Abstract

Social media plays a crucial role in United Nations (UN) peace operations, which are typically deployed in regions affected by conflict to promote peace, facilitate political dialogue, and support post-conflict reconstruction efforts. The UN has introduced the concept of the digital peacekeeper, whose role is to collect and analyse public data, with a particular focus on social media. This article explores the role of official social media use by African peace operations (POs) between 2003 and 2024 through a qualitative analysis of 126 UN documents. The findings reveal that African POs employ a diverse communication strategy, primarily centred on disseminating information, education, and access to reliable information in disrupted contexts. However, the full potential of social media is not realised, resulting in a predominantly one-way communication model. Using affordance theory for social media, the paper demonstrates how bidirectional interactions could support sustainable peace efforts.

1 Introduction

Since 2020, the number of global conflicts has doubled, and they have become increasingly complex, involving a growing number of both state and non-state armed actors. 1 Africa continues to experience the highest number of state-based conflicts annually (28 in 2024), followed by Asia (17), and the Middle East. 2 In response to such long-standing conflicts, as well as to health crisis, such as the global COVID-19 pandemic 3 or the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in 2019, the United Nations (UN) Peace Operations (POs) are deployed in several contexts with the aim to stabilize conflict zones and support efforts toward peace and security. In line with these objectives, they operate only when invited, act impartially, and use force only for self-defense. 4 As of January 2025, the UN is carrying out 11 peacekeeping missions worldwide, with four in the Middle East, one in Europe, one in Asia, and five in Africa. 5 The importance of the African continent is particularly noteworthy, as it has been the site of 32 of the 71 UN peace operations conducted to date. This makes Africa a critical focus for understanding the role and impact of peacekeeping, given its historical and ongoing relevance in UN operations. 6 In 2021, the United Nations (UN) launched the ‘Strategy for the Digital Transformation of UN Peacekeeping’, as ‘a strategic initiative aimed at leveraging digital technologies to enhance the effectiveness of peacekeeping operations and improve mandate delivery’. 6 This strategy aims to include data-driven approaches to enable local communities and improve situational awareness and response to peacekeeping missions. In crisis informatics, Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and the use of social media (SM) have facilitated new modes of communication both among authorities as well as with citizens during natural and human-made disasters, leading researchers to investigate their use in crises and safety-critical contexts. 7 , 8 Thereby, crisis informatics ‘views emergency response as an expanded social system where information is disseminated within and between official and public channels and entities’. 9 This may be particularly important in the context of UN POs.

In the African contexts, where numerous UN missions are based (namely, South Sudan, Abyei, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Somalia, Western Sahara), the overall number of social media users is steadily increasing; however, access remains uneven across the continent. Northern and Southern African countries have relatively high internet penetration rates of 71 % and 66 % respectively, while Central and Eastern Africa lag behind with only 28 % and 23 %. 10 This is supported by the growing use of mobile phones as the primary device used. A survey by GeoPoll in 2023 with 4170 participants in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa has shown that 96 % of the participants preferred their mobile phones as the primary source of access to social media platforms. Among the platforms, Facebook (82 %), TikTok (60 %), Instagram (54 %), and X (49 %) were the most used ones. 11 This trend demonstrates the significance of ICTs, particularly SM, in the contemporary era. Recent studies have indicated that SM has become a substantial source of novel data on conflicts 12 and peacebuilding 13 since 2003 – a period that coincides with the emergence of SM and the commencement of research on SM’s role in crisis response. 7 In general, ICTs have become a crucial resource for conflict parties, fundamentally transforming the information landscape available to actors and influencing the dynamics of conflict. At the same time, ICTs, particularly social media, can serve to support and engage local communities, while providing vital, timely information for incident reporting and situational assessments. 13

Whereas the advent of new data on POs has enabled researchers to expand the frontiers of research and undertake a more nuanced examination of their effectiveness, it seems questionable to what extent those new data, as a means for crisis communication, are already used by POs. 14 Given the limited research on how POs use social media for their operations – and the fact that most POs are conducted on the African continent – this study aims to explore this issue in greater depth by investigating how social media platforms have been used for facilitating crisis communication between UN peace operations and citizens in the African context since February 2003. Our research aims to do so by focusing on three research questions (RQs):

How are social media platforms used by POs in the African context to communicate with citizens?

What media strategies do the POs in the African context follow?

What challenges arise from the use of social media by POs in African countries?

The following section will present a concise overview of the current state of research in this field. To this end, the role of SM in African POs will be illustrated, followed by a broader review of the use of SM in POs (Section 2). The focus lies on the use of SM to disseminate crisis information to citizens and the integration of citizen-generated content into crisis management. To investigate the utilization of SM in African POs, a qualitative document analysis (N = 126) was conducted on a selection of official UN documents and guidelines related to these missions (Section 3). Based on the findings (Section 4), implications for using social media are drawn from the perspective of SM affordances, and challenges for POs in the African context are discussed (Section 5).

2 State of research

For several years, research has examined the role of ICTs in conflict and peace processes. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 The transformation of the communication landscape in African countries has the potential to provide POs with an essential pool of data, improving the transmission of crisis-relevant information to affected citizens while addressing existing challenges and promoting peace. 13

2.1 UN peacekeeping and crisis communication

UN POs are initiated by the UN Security Council (UNSC) to maintain peace (peacekeeping) in conflict-affected areas. The deployment of UN POs is contingent upon the mutual consent of the involved parties, and the forces involved are required to act impartially, reserving the use of force exclusively for self-defence and the enforcement of the UN mandate. 4 Peace operations aim to protect civilians from violence and act as ‘key elements of a long-term peace strategy’ for a region. 19 However, the mandates of POs have changed over time from liberal state-building to stability-oriented conflict management and counter-terrorism missions. 19 Peacekeeping is a broad term that concerns the transformation of behaviour and relationships of groups toward more peaceful conflict resolution by using education and social change. 20 PO missions were increasingly extended in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as their tasks shifted from observatory roles to ‘a wide variety of complex tasks, from helping to build sustainable institutions of governance, to human rights monitoring, to security sector reform, to the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of former combatants’. 21 Since then, addressing local communities and political groups to gain access to information and engage them to participate in peace processes has been among the tasks of POs. Therefore, the strategies and media channels used by POs have also been adapted.

In 2021, due to the increasing importance of ICTs, the UN launched the digital peacekeeping initiative to improve the work and effectiveness of POs by using digital technologies. This strategic initiative strives to improve the ability to react to incidents and work more efficiently to fulfil the mission’s mandate. This builds on ‘optimizing information sharing and data management’ for improved situational awareness, capacity building for data management, innovation assessment, and addressing disinformation, both for improved local cooperation and workstreams within the POs. 6 Social media platforms have gained importance in distributing information and engaging the local population in peace processes. The UN highlighted this, ‘launching a global campaign in 2023, Peace Begins with Me, which has significantly increased engagement on social media compared with 2022’ (2023-2-OverallPerformance, p. 15). However, ICTs cannot be regarded as a standalone solution to the complex issues of peacekeeping and conflict resolution. 22 Even though using ICTs in peace processes has been discussed as an enabler for participation, 23 and as a contribution to peacebuilding,[1] it is important to have a nuanced understanding of the role of ICTs.

Therefore, Hirblinger et al. 15 provide a methodological framework on ‘how technologies for peacebuilding and peacebuilding with technology are coproduced’ [emphasis by the authors]. Rather than seeing technology as inherently good or bad, the framework helps to investigate the power structures that shape socio-technical systems in peacebuilding and its technology: ‘Alternative research framework for the critical–reflexive study of digital peacebuilding, along with suggestions for how it may be operationalized’. 15 Wählisch 24 (p. 124) points out that the shift towards digital peacekeeping will take time and requires an institutional dialogue to define the operational purpose of ICTs in peacekeeping. Further, technology assessment can help to clarify ‘perceived political sensitivities and ethical boundaries of data collection in the sustaining peace context’ as ‘a precondition to address myths about what is politically unwarranted and practically essential for the UN to perform its duties in the 21st century.’

Moving beyond peacekeeping, crisis informatics has shown that citizen-generated content in the form of text, photos, and videos bears great potential for emergency services to analyze crisis situations. 8 For a PO, its ability to maintain a strong understanding of public sentiments and its operational environment is essential to react early and properly. 25 The capability to access and analyze digitally generated data can open a rich source of information about social and cultural attitudes, intentions, and behavior, as well as information in crises. 26 Social media, with its affordances such as two-way communication, visibility, immediacy, and networked connectivity, 27 enables citizens to share their voices and provides peace operations with opportunities to engage directly with local populations. This interaction facilitates the exchange of input, timely warnings, and collaborative problem-solving. 28 , 29 , 30 Esberg and Mikulaschek 29 (p. 24) emphasize that ‘regularly comment[ing] on security incidents leads the public to expect instant public responses,’ which can sometimes be challenging.

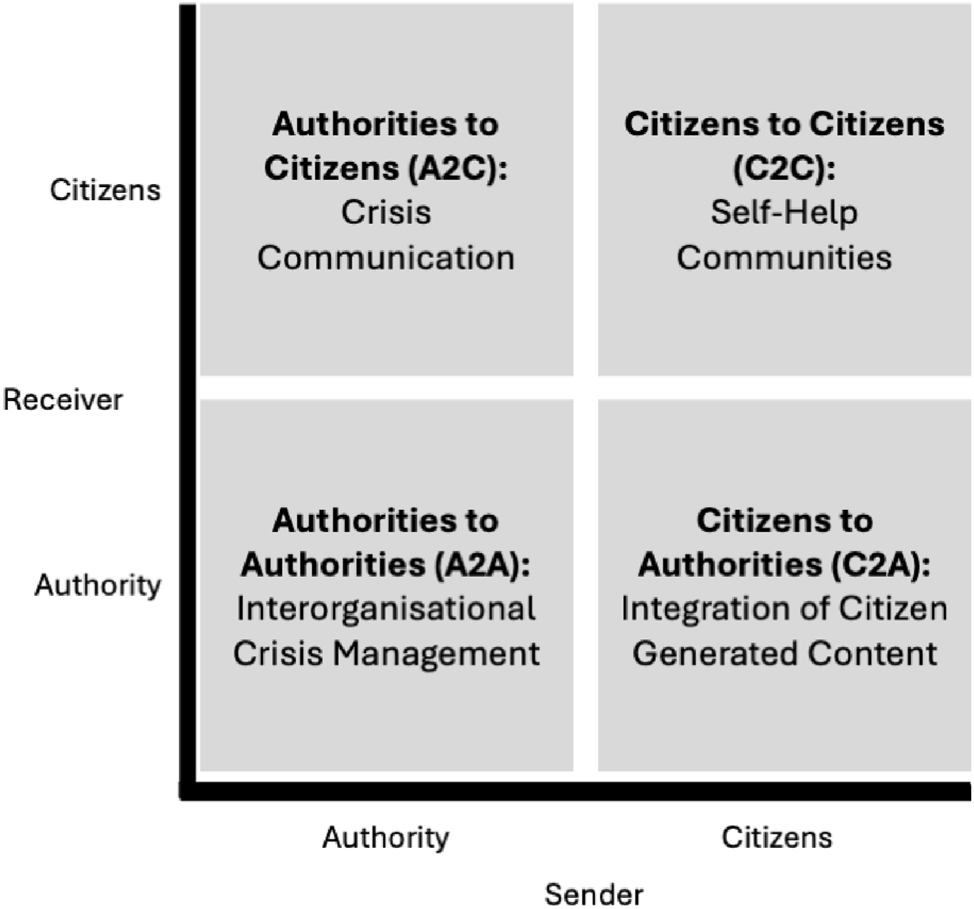

Crisis informatics has studied the socio-technical systems of crisis response and management in disaster and crisis situations. In this, collaborative and computer-supported group work is an essential part of the ubiquitous role of computing and information technology. 32 As part of crisis communication and management, SM has shown to be highly relevant for practitioners as well as scholars. 7 Bukar et al. 33 summarize the field of crisis informatics to research ‘the use of social media in crisis, and also the fact that addressing crisis on social media can be termed as social media crisis communication’. Thus, it combines crisis communication as strategic communication with the use of social media in crisis management. 7 , 33 In the context of crisis communication, Reuter et al. 31 present a matrix (see Figure 1) that offers types of interaction between the sender (x-axis) and the receiver (y-axis). The interactions can take place between authorities (A) and citizens (C) or between similar actors. In a crisis, authorities often provide information to citizens. This form of communication is named ‘crisis communication’ (A2C). However, authorities also need to communicate and coordinate with other authorities, which is considered ‘inter-organizational crisis management’ (A2A). Local communities of citizens or volunteers form ‘self-help communities’ (C2C), which themselves use communication infrastructure, e.g., social media platforms, to connect and assess the situation. Lastly, as social media offers bi-directional communication, citizens can also address authorities, e.g., to search for help in the form of ‘citizen-generated content’ (C2A). Leveraging crisis communication by integrating diverse and bi-directional information flows in crisis using social media can be operationalized by defining roles, as suggested by Reuter and Kaufhold. 7 These roles include people who act as observers, who report and amplify or translate messages from authorities to their local communities. Transferring this conceptual work to the context of African POs, it becomes apparent that the typology is both helpful and challenging, as the regional context needs to be considered.

Crisis communication matrix according to Reuter et al. 31

Citizens use social media networks (e.g., Facebook/Meta), microblogging services (e.g., X), multimedia sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube), or instant messengers (e.g., WhatsApp) mostly to communicate, to share information, and for entertainment purposes. Furthermore, SM can be used to stay informed during crises. 34 Therefore, not only do citizens depend on information, but emergency services also require high-quality information to improve their situational awareness. Information such as eyewitness accounts are particularly useful in this regard and can be shared in real-time on, e.g., collaborative platforms. 35 Smidt 36 analyzes the role of local POs activities with community leaders and the population for a community-based intergroup dialogue. This aims to revitalize intergroup coordination and diminish negative prejudices, thereby reducing the risk of communal conflict escalation. Moreover, including citizens in peace processes is crucial because it ensures that the voices, needs, and perspectives of those most affected by conflict are heard and addressed. When citizens actively participate, it leads to more inclusive, sustainable peace outcomes. 37 As demonstrated in the crisis communication matrix developed by Reuter et al. 31 (see Figure 1), this would be considered the citizen to authorities (C2A) approach to communication.

2.2 Social media use in the African context

The fundamental change in the African communication sector 11 is accompanied by the rapid growth of SM platforms, which are enabling new forms of collaboration and interaction among its users. 38 The emergence of ICTs in numerous African countries has led to a debate on whether and to what extent they influence political collective action and violent conflict. 29 While much of the literature observes an increasing use of SM, 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 some authors specifically deal with the emergence of citizen journalism 41 , 44 , 45 , 46 and ICT-enabled activism. 46 , 47 Especially in crisis areas, citizen journalists provide critical information online and offer counter-narratives to mainstream media. 48 One example is the Ushahidi platform, which was developed in Kenia and utilizes crowdsourced data from SMS, X, and e-mail to visualize information about, for instance, violence and election fraud in real-time and is used in nine African countries. 49

While most countries in the Global North experienced the introduction of radio long before the introduction of cellular infrastructure, the order and timing of introducing these technologies vary greatly between African countries. As a result, many areas that were never connected to fixed-line communications networks are now covered by cellular networks. Moreover, several challenges, such as the digital divide, hinder the use of ICTs in peace processes. 50 Additionally, there are still enormous regional differences in terms of infrastructure and mobile access, especially in rural or conflict-torn areas, causing asymmetric information and communication structures. 39 Another relevant aspect is the growing use of SM by radical or terrorist groups to enunciate not only their ideological orientations but also to attack national governments and enhance their reputations and prestige. 51 , 52 , 53

Mobile phones are the most used device in various African countries, with high personal ownership rates of 84 % on average and cell phone coverage of 87 %. 54 Thus, operations use mobile phones for community alert networks (CANs) in the DRC, which rely on SMS and mobile communication. By taking advantage of the increase in cell phone usage, the PO in DRC (MONUSCO) pioneered the use of ICTs to improve its situational awareness and early warning. They distributed phones to key individuals in local communities, who were instructed to call and alert the operation upon seeing signs of impending danger or being under threat. The CANs were part of a greater effort to improve responsiveness to local populations’ needs and better protect them. 55 , 56 However, the approach was changed when the PO identified the increased vulnerability of receivers as potential targets for violence. 56

To obtain data indirectly from citizens, POs often rely on intelligence instruments, such as the use of SM intelligence like the All Source Information Fusion Unit (ASIFU), established within the scope of the PO in Mali (MINUSMA). 57 One of its most prominent innovations was a small but dedicated department for open-source intelligence, which, instead of relying on traditional open sources such as news articles, radio, and television, focused mostly on user-generated content on the internet, such as Facebook/Meta, X, Wikis, and internet forums. The department was able to obtain in-depth information on specific issues by analyzing geo-tags of SM posts and to get indications of different perspectives on certain matters or events. 58 , 59 A similar tool has been developed by the stabilizing mission in the DRC (MONUSCO), the mission in the Central African Republic (CAR), and the mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA). They developed a flashpoint matrix to identify risks for physical violence against civilians and facilitate a multidimensional response. 57 However, it was observed that not all voices have equal access to social media discourses: UN agencies, large non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and donor agencies, as well as the diaspora, tended to dominate the Twittersphere, while marginal voices were underrepresented. 60

Connecting to insights from crisis informatics, ICTs can offer POs to include them in their crisis communication efforts to disseminate information on how to behave during a crisis. 8 Hence, POs can use online and offline communication channels to inform civilians in crisis areas, offering them a channel for reliable information to combat disinformation. 16 , 29 The more transparent peacekeepers report information about their mission, goal, and approach in the public sphere, the more likely it is that the local population will build trust and, thus, be more willing to share information. 61 Recent literature, such as Esberg and Mikulaschek 29 and Henigson, 62 discusses approaches used by peacekeepers to share information and to promote community engagement. Whereas Gordon and Loge 26 as well as Orme 63 examine UNs’ long history of using traditional mainstream media and particularly radio communication during times of crisis, Cooley and Jones 64 focus on the mission of the African Union in Somalia’s (AMISOM) as well as the UNHCR use of SM via Twitter during the 2011 famine crisis. They analyzed the usage of the AU Twitter account @AMISOM to communicate with the public, observing that the account directed every single message away from Twitter to government-managed websites. Moreover, the posts were focused on praising their efforts to mitigate the crisis, leading to an increase in distrust compared to the UN account, which cited different sources more often.

To summarize, the official UN strategy for digital peacekeeping was launched in 2021, but there has been active use of SM by PO missions before because there is consensus on the usefulness of including ICTs in crisis management and peacekeeping. Some work has focused on conceptual questions regarding the socio-technical systems and their power balances, 15 , 50 as well as implications for the institutional discourse, while there have also been case studies of ICT use as part of crisis management 7 , 8 , 34 as well as peacekeeping. 57 , 59 , 65 The exploration of ICTs in peacekeeping has been evaluated by Hall et al. using a value-sensitive design approach from user-centred design in the case of MINUSMA. Thus, there are both conceptual studies and those that focus on a singular case. Empirical studies still need to investigate several missions over time regarding their ICT use and their SM-enabled collaborative approach to two-way communication.

3 Research design

3.1 Data collection

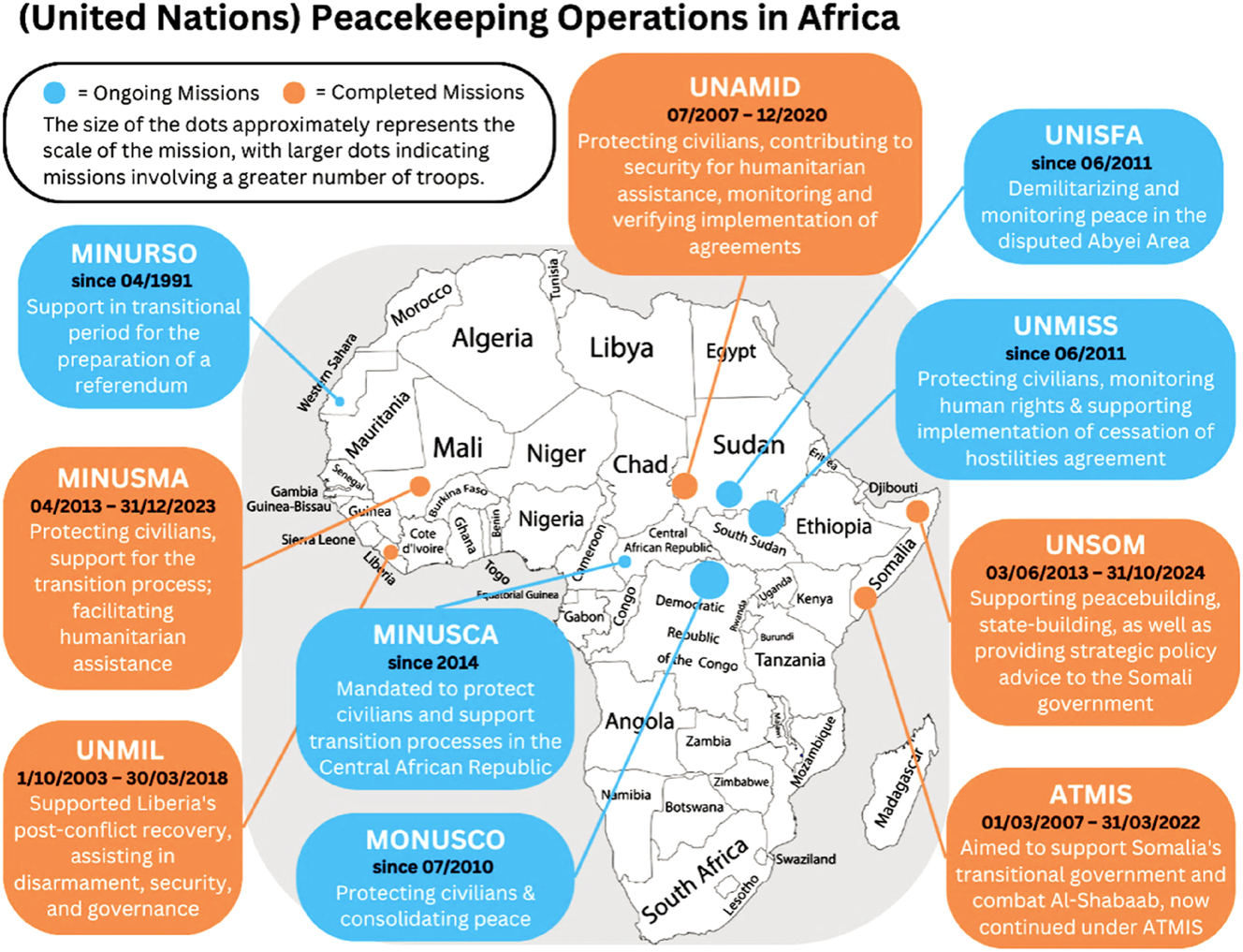

As previously stated, many POs have been carried out in Africa. As demonstrated in Figure 2, several missions have been completed since 2003 (the commencement of the present analysis), while others remain ongoing. Most of these POs commenced in the 2010s and 2020s; however, MINURSO in Western Sahara began functioning as early as 1991. All POs are charged with a similar mandate, namely, to monitor violence and contribute to establishing peace. 5 , 66

Overview of UN peacekeeping operations in Africa. Source: Own depiction based on. 5

To obtain a comprehensive overview of ICT use in African POs, the analysis spans from February 2003 to March 2024. Even though SM has been used before, this period was chosen as 2003 showed a significant increase in the use of SM and research on SM’s role in crisis response. 7 Additionally, it encompasses the COVID-19 pandemic period, which saw a significant increase in digitalization, 67 leading to an overall increase in the number of documents after 2020. This broad timeframe allows for better tracking of temporal developments in using ICTs and long-term trends. The sources for the dataset were selected in accordance with the research questions and included a sample of publicly available documents, which were accessible through official UN and PO websites and were used as databases.[2] The document selection process took place in two phases: First, a keyword search was conducted for the relevant period and was limited to African POs on three different UN websites. This resulted in an initial selection of documents containing the terms social media, ICT, social networks, technology, crisis, and media. A total of 138 documents were initially identified. This preliminary selection was further scrutinized in the second phase to qualitatively assess its relevance to the research questions. If a document’s content was not directly relevant, an expanded keyword search was conducted before the document was finally excluded from the dataset. The following terms were anticipated to be relevant content categories for the qualitative analysis and thus indicate relevance for the topic: social media, multimedia, digital, video, hate speech, fake news, dis- and misinformation, Artificial Intelligence (AI), ICT, radio, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook. Documents that did not contain the specified terms were excluded from the final dataset, resulting in a refined dataset of 126 documents.

The selected documents can be grouped into three categories: (1) News and press statements, (2) UN peacekeeping handbooks and guidelines, and (3) mission reports and news. The selection of documents was based on their relevance and availability, leading to variations in the publication periods depicted in Table 1. For better reader guidance, the authors named the documents in the following convention: For (1) and (2), <year-document type-shortname> and for (3) <year-document type-mission>. This helps the reader to attribute the document to a year and a mission or to a type of publication.

Overview of the selected documents. A full overview is given in the supplement material. Source: own depiction.

| Category | Sources | Authors/contributors | Publication period | Number of documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. News and press statements (document type 1) | Retrieved from UN’s main website | Drafted by UN peacekeeping, UN department of global communications, the secretary-general, and interviews with the UN head of social media as well as the social media team leader at the UN | 2015–2024 | 29 |

| 2. UN peacekeeping handbooks and guidelines (document type 2) | UN PO official websites | Drafted by the department for peacekeeping operations (DPKO), the secretary-general, the department of public information (DPI), the general assembly, and the high-level panel on UN peace operations | 2003/2004-2024 | 21 |

| 3. Mission news and reports(document type 3) | Retrieved from the POs websites (operating in africa) | Drafted by the individual POs to report to the UN secretary general and the UN security council, or as part of the press releases to inform media outlets and citizens | 2013–2024 | 75 |

Subsequently, a review of the documents was conducted to select those that were most relevant to the RQs. Official UN sources were deemed particularly important, as they provide insight into the official stance and handling of communication and the inclusion of SM in POs. The data distribution reveals a slight imbalance, with the dataset including only 40 documents up to the year 2020 (the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic), while 85 documents cover the subsequent period. This disparity can be attributed to the intensifying relevance of the subject matter and the consequent surge in publications. Due to access restrictions on the UN database, only mission reports from 2013 onward could be retrieved. The list of documents can be found in the Appendix, Table 5.

3.2 Data analysis

The documents were analyzed using a qualitative approach. Interpretative logic and procedures from qualitative methodology are employed, and accordingly, content analyses are carried out to evaluate the documents’ informative value. 68 Firstly, a category system was deductively developed to structure the data based on the literature review and theoretical background of crisis informatics and communication (see Section 2). Subsequently, a qualitative content analysis was conducted, underpinned by the explicitly mentioned categories in the data. The aim of this analysis was to identify preliminary patterns based on frequencies, thereby providing an overview of the data and recognizing prevalent themes in the period before the global pandemic (from February 2003 to March 2020) and after (2020–2024). 69

Following this process, content itemization is performed using qualitative content analysis. 68 This method aims to filter and summarize specific topics, contents, and aspects from the material based on predefined aspects. However, Gläser and Laudel 68 emphasize the necessity of maintaining openness throughout the analysis process. Their approach suggests that extracting information from documents should remain receptive to unpredictable information, allowing for adjustments to the category system if relevant data emerges that does not fit the existing categories. Therefore, the authors enriched the deductively formed categories with inductively derived codes throughout the analysis process. The definitions of these codes were developed deductively, drawing on established research in crisis informatics, 7 , 31 and peace operations. 18 , 28 , 70 Existing literature informed the development of categories and guided the structuring of our findings.

Three researchers conducted the coding in two iterations due to the two iterations of data sampling before and after COVID-19. In the second iteration, documents published after 2020 were added, and the codebook was revised and applied to all sources published before 2020 again. The reviewers then engaged in deliberations to reach a consensus on the coding of unclear examples. This iterative process was undertaken until a consensus was reached on all codes and the codebook was sufficiently refined. The comprehensive codebook is provided in the Appendix (see Table 6). The analysis of the data was facilitated by using the software MAXQDA.

4 Empirical findings

The results of the analysis will be presented in the following section, answering the research questions on the use of social media, the strategies POs followed, and the challenges they encountered.

4.1 RQ1: the use of social media in African peace operations

The mission budget reports contain detailed summaries of the media activities of the missions, as well as some descriptions of outreach success, such as follower numbers of SM channels. The mission guidelines formulate strategic goals of SM use, define what content should be posted and how official accounts are authorized. Further, they also indicate difficulties with implementing strategies. For example, using social media to advocate for peace, including greater participation of women, was not always target-oriented (2022-2-Recommendations-I, p. 14) .

The use of all media platforms has increased: In the analyzed documents, the segments focusing on radio and multimedia increased the most, both in total numbers and in the number of documents focusing on the topics. Multimedia is used as a collective term for the media outputs across different modalities to communicate the mission’s strategy ‘in its audio and visual component. It includes the following units: Video – Photo – social Medias and web’ (2020-3-MONUSCO-II, S. 1). One-directional forms of communication are heavily used, meaning that, e.g., top-down communication from UN missions to civilians was prioritized. Among them, radio is the most important, followed by newspaper articles and television productions. This is also evident in the media strategies of POs, as social media content is often integrated into broader audiovisual storytelling. A comparison of trends before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically between the periods 2003–2019 and 2020–2024, shows a notable increase in the use of social media as a communication tool within POs. The results show that the topic of multimedia in the analysis of code frequency has seen an increase of 142.9 %. Audiovisual stories have not been mentioned before 2020; thus, they have seen the strongest increase to 22 % after 2020. This highlights that POs use a multimodal strategy to reach their audience.

Media use is not focused on a specific platform; however, it is mostly top-down: Rather than finding one intensely used platform, media use in the form of distributing multi-media and audiovisual stories is observable across different channels. Looking at social media platforms, the results show that the strategy aims at utilizing a broad spectrum of distribution platforms instead of one. Among the social media platforms which are addressed in the documents, Twitter (now X) is the most prominent one (56 %), followed by Facebook (47 %), a dedicated mission website (38 %), YouTube (31 %), Flickr (31 %), and Instagram 16 %). The use of media is focused on providing access to information as one-directional communication, less on bi-directional communication or on, e.g., enabling self-help communities. The strategies and mission reports also portrayed which societal groups they wanted to reach through their communication. The number of documents that reference citizens as recipients has remained almost the same before (38.2 %) and after 2020 (38.9 %). The second largest recipient group was other authorities, such as host countries, local governments, and security organisations (17.6 % before and 13.3 % after 2020). Even though the strategies continuously stress that SM should be used as a bi-directional channel towards the PO missions, this is not reflected in the documents (2.9 % before and 4.4 % after 2020). Networks of citizens (C2C) are similarly referenced in only a few documents (8.8 % before and 5.6 % after 2020). Looking into identified target groups for strategic communication, the same picture can be observed: across all documents, there are no significant changes before and after 2020, with civil society being named as the most relevant addressee, followed by political actors and other UN agencies, as expressed by this following statement of the MINUSMA report: ‘The Mission enhanced its multimedia and social media outreach through live interactive communications with Malian civil society, community and religious leaders as well as women and young people’ (2021-3-MINUSMA-II, p. 13). ‘For example, the MINUSCA action plan for enhancing peacekeeping-intelligence and early warning capacity establishes priorities and time frames to strengthen capacity across relevant Mission components’ (2023-2-OverallPerformance, p. 17).

Social media approaches adopted by Peace Operations vary: Looking into the individual missions, some variety can be observed regarding the effort and impact of SM engagement. Considerable variation in SM use for strategic communication exists across UN peace operations, with three large missions (MONUSCO, MINUSMA and MINUSCA) accounting for 87 % of the X followers of all African POs. Some missions, like MINUSRO and UNISFA, put little or no emphasis on their SM relations and media output in general (see Table 2). The results show that the number of followers is increasing on a consistent basis for all missions across all social media channels, including Twitter (X), Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube.

Social media channels of active peace operations, including the number of followers. Source: own depiction.

| Mission | Social media channels | Followers (retrieved 8 January 2021) | Followers (retrieved 11 February 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| United nations/African union mission in darfur | X/Twitter (@unamidnews) | 11,481 | 11,953 |

| Facebook/Meta (@UNAMID) | 31,120 | 34,510 | |

| YouTube (UNAMIDTV) | 535 | 613 | |

| Instagram (unamid_photo) | 2,313 | 3,378 | |

| Flickr (UNAMID photo) | 322 | 353 | |

| MONUSCO (Democratic Republic of Congo; DRC) | X/Twitter (@MONUSCO) | 389,035 | 564,608 |

| Facebook/Meta (@monusco.org) | 54,263 | 74,641 | |

| YouTube (MONUSCO) | 3,160 | 7,240 | |

| Instagram (@monuscoindrc) | – | 450 | |

| Flickr (MONUSCO photos) | 349 | 435 | |

| UNISFA (Abyei) | X/Twitter (@UNISFA_1) | 1,450 | 4,389 |

| Facebook/Meta (@unisfa) | 22,100 | 30,790 | |

| YouTube (UNISFA) | 115 | 296 | |

| Instagram (unisfa) | 3,632 | 40,400 | |

| UNMISS (South Sudan) | X/Twitter (@unmissmedia) | 36,368 | 60,388 |

| Facebook/Meta (@UnitedNationsMissionInSouthSudan) | 70,269 | 151,103 | |

| YouTube (UNMISS VIDEOS) | 2,170 | 3,970 | |

| Instagram (unmissmedia) | 1,781 | 6,489 | |

| Flickr (UNMISS) | 154 | 228 | |

| MINUSMA (Mali) | X/Twitter (UN_MINUSMA) | 139,285 | 218,699 |

| Facebook/Meta (@minusma) | 111,148 | 157,045 | |

| YouTube (MINUSMA) | 30,900 | 64,000 | |

| Instagram (un_minusma) | 8,370 | 16,300 | |

| Flickr (UN mission in Mali) | 233 | 277 | |

| MINUSCA (Central African Republic; CAR) | X/Twitter (@UN_CAR) | 25,978 | 43,935 |

| Facebook/Meta (@minusca (unmissions) | 38,568 | 68,000 | |

| Instagram (@un_minusca) | – | 13,900 | |

| YouTube (MINUSCA) | 25,400 | 34,800 | |

| Flickr (UN mission in the Central African Republic MINUSCA) | 152 | 246 | |

| MINURSO (Western Sahara) | Instagram (@minurso_official) | 1,435 | |

| Flickr (MINURSO official) | 11 |

4.2 RQ2: media strategies used by peace operations

To address RQ2, the strategies and purposes of the media usage were coded and grouped into categories that focus on (1) providing information on the mission, (2) crisis response, (3) fact-checking and combatting disinformation, (4) gaining situational awareness on the local level and (5) having access to early warning networks, or holding POs accountable or document local outbreaks of violence.

Providing information on the mission and its mandate: The use of SM as one form of strategic communication is justified in the earlier documents to increase outreach and engagement (2018-3-UNMIL-II p. 3). The overall aim of the SM use of POs aligns with the findings on mostly top-down communication in Section 4.1, as public relations has been named as the most relevant aspect of 18 % of all mentioned aims. The POs follow a media strategy that provides information on their mandate through various media channels and forms. The media strategies aim ‘to promote the mission’s mandate to audiences […], including such civil society organizations as youth and women’s groups and faith-based organizations’ (2020-3-UMISSBudget, p. 28). In doing so, they inform the population of the implementation of the Peace Agreement, to ‘prepare for and build an understanding of the electoral process, to explain the mission’s mandate and its actions and to strengthen its monitoring of the media for hate speech’ (2020-3-MINUSCA-I, p. 13). Thus, the communication strategy ultimately supports the overall goal of the mission by highlighting its ‘contribution to regional stability’ (2023-3-MINURSO, p. 23).

Strategic communication: Strategic communication is considered part of crisis management, as it is ‘crucial to securing support, managing expectations, responsibilities and capacities, and highlighting the contributions of peacekeeping to peace and stability’ (2023-3-UNMISS-I, p. 15). The strategies for effective communication are mentioned in relation to specific aims, such as preventing the spread of disinformation as in the case of COVID-19 (2020-3-MINUSMA-I, p. 13). Within the guidelines for the Protection of Civilians in United Nations Peacekeeping, it is stated that the coordination of the key messages across all channels is the most important. Further, the channels include SM platforms, press releases, radio/TV programming (e.g., as in local stations), radio and video statements by the key staff, and in severe and urgent cases, text messages (2020-2-ProtectionCivilians, p. 73).

Fact-checking and providing education: The mission’s second most relevant aims are to educate and prevent the spread of disinformation. Education is directly linked to the peace process, as it provides information on peaceful political processes and POs mandates, it is also important to prevent the spread of disinformation for effective crisis management and to enhance trust in authorities. As a response to being targeted by disinformation campaigns, POs have increasingly adapted their media strategies. For instance, MONUSCO has worked to strengthen the capacity of journalists and youth leaders to counter false narratives and supported influencer networks to share prebunking content (2023-3-MONUSCO-X, p. 14f.). Education is used to support the local peace processes by raising awareness on ‘the status of women and girls; traditional practices; health and hygiene customs; refugee rights, voting, and civic responsibilities’ (2018-3-UNMIL-I p. 3). However, social media platforms are also considered sources for gaining insights into local sentiments or even as part of the early warning infrastructure.

Gaining insights into situational awareness: Monitoring and assessing the situation is portrayed to serve several aims: First, the missions are interested in understanding the local situation or even have access to early warning in cases of violence between armed groups or against the civilian population: ‘The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali is using machine learning to analyze radio data to detect hate speech, serving as an automated early-warning system for unrest’ (2021-2-UNPO, p. 3). Local staff or CANs are used (2020-2-ProtectionCivilians, p. 97). The missions, however, use as many different sources as possible, which includes monitoring social media, newspapers and local radio broadcasts for the occurrence of hate speech: ‘MINURSO continued strengthening its analysis and early warning capabilities by monitoring information derived from SM and, [.] from local communities, in addition to information provided by the mainstream media’ (2020-3-MINURSO, p. 9). On an international level, the UN has introduced SPARROW, a tool to monitor UN member states to gain insights into political positions and trending themes. Additionally, AI is used to transcribe, translate, and detect hate speech within radio broadcasts in MINUSMA (2021-2-UNPO, p. 3). The second aspect in the monitoring context is evaluating the perception of the PO mission itself. Here, the missions use surveys or conduct sentiment analysis towards their work:

One of the things that matters most is the monitoring of social media, and MONUSCO colleagues now have fortnightly reports each month to see the trends and the discussions related to MONUSCO and with the support of colleagues here in at UNHQs in New York, they are really helping us in shaping in a certain way, the narrative about what the Mission is doing and what the Mission is not about (2023-1-MINUSCO-II).

For this, MONUSCO hired specialists to monitor SM campaigns and to counter ‘harmful misinformation campaigns, notably those that are created to harm the reputation of the mission’ (2023-3-MONUSCOBudget-II, S. 15).

Collecting evidence of violence and holding POs and security agencies accountable: Even though SM is analyzed to gain insights into the population’s sentiment or as part of community alert networks, little is said about the ability to use SM as a tool for holding local leaders accountable or for documenting crimes against civilians. Only UNMISS has issued that SM is used as part of a complaint system, which helps civilians to complain about the misconduct of peacekeepers (2021-3-UNMISS, p. 14).

4.3 RQ3: challenges for social media use in peace operations

The challenges were coded and grouped into co-occurring impediments to answer the third research question. Their order follows the frequency of the codes, showing that disinformation and hate speech have been mentioned 90 times as the most frequent challenges (see Table 4, Appendix). This is followed by language barriers, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, broken-down or missing infrastructure, and difficulties based on the occupation of territory or autocratic political leaders, which limit the freedom of the press and participation of groups.

Monitoring and countering of hate speech: The most frequent challenge for the missions (MINUSCA, MINUSMA, MONUSCO, UNMIL, UNISFA, UNMISS) is the distribution of hate speech. The POs have detailed how hate speech and related disinformation has undermined peacekeeper security – fueling hostility among local populations, inciting threats of violence, and increasing the risk of attacks against mission personnel: ‘Forces in Sevaré [town in Mali], allegations and fake news on the role of the Mission contributed to heightened anti-MINUSMA rhetoric, including calls for violence against MINUSMA staff and premises, mainly conveyed through social media’ (2023-3-MINUSMA-III, p. 7). Men and women advocating for women’s rights are mentioned as a frequent target of hate speech, ranging from defamation to the incitement to violence by UNMIL (2022-1-UNMIL, p. 5). Hate speech is often named alongside disinformation and in numerous cases leading to incidents of physical violence (2022-3-UNISFA, p. 15). This is especially prevalent before elections (2023-3-MONUSCOBudget-I, p. 14, 2023-3-MINUSCA-II, p. 5). Therefore, the UN has identified the challenge across missions and offers ‘practical, direct support to missions to develop policy, guidance and training and to roll out’ (2023-3-UNMISS-I, p. 15). The efforts, however, are not always seen as successful, as observed by the Office of Internal Oversight Services, which criticizes that the coordination of the various mission stakeholders needs to be enhanced to improve effective counter-messaging (2024-3-OIOS, p. 14). The involvement of different stakeholders to counter disinformation has been acknowledged as well in MINUSMA: The mission acknowledges the importance of a holistic approach to countering disinformation, emphasizing collaboration with diverse stakeholders, strengthening partnerships, and fostering meaningful engagement with grassroots communities. Furthermore, the mission plans to ‘foster a more systematic use of technological tools to monitor, analyze, anticipate and address misinformation and disinformation targeting the Mission’ (2023-3-MINUSMA-II, p. 15).

Illiteracy and language barriers: The UN Secretariat’s 2019 bulletin emphasizes multilingualism as a core value, recognizing the importance of communicating with people in their own languages. When establishing institutional social media accounts, consideration should be given to the General Assembly’s directive to ensure full parity among the six official UN languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish) in the use of new communication tools such as social networks (2019-2-UseofSM, p. 2). In addition to the official languages, the missions aim to share their communications in the different local languages (MINUSMA, MONUSCO, UNMISS). In the case of MONUSCO, monthly filmed plays serve the function to explain the mission’s mandate in all local languages (2020-3-MONUSCO, p. 1). Illiteracy is further acknowledged and addressed by the multi-modal media strategy through radio broadcasts (2019-3-MINUSMA, p. 4, 2023-3-UNMISSBudget, p. 19, 2021-3-MONUSCOBudget, p. 43). Illustrative of this approach is MONUSCO’S “Radio Okapi”, which provides a wide range of programs from news to entertainment in four local languages (2020-3-MONUSCO-I, 2).

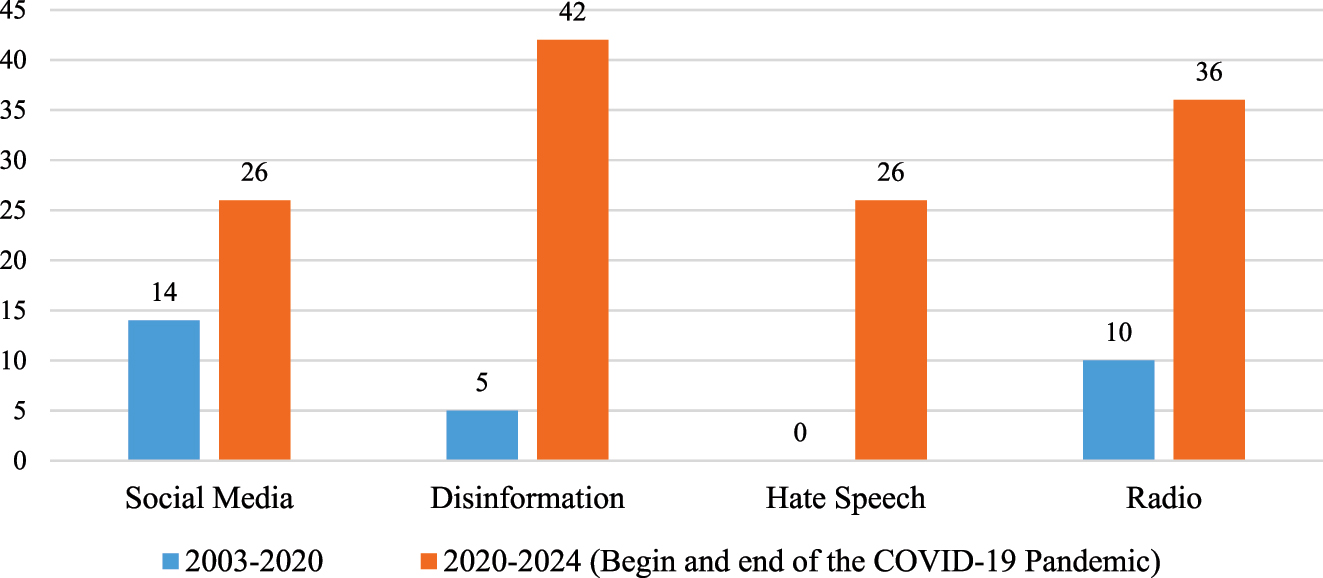

COVID-19 pandemic as a challenge: The COVID-19 pandemic greatly affected the work of the POs, as it made fulfilling their mandate more challenging due to restrictions on meetings and movements (2021-3-MINUSCA-II, p. 15). Therefore, the Department of Peace Operations launched a UN wide initiative to ‘(a) supporting national authorities; (b) protecting United Nations personnel; (c) mitigating the spread of the virus and assisting in the protection of vulnerable communities; and (d) ensuring operational continuity in the implementation of their mandates’ (2020-2-Recommondations, p. 3). The pandemic affected the civilians’ security in the mission areas. Vulnerable groups, like children, suffered from school closure, which resulted in a lack of access to free school lunches or education. Therefore, UNISFA provided psychological support and supported remote learning via their radio Abyei FM (2020-3-UNISFA, p. 8). Additionally, the POs increased their ICT infrastructure and services for online meetings and remote work (2021-3-MINUSCA-II, p. 15). The pandemic also increased the awareness of disinformation and hate speech as an obstacle to peacekeeping. Looking at the frequency of codes per document, it becomes apparent how much the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated SM as a topic, as well as the relevance of other forms of information dissemination, like radio (see Figure 3). Overall, the figure shows, how much more hate speech and disinformation has become a challenge and therefore have changed the relevance of providing access to accurate information.

Main results of the frequency analysis of documents containing the codes before and after COVID-19. N = 126, source: own depiction.

Infrastructure: The second most prevalent topic of discussion was the allocation of financial resources to the missions for communications and information technology equipment, which has been acknowledged by the UN Security Council in their report on the POs performance: ‘Planning, data management and analytical capacities have often been underresourced’ (2023-2-OverallPerformance, p. 20–21). The resources are used not only for the strategic communication units but also to provide communication infrastructure. Some of the missions take place in rural areas, which lack internet or TV access or have broken-down infrastructure due to violent conflicts. Therefore, POs are prepared to build infrastructure and use their resources to provide access to local communities, e.g., by building mobile radio stations or providing access to the internet: ‘UNISFA Field Technology Services team increased the capacity of its alternate Internet service provider to ensure communications at all sites even in inclement weather. To enhance information sharing with the local community and act as an early warning system, the team worked with United Nations police to provide means of communication to local communities (2020-3-UNISFA, p. 12).’ However, collaboration with the host countries can also be challenging for the missions, e.g., in the case of authoritarian governments and human rights violations.

Human rights violations, repression, and occupation: In the POs MINUSMA and UNMISS, the government actively opposes peace efforts and violates human rights by detaining opposition leaders or journalists (2024-3-UNMISS-II, p. 11). In the case of MINUSMA, a leading spokesperson was forced to leave the country as retaliation for a SM post on the detention of 49 Ivorian soldiers (2022-3-MINUSMA-II). The suppression of civilian voices and participation, however, is not only enacted by governments but also by armed groups, e.g., in the case of Central Africa, where different groups fight for regional influence (2021-1-MINUSCO, p. 1). Further, the missions are faced with structural biases in their early warning networks, as there is highly unequal access to digital resources. Therefore, SM analytics as a tool for early warning and sentiment analysis underlie great limitations: ‘Regarding the social media analysis, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, and South Sudan have a significant digital divide in mobile connectivity. Therefore, the social media in these countries may represent the views of considerably small population groups’ (2022-2-Recommendations-I, p. 6).

5 Discussion

Social media platforms are often regarded as effective tools for enabling multi-directional communication and fostering user engagement. 71 However, the findings of this analysis indicate that the POs under study tend to predominantly use these platforms for one-way, top-down communication, rather than taking advantage of their interactive and participatory potential. In the following, relevant communication patterns in relation to crisis communication and peacekeeping will be discussed, and further implications are outlined.

5.1 The role of social media in peace operations’ crisis communication

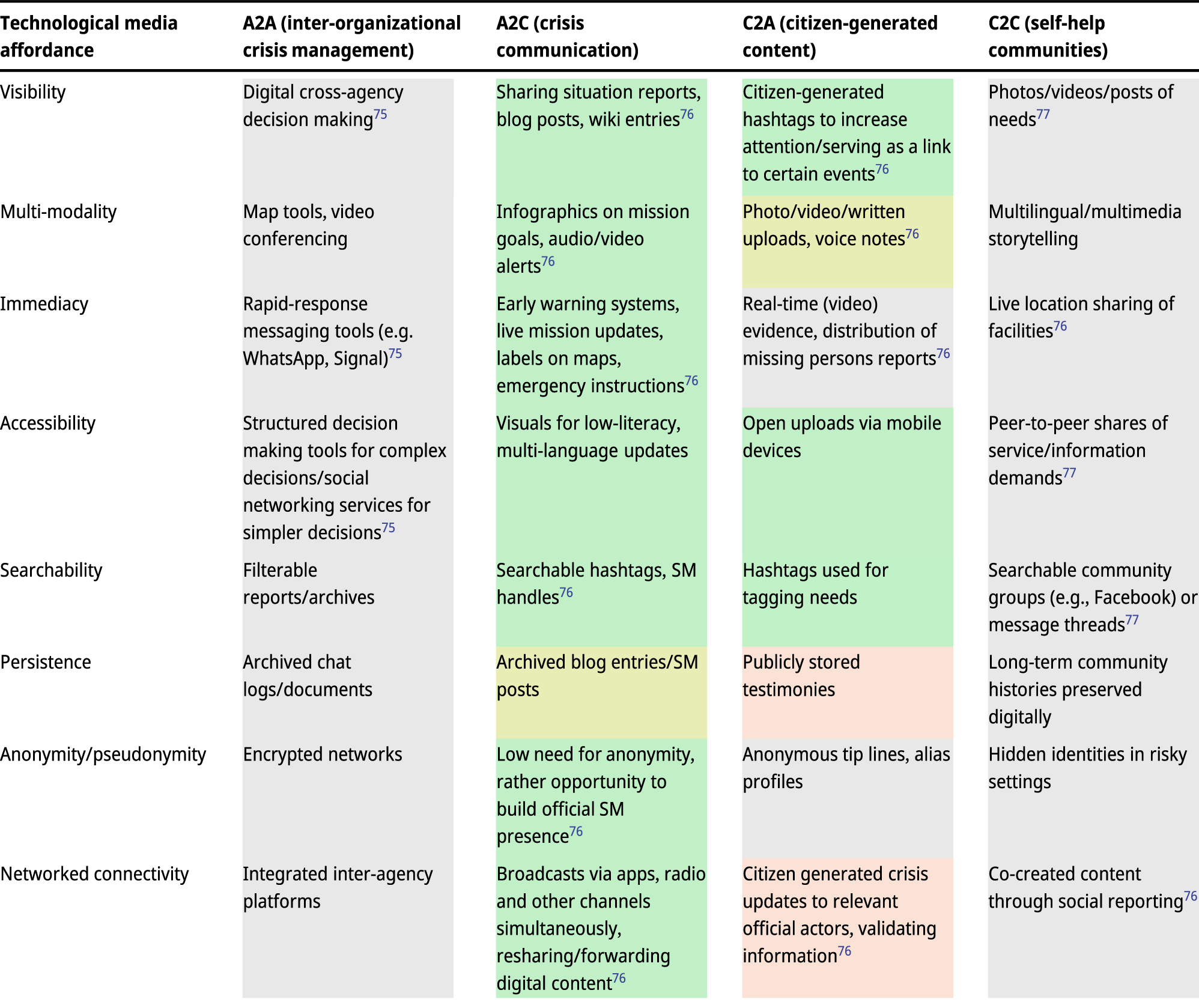

Effective crisis communication is vital for POs to achieve their mandates, and numerous affordances of ICTs, such as visibility, multimodality, and persistence, can be leveraged to support these objectives. 72 , 73 On social media, affordances do not function in isolation; their meaning emerges through the ways users engage with them within a specific social and cultural context. 72 Knorr 74 highlights that there are two types of affordance: (1) technological-subjective, focusing on technical features and individual perception; and (2) social-communicative, focusing on social contexts and potential uses. Looking into related work with regard to affordances of SM use in organizations and in crisis communication, we can map the technological-subjective affordances, as well as the technological functionalities that support them on the crisis communication matrix 31 (see Table 3).

Non-exhaustive examples of social media functionalities enabling affordances across communication types in peace operations. Green: strong presence, observed or explicitly mentioned in mission reports (4 or above POs). Yellow: moderate presence, occasionally implied or indirectly referenced (2–3 POs). Red: low presence, largely absent or unaddressed in the reports (0–1 POs). Grey: no information found in mission reports. Source: own depiction.

|

The interaction in crisis communication is achieved by particular social media affordances and corresponding functionalities. However, as shown in the grey fields, not all existing functionalities are used by the POs to enable bi-directional communication, and thus some affordances remain as potential, especially regarding C2C and C2A. The identified affordances are color-coded in green, yellow, or red, reflecting the degree to which they occur in the analyzed UN PO documents. Table 3 shows that technological affordances are particularly prevalent in A2C, followed by C2A. While the functionalities from the documents demonstrate that for A2C almost all affordances are supported, for C2A it is focuses on visibility, accessibility, and searchability.

For the core objective of POs – namely, disseminating information about their missions – affordances like visibility, accessibility, and persistence are crucial. These affordances ensure that content can be widely and rapidly distributed, thereby reaching a broad audience of social media users, as for mass communication and education, by providing audio-visual stories and input. Actual interaction, in the form of reposting, likes, and comments, is rarely monitored or addressed by strategies for engagement by POs in their reports. This could have a variety of reasons: Firstly, POs address a wide range of ICT formats in addition to SM, including TV and radio. In some cases, they also establish the necessary infrastructure, as evidenced by the establishment of their own radio stations and media outlets, utilizing a variety of media forms across multiple channels.[3] This is done, while the financial resources for their communication work are highlighted as scarce and challenging. Further, it might be dangerous for citizens to engage in SM discussions or to post content based on the nature of the conflict. 78

Social media platforms provide citizens with a structured means of expressing critique, coordinating political action, and organizing protests, as well as sharing experiences. 74 However, the POs focus on the representation of the mission and its mandate, most importantly, thereby possibly neglecting opportunities of engaging in societal discourse. African POs are endeavoring to incorporate a variety of communication channels, such as radio and social media platforms, into their crisis communication strategies. This objective is driven by the desire to facilitate effective communication and the dissemination of information to the public during times of crisis. In this way, they can communicate behavioral instructions in emergencies and improve the transparency of their actions. In contrast, the analysis reveals that SM is primarily used by POs for public relations to legitimize their mandate by informing about mission progress and countering disinformation in social forums. This is a phenomenon that can also be observed in other contexts, such as Colombia, where transitional justice institutions mainly use social media for PR purposes. 79 Gordon and Young 80 and Cooley and Jones 40 highlight that informing the public about the progress and mission objectives of the mission contributes to building a foundation of trust among the population, which is indispensable for crisis management.

Following the understanding of Knorr 74 that affordances need to be realized through a user’s interaction, their missing realization might have the following reasons: They are structure-dependent, socially mediated, and bound to institutional logics. While the documents analyzed did acknowledge the importance of information sharing between POs and citizens, specific strategies to engage citizens were not mentioned. To effectively involve citizens in digital crisis communication, numerous factors, including (1) inclusivity, i.e. ensuring that communication is accessible to diverse groups and often marginalized populations (e.g., cheap access to the internet and a mobile device; providing information in multiple languages, accessible forms and through different digital platforms; improving digital literacy), 81 (2), considering local context (cultural, political, and socio-economic factors), 82 (3) the willingness of citizens to engage through digital tools, (4) offering participatory approaches, including forms of two-way communication, (4) transparency and trust, i.e. that citizens need to feel the information shared is accurate and that the information provided by them is being considered, 83 and (5) continuously monitoring online platforms for feedback to quickly identify citizen’s concerns, need to be considered. 84 There are structural factors that hinder the realization of the SM affordances for more interaction, such as low trust in political institutions, 80 , 85 authoritarian or oppressive regimes, 86 as well as security concerns. 78 A considerable number of African citizens hold their governments and officials in low esteem due to weak institutions and economic inequities resulting from colonial legacies and exploitation. 85 The perception of these institutions, such as POs influences the willingness of the population to cooperate with them as Gordon and Young 80 have shown in their study on the MINUSTAH mission in Haiti. They have shown that reports on abusive behavior from the mission reduced the cooperation efforts, highlighting that “public opinion and cooperation are responsive to peacekeeper policy, then peacekeepers must deliver services and prevent abuse in order to solicit the cooperation that is necessary for mission success”. 80 Transparency International 87 shows that fragile, authoritarian states and conflict regions are most likely to rank among the last by perceived public sector corruption (the scale ranges from 0, highly corrupt, to 100, very clean). South Sudan ranks in the bottom three of Transparency International’s Index. 87 This has been challenging for the POs, like UNMISS, as it also potentially undermines trust in them and reduces the likelihood that people report crimes, making the ability to mediate in conflict more difficult. 87 Mistrust and corruption affect the public’s confidence in the crisis management of their governments, and a general distrust of authority prevails in many operating areas. POs need to gain the population’s trust for effective crisis communication, which so far commonly seems to focus on top-down communication. Given citizens’ limited use of technical tools, relying on radio broadcasts and local-level engagement for crisis communications makes sense in terms of reaching citizens through media they are familiar with. Consequently, involving such leaders in communicating with citizens can help POs’ crisis communication become more efficient.

This is not always favored by political leaders or opposing political groups and has led to conflicts with the POs. POs have been subjected to disinformation campaigns followed by physical violence against peacekeepers. Therefore, it has become an important part of the communication strategy to combat and monitor disinformation and hate speech. This is conducted in forms of media monitoring, e.g., for the sentiment of newspapers, social media, and radio, which can be improved in the future based on research on hate speech detection and moderation. 65 , 88

5.2 Social media for a sustainable peace process

In the peace begins with you campaign, the UN has restated its commitment to fight hate speech. The UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said: ‘Hate speech is an alarm bell–the louder it rings, the greater the threat of genocide. It precedes and promotes violence’. 89 The UN has recognized the policy shift of international social media platforms on their hate speech policies. The strategy is to remain on the platforms for the moment to provide fact-based and reliable information, as well as to hold its course in the digital space. 90 This also highlights that hate speech is a global phenomenon, independent of POs. However, its destructive effects become clearest in the context of armed conflicts, where there is already a danger of the outbreak of group-based violence with the potential to enable genocide. This shows that there is value in automated approaches to hate speech detection, 91 as well as moderation. 92

A sustainable peace process needs inclusive and participatory elements beyond one-way communication because mutual understanding, trust-building, and the inclusion of diverse voices, especially those from marginalized communities, are essential for addressing the root causes of conflict, ensuring legitimacy, and fostering long-term social cohesion. 93 Based on the social affordances for digital peacekeeping, Hirblinger 50 criticizes the “sincere” mode in digital peacebuilding, which refers to POs primarily capturing the reality with their use of SM by using it either for monitoring (big data, conflict mapping, surveillance) or the distribution of information as “truth” or counter narratives to disinformation. Among the affordances for digital peacekeeping, digital communitas can be found in the results. It refers to the way in which SM can help to foster communities and create groups based on common interests. 50 Networked connectivity and collaboration can create value, not only for crisis response, but for the peace process. The high relevance of mainstream media and, in particular, the importance of broadcasting can be explained, amongst others, by the long history of UN radios. 94 Moreover, the advantages of using SMS and cell communication for crisis communication in African countries still play a dominant role as a facilitator of news, as an often-shared resource. Thus, in some regions, it might even be more genuinely social than internet-based technologies.

However, the social affordances for peacebuilding of digital detachment and imagining futures can be found in the educational offers by POs. Digital detachment allows the conflict parties to detach by organizing the way information is released, e.g., on atrocities or with regard to sensitive information. 50 Although this has not come up in the document analysis, one could argue that forms of detachment can also be found in shifting the focus of the public, e.g., by offering education and entertainment through the UN POs channels. In reframing and imagining futures, educational offers by the POs can tie into a reframing of the conflict understanding, as they offer insights into the long-term effects of the conflicts or the aims of the peace process, e.g., by supporting women’s rights and participation. 50 Approaches towards a collaborative creation of a peaceful future are still missing, as crisis communication literature is sufficient to understand aspects regarding the management and collaboration of citizens and authorities, if there is sufficient trust between the groups. The existing strategies that aim at political participation supersede most crisis informatics cases from the literature, which focus on individual crisis events and clear crisis response and management phases. The POs not only need crisis communication for coordination but also aim to strengthen societal peace processes with long-term goals of providing information, education, and equal access to civic participation, e.g., for rural areas or discriminated groups. Lastly, digital shepherding, as the use of SM to monitor hate speech and misinformation as indicators for violent outbreaks, can work towards a Panopticon effect. Surveillance technologies can, hence, be effective in supporting adherence to ceasefires or preventing violence; however, this was not discussed in the documents.

The strategic utilization of social media, when employed judiciously and when citizens demonstrate a willingness to engage, has the potential to serve as a catalyst for the resolution of this disparity by facilitating two-way communication, thereby enabling citizens to articulate their concerns, offer feedback, and collaborate in the construction of peace initiatives. 23 , 46 , 49 Critical examination of crisis communication is essential, particularly concerning whether authorities, in this context representing the UN, employ a top-down approach to disseminating information. This examination is of particular significance given the substantial influence that the manner of information sharing has on the efficacy of peacekeeping endeavors. The results of the study indicate that crisis communication frequently adopts a top-down structure, wherein POs assume the role of disseminating information to the public. The efficacy of this approach is evident in specific circumstances, such as providing clear instructions during a crisis or managing disinformation. However, this approach can also create challenges in POs, especially in regions characterized by profound mistrust between authorities and the public. Furthermore, for achieving sustainable peace, the involvement of local communities is imperative, 95 and thus, it is crucial that communication not only conveys the authority’s messages but also involves listening to and engaging citizens. POs should use the ability of citizens to detect, measure, and report local emergency information during and after an event to improve their situational awareness. Technological advancements are enabling more people to respond cooperatively to crises.

5.3 Limitations and future work

Although this research could provide valuable insights into using ICTs in POs in African countries, it has some limitations. As described in Section 3, the selection of documents was based on certain pre-determined keywords on official UN and UN PO websites. Consequently, the findings of this study are based exclusively on the analysis of official UN documents identified according to the pre-determined selection criteria and are selective rather than all-inclusive. Thus, only the official UN perspective is examined and does not include independent measurement of SM interactions. Researching interactive patterns of communication between authorities (A2A) as well as between citizens (C2C) is, therefore, a venture point for future research. However, as Coe and Nash 96 show, sub-regional and regional organizations play a vital role in engaging in peace and security. It also needs to be considered that the facts presented in the guidelines and reports are not necessarily objective but should be examined from the perspective of an international organization. The regional challenges outlined here are generalized and cannot be fully applied to every country or region of operation. Therefore, it is crucial to analyze the specificities of each country and mission to address the challenges adequately.

6 Conclusions

The analysis of the documents reveals that POs focus on one-directional communication when using SM. The focus is on presenting the mission and its mandate. Nevertheless, security and stability-related aims, such as countering hate speech and disinformation, have become central elements. The main findings are:

Social media is predominantly used in POs to disseminate crisis information to affected citizens: SM has so far been used by POs mainly for transmitting information and less for acquiring information. Top-down communication from POs to citizens can be divided into three purposes: (1) Legitimizing the mandate to protect civilians, (2) combating disinformation spread on SM, and (3) transmitting crisis-related information. However, POs use SM as part of a diversified communication strategy that is not limited to a single way of dissemination or platform.

Potentials for interactive communication: The discussion of the SM affordances has shown that, apart from monitoring citizen-created content, peacebuilding could make use of the affordances that support connectivity, empathy, and shared imagination of a better future. ICTs are already used in citizen journalism or activism on a citizen-to-citizen (C2C) level. Actively including while also protecting citizens’ voices and safety against physical and digital attacks can help strengthen people’s trust in the mission and its goals, especially when trust has been lost due to human rights violations and corruption.

The use of ICTs in POs is linked to specific regional challenges: A multitude of factors, including but not limited to a paucity of financial resources and the inadequate coverage of internet and electricity, result in unequal access to mobile communication and ICTs among the population. This could lead to disadvantages for some population groups, especially those who are already often marginalized. Addressing the issue of unequal access to digital infrastructure is imperative for authorities, who should endeavor to establish effective integration mechanisms that foster inclusive participation among all segments of the population. At the same time, POs should continue to rely on established communication channels (e.g., radio) to transmit information in times of crisis, reaching the widest possible number of people. Moreover, when using ICTs for security aspects, such as warnings about violent clashes, one should consider the potential for abuse by government agencies. POs, thus, should contemplate offering their own tools to ensure the neutrality and credibility of their communication.

Funding source: German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and the Hessian Ministry of Higher Education, Research, Science and the Arts

Award Identifier / Grant number: National Research Center for Applied Cybersecurity

Funding source: Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung

Award Identifier / Grant number: 01UG2203E

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kajsa Wysujack for her invaluable support and insightful feedback during the preparation of the manuscript. Furthermore, we would like to thank our funders for their financial support.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Grammaly and DeepL Write was used for language editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This contribution was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as part of TraCe ‘Regional Research Center Transformations of Political Violence’ (01UG2203E) and by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and the Hessian Ministry of Higher Education, Research, Science and the Arts within their joint support of the National Research Center for Applied Cybersecurity ATHENE.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

Absolute frequency of codes in relation to challenges. Source: own depiction.

| Challenges and limitations | 2003–2020 | 2020–2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fake news/disinformation | 7 | 65 | 72 |

| Hate speech/discrimination | 0 | 30 | 30 |

| Budget | 7 | 22 | 29 |

| Infrastructure | 12 | 18 | 30 |

| Human rights violations | 4 | 12 | 16 |

| COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 10 | 11 |

| Cyberattacks/data security | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| ICT skills deficiency | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Occupation by militant groups | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Gender discrimination | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Language barriers | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Repression by authoritarian governments | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Misuse of social media | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Ineffective communication | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Illiteracy | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sum | 55 | 186 | 241 |

| N = documents | 34 | 92 | 126 |

List of used documents. Source: own depiction.

| Number | Mission reports | Guidelines | News reports |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 2020-3-AMISON | 2021-2-Annual Report | 2023-1-Digital Education |

| (2) | 2018-3-AMISON-XI | 2023-2-Information Integrity Platforms I | 2023-1-Fake News Kenya |

| (3) | 2018-3-AMISON-III | 2023-2-Information Integrity Platforms II | 2016-1-Secretary General |

| (4) | 2018-3-AMISON-II | 2012-2-Joint Mission Analysis Centres | 2023-1-Preventing Genocide |

| (5) | 2018-3-AMISON-I | 2022-2-Mid Year Report | 2023-1-Protests Algeria |

| (6) | 2017-3-AMISON | 2003-2-Multidimensional Peacekeeping | 2024-1-Sudan/South Sudan |

| (7) | 2023-3-MINURSOBudget | 2023-2-Overall Performance | 2023-1-Somalia/Sudan |

| (8) | 2022-3-MINURSOBudget | 2014-2-Performance Peacekeeping | 2023-1-Sudan Crisis |

| (9) | 2021-3-MINURSOBudget | 2015-2-Politics, People, Partnership | 2023-1-Sudanese Refugees |

| (10) | 2020-3-MINURSOBudget | 2020-2-Protection Civilians | 2023-1-Tanzanian Radio |

| (11) | 2023-3-MINURSO | 2020-2-Recommondations | 2020-1-Terrorism |

| (12) | 2022-3-MINURSO | 2019-2-Recommondations | 2021-1-Uganda |

| (13) | 2021-3-MINURSO | 2022-2-Recommondations-I | 2020-1-MINUSMA |

| (14) | 2020-3-MINURSO | 2022-2-Recommondations-II | 2021-1-MINUSCO |

| (15) | 2024-3-MINUSCA | 2013-2-Report of SG | 2019-1-MONUSCO |

| (16) | 2023-3-MINUSCA-III | 2023-2-Strategic Communication | 2022-1-UNMIL |

| (17) | 2023-3-MINUSCA-II | 2006-2-Strategies for Media & Communication | 2020-1-UNMIL |

| (18) | 2023-3-MINUSCA-I | 2018-2-Strategy New Technology | 2023-1-UNPeacekeepers |

| (19) | 2022-3-MINUSCA-III | 2021-2-UNPO | 2020-1-UNPeacekeeping-I |

| (20) | 2022-3-MINUSCA-II | 2004-2-Use of ICT Guidelines | 2020-1-UNPeacekeeping-II |

| (21) | 2022-3-MINUSCA-I | 2019-2-Use of SM | 2019-1-UNPeacekeeping |

| (22) | 2021-3-MINUSCA-II | 2018-1-UNPeacekeeping | |

| (23) | 2021-3-MINUSCA-I | 2022-1-UNMISS | |

| (24) | 2020-3-MINUSCA-III | 2020-1-UNMISS | |

| (25) | 2020-3-MINUSCA-II | ||

| (26) | 2020-3-MINUSCA-I | ||

| (27) | 2023-3-MINUSMA-III | ||

| (28) | 2023-3-MINUSMA-II | ||

| (29) | 2023-3-MINUSMA-I | ||

| (30) | 2022-3-MINUSMA-II | ||

| (31) | 2022-3-MINUSMA-I | ||

| (32) | 2021-3-MINUSMA-II | ||

| (33) | 2021-3-MINUSMA-I | ||

| (34) | 2020-3-MINUSMA-II | ||

| (35) | 2020-3-MINUSMA-I | ||

| (36) | 2019-3-MINUSMA | ||

| (37) | 2017-3-MINUSMA-II | ||

| (38) | 2017-3-MINUSMA-I | ||

| (39) | 2016-3-MINUSMA | ||

| (40) | 2023-3-MONUSCOBudget-II | ||

| (41) | 2023-3-MONUSCOBudget-I | ||

| (42) | 2022-3-MONUSCOBudget | ||

| (43) | 2021-3-MONUSCOBudget | ||

| (44) | 2023-3-MONUSCO-X | ||

| (45) | 2023-3-MONUSCO-IX | ||

| (46) | 2023-3-MONUSCO-II | ||

| (47) | 2023-3-MONUSCO-II | ||

| (48) | 2023-3-MONUSCO-I | ||

| (49) | 2020-3-MONUSCO-II | ||

| (50) | 2020-3-MONUSCO-I | ||

| (51) | 2017-3-MONUSCO | ||

| (52) | 2016-3-MONUSCO | ||

| (53) | 2014-3-MONUSCO | ||

| (54) | 2012-3-MONUSCO-II | ||

| (55) | 2012-3-MONUSCO-I | ||

| (56) | 2024-3-OIOS | ||

| (57) | 2023-3-UNISFABudget | ||

| (58) | 2020-3-UNISFABudget | ||

| (59) | 2023-3-UNISFA | ||

| (60) | 2022-3-UNISFA | ||

| (61) | 2020-3-UNISFA | ||

| (62) | 2018-3-UNMIL-III | ||

| (63) | 2018-3-UNMIL-II | ||

| (64) | 2018-3-UNMIL-I | ||

| (65) | 2024-3-UNMISS-II | ||

| (66) | 2024-3-UNMISS-I | ||

| (67) | 2023-3-UNMISSBudget | ||

| (68) | 2023-3-UNMISS-II | ||

| (69) | 2023-3-UNMISS-I | ||

| (70) | 2022-3-UNMISS | ||

| (71) | 2021-3-UNMISS | ||

| (72) | 2020-3- UNMISSBudget | ||

| (73) | 2013-3-UNMISS | ||

| (74) | 2020-3-UNSOM | ||

| (75) | 2017-3-UNSOM |

List of codes. Source: own depiction.

| Code | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Data type | 1 |

| Satellite imagery | 3 |

| Geospacial | 9 |

| Text | 7 |

| Audio | 31 |

| Pictures | 27 |

| Audiovisual stories | 21 |

| Video | 22 |

| Challenges/limitations | 2 |

| Lack of engagement | 1 |

| Ineffecive communication | 5 |

| Cyberattacks/data security | 11 |

| Institutional hurdle | 3 |

| Lack of budget | 28 |

| Fake news/Misinformation | 90 |

| ICT skills deficiency | 13 |

| Hate speech/Discrimination | 32 |

| Gender discrimination | 3 |

| COVID-19 pandemic | 13 |

| Language barriers | 7 |

| Human rights violations | 18 |

| Occupation by militant groups | 6 |

| Repression by authoritarian governments | 3 |

| Illiteracy | 1 |

| Infrastructure | 32 |

| Misuse of social media | 5 |

| Level of application | 0 |

| Religious leaders | 1 |

| Locals | 12 |

| Journalists | 11 |

| Political actors | 17 |

| Peace operations | 44 |

| Terrorist groups | 9 |

| Mass media | 6 |

| International organizations | 3 |

| UN agencies | 15 |

| Civil society | 32 |

| Communication modes | 0 |

| 1 | |

| Podcast | 1 |

| TV | 5 |

| Media/Print | 26 |

| Local level engegements | 10 |

| SMS | 7 |

| Radio | 108 |

| Social media | 61 |

| Multimedia | 57 |

| Type of application | 0 |

| UNiFeed | 6 |

| Broadcast via message application | 1 |

| TikTok | 2 |

| Other | 1 |

| Flickr | 19 |

| 9 | |

| YouTube | 17 |

| 0 | |

| Facebook messanger | 0 |

| 32 | |

| Website | 24 |

| 30 | |

| Digital news stories | 10 |

| (Purpose of) social media use | 2 |

| Engagement | 20 |

| Environmental | 5 |

| E-learning | 6 |

| Public relations | 67 |

| Projectmanagement tools | 10 |

| Documentation | 5 |

| Accountability | 2 |

| Clarfication (aufklärung) | 60 |

| Education/Training | 32 |

| Information exchange | 23 |

| Emergency response | 3 |