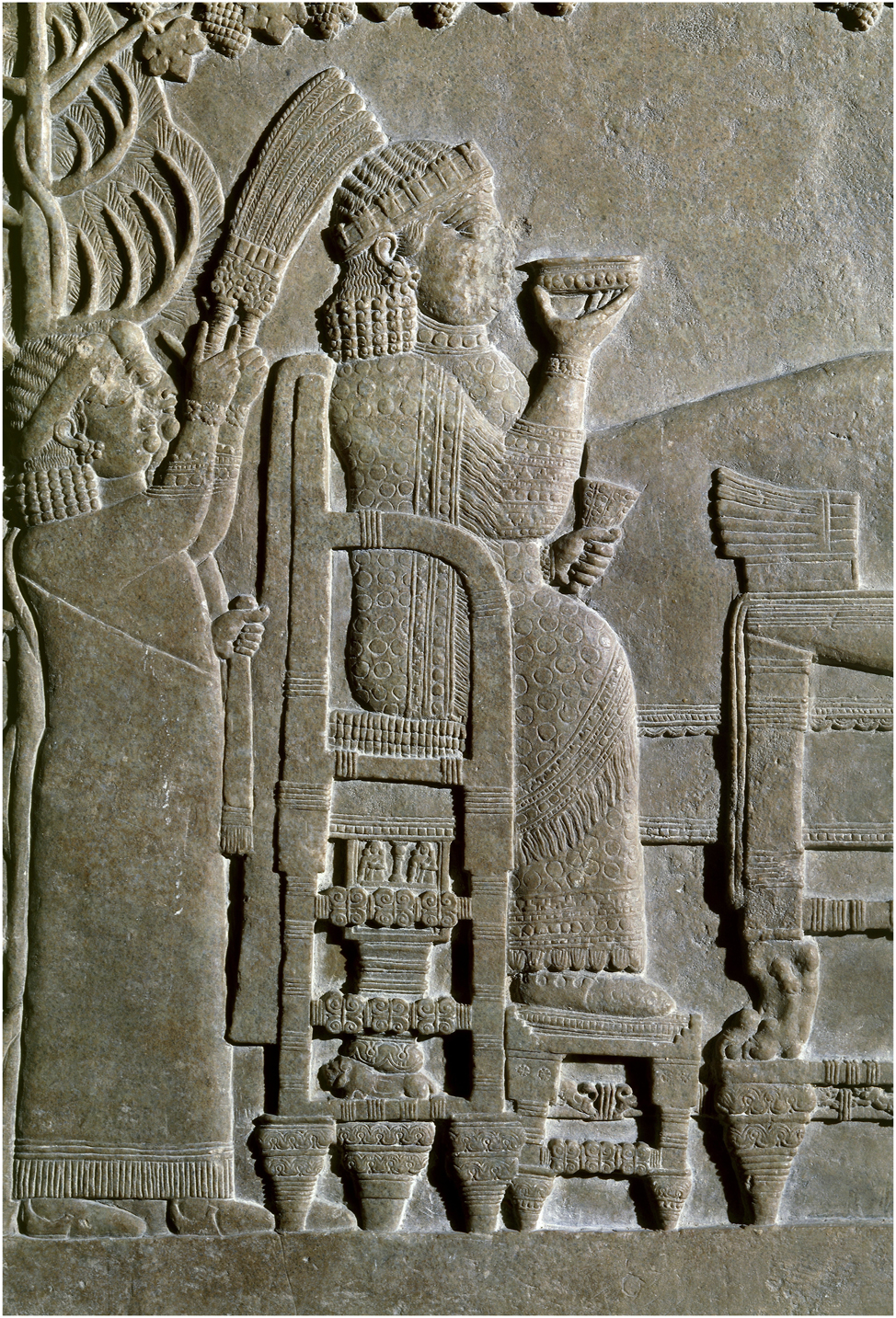

Among the vegetal motifs, that of the “Assyrian sacred tree” is central, since it is represented both as an individual motif among various motifs in sequence on decorative bands and as the main decoration of the chest part of the tunic. The sacred tree motif may occur on the chest area of Assurnaṣirpal II’s costume in a stylized form in horizontal position[113] or in a more complex design. In the case of Assurnaṣirpal II’s sitting figure of Reliefs 2–3 of Room G (Figure 2), the scene portraying the double royal figure facing the “sacred tree” under Aššur’s emblem and holding the streamers of the disc-shaped emblem on the chest part is encircled within a band formed by a row of buds and palmettes (Figure 3).[114]

Assurnaṣirpal II sitting with a bowl of wine among attendants, Room G, North-West Palace, Nimrud (BM 124565, © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved).

Decoration of the chest area of Assurnaṣirpal II’s dress from Layard 1849–53, I: pl. 6.

It cannot be ruled out that the artist deliberately enlarged and accentuated the chest decoration compared to how it must have appeared in reality on the king’s dress, in order to make the iconographic motif and the message it embodied more visible to the viewer.[115] The centrality of the “sacred tree” motif in the artistic and architectural programme of the North-West Palace explains its presence also in the royal dress. In the bas-reliefs of the North-West Palace the “sacred tree” is represented in isolation or in scenes in which the king is depicted twice on either side of the tree.[116] The latter motif may have been inspired by a royal ritual that was performed near a real object resembling a palm tree,[117] but in Assurnaṣirpal II’s artistic programme it becomes a component of an idealised representation of the royal figure that combines the mythical and historical, the divine and human dimensions.[118] In the Throne Room’s decoration, the scene with the doubling of the king’s body flanking the “sacred tree”[119] attracted the visitor’s attention as the main focal point of the sequence of the sculpted images of this space. The two figures are not perfectly symmetrical, as shown by the different way in which the shawl is worn. The same can be observed in the scene reproduced in the chest decoration of the royal tunic of Room G.[120] However, whereas in the Throne Room the shawl spirally wraps around the body of the royal figure on the right more than once and entirely covers the left arm,[121] in the decoration of the tunic the shawl worn by the king on the right side leaves the left arm uncovered and covers the tunic at length with the two flaps almost entirely. In the scene, the different way of wearing the royal shawl is determined by the king’s different position (in physical/ritual and ideal/religious terms) in relation to the tree and the divine symbol. The different representation of the shawl seems to have been instrumental in highlighting the meaning of the “sacred tree” scene, certainly consistent with the message that the decoration of the Throne Room expressed.[122]

This motif as a decoration of the tunic’s chest area will not disappear in the textile art of the late Neo-Assyrian period, as we shall see below. In addition, the chest area of Assurnaṣirpal II’s costume is predominantly enriched by repeated series of figural scenes, with a minor role played by garlands of palmettes, pinecones, and stylized flowers. Narrow bands of small rosettes also occur on the chest, while in the end part of the ribbons the band with rosettes occurs between a band with a rectangular motif and the tassels. It is also worth noting how in Assurnaṣirpal II’s reliefs the artists intend to greatly emphasise the chest area of the king’s body. By rotating the torso towards the viewer, the profile of the shoulders and chest are shown in all their mass and vigour, resulting in accentuating the masculine features, but also highlighting the decoration of the dress and, presumably, its meanings. In terms of gender construction of the royal body, it is clear that this way of representing the king’s body masculinises his otherwise completely covered and uniformly compact figure.[123] But this artistic solution also shows how the textile language plays a crucial role in the re-definition of the corporal vocabulary of the Assyrian kings in imperial art. If the represented body is shown completely covered, powerful in its solid mass and impenetrable in its physicality,[124] it is on the details of the dress, the decoration and the accessories that the royal image invites the spectator’s gaze. The viewer’s gaze is invited to read the visual narrative unfolding along the sovereign’s robes and to identify the web of interconnections with the message conveyed by the sculpted panels in the palatine rooms.

The basic decoration on Neo-Assyrian royal ribbons is given by a band with a rosette (or a square-shaped element with an internal rosette), accompanied by a fringed ending, as can be seen in the stele of Šamšī-Adad V[125] and in the Khorsabad reliefs depicting Sargon II and the crown prince.[126] Rows of small-shaped elements occur in two bands that adorn the middle part and the fringed ending of ribbons of Sennacherib’s tiara in the scene regarding the booty from Lachish.[127] The same decoration also occurs in the ribbons of the crown prince’s headband depicted in the same scene. In the stele from Sam’al, both Esarhaddon and Crown Prince Assurbanipal show fringed ribbons with an ending part adorned with small discs.[128] The number of these decorative bands probably constituted another marker of status. In fact, it is interesting to observe that on the ribbons of the king’s headdress there are two bands with discs, while on those of Assurbanipal’s headband there is only one.

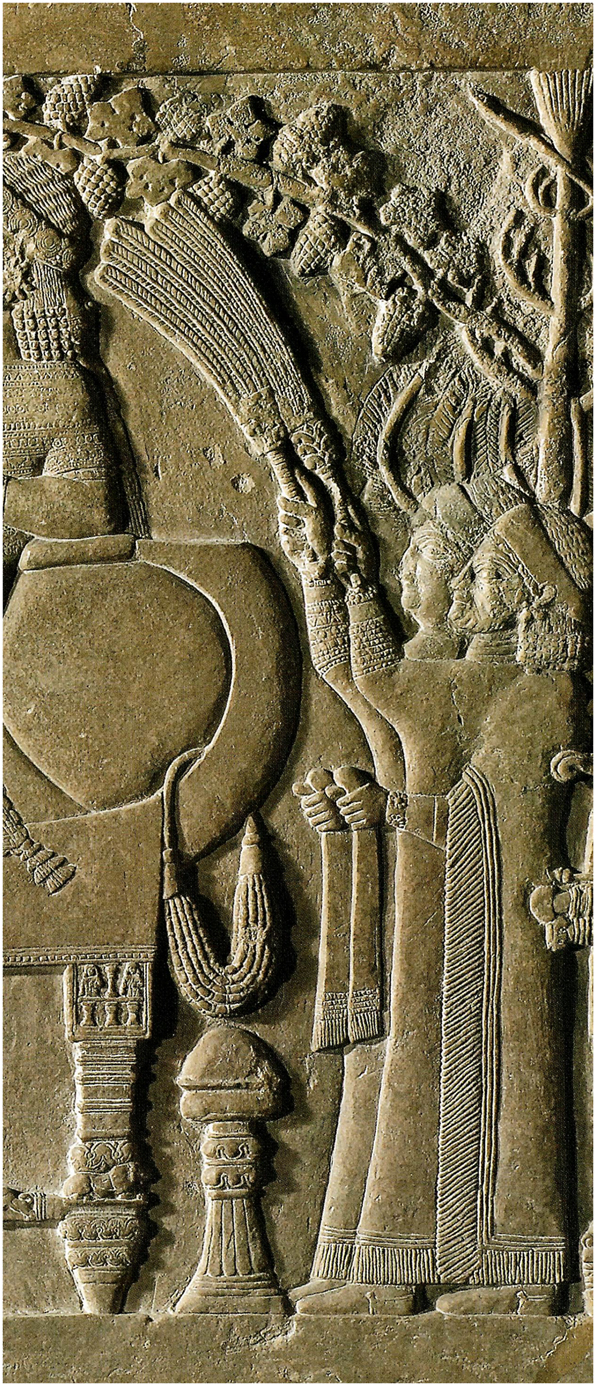

To come back to Assurnaṣirpal II’s dress, the figural scenes that occur as decoration in ceremonial garments related to specific occasions of the royal presence at court and in ritual contexts[129] were inserted within bands that adorned the fringed borders of the tunic and the shawl and the upper part of the tunic, that is to say the chest area and the shoulders. The most complex figural motifs only occur in specific reliefs of the iconographical programme of the North-West Palace. This suggests a connection between the high degree of realism in the representation of the royal clothes and the ceremonial functions of certain rooms, as in the case of Room G, where the carved royal clothes are extensively decorated with such scenes and the royal drinking seems to be ritually connoted.[130] The limitation of highly decorated garments to specific reliefs in the figurative programme seems to suggest that these representations played the role of focal points of the narrative cycle in relation to other scenes and were aimed at presenting to the spectator the king in his full majesty. Hence the greater emphasis on the depiction of decorative details in the garments. However, it is surprising that no such complex figural decorations appear on the royal clothes represented in Throne Room B, where the preference of the artists (and of the king that commissioned the work) was oriented to geometrical decorations.[131] In recalling analogous motifs on the garments worn by genii and in other representations carved on the stone wall panels of the North-West Palace in Nimrud, the royal dress shows how the king’s political message of unrivalled dominion was spread through different visual media that worked as single but complementary components of an integrated visual communication system. By reiterating motifs that were disseminated through different communication media of visual art, on ceremonial occasions the narratives of power “worn” by the king helped to establish a continuous dialogue between the decorated robes and the sculpted halls of the palace. These narratives on the royal dress also shifted the message of power from the static dimension of monumental art to the movable, dynamic, and living dimension of the royal person and his gestures in everyday situations. However, the repertoire of the above-described figural motifs was not systematically applied to all the garments worn by the king. Specific occasions must have dictated the use of clothes on which figural scenes were reduced to a minimum, while a central position was given to certain motifs; for instance, the “Assyrian sacred tree”. This motif, possibly on account of its meaning in the Assyrian royal ideology, occurs both on the chest part and on the shoulders. The standing royal figure carved in Relief 3 of Room S in Assurnaṣirpal II’s palace[132] represents another piece of evidence regarding the most complex figural motifs of the royal dress and, as in the case of Room G, raises the question about the specific function of this place in the palace, possibly a reception room functioning as part of the king’s residential suite.[133] Room S must have been a protected environment, as the overabundant figures of genii and “sacred trees” and the unique portrait of the sovereign at the end of the room would prove.[134] For those entering this space, the royal image at the end of the room certainly constituted the focal point.[135] This relief shows an extremely refined decoration on the tunic in which rows of rosettes, lotuses, pinecones or buds, and palmettes are central, while rows of rosettes and a garland formed by palmettes, pinecones (or buds), and what appear to be lilies[136] feature on the overgarment (Figure 4).

Assurnaṣirpal II’s royal dress from Layard 1849–53, I: pl. 34.

The ending part of the tiara’s ribbons show a narrow, chequered band and tassels. The centrality of the stylized “sacred tree” is evident from its large size and the position in the royal dress: it is represented in horizontal position on the chest part and as a vertical motif on the left sleeve. The figural motifs occur on the sleeves and on the overgarment; a procession of human figures is portrayed on the lower part of the overgarment between a series of opposing half-circles and a chequered band, while a sequence of wild goats adorn the border band of the left short sleeve, surmounted by a narrow band with rosettes. Bartl’s reconstruction of the figural decoration on the overgarment’s lower part shows that it represented the king in a standing position with bow and arrows and accompanied by an attendant, in the act of receiving a procession of high-ranking figures paying homage to him and presumably introducing submitted enemies and tribute-bearers from conquered countries.[137] An analogous audience scene is displayed on the western side of the Throne Room façade[138] and it cannot be excluded that the reference to the same motif of the Throne Room is an indication of the function for which Room S was intended,[139] namely to host receptions of selected groups of high-ranking personalities. The motif frequently occurs in war narratives of royal inscriptions and in monumental art and pertains to the king’s ability to channel goods in the form of gifts, tribute, or booty, but certainly also via trade, from conquered countries.[140] In addition, the wide, fringed border of the overgarment is embellished by a double sequence of rosettes or other vegetal motifs within square-shaped elements, delimited by narrow, grid-shaped bands.[141] Partially covered by the overgarment, the tunic exhibits two main decorative bands: one is a knee-high band while the other characterizes the edge. In Layard’s drawing, the former is constituted by five narrow bands with, from top to bottom, sequences of lilies and palmettes, rosettes, two opposing rows of half-circles, and palmettes and rosettes again, while the latter shows, from top to bottom, a double series of rosettes, a grid-shaped band, a row of lilies, and a large garland of palmettes and pinecones (or buds), closed by the tassels. However, from Bartl’s reconstruction, the bands adorning the tunic’s lower part seem to contain rows of concentric half-circles and rhomboidal elements, opposing palmettes, a separating grid band, opposing buds and lilies, and a bull-hunting scene with mounted soldiers, infantrymen, and the king on his war chariot, closed by various vegetal motifs and surmounted by astralized divine symbols.[142]

To return to the possible function of the rooms in which the most detailed depictions of Assurnaṣirpal II’s decorated clothes occur, it is reasonable to think that the spatial context in which these royal images were inserted had to meet the aesthetic and ideological expectations of the king and the royal elite, and those pertaining to the performance of specific ceremonial or ritual events aimed at constructing and making explicit the role of the sovereign. When the king is portrayed in mythical-symbolic scenes, he is represented as encountering the divine world but not being completely absorbed by it.[143] His physical features, emphasised by sumptuous and richly ornamented robes, accessories, weapons and royalty insignia, show him as perfect, imbued with divine attributes, and irradiating an awe-inspiring and powerful aura. His close association with the purifying genii in the scenes also establishes a relationship between his clothing and those worn by the apkallus, both richly ornamented to signal the king’s special closeness to the divine world. If rites were performed in these rooms, they were probably aimed at purifying his body, insignia and clothes.[144] To this aim, the royal images were probably intended to illustrate the necessary ritual steps to achieve perfection and enable the monarch to fully exercise his functions of power.[145] In this regard, one wonders whether the different way of depicting the royal shawl may have played a role in instructing the sovereign on how to wear it at different stages of the ritual. In all likelihood, a restricted number of viewers were admitted in these rooms as participants in the royal rites; they represented a privileged and internal audience.[146] In the eyes of these internal spectators, some of which were presumably ritual operators, the images of the king among apkallus would have confirmed the crucial role of the ritual experts in the imperial project and specifically in guiding, purifying and protecting the royal figure.[147] The attention of those who were admitted to the Throne Room would have been directed towards the portraits of the king in the scenes between genii and “sacred trees”, focal moments of the decorative cycle of the sculpted wall panels and probably capable of inspiring an effect of calm and equilibrium in visitors.[148] Other portraits of the sovereign occur in limited points of the palace and show him in his benevolent and reassuring role of shepherd with the royal staff, aimed at blessing the visitors on their way to other parts of the palace[149] or acting as focal point in otherwise homogeneously decorated spaces, access to which was probably limited to a few visitors of higher rank, as assumed in the case of Room S.[150] The intended addressees of these portraits of the king in his pastoral duties are unknown, but they could have been members of the administrative and political staff, thus an internal audience.[151] Moreover, the sensorial experience of these royal images and details of the king’s robes in viewers may have been intentionally conditioned depending on the ceremonial occasion and the visitors admitted. It cannot be ruled out that the amount of light inside the palace rooms was intentionally manipulated to highlight the images of the king at focal points in the decorative cycle of the reliefs and to emphasise decorative details,[152] such as those with figural scenes on the royal robes.

2.3.2 The Sargonid Royal Dress