Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence, knowledge, and practices related to non-prescribed weight loss supplements among university students, and to identify reported side effects to support targeted health education.

Methods

An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted among students at a public Egyptian university using a self-administered bilingual (English and Arabic) questionnaire. A total of 437 male and female undergraduates from all academic years were selected through multistage random sampling technique. Sample size was calculated via OpenEpi (v24.1), and data were analyzed using SPSS (v25).

Results

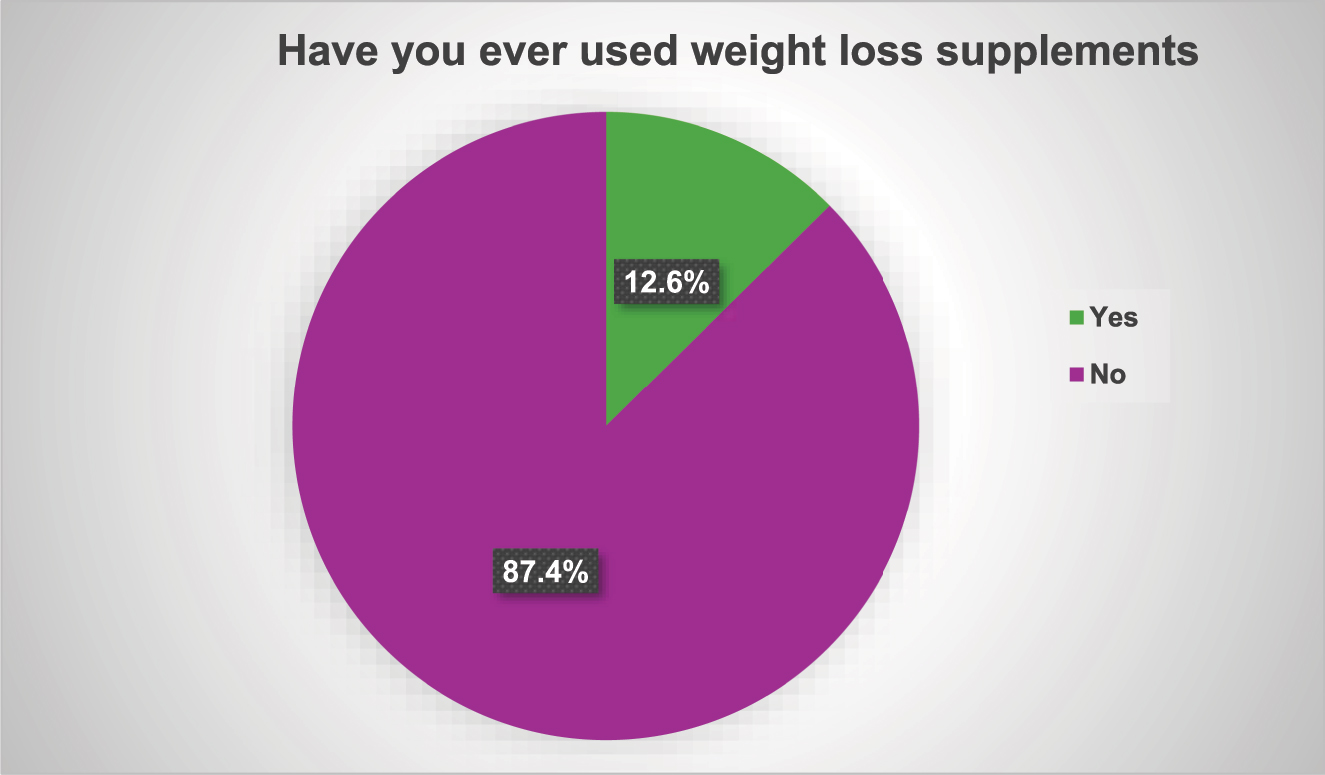

The prevalence of weight loss supplement use among students was 12.6 %. Among users, 43.6 % self-prescribed these products, and 80 % were females. Social media and family recommendations were key influencing sources for nearly 60 % of users. Moreover, 40 % of users reported experiencing side effects. The mean knowledge score among all participants was 3.15 ± 0.89 out of 4.

Conclusions

The findings indicate that 12.6 % of university students use weight loss supplements, and 43.6 % of them consume these products without medical consultation. The gap between knowledge and practice highlights the need for targeted awareness campaigns and stricter regulation.

Introduction

Obesity is a growing global health concern, with projections indicating that 24 % of the world’s population will be obese by 2030, as noted by Dini and Mancusi [1]. Defined by the WHO as “excessive fat deposits that can impair health,” obesity contributes to approximately 4.7 million premature deaths annually and is strongly linked to non-communicable diseases such as cancer, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease [2], 3]. Beyond physical health, obesity is associated with stigma, discrimination, and reduced overall well-being, as highlighted by Sánchez et al. [4].

Egypt ranks among the top 20 countries worldwide in obesity prevalence, with adult obesity rates increasing from 36 % in 2017 to nearly 40 % in 2019, according to national reports from the 100 Million Health Initiative (2018–2019). The healthcare burden is also significant, with obesity-related disease costs estimated at 62 billion EGP [2].

While lifestyle interventions remain foundational, the rise in obesity has fueled interest in pharmacological treatments, including dietary supplements [5]. These products are often marketed as quick and easy solutions, bypassing the effort required for sustainable behavioral change. Although clinical guidelines recommend anti-obesity drugs for specific cases, many over-the-counter supplements lack regulation, raising concerns over their safety, side effects, and potential drug interactions [6], 7].

The use of non-prescription weight loss products is on the rise, particularly among young adults, influenced by social media and peer recommendations – sources that may not be reliable, as Colangeli et al. point out [8]. This trend emphasizes the need to evaluate young people’s knowledge and practices surrounding these supplements to support appropriate health education and regulation.

Subjects and methods

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted among undergraduate students at Beni-Suef University, Egypt, from various faculties. These faculties were categorized into three groups: (1) Medical and Health Sciences, (2) Humanities, Behavioral, and Social Sciences, and (3) Engineering, Natural, and Computer Sciences.

Sampling technique and population

A multistage random sampling technique was used to select representative faculties from medical, engineering, and humanities disciplines. A total of 437 students were enrolled to ensure study power. Inclusion criteria included students of both genders and all academic years from the selected faculties, regardless of their use of weight loss supplements. Postgraduate students and those outside the selected faculties were excluded.

Study tool

Data were collected using a pre-designed, primarily structured, self-administered questionnaire – with a few open-ended questions – was adapted based on Jairoun et al. [9]. It was developed in both English and Arabic languages and pilot-tested before data collection.

The questionnaire consisted of four main sections.

Section I: Assessed sociodemographic data such as age, gender, residence, governorate, college, parental education, weight, height, chronic disease status, and participants’ weight management strategies.

Section II: Evaluated participants’ knowledge about weight loss supplements, including potential health hazards, product adulteration, the need for accurate information, and whether they perceive adulterated slimming products as a national health issue. This section consisted of four questions, each answered with “Yes/No.” Responses were scored as Yes=1 and No=0, with higher scores indicating better knowledge.

Section III: Explored participants’ practices regarding supplement use, including physician consultation, reading drug labels, checking product registration, the influence of social media and relatives, duration of use, and whether they recommend supplements to others. This section consisted of 10 questions. The first nine questions were answered using a Yes/No format, scored as Yes=1 and No=0. Question 10 assessed the duration of supplement use, with responses categorized as (1) one month, (2) three months, (3) six months, (4) one year, and (5) more than one year. Each category was scored from 1 to 5 accordingly. The maximum possible score for this section was 14, with higher scores indicating a greater number of reported practices related to supplement use.

Section IV: Identified self-reported side effects experienced by users, such as flushing, nausea, heartburn, skin or gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue. This section consisted of 8 questions, each answered with Yes/No. Responses were scored as Yes=1 and No=0, with higher scores reflecting a greater number of side effects experienced.

Pilot study

A pilot study was conducted on 30 students to assess clarity, validity, and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.81). No modifications were required, and pilot data were included in the final analysis.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected over an eight-month period starting in October 2023, following ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee. Participants were recruited through two main approaches: in-person visits to various university faculties and online distribution of Google Forms via WhatsApp. Participation was entirely voluntary and preceded by informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics summarized qualitative and quantitative variables. Chi-square, Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis, and Spearman’s correlation tests were used as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression identified predictors of supplement use. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 437 university students participated in the study. The mean age was 20.78 ± 1.74 years, with females representing 68.9 % of the participants. Most students were from the original governorate where the study was conducted (73 %) and lived in rural areas (55.8 %). Medical and health sciences students comprised 61.1 % of the sample, and the majority were in their 2nd academic year (45.5 %) (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | No. (437) | Percent, % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 20.78 ± 1.74 | |

| Gender Males Females |

136 301 |

31.1 68.9 |

| Governorate Beni-Suef Others |

319 118 |

73 27 |

| Residence Urban Rural |

193 244 |

44.2 55.8 |

| College Medical and health sciences Humanities, behavioral, and social sciences Engineering, natural, and computer sciences |

267 75 95 |

61.1 17.2 21.7 |

| Academic year 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th |

73 199 98 38 29 |

16.7 45.5 22.4 8.7 6.7 |

| Father education Illiterate Primary school degree Preparatory school degree Secondary school degree University degree Postgraduate degree |

31 13 22 137 211 23 |

7.1 3 5 31.4 48.3 5.2 |

| Mother education Illiterate Primary school degree Preparatory school degree Secondary school degree University degree Postgraduate degree |

70 20 23 160 153 11 |

16 4.6 5.3 36.6 35 2.5 |

The average weight of participants was 66.78 ± 14.34 kg, height 164.09 ± 9.66 cm, and BMI 24.79 ± 4.72 kg/m2. Only 5.7 % had a chronic disease. Regarding weight-related intentions, 36.8 % aimed to lose weight, while 14.5 % reported no effort toward weight change (Table 2).

medical and body weight status of the participants.

| Medical status | No. (437) | Percent, % |

|---|---|---|

| Weight, kg (mean ± SD) |

66.78 ± 14.34 |

|

| Height, cm (mean ± SD) |

164.09 ± 9.66 |

|

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) |

24.79 ± 4.72 |

|

| Having a chronic disease Yes No |

25 412 |

5.7 94.3 |

| Chronic disease (25 cases) Diabetes mellitus High blood pressure Gastrointestinal tract chronic disease Hypothyroidism Anemia Insulin resistance Asthma Others |

3 4 4 2 2 2 3 5 |

12 16 16 8 8 8 12 20 |

| Weight strategy Lose weight Gain weight Stay at the same weight Not trying to do anything |

161 111 102 63 |

36.8 25.4 23.3 14.5 |

-

Other chronic diseases mentioned by the participants include (Rheumatic fever\multiple sclerosis\skin allergy\obsessive compulsive disorder\planter fasciitis).

In terms of overall practices, a small proportion of participants (12.6 %) reported prior use of weight loss supplements (Figure 1). Among users, only 56.4 % consulted a physician before using weight loss supplements, meaning that 43.6 % used them without medical supervision. While the majority demonstrated responsible behaviors – 71 % reported reading the product instructions, and 67.3 % ensured that the supplements were registered with national regulatory authorities, only 36.4 % checked official circulars for warnings about adulterated products.

Using weight loss supplements among student participants.

With regard to other aspects of practice, 27.3 % of users recommended dietary supplements to others, raising concerns about peer-to-peer promotion without professional guidance. Notably, 40 % of users reported experiencing side effects, underscoring the health risks associated with unsupervised supplement use. The most frequently reported symptoms were headache, dizziness and fatigue; palpitations or shortness of breath; and gastrointestinal disturbances. Approximately 60 % of all participants reported social media and recommendations from relatives as key factors influencing supplement use (Table 3).

Association between student participants’ practices and their prior use of weight loss supplements.

| Practice items | Prior use of weight loss supplements | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (NO. =55) | No (NO. =382) | ||

| Do you consult a physician before using weight loss/slimming supplement products? Yes No |

31 (56.4 %) 24 (43.6 %) |

280 (74 %) 102 (26 %) |

0.015 * |

| Do you read the instructions on the drug label? Yes No |

39 (71 %) 16 (29 %) |

265 (69.4 %) 117 (30.6 %) |

0.817 |

| Do you ensure that the weight loss supplement products are registered in the country by the concerned regulatory authority? Yes No |

37 (67.3 %) 18 (32.7 %) |

257 (67.5 %) 124 (32.5 %) |

0.979 |

| Do you check circulars that are issued by the regulatory authorities for adulterated weight loss/slimming supplement products? Yes No |

20 (36.4 %) 35 (63.6 %) |

201 (52.6 %) 181 (47.4 %) |

0.024 * |

| Do you recommend dietary supplements to others? Yes No |

15 (27.3 %) 40 (72.7 %) |

58 (15.2 %) 324 (84.8 %) |

0.025 * |

| Have you ever experienced any side effects related to weight loss/slimming supplements use? Yes No |

22 (40 %) 33 (60 %) |

15 (4.2 %) 340 (95.8 %) |

<0.001 * |

| Does social media have an influence on your decision to use supplements? Yes No |

39 (70.9 %) 16 (29.1 %) |

208 (57.6 %) 153 (42.4 %) |

0.062 |

| Do your relatives have an influence on your decision to use supplements? Yes No |

26 (47.3 %) 29 (52.7 %) |

128 (36 %) 229 (64 %) |

0.103 |

-

*The bold values indicate statistically significant results (p<0.05).

In terms of knowledge, among all participants (n=437), 70.3 % believed it was necessary to seek more information before using weight loss supplements. Additionally, 62.2 % were aware of potential hazards associated with their use. A large majority (83.5 %) recognized the possibility of adulteration with prescription drugs or undeclared chemicals, and 92.2 % agreed that adulterated slimming products pose a national health problem in Egypt (Table 4). A significantly higher proportion of supplement users (81.8 %) acknowledged the importance of seeking additional information prior to use, compared to 68.6 % of non-users who shared the same view (p=0.045). However, the remaining knowledge-related items showed no statistically significant differences.

Student participants’ knowledge regarding weight loss supplements.

| Knowledge items | Number (437) | Percent, % |

|---|---|---|

| Is it necessary to obtain more information about weight loss supplements? Yes No |

307 130 |

70.3 29.7 |

| Are you aware of any hazards that might be associated with the use of weight loss supplement products? Yes No |

272 165 |

62.2 37.8 |

| Are you aware that weight loss products may be adulterated with another prescription drug or undeclared chemicals? Yes No |

365 72 |

83.5 16.5 |

| Adulterated slimming supplements are a national health problem in Egypt Yes No |

403 34 |

92.2 7.8 |

Regarding the factors influencing knowledge and practice scores, the mean knowledge and practice scores among all participants were 3.15 ± 0.89 and 5.75 ± 2.24, respectively.

Statistically significant differences in knowledge scores were observed across college types (p=0.008) and academic years (p=0.005). Students enrolled in medical and health sciences faculties demonstrated higher knowledge levels compared to those in engineering, natural, and computer sciences. Moreover, second- and fifth-year students showed significantly greater knowledge scores than first-year students. No significant differences were found based on gender, residence, governorate, parental education, chronic disease status, or weight management strategy (p>0.05 for all) (Table 5).

Association between sociodemographic characteristics and knowledge and practice scores.

| Knowledge score | Practice score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | p-Value | Test of significance | Mean ± SD | p-Value | Test of significance | |

| Gender Males Females |

2.98 ± 0.95 3.12 ± 0.90 |

0.151 |

Mann-Whitney U test |

5.14 ± 2.23 5.95 ± 2.21 |

0.040 * |

Mann-Whitney U test |

| Governorate Beni-Suef Others |

3.07 ± 0.91 3.09 ± 0.93 |

0.838 |

Mann-Whitney U test |

5.73 ± 2.30 5.80 ± 2.04 |

0.658 |

Mann-Whitney U test |

| Residence Urban Rural |

3.01 ± 0.93 3.13 ± 0.90 |

0.163 |

Mann-Whitney U test |

5.89 ± 2.13 5.65 ± 2.31 |

0.487 |

Mann-Whitney U test |

College

|

3.17 ± 0.88c 3.02 ± 0.92 2.85 ± 0.96a |

0.008 * |

Kruskal-Wallis test Followed by bonferroni post-hoc test |

5.76 ± 2.26 6.00 ± 2.25 5.43 ± 2.16 |

0.463 |

Kruskal-Wallis test |

| Academic year 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th |

2.72 ± 1.033, 4, 5 3.20 ± 0.83 3.04 ± 0.971 3.07 ± 0.811 3.27 ± 0.921 |

0.005 * |

Kruskal-Wallis test Followed by bonferroni post-hoc test |

5.62 ± 2.55 5.84 ± 2.24 5.62 ± 1.99 5.50 ± 2.19 6.00 ± 2.31 |

0.805 |

Kruskal-Wallis test |

Father education

|

3.09 ± 0.90 2.76 ± 1.01 3.09 ± 0.86 3.10 ± 0.87 3.06 ± 0.95 3.26 ± 0.91 |

0.735 |

Kruskal-Wallis test |

5.31 ± 1.96 5.16 ± 2.40 6.00 ± 2.44 5.73 ± 2.31 5.68 ± 2.24 7.00 ± 1.81 |

0.222 |

Kruskal-Wallis test |

Mother education

|

3.15 ± 0.79 3.35 ± 0.74 3.00 ± 1.04 3.05 ± 0.94 3.06 ± 0.94 2.90 ± 1.04 |

0.833 |

Kruskal-Wallis test |

5.88 ± 2.38 5.53 ± 1.76 4.07 ± 1.63 5.98 ± 2.39 5.68 ± 2.07 6.16 ± 1.47 |

0.056 |

Kruskal-Wallis test |

Chronic disease status

|

5.65 ± 2.31 3.08 ± 0.91 |

0.636 |

Mann-Whitney U test |

5.68 ± 2.24 5.75 ± 2.24 |

0.717 |

Mann-Whitney U test |

Weight strategy

|

3.06 ± 0.86 3.02 ± 1.08 3.19 ± 0.75 3.04 ± 0.99 |

0.778 |

Kruskal-Wallis test |

5.90 ± 2.20IV 5.65 ± 2.43IV 6.16 ± 2.17IV 4.64 ± 1.81I, II, III |

0.015 * |

Kruskal-Wallis test Followed by bonferroni post-hoc test |

-

Notes: 1,2,3,4,5Significant difference compared with 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th year students, respectively. a,cSignificant difference compared with medical and engineering colleges, respectively. I,II,III,IVSignificant difference compared with students aiming to lose weight, gain weight, maintain weight, and not trying to change weight, respectively. *Statistically significant (p<0.05).

As for practice scores, females reported significantly higher scores than males (p=0.040). A significant difference was also found in relation to weight management strategies (p=0.015), with those not attempting to change their weight reporting lower practice scores than participants trying to lose, gain, or maintain weight. No significant differences in practice scores were observed based on college type, academic year, residence, governorate, parental education, or chronic disease status (Table 5).

Logistic regression analysis identified three significant predictors of using weight loss supplements: attempting to lose weight, not consulting a physician before use, and having previously experienced side effects (p<0.05). Other examined factors were not statistically significant (Table 6).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for prediction of factors associated with using weight loss drugs.

| Independent variables | p-Value | OR | 95 % CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight strategy | Lose weight | 0.013 * | 6.628 | 1.482–29.634 |

| Gain weight | 0.264 | 2.483 | 0.503–12.254 | |

| Stay at the same weight | 0.452 | 0.765 | 0.115–5.099 | |

| Is it necessary to obtain more information about weight loss supplements? | No | 0.367 | 0.691 | 0.310–1.543 |

| Do you consult a physician before using weight loss/slimming supplement products? | No | 0.024 * | 2.332 | 1.119–4.895 |

| Do you check circulars that are issued by the regulatory authorities for adulterated weight loss/slimming supplement products? | No | 0.084 | 1.928 | 0.915–4.062 |

| Do you recommend dietary supplements to others? | No | 0.190 | 0.583 | 0260–1.307 |

| Have you ever experienced any side effects related to weight loss/slimming supplements use? | No | <0.001 * | 0.060 | 0.24–0.149 |

-

*The bold values indicate statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Discussion

Numerous studies have been carried out among university students in Egypt. However, no study has been conducted to assess the knowledge and practices regarding non-prescription weight loss supplement use in this population. So, the current study aimed to determine the prevalence of slimming dietary supplement use among students of Beni-Suef University, Egypt.

The findings showed that 12.6 % of participants had used weight loss supplements. This prevalence is slightly higher than global estimates reported by Hall et al. [10], where the average use was 8.9 % in the general population, but much lower than figures reported in neighboring countries like the UAE, where nearly 39 % of university students reported using [9]. These differences could reflect variations in cultural norms, health awareness, access to supplements, or social pressures related to body image and beauty standards.

Interestingly, despite the relatively low overall usage rate, a concerning pattern emerged regarding the lack of medical supervision. Among users, 43.6 % reported not consulting a physician before starting supplementation. This aligns with global patterns of self-medication, as reported in several studies across different countries [9], 11], 12], but remains problematic considering the well-documented risks of unsupervised use, including adverse reactions and drug interactions. The ease of access to such products without prescriptions may partially explain this behavior and illustrate the importance of stricter regulation and public health interventions.

In terms of safety awareness, only 36.4 % of users reported checking official circulars for adulterated supplements, despite over two-thirds reading instructions and verifying product registration. This indicates that while students may demonstrate basic responsible behaviors, their awareness of deeper regulatory or safety issues remains limited. These findings echo previous studies suggesting that users often underestimate the risks associated with so-called “natural” or over-the-counter supplements [9], 13].

Another important finding was the influence of social factors. Around 60 % of participants reported being influenced by social media and family recommendations when deciding to use supplements. These informal sources of information – while convenient – are not always reliable and may promote unsafe practices. Previous studies have similarly identified social media, friends, and TV as common sources of information about weight loss products among youth [14], 15]. This suggests a need to integrate more credible health messaging into platforms that students frequently engage with.

A particularly noteworthy issue is the reporting of side effects. In this study, 40 % of users experienced at least one side effect, with common symptoms including headache, dizziness, gastrointestinal disturbances, palpitations, and fatigue. These figures are consistent with prior regional findings [16] and reinforce concerns that many weight loss products – even those marketed as herbal or natural – can have significant physiological impacts [7]. Despite experiencing side effects, many participants continued using the supplements, which reflects either a lack of awareness or prioritization of weight loss over health.

Regarding BMI and weight status, users had significantly higher BMI and weight than non-users. Higher BMI individuals are more likely to seek weight loss interventions, including supplements, as expected. The mean BMI among users (28.3 kg/m2) places them in the overweight to obese category, which aligns with previous findings indicating that individuals with excess weight are more likely to adopt non-prescribed weight loss strategies [11], 17].

The findings also revealed gender-based and academic variations. Females were more likely to use supplements and had significantly higher practice scores than males, which is consistent with previous research suggesting that women are more likely to engage in health-related behaviors and to be concerned about body image [18]. Additionally, students in health-related faculties and those in later academic years demonstrated higher knowledge levels, which is understandable given their academic exposure to relevant scientific content.

Despite this, higher knowledge did not always translate into safer practices. Knowledge scores were higher among health science students, but practice scores did not differ substantially by type of college. Similar discrepancies between knowledge and actual practices have been observed in previous studies, suggesting that information alone may be insufficient without behaviorally targeted interventions [19].

Lastly, logistic regression analysis identified three significant predictors of supplement use: actively trying to lose weight, not consulting a physician before use, and experiencing previous side effects. These predictors provide valuable insight for targeted interventions – especially for students attempting weight loss independently, who may need both counseling and education to prevent harmful self-medication.

Overall, this study highlights the need for structured educational campaigns, stronger regulatory enforcement, and active engagement with youth through trustworthy communication channels. As the popularity of weight loss supplements continues to grow – particularly among young adults – university-based health programs may play a key role in promoting informed and safe decision-making.

Conclusions

The study revealed that 12.6 % of university students reported using non-prescription weight loss supplements, with 43.6 % of them doing so without prior medical consultation. Notably, females constituted 80 % of the users. Although many participants demonstrated awareness of the potential health risks associated with supplement use, a considerable proportion continued to consume them without professional guidance. Furthermore, 40 % of users reported experiencing adverse effects, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive awareness and educational interventions targeting safe weight management practices among university students.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their time and cooperation.

-

Research ethics: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Faculty of Medicine, Beni-Suef University Research Ethics Committee (Approval Code: FMBSUREC/03102023/abdalfattah). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional guidelines.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Large Language Models (LLMs), including ChatGPT by OpenAI, were used to support English editing and improve academic phrasing. No part of the content was generated entirely by AI, and all findings and interpretations were authored by the researchers.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Dini, I, Mancusi, A. Weight loss supplements. Molecules 2023;28:5357. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28145357.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Aboulghate, M, Elaghoury, A, Elebrashy, I, Elkafrawy, N, Elshishiney, G, Abul-Magd, E, et al.. The burden of obesity in Egypt. Front Public Health 2021;9:718978. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.718978.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2024. [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.Search in Google Scholar

4. Sánchez, E, Elghazally, NM, El-Sallamy, RM, Ciudin, A, Sánchez-Bao, A, Hashish, MS, et al.. Discrimination and stigma associated with obesity: a comparative study between Spain and Egypt. Obes Facts 2024;17:582–92. https://doi.org/10.1159/000540635.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Pillitteri, JL, Shiffman, S, Rohay, JM, Harkins, AM, Burton, SL, Wadden, TA. Use of dietary supplements for weight loss in the United States: results of a national survey. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:790–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.136.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Tchang, BG, Aras, M, Kumar, RB, Aronne, LJ, et al.. Pharmacologic treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. In: Feingold, KR, Anawalt, B, Boyce, A, editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2024. [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279038/.Search in Google Scholar

7. Alraei, RG. Herbal and dietary supplements for weight loss. Top Clin Nutr 2010;25:136–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/tin.0b013e3181dbb85e.Search in Google Scholar

8. Colangeli, L, Russo, B, Capristo, E, Mariani, S, Tuccinardi, D, Manco, M, et al.. Attitudes, weight stigma and misperceptions of weight loss strategies among patients living with obesity in the Lazio Region, Italy. Front Endocrinol 2024;15:1434360. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1434360.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Jairoun, AA, Al-Hemyari, SS, Saeed, BQ, Shahwan, M, Al-Ani, M, Khattab, MH, et al.. Knowledge, practices and risk awareness regarding non-prescription weight loss supplements among university students in UAE. J Public Health 2023;33:739–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-02046-5.Search in Google Scholar

10. Hall, NY, Pathirannahalage, DMH, Mihalopoulos, C, Austin, SB, Le, L. Global prevalence of adolescent use of nonprescription weight-loss products. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7:e2350940. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.50940.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Blanck, HM, Serdula, MK, Gillespie, C, Galuska, DA, Sharpe, PA, Conway, JM, et al.. Use of nonprescription dietary supplements for weight loss is common among Americans. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107:441–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Xia, Y, Kelton, CM, Guo, JJ, Bian, B, Heaton, PC. Treatment of obesity: pharmacotherapy trends in the United States from 1999 to 2010. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:1721–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21136.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Andrews, KW, Roseland, JM, Gusev, PA, Palachuvattil, J, Dang, PT, Savarala, S, et al.. Analytical ingredient content and variability of adult multivitamin/mineral products: national estimates for the Dietary supplement ingredient database. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:526–39. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.134544.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Tawific, S, Eassa, S, Elhawy, L, El, L. Assessment of weight loss practice among adolescents in lower Egypt governorates. Egypt J Community Med 2020;38:96–106. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejcm.2020.89893.Search in Google Scholar

15. Abdel-Salam, DM, Alruwaili, JM, Alshalan, RA, Alruwaili, TA, Alanazi, SA, Lotfy, AMM. Epidemiological aspects of dietary supplement use among Saudi medical students: a cross-sectional study. Open Publ Health J 2020;13:783–90. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874944502013010783.Search in Google Scholar

16. Alowais, MA, Selim, MAE. Knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding dietary supplements in Saudi Arabia. J Fam Med Prim Care 2019;8:365–72. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_430_18.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Ezzat, S. A study of the use of drugs in the treatment of obesity among adult females. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2012;25:730–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526861211270668.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Dickinson, A, MacKay, D. Health habits and other characteristics of dietary supplement users: a review. Nutr J 2014;13:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-14.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Tan, Y, Liu, D, Yuan, S, Zhou, Y, Zhang, Y. Knowledge level, beliefs, and influencing factors of dietary supplements among Chinese adults. Front Nutr 2024;11:1493504. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1493504.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.