Representations of love in the early stages of love

-

Ivan Lukšík

Abstract

Love, especially romantic and partnership love, has been a legitimate research theme in social science since the mid-twentieth century. In the research less attention is paid to how personal conceptions of love are formed within specific sociocultural contexts. One question that emerges in relation to social representations theory is: how are ideas about love, or knowledge of love, re-presented among particular social groups and which sociocultural resources are used in the process? In our questionnaire-based research we ascertained which perceptions, ideas and knowledge are prevalent among young people who are gaining their first experiences of partner relationships, what they consider love to be in their own context and what knowledge they have of love. The questionnaire was completed by 268 higher education students, who provided 38 representations of love, based on personal experience and linked to sociocultural sources of love.

Introduction

Love, particularly romantic love and partnership love, has been a popular research theme in social science since the mid-twentieth century. Since then love has been conceptualised and operationalised, and tools have been designed to measure it (Hatfield et al., 2011; Karandashev & Clapp, 2015), while the models have become more complex (e.g. Karandashev & Clapp, 2015). Research has been conducted into the biological aspects of love, such as its links to the stress response system (Mercado & Hibel, 2017). Sociocultural aspects have also been investigated, such as norms scripts, prototypical stories and the ideologies people are thought to draw on when forming their own ideas and stories about love (Giddens, 1992). The psychological research on love is particularly strong (see the overview by Masaryk, 2012). Psychological discussions have tended to focus on the extent to which love is an emotion, what its characteristics are and what its constituent parts might be (Masaryk, 2012). Love has also been considered as a means of self-reflection and identity moulding (Mouton & Montijo, 2017). Also, ideas of love and partnership are studied (Kraft & Witte, 1992). Discursive constructions of love is another research theme (Watts & Stenner, 2013), and some interesting research has been conducted on the neurobiological and psychological contexts of love (Feldman, 2012; Schneiderman et al., 2012). Alongside the more influential theories (Sternberg’s three components of love, which later became the duplex theory of love), provocative ones have emerged, such as “love as the transformative power of being in love” or as “an encounter of myth and drive” (Lamy, 2015)

Less attention has been focused on whether and how personal concepts of love tie into the sociocultural context. We can see how the many concepts, ideas and images of love are created and shared through literary and non-literary media, publishing and social networks. The visual culture created via the mass dissemination of an image-repertoire via the new technologies of image production has led to a “pictorial turn” (Mitchell, 2017) and so, alongside verbal representations, non-verbal representation are becoming important as well. Although Mitchell is right to say that it is misleading to distinguish between “word and image”, since all representations are essentially a mix of the two, he admits the key issue is the power and effect of images (2017).

In our empirical research we concentrated on what young people think of love, how they write about it and whether it is a unique experience or if it is possible to identify any common characteristics. We also looked at whether some of the widespread knowledge, beliefs and myths about love apply to these expressions at the individual or group level. The theoretical framework employed in the research consisted of elements of social representations theory.

Social representations theory and its potential for investigating love

Moscovici first defined social representations as cognitive systems that have their own logic and language. They are systems of values, ideas and practices that have a twofold function: 1. to establish an order which will enable people to orientate themselves in their material and social world and master it; 2. to enable communication among social groups by providing a code for interacting, naming and unambiguously classifying the various aspects of their world and their individual and group history. S. Moscovici also stated that like scientific theories, religions or mythologies, social representations are representations of something else. They have their own specific content and vary in different spheres of life and in different societies. The social representations commonly adopted by a social group help shape that group’s identity (Farr & Moscovici, 1984; Moscovici, 1973). In subsequent definitions Moscovici stressed that the symbolic and cognitive character of social representations is like a model of ideas, beliefs and symbolic behaviour or like culturally created artefacts that give meaning to human activity (Moscovici, 2000). This definition of social representations differs from the definition of mental representations found in cognitive psychology, which largely concerns faithful images of segments of the world in the mind of the individual. I. Marková emphasises that the theory of social representations is based on dialogicality and representations are generated through tensions between the Ego, the Alter (another person, or group or society) and the object of the social representation. In structuring social representations some themata have been determined “essential to the survival and enhancement of humanity” (Marková, 2003, p.188). The so-called ‘basic themata’ are theorised as responding to ‘basic needs’ and ‘social drives’, such as the desire for social recognition, and may be implicated in the generation of many social representations, including those that seem to correspond to disparate phenomena” (Marková, 2003).

Although there are a number of streams within social representations theory we base our research on the work of S. Moscovici and its further elaboration by I. Marková. We concentrate on the socially shared content and form of knowledge and the tensions between these, seeking out the themes around which this knowledge is organised and structured. However, we do not explore the meta-knowledge level disseminated in society, but look instead at the individual social representations operating at the individual level as referred to by Von Cranach (1995). This concept is based on Von Cranach’s distinction between representations at the level of collective and individualized consciousness. The first one concerns social representation and the other individual social representation. We relate these individual social representations to their potential social source (through their social representations).

The theory of social representations and communication is concerned with specific types of representations. It deals with social phenomena that for some reason have become the subject of public interest and around which a theory is being constructed—issues of health and disease or environmental or physical phenomena, for instance. The phenomena that are debated and contemplated generate tension and lead to action (I. Marková, 2003). If love is a social representation, then it follows that it should become the subject of public attention. This is not hard to verify by looking at consumerist non-aesthetic and aesthetic (literary) production. The second supposition is that the representation must be based on a source. This could be a cultural source, a myth, archetypal image, basic topic, or something that is handed down from one generation to the next largely unchanged. Another source of social representations could be scientific sources and popular versions of these, such as Sternberg’s Love is a Story, Fromm’s The Art of Loving. another potential source is a dialogue between the Ego, Alter (another person, group or society) and the object of the social representation, or in our case love (I. Marková, 2003)[2]. It follows from this that discussing and writing about love should communicate something, generate something before our eyes and in our mind (which, is the French interpretation of representation, according to I. Marková, 2003).

Sociocultural sources of love

If we begin from the fact that, when forming their own ideas and knowledge of love, young people make use of sociocultural sources, then we have to ask what these might be. There is an abundance of sources. To start with there is the literature on this topic found in Slovak libraries (Slovak national bibliography), including genres such as fiction, Christian literature, popular songs, manuals, romances and partner relationships. This area deserves a more indepth analysis; however, for now we shall limit ourselves to three examples: 1. the Western myth of romantic love and its current form 2. the concept of Christian love, likely to be relevant in the sociocultural context of Slovakia, and 3. popular psychology concepts of love.

Western myth of romantic love and its current form

In his important book, Love in the Western World (1972), Denis de Rougemont examined the nature of passion-love (amour passion), which in the Western world has an antagonistic relationship with marital love. De Rougement considers passion and marriage to be incompatible; their parallel existence leads to irresolvable problems and conflicts that endanger “every one of our social safeguards” (de Rougemont, 2001, p. 213[3]). His rejection of adulterous passion-love is based not on the fact that it ignores the moral imperatives of Christian tradition, but on the malignant effects of a burning passion that brings suffering, tragedy and the risk of death. He thought the myth of Tristan and Isolde, with their passionate adulterous love affair and its tragic ending to be crucial in this respect. The persistence of this myth in romances and more recently in films has resulted in Western lyrics being enthused with amorous passion: “it swoops upon powerless and ravished men and women in order to consume them in a pure flame; … it is stronger and more real than happiness, society or morality” (de Rougemont, 2001, p. 21). Yet Western literature tells us nothing about happy love. The force of passion-love derives from the fact that it cannot be fully realised. Its energy grows as it becomes laden with obstacles; all the things that stand in the way of this love simultaneously foster and sanctify it. But de Rougemont also pointed out it was unreal under conditions of liberty: “The spontaneous ardour of a love crowned and not thwarted is essentially of short duration. It is a flare-up doomed not to survive the effulgence of its fulfillment. But its branding remains…”. (de Rougemont, 2001, p. 42).

In his exploration of contemporary forms of love, Giddens introduces a more up-to-date concept: that of “a pure relationship”—a relationship of emotional and sexual equality between partners. The contemporary democratised form of love owes its origins to older concepts. While the passion-love of the past showed itself to be uncontrollable and even dangerous, romantic love was more stable and became an appropriate unit of cohabitation. Romantic love incorporated elements of Christian moral values, absorbing passion-love and becoming a form of cultivated love (Giddens, 1992). It ceased to be an unreal enchantment and became a potential route to controlling the future, a form of psychological security for those entering into it. For the majority of the normal population love was associated with marriage; couples today are increasingly connected in what is referred to as a partnership. Giddens (1992) defines a pure relationship as one “entered into for its own sake, for what can be derived by each person from a sustained association with another; and which is continued only in so far as it is thought by both parties to deliver enough satisfactions for each individual to stay within it”. The distant echoes of romantic love brush up against pure relationships and come together in “confluent love”. This latter involves the partners being open with one another, and it is an active, conditional kind of love. It evolves only to the extent that intimacy evolves; in so far as one partner is prepared to reveal their anxieties and needs to the other, and to expose their vulnerabilities. It and erotic love constitute the core of the relationship and the ability to provide mutual sexual satisfaction within it is decisive, determining whether it continues to exist or to die. In a confluent relationship, erotic love forms the core, and the capacity for mutual sexual satisfaction is crucial, determining its continued existence or demise.

However, research findings (D. Marková, 2012) show that in Slovakia, Giddens’s concept of a “pure relationship” is still by and large an idealistic partner relationship. His premise that pure relationships are not based on external criteria, institutions, exterior norms or duties and dependency, but on mutual feelings and emotional gains does not seem to be an accurate reflection of the Slovak reality. It is true that the research found that partners wanted good quality relationships, communication and so forth, but external criteria, obligations and so on were also relevant, indicating that there is still a tendency to favour traditional relationships in Slovakia. As far as value preferences are concerned, D. Marková (2014, 2015a, 2015b,) found a variety of moral preferences in sexual and partner relationships, but also that the prevailing moral ideal in sexual and partner relations is a relationship based on values such as love, fidelity and responsibility. This ideal also included some of the emotional and relational aspects of Giddens’s partnership, such as emotional understanding, trust, mutual respect, openness, intimacy and closeness.

Concept of Christian love

The concept of Christian love is common in Slovakia. A glance at the Slovak national library catalogues, which contain the most representative collection of publications found in Slovak libraries, shows that Christian love is the second largest theme after literature.

There are two main kinds of love in Christianity: “love thy neighbour as thyself” and marital love. The agape concept of love—love for thy neighbour—comes from the Judaeo-Christian tradition and is found in Islam and Judaism as well as Christianity. The Judaeo-Christian concept of neighbourly love is found in the Old Testament and in the Torah. This basic concept of the value and importance of love for our neighbours is found in all the holy books of these three religions. Nonetheless, it has a specific meaning in Christianity. Agape is described as the love God gives to man first in the expectation that he will give the same love to those around him. In the New Testament love takes on a new quality in the Jewish commandment “love they neighbour”. Here it is no longer simply a command meaning love thy neighbour from the same tribe (Nygren, 1953, Aslanian, 2018), but has been extended to embrace the concept of the universal neighbour. The command to love thy neighbour refers to all “others” and exhorts us to let the differences between us and others dissolve away (Steinhouse, 2013).

According to Možný (1990, p. 64) “the fact that Christianity defined the relationship between husband and wife as love is its most important historical contribution”. Marital love means that a man should love his wife as he does his own body. The man is responsible for his wife’s spiritual wellbeing. Love means taking responsibility for the happiness and therefore the spiritual wellbeing of the other. This kind of love need not be erotic; nor should it be egotistic or hedonistic. But in essence erotic love was driven out of marriage (Možný, 1990).

Popular psychological concepts of love

One of the most important sources of representations of love is psychology, a field where a great deal of research and theorising has been done on love (Masaryk, 2012). In Slovak the psychological aspects of love are most frequently found in the books of E. Fromm, J. Sternberg, J. Willi, I. Štúr, M. Plzák, and more recently J. Prekopová (Slovak national bibliography) and others. We will now look more closely at the first two examples which are more prominent in the Slovak environment.

Sternberg (1995, 2008) bases his theory around the fact that people have a specific idea about love (they have their own story of love), and they expect their own relationship to resemble it. If both partners have the same idea of that story, then no matter how peculiar the relationship, or even absurd to others, their shared story—their love—will work. But if their ideas of the story differ, the relationship will begin to fall apart, no matter how harmoniously it develops or seems to others. Sternberg begins from the Kantian premise that it is impossible to know the definitive essence (truth), and then goes on state that in reality fact cannot be clearly separated from fiction, because we adjust the facts of the relationship to reflect our own personal fictions. Although we may feel we are gradually getting to know our partner better, that need not be the case. It could be that we are creating a story that has less and less in common with what that person is really like. The process of getting to know the other person affects the ideas, feelings and wisdoms that we have acquired along with our emotional baggage from the past. Sternberg thinks that in principle our stories are influenced by the environment and culture in which we live, so our stories can change over time and across space. We spend our whole lives listening to and being aware of various stories about love, and we can draw on all these stories when we create our own ones.

Fromm thought love was the only true and permanent solution to questions about the depths of a person’s essence, and that is the need “to overcome his separateness, to leave the prison of his aloneness” (1956, p. 9). This feeling of separation and the finality of natural laws causes people to feel anxious about being excluded. None of these solutions, however, are permanent or even complete, since they do not ensure a true connection with other people. This human need can only be fully realised, thought Fromm, through love and by becoming one with another person (p. 29). He considers love to be an activity and so falling or “standing in” love (p. 22) is impossible. Love’s most basic characteristic is giving not taking, but giving, he warns, is often misunderstood to be a process whereby you have to forfeit something or make a sacrifice. In love giving without getting anything in return brings joy. Erotic (partner) love is exclusive, unlike fraternal or maternal love. It is an act of will. It is the decision to devote the rest of your life to another person. Fromm notes that a degree of confusion entered twentieth century perceptions of love, with love being seen as an object problem rather than a skill problem. People search for the right object so they can be loved, but what is essential, according to Fromm, is realising that love is an art (a skill) and that it has to be mastered just like any other skill (Fromm, 1956).

Methodology

Research questions

We asked the following research questions: what knowledge, ideas, beliefs and images of love do young people have based on their initial experiences of partner relationships? Which of these are common among young people, which dominate and which are individual? How are they structured? What sources do young people draw on in articulating them?

Method

Bearing in mind the above research questions and our use of social representations theory as a theoretical framework, and given that social representations of love is an under-researched area, we decided to adopt an explorative research plan.

In her research on social representations Plichtová (2002) recommends the researcher should begin by investigating the ideas of specific individuals and how these are embedded in everyday existence. In our study we adopted an inductive approach, in which we used a thematic content analysis beginning with the individual responses, definitions and experiences of love and working our way to more general categories.

The research tool was a questionnaire survey with open questions. We electronically distributed an anonymous questionnaire to which respondents could answer freely. In it young people were asked: 1. What they thought love was, or what they thought suggested love, given what they had observed in their social milieu 2. Which associations, memories, did they make or have in relation to love 3. Had they come across works of art or artistic performances that represented love[4] and lastly 4. How would they briefly explain what love was to someone. In this research we analysed the written responses to questions 1, 2 and 4, which target the social and individual representations; question 3 was not part of this analysis.

Research sample

The research participants were 264 full-time students at five higher education institutions in Slovakia (Bratislava, Trnava, Banská Bystrica, Nitra and Prešov). The vast majority of the respondents were women (91.7%). The most frequent subjects studied were: education—general (33.7%), psychology (9.5%), ethics, ethics education (7.5%), media studies (5.3%), languages (4.9%), education—subject-based (4.9%) and social work (4.2%). The percentage of research participants declaring they were religious was 78.4%. Regarding sexual orientation, 95.8% stated they were heterosexual, 2.7% bisexual and 0.8% homosexual. The majority were single and in a relationship (64.4%), while 32.3% were single and not in a relationship, and 3.4% were married. The participants were most likely to have had two partner relationships (27.3%), followed by one (26.1%), three (16.7%) and four (12.1%). The most frequent number of short-term partner relationships was one (27.7%), followed by none (25.0%), two (17.4%) and three (6.4%). Most were or had been involved in one longterm partner relationship (48.5%), followed by two (21.6%), none (9.5%) and three (6.4%). Participants with children represented 1.5% of the sample.

Method of analysis

We considered a thematic content analysis to be the most suitable theoretical framework and inductive approach for the analysis in this research. Within described epistemology, an inductive thematic analysis (ITA) was proved to be a suitable approach (Braun & Clark, 2006). In practical terms, we focused on the “bottom-up way”, i.e. the identification and coding of themes emerging from the text. In the final stage of the analysis we looked for the structure of the themes based on the content and language connections.

In the first phase, researchers conducted an initial marking of text passages (initial coding). Individual passages of text were assigned a number of codes. During the coding process, researchers coordinated their codes. At this stage, 44 different love themes were identified. The data coding was performed by four students (first stage only) who had attended a course on data methodology and processing, and two researchers (the authors of this article). In the first stage of coding the six of us independently analysed the first 25 respondents’ answers and then the second 25. Meetings were held during the coding process to ensure there was agreement on the coding (92% at the end of the first coding stage). The remaining responses were coded independently by student pairs and the senior researchers also coded a selection. The codings were then compared at meetings (agreement of 87%– 95%).

Then in the second phase the two researchers independently created the second order categories which were again compared, recategorised and categories were joined together. Where the categories were unclear we returned to the initial responses, and so forth. In the end, the researchers agreed on 38 categories that captured the meaning of the clusters of love obtained from the research sample. The results of this analysis are in Table 1.

Representations of love among higher education students

| Representation | N [∗] | N [∗] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Love as a person’s sentiments, feelings, and emotions | 87 | 20. Love as a state of ecstasy | 17 |

| 2. Relation, bond | 22 | 21. Love as inner harmony | 46 |

| 3. Love as reciprocity | 109 | 22. Love as energy, a necessity, the meaning of life | 22 |

| 4. Love as being in tune, communion | 17 | 23. Love as liberating, freedom | 7 |

| 5. Love as an implicit or explicit shared norm (agreement) | 79 | 24. Love as protection against destruction | 1 |

| 6. Physical Love | 109 | 25. Love as a unique phenomenon | 10 |

| 7. Love as togetherness | 26 | 26. Love as a struggle | 5 |

| 8. Love as co-creation, building | 18 | 27. Love as certainty, security and satisfaction | 32 |

| 9. love as a search, pathway | 10 | 28. Permanent/fleeting love | 4 |

| 10. Love as a choice, decision | 7 | 29. Long-lasting love | 4 |

| 11. Communicative love | 11 | 30. Love is incomprehensible | 8 |

| 12. Prosocial Love, positive socialness | 40 | 31. Love as dependence | 3 |

| 13. Love as sacrifice – prioritising others | 49 | 32. Love as introspection (in own world) | 5 |

| 14. Altruistic, unselfish love, giving | 10 | 33. Love as a commercial means | 1 |

| 15. Unconditional, spiritual love | 5 | 34. Love as a motivation to reproduce | 1 |

| 16. God is love | 6 | 35. Paradigmatic change in love | 1 |

| 17. All-powerful love – overcomes all | 7 | 36. Love as self-love | 1 |

| 18. Omnipresent love, borderless | 15 | 37. Reverse side of love | 9 |

| 19. Various forms of love | 33 | 38. Love is art | 1 |

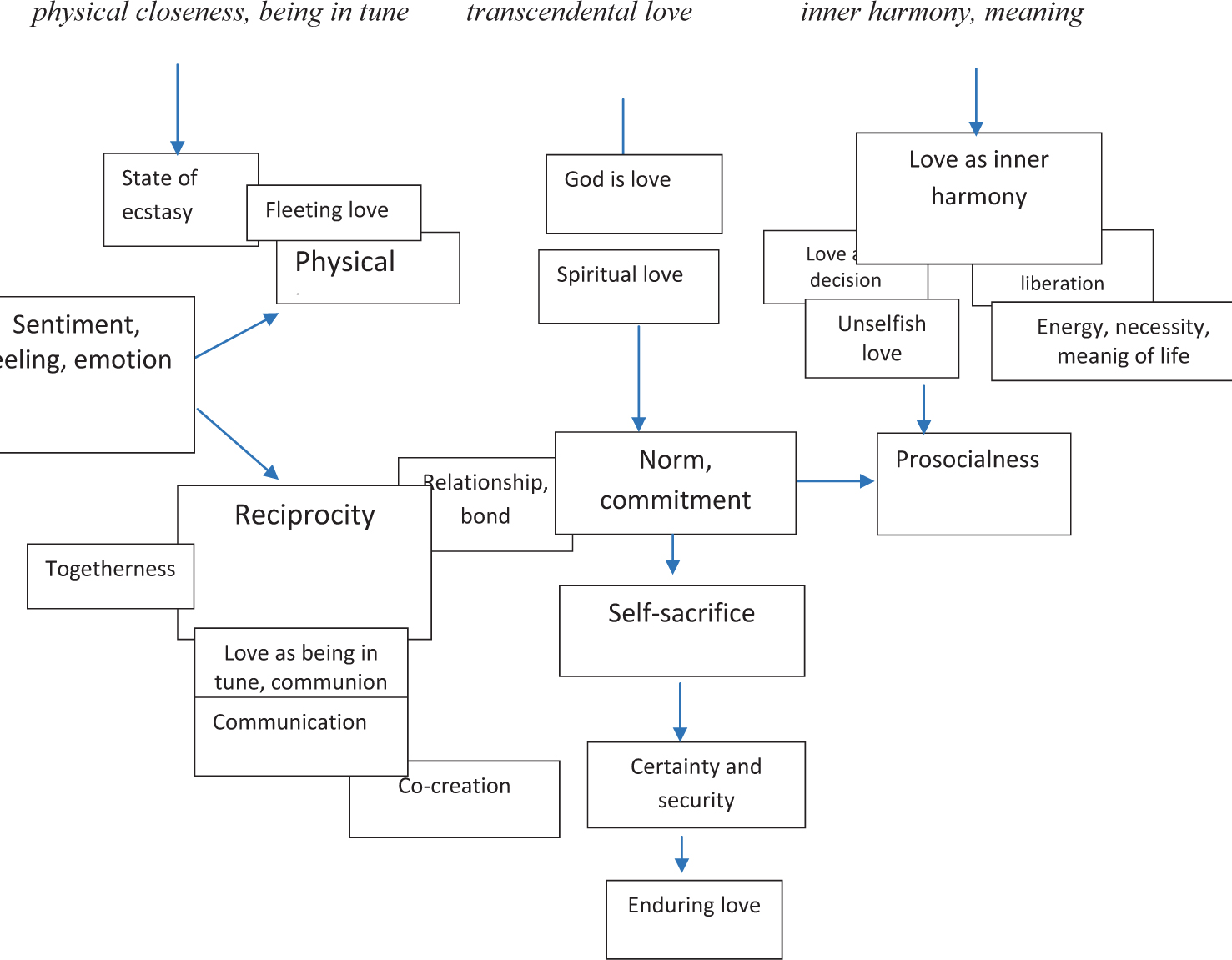

In the third phase based on similarities in the content and language of the themes two researchers selected themes that formed a coherent and structured line. This led to the creation of Diagram 1.

Individual social representations of love among higher education students: lines and structure[6]

Results

The analysis described above revealed 38 individual social representations of love[5], shown in the table below.

Subsequent analysis revealed the relationships between the various individual social representations and the structure they created. This led to three lines of representations: 1. physical closeness and being in tune, 2. transcendental love, and 3. inner harmony and the meaning of life (see Diagram 1). The first line is the strong representation of physical love, love as emotion and love as reciprocity, and then there are more minor representations branching off: love as a state of ecstasy, fleeting love and togetherness. In the second line love is strongly represented as a norm and commitment, as self-sacrifice, prosocialness, and as certainty and security. On the third line we placed love as inner harmony and freedom. As can be seen in Diagram 1, there are smaller interlinking representations. For example love as a bond and co-creation link the first and second lines together, while love as decision and to some extent prosocialness link the second and third lines.

Discussion

Variety and structure of representations of love

The analysis revealed 38 representations of love. New representations were still being found towards the end of the coding process. This may be an instance of the dialogicality of thinking, described by I. Marková, who states that dialogic thinking is characterised by polyphasia, that is, the multifaceted or even oppositional nature of thinking. One of our categories reflects this multifaceted aspect (19). Even in our case it seems that cognitive polyphasia leads to the use of varied and often very distinctive ways of thinking and types of knowledge, such as popular science (love as emotion), ordinary sharing (e.g. love as reciprocity and love as togetherness), religious (love=God) and metaphor (looking for the heart’s other half). This could also be an example of Bakhtin’s “heteroglossia of language that relates to divergent styles of speech stemming from the infinite openness of language in various specific situations” (I. Marková, 2007, pp. 152-153). The young people described love as an encounter between two people who feel the same way, as the communion of two souls and two bodies or the joining of two hearts. Karandashev and Clapp (2015) also refer to a similar breadth of representations of love, although they call them mental representations. Their dimensions of these representations of love that resemble our representations are affection, comfort, commitment, communion, companionship, concern, elation, empathy, forgiveness, intimacy, obsession, protection, reciprocity, sharing, trust and understanding. The wide range of representations of love clearly relates to the breadth and changing nature of partner relationships and sexual lifestyles (Lukšík & D. Marková, 2012; D. Marková, 2012, 2015a, b). One of the lines of representations of love—passionate and socialised love—largely linked to personal experience, is only weakly influenced by normative social instruments, bringing it closer to Giddens’s “pure relationships”, particularly the aspects we labelled reciprocity and togetherness.

Our results do not appear to support Sternberg’s concept of love (Sternberg, 2008), in which ideas on love are considered to be holistic, intuitively story-based, illogical and spontaneous. Although our respondents’ answers were shaped by the questionnaire method we used, only in exceptional cases, when they have to characterise love, do young people give stories as examples. Nor did we find many connections with Sternberg’s 27 love stories, other than stories of self-sacrifice and of dependence. But we should note that young people of this age still have limited experience, and stories require time to develop. In addition to time the protagonists need both the maturity and the ability to identify and name the specific features of a relationship. These often become clear only once they have arisen in other relationships.

In addition to finding a rich array of social and individual representations of love among young people, we also identified the structure connecting the various representations. Three lines of representations were found: 1. Physical closeness and being in tune, 2. Transcendental love, and 3. Inner harmony and meaning. Each of these contained dominant representations such as love as sentiment, physical love, reciprocity, love as a norm, commitment, and love as inner harmony; and further smaller representations can be linked to these or develop from these (Diagram 1). It is only through further research that we will be able to establish whether these three lines are in some way connected to the basic themes or social representations of love. In this research we did not explore the opposite representations that might constitute these themes (I. Marková, 2007). However, opposites such as self-love versus personal or transcendental love, love as being in tune versus love as a struggle could be examples of these.

Sources of social representations

Although our analysis of sociocultural sources of love is just preliminary, it has revealed some connections to contemporary forms of the Western myth of love as well as to Christian love and psychological conceptions of love (in this case E. Fromm’s). The strong representations of love we identified among young people can be arranged into three lines that correspond to the sociocultural sources of love analysed. The first line—physical closeness, being in tune, —is compared to the written source, a more physical, emotional and socialised type of love than the tragic passion-love described by de Rougemont (1972). The love of passionate flaming is close to the meanings of love as state of ecstasy and fleeting love. This line is closer to what Giddens (1992) describes as a “pure relationship” relating to similar meanings of love, like reciprocity, togetherness, and relationship in particular.

With the meanings of love as a relationship and bond and love as co-creation, this line is interconnected with the second line of individual social representations—transcendental love. The second, line transcendental love may only marginally refer to marital love and not at all to “love thy neighbour” love, but it has a number of indirect features that show it is linked to Christian love. Love is defined as being a commitment to faithfulness, devotion, respect and so forth, and it is also prosocial or social in a positive sense and contains representations of love such as certainty and security, often expressed using the mother–child image. The question is to what extent this line of representations of love is simply the ideal norm and to what extent it is real life, as D. Marková (2012, 2015a, b) has pointed out. The third inner harmony and meaning, where we placed love as inner harmony, liberating, prosocialness and love as a decision is closer to Fromm’s concept of love.

Conclusion

The results show a large variety of representations of love among higher education students. In addition to finding a rich array of social and individual representations of love among young people, we also identified the structure connecting the various representations. Three lines of representations were found: 1. Physical closeness and being in tune, 2. Transcendental love, and 3. Inner harmony and meaning. Each of these contained dominant representations such love as sentiment, physical love, love as reciprocity, love as a norm, commitment and love as inner harmony; further smaller representations can be linked to or develop from these. It is only through further research that we will be able to establish whether these three lines are in some way connected to the basic themes or social representations of love.

Although the analysis of the sociocultural sources of love was only preliminary in nature, it has revealed certain connections between the social representations of love and the contemporary forms of the Western myth of love, and Christian love and psychological conceptions of love (in our case E. Fromm’s theory). A deeper analysis of the socio-cultural environment is needed. The representations of love we identified bear features of the dialogicality of thinking, as described by I. Marková (2003). A deeper qualitative analysis is, however, required to confirm this. The results should also be viewed in relation to the fact the sample comprised students and with regard to the fact that they are just embarking on their partnerships, or as we rather ambitiously referred to them in the title in the “early stages of love”. Further research using participants with more extensive experience of partnership life and a deeper qualitative analysis are also required.

References

Aslanian, T. K. (2018). Embracing uncertainty: a diffractive approach to love in the context of early childhood education and care. International Journal of Early Years Education, 26(2), 173-185.10.1080/09669760.2018.1458604Search in Google Scholar

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.10.1191/1478088706qp063oaSearch in Google Scholar

de Rougement, D. (2001, 1972). Západ a láska [Love in the western world]. Kaligram: Bratislava.Search in Google Scholar

Farr, R., & Moscovici, S. (1984). Social representations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Feldman, R. (2012). Oxytocin and social affiliation in humans. Hormones and Behaviour, 61(3), 380-391.10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.01.008Search in Google Scholar

Fromm, E. (1956). The art of loving. New York: Harper and Row.Search in Google Scholar

Giddens, A. (1992). The transformation of intimacy. Cambridge: Polity.Search in Google Scholar

Hatfield, E., Bensman, L., & Rapson, R. L. (2011). A brief history of social scientists’ attempts to measure passionate love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(2), 143-164.10.1177/0265407511431055Search in Google Scholar

Karandashev, V., & Clapp, S. (2015). Multidimensional architecture of love: From romantic narratives to psychometrics. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 44,6, 675-699.10.1007/s10936-014-9311-9Search in Google Scholar

Kraft, C., & Witte, E.H. (1992). Vorstellungen von Liebe und Partnerschaft. Strukturmodell und ausgewählte empirische Ergebnisse. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 2(4), 257-267.Search in Google Scholar

Lamy, L. (2015). Beyond emotion: Love as encounter of myth and drive. Emotion Review, 8(2), 97-107.10.1177/1754073915594431Search in Google Scholar

Lukšík, I., & Marková, D. (2012). Sexual lifestyles in the field of cultural demands. Human Affairs: Postdisciplinary Humanities & Social Sciences Quarterly, 22(2), 227-238.10.2478/s13374-012-0019-ySearch in Google Scholar

Marková, I. (2003). Dialogicality and social representations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Marková, I. (2007). Dialogickosť a sociálne reprezentácie [Dialogicality and social representations]. Praha: Academia.Search in Google Scholar

Marková, D. (2012). O sexualite, sexuálnej morálke a súčasných partnerských vzťahoch [On sexuality, sexual morality and contemporary partner relationships]. Nitra: Garmond.Search in Google Scholar

Marková, D. (2014). Láska a morálne hodnoty v sexuálnych vzťahoch [Love and moral values in sexual relationships]. In 22. celostátní kongres k sexuální výchově v České republice (pp. 35-48). Praha: Společnost pro plánovaní rodiny a sexuální výchovu.Search in Google Scholar

Marková, D. (2015a). Sexual morality in Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Ljubljana: KUD Apokalipsa.Search in Google Scholar

Marková, D. (2015b). Moral values in sexual and partner relationships. Ljubljana: KUD Apokalipsa.Search in Google Scholar

Masaryk, R. (2012). Láska ako koncept v psychológii [Love as a concept in psychology]. In D. Marková, & L. Rovňanová (Eds.), Sexuality 5. Zborník z vedeckej konferencie, (pp. 274-296). Banská Bystrica: UMB,Search in Google Scholar

Mitchell, J. W. T. (2017, 1994). Teorie obrazu. [Picture Theory] Praha: Karolinum UK.Search in Google Scholar

Mercado, E., & Hibel, L. C. (2017). I love you from the bottom of my hypothalamus: The role of stress physiology in romantic pair bond formation and maintenance. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(2), e12298.10.1111/spc3.12298Search in Google Scholar

Moscovici, S. (1961). La psychanalyse, son image et son public. Paris: PUF.Search in Google Scholar

Moscovici, S. (1973). Foreword. In C. Herzlich (Ed.), Health and illness: A social psychological analysis (pp. ix–xiv). London, UK: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Moscovici, S. (2000). The history and actuality of social representations. In G. Duveen & S. Moscovici (Eds.), Social representations: Explorations in social psychology (pp. 12-155). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Mouton, A. R., & Montijo, M. N. (2017). Love, passion, and peak experience: A qualitative study on six continents. Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 263-280.10.1080/17439760.2016.1225117Search in Google Scholar

Možný, I. (1990). Moderní rodina: mýty a skutečnosti [Modern family: Myths and facts]. Brno: Blok.Search in Google Scholar

Nygren, A. (1953). Agape & Eros. London: SPCK.Search in Google Scholar

Plichtová, J. (2002). Metódy sociálnej psychológie zblízka. Kvalitatívne a kvantitatívne skúmanie sociálnych reprezentácií. Bratislava: MÉDIA.Search in Google Scholar

Schneiderman, I., Zagoory-Sharon, O., Leckman, J.F., & Feldman, R. (2012). Oxytocin during the initial stages of romantic attachment: Relations to couples‘ interactive reciprocity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(8), 1277-1285.10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.021Search in Google Scholar

Steinhouse, P. (2013). The Good Samaritan: The unidentified man who fell among robbers on the Jericho Road. Compass, 47, 35-41.Search in Google Scholar

Sternberg, R. J. ( 1995). Love as a story. Personal Relationship, 3, 59-79.10.1111/j.1475-6811.1996.tb00104.xSearch in Google Scholar

Sternberg, R. J. ( 2008). Láska je príbeh [Love as a story]. Bratislava: Ikar.Search in Google Scholar

Von Cranach, M. (1995). Social representations and individual actions: Misunderstandings, omissions and different premises. Journal for the Theory of Social Representation, 25(3), 285-293.10.1111/j.1468-5914.1995.tb00276.xSearch in Google Scholar

Watts, S., & Stenner, P., (2013). Definition of love in a sample of British women: An empirical study using q methodology. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53(3), 557-72.10.1111/bjso.12048Search in Google Scholar

© 2018 Ivan Lukšík, Michaela Guillaume, published by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Symposium: On Flesh & Soul, Love & Death

- Introductory

- Partner relationships and the raising of a temperamentally difficult infant

- “Naked flesh”—A somatic calling of the “mind”?

- Female erotic desire

- Consensual qualitative research on free associations for compassion and self-compassion

- Representations of love in the early stages of love

- Articles

- What does it mean “being chilled”? mental well-being as viewed by Slovak adolescent boys

- Testing SCM questionnaire instructions using cognitive interviews

- Design thinking, system thinking, Grounded Theory, and system dynamics modeling—an integrative methodology for social sciences and humanities

- Nussbaum’s philosophy of education as the foundation for human development

- Book Review Essay

- Teilhard’s planetisation of mankind as part of globalisation

Articles in the same Issue

- Symposium: On Flesh & Soul, Love & Death

- Introductory

- Partner relationships and the raising of a temperamentally difficult infant

- “Naked flesh”—A somatic calling of the “mind”?

- Female erotic desire

- Consensual qualitative research on free associations for compassion and self-compassion

- Representations of love in the early stages of love

- Articles

- What does it mean “being chilled”? mental well-being as viewed by Slovak adolescent boys

- Testing SCM questionnaire instructions using cognitive interviews

- Design thinking, system thinking, Grounded Theory, and system dynamics modeling—an integrative methodology for social sciences and humanities

- Nussbaum’s philosophy of education as the foundation for human development

- Book Review Essay

- Teilhard’s planetisation of mankind as part of globalisation