Abstract

Stance-taking in academic writing is now a well-established topic of interest in English language research, with explorations across a range of theoretical frameworks including metadiscourse and systemic functional linguistics (SFL). This includes studies investigating second language (L2) stance-taking, particularly those comparing stance features deployed by L1 and L2 English writers. However, studies investigating stance-taking using the APPRAISAL framework for evaluative discursive language across L1 and L2 production are relatively rare. Incorporating the APPRAISAL framework into research on stance-taking enhances our comprehension of evaluative language in academic writing, especially when it comes to cross-linguistic contexts. It also provides useful advantages for language assessment and instruction. In this learner corpus-assisted discourse study, APPRAISAL was used to determine how L1 English speakers and L2 English learners from L1 Vietnamese backgrounds expressed attitudes through their written texts. We also investigate the relationship between use of APPRAISAL resources and expert raters’ perceptions of written stance via a stance rubric. Findings show L2 English students are more explicit in argumentative writing than L1 English writers, despite fewer APPRAISAL choices in L2 texts. Besides, while high-rated texts were associated with more judgemental evaluation and invocation, more personal feelings were expressed in low-rated texts. These findings have implications for the instruction of L2 writers in conveying attitudinal meanings in text, as well as for raters tasked with assessing L2 academic essays for stance.

1 Introduction

Stance, according to the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (n,d.), is “the opinions that somebody has about something and expresses publicly”, while the Merriam-Webster Dictionary (n.d.) defines stance as “intellectual or emotional attitude”, and based on the Collins English Dictionary (n.d.) “Your stance on a particular matter is your attitude to it”. In a similar vein, stance is generally defined as the viewpoints that someone holds regarding something and articulates openly, and stance-taking is how someone expresses such stance in spoken or written communication (e.g. Du Bois 2007; Englebretson 2007; Jaffe 2009). Stance-taking in academic writing has been a topic of interest in a large body of research, explored across a range of theoretical frameworks (e.g., Biber and Finegan 1988, 1989; Biber 2004, 2006a, 2006b; Hunston and Thompson 2000, Hunston 2000, 2007, 2011; Hyland 1998, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2005; Martin and White 2005).

Regarding lexico-grammatical stance markers (as studied by Biber and Finegan), Biber and Finegan’s research centers on the identification and classification of linguistic components (such as adverbs, adjectives, and verbs) that express attitude, emotion, certainty, and uncertainty in the English language. Their research also investigates the evolution of these markers throughout time and the variations observed across different registers and provides a thorough analysis of the lexical and grammatical resources employed to convey attitudes. Regarding relevance to the present study, an essential comprehension of position markers is vital for examining how L1 and L2 English authors, especially Vietnamese learners, utilize these language tools to convey attitudes in their argumentative articles. This study utilizes these insights to investigate the usage and difficulties encountered by Vietnamese L2 authors in employing these markers, in compared to native English speakers.

In terms of analysis and convincing techniques in communication (Hunston and Thompson research), Hunston and Thompson’s research highlights the significance of evaluative language in enhancing the effectiveness and ideological stance of texts. Their study emphasizes the construction of position across several discourse planes and the utilization of corpus-based approaches to analyze these processes. Regarding relevance to the present study, these observations are directly applicable to comprehending the challenges faced by Vietnamese L2 English learners in utilizing evaluative language to effectively develop persuasive arguments. The present study investigates the same evaluation concerns in both first language (L1) and second language (L2) writing, using these theoretical frameworks.

With regards to the pragmatic and disciplinary stance in Hyland’s studies, Hyland’s research investigates the pragmatic expression of perspective in academic writing, namely through the utilization of hedges, boosters, attitude markers, and self-mentions. The research emphasizes the role of these indicators in many academic fields in establishing authorship and managing interpersonal connections. Regarding relevance to the present study, this study utilizes these findings to examine the differences in the usage of posture indicators in essays between Vietnamese L2 learners and native English writers. Comprehending these pragmatic roles aids in elucidating the disparities in stance-taking behaviors between the two groups. In a similar vein, the topic of the studies conducted by Lee and Lydia (2016), Chung et al. (2024), Hong and Cao (2014) is the comparison of metadiscourse and stance in writing between first language (L1) and second language (L2) writers. These studies examine the utilization of metadiscourse and stance markers in writing, specifically looking at how the usage of hedges, boosters, and other evaluative markers is influenced by varying degrees of skill and cultural backgrounds in both first language (L1) and second language (L2) writing. Additionally, they examine the educational consequences of these discoveries for instructing writing to English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students. Regarding relevance to the present study, this study directly addresses these issues by examining and comparing the ways in which Vietnamese second language learners and native English speakers express their opinions and positions. The study’s conclusions on the explicitness and use of evaluative language by Vietnamese learners are based on the overall patterns noticed in these research.

In reference to genre and evaluative language (Swales, Thompson, and Zhou Studies), Swales’ genre analysis and the research conducted by Thompson and Zhou primarily examine how evaluative language shapes academic genres, namely through the utilization of evaluative disjuncts. These studies investigate the manner in which writers establish their place within their works and the academic community by means of their stance. In relevance to the present study, this study aims to investigate how Vietnamese second language (L2) English learners express their opinions in argumentative essays. The analysis will be conducted using the APPRAISAL framework to explore the evaluative language used by the learners. These insights based on genre serve as a basis for comprehending the obstacles that L2 learners encounter in various genres.

In summary, the present study expands upon the generalizations established by previous groups of studies. This research builds upon their findings by utilizing the APPRAISAL framework to examine how Vietnamese L2 learners convey their perspective in their written work. The study aims to fill gaps in current research by particularly examining the APPRAISAL framework and comparing the writing of English as a first language (L1) and English as a second language (L2) learners in a Vietnamese environment. This research contributes to a more comprehensive knowledge of the difficulties and techniques involved in expressing one’s position in a second language (L2). While stance-taking in L2 writing is a very productive research field, most studies adopt a bottom-up approach to both the definition of stance as well as the linguistic analyses involved (e.g. Biber and Finegan 1988; Hyland 2005). These studies cover many perspectives on stance as a term as well as on how to define and analyze stance as a theoretical and linguistic construct. These methods to stance are essentially “bottom-up,” in that they focus on how stance is realized at the lexico-grammar level in order to draw conclusions about the speaker’s or writer’s “stance,” as realized within the text, even though they are helpful in examining writer-reader connections inside texts. Nonetheless, these methods could face criticism for approaching the study of interpersonal meaning from a lexis-first, meaning-second perspective rather than from a “top-down” perspective by examining the decisions speakers and authors make at the discourse semantics level. The present study however investigates the use of stance-taking as outlined in the APPRAISAL framework developed by Martin and White (2005) in English essays produced by first language (L1) speakers and second or foreign language (L2) learners. Martin and White (2005) propose a comprehensive system for the investigation of stance termed APPRAISAL, conveying personal feelings (which are termed ‘affect’), ethical and aesthetic assessment (which is termed ‘judgement’ and ‘appreciation’) as well as source of information (which is termed ‘engagement’) and grading of attitudinal values or propositions (which is termed ‘graduation’). APPRAISAL is theoretically based on System Functional Linguistics (SFL), exploring stance from a ‘top-down’ perspective or meaning-first approach at the level of discourse semantics. Stated differently, APPRAISAL maps language’s capacity for interpersonal meaning-making – specifically, English – at the discourse semantics level. APPRAISAL takes a “meaning-first” approach to the analysis of stance as it is realized in texts, rather than concentrating on the lexical (or lexico-grammatical) realisation of stance, as seen in Biber and Hyland’s approaches. Instead, APPRAISAL analyses stance from the “top down” in terms of the decisions speakers and writers make (or do not make) within the systemic system of meaning-making made available with the APPRAISAL framework. APPRAISAL is readily applicable to the analysis of evaluation in persuasive writing, serving to reveal the intricate linguistic repertoire involved in the production of writers’ arguments. For example, a plethora of research has delved into the challenges faced by L2 English learners in adopting an appropriate academic stance, highlighting their difficulties in effectively conveying evaluations through language. Studies, such as those by Hood (2004), Lee (2006), Wu (2007), and Liu and McCabe (2018), have explored various facets of stance-taking including aesthetic assessment, ethical evaluation, dialogic reasoning, and the influence of native language on L2 writing. These studies collectively reveal that novice L2 writers often struggle with objectivity, showing a tendency towards personal reactions and single-voiced arguments, in contrast to expert writers who prefer a more socially impactful and dialogically open approach. It is worth to note that the genres of student and expert writers are very different and therefore demand different stances. The findings underscore the importance of evaluative language and stance-taking in academic writing, pointing to the need for enhanced guidance for L2 learners in mastering these aspects.

There is already a large body of research investigating interpersonal resource use based on APPRAISAL by using a contrastive approach to the analysis of discourse. However, the majority of this has examined stance in spoken discourse on limited quantities of data (e.g. Bednarek 2008; Eggins and Slade 1997; Martin and White 2005; Page 2003; Thompson and Jianglin 2000). These studies are pertinent to the present study as they offer fundamental insights into the utilization of the APPRAISAL framework for evaluating spoken language. This study expands the application of this approach to written academic texts, with a specific focus on how both native English speakers (L1) and non-native English speakers (L2) use evaluative language in argumentative essays. Gaining insight into the utilization of APPRAISAL in oral communication aids in comprehending and comparing its usage in written communication, particularly when examining the distinctions between native and non-native English speakers. Following Sinclair (2004), corpus linguistic methods have been introduced and combined with conventional discourse analysis to explore stance construction in the relevant literature. For example, Hood (2005a) has compared L2 writing with L1 journal papers, while the L1 production of two different language varieties were contrasted for stance preferences in Geng and Wharton (2016). Nevertheless, only a very few studies have explored stance via APPRAISAL across L1, and L2 English writing produced in similar circumstances and on similar topic(s). Exploring this field has important educational ramifications. By comprehending the differences in posture expression between non-native (L2) and native (L1) English speakers, teachers can create more effective teaching strategies tailored to the needs of L2 learners. This knowledge can be useful in developing writing courses that emphasize the development of evaluative language and stance-taking, which will help L2 students write more effectively and appropriately when expressing their opinions in academic and professional settings. Additionally, this kind of research can help build more focused teaching materials and evaluation instruments that better capture and facilitate the formation of stance in L2 writing, which will ultimately result in more sophisticated and successful language teaching.

In response, this paper explores APPRAISAL in the context of Vietnamese L2 English writers. Studies of academic writing in Vietnam have increased as the need for English as a foreign language has grown over the past two decades (Phan 2011). However, explorations of Vietnamese grammar based on SFL have not been widely conducted and no study has yet fully described how APPRAISAL works in L1 Vietnamese so far. Approaching how L1 English speakers and L2 English learners from an L1 Vietnamese background convey stance based on APPRAISAL across the same writing tasks and performed under similar circumstances would allow L2 writing researchers to determine the issues Vietnamese L2 writers face when employing stance in English argumentative texts, which could then potentially be remedied in future instruction. The method used in the present study, that of a corpus-assisted discourse study (CADS), allows the researchers to investigate this issue across a wider number of participants and texts than would be possible than via traditional discourse analysis, thus potentially enhancing the accuracy and generalisability of our findings.

2 Literature review

2.1 Stance in (L2) writing

Understanding stance in academic writing has attracted a large number of studies in the current literature. Generally, L2 English learners have been found to be struggling when they convey evaluation through their use of language choices. Difficulties of novice writers or low-rated essay takers have also been found in the following studies.

Coffin and her colleagues (e.g. Coffin 1997; Coffin and Ann 2004; Coffin and Mayor 2004) emphasized the obstacles encountered by novice writers or individuals who receive low ratings on essays. These issues include struggles in employing evaluative language, achieving a balance between text structure and interpersonal attitude, and cultivating an authoritative writing style. Moreover, Hood (2004, 2005a, 2005b, 2006 conducted a comparison between stance-taking in L2 English academic writing and expert writing. He observed that inexperienced authors tend to convey their own feelings rather than considering the broader social implications. Second language learners face difficulties in integrating evaluative terminology, expressing intricate evaluations, and conforming their writing to disciplinary standards. In addition, Lee (2006, 2010, 2013, 2015 conducted research on evaluative language in both first language (L1) and second language (L2) English writing. The findings revealed that essays that received negative ratings tend to prioritize personal reactions, whereas essays that received excellent ratings place greater emphasis on societal evaluation and moral conduct. Second language learners encounter challenges when it comes to assessing their own work, organizing their arguments in a logical manner, and effectively utilizing interactive elements of argumentation. Besides, Wu (2007) investigated the manner in which information is communicated in L2 English essays that had good and low ratings. The study revealed that high-rated essays employ more dialogic reasoning and include counterarguments, whereas low-rated essays primarily emphasize the author’s perspective. Furthermore, Liu and McCabe (2018) conducted a comparison of attitudinal meanings in English essays written by native speakers (L1) and non-native speakers (L2). They discovered that L2 English stance-taking frequently exhibits parallels with both L1 English and L1 Chinese. In addition, they observed that low-rated writings tend to incorporate personal feelings. Several overarching conclusions can be drawn from the studies mentioned. Firstly, when it comes to common challenges, L2 English learners, particularly those who are beginners, often face difficulties in properly utilizing evaluative language, retaining objectivity, and employing suitable argumentation techniques in academic writing. Besides, when it comes to variances in stance-taking, there is a clear distinction between low-rated and high-rated articles. The former tend to rely on personal reactions, while the latter employ more complex social and moral evaluations. Regarding cultural influence, the finding that the cultural background of L2 learners affects the way they communicate their opinions, which might create difficulties in conforming to the norms of academic English, consolidates Liu and Furneaux (2014). The findings from these studies have a direct relevance to the investigation in the current research. The present study investigates how Vietnamese second language (L2) English learners convey attitudes in their argumentative essays by employing the APPRAISAL framework. The issues mentioned in the referenced studies, such as the struggle to employ evaluative language and uphold impartiality, are reflected in the findings of the present research. The study’s emphasis on the disparities in stance-taking behaviors between native language (L1) and second language (L2) speakers is consistent with the overall findings of the referenced studies. These findings underscore the necessity of using specific instructional approaches to assist L2 learners in enhancing their academic writing abilities.

Of particular relevance to the present study, to examine how academic writing in L2 English varies from that in L1 Vietnamese, Phan (2011) interviewed four post-graduate Vietnamese students who were studying in Australia and revealed interesting findings. Her study suggests stance-taking in English was clear, straightforward, and relevant. In addition, English writing style valued simplicity and directness. However, L1 Vietnamese stance choice favoured indirectness and flowery language. Besides, the textual connectedness within Vietnamese texts was weak. Being aware of these major differences can help explain possible difficulties Vietnamese learners might face when they construct their stance in L2 English academic writing.

2.2 APPRAISAL

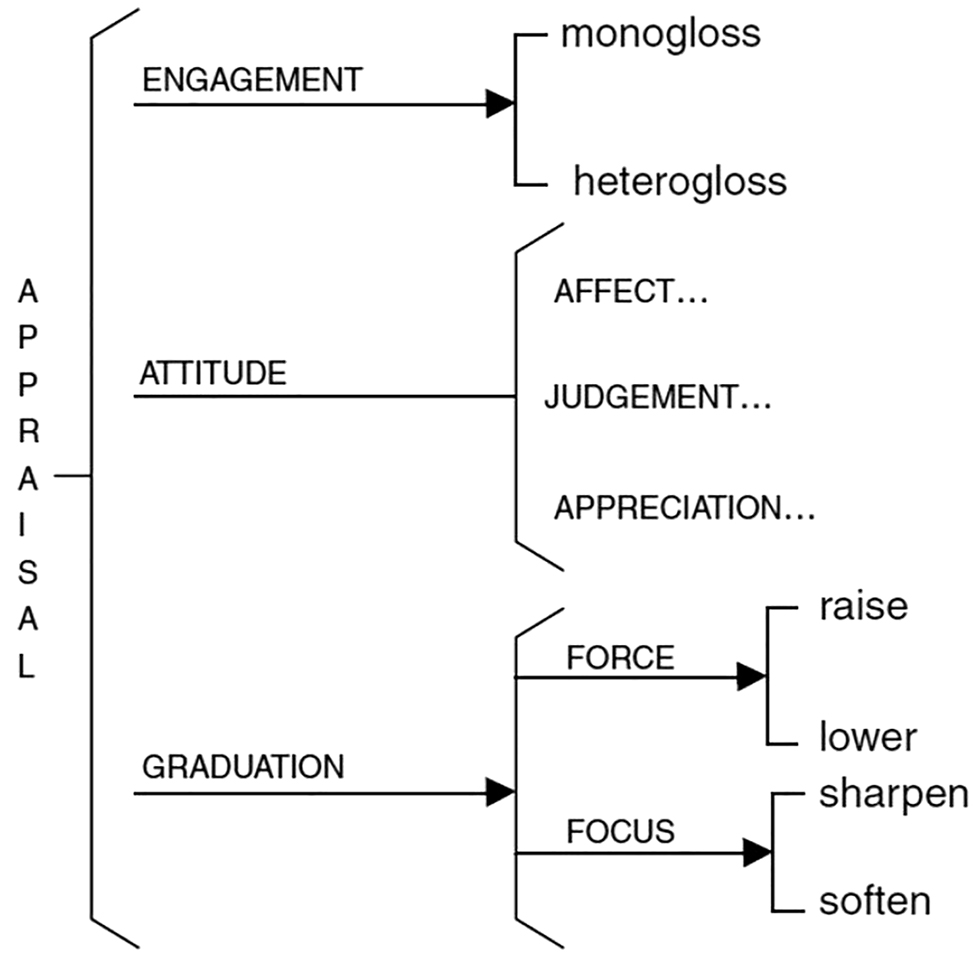

As mentioned, this study adopts APPRAISAL (Martin and White 2005) as an analytical framework for its investigation of stance-taking in L1 and L2 English argumentative essays. APPRAISAL is theorised from SFL, and it provides a full description of the language of evaluation in English. APPRAISAL categorises stance-taking into three domains that are termed attitude (1) which conveys feelings (affect) and evaluation of ethical aspects (judgement) and aesthetic aspects (appreciation), engagement (2) which conveys the source of information – single-voiced argumentation (monogloss) or multi-voiced argumentation (heterogloss) and graduation (3). Graduation not only grades attitudinal values via raising or lowering (force) or non-attitudinal values via sharpening or softening (focus), but it also grades the values of engagement. Figure 1 below outlines the framework of APPRAISAL.

System of APPRAISAL sourced from Martin and White (2005: 38).

Because of the scope of this study, only attitude and graduation of attitudinal meanings are chosen as the coding scheme for stance-taking while engagement will be investigated in subsequent research. On the one hand, understanding attitude is useful in determining if L2 writers are able to communicate complex emotional reactions and critical assessments, both of which are essential for writing that is compelling and interesting. Cultural differences in the expression of emotions and judgments are also revealed by attitude. Compared to native speakers, L2 learners from diverse cultural origins may employ evaluative language in different ways. Teachers can modify their lessons to specifically target the linguistic and cultural difficulties that second language learners encounter by examining these trends. On the other hand, graduation entails fine-tuning the degree or strength of attitudinal connotations as well as sharpening or easing the focus of these assessments. To adjust the effect of evaluative language, this is crucial. Through examining how L2 authors employ graduation, educators can gain insight into how well students can adjust their assessments to fit various rhetorical contexts. This feature is especially crucial for persuasive writing, as changing the arguments’ vigor can strengthen a case or highlight more nuanced issues. Graduation facilitates the expression of nuance in writers’ assessments. It is possible to determine if L2 learners can communicate nuanced changes in emphasis and intensity – two qualities that are essential for complex academic writing – by analyzing how they employ graduation. Teachers can create engaging activities and lessons by taking these subtleties into consideration. Overall, researchers and educators can learn a great deal about the unique difficulties and capabilities of L2 learners by looking at how attitude and graduation are used in L2 writing. This can eventually result in more effective teaching strategies and better writing outputs.

Table 1 illustrates how stance-taking is patterned based on these two domains of APPRAISAL. The resources are taken from Martin and White (2005: 48–56, 137–154). Attitudinal meanings are bolded while grading resources are in italics.

Resources of attitude and graduation.

| Domains of APPRAISAL | Sub-domains of APPRAISAL | Resources | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Affect | Happy, sad, love, hate, long for, fearful, confident, trusting, anxious, startled, satisfied, involved, bored with, flat, etc. | She’s happy. They were bored with action films. |

| Judgement | Lucky, unlucky, powerful, weak, careful, reckless, honest, dishonest, good, bad, etc. | The men were honest. They’re bad bankers. |

|

| Appreciation | Exciting, boring, lovely, ugly, balanced, unbalanced, clear, unclear, effective, ineffective, etc. | The football match is exciting. His approaches were effective. |

|

| Graduation | Force | Very, somewhat, slightly, greatly, more, less, etc. | This upset me greatly. She’s very happy. |

| Focus | True, real, of sorts, etc. | He’s a true friend. It was an apology of sorts. |

With the grading role of graduation resources, attitudinal meanings can be explicitly expressed. Non-attitudinal meanings, however, can also be implicitly conveyed via force or focus. In addition, implicit attitude can be shown via three mechanisms termed ‘flagging’ as realised in the use of graduation resources, ‘affording’ as realised in the use of experiential meanings and ‘provoking’ as realised in the use of lexical metaphors (the following examples in Table 2 are taken from Martin and White (2005: 67)). Implicit attitude is in bold italics.

Explicit and implicit attitude.

| Explicit or inscribed attitude | She’s very happy. The football match is slightly exciting. |

|

|---|---|---|

| Implicit or invoked attitude | ‘Flagging’ | We smashed their way of life. |

| ‘Affording’ | We brought the diseases . | |

| ‘Provoking’ | We fenced them in like sheep . |

While the intensifier ‘very’ explicitly up-scales the affectual meaning of happiness, ‘slightly’ down-scales the meaning of excitement. Contrary to these two examples, ‘smashed’ is non-attitudinal vocabulary, but its intensifying meaning flags a negative moral evaluation. Moreover, the experiential meaning of ‘brought the diseases’ affords a negative behavioural assessment while the lexical metaphor in ‘fenced them in like sheep’ provokes a negative judgement on such humans’ moral issues.

Regarding the impact of ‘topic’ on the expression of attitudinal meaning, the following are some advantages of investigating “topic” in the context of attitude meaning. First, it is essential to comprehend how particular subjects influence the use of evaluative language. Bednarek (2008), for instance, shows that different themes require distinct evaluating procedures by discussing how media topics influence the presentation of emotions and judgments. Second, Hyland (2005) highlights how crucial it is to comprehend how context affects stance-taking in order to create instructional strategies that support L2 learners in modifying their evaluative language to fit various subjects. Third, writing coherence and persuasiveness can be improved by skillfully utilizing evaluative language appropriate for the subject matter. Hood (2006) emphasizes how the interaction between prosodic elements and evaluative language changes depending on the needs of the topic, influencing the writing’s overall impact. Finally, teachers can provide more focused feedback by knowing how topic and evaluative language relate to one another. Thompson and Jianglin (2000) talk about how better feedback procedures might be informed by identifying topic-specific evaluative problems.

2.3 Corpus-assisted discourse studies (CADS)

Studies based on SFL or APPRAISAL heavily rely on qualitative discourse analysis, so they use small amount of data. However, this research attempts to adopt an approach called corpus-assisted discourse analysis (CADS) to explore stance-taking in L1 and L2 English essays. As defined in Ancarno (2020: 165), CADS can “reconcile close linguistic analyses with the more broad-ranging analyses made possible by using corpus linguistic methods of analysis to analyse language. This allows for insights into micro- and macro-level phenomena to be explored simultaneously”. With CADS both quantitative and qualitative analyses are conducted to provide a more comprehensive picture of stance-taking across L1 and L2 writing. CADS has developed since the second half of 1990s to link discourse analysis and corpus linguistics. Specifically, it is considered as a mixed approach. Combining CADS and APPRAISAL analysis for stance can be implemented via two directions. First, scholars can design corpus-driven research in which they employ categories for analysis that are solely derivation from the data. Second, scholars can also design a CADS study in which they employ categories for analysis (e.g., domains and sub-domains of APPRAISAL) that are pre-defined in relation to the corpus data.

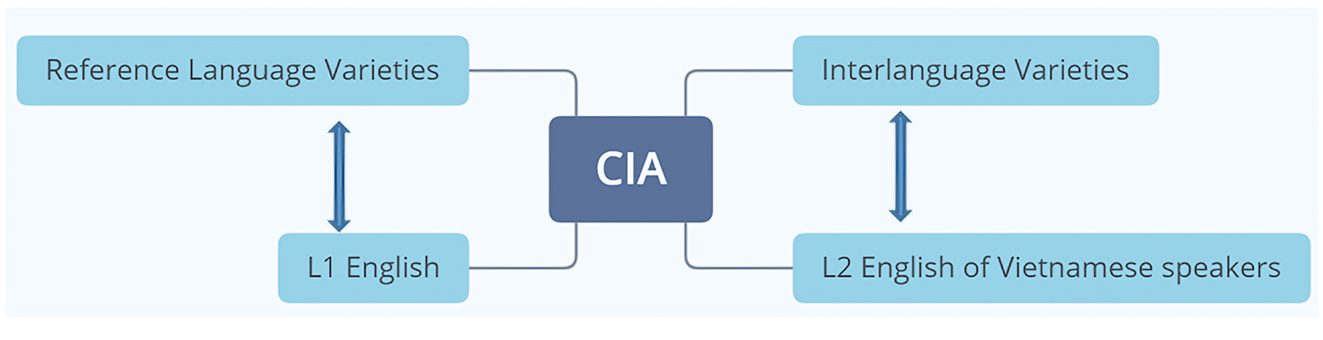

When taking a cross-corpus analysis approach (in this case L1 vs. L2), a Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis (CIA) methodology may be adopted. CIA was initiated by Granger in 1993, consolidated in 1996, and developed in 2002 and 2015. According to Granger (1996: 43), CIA “does not establish comparison between two different languages but between native and learner varieties of one and the same language”. In this model, CIA can be undertaken between the target language (e.g., L1 English) and the interlanguage (e.g., L2 English) on the one hand. On the other hand, interlanguages can be contrasted with one another (e.g., L2 English of Polish speakers versus L2 English of Spanish speakers). Later in 2015, Granger proposed an updated version of CIA called CIA2 in which she introduced the terms ‘Reference Language Varieties’ (RLVs) and ‘Interlanguage Varieties’ (ILs). RLVs can be not only the ‘native variety’ but also the ‘expert variety’ while ILs are considered as the learner’s varieties. ILs, therefore, become more diverse, ranging from learners to required tasks. Neff-van Aertselaer (2016) also suggested that pedagogy and assessment of L2 writing can be improved with the contribution of corpus-based discourse research. She also valued built-in discourse frameworks and recommended making use of such frameworks (e.g. APPRAISAL) to analyse data.

In congruence with Lam and Crosthwaite (2018) and Ancarno (2020), this study prefers CADS for the investigation into stance-taking based on APPRAISAL across L1 and L2 English argumentative writing. Following Neff-van Aertselaer (2016), we adopt a CIA approach to gain insights into L2 English stance-taking with reference to L1 English baseline data, using academic argumentative essays written by speakers of Vietnamese on similar task topics and under similar circumstances. Figure 2 illustrates the CIA model adopted in this research.

CIA model based on Granger (2015: 17).

We also explore the potential relationship between stance-taking and the rating awarded to the writing using a stance rubric developed by DiPardo et al. (2011).

The study aims to address the following research questions:

How do L1 and L2 tertiary student writers express and grade their attitudinal meanings in argumentative texts?

What is the impact of topic on the expression of attitudinal meaning?

Is there any correspondence between the expression of attitudinal meaning and the rating awarded to the students’ texts?

3 Methods

3.1 Data collection

This research undertakes a contrastive learner corpus study of stance-taking based on APPRAISAL (Martin and White 2005) between L1 English essays and L2 English essays written by speakers of Vietnamese on two writing tasks (‘place to work’ and ‘further study’) and under similar requirements (in which tertiary students were asked to produce a 300-word essay within 40 min without any references to dictionaries or resources). Data were collected from volunteer tertiary students in Vietnam (L2 English) and Australia (L1 English). While Australian students were native speakers of English, Vietnamese students were intermediate users. Intermediate users here mean L2 English learners who were at the last stage of level 3 (B1) or early stage of level 4 (B2) based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages.

To guarantee the strength of the study design, the sampling procedures for this research entailed a careful selection of participants and tasks. The sample of Vietnamese tertiary students who were intermediate English users made up the L2 English writers. These volunteers from the humanities, arts, and social sciences studied at a university in the southern region of Vietnam, while the volunteer L1 English writers were native English speakers from a university in northeastern Australia who were mostly from the humanities, arts, and social sciences. This strategy guaranteed a representative and varied sample from both groups. Two distinct writing tasks were selected in order to preserve uniformity and comparability between the L1 and L2 groups. Two essay subjects were assigned to participants: “place to work” and “further study.” These subjects were chosen to allow for a meaningful comparison of stance-taking since they are prevalent and pertinent to postsecondary students’ experiences. The selected sampling techniques have a number of advantages. A more realistic comparison of stance-taking tactics can be achieved by ensuring that the L1 and L2 essays are composed under comparable circumstances. The chosen topics are interesting and pertinent for college students, so they should respond with sincerity and consideration. By minimizing outside influences, standardized writing conditions increase essay comparability. Voluntary recruitment of participants guarantees their real interest and motivation, which is likely to produce higher quality data. When combined, these techniques guarantee a strong research design that permits a significant and well-regulated comparison of stance-taking between L1 and L2 English writers.

The research complies with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies and has been approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board or any equivalent Committee. The collected data formed two separate corpora: one corpus had L2 English data produced by L1 Vietnamese speakers and the other corpus embodied L1 English data written by L1 English speakers. Table 3 presents details for the constructed corpora.

Details for the collected corpora.

| Task | L1 english (L1) | L2 english of Vietnamese speakers (L2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of essays | Words | No. of essays | Words | |

| Further study | 10 | 3,805 | 23 | 6,172 |

| Place to work | 10 | 4,017 | 40 | 9,642 |

| Total | 20 | 7,822 | 63 | 15,814 |

| Total corpus size = (n = 83) | ||||

3.2 Rating of essays for ‘stance’

Both L1 and L2 essays were then evaluated by two essay raters (one rater is a native English speaker who was an Australian tertiary senior lecturer in applied linguistics, and the other rater was a Vietnamese tertiary lecturer in the English language) according to the stance rubric (DiPardo et al. 2011). The stance rubric is a 6-level scale in which level 6 is the highest and level 1 is the lowest. Table 4 presents the adopted rubric to evaluate these essays.

The stance rubric sourced from DiPardo et al. (2011).

| Criteria | Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|

N/A | Low-rated | High-rated | |||

No essay was rated at level 1 or 2, so level-6 and level-5 essays were grouped as the high-rated texts and level-4 and level-3 essays were grouped as the low-rated texts (see Table 5 for details).

High- and low-rated essays.

| Further study | Place to work | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-rated | Low- rated | High- rated | Low- rated | |||||

| L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | |

| No. of essays | 7 | 12 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 22 | 5 | 18 |

Regarding the validity of the coding, 12 full texts (20 % of data) were annotated by the first author, and later they were double checked by two independent interraters. Actually, there were some inconsistencies in double checking invoked attitudinal meanings, but these were resolved on the basis of direct discussions between the two independent interraters and the coder. Then, in congruence with Lam and Crosthwaite (2018), Chung (2022), and Chung et al. (2022), the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was utilised to ensure the reliability of coding agreement. Based on Koo and Li (2016), an ICC(2) of over 0.90 indicates a high level of interrater consistency. Our figure was over 0.95 and thus the annotation of the remaining 80 % of data was allowed to proceed.

3.3 Statistical analysis

To ensure equitable cross-corpus comparisons in our quantitative analysis, we initially converted the raw frequency of each annotated APPRAISAL characteristic into a standardized frequency of ‘n per 1,000-word tokens’ for each individual essay. Subsequently, conditional inference trees (CITs) were created through the R programming language, utilizing the partykit package to examine variations in the usage of attitude and graduation. These variations were assessed with respect to language background (L1 vs. L2), topic (Further study vs. Place to work), and rating awarded (low or high). CITs represent a versatile multivariate approach, yielding easily interpretable results. They follow a recursive data division process, similar to other multivariate tree-based methods, aimed at optimizing predictive accuracy (Baayen et al. 2017). Notably, CITs differ from traditional classification and regression trees (CARTs) by incorporating significance tests to determine the necessity of a specific split. This strategy minimizes the need for pruning (Hothorn et al. 2006). Consequently, CITs help uncover correlations between the predictors and the dependent variable.

The results obtained from CITs were subsequently validated using the glmulti regression program for streamlined model selection, as proposed by Calcagno and de Mazancourt (2010) and Calcagno (2020). This approach considers all input variables and their pairwise interactions when generating unique models. Model fitting is achieved through glmulti and other commonly used R tools. Model selection and multi-model inference are facilitated through the identification of the top ‘n’ best models. Finally, for precise wordings comparison, the Log-Likelihood Calculator (Rayson and Garside 2000) was employed.

4 Results

Table 6 presents the descriptive statistics for the annotated attitude and graduation resources across language background (L1 vs. L2), topic (place to work vs. further study), and stance rating (low vs. high).

Normalised frequencies (n, per 1,000-word tokens) and SDs of high- and low-rated essays.

| Attitude | Graduation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affect | Judgement | Appreciation | Force | Focus | ||||||

| Language background | Language background | |||||||||

| L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | |

| Mean | 6.082 | 10.010 | 11.319 | 8.728 | 34.005 | 36.000 | 20.205 | 18.747 | 0.762 | 0.034 |

| SD | 5.354 | 9.822 | 6.010 | 6.539 | 7.918 | 11.357 | 10.442 | 9.379 | 1.240 | 0.267 |

| Topic | Topic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Further study | Place to work | Further study | Place to work | Further study | Place to work | Further study | Place to work | Further study | Place to work | |

| Mean | 7.092 | 10.365 | 11.078 | 8.213 | 36.331 | 34.984 | 19.345 | 18.936 | 0.266 | 0.172 |

| SD | 4.888 | 10.864 | 6.109 | 6.519 | 8.620 | 11.810 | 8.853 | 10.148 | 0.744 | 0.697 |

| Stance grade | Stance grade | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-rated | High-rated | Low-rated | High-rated | Low-rated | High-rated | Low-rated | High-rated | Low-rated | High-rated | |

| Mean | 11.638 | 6.992 | 8.165 | 10.308 | 33.875 | 36.842 | 16.208 | 21.423 | 0.286 | 0.147 |

| SD | 11.312 | 6.167 | 5.973 | 6.767 | 10.657 | 10.519 | 9.487 | 9.141 | 0.852 | 0.580 |

| Attitude | Invoked attitude | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inscribed | Invoked | ‘Flagging’ | ‘Affording’ | ‘Provoking’ | ||||||

| Language background | Language background | |||||||||

| L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | L1 | L2 | |

| Mean | 39.759 | 47.412 | 11.645 | 7.280 | 8.915 | 6.092 | 2.640 | 1.139 | 0.088 | 0.049 |

| SD | 13.070 | 12.133 | 6.293 | 5.349 | 5.924 | 4.896 | 2.596 | 1.800 | 0.394 | 0.388 |

We now consider the relative impact of language background, topic and rating on writers’ use of attitude resources, beginning with affect.

4.1 Affect

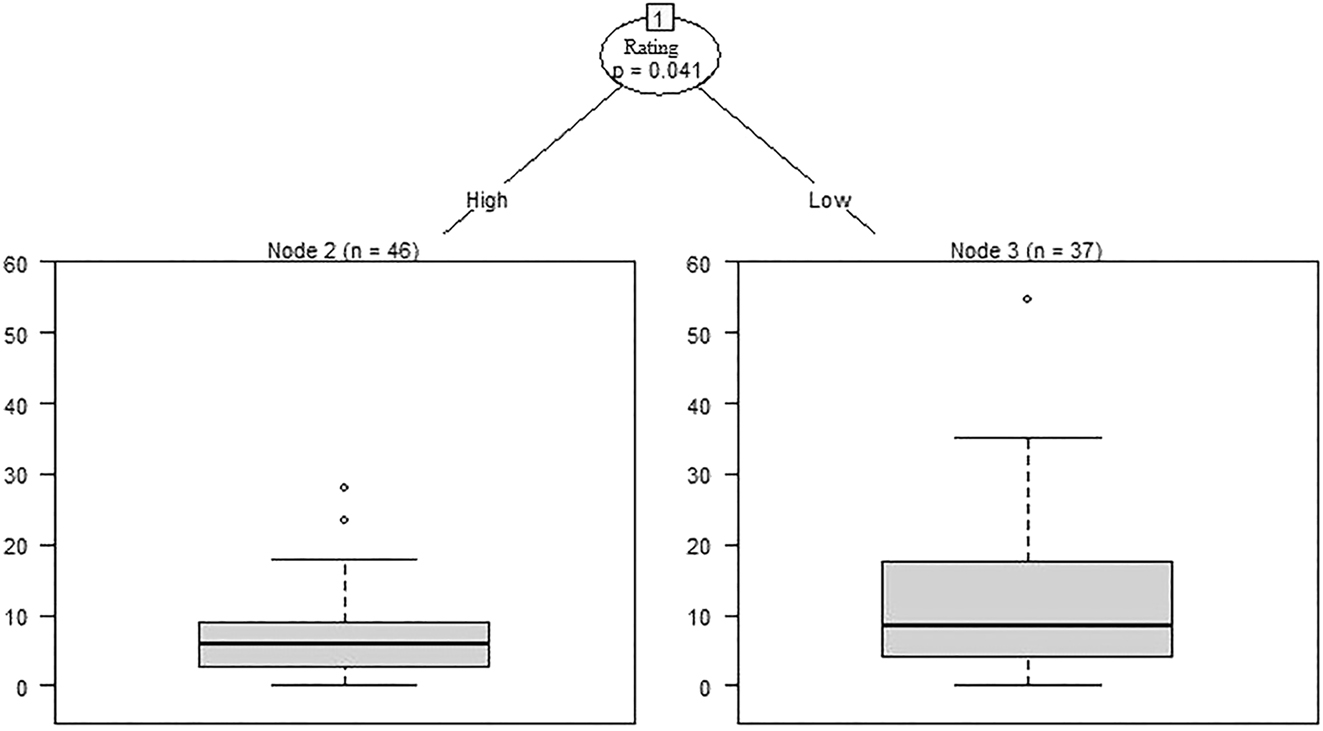

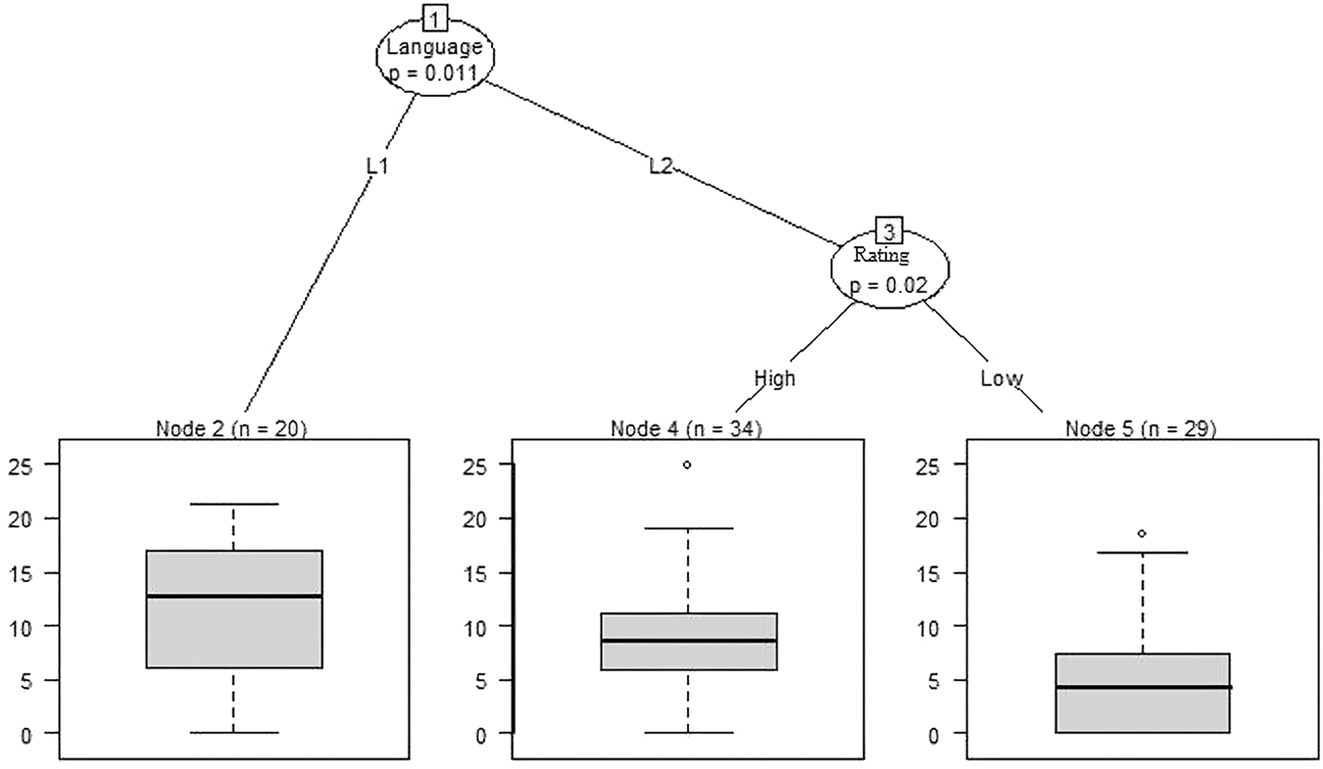

A CIT analysis on the use of affect across topic, language background and stance rating found a potential marginal impact of rating (p = 0.041, Figure 3).

CIT analysis of the impact of rating on use of affect.

A subsequent series of regression analyses were performed (Table 7) using the glmulti package in R. 14 models reached 95 % of evidence weight in total, with 7 models within two IC units. Of these, a model having the intercept, language background and rating as predictors was the preferred model, with an AICC value of 234.72, an evidence weight of 0.14 and a low R2 value of 0.095. Low rating was associated with affect use, at a significance of p = 0.020.

The model’s intercept of language, grade and topic on use of affect.

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.53 | −0.98 to −0.07 | 0.023 |

| Language [L2] | 0.4 | −0.08–0.89 | 0.104 |

| Grade [low] | 0.49 | 0.08–0.91 | 0.02 |

On closer examination, affectual meanings were conveyed in low-rated essays more than those seen in high-rated essays. These affectual meanings were mostly authorial feelings. For example, Excerpt A.1 (see Appendix A) is a low-rated rated essay produced by an L2 learner.

The writer expressed their personal feelings in the body paragraphs. Positive feelings were conveyed when the writer reasoned their preference for working in the countryside, such as ‘love’, ‘warm’, ‘happy’, ‘want’, ‘relax’, ‘enjoy’. Intensifiers ‘very much’ and ‘truly’ were adopted to up-scale the writer’s ‘affect’ and satisfaction. The only argument for not supporting a workplace in the city is that the writer felt frustrated with traffic congestion, noise and pollution in the city. The predominant presence of personal feelings seems to make the arguments less objective and weak.

4.2 Judgement

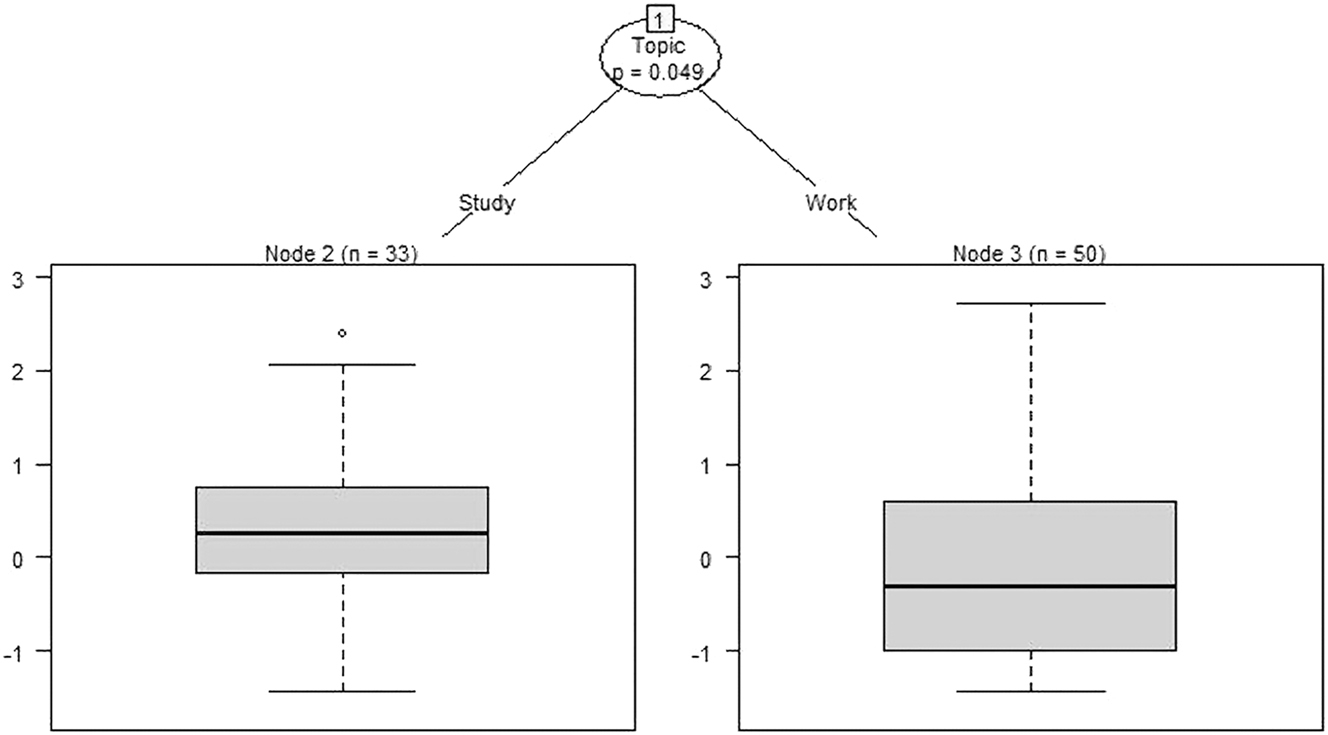

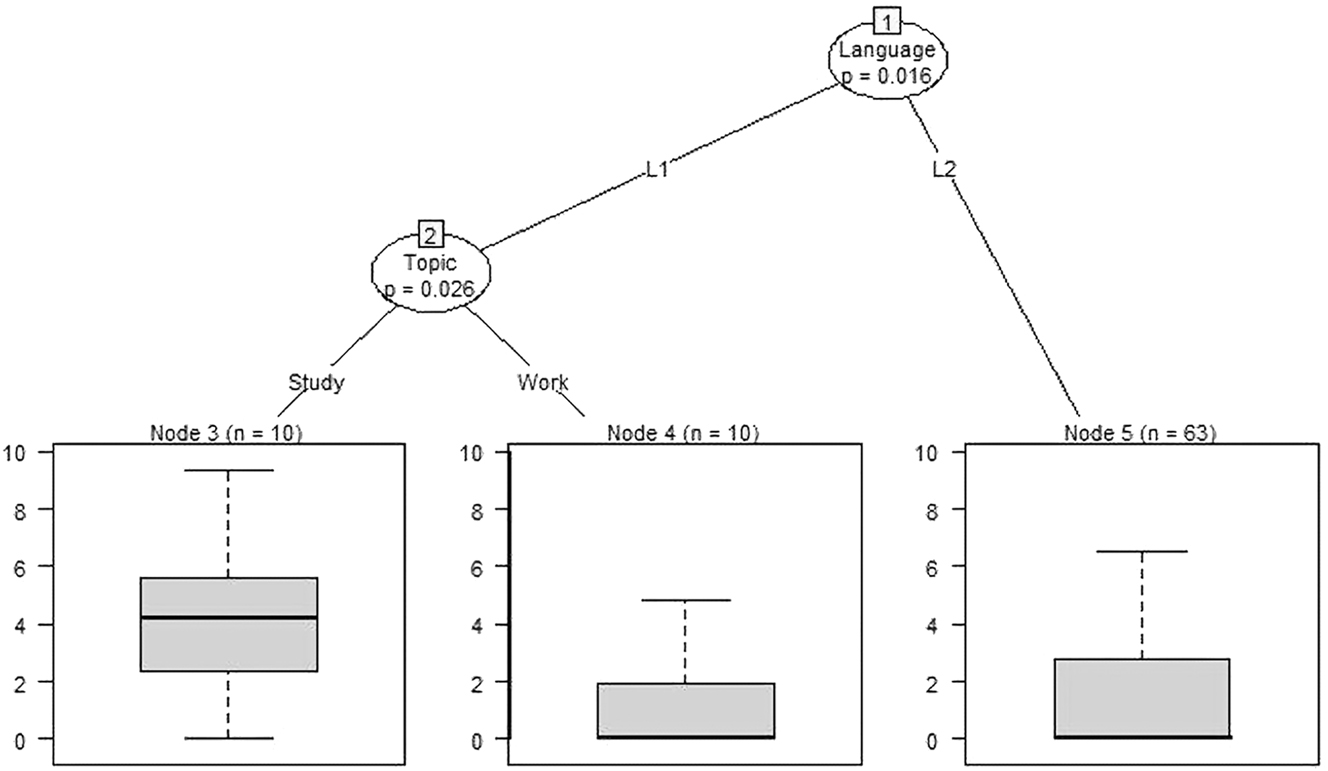

Another CIT (Figure 4) indicated a weak but significant weak correlation between topic and use of judgement.

CIT analysis of the impact of topic on use of judgement.

A subsequent series of regression analyses were performed (Table 8). 10 models reached 95 % of evidence weight in total, with 4 models within two IC units. Of these, a model having the intercept, language background [L2], rating [low], topic [place to work] and the interaction of topic [place to work] * rating [low] as predictors was the preferred model, with an AICC value of 541.63, an evidence weight of 0.28 and a moderate R2 value of 0.177. Judgement use was best predicted by the interaction of topic [place to work] and rating [low], with a significance of p = 0.005, with judgement less likely to be used in texts on the topic ‘work’ with low rating.

The model’s intercept of language, grade and topic on use of judgement.

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.36 | −0.15–0.88 | 0.165 |

| Language [L2] | -0.4 | −0.88–0.07 | 0.098 |

| Topic [place to work] | 0.13 | −0.42–0.69 | 0.633 |

| Grade [low] | 0.43 | −0.22–1.07 | 0.196 |

| Topic [place to work] * grade [low] | −1.2 | −2.03 to −0.37 | 0.005 |

Regarding qualitative interpretations, while judgemental evaluation was rarely conveyed in low-rated essays of the topic ‘place to work’, high-rated essays of the topic ‘further study’ embodied quite a lot of behavioural assessment. For example, in Excerpt A.1, the writer only judged their capacity in ‘I believe that I only do my work well when I truly relax’. However, in Excerpt A.2 (see Appendix A) which was also produced by an L2 learner but was highly rated, the writer made more judgmental evaluation when they reasoned their choice for further study upon graduation. Almost every judgemental evaluation was authorial. Particularly, the writer tended to judge their positive capacity for their study choice. In their arguments, benefits gained from further study in a developed country will lead to the writer’s positive competency in both their academic and professional development. Distinctively, the writer made only one non-authorial judgement on the teaching staff of the institution in Australia or Canada or the US by assessing how special the teachers are. ‘Famous teachers’ were used to both reason a helpful point that their choice for further study can offer them and value the faculty members who will be training them.

4.3 Appreciation

Regarding appreciative evaluation, CIT analyses found no effect of language background, topic or rating on the use of appreciation resources, and regression analysis was therefore not conducted. Although the use of this sub-category was quantitatively insignificant, closer exploration suggests that appreciative values were conveyed the most in comparison with affectual or judgmental meanings across L1 and L2 essays. This can be seen in Excerpts A.1 and A.2. In Excerpt A.1, the low-rated essay taker appreciated work in the countryside as ‘interesting’ and their work competence in the rural setting as ‘the most important’. However, this writer de-valued the opportunity to work in the city as ‘not … more convenient’ or ‘not … better’ compared to work opportunities in the countryside. In Excerpt A.2, the high-rated essay taker favoured making social valuation on the ‘modern labs’ via ‘helps’ or on the ‘degree’ via ‘more valuable’ or on ‘studying in a developed country’ via ‘better’ or on the writer themselves via ‘improve’. Sometimes, this writer expressed their reaction towards the possibility of their finding ‘a good job’ via ‘easy’ or their speaking ‘to native speakers’ via ‘easily’. The attempt to make pre-dominant appreciative evaluation in both low- and high-rated essays suggests that student writers might be trying to convey an objective stance in their argumentative essays because affective and judgemental evaluation often shows subjective attitude.

4.4 Explicitness of attitudinal meanings

CIT analyses for explicit or inscribed resources with language background, topic and stance rating as predictors were inconclusive, with subsequent regression not performed. However, a CIT (Figure 5) for implicit or invoked resources suggested a significant interaction of language background (p = 0.011) and rating for L2 texts (p = 0.020).

CIT analysis of the impact of language and rating on use of invoked affect.

A subsequent series of regression analyses were performed (Table 9). 10 models reached 95 % of evidence weight in total, with 4 models within two IC units. Of these, a model having the intercept, language background [L2] and rating [low] was the preferred model, with a AICC value of 522.91, an evidence weight of 0.20 and a moderate R2 value of 0.151. Invoked resource use was associated with L1 texts (p = 0.003), and when present in L2 texts it was associated with higher rating (p = 0.032).

The model’s intercept of language and grade on use of invoked resources.

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 12.68 | 10.11–15.26 | <0.001 |

| Language [L2] | −4.21 | −6.96 to −1.46 | 0.003 |

| Grade [low] | −2.59 | −4.96 to −0.22 | 0.032 |

Regarding invoked resources, CIT analysis of ‘flagging’, ‘affording’ and ‘provoking’ were inconclusive for ‘flagging’ and ‘provoking’, although there appeared to be a significant impact of both language background (p = 0.016) and the interaction of language background and topic for L1 texts (p = 0.026) (Figure 6).

CIT analysis of the impact of language and topic on use of invoked affect.

A subsequent series of regression analyses were performed using the glmulti package. Significant variation was found, in which the use of affording was associated with L1 essays with the topic of ‘further study’ (p < 0.0001), and when present in L2 essays affording was associated with the topic of ‘place to work’ (p = 0.001). Closer examination suggests that ‘flagging’ and ‘affording’ were the most adopted strategies across L1 and L2 essays while ‘provoking’ was rarely in use. In L2 high-rated essays, twice as many invoked attitudinal meanings were conveyed. Excerpts (3) and (4) in the following will illustrate some use of the ‘affording’ mechanism while ‘flagging’ examples will be mostly mentioned in the graduation sub-section. Inscribed attitude is in bold while invoked evaluation is in bold italics. In excerpt (3), the L1 English writer explicitly mentioned about both positive (via ‘advantages’) and negative (via ‘disadvantages’) social values of studying in developed countries. However, this writer then focused on the ‘disadvantages’ and implicitly afforded ‘associated costs’ also as a negative point though such negative appreciative evaluation cannot overwhelm the ‘benefits’ of educational pursuit in less-developed nations.

(3) Studying in developed countries such as Australia, Canada and the US has both its advantages and disadvantages over studying in developing nations such as Vietnam and Cambodia, however, overall the disadvantages and the associated costs with studying in developed countries does not outweigh the benefits of studying in developing countries. (Extracted from an L1 high-rated essay)

(4) First, I think working in the city isn’t always good because there is more unemployment than in the countryside … Second, accommodation in the city is expensive for employees … If I am qualified enough, I can survive either in the city or in the countryside. (Extracted from an L2 high-rated essay)

In excerpt (4), the L2 English writer started the body paragraph with an explicit evaluation that city work ‘isn’t always good’. Then, a negative appreciation was flagged via ‘more unemployment’. The second negative appreciative assessment was later afforded via ‘expensive’. Throughout the text, this L2 high-rated essay taker conveysed quite a lot flagged attitudinal meanings and ended with an explicit positive judgement via ‘qualified’ and afforded a positive behavioural assessment via ‘survive’. In brief, the two writers in excerpts (3) and (4) embedded invoked attitudinal meanings in their texts quite well.

4.5 Graduation

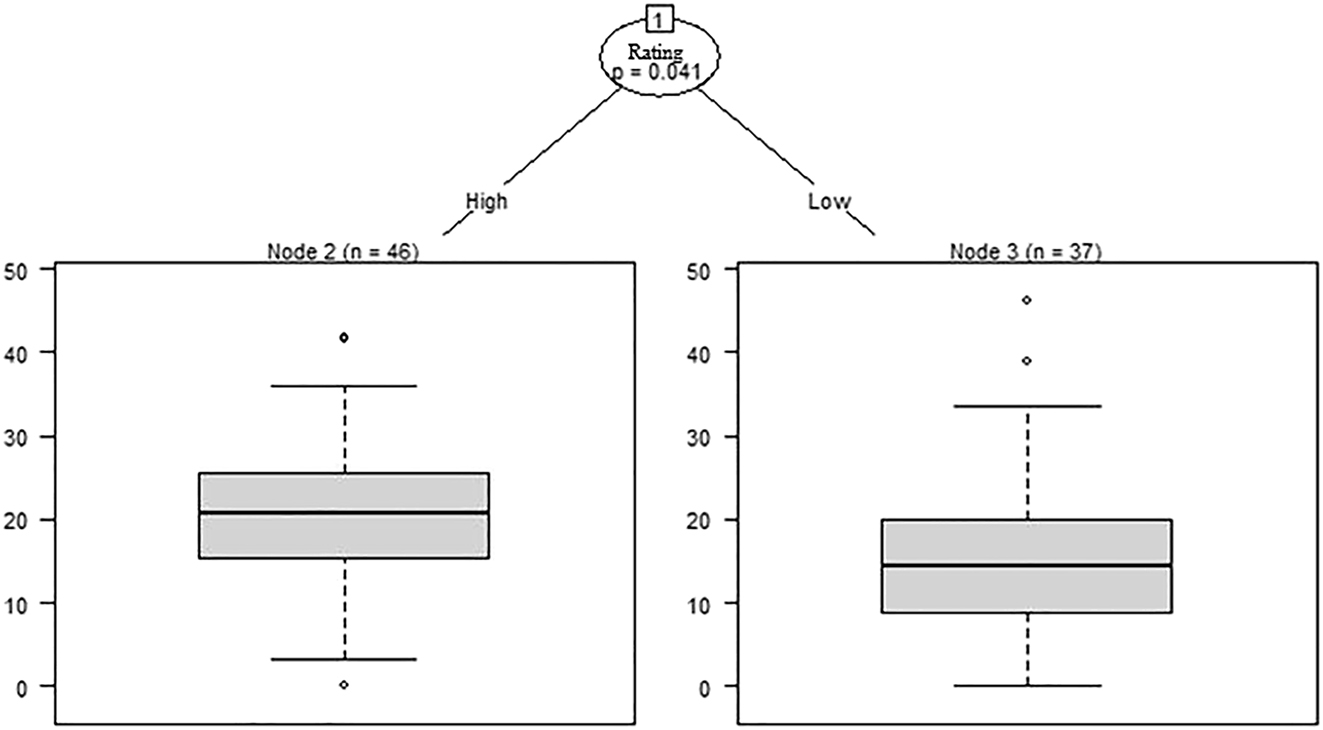

Regarding gradable resources, a CIT analysis for force resources including language background, topic and rating (Figure 7) shows that force was associated with the use of higher rating (p = 0.041).

CIT analysis of the impact of force on use of higher rating.

A subsequent series of regression analyses were performed (Table 10) using the glmulti package in R. 11 models reached 95 % of evidence weight in total, with 2 models within two IC units. Of these, a model having the intercept and rating [low] was the preferred model, with a AICC value of 609.93, an evidence weight of 0.36 and a low R2 value of 0.074. Force use was associated with higher rated texts, with a significance of p = 0.011.

The model’s intercept of grade on use of force.

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 21.42 | 18.74–24.11 | <0.001 |

| Grade [low] | −5.21 | −9.24 to −1.19 | 0.011 |

Excerpt A.1 which is low-rated and Excerpt A.2 which is high-rated help confirm this important finding, re-presented for the reader below. Authorial feelings are in bold while intensifiers are in italics.

In Excerpt A.1 as in “I don’t think working in an urban [area] is more convenient than working in a countryside … I love these very much … I believe that I only do my work well when I truly relax. This is a most important thing … In conclusion, I don’t support the idea that working in the city is better than working in the countryside”, the low-rated essay taker just used force resources five times to grade explicit attitudinal meanings. For example, first, the positive appreciative evaluation ‘convenient’ was up-scaled via the intensifier ‘more’. Then, the intensifier ‘very much’ up-scaled the affectual meaning of ‘love’. Later, the intensifier ‘truly’ was adopted to grade the affectual meaning of ‘relax’ up. The superlative form ‘most’ was after that employed to intensify the appreciative meaning of ‘important’. Finally, the comparative form ‘better’ was adopted to grade the social value of working in the city up. However, force resources in this essay were not used to flag implicit attitude, which is different from Excerpt A.2.

In Excerpt A.2, for example, “… there are many famous teachers. I can study a lot of knowledge … I can earn a lot of money to support me and my family … I can often enlarge my knowledge … I can improve my English … I can also both work and study. I can earn money and experience ”, twice as many force resources as those in Excerpt A.1 were adopted to both inscribe and invoke attitudinal meanings. Particularly, quantifiers were also employed to diversify the scaling of meanings in addition to intensifiers. For example, ‘many’, ‘a lot of’, ‘both’ were used to grade judgemental assessment as in ‘many famous teachers’, ‘study a lot of knowledge’, or ‘both study and work’. Besides, the high-rated essay taker made effective use of infusion that is “there is no separate lexical form conveying the sense of up-scaling or down-scaling” (Martin and White 2005: 143). For instance, the writer judged their capacity via the infused process ‘enlarge’ and then intensified this behavioural evaluation via the infused modal of usuality ‘often’. Later, the writer made appreciative assessment via the infused process ‘improve’. Furthermore, an invoked judgemental evaluation was flagged via the quantifier ‘a lot of’ as in ‘earn a lot of money’. The high-rated essay was well associated with the use of force resources.

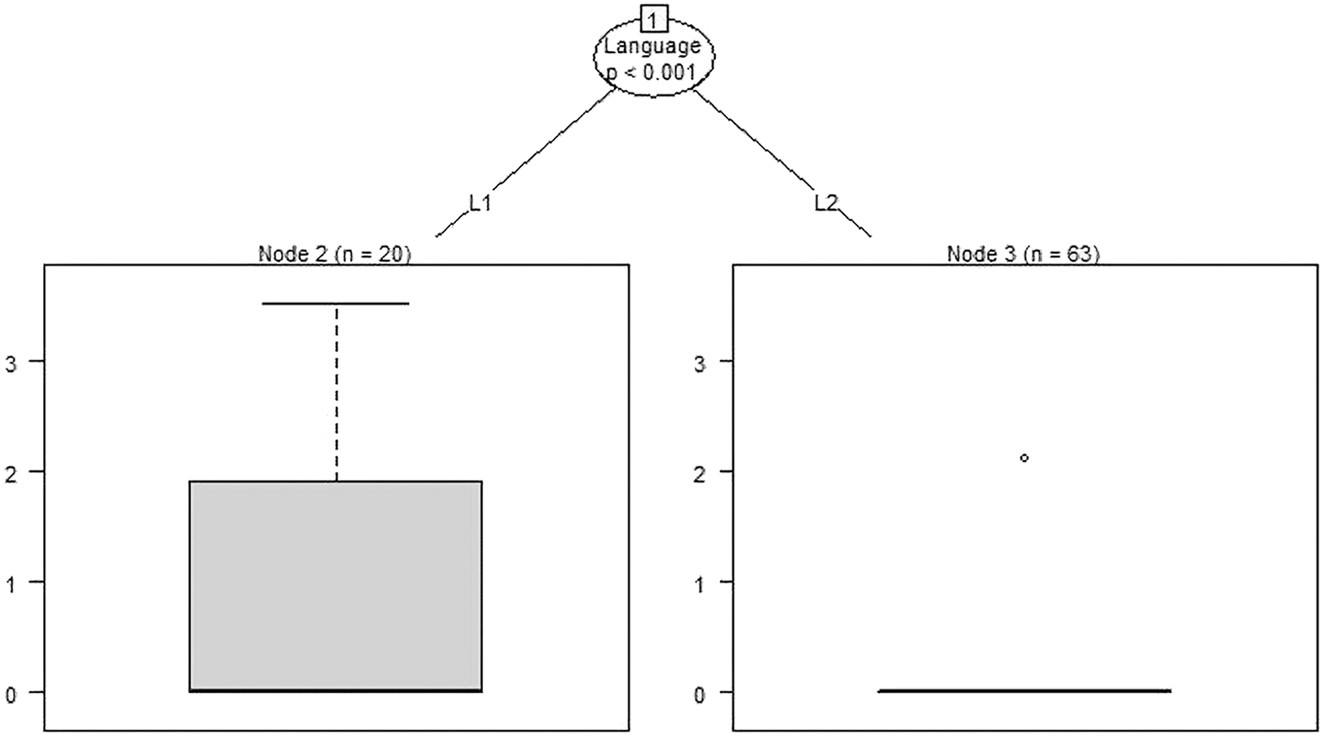

A CIT (Figure 8) for focus resource use suggested a significant impact of language background, with L1 texts much more likely to have focus resources (p < 0.001).

CIT analysis of the impact of language on use of focus.

A subsequent series of regression analyses were performed (Table 11) using the glmulti package in R. 8 models reached 95 % of evidence weight in total, with 3 models within two IC units. Of these, a model having the intercept and language [L2] was the preferred model, with an AICC value of 166.85, an evidence weight of 0.29 and a moderate R2 value of 0.193. Focus use was rarely associated with L2 texts, with a significance of p < 0.001.

The model’s intercept of language on use of focus.

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.76 | 0.48–1.04 | <0.001 |

| Language [L2] | −0.73 | −1.05 to −0.40 | <0.001 |

Qualitative analyses confirm that L1 essays were more associated with focus resources than L2 essays although these resources were far less likely to be adopted in all collected corpora than force resources. For example, in excerpt (5), the L1 English writer softened the experiential meaning of ‘close’ and flagged an implicit appreciation for the ‘suitable school’.

(5) When children inevitably become part of the picture a parent must find a suitable school for their children which is relatively close to home and work . (Extracted from a L1 low-rated essay)

(6) I think you can get a lot of useful real-world experiences from living and studying in a culture different from your own. (Extracted from an L1 high-rated essay)

In excerpt (6), the L1 English writer sharpened or up-scaled their voice via the use of ‘real’ to specify the prototypicality as ‘real-world’. By using this focus resource, the writer flagged a positive appreciation of ‘experiences’ resulting from the choice for further study in a less-developed country.

Different from L1 English speakers, L2 learners seldom adopted focus resources in their essays. In a bigger project, Chung (2022) has found that these L2 learners rarely employed such evaluative language in their mother tongue.

There was no clear impact of language background, topic or rating on the use of upscale or downscale resources when conducting CIT analyses. Further regression analyses were therefore not conducted on the use of these resources. In addition, there was little use of soften or sharpen resources in the corpus, and inferential statistical analyses were not performed.

5 Discussion

5.1 How do L1 and L2 tertiary student writers express and grade their attitudinal meanings in argumentative texts?

Overall, both L1 and L2 writers frequently conveyed stance through appreciation (at rates of 34 and 36 per 1,000 words respectively). Although inferential statistics found no significant variation in the use of this resource across these two language varieties, that appreciative evaluation was predominant in L1 and L2 English essays suggests a process of impersonalisation in academic writing (Hood 2004; Hyland 2005; Martin and White 2005). Most student writers preferred making social valuation of the entity under discussion. Evaluating social values contributes to the de-personalisation in academic writing (Martin and White 2005; Hood 2010). However, L2 writers sometimes reacted to the entity in question in ways such as using ‘easy’, ‘interesting, ‘amazing’. According to Hood (2010), reaction is close to personal feelings, and in Hood (2004) novice researchers seemed to rely more on reaction while experts leaned more on social valuation.

However, L2 writers expressed more affectual meanings while L1 English speakers made more judgmental assessment. Affectual meanings involve feelings and emotions, so they seem subjective in argumentation (Hood 2004). As shown in excerpt A.1, evaluative language such as ‘I love’, ‘I want’, ‘I enjoy’ might reduce objectiveness in the argumentative essay. That L2 English learners leaned on affectual meanings more than L1 English speakers is in congruence with the findings from previous studies (Hamam 2020). This stance preference might be attributed to L2 learners’ interlanguage repertoire, requiring further pedagogical intervention within curriculum design to classroom activities (Lam and Crosthwaite 2018).

L1 English speakers adopted more grading resources than L2 writers. Especially, the conveyance of focus, in which the writer attempts to sharpen or soften their (non-)attitudinal meanings, seems to be only associated with essays written by L1 English speakers. The absence of such values in L2 production has been found in the studies of Lam and Crosthwaite (2018), Chung (2022), and Chung et al. (2022). We believe L2 learners from Vietnamese L1 backgrounds often scale-up or scale-down evaluative meanings in their mother tongue, and Chung (2022), Chung et al. (2022), and Vo (2011) have suggested focus resources were in little use in Vietnamese texts. Therefore, this might show L2 English writing instruction should pay more attention to equipping L2 learners with these interlanguage resources.

Regarding explicit attitude, L2 writers expressed more explicit or inscribed attitude than L1 English speakers, while L1 English speakers tended to express more implicit or invoked attitude than L2 writers. L1 English speakers also adopted the three mechanisms of implicitness (‘flagging’, ‘affording’, ‘provoking’) more than L2 writers. This stance preference raises the question if these L2 writers often make implicit evaluation in their mother tongue. In fact, these writers did make implicit evaluation in their mother tongue although at lower frequency than L1 English speakers (Chung, 2022; Chung et al. 2022). Another question is raised on the proficiency level of these learners. While ‘flagging’ and ‘affording’ were used to invoke attitudinal meanings in L2 production, the L2 writers rarely conveyed implicit attitude via the use of lexical metaphors. This may suggest limited interlanguage resources for this method of conveying stance.

In summary, academic writing and applied linguistics have benefited much from the investigation of how L1 (first language) and L2 (second language) tertiary student writers express attitudinal meanings in argumentative papers. Using the APPRAISAL paradigm to compare Vietnamese L2 learners with native English speakers, the study discovers that L2 writers frequently convey personal feelings while L1 writers favor critical assessments. This is consistent with Hood’s (2004) results regarding the dependence of inexperienced writers on personal reactions and implies that L2 learners are still in the early phases of academic writing. Regarding this research’s contributions, first, building on Hood’s research, this study demonstrates how L2 learners are more likely to find affective meanings in contexts that are culturally distinct. Second, it emphasizes the necessity for L2 instruction to concentrate on evaluative language and posture tactics, which is consistent with Hamam’s (2020) research on rhetorical devices. Finally, it contributes to the body of research on the effects of culture on writing styles, reiterating Vo’s (2011) results about reporting discrepancies between Vietnamese and English. Regarding teaching implications, the study suggests incorporating explicit training on evaluative language and stance tactics in L2 teaching, as well as creating curriculum that take into account the linguistic and cultural backgrounds of L2 learners. Notwithstanding certain drawbacks, like a limited sample size and a deficiency of longitudinal data, the study improves knowledge of stance-taking in academic writing and provides guidance for instructional approaches.

5.2 What is the impact of topic on the expression of attitudinal meaning?

Quantitatively, the nature of the writing task has notably influenced stance preference in written discourse. This has also been confirmed in related works in the literature (e.g., Chung, 2022; Chung et al. 2022; Hunston and Thompson 2000; Liu and McCabe 2018; Swain 2010). That both L1 and L2 English student writers favoured making more judgemental assessment in the topic ‘further study’ is in line with the findings from Lee (2006). Lee found that her L2 English essays embodied the most ethical assessment, but Hood (2004) discovered that appreciative evaluation was predominant in the introduction of research papers and bachelor’s dissertations. This difference can be explained based on the academic level of the written discourse. In other words, the introduction section in research articles and bachelor’s dissertations in Hood (2004) are possibly more academic in nature than the 300-word essays of this study and the 1000-word essays in Lee (2006). In addition, while ‘affording’, a mechanism to invoke non-attitudinal meanings, was popular in the topic ‘further study’ in L1 English essays, this stance strategy was predominant in the topic ‘place to work’ in L2 production. L2 learners tended to implicitly judge their mental and physical capacity in the urban working environment. However, L1 English speakers were inclined to afford more negative appreciative evaluation of less-developed countries as a proposed destination for their further study. That L2 learners from Vietnamese background preferred making invoked judgement is contrary to the finding of Dinh (2021) who indicated his Vietnamese students made more invoked appreciation than judgement. Dinh analysed argumentative texts on tourism’s impacts and machine translation written by sophomores majoring in English for Tourism. This incongruity may be due to the different writing tasks in the present and previous studies.

Qualitatively in both writing tasks, some cultural variation can be seen in the stance preference across the groups. For example, while L2 writers favoured conveying their inclination as realised in ‘want’ and ‘hope’, L1 English speakers preferred expressing their satisfaction as realised in ‘appreciation’ and ‘enjoy’. Also, speakers of Vietnamese seem more direct with their prevalence of explicit evaluation, which is contrary to the view that Asian people are indirect in communication (Phan 2011). Likewise, Liu and McCabe (2018) found the Chinese students in their studies also conveyed a lot of explicitness in their L2 English production. In Chung (2022) and Chung et al. (2022), Vietnamese speakers conveyed less inscribed attitude in their mother tongue than that seen in L2 English writing. This may suggest that L2 English learners have been influenced by the English style because of their L2 instruction, or it may also be that L2 writers lack nuanced resources to express stance less directly.

All in all, academic writing and applied linguistics are greatly advanced by research on the ways in which themes influence attitudinal meaning in L1 and L2 English essays. Through an analysis of the ways in which different topics affect stance-taking, the study sheds light on the rhetorical strategies employed by authors who speak diverse languages. Regarding this research’s contributions, first, speaking of topic influence, “further study” themes elicit more critical evaluations from L1 and L2 writers than “place to work,” which is consistent with stance exploration by Hunston and Thompson (2000). Second, in reference to cultural background, the study emphasizes how writers’ cultural origins, especially those of Vietnamese L2 writers, influence their writing styles, which complements Phan’s (2011) work. Finally, the study suggests topic-sensitive writing instruction to assist students in modifying evaluative language according to the subject matter, hence endorsing Dinh’s (2021) genre pedagogy. Regarding teaching implications, curriculum development should assist students in personalizing their evaluative language, including topic-based training and genre awareness by identifying the conventions of various writing styles. Regarding this study’s limitations, only two subjects are covered in the study, emphasizing the need for greater in-depth investigation, while certain ideas might only apply in particular cultural settings, and the study does not monitor alterations in stance-taking.

5.3 Is there any correspondence between the expression of attitudinal meaning and the rating awarded to the students’ texts?

The findings of this research question is discussed in relation with the works of Derewianka (2007), Nakamura (2009) and Lee (2006). To classify high- and low-rated texts, while Derewianka used the end-of-course test results, Nakamura used IELTS criteria. Lee used her own writing rubric, but the authors of this study used the stance-rubric based on DiPardo et al. (2011). There were differences in rating types among different studies, but they shared one similarity that students’ texts were differentiated into high-rated and low-rated essays for overall quality. These high- and low-rated essays were then analysed for stance-taking features based on APPRAISAL to explore if there were specific stance-taking strategies between them, the result of which is of value for both English language instructors and students. Regarding the impact of stance features on inscribed attitude use, that low-rated essays correlated with higher frequent use of personal feelings is in congruence with the findings of Derewianka (2007) and Nakamura (2009). In fact, low-rated essays often embodied authorial affectual meanings such as ‘I want’. However, conventionally personal feelings should be limited the objectification of academic writing. Derewianka also found that low-rated essays often correlated with higher frequency of judgemental assessment while Nakamura found high-rated essays were associated with the prevalent use of appreciation. Nakamura’s finding is in line with Hood (2004), but Derewianka’s is contrary to the finding of this study in which high-rated essays correlated with higher use of judgemental assessment. Higher frequent use of judgement in high-rated texts is in line with Lee (2006). The contradiction can be justified based on the nature of the writing task. This study required students to argue for ‘further study’ or ‘place to work’. Student writers were inclined to judge the university competence, the study destination or the workplace. With the prevalence of judgmental assessment in academic writing, Lee argued that the use of judgement can be considered as a useful criterion to rate L2 written production.

Regarding the impact of stance strategies on invoked attitude use and graduation use, that invocation was associated with L1 essays and high-rated L2 essays raises important considerations. Creating implicit attitudinal meanings is often regarded as more challenging for L2 learners than creating explicit evaluations. This is due to the fact that implicit meanings rely less on the surrounding text and more on the writer and reader’s shared values, necessitating a more varied interlanguage repertoire. These help to explain that low-rated essay takers might find it hard to convey invoked evaluation. Furthermore, that force use was associated with the use of higher rating would correlate with the conveyance of invocation. As shown in Table 6, ‘flagging’ (in which the writer employs gradable resources to flag non-attitudinal meanings) was the most popular stance strategy to express implicit values. With selective use of force resources, student writers can convey implicit evaluation such as ‘earn a lot of money’ in excerpt (2) or ‘real-world experiences’ in excerpt (6).

In brief, the representation of attitudinal meaning in essay evaluations is closely related to academic writing, and research on this relationship advances assessment theory. The study analyzes the relationship between essay ratings and stance-taking traits, providing insight into the evaluative language used by L1 and L2 writers and how it affects writing quality. Regarding contributions, the research indicates that essays with better ratings employ more complex judgmental evaluations and fewer subjective judgments, corroborating Derewianka’s (2007) focus on useful assessment tools. In addition, expanding upon Lee’s (2006) study, it compares L1 and L2 writers to demonstrate how cultural origins affect attitudinal meanings and how they relate to writing quality. Regarding pedagogical insights, according to the study, in order to improve the quality of writing produced by L2 learners in particular, writing education ought to concentrate on helping students employ attitude language. Specifically, to enhance writing quality, curriculum development should include teaching on evaluative resources, and evaluation criteria should include attitudinal interpretations in rubrics to provide more nuanced comments. Regarding its limitations, rather than doing a thorough qualitative examination of reader impressions, the focus of the study is on correlations. Besides, regarding cultural specificity, not all cultural situations will yield results that are universal. Moreover, the study’s static analysis does not monitor how a writer’s abilities change over time. All things considered, the study provides insightful information and recommends more research in a variety of settings.

6 Conclusions

These findings are important because they potentially confirm the validity of the stance rubric recommended by DiPardo et al. (2011). However, while positive findings may encourage further pedagogical intervention, these findings may be viewed as of marginal significance and may signal several issues to be considered. First, the adoption of APPRAISAL and awarded rating are not always correctly discriminated according to the stance rubric. Second, even if the rubric does capture APPRAISAL use, raters may not be sensitive to APPRAISAL when they rate the quality of stance preference. A combination of these issues may affect the decision on high- and low-rated texts. These issues apparently call for further investigation into the correlation of the stance rubric and the use of evaluative language based on the APPRAISAL framework.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of time and facilities from Tra Vinh University (TVU) for this study.

-

Research ethics: The research complies with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies and has been approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board or any equivalent Committee.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

A.1 Excerpt A.1

Sample of an L2 low-rated essay[1]

I don’t think working in an urban [area] is more convenient than working in a countryside because working at a rural area is interesting.

Firstly, when I live and work in the countryside, I feel fresh air in here. There are long rivers, trees. I love these very much. Secondly, I usually visit my family; living near my parents makes me warm and happy. Sometimes I can cook for them by myself. Finally, I used to work in the city. It’s Ho Chi Minh city. I have trouble with traffic jams, noise and pollution.

If I graduate from university, I want to work in the countryside because I believe that I only do my work well when I truly relax. This is a most important thing. I enjoy the countryside with all of its interest.

In conclusion, I don’t support the idea that working in the city is better than working in the countryside.

A.2 Excerpt A.2

Sample of an L2 high-rated essay[2]

Some people say that studying in a developed country such as Australia, Canada, the US, and so on is better than studying in Vietnam/Cambodia. I agree with this statement, because of some reasons.

First, there are many famous teachers. I can study a lot of knowledge. Second, classrooms, teaching aid and other facilities are good. For example, modern labs can help me do experiments. I can access industry 4.0. Finally, my degree is more valuable. Therefore, it is easy for me to find a good job. I can earn a lot of money to support me and my family.

After, I graduate from university, I would consider pursuing my further study abroad. First, I can often enlarge my knowledge. For example, I can learn culture of many countries. Second, I can improve my English. I hope I can speak to native speakers easily. I will live far away from my family, my parent, and I will learn to be independent. I can also both work and study. I can earn money and experience .

I think studying in a developed country is better than studying in Vietnam. I hope I will have a chance to study abroad after I graduate from university.

References

Ancarno, Clyde. 2020. Corpus-assisted discourse studies. In Alexandra Georgakopoulou & Anna De Fina (eds.). The Cambridge handbook of discourse studies, 165–185. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108348195.009Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, Harald, Shravan Vasishth, Reinhold Kliegl &Douglas, Bates. 2017. The cave of shadows: Addressing the human factor with generalized additive mixed models. Journal of Memory and Language. 94. 206–234.10.1016/j.jml.2016.11.006Search in Google Scholar

Bednarek, Monika. 2008. Emotion talk across corpora. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230285712Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Edward Finegan. 1988. Adverbial stance types in English. Discourse Processes 11. 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638538809544689.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Edward Finegan. 1989. Styles of stance in English: Lexical and grammatical marking of evidentiality and affect. Text - Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse 9(1). 93–124. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.1989.9.1.93.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas. 2004. Historical patterns for the grammatical marking of stance: A cross-register comparison. Journal of Historical Pragmatics 5(1). 107–136. https://doi.org/10.1075/jhp.5.1.06bib.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas. 2006a. Stance in spoken and written university registers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5(2). 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2006.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas. 2006b. University language: A corpus-based study of spoken and written registers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/scl.23Search in Google Scholar

Calcagno, Vincent & Claire de Mazancourt. 2010. Glmulti: An R package for easy automated model selection with (generalized) linear models. Journal of Statistical Software. 34(12). 1–29 https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v034.i12.Search in Google Scholar

Calcagno, Vincent. 2020. glmulti: Model selection and multimodel inference made easy. CRAN.R-project. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmulti/index.html (Accessed 3 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Thuy T. 2022. Writing with attitude: a learner corpus study of APPRAISAL resources of Vietnamese and Khmer’s L2 English writing. Brisbane: The University of Queensland Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Thuy T, Bui Luyen T & Peter Crosthwaite. 2022. Evaluative stance in Vietnamese and English writing by the same authors: A corpus-informed appraisal study. Research in Corpus Linguistics 10(1). 1–30. https://doi.org/10.32714/ricl.10.01.01.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Edsoulla, Peter Crosthwaite & Cynthia Lee. 2024. The use of metadiscourse by secondary-level Chinese learners of English in examination scripts: Insights from a corpus-based study. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 62(2). 977–1008. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2022-0155.Search in Google Scholar

Coffin, Caroline. 1997. Constructing and giving value to the past: An investigation into second school history. In Frances Christie & James R. Martin (eds.). Genre and institutions – Social processes in the workplace and school. London: Cassell.Search in Google Scholar

Coffin, Caroline & Hewings Ann. 2004. The textual and the interpersonal: Theme and Appraisal in student writing. In Louise Ravelli & Robert A. Ellis (eds.). Academic writing in context: Social-functional perspectives on theory and practice, 153–171. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Coffin, Caroline & B. Mayor. 2004. Authorial voice and interpersonal tenor in novice academic writing. In David Banks (ed.). Text and texture, Systemic functional viewpoints on the nature and structure of text, 239–264. Paris: L’Harmattan.Search in Google Scholar

Derewianka, Beverly. 2007. Using appraisal theory to track interpersonal development in adolescent academic writing. In Anne McCabe, Mick O’Donnell & Rachel Whittaker (eds.). Advances in language and education, 142–165. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Dinh, Liem T. 2021. Supporting Vietnamese EFL university students’ development of argumentative writing through systemic functional linguistics-based genre pedagogy. Wollongong: University of Wollongong dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

DiPardo, Anne, Barbara Storms & Makenzie Selland. 2011. Seeing voices: Assessing writerly stance in the NWP analytic writing continuum. Assessing Writing 16(3). 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2011.01.003.Search in Google Scholar

Du Bois, John W. 2007. The stance triangle. In Robert Englebretson (ed.). Stancetaking in discourse: Subjectivity, evaluation, interaction, Pragmatics & beyond new series, Vol. 164, 139–182. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/pbns.164.07duSearch in Google Scholar

Eggins, Suzanne & Diana Slade. 1997. Analysing casual conversation. London: Cassell.Search in Google Scholar