Abstract

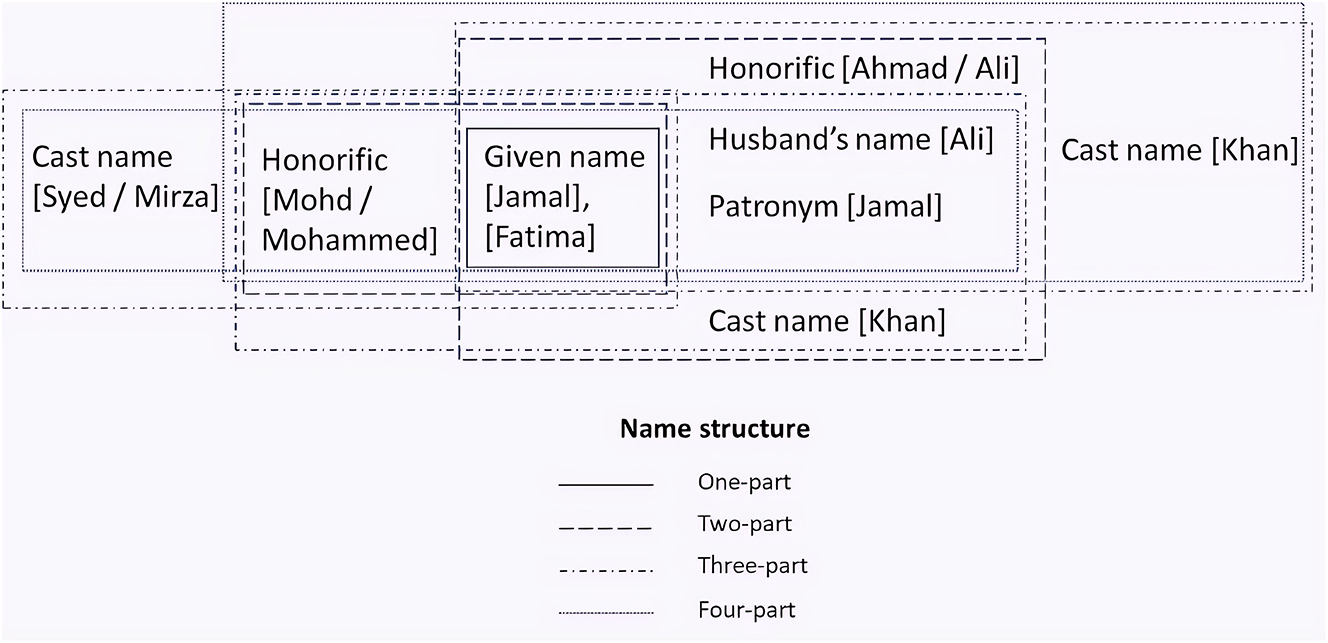

Based on an analysis of a corpus, in this study we examine: (a) the linguistic structure of Muslim personal names, (b) their etymological sources, and (c) some changing patterns among the younger generation. Firstly, we present a typology of the naming patterns by showing that there are four major types – one-part, two-part, three-part, and four-part names. While one-part names are formed from the given name only, the other three types are complex as they are composed of additional names containing honorific titles, caste titles, patronym, and husband’s names in case of married women. Secondly, by examining the linguistic sources of one-part and two part names, we show that Muslim names are primarily derived from Arabic and Persian. Our study further shows that while Indian Muslim names trace their origins to Arabic, the structure of their names differs significantly from Arabs and other Muslims especially those in southern India. Finally, we demonstrate a shift in the naming pattern among the younger generation in that some names and honorific titles are declining. We conclude our paper with some possible social factors that may contribute to the shift.

1 Introduction

In 2008, Mohammad Jalaluddin, a teaboy who worked at the American University of Kuwait, shared with the first author his feelings of disrespect because Arabs in Kuwait addressed him as Mohammad and not Jalaluddin or Jalal as he was called in India. A man bearing this name will not be called by Mohammad, his official first name, because it’s rarely anybody’s given name; it is an honorific that is added to given names as a mark of respect to Prophet Mohammad and a source of blessing from him (Schimmel 1990). When it was explained to him that in Arabic people are addressed by their first names and that it is an honor to be named after the Prophet of Islam, he didn’t look much convinced.

The disrespect that Mr. Jalaluddin felt was clearly based on a misunderstanding rooted in differing naming conventions in India and South Asia at large and the Arab World. While Mr. Jalaluddin expected to be addressed by his given name, which was, in fact, his second name, Arabs in Kuwait, based on the Arabic naming convention, used Mohammad, his first name to address him, assuming that his first name was his given name. Neither of them realized that despite sharing the same religion and a vast majority of Arabic names, the conventions of naming were different in Arabic and Urdu.

Names are significant not only because they serve the practical need of identifying one individual from another but also because they carry significant religious and socio-cultural meanings. Mesthrie (2021, 8) highlights the importance of personal names by arguing that names are “communal and epistemological resources”. Furthermore, many religious traditions have rituals that must be performed before assigning a name to a newborn. In the Hindu tradition, an astrologer is consulted who suggests a suitable name based on the birth star of the newborn because it is believed that names carry spiritual values both in this world and the next (e.g. Chelliah 2005; Jayaraman 2005). In the Islamic tradition, the Qur’an mentions in Chapter-2/31–33 that God favored Adam over the angels because he knew names of things, which angels didn’t. According to this verse, it was the knowledge of names that elevated the mankind to a higher status. There is also a prophetic narration, hadīth, that a newborn should be named on the first or the seventh day and that best male names are Abdullāh and Abdurrahmān (Al-Sijistani n.d.). From a purely sociolinguistic point of view, names carry significant cultural information including religious, ethnic, class, caste, and gender identities.

It is not surprising then that the study of personal names has taken different dimensions. A traditional approach, known as onomastics, was largely limited to the study of the types and etymologies of names (Markey 1982). Recent studies of names, by contrast, encompass a broader range of issues, including the phonetic and grammatical structures of names, their social and psychological meanings and issues of social identities such as gender, class, religion, ethnicity, and region (Mackenzie 2018). Many recent studies of personal names have shown impacts of social factors on names such as urbanization (Mesthrie 2021; Suzman 1994), democratization (Chelliah 2005; Shrestha 2000), and religious, ethnic and caste identities (Bosch 2000; D’Souza 1955; Junghare 1975; Klerk and Lagonikos 2004; Koul 1995; Mehrotra 1982; Mesthrie 2021; Mistry 1982; Parada 2016; Rahman 2013a, 2013b).

As names are carriers of critical social information, they also become tools of social and job-related discriminations. Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004) in their widely cited experimental study found that African-American names such as Lakisha and Jamal were 50 % less likely to get callbacks from potential employers than white-sounding names such as Emily or Greg. There are also studies from the Indian subcontinent showing discrimination and violence, primarily based on names. Faced with housing discrimination in Pune, in the western state of Maharashtra in India, the young Muslim student Ansar Ahmad Khan adopted a Hindu name and only revealed his real Muslim name after he passed the coveted Union Public Service Commission exam for an administrative job (Ahmad 2020a). Based on an experiment, Thorat and Attewell (2007) show that employers of private companies in India favor upper caste Hindus and disadvantage lower caste Hindus and Muslims applicants with equal qualifications. Analyzing Muslims’ perceptions of the negative social consequences of their names, Wright (2006) shows that many Muslims in India chose names that they hoped would help them avoid social and economic discrimination. Based on data from Pakistan, Rahman provides evidence that violent attacks and discrimination against Shia Muslims and Christians contributed to name changes, a phenomenon known as onomastic de-stigmatization (Rahman 2014, 240).

Against this backdrop, taking a broader perspective, this study examines three related aspects of north Indian Muslim names. Based on a corpus of 2,000 names gathered from the website of the Chief Electoral Officer of Delhi, firstly, we describe the complex structural patterns among Muslims in North India. We show that unlike Muslim Arab names (1), which are composed of four parts in which the given name is followed by father’s name, grandfather’s names, and the family name (Abd-el-Jawad 1986; Notzon and Nesom 2005; Yassin 1978), Muslim names in Delhi and north India in general do not follow one single pattern.

| Ali (m)/Aya (f) | Jasim | Mubarak | Al-Ansari |

| Given Name | Father’s name | Grandfather’s name | Family Name |

By contrast names of north Indian Muslims are complex since many names are composed of just the given name, but others can be made up of a maximum of three additional parts. We show that even though about 75 % of the names are of Arabic origin, the structure of north Indian Muslim names shows marked differences from Muslim names in Arabic. We further demonstrate that north Indian Muslim names have a different structure from those in other parts of India such as Kerala, suggesting that Muslims in India have a diverse naming practice based on their regional and linguistic backgrounds.

Secondly, we examine the linguistic sources of Muslim names and show that they predominantly come from Arabic and Persian, which make them look distinct from names of other religious and ethnic groups. Finally, we also show a shift in naming patterns whereby, unlike older people (56 years and older), young men and women adopt father’s names as their patronym. Another noteworthy development is that younger women are less likely to adopt their husbands’ names than older ones. These developments could be the outcome of the linguistic and cultural contact that followed the large-scale labor migration of Indian Muslims to the Gulf states (Shah 2013).

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 gives a general review of the existing work on Indian personal names in general and Muslims in particular. This is followed by Section 3 in which we discuss the sources of the data and methods of analysis. In Section 4, we give a typology of Muslim names and explain the social and cultural meanings of each part. In the next sub-section, we discuss the etymology of Muslims names and show that majority of them trace their origins to Arabic and Persian. The final Section 5, deals with some recent developments focusing on three main changes in Muslim names namely declining use of some honorific names, increased use of father’s name, and the decline of husband’s name among married women. In Section 6 we summarize and conclude the main points and suggests some directions for future research.

2 Study of Indian names

Despite enormous linguistic and cultural diversity that contribute to variations in the structure of names and naming conventions, personal names in India are an under-studied subject (Jayaraman 2005). Studies focusing on personal names of Muslims in India are even more scant, although there do exist some that contain references to Muslim names. The earliest studies of Indian names (Colebrooke 1881; Sinclair 1889) go back to British colonial officers in the late nineteenth century, who were primarily motivated by the practical needs of understanding Indian culture. Later studies by anthropologists largely focused on marginalized tribal groups. Emeneau (1938, 1976 studied the Toda and Coorg tribes of South India and provided a linguistic structure of their names. He showed that an unmarried male and female name starts with the sib-name, followed by father’s personal name with the bearer’s given name appearing as the third element. A married woman’s name differed only in that her name would contain her husband’s sib-name followed by his personal name, with her own given name appearing at the end.

In a comprehensive study of Muslim and Hindu names in the southern state of Kerala, D’Souza showed that a typical Hindu name consisted of four components regardless of whether the family followed the patrilineal or matrilineal structure (D’Souza 1955, 30–31). If a person belonged to the former, the first two slots were filled by father’s joint house name and his name, with the given name coming in the third place. In matrilineal families, known as tarawad in the Malayalam language, the first name was their mother’s house name followed by the senior most maternal uncle, with the given name coming in the third place. D’Souza observed that matrilineal naming system was changing leading to many people using their father’s house name in place of their mother’s and replace their maternal uncle’s name with their father’s (p. 35). D’Souza provides the following typical structure of a Malayali name (2):

| Joint family/House name + Head of Family + Given name + Endogamous group/caste |

In writing, the first two names are often abbreviated because they are not as important. So Vengalil Krishnan Krishna Menon, the first Defense Minister of India wrote his name as V K Krishna Menon. What is interesting is that his given name, Krishna, is the third element of his full name. Although Hindus and Muslims in Kerala speak the same language, Malayalam, D’Souza observes some important differences in the structure of their names. A major difference that marks a Muslim name different from a Hindu one is that the fourth name indicating a Hindu caste doesn’t exist among Muslims since caste is not as socially relevant among Muslims. The other elements of a Muslim name are similar to those of Hindus. A second difference, he points out, is among the Syeds of Kerala, known as Thangal, who are believed to be descendants of Prophet Mohammad; Since the Thangals trace their pedigree to Arabs, they have retained the Arabic naming system discussed above whereby their names start with Syed indicating their lineage followed by given name and father’s name and their original Arabic family name. Influenced by the local naming customs in Malayalam, many Thangals combine the Arabic naming system with the Malayalam one, shared with Hindus, producing a seven-part name in which the first four are based on the Arabic system with the last three on the Malayalam one.

Another study of Muslims names is Koul (1995), who while discussing personal names in Kashmiri in general includes a section on Muslim names. Although his analysis is not based on quantitative data, his remarks that Muslim names are based on Persian and Arabic source are valid. He makes another important observation that in addressing people bearing compound names consisting of two words, one of the two names is dropped. For example, in names with the possessive construction consisting of the word Abdul, meaning ‘slave’, and one of the names of God like al-Aziz, ‘the most powerful’, the first element is dropped, and the person is addressed as Aziz (p. 7). He adds names such as Mohammad Akbar to the above category in which the first name is the honorific and is dropped, and the second name is used to address the person. His analysis runs into trouble when dealing with names such as Gul Mohammad and Bashir Ahmad because in these names it is the first elements Gul and Bashir that are given names which are used in addressing them. Consequently, he puts these names as exceptions (p. 8).

Some studies of Indian names demonstrate influences of ideology and assertion of social identities on the choice of names. While Muslims prefer Arabic and Persian origin names, Hindus avoid them, indicating that the etymology is a marker of identity for Muslims and Hindus.[1] Mistry (1982) in his work on Gujarati names with significant borrowings from Arabic and Persian, noted that Gujarati Hindus avoid names borrowed words from these languages “… even though Gujarati speakers have had long contact with such languages as Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, and English, and though the vocabularies of these languages have penetrated deeply into the language, when it comes to naming a child, borrowed words are avoided” (p. 180).

Chelliah (2005, 12) shows how conversion of the Meithi people of the state of Manipur in northeast India into Hinduism has led to the adoption of the Hindu style of naming whereby Methei names were replaced with Sanskrit-derived Bengali names. The impact of conversion went deeper and impacted the structure of the names as well. Hindu caste names such as Singh replaced the original clan subgroup name. She further argues that recent Meithei renaissance and the associated contestation of the Hindu identities have led to the abandonment of caste titles and reinstatement of the traditional clan names. Mehrotra’s (1982) study of Hindu names shows that while traditional names were based on Hindu gods and goddesses, like Ram and Ganesh, there was a shift towards secular names such as Vikas, meaning ‘development’.

3 Methodology and data

This study is based on an analysis of a corpus of two thousand names from Delhi compiled from the official voter lists, available on the Chief Electoral Officer’s website published on September 1, 2018.[2] Since the goal was to study the structure of Muslim names, they were collected from different Muslim-majority neighborhoods in Delhi falling within four different assembly polling constituencies.[3] We chose four constituencies to ensure representativeness and diversity in names. While the first three constituencies are from working class Muslims living in the walled city of Old Delhi, the fourth one is from an upper middle-class neighborhood in South Delhi. We only included the first five hundred names from each constituency. Table 1 summarizes the sources of the data.

Voter lists from constituencies in Delhi.

| Constituency name | Constituency number | Streets and neighborhoods | Number of voters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chandni Chowk | 20 | Gali Kababyan, Bazar Matia Mahal, Urdu Bazar, Gali Katra Nizamul Mulk | 861 voters |

| Matia Mahal | 21 | Gali Farhat Ullah Khan, Gali Sawar Khan, Gali Jangli Khan | 937 voters |

| Ballimaran | 22 | Gali Mir Madari, Gali Ghanta Kakwan, Gali Anar Wali | 743 voters |

| Kalkaji | 51 | Ishwar Nagar East, Zakir Bagh Apartments | 1,032 voters |

Muslims whose names are analyzed in this paper speak Urdu as their mother tongue. An important feature of Urdu is that it is written in a modified form of the Arabic script and has borrowed a significantly large number of words from Arabic and Persian sources. The voter lists also contained some Hindu and Christian names (n = 49), which were removed from the final corpus. In India Hindu and Christian names are clearly identifiable as they come from Sanskrit and English sources respectively. In addition to voters’ names, the list also contained information about, their age, gender, house number, and their father’s names. A total of 1,951 names were analyzed. The demographics of the people whose names were analyzed are given in Table 2.

Demographics of Muslim voters.

| Age group | Female count | Mean age | Male count | Mean age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19–35 | 303 | 29 | 279 | 28 |

| 36–55 | 426 | 44 | 463 | 45 |

| 56–90 | 214 | 68 | 266 | 68 |

| Total | 943 | 45 | 1,008 | 47 |

The age of participants varied in the range from 19 to 90 years. We divided all participants into three age groups: younger group of 19–35 years (mean age = 29), middle-aged group of 36–55 years (mean age = 45), and older group of 56–90 years of age (mean age = 68). The generational data allowed us to draw conclusions about recent changes in the naming patterns. The proportion of male and female names was almost equal with men forming 51.7 % and women 48.3 %.

4 Structure of Muslim names

We found four major structural patterns: one-part, two-part, three-part, and four-part names; there was only one five-part name in the corpus. Table 3 gives the numbers of each type. Two-part names were the most frequent pattern (71 %), χ2 (4, N = 1,951) = 3,491.36, p < 0.001. One-part (18 %) and three-part names (10 %) were less frequent in the corpus. The name structure, further, varied between the two genders. A chi-square test of independence showed that men and women did not differ in the use of one- and two-part names, but men were more likely (79 vs. 21 %) to have a three-part name than women, χ2 (4, N = 1,951) = 77.51, p < 0.001. Age also affected the name structure, χ2 (4, N = 1,951) = 50.71, p < 0.001. Younger people were more likely to have a name with one part and less likely to have a name with three parts, but people in the older group showed the opposite tendency.

Typology of Muslims names.

| Gender | Age group | # of parts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-part | 2-part | 3-part | 4-part | 5-part | ||

| Female | 19–35 | 94 | 199 | 10 | ||

| 36–55 | 89 | 318 | 19 | |||

| 56–90 | 16 | 186 | 11 | 1 | ||

| Male | 19–35 | 45 | 203 | 29 | 2 | |

| 36–55 | 70 | 321 | 68 | 3 | 1 | |

| 56–90 | 44 | 161 | 54 | 7 | ||

| Total | 358 | 1,388 | 191 | 13 | 1 | |

4.1 One-part names

One-part names, which consist of just the given name, are not uncommon in India and can be seen as a feature of Indian culture in general, especially if compared with Western or Arabic naming conventions. Koul (1995) argues that personal names of Kashmiri Hindus in Sanskrit texts were mostly of single-word structure such as Abhinanda and Bhaskara, for males, and Anjana and Indira for females. The convention of adding a second name began in the late nineteenth century during the British colonial rule.

Linguistic sources of the Muslim names are shown in Table 4. Our data showed that Arabic was the major source (258 or 72 %) for both male and female names. The next major source was Persian (80 or 24 %). Two names (0.5 %) were Hindi, and eighteen (5 %) originated in Hebrew or European languages. The number of names of the Persian origin varied between genders. A chi-square test of independence showed that only names of the Persian origin were more frequent among women than among men, χ2 (3, N = 358) = 46.18, p < 0.001.

Linguistic sources of one-part Muslim names.

| Origin | Gender | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | ||

| Arabic | 116 | 142 | 258 |

| Persian | 69 | 11 | 80 |

| Hindi | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Other | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| Total | 199 | 159 | 358 |

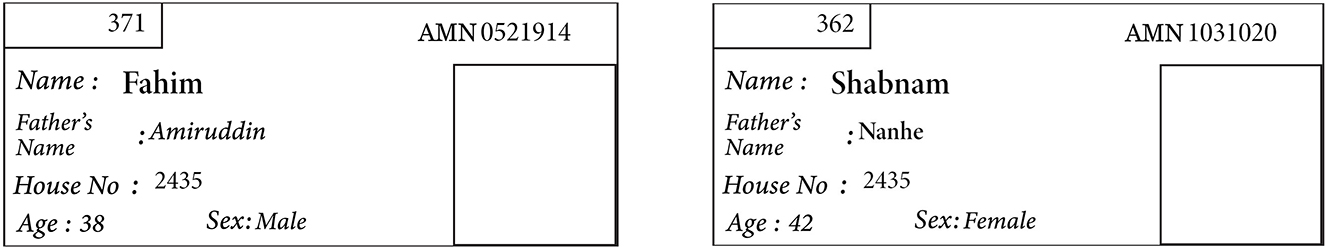

One-part names revealed considerable structural variation. A majority (226 or 63 %) of the one-part names occurred only once in the data suggesting that people preferred names that are unique in some way. One-part names in our data contain either an independent or a compound word composed of two words joined together using the possessive construction known as izāfat (iḍāfa in Arabic). Examples of the former are female names, mostly nouns and adjectives such as Saima, ‘fasting’, borrowed from Arabic and Shabnam, ‘dew’ borrowed from Persian. Examples of male names in this category are Faheem, ‘intelligent’, from Arabic and Javed, ‘eternal’ from Persian. Examples of a male (left) and female (right) one-part names from a voter list in Delhi are shown in Figure 1.

Voter list with a one-part female (L) and male name (R).

Compound names consisted of two or more morphemes, e.g. Abdul Wahid or Mahjabeen. These names are written mostly as one word in English but sometimes also as two words separated by space. The key criterion for treating them as compounds was that both words are needed to complete the meaning of the name. Female compound names were of two types: those that are formed with un-nisā ‘of the women’ compound such as Zebunnisa ‘ornament of the women’ and Mehrunnisa ‘the sun of the women’, meaning the most shining of the women. Mehrunnisa was a wife of the Mughal emperor (1569–1627) who was given the laqab, epithet or nickname, Nūr-i-Jahān, ‘light of the world’. Later we discuss how epithets such as this consisting of a noun or adjective followed by the word Jahan began to be used as given names for women in India. The second type of compound found in the corpus is formed by joining the Persian words gul, ‘flower’ and māh, ‘moon’ with other words. We find words such as Mahjabeen, ‘moon-like forehead’ and Gulafshan, ‘the one who scatters flowers’. Schimmel (1990, 44) points out that names like Gulbadan, ‘rose-body’ and Gulrukh, ‘rose-faced’ were quite common among the Mughal ladies of the sixteenth century.

Some one-part names were compound words consisting of two independent words joined together by the izāfat construction. These were of two types. Firstly, those that consisted of Abd, ‘slave’ and one of the names of God. Names with Abd followed by Allah and Al-Rahman, names of God, for example Abdullah and Abdurrahman, are quite frequent in the Muslim world (Schimmel 1990, 26). In addressing people with these names in India, the Abd part of the name is dropped, and therefore Abdul Rahman and Abdul Hameed are addressed as Rahman and Hameed. It is worth noting that in the Arabic-speaking world, Abdul Rahman cannot be called Rahman as the word refers exclusively to God and cannot be used to rename a human being.

The second type of male compound names consisted of a noun followed by -ud Din ‘of the religion of Islam’ joined by the izāfat construction. Examples include Nāsiruddīn, ‘helper of Islam’, Fakhruddīn, ‘honor of Islam’, etc. which were always written as one word in the voter lists. Schimmel (1990) argues that these given names began their journey as laqab or nicknames, given to people as official honorary titles known as khiṭāb, which gradually developed into given names (p. 60). For example, Nuruddin was the title of the seventeenth century Mughal emperor Salim, also known by the laqab or imperial name Jahangir.

The preponderance of Arabic origin names in the data can be explained in terms of religious and political ideologies of Muslims. Arabic is the scared language of Islam and therefore reverence for it runs deep among Muslims even in non-Arab speaking countries. Schimmel (1990) discusses an interesting name Naṣrun Min Allah, ‘help from God’ in Pakistan which happened because of a custom of naming in which an elder person opens the Qur’an and names the newborn based on the first words they lay their eyes on (p. 25).

4.2 Two-part names

Two-part names consisted of given names with other names, containing important social information, added before or after it. Two-part names, which were most frequent in the corpus (71 %), reveal a diversity of structural patterns, unlike the fixed structure in Western and South Indian names. In two-part names the given name is not always the first element, and the second element may or may not be a patronym. The name of the Prophet – Mohammad, which is often used as an honorific second element in male names, typically comes before the given name, e.g. Mohammad Naseem.

The etymology of two part-names did not differ from the one-part name discussed above. Table 5 shows linguistic sources of given names in two-part Muslim names. As in the previous case, the main sources of given names were Arabic (77 %) and Persian (20 %). As in case with one-part names, females were more likely to have a given name of Persian origin than males, χ2 (2, N = 1,388) = 84.01, p < 0.001.

Linguistic sources of two-part Muslim names.

| Origin | Gender | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Given name | Arabic | 599 | 476 | 1,075 |

| Persian | 83 | 192 | 275 | |

| Other | 3 | 35 | 38 | |

| Total | 685 | 703 | 1,388 | |

| Second name | Arabic | 623 | 256 | 879 |

| Persian | 17 | 172 | 189 | |

| Other (Turkish) | 45 | 275 | 320 | |

| Total | 685 | 703 | 1,388 | |

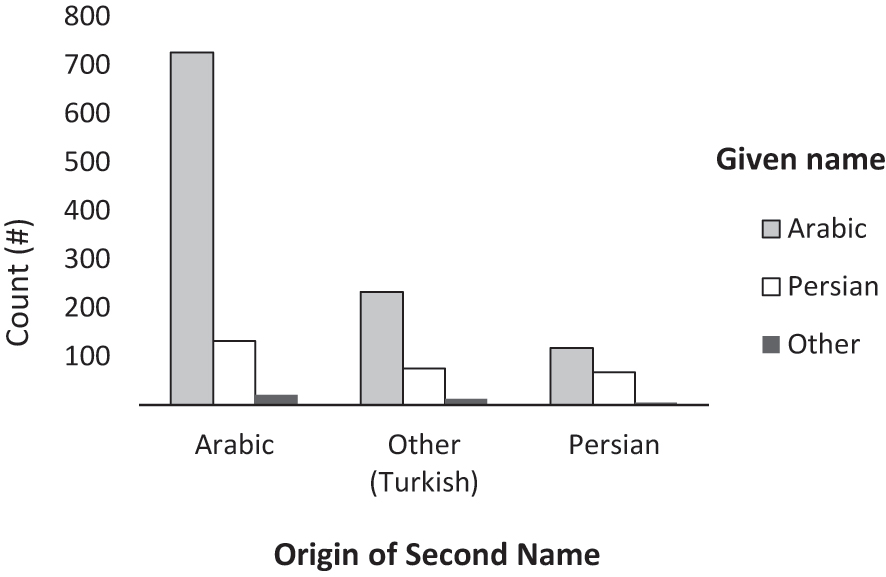

The origin of the given names largely determines possible combinations of the given and second name, χ2 (4, N = 1,388) = 54.89, p < 0.001, as shown in Figure 2. Given names of Persian origin are likely to be used when the second name is also Persian (e.g. Shabana Parveen), and the given name of Arabic origin is more likely to be used with the Arabic second part (e.g. Mohd Faisal or Jameel Ahmed). Second names of Turkish origin (e.g. Khan or Begum) show weaker preference for the origin of the given name. In addition, male names show stronger preference for combinations where both parts have Arabic origin, χ2 (4, N = 1,388) = 47.15, p < 0.001. In the next sub-section, we discuss different syntactic patterns within the two-part names.

Combinations of given and second names by their origin.

4.2.1 Blessed male names: Mohammad, Ahmad, Ali, Husain, and Hasan

A major pattern was the given name preceded or followed by either of the names of the Prophet: Mohammad or Ahmad, for example, Mohammad Sayeed and Jameel Ahmad. Schimmel (1990) explains the cultural significance of the use of these elements in Muslims names, “… if the names of earlier prophets are surrounded by an aura of blessing and protective power, how much more is the name of the final prophet bound to bring blessing to those who hear it” (p. 29). To this can be added the respect the bearer of the name shows by adding Prophet’s name to his own given name.

A significant percentage (345 or 51 %) of the two-part male names were composed of the given name and the honorific Mohammed, typically preceding the given name. The word Mohammad was used in its full form including spelling variants Muhammed, Mohammed and Muhammad or was abbreviated as Md., Mohd., and M. The fact that the first name is abbreviated shows that it is not what D’Souza (1955, 33) called “substantive or prepotent” part of the official name. This explains why Mohammad Jalaluddin with whom we opened the introduction felt disrespected when people addressed him as Mohammad, his official first name but not his given name Jalaluddin, which was his second name. The other name of the Prophet, Ahmad, also spelled as Ahmed, which appeared either before or after the given name as in Jameel Ahmad and Ahmad Imran in the corpus, formed 16 % of the two-part names. The given names in these cases are Jameel and Imran, which are used to address the person.

To the Prophet’s name can also be added three other names: Ali, his son in law and the fourth Caliph, and Hasan/Hassan and Husain/Hussain, his grand sons who are respected and revered, more by the Shiite Muslims than Sunnis. To underscore the significance of the name Ali and Husain, Schimmel (1990) quotes a tenth century writer who sent a letter to a descendant of Ali telling him to name their newborn boy Ali so that Allah may exalt, yu‘allī, his memory (p. 6). Rahman (2014) mentions that during the heightened sectarian conflict, some people carrying names such as Ali, Hasan, and Husain were targeted for attack because they were believed to be Shias. In 2006, in Iraq over 1,100 men changed their Sunni sounding names, e.g. Omar, Othman and Shia sounding names, e.g. Ali and Abbas to neutral ones such as Abdullah, fearing attacks from the rival militias (Wong 2006).

A feminine equivalent of the custom of adding a name to show respect or seek blessing is Fatima, prophet Mohammad’s daughter and Ali’s wife. Some female names consisted of a given name followed by Fatima, e.g. as Kaniz Fatima and Gulshan Fatima. Grammatically these names had the izāfat construction with the possessive marker joining the two names as in kanīz-i-fātimā, meaning ‘ Servant of Fatima’ and gulshan-i- fātimā, ‘Garden of Fatima’. Like the blessed male names discussed above, Fatima was also used as a source of blessing, especially among the Shia Muslims.

4.2.2 Patronym

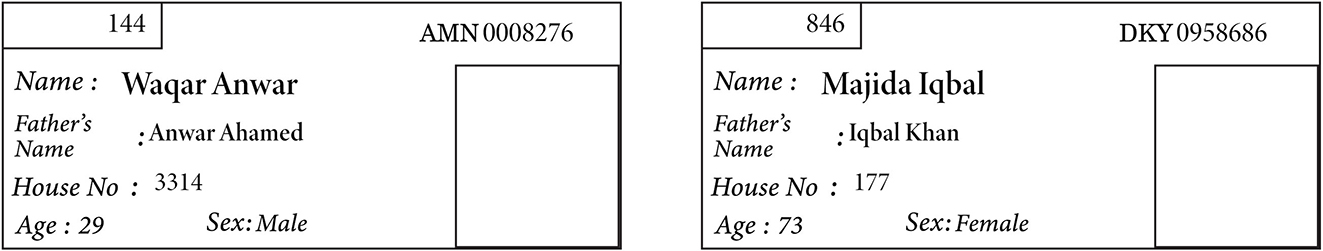

Some names in the corpus (115 or 8 %) consisted of given names followed by father’s name, e.g., Waqar Anwar and Sharjeel Amir. Figure 3 shows a male and a female given name with patronyms forming the second element of the names.

Personal names with patronyms.

The analysis revealed that adoption of father’s name is more frequent among the younger generation in women, which suggests that this is a new trend. While a chi-square test of independence revealed that younger women were more likely to have patronyms in their name than older women, χ2 (2, N = 948) = 16.51, p < 0.001, no association with age was found in men for the pattern that included father’s name (p = 0.335).

4.2.3 Honorific names: Begum, Sultana, Khanam, Khatoon

Some two-part female names in the corpus consisted of given names followed by honorific titles such as Begum/Begam, feminine of the Turkish Beg/Begg, Sultana, feminine of the Arabic word Sultan, ‘prince’, and Khanam, feminine of Turkish Khan. During the Mughal rule these titles were confined to ladies of rank, but later they began to be added after the given names of ordinary women (Schimmel 1990). The most frequent of these names was Begum (184 or 26 %). The title Begum, was conferred on Jahānāra, the daughter of the Mughal emperor Shahjahan (1592–1666), during his rule, which she retained even after Shahjahan was dethroned by his son Aurangzeb and continued to receive her aristocratic allowance (Ansari 2012a). In modern India and Pakistan, men use Begum also to refer to or address their wives regardless of their names. Other second names in the corpus, e.g. Sultana (15), Khatoon (14), and Khanum (11), also began their journey as aristocratic titles and developed into second names added to personal names as a means of showing social and class status. Rahman (2013a, 2013b) in his quantitative study of name-change in Pakistan found that Begum and Khatoon were confined to rural areas and women in cities such as Lahore do not use them. We discuss in Section 5 that these names are declining in their use in Delhi too.

4.2.4 Journey from Laqab to given name

The practice of giving laqab, nicknames is quite old and traces back to prophets of Islam. Nicknames serve the purpose of distinguishing the bearer of the name from others who have the same name (Schimmel 1990, 12). Examples of nicknames are Khalil Allah, ‘God’s friend’ given to Prophet Abraham and Saif Allah, ‘sword of God’ given to Khalid Bin Walid (592–642), the Muslim military commander who conquered Syria. The practice of giving nicknames was common among the Muslim Mughal kings and queens who themselves had nicknames and gave them to others. For example, the fourth Mughal emperor Jahangir’s (1569–1627) given name was Salim, named after the famous saint Shaikh Salim Chishti (1478–1572). He had two nicknames: Jahangir, also spelled Jehangir, ‘Conqueror of the world’ and Nuruddin, from Nūr Al-dīn ‘light of Religion/Islam’ (Ansari 2012b). His wife Mehrunnisa, who was given the title/nickname of Nur-i-Jahan, ‘light of the world’ was married to Ali Quli Beg, a military general, who was given the official nickname/title of Sher-i-Afghan, ‘lion of the Afghan’ for his bravery (Davies 2012). The given name of the latter Mughal emperor Shah Alam II (1729–1806) was Abdallah, and he was conferred the royal title Shāh-i-‘Ālam ‘King of the world’ in 1754. As the possessive izāfat marker -i- is not only not written but also not always pronounced especially in names in Urdu and Persian, he became famous by his title Shah Alam (Ali 2012).

Many names, inspired by the meaning and grammar of the nicknames like Shah Alam, were found in the corpus, for example Mahtab Alam, ‘moon of the world’, Khursheed Alam, ‘sun of the world’. These names were always written as two independent words. Since many Urdu speakers do not always know the Persian grammar, they may add Alam to words that may not sound very meaningful, for example Javed Alam ‘eternal of the world’.

The feminine counterpart of this pattern is a given name followed by the word jahan ‘world’ joined by the izāfat marker. Examples of such two-part names are Noor Jahan, Rashke Jahan, Gulshan Jahan, and Kosar Jahan. As discussed above, words containing the word Jahan meaning ‘world’ as in Nur Jahan, ‘light of the world’, was the royal title of the emperor Jahangir’s wife, given to add glory and grandeur to the queen. With time, the title developed into given name. As we discuss below in Section 5, the word Jahan is disappearing from female names.

4.2.5 Husband’s name

Taking husband’s name after marriage is an old practice in many cultures, often associated with patriarchy. In modern Westerns societies, the number of women taking their husband’s last name is as high as 70 % in the USA and 90 % in the UK (Savage 2020). The practice is stronger in more religious families. While 75 % of those marrying in Catholic and 72 % marrying in Protestant churches took their husbands names, only 40 % of people marrying in civil ceremonies did the same (Abel and Kruger 2011). The same tradition is observed among Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists in India. Jayaraman (2005, 477) argues that women in these cultures keep their fathers’ names until they are married after which they take their husband’s family name. Gujarati women adopt their husband’s given and family/caste name (Mistry 1982, 175). In the Meithi tribe of the Northeast India, the third component of a female name is husband’s family name (Chelliah 2005).

It is of note that in the Arab society, which is both patriarchal and patrilinear, women do not take their husband’s first or last name after marriage. The Arabic naming convention is rooted in Islam, in which it is prohibited to attribute oneself through names to anyone other than their biological father (Shabbir 2020). This practice, however, is not always followed in other Muslim countries. A study of names in the city of Lahore in Pakistan, a predominantly Muslim country, showed that 14 % of women added their husband’s first name and 9 % their husband’s last name to their given names (Rahman 2014, 16).

Our findings are in line with the practice reported in Rahman (2014). Among 585 married women in our corpus, we found 57 (10 %) female names with husband’s name or surname included. This tendency, however, began to change among the younger generation as younger women included their husband’s name significantly less frequently than older women, χ2 (2, N = 585) = 6.01, p < 0.05.

4.2.6 Birādrī/caste names: Syed, Khan, Begg, Ansari, Quraishi, Malik

Although Islam is in principle a casteless religion, Muslim societies in Old Delhi are socially organized in terms of occupational castes (Goodfriend 1983; Qasmi 1999). Qasmi discusses various social strata of castes among Muslims in Old Delhi, known as shurafā ‘the nobles’, the educated middle-class Muslims belonging to upper castes, and the pēshēwar ‘occupational groups’, belonging to lower castes. The shorafā consists of the castes known as Saiyyad/Syed, Shaikh, Mughal, and Pathan, who trace their lineage outside of India. The Syeds trace their lineage to Prophet Muhammad himself, and the Siddiqis and Farooquis – to the Caliphs Abu Bakr Al-Siddiq and Umar Al-Faruq (Schimmel 1990). Now the shurafā constitute a small portion of the Old Delhi population because a large number of them (70 % of the 500,000 Muslim population) left Delhi and migrated to Pakistan among eight million Muslims following the partition of India in 1947 (Mondal 2000; Pandey 2001). The occupational castes include the qasāi ‘butchers’, mōchī ‘shoemakers’, nāī ‘barbers’, rā’īn ‘fruit merchants’ etc.

The names of the upper castes, though small in number, in the corpus often carried their caste titles such as Syed, Shaikh, Beg/Begg (for Mughals), and Khan. Some of the major titles of the occupational castes found in the corpus are Ansari, Qureshi, Malik, Baqai, etc.[4] The title Syed always appeared in front of the given name, whereas other titles e.g., Khan, Ansari, etc. were added after the given name, for example Syed Aijaz, Aslam Khan, Saleem Quraishi, Parvez Ansari, and Roshan Malik.

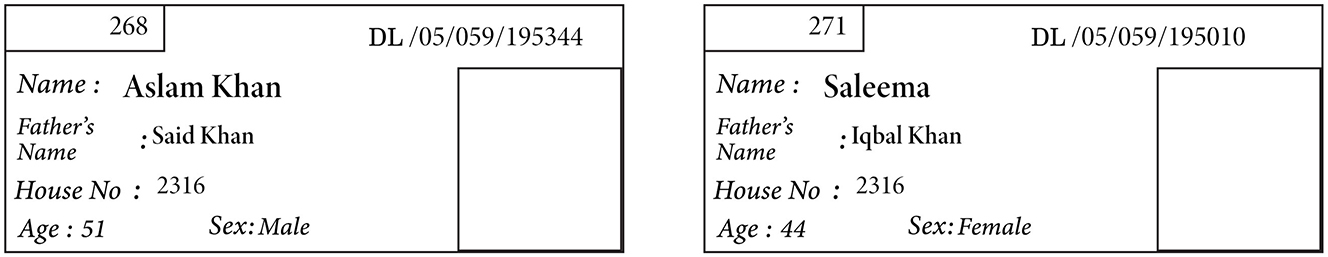

In the corpus, caste names were used by 15 % of the voters whose name included more than one part. They were significantly more frequent with male names (159 or 19 %) than with female names (90 or 12 %), χ2 (1, N = 1,388) = 16.98, p < 0.001. The voter cards in Figure 4 show two children of Mr. Said Khan, Saleema and Aslam Khan who live in the same joint family house number 2,316 with the son carrying the caste title Khan, but the daughter isn’t.

Caste title Khan among males and females.

In conclusion, the structure of two part-names, in terms of their composition, were quite diverse. Firstly, the most frequent of the two-part names, 71 % of the total, were composed of given names preceded or followed by a religious honorific such as Ahmad, Mohammad, Ali, Hasan, Husain, and Fatima, for female names. The remaining names were composed of given names followed by a patronym, caste name, husband’s name, and social honorific names such as Begum.

4.3 Three-part and four-part names

Three-part names were not as frequent as one and two-part names constituting only 191 (10 % of the corpus); four-part names were even less frequent numbering only 13 (0.7 %) in the entire corpus. The core structure of three and four part-names is based on two-part names with some other names added. For example, Jamal Hussain Ansari consists of a given name Jamal followed by Ahmad, a religious honorific, which is the most frequent structure of a two-part name discussed above, followed by the caste title Ansari. Some three-part female names were composed of the given name followed by patronym and caste name as in Soofia Jamal Ansari, a daughter of Jamal Ahmad Ansari. This pattern was also found in women’s taking their husband’s given and caste title. For example, Fatima Ali Khan took Ali Khan from her husband’s name Babar Ali Khan. Another pattern was the caste name Syed added to a what is a two-part name. For example, Syed Mohammad Muslim, in which Muslim is the given name preceded by a religious honorific Mohammad to which the caste title Syed has been added. A number of three-part names were composed of given name preceded by Mirza and followed by Begg/Beg. Mirza, originally amīr-zādah in Persian, ‘born of a prince, amir’ is a social honorific used during the Mughal rule to refer to people of rank (Levy and Burton-Page 2012). In the corpus this title always appears with the caste title Beg/Begg.

Four-part names were also an extension of two-part names with additional elements added. A marked feature of the four-part names was the addition of titles that indicate a Muslim sect. More than half of these names (n = 7) had Syed as the first element and a sect-indicating title as its component. For example, in the name Syed Manzoor Ahmad Naqvi, the given name is Manzoor preceded by the caste title Syed and followed by the religious honorific Ahmad with Naqvi indicating his Shia identity. While two caste titles namely Syed and Mirza occur before given names, others such as Ansari, Khan, Quraishi, and Malik appear after the given names. It is worth noting that four-part names did not contain any female names. The template of Muslim names can be seen in Figure 5.

Template of a Muslim name.

5 Shift in naming practices

Since personal names reflect and construct people’s ideologies and their social identities, they become popular or fall out of use as ideologies and perceptions of identities undergo transformation. As discussed above, Begum, Jahan, Perveen, and Bano were royal titles given to ladies of the Mughal ruling class and therefore they carried significant social prestige and power. These royal titles gradually began to be used by ordinary Muslim women as a means of gaining social prestige and respect. With the decline of the Muslim Mughal rule and the end of the colonial era and the advent democracy after the independence of India in 1947, these names no longer carried prestige they once did. Our data show that while older female names carried these titles, the younger generation did not.

Two elements of male names also witnessed a decline. Names with Abdul followed by one of the names of God, have a religious significance. There is a popular saying that best names are those that have (i) ḥamd ‘praise’, referring to names such as Ahmad and Mohammad, which derive from the Arabic root ḥamd and (ii) ‘abd ‘slave’ (of God) as in Abdul Rahman. Names containing Abd clearly have a religious significance because of its association with the Creator. This probably is the reason for its decline among the younger generation. The same holds true of names containing ‘-uddin, ‘of Islam’ as in Fakhruddin ‘pride of Islam’.

Table 6 shows the declining use of these names. To understand the factors that contribute to the decline of these names, we conducted a survey on people’s perceptions and ideologies about Begum: one of the names facing decline. In the next section we present the findings of the survey.

Names containing “Begum”, “Bano”, “Jahan”, “Parveeen”, “-uddin”, and “Abdul” across age groups.

| Age group | Total | Correlation with age (Pearson R) | Sig. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19–35 | 36–55 | 56–90 | ||||

| Begum | 23 | 101 | 61 | 185 | 0.226 | *** |

| Bano | 9 | 15 | 13 | 37 | 0.044 | n/s |

| Jahan | 5 | 20 | 20 | 47 | 0.137 | *** |

| Parveen | 18 | 32 | 7 | 57 | −0.076 | ** |

| -uddin | 8 | 37 | 32 | 77 | 0.123 | *** |

| Abdul | 10 | 11 | 16 | 37 | 0.050 | * |

-

Note: Significance codes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

5.1 Perceptions and attitudes toward Begum

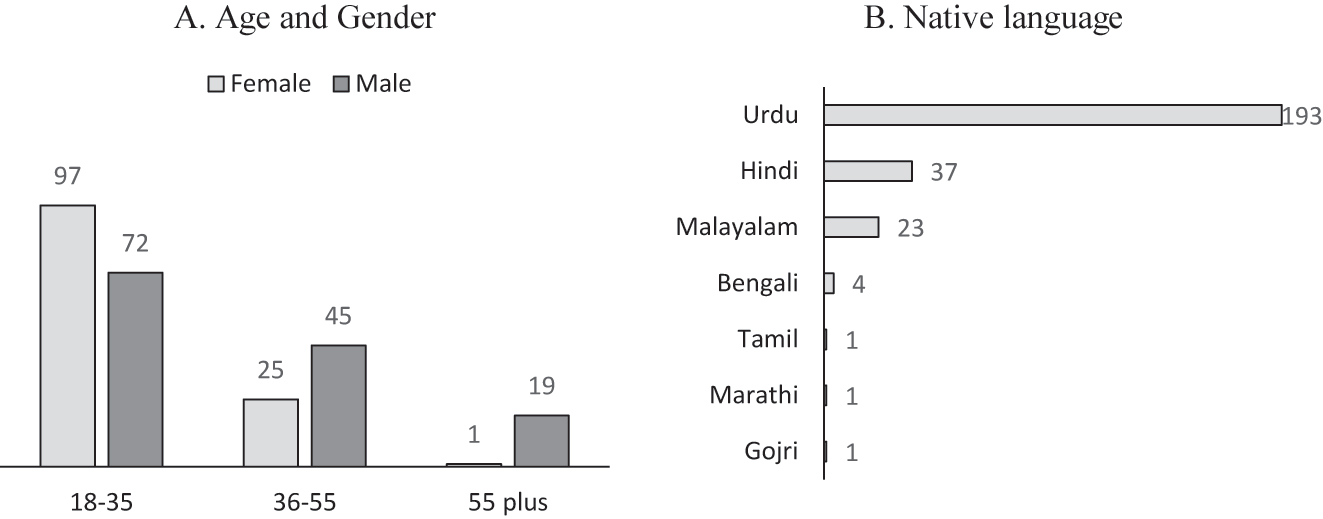

Since shifts in naming patterns is driven by people’s ideologies, an online survey was conducted to find out people’s ideologies toward the name Begum. A total of 260 people from the university town of Aligarh in the state of Uttar Pradesh in India participated in the survey. The reason for choosing Aligarh for the survey was that there is significant Muslim population in and around the Aligarh Muslim University campus. Participants were recruited through what is known in the literature as friend-of-a-friend method (Milroy and Gordon 2003). A link containing survey questions using Google Form was sent to some people known to the first and second author and they were requested to share the link with their friends. The method was successful in securing completed 260 responses.

The demographics of the participants are summarized in Figure 6. While 123 participants were female, 136 were male. In terms of their age, 169 of them were young people between 18 and 35 years of age and 70 participants belonged to the group of middle-aged people. Only 20 people were 55 years or older (Figure 6A). The linguistic backgrounds of the participants were diverse in that they spoke seven different mother tongues with a majority 74 % (n = 193) indicating Urdu as their mother tongue. Speakers of other languages were Hindi 14 % (n = 37), Malayalam 9 % (n = 23), Bengali 1.5 % (n = 4) (Figure 6B).

Demographics of the survey participants: age, gender, and native language.

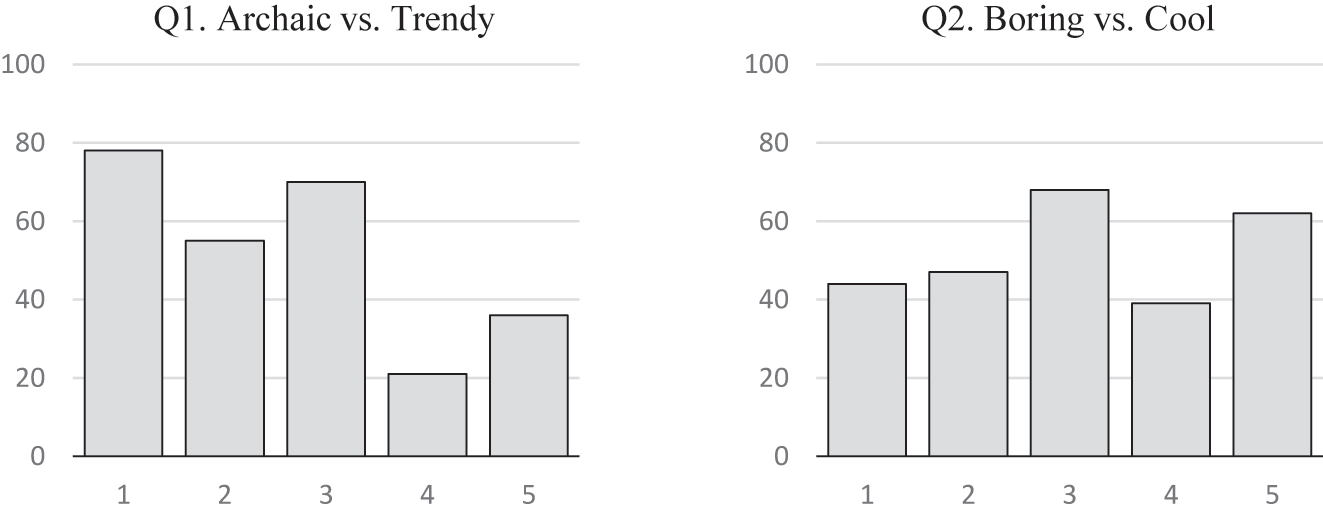

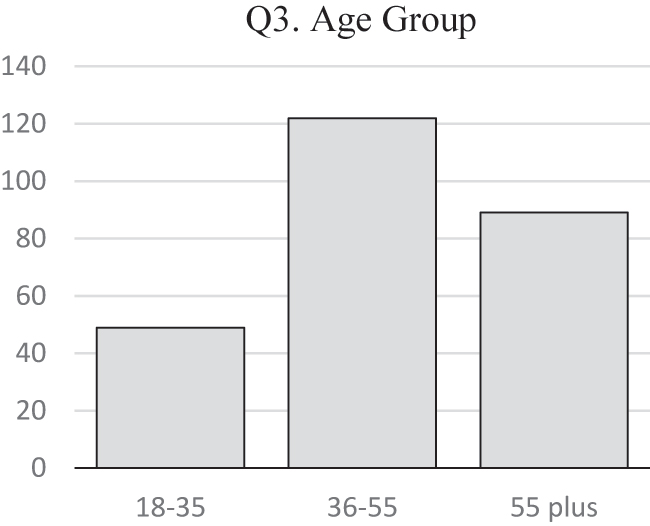

5.1.1 Results: attitudes toward Begum

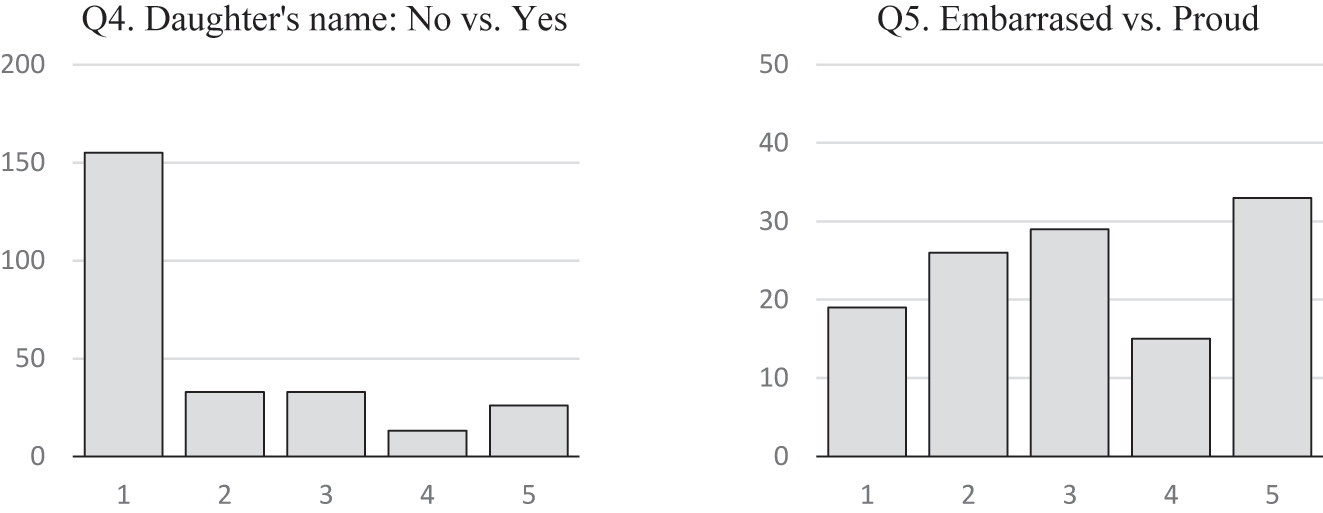

The first step of the analysis evaluated participants’ attitudes toward the name Begum. We tested attitudes in five conceptual areas, i.e., we asked participants whether the name 1) sounded archaic or trendy, 2) sounded boring or cool, 3) was associated with a particular age group, 4) whether they would add the name to their daughter’s name or not, and 5) we also asked for female participants if they would feel embarrassed or proud if called Begum. The responses to the four questions were collected using a 5-point Likert scale. For questions 1–2 and 4–5, the lowest score 1 corresponded to the negative attitude (e.g., “boring” or “archaic”), and the highest score 5 corresponded to the positive attitude (e.g., “cool” or “trendy”). The responses to Question 3 “What age group would you associate the person called Begum with?” were collected using a 3-point scale, on which score 1 referred to young age of 18–35, score 2 referred to middle age of 36–55, and score 3 – to the age of 55 and older. The response patterns to these questions are shown in Figures 7–9.

Responses to Question 1 “In your view, the word Begum in a female name sounds archaic or trendy?” and Question 2 “Would you say the name Begum sounds boring or cool?”

Responses to Question 3: “If someone’s name had the word Begum, what age group would you associate the person with?”

Responses to Question 4 “Hypothetically, how likely are to you add this word in your daughter’s name?” and Question 5 “For females only: If Begum was part of your name, how would you feel?”

The attitudes toward the name Begum revealed a complex pattern. There were more responses that described it as “archaic” (51 %) than “trendy” (22 %) or associated it with old age (34 %) rather than young age (18 %). Participants showed a very strong negative attitude against giving their daughter this name (72 %), while only 15 % of responses showed that they would use Begum in the names of their own daughters. However, as Figure 8 shows, a relatively equal number of participants felt that the name Begum sounded “cool” (39 %) and “boring” (35 %). And females indicated that they would feel “proud” to have the name Begum as often (39 %) as “embarrassed” (37 %).

Despite the relatively contradictory attitudes shown in Figures 7 and 9, participants showed good consistency in their responses, as shown in Table 7. Answers to questions 1–2 and 4–5 strongly correlated with each other (Pearson R between 0.528 and 0.661, p < 0.001). Participants tended to have positive or negative attitudes about the name in several categories. The responses to Question 3 about the age showed significant negative correlation with the responses to the other questions (Pearson R between −0.314 and −0.441, p < 0.001) indicating that participants who associated a person called Begum with younger age tended to have more positive attitudes toward the name, and those who associated the name with older age revealed more negative attitudes toward it.

Significant Pearson correlations (Pearson R) between attitudes toward Begum in Questions 1–5.

| Question | Attitude | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic versus trendy | Boring versus cool | Young versus old | Daughter’s name: no versus yes | Embarrassed versus proud | |

| 1. Archaic versus trendy | 0.637*** | −0.441*** | 0.601*** | 0.528*** | |

| 2. Boring versus cool | 0.637*** | −0.314*** | 0.472*** | 0.585*** | |

| 3. Age group: young versus old | −0.441*** | −0.314*** | −0.389*** | −0.322*** | |

| 4. Daughter’s name: no versus yes | 0.601*** | 0.472*** | −0.389*** | 0.661*** | |

| 5. Embarrassed versus proud | 0.528*** | 0.585*** | −0.322*** | 0.661*** | |

-

Note: Significance codes: ***p < 0.001.

The responses showed association with some of participants’ demographics. A series of chi-square tests of independence revealed that native language affected response to Question 4, χ2 (24, N = 260) = 40.35, p < 0.05, and Question 5, χ2 (20, N = 122) = 37.01, p < 0.05. Speakers of Malayalam had less negative attitude (49 %) toward giving their daughter the name Begum. They also indicated that they would feel “proud” more frequently (58 %) than speakers of other languages. This is understandable as Begum is much more common among Urdu-speaking Muslims than Malayalam speakers and may not carry the negative ideologies that Urdu speakers have towards it. Gender was significantly associated with the response to Question 2, χ2 (8, N = 260) = 16.51, p < 0.05. Females were more likely to perceive the name as “boring” (41 %) than males (29 %). No association was found between the response patterns and age (p > 0.1).

5.1.2 Results: attributes

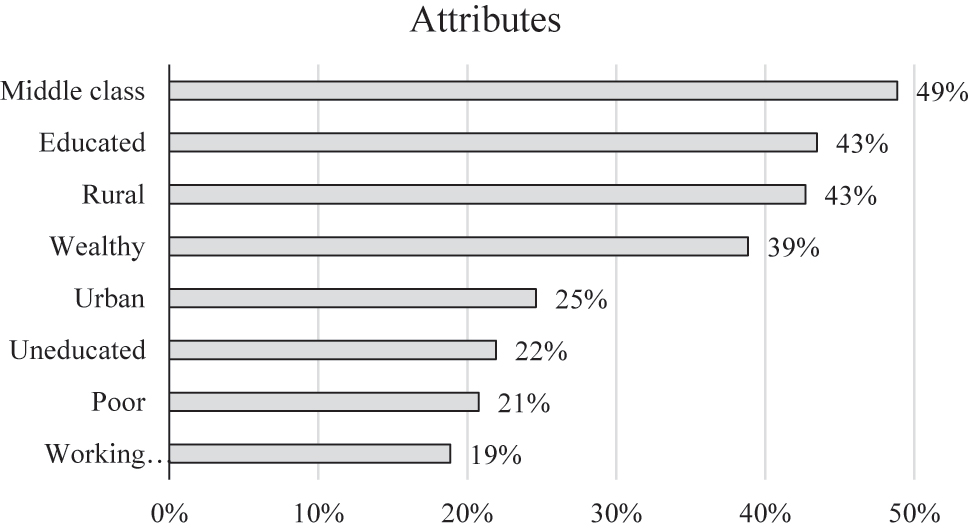

Next, we evaluated the responses to Question 6, in which the participants had to indicate their association of the name Begum with eight attributes: Uneducated, Poor, Rural, Working class, Educated, Wealthy, Urban, Middle class. They were free to mention as many properties as possible. The results are summarized in Figure 10.

Responses to Question 6 “Which of the following features would you associate with the person carrying the word Begum in her name”

5.1.3 Correlation between attitudes and attributes

The perceived attributes revealed strong correlation with the responses to five questions that tested the attitudes toward the name Begum (Table 8). The choice of the attribute Middle class, which was most frequently by participants, correlated with the attitudes “boring”, “not a daughter’s name”, and “embarrassed”. Two attributes – Educated and Rural – revealed the strongest correlations with all five attitudes. Participants who associated this name with Education, had a more positive attitude toward it perceiving it as more “trendy”, “cool”, associated it with younger age, were more willing to give this name to their daughter and more ‘proud to be called with this name’. Participants who associated the name with the attribute Rural, had a more negative attitude. They perceived it as more “archaic”, more “boring”, associated more with older age, were less willing to give the name to their daughter and felt more embarrassed if called Begum.

Significant Pearson correlations (Pearson R) between attitudes toward Begum and perceived attributes characterizing the name.

| Attribute | Attitude | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic versus trendy | Boring versus cool | Age group: young versus old | Daughter’s name: no versus yes | Embarrassed versus proud | |

| Middle class | −0.130* | −0.167** | −0.237** | ||

| Educated | 0.413*** | 0.271*** | −0.244*** | 0.356*** | 0.386*** |

| Rural | −0.302*** | −0.273*** | 0.207*** | −0.256*** | −0.345*** |

| Wealthy | |||||

| Urban | 0.152* | ||||

| Uneducated | −0.145* | −0.161** | −0.177* | ||

| Poor | −0.164** | −0.155* | 0.196** | −0.179* | |

| Working class | |||||

-

Note: Significance codes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The attribute Poor correlated with the negative attitudes “archaic”, “boring”, “old age” and “embarrassed”; the attribute Uneducated correlated with the attitudes “archaic”, “boring”, “embarrassed”. The attribute Urban revealed positive correlation only with the attitude “trendy”. The attributes Wealthy and Working class did not correlate with any attitude.

In conclusion, we found a complex pattern of attitudes in the perception of Begum. The results showed a split in participants’ attitudes. Three most frequent attributes associated with the name, – Middle class, Rural, and Educated, – were perceived differently. While the attribute Educated was, quite expectedly, correlated with positive attitudes toward the name (e.g., “trendy”, “cool”, “proud”), the attributes Middle class and Rural correlated with negative attitudes (e.g., “archaic”, “boring”, “not a daughter’s name”). Whereas more negative attitude toward rural values is not uncommon in modern societies, negative attitude toward middle class is somewhat surprising. Most likely, negative attitudes toward middle class reflects different perception of social class distinction in India compared to Western societies. Middle class, in the eyes of our participants, was more closely associated with rural life rather than with urban life and education (e.g. Rickford 1986).

6 Conclusion

In this paper, based on an analysis of a corpus of two-thousand Muslim names in Urdu from Delhi, we have made three key points. We have shown that unlike Muslim names in the Arab World, which are quadripartite in which the given name occurs first followed by father’s, then grandfather’s name with the family name appearing as the fourth part, Muslim names in North India show a complex and diverse pattern. We further show that the structure of names of north Indian Muslims is different from their fellow Muslims in Kerala. We presented a typology of Muslim names showing four major morpho-syntactic patterns. Official Muslim names were composed of one, two, three, or four parts. In contrast with western or Arabic names, in our corpus, 18 % of the names were composed of only given names, without a last name or father’s name. An analysis of the etymological origin of given names showed that 96 % of the given names belonged to Arabic (72 %) and Persian (24 %), languages associated with Islam. Consequently, the ethnic identity of Muslims in India is encoded in their given names. Arabic is not only the language of Islamic scriptures but also a source of names of religious and historical personalities admired and held as models for Muslims across the world. Persian is not only the language of administration during Muslim rules of the Mughals and the Afghans but also the language of high culture (Alam 1998). The cultural prestige of Persian continued even after the decline of the Mughal empire in 1858. Bards of Urdu poetry such as Mirza Ghalib (1797–1869) and Muhammad Iqbal (1977–1938) composed their early work in Persian.

The most frequent pattern was two-part names, which accounted for 71 % of all names. The two-part names displayed a complex pattern in that in addition to the given name, they consisted of additional names carrying religious honorifics, caste titles, patronym, and husband’s name. One of our key findings is that unlike Arabic names, in our data 71 % of two-part male names consisted of the given name preceded or followed by Mohammad or Ahmad – two of the common names of the Prophet. These names were added as a token of respect and a source of blessing and are not used to address the people bearing the names even if they appear as the first part of their official name. The names Ali, Hasan, and Husain, members of Prophet Mohammad’s immediate family, were also added to given names as honorifics. We further showed that some two-part names consisted of the given name followed by father’ name, or caste name, or husband’s name. The three and four-part names were structurally built on two-part names with some addition names signifying castes and sects.

In the final section we discussed the decline of some names across generations in general with a focus on the decline of Begum, a social honorific title occurring as a second element of Muslim female names. Based on a survey we showed that people’s ideologies and perceptions of Begum has undergone a shift following the decline of the Mughal rule and advent of democracy in India. We have shown that Begum, a tile used by the ladies of rank during the Mughal rule, is no longer sees as a marker of prestige and often seen as archaic and boring by Urdu speakers. By contrast, Malayalam speakers from the South still hold the name as prestigious.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Aysha Al-Sulaiti, Samia Musa, Samiha Tarannum, and Sara Al-Theyab for their help in gathering the data. We also thank the Department of English Language and Literature, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman, where the first draft of the paper was written, for hosting the first author as visiting faculty. Thanks are due to Dr. Abdul Gabbar Al-Sharafi of Sultan Qaboos University for serving as a mentor of the first author during this period.

References

Abd-el-Jawad, Hassan. 1986. A linguistic and sociocultural study of personal names in Jordan. Anthropological Linguistics 28(1). 80–94.Search in Google Scholar

Abel, Ernest L. & Michael L. Kruger. 2011. Taking thy husband’s name: The role of religious affiliation. Names 59(1). 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1179/002777310X12759861710628.Search in Google Scholar

Ahmad, Rizwan. 2020a. Hate, bigotry, and discrimination against Muslims in India: Urdu during the Hindutva rule. In Rita Verma & Michael Apple (eds.), Disrupting hate in education: Teacher activists, democracy, and global pedagogies of interruption, 129–152. New York, USA: Routledge.10.4324/9780429325878-10Search in Google Scholar

Ahmad, Rizwan. 2020b. ‘I regret having named him Sahil’: Urdu names in India. Language on the Move (blog). Available at: https://www.languageonthemove.com/i-regret-having-named-him-sahil-urdu-names-in-india/.Search in Google Scholar

Alam, Muzaffar. 1998. The pursuit of Persian: Language in Mughal politics. Modern Asian Studies 32(2). 317–349. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0026749x98002947.Search in Google Scholar

Ali, Mohammad Athar. 2012. Shah Alam II. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. IX, 192b. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. Available at: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com:443/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/shah-alam-ii-SIM_6745.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Sijistani, Abu Dawud. n.d. Sunan Abi Dawud 4950 – General behavior (Kitab Al-Adab) – كتاب الأدب – Sunnah.Com – Sayings and teachings of prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم). https://sunnah.com/abudawud:4950 (accessed 28 November 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Ansari, Abd Al-Samad Bazmee. 2012a. BEGUM. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd edn., vol. I, 1161a. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. Available at: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com:443/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/begum-SIM_1357.Search in Google Scholar

Ansari, Abd Al-Samad Bazmee. 2012b. DJahangir. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. II, 379b. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. Available at: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com:443/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/djahangir-SIM_1929.Search in Google Scholar

Bertrand, Marianne & Sendhil Mullainathan. 2004. Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review 94(4). 991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828042002561.Search in Google Scholar

Bosch, Barbara. 2000. Ethnicity markers in Afrikaans. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 144. 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2000.144.51.Search in Google Scholar

Chelliah, Shobhana L. 2005. Asserting nationhood through personal name choice: The case of the Meithei of Northeast India. Anthropological Linguistics 47. 169–216.Search in Google Scholar

Colebrooke, Thomas Edward. 1881. Art. IX.—On the proper names of the Mohammedans. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 13(2). 237–280. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0035869x00017810.Search in Google Scholar

Davies, Cuthbert Collin. 2012. Nur Djahan. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. VIII, 124b. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. Available at: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com:443/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/nur-djahan-SIM_5983.Search in Google Scholar

D’Souza, Victor S. 1955. Sociological significance of systems of names: With special reference to Kerala. Sociological Bulletin 4(1). 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022919550103.Search in Google Scholar

Emeneau, Murray Barnson. 1938. Personal names of the Todas. American Anthropologist 40(2). 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1938.40.2.02a00030.Search in Google Scholar

Emeneau, Murray Barnson. 1976. Personal names of the Coorgs. Journal of the American Oriental Society 96(1). 7–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/599885.Search in Google Scholar

Goodfriend, Douglas E. 1983. Changing concepts of caste and status among Old Delhi Muslims. In Imtiaz Ahmad (ed.), Modernization and social change among Muslims in India, vol. 1, 119–152. Delhi, India: Manohar Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Jayaraman, Raja. 2005. Personal identity in a globalized world: Cultural roots of Hindu personal names and surnames. The Journal of Popular Culture 38(3). 476–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.2005.00124.x.Search in Google Scholar

Junghare, Indira Y. 1975. Socio-psychological aspects and linguistic analysis of Marathi names. Names 23(1). 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1179/nam.1975.23.1.31.Search in Google Scholar

Klerk, Vivian de & Irene Lagonikos. 2004. First-name changes in South Africa: The swing of the Pendulum. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 170. 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2004.2004.170.59.Search in Google Scholar

Koul, Omkar Nath. 1995. Koul personal names in Kashmiri – Google search. Kashmiri Pandit Network. Available at: http://ikashmir.net/onkoul/pdf/PersonalNames.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Levy, John Burton-Page. 2012. Mirza. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd edn., vol. VII, 129a. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. Available at: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com:443/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/mirza-COM_0751.Search in Google Scholar

Mackenzie, Laurel. 2018. What’s in a name? Teaching linguistics using onomastic data. Language 94(4). e293–e310. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2018.0068.Search in Google Scholar

Markey, Thomas L. 1982. Crisis and cognition in onomastics. Names 30(3). 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1179/nam.1982.30.3.129.Search in Google Scholar

Mehrotra, Raja Ram. 1982. Impact of religion on Hindi personal names. Names: A Journal of Onomastics 30(1). 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1179/nam.1982.30.1.43.Search in Google Scholar

Mesthrie, Rajend. 2021. Sociolinguistic patterns and names: A variationist study of changes in personal names among Indian South Africans. Language in Society 50(1). 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404520000652.Search in Google Scholar

Milroy, Lesley & Matthew J. Gordon. 2003. Sociolinguistics: Method and interpretation. In Language in society, vol. 34. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.10.1002/9780470758359Search in Google Scholar

Mistry, P. J. 1982. PERSONAL NAMES: Their structure, variation, and grammar in Gujarati. South Asian Review 6(3). 174–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/02759527.1982.11933101.Search in Google Scholar

Mondal, Seik Rahim. 2000. Muslim population in India: Some demographic and socio-economic features. International Journal of Anthropology 15(1). 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02442051.Search in Google Scholar

Notzon, Beth & Gayle Nesom. 2005. The Arabic naming system. Science 28(1). 20–21.Search in Google Scholar

Pandey, Gyanendra. 2001. Remembering partition: Violence, nationalism and history in India. Contemporary South Asia 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511613173Search in Google Scholar

Parada, Maryann. 2016. Ethnolinguistic and gender aspects of Latino naming in Chicago: Exploring regional variation. Names 64(1). 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00277738.2016.1118858.Search in Google Scholar

Qasmi, Akhlaq Husayn Maulana. 1999. Dillī Kī Berādriyān (Communities of Delhi). Delhi: Maktabā Alyawm.Search in Google Scholar

Rahman, Tariq. 2013a. Personal names and the Islamic identity in Pakistan. Islamic Studies 52. 239–296.Search in Google Scholar

Rahman, Tariq. 2013b. Personal names of Pakistani Muslims: An essay on onomastics. Pakistan Perspective 18(1). 33–57.Search in Google Scholar

Rahman, Tariq. 2014. Names as traps: Onomastic destigmatization strategies in Pakistan. Pakistan Perspectives 19(1). 9–25.Search in Google Scholar

Rickford, John R. 1986. The need for new approaches to social class analysis in sociolinguistics. Language and Communication 6(3). 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/0271-5309(86)90024-8.Search in Google Scholar

Savage, Maddy. 2020. Why do women still change their names? BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200921-why-do-women-still-change-their-names.Search in Google Scholar

Schimmel, Anne-Marie. 1990. Islamic names: An introduction. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9781474472333Search in Google Scholar

Shabbir, Yusuf. 2020. Can wife change surname after marriage. Islamic Portal. Available at: https://islamicportal.co.uk/can-wife-change-surname-after-marriage/.Search in Google Scholar

Shah, Nasra M. 2013. Labour migration from Asian to GCC countries: Trends, patterns and policies. Middle East Law and Governance 5(1–2). 36–70. https://doi.org/10.1163/18763375-00501002.Search in Google Scholar

Shrestha, Uma. 2000. Changing patterns of personal names among the Maharjans of Katmandu. Names 48(1). 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1179/nam.2000.48.1.27.Search in Google Scholar

Sinclair, W. F. 1889. Art. II.—Indian names for English tongues. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 21(1). 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0035869x00165724.Search in Google Scholar

Suzman, Susan M. 1994. Names as pointers: Zulu personal naming practices. Language in Society 23(2). 253–272. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404500017851.Search in Google Scholar

Thorat, Sukhadeo & Paul Attewell. 2007. The legacy of social exclusion: A correspondence study of job discrimination in India. Economic and Political Weekly 42(41). 4141–4145.Search in Google Scholar

Wong, Edward. 2006. To stay alive, Iraqis change their names, sec. World. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/06/world/middleeast/06identity.html.Search in Google Scholar

Wright, Theodore P. 2006. South-Asian Muslim naming for identity versus name-changing for concealing identity. Indian Journal of Secularism 10(1). 5–10.Search in Google Scholar

Yassin, Mahmoud Aziz F. 1978. Personal names of address in Kuwaiti Arabic. Anthropological Linguistics 20(2). 53–63.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- From (in)securitisation to conviviality: the reconciliatory potential of participatory ethnography

- “I know how to improve. You know what I mean?”. Neoliberalism and the development of multilingual identities through study abroad

- “That’s all it takes to be trans”: counter-strategies to hetero- and transnormative discourse on YouTube

- Sweden’s multilingual language policy through the lens of Turkish-heritage family language practices and beliefs

- Discursive valuing practices at the periphery: Javanese use on Indonesian youth radio in multilingual Solo

- A comparative analysis of two cases of language death and maintenance in post-Islam Egypt and Great Khorāsān: reasons and motives

- Muslim personal names in Urdu: structure, meaning, and change

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- From (in)securitisation to conviviality: the reconciliatory potential of participatory ethnography

- “I know how to improve. You know what I mean?”. Neoliberalism and the development of multilingual identities through study abroad

- “That’s all it takes to be trans”: counter-strategies to hetero- and transnormative discourse on YouTube

- Sweden’s multilingual language policy through the lens of Turkish-heritage family language practices and beliefs

- Discursive valuing practices at the periphery: Javanese use on Indonesian youth radio in multilingual Solo

- A comparative analysis of two cases of language death and maintenance in post-Islam Egypt and Great Khorāsān: reasons and motives

- Muslim personal names in Urdu: structure, meaning, and change