Abstract

Conditional power of survival endpoints at interim analyses can support decisions on continuing a trial or stopping it for futility. When a cure fraction becomes apparent, conditional power cannot be calculated accurately using simple survival models, e.g. the exponential model. Non-mixture models consider such cure fractions. In this paper, we derive conditional power functions for non-mixture models, namely the non-mixture exponential, the non-mixture Weibull, and the non-mixture Gamma models. Formulae were implemented in the R package CP. For an example data set of a clinical trial, we calculated conditional power under the non-mixture models and compared results with those under the simple exponential model.

1 Introduction

Clinical trials often consider survival endpoints which occur relatively late compared to treatment. Interim analyses are common practice to decide early whether to stop the trial for ethical reasons or futility. Conditional power is an important concept in this decision-making process. Conditional power is defined as the probability of achieving a significant result at the end of the study in case of an existing effect, given data from interim analysis. A commonly applied simple approach to estimate (conditional) power is to use an exponential survival model. Here, the hazard is constant and survival tends to zero as time tends to infinity. However, there are several clinically relevant questions where this assumption is not appropriate. For example, cure or relapse of disease might be of interest. Here, not all individuals experience an event resulting in a plateau of the survival curves. Other non-medical examples are discharge of prisoners or malfunction of a particular component of a car. For substantial cure fractions it is clear that the simple exponential model is not appropriate to explain the data. Lambert [1] gives a good overview of cure fraction models which are better suited for that situation, e.g. the so-called non-mixture models. Conditional power formulae for the simple exponential model are already derived by Andersen [2]. For cure fraction models, no such formulae are available so far. In the present paper, we aim at closing this gap: In Section 2, a summary for the exponential model is provided including corresponding unconditional and conditional power estimates. Section 3 introduces the non-mixture models. The corresponding unconditional and conditional power functions are derived for the non-mixture exponential model under the proportional hazard assumption. We provide a simulation study to interpret the unconditional power estimates and to compare them with corresponding conditional estimates. We also provide a simulation study to empirically validate conditional power estimates for selected scenarios. Finally, we consider alternative parametric assumptions for baseline hazard, namely non-mixture Weibull and non-mixture Gamma models. In Section 4, the conditional power formulae will be applied to a data set of a randomised clinical trial. The R package CP containing all formulae derived in this paper is presented in brief. Results are discussed in Section 5. Theorems and some auxiliary results can be found in the Appendix.

2 Subjects of interest

In this section, we recall and describe the survival models studied in the present paper. We restrict our considerations to comparisons of two treatment groups (1 and 2) throughout. First, we consider the exponential model and corresponding unconditional and conditional power estimates. Then, we introduce survival fractions and specify the class of models considered here.

2.1 The exponential survival model

In the simplest way, survival

with the constant hazard

The hazard ratio is defined as

For superiority trials, the test hypotheses are

The parameter

and with it, the hazard ratio can be estimated as

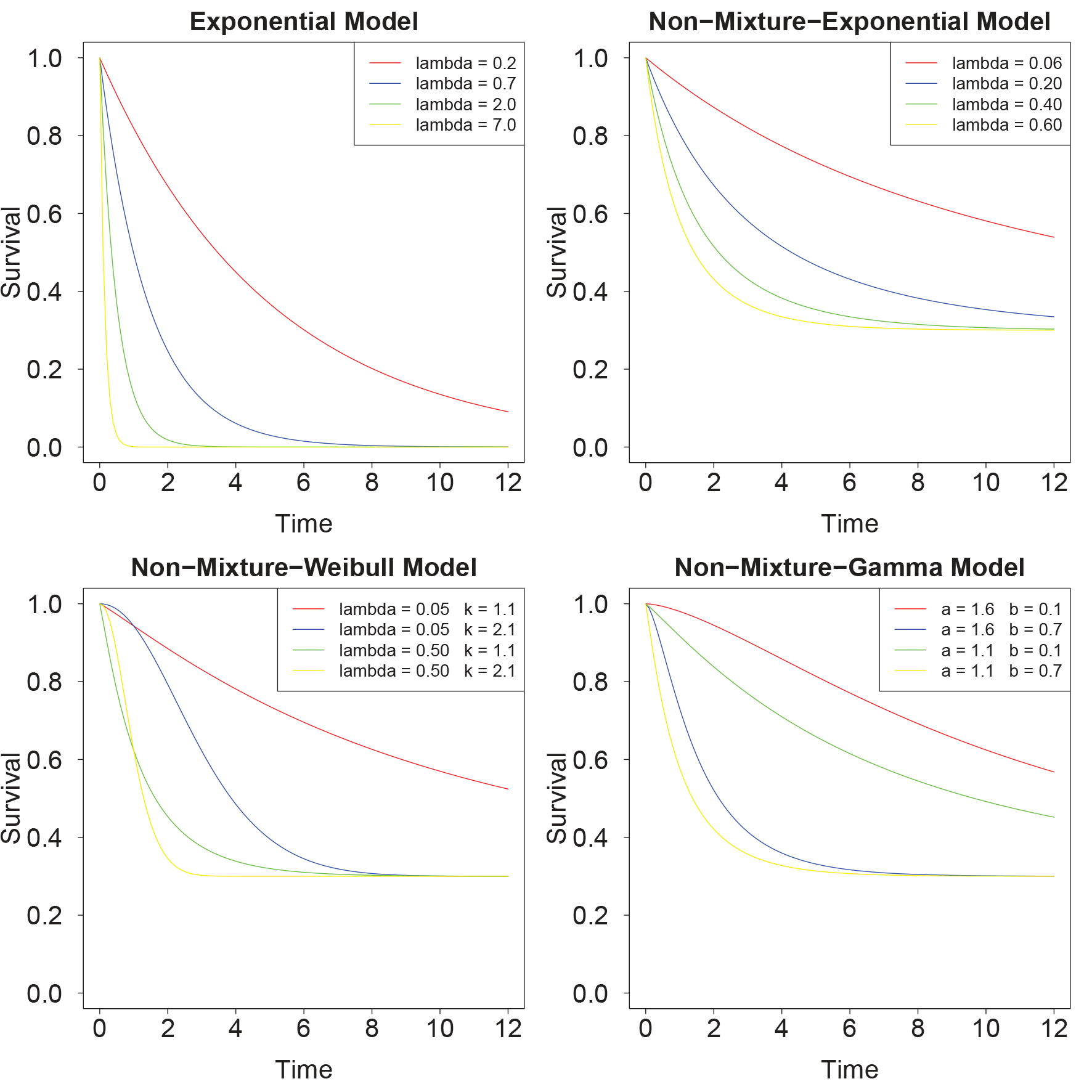

Examples for the exponential survival model can be found in Figure 1.

2.2 Unconditional power based on the exponential model

According to Andersen [2], one way of defining an appropriate test statistic of the difference in survival is

With Theorem 1 in Section A of the Appendix, one can define the asymptotic power function by

where

2.3 Conditional power based on the exponential model

Suppose that data

as the conditional test statistic.

Using Theorem 2 in Section A of the Appendix, the asymptotic conditional power function given data

where means and variances under the null and under the alternative are

Here,

It should be mentioned that the formulae derived here are not exactly the same as those proposed by Andersen [2]. The main difference is our centering of the asymptotic conditional power function (3) on

2.4 Survival models with cure fractions

If a relevant cure fraction is observed, the application of the exponential survival model considered above is no longer appropriate. In the literature, two parametric models dealing with cure fractions are most frequently in use: mixture and non-mixture models, cf. Martinez et al. [3]. We favour parametric models due to the availability of maximum likelihood methods. They are easier to interpret and provide higher power in statistical testing than comparable non-parametric models. The mixture model can be formulated as the sum of the proportion of the survivors and the weighted survival of the non-survivors [1]:

with a cure fraction

With the same notation and limit behaviour, the improper survival function of the non-mixture model reads as follows [1]:

In the present paper, we restrict considerations on non-mixture models. They require the specification of proper survival functions

i.e. the hazard ratio is the ratio of the

Examples of the four parametric survival models considered here. For the non-mixture models, we assumed a survival fraction of 0.3 throughout this figure.

3 The non-mixture model with exponential survival

In this section, we derive the unconditional and conditional power formulae for the non-mixture exponential model. We perform a simulation study to illustrate the results of the unconditional power analysis and to compare them with those of the exponential model without assuming cure fractions. To validate our findings, we study the agreement of our conditional power estimates with empirical power estimates for selected scenarios. Finally, we consider parametric alternatives to the non-mixture exponential model.

3.1 Basic requirements

If

(see Lemma 1 in Section B of the Appendix) which yields the hazard ratio

Thus time independence of the hazard ratio can only be achieved if

resulting in eq. (4). For clarification, this does not mean that we assume constant hazards (cf. eq. (5)) as it would be the case for the simple exponential model. Again, we consider the hypotheses

An estimator of the hazard ratio under

(see Lemma 2 in Section B of the Appendix for more details).

3.2 Power estimate for the unconditional case

Similarly to eq. (1) in Section 2.2, one can start with

as the test statistic of interest, with

3.3 Power estimate for the conditional case

Again, we consider the situation that data

With the help of Theorem 4 in Section A of the Appendix, the asymptotic conditional power function given

3.4 Interpretation and comparison of unconditional power estimates

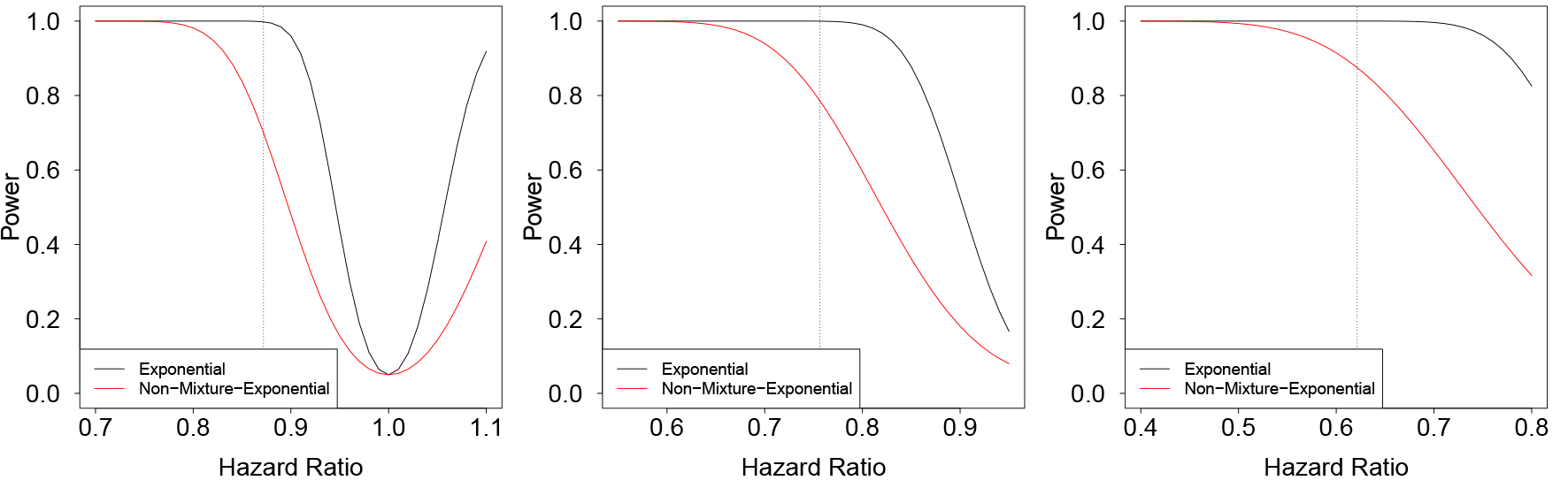

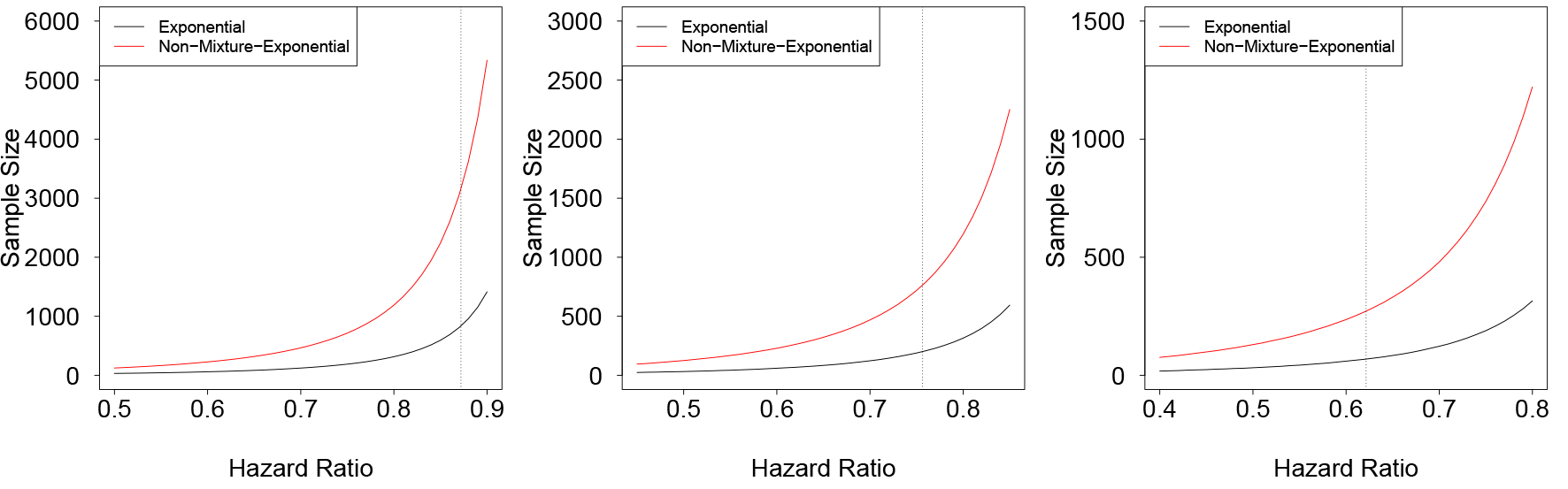

Here, we compare unconditional power estimates under the non-mixture exponential model with those of the simple exponential model. To illustrate the difference between the models, we choose

Scenario 1: We fix the baseline survival rate

Scenario 2: We set the survival rate of the standard arm to

Scenario 3: We assume a baseline survival rate

Assuming identical sample size and the same hazard ratio, power estimates under the non-mixture model are typically lower than those under the simple exponential model. Keeping the hazard ratio constant, the difference increases with baseline survival (cf. Figure 2). Survival rates can be chosen as one-, five-, or ten-year survival rates, for example, depending on the question of interest. These considerations also hold for the other non-mixture models considered here (non-mixture Weibull and non-mixture Gamma model, see below). In the situation of an interim analysis, available data might raise doubts regarding the survival model originally assumed. This might result in a revision of model parameters resulting in new power estimates. As expected, for both, exponential and non-mixture exponential models, power drops if the effect size is smaller than expected (see Figure 2).

Power for the exponential (black) and the non-mixture exponential model (red) for three different scenarios. Left panel:

Conversely, our formulae can be used to re-calculate the sample sizes for the scenarios considered in Figure 2. Results are shown in Figure 3.

Sample size estimation of the scenarios considered in Figure 2. Sample size is calculated to achieve a power of 80%. Left panel:

One can also interpret these results in terms of “information fraction”. Here, information fraction is defined as the ratio of the observed number of events at a given time point to the expected number of events at the end of the study. Then, the question is whether there are differences between the information fraction given a simple exponential model or given a non-mixture model. As mentioned above, event rates differ between both model types. The simple exponential model has a constant hazard whereas the hazard of the non-mixture model changes over time, being high at the early phase of the trial and decreasing to zero in the later phase of the trial. Thus, information fraction of an underlying non-mixture model will be higher at earlier time points and lower at later time points of a study compared to the information fraction under a simple exponential model at the same time points.

3.5 Empirical accuracy of the conditional power estimates

In this section, we illustrate accuracy of our conditional power formula for the non-mixture exponential model by performing a simulation study. The simulation study is implemented in the following way. First, we specify the parameters

Scenario 1: We choose a baseline survival rate

Scenario 2: We set the survival rate of the standard arm to

Scenario 3: We assume a baseline survival rate

As one can see, conditional power estimates and Wald test results are in good agreement for the selected scenarios. To facilitate further simulations, we provide the corresponding R script as supplement material.

3.6 Alternative parametric assumptions for baseline hazard

The non-mixture exponential model might not be flexible enough to model the data adequately. Two possible alternatives are considered here: the non-mixture Weibull model and the non-mixture Gamma model. We introduce their notation now. The derivation of the (conditional) power functions is similar to that of the non-mixture exponential model. Results are presented in the Appendix.

3.6.1 Weibull-type survival

The survival function of group

with scale parameter

Examples for the non-mixture Weibull model can be found in Figure 1.

For a derivation of the conditional power formula, we refer to Section C.2 of the Appendix.

3.6.2 Gamma-type survival

Another option to increase flexibility is to model survival functions with the Gamma distribution. The main difference to the non-mixture Weibull model is a different shape of the hazard function (see Remark 3 in Section B of the Appendix).

The incomplete Gamma function of the upper bound is defined by

and the Gamma function is given by

The regularised incomplete Gamma function of the upper bound is defined by

Then, the survival function of group

with shape parameter

Examples for the non-mixture Gamma model can be found in Figure 1.

We refer to Section C.3 of the Appendix for a derivation of the conditional power formula.

4 Application

The unconditional and conditional power formulae for the exponential and the non-mixture models were implemented in the R package CP which we describe in the following. A function for the comparison of these models is also provided. To demonstrate the models and to illustrate their differences, we apply the package to a data set of a clinical trial for which a futility analysis has been performed during interim analysis.

4.1 The R package CP

We implemented the formulae derived in this paper in the framework of the R package CP which can be downloaded via CRAN. The function ConPwrExp contains the formulae for the exponential model without any cure fraction while the functions for the non-mixture models are ConPwrNonMixExp (exponential survival), ConPwrNonMixWei (Weibull-type survival) and ConPwrNonMixGamma (Gamma-type survival), respectively. A function for the comparison of these four models on the basis of Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) [6] is also included (CompSurvMod). Finally, conditional power according to Andersen (ConPwrExpAndersen) [2] can be calculated which is also based on an exponential model. Output comprises a summary of survival data of the interim analysis, AICs, parameter estimates, and estimates for the conditional power for the chosen model. Plots of the Kaplan-Meier curves and estimated parametric survival curves are provided. Further details and explanation of package parameters are presented in Table 1 and are available via the help pages of CP.

Description of parameters of the R package CP.

| Parameter | Description | Default |

|---|---|---|

| data | Data frame which consists of at least three columns with the group in the first, survival status in the second and event time in the third column | |

| cont.time | Trial duration after interim analysis | |

| new.pat | two-dimensional vector which consists of numbers of new patients being recruited at each time unit and corresponding study arm | (0, 0) |

| theta.0 | Clinically relevant difference assumed for initial power planning | 1 |

| alpha | Significance level for conditional power calculations | 0.05 |

| disp.data | Logical value indicating whether all results of calculations should be displayed | FALSE |

| plot.km | Logical value indicating whether Kaplan-Meier curves and estimated survival curves assuming the exponential model should be plotted | FALSE |

4.2 Clinical example

We applied our methods to an interim analysis of the highCHOEP trial of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL) [7]. The question to be answered by this trial is whether there is a difference in survival between patients treated with either standard dosage chemotherapy (CHOEP) or dose-intensified chemotherapy (highCHOEP). Patients were between 18 and 60 years old and randomly received one of the above mentioned therapies as first-line treatment. At time of interim analysis, a total of 233 (CHOEP: 118, highCHOEP: 115) patients were analysed, revealing 69 (CHOEP: 33, highCHOEP: 36) death events and an aggregated observation time of 4306 (CHOEP: 2191, highCHOEP: 2115) months (see also Table 2).

Data used for interim analysis: CHOEP is the standard-dose chemotherapy, highCHOEP is the experimental arm with dose-escalated therapy.

| CHOEP | highCHOEP | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 118 | 115 | 233 |

| Deaths | 33 | 36 | 69 |

| Censored | 85 | 79 | 164 |

| Person months | 2,191 | 2,115 | 4,306 |

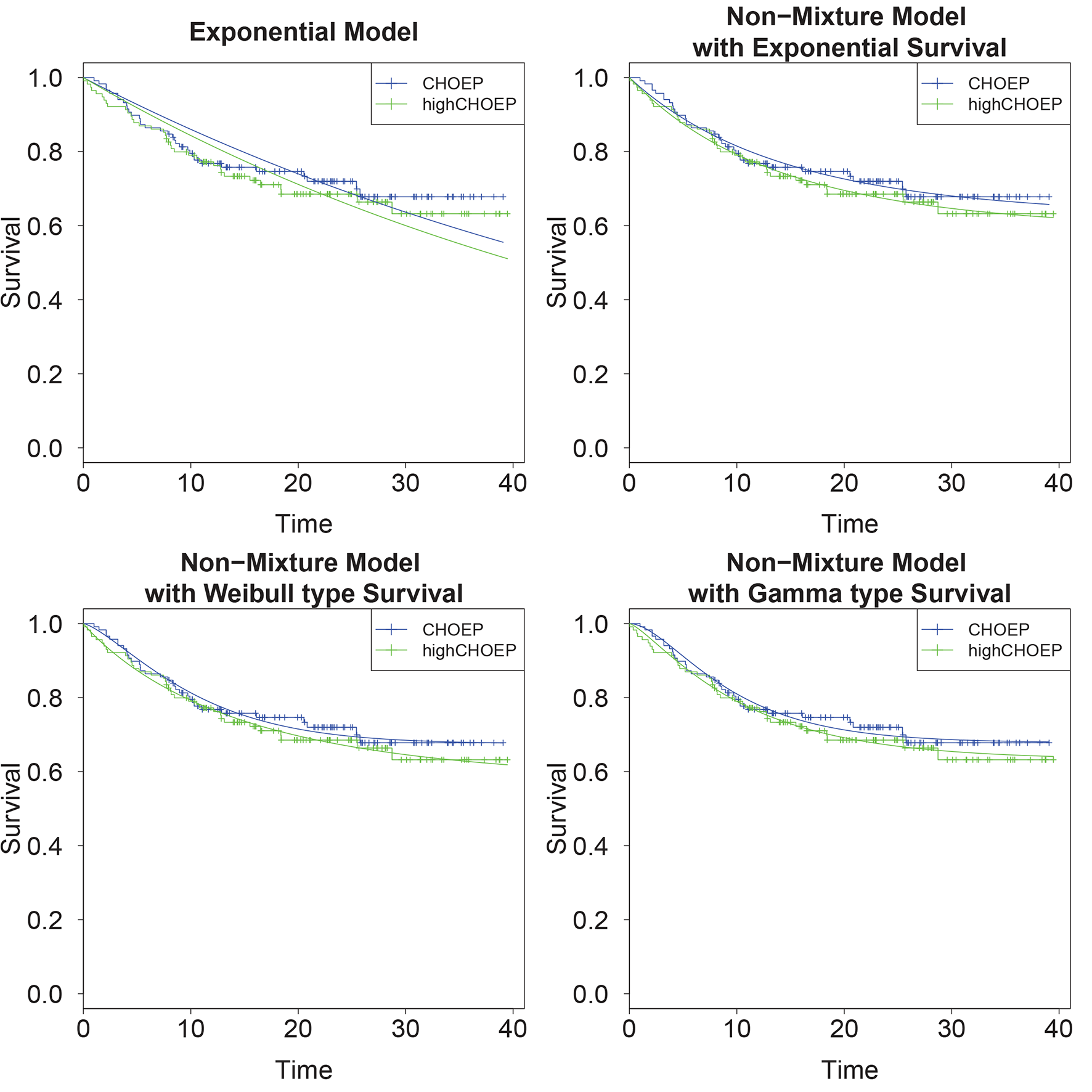

The initial study was planned under an exponential survival model without cure fractions. A hazard ratio of 0.653 was assumed to be clinically relevant. We calculate conditional power for a total sample size of 389 patients assuming an accrual rate of 5.5 patients per month and group resulting in a final analysis after 14.2 months.

The function CompSurvMod of our R-package CP can now be used to calculate the conditional power for each of the models. Note that the hazard ratio translates into a ratio of

Comparison of four models: We present AICs, sums of AICs of both arms, likelihoods, parameter estimates and future person months for each model. As can be seen from the AIC values, all non-mixture models clearly fit the data better than the exponential model. The non-mixture Weibull model performed the best.

| Model | CHOEP | highCHOEP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential | Likelihood | ||

| AIC | 344.9271 | 367.3015 | |

| 0.0151 | 0.0170 | ||

| 1,603 | 1,508 | ||

| Non-mixture-exponential | Likelihood | ||

| AIC | 340.7452 | 362.1870 | |

| 0.0577 | 0.0577 | ||

| 0.6267 | 0.5883 | ||

| 1,553 | 1,455 | ||

| Non-mixture-Weibull | Likelihood | ||

| AIC | 338.9027 | 363.0168 | |

| 0.0480 | 0.0480 | ||

| 1.1482 | 1.1482 | ||

| 0.6569 | 0.6207 | ||

| 1,555 | 1,455 | ||

| Non-mixture-Gamma | Likelihood | ||

| AIC | 336.9673 | 368.9456 | |

| 1.6495 | 1.6495 | ||

| 0.1404 | 0.1404 | ||

| 0.6721 | 0.6374 | ||

| 1,554 | 1,455 |

As one can see in Table 3, at time of interim analysis the estimated hazard ratios

Comparison of parametric models and survival data: While the simple exponential model does not fit the data very well, the non-mixture models result in reasonable fits.

Conditional power functions: We present conditional power estimates in dependence on the true effect size for each of the models.

5 Discussion

5.1 Motivation of the work

Large clinical trials with survival endpoints are often time-consuming and costly. Therefore, interim analyses are common practice. If estimated effect size at time of interim analysis is far below the clinical expectation, conditional power might be a useful aid to evaluate futility of further recruitment which can result in premature termination of the trial. In case of a significant proportion of patients never experiencing an event, simple exponential survival models as proposed by Andersen [2] do not adequately describe the data. In the present paper, we derive conditional power formulae for three non-mixture models assuming cure fractions, namely those of exponential, Weibull, or Gamma type. We restricted our considerations to comparisons of two study arms and assume proportional hazards throughout the paper. Conditional power functions were implemented in an R package and are applied to a clinical data set.

5.2 Modelling Survival Data with Cure Fractions

There are three common types of modelling survival with cure fractions: The parametric, the semi-parametric, and the non-parametric approach, each of them having its own advantages and disadvantages [8]. Since the parametric approach offers a convenient way of testing proportional hazard assumptions and applying maximum likelihood methods for estimation purposes, this kind of modelling is chosen here. Asymptotic normality and unbiasedness of estimates in combination with the delta method allowed us to derive asymptotic distributions of the test statistic considered, which in our case, is the logarithm of the estimator of the hazard ratio.

Fitting piecewise exponential models could be an interesting alternative since it covers both cases, with and without cure fraction. It might also be appropriate for situations for which different event mechanisms could be expected, e.g. during and after an intense therapy. However, we believe that there are also disadvantages to this approach: First, the proportional hazard assumption is less obvious for this setting, especially if there are different event mechanisms to be considered. Without this assumption, the test statistic used in this paper is time dependent complicating all conditional power considerations. Second, the intervals of constant hazards need to be chosen and need to be identical for the treatment arms. This increases the number of free parameters to be determined or requires additional assumptions. Finally, conditional power relies on extrapolation of hazards. Considering a model of piece-wise constant hazards requires assumptions regarding the future of the piecewise behavior. Estimation of hazard ratios differ from exponential to non-mixture models. However, the relevant test statistic is the same. A problem could arise for non-mixture models if the regularity conditions required for asymptotic properties of maximum likelihood estimators are violated. This could occur due to the usage of quasi-probability density functions, i.e. survival functions bounded away from zero. Here, these regularity conditions are fulfilled (proof not shown).

Another approach of modelling survival is provided by the so-called mixture models. These models often give results very similar to those of the non-mixture models [9]. Further details can be found in Boag [10], Berkson and Gage [11], Sposto and Sather [12], and Sposto [13]. A completely different approach to estimating conditional power is via Bayesian methodology. This approach circumvents the issue of asymptotics, is often easier to calculate, and is directly interpretable. However, it faces the problem of specifying appropriate priors [14, 15].

5.3 Proportional Hazard Assumption

We assumed proportional hazards of the two study arms to be compared. In this sense, the non-mixture models as well as the exponential model are related to the Cox model with specified baseline hazard [16]; see Section 2.1 for the exponential model, eq. (5) for the non-mixture model with exponential survival, and Remark 3 for the non-mixture models with Weibull-type survival and Gamma-type survival. For all non-mixture models, proportional hazards imply that the hazard ratio equals the ratio of

5.4 Practical Application

We applied our formulae to a data set of a clinical trial for which an interim analysis was performed. We observed considerable differences between power estimates based on a simple exponential model and our non-mixture models. The exponential model clearly did not fit the data well and resulted in an over-optimistic estimate of the conditional power. In contrast, differences between the non-mixture models were small. In general, non-mixture Weibull or non-mixture Gamma models offer a larger flexibility in modelling survival curves compared to the non-mixture exponential model. In practice, we expect larger differences between the exponential, the non-mixture exponential, and the non-mixture Weibull/Gamma models, while the difference between the non-mixture Weibull and the non-mixture Gamma model might be without practical relevance. We demonstrated that AIC can be used to decide which of the parametric models fits the data best. The analysis plan of clinical trials is usually prescribed in the study protocol. Therefore, we recommend the choice of an appropriate parametric model in the planning phase of a clinical trial. This could be identified e.g. on the basis of available historical data observed under the standard treatment. Here, AIC can be an aid for predetermination of a suitable survival model.

5.5 Aspects of Study Design

Our method allows to quantify the difference in power between the exponential and the non-mixture models. Furthermore, our formulae can be used to calculate sample sizes if the shape of the standard arm is known and a relevant hazard-ratio is specified. For conditional power analysis, we assumed that the time point of final analysis is fixed. However, event-driven designs are frequently used alternatives. These can be addressed with our formulae using the hazard functions estimated at the time point of interim analysis. The time point of final analysis is calculated on the basis of these hazards. Typically, this results in different time points for final analysis for different parametric models. E.g. for our example, final analysis was planned for 14.2 months after interim analysis. Alternatively, assuming an event-driven design, 108 events are required to achieve a power of 80%. Under the non-mixture exponential model, this is achieved at 15.2 months after interim analysis resulting in a conditional power of 19.4% (formerly 18.6%). For the exponential model, the time point of final analysis is 18.0 months after interim analysis resulting in a power of 57.0% (formerly 39.2%). Hence, differences in conditional power between models could even be larger for an event-driven design due to shifts in timing of the final analysis. However, this does not hold in general since the exponential model “generates” less events in the early phase but more events in the later phase compared to the non-mixture exponential model. We like to mention here that event-driven designs have the disadvantage that the required number of events might be unachievable if survival fractions or losses to follow-up are underestimated.

5.6 Non-inferiority Trials

The theory and methods proposed in this paper refer to superiority trials. Another important field of application might be non-inferiority trials. We plan to generalise our methods to this situation in the future. In contrast to superiority trials, a clinically relevant non-inferiority margin needs to be defined prior to sample size calculation. As a consequence, definition of test statistics, hypotheses, and derivations of conditional power formulae are more complex because of a composite null hypothesis. For this situation, the (conditional) power depends on both, the non-inferiority margin

5.7 Practical Interpretation of Conditional Power Estimates

When interpreting conditional power, one needs to keep in mind the following: Low conditional power indicates low chance to achieve a significant result at the end of the study. This suggests that termination of the study may be warranted. When the alternative is superior to the standard arm, this would result in high power. However, this does not necessarily imply that the trial should be continued. If the alternative is already significant at time of interim analysis (e.g. applying alpha spending), the trial must be terminated due to ethical reasons.

We like to remark that premature termination of clinical trials due to futility is a complex and serious issue. Conditional power is only one particular indicator which can be used. Confidence intervals of the observed effect sizes – here, the observed hazard ratio – is another measure to decide whether the originally postulated hazard ratio is realistic or if the trial should be stopped for futility. Defining strict boundaries for study termination is difficult for both methods as it depends on time and frequency of interim analyses. Moreover, there are several non-statistical aspects which have to be considered: Premature termination of the study can be decided for the above mentioned ethical reasons or if other treatments become standard. Practical reasons could be an over-estimated recruitment rate or an under-estimated loss to follow-up. Economic aspects could also be relevant, e.g. expensive experimental treatments showing low benefit could more likely be discarded. Stopping for futility is often a mixture of statistical methods and other aspects. In particular, for our clinical example, the major reason for stopping the trial was not the reduced conditional power at interim analysis but the fact that treating patients without the novel drug Rituximab was considered ethically not acceptable. However, we believe that in general conditional power is a useful method to support decision-making in clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

This publication is supported by LIFE – Leipzig Research Center for Civilization Diseases, Leipzig University. This project was funded by means of the European Social Fund and the Free State of Saxony. We thank the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL) directed by Prof. Dr. Michael Pfreundschuh very much for providing data of the highCHOEP trial. We thank our colleague Dr. Peter Ahnert very much for language polishing. We also thank the editor and the reviewers very much for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the paper.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Appendix A: Theorems

Theorem 1

Proof.

Consider the test statistic

The asymptotic normality of the maximum likelihood estimators (Greene [17], p. 478/479) gives

with

With the delta method (Serfling [18], p. 122) applied to the logarithm one obtains

With

Theorem 2.

It holds that

given

Proof.

The proof of Theorem 2 is similar to that of Theorem 1. The main difference here is that one has to consider conditional probabilities, means and variances. Let

which is asymptotically normal due to the asymptotic normality of the maximum likelihood estimators (Greene [17], p. 478/479) and the delta method (Serfling [18], p. 122). For the correct centering one has to calculate the (asymptotic) conditional expected value of the test statistic. Therefore, one has

by the delta method (Serfling [18], p. 122). Furthermore, with

With

Theorem 3.

Proof.

Maximum likelihood estimates for the rate parameter and the cure fraction are

and

respectively (see 2 in Section B of the Appendix).

Due to the same procedure as in the proof of Theorem 1 – here, considering the modified hazard ratio

Using

Theorem 4.

It holds that

with

given

Proof.

The proof of Theorem 4 is omitted because it is similar to the proof of Theorem 3, taking into account Theorem 2. □

Appendix B: Auxiliary results

Lemma 1.

Within the non-mixture exponential model with rate parameter

Proof.

For deriving the hazard function, the probability density function and the survival function of the non-mixture exponential model are required. For the survival function

Division by

Lemma 2

The maximum likelihood estimators for the rate parameter

and

Proof.

In the case of independent observations under consideration of censoring, the likelihood function

with

Considering the score

and

yields the desired formula of the estimators when setting the score to zero and substituting

Remark 1.

Maximum likelihood estimates within the non-mixture model with Weibull type survival are

Remark 2.

Applying the maximum likelihood method, the following estimators are derived within the non-mixture model with Gamma type survival:

Remark 3.

When calculating the hazard functions

Appendix C: Non-mixture models

Appendix C.1 Accuracy of proportional hazard assumption

For visualisation of differences in estimating the survival curves with and without assuming proportional hazards, we provide Figure 6 in case of the non-mixture exponential model.

Comparison of fitted survival curves of the non-mixture exponential model. Left: Parameters are estimated without proportional hazard assumption (AIC = 702.9311). Right: Parameters are estimated with proportional hazard assumption

Appendix C.2: The Weibull-type survival: conditional power formula

We consider the hypotheses

with

and

Appendix C.3: The Gamma-type survival: conditional power formula

The hypotheses are as usual,

with

and

References

1. Lambert PC. Modeling of the cure fraction in survival studies. Stata J. 2007;7:351–375.10.1177/1536867X0700700304Search in Google Scholar

2. Andersen PK. Conditional power calculations as an aid in the decision whether to continue a clinical trial. Control Clin Trials. 1987;8:67–74.10.1016/0197-2456(87)90027-4Search in Google Scholar

3. Martinez EZ, Achcar JA, Jácome AA, Santos JS. Mixture and non-mixture cure fraction models based on the generalized modified Weibull distribution with an application to gastric cancer data. Compute Methods Programs Biomed. 2013;112:343–355.10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.07.021Search in Google Scholar

4. Tsodikov AD, Ibrahim JG, Yakovlev AY. Estimating cure rates from survival data: an alternative to two-component mixture models. J Am Stat Assoc. 2003;98:1063–1078.10.1198/01622145030000001007Search in Google Scholar

5. Tsodikov A, Loeffler M, Yakovlev A. A cure model with time-changing risk factor: an application to the analysis of secondary Leukaemia. Stat Med. 1998;17:27–40.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980115)17:1<27::AID-SIM720>3.0.CO;2-QSearch in Google Scholar

6. Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automatic Control. 1974;19:716–723.10.1007/978-1-4612-1694-0_16Search in Google Scholar

7. Pfreundschuh M, Zwick C, Zeynalova S, Duehrsen U, Pflueger KH, Vrieling T,et al. Dose-escalated CHOEP for the treatment of young patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: II. Results of the randomized high-CHOEP trial of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Ann Oncol. 2007;19:545–552.10.1093/annonc/mdm514Search in Google Scholar

8. Altman DG, Bland JM. Parametric v non-parametric methods for data analysis. BMJ. 2009;338:a3167.10.1136/bmj.a3167Search in Google Scholar

9. Achcar JA, Coelho-Barros EA, Mazucheli J. Cure fraction models using mixture and non-mixture models. Tatra Mountains Math Publications. 2012;51:1–9.10.2478/v10127-012-0001-4Search in Google Scholar

10. Boag JW. Maximum likelihood estimates of the proportion of patients cured by cancer therapy. J R Stat Soc Ser B Method. 1949;11:15–53.10.1111/j.2517-6161.1949.tb00020.xSearch in Google Scholar

11. Berkson J, Gage RP. Survival curve for cancer patients following treatment. J Am Stat Assoc. 1952;47:501–515.10.1080/01621459.1952.10501187Search in Google Scholar

12. Sposto R, Sather HN. Determining the duration of comparative clinical trials while allowing for cure. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38:683–690.10.1016/0021-9681(85)90022-0Search in Google Scholar

13. Sposto R. Cure model analysis in cancer: an application to data from the children’s cancer group. Stat Med. 2002;21:293–312.10.1002/sim.987Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Ibrahim JG, Chen MH, Sinha D. Bayesian semiparametric models for survival data with a cure fraction. Biometrics. 2001;57:383–388.10.1111/j.0006-341X.2001.00383.xSearch in Google Scholar

15. Yin G, Ibrahim JG. A general class of bayesian survival models with zero and nonzero cure fractions. Biometrics. 2005;61:403–412.10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00329.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1972;34:187–220.10.1007/978-1-4612-4380-9_37Search in Google Scholar

17. Greene WH. Econometric analysis. Upper Saddle River:Prentice Hall, 2003.Search in Google Scholar

18. Serfling RJ. Approximation theorems of mathematical statistics. New York:John Wiley & Sons, 1980.10.1002/9780470316481Search in Google Scholar

19. Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival analysis. Techniques for censored and truncated data. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, 2005.Search in Google Scholar

Supplemental Material

The online version of this article (DOI:ijb-2015-0073) offers supplementary material, available to authorized users.

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Commentary

- Big Data, Small Sample

- Research Articles

- Parameter Estimation of a Two-Colored Urn Model Class

- Combinatorial Mixtures of Multiparameter Distributions: An Application to Bivariate Data

- On the Conditional Power in Survival Time Analysis Considering Cure Fractions

- Comparing Four Methods for Estimating Tree-Based Treatment Regimes

- On Stratified Adjusted Tests by Binomial Trials

- Improvement Screening for Ultra-High Dimensional Data with Censored Survival Outcomes and Varying Coefficients

- Bayesian Variable Selection Methods for Matched Case-Control Studies

- Testing Equality of Treatments under an Incomplete Block Crossover Design with Ordinal Responses

- Empirical Likelihood in Nonignorable Covariate-Missing Data Problems

- A Quantitative Concordance Measure for Comparing and Combining Treatment Selection Markers

- Median Analysis of Repeated Measures Associated with Recurrent Events in Presence of Terminal Event

- A Theorem at the Core of Colliding Bias

- Group Tests for High-dimensional Failure Time Data with the Additive Hazards Models

- Characterizing Highly Benefited Patients in Randomized Clinical Trials

Articles in the same Issue

- Commentary

- Big Data, Small Sample

- Research Articles

- Parameter Estimation of a Two-Colored Urn Model Class

- Combinatorial Mixtures of Multiparameter Distributions: An Application to Bivariate Data

- On the Conditional Power in Survival Time Analysis Considering Cure Fractions

- Comparing Four Methods for Estimating Tree-Based Treatment Regimes

- On Stratified Adjusted Tests by Binomial Trials

- Improvement Screening for Ultra-High Dimensional Data with Censored Survival Outcomes and Varying Coefficients

- Bayesian Variable Selection Methods for Matched Case-Control Studies

- Testing Equality of Treatments under an Incomplete Block Crossover Design with Ordinal Responses

- Empirical Likelihood in Nonignorable Covariate-Missing Data Problems

- A Quantitative Concordance Measure for Comparing and Combining Treatment Selection Markers

- Median Analysis of Repeated Measures Associated with Recurrent Events in Presence of Terminal Event

- A Theorem at the Core of Colliding Bias

- Group Tests for High-dimensional Failure Time Data with the Additive Hazards Models

- Characterizing Highly Benefited Patients in Randomized Clinical Trials