Abstract

Aim of the present work is to offer an understanding of the mechanisms informing the making and reproduction of the Hittite Empire (17th-13th BCE) in its diachronic evolution. The analysis focuses on South-Central Anatolia, an area of intense core-periphery interactions within the scope of the Hittite domain and, therefore, of great informative potential about the manifold trajectories of imperial action. Through the combinatory investigation of archaeological and textual data able to account for long- to short-term variables of social change, I will show that South-Central Anatolia evolved from being a loose agglomerate of city-hinterland nuclei into a provincial system. The region thus acquired a pivotal role in the balance of power thanks to its centrality in the communication network, and it became the stage for eventful political revolutions, as well as a new core for Hittite political dynamics. The picture of Hittite imperialism emerging, thus, is that of a set of multi-causal and multi-directional processes, not predicated on the sole centrifugal hegemonic expansion of the empire.

1 Political geographies of the Hittite Empire

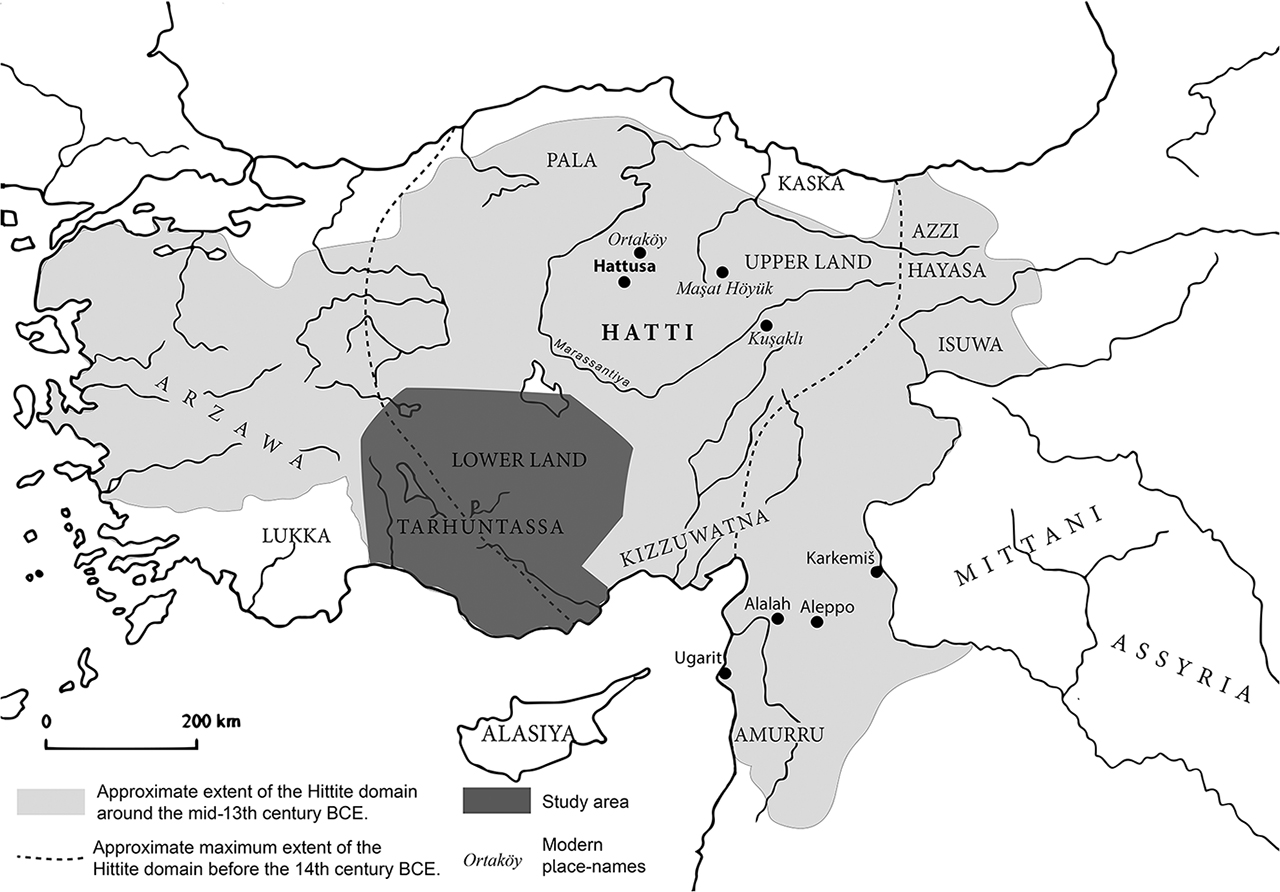

Hittite history spans the entire Late Bronze Age in Anatolia, covering approximately four and a half centuries (ca. 1650–1200 BCE). At the beginning of this period, the Hittite state emerged in North-Central Anatolia, in the bend of the Kızıl Irmak, from a mosaic of canton polities occupying the area during the Middle Bronze Age. A first phase of Hittite history, termed the Old Kingdom (seventeenth-sixteenth century BCE), saw the Hittite rulers gaining supremacy in Anatolia, gradually and with alternating success. In the following phase, termed the Empire period (fifteenth-thirteenth century BCE), the Hittites acquired considerable geopolitical prestige by expanding their hegemony over much of Western Anatolia, the Northern Levant and parts of Upper Mesopotamia, while entertaining contacts on equal terms with great powers of the Eastern Mediterranean, such as Egypt, Assyria and the Mycenaean world (Figure 1). [1]

The Hittite world, with highlight of the present study area. Graphics by Alvise Matessi.

As in much of the historical work on the Hittites, research on the spatial outcomes of Hittite imperial policies has chiefly relied upon information deriving from the myriad cuneiform tablets found at the Hittite capital—Hattusa/Boğazköy—and at other important findspots in Anatolia and Syria. In particular, studies on the Hittite political geography have evidenced that, by the mid-fourteenth century BCE, the Hittite Empire was structured in different tiers of integration fitting into a sort of “territorial-hegemonic continuum”. [2] On the one end of the continuum there was Hatti, the Hittite core region located in North-Central Anatolia, which was directly dependent on the Hittite central authority. The opposite end, instead, included a series of client states in Syria and Western Anatolia, governed by subordinate rulers, called ‘kings’ or even ‘small kings,’ as opposed to the Hittite Great Kings residing in Hattusa. Several situations floated in between these two poles, with specific formulations depending on the means by which polities were integrated into the Hittite domain (Altman 2003). Examples of such intermediate tiers are the appanage states of Karkemiš, in northern Syria, and, as we shall see, Tarhuntassa, in South-Central Anatolia. These were vice-regal kingdoms governed by direct offspring of the Hittite royal family, who enjoyed a special position in the Hittite state hierarchy, often playing as intermediaries between the Great Kings and subordinate client rulers.

Recent archaeological research has provided ground for a bottom-up approach to the socio-spatial layout of the Hittite domain able to complement or refine text-based perspectives (Glatz 2009; Schachner 2009; 2011; Manuelli 2013: 355–423). In particular, Glatz’s article proposes a synthesis explicitly challenging text-based reconstructions of the Hittite geography of power grounding upon a selection of four archaeological categories, taken as proxies for different spheres of interaction between core and periphery: settlement trends; ‘Hittite’ or, in Glatz’s own terms, “North-Central Anatolian-style” (NCA-style) pottery; administrative tools—chiefly “NCA-style” glyptic; and landscape monuments. This selection is based on the assumption that each category reflects a particular network of spatial interactions relevant to the construction of imperial relationships. For instance, “landscape monuments are projections of centralized power and claims over territories” while settlement dynamics “allow us to detect changes in the socio-political organization” (Glatz 2009: 136 and 129). [3] Glatz reconstructs a pattern of overlapping spheres of spatial control, ranging from intensive territorial integration to hegemonic and ephemeral control.

The spatial model resulting from Glatz’s analysis refines our resolution on the Hittite geography of power, emphasizing multiple dimensions otherwise escaping an uncritical reading of extant textual sources. However, both the philologically and the archaeologically informed perspectives on the Hittite political geography devote only a limited attention to the actual spatial workings of Hittite imperialism. [4] Following current definitions (Doyle 1986: 45; Sinopoli 1994: 160), imperialism is the set of mechanisms informing the making and reproduction of empires. A focus on Hittite imperialism, therefore, would require a diachronic rather than structural approach to the spatiality of the Hittite Empire. Text-based reconstructions of the Hittite political geography mostly reflect the cumulative spatial result of imperial action as seen through the lens of fourteenth and thirteenth century BCE sources that admittedly represent the bulk of the extant Hittite written legacy. The outcome, therefore, is a palimpsest picture that overshadows formative and transformative processes. Also Glatz’s archaeological synthesis has a limit in the same static outcome, as it suffers from the lack of temporal depth. This is determined, indeed, by the very archaeological proxies informing Glatz’s work. In particular, the diachronic evolution of Late Bronze Age ceramic assemblages has been thoroughly investigated only in a few sites, which makes pottery an inadequate tool for a clear-cut definition of cultural phases within the period of Hittite rule in Anatolia (Schoop 2006; 2011; Manuelli 2013). This problem imposes a burden especially on the analysis of cross-regional settlement trends, for which relevant data mostly derive from archaeological surveys that is, in large part, from unstratified pottery collections. As to the Hittite monuments, iconographic details and, in several cases, inscriptions in the so-called Anatolian Hieroglyphic enable us to establish better connections between the formation of given archaeological landscapes and short-term political developments. However, all known artifacts of this kind were produced during quite a limited time-span (late fourteenth-thirteenth century BCE: Ehringhaus 2005), when the Hittite Empire was already at its apogee or even declining. Finally, when it comes to Anatolian glyptic traditions, the limited number and the scattered spatial and chronological distribution of related finds do not provide solid ground for an association with long- and short-term processes of imperial construction (Mora 1987; Herbordt 2006). In sum, while current understandings of the Hittite political geography, when adequately crosschecked with one another, produce a valid palimpsest of the spatial structure of the Hittite empire they account very little for formative and transformative processes.

Even when the spatial outcomes of Hittite imperial policies are analyzed in a diachronic overview there is a tendency to interpret textual sources from a Hatti-centric perspective. [5] This induces to an understanding of the Hittite territorial expansion that telescopes centrifugal processes to the detriment of dialectic interactions. Similarly, Glatz’s work, as well as other strands of archaeological research of the past decades (e. g. Gorny 1995; Schachner 2011), mostly concentrates on local receptions across the Hittite domain of movements originated in the Hittite heartland. However, imperialism may be conceptualized as a large-scale process whose motor does not reside only in an expansive core, but also in the peripheries that directly or indirectly contribute to significant transformations within the core itself. [6] Even though stances of cultural resistance and continuity at the margins of the Empire are being more and more emphasized (e. g. MacSweeney 2010; Manuelli 2013), few attempts have been made so far in order to understand how different trajectories of socio-cultural interaction have contributed to shape the Hittite imperial landscape.

In the attempt to cope with these theoretical premises, this paper aims to offer a view on dynamic processes informing the making and reproduction of the Hittite Empire and on the manifold variables that were involved. A focus on South-Central Anatolia grants considerable advantage to this approach for two reasons. Firstly, relationships between the Hittite central authorities and the geopolitical entities of South-Central Anatolia are quite well documented in extant written sources throughout the period of Hittite rule. Secondly, as I will emphasize, South-Central Anatolia occupied a geographic position halfway between the core and the south and west peripheries of the Hittite Empire, and, consequently, its socio-spatial networks were heavily impacted by the multiple trajectories of imperialism. The patterns of social interaction that can be inferred from the combination of these two factors may become an intriguing subject of investigation from both a spatial and diachronic perspective. Anthropological and archaeological critique of the past decades provides important conceptual tools for such a spatially and temporally dynamic approach, promoting, from different angles, the combinatory investigation of multiple datasets, able to account for variables operating at different time scales (e. g. Bintliff 1991; 2004; B. Parker 2001; Smith 2003; VanValkenbourg and Osborne 2012). In this purview, this article will draw conclusions based on both the discussion of regional data on the Late Bronze Age archaeological landscapes of South-Central Anatolia and the interpretation of geopolitical information derived from relevant written sources. While archaeological datasets are especially useful for a view on long- and mid-term variables of socio-cultural interaction, I will rely upon textual data in order to obtain the chronological resolution necessary to examine short-term processes of geopolitical change.

2 South-Central Anatolia: geographic definition

The geographic extension of South-Central Anatolia in this paper is defined, clockwise from the north, by the Salt Lake, the volcanic group Hasan-Melendiz, the Central Taurus, the Mediterranean Sea and the Eğridir lake. Far from being homogeneous, this area, rather, is composed by a variety of landscapes, which heavily impacted the development of human settlement through time.

An inner continental area is represented by the Konya plain, a marl plateau (ca. 1000 masl) extending for ca. 10,000 km2. Its main hydrological feature is the Çarşamba river, which springs from the Şugla lake basin and spreads into an endorheic delta to the east of Konya. A karst basin originating from the Taurus mountains flows northward beneath the plateau to feed the Salt Lake, a shallow hypersaline water body extending for no less than 3000 km2. Low precipitation rates (ca. 300 ml per year) prevent rain fed agriculture from flourishing in the Konya plain, so that, before the introduction of mechanical water pumping systems, local populations mostly depended on dry-farming and the herding of sheep, goat and cattle in the steppe pasturelands. Large areas of this kind, such as the Obruk Yaylası, extending south of the Salt Lake, are almost completely lacking in settlements. On the contrary, irrigated farming, supported by modern canalization works, sustains a denser population in the Çarşamba floodplain.

The Karadağ, the Karacadağ and the Hasan-Melendiz complex form a paleo-volcanic region rising at the eastern fringes of the Konya plain. These marked outcrops today host a poor vegetation but are patched by modest woods as well as by orchards of local villagers in proximity to watercourses. Moreover, water flowing close to the surface at the mountain feet also allows cultivation, before drying up or sinking into the ground towards the centre of the plain. Fertile stretches of land are also found in the western appendices of the Konya basin, at the feet of the Sultan and Emir mountains and in the so-called Lake District, around the Beyşehir and Eğridir lakes.

South of the Hasan-Melendiz volcanic massif lies the Bor-Ereğli plain, an arid steppe surrounded by significant patches of lush vegetation in connection with alluvial deposits at the mountain feet. During the Holocene, due to climatic fluctuations, the Bor-Ereğli plain experienced a process of soil salinization alternating with the formation of small lakes and marshes. [7] In particular, during the Late Bronze Age, a former lake extending in the plain, west of Bor, evolved into a marsh, with further salinization of the soil (Gürel and Lermi 2010; d’Alfonso 2010).

Topography makes the Konya plain a formidable catchment of natural corridors, which contributed to growing cultural interactions since the later prehistory (Efe 2007). To the north, a major north-south axis leads to North-Central Anatolia through the Konaklı corridor, with an opening between the Melendiz and the Taurus mountains. The Sultan Dağ range, to the northwest, forms the ridge between two east-west corridors. The first, in Roman times hosting the via Sebaste, [8] runs parallel to the Taurus across the Lake District. The other corridor, now followed by the highway Konya-Afyonkarahisar, runs through the Akarçay valley between the Sultan Dağ and the Emir Dağ.

The Konya plain is fenced in to the south by the impervious mountain ranges of the Taurus. One of the main sub-groups of the Taurus chain is the Bolkar Dağ that rises up to 3500 masl at the southern edge of the Bor-Ereğli plain, thus forming a steep and almost impenetrable barrier. The only viable passage across the Bolkar Dağ was provided in the Roman period by the via Tauri, passing through the narrow gorge of the Cilician Gates. However, already during the prehistory and throughout the Bronze Age, the Cilician Gates functioned as an important link between the Anatolian plateau and the Eastern Mediterranean, as documented by archaeological and, when available, epigraphic evidence. [9] This ancient connection, today, is followed and heavily modified by the Aksaray-Adana route (D750), descending to Adana through the Gökoluk river valley. Westwards, in Rough Cilicia, the Taurus assumes a more rugged aspect. Here, a major topographical discontinuity is determined by the Göksu river, forming a broad valley along its central stream. Together with the Cilician Gates, the Göksu valley represents one of the few feasible passages through the Taurus towards the Mediterranean. It is nowadays accessed from the Konya plain through the Sertavul pass, between Karaman and Mut. [10]

3 Archaeological data

Political histories of early complex polities and empires, especially in the Ancient Near East, are increasingly making use of datasets deriving from archaeological surveys and excavations. In fact, while survey data provide compelling ground for understanding long-term patterns of socio-spatial integration on a regional scale, excavated sequences allow assessment with greater chronological resolution of the place-specific impact of socio-cultural transformations.

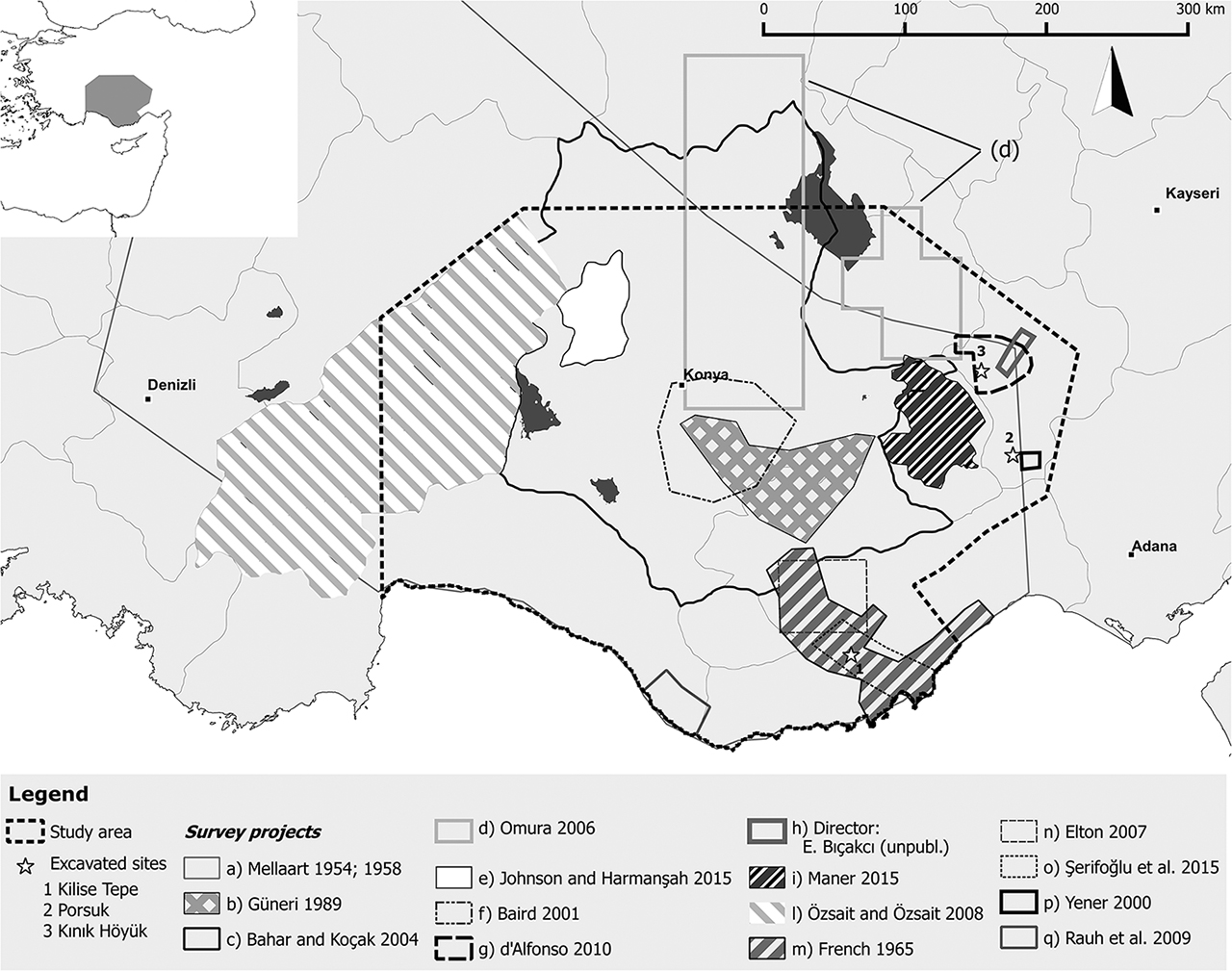

In contrast to North-Central Anatolia, where research on a growing number of Hittite sites is continuing since the first excavations started at Hattusa/Boğazköy more than one century ago, South-Central Anatolia has remained for a long time at the margins of Hittite archaeology. Still in 1986, the Konya plain and the central Taurus appeared as an almost empty space in the map of Hittite sites included in the Atlante Storico del Vicino Oriente (Forlanini and Marazzi 1986: Tav. I). Nonetheless, archaeological research in South-Central Anatolia has much improved over the past decades, with the joint contribution of numerous regional survey projects and excavations at key sites (Figure 2).

Archaeological research in South-Central Anatolia, with references to the most recent relevant publications. Map and graphics by Alvise Matessi.

3.1 Surveys

Pioneering extensive surveys by James Mellaart and David French in the 1950s and 1960s add up to entirely cover our study region, with the latter concentrated on the Göksu valley (Figure 2: a and m). Mellaart’s data on the Konya plain have been thoroughly complemented or revisited later by less extensive projects (Figure 2: b-l). The recent surveys of the Göksu Archaeological Project and the Lower Göksu Archaeological Salvage Survey followed French’s footsteps in the Göksu valley, focusing respectively on the upper and central stream(Figure 2: n-o). The Taurus uplands have been the object of only a few surveys interested in pre-classical remains: the Archaeology of Silver in Ancient Anatolia project, centered on the Bulgarmaden mining district, and the Rough Cilicia Archaeological Survey Project, covering the coastal cliffs between Alanya, Gazipaşa and Kaledran (Figure 2: p-q). These projects were quite intensive but of limited areal extension and, significantly, have yielded none or very meager evidence of 2nd millennium BCE occupation.

Before illustrating the combined results of these projects and their relevance to the present topic, a few notes must be reserved to the limits of their evidence. A first limit has general methodological implications, as it derives from the heterogeneity of the contributory projects plotted in the analysis, which may have an outcome of inaccurate evaluations of settlement patterns. In fact, distributed over the past 60 years, the surveys carried out in South-Central Anatolia differ a lot from each other in terms of their objectives, site classification criteria and methodologies. They vary from extensive explorations mostly aimed at site reconnaissance for all periods (Figure 2: c, d and i) or a selection thereof (Figure 2: a, b, l and m), to more intensive and specialized endeavors, engaged in interdisciplinary approaches with a view to targeting broad ranges of man-environment interactions (Figure 2: e-g, and n-q). [11] In addition, the contributory projects considered do not cover the entirety of the focused area, and major “no data” gaps concern the Taurus uplands and some locales of the northern plateau (Figure 3). [12]

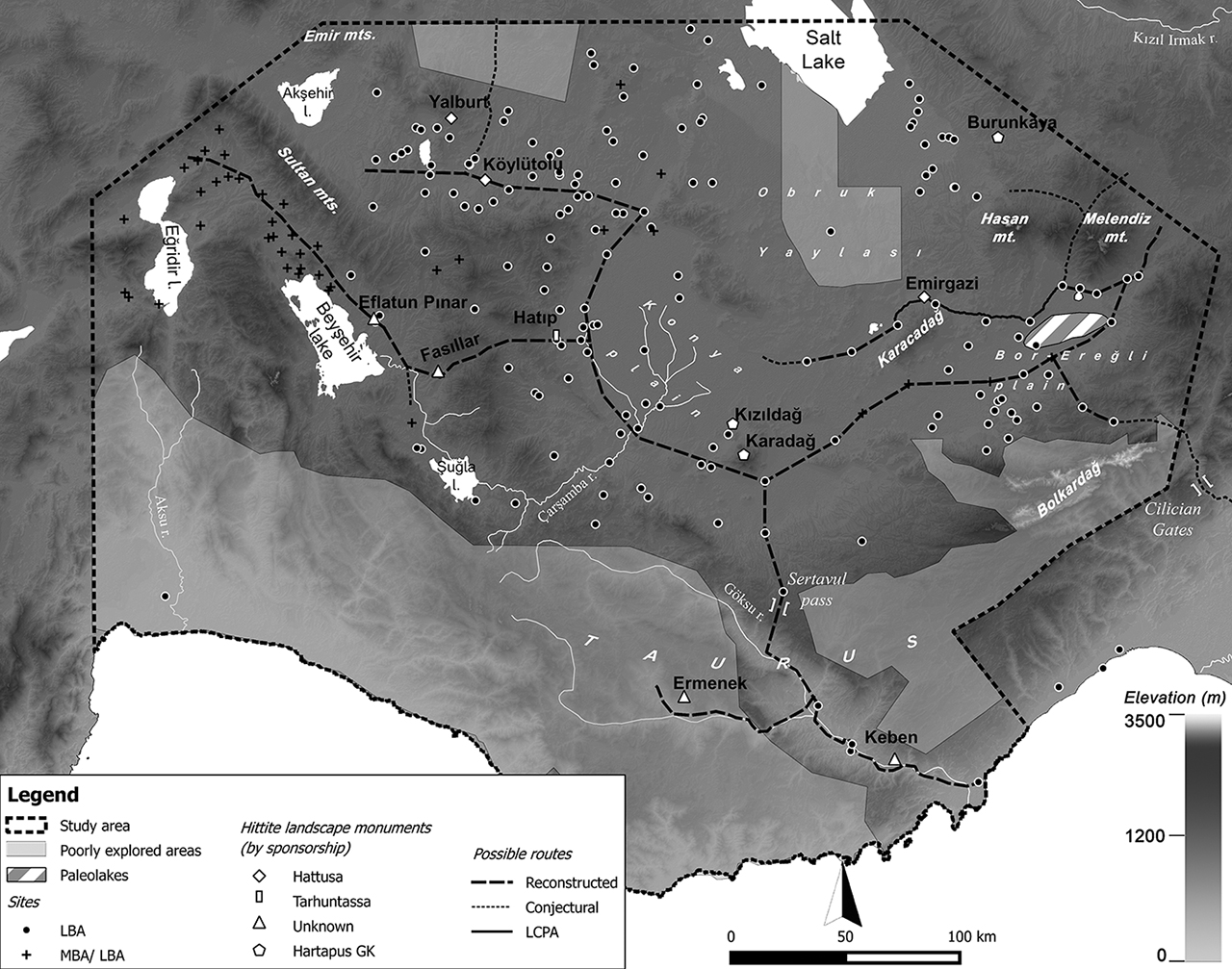

The Late Bronze Age archaeological landscape in South-Central Anatolia and possible communication routes. “Reconstructed” are those routes mainly inferred from the distribution of settlements and landscape monuments and corroborated by textual sources. “Conjectural” routes are those routes whose existence is assumed on the basis of historical interpretation. The least-cost pathway (LCPA) has been calculated on GRASS GIS by choosing Kınık Höyük as starting point and the LBA-IA site of Kıçıkışla, in the Emirgazi area, as destination point. Map and graphics by Alvise Matessi.

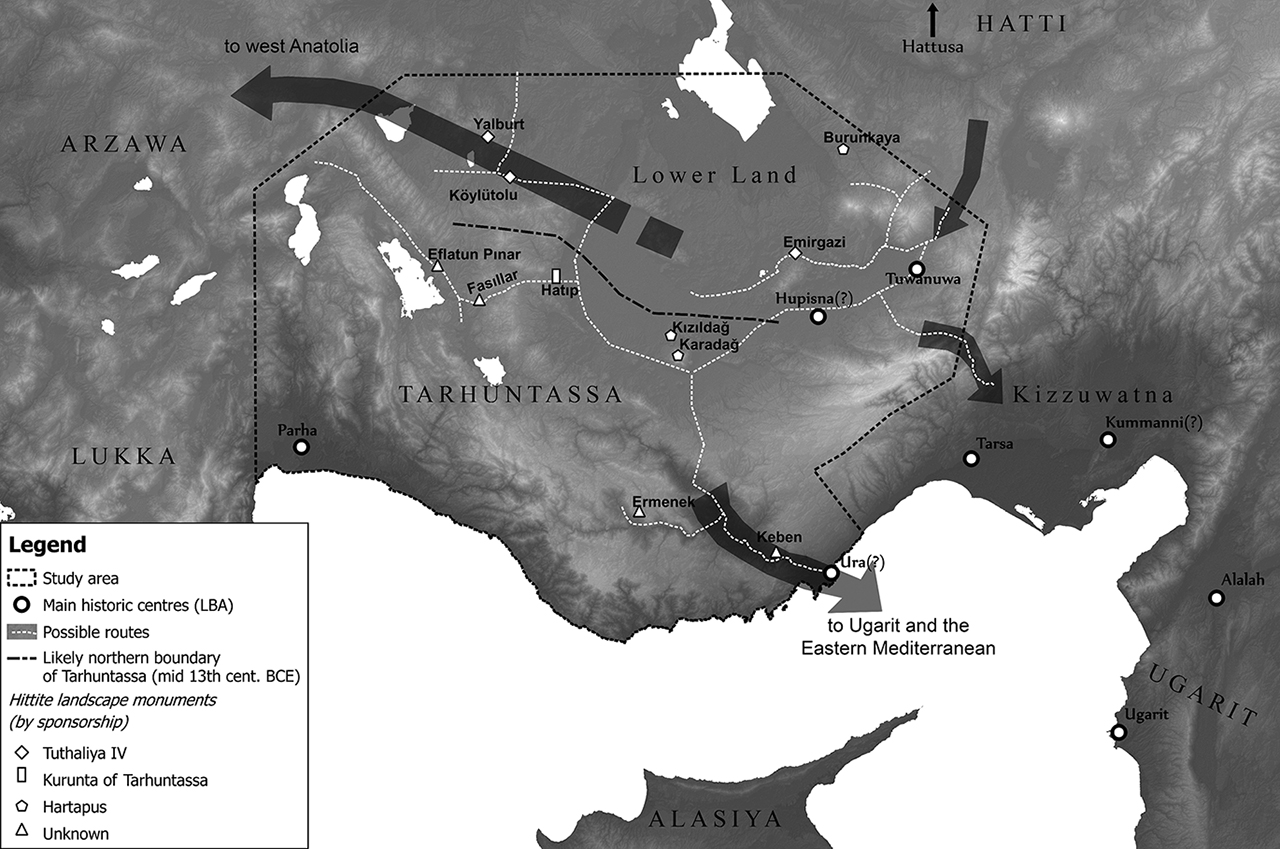

Mobility and political interaction in South-Central Anatolia by the late thirteenth century BCE. Map and graphics by Alvise Matessi.

The second limit hinges upon the specific spatiotemporal coordinates of the present work. In Central Anatolia, the 2nd millennium BCE is characterized by an overall continuity in cultural traditions, evidenced especially in pottery assemblages. This continuity restricts the range of ceramic diagnostics for the different phases of the 2nd millennium BCE, calling for caution especially when analyzing diachronic settlement trends between the Middle and the Late Bronze Age. [13]

Here, a synchronic analysis of survey results will be preferred, aiming to understand the degree of integration of South-Central Anatolia within the Hittite interregional system through the reconstruction of its communication network. Such an approach is only partially undermined by the above limits as long as it is attained by integrating bare settlement data with other evidence, which is substantially related to Late Bronze Age archaeological landscapes. The Hittite landscape monuments, for example, are very useful to the stated purpose, since they were usually erected in locales of major social interaction and friction, such as boundaries and, precisely, communication routes (Ehringhaus 2005; Glatz and Plourde 2011). Finally, the picture resulting from the distribution pattern of landscape monuments and settlements is complemented by information inferred from Hittite textual records. Therefore, Late Bronze Age route landscapes in South-Central Anatolia can be reconstructed or at least conjectured with a satisfying degree of approximation.

The sum of the contributory projects here taken into account provides for the identification of more than two hundred sites with likely traces of 2nd millennium BCE occupation, whereas 164 are more specifically ascribed to the Late Bronze Age (Figure 3). Highest settlement concentrations in this period seem to feature the northwestern half of the study area, with minor clusters in the environs of Konya, in the upper alluvium of the Çarşamba and in piedmont areas. In striking contrast with the high urbanization nowadays characterizing the low Çarşamba delta, little 2nd millennium occupation has been individuated in this area. [14] In the upper alluvium of the Çarşamba, instead, lies one of the largest known sites in South-Central Anatolia with likely Late Bronze Age occupation—Sircalı Höyük (33 ha). As to its extension, this site is second only to Sulutaş (47 ha), situated 15 km west of Konya. Other remarkable Late Bronze Age sites are Çomaklı (23 ha; Konya district), Kökez (20 ha; ca. 33 km east of Ilgın), and Kemerhisar, the site of Hellenistic and Roman Tyana, identified with the Hittite Tuwanuwa (25 ha, 15 km south of Niğde). To these, one may also add Kınık Höyük (see below), ca. 26 km west of Niğde, whose mound and terrace measure together 10 ha, but whose lower town would reach over 20 ha according to intensive pedestrian surveys in the surrounding fields (d’Alfonso and Mora 2010: 572–73).

As stressed above, very little has been explored of the Taurus highlands and Rough Cilicia, but the few available data point to a very low settlement rate during the Late Bronze Age (Aksoy 1991; Rauh et al. 2009). Poor Late Bronze Age settlement also characterizes the arid steppes of the Obruk Yaylası, an area almost uninhabited in present days, too. Nonetheless, a few Late Bronze Age sites are found at the southern fringes of the Obruk Yaylası, in the stretch of relatively fertile land along the piedmont of the Karacadağ. Significantly, these settlements are aligned at a rather regular distance (18–22 km) between Emirgazi and Karapınar, following one of the main east-west orographic corridors across the Konya basin (Figure 3). In this respect, it is worth noting that the eastern end of the alignment is located just close to the find-spot of the Emirgazi altars. Information about the exact original position of these artifacts is very meager. Nonetheless, they are intimately connected with the surrounding landscape. Running around the altars, in fact, is a lengthy hieroglyphic dedication by the Hittite king Tuthaliya IV (13th BCE) to the mountain god Sarpa, likely to be identified with mountain Arısama, a small outcrop facing the Karacadağ from behind Emirgazi. [15] It is reasonable that the presence of a major route of transit passing in the vicinity of the altars played a role in the choice for their collocation. Moreover, if we assume that habitation in the four sites forming the regular alignment at the Karacadağ feet overlapped in time during the Late Bronze Age, their evidence would combine with that of the altars and draw a north-east to south-west transit route. A least-cost pathway analysis (LCPA) performed with GRASS GIS on an ASTER Digital Elevation Model shows that the road through Emirgazi is likely to have passed by the site of Zengen Höyük to join a cluster of sites at the piedmont of the Hasan-Melendiz. [16] In turn, the Hasan-Melendiz piedmont was likely connected with the crucial north-south axes of the Konaklı valley and the Cilician Gates.

On the opposite side of the Konya province, between the Sultan and Emir mountain ranges, lies the Akşehir open-through. Major route connections passed across this area in antiquity and, more specifically, during the Hittite period, as hinted by the high density of Late Bronze Age settlement observable there. The strategic value of the Akşehir open-through during the Late Bronze Age is also suggested by the presence of a Hittite fortress, Ilgın Kaleköy/Zeferiye, built on a hilltop guarding the eastern entrance of the corridor. [17] About 7 km to the southeast of Ilgın Kaleköy lies the Hittite dam of Köylütolu (Figure 3) that was possibly used as a mustering point for Hittite troops transiting in the area (Ullmann 2010: 217, n. 485). Like the altars of Emirgazi, the Köylütolu dam was sponsored by Tuthaliya IV, to whom is associated an inscription featured on a basalt block recovered from within the earthen wall of the dam (Masson 1980). Another, more outstanding monument of Tuthaliya IV lies not far from Köylütolu, in the hilltops overlooking the plain of Ilgın: it is the Yalburt spring pool, carved with a lengthy hieroglyphic inscription. In paragraph 4.2 I will further discuss this evidence in connection with the geopolitical scenario of South-Central Anatolia during the second half of the thirteenth century BCE.

We lack archaeological information for the 2nd millennium BCE occupation in the middle course of the via Tauri toward the Cilician Gates, but available settlement data at the northern feet of the Taurus suggest that the Late Bronze Age route diverged here in two branches: one running westward to Ereğli (Hittite Hupisna?) and the other running north-eastward to Tyana/Tuwanuwa and Niğde (Figures 3 and 4). The existence of such itineraries would fit with information inferred from Hittite written sources (Forlanini 2013: 16–20).

Much evidence suggests that also the Göksu river valley worked as a vital communication route during the Late Bronze Age. Firstly, it led directly to the Hittite harbor of Ura, likely located at the mouth of the Göksu in the vicinity of Silifke. [18] As we will see in better detail (paragraph 4.2), various textual sources from the Empire period describe Ura as a main intermediary in the commercial relationships between Hatti and the Levant (Klengel 1974; and 2007). From an archaeological viewpoint, strong ties between the Göksu valley and North-Central Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age are hinted by the fact that the two areas display very similar distribution patterns of imported ceramics (Kozal 2003; 2007). In particular, the Red Lustrous Wheel-made ware, diffused throughout Anatolia from the fifteenth century BCE and likely originating from Cyprus (lastly, Grave et al. 2014), is found in large quantities in the Göksu valley at Kilise Tepe (see below) and in North-Central Anatolian sites, namely at Hattusa/Boğazköy itself, but is comparatively much scarcer in other important areas of the Hittite domain in Anatolia, such as plain Cilicia.

Since no 2nd millennium site is known in the Göksu valley upstream from Mut, we may assume that during this period access to the valley from the Konya plain was provided by the Sertavul pass. This hypothesis is strengthened by the presence of a 2nd millennium site, Kozlubucak, just close to the northern end of the Sertavul pass. During the Late Bronze Age, Kozlubucak possibly also had a role in the inner Anatolian circulation of the Red Lustrous Wheel-made ware that, in fact, has been collected in remarkable quantities on the surface of the site. [19] Through Kozlubucak, the path coming from the Göksu valley crossed the environs of Karaman before proceeding into the Konya plain.

3.2 Excavations

When compared to the large amount of possible Late Bronze Age sites individuated through regional surveys, there are only a few sites in our study region providing substantial stratified data for the same period, namely Kilise Tepe, Porsuk/Zeyve Höyük and Kınık Höyük (Figure 2). The site of Kilise Tepe is a 4 ha rounded mound located in the Göksu valley, which, as remarked above, represented a major resource in the Anatolian route system, providing access to the Mediterranean. The excavations at Kilise Tepe, carried out by a British expedition between 1998 and 2011 (Postgate and Thomas 2007a; Bouthillier et al. 2014), brought to light a superimposition of two Late Bronze Age occupations corresponding to Level III and the phases a-d of Level II (Level IIa-d). Radiocarbon and dendrochronological determinations would date the foundation of the main architectonic features of Level III to around the mid-fifteenth century BCE. The main structure of Level IIa-d, the Stele building, was constructed ca. one century later, probably shortly after a destruction event that sealed Level III. [20] The construction of Level IIa-d represented a complete departure from Level III in terms of architectonic layout, turning about 60° of the orientation of the main axis. However, despite this break, during both occupation periods, Kilise Tepe remained in the sphere of Hittite socio-cultural interactions, as testified by the continued presence of Hittite seals and standardized NCA-style pots. The destruction of Level II, in its phase d, has a post quem date to the mid-twelfth century BCE, i. e. to the Bronze-Iron Age transition, confirmed by the finding of Mycenaean LH IIIC vessels in the deposits.

Porsuk/Zeyve Höyük is a 4 ha tabular mound of triangular shape located close to the northern entrance of the via Tauri into the Taurus chain. The French expeditions excavating this site since 1970 brought to light a sequence of two Late Bronze Age occupations, respectively labeled Niveau 5 and Niveau 6. [21] The stratigraphic articulation between these two levels is particularly clear on the eastern side of the mound (Chantier IV), while the western edge (Chantier II) is occupied by a monumental Late Bronze Age defensive system probably in use during both Niveaux 6 and 5. In both areas, the last Late Bronze Age occupation is sealed by destruction layers of carbonized or charred debris, likely deriving from a major fire event. While the finds from Niveau 6 are still waiting for full publication, the ceramic assemblages of Niveau 5 would safely ascribe its material culture to a North-Central Anatolian cultural horizon (Dupré 1983; Glatz 2009: 129–131). As to the chronology of the Late Bronze Age sequence at Porsuk, combined dendrochronological and radiocarbon data would date the construction of Niveau 6 to the second half of the seventeenth century and that of Niveau 5 to the early sixteenth century BCE. [22] More problematic is dating the end of the Late Bronze Age occupation and its relation to subsequent Iron Age phases (Niveaux 4–3), whose initial chronology is also not well established. Former hypotheses were purely speculative and associated the destruction of Niveau 5 with the collapse of the Hittite Empire in the late thirteenth century (Dupré 1983: 42). Seeking a firmer chronological ground by disentangling the archaeological evidence from any historical prejudice, the Porsuk team undertook a new program for obtaining absolute dates from several areas and levels of the site. While some of these analyses still wait for full processing and publication, none of the dates so far obtained and reported point to the existence of a thirteenth century occupation at Porsuk (Beyer et al., “Zeyve Höyük – Porsuk 2011”, 2012: 193; and Beyer 2015). On the contrary, they induce scholars to reconsider previous speculative reconstructions and to situate the final destruction of the Late Bronze Age settlement at Porsuk at some point between the late fifteenth and the mid-fourteenth century BCE rather than in the late thirteenth century BCE.

Some limited information on the Late Bronze Age chronology in South-Central Anatolia, lately, derives from the site of Kınık Höyük, a 10ha terraced mound located at the feet of the Hasan-Melendiz complex. Here, a new excavation project, started in 2011 by a joint American, Turkish and Italian expedition, has brought to light portions of the stone socle of an imposing citadel wall. [23] This wall is preserved in two editions, the latest of which, Level A.7, was built on top of the leveled remains of an earlier phase, Level A.8. After the Level A.7 wall was erected, it remained continually in use during the Iron Age (d’Alfonso, Gorrini and Mora 2015: 626–28). While excavations intra moenia still did not attain Level A.7, investigations of an accumulation lying above the outer surface associated to the Level A.7 wall and slanting downhill from it yielded a homogeneous collection of Early Iron Age ceramic fragments, offering a terminus ante quem for the construction of Level A.7 wall to the eleventh-tenth centuries BCE. This approximate chronological setting is, today, also supported by the 14C analyses of three samples collected in the same deposit. [24] For a more precise dating of the wall construction one can as yet rely only upon a single determination from timber making up the very structure of Level A.7 wall, which would point to around the late fifteenth century BCE (d’Alfonso, Gorrini and Mora 2016; d’Alfonso and Matessi in Matessi et al., forthcoming).

3.3 The archaeological landscape of South-Central Anatolia: conclusions

From the analysis of archaeological data presented here, we infer that the study region played a prominent role in the Late Bronze Age communication network in Anatolia, representing a complex node between east-west routes—especially relevant for military purposes—and north-south routes, leading to the Eastern Mediterranean through the Taurus passes. Moreover, the chronologically refined information deriving from a few excavated sites evidences multiple episodes of reformulation of built environments during the Late Bronze Age. These differ from each other in quality, ranging from destructions to (re)building activities, but they equally affected public constructions or large portions of settlements, thus acquiring particular significance in a socio-political perspective. Moreover, while most shifts are non synchronic, a possible convergence is to be found significantly between the fifteenth and fourteenth centuries BCE (Table 1). In the next paragraphs, I will frame this information within the narrative of the transformations affecting the political geography of South-Central Anatolia under the Hittite hegemony.

Late Bronze Age stratigraphic sequences in South-Central Anatolia.

| Kilise Tepe | Porsuk | Kınık Höyük | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1650–1600 ca. BCE | Gap in occupation after Level IV (?). | Foundation of Niveau 6 | Level A.8 citadel wall (?). |

| 1600–1550 ca. BCE | Foundation of Niveau 5 | ||

| 1450–1350 ca. BCE | Foundation of the NW building in Level IIId. | Destruction and abandonment of Niveau 5. | Razing of the Level A.8 citadel wall and edification of the Level A.7 wall (?). |

| End of LBA occupation. | |||

| 1380–1320 ca. BCE | Dismissal of Level III and foundation of Level IIa-c. | Permanence in use of the Level A.7 citadel wall (down to the 1st millennium BCE). | |

| 1250–1150 ca. BCE | Destruction of Level IIc. | ||

| Reconstruction of the Level IId Stele building and subsequent definitive destruction. |

4 Historical interpretation

4.1 South-Central Anatolia and the formation of the Lower Land (seventeenth-fifteenth century BCE)

During the fourteenth century BCE the most relevant political entity of South-Central Anatolia as known from Hittite texts was the Lower Land. [25] There is no certainty about its precise extent, but we are now sure that it comprised large portions of the Konya plain and the piedmont of the central Taurus range. The Hittite words used for defining the Lower Land are not known, since the conventional English translation depends from a heterographic form, KUR ŠAPLĪTI, with which the region is indicated wherever it is attested in extant sources (log. KUR=“country, land”; Akk. šaplītu=“the lower part”). [26] Direct references to the Lower Land/KUR ŠAPLĪTI are scattered in about fifteen texts that, significantly, are all dated to the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries, i. e. to the Empire period. On the contrary, no attestation of the Lower Land is found in earlier texts composed during the Old Kingdom. One of the earliest datable mentions of the Lower Land is known from a passage of the so-called “Deeds” of the king Suppiluliuma I, composed by his son Mursili II (CTH 40 - Güterbock 1956; del Monte 2008). The passage proceeds from the account of clashes with the west Anatolian confederation of Arzawa, which forced king Suppiluliuma I to summon one of his army commanders, named Hannutti:

[Sinc]e my father (i.e. Suppiluliuma I) was celebrating the AN.TAH.ŠUM festival for the gods of Hatti and to the Sun Goddess of Arinna – in fact, the question of [the gods] was demanding – (…), my father sent Hannutti, the chief of the chariot-drivers, to the Lower Land and gave him chariot-troops. When Hannutti [arrive]d [in the Lower Land], the inhabitants of the city of Lalanda were frightened at his sight and surrendered (lit. “made peace”): they became again [property of the land of Hatti?]. Hannutti, the chief of the chariot-drivers, went to […] and attacked the land of Hapalla, he destroyed with fire [the land of Hap]alla, took away its population [together with its cattle, sheep and bronze tools] and brought them to Hattusa.

(KBo 14.42, rev. 8ʹ-16ʹ; and KUB 19.22, 8ʹ-11ʹ. Cf. del Monte 2008: 64–67).

Another reference to Hannutti, in possible connection with the Lower Lands (plural!), is found in another work of Mursili II, this time his own “Comprehensive Annals” (CTH 61):

[But when] they saw the sickness of [my brother (Mursili’s direct predecessor, Arnuwanda II)], from that moment Hannutti, who administered the L[ower] Lands (KUR.KURMEŠŠ[AP-LI-TI] maniyahhiškit), as soon as he left for the region of Isḫupitta, he died there.

(KUB 19.29: obv. 10ʹ13ʹ. See Goetze 1933: 18–19)

The restoration KUR.KURMEŠŠ[AP-LI-TI], already proposed by Goetze in his edition, presents itself as a prima facie hypothesis, suggested by the association of the Lower Land with Hannutti in the “Deeds” of Suppiluliuma I and by the lack of any other satisfying alternative. In this light, the quoted passage from the Annals of Mursili II would represent the single most useful source about the political status of the Lower Land within the Hittite domain. From it, we understand that, as of the reign of Mursili II, the Lower Land was a coherent administrative unit—or province—governed by Hannutti, who held a position as high-ranking army commander under Mursili’s father, Suppiluliuma I (see also Klengel 1999: 188). The interpretation of the Lower Land as a province would be supported by an analogy with another region of the Hittite domain, the Upper Land. As the name suggests, the Upper Land was the geographic counterpart of the Lower Land and was located on the upper course of the Kızıl Irmak in North-East Anatolia (Gurney 2003). Also, the Upper Land was indicated through heterographic expressions of the type KUR ELĪTI, mirroring KUR ŠAPLĪTI (log. KUR=“country, land”; Akk. elītu=“the upper part”). [27] The parallel between the two lands is quite compelling: since, under the reign of Mursili II, the Upper Land was certainly a coherent province administered by local governors on behalf of the king, as proven by the “Apology” of Hattusili III (CTH 81 - Otten 1981; van den Hout 2003), it stands to reason that the same was also true for the Lower Land.

The writing of the place names Lower and Upper Land offers additional clues about the political statuses of the denoted regions. In fact, as Yakubovich argues (2014: 349), if KUR ŠAPLĪTI and KUR ELĪTI did reflect popular names used in the current language, the corresponding syllabic writing would also be expected to appear as alternatives to the heterographic forms, known and employed only within the restricted scribal circles of the Hittite court. Instead, the fact that only heterographic forms are attested suggests that the place names KUR ŠAPLĪTI and KUR ELĪTI were artificially imposed by the Hittite administration when ratifying the new geopolitical entities that they denote. [28] If this is so, when did this ratification occur? The self-evident observation that the modifiers “upper” and “lower” presuppose one another suggests that the constitution of the Lower and Upper Land provinces occurred in a single event. As a matter of fact, the place names Lower Land and Upper Land have a parallel chronological distribution in Hittite sources, limited to the Empire period. However, while extant attestations of the Lower Land do not predate Mursili II, the name Upper Land first occurs slightly earlier, in a group of letters from Maşat Höyük, likely produced between the reigns of Arnuwanda I and Tuthaliya III. [29] Several sources portray this time as a period of major military instability when foreign enemies allegedly arrived to surround and possibly occupy Hattusa itself (Bryce 2005: 145–51; Stavi 2015: 25–73). Such a situation was hardly appropriate for substantive administrative endeavors such as the constitution of new provinces. Moreover, if we trust the much later retrospective on the reign of Tuthaliya III offered by KBo 6.28, obv. 8–9 (Hattusili III: thirteenth century BCE), the Lower and the Upper Land were precisely among the regions most affected by the attacks. These considerations induce us to set the scene for the constitution of the Lower and Upper Land provinces prior to the reign of Tuthaliya III. If so, the reigns of his predecessors, Tuthaliya I and Arnuwanda I—straddling the fifteenth and fourteenth centuries—appear to be very suitable candidates. In fact, the constitution of new provinces would fit well within the program of reorganization of the Hittite state apparatus that prevailing scholarly interpretations credit to these two kings. [30] This program and the transformations it implied would have been instrumental to the evolution of the Hittite state from a regional power to a hegemonic empire, a process that was going to be completed later with the expansive policies of Suppiluliuma I and Mursili II.

What can be inferred about the geopolitical status of the Lower Land region before its organization into a province? Or, from another perspective, did the drawing of a new regional province in South-Central Anatolia entail changes in the administrative territoriality of the Hittite state? During much of the Old Kingdom, the area under Hittite hegemony was limited to a strip stretching between the Pontus and the Mediterranean Sea, across the Kızıl Irmak bend and the Konya plain. In this context, South-Central Anatolia was located at the periphery of the Hittite domain (Figure 1). In reconsidering the linguistic geography of South and Southwest Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age, Ilya Yakubovich (2010: 239–247) proposes that the Lower Land was the homeland of speakers of the Luwian language—luwili in Hittite—thus rejecting the prevailing hypothesis of their more westerly origin (i. e. Arzawa). On this basis, Yakubovich sets out to demonstrate that the territories that later became part of the Lower Land corresponded to the region of Luwiya during the Old Kingdom. The toponym Luwiya occurs a handful of times, all concentrated in a few passages of the Hittite “Laws” (CTH 291: §§5, 19–21 and 23) preserved in two manuscripts, the older (A) dating to the Old Kingdom and the later (B) to the Empire period. [31] These passages seem to draw a neat distinction between Luwiya—coupled once with the land of Pala— [32] on the one hand, and Hatti, on the other. These are treated as two separate spheres of the Hittite realm, involving different legal dispositions bearing on their respective subjects. Crucial to Yakubovich’s equation between Lower Land and Luwiya is a re-interpretation of § 19 of the “Laws”, where version B replaces one instance of Luwiya with Arzawa. Indeed, the traditional view takes this alternation as evidence for an identity Luwiya–Arzawa. Yakubovich, however, adduces arguments pointing to the contrary and looks for other places outside Hatti and associated with the Luwians where the laws of §§5, 19–21 and 23 could actually be enforced. [33] These, in his view, had to be areas under direct Hittite administrative control during the Old Kingdom. This would automatically rule out Arzawa, at that time a distant enemy land, as well as other regions, leaving the Lower Land as the sole remaining possibility. These arguments raised a heavy criticism. In particular, as shown by Teffeteller (2011) and Hawkins (2013a, 2013b), Yakubovich’s philological interpretation of § 19 forces the evidence with unwarranted assumptions, at the same time generating several problems of syntactic order that Yakubovich does not adequately address. [34] In addition, as to the matter of enforceability, Hawkins (2013a: 34) correctly observes that there is no clear indication that any judgment in the laws concerning Luwiya was applied beyond the borders of Hatti. In any case, I do not see the need for supposing precise geographical or political demarcations behind the opposition between Luwiya—or Pala—and Hatti. In fact, Luwiya and Pala, treated as peers from a legal standpoint, can be also understood as partes pro toto for the periphery of the Hittite domain during the Old Kingdom, independent of their actual political and administrative organization. This would be suggested also by the laws of §§22–23, where Luwiya just indicates what is between the “river”, most likely the Marassantiya/Kızıl Irmak that signed the boundary of Hatti, and the enemy land. [35] In sum, even assuming that the Old Kingdom Luwiya and the Empire period Lower Land somehow overlapped, nothing indicates a one to one correspondence. In what follows I will show that, when investigating the territorial organization of the Lower Land during the Old Kingdom, our ‘searching image’ should not be regional entities, rather a constellation of town-based administrative centers.

Documents relating to the Old Kingdom yield very little information about the mechanisms of the state administration, as do Hittite documents in general, but, nonetheless, they depict a territoriality more locally nucleated on several centers rather than articulated in a patchwork of regional provinces (Table 2). Passages from the single most important historical source about the Hittite Old Kingdom, the “Edict” of the king Telipinu (CTH 19), incidentally relate to a succession of two different arrangements of the local administration. [36] In the earliest arrangement, at work during the very formative period of the Hittite kingdom (mid-17th BCE), the main decentralized administrative structures were town-based districts. To the head of each district was assigned a DUMU.LUGAL, which is either a son of the Hittite Great King or a member of his kin. As shown in Table 2, evidence of this early household-based control of peripheral town districts seen in the “Edict” is also corroborated by passages of the “Palace Chronicles” (CTH 8). [37]

Summary of the evidence relating to changes in the Hittite administrative territoriality between the Old Kingdom and the Empire period.

| Chronology | Changes in the administrative territoriality and related evidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Formative period    | TOWN-BASED ADMINISTRATIVE TERRITORIALITY | “Edict of Telipinu”, § 4 (CTH 19, i 7–12).Edition: Hoffmann 1974: 12–15.Then, he (i. e. Labarna) kept devastating countries, he disempowered countries, he made the Sea as their boundary. But when he came back from the field, each of his sons went to the various lands. The cities of Hupišna, Tuwanuwa, Nenašša, Lānda, Zallara, Parsuhanda – they administered (Hittite: maniyaḫḫ-) these lands. The large cities were assigned to them. | |

| “Palace Chronicles”, KBo 3.34, iii 15ʹ-25ʹ=KBo 12.11, 5ʹ-11ʹ (CTH 8). Edition: Dardano 1997: 58–59.These are the brothers of the King, seating be[fore the K]ing’s [father]: Ammuna, DUMU of the town of Šukziya, then Pimpirit, [DUMU of the tow]n of Nenašša. (…) Thereafter, [PN] his relative (i. e. of the King), DUMU of the city of Ussa, was there. Also for him [a seat w]as prepared, there was a table for him, there was a wooden plate for him. | |||

| “Edict of Telipinu”, §§ 37–38 (CTH 19, iii 17–42). Edition: Hoffmann 1974: 40–45.§ 37List of “towns of the storehouses” (iii 17: URUDIDLI.HI.AŠA ÉMEŠ NA4KIŠIB), with about 30 place names preserved. Among these are north and northeastern centres (iii 20–21: Sukziya and Samuha), and south and southwestern ones (iii 28–32: Ikkuwaniya, Hurniya, Parsuhanda, and theHulaya river). | Active role of the LÚ AGRIG URUGN (“steward of the town etc.”) in the civil administration.See Singer 1984 and Bo 90/671 (Rüster and Wilhelm 2012: no. 46). | ||

| § 38List of “towns of the storehouse(s) with mixed fodder” (iii 42: URUDIDLI.HI.AŠA É NA4KIŠIB imiulaš), with about 15 place names preserved of unknown geographical location. | |||

| PROVINCIAL SYSTEM | Various sources attesting the Lower Land and the Upper Land as regional provinces. “The Great Prayer” of Muwatalli II (CTH 381, ii 38–40).Edition: Singer 1996: 16 and 37.The Storm God of Ussa, the Storm God of Parsuhanda, the mountain Huwatnuwanda, the Hulaya river, male gods, female gods, mountains and rivers of the Lower Land. | LÚMEŠ AGRIG attested only as cultic personnel. See Singer 1984. | |

The original intent of the “Edict” of Telipinu was to promulgate a reform with which to introduce firmer rules for the royal succession (§§ 28–34) and restructure the skeleton of the administrative apparatus (§§ 35–40). With this latter section, Telipinu is credited with having kick-started the second arrangement for the local administration, based on a network of “storehouses” (É NA4KISIB). The measure was meant to reaffirm and reinforce centralized control on victual revenues and includes, in fact, advice for Telipinu’s successors to seal incoming goods with their own seal (§ 40). Despite these changes, the territoriality of the system introduced by Telipinu’s reform remained nucleated around individual town-based districts, which are thoroughly listed in §§ 37–38. So, while evidencing an evolution in administrative procedures, the “Edict” reinstates the existing territorial organization of the Hittite domain, parceled in town-based units. This situation was radically different from that attested during the Empire period, when the Lower and Upper Lands were drawn as proper regional provinces. The transition from a town-based system to a provincial organization is better understood when comparing the geography involved. Some of the seats of local government making up the earliest arrangement depicted in “Edict” § 4 and in the “Palace Chronicles” became constituents of the Lower Land province during the Empire period. This is certainly true for Parsuhanda and Ussa, which are assigned to the Lower Land according to a paragraph of CTH 381, the “Great Prayer” of the king Muwatalli II (Table 2). As to the second arrangement, introduced by Telipinu in his reform, the evidence is even more meaningful. Paragraphs 37 and 38 concur in listing about 100 places, mostly towns. The disposition of the text in these two paragraphs follows a typological classification between two different kinds of storing facilities: “storehouses” (§37, iii 17: ÉMEŠ NA4KIŠIB) and “storehouse(s) of the mixed fodder” (§38, iii 42: É NA4KIŠIB imiulaš). No apparent principle of geo-political affiliation seems to govern the lists, and, for example, we do not discern any clear-cut subdivision between Lower Land places (iii 30–32: the river Hulaya and Parsuhanda) and Upper Land places (iii 21: Samuha), which are grouped together with other locales in §37. [38] This would show that multi-centered regional provinces were still not conceived as part of the territoriality of Telipinu’s reform. The administrative organization promoted by Telipinu was predicated, indeed, on individual town-based districts meant to function as nodes in the storehouse network fuelling the Hittite state economy.

Due to the paucity of relevant sources, it is difficult to follow the evolution of the administrative territoriality from Telipinu to Tuthaliya I and Arnuwanda I, when the regional provinces of the Upper and Lower Land were likely constituted. However, there is nothing in the extant sources to indicate major changes during this lapse of time. Until the Empire period, the LÚ.MEŠAGRIG (“stewards”) were responsible for the local storehouses. Consistently with the territorial arrangement in town-based districts informing the Old Kingdom, the LÚ.MEŠAGRIG were usually named in close association with the town where they were appointed (LÚAGRIG URUGN or LÚAGRIG ŠAURUGN). In his thorough inquiry on the AGRIG system, Itamar Singer (1984) argues on compelling ground that the status of the LÚ.MEŠAGRIG declined after Telipinu, possibly as a result of his own reform that reinforced centralized control of the storehouse management, thus constraining the operational capacity of local functionaries. Nonetheless, as Singer shows, individual LÚ.MEŠAGRIG are attested as cultic personnel in religious texts copied down during the Empire period. Moreover, the recently published land grant Bo 90/671 now proves that the LÚ.MEŠAGRIG continued to be a clearly recognizable office in the civil administration at least until the reign of Muwatalli I. [39]

In conclusion, the extant evidence shows that major transformations occurred in the geopolitical layout of Anatolia between the Old Kingdom and the Empire period. While the Old Kingdom was a segmented landscape of town-based districts, ruled by local representatives of the Hittite king or embedded in a centralized network of administrative structures, extensive regional provinces were constituted at the beginning of the Empire period, between the fifteenth and the early fourteenth century BCE. The Lower Land, occupying much of South-Central Anatolia, was one among such provinces, the other being the Upper Land, in Northeast Anatolia. [40] The evidence discussed also indicates that the provincial constitution, at least in the case of the Lower Land, was determined e pluribus unum, by unifying multiple pre-existing town-based districts in a single regional entity. As a final remark for this paragraph, it is worth observing that the expressions KUR.KURMEŠ or KURḪI.A (“lands, countries”), occasionally featuring the names Lower and Upper Land in textual attestations, may be a vivid signal for the original segmentation of the corresponding regions into several districts. [41]

4.2 The Lower Land and South-Central Anatolia in the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BCE

The transition from one form of territorial governance to another might be expected to reassemble existing sources of local authority according to different hierarchical dispositions. In particular, some centers ought to grow in importance when becoming foci for the management and distribution of local resources on the wider provincial scale, while other settlements that functioned as local administrative seats within the town-based system could have lost their centrality. The foundation of Level III at Kilise Tepe and, possibly, of the Level A.7 citadel wall at Kınık Höyük, together with the likely abandonment of Porsuk after the destruction of Niveau 5, might be interpreted as material markers of similar transitions. The convergence of these shifts around the late fifteenth century BCE significantly coincides with the period proposed here for the reform of town-based administrative districts into regional provinces.

The reshaping of political landscapes in South-Central Anatolia was followed by further transformations during the fourteenth century BCE, also fuelled by new historical developments. As we have seen in the description of the long-term landscape data, during the Late Bronze Age, South-Central Anatolia was a major crossroads in the interregional route system. This centrality likely acquired a new significance by the mid-fourteenth century BCE, that is, when king Suppiluliuma I steadily expanded Hittite supremacy beyond Anatolia, to include the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia. Thanks to this achievement, Hatti, now a geographic term referring to the entire Hittite domain, gained a new position in the Eastern Mediterranean network and established exchange relationships on equal terms with longstanding powers, especially Egypt. However, this condition could continue having fruitful returns thanks to a tighter integration, more so than through just military and political control over Anatolia and the Levant. For instance, the flow of communications with the newly conquered territories in the Levant also had to be enhanced. Even though overland routes likely continued to play a prominent role in this scenario, especially for military purposes, [42] connections by sea probably acquired a new significance at least in relation to trading activities: the Eastern Mediterranean hub of Ugarit, as well as the seashores of Cilicia and the Northern Levant, in fact, were drawn under stable Hittite control, a situation that lasted until the end of the thirteenth century BCE. The Levantine coast could be most easily reached from North-Central Anatolia via the Mediterranean Sea after crossing the Taurus along the Cilician Gates and, especially, the Göksu valley (Figure 4). Both passages were exclusively accessed through the Konya plain, i. e. through the Hittite Lower Land. This means that as of the mid-fourteenth century BCE this region became the natural trait d’union in an interregional communication network entirely subsumed under Hittite control and having its poles in North-Central Anatolia to the one side and the Levantine coast to the other. As hinted by the abovementioned pattern of diffusion in Anatolia of the Red Lustrous Wheel-made ware (paragraph 3.1), the Göksu area was particularly vital in this system. As anticipated, the port of Ura, in the likely vicinity of modern Silifke, had a crucial role in the commercial relations between Hatti and the Levant. [43] In particular, as evidenced by a series of letters sent to the court of Ugarit during the late Empire period, Ura might play as an intermediary in the flow of grain supplies during times of food shortage. [44] In the thirteenth century the Great King Hattusili III (thirteenth century BCE) issued a number of provisions regulating the relationship between the authorities of Ugarit and the merchants of Ura, who had evidently become a permanent presence at Ugarit. [45] Several merchants of Ura are indeed attested at Ugarit in juridical documents. In one of these texts (RS 17.316) they are called “merchants of My Majesty”, i. e. of the Hittite Great King, thus indicating the latter’s direct involvement in Ura’s commercial relationships. [46] All this evidence indicates that, starting at least with the fifteenth century BCE and, more so, with the Hittite conquest of the Levant, Ura and the Göksu valley became a highway for the flow and circulation in Hatti of imported commodities from the Eastern Mediterranean. It is tempting to connect this rising importance with the deep changes involving the architectural layout of Kilise Tepe between Levels III and II around the mid-fourteenth century BCE (Table 1).

The beginning of the thirteenth century BCE, as is well known, is characterized by one further deep change in South-Central Anatolia: the transfer of the Hittite royal seat from Hattusa, the centuries old capital of the Hittite domain, to Tarhuntassa operated by Muwatalli II. The circumstances of this relocation are only partially illuminated by sources postdating Muwatalli II, and the motivations behind it remain matter of discussion. The standard view takes Muwatalli’s move as a tactic to approach the Syrian front in preparation for the final confrontation with Ramses II at Kadesh (ca. 1275 BCE). With the Hittite Great King and the bulk of his army engaged for a prolonged period in distant lands, a relocation to the south would have also secured the headquarters of the administration against attacks of the Kaska, a loose group of semi-nomadic populations living in the Pontus mountains that represented a permanent threat to Hattusa and its environs (Bryce 2003: 91; and 2005: 231). Unsatisfied with such interpretations, Itamar Singer has recently proposed a very suggestive and articulated hypothesis (1996a: 191–93; 1998; and 2006b), explaining the transfer of the capital to Tarhuntassa in the light of a religious reform with which Muwatalli elevated his own personal deity, the Storm-God of Lightening (pihassassi), to a leading role in the Hittite pantheon. This hypothesis finds support in many later texts and, especially, in the “Apology” of Hattusili III (CTH 81: i 75), where Muwatalli II is said to have left Hattusa by the “command of his god”. Incidentally, the “Apology” also mentions the Lower Land in connection with the destination of Muwatalli’s transfer, thus providing textual evidence that Tarhuntassa was located in that province. [47] In Singer’s interpretation, Muwatalli’s reform would have led to a thorough reorganization of the state cult and of the divine hierarchy, according to outlines that Muwatalli II devised in his own “Great Prayer” (CTH 381). Initially, the reorganization and its religious outcomes were disentangled from Tarhuntassa, and indeed this place name does not appear in the “Great Prayer”. [48] However, later sources show that Tarhuntassa, whose name derives from that of the Luwian Storm God (Tarhunt), became the main cult centre for the Storm God pihassassi (Haas 2004: 326; Taracha 2010: 98–99).

Be that as it may, as to the ultimate causes of Muwatalli’s transfer, why choose Tarhuntassa, in the Lower Land, and not other places in other regions? If we maintain that Muwatalli II intended with his policy to come closer to the Egyptian front and, consequently, to avert the dangers of a Kaska invasion, moving his headquarters to the Lower Land was not the only solution, not even the best one. Another more suitable destination, for example, could have been the region of Kizzuwatna, in Plain Cilicia, that lay close enough to Syria and was a well-protected niche fenced in by the Taurus and the Amanus. As a matter of fact, Kizzuwatna and its gods also occupied a prominent place in the religious agenda of Muwatalli II, a predilection also testified to by his own commemorative relief carved at Sirkeli, on the Ceyhan river. [49] On the other hand, recognizing that the origins of the cult of the Storm God pihassassi are probably to be traced elsewhere than in the Lower Land (Singer 1996a: 187–89), Singer also wonders about the reasons for the specific trajectory of Muwatalli’s move (1998: 540–41). Therefore, he suggests almost in passing that these reasons resided in the search for “a more centrally located focal point for his [Muwatalli’s] huge kingdom” (2006b: 44). Our discussion of the archaeological landscape of South-Central Anatolia and its implications provides firmer ground to Singer’s tentative assumption. As shown above, in fact, probably more than the landlocked Hittite heartland in North-Central Anatolia or other regions of the peninsula, South-Central Anatolia was part of an interconnected network, marshaling circulation to and fro overland and sea routes. In addition, the father of Muwatalli, Mursili II, had managed to (temporarily) stabilize the troublesome western frontiers of the Hittite domain, intensifying Hittite involvement in this direction as well. In view of these considerations, one should perhaps fit Singer’s reconstruction of Muwatalli’s religious reform in the frame of a more “pragmatic” scenario. In spite of the advantages offered by South-Central Anatolia in terms of its centrality and interconnectedness with the southern and western peripheries, establishing a new capital therein required restructuring the existing network of political relationships as well as mobilizing a large amount of economic resources. These implications were very likely unwelcome by the elites most rooted in Hattusa (lastly, d’Alfonso 2015, with further references). Therefore, setting the relocation of the capital in the framework of a religious agenda might have been key to destabilizing any incidental opposition. In Hittite praxis, divine sanctioning was fundamental to every facet of political and military life and arguably became even more necessary when a new economic network, including systems of cult offerings in association with religious festivals, had to be rearranged around the new capital.

While Muwatalli II clearly intended his relocation of the Hittite political core in South-Central Anatolia to be permanent, the following course of events pointed in a different direction. Muwatalli’s son and successor, Urhi-Tešup, left Tarhuntassa and—likely pressed by his uncle, Muwatalli’s brother Hattusili—restored the capital back in Hattusa. Still, subsequent revolutions within the Hittite ruling family had a much profound impact on the territoriality of South-Central Anatolia. Urhi-Tešup, the king to rule legitimately, was deposed by Hattusili (III) after a dramatic civil war. In the intent to secure his reign and to stall the opposition of other possible claimants to kingship, Hattusili III granted Kurunta, another son of Muwatalli II, the seat of Tarhuntassa, which was vacant after the restoration of the capital in Hattusa. [50] Tarhuntassa, thus, became the seat of an appanage kingdom, endowed with large autonomous power while still formally subject to Hattusa through regulations laid down in diplomatic treaties (CTH 106). [51] Boundary descriptions included in these treaties, cross-checked with other relevant information, safely indicate that this kingdom comprised a large portion of the southern Konya plain, reaching down to the Mediterranean Sea across the central Taurus (Folanini 2017, with literature). Despite having some of its territories assigned to Tarhuntassa, the Lower Land continued to exist as a possession of Hattusa, forming its southern borderland in face of the new appanage kingdom. [52] The de facto division of Anatolia into two parts, with Tarhuntassa handed over to a representative of Muwatalli’s first line of succession, ultimately undermined the supremacy of Hattusa, inaugurating a phase of latent competition—if not open conflict—between the two domains. [53] As it might be expected, South-Central Anatolia was the very fulcrum of this tension, and both Hattusa and Tarhuntassa engaged in considerable ideological investments in the area in order to affirm their respective claims. These investments are chiefly manifested in the several monuments dotting the region that, working as a means of power or identity display, represented symbolic locations for conveying claims over contested landscapes (Seeher 2009; Glatz and Plourde 2011). All Hittite monuments found in the study area date to about the mid-thirteenth century BCE or later, a period that significantly coincides with the turn of events related to Tarhuntassa and its kingdom. [54] When known, monument sponsorships can well inform about the competing power spheres intersecting in South-Central Anatolia. The relief of Hatıp, representing Kurunta in the guise of “Great King”, a title usually reserved to the kings ruling in Hattusa, counterbalances the almost contemporary monumental programs that his cousin, Tuthaliya IV, undertook in roughly the same area (Figure 4). Conversely, Tuthaliya’s monumental activity was more intense in the Konya plain than anywhere else, excluding Hattusa/Boğazköy and its environs (Glatz and Plourde 2011: 56, Table 2). This proves how South-Central Anatolia was ideologically and politically a determinant to the outcome of power contests within the Hittite domain. As we have seen in paragraph 3.1, Tuthaliya IV was mostly engaged with the northern bend of our study area, between Emirgazi and Ilgın-Akşehir, which likely constituted the actual border between the Lower Land and Tarhuntassa (Dinçol et al. 2000). There are reasons to think that this bend also represented a crucial route axis toward western Anatolia that rose to strategic prominence precisely in relation to the novel political scenario of the late thirteenth century BCE. As we have seen, a major landmark in this area is the artificial pool erected by Tuthaliya IV at Yalburt, on the hilltops overlooking the Ilgın and Atlantı plains. Recently Harmanşah (2015: 54–82) stressed that, while being a place of ritualized performance embedded in the landscape, the Yalburt pool complex was also charged with political significance as a place of Hittite imperial commemoration. This is best indicated by the lengthy hieroglyphic inscription carved on the pool ashlars that celebrates Tuthaliya’s successful campaigns in the Lukka region, corresponding to Classical Lycia (Poetto 1993; Hawkins 1995: 66–85). Interestingly, likely the same episodes of Tuthaliya’s engagement in Southwest Anatolia, revolving around some of the same localities, are commemorated on a basalt block found together with the Emirgazi altars, ca. 200 km to the east of Yalburt. [55] Such close similarity in content between the Emirgazi and Yalburt inscriptions and the evidence presented here for east-west routes in the vicinity of both monumental complexes suggest that the Yalburt pool and the Emirgazi altars were part of the same program. This was aimed at reifying Tuthaliya’s claims upon a route axis that crossed the Lower Land and was functional for the Hittite military engagement in West Anatolia (Figure 4). Moreover, the monuments of Yalburt and Emirgazi held additional strategic significance as they were located along the boundary with Tarhuntassa. In this light, the Yalburt-Emirgazi route axis can be taken as an emblem of the hybrid condition of the Lower Land in the mid-thirteenth century BCE as both a frontier, i. e. an “outward” edge between the Hittite Empire and its western neighbors, and borderland, as the “inner” edge between the domains of Hattusa and Tarhuntassa. The same impression is also conveyed by the Bronze Tablet, especially in the passage concerning the military obligations imposed by Tuthaliya IV to Kurunta of Tarhuntassa(CTH 106.I):

iii 35−36 Hereafter, 100 infantry troops (of Tarhuntassa) shall go in a military campaign of Hattusa, but no one shall seek (lē šanhanzi) from him (i.e. for Kurunta) additional troops from the administration. iii 37−38Whenever they mobilize his army, let them mobilize 100 of his infantry troops, but no horse is expected on his behalf.iii 39−41 If someone of equal rank rises up against the Great King or if My Majesty sets forth on a military expedition on this side, out of the Lower Land, shall one mobilize 200 troops from him, iii 42but they shall not constitute permanent garrison (ašandulanzi=ma=at lē).

(Bronze Tablet, iii 35–42; Otten 1988: 22–23)

It may be noticed that, unusual for a subordination treaty, the Hittite Great King Tuthaliya IV puts more of an emphasis on what aid Kurunta shall not provide to the Hittite army rather than the contrary. On account of the character of the Bronze Tablet, generally quite favorable towards Kurunta, scholars agree that this passage, as others in the same text, concerned concessions granted to the king of Tarhuntassa by reason of his prominent status. [56] However, it is tempting to also see in this passage a symptom of Tuthaliya’s masked intent not to fuel the military prestige of Tarhuntassa, which could further undermine the supremacy of Hattusa in South-Central Anatolia. This is the viewpoint that could better explain the lines iii 39–42: campaigns on the side of Lower Land are presented here as a special case, notably of the same gravity as a war against another Great King. In both cases, in fact, Kurunta is required to double his normal contingent. But the formulation of the treaty also denounces a particular effort to avoid any further involvement of Tarhuntassa with permanent troops. The prohibitive ašandulanzi lē (“they shall not garrison”) addresses no one else than precisely the army of Tarhuntassa: contrary to ll. iii 35–36, there is no apparent intent here to remit the administration of Tarhuntassa from duties but, rather, to restrict its own scope of action, even when Tarhuntassa was siding with Hattusa during a war in the Lower Land. [57] It seems, in conclusion, that the complex political interactions between Hattusa and Tarhuntassa made the Lower Land the fulcrum of a fragile balance between the need for collaboration on security for shared frontiers and latent competition over inner borderlands. Another document, the letter KUB 19.23 written by a young Tuthaliya IV, emphasizes the crucial role that the Lower Land had in this delicate phase. In fact, after reporting on rebellions in the city of Lalanda, Tuthaliya worries:

Were the land of Lalanda to fall, even the whole of it, it would be for us only a matter of force, but were the Lower Lands (note the plural: KURḪI.AŠAPLITI) to fall, there would be nothing at all for us to do!

(KUB 19.23, rev. 19ʹ-20ʹ; Hagenbuchner 1989: 28–29; Hoffner 2009: 347)

Stability in South-Central Anatolia was more a priority in the political agenda, insofar as the region also retained its central role in connections with the Eastern Mediterranean. As we have seen, most documents related with Ura and its commercial relations with Ugarit likely date to this period. The exact political affiliation of Ura and the Göksu area during the thirteenth century BCE, as to Hattusa or Tarhuntassa, is still controversial. [58] In all events, communications between Ura and North-Central Anatolia needed the mediation and support of Tarhuntassa (Singer 1996b: 65–66), which likely controlled the Karaman area down to the western Bolkardağ. [59]

At the turn of the Late Bronze Age, with the Hittite monarchy waning and close to its demise, upheavals and conflicts affected South and Southwest Anatolia, also involving Tarhuntassa itself. This situation drew the direct intervention of the last known ruler of the Hittite Empire, Suppiluliuma II, as we learn from his Südburg hieroglyphic inscription. [60] In likely connection with the same events, an individual named Hartapu was active between the southeastern Konya plain and the modern Aksaray province (Figures 3 and 4), projecting his own hegemony there through a group of hieroglyphic inscriptions, where he states himself to be “Great King, son of Mursili”. [61] The working of these and other centrifugal processes during the Late Bronze Age and the ensuing demise of the Hittite Empire did not determine a complete rupture in South-Central Anatolia. The aforementioned sequence of the defensive walls at Kınık Höyük now provides evidence of a degree of local continuity well after the end of the Bronze Age, while the survival of Late Bronze Age ceramic and iconographic traditions in roughly the same region through the Early Iron Age is also now considered a fact. [62] The Iron Age (re)emergence of more readily recognizable ‘Hittite’ political and cultural traits in the Neo-Hittite polities of the eastern fringes of South-Central Anatolia definitely shows that features of local administration and economy probably continued to work in those regions, indicative of the high level of integration that they had attained within the network of Hittite core-periphery interactions.

5 Conclusions

This paper proposed an analysis of Hittite imperialism by outlining the dynamics involved in the formation and transformation of political landscapes. Focus has been on geo-political shifts taking place in South-Central Anatolia, a semi-peripheral area of the Hittite domain. I have shown how this region underwent considerable transformations in its territorial assets and assumed a pivotal role on a large supra-regional scale, in a process leading in turn to eventful developments within the Hittite heartland. Although being context specific, the conclusions proposed here have wider implications from a methodological point of view. In fact, a case is made for a productive interchange between archaeology and history that enables the following of processes operating at varying levels of social life and scales of durability.