Parental perspectives: a mixed method study on perceived risk, self-efficacy, vaccine response efficacy, and willingness for adolescent HPV vaccination in Puducherry, South India

-

Sreeshma Narayanan PP

, Abinandhan Murugan

, Jayalakshmy Ramakrishnan

, Karthik Rajan Parasuraman Udayakumar

, Ruben Raj L

and Mahalakshmy Thulasingam

Abstract

Background

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women in India. To reduce its incidence, the government is set to roll out a Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for adolescent girls.

Objectives

To find the association between risk perception, self-efficacy, vaccine response efficacy and willingness to vaccinate adolescents (9–18 years) against HPV and to explore factors associated with willingness for vaccination among adolescent girls, their parents and healthcare workers.

Methods

A mixed-method study was conducted among parents of adolescent girls aged 9–18 using multistage simple random sampling in Puducherry. After a brief education session, a self-developed and validated questionnaire was used to assess perceived risk, self-efficacy, vaccine response efficacy and willingness for HPV vaccination. Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests were used for analysis.

Results

Out of 388 participants, majority (78.1 %) had heard of cervical cancer, and 6.2 % were aware of HPV infection. Of the participants, 44.8 % (95 % CI: 39.9–49.8 %) had a high perceived risk, 49 % (95 % CI: 44.0–53.9 %) had low self-efficacy, and 70.9 % (95 % CI: 66.2–75.2 %) believed in high vaccine response efficacy. Additionally, 91.5 % of participants were willing to vaccinate under a universal immunisation schedule, and only 44.1 % from private providers. Participants who were willing to vaccinate had a higher risk perception of HPV infection and cervical cancers, high belief in vaccines and low self-efficacy in their own health (p<0.001) compared to those who were not willing for HPV vaccination.

Introduction

Cervical cancer develops in the cells of the cervix, which is the lower part of the uterus connecting to the vagina and mainly affects individuals aged 30 years and above [1], 2]. It is the fourth most common cancer in women, with the highest incidence and mortality rates observed in sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, and Southeast Asia [3]. According to GLOBOCAN 2020, worldwide cervical cancer accounts for 341,831 (3.3 %) deaths and 604,127 (3.1 %) new cases annually [4], with an age-standardised incidence of 133 cases per million women years and a mortality rate of 72 deaths per million women years. Cervical cancer disproportionately affects younger women; as a result, 20 % of children lose their mothers due to cervical cancer [3]. A total of 194 countries committed to eliminating cervical cancer at the initiative of the World Health Organisation (WHO) [5].

India leads the world in cervical cancer cases, with one out of every four women suffering from cervical cancer being Indian [3], 6]. According to the WHO Cervical Cancer Country Profile 2021, crude cervical cancer incidence is 187 per million and 45,300 deaths every year [6]. The high burden of cervical cancer in the country is attributed to several risk factors, including early marriage and sexual debut, multiple sexual partners, limited access to effective treatments, and low coverage of cervical cancer screening [7].

The primary causative agent is a persistent infection with oncogenic strains of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), particularly types 16 and 18, responsible for nearly 50 % of high-grade precancers [8]. However, it is preventable through effective vaccination and cervical screening programs [9], 10]. The WHO recommends HPV vaccination for girls aged 9–14 years: initially two doses [10], 11], revised to a single-dose vaccination in 2022 [12], 13] – a cost-effective intervention projected to prevent 74 million cervical cancer cases and 62 million deaths globally by 2,120 [14]. Innovative HPV vaccines like Cervarix, Cecolin, Walrinvax, Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervavax 3 target the most common cancer-causing HPV strains, providing a crucial opportunity to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer [15]. Cervavac, developed by the Serum Institute of India, emerges as a promising indigenous HPV vaccine solution, combining affordability with effective cervical cancer prevention [16], 17].

Despite numerous studies showing the greater effectiveness of vaccines, the success of vaccination programs also relies on complex socio-cultural factors shaping parental decisions. Parental acceptance has been consistently identified as a critical determinant of childhood vaccination uptake across multiple studies and systematic reviews [18]. Exploring determinants such as risk perception, self-efficacy, and belief in vaccine efficacy is crucial for understanding parents’ willingness to vaccinate their adolescents against HPV [19]. Previous studies in Puducherry revealed limited awareness about cervical cancer and HPV vaccination, highlighting the need for further research in the community perception and beliefs about HPV Vaccination [20], [21], [22], [23].

Following successful demonstration projects in few states of India [24], 25], the Government of India announced the nationwide rollout of HPV vaccination for girls aged 9–14 years [26] in the Interim Budget 2024–2025 [27]. However, the specific timeline for incorporating HPV vaccination into the Universal Immunization Programme (UIP) remains unannounced, with pilot states continuing to refine rollout strategies for national implementation [26], 28], 29]. Currently, HPV vaccination in India is only accessible through private facilities; hence, the study explores the association of willingness to vaccinate with different types of health facilities (private and public).

This mixed-methods study aims to comprehensively understand the multidimensional factors influencing parental acceptance of adolescent HPV vaccination [30]. This contributes to developing effective interventions and strategies for encouraging successful vaccine uptake. This study aims to assess and find the association between risk perception, self-efficacy, vaccine response efficacy and willingness to vaccinate adolescents against HPV and to determine the sociodemographic and health-seeking behavioural factors associated with their willingness to vaccinate adolescents against HPV among their parents [31], [32], [33] and also to explore factors associated with willingness to vaccination among adolescent girls, their parents and healthcare workers.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A community-based explanatory mixed-method study was conducted from March 2023 to March 2024 among the parents of adolescent girls aged 9–18 years in 4 selected villages in the rural and urban field practice areas (defined geographical region where populations access services from designated health centres) of a Tertiary Care Centre in Puducherry. The field practice area has two Primary Health Centres (PHCs) providing preventive and curative services to the population of 8 villages. The PHCs operate under the guidance of a Medical Officer and Senior residents from the Department of Preventive Medicine and Social Medicine, with coordination by Junior Residents, Public Health Nurses, Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM), and Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA). Presently, health centres are focused on screening women over 30 for cervical cancer and conducting educational sessions to increase awareness about Cervical cancer.

Ethical approval and consent

The study was conducted after obtaining permission from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC approval number – JIP/IEC-OS/2023/079). Informed written consent was obtained from participants who are 18 years and above, while assent was obtained from participants aged 15–17 years before data collection in the local language. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the data collection process.

Operational definitions

Risk-perception: Risk perception is the subjective assessment of the characteristics and severity of a risk, as well as the perceived risks of HPV-related cancers

Self-efficacy: Confidence in one’s ability to prevent HPV infection without vaccination, i.e., How confident one can prevent being infected with HPV now and in the future without vaccinating against HPV.

Vaccine response-efficacy: Confidence in the vaccine’s ability to prevent HPV infection; It is measured as the perceived ability of the vaccine to prevent HPV infection.

Study population

The study population included parents of adolescent girls (9–18 yrs) who had resided in the field practice area for at least six months. Unwilling parents, those who did not provide written informed consent, were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling technique

The sample size was calculated based on an assumption of 50 % prevalence for the willingness of adolescents to undergo HPV vaccination, with a 95 % confidence level and 5 % absolute precision. This resulted in an initial sample size estimate of 384 participants, with half of the sample (192 participants) being collected from the urban and rural field practice areas.

A multistage random sampling technique was employed. In the first stage, two villages with larger adolescent populations were purposively selected from a list of eight villages within the urban and rural field practice areas. A line listing of all eligible adolescent girls was created using the registers maintained at the respective PHCs. The selected urban and rural PHCs had 544 and 305 eligible adolescent girls, respectively. Adolescents were then randomly selected from the line list using a lottery method and contacted their parents for the study. If parents could not be contacted after two attempts, they were removed from the list and new parents were selected using the lottery method, ensuring no replacement of previously selected participants.

For the qualitative component of the study, 10 interviews were conducted. These included five key informant interviews (KIIs) with healthcare workers (medical officers, public health nurses, and senior residents) and five in-depth interviews (IDIs) with adolescent girls and their parents [18], 34].

Study tool & data collection

Quantitative component

A pre-tested, structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was used for face-to-face interviews. The tool’s face and content validity were verified by a panel of three experts with relevant experience. It was translated into Tamil and pre-tested among 20 eligible parents outside the study settings. This semi-structured questionnaire consisted of 52 questions across four sections, including socio-demographic and health-seeking behaviour, knowledge regarding cervical cancer and HPV vaccination among the study participants (Questionnaire is available in Supplementary file 1).

During data collection, parents were approached at home. If multiple adolescent girls were present in the family, parents would provide information about the elder adolescent. The study procedure was explained, and informed consent was obtained before data collection. Following this, after assessment of the baseline knowledge regarding cervical cancer and HPV vaccination; a brief education session on them was provided, and then data such as i) perceived risk, self-efficacy, and vaccine response efficacy, and ii) willingness to vaccinate were collected. Responses of ‘yes’ were coded as 1, and ‘no’ was coded as 0. Based on expert opinion, each question was assigned a specific weight, and the weighted averages were calculated. The summed responses were divided into three categories, representing low, moderate, and high.

Qualitative component

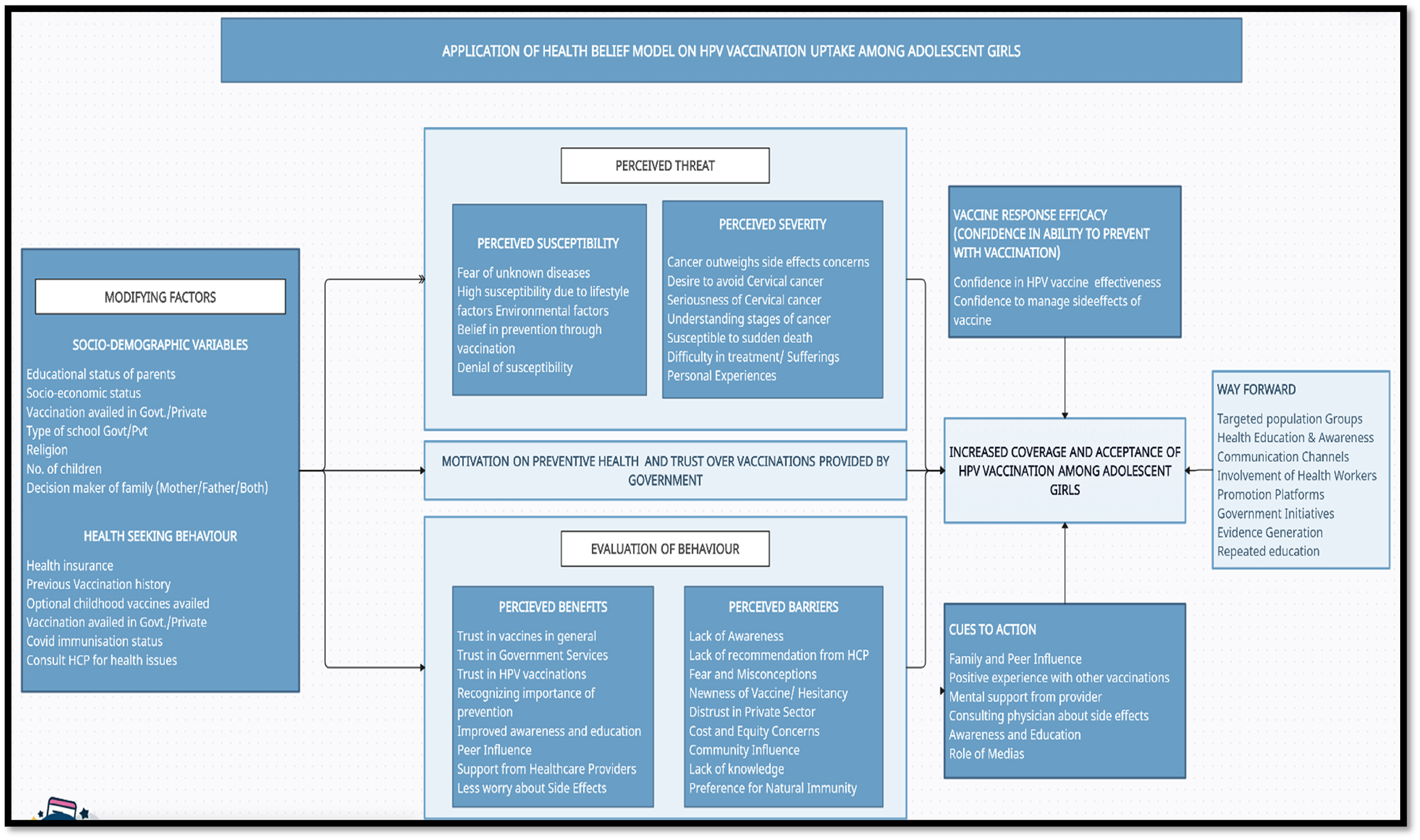

A semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary file 2) was developed based on quantitative phase findings and all six Health Belief Model (HBM) [23] domains. The guide contained open-ended questions exploring factors influencing HPV vaccination willingness, barriers and facilitators of HPV vaccination, perceived cervical cancer risk, self-efficacy, and vaccine response efficacy among adolescent girls and parents, while examining healthcare worker challenges and expectations.

Participants who are vocal and willing were selected purposefully. 10 interviews were conducted: five key informant interviews with healthcare providers and five in-depth interviews with adolescent girls and their parents in the regional language. All interviews conducted in private areas were recorded with their consent, lasting 15–20 min each. Participants reviewed summary points post-interview to ensure information accuracy.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative data was collected using Epicollect 5, and statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 23.0 software after adjusting for all missing values. Perceived risk, self-efficacy, and vaccine response efficacy were expressed in frequency and proportions with 95 % confidence intervals (CI). The associations between perceived risk, self-efficacy, vaccine response efficacy and willingness to vaccinate were analysed using the Chi-squared test based on the expected frequency and summarised as Odds Ratio with 95 % C.I. The associations between socio-demographic factors, health-seeking behaviour, and willingness to vaccinate were analysed using univariate regression and the crude Prevalence ratio (cPR) was estimated. The variables with a p-value of less than 0.20 were included in the multivariable log-binomial regression analysis, an adjusted Prevalence ratio (aPR) was estimated, and p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Qualitative analysis

Interviews were conducted and translated into English by the principal investigator. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim within one week of data collection to prevent information loss. Manual descriptive analysis was performed to generate codes, which were organised into categories and further grouped into sub-themes and overarching themes (categorisation available in Supplementary file 3). The Health Belief Model framework was utilised to develop sub-themes and overarching themes (Figure 1).

Conceptual model – HPV vaccine acceptance and coverage among adolescent girls.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

All 388 approached participants were available and consented to participate in the study, thus all were included in the analysis. The majority were mothers (94.8 %), mostly under 45 years old (86.3 %). Among adolescent girls, 51.8 % were aged 15–18 years. Most participants were Hindu (89.9 %) and lived in a nuclear family (69.8 %). Regarding education, about half of mothers (47.7 %) and fathers (49.5 %) had completed high school. Among the adolescent girls, 21.9 % were pursuing graduation, while 22.4 % were in higher secondary and middle school. The majority (76 %) held a red ration card, indicating lower economic status, and 66 % lacked health insurance. Fathers were mostly employed (93.3 %), while half of mothers (50.1 %) were employed and 61.9 % of households had four members or fewer (Table 2).

Distribution of risk perception, self-efficacy, vaccine response efficacy and willingness to vaccinate among parents of adolescent girls (9–18yrs) from selected urban and rural health centres, Puducherry, India, 2023 (n=388).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived risk | ||

|

|

||

| High | 174 | 44.8 (39.9–49.8) |

| Medium | 36 | 9.3 (6.8–12.6) |

| Low | 178 | 45.9 (40.9–50.9) |

|

|

||

| Self-efficacy | ||

|

|

||

| High | 94 | 24.2 (20.2–28.7) |

| Medium | 104 | 26.8 (22.6–31.4) |

| Low | 190 | 49.0 (44.0–53.9) |

|

|

||

| Vaccine response efficacy | ||

|

|

||

| High | 275 | 70.9 (66.2–75.2) |

| Medium | 100 | 25.9 (21.7–30.4) |

| Low | 13 | 3.5 (1.9–5.7) |

|

|

||

| Willingness to vaccinate in government | ||

|

|

||

| Yes | 355 | 91.5 (88.3–93.9) |

| No | 33 | 8.5 (6.1–11.7) |

|

|

||

| Willingness to vaccinate in private | ||

|

|

||

| Yes | 171 | 44.1 (39.2–49.1) |

| No | 217 | 55.9 (50.9–60.8) |

|

|

||

| Willing to pay (in INR) (n=355) | ||

|

|

||

| Less than 1,000 | 121 | 18.6 (26.8–35.9) |

| 1,000–2,000 | 72 | 31.2 (15.0–22.7) |

| Above 2,000 | 162 | 41.8 (36.9–46.7) |

Risk perception, self-efficacy, vaccine response

In the study population, 44.8 % of parents perceived high risk. When stratified by age groups, parents of early adolescents (ages 9–14) have a higher risk perception at 50.8 % compared to parents of late adolescents (ages 15–18) at 39.3 %. Nearly half of the parents (49.0 %) reported low self-efficacy, while a substantial majority (70.9 %) expressed confidence in the HPV vaccine’s effectiveness.

The majority of parents (91.5 %) were willing to vaccinate their adolescent daughters in government facilities,

I think only experienced doctors are available at government hospitals. So, I trust government hospitals and the medicine they provide, more than private hospitals. I will accept more if the vaccine is provided by the government – Adolescent Girl Mother (AGM)

While 44.1 % expressed willingness in private facilities, with half (41.8 %) willing to pay more than INR 2000 (Table 1).

I asked about this vaccination to the doctor in a nearby private hospital, but the rate of that injection is very high, so I haven’t vaccinated my daughter till now – AGM

Association of sociodemographic factors and willingness to vaccinate (private) among parents of adolescent girls (9–18yrs) from selected urban and rural health centres, Puducherry, India, 2023 (n=388).

| Variables | Totala n (%) | Willingness to vaccinate (private) | cPR | p-Valueb | aPR | p-Valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | ||||||

| Formal employment status of mother (n=387) | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Employed | 194 (50.1) | 83 (42.8) | 111 (57.2) | Ref | 0.649 | _ | _ |

| Unemployed | 193 (49.8) | 87 (45.1) | 106 (54.9) | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | _ | _ | |

|

|

|||||||

| Social class (modified BG prasad scale) | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Very high I | 27 (7.0) | 19 (70.4) | 8 (29.6) | 2.3 (1.6–3.3) | <0.001 | 4.9 (0.8–28.8) | 0.082 |

| High II | 106 (27.3) | 58 (54.7) | 48 (45.3) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | <0.001 | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.627 |

| Middle III | 108 (27.8) | 47 (43.5) | 61 (56.5) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 0.044 | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.770 |

| Low IV | 124 (32) | 38 (30.7) | 86 (69.4) | Ref | _ | Ref | _ |

| Very low V | 23 (5.9) | 9 (39.1) | 14 (60.9) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 0.404 | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 0.364 |

|

|

|||||||

| Religion | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Hindu | 349 (89.9) | 147 (42.1) | 202 (57.9) | Ref | 0.007 | Ref | 0.270 |

| Christian and muslims | 39 (10.1) | 24 (61.5) | 15 (38.5) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 1.4 (0.8–2.8) | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Health insurance (n=132) | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Government | 117 (88.6) | 42 (35.9) | 75 (64.1) | Ref | 0.036 | Ref | 0.778 |

| Private | 15 (11.3) | 9 (60.0) | 61 (40.0) | 1.6 (1.0–2.7) | 1.3 (0.3–5.9) | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Educational status of mother (n=385) | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Illiterate | 34 (8.8) | 10 (29.4) | 24 (70.6) | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | 0.609 | 1.2 (0.1–11.7) | 0.863 |

| Primary & middle | 57 (14.8) | 14 (24.5) | 43 (75.4) | Ref | _ | Ref | _ |

| High school | 184 (47.7) | 87 (47.3) | 97 (52.7) | 1.92 (1.2–3.1) | 0.007 | 4.4 (1.3–14.3) | 0.016 |

| Higher Secondary |

60 (15.5) | 27 (45.0) | 33 (55.0) | 1.8 (1.1–3.1) | 0.026 | 3.9 (1.0–15.8) | 0.049 |

| Graduation and above | 50 (12.9) | 31 (62.0) | 19 (38.0) | 2.5 (1.5–4.2) | <0.001 | 6.2 (1.5–26.3) | 0.013 |

|

|

|||||||

| Educational status of father (n=371) | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Illiterate | 25 (6.7) | 5 (20.0) | 20 (80.0) | Ref | _ | Ref | _ |

| Primary & Middle school |

55 (14.8) | 21 (38.2) | 34 (61.8) | 1.9 (0.8–4.5) | 0.137 | 0.4 (0.2–1.1) | 0.081 |

| High school | 184 (49.5) | 81 (44.0) | 103 (55.9) | 2.2 (0.9–4.9) | 0.053 | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 0.062 |

| Higher secondary | 38 (10.2) | 18 (47.4) | 20 (52.6) | 2.4 (1.0–5.6) | 0.043 | 0.4 (0.1–1.3) | 0.127 |

| Graduation and above | 69 (18.5) | 37 (53.6) | 32 (46.4) | 2.7 (1.2–6.1) | 0.018 | 0.2 (0.0–0.7) | 0.014 |

-

aColumn percentage; bchi-squared test; cmultiple logistic regression. The bold values indicate statistically significant results, i.e, p-value less than or equal to 0.05.

Since nearly 90 % would vaccinate if available in government facilities, analysing associations with willingness in that context would yield minimal additional value. Additionally, HPV vaccination in India is currently only accessible through private facilities. Therefore, all association analyses were restricted to assessing willingness to vaccinate in private healthcare facilities.

The association of sociodemographic factors with parents’ willingness to vaccinate their adolescent daughters against HPV, after adjusting for other factors, showed that higher maternal education levels were significantly associated with increased willingness to vaccinate. Compared to mothers with primary or middle school education, those with high school (aPR=4.4, 95 % CI: 1.3–14.3, p=0.016), higher secondary (aPR=3.9, 95 % CI: 1.0–15.8, p=0.049), and graduation or above (aPR=6.2, 95 % CI: 1.5–26.3, p=0.013) showed higher adjusted prevalence ratios for willingness to vaccinate. Fathers with graduation or higher education had a significantly lower adjusted prevalence ratio for willingness to vaccinate (aPR=0.2, 95 % CI: 0.0–0.7, p=0.014) compared to illiterate fathers (Table 2).

Risk perception, self-efficacy, vaccine response and their willingness to vaccinate

The association analysis revealed that parents with high perceived risk had 13 times higher odds of willingness to vaccinate their daughters compared to those with the least perceived risk (OR=13.9, 95 % CI: 8.3–24.4, p<0.001).

I believe in this vaccination because I’m afraid that in future, once I contract cervical cancer, I can’t avail of vaccination, so it is better to prevent it early by getting the vaccination – Adolescent Girl(AG)

Parents with low self-efficacy showed stronger association with willingness to vaccinate (OR=8.9, 95 % CI: 4.7–17.6, p<0.001).

I think that there is no need of vaccines, because I’m healthy, and I’m good. If I vaccinate there is chance to get some problems, so better not to vaccinate- AGM

Similarly, parents with a high perception of vaccine response efficacy, compared to those having moderate perception were significantly more likely to be willing to vaccinate their daughters (OR=5.7, 95 % CI: 3.3–10.2, p<0.001) (Table 3).

I have belief on vaccinations I was very confident I had given all known vaccines for my child from childhood onwards, so my kid is good and healthy, I was in Chennai(metropolitan city), so I know about all vaccines, I think this vaccine is also safe like that- Adolescent Girl Mother

Association between perceived risk, Self-efficacy, Vaccine Response efficacy and their willingness to vaccinate (private) adolescents against HPV among parents of adolescent girls (9–18 yrs) from the selected urban and rural health centres, Puducherry, India, 2023, (n=388).

| Perceived risk | Willingness to vaccinate (private) | Or (95 % C·I) | p-Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing, n (%) | Not willinga (n %) | |||

| Perceived risk | ||||

|

|

||||

| High | 123 (70.7) | 51 (29.3) | 13.9 (8.3–24.4) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 22 (61.1) | 14 (38.9) | 9.0 (4.1–20.3) | <0.001 |

| Least | 26 (14.6) | 152 (85.4) | Ref | – |

|

|

||||

| Self-efficacy | ||||

|

|

||||

| High | 13 (13.8) | 81 (86.2) | Ref | – |

| Moderate | 46 (44.2) | 58 (55.8) | 4.9 (2.4–10.4) | <0.001 |

| Least | 112 (58.9) | 78 (41.1) | 8.8 (4.7–17.6) | <0.001 |

|

|

||||

| Vaccine response efficacy | ||||

|

|

||||

| High | 153 (55.6) | 122 (44.4) | 5.7 (3.3–10.2) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 18 (18.0) | 82 (82.0) | Ref | <0.001 |

| Least | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | – | – |

-

aNot willing includes participants who reported both No and Not sure options to willingness to vaccinate in private facilities; bchi squared test

Health seeking behaviour

Regarding the health-seeking behaviour of the participants, 88.1 % of parents consulted healthcare workers for urinary tract infections, while 61.3 % sought advice from doctors in the past year. However, 76.5 % of the parents had not undergone cervical cancer screening. While all adolescent girls received compulsory immunisations under the universal schedule, only 6.7 % received optional vaccines. Moreover, 82.7 % of the parents were fully vaccinated against COVID-19. However, awareness about HPV was limited, with only 6.2 % having heard about it and 12.5 % aware of its association with cervical cancer. Additionally, only 8.2 % were aware of the availability of a cervical cancer vaccination (Table 4).

Association of health-seeking behaviour factors and willingness to vaccinate (private) among parents of adolescent girls (9–18 yrs) from selected urban and rural health centres, Puducherry, India, 2023, (n=388).

| Variables | Totala n (%) | Willingness to vaccinate (private) | cPR | p-Valueb | aPR | p-Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | ||||||

| Optional vaccines (varicella, typhoid, hepatitis A and PCV) | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Yes | 362 (93.3) | 21 (80.8) | 5 (19.2) | 1.9 (1.6–2.4) | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.520 |

|

|

|||||||

| No | 26 (6.7) | 150 (41.4) | 212 (58.6) | Ref | Ref | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Vaccination availed | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Govt | 353 (91) | 142 (40.3) | 211 (59.8) | Ref | _ | Ref | _ |

| Private | 16 (4.1) | 15 (93.8) | 1 (6.3) | 2.3 (1.9–2.8) | <0.001 | 2.5 (1.7–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Both | 18 (4.6) | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | <0.001 | 1.6 (1.0–2.6) | 0.044 |

|

|

|||||||

| Heard about cervical cancer | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Yes | 303 (78.1) | 138 (45.5) | 165 (54.5) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.287 | _ | _ |

|

|

|||||||

| No | 85 (21.9) | 33 (38.8) | 52 (61.2) | Ref | _ | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Knowledge about the cause of cervical cancer | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Correct | 38 (12.5) | 26 (66.7) | 13 (33.3) | 1.57 (1.2–2.0) | 0.001 | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) | 0.057 |

|

|

|||||||

| Incorrect | 265 (87.4) | 112 (42.4) | 152 (57.6) | Ref | Ref | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Knowledge about HPV | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| No | 218 (71.9) | 124 (43.7) | 160 (56.3) | Ref | 0.001 | Ref | 0.574 |

|

|

|||||||

| Yes | 19 (6.2) | 14 (73.7) | 5 (26.3) | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Heard about the HPV vaccine | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Yes | 25 (8.2) | 7 (28.0) | 18 (72.0) | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 0.837 |

|

|

|||||||

| No | 278 (91.7) | 158 (56.8) | 120 (43.2) | Ref | Ref | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Believe vaccine is safe | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| No | 223 (577.5) | 121 (54.3) | 102 (45.7) | 1.79 (1.4–2.3) | <0.001 | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 165 (42.5) | 50 (30.3) | 115 (69.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

-

aColumn percentage; bchi-squared test; cmultiple logistic regression. The bold values indicate statistically significant results, i.e, p-value less than or equal to 0.05.

Health care provider perspectives on risk perception and vaccine response efficacy among beneficiaries

Healthcare providers were interviewed to understand their views on how communities perceive health risks and respond to vaccines, based on their experience working with vaccination programs in the field. The quantitative findings showed that 78.1 % of respondents had heard about cervical cancer, primarily from Accredited Social Health Activists/Auxiliary Nursing Midwives (Healthcare providers at the community level in India) (41.9 %), television/newspapers (31.6 %), and doctors (16.5 %).

Healthcare providers identified significant knowledge gaps among parents and community members regarding HPV and cervical cancer. As one gynaecologist noted:

Their (parents) level of knowledge will be very low. First, I think there is a need to make them aware that the HPV infection causes cervical cancer. I don’t think they even know about it.

Public health nurses highlighted how vaccine availability affects their ability to provide education and also emphasised that community acceptance increases when people understand disease risks.

We are not giving awareness about HPV vaccination to prevent cervical cancer. because that vaccine is not available in the government supply; if it is available, then only we can conduct awareness among the public- Public Health Nurse (PHN)

There is a lack of felt need for this vaccination because they are unaware of the importance and burden… we know that the COVID vaccination rate has improved with the knowledge everyone is susceptible to the disease. uptake increased after the second wave, after a lot of deaths occurred. I felt the need for awareness is more important – PHN

Discussion

The study involved 388 parents, predominantly mothers (94.8 %), aged under 45 years (86.3 %). A majority of parents had heard of cervical cancer, but only a few were aware of HPV infection. Our study revealed low awareness about cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine among participants: 78.1 % were aware of cervical cancer, 6.2 % knew about HPV, and 8.2 % were informed about the HPV vaccine. In comparison, studies in Delhi (40.2 %) [35] and Haryana (81.8 %) [36] showed higher awareness of the HPV vaccine, while a study in Pondicherry reported only 5 % [20] awareness of HPV infection. These disparities in awareness levels across different regions and populations underscore the need for targeted and comprehensive awareness campaigns and educational interventions. The study revealed a relatively low proportion of cervical cancer screening (23.5 %) among the participants, in compared to similar studies conducted in Delhi [35] and Kerala, where the screening rates were 59.8 and 6.9 %, respectively. Low screening status is in the current study could be attributed to less awareness and acceptance in the population.

In our community, people have both high and low levels of perceived risk regarding HPV infection and cervical cancer. About half of the parents lack confidence in their ability to prevent infection without vaccination, while confidence in the vaccine’s ability to prevent infection is very high among individuals. These factors are positive predictors for getting vaccinated. The association showed that lower risk perception of HPV infection and cervical cancer, higher risk perception of vaccine-related side effects, greater self-efficacy, and lower perceived HPV vaccine response efficacy were linked to the decision not to vaccinate. Higher maternal and paternal education levels, stronger belief in vaccines, parents who vaccinated their children through private facilities, and those with accurate knowledge about the cause of cervical cancer were significantly associated with the willingness to vaccinate after adjusting for confounders.

The current study revealed a higher proportion of willingness to vaccinate daughters against HPV through government facilities (91.5 %) compared to private facilities (44.1 %). This finding contrasts with similar studies conducted in Kolkata [37] and in Delhi [35] in 2020 where the willingness to vaccinate was relatively lower at 25.5 and 63.14 %, respectively. The elevated proportion of willingness to vaccinate through government facilities in the present study could be attributed to factors such as a higher representation of participants from lower socioeconomic strata (76 % holding red ration cards) and a preference for government-provided healthcare services due to their perceived affordability, accessibility, and trust as observed in the study conducted in Delhi [38].

The study found a significant association between perceived risk and willingness to vaccinate adolescent daughters against HPV. Parents who perceived a high risk of HPV infection or cervical cancer were 13.9 times (95 % CI: 8.3–24.4) more willing to vaccinate (even from a private provider) compared to those with the least perceived risk. Similarly, parents with moderate perceived risk were 9.0 times (95 % CI: 4.1–20.3) more willing to vaccinate from a private provider than those with the least perceived risk. This finding is in line with the American study [19], which revealed that non-vaccinators had a lower risk perception of HPV-related cancers compared to vaccinators.

The observed relationship between perceived risk and willingness to vaccinate, explained by the Health Belief Model (HBM) [38], suggests that individuals are more likely to engage in preventive behaviours, such as vaccination, if they perceive themselves or their family members to be at a higher risk of contracting the disease. When parents perceive a high risk of HPV infection or cervical cancer, they may be more motivated to seek preventive measures, including vaccination, particularly through private healthcare facilities, which may be perceived as more accessible or reliable.

The results highlight a strong positive association between parents’ perceived vaccine response efficacy and their willingness to vaccinate their adolescent children against HPV. Parents who had a high perception of the vaccine’s ability to prevent HPV infection were 5.7 times more likely to be willing to vaccinate their children compared to those with moderate perceived response efficacy (OR=5.7, 95 % CI: 3.3–10.2, p<0.001). Similarly, no parents who perceived the least response efficacy were willing to vaccinate their adolescents. This finding aligns with several studies, including meta-analysis [39], which found that parents’ belief in the efficacy of vaccines improved HPV vaccine uptake for their children. Similarly, a study in Mysore [40] showed higher odds of HPV vaccine acceptability among parents who believed the vaccine was effective. The association between perceived vaccine response efficacy and willingness is well-explained by theoretical models like the Health Belief Model (HBM), which states that individuals are more likely to take preventive action (like vaccination) if they perceive the benefits of that action to be high. In this case, parents who strongly believed in the HPV vaccine’s ability to prevent infection (high response efficacy) were much more likely to vaccinate their children.

In contrast, the study indicates a significant inverse relationship between parents’ self-efficacy and their willingness to vaccinate their adolescents against HPV. Parents with the least self-efficacy were 8.9 times more likely to be willing to vaccinate compared to those with high self-efficacy (OR=8.9, 95 % CI: 4.7–17.6, p<0.001). Similarly, those with moderate self-efficacy were 4.9 times more likely to be willing than parents with high self-efficacy (OR=4.9, 95 % CI: 2.4–10.4, p<0.001). This finding aligns with other studies highlighting self-efficacy as a key factor influencing HPV vaccine acceptance, such as in an American study [19], which found that lower self-efficacy was associated with higher HPV vaccine uptake among parents. Similarly, Mysore study [32] reported lower odds of HPV vaccine willingness among parents who perceived low risk of their daughters getting cervical cancer, reflecting high self-efficacy.

Our mixed-methods study findings were integrated using the Health Belief Model framework (Figure 1), showing strong convergence across all theoretical constructs. Parents with high perceived HPV risk were more likely to vaccinate their daughters, with qualitative findings revealing similar vulnerability concerns driving vaccination motivation, while 44.4 % perceived high HPV risk with awareness of serious consequences like cervical cancer, confirming both susceptibility and severity pathways. Parents believing in vaccine effectiveness were more willing to vaccinate, supporting the benefits pathway, while 49 % had low confidence and qualitative findings revealed barriers including safety concerns, cost, healthcare access issues, and provider trust deficits, confirming that vaccination occurs when benefits outweigh barriers. Healthcare consultations served as cues to action for 88.1 % of participants, with 78.1 % receiving cervical cancer information from ASHA/ANM workers, demonstrating that provider recommendations and health education are critical vaccination triggers. This framework provides evidence for developing targeted interventions addressing specific health beliefs and structural barriers to adolescent HPV vaccination.

The study’s strengths include representative sampling from rural and urban areas for diverse population coverage, timely conduct before the HPV vaccination rollout to inform implementation strategies, provision of health education to ensure awareness, and a mixed-methods approach for a comprehensive understanding.

The study had some limitations, including social desirability bias and a limited geographic scope, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the lower representation of fathers – likely due to their work commitments during the data collection period (9:00 am to 5:30 pm) – may introduce selection bias and affect the sample’s representation.

Conclusion

The Government of India is soon rolling out the HPV vaccination for 9-14-year-old girls. This study assessed perceived risk, self-efficacy, vaccine response efficacy, and willingness to vaccinate among parents of adolescent girls in urban and rural Puducherry. In the study community, the perceived risk of HPV infection and cervical cancer varied. About half of the participants had low confidence in preventing infection without vaccination, while confidence in the vaccine’s effectiveness was very high. Parental education significantly influenced the decision to vaccinate. Most parents were willing to vaccinate their daughters if the vaccine is available under the national immunisation schedule. A higher perception of the HPV vaccine’s effectiveness and low self-efficacy were strongly associated with increased willingness to vaccinate in private facilities.

Recommendations

Recommendations include rolling out a nationwide HPV vaccination program supported by a comprehensive health promotion module to enhance awareness and acceptance among parents and communities. This module should emphasise the severity of cervical cancer, the susceptibility of adolescent girls to HPV infection, and its associated risks. It should also address concerns and misconceptions about the HPV vaccine by highlighting its proven safety and high efficacy in preventing cervical cancer, using evidence-based information and effective communication strategies.

Award Identifier / Grant number: BS/000103/24-25

-

Research ethics: The study was conducted after obtaining permission from the Institutional Ethics Committee. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Human Institute Ethics Committee (IEC approval number – JIP/IEC-OS/2023/079) of JIPMER. The participants were explicitly informed that their participation in this study was purely voluntary, and they could choose to withdraw from the study at any time without affecting their existing healthcare services from JIPMER or its health centres.

-

Informed consent: Informed written consent was obtained from participants 18 years and above, while assent was obtained from participants aged 15–17 years before data collection in the local language.

-

Author contributions: All authors have contributed substantially to the conception of the work, data analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting and revising it critically for important intellectual content. The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: All other authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The study was financially supported by JIPMER Intra mural fund – Grant number: JIPMER/2023/02061.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. World Health Organization. Cancer. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 3]. Available from: https://who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.Search in Google Scholar

2. World Health Organization. Cervical cancer [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 2]. Available from: https://who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer.Search in Google Scholar

3. Organisation WH. Cervical cancer | knowledge action portal on NCDs. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 13]. Available from: https://knowledge-action-portal.com/en/content/cervical-cancer.Search in Google Scholar

4. Ferlay, J, Ervik, M, Lam, F, Laversanne, M, Colombet, M, Mery, L, et al.. Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024. https://gco.iarc.who.int/today [Accessed 09 Sep 2025].Search in Google Scholar

5. World Health Organisation. Global declaration to eliminate cervical cancer; 2023. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 25]. Available from: https://pmnch.who.int/resources/publications/m/item/global-declaration-to-eliminate-cervical-cancer.Search in Google Scholar

6. World Health Organisation. WHO-Cervical-Cancer-India-2021-country-profile. Published 17th November, 2021. 2021:2021.Search in Google Scholar

7. World Health Organization. Cervical cancer. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 3]. Available from: https://who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer.Search in Google Scholar

8. National Cancer Institute. Cervical cancer causes, risk factors, and prevention - NCI. [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 25]. Available from: https://cancer.gov/types/cervical/causes-risk-prevention.Search in Google Scholar

9. Sung, H, Ferlay, J, Siegel, RL, Laversanne, M, Soerjomataram, I, Jemal, A, et al.. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. World Health Organization. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. World Health Organization; 2020:1–56 pp. [Internet] Available from: https://who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107.Search in Google Scholar

11. World Health Organization. WHO initiatives. JAMA 1996;276.Search in Google Scholar

12. World Health Organization. WHO adds an HPV vaccine for single-dose use. WHO; 2024. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 24]. Available from: https://who.int/news/item/04-10-2024-who-adds-an-hpv-vaccine-for-single-dose-use.Search in Google Scholar

13. World Health Organisation. WHO updates recommendations on HPV vaccination schedule. WHO; 2022. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 25]. Available from: https://who.int/news/item/20-12-2022-WHO-updates-recommendations-on-HPV-vaccination-schedule.Search in Google Scholar

14. World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological record: human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper (2022 update). Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2022;97:645672. [Internet] Available from: https://who.int/wer.Search in Google Scholar

15. World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2022;97:645–72.Search in Google Scholar

16. Ministry of science & technology. Press release: Press Information Bureau [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 25]. Available from: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1856034 Search in Google Scholar

17. Seruminstitute. Serum institute of India - CERVAVAC - Quadrivalent human papilloma virus (serotypes 6, 11, 16 and 18) vaccine (recombinant). [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 25]. Available from: https://seruminstitute.com/product_ind_cervavac.php.Search in Google Scholar

18. Dyda, A, King, C, Dey, A, Leask, J, Dunn, AG. A systematic review of studies that measure parental vaccine attitudes and beliefs in childhood vaccination. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09327-8. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 29] Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-09327-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Myhre, A, Xiong, T, Vogel, RI, Teoh, D. Associations between risk-perception, self-efficacy and vaccine response-efficacy and parent/guardian decision-making regarding adolescent HPV vaccination. Papillomavirus Res 2020;10:100204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2020.100204.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Arumugam, P, Habeebullah, S, Chandra Parija, S. Knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV), and HPV vaccine among screening women: a cross-sectional study from a tertiary care hospital in South India. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 2018;7:2431–4. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.703.283.Search in Google Scholar

21. Veerakumar, AM, Kar, SS. Awareness and perceptions regarding common cancers among adult population in a rural area of Puducherry, India. J Educ Health Promot 2017;6:38. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_152_15.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Boratne, AV, Angusubalakshmi, R, Maniraj, S. Awareness and practices regarding cervical cancer among women of self-help groups in rural Puducherry. Med J Dr DY Patil Vidyapeeth 2022;15:381–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/mjdrdypu.mjdrdypu_376_20. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 25] Available from: https://journals.lww.com/mjdy/fulltext/2022/15030/awareness_and_practices_regarding_cervical_cancer.19.aspx.Search in Google Scholar

23. Paul, P, Tanner, AE, Gravitt, PE, Vijayaraghavan, K, Shah, KV, Zimet, GD. Acceptability of HPV vaccine implementation among parents in India. Health Care Women Int 2014;35:1148–61.10.1080/07399332.2012.740115Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Sankaranarayanan, R, Basu, P, Kaur, P, Bhaskar, R, Singh, GB, Denzongpa, P, et al.. Current status of human papillomavirus vaccination in India’s cervical cancer prevention efforts. Lancet Oncol 2019;20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30531-5. [Internet] [cited 2025 Jul 27] e637–44. Available from: https://sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1470204519305315.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Prinja, S, Bahuguna, P, Faujdar, DS, Jyani, G, Srinivasan, R, Ghoshal, S, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination for adolescent girls in Punjab state: implications for India’s universal immunization program. Cancer 2017;123:3253–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30734. [Internet] [cited 2025 Jul 27].Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Burki, TK. India rolls out HPV vaccination. Lancet Oncol [Internet] 2023;24:e147. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(23)00118-3.Search in Google Scholar

27. The Hindu Bureau. Budget 2024 | government to focus on vaccination against cervical cancer – the Hindu. [cited 2025 Jul 28]; Available from: https://thehindu.com/business/budget/govt-to-focus-on-vaccination-against-cervical-cancer-announces-finance-minister-nirmala-sitharaman/article67799549.in.Search in Google Scholar

28. Kataria, I, Siddiqui, M. Human papillomavirus vaccine: a public health opportunity for cervical cancer prevention in Indian states [Internet]. Rockville, MD: RTI International; 2022. Available from: https://www.rti.org/publication/human-papillomavirus-vaccine-public-health-opportunity-cervical-cancer-prevention-india/fulltext.pdf Search in Google Scholar

29. India Science T and IP. HPV vaccination received a push in budget 2024 | India science, technology & innovation - ISTI portal. [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 24]. Available from: https://indiascienceandtechnology.gov.in/listingpage/hpv-vaccination-received-push-budget-2024#main-content-section.Search in Google Scholar

30. Garbutt, JM, Dodd, S, Walling, E, Lee, AA, Kulka, K, Lobb, R. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination in primary care practices: a mixed methods study using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0750-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Madhivanan, P, Li, T, Srinivas, V, Marlow, L, Mukherjee, S, Krupp, K. Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among parents of adolescent girls: obstacles and challenges in Mysore, India. Prev Med (Baltim) 2014;64:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.002. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 25] Available from: https://sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S009174351400125X.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Degarege, A, Krupp, K, Srinivas, V, Ibrahimou, B, Marlow, LAV, Arun, A, et al.. Determinants of attitudes and beliefs toward human papillomavirus infection, cervical cancer and human papillomavirus vaccine among parents of adolescent girls in Mysore, India. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2018;44:2091. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.13765. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 25] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6996479/.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Singh, M, Goyal, P, Yadav, K, Barman, P, Dagar, R, Nassa, K, et al.. Awareness and willingness of mothers and daughters for human papillomavirus vaccination uptake – a cross-sectional study from rural community of faridabad, Haryana. J Prim Care Spec 2024;5:64–71. https://doi.org/10.4103/jopcs.jopcs_47_23. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 25] Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jopc/fulltext/2024/05010/awareness_and_willingness_of_mothers_and_daughters.12.aspx.Search in Google Scholar

34. Kasting, ML, Wilson, S, Dixon, BE, Downs, SM, Kulkarni, A, Zimet, GD. Qualitative study of healthcare provider awareness and informational needs regarding the nine-valent hpv vaccine. Vaccine 2016;34:1331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.050. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 30] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4995443/.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Singh, J, Roy, B, Yadav, A, Siddiqui, S, Setia, A, Ramesh, R, et al.. Cervical cancer awareness and HPV vaccine acceptability among females in Delhi: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Cancer 2018;55:233–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijc.ijc_28_18. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 25] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30693885/.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Hussain, S, Nasare, V, Kumari, M, Sharma, S, Khan, MA, Das, BC, et al.. Perception of human papillomavirus infection, cervical cancer and HPV vaccination in north Indian population. PLoS One 2014;9:e112861. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112861. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 28] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4227878/.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Basu, P, Mittal, S. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine among the urban, affluent and educated parents of young girls residing in Kolkata, Eastern India. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2011;37:393–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01371.x. [Internet] [cited 2025 May 28].Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Gray, A, Fisher, CB. Factors associated with HPV vaccine acceptability and hesitancy among black mothers with young daughters in the United States. Front Public Health 2023;11:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1124206.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Newman, PA, Logie, CH, Lacombe-Duncan, A, Baiden, P, Tepjan, S, Rubincam, C, et al.. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open 2018;8:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019206.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Degarege, A, Krupp, K, Fennie, K, Srinivas, V, Li, T, Stephens, DP, et al.. An integrative behavior theory derived model to assess factors affecting HPV vaccine acceptance using structural equation modeling. Vaccine 2019;37:945–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2024-0096).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.