Abstract

This article analyses Cypriot graffiti in Egypt engraved by tourists and mercenaries in the Archaic and Classical periods (sixth through fourth centuries BC). These graffiti were inscribed on walls of majestic monuments, e. g., the pyramids in Giza and the temples of Karnak and Abydos. They were written in different languages and scripts all employed on the island, such as Cypriot-syllabic Greek, Eteocypriot – an indigenous language still undeciphered – alphabetic Greek and Phoenician, spread throughout the city-kingdoms into which Cyprus was subdivided. The examination is conducted through a socio-cognitive approach, moving beyond previous scholarship which exclusively focused on the graffiti’s concise texts – often limited to the names and provenance of the writers. By comparing Cypriot Egyptian graffiti with contemporary graffiti and twenty-first-century graffiti written in Cypriot-syllabic script, the analysis will shed light on the role of socio-political environment and landscapes in triggering individuals’ – in this case Cypriots’ – cognitive-behavioral responses which lead them to write these texts. This pioneering approach will allow a better understanding of the underlying reasons why these graffiti were engraved and in which locations. The investigation will provide a better knowledge of the origins of the Cypriot writers, level of literacy, and of their role in society (e. g., insiders vs. outsiders), shedding light on communities that would otherwise be unknown. Furthermore, this study lays the foundations for developing an innovative methodology applicable to epigraphic studies, based on integrating landscape interactions and visual impacts to more traditional examination strategies.

Several graffiti have been engraved on the monuments of Egypt over the centuries from ancient times to the present day.[1] Among these inscriptions, Archaic and Classical Cypriot graffiti may be counted, the subjects of this investigation.[2] Fourth- to sixth-century BC Cypriot graffiti from Egypt are documents of remarkable socio-cultural value and provide information on individuals and communities which would be otherwise invisible.[3] Since they reflect the historical and social context of the island, these graffiti also shed light on the socio-political structure of Cyprus – e. g., the increasing Hellenized customs of the inhabitants or the internal subdivision of the territories of the Cypriot Archaic and Classical city-kingdoms into districts and villages. These graffiti were written in different languages and scripts such as Cypriot-syllabic Greek, alphabetic Greek, Cypriot-syllabic Eteocypriot, the island’s autochthonous language, and Phoenician, all used and attested in Cyprus.[4]

Through a fresh examination of their content, this article will be the first contribution that studies these testimonies in detail and moves beyond previous scholarship which exclusively focused on their concise texts – often limited to the names and provenance of the writers – and simplistically defined them as cartes de visties.[5] By contrast, through a socio-cognitive analysis of selected case studies, this investigation will look into the underlying reasons why these graffiti were written. It will explore the role of the environment and landscapes in triggering individuals’ – in this case Cypriots’ – cognitive-behavioral responses which lead them to write graffiti. The study will apply socio-cognitive approaches often employed when analyzing contemporary graffiti and, as we shall see, will compare the ancient Egyptian testimonies with a few contemporary Cypriot-syllabic graffiti from Cyprus. This innovative approach will allow a better understanding of the choices of the locations where the ancient graffiti were engraved, and of the origins and level of literacy of the writers, laying the foundations for an innovative methodology applicable to epigraphic studies broadly intended. In the case of the ancient documents, such a methodology aims to integrate landscape interaction and visual impacts to more traditional examination strategies, such as historical and philological analyses, to achieve a comprehensive knowledge and gather maximum information from the texts.

I The ‘first encounters’ of the Cypriots with the Egyptian monuments

Over the last several years scholarship has become interested in the socio-cognitive experience of reading and writing monumental inscriptions as well as casual graffiti in the ancient Mediterranean and Greek world.[6] Writing practices, systems, and traditions have been defined as entangled in a complex mesh of disciplines which focused on: 1) agency – closely connected with the materiality of the writing; 2) structural meanings – the information that texts provide; 3) the context, usually determined by socio-cultural elements and by the environment where the writers act.[7]

Recent historical and archaeological studies, also based on Cypriot landscapes, aimed to bring together a detailed analysis of geography and environment and the so called ‘sociological imagination’.[8] This definition, coined by Mills, describes individuals’ awareness of their personal experiences and daily activities as elements of a wider society, through the visual impact of the surrounding environment.[9] Papantoniou convincingly adopted this mixed approach to analyse the development of the Cypriot landscapes in the Archaic and Classical periods. He has demonstrated that the proliferation of extra-urban sanctuaries was related to the authority of the kings of Cyprus – the island was subdivided into several city-kingdoms and each of them was ruled by a sovereign who also was the main priest in the city. The Cypriot kings controlled the peripheral territories and legitimated their power through the visual impact that these sanctuaries had on visitors and worshippers.[10] Cypriot landscapes and environment contributed to the ‘sociological imagination’ of the inhabitants, through the view of the sanctuaries, and became ‘arenas’ for social agency, as Papantoniou has argued.[11]

As shown by this case study, the visual impact of the landscape plays a role in the individuals’ cognitive processes.[12] The landscape may be a familiar environment, in which the individuals are used to live and spending their days, or a total new environment, and the novelty may trigger different reactions. As in the case of the Cypriot sanctuaries, the Egyptian monuments – pyramids, temples, tombs – were also built to have an impact on the viewers and to stress the power and the authority of the sovereigns and the elite which commissioned them. The first encounters of Cypriots with the Egyptian monuments may have triggered reactions such as amazement and disorientation.[13] The amazement of being in front of a unique building of imposing dimensions – even Herodotus describes the fascination of the Pyramids (2.99–182) – may have spurred the viewers to leave a trace of themselves, to imprint the memory of their passage to everlasting memory. Certainly, the explorers of all centuries have left their marks on the Egyptian monuments for similar reasons – e. g., the curious figure of Domenico Ermenegildo Frediani (1783–1823), an Italian explorer and prolific writer, who also tagged the surface of Meroitic monuments with the nickname of ‘Amiro’ on, or Giovanni Belzoni (1778–1823), who sealed his discovery of the Khefren’s pyramid with signature and date on the internal wall.[14]

Disorientation and distance from home, however, may undermine the identity of an individual and the sense of belonging. The sense of belonging can manifest itself in groups that share religious, environmental, cultural or political values. When individuals become members of a group, they feel protected as parts of a community within a given place. A lack of feeling of belonging generates a sense of loneliness, isolation, and societal alienation.[15] According to these sociological remarks, Cypriots may have written graffiti on the monuments of Egypt not only to leave an imperishable trace of their passage but also to respond to a sense of alienation and disorientation, given that, by tagging the surrounding environment with their names, the writers made their identity and sense of belonging more concrete.

II Cypriot syllabary for breaking the outsiders’ barrier: the socio-cognitive experience of writing graffiti

To better understand the cognitive aspects of writing graffiti on the Egyptian monuments, it is worthwhile to examine the reasons why individuals write graffiti in contemporary societies; they have been extensively studied and provide sociological data that may be applied to communities from different historical periods.[16] As Gusfield argued, at the basis of writing graffiti there is the dichotomy between societal ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’.[17] The writers identify themselves as societal ‘outsiders’ but ‘graffiti subcultural insiders’. By tagging a new place with their names and city of origin, the writers state that they belong to that place, becoming new ‘insiders’. Such a practice contributes to develop writers’ ‘sense of place’, i. e., the sense of self in relation with the place that is occupied. The development of a ‘sense of place’ boosters the growth of a ‘sense of community’, solidarity, and cohesion among individuals.[18] On sociological terms, the sense of community occurs on two dimensions: the relational one, i. e., the relationship among individuals who are member of the same group, and the territorial one, i. e., the relationship between the individuals and the place that they consider ‘home’.[19] In contemporary society, as shown by Myra, et al., gang and crew members (e. g., sailors) who often feel social outcasts, write their names, zipcodes, and create clusters of graffiti to stress their ‘sense of place’ and ‘sense of community’.[20] Similarly, Cypriots who found themselves caught in Egypt were ‘outsiders’ in a new environment and landscapes, even more in front of the majesty of the Egyptian pyramids or of the temples. Conceivably, to face the feeling of alienation, to express their sense of belonging – and its relational and territorial dimensions – and to become new ‘insiders’, Cypriots wrote graffiti on the Egyptian monuments. The graffiti in Egypt, therefore, are the results of the Cypriots’ ‘physical and cognitive occupation of the space’. By writing their name and place of origin, Cypriots make their membership of a socio-cultural group tangible and visible.[21]

In this regard, the most striking elements of distinction for Cypriots are the scripts and languages they employed, which allow them to identify as members of a community. In Archaic and Classical Cyprus, the governments of the city-kingdoms adopted specific writing systems and languages as symbols of royal power and authority; they vary according to the city-state that used them.[22] For example, the Cypriot-syllabic writing system from Paphos, employed to write the Cypriot Greek dialect, is written from left to right; its signs show a peculiar archaizing shape which is distinctive of this city-kingdom.[23] However, to write the Cypriot Greek dialect, the other city-states adopted a ‘standard’ syllabary, written from right to left. Kition and Lapethos employed Phoenician alphabet and language in their administration, whereas the government of Amathus adopted the standard Cypriot syllabary to write the indigenous Eteocypriot language.[24] The inhabitants of the city-kingdoms tended to keep the distinctive script and language of their own place of origin and the Cypriot graffiti from Egypt also reflect this variety. Therefore, the writing system that Cypriots employed is a sort of zip code, a distinctive element which clarifies the origins and provenance of the writers, and shows the territorial dimension of their sense of community.

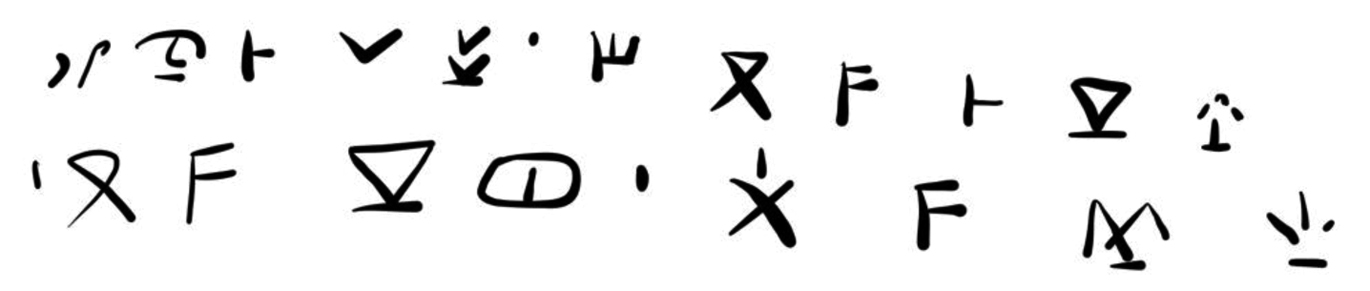

Contemporary Cypriot-syllabic graffito showing a-na-tu:-po-li, ‘Anthoupoli’ (2021).

The use of the Cypriot syllabary as distinctive label of origin is not a prerogative of ancient Cyprus. The Cypriot syllabary has remained a fundamental marker of the island’s identity for centuries, with a notable revival in recent years, even among common people. Some of the most significant contemporary examples also come from graffiti writers. Recently, a writer tagged a wall with the name of a Cypriot village close to Nicosia, Anthoupoli – probably where the graffito was written in both Cypriot-syllabic Greek – a revival version – a-na-tu:-po-li , and alphabetic Greek, ΑNΘΟΥΠΟΛΗ.[25] By adopting the Cypriot syllabary, and not exclusively the standard alphabet, the writer stressed his Cypriot origins. But unlike the Cypriots of the fourth century, who regularly employed the syllabic system in their everyday writing, the choice of the current writer was probably driven by stronger socio-political implications, to claim Cypriotness in a border area close to the buffer zone, which divides the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, a de facto state.[26] Remarkably, the syllabary has continued to make ancient and contemporary Cypriots’ membership of a collective group – that of the inhabitants of Cyprus – concrete and real, and still performs as a distinctive mark of the community’s territorial dimension. Similarly, a 2022 mural from Paralimni (Cyprus, Famagusta district) by the artist Sascha Stylianou bears Cypriot syllabic signs. These signs primarily serve a decorative function, and do not convey a specific linguistic meaning, whose visual significance is instrumental in expressing Cypriot identity and affiliation with the island, as the artist explained. Once more, the Cypriot syllabary assumes the role of a symbol for Cypriot identity, imparting a message through its visual impact that transcends the linguistic communication, akin to the manifestation observed with Cypriot graffiti engraved on monuments in Egypt.[27]

, and alphabetic Greek, ΑNΘΟΥΠΟΛΗ.[25] By adopting the Cypriot syllabary, and not exclusively the standard alphabet, the writer stressed his Cypriot origins. But unlike the Cypriots of the fourth century, who regularly employed the syllabic system in their everyday writing, the choice of the current writer was probably driven by stronger socio-political implications, to claim Cypriotness in a border area close to the buffer zone, which divides the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, a de facto state.[26] Remarkably, the syllabary has continued to make ancient and contemporary Cypriots’ membership of a collective group – that of the inhabitants of Cyprus – concrete and real, and still performs as a distinctive mark of the community’s territorial dimension. Similarly, a 2022 mural from Paralimni (Cyprus, Famagusta district) by the artist Sascha Stylianou bears Cypriot syllabic signs. These signs primarily serve a decorative function, and do not convey a specific linguistic meaning, whose visual significance is instrumental in expressing Cypriot identity and affiliation with the island, as the artist explained. Once more, the Cypriot syllabary assumes the role of a symbol for Cypriot identity, imparting a message through its visual impact that transcends the linguistic communication, akin to the manifestation observed with Cypriot graffiti engraved on monuments in Egypt.[27]

Contemporary mural with Cypriot-syllabic signs in Paralimni (2022), @Art Murals Signs Cyprus.

III Cypriot casual tourists’ and mercenaries’ graffiti (sixth-fourth centuries)

According to the provenance of the writers, their onomastics, and inscriptions’ scripts, it is possible to count at least 147 Cypriot graffiti on the Egyptian monuments: 135 – at least – written in Cypriot syllabary, 11 in alphabetic Greek, and 1 in Phoenician.[28] These inscriptions may be subdivided into graffiti engraved by occasional tourists and by mercenaries.[29]

Tourists’ graffiti usually show the name of the writers and their patronymic. An example of a tourists’ graffito is a Cypriot inscription dated to the fifth/fourth centuries engraved on the pyramid of Kheops in Giza.[30] Its text reads: (1) ka-ra-ta-to-ro-se | o-sa-ta-si-no (2) te-mi-to-i | mo-ra-to-ro | Κράτα(ν)δρος ὁ Στασίνω | Θεμιτώι Μορά(ν)δρω, to be translated as ‘Kratandros, of Stasinos. Themitó, of Morandros.’ The presence of the female name Themitó suggests that Kratandros and Themitó were a couple, probably visitors and not mercenaries, although wives of Cypriot mercenaries may have joined them, as happened with Greek mercenaries.[31] Kratandros and Themitó stood in front of the pyramid of Kheops, experienced amazement and disorientation, and decided to write a graffito on the monument, as many travelers who have explored Egypt did, leaving traces of their passage.[32] In this case, the patronymic and the employment of the standard Cypriot syllabary, a label of their provenance, convey their sense of belonging, of community, and its relational and territorial dimensions.

Graffito by Kratandros and Themitó; Egetmeyer (2010) vol. II, Egypt n°4 = ICS n°371 (drawing by the author).

In Egypt, however, mercenaries’ graffiti are the most common Cypriot inscriptions.[33] They contain more information than the tourists’ graffiti since the writers express their sense of belonging to two subgroups, that of the Cypriots in Egypt – as tourists also do – and that of the cohort of Cypriot mercenaries to which they belonged. In this regard, writers tend to create clusters of graffiti, unlike tourists’ graffiti which may also be isolated, whereas lone mercenaries’ inscriptions are rare.[34]

One of them may be dated to the Archaic period and comes from Bouhen, engraved on a column of the temple of Thutmosis III. It was probably written by one of the mercenaries who joined the campaign of Psammetichus II to Nubia.[35] The graffito was found close to other Carian graffiti, with which it was initially confused.[36] It shows five Cypriot-syllabic signs written in the peculiar Paphian syllabary – therefore, from left to right – and bears the text te-we-re-se, likely a non-Greek anthroponym.[37]

Paphian graffito from Bouhen Egetmeyer (2010), vol. II Egypt n°141; ICS n°455 = Halczuk (2019) n°N1, 613 (drawing by the author).

Most of the graffiti written by Cypriot mercenaries in Egypt, however, are dated to the fourth century and come from two locations: Abydos, center of the cult of Osiris, where they are engraved on the pillars and one on the internal stairs of the temple of Seti I – also called Mnemonion – and Karnak, where they are engraved on the walls of Acoris’ Chapel.[38] The higher concentration of Cypriot mercenaries in Egypt in the fourth century is due to the fight between Evagoras I (413–374), King of Salamis, and the Great King, Artaxerxes II. From 391, Evagoras wanted to gain independence from the Achaemenid Empire, or at least extend his rule beyond Salamis, implementing a pro-Athenian policy advantageous to his expansionistic aims.[39] According to Diodorus, he aimed to take over the whole island; therefore, the city-kingdoms of Amathus, Kition and Soloi, feeling threatened, asked help from Artaxerxes. While acknowledging that the geopolitical landscape was considerably more intricate, these events did contribute to the beginning of the ‘Cypriot war’ which ended with a treaty of peace in 376 (Diod. Sic. 14.98.1–2). In those years, Evagoras allied with Acoris, pharaoh of Egypt, who, in turn, aimed to consolidate his independence from the Persian Empire (Xen. Hell. 4.8.24; Diod. Sic. 15.2–3). Acoris supported Evagoras’ geo-political operations until 380, shortly before his death, and, according to Diodorus, employed mercenary troops against the Persians, mostly from Greece, also led by the Athenian stratēgos, ‘general’, Chabrias.[40] Conceivably, the Cypriot mercenaries who wrote graffiti on Αcoris’ Chapel served for him in those years. Since most of the Cypriot graffiti from Abydos were engraved by Salaminians, and dated to the same period, plausibly even these writers were Cypriot mercenaries sent to Egypt to support Acoris’ rebellion.[41] Other Cypriot writers come from Ledra – eight of them among those who inscribed Acoris’ Chapel – and five from Paphos, as suggested by the content of the inscriptions; all these cities were somehow linked to Evagoras.[42] Ledra, located in the internal part of the island where now the modern Nicosia stands, was a former city-kingdom which lost its independence in the Archaic Period, probably due to its landlocked position and lack of a harbour for trade. It then became part of the territory of another city-state, very likely Salamis.[43] Paphos allied with Salamis in the ‘Cypriot war’, as suggested by the inscription of Milkyaton’s trophy, a Kition monument which celebrates the naval victory of king Milkyaton and of the Kitians over their enemies, likely the Salaminians, and over the Paphians, their allies.[44]

Along with Salamis, Ledra and Paphos, a few graffiti were written by the inhabitants of Soloi, by inhabitants of Kition – for example ‘BD’ŠMN BN ŠLM HKTY, ‘Abdeshmun son of Shalem the Kitian’, who inscribed his graffito in Phoenician on the Osireion in Abydos – and conceivably by those of Amathus, the inhabitants of which wrote in Eteocypriot.[45] Either these writers where mercenaries who voluntarily joined the troops dispatched by Evagoras, without a formal authorization from the royal governments of their cities – governments that, according to Diodorus, opposed Evagoras’ expansionist ambitions and his allies – or, alternatively, some of the Cypriot graffiti in Abydos were written by occasional visitors.[46]

Graffito engraved on the temple of Seti I (Abydos); Egetmeyer (2010), vol. II, Egypt n°11 = ICS n°376: (1) e-u-ru-te-mi | pa-si-ni (2) •-la-u-o-•-we-sa-se, Ἐρύθεμι(ς) Πασι-..., ‘Eruthemis son of Pasi-...(?),’ @Creative Commons ISAW.

A small amount of Cypriot graffiti in Egypt are written in alphabetic Greek, five of them on the Chapel of Acoris in Karnak, and two in Abydos (fourth century).[47] These graffiti testify to the Cypriots’ ability to use different writing systems and show the existence of mixed Cypriot families, a common phenomenon on the island.[48] One of them reads: Βαλσαμων Φιλοδήμου Λέδριος, ‘Balsamon son of Philodemos from Ledra’. The name Βαλσαμων corresponds to the Phoenician B‘LŠM‘, ‘Ba‘al has listened’, and it has been transliterated from Phoenician into Greek (Karnak n°1). This is not an oddity since in Archaic and Classical Cyprus, Phoenician names are frequently transliterated into Greek and vice versa.[49] The name of Balsamon’s father, Philodemos, is, however, a common Greek anthroponym, and this implies that their family had a complex identity.

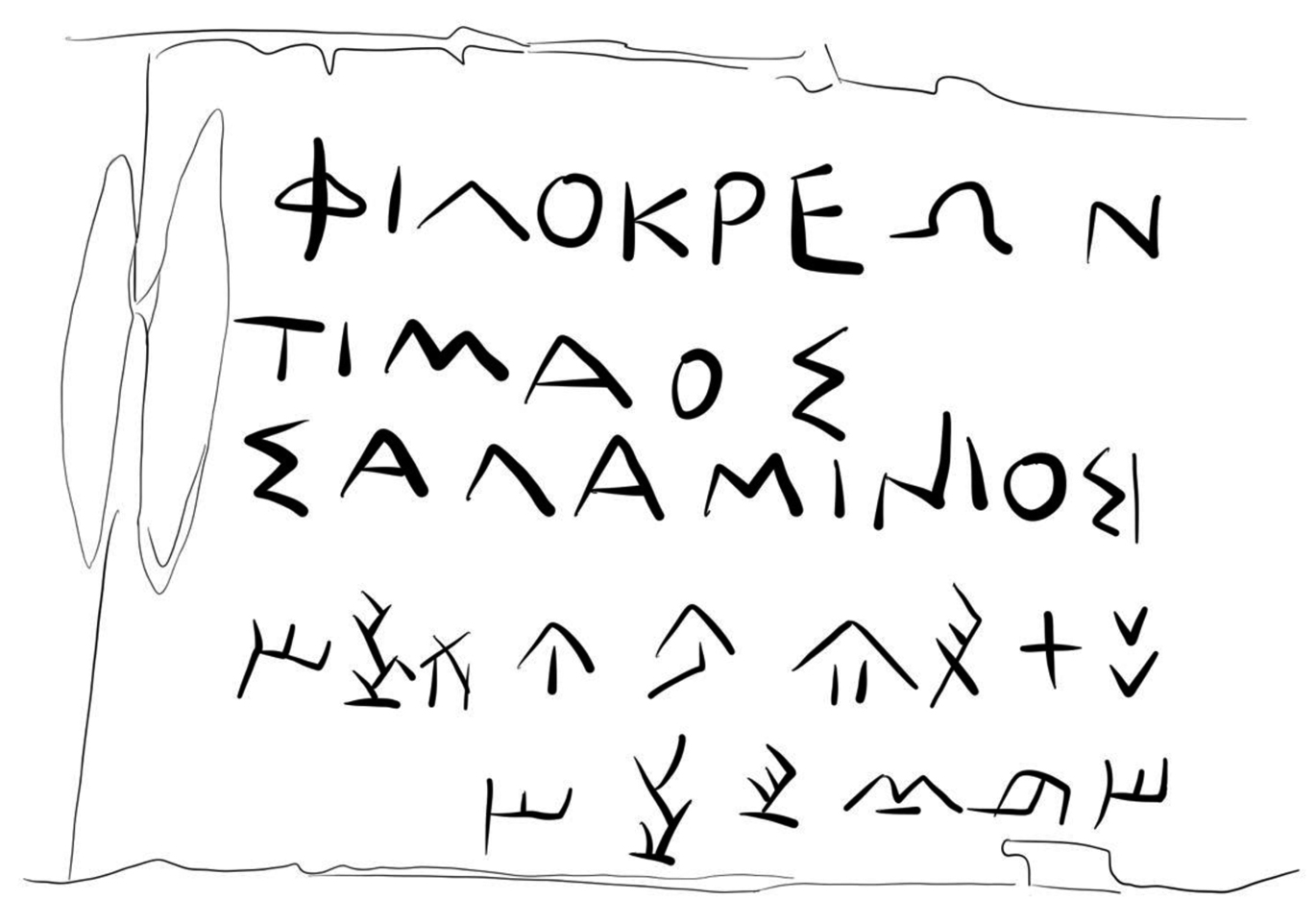

Another graffito from Karnak is digraphic, written in Cypriot-syllabic and alphabetic Greek; it confirms the ability of the Cypriots to juggle different scripts and languages. It reads:

(1) Φιλοκρέων (2) Τιμᾶος (3) Σαλαμίνιος,

Philokreon son of Timas from Salamis,

(1) pi-lo-ke-re-o-[•]-ti-ma-[•]-se

(2) se-la-mi-ni-o-se

(1) Philokreon son of Timas.

(2) Salaminian.[50]

Egetmeyer (2010), vol. II, Egypt n°57 = Karnak n°2 (drawing by the author).

These inscriptions also testify to the level of literacy among Cypriots.[51] Although it is difficult to define to which social class these mercenaries belonged, plausibly they were not members of the elites or related to the kings, otherwise titles would have followed their names; e. g., wanax or adon, in Phoenician, ‘lord’ – in Cyprus, king’s relatives had the titles of wanaktes and wanassai.[52] The ability to write through different writing systems may therefore be ascribed even to individuals of middle-to-low classes.

In the fourth century, Cypriots were undergoing a process of Hellenization, which led to an increasingly frequent use of the Greek alphabet. Nevertheless, the syllabary was regularly employed in everyday writing until the third century.[53] Such Hellenization applied to the whole island, and particularly to the city-kingdoms which adopted Athenian customs for political reasons, such as Salamis, particularly during Evagoras’ government which, as anticipated above, promoted a pro-Athenian policy.[54] By using the Greek alphabet, the Cypriots also adopted a widespread writing system that allowed them to communicate with a larger audience of passers-by who would have read the graffiti, and likely with other fellow mercenaries, perhaps to relate to them. Although the structure of Cypriot mercenaries’ cohorts is not clear, plausibly they have been paired with other foreigner soldiers, mostly Greeks according to Diodorus’ testimony, as happened to the mercenaries who took part in the campaign of Psammetichus II; they were generally called alloglossoi, ‘foreigner speakers’, and not properly distinguished.[55] As Kaplan has suggested, although mercenaries groups in Egypt tended to be divided according to their ethnicity, cultural contacts with home communities and with fellow mercenaries of the same cohort occurred with equal frequency and multilingualism was the main form of cross-cultural contacts among them.[56]

Mercenaries’ graffiti also bear a rich range of toponyms that show the territorial dimension of Cypriots’ sense of community. Mercenaries, however, did not exclusively write the name of the city of origin. In one instance, a graffito also mentions Cyprus, (1) ku-ti-lo-se-le-ti-ri-jo-se-ta-se-ku-po-ro-ne, (1) Κυδίλος Λέδριyος τᾶς Κύπρων, ‘Kudilos the Ledrian of Cyprus.’[57] This is a hapax in the Cypriot corpus, a unique and remarkable document which attests what Cypriot-Greek speakers called the island.[58]

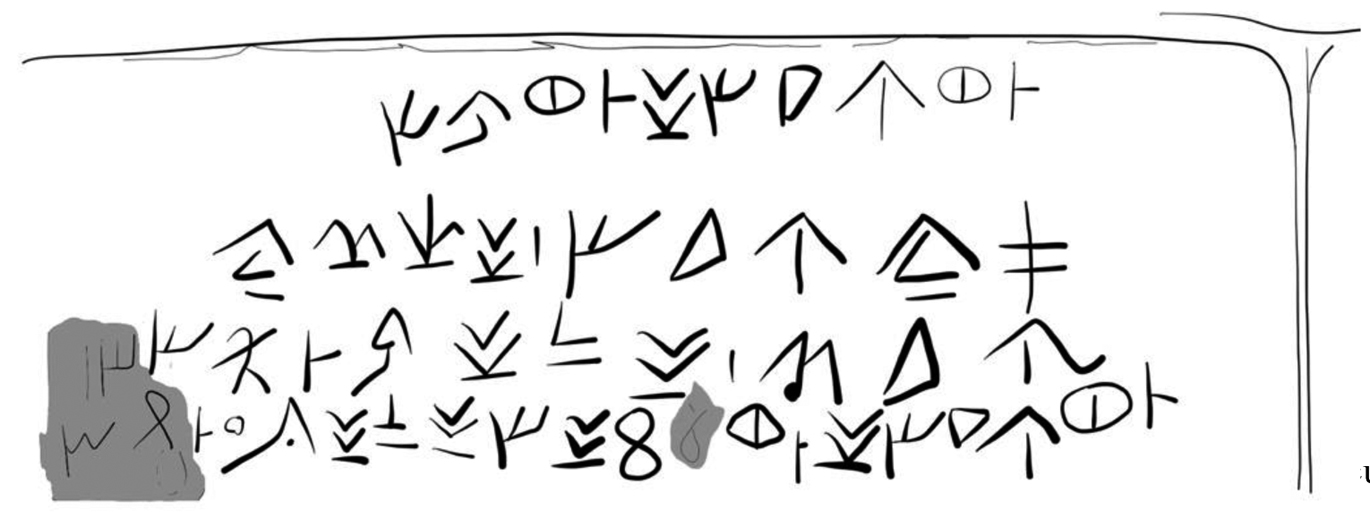

Cluster of Cypriot graffiti engraved on the Chapel of Acoris (Karnak). The first graffito reads: ta-mo-ti-ja-se-o-ta-mo-wo-se, Δαμοθίyας ὁ ΔαμωFός, ‘Damothias son of Damos’; Egetmeyer (2010), vol. II, Egypt n°75 = Karnak n°17; the other graffiti show the demotic ‘from Solipotamia’; Egetmeyer (2010), vol. II, Egypt n°77 = Karnak n°18 = ICS n°430; Egetmeyer (2010), vol. II, Egypt n°78 = Karnak n°19 = ICS n°431 (drawing by the author).

Other graffiti bear the names of villages from which the mercenaries come; these small centres would be otherwise unknown, for example Solipotamia and Kariopotamia, close to Soloi, and the village of Limnis, located in the northwest of Cyprus, which were part of the peripheral districts of the city-kingdoms.[59] Some examples read: (1) pa-si-ti-ja-se | o-te-mi-si (2) ti-ja-u | (s?)o-li-o-po-ta-me-se |,[60] (1) Πασιθίyας ὁ Θεμις (2)τίyαυ Σολιποτάμης,[61] ‘Pasithias son of Themistias from Solipotamia’, and 1) ta-mo-ti-ja-se-o-ta-mo-ke-le-o-se-so-li-o-po-ta-me-se,[62] (1) Δαμοθίyας ὁ Δαμοκλῆος Σολιποτάμης, ‘Damothias son of Damokles from Solipotamia’.

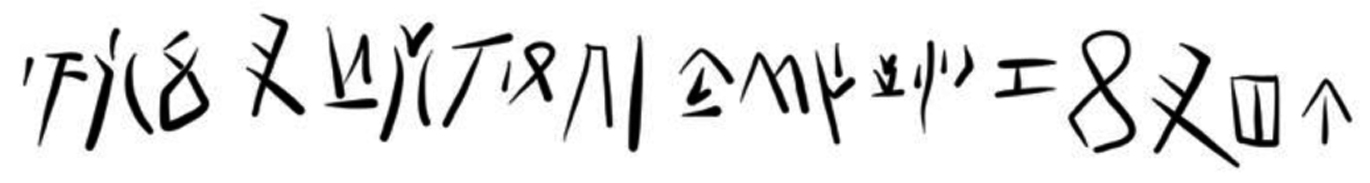

Mercenaries’ sense of community and its relational dimension is also demonstrated by nicknames engraved along with their anthroponyms. The nicknames make the writers identifiable within the subgroup of their cohort and are the results of the camaraderie that developed among the soldiers.[63] A couple of graffiti from Abydos, which bear nicknames, read:

(1) zo-we-se-o-ti-mo-wa-na-ko-to | (?) sa-ka-i-wo-se

(2) zo-we-se-o-no(?)-ta-ma-u-sa-[?[64]

(1) Ζώϝης ὁ Τιμοϝάνακτω, σκαιϝός

(2) Ζώϝης ὁ ...

(1) Ζοwes son of Timowanx, the left-handed

(2) Ζοwes...

Egetmeyer (2010), vol. II, Egypt n°40 = ICS n°405, (drawing by the author).

(1) ti-mo-ke-le-we-se | o-te-mi-si-ta-ko-ro | to-ma-la-ke-le-wi-to |[65]

(1) Τιμoκλέϝης ὁ Θεμισταγόρω τῶ μάλα κλεϝιτῶ[66]

Timokles son of Themistagoros, of the very famous

Egetmeyer (2010), vol II, Egypt n°37 = ICS n°402, (drawing by the author).

Similarly, a Cypriot graffito from Karnark reads: (1) a-ri-si-ta-ko-ra-se (2) ni-ko-ta-mo-o-li-zo-ne, (1) Ἀρισταγόρας (2)Νικοδάμω ὀλίζων, ‘Aristagoras, son of Nicodamos, the youngest’.[67] Finally, in other instances, the repetition of the same name or of the same group of names in a cluster of graffiti may be interpreted as the result of a collective pastime among the soldiers. An illustrative example is the aforementioned graffito by Zowes, in which his name appears at least twice. Similarly, in Abydos on a wall and on the near door, another cluster of graffiti bears the name Zo-o-pa-o-se up to four time: (1) zo-o-pa-o-se-o-•-ke-le-se (2) zo-o-pa-o-se (3) zo-o-pa-o-se, (1) Ζωοφάος ...κλής (2) Ζωοφάος (3) Ζωοφάος, ‘Zophaos the...; Zophaos; Zophaos; (1) zo-o-•-o-se, (1) Ζωο[φά]ος, ‘Zo[pha]os (?)’.[68]

IV Religious tourism and theōria

In the examples provided above, by writing graffiti and tagging the surrounding environment with their languages, writing systems, places of origin, patronymics, and nicknames, Cypriot casual tourists and mercenaries physically and cognitively occupied the place in which they acted and became new societal ‘insiders’, according to the data of Myra, et al.’s sociological analysis.[69] These graffiti, in particular those engraved by mercenaries, however, may also act as a cultural bridge between Cypriot soldiers and new Egyptian customs and practices that they encountered. The choice to engrave them in meeting places frequented also by local devotees – religious tourists or pilgrims – and fellow mercenaries is not accidental. Certainly, the temple of Seti I and the chapel of Acoris in Karnak were well-frequented places of worship. Plausibly, to become societal insiders, in addition to participate as occasional tourists, Cypriot mercenaries also engaged as religious tourists actively taking part in local ritual practices observed among other devotees.[70]

Some of their graffiti may have been written for religious purposes as at least two of them suggest. A graffito engraved in Abydos bears the Greek formula ‘X saw’, X ethēsato (ἐθήσατο) from theaomai (θεάομαι), ‘I viewed’. It mentions Philanos who ‘saw and viewed’: pi-la-no | o-wo-ro-to-ro-•-o-o-[...]-sa-•-•-e-wi-te | ka-se | e-ta-we-sa-to-•-•-e, Φίλανο(ς) ὁ... ἔϝιδε κας ἐθαϝήσατο, Philanos, son of..., saw and viewed’.[71] The formula ‘who saw and viewed’ is commonly employed to describe the ‘sacred contemplation’ or theōria, strictly connected with religious tourism.[72] Comparably, another graffito may bear a similar formula. Its text is: (1) o-po-ke-le-we-se (2) pa-se-ta-we-sa-to-ro (3) e-pa-i-pe (4) •-•-•-se. According to Egetmeyer’s interpretation, it should be read as (1) Ὀ(μ)φοκλέϝης (2) πᾶς ἐθαϝήσατο (3–4) ... (?), ‘Omphokles the son admired’, and not as (1) Ὀ(μ)φοκλέϝης (2) πᾶς Θαϝήσα(ν)δρω (3–4) ... (?), ‘Omphokles son of Thesandros’ as previously interpreted by Masson. The reading of the vowel e in pa-se, either a graphic silent vowel common in the syllabary or an aorist’s augment, remains controversial, as well as the following lines of the graffito.[73]

In Abydos, graffiti with similar formulas have been engraved by Ionians not far away from the Cypriot graffito of Philanos, and, although such a practice was particularly widespread among the Greeks, local Phoenician graffiti also bear the verb ‘to view’, HZY.[74] Likely, these writers were visitors who passed by, stopped in the sanctuary, and decided to write a graffito according to a common religious use, perhaps also driven by the ‘and-me’ instinct.[75] Rutherford stated that the theōria, such a contemplation of sanctuaries, of their artifacts, and of their inscriptions, taught religious devotees and tourists local traditions.[76] Visitors’ theōria and the knowledge of local practices may have contributed to foreign writers’ integration with the new landscapes and to break down the barrier of ‘outsiders’.[77] Mercenaries who stationed at the entrance of the temples to rest or to spend the night may have decided to write these graffiti also to adapt to common customs, and to get involved with local culture and communities to become new ‘insiders’.

All in all, the socio-cognitive analysis of these graffiti can suggest why casual tourists and mercenaries from Cyprus carved their names and provenance on Egyptian monuments in the sixth to fourth centuries. Cypriots found themselves in a completely unknown environment and landscape. Amazed by the majesty of Egyptian pyramids and temples, they left their writings as everlasting memorials. But Cypriots also engraved their names and provenance on these monuments to confront the sense of disorientation caused by the visual impact of the new landscape, to break the barrier of social ‘outsiders’, and become new ‘insiders’ in a previously unknown environment. By tagging the surface of the monuments, the writers physically occupied the space in which they acted and made concrete their origins and belonging to one or more communities, such as that of the Cypriots in Egypt or of the military cohort to which the mercenaries belonged, as demonstrated by the use of nicknames – e. g., ‘the very famous one’, ‘the left-handed’ – with which the soldiers distinguished themselves within their subgroups. Similarly, by carving their names on the Mnemonion of Abydos, Cypriot mercenaries and ‘tourists’ adopted a common practice which allowed them to better integrate with local customs and fellow visitors, mercenaries, and religious tourists and devotees. These graffiti also demonstrated the high level of literacy among the Cypriots, their multilingualism, and their ability to write in different scripts. Finally, these inscriptions provide information about the existence of Cypriot families with more complex ethnic identities, such as that of Balsamon who was also part Phoenician, and villages located in the peripheral territories of the city-kingdoms, e. g., Soliopotamia or Kariopotamia, that would be otherwise unknown.

The integration of modern socio-cognitive theories into the analysis of ancient graffiti, coupled with conventional philological and palaeographic approaches, has facilitated a nuanced comprehension of Cypriot society and the internal dynamics of mercenary cohorts, offering new venues for further research. This interdisciplinary approach highlights the significance of writing systems and scripts, such as the Cypriot syllabary, as distinctive identitarian elements both in antiquity and in present-day society.

Acknowledgments

This article acknowledges a significant debt of gratitude to Dr. Julia Hamilton (Macquarie University), who organized the conference ‘Making and Experiencing Graffiti in Ancient and Late Antique Egypt and Sudan’ (NINO, Leiden, December 2021), where this work was first presented. I would like to express my sincere thanks to Sascha and Tashi Stylianou (Art Murals Signs Cyprus), the creators of one of the modern Cypriot-syllabic graffiti featured in this paper, for generously sharing their experiences with me in engaging with the Cypriot syllabary. My appreciation also goes to Dr. Pippa Steele (Cambridge) and Pico Rickleton, whose insights were particularly inspiring during the ‘Writing Around the Ancient Mediterranean: Practices and Adaptations’ conference (WAMPA, Cambridge, 2021). I am deeply grateful to The Haifa Center for Mediterranean History (HCMH, University of Haifa) for funding this research, as well as to the HCMH research cluster ‘First Encounters’, led by Prof. Gil Gambash (Haifa) and Dr. David Friesem (Haifa). The final editing of this paper was supported by a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship (ECF-2024–574) at the University of Liverpool.

Bibliography:

Adams, C. “Travel and the perception of space in the eastern desert of Egypt.” In Wahrnehmung und Erfassung geographischer Raume in der Antike, Mainz 2001-2002, edited by M. Rathmann, 211–266. Mainz: Philipp Von Zabern, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

Adiego, I. The Carian Language. Leiden: Brill, 2007.10.1163/ej.9789004152816.i-526Search in Google Scholar

Agnew, J. and J. Duncan. The Power of Place. London: Routledge, 1989.Search in Google Scholar

Agut-Labordère, D. “The Saite Period. The emergence of a Mediterranean power.” In Ancient Egyptian Administration, edited by in J. Moreno García, 965–1027. Leiden: Brill, 2013.10.1163/9789004250086_022Search in Google Scholar

Agut-Labordère, D. “Plus que des mercenaires! L’intégration des hommes de guerre grecs au service de la monarchie saïte.” Pallas 89 (2012): 293–306.10.4000/pallas.914Search in Google Scholar

Amadasi, M. and J. Zamora López. “Pratiques administratives phéniciennes à Idalion.” Cahiers du Centre d'Études Chypriotes 50 (2020): 137–155. 10.4000/cchyp.501Search in Google Scholar

Amadasi, M. and J. Zamora López. “The Phoenician name of Cyprus: new evidence from early Hellenistic times.” Journal of Semitic Studies 63 (2018): 77–97.10.1093/jss/fgx037Search in Google Scholar

Amadasi, M. “Notes d’onomastique phénicienne à Kition.” Cahiers du Centre d'Études Chypriotes 37 (2007): 197–209.10.3406/cchyp.2007.1503Search in Google Scholar

Antonsich, M. “Searching for belonging: an analytical framework.” Geography Compass 4 (2010): 644–665.10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.xSearch in Google Scholar

Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape. Chichester: Wiley, 1996.Search in Google Scholar

Ashmore, W. and B. Knapp. Archaeological Landscapes. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, J. “The graffiti of Dura-Europos: a contextual approach.” In Ancient Graffiti in Context, edited by J. Baird and C. Taylor, 49–68. London: Routledge, 2011. Search in Google Scholar

Baird, J. and C. Taylor. “Ancient graffiti.” In Ross (2016), 17–26.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, J. and C. Taylor. Ancient Graffiti in Context. London: Routledge, 2011.10.4324/9780203840870Search in Google Scholar

Balandier, C. “Salamine de Chypre au tournant du Ve au IVe siècle, « rade de la paix » phénicienne, arsenal achéménide ou royaume grec en terre orientale: le règne d’Évagoras Ier reconsidéré.” In Rogge, Ioannou and Mavrojannis (2019), 291–312.Search in Google Scholar

Bechtel, M. Die historischen Personennamen des Griechischen bis zur Kaiserzeit. Halle: Max Niemeyer, 1917.Search in Google Scholar

Bernard, A. and O. Masson. “Les inscriptions grecques d’Abu-Simbel.” Rev. Ét. Grec. 70 (1957): 1–46.10.3406/reg.1957.3472Search in Google Scholar

Bettalli, M. Mercenari. Roma: Carocci, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

Boyes, P. “Towards a social archaeology of writing practices.” In The Social and Cultural Contexts of Historic Writing Practices, edited by P. Boyes, P. Steele and N. Astoreca, 19–36. Oxford: Oxbow, 2021.10.2307/j.ctv2npq9fw.7Search in Google Scholar

Bucking, S. “Towards an archaeology of bilingualism: on the study of Greek-Coptic education in late antique Egypt.” In Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds, edited by A. Mullen and P. James, 225–264. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2012. 10.1017/CBO9781139012775.011Search in Google Scholar

Cannavò, A. “Mercenaries: Cypriots abroad and foreigners in Cyprus before the Hellenistic period.” In Beyond Cyprus, Investigating Cypriot Connectivity in the Mediterranean from the Late Bronze Age to the End of the Classical Period, edited by G. Bourogiannis, 473–484. Athens: AURA & Kardamitsa, 2022.Search in Google Scholar

Cannavò, A. “The many facets of Cypriot literacy.” In Cyprus, edited by L. Bombardieri and E. Panero, 163–168. Londres: DeArtcom, 2021.Search in Google Scholar

Carter, M. “The idea of expertise: an exploration of cognitive and social dimensions of writing.” Cahiers du Centre d'Études Chypriotes 41 (1990): 265–286.10.58680/ccc19908960Search in Google Scholar

Consani, C. Persistenza dialettale e diffusione della koiné a Cipro. Pisa: Pisa-Serra, 1986.Search in Google Scholar

De Keersmaecker, R. Travellers’ Graffiti from Egypt and the Sudan. Vols. 1–12. Berchem: Gaffito-Graffiti, 2001–2011.Search in Google Scholar

Dindorf, W. Harpocrationis Lexicon in decem oratores atticos, ex recensione. Oxford: Typographeo academico, 1853.Search in Google Scholar

Egetmeyer, M. “Sprechen Sie Golgisch? – Anmerkungen zu einer übersehenen Sprache.” In Études Mycéniennes 2010, edited by P. Carlier, 427–434. Pisa: Pisa-Serra, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Egetmeyer, M. Le dialecte ancien de Chypre. Tome I: Grammaire. Tome II: Répertoire des inscriptions en syllabaire chypro-grec. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010.10.1515/9783110217520Search in Google Scholar

Elvira Astoreca, N. “Escritura e identidad: el caso de Pafos.” In Opera Selecta, edited by A. Balda Baranda and E. Redondo-Moyano. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Universidad del País Vasco, 2018. Search in Google Scholar

Evans, J. Environmental Archaeology and the Social Order. London: Routledge, 2004.10.4324/9780203711767Search in Google Scholar

Evans, G. “Graffiti art and the city: from piece-making to place-making.” In Ross (2016), 168–182.Search in Google Scholar

Fagan, B. From Stonehenge to Samarkand. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2006.10.1093/oso/9780195160918.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Fourrier, S. “Constructing the peripheries: extra-urban sanctuaries and peer-polity interaction in Iron Age Cyprus.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 370 (2013): 103–122.10.5615/bullamerschoorie.370.0103Search in Google Scholar

Gómez-Castro, D. “Ancient Greek mercenaries: facts, theories and new perspectives.” War & Society 38 (2019): 1–18.10.1080/07292473.2019.1524341Search in Google Scholar

Goyon, G. Les inscriptions et graffiti des voyageurs sur la grande pyramide. Le Caire: Société Royale de Géographie, 1944.Search in Google Scholar

Gozzoli, R. Psammetichus II, Reign, Documents and Officials. London: Golden House, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

Graham, A. “Reading visual cues on the so-called Archive Wall at Aphrodisias: a cognitive approach to monumental documents.” AJA 125 (2021): 571–601.10.3764/aja.125.4.0571Search in Google Scholar

Gusfield, J. Community. New York: Harper, 1975.Search in Google Scholar

Halczuk, A. Corpus d'inscriptions paphiennes. Lyon: MOMA, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, J. Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 1997.10.1017/CBO9780511605642Search in Google Scholar

Hamblin, J. “Behold the amazing, the spectacular, Giovanni Belzoni.” Smithsonian 19 (1988): 80.Search in Google Scholar

Harmanşah, Ö. Cities and the Shaping of Memory in the Ancient Near East. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2013.10.1017/CBO9781139227216Search in Google Scholar

Hasley, H. and A. Young. “‘Our desires are ungovernable’, Writing graffiti in urban space.” Theoretical Criminology 10 (2006): 276–306.10.1177/1362480606065908Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, J. Persian Interventions. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U.P., 2018.10.1353/book.57201Search in Google Scholar

Iacovou, M. “The Cypriot syllabary as a royal signature: the political context of the syllabic script in the Iron Age.” In Steele (2013), 133–152.10.1017/CBO9781139208482.008Search in Google Scholar

Iacovou, M. “Historically elusive and internally fragile island polities: the intricacies of Cyprus’s political geography in the Iron Age.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 370 (2013b): 15–47.10.5615/bullamerschoorie.370.0015Search in Google Scholar

Iacovou, M. “‘Greeks’, ‘Phoenicians’ and ‘Eteocypriots’. Ethnic identities in the Cypriote Kingdoms.” In Sweet Land ..: Cyprus through the Ages, edited by J. Chrysostomides and C. Dendringos, 27–59. Camberley: Porphyriogenitus, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

ICS = Masson, O., editor. Les inscriptions chypriotes syllabiques. Paris: Ecole Francaise d'Athenes, 1983.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobb, M. “Psychology of the visual landscape, exploring the visual landscape: advances in physiognomic landscape research in the Netherlands.” In Exploring the visual landscape, edited by S. Nijhuis, R. van Lammeren and F. van der Hoeven, 41–54. Amsterdam: IOS, 2011.Search in Google Scholar

Kaplan, P. “Cross-cultural contacts among mercenary communities in Saite and Persian Egypt.” Mediterranean Historical Review 18 (2003): 1–31. 10.1080/09518960412331302193Search in Google Scholar

Kaplan, P. “The social status of the mercenary in Archaic Greece.” In Oikistes, edited by V. Gorman, E. Robinson and A. Graham, 227–243. Leiden: Brill, 2002.10.1163/9789004350908_014Search in Google Scholar

Karnak = Masson, O. “Les graffites chypriotes alphabétiques et syllabiques.” In La chapelle d'Achôris à Karnak II/l, vol. II, edited by C. Traunecker, F. Le Saout and O. Masson, 53–71. Paris: ADPF, 1981.Search in Google Scholar

Karnava A. and E. Markou. “Cypriot kings and their coins: new epigraphic and numismatic evidence from Amathous and Marion.” Cahiers du Centre d'Études Chypriotes 50 (2020): 109–136.10.4000/cchyp.500Search in Google Scholar

Keegan, P. Graffiti in Antiquity. London: Routledge, 2014.10.4324/9781315744155Search in Google Scholar

Knapp, B. Prehistoric and Protohistoric Cyprus. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2009.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199237371.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Körner, C. “Silbenschrift und Alphabetschriften im archaischen und klassischen Zypern – Ausdruck verschiedener Identitäten?” In Sprachen – Schriftkulturen – Identitäten der Antike, edited by P. Amann, T. Corsten, F. Mitthof and H. Taeuber, 59–76. Vienna: Institut für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

Körner, C. “The kings of Salamis in the shadow of the Near Eastern empires: a relationship of ‘suzerainty’.” In Rogge, Ioannou and Mavrojannis (2019), 327–340. 2019 b.Search in Google Scholar

Körner, C. Die zyprischen Königtümer im Schatten der Großreiche des Vorderen Orients. Leuven: Peeters, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space. 2nd Ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.Search in Google Scholar

Lidzbarski, M. “Die phönikischen und aramäischen Inschriften in den Tempeln von Abydos in Ägypten.” In Ephemeris für semitische Epigraphik, band 3, edited by M. Lidzbarski, 93–116. Berlin: Degruyter, 1913.Search in Google Scholar

Lidzbarski, M. “Phönizische Inschriften.” In Ephemeris für semitische Epigraphik, band 2, edited by M. Lidzbarski, 153–171. Berlin: Degruyter, 1907.Search in Google Scholar

Lohmann, P. Historische Graffiti als Quellen. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2018.10.25162/9783515122054Search in Google Scholar

Luraghi, N. “Traders, pirates, warriors: the proto-history of Greek mercenary soldiers in the eastern Mediterranean.” Phoenix 60 (2006): 21–47.Search in Google Scholar

Macdonald, M. “Tweets from Antiquity: literacy, graffiti, and their uses in the towns and deserts of ancient Arabia.” In Ragazzoli, et al. (2018), 65–82.Search in Google Scholar

Maier, F. “Priest kings in Cyprus.” In Early Society in Cyprus, edited by E. Peltenburg, 376–391. Edinburgh: Edinburgh U. P., 1989.Search in Google Scholar

Malafouris, L. “Mark making and human becoming.” Journal of Archaeological Method Theory 28 (2021): 95–119.10.1007/s10816-020-09504-4Search in Google Scholar

Malafouris, L. and C. Gosden “Mind, time and material engagement.” In The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture, edited by I. Gaskell and S. Carter, 105–22. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2002.Search in Google Scholar

Morgan, C. “Ethne, ethnicity, and early Greek states, ca. 1200–480 BC: an archaeological perspective.” In Ancient Perceptions of Greek Ethnicity, edited by I. Malkin, E. Gruen and B. Cohen, 75–112. Cambridge: Harvard U. P., 2001.Search in Google Scholar

Mills, C. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1959.10.2307/1891592Search in Google Scholar

Montobbio, L. Giovanni Battista Belzoni. La vita, i viaggi, le opere. Milano: Martello, 1984.Search in Google Scholar

Myra, F., J. Taylor, J. Pooley and G. Carragher. “The psychology behind graffiti involvement.” In Ross (2016), 194–203.Search in Google Scholar

Olivier, J. “The development of Cypriot syllabaries, from Enkomi to Kafizin.” In Steele (2013), 7–26.10.1017/CBO9781139208482.003Search in Google Scholar

Papantoniou, G. “Cypriot autonomous polities at the crossroads of empire.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 370 (2013): 169–205.10.5615/bullamerschoorie.370.0169Search in Google Scholar

Papantoniou, G. and G. Bouroginannis. “The Cypriot extra-urban sanctuary as a central place: the case of Agia Irini.” Land 7 (2018): 1–27.10.3390/land7040139Search in Google Scholar

Papantoniou, G. and A. Vionis. “Landscape archaeology and sacred space in the eastern Mediterranean: a glimpse from Cyprus.” Land 6 (2017): https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/6/2/40.10.3390/land6020040Search in Google Scholar

Peden, A. The Graffiti of Pharaonic Egypt. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2001.10.1163/9789004495678Search in Google Scholar

Perdrizet, P. and G. Lefebvre. Les Graffites grecs du Memnonion d'Abydos. Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1919.Search in Google Scholar

Pestarino, B. Kypriōn Politeia, the Political and Administrative Systems of the Classical Cypriot City-Kingdoms. Leiden: Brill, 2022.10.1163/9789004520431Search in Google Scholar

Petit, T. “Isocrate, la théorie de la mediation et l’hellénisation de Chypre à l’époque des royaumes.” Ktema (2022): 135–154.10.3406/ktema.2022.3065Search in Google Scholar

Pilides, D. and J. Oliver. “A black glazed cup from the hill of Agios Georgios, Lefkosia, belonging to a ‘wanax’.” Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus (2008): 337–352.Search in Google Scholar

Ragazzoli, C. “The Scribes’ Cave: graffiti and the production of social space in ancient Egypt circa 1500 BC.” In Ragazzoli, et al. (2018), 23–36.Search in Google Scholar

Ragazzoli, C., Ö. Harmanşah, C. Salvador and E. Frood, Scribbling through History. London: Bloomsbury, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

Rickleton, C. “Speculative syllabic.” In Writing Around the Ancient Mediterranean Practices and Adaptations, edited by P. Steele and P. Boyes, 222–242. Oxford: Oxbow, 2022.10.2307/jj.3177144.16Search in Google Scholar

Robb, J. “Beyond agency.” World Archaeology 42 (2010): 493–520.10.1080/00438243.2010.520856Search in Google Scholar

Rogge, S., C. Ioannou and T. Mavrojannis, editors. Salamis of Cyprus. Münster: Waxmann , 2019.Search in Google Scholar

Rop, J. Greek Military Service in the Ancient Near East, 401–330 BCE. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2019.10.1017/9781108583350Search in Google Scholar

Rosenmeyer, P. The Language of Ruins. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2018.10.1093/oso/9780190626310.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Ross, J., editor. Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art. London: Routledge, 2016.10.4324/9781315761664Search in Google Scholar

Rutherford, I. State, Pilgrims and Sacred Observers in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2013.10.1017/CBO9781139814676Search in Google Scholar

Rutherford, I. “Pilgrimage in Greco-Roman Egypt: new perspectives on graffiti from the Memnonion at Abydos.” In Ancient Perspectives on Egypt, edited by R. Matthews and C. Roemer, 171–189. London: University College U. P., 2003.Search in Google Scholar

Rutherford, I. “Theoria and Darshan: pilgrimage as gaze in Greece and India.” CQ 50 (2000): 133–146.10.1093/cq/50.1.133Search in Google Scholar

Ruzicka, S. Trouble in the West. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Ryan, D. “A portrait: Giovanni Battista Belzoni.” Biblical Archaeology 49 (1986): 133–138.10.2307/3209994Search in Google Scholar

Sarason, S. The Psychological Sense of Community. Cambridge: Brooklin, 1974.Search in Google Scholar

Satraki, A. “The iconography of basileis in Archaic and Classical Cyprus.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 370 (2013): 123–144.10.5615/bullamerschoorie.370.0123Search in Google Scholar

Senff, R. “The early stone sculpture of Cyprus in the Archaic Age. Questions of meaning and external relations.” Cahiers du Centre d'Études Chypriotes 46 (2016): 235–52.10.3406/cchyp.2016.1687Search in Google Scholar

Stedman, R. “Is it really just a social construction? The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place.” Society and Natural Resources 16 (2003): 671–685.10.1080/08941920309189Search in Google Scholar

Steele, P., editor. Syllabic Writing on Cyprus and its Context. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2013.10.1017/CBO9781139208482Search in Google Scholar

Steele, P. A Linguistic History of Ancient Cyprus. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2013.10.1017/CBO9781107337558Search in Google Scholar

Steele, P. Writing and Society in Ancient Cyprus. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2018.10.1017/9781316729977Search in Google Scholar

Themistocleous, C. “Conflict and unification in the multilingual landscape of a divided city: the case of Nicosia’s border.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40 (2018): 1–21.10.1080/01434632.2018.1467425Search in Google Scholar

Tilley, C. and K. Cameron-Daum. Anthropology of Landscape. London: University College U. P., 2017. 10.2307/j.ctt1mtz542Search in Google Scholar

Traunecker, C., F. Le Saout and O. Masson. La chapelle d'Achôris à Karnak II/l. Paris: ADPF, 1981.Search in Google Scholar

Trundle, M. Greek Mercenaries. London: Routledge, 2004.10.4324/9780203323472Search in Google Scholar

Van Wees, H. “The first Greek soldiers in Egypt: myths and realities.” Brill's Companion to Greek Land Warfare Beyond the Phalanx, edited by R. Konijnendijk, C. Kucewicz and M. Lloyd, 293–344, Leiden: Brill, 2021.10.1163/9789004501751_012Search in Google Scholar

Vittmann, G. Ägypten und die Fremden im ersten vorchristlichen Jahrtausend. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 2003.Search in Google Scholar

Wolinski, A. “Il viaggiatore Ermenegildo Frediani.” Bolletino della Società Geografica Italiana 3 (1891): 90–125.Search in Google Scholar

Yon, M. and M. Sznycer, “A Phoenician trophy at Kition.” Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus (1992): 156–165.Search in Google Scholar

Zach, M. “Meroe in der österreichischen Reiseliteratur des 19. Jahrhunderts.” Mitteilungen der Sudan-archäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin e.V. 26 (2015): 277–292.Search in Google Scholar

Zieleniec, A. “The right to write the city: Lefebvre and graffiti.” Environnement Urbain (2016): 1–20. https://journals.openedition.org/eue/1421#quotation10.7202/1040597arSearch in Google Scholar

Zieleniec, A. Space and Social Theory. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2007.10.4135/9781446215784Search in Google Scholar

Zournatzi, A. “Smoke and mirrors: Persia’s Aegean policy and the outbreak of the ‘Cypriot War.” In Rogge, Ioannou and Mavrojannis (2019), 313–326.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Ethnic Identity in the Archaic Arcadian Mountains

- “I see wonderful things!” Socio-cognitive experience of Cypriot graffiti in ancient Egypt

- Pompey, Theophanes and the Contest for Empire

- Sulla’s Example: Remembering a Dictator in the Late Republic and Beyond

- Roads to Empire: on roadbuilding traditions in ancient Rome and early China

- Flavian feathers: expressing dynasty and divinity through peacocks

- Sulpicius Alexander and the Soldier Historians of the Later Roman Empire

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Ethnic Identity in the Archaic Arcadian Mountains

- “I see wonderful things!” Socio-cognitive experience of Cypriot graffiti in ancient Egypt

- Pompey, Theophanes and the Contest for Empire

- Sulla’s Example: Remembering a Dictator in the Late Republic and Beyond

- Roads to Empire: on roadbuilding traditions in ancient Rome and early China

- Flavian feathers: expressing dynasty and divinity through peacocks

- Sulpicius Alexander and the Soldier Historians of the Later Roman Empire