Enhanced mechanical strength and water resistance of bamboo/epoxy composites using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-treated fibers for structural applications

Abstract

This study investigates the influence of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) treatment on bamboo long fibers to improve their performance in epoxy composites. Bamboo fibers were treated with PVA solutions at 1 %, 3 %, and 5 % and incorporated into epoxy matrices fabricated by hand lay-up. Microscopy revealed that 3 % PVA formed a uniform coating on fiber surfaces, enhancing adhesion with the matrix. Mechanical testing showed that PVA treatment improved tensile strength (from 32 to 39 MPa) and modulus (from 0.9 to 1.8 GPa), while impact resistance slightly decreased due to restricted fiber pull-out. Water absorption was also reduced, with 3 % PVA composites exhibiting the lowest uptake. Overall, PVA treatment is demonstrated as an effective and environmentally friendly modification method that enhances the mechanical strength and durability of bamboo/epoxy composites, making them more suitable for structural applications.

1 Introduction

Natural fibers are increasingly used in composites due to their low cost, biodegradability, and good mechanical properties, making them a sustainable alternative to synthetic fibers. 1 , 2 Among these, bamboo stands out as an excellent material for composite applications because it offers superior strength performance per weight and dual sustainability, i.e., being both environmentally friendly and economically viable, while remaining biodegradable. 3 Research shows that bamboo fibers reinforced as an epoxy composite 4 reinforcement opens new opportunities for automotive components, along with construction and packaging applications. 5 The extensive investigation of bamboo fibers in natural fiber composites occurs because of their fast growth rate, combined with their accessibility and lower environmental footprint compared to classic synthetic materials. 6 The composition of bamboo fibers consists mostly of cellulose, alongside hemicellulose and lignin, to produce their rigid qualities and tensile strength. 7 Bamboo fibers are rich in cellulose, which imparts significant strength and stiffness, and this versatile biopolymer has also found use in a wide range of other applications. 8

The usage of bamboo fibers brings several beneficial traits, yet presents a drawback that results from hydrophilic absorption properties. Its hydrophilic nature allows bamboo to absorb water since it is hydrogen-bonding-friendly. 9 The physical nature of this material undergoes substantial alterations when moisture is absorbed. The bamboo fibers display undesirable characteristics when used without modification in their extracted form due to their immersion in water, because they are hydrophilic. 10 The unmodified bamboo fiber maintains poor bonding with the material surfaces when added directly without treatment. The presence of dust and impurities, along with unfavorable functional species on the fiber’s surface, causes hindrance to bond formation between materials. 11 The undesirable nature of natural fibers would simultaneously reduce both physical properties and hydrophobic capabilities. The mechanical properties decrease alongside adverse effects on the dimensional stability of the materials. These negative outcomes become manageable when correct surface modification techniques are applied. The surface properties of fibers become more suitable through chemical surface modifications. The application of surface treatments to fibers creates a powerful bond and leads to simultaneous amorphous compound extraction from their surfaces. 12 Surface treatment generates both adhesive interfacial bonds and eliminates the impurities and amorphous substances, leading to enhanced performance. It improves the mechanical and thermal properties of both the fibers and the composite. 13

Numerous chemical approaches have led to better mechanical properties for composite materials. Three principal methods for composite preparation consist of hand lay-up and surface selective dissolution method, as well as the vacuum infusion process for composite preparation. 14 The selected manufacturing methods have unique features that match different application needs. When applying short fiber composites, the selective dissolution method develops superior mechanical properties, which lead to enhanced strength and modulus measurements. 15 Fibre treatment serves mainly to free both sides from impurities. The surface treatment is used both for removing existing surface impurities and modifying the actual surface topography. 16 , 17 The surface treatment method provides two major benefits: it removes lignin and hemicellulose from fibers, and it improves their interaction with matrices. 18 Belonging to the most widely used chemical treatments are alkali, isocyanates, silane, acetylation, and benzoylation. 19 , 20 Most of these chemicals used to enhance natural fiber-reinforced polymer-based composites demonstrate environmental risks despite their ability to boost mechanical performance. 21 Industrial asthma cases mostly result from exposure to isocyanates, which make up the most frequent chemical cause of work-related sensitization. The highly reactive gas known as silane belongs to the fire hazard classification standards.

The chemical processes acetylation and benzoylation present dangerous effects on human health, as well as cost-effective benefits. 22 Both acetylation and benzoylation harm human health, together with their cost-effective benefits. 23 Among chemical agents, alkali treatment using sodium hydroxide is the most common method of improving surface properties. NaOH serves as the alkali solution for most natural fiber modifications. 24 The contact area between the fiber and matrix surface improves because NaOH treatment removes sticky substances that adhere to the fiber surface. The study by Massaguni et al. 25 reported the enhancement in the mechanical strength of bamboo composite modified by NaOH treatment. Results revealed that 5 % of NaOH treatment demonstrated the highest tensile strength and modulus. Numerous studies have evaluated how bamboo fibers that underwent different sodium hydroxide treatments affected the final properties of bamboo fiber-reinforced composites. The effects from NaOH treatment of natural fibers emerge based on both the solution temperature during processing plus the duration of treatment, and the solution concentration level. Rothenhausler et al. 26 conducted research that examined the effects of silane, siloxane, and sodium hydroxide treatment on flax fiber composite properties. The tensile strength of the composite increased according to their studies. Buson et al. 27 studied how acetylation combined with alkalization improves the fiber wettability, resulting in better mechanical properties. Despite extensive research on chemical modifications such as alkali, silane, and acetylation, their application often raises concerns regarding toxicity, environmental impact, and processing cost. There remains a clear research gap in exploring safer and more sustainable fiber modification strategies that balance mechanical enhancement with durability. In this study, we propose PVA treatment as a novel, environmentally friendly alternative for bamboo fibers. Unlike conventional methods, PVA forms a uniform surface coating that improves interfacial bonding while reducing hydrophilicity. This work addresses the gap by systematically evaluating the influence of different PVA concentrations on tensile, impact, and water absorption behavior of bamboo/epoxy composites, thereby establishing an innovative and sustainable pathway for developing durable structural composites.

The research investigates PVA treatment effects on bamboo/epoxy composites, focusing on how various PVA concentration levels from 1 to 3 and 5 wt.% affect mechanical behavior and water absorption properties. The research will examine the impact of PVA treatment on bamboo/epoxy composite material properties through evaluations of tensile strength alongside modulus and impact resistance, and water absorption, and therefore determine optimal theoretical treatment methods. The current investigation joins existing knowledge about bamboo as a composite material reinforcement, while evaluating PVA treatment as an industrial-friendly method for enhancing bamboo/epoxy composite properties.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Bamboo stem material (Bambusa arundinacea – 8 years old) was purchased from a local market in Pakistan. Nobel Trading Company, Pakistan, supplied epoxy and curing agents. NaOH (purity 97 %) and PVA (purity 99 %) (Sigma Aldrich, USA) were purchased from the City Scientific Store in Islamabad, Pakistan.

2.2 Extraction, PVA treatment, and composite fabrication

The bamboo fibers were manually extracted from bamboo strips and used as unidirectional long fibers with an average length of ∼30 cm and a diameter ranging from 0.8 to 1.0 mm. This corresponds to an aspect ratio (L/d) of approximately 300–375. The fibers were employed as aligned, long, unidirectional reinforcements. The extraction of bamboo fibers occurred through chemical methods using bamboo strips as the starting material. The NaOH solution containing 3 wt.% was used for bamboo treatment at a temperature of 70 °C for 10 h. After that, bamboo fibers were extracted, followed by washing with distilled water and drying in an oven at 50 °C for 24 h. The PVA treatment times consisted of 1, 3, and 5 wt.% of PVA solutions that soaked the fibers for 2 h under room temperature conditions. The treated bamboo fibers received water washing before undergoing oven drying at 50 °C for 24 h.

The overhead stirrer combined epoxy resin with its hardener in a 1:2 mixing ratio. The mixture underwent degassing for 15 min to remove the air bubbles that were produced by stirring. The hand lay-up method was used to fabricate the set of composite specimens containing different fiber amounts (10, 20, 30 wt.%). Various casting molds were selected based on the exact width, thickness, and length requirements within ASTM standards. The standards used were ASTM D3039 for tensile specimens, ASTM D6110-10 for impact test, and ASTM D570-98 for specimens used in water absorption test. Grease was used as a lubricant to facilitate the removal of the composite from the mold. Matrix and fiber layers were added in alternating order to achieve a balanced dispersion of the two components. The composites were allowed to cure at room temperature inside the mold and then post-cured at ambient conditions for 24 h before testing. All mechanical and water absorption tests were performed in triplicate, and the reported values are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD).

2.3 Characterization

The average diameter analysis of fibers was performed through an optical microscope, Olympus BHM. Fiber diameter was measured at five points on each of 30 fibers, and the distribution was used to report average diameter values. The density measurements of the prepared composites followed Archimedes’ principle. The surface morphology of the fibers and fractured composites was examined using a Zeiss EVO 15 scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an SEI detector at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV and a working distance of 16 mm. To determine the mechanical characteristics of the composites, tensile and impact tests were conducted. The testing machine INSTRON 5567 performed tension tests according to ASTM D3039 standards. The SHIMADZU impact testing machine conducted Charpy impact tests at 1.5 kg f m capacity according to ASTM D6110-10 standard. ASTM D570-98 provides the standards for testing resistance to water absorption through water absorption tests. The change in weight between pre-immersion and post-immersion measurements showed the water absorption capacity of the composite material.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Microscopic analysis of the fibers

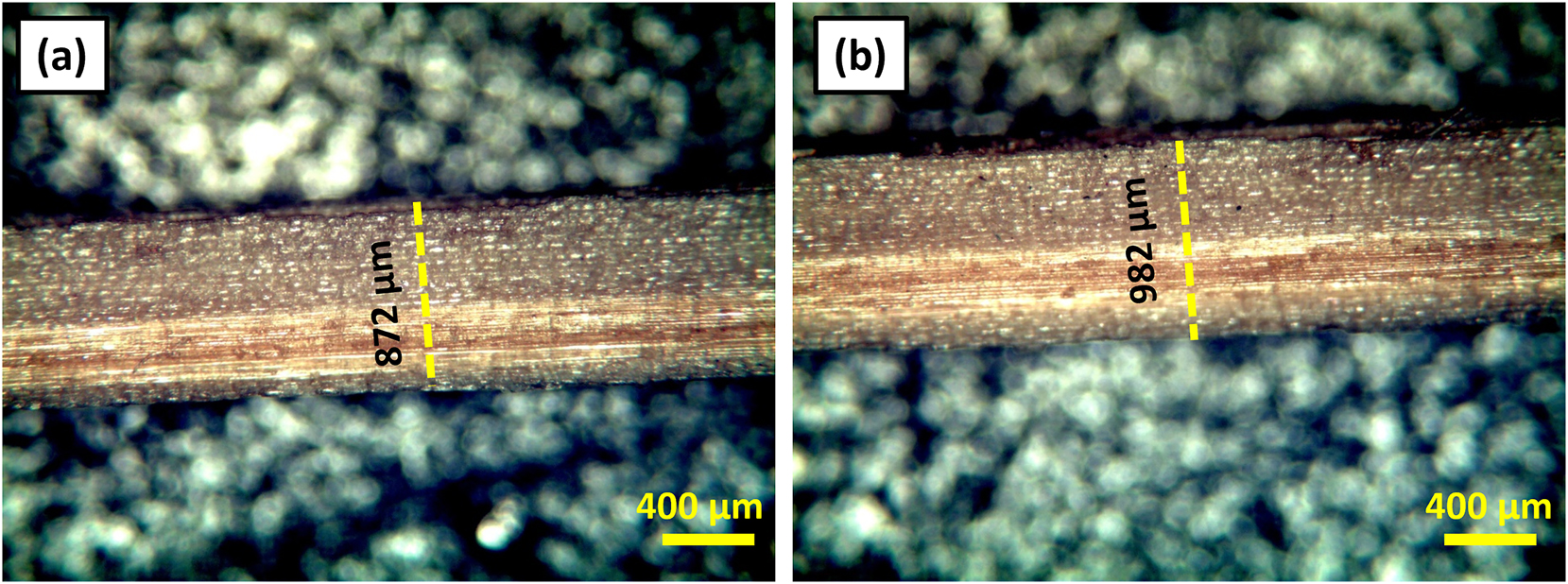

The optical microscope revealed the minimal diameter distribution due to irregular cutting methods and different slabs used for extraction, as shown in Figure 1a and b. The observed average diameter values were between 0.8 and 0.1 mm. The mechanical properties of fibers heavily depend on diameter because smaller diameters lead to increased contact area with the matrix.

Diameter measurement of bamboo fibers extracted from two different bamboo slabs (a) and (b).

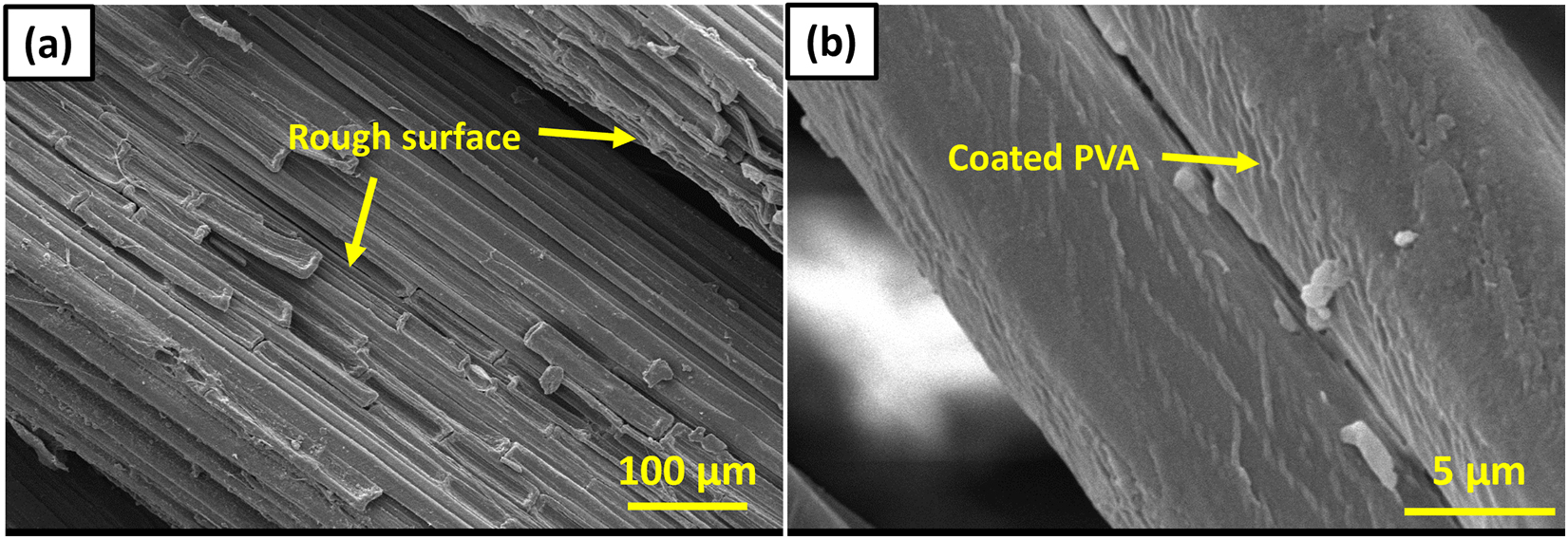

SEM was used to evaluated the impact of 3 % PVA treatment on bamboo fiber with and without PVA treatment. The SEM images showed substantial variations on the fiber surface that probably led to better mechanical characteristics in the composite material. The untreated bamboo fibers under SEM imaging show a rough natural surface pattern that is typical for plant fibers (Figure 2a). Bamboo fibers display a surface structure composed of grooves together with pores and visible natural irregularities that define the bamboo material. Surface features on fibers create an extensive contact area that enables better bonding with the matrix material. Fiber hydrophilicity increases because of the pores and grooves that exist on the surface. The fibers present an uneven surface texture following treatment because they contain noticeable imperfections, which might reduce their bonding efficiency with the resin matrix during composite manufacturing. The imperfections found on the fibers lead to increased moisture absorption that damages the durability of the final composite materials.

SEM micrographs of (a) untreated extracted bamboo fiber, and (b) 3 wt.% PVA-treated bamboo fiber.

The SEM image of bamboo fibers treated with 3 % PVA (Figure 2b) shows considerable alterations to the surface characteristics. The application of PVA creates an even surface texture that surpasses the surface quality of untreated fibers. Surface roughness decreases in bamboo fibers when they receive 3 % PVA treatment because they display fewer visible pores and grooves. The uniform surface appearance indicates PVA material has covered the fiber surface by filling all the spaces and irregularities found in untreated fibers. The smooth surface of fibers treated with 3 % PVA stands as a key factor for improving bonding quality between fibers and epoxy resin matrix. Better interaction and stronger adhesion occur between the fiber and resin because the smooth surface enhances their bonding connection. The improved mechanical properties of the composite are expected due to the enhanced load transfer capability between fiber and matrix achieved through PVA treatment.

The dissociation of PVA polymer chains during water dissolution enables hydroxyl (–OH) groups to establish hydrogen bonds with water molecules, which results in a stable colloidal solution. The hydrated PVA molecules function as independent polymeric chains that possess negatively charged hydroxyl groups that attach to bamboo fiber surfaces. The PVA solution bonds with bamboo fibers through hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces because both contain cellulose with hydroxyl functional groups. The PVA molecules align with the fiber surface during evaporation, while water leaves the solution because it adheres to form a thin and uniform coating. The applied coating blocks access to free hydroxyl to reduce water absorption ability. The PVA-fiber bond improves adhesion through better interfacial bonding because it strengthens the composite material.

3.2 Density measurement and mechanical properties

Measurement of the density of treated and untreated fiber composites was conducted using Archimedes’ principle. The results showed that treated and untreated composite materials possess equivalent density measurements with an average density value of 1.02 g cm−3. The density measurement values differ slightly because voids trapped air in the samples. The density measurements of the prepared composites appear in Table 1.

Density of untreated and PVA-treated bamboo/epoxy composites at different fiber weight fractions (%).

| Fiber weight fraction (%) | Density of untreated fiber composite (g cm−3) | Density of 3 wt.% PVA-treated fiber composite (g cm−3) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.12 | 1.12 |

| 20 | 1.019 | 1.021 |

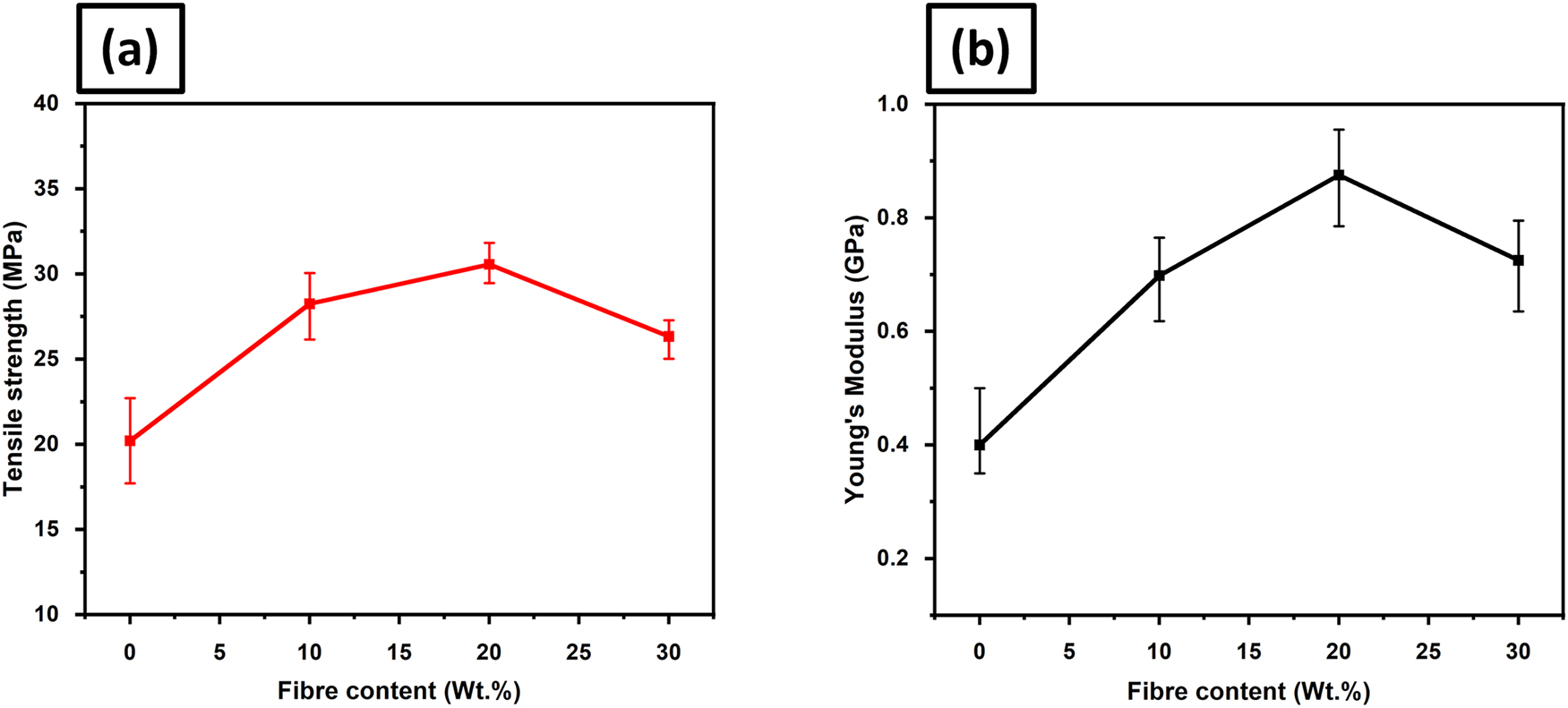

The production process included the fabrication of composites with different weight percentages (0 %, 10 %, 20 %, and 30 %) of fiber content. The tensile properties of the untreated composite are shown in Figure 3a and b. Tensile strength values remained low at lower fiber content because of inadequate fiber distribution inside the matrix until the fiber content reached 20 wt.%, which led to strength and modulus improvements. The properties decreased when the fiber content reached 30 wt.% because epoxy was insufficient to coat all fibers properly, thus leading to impaired load transfer throughout the matrix. 28 The main reason behind defect formation was the poor distribution of fibers throughout the material. The created defects functioned as crack initiation points that led to composite failure when subjected to low stress.

Tensile properties of untreated composites: (a) tensile strength, and (b) Young’s modulus.

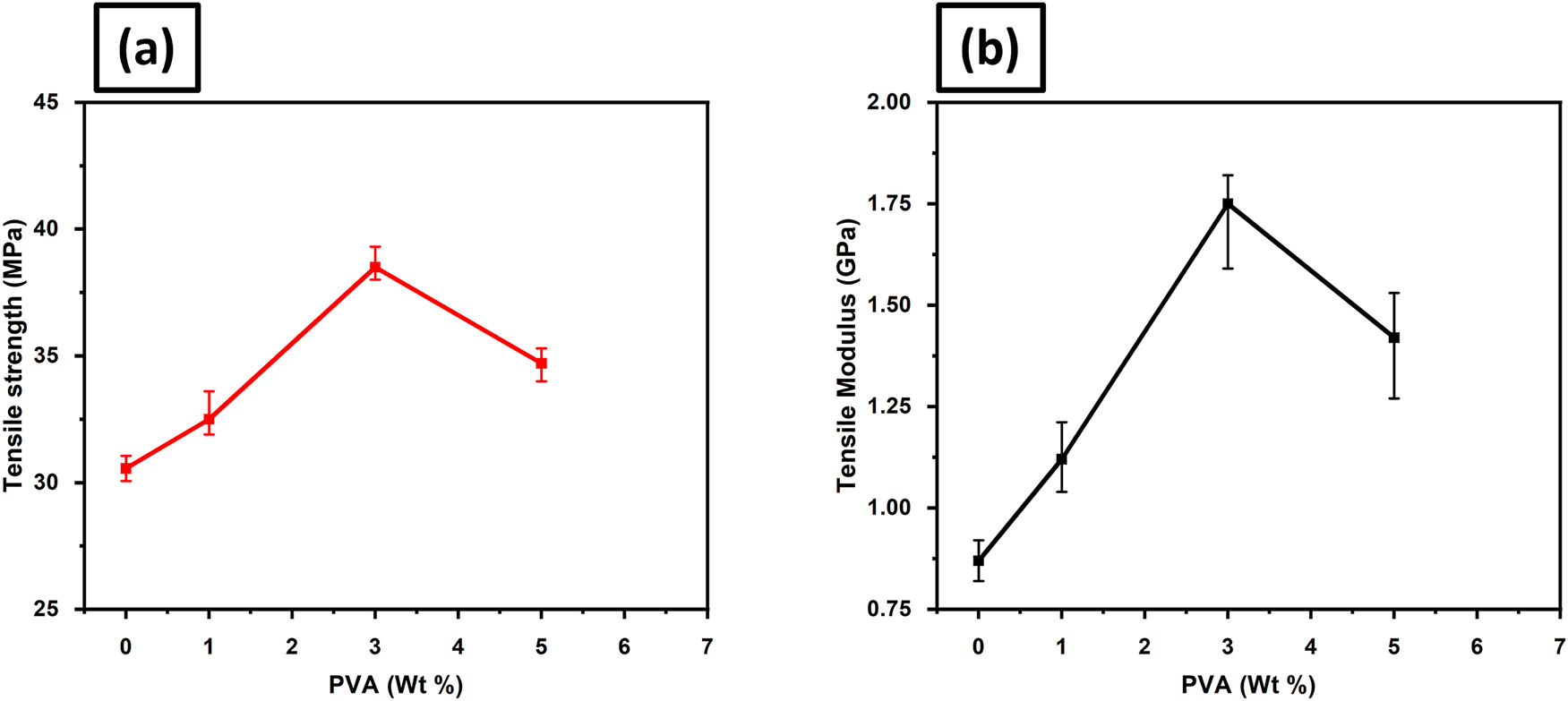

The tensile test results of composites treated with 1 %, 3 %, and 5 % PVA are reported in Figure 4a and b. Among these, 3 % treatment proved optimal, producing superior mechanical properties. The strength of the composite was enhanced to 38.5 from 31.5 MPa, alongside a doubling of the modulus from 0.875 to 1.75 GPa. This improvement can be attributed to the enhanced fiber–matrix adhesion resulting from the PVA treatment. The PVA coating forms a uniform and continuous layer over the bamboo fibers, which reduces surface irregularities and microvoids that act as stress concentration points. As a result, applied loads are more effectively transferred from the epoxy matrix to the reinforcing fibers, delaying the onset of failure. Additionally, the treatment reduces the hydrophilic nature of the bamboo fibers, decreasing moisture uptake and preventing fiber swelling and degradation, which would otherwise weaken the composite. The presence of PVA also promotes better wetting of the fiber by the epoxy, improving interfacial contact and creating a more cohesive structure. Consequently, the composite demonstrates a more uniform stress distribution and improved resistance to crack initiation and propagation, resulting in higher tensile strength and stiffness. This indicates that the PVA treatment not only modifies the fiber surface chemistry but also contributes to the long-term durability of the composite under mechanical loading.

Tensile properties of 20 % treated bamboo composites: (a) tensile strength, and (b) Young’s modulus.

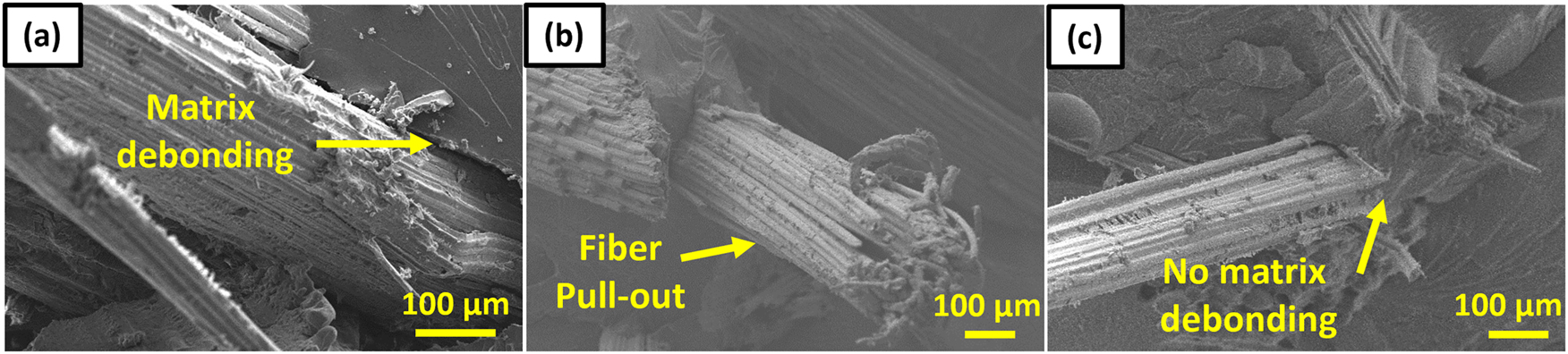

The SEM analysis of broken composite specimens provides evidence backing these results. The SEM images of untreated fiber composites show that fibers pull out (Figure 5b) from the interface, along with gaps that demonstrate poor bonding (Figure 5a) and ineffective load distribution. The SEM image of the 3 % PVA-treated composite demonstrates fibers that penetrate the epoxy matrix strongly while displaying minimal pull-out. The PVA coating creates a seamless fiber surface, which improves epoxy infiltration, thus decreasing interface weaknesses/strong bonding (Figure 5c) that strengthen the composite structure. The tensile properties enhancement becomes optimal when using 3 % PVA treatment because of these observed morphological improvements. In summary, the SEM images of fractured specimens revealed stronger interfacial adhesion in PVA-treated composites, with minimal fiber pull-out compared to untreated fibers. This morphological evidence, combined with enhanced tensile properties and reduced water uptake, supports the conclusion that PVA treatment forms a uniform surface coating on fibers, thereby improving fiber–matrix bonding.

SEM micrographs of the fractured surface of a 20 % fiber-reinforced composite: (a) and (b) untreated fibers, and (c) PVA-treated fibers.

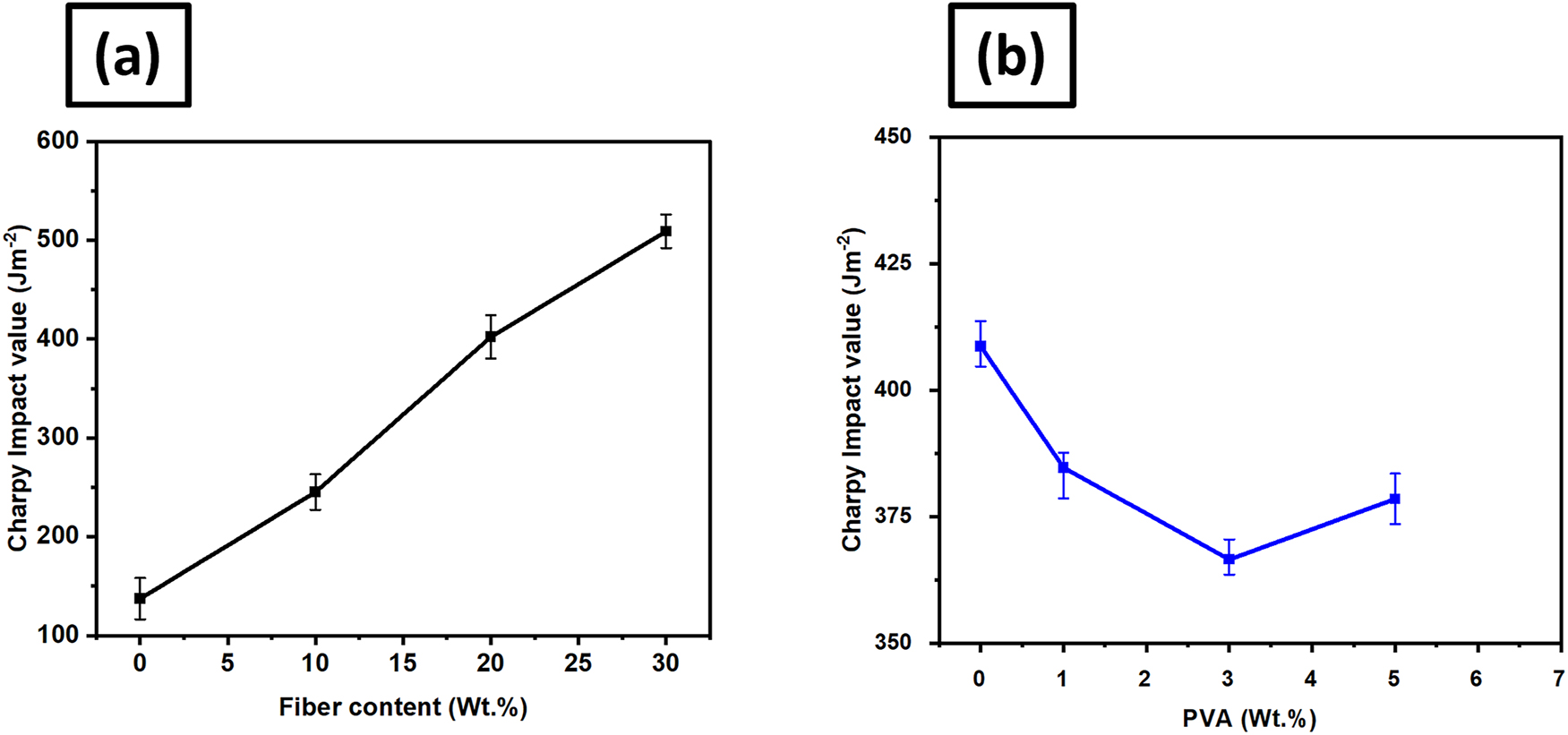

The impact strength of the composite depends on four main factors: the wetting behavior of fibers towards the matrix, fiber content, and friction, and the interfacial bond between the fibers and matrix. 29 The strength of impact energy absorption by composites depends heavily on the extent to which fibers pull out from the material. Accordingly, the impact energy of the untreated composite increases with increased fiber content, showing improved energy absorption characteristics (Figure 6a). While the composite is dependent on the epoxy matrix at 0 %, hence giving the lowest impact energy, the impact energy rises progressively at 10 %, 20 %, and 30 % due to increased energy dissipation through mechanisms such as fiber pull-out and crack deflection. The Charpy impact test results show that the impact strength of the 3 % PVA-treated composite is lower compared to the untreated composite. The impact strength was reduced from 408 J m−2 in the untreated composite to 366 J m−2 in the treated one (Figure 6b). This decline can be attributed to the improved fiber–matrix adhesion resulting from PVA treatment. Poor fiber–matrix bonding in the case of an untreated composite results in easy fiber pull-out during impact loading and, therefore, increased energy absorption. 30 The improved interfacial adhesion in a PVA-treated composite would consequently restrain the process of fiber pull-out, giving way to more brittle fracture with decreased energy absorption during impact loading. These results align with composite theory, which predicts that stronger fiber–matrix adhesion increases tensile strength and stiffness due to more efficient stress transfer, but simultaneously reduces impact strength as fiber pull-out is restricted. Although detailed modelling, such as the rule of mixtures or Halpin–Tsai equations, was not performed here, the experimental trends observed are in agreement with these established frameworks.

Charpy impact properties of (a) untreated fiber composite with variable fiber loading and (b) 20 % treated fiber composite with variable PVA concentration.

Another contributing factor to the observed reduction in impact strength is the modification of fiber surface characteristics by PVA treatment. The smooth PVA coating improves fiber–matrix adhesion and creates a more uniform interface; however, this stronger bonding reduces the fibers’ ability to deflect or absorb sudden impact forces. In untreated fibers, the rough surface allows for minor debonding and micro-crack formation, which serve as mechanisms to dissipate impact energy gradually. In contrast, the strong interfacial bonding in PVA-treated composites facilitates direct crack propagation through the matrix and fiber network, making failures under impact more abrupt and less energy-absorbing. This also indicates that treated composites predominantly exhibit brittle fracture modes, whereas untreated composites show mixed-mode fractures, including fiber pull-out and localized debonding, which contribute to higher impact energy absorption. Despite this reduction, the impact strength of the composite treated with 3 % PVA remains satisfactory for applications where tensile performance is prioritized over impact resistance.

Compared to conventional fiber surface treatments such as NaOH and silane, PVA offers several advantages. While NaOH effectively removes surface impurities and increases roughness for better mechanical interlocking, it involves hazardous chemicals and generates alkaline wastewater, raising environmental and safety concerns. Silane treatments improve interfacial bonding through covalent linkages but often require organic solvents and specialized handling. In contrast, PVA is water-soluble, non-toxic, and biodegradable, providing a safer and more sustainable alternative. Additionally, PVA treatment not only enhances fiber–matrix adhesion but also acts as a moisture barrier, achieving a balance between mechanical performance and environmental compatibility.

3.3 Water absorption analysis

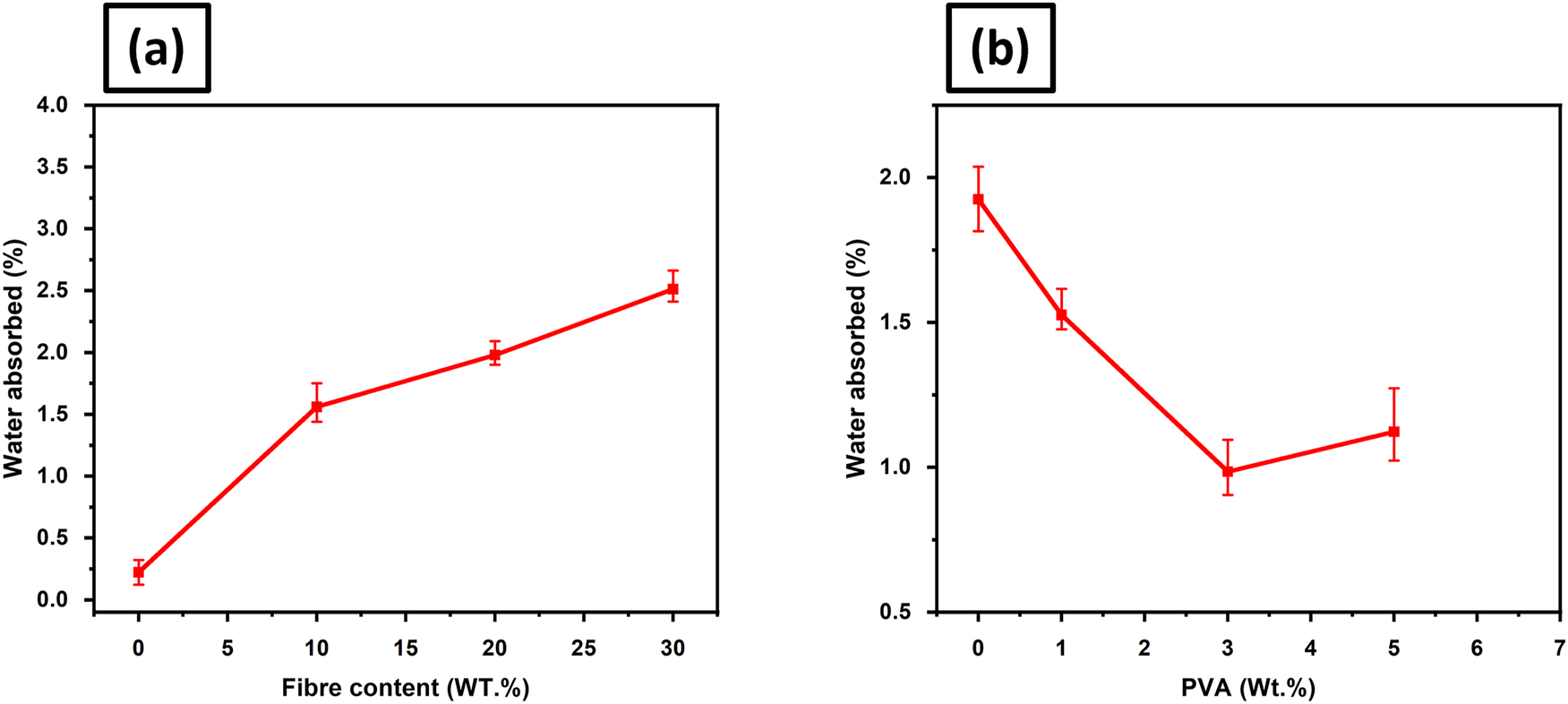

While the fiber content increases from 0 % to 30 %, water absorption characteristics increase gradually for the untreated fiber–epoxy composite (Figure 7a). For the 0 % fiber composite, the absorption of water will be minimal since the epoxy matrix itself is hydrophobic and resists moisture uptake. In the increase of fiber loadings up to 10 %, 20 %, and 30 %, the water absorption ability of the composite increases, which is due to the hydrophilic nature of bamboo fibers, because of the presence of hydroxyl groups, which can easily interact with water molecules. 31 Increased fiber content also leads to an increase in voids and capillary pathways in the composite, thus allowing increased moisture penetration. The increased water absorption may cause the fibers to swell and the loss of some mechanical properties, possibly degrading the composite during its service.

Water absorption properties of (a) untreated fiber composite with variable fiber loading, and (b) 20 % treated fiber composite with variable treatment concentration.

On the other hand, PVA-treated fiber composites show less water absorption due to the protective coating of PVA on the surface of the fiber (Figure 7b). Among the treated composites, 3 % PVA treatment has the lowest water uptake, showing the best water resistance. While PVA is inherently hydrophilic due to the presence of hydroxyl groups, its interaction with the epoxy matrix and alignment along the fiber surface creates a dense, uniform layer that acts as a physical barrier to water penetration. The PVA coating effectively fills surface microvoids and smooths irregularities on the fiber, reducing pathways for water ingress. Moreover, the hydrogen bonding between PVA and the bamboo fibers strengthens the interfacial region, further limiting fiber swelling when exposed to moisture. Collectively, these effects result in a composite that resists water absorption, minimizes fiber degradation, and maintains mechanical integrity under humid conditions, demonstrating PVA’s dual role as a hydrophilic modifier that simultaneously functions as a moisture barrier.

In contrast, composite materials treated with 1 and 5 % PVA showed different patterns in water absorption characteristics. The 1 % PVA treatment reduces the water uptake slightly compared to the untreated fibers due to insufficient surface coverage; it is not as effective as the 3 % treatment. On the other hand, the 5 % PVA-treated composite exhibits a slightly higher water absorption compared to the 3 % treatment. The excess PVA can create a thick layer on the fiber surface, hence causing minor defects or microvoids that may allow moisture intrusion after some time. Too much PVA reduces the efficiency of bonding between fibers and matrices, creating microcracks that could allow water to enter. In general, test results indicate that the 3 % PVA treatment offers the best compromise in terms of a trade-off between the reduction of water absorption and the quality of the interfacial bonding with the epoxy matrix. Thus, an optimum treatment would enhance the long-term durability of the composite in high-humidity or moisture application conditions. These results also illustrated that surface modification was one of the effective means of enhancing natural fiber-reinforced composite resistance to moisture.

4 Conclusions

In this work, PVA treatment was proposed as one of the best candidates to improve the mechanical properties and resistance to water absorption of bamboo epoxy composites. It has been reported that a 3 % PVA treatment enhances the adhesion between fiber–matrix, which improves the tensile strength from 32 to 39 MPa and modulus from 0.9 to 1.8 GPa, as analyzed by SEM. Stronger interfacial bonding improved the stress transfer and developed the load-carrying capacity of the composite material. However, the impact strength was reduced from 408 J m−2 to 366 J m−2 due to a restricted fiber pull-out. The failure mode became more brittle. Water absorption tests show a strong dependence of fiber content on water absorption characteristics, while PVA treatment reduced the water uptake due to the protective coating formed. Treatment with 3 % PVA showed the lowest moisture absorption and hence improved the long-term durability. In short, PVA treatment enhances bamboo fiber composites for high-strength and durability applications. Further studies may be carried out on the optimization of treatment concentrations or hybridization of fibers to give better impact properties without affecting other properties.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Pakistan Science Foundation for funding this work via Project No. PSF/Res/KPK-GIKI/Eng. (170). GIK Institute is also acknowledged for providing basic synthesis and characterization facilities.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Conceptualization: Noor Fatima, Danish Tahir, Muhammad Ramzan Abdul Karim. Investigation: Noor Fatima, Danish Tahir, Muhammad Rehan. Data curation: Noor Fatima, Danish Tahir, Syed Abbas Raza, Muhammad Ramzan Abdul Karim. Writing: Noor Fatima, Danish Tahir, Muhammad Ramzan Abdul. Karim, Muhammad Rehan.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Work funded by the Pakistan Science Foundation under Project No. PSF/Res/KPK-GIKI/Eng. (170) and GIK Institute’s Graduate Assistantship Scheme (GA-1).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Tahir, D.; Fatima, N.; Rehan, M.; Hu, H. Sustainable Jute Fiber-Reinforced Auxetic Composites with Both In-Plane and Out-of-Plane Auxetic Behaviors. Polym. Compos. 2025, 1; https://doi.org/10.1002/PC.29825.Search in Google Scholar

2. Tahir, D.; Fatima, N.; Rehan, M.; Hu, H. Sustainable Re-entrant Hemp/Polylactic Acid Nonwoven Composites with In-Plane and Out-of-Plane Auxeticity. Smart Mater. Struct. 2025, 34 (8), 085010; https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665X/ADF614.Search in Google Scholar

3. Aruchamy, K.; Mylsamy, B.; Palaniappan, S. K.; Subramani, S. P.; Velayutham, T.; Rangappa, S. M.; Siengchin, S. Influence of Weave Arrangements on Mechanical Characteristics of Cotton and Bamboo Woven Fabric Reinforced Composite Laminates. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2023, 42 (15–16), 776–789; https://doi.org/10.1177/07316844221140350.Search in Google Scholar

4. Karthik, A.; Jeyakumar, R.; Sampath, P. S.; Soundarararajan, R. Mechanical Properties of Twill Weave of Bamboo Fabric Epoxy Composite Materials. SAE Technical Papers 2022. Published online December 23; https://doi.org/10.4271/2022-28-0532.Search in Google Scholar

5. Ahmad, J.; Zhou, Z.; Deifalla, A. F. Structural Properties of Concrete Reinforced with Bamboo Fibers: A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 844–865; https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMRT.2023.03.038.Search in Google Scholar

6. Musthaq, M. A.; Dhakal, H. N.; Zhang, Z., Barouni, A.; Zahari, R. The Effect of Various Environmental Conditions on the Impact Damage Behaviour of Natural-Fibre-Reinforced Composites (NFRCs) – A Critical Review. Polymers 2023, 15 (5), 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM15051229.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Karim, M. R. A.; Tahir, D.; Haq, E. U.; Hussain, A.; Malik, M. S. Natural Fibres as Promising Environmental-Friendly Reinforcements for Polymer Composites. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2020, 29 (4), 277–300; https://doi.org/10.1177/0967391120913723.Search in Google Scholar

8. Tahir, D.; Li, X.; Razbin, M.; Singh, K.; Ravindran, A.; Peng, S.; Wu, S. Eco-Friendly Flexible and Stretchable Printed Electronics Based on Sustainable Elastic Substrate and Ink. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2025, 6, 4883–5230; https://doi.org/10.1039/D5TA06546A.Search in Google Scholar

9. Ali, A.; Adawiyah, R.; Rassiah, K.; Ng, W. K.; Arifin, F.; Othman, F.; Hazin, M. S.; Faidzi, M.; Abdullah, M.; Megat Ahmad, M. Ballistic Impact Properties of Woven Bamboo- Woven E-Glass- Unsaturated Polyester Hybrid Composites. Def. Technol. 2019, 15 (3), 282–294; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2018.09.001.Search in Google Scholar

10. Gao, X.; Zhu, D.; Fan, S.; Rahman, M. Z.; Guo, S.; Chen, F. Structural and Mechanical Properties of Bamboo Fiber Bundle and Fiber/Bundle Reinforced Composites: A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 1162–1190; https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMRT.2022.05.077.Search in Google Scholar

11. Elfaleh, I.; Abbassi, F.; Habibi, M.; Ahmad, F.; Guedri, M.; Nasri, M.; Garnier, C. A Comprehensive Review of Natural Fibers and Their Composites: An Eco-friendly Alternative to Conventional Materials. Res. Eng. 2023, 19, 101271; https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RINENG.2023.101271.Search in Google Scholar

12. Zheng, Z.; Yan, N.; Lou, Z.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, R.; Liu, C.; Xu, L. Modification and Application of Bamboo-Based Materials: A Review – Part I: Modification Methods and Mechanisms. Forests 2023, 14 (11), 2219. https://doi.org/10.3390/F14112219.Search in Google Scholar

13. Irvani, H.; Mahabadi, H. A.; Khavanin, A.; Variani, A. S. Improving the Thermal and Hydrophobic Properties of Bamboo Biocomposite as Sustainable Acoustic Absorbers. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15 (1), 1–12; https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-025-87653-W;SUBJMETA.Search in Google Scholar

14. Markandan, K.; Lai, C. Q. Fabrication, Properties and Applications of Polymer Composites Additively Manufactured with Filler Alignment Control: A Review. Compos. B Eng. 2023, 256, 110661; https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPOSITESB.2023.110661.Search in Google Scholar

15. Uusi-Tarkka, E. K.; Skrifvars, M.; Haapala, A. Fabricating Sustainable All-Cellulose Composites. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11 (21), 10069. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/APP112110069.Search in Google Scholar

16. Aruchamy, K.; Palaniappan, S. K.; Lakshminarasimhan, R.; Mylsamy, B.; Dharmalingam, S. K.; Ross, N. S.; Pavayee Subramani, S. An Experimental Study on Drilling Behavior of Silane-Treated Cotton/Bamboo Woven Hybrid Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Polymer Composites. Polymers 2023, 15 (14), 3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM15143075.Search in Google Scholar

17. Karthik, A.; Daniel, J. D. J.; Sampath, P. S.; Thirumurugan, V. Effect of Alkali Treatment on Cotton/Bamboo Fibres for Application as a Reinforcement Material. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E: J. Process Mech. Eng., 2024, 238 (6), 2670–2680; https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089231162292.Search in Google Scholar

18. Tahir, D.; Ramzan, M.; Karim, A.; Hu, H.; Naseem, S.; Rehan, M.; Zhang, M. Sources, Chemical Functionalization, and Commercial Applications of Nanocellulose and Nanocellulose-Based Composites: A Review. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14 (21), 4468; https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM14214468.Search in Google Scholar

19. Ramachandran, A. R.; Mavinkere Rangappa, S.; Kushvaha, V.; Khan, A.; Seingchin, S.; Dhakal, H. N. Modification of Fibers and Matrices in Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43 (17), 2100862; https://doi.org/10.1002/MARC.202100862.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Samanth, M.; Subrahmanya Bhat, K. Conventional and Unconventional Chemical Treatment Methods of Natural Fibres for Sustainable Biocomposites. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2023, 3, 100034; https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCCA.2023.100034.Search in Google Scholar

21. Liao, Z.; Hu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chen, K.; Qiu, C.; Yang, J.; Yang, L. Investigation into the Reinforcement Modification of Natural Plant Fibers and the Sustainable Development of Thermoplastic Natural Plant Fiber Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM16243568.Search in Google Scholar

22. Shah, I. A.; Kavitake, D.; Tiwari, S.; Devi, P. B.; Reddy, G. B.; Jaiswal, K. K.; Jaiswal, A. K.; Shetty, P. H. Chemical Modification of Bacterial Exopolysaccharides: Antioxidant Properties and Health Potentials. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100824; https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CRFS.2024.100824.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Valentini, F.; Galloni, P.; Brancadoro, D.; Conte, V.; Sabuzi, F. A Stoichiometric Solvent-Free Protocol for Acetylation Reactions. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 842190; https://doi.org/10.3389/FCHEM.2022.842190/BIBTEX.Search in Google Scholar

24. Thandavamoorthy, R.; Devarajan, Y.; Thanappan, S. Analysis of the Characterization of NaOH-Treated Natural Cellulose Fibre Extracted from Banyan Aerial Roots. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13 (1), 1–8; https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-023-39229-9;SUBJMETA.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Massaguni, M.; Djafar, Z.; Zulkifli, R.; Arma, L. H. Enhancing Mechanical Strength of Bamboo Parring (Gigantochloa atter) Fiber with Alkaline Treatment for flame-retardant Composite. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5 (1), 1–14; https://doi.org/10.1007/S43939-025-00295-7/FIGURES/9.Search in Google Scholar

26. Rothenhäusler, F.; Ouali, A. A.; Rinberg, R.; Demleitner, M.; Kroll, L.; Ruckdaeschel, H. Influence of Sodium Hydroxide, Silane, and Siloxane Treatments on the Moisture Sensitivity and Mechanical Properties of Flax Fiber Composites. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45 (10), 8937–8948; https://doi.org/10.1002/PC.28386.Search in Google Scholar

27. Buson, R. F.; Melo, L. F. L.; Oliveira, M. N.; Rangel, G. A. V. P.; Deus, E. P. Physical and Mechanical Characterization of Surface Treated Bamboo Fibers. Sci. Technol. Mater. 2018, 30 (2), 67–73; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stmat.2018.03.002.Search in Google Scholar

28. Abdul Karim, M. R.; Tahir, D.; Khan, K. I.; Hussain, A.; Haq, E. U.; Malik, M. S. Improved Mechanical and Water Absorption Properties of Epoxy-Bamboo Long Natural Fibres Composites by Eco-friendly Na2CO3 Treatment. Plast., Rubber Compos. 2022, 52 (2), 114–127; https://doi.org/10.1080/14658011.2022.2030152.Search in Google Scholar

29. Abdul Karim, M. R.; Tahir, D.; Hussain, A.; Ul Haq, E.; Khan, K. I. Sodium Carbonate Treatment of Fibres to Improve Mechanical and Water Absorption Characteristics of Short Bamboo Natural Fibres Reinforced Polyester Composite. Plast., Rubber Compos. 2020, 49 (10), 425–433; https://doi.org/10.1080/14658011.2020.1768336.Search in Google Scholar

30. Tahir, D.; Abdul Karim, M. R.; Hu, H. Analysis of Mechanical and Water Absorption Properties of Hybrid Composites Reinforced with Micron-Size Bamboo Fibers and Ceramic Particles. Int. Polym. Process. 2023, 39 (1), 115–124; https://doi.org/10.1515/IPP-2023-4374/MACHINEREADABLECITATION/RIS.Search in Google Scholar

31. Tahir, D.; Karim, M. R.; Wu, S.; Rehan, M.; Tahir, M.; Zaigham, S. B.; Riaz, N. Impact of Fiber Diameter on Mechanical and Water Absorption Properties of Short Bamboo Fiber-Reinforced Polyester Composites. Int. Polym. Process. 2024, 39 (3), 317–326; https://doi.org/10.1515/IPP-2023-4458/MACHINEREADABLECITATION/RIS.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.