Sensibility in applied ethics

-

Rainer Born

Abstract

Rule systems are used every day to share experience, pre-existing knowledge, beliefs and ethical rules, and to provide instructions for future action. This article expands and builds upon an approach pioneered by Julius M. Moravcsik to argue that ethics cannot be completely codified into a rigid set of rules, because any such set lacks a misapplication-correcting sensibility. Thus, an ethics that is transferred purely by means of a rule-set is incomplete and thus cannot be used reliably to guide future action. The balancing sensibility is formed out of pre-existing expert knowledge and takes account of the limitations of rule-sets in specific contexts. Moravcsik’s approach is then expanded by incorporating it into a holistic framework for the analysis, guidance and development of actions to be taken to support the emergence, selection and implementation of solutions for a sustainable future. This approach has profound implications for managers and organisers in new or critical situations.

Once again, we are learning that nothing truly complex can be broken down into its parts without losing the integrity of the whole.

(Verna Allee, The Future of Knowledge, 2002, p. 102)

Preliminary remarks

This article grew out of a paper originally intended for an international conference on applied military ethics that took place in Vienna, attended by participants from many countries involved in continual war, including Israel and the USA. However, the aim of that paper was not to provide fixed rules to dictate decisions and evaluate actions and tasks in critical situations with ethical aspects, but to investigate mental preparation and resilience ethics (Chandler, 2013). Thus, the point was to understand a given “task” and to reflect on the limits of the available rules and situational structures as well as to consider the possibility of forming an ethical sensibility (in an explanatory sense) and sensitivity (in a descriptive sense) to the need to be alert, reactive and open to changes in the general master-plan (explicitly known or unknown).

Classical approaches in ethics (deontology versus utilitarianism) that consider what is “good” from a definitive, general and moral point of view were deemed unsuitable from a pragmatic perspective (see Dewey, James, Putnam). Therefore, the work of Julius Moravcsik (1931–2009), an American specialist on pre-Socratic Greek philosophers with a special interest in ethics, was selected as our starting point, since it goes a long way towards combining “continental” European thought with Anglo-Saxon thinking. Unlike the work of Moravcsik, the classical approaches consider the moral point of view to be more or less absolute and neglect to reflect on “how” the task of ethics comes about, and especially how it is applied.

Hilary Putnam’s lectures and publications (e.g. Ethics without Ontology, 2005) provide a good starting point. He proposes a “Third Enlightenment” (pace Dewey, a pragmatic one) that would be ready for being considered in the ethical evaluation of economic decisions. This idea is best illustrated by the example below that goes beyond classical economic considerations and, for practical reasons, attempts to overcome the conventional distinctions and isolated development of certain academic disciplines. In this sense, following James and Dewey, Putnam (2005, p. 107) insists that ethics should be considered the “relation of inquiry to life” (authors’ italics) in considering the emergence and use of knowledge which sheds light upon the relationship between scientific endeavours and ethics generally and draws no prescriptive distinctions between them. Thus, according to Putnam (2005), Dewey’s Logic should not be viewed as a volume on logic or epistemology but as a “book about social ethics”. Putnam (2005) believes that this is “the right way, indeed the only way, to open up the whole topic of ethics, to let the fresh air in” (Putnam’s italics). And that approach—according to Putnam (2005)—is an essential part of what he has called “the pragmatist enlightenment” and which in some sense boils down to the practice of “criticism of criticisms”. Furthermore, Putnam (2005) refers to John Rawls who, in describing traditions in ethical discussions, points out that the kind of moral philosophy that primarily deals with judgements and contains familiar ethical concepts seldom exceeds the boundaries of Kantianism (deontology) and utilitarianism (normativity). However, according to Putnam’s (2005) interpretation of Dewey’s Logic one should not (and cannot) assume that the problems of either field philosophy or ethics “can be formulated in any one fixed vocabulary, or illuminated by any fixed collection of ‘-isms’”. We therefore need to develop some kind of sensibility to address the incompleteness of the rule system in use—both explanatory and descriptive (see Putnam’s discussion of Gödel in Reason, Truth and History, 1981). In connection with his pragmatic “enlightenment”, Putnam (2005) refers to this as “criticism of criticism” in several contexts.

In order to illustrate this point, it is worth considering the following quasi-practical situation: The management has to make economic decisions about actions relevant to the future of the company. The members of the management board therefore ask for the information on which to base their decisions. However, they have little awareness of how this information really comes about (if one considers the weight of simplifying assumptions upon which it is built). It calls to mind the discussion from a sociological point of view of the “complete information” within the market that led to the disastrous world-wide financial crisis of 2007/2008, as discussed in Crouch (2015, pp. 31ff.). Using information at face value within internally-generated constructions of meaning implies an absence of reflection and enquiry into how the decision-relevant information or its inherent meaning came about. There is a neat real-life example in which this kind of decision-making, based on isolated, limited and results-oriented optimization, led to disaster for Daimler-Chrysler, a German-US based car manufacturer (now separate again), to the tune of more than 25 billion dollars. The information provided to the management was very unbalanced and the processing stage had failed to produce information with any realistic meaning.

Thus, following Putnam’s argument, there is a need for a semantic approach based on model theory (in the sense of formal semantics) rather than an empirical projection of a plainly syntactical approach (rules and switching rules). The reason is simple: in no real-life context can anything be reduced to rules making it unnecessary to further enrich our common-sense background understanding and our knowledge of the world, and sometimes our own point of view as well. In other words, there does not exist—as many assume—a simple universal common sense, which means there is a current—and urgent—need to enrich the local epistemic resolution power of our endeavours to garner additional reflective and corrective knowledge that would enable us to apply information consistently in decisions relating to a constantly changing world.

As will become clear from the detail that follows, one can presuppose there is a triangle between three special knowledge components (see Figure 5). The first angle is the expertise that informs the application of routines/rules to ethics and everyday life. In ethics, the “golden rule” may especially be considered a practical guide both in theory and daily life. The second angle relates to general cultural, or folk background, knowledge, including an everyday cultural feeling for what a good starting position would be. The third angle refers to the routines/rules exemplified in modern bureaucratic rationalization and—loosely speaking—considered to be the backbone of capitalism, in the Max Weber sense. If one applies rules under the presupposition of some weak or locally-fixed folk background knowledge, then one may be prone to accept results for the application of those rules unconsciously as universally-assumed cultural background that would not have survived a good expertise-based dialogue of the kind promoted by David Bohm (1996).

This is both the substance of, and motivation for, the requirement for pragmatic enlightenment and an “inquiry into inquiry”, that is, an investigation into the relation of inquiry to life and the explanatory identification of possible rules, with particular attention being paid to the local limits of application. Paradoxically then strictly separating ethics from “knowledge about the coming about of knowledge” so as to account for the incompleteness of our formal rule systems (axiomatic or otherwise) would seem to be ineluctable and unacceptable, in both logical and epistemological terms, especially from the pragmatic point of view of Peirce, James and Dewey.

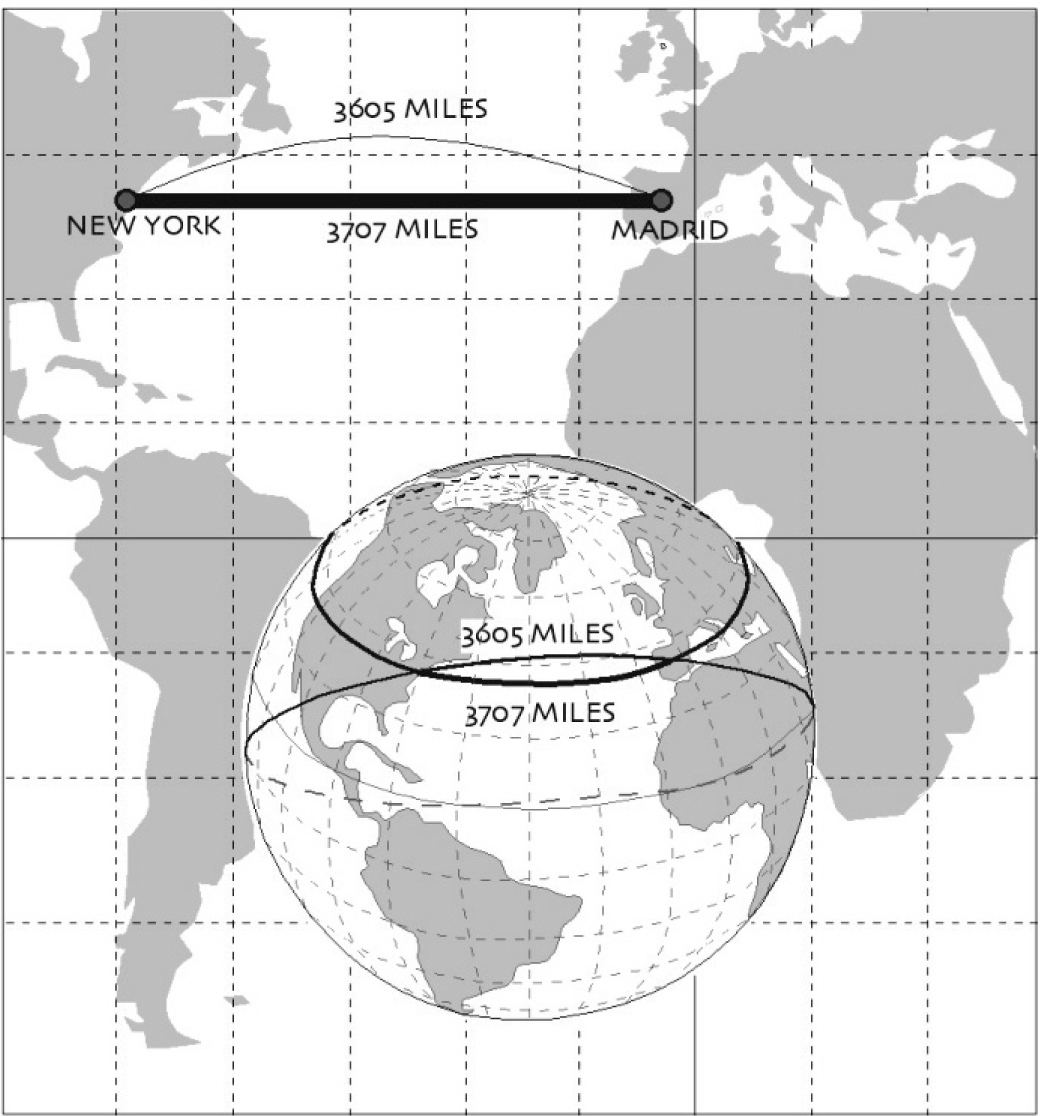

It is essential to consider the relationship between explanatory theoretical thinking and the practical application of knowledge. Developing sensibility (in applied ethics) is not reducible to a set of formal rules for conveying useful information. This point and the problem of the “axiomatization” of knowledge in general is made clearer by the illustration in Figure 1. From the two-dimensional map the straight line connecting Madrid and New York is considered to be the “shortest” connection according to axiomatizable Euclidean geometry (Hilbert, 1903). However, the perception that it is the shortest connection between the two points is not based on reality but is a logical consequence of the axiomatization of Euclidean geometry. Nonetheless it works in our experienced reality insofar as our simplified model is useful in guiding some of our actions or our interplay with what we encounter as our living world (Lebenswelt). The definitions of the core concepts of “point”, “line” and “plane” in geometry are “implicit definitions”, an idea further explicated by Moritz Schlick (1918) of the Vienna Circle. But the geometry of a sphere, when used as a map or model for orientation upon the surface of Mother Earth, is different. The shortest connection is then identified by a geodesic. Thus, if we compare Euclidean geometry with an axiomatic approach to ethics (cf. Spinoza’s more geometrico), it may initially appear successful but soon the same problems will be encountered as those between Euclidean geometry and, for example, the geometry of the surface of the Earth considered as a sphere. Attention must always be paid to the coming about of knowledge and what “the shortest connection with respect to reality” means in any given context. Analogically, the idea that something is “good” from a general moral point of view is helpful to find a solution that is adequate with respect to an ethical evaluation of actions in real life, even if our experience of real life is artificially distorted by the use of modern technology.

Attention to dimensions

We thus end up back at Putnam’s quest for a new pragmatic Enlightenment to deal with the coming about of knowledge and its proper application. There is also the question of why Putnam is involved in aspects of social ethics connected to Deweyan logical inquiry. Putnam’s discussion suggests we might find more support in John Dewey’s recently-discovered “lost manuscript” (2012), Unmodern Philosophy and Modern Philosophy. However, the concern in this article, which is based largely upon the idea of a Third Pragmatic Enlightenment, is to obtain a sound understanding of the “development of sensibility” in applied ethics, especially in the “sphere” and context of uncritical economic thinking and decision-making, that is, in an area in which there is no feeling about how far one can go in turning locally calculable economic optimization into practical actions with world-wide consequences. However, axiomatized ethics cannot help us here. The answer lies in criticism of criticism, in understanding how the knowledge in use comes about and in appraising the consequences of turning decisions into action. This should re-energize ethics. There is an acute need to prevent poorly understood digitalization from being used in business and to encourage the development of new solutions, which could finally be the key to the survival of Homo sapiens—“Thinking Man”, who has forgotten how to think (see the cognitive evolution of Homo sapiens as described in Harari & Perkins (2014).

In summary, a semantic approach is required, in the form of model theory in the sense of formal semantics. This is in sharp contrast to empirically projecting a plainly syntactical approach. Nothing can be reduced to rules to the extent that it becomes unnecessary to enrich our common-sense understanding—sometimes, mirabile dictu, our own points of view. In other words, contrary to assumptions, there is no simple universal common sense. We therefore have to enrich the local epistemic resolution power of our endeavours and strive for additional knowledge.

Setting the scene: Rules and sensibility

Ethics and success are widely held to be incompatible in business. One cannot afford to be ethical in business—it is a luxury, an indulgence; pity is dispensable. However, this must, surely, depend on what our intuitions about life are, what we aim for and how we (want to) live (Moravcsik, 2003, p. 37). In Fugitive Pieces Anne Michaels (1997) describes the situation of two lovers:

It is late, almost afternoon, when she says, though I may have dreamed it, though it’s just something Michaela might ask: Are you hungry? No… Then perhaps we should eat so that hunger won’t seem, even for a moment, the stronger feeling (p. 181).

Perhaps this is what ethics is about—not eating, but thinking ahead, about feeling empathy, sympathy, and about thinking of others—looking after our shared future. But this is just the beginning.

Usually when thinking about ethics, we start with definition(s) of ethics or of what is considered to be “good”. Rarely do we discuss the task(s) of ethics or the reasons why we consider “the good” to be good. This approach may be compared to tidying up an empty room; it tells us nothing new. The definitions can only elaborate on what we already know, or on what appears to be compatible with the established world-view. In this article, we will argue against this approach. In today’s world, it is vital to be alert, in nearly every sense of the word. Let us return to Figure 1. What could it convey by analogy? It could establish some kind of “sensibility” on the misinterpretations of maps (insofar as they are used to guide action). Figure 1 is a deliberate reduction and/or simply lacks the dimensions that would avoid the misapplication of (ethical) theories, models or charts of the world. The lack of dimensions may well be the result of having overlooked problems and having failed to prevent un-intended results. It is not always the case that the most direct, or shortest, path (according to the map) to a destination is the optimal, or best “solution” to a problem.

This led us to adopt an approach which we discovered had already been developed by Julius Moravcsik (2003) as an alternative to utilitarian and Kantian ethics. We then sought to extend these ideas to fit in with our own model and theoretical approach. The aim is to cross the boundaries demarcating the logic of inquiry and social ethics of Dewey and Putnam. This means taking into account the way we are affected by the actions of others and vice versa when fulfilling our duties and responsibilities and considering the consequences of our actions. When thinking about what we or others ought to do in a given situation, Moravcsik (1980, p. 198) maintains that

[o]n the one hand, we can be harmed by actions and circumstances that work against realizing what is in our interest and what would help fulfil our potentialities. On the other hand, our actions and attitudes can harm or diminish our contributions to the benefit of others.

According to Moravcsik (1980, p. 198), these “dangers” can be divided based on the main ethical theories into two groups: The first [danger] concerns “what we want to do with our lives and how we find means to carry out such plans”, while the second [danger] relates to “matters of morality, to be specified in terms of an autonomous set of rules”.

Furthermore, it must be reiterated that we did not start from a syntactical definition of ethics. If we were to provide a definition, it would be an “implicit” one, like the one adopted by David Hilbert and Moritz Schlick, and it would be based on the tacit background knowledge or intuitions relevant to ethics or examples of the use of morals. However, we are far more concerned with what ethics is about, what kind of help it can provide, what kind of role it should play, and what kind of task it might fulfil.

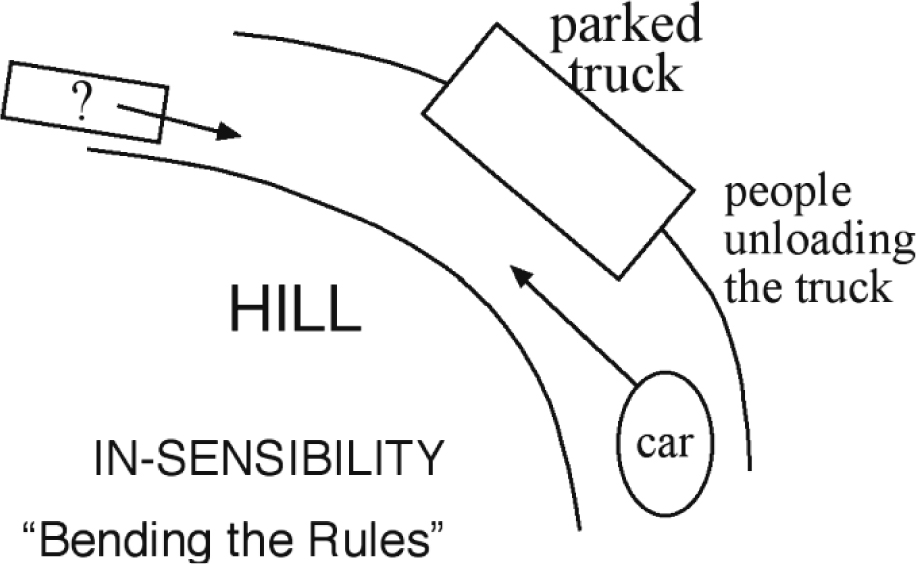

So, the question is: In what way can codifying ethics as a set of rules help us insofar as they correspond to the structural regularities inherent in the situations in which we have to act. The term “rules” is used here in the context of Wittgenstein’s ideas about following a rule, and in the context of ideas in analytical philosophy generally. We should point out that ethics is related to our “sensibility” in judging our action-guiding rules and measures on the basis of duties and responsibilities insofar as they involve the consequences/outcomes/ values of our actions. Another way of developing a degree of “sensibility” can be seen in Figure 2, “b(l)ending the rules”: The traffic situation shown is an example of in–sensibility (ethical and otherwise). The best way to unload the truck is not the best option overall. The people unloading the truck show no consideration for the other road-users. However, the traffic situation is only part of the problem, secondary to whether it is possible to resolve matters using a set of codified rules for the appropriate action, plus certain sanctions (see the Samaritan paradox below) if the rules are disobeyed. Could this set of rules be added to? Or is the answer to remain flexible, adaptable and innovative in future situations? One solution can be seen below.

B(l)ending the rules

Two further examples may prove useful. First, let us consider an aircraft carrier, a “floating military airfield” with a total crew of 1,500 to 5,500 people. What kind of organization is required? Organizational psychologist Karl E. Weick has coined the term high reliability organization (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2015). This system is activated in circumstances where the slightest mistake may have disastrous consequences. Can the problem be resolved just by introducing rules for organizing and sanctions for disobeying them? We maintain that it is extremely important to understand what we are doing, that is, it is not enough just to be motivated, we have to see the sense of what we are doing and the possible consequences of our actions. Procedures cannot be delegated to machines; there are too many unexpected events or situations that could occur at any time. To sum up, rules are not enough.

Second, imagine a girl, of around 10 years old perhaps, using a pocket calculator to repeat a calculation you have shown her, for example the size and cost of carpeting the floor of a room. She puts the decimals in the wrong place and obtains too large a number as a result. But she has no experience, no feeling, no way of interpreting the numbers in that context. She has no feel for what she is doing—yet. Can we trust her? And even if she gets the correct result, we would be wise not to assume that she had “calculated” it correctly unless we were sure she had understood what it was all about. Then in a critical future situation we could in fact rely upon her calculations. We have the same doubts about dogs. Here the question is whether we simply obey “ethical” rules with no sensitivity to, or regard for, the consequences of applying them.

Of course, practical ethics does not imply that we should be cast into the confusion of the hypothetical centipede asked about the rules for crawling and doomed continuously to reflect on sequences and mechanics to the extent that it can no longer crawl. It should in fact be the other way around. “Highly reliable” normal situations should generate feelings of security and safety, while we should develop a feeling or sensitivity for unexpected or restrictive situations in which it becomes necessary to act quickly as well as responsibly, creatively, innovatively and successfully—this is what good and ethically-considered behaviour should be about. Furthermore, it must be emphasised that emotions (cf. Gruen, 2003) and sensibility have to be considered in addition to the rules. This aspect was of course addressed by Plato, but his ideas have been narrowed down by, for example, Kant and utilitarianism. Two points are therefore essential to our argument:

It is essential to realize that a basic ethical attitude (as embodied in rules, actions etc.) toward our fellow-humans cannot be captured by or replaced by a rigid set of rules nor can it be codified or built up by them; the successful use of norms/rules presupposes that we have some background knowledge or a responsible basic attitude that guides or steers our actions.

We should also strive to be “sensitive” to the nature of situations, i.e. the context that creates the meaning (cf. approaches to analysing arguments considering “situation semantics”, e.g. the semantic approach to logic developed by Barwise & Perry, 1999; Barwise & Etchemendy, 1999) to avoid, for example, the centipede paradox.

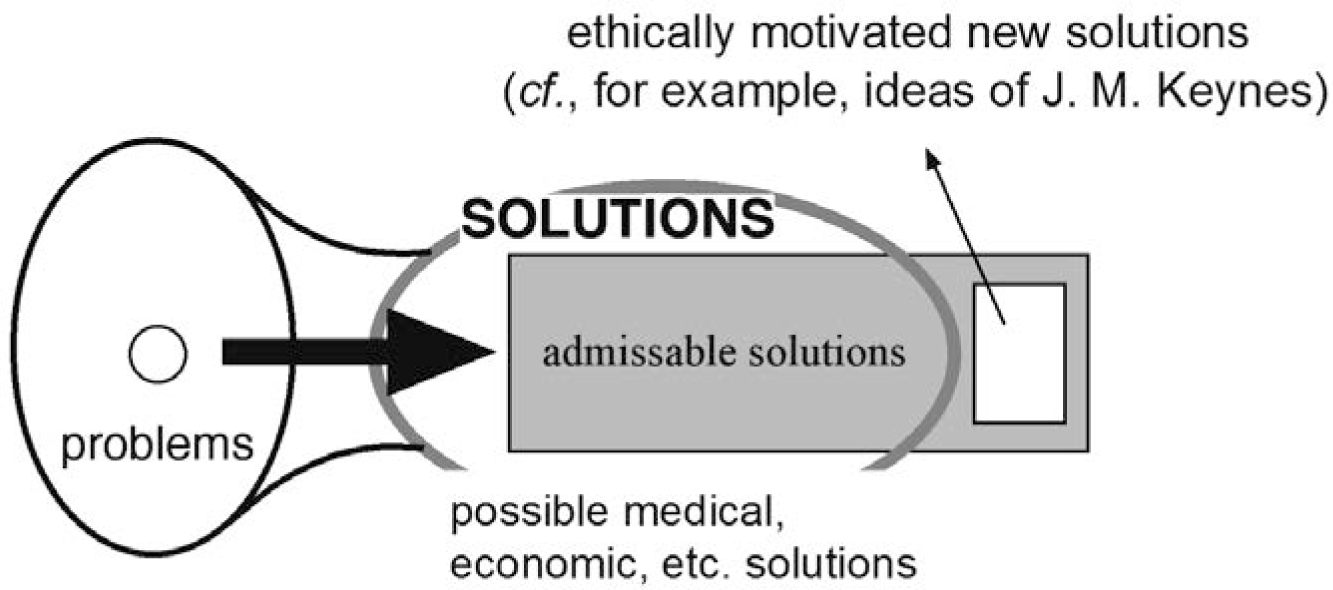

A modern example involves heart transplantations. If the Hippocratic oath is taken seriously and the doctor reaches the conclusion that she has to save lives (and never deliberately kill a person) heart transplantations are an acute dilemma. On the one hand, a life is being allowed to end. On the other, it is possible that another life may be extended. Thus, in order to justify the operation, we have to replace the intuitive notion of “cardiac death” by “brain-death”, thus degrading the heart to a “callous, unfeeling mechanical pump”. Thus, the original “value”, that is, saving life, can be adhered to and all that has to be altered is the set of “possible actions” or, rather, new “constraints” within which the goal is achieved given what is medically possible (perhaps euthanasia). Hence “admissible” measures that will produce a subset of “good” (ethically justified) actions have to be identified. Insofar as ethics addresses these constraints, it has an empirical impact, both positive and negative; the practices of some physicians in the Nazi concentration camps spring to mind. As will be argued in the “X-ray example” below, medical students need to do more than just learn the rules and develop a scientific understanding of what goes on in the body; they have to develop an ethical sensibility. Figure 3 may prove helpful in visualising the relationship between possible and admissible solutions.

Admissible solutions

The main problem appears to be selecting (and reproducing) the set of admissible actions that can be considered solutions to the problem, starting with a set of computationally, logically or logistically possible decisions about the action to take. This leads to the desire to produce a set of rules ex post facto that both reproduces and explains the admissible results. In this way, the “standard” or “default” solutions (depending on the accepted background knowledge) will be understood on the basis of argument and can be reproduced in a controlled manner. However, when considering the “value” of the new solutions, we have to develop a feeling, a sensibility, an eye for the context, that is, we have to know how far we should go (or would be allowed to go) and whether we should maintain confidence in the rules or consider modifying them. This is where sensibility, experience, knowledge and thinking are needed. Basically, we have to evaluate our actions (not always consciously) as they emerge (a process that also has to take duty into account) and the consequences of them (the issue of responsibility).

Further considerations for the development of sensibility

Just for argument’s sake, suppose the two pilots of a pre-drone commercial airliner fell ill and were no longer capable of reliably flying the plane. The plane is on auto-pilot, and a 12-year-old child is in charge who has sufficient experience of playing a flight simulator computer game and who is in radio contact with the control-tower of the next airport. The passengers are just being informed. How do they feel? Do they trust the autopilot? What has this to do with ethics? Do we think a non-adult can legally take “responsibility” for the aeroplane? Is the tower able to give the child sufficient support? Do we trust the emotion-guided technology? Who is in fact responsible for the aeroplane, the hundreds of passengers and for ensuring a safe landing? Who actually takes responsibility for the life of the passengers? The non-adult? What would lawyers think of this? Could we say the autopilot, its programmer or other persons are responsible? Do we think the autopilot is a technically “comprehensive” system and what kind of erroneous expectations do we have in trusting in the program? There are certainly parallels to ethics here.

Should we believe that an ethical rule system is sufficiently comprehensive to be acceptable in decision-making of this nature? Do we think that no technical adjustments will be required? That there will be no need to interpret (instruments/data by the pilot), understand or make sense of things? From another angle, do we not think that both experience and sensibility are needed? Could it not be that in trying to explain an experienced pilot’s success, we have to think of her ability to best use the autopilot, to know when it can be used reliably and when to switch it off in a sudden non-standard situation? Experience is required or is thought to be required for any individual to use an expert system (even in ethics). What is probably wrong (and can be formally proved) is the belief that there could be a very sophisticated expert system that any person of normal intelligence (universal commonsense) could use to produce the same (decision) result as a true expert. It should be noted that specialists in certain fields are far from immune to blind spots regarding ethics.

However, the main problems are creativity and innovation with respect to future developments. Not everything is decided by blind natural selection or, phrased differently, human reflection (and definitely ethics) may well have developed as a cultural by-product that overcomes the passiveness of Darwinian evolution. “Reason can transcend whatever reason can formalize” (Hilary Putnam, 1981) was Putnam’s succinct response to Kurt Goedel’s incompleteness theorem on the limits of formalization and the blind or mechanical use of rules. However, this does not hold true for soldiers and officers, for example. Those who direct battles need to know when they find themselves in an exceptional situation in which they have to evaluate/forecast unexpected developments and apply the rules of engagement and tactics with a degree of care and some sensitivity (see also Weick, 1979).

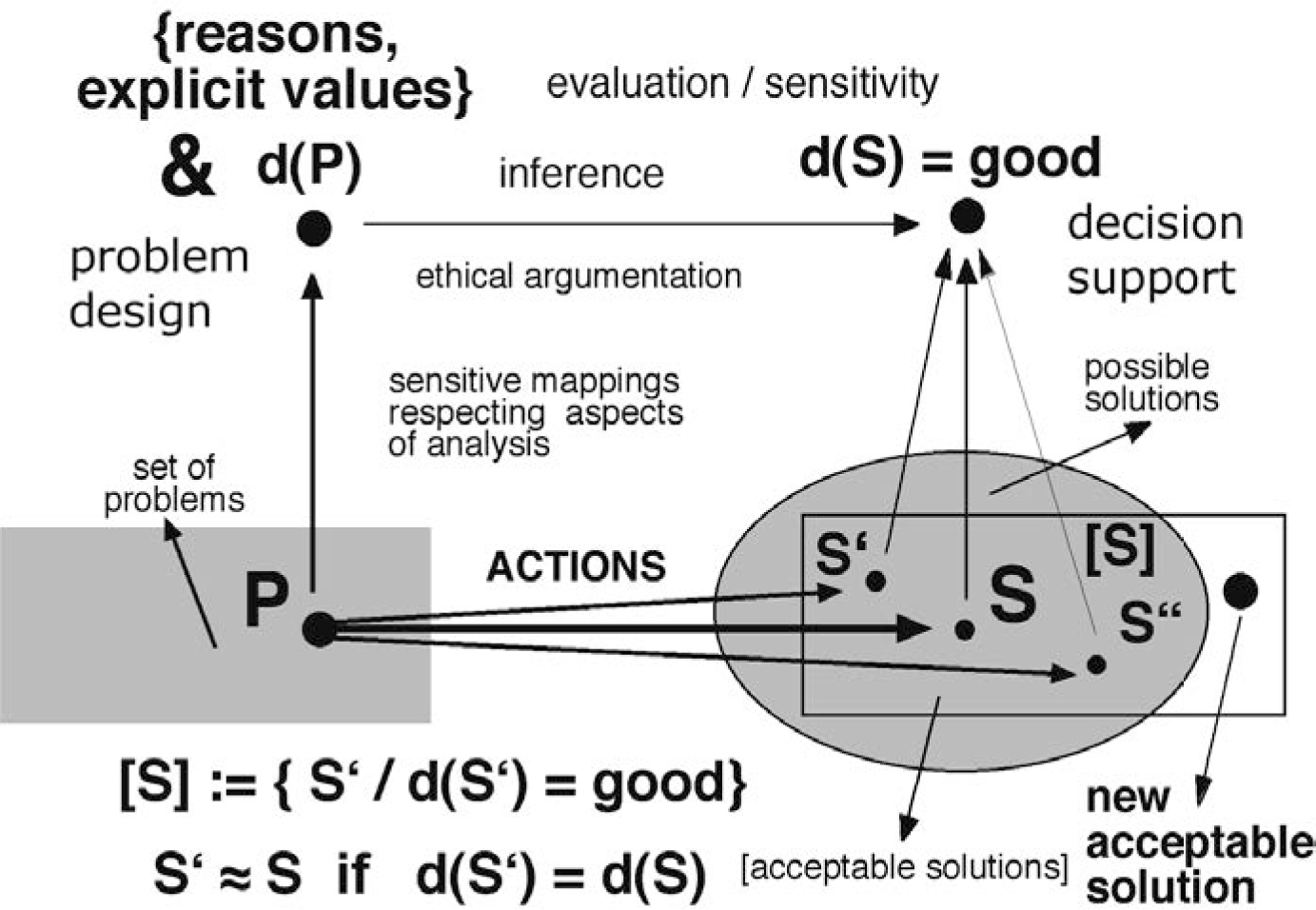

With such reasoning, it is essential that the rules of action are formulated to correspond to common-sense thinking, common-sense moral intuitions and implicitly-given value systems or sets of beliefs (see Figure 4). However, this does not apply to the justification of those rules, norms or checklists. Mixing the two could be a fundamental problem in applied ethics, as dealing with real “rules” for decisions is not the justification for those rules. Only if we truly think our future can be completely regulated or determined by and captured in our system of rules or logic is it meaningful to think nothing unexpected will occur.

General idea

It is frequently noted that some people work well “within the rules”, but much less attention is paid to carefully identifying the real roots of success: pre-experience and good common background knowledge. The latter enables us to correct any errors in application and adjustment. The “alternative approach”, as Moravcsik (2003, p. 37) calls it, posits that simply justifying ethics does not point to the necessary practical sensibility in a given historical situation. When we learn to read a map, we have to learn the signs used (to relate the map to the landscape) and the rules, that is, we need to develop a sensibility for reality. We have to learn that a map is not a description of reality nor a literal device to be used to guide our actions. In this sense, an important task in ethics is to introduce a human measure that can be applied to rule systems, one that can correct over-rigid, instrumental algorithmic, and therefore un-reflected, approaches to rules. Guiding conceptions based on “thinking by content” should be used alongside the application of rules (semantics cannot be reduced to syntax). The paradox here is that people have to choose the rules so they correspond, in the normal field of experience, to moral feelings. This ensures swift and reliable action (rather than the “centipede” paradox discussed above). We need to feel secure and good about the limits of our actions. We need to be aware of the scope and validity of experiences in standard situations. Schooling helps, as do wide-ranging experience and the development of sensibility and responsibility and being conscious of our duties. In this way ethics, as moral rules (conscious or not), are an enormously important empirical factor in everyday life. This leads to a second paradox: many people seem to believe that sets of rules can compensate for taking responsibility for individual actions. However, this is only true only in a hypothetically average way of life and, since being aware of the limits of rule-systems is vital to society, responsibility cannot be replaced by the mean position of rule-observation. Further, in practical terms, the over-proliferation of prescriptive guidelines generally leads people to routinely circumvent the rules and moral sensibility as soon as personal advantage can be gained (see “bending the rules”, above).

Naturally, ethics has provided a plethora of definitions that can be combined into an “idea of the good”. The key point is that the ethics should be judged in relation to the task they are to fulfil in terms of philosophy, or a reflective orientation in the world. In principle, ethical problems occur when we are asked to do something, that is, when we feel we ought to do or should do something, but our evaluation of the situation in which we should act is ambiguous. The next problem is whether we can be persuaded that what we should do is meaningful and that it does not conflict with our basic values. Frequently these are not conscious decisions, but we may feel a certain course of action is not acceptable, but be unable to specifically state the values it compromises. Evaluating the measures and the outcome of applying these measures/rules is of central importance because our natural ethical and moral sensibilities require compatibility with our “everyday values”. Naturally, this may change in particular circumstances, if, for instance, we are thinking of “impaling our foes on stakes in war”. So, the point is to develop moral sensibility. Human beings must be alert as to whether what they see or observe is compatible with the inherent values that determine their everyday life. In recent times, of course, something has become inverted and one has the impression that we cannot achieve a fulfilled life, but merely own and consume things. We seek fulfilment with the help of luck, immediate satisfaction and consumer goods. It is widely held that people are better off without having a sensibility for our fellow humans. Indeed, sensibility/sensitivity is considered a weakness! We are not strong enough! Hence, we are eliminating an important aspect of the positive empirical values of ethics, and their capacity to shape areas of reflection and correction. We act as though our economic theories were complete. People assume that knowledge can be isolated within a calculus and used without us ever having to know or understand the significance of the rules of that calculus.

Constraints and the development of sensitivity

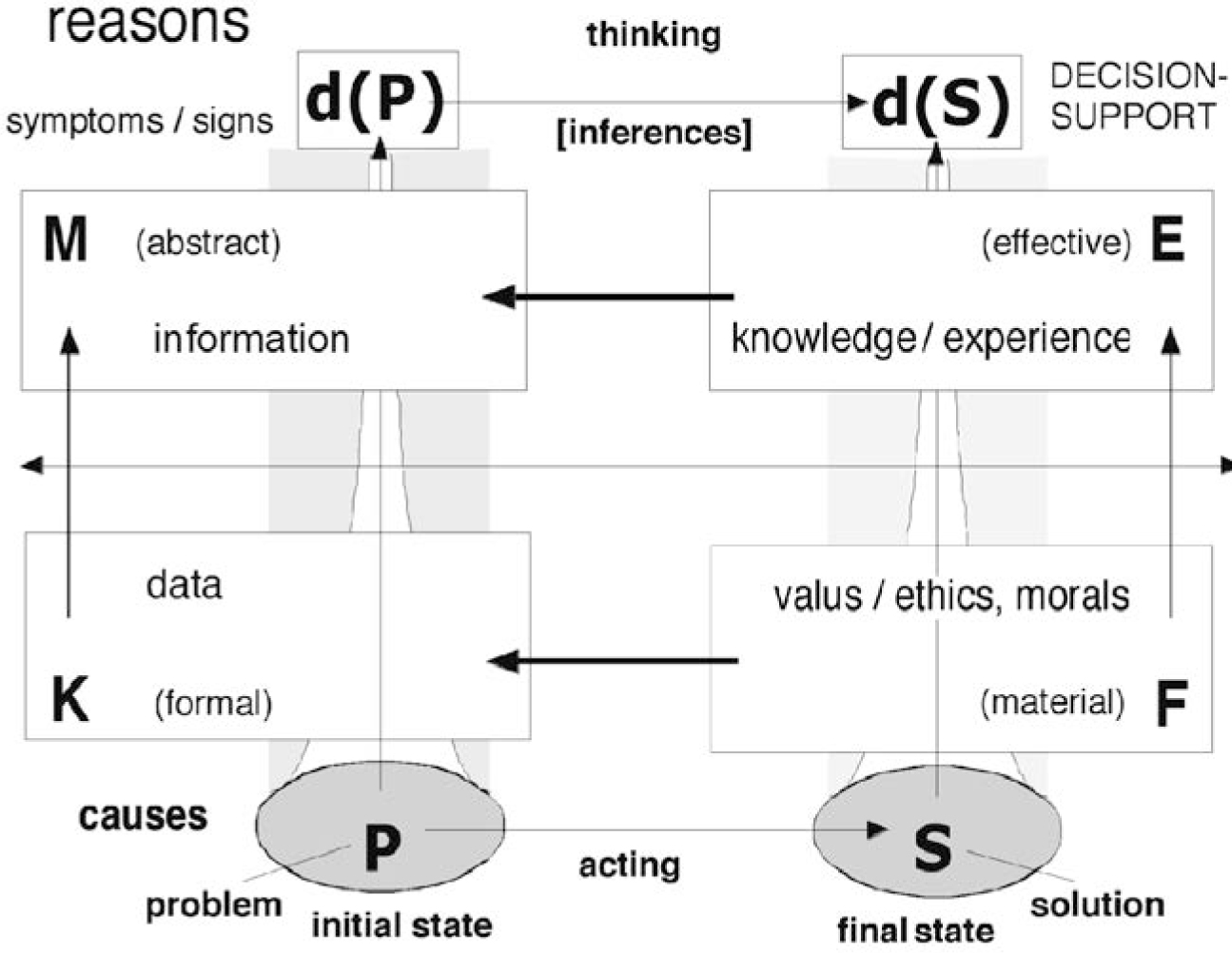

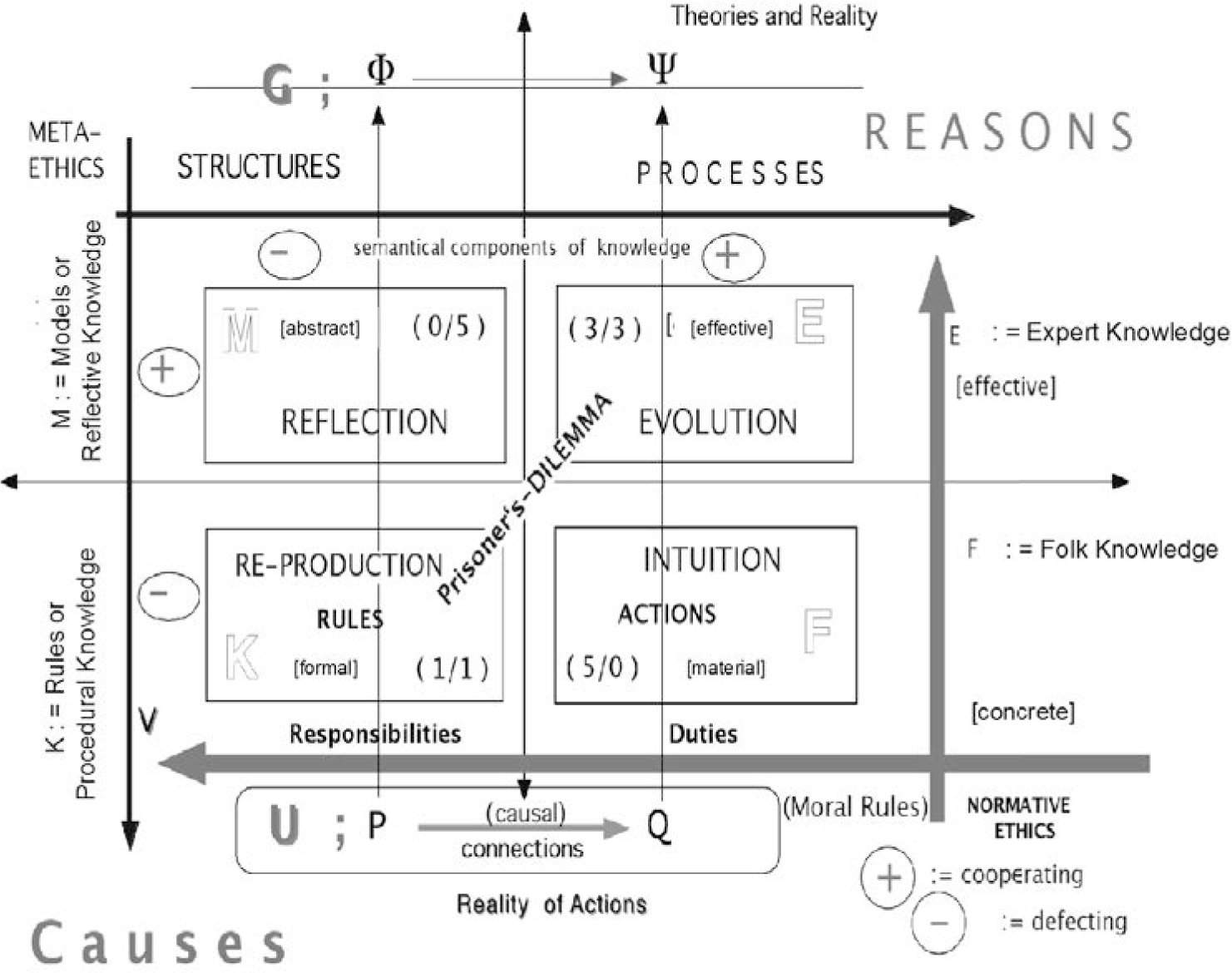

Figure 4 is a visual explanation of the kind of reasoning that is essential for us to advance our reasoning. It contains four background-knowledge areas and uses four-dimensional semantics in an extension of the work by Gerhard Gentzen, Evert Beth and others.

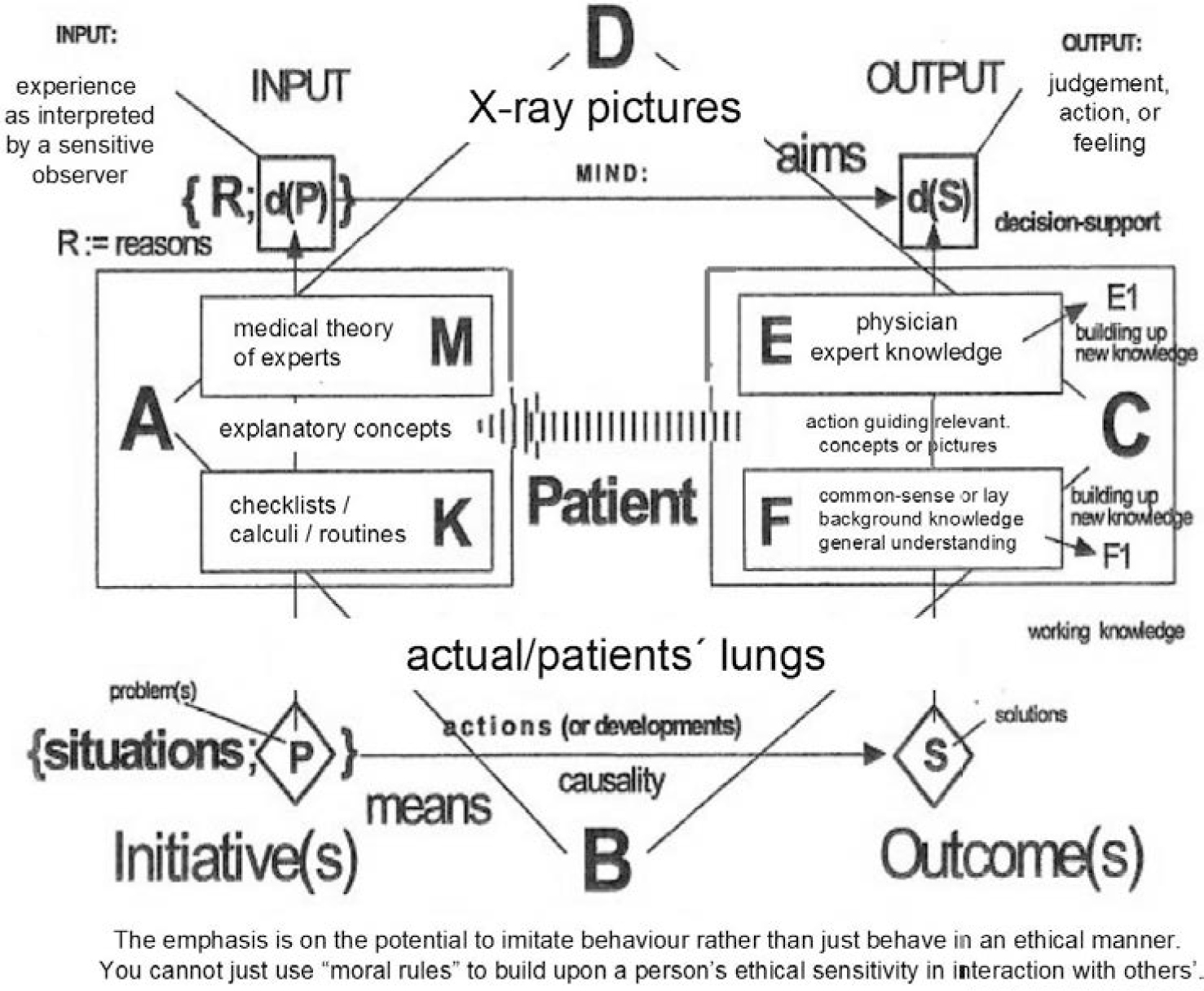

Let us consider three examples. In the first, a patient sees a physician, a renowned specialist, for a lung examination. Looking at Figure 5 and/or Figure 6, the patient might think about the situation in the following way: she is in state P (medical problem) and has her lungs examined, perhaps by x-ray. The specialist looks at the x-ray results in d(P) and recommends a medical procedure (treatment) that will bring about a stage in the disease or a state S (of the lungs) which is considered to be an improvement on P, the original state, and this new state is captured by a future x-ray d(S) (output), an image which would represent outcome S (possibly positive). What is it that links d(P) and d(S)? The physician’s experience and sensitive interpretation of the patient’s symptoms primarily. But in order to select [d(S)] the right image out of all the x-rays available to him, he may have developed a set of “rules” or techniques and checklists to ensure he obtains the approved or standard results. These rules (represented by field K in the diagram) may then be used by assistants who are less highly-trained (and/or motivated) and have less, or perhaps only lay, background knowledge F (in understanding x-rays) and their use. The triangle E/K/F portrays the analysis and depiction of the situation. The meaning/significance/importance of M (explanatory/meta-knowledge/reflective and corrective knowledge) will be discussed below.

Four-dimensional semantics as a means of analysis. F = folk knowledge, communal knowledge; E = expert knowledge, experience; K = calculi, rules/routines/ checklists; M = meta-knowledge, knowledge through models, explanatory knowledge.

X-rays and ethical argumentation (the influence of ethical considerations in light of Moravcsik’s work).

This analysis of the x-ray situation would also hold in our second example. An experienced executive at E, possessing explanatory and operative knowledge, that is, action-guiding and descriptive knowledge, gives his team instructions and they obey his orders (background knowledge K) and perform actions based on their own lay background knowledge F. The difficulty lies in quantifying what background knowledge, experience, sensibility and responsibility the team require to best achieve situation S, the goal of the prescribed/analysed parameter value d(S).

Communication between you and me relies upon assumptions, associations, communalities and the kind of agreed shorthand, which no-one could precisely define but which everyone would admit exists. That is one reason why it is an effort to have a proper conversation in a foreign language. Even if I am quite fluent, even if I understand the dictionary definitions of words and phrases, I cannot rely on a shorthand with the other party, whose habit of mind is subtly different from my own. Nevertheless, all of us know of times when we have not been able to communicate in words a deep emotion and yet we know we have been understood (Winterson, 1995, pp. 79-80).

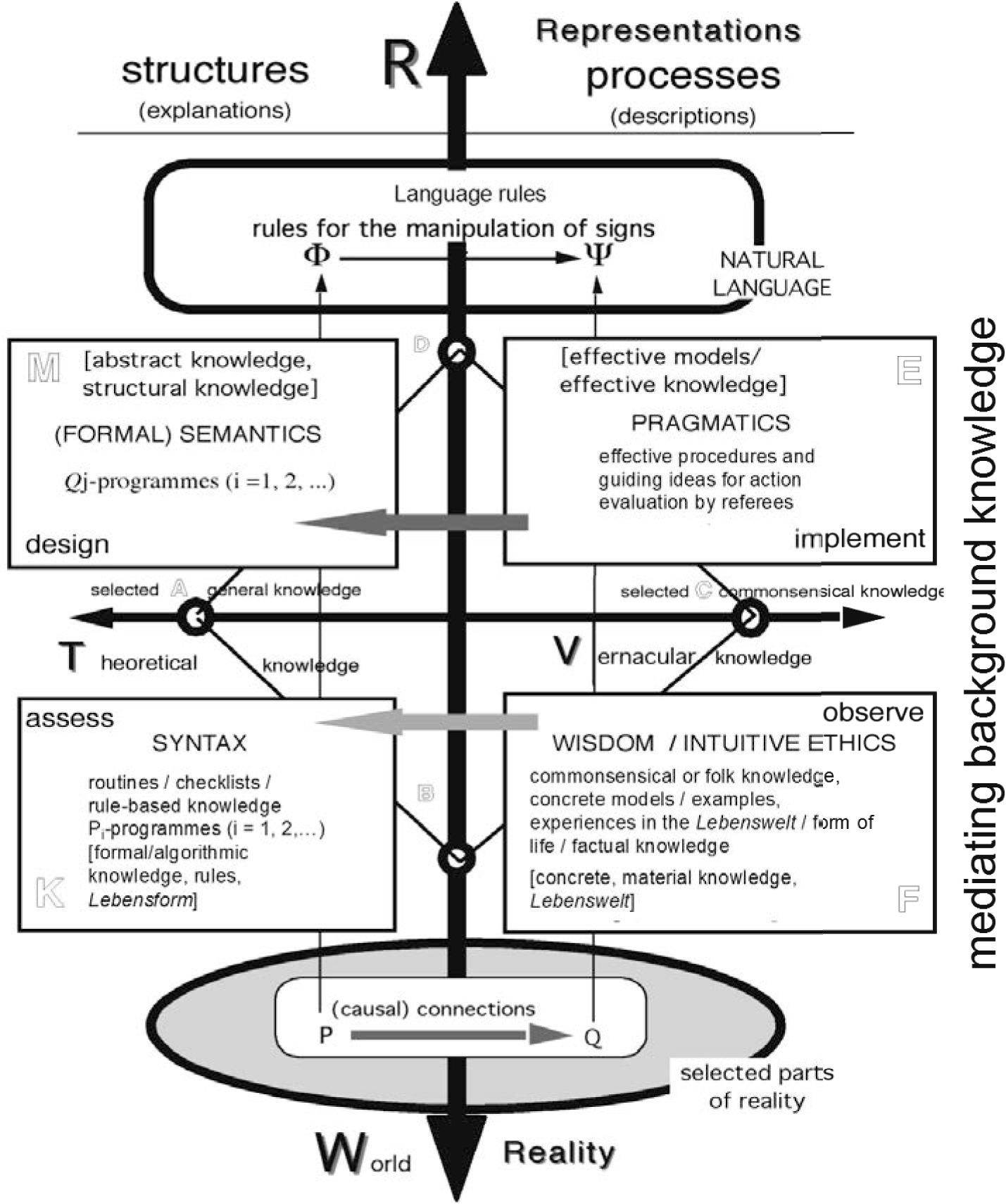

The original diagram that appears in Figure 8 is a simplified meta-representation of communication that combines linguistic and non-linguistic elements. Most importantly it accounts for how understanding comes about through the interpretation of signs via different components of background knowledge and considers the dynamics under which knowledge is conveyed and meaning altered. “Knowledge” (e.g. implicit knowledge) results from the mutual relationships between the different components of background knowledge. “Knowledge” reveals itself through the handling of implicit knowledge. “Knowledge” emerges through the relations between things. “Knowledge” mediates language and reality. It defines the way in which linguistically encoded information is handled and determines the relations between language and reality.

X-rays and ethical argumentation

Basic Language, Information and Reality (LIR) model or theoretical diagram – possibilities in communicating facts, knowledge, feelings and “experience”.

If knowledge (e.g. belief systems that determine the acceptance or persuasive power of ethical arguments) is to be communicated from one party to another, the recipient’s background knowledge (see E, F, K, M in the LIR model in Figure 9) must be considered in all its multiplicity. If the intention is to communicate the transition of state P to a new state, state S=Q (in the world, in an attitude, in understanding, in knowledge), or to make it explicit or even create it (in the recipient), we must be clear about the means of representation R (e.g. language) to be used and about which background knowledge components relate the signs in R to the sections of the world in W. The transition from P to S=Q is reflected linguistically (in an argument), and also therefore by communicating the acceptance of the transition of Φ = d(P) to Ψ = d(S), that is, it is reflected in the admission of the relationship between the signs assigned to the (more-or-less real) state-transitions P and Q=S in the realm of representation R [or D = Darstellung]. This acceptance in the realm of representation R can be strengthened by deliberately changing the components of the background knowledge responsible, as a last resort, for it being approved and endowed with meaning. Whether we actually accept and therefore successfully communicate the knowledge (especially when dealing with creating and conveying new views, frames of reference, etc.) depends on the interplay between the respective components of our background knowledge. Here, the relationship between theoretical knowledge T (selected general knowledge A, as in the left of the x-axis) and vernacular knowledge V (communal or common-sense knowledge C, as in the right of the x-axis) is decisive, since it determines the fine-tuning of new and old knowledge in selected area in the world W [or B = Bereich, cf. Rudolf Carnap] (as in the section of world/reality, lower part of the y-axis) and representation R (as selected representation, upper part of the y-axis). It is via the background knowledge that value-judgments or general ethical considerations, human values and the aims of handling the new “knowledge” are accepted and affect the handling of the knowledge and information.

Language, Information and Reality (LIR) model or theoretical diagram.

This will be illustrated as follows.

Computer poetry and the drummers’ example versus deep blue, or mixed up causes and symptoms

When the basics of Language-Information-Reality (LIR) as an expression of multidimensional semantics were in their infancy (there are at least four components of meaning to be considered which need not be taken into account together all the time), we invented a surrealistic example relating to the computer-aided production of poetry, hypothesising about what would be needed to fake an understanding of the “meaning” of the poems. At the time, the example was technically advanced in its field, but Max Black thought it a good description of the “reality” of the refereeing system used in poetry journals. The essential point about the LIR scheme was that its K to M evaluation function that structures models at M (in classical Tarskian semantics, see Jane Bridge’s Beginning Model Theory) could be used to strictly mechanically evaluate the “meaningfulness” of poems; hence, the meaning would not be expressed literally, but coded somehow. This contrasts with journal referees who have to evaluate poems according to their understanding of the content and express the meaning. The question was: what would happen if the referees at M were replaced by an evaluation program? In what way could the explanatory encoding of meaning be used to freeze a certain contemporary literary taste (and when would the revolution of the next generation of poets begin)? If one looks very carefully, it becomes evident that the same strategy was eventually successfully used in the programming of the Deep Blue chess program to beat human masters of the game. However, the point is that the “meaning” (or evaluation of the situations in a game of chess) is frozen, which is linked to Gödel’s assertion, unlike Turing’s, that meanings can evolve (specifically that an intimate knowledge of abstract mathematical terms could be used to obtain a new understanding that was essential to it being properly applied). No-one knows which evaluation functions Deep Blue understands. What if Deep Blue were to be used as an expert system for training chess students? A clearer example is that of medical expert systems: If students are only trained by the system and have no other opportunity to gain corrective experience, they will end up being as good as the program. If the medical expert system has a success rate of 80%, the remaining 20% will somehow be lost. However, another “ironic” (and therefore quite realistic) illustration can be used, which could perhaps be considered a reductio ad absurdum picture of the simple re-instantiation of natural science to the study of the mind—in this case meaning.

Considering meaning, the idea is whether someone could interpret the meaning of messages communicated through drums without being in contact with the senders or being able to communicate with them in any way other than through the drums, or the sound of them? The only technical equipment allowed would be video cameras so the resulting behaviour could be watched, and special microphones with loudspeakers to produce the noise of drums. The difference between the meaning explained with the help of M and the meaning (of the drummed sound) attributed to the sound by the experts at E actually using the drums would have to be made clear. When would it be justifiable to say that a model at M had “understood” the meaning of the noises? “Understanding” may be used both as a theoretical explanatory and literally descriptive or operative concept. We maintain that it is essential to take into account the interplay between the two, that is, between the theoretical and vernacular (background) knowledge.

The core: Consequences and reality

The application of the diagram (see Figure 9) may now be illustrated by means of a military example. Imagine a hypothetical military context in which there is a problem with basic ethical attitudes or intuition influencing the behaviour of soldiers manning a checkpoint. The soldiers have been observed behaving in a discriminative and humiliating manner, throwing documents at the feet of certain civilians. They are “over-interpreting” their orders (and probably defeating the object of the exercise by alienating the population they are tasked with protecting). The aim is to find a solution (to the soldiers’ behaviour) whereby they come to realize, in some sense even intuitively, what they were doing and what the aim of their behaviour is. The rules alone will not suffice! It is through training that they will develop a sensitivity to the situation and learn to apply the rules or orders appropriately. This means they have to clarify the ethics inherent or implicit in what “should” be done. Of course, merely developing this sensitivity is not enough. The process has to begin with rules that correspond to an ethical intuition. Relating this to our multi-dimensional semantics introduced above (Figure 9), we can say that the codified knowledge of experts R(E) and the description of the problem situation d(P), accessible to experts and laypersons with F-background knowledge, will yield (on the basis of logic) a description d(S) of the solution, or state of the goal. One hypothesis could be that if the background knowledge R(F) is expanded or combined with an expert system K(E), because the rules in K have been explained to some degree by the experts, the results d(S) obtained will be more or less the same as those achieved by experts (think of the X-ray specialists or others). Given d(P), both K and F as well as E will yield d(S), decision support for an action that produces solution/state S if applied to the problem situation/initial state P. However, looking carefully at K(E) one can easily see that a considerable amount of implicit expert/specialist experience is contained in K(E) and used to correct any misapplication of K.

The experts’ special experience that determines the sensitivity of use/application also determines the limits to which K(E) can be applied and what is lacking at F. When we initially pointed out that ethics is ultimately concerned with judging the consequences of our actions on the basis of rules and duties, we wished to stress that it is essential to develop an awareness of how far we can go in applying the “rules”, without overdoing matters, without overstepping the mark or exhausting our resources.

Moral sensitivity has been built up in relation to the “nature of human beings” (in education, in a community, in society). In some cases, this is associated with a desire for a natural world-wide system of ethics. Moral rules could thus be understood as expressing our sensibility, responsibility and basic ethical intuitions. However, we have to understand, and this goes back to Plato and Aristotle and is well-argued by Moravcsik, that rules on their own exercised without a degree of sensitivity and without the option of making considered corrections, cannot guarantee “morally acceptable” action in the long run.

Once more it has to be stressed that morally acceptable action is by no means a luxury but guarantees the survival of mankind, especially if the cogwheels of rationality run idle (“rational fools”, with reference to Sen, 1977) while philosophers and scientists remain safe and secure in the rarefied air of their abstractions. In this case, referring to the diagram in Figure 9 again, only the FKE triangle is used to select and determine suitable actions. If this leads to the conclusion that only a dialogue between E and F is required, one that establishes the necessary “sense-making” for the use of routines and schematic knowledge codified in K, then we may well be stranded again with only a “recipe” and have failed to understand the “generalizability” of the solution (or that the solution could be used in other situations when identifying/constructing an essential common structure). In terms of practice, the mechanical use of routines implies that three essential points are missing: (i) The use or applicability of routines K(E) (or of expert systems/codified systems of moral rules, etc.) has to be tested in relation to the background knowledge or experience of the people who undertake the “role” of F; (ii) Laypeople and experts have to talk to each other and learn to “deal” with K together—although this does not mean that laypeople have to build up/learn the same knowledge as the experts; (iii) The experts have to learn to access the common-sense knowledge/intuitions laypeople have (e.g. develop more social competence), that is, they have to enrich their epistemic resolution level. It is important to note that the relation between F and E is far greater than that between master and apprentice.

The idea that knowledge F (even ethical intuition) needs to be trained leads to reconsideration of what is really responsible for the success of expert solutions when sensitivity to applying routines (knowing about the implicitly communicated limits of their application) needs to be explained. In this case, the issue has to be looked at from the outside, because otherwise we will only have what experts believe to be essential to the solution or, as in paternalistic medical practice, we will only be told what they think a layperson needs to know, just as doctors sometimes tell us what they believe they know about us, where they think we should feel pain. This eventually leads to the construction of structural knowledge (structural models, as in Tarskian semantics and their modern extensions) to codify or explain the knowledge prevailing/residing in E. This means a model has to be constructed at M (meta-knowledge, explanatory knowledge which needn’t be literally descriptive or action-guiding) that is technical but not descriptive and can be said to “understand” the knowledge at E. This kind of knowledge M can be termed “theoretical explanatory” in contradistinction to the descriptive and operational knowledge at E/F and K.

Thus, a (single) helix, or just a spiral, of the development and evolution of knowledge has been actualized (cf. Nonaka, 1994), since the knowledge constructed at M, used as R(M) in arguments, can be used to select initiatives/measures that identify knowledge experience and so forth so as to enrich F (using the appropriate language and epistemic resolution level) such that, in many normal cases, F and K will produce solutions close to K and E, meaning that experts can be liberated from certain ordinary work and should be able to concentrate on important new matters. If we again combine this procedure with ethics matrices (Figure 7) to look at the effect the evaluation components have, we see that at F it is the actions and duties that matter, while at K it is the schemata for action and consequences of actions, and at E the principles of middle reach (see Beauchamp & Childress, 2001), such as Kant’s categorical imperative—regulative ideas, rules and duties (deontology). At M, the final field, the “supervising ethical principles” concerning both rules and consequences have to be fixed; these are sometimes theoretical explanatory ones and which will acquire a specific meaning in an effective realm of action.

If we consider these investigations in relation to thinking on the prisoner’s dilemma (see Figure 10), we can correlate moral-action and areas of reflection with the familiar norms of a two-person game with no repetition (the simplest kind), that is, one with certain numbers from the pay-off matrix. Thus, we have the idea of interplay between cooperation and defection, combined with a general ethical analysis that is essential to the understanding of mankind at K, with its syntactical area of action and minimal background knowledge corresponding to (1/1)—both agents defect and do not cooperate due to some misunderstanding in the theory behind the prisoner’s dilemma. Field F equals (5/0) since a person who acts in accordance with his/her duties and cooperates will easily lose—the defector wins. If that person only thinks in M (knows explanatory rules) and about the consequences, he or she will lose against someone who thinks solely in terms of the rules and defects whenever seems appropriate—(0/5). At E, maximum cooperation is possible—(3/3).

The prisoner’s dilemma.

On the other hand, when we explore the “nature of mankind” in any kind of depth, it becomes obvious that some form of altruism may have been responsible for both the development and survival of Homo sapiens. That would mean that our natural or intuitive feelings, our sensitivity to and cooperation with our fellow humans, requires constant development and adaptation in area E through evolutionary dialogue with F and reflective analysis via M. Our effective ethical principles, formulated at E, should only be confined to a middle reach that would enable the system to remain flexible and adaptable. Thinking back to the first heart transplants (see above), one of the principles at M had to be changed to allow for a different conception of death. Similarly, we can consider the example of enemies (the checkpoint) and which of the common-sense conceptions at F had to be changed, what remained constant at M and in which way experts at E would have to argue differently to install new rules such that enemies no longer exist. The new rules therefore have to be anchored in a changed sensibility in our common-sense thinking.

As a preliminary conclusion, we can state that procedures and argumentations may be analysed but they need not be prescriptively action-guiding. Instead the logistics/routines and instructions at K have to be selected/explained in such a way that allows for swift, safe action in normal situations, whilst retaining an awareness of and alertness as to how far we can go in borderline cases. This means that when justifying and leading (in military contexts) we need to develop a feeling for which selection principles (thin, or rather, abstract ethical concepts) have to be identified and explained at M to enable the operationalizations or instructions at F and E and ensure flexible use.

If this sounds like squaring the circle, we should recall that the four fields are to be considered as semantics for solutions and argumentations that provide justification in decision-support situations. They have a different logical status and are not just simple procedures. In its semantic role, knowledge F is both concrete and material. Knowledge K is semi-formal. Knowledge E is effective, that is, it is both descriptive and explanatory, just as the categorical imperative seeks to be both. The same holds true of the understanding of algorithms in a computer program. They seek to express logical and procedural aspects but are also considered (cf. Aristotelian logic) to have causal significance (in fact, we should distinguish between conditional and causal meanings in “if… then…” expressions and be aware of areas in which they merely appear to coincide.) The final field M concerns the abstract, and therefore most general, semantic component in the context of logical conclusions. The relation between F/E and K/M is—logically speaking—“many-to-one”, meaning that “one” abstract concept at A=K/M may correspond to, or be operationalized by, “many” possible realizations in C=F/E. Once more: the correct connection between moral rules and ethical sensibility is inescapable if one seeks to develop a flexible system that is able to survive in the long term.

The result? An example of game theory has been turned into a piece of advice for action.

Conclusion: Pragmatic incompleteness

Starting from the fact that our ethical theories are not literally descriptive or action-guiding and are therefore, in a broad sense, not “complete”, it becomes clear that the application of rules is in need of some additional mode of sensibility if it is to be able to correct misapplications. This kind of incompleteness shows up in certain inadequate rules. In some cases, explanatory conceptions are wrongly turned into rules (see the prisoner’s dilemma, Figure 10). From a philosophy of science viewpoint, we can argue that theoretical and explanatory models must not be turned into operationally conceived systems for guiding actions. If we are in need of one thing, then it is the possibility to make corrections, which again calls for a new or re-established kind of sensibility.

References

Barwise, J., & Etchemendy, J. (1999). Language, proof and logic. Stanford: The Center for the Study of Language and Information Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Barwise, J., & Perry, J. (1999). Situations and attitudes. Stanford: The Center for the Study of Language and Information Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bohm, D. (1996). On dialogue. New York, NY: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Chandler, D. (2013). Resilience ethics: Responsibility and the globally embedded subject. Ethics & Global Politics, 6(3), 175-194.10.3402/egp.v6i3.21695Search in Google Scholar

Crouch, C. (2015). The knowledge corrupters: Hidden consequences of the financial takeover of public life. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Dewey, J. (2012). Unmodern philosophy and modern philosophy. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gruen, A. (2003). Verratene Liebe – Falsche Götter. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.Search in Google Scholar

Harari, Y. N., & Perkins, D. (2014). Sapiens: A brief history of humankind. London: Harvill Secker.Search in Google Scholar

Hilbert, D. (1903). Grundlagen der Geometrie. Leipzig: Teubner.Search in Google Scholar

Hofstadter, D. R. (1998). Tit for tat. Kann sich in einer Welt voller Egoisten kooperatives Verhalten entwickeln. Spektrum der Wissenschaft, 1, 60-66.Search in Google Scholar

Michaels, A. (1997). Fugitive pieces. London: Vintage.10.7326/0003-4819-128-11-199806010-00007Search in Google Scholar

Moravcsik, J. (1980). On what we aim at and how we live. In D.Depew. (Ed.), The Greeks and the good life (pp. 198-235). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.Search in Google Scholar

Moravcsik, J. (2003). Was Menschen verbindet. (Translated and edited by Otto Neumaier). St. Augustin: Academia Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5, 14-37.10.1287/orsc.5.1.14Search in Google Scholar

Putnam, H. (1981). Reason, truth and history. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511625398Search in Google Scholar

Putnam, H. (2005). Ethics without ontology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.10.1515/9780674042391Search in Google Scholar

Schlick, M. (1918). Allgemeine Erkenntnistheorie. Berlin: Julius Springer.Search in Google Scholar

Sen, A. (1977). Rational fools: A critique of the behavioral foundations of economic theory. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 6(4), 317-344.Search in Google Scholar

Weick, K. E. (1979). The psychology of organizing. (2nd ed). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.Search in Google Scholar

Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe K. M. (2015). Managing the unexpected: Sustained performance in a complex world (3rd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.10.1002/9781119175834Search in Google Scholar

Winterson, J. (1995). Art objects. London: Jonathan Cape.Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Institute for Research in Social Communication, Slovak Academy of Sciences

Articles in the same Issue

- Care of the self in the Global Era

- Reflexivity and globalization: Conditions and capabilities for a dialogical cosmopolitanism

- Aesthetic cultivation and creative ascesis: Transcultural reflections on the late Foucault

- Careful becomings: Foucault, Deleuze, and Bergson

- Self-appropriation vs. self-constitution: Social philosophical reflections on the self-relation

- Care of the S: Dynamics of the mind between social conflicts and the dialogicality of the self

- Self-limitation as the basis of environmentally sustainable care of the self

- The deficits of critical thinking in the postmodern era

- The inner conflict of modernity, the moderateness of Confucianism and critical theory

- Sensibility in applied ethics

Articles in the same Issue

- Care of the self in the Global Era

- Reflexivity and globalization: Conditions and capabilities for a dialogical cosmopolitanism

- Aesthetic cultivation and creative ascesis: Transcultural reflections on the late Foucault

- Careful becomings: Foucault, Deleuze, and Bergson

- Self-appropriation vs. self-constitution: Social philosophical reflections on the self-relation

- Care of the S: Dynamics of the mind between social conflicts and the dialogicality of the self

- Self-limitation as the basis of environmentally sustainable care of the self

- The deficits of critical thinking in the postmodern era

- The inner conflict of modernity, the moderateness of Confucianism and critical theory

- Sensibility in applied ethics