Abstract

The bone microenvironment is a complex tissue in which heterogeneous cell populations of hematopoietic and mesenchymal origin interact with environmental cues to maintain tissue integrity. Both cellular and matrix components are subject to physiologic challenges and can dynamically respond by modifying cell/matrix interactions. When either component is impaired, the physiologic balance is lost. Here, we review the current state of knowledge of how glycosaminoglycans – organic components of the bone extracellular matrix – influence the bone micromilieu. We point out how they interact with mediators of distinct signaling pathways such as the RANKL/OPG axis, BMP and WNT signaling, and affect the activity of bone remodeling cells within the endosteal niche summarizing their potential for therapeutic intervention.

Introduction: the bone marrow microenvironment

The bone marrow (BM) microenvironment is a complex structural and biological system, which constitutes hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells of multiple lineages, and the bone extracellular matrix further sustained by a sinusoidal blood supply. One of the key functions of this microenvironment is the maintenance of hematopoietic homeostasis by controlling the proliferation, self-renewal, differentiation and migration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSCs). Driving both HSC self-renewal and differentiation, two very distinct cell fates, is made possible via the formation of specific niches within the bone microenvironment (Cordeiro-Spinetti et al. 2015). The cellular activity within these niches is regulated by an intricate interplay of cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic cues, including cues from the BM microenvironment, which is referred to as the stem cell niche. The concept of a niche was first proposed in 1978 (Schofield 1978) evolving the concept of hematopoietic inductive microenvironments (Trentin 1971; Wolf and Trentin 1968). Ever since then, the cells that actually contribute to the niche maintenance have been heavily debated. Many candidate niche cells have been postulated. Amongst those, two distinct cell types were however identified to be crucial (Purton 2008): endothelial cells (Kiel et al. 2005) and osteoblasts (Calvi et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2003). Whether the endosteal (osteoblastic) and the vascular niche (endothelial cells) represent two distinct or overlapping niches is still under debate (Purton 2008). However, it is generally acknowledged that when the regulation of either niche is impaired, the entire system deteriorates resulting in a pleiotropy of diseases, e.g. BM failure syndromes. Due to the complexity of the topic, this review will focus on the cellular components that govern changes in bone quality: the endosteal niche and its most important signaling pathways.

The endosteal niche

The endosteal niche near the inner bone surface, particularly at the metaphyseal spongiosa is the site of active bone remodeling (Lévesque et al. 2010). It is populated by osteoblastic lineage cells, mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and osteoclasts (Le et al. 2018) organized in functional units. Bone integrity is maintained through the balanced activities of bone resorbing osteoclasts, bone forming osteoblasts and mechanosensing osteocytes (Crockett et al. 2011). Upon stimulation by different signals such as micro-fractures these cells can release factors such as receptor activator of nuclear κB ligand (RANKL) that triggers osteoclast formation and differentiation. In their active state osteoclasts then dissolve and degrade the bone matrix by acidification and release of lysosomal enzymes (Rucci 2008). In turn, the bone matrix resorption leads to the release of several growth factors including bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and transforming growth factor β (TGF β) (Rucci 2008). These factors recruit osteoblasts to the resorption site producing new bone matrix (Rucci 2008). Some of these osteoblasts become entombed during the formation phase and eventually become osteocytes (Bonewald 2011; Rucci 2008). The precise interaction of their cell activity maintains the homeostasis of the bone.

Glycosaminoglycans in bone tissue

In addition to cells, the extracellular matrix (ECM) serves as a scaffold and was long thought to be relatively inert. However, over time it has become apparent that both its quality and components serve essential roles in maintaining structural and functional integrity. In bone, the individual ECM composition varies. Roughly, it is composed of up to 50–70% of calcium and phosphate and 20–40% of organic components. The predominant constituent of the organic ECM are large, structural proteins such as collagen complemented with proteoglycans (PGs), glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and other proteins. While the inorganic and proteinaceous components of the bone ECM have been studied in great detail, GAGs have only slowly gathered attention.

GAGs are long, linear polysaccharides, composed of alternating monosaccharide residues. Their sequence varies with regard to glycosidic linkage, saccharide composition, and chemical modification. Two main types of GAGs can be distinguished: unsulfated GAGs (hyaluronan) and sulfated GAGs (heparin and heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, dermatan sulfate and keratan sulfate) (Gandhi and Mancera 2008). Bone GAGs consist of mainly chondroitin sulfate (CS) and small amounts of hyaluronan (HA) (Claassen et al. 2006; Salbach et al. 2012b) and were reported to undergo continuous changes during MSC differentiation but are also affected by aging (Grzesik et al. 2002) and pathologies such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, where changes in GAG pattern also contribute to disease aggravation (Mania et al. 2009).

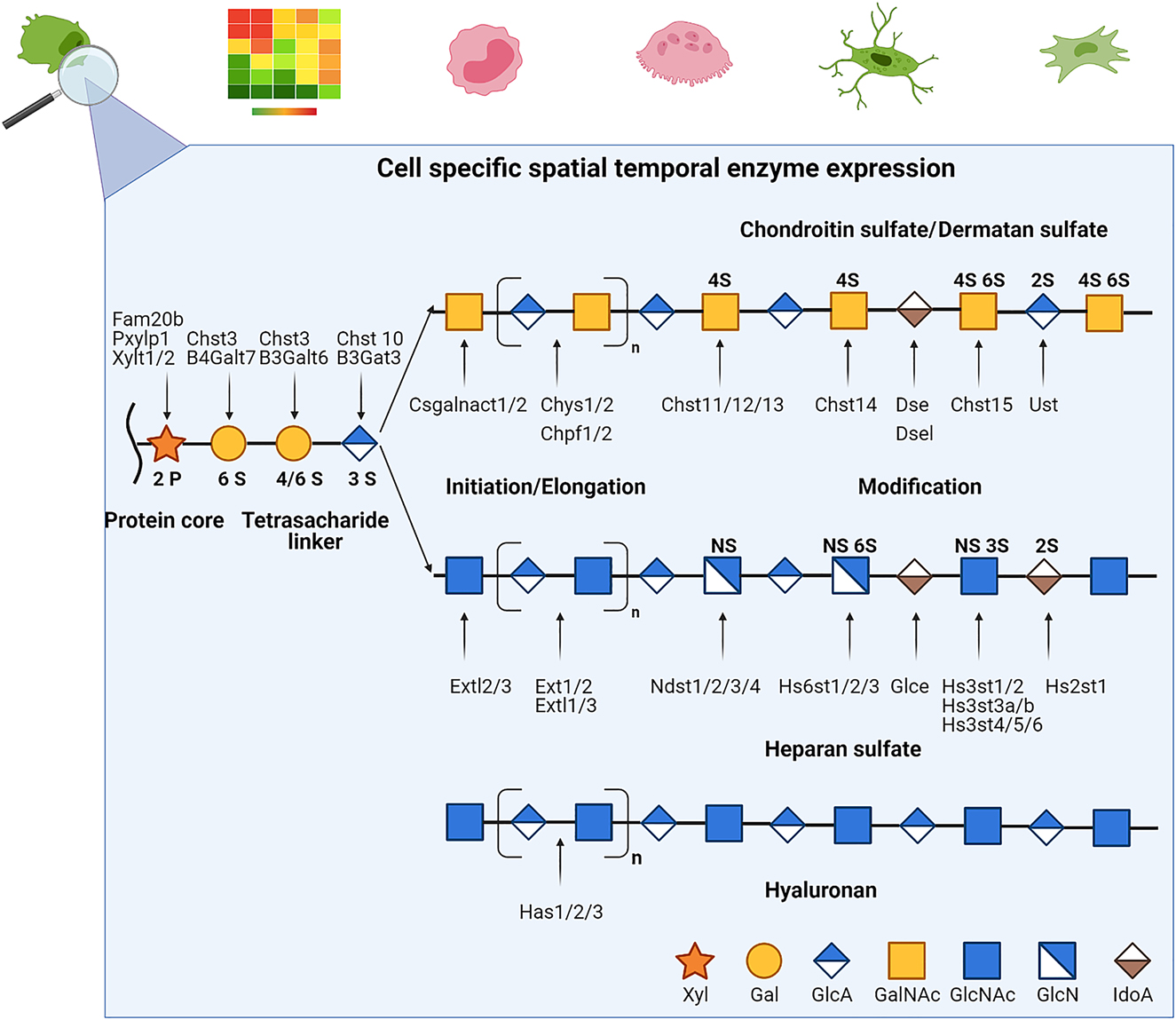

Their ultimate structure is not encoded in the genome but is rather the product of many interdependent synthesis pathways. Depending on the expression pattern of the many interchangeable synthesis and modification enzymes, they can be very heterogeneous in size and sulfation pattern (see Figure 1). Consequently, their scientific investigation has been challenging and may yield contradictory results if the exact GAG formulation was not specified.

Simplified glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis.

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are non-templated polymers synthesized by the sequential action of enzymes whose presence are dependent on the cell type, developmental process or pathological composition of the cell. The basic subunit of a GAG is a disaccharide whose sequence can vary in the basic composition of the saccharide, the stereochemistry of the linkage, their acetylation and sulfation patterns. After variable elongation periods the final chain lengths can range from 1 to 25,000 disaccharide units. The addition to different proteoglycan core proteins at variable density and composition further adds diversity that vastly exceeds that of proteins and DNA.

With the exception of HA, GAG chains are usually covalently linked to a core protein forming PGs, where the properties of the GAGs tend to dominate the properties of the entire molecule. PGs are ubiquitously expressed on cell surfaces forming a glycocalyx and in the extracellular matrix where they can influence many aspects of cell biology through interactions with chemokines and other proteins. Also the polyanionic GAGs attract bivalent cations such as Ca2+ resulting in a high hydrodynamic volume combined with low compressibility, creating a size-selective barrier in which only small molecules can freely diffuse, thus restricting the bioavailability of larger molecules (Salbach et al. 2012b). By incorporating water into the matrix (Hua et al. 2020) and by interaction with collagen fibres (Bertassoni and Swain 2014), PGs and GAGs may further function as critical mediators of the mechanical behaviour of bone (Bertassoni and Swain 2014; Hua et al. 2020). As part of the ECM and the cells’ glycocalyx, GAGs furthermore interact with diverse proteins, and thus modulate the activity of various key signaling pathways.

Niche modulating pathways

While at first glance, tissues such as bone, skin or nervous tissue appear very different, molecular pathways considered to contribute substantially to niche maintenance are redundant (Ferraro et al. 2010; Ross and Christiano 2006). These pathways include wingless-type MMTV integration related proteins (Wnt), BMPs, runt related transcription factor (RUNX), Notch, and several growth factors such as FGFs, platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), insulin growth factor (IGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transforming growth factor (TGF). However, it has to be highlighted that even though these signaling molecules are operative in several organs they can serve different roles according to the specific niche (Ferraro et al. 2010). Both Wnt and BMP signaling appear to be highly conserved controlling self-renewal and lineage commitment (Ferraro et al. 2010). How GAGs affect these systems is not yet fully elucidated. However, due to their ubiquitous expression and their multifaceted interaction with key regulating molecules a functional role is highly likely. Here we provide an overview on the current state of knowledge that may provide opportunities for future therapeutic intervention.

GAG interaction with Wnt signaling

Wnt ligands activate at least three distinct intracellular signaling cascades: the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway, or the Wnt/planar polarity pathway (Westendorf et al. 2004), whereas most data exists on the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Accordingly, most data on PG and GAG interactions with this pathway is derived from studies on canonical Wnt signaling. Unpublished transcription factor activation studies from our group, however, suggest a functional role in non-canonical Wnt signaling too as differently sulfated GAGs elicited specific responses in vitro (AP-1 and NFATc1 promoter activation). The pivotal role of Wnt signaling in bone biology became apparent when loss and gain of function mutations in one of its co receptors LRP5 (low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5) were linked to osteoporosis or high bone mass phenotypes, respectively (Boyden et al. 2002; Gong et al. 2001; Rucci 2008; Van Wesenbeeck et al. 2003). Upon engagement with Wnt ligands, LRP5 interacts with the frizzled receptor and the complex triggers the intracellular assembly of a protein complex including Axin and Disheveled inhibiting the activity of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β). This in turn prevents β-catenin phosphorylation, which accumulates and at a certain concentration translocates to the nucleus where it engages Tcf/Lef family of transcription factors to regulate the expression of Wnt target genes. This system is finetuned by several factors that either act as soluble decoy receptors (e.g. secreted frizzled related proteins(sFRP), Wnt-inhibitory factor-1(WIF-1)) or block the receptors from Wnt ligands (e.g. dickkopf-1 (Dkk-1), sclerostin) and may induce receptor internalization (e.g. Dkk-1). The complexity of this pathway provides numerous possibilities for GAG interactions. Many key molecules of this pathway contain heparin (Hep) binding sites (e.g. WNT family member 3A (Wnt3a), Sclerostin, Dkk-1, WIF-1, sFRP (Malinauskas and Jones 2014)) and are therefore likely to interact with GAGs. It is well known that Wnt gradient formation is of crucial importance during development and several studies substantiate that during this process optimal Wnt signaling is achieved by association with heparan sulfate (HS) and CS-containing PGs (Baeg et al. 2001; Malinauskas and Jones 2014; Tsuda et al. 1999; Westendorf et al. 2004; Yan and Lin 2009), and is affected by their sulfation status (Lin and Perrimon 1999). Here, GAGs or PGs are often postulated to be part of a receptor complex, help accumulate ligands to the final receptor signaling complex or reduce ligand degradation.

The effects of GAGs on Wnt signaling in the bone microenvironment is less well investigated. Due to the complexity of the many Wnt ligands, receptors and PGs present in the bone niche, literature review as of yet does not allow for a clear assertion: On the one hand, GAGs such as heparan sulfate were shown to potentiate Wnt signaling and increase osteoblast differentiation (Ling et al. 2010a). On the other hand, several reports found a reduction in Wnt activity mediated by HS, Hep, CS and/or CS/HS PGs (Mansouri et al. 2017; Nadanaka et al. 2011), whereas the targeted inhibition of GAG sulfation increased Wnt signaling (Mansouri et al. 2017). In line with this, direct binding studies from our group provide evidence that CS, Hep and synthetically sulfated HA (sHA) reduce canonical Wnt signaling in a sulfate-dependent manner when applied as soluble agents (Salbach-Hirsch et al. 2015). However, as both Wnt activators and inhibitors have GAG-binding capacity the ultimate pathway regulation is up to the availability of the different interaction partners and their affinity for the respective GAG. We found that in the presence of sclerostin and Wnt3a, sclerostin is the preferred binding partner of sHA (Salbach-Hirsch et al. 2015), whereas Dkk-1 was less potent in GAG binding than Wnt3a in vitro (Salbach-Hirsch et al., unpublished data).

Furthermore, target genes of Wnt signaling also include GAG modifying enzymes (Nadanaka et al. 2011). In this context, GAGs probably serve manifold functions in the microenvironment that integrate autocrine and paracrine signals to modulate Wnt ligand and inhibitor availability (summarized in Figure 2).

Manifold actions of GAGs on Wnt signaling.

Several Wnt activators and inhibitors are GAG binding partners. When secreted their diffusion from the producing cell can be hampered by PGs/GAGs of the extracellular matrix or membranous proteoglycans protecting them from degradation, inactivating them (A) or retaining their function at close proximity (B). Increased mediator levels may then in turn change the expression patterns of GAG/PG enzymes resulting in structural changes of GAGs and PGs at the cell membrane and less mediator binding capacity. As a result, mediator diffussion is no longer restricted to the local milieu but can act in a paracrine manner (C). Similar mediator liberation from the cell surface and ECM can be achieved by shedding due to enzymatic degradation of the GAG chains. This can e.g. be trigged during bone resorption or inflammation. The exact role of different GAGs, PGs with single mediating molecules needs further elucidation.

GAG interaction in the RANK/RANKL/OPG axis

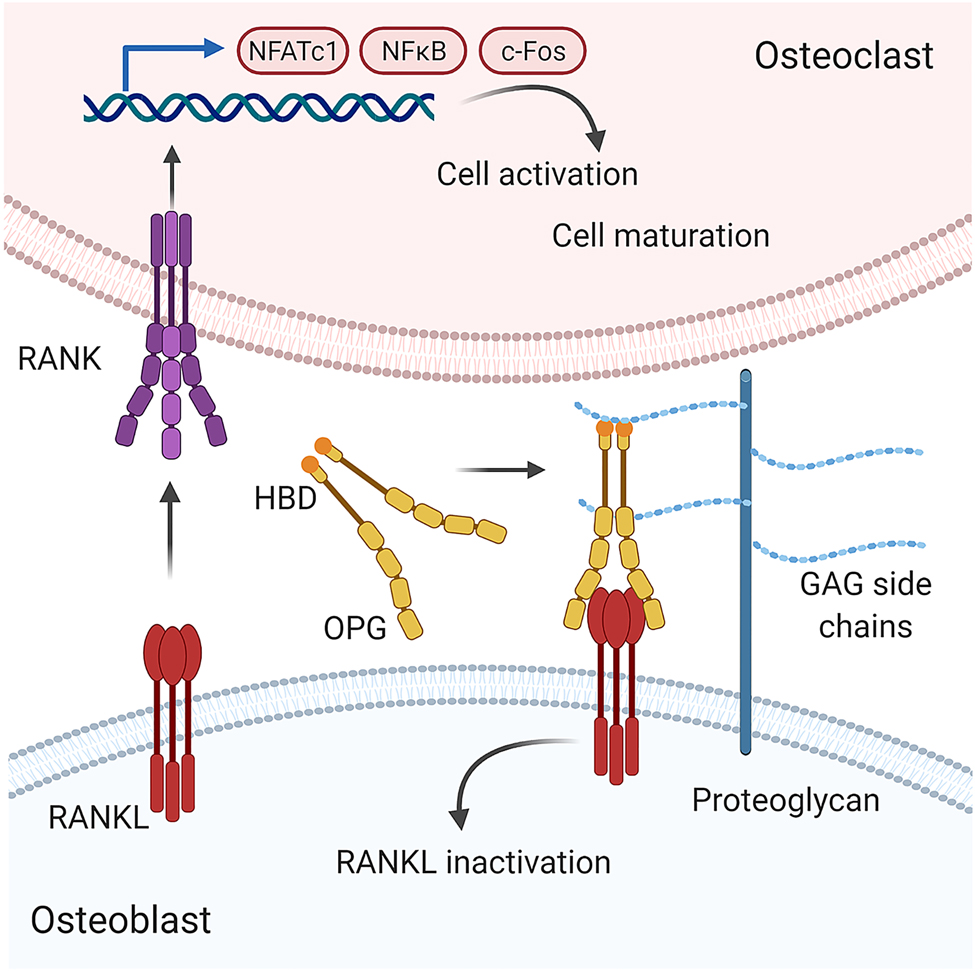

The precise coupling of bone resorption and bone formation activity is crucial to maintain physiological bone. This coupling is achieved by the transcellular signaling of osteoblasts and osteocytes with osteoclasts via the receptor activator of nuclear κB ligand (RANK)/RANKL/osteoprotegerin (OPG) axis (see Figure 3). This signaling is mediated by RANKL, produced mainly by osteoblasts and osteocytes in response to stimuli such as micro fractures. In its cell surface–anchored or soluble form RANKL then stimulates the differentiation of osteoclast precursors by engagement of RANK. As a preventive mechanism against excessive bone resorption, osteogenic cells can express OPG, a soluble decoy receptor for RANKL. Just recently (Ikebuchi et al. 2018) it was shown that this coupling is bidirectional. Osteoclasts can shed vesicular RANK, inducing reverse signaling via RANKL on osteoblasts that enhances osteoblastic bone formation. Several studies have suggested that GAGs may inhibit OC functions through direct interactions with osteoclastic mediators such as RANKL, OPG, and cathepsin K. Molecular docking and surface plasmon resonance analysis revealed that depending on their formulation and sulfation degree GAGs (sHA, CS, Hep) can occupy the RANKL binding site of OPG. In contrast, RANKL did not bind to sHA, CS and Hep (Salbach-Hirsch et al. 2013). Mutagenesis experiments further elucidated the biological relevance of this interaction (Li et al. 2016): HS residues of PGs on the cell surface of osteoblasts bind OPG, facilitate its dimerization thereby altering its conformation. The high abundance of this low affinity receptor enriches the OPG concentration at the cell membrane enabling RANKL inhibition at very low concentrations (see Figure 3). This study also highlights that the presentation of RANKL and HS in its membrane-bound form is of crucial importance as the administration of comparable high doses of the soluble GAG masks these effects. In line, the targeted ablation of HS from osteoblasts was shown to induce a low bone mass phenotype in mice due to enhanced bone resorption upon loss of OPG binding to the osteoblast surface (Nozawa et al. 2018).

Proposed model by which glycosaminoglycans alter the RANKL/OPG system.

The differentiation and activation of osteoclast precursor cells is markedly regulated by the RANKL/OPG axis. Soluble or membrane-bound receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) is produced by osteoblasts and other stromal cells. By binding to its corresponding receptor RANK (receptor activator of NF-κB) on the surface of osteoclast and their precursors gene transcription regulating both osteoclast survival and maturation is activated. Osteoprotegerin (OPG) acts as a soluble decoy receptor for RANKL preventing excessive osteoclast formation. Through binding to GAG side chains of proteoglycans, OPG is brought in close proximity to the membrane-bound RANKL increasing the probability of successful engagement. Binding to GAGs also induces a significant conformational change of OPG, that might further facilitate OPG-RANKL interactions (Li et al. 2016; Théoleyre et al. 2006).

GAG effects on angiogenic growth factors

Recent evidence suggests the vasculature in bone exercises functions extending far beyond its traditional roles in tissue perfusion in maintaining bone homeostasis. Endosteal niche cells are one major source of several critical mediator and their bioavailability too is subject to GAG interactions in the bone ECM. One potent angiogenic factor found in the endosteal niche is VEGF, whose effects on endothelial cells and contribution to several pathologies is well defined. Pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic effects of Hep and other GAGs have been described and linked to VEGF interactions. Recently, a comprehensive molecular study proposed distinct binding models of GAG molecules with the Hep-binding domains of the VEGF dimer (Koehler et al. 2019). Upon binding the high-sulfated GAGs (sHA, CS, Hep) impaired the biological activity of VEGF both by mediator scavenging and receptor blockage. Interestingly, sulfated GAGs (sHA, CS, Hep) alone were shown to promote angiogenesis in a direct cell-dependent manner (Koehler et al. 2019). This again highlights the dual potential of GAGs and that their actions are subject to the presence of GAG-binding molecules in the local environment.

Besides VEGF, osteoblasts are also a source for C-X-C chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), also known as stromal derived factor 1 (SDF-1). CXCL 12 is a key factor of angiogenesis and plays a key role in maintenance of the bone by controlling osteoblast and hematopoietic stem cell activity alike including osteoclast recruitment, differentiation, and activity (Shahnazari et al. 2013; Sugiyama et al. 2006). As observed for VEGF, this chemokines’ activity is also regulated by GAG binding, whereas soluble GAGs (Hep, HS) act as inhibitors (Murphy et al. 2007) but membrane-associated GAGs were shown to promote VEGF signaling (Murphy et al. 2007). As summarized by Lau et al. (2004) the same mechanisms have been observed for a wide range of other chemokines. This review also highlighted that yet another level of complexity of GAG binding to proteins can be added by the fact that chemokine actions in vivo differ concerning their oligomerization status which in turn is facilitated by GAGs.

Likewise, GAGs have very complex actions on the TGF-β1 bioactivity. Koehler et al. demonstrated, that sHA bind the TGF-β1 ligand in a sulfation-dependent manner. The sulfation-dependent occupation of the receptor binding sites then alters the TGF-β1/receptor complex formation either by blocking the interaction of TGF-β1 with its receptor or by partially forming a complex that does not activate the Smad signaling pathway (Koehler et al. 2017). As a consequence, this should lead to reduced bone and vessel quality as TGF-β signaling favors bone and vessel formation.

BMP signaling

Besides TGF-β, many other members from the same structurally related superfamily have critical roles in bone. Out of the circa 40 proteins in the superfamily about one third are known binding partners of Hep and HS with interactions strong enough to be physiological relevant (Rider and Mulloy 2017). These include growth differentiation factors and several members of the subgroup of BMPs. As the name suggests, they were first discovered by their ability to induce bone formation. The basic sequence of the canonical TGF-β/BMP signaling pathway is a linear cascade of TGF-β/BMP ligands binding to their receptors to induce SMAD down-stream signaling, which then translocate into the nucleus where they regulate target gene expression (Guo and Wang 2009; Lademann et al. 2020). Thereby, this pathway controls a plethora of events, including proliferation, differentiation, viability, ECM remodeling, osteoblast-osteoclast coupling and also the production of other key regulation pathways such as OPG and Wnts (Guo and Wang 2009; Lademann et al. 2020). Interestingly, the GAG binding sites among these proteins show considerable diversity that may be the result of the functional evolution of certain family members where GAG binding could represent a fine-tuning mechanism for their biological activities (Rider and Mulloy 2017). If these differences can be mapped to differential functional outcomes after binding to these GAG needs to be further elucidated (Rider and Mulloy 2017). Again, conclusive studies in this area remain limited, as within in vitro and in vivo model systems various interaction partners are present at the same time. However, some instances provide valuable insights into single mechanisms: Hintze et al. (2014) showed that sulfated GAGs (sHA, CS, Hep) interact with BMP-2 in a sulfation-dependent manner as they have also reported for BMP-4 and TGFβ (Hintze et al. 2009; Koehler et al. 2017) but not with the receptor BMPR-IA. The GAG/BMP-2 complex formation then significantly reduces the binding strength to the receptor, which is in line with studies showing reduced BMP2 signaling in the presence of Hep or enhanced BMP signaling after removal of GAG chains from HSPG (Miguez et al. 2011). Similar results were observed for BMP-4 signaling where GAGs inhibited pathway activity dependent on specific sulfate residues of GAGs (Hep, HS) (Khan et al. 2008). Furthermore, BMP-4 signaling was improved after GAG clearance in Hurler syndrome cells, which accumulate GAGs. In contrast, CS chains of cell surface PGs showed a positive effect on BMP-4-induced osteoblast differentiation (Ye et al. 2012) and were crucial for BMP-7 mediated signaling (Irie et al. 2003), suggesting that GAGs enhance the biological activity of BMPs by presenting the ligands to their signaling receptors expressed on cell membranes.

A direct link between BMP signaling and GAGs can also be formed via CD44. This HA receptor was shown to augment BMP-4/7 effects both in vivo and in vitro and a loss in activity after hyaluronidase treatment (Luo et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2018). Besides the interaction of the GAG with the BMP ligand and subsequent receptor engagement, an intracellular mechanism was also proposed. It was shown that Smad1 could be anchored to the intracellular domain of CD44 for presentation to the type I BMP receptor (Peterson et al. 2004), thereby facilitating the formation of the active signaling complex. Given the fact that both CD44 and BMP expression correlate with poor prognosis in various cancers, a disruption in this interaction could pose an effective therapeutic target (Wu et al. 2018). Again, it is apparent, that GAGs are clearly involved BMP signaling. However, due to the complexity of this pathway, the GAGs and their local interaction both in steady state and disease need further elucidation.

Direct cellular effects of GAGs

Aside from interacting with various signaling molecules GAGs also confer direct effects on bone residing cells. Upon exposure, GAGs (HA, sHA) initially show a diffuse distribution in the cells cytoplasm while at later time points GAG containing vesicles can be observed in the perinuclear region of the exposed cells (Salbach-Hirsch et al. 2014; Veiseh et al. 2015). How different GAGs enter the cells has not been fully elucidated. Depending on their differentiation or activation status several HA receptors such as CD44, receptor for HA mediated motility (RHAMM), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor (LYVE-1), hyaluronic acid receptor for endocytosis (HARE), and toll-like receptor two and four can be present on osteoblasts, osteoclasts and osteocytes (Chang et al. 2007; Cyphert et al. 2015; Gupta et al. 2019; Hughes et al. 2009; Nakamura et al. 1995; Veiseh et al. 2015) and may also be engaged by other GAG types. Separating these cell autonomous effects is often difficult when GAG binding proteins are applied at the same time but may account for contrasting results in the literature.

The importance of GAGs for osteoblast differentiation was evaluated in several in vitro studies with partially contrasting results. Detailed comparative studies of differently formulated GAGs however unanimously conclude that high-sulfated GAGs increase the osteogenic potential of cells from the osteoblast lineage. They increase the expression Runx2, ALP, and OPN in pre-osteoblast cells, suggesting the potential to shift cells from proliferative to differentiate phenotypes (Hempel et al. 2014; Jackson et al. 2007). And indeed, collagen deposition, alkaline phosphatase activity and mineral accumulation of osteoblasts were shown to be enhanced in response to sGAG (sHA. CS, HS) treatment (Hempel et al. 2014; Jackson et al. 2007). In addition, CS PGs and sHAs where shown to regulate the process of collagen fibrillogenesis (Lin et al. 2020; Rother et al. 2015). This overall pro-osteogenic effect (see Figure 4, right) was also observed in osteocytes, where sulfated GAGs (sHA, CS) conferred anti-apoptotic effects and the expression of pro-osteogenic mediator profile (Tsourdi et al. 2013).

Direct effects of glycosaminoglycans on resident bone cells.

Sulfated GAGs confer an anti-osteoclastogenic (left) and pro osteogenic (right) mode of action when applied singularly and in soluble form. Cells from the osteogenic lineage such as osteoblasts and osteocytes show reduced proliferative actions but enhanced differentiation and matrix deposition. Hematopoietic stem cells show increased viability but are hampered in their differentiation to osteoclasts and subsequent bone resorption. Sulfated GAGs also confer immunomodulatory actions by promoting the transmission of inflammatory M1 macrophages activities to immunoregulatory M2 macrophages.

Similar evidence was obtained for their functional counterparts, the osteoclasts (Baud’huin et al. 2011). Several studies showed either a stimulation (Fuller et al. 1991; Irie et al. 2007) or inhibition (Ariyoshi et al. 2008; Ling et al. 2010b; Shinmyouzu et al. 2007) of osteoclastogenesis upon GAG (Hep, CS, sHA, HS, dermatan sulfate) treatment, often postulating an interaction with the RANKL/OPG axis as mode of action. Independent studies (Baud’huin et al. 2011; Salbach-Hirsch et al. 2013) showed that while GAGs (sHA, CS) do engage with the RANKL/OPG system, they also exert OPG-autonomous anti-osteoclastogenic effects (Salbach et al. 2012a). These effects were highly dependent on the GAGs sulfation degree and sugar backbone (Figure 4, left).

Bone cells also affect the whole organism as they are in constant, bi-directional cross talk with the immune system. This revelation even led to the establishment of a new interdisciplinary field: osteoimmunology. Since then many key players such as RANKL/OPG, interleukin-1, -8, -I7A, -23, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α have been described to direct effects both on bone and immune cells (Ponzetti and Rucci 2019). Also here GAGs confer modulatory roles. For example the actions of interleukin 8 (IL-8, CXCL8), which is a potent chemoattractant for polymorphonuclear leukocytes, are directly linked to sulfated GAG chains (CS, Hep, sHA) expressed on cell surfaces and within the extracellular matrix (Pichert et al. 2012). Bound to and presented by HSPGs IL-8 mediates the primary adhesion of cells to the endothelium and subsequent migration into the tissue. Hep and Hep containing hydrogels were shown to bind and effectively sequester IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and β (Lohmann et al. 2017). But also direct cellular effects are well described as e.g. HA and especially its low molecular weight fragments affect the function of antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages (Termeer et al. 2003). Contrary, synthetically sulfated sHA possesses immunomodulatory properties (Franz et al. 2013). Similarily pro- and anti-inflammatory effects were observed for CS (reviewed in Hatano and Watanabe, 2020) and Hep (Bruno et al. 2018; Mousavi et al. 2015) depending on its sulfation status.

These findings may translate into positive effects of sGAGs on bone remodeling as indicated in selected studies of GAG functionalized biomaterials, suggesting an essential role both in bone homeostasis and during bone healing. However, in vivo data is still very limited.

GAGs as therapeutic agents

Quantitative and qualitative changes in the tissues GAG profile have been recognized in many human pathologies such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis and aging and even linked to their severity (Simon and Shaughnessy 2004; Simonaro et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2018; Yoshioka et al. 2013). Among these, their implication in cancer progression are probably best studied, where changes both in PG core protein expression and GAG side chains have been noted (Johnson et al. 2005). As summarized above, GAG/protein interactions finetune many crucial signaling pathways. Hijacking this system enables cancer cells to differentially regulate extracellular signals e.g. by dynamically altering the structure of their proteoglycan coat (Johnson et al. 2005). While traditional strategies of either blocking receptor binding or neutralizing ligands are the main course of drug design, interfering in GAG actions in vivo could offer an alternative strategy. That the application of GAGs offers a wide range of therapeutic options has been shown for Hep (Johnson et al. 2005). To minimize side effects due to its anticoagulant and long-term pro-osteoporotic actions initial tests of synthetically designed GAGs or GAG mimetics have already yielded promising results. Other therapeutic intervention strategies include, but are not limited to, the engineering of inactive protein variants to engage the endogenous GAGs (Hep, HS) (Gschwandtner et al. 2015), or the preparation of non-GAG binding protein variants that compete with the wild type protein. This way, GAG actions could be specifically limited to target mediators. By restricting GAG actions or GAG-engaging protein actions to an even more local environment, biomaterials that act as mediator reservoir tailored for a controlled release (Panitz et al. 2016) or controlled inactivation of local mediators could be developed (Gronbach et al. 2020).

Conclusion

Steering or correcting bone remodeling processes is an important strategy to intervene in a wide range of bone diseases. These imbalances occur due to either dysfunctional bone formation or bone resorption. However, the underlying mechanism by which bone homeostasis is maintained is still not fully elucidated. Therefore, it is critical to understand the biological reactions that control bone homeostasis and may potentially facilitate bone modeling and healing. At present, the in vivo efficacy of endogenous factors such as BMPs and Wnts is limited, and new strategies to improve their effectiveness are urgently sought. From the current state of research it has become apparent that GAGs and PGs are potent co-stimulators of osteogenic signaling pathways, including the Wnt, RANKL/OPG and BMP pathway. Thus, the clinical application of GAG derivates as therapeutics or the targeted interference with GAG actions in bone poses an opportunity for novel osteoinductive therapies whose potential is still far from being exhausted.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: TRR67-B2 & TRR67-T1

Funding source: Technische Universität Dresden

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: Our work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant nos. TRR67-B2 & TRR67-T1) Transregio 67 (projects B2) to L.C.H. and C.H. J.S.-H. was supported by a MeDDrive and the women’s habilitation program of the medical faculty of the TU Dresden and also supported by Technische Universität Dresden. All Figures were created using the software from BioRender.com.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Ariyoshi, W., Takahashi, T., Kanno, T., Ichimiya, H., Shinmyouzu, K., Takano, H., Koseki, T., and Nishihara, T. (2008). Heparin inhibits osteoclastic differentiation and function. J. Cell Biol. 103: 1707–1717, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.21559.Search in Google Scholar

Baeg, G.H., Lin, X., Khare, N., Baumgartner, S., and Perrimon, N. (2001). Heparan sulfate proteoglycans are critical for the organization of the extracellular distribution of Wingless. Development 128: 87–94, https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.128.1.87.Search in Google Scholar

Baud’huin, M., Ruiz-Velasco, C., Jego, G., Charrier, C., Gasiunas, N., Gallagher, J., Maillasson, M., Naggi, A., Padrines, M., Redini, F., et al.. (2011). Glycosaminoglycans inhibit the adherence and the spreading of osteoclasts and their precursors: role in osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90: 49–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.08.001.Search in Google Scholar

Bertassoni, L.E. and Swain, M.V. (2014). The contribution of proteoglycans to the mechanical behavior of mineralized tissues. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 38: 91–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.06.008.Search in Google Scholar

Bonewald, L.F. (2011). The amazing osteocyte. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26: 229–238, https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.320.Search in Google Scholar

Boyden, L.M., Mao, J., Belsky, J., Mitzner, L., Farhi, A., Mitnick, M.A., Wu, D., Insogna, K., and Lifton, R.P. (2002). High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor–related protein 5. N. Engl. J. Med. 346: 1513–1521, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa013444.Search in Google Scholar

Bruno, V., Svensson-Arvelund, J., Rubér, M., Berg, G., Piccione, E., Jenmalm, M.C., and Ernerudh, J. (2018). Effects of low molecular weight heparin on the polarization and cytokine profile of macrophages and T helper cells in vitro. Sci. Rep. 8: 4166, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22418-2.Search in Google Scholar

Calvi, L.M., Adams, G.B., Weibrecht, K.W., Weber, J.M., Olson, D.P., Knight, M.C., Martin, R.P., Schipani, E., Divieti, P., Bringhurst, F.R., et al.. (2003). Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature 425: 841–846, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02040.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, E.J., Kim, H.J., Ha, J., Kim, H.J., Ryu, J., Park, K.H., Kim, U.H., Lee, Z.H., Kim, H.M., Fisher, D.E., et al.. (2007). Hyaluronan inhibits osteoclast differentiation via Toll-like receptor 4. J. Cell Sci. 120: 166–176, https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.03310.Search in Google Scholar

Claassen, H., Cellarius, C., Scholz-Ahrens, K.E., Schrezenmeir, J., Glüer, C.C., Schünke, M., and Kurz, B. (2006). Extracellular matrix changes in knee joint cartilage following bone-active drug treatment. Cell Tissue Res. 324: 279–289, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-005-0131-y.Search in Google Scholar

Cordeiro-Spinetti, E., Taichman, R.S., and Balduino, A. (2015). The bone marrow endosteal niche: how far from the surface? J. Cell. Biochem. 116: 6–11, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.24952.Search in Google Scholar

Crockett, J.C., Rogers, M.J., Coxon, F.P., Hocking, L.J., and Helfrich, M.H. (2011). Bone remodelling at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 124: 991–998, https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.063032.Search in Google Scholar

Cyphert, J.M., Trempus, C.S., and Garantziotis, S. (2015). Size matters: molecular weight specificity of hyaluronan effects in cell biology. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2015: 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/563818.Search in Google Scholar

Ferraro, F., Celso, C.L., and Scadden, D. (2010). Adult stem cels and their niches. In: Advances in experimental Medicine and biology, pp. 155–168, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7037-4_11.Search in Google Scholar

Franz, S., Allenstein, F., Kajahn, J., Forstreuter, I., Hintze, V., Möller, S., and Simon, J.C. (2013). Artificial extracellular matrices composed of collagen i and high-sulfated hyaluronan promote phenotypic and functional modulation of human pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages. Acta Biomater. 9: 5621–5629, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2012.11.016.Search in Google Scholar

Fuller, K., Chambers, T.J., and Gallagher, A.C. (1991). Heparin augments osteoclast resorption-stimulating activity in serum. J. Cell. Physiol. 147: 208–214, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.1041470204.Search in Google Scholar

Gandhi, N.S. and Mancera, R.L. (2008). The structure of glycosaminoglycans and their interactions with proteins. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 72: 455–482, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00741.x.Search in Google Scholar

Gong, Y., Slee, R.B., Fukai, N., Rawadi, G., Roman-Roman, S., Reginato, A.M., Wang, H., Cundy, T., Glorieux, F.H., Lev, D., et al.. (2001). LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell 107: 513–523, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00571-2.Search in Google Scholar

Gronbach, M., Mitrach, F., Möller, S., Rother, S., Friebe, S., Mayr, S.G., Schnabelrauch, M., Hintze, V., Hacker, M.C., and Schulz-Siegmund, M. (2020). A versatile macromer-based glycosaminoglycan (Sha3) decorated biomaterial for pro-osteogenic scavenging of Wnt antagonists. Pharmaceutics 12: 1–23, https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12111037.Search in Google Scholar

Grzesik, W.J., Frazier, C.R., Shapiro, J.R., Sponseller, P.D., Robey, P.G., and Fedarko, N.S. (2002). Age-related changes in human bone proteoglycan structure. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 43638–43647, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m202124200.Search in Google Scholar

Gschwandtner, M., Trinker, M.U., Hecher, B., Adage, T., Ali, S., and Kungl, A.J. (2015). Glycosaminoglycan silencing by engineered CXCL12 variants. FEBS Lett. 589: 2819–2824, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2015.07.052.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, X. and Wang, X.F. (2009). Signaling cross-talk between TGF-β/BMP and other pathways. Cell Res. 19: 71–88, https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2008.302.Search in Google Scholar

Gupta, R.C., Lall, R., Srivastava, A., and Sinha, A. (2019). Hyaluronic acid: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic trajectory. Front. Vet. Sci. 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00192.Search in Google Scholar

Hatano, S. and Watanabe, H. (2020). Regulation of macrophage and dendritic cell function by chondroitin sulfate in innate to antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Front. Immunol. 11: 232, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00232.Search in Google Scholar

Hempel, U., Preissler, C., Vogel, S., Möller, S., Hintze, V., Becher, J., Schnabelrauch, M., Rauner, M., Hofbauer, L.C., and Dieter, P. (2014). Artificial extracellular matrices with oversulfated glycosaminoglycan derivatives promote the differentiation of osteoblast-precursor cells and premature osteoblasts. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/938368.Search in Google Scholar

Hintze, V., Moeller, S., Schnabelrauch, M., Bierbaum, S., Viola, M., Worch, H., and Scharnweber, D. (2009). Modifications of hyaluronan influence the interaction with human bone morphogenetic protein-4 (hBMP-4). Biomacromolecules 10: 3290–3297, https://doi.org/10.1021/bm9008827.Search in Google Scholar

Hintze, V., Samsonov, S.A., Anselmi, M., Moeller, S., Becher, J., Schnabelrauch, M., Scharnweber, D., and Pisabarro, M.T. (2014). Sulfated glycosaminoglycans exploit the conformational plasticity of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and alter the interaction profile with its receptor. Biomacromolecules 15: 3083–3092, https://doi.org/10.1021/bm5006855.Search in Google Scholar

Hua, R., Ni, Q., Eliason, T.D., Han, Y., Gu, S., Nicolella, D.P., Wang, X., and Jiang, J.X. (2020). Biglycan and chondroitin sulfate play pivotal roles in bone toughness via retaining bound water in bone mineral matrix. Matrix Biol. 94: 95–109, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2020.09.002.Search in Google Scholar

Hughes, D.E., Salter, D.M., and Simpson, R. (2009). CD44 expression in human bone: a novel marker of osteocytic differentiation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 9: 39–44, https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.5650090106.Search in Google Scholar

Ikebuchi, Y., Aoki, S., Honma, M., Hayashi, M., Sugamori, Y., Khan, M., Kariya, Y., Kato, G., Tabata, Y., Penninger, J.M., et al.. (2018). Coupling of bone resorption and formation by RANKL reverse signalling. Nature 561: 195–200, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0482-7.Search in Google Scholar

Irie, A., Habuchi, H., Kimata, K., and Sanai, Y. (2003). Heparan sulfate is required for bone morphogenetic protein-7 signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 308: 858–865, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01500-6.Search in Google Scholar

Irie, A., Takami, M., Kubo, H., Sekino-Suzuki, N., Kasahara, K., and Sanai, Y. (2007). Heparin enhances osteoclastic bone resorption by inhibiting osteoprotegerin activity. Bone 41: 165–174, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.190.Search in Google Scholar

Jackson, R.A., Murali, S., van Wijnen, A.J., Stein, G.S., Nurcombe, V., and Cool, S.M. (2007). Heparan sulfate regulates the anabolic activity of MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells by induction of Runx2. J. Cell. Physiol. 210: 38–50, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.20813.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, Z., Proudfoot, A.E., and Handel, T.M. (2005). Interaction of chemokines and glycosaminoglycans: a new twist in the regulation of chemokine function with opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16: 625–636, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.04.006.Search in Google Scholar

Khan, S.A., Nelson, M.S., Pan, C., Gaffney, P.M., and Gupta, P. (2008). Endogenous heparan sulfate and heparin modulate bone morphogenetic protein-4 signaling and activity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294: 1387–1397, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00346.2007.Search in Google Scholar

Kiel, M.J., Yilmaz, Ö.H., Iwashita, T., Yilmaz, O.H., Terhorst, C., and Morrison, S.J. (2005). SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell 121: 1109–1121, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026.Search in Google Scholar

Koehler, L., Ruiz-Gómez, G., Balamurugan, K., Rother, S., Freyse, J., Möller, S., Schnabelrauch, M., Köhling, S., Djordjevic, S., Scharnweber, D., et al.. (2019). Dual action of sulfated hyaluronan on angiogenic processes in relation to vascular endothelial growth factor-A. Sci. Rep. 9: 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54211-0.Search in Google Scholar

Koehler, L., Samsonov, S., Rother, S., Vogel, S., Köhling, S., Moeller, S., Schnabelrauch, M., Rademann, J., Hempel, U., Pisabarro, M.T., et al.. (2017). Sulfated hyaluronan derivatives modulate TGF-β1:receptor complex formation: possible consequences for TGF-β1 signaling. Sci. Rep. 7: 1210, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01264-8.Search in Google Scholar

Lademann, F., Hofbauer, L.C., and Rauner, M. (2020). The bone morphogenetic protein pathway: the osteoclastic perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.586031.Search in Google Scholar

Lau, B.E.K., Allen, S., Hsu, A.R., and Handel, T.M. (2004). Chemokine-receptor interactions: GPCRs, glycosaminoglycans and viral chemokine binding proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 68: 351–391, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-3233(04)68010-7.Search in Google Scholar

Le, P.M., Andreeff, M., and Battula, V.L. (2018). Osteogenic niche in the regulation of normal hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Haematologica 103: 1945–1955, https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2018.197004.Search in Google Scholar

Lévesque, J.-P., Helwani, F.M., and Winkler, I.G. (2010). The endosteal ‘osteoblastic’ niche and its role in hematopoietic stem cell homing and mobilization. Leukemia 24: 1979–1992, https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2010.214.Search in Google Scholar

Li, M., Yang, S., and Xu, D. (2016). Heparan sulfate regulates the structure and function of osteoprotegerin in osteoclastogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 291: 24160–24171, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m116.751974.Search in Google Scholar

Lin, X., Patil, S., Gao, Y.-G., and Qian, A. (2020). The bone extracellular matrix in bone formation and regeneration. Front. Pharmacol. 11: 1–15, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00757.Search in Google Scholar

Lin, X. and Perrimon, N. (1999). Dally cooperates with Drosophila Frizzled 2 to transduce Wingless signalling. Nature 400: 281–284, https://doi.org/10.1038/22343.Search in Google Scholar

Ling, L., Dombrowski, C., Foong, K.M., Haupt, L.M., Stein, G.S., Nurcombe, V., van Wijnen, A.J., and Cool, S.M. (2010a). Synergism between Wnt3a and heparin enhances osteogenesis via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt/RUNX2 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 26233–26244, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m110.122069.Search in Google Scholar

Ling, L., Murali, S., Stein, G.S., van Wijnen, A.J., and Cool, S.M. (2010b). Glycosaminoglycans modulate RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. J. Cell. Biochem. 109: 1222–1231.10.1002/jcb.22506Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lohmann, N., Schirmer, L., Atallah, P., Wandel, E., Ferrer, R.A., Werner, C., Simon, J.C., Franz, S., and Freudenberg, U. (2017). Glycosaminoglycan-based hydrogels capture inflammatory chemokines and rescue defective wound healing in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 9: eaai9044, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aai9044.Search in Google Scholar

Luo, N., Knudson, W., Askew, E.B., Veluci, R., and Knudson, C.B. (2014). CD44 and hyaluronan promote the bone morphogenetic protein 7 signaling response in murine chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 66: 1547–1558, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.38388.Search in Google Scholar

Malinauskas, T. and Jones, E.Y. (2014). Extracellular modulators of Wnt signalling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 29: 77–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2014.10.003.Search in Google Scholar

Mania, V.M., Kallivokas, A.G., Malavaki, C., Asimakopoulou, A.P., Kanakis, J., Theocharis, A.D., Klironomos, G., Gatzounis, G., Mouzaki, A., Panagiotopoulos, E., et al.. (2009). A comparative biochemical analysis of glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans in human orthotopic and heterotopic bone. IUBMB Life 61: 447–452, https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.167.Search in Google Scholar

Mansouri, R., Jouan, Y., Hay, E., Blin-Wakkach, C., Frain, M., Ostertag, A., Le Henaff, C., Marty, C., Geoffroy, V., Marie, P.J., et al.. (2017). Osteoblastic heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans control bone remodeling by regulating Wnt signaling and the crosstalk between bone surface and marrow cells. Cell Death Dis. 8: e2902, https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2017.287.Search in Google Scholar

Miguez, P.A., Terajima, M., Nagaoka, H., Mochida, Y., and Yamauchi, M. (2011). Role of glycosaminoglycans of biglycan in BMP-2 signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 405: 262–266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.022.Search in Google Scholar

Mousavi, S., Moradi, M., Khorshidahmad, T., and Motamedi, M. (2015). Anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and its derivatives: a systematic review. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015: 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/507151.Search in Google Scholar

Murphy, J.W., Cho, Y., Sachpatzidis, A., Fan, C., Hodsdon, M.E., and Lolis, E. (2007). Structural and functional basis of CXCL12 (stromal cell-derived factor-1α) binding to heparin. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 10018–10027, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m608796200.Search in Google Scholar

Nadanaka, S., Kinouchi, H., Taniguchi-Morita, K., Tamura, J., and Kitagawa, H. (2011). Down-regulation of chondroitin 4-O-sulfotransferase-1 by Wnt signaling triggers diffusion of Wnt-3a. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 4199–4208, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m110.155093.Search in Google Scholar

Nakamura, H., Kenmotsu, S., Sakai, H., and Ozawa, H. (1995). Localization of CD44, the hyaluronate receptor, on the plasma membrane of osteocytes and osteoclasts in rat tibiae. Cell Tissue Res. 280: 225–233, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00307793.Search in Google Scholar

Nozawa, S., Inubushi, T., Irie, F., Takigami, I., Matsumoto, K., Shimizu, K., Akiyama, H., and Yamaguchi, Y. (2018). Osteoblastic heparan sulfate regulates osteoprotegerin function and bone mass. JCI Insight 3, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.89624.Search in Google Scholar

Panitz, N., Theisgen, S., Samsonov, S.A., Gehrcke, J.P., Baumann, L., Bellmann-Sickert, K., Köhling, S., Teresa Pisabarro, M., Rademann, J., Huster, D., et al.. (2016). The structural investigation of glycosaminoglycan binding to CXCL12 displays distinct interaction sites. Glycobiology 26: 1209–1221, https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cww059.Search in Google Scholar

Peterson, R.S., Andhare, R.A., Rousche, K.T., Knudson, W., Wang, W., Grossfield, J.B., Thomas, R.O., Hollingsworth, R.E., and Knudson, C.B. (2004). CD44 modulates Smad1 activation in the BMP-7 signaling pathway. J. Cell Biol. 166: 1081–1091, https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200402138.Search in Google Scholar

Pichert, A., Schlorke, D., Franz, S., and Arnhold, J. (2012). Functional aspects of the interaction between interleukin-8 and sulfated glycosaminoglycans. Biomatter 2: 142–148, https://doi.org/10.4161/biom.21316.Search in Google Scholar

Ponzetti, M. and Rucci, N. (2019). Updates on osteoimmunology: what’s new on the cross-talk between bone and immune system. Front. Endocrinol. 10: 236, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00236.Search in Google Scholar

Purton, L.E. and Scadden, D.T. (2008). The hematopoietic stem cell niche. In: StemBook [Internet]. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Stem Cell Institute, Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27051/. doi: 10.3824/stembook.1.28.1.10.3824/stembook.1.28.1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Rider, C.C. and Mulloy, B. (2017). Heparin, heparan sulphate and the TGF-β cytokine superfamily. Molecules 22: 1–11, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22050713.Search in Google Scholar

Ross, F.P. and Christiano, A.M. (2006). Nothing but skin and bone. J. Clin. Invest. 116: 1140–1149, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci28605.Search in Google Scholar

Rother, S., Salbach-Hirsch, J., Moeller, S., Seemann, T., Schnabelrauch, M., Hofbauer, L.C.L.C., Hintze, V., and Scharnweber, D. (2015). Bioinspired collagen/glycosaminoglycan-based cellular microenvironments for tuning osteoclastogenesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7: 23787–23797, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b08419.Search in Google Scholar

Rucci, N. (2008). Molecular biology of bone remodelling. Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. 5: 49–56.Search in Google Scholar

Salbach-Hirsch, J., Kraemer, J., Rauner, M., Samsonov, S.A., Pisabarro, M.T., Moeller, S., Schnabelrauch, M., Scharnweber, D., Hofbauer, L.C., and Hintze, V. (2013). The promotion of osteoclastogenesis by sulfated hyaluronan through interference with osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand/osteoprotegerin complex formation. Biomaterials 34: 7653–7661, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.053.Search in Google Scholar

Salbach-Hirsch, J., Samsonov, S.A.S.A., Hintze, V., Hofbauer, C., Picke, A.K.A.K., Rauner, M., Gehrcke, J.P.J.P., Moeller, S., Schnabelrauch, M., Scharnweber, D., et al.. (2015). Structural and functional insights into sclerostin-glycosaminoglycan interactions in bone. Biomaterials 67: 335–345, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.07.021.Search in Google Scholar

Salbach-Hirsch, J., Ziegler, N., Thiele, S., Moeller, S., Schnabelrauch, M., Hintze, V., Scharnweber, D., Rauner, M., and Hofbauer, L.C. (2014). Sulfated glycosaminoglycans support osteoblast functions and concurrently suppress osteoclasts. J. Cell. Biochem. 115: 1101–1111, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.24750.Search in Google Scholar

Salbach, J., Kliemt, S., Rauner, M., Rachner, T.D., Goettsch, C., Kalkhof, S., von Bergen, M., Möller, S., Schnabelrauch, M., Hintze, V., et al.. (2012a). The effect of the degree of sulfation of glycosaminoglycans on osteoclast function and signaling pathways. Biomaterials 33: 8418–8429, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.028.Search in Google Scholar

Salbach, J., Rachner, T.D., Rauner, M., Hempel, U., Anderegg, U., Franz, S., Simon, J.C., and Hofbauer, L.C. (2012b). Regenerative potential of glycosaminoglycans for skin and bone. J. Mol. Med. 90: 625–635, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-011-0843-2.Search in Google Scholar

Schofield, R. (1978). The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cell 4: 7–25.Search in Google Scholar

Shahnazari, M., Chu, V., Wronski, T.J., Nissenson, R.A., and Halloran, B.P. (2013). CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling in the osteoblast regulates the mesenchymal stem cell and osteoclast lineage populations. FASEB J. 27: 3505–3513, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.12-225763.Search in Google Scholar

Shinmyouzu, K., Takahashi, T., Ariyoshi, W., Ichimiya, H., Kanzaki, S., and Nishihara, T. (2007). Dermatan sulfate inhibits osteoclast formation by binding to receptor activator of NF-κB ligand. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354: 447–452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.221.Search in Google Scholar

Simon, R.R. and Shaughnessy, S.G. (2004). Effects of anticoagulants on bone. Clin. Rev. Bone Miner. Metabol. 2: 151–158, https://doi.org/10.1385/bmm:2:2:151.10.1385/BMM:2:2:151Search in Google Scholar

Simonaro, C.M., D’Angelo, M., He, X., Eliyahu, E., Shtraizent, N., Haskins, M.E., and Schuchman, E.H. (2008). Mechanism of glycosaminoglycan-mediated bone and joint disease: implications for the mucopolysaccharidoses and other connective tissue diseases. Am. J. Pathol. 172: 112–122, https://doi.org/10.2353/ajpath.2008.070564.Search in Google Scholar

Sugiyama, T., Kohara, H., Noda, M., and Nagasawa, T. (2006). Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity 25: 977–988, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016.Search in Google Scholar

Termeer, C., Sleeman, J.P., and Simon, J.C. (2003). Hyaluronan – magic glue for the regulation of the immune response? Trends Immunol. 24: 112–114, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00029-2.Search in Google Scholar

Théoleyre, S., Kwan Tat, S., Vusio, P., Blanchard, F., Gallagher, J., Ricard-Blum, S., Fortun, Y., Padrines, M., Rédini, F., and Heymann, D. (2006). Characterization of osteoprotegerin binding to glycosaminoglycans by surface plasmon resonance: role in the interactions with receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL) and RANK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347: 460–467, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.120.Search in Google Scholar

Trentin, J.J. (1971). Determination of bone marrow stem cell differentiation by stromal hemopoietic inductive microenvironments (HIM). Am. J. Pathol. 65: 621–628.Search in Google Scholar

Tsourdi, E., Hintze, V., Scharnweber, D., Möller, S., Schnabelrauch, M., Salbach-Hirsch, J., Tsourdi, E., Hintze, V., Scharnweber, D., Möller, S., et al.. (2013). Glycosaminoglycan sulfation of artificial extracellular matrix coatings enhances regenerative potential of bone cells. Eur. Cell. Mater. 26: 73.Search in Google Scholar

Tsuda, M., Kamimura, K., Nakato, H., Archer, M., Staatz, W., Fox, B., Humphrey, M., Olson, S., Futch, T., Kaluza, V., et al.. (1999). The cell-surface proteoglycan Dally regulates Wingless signalling in Drosophila. Nature 400: 276–280, https://doi.org/10.1038/22336.Search in Google Scholar

Van Wesenbeeck, L., Cleiren, E., Gram, J., Beals, R.K., Bénichou, O., Scopelliti, D., Key, L., Renton, T., Bartels, C., Gong, Y., et al.. (2003). Six novel missense mutations in the LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) gene in different conditions with an increased bone density. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72: 763–771, https://doi.org/10.1086/368277.Search in Google Scholar

Veiseh, M., Leith, S.J., Tolg, C., Elhayek, S.S., Bahrami, S.B., Collis, L., Hamilton, S., McCarthy, J.B., Bissell, M.J., and Turley, E. (2015). Uncovering the dual role of RHAMM as an HA receptor and a regulator of CD44 expression in RHAMM-expressing mesenchymal progenitor cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 3, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2015.00063.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, X., Hua, R., Ahsan, A., Ni, Q., Huang, Y., Gu, S., and Jiang, J.X. (2018). Age-related deterioration of bone toughness is related to diminishing amount of matrix glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). JBMR Plus 2: 164–173, https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10030.Search in Google Scholar

Westendorf, J.J., Kahler, R.A., and Schroeder, T.M. (2004). Wnt signaling in osteoblasts and bone diseases. Gene 341: 19–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.044.Search in Google Scholar

Wolf, N.S. and Trentin, J.J. (1968). Hemopoietic colony studies. V. Effect of hemopoietic organ stroma on differentiation of pluripotent stem cells. J. Exp. Med. 127: 205–214, https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.127.1.205.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, R.L., Sedlmeier, G., Kyjacova, L., Schmaus, A., Philipp, J., Thiele, W., Garvalov, B.K., and Sleeman, J.P. (2018). Hyaluronic acid-CD44 interactions promote BMP4/7-dependent Id1/3 expression in melanoma cells. Sci. Rep. 8: 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33337-7.Search in Google Scholar

Yan, D. and Lin, X. (2009). Shaping morphogen gradients by proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1: a002493, https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a002493.Search in Google Scholar

Ye, Y., Hu, W., Guo, F., Zhang, W., Wang, J., and Chen, A. (2012). Glycosaminoglycan chains of biglycan promote bone morphogenetic protein-4-induced osteoblast differentiation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 30: 1075–1080, https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2012.1091.Search in Google Scholar

Yoshioka, Y., Kozawa, E., Urakawa, H., Arai, E., Futamura, N., Zhuo, L., Kimata, K., Ishiguro, N., and Nishida, Y. (2013). Suppression of hyaluronan synthesis alleviates inflammatory responses in murine arthritis and in human rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 65: 1160–1170, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.37861.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, J., Niu, C., Ye, L., Huang, H., He, X., Tong, W.G., Ross, J., Haug, J., Johnson, T., Feng, J.Q., et al.. (2003). Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature 425: 836–841, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02041.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Juliane Salbach-Hirsch et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Extracellular Matrix Engineering for Advanced Therapies

- 12 years more than just skin and bones: the CRC Transregio 67

- Improvement of wound healing by the development of ECM-inspired biomaterial coatings and controlled protein release

- Modulation of macrophage functions by ECM-inspired wound dressings – a promising therapeutic approach for chronic wounds

- Fibrillar biopolymer-based scaffolds to study macrophage-fibroblast crosstalk in wound repair

- Collagen/glycosaminoglycan-based matrices for controlling skin cell responses

- Investigation of the structure of regulatory proteins interacting with glycosaminoglycans by combining NMR spectroscopy and molecular modeling – the beginning of a wonderful friendship

- Biodegradable macromers for implant bulk and surface engineering

- Insights into structure, affinity, specificity, and function of GAG-protein interactions through the chemoenzymatic preparation of defined sulfated oligohyaluronans

- Chemically modified glycosaminoglycan derivatives as building blocks for biomaterial coatings and hydrogels

- Men who stare at bone: multimodal monitoring of bone healing

- New insights into the role of glycosaminoglycans in the endosteal bone microenvironment

- Identification of intracellular glycosaminoglycan-interacting proteins by affinity purification mass spectrometry

- Structural insights into the modulation of PDGF/PDGFR-β complexation by hyaluronan derivatives

- Tuning the network charge of biohybrid hydrogel matrices to modulate the release of SDF-1

- Impact of binding mode of low-sulfated hyaluronan to 3D collagen matrices on its osteoinductive effect for human bone marrow stromal cells

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Extracellular Matrix Engineering for Advanced Therapies

- 12 years more than just skin and bones: the CRC Transregio 67

- Improvement of wound healing by the development of ECM-inspired biomaterial coatings and controlled protein release

- Modulation of macrophage functions by ECM-inspired wound dressings – a promising therapeutic approach for chronic wounds

- Fibrillar biopolymer-based scaffolds to study macrophage-fibroblast crosstalk in wound repair

- Collagen/glycosaminoglycan-based matrices for controlling skin cell responses

- Investigation of the structure of regulatory proteins interacting with glycosaminoglycans by combining NMR spectroscopy and molecular modeling – the beginning of a wonderful friendship

- Biodegradable macromers for implant bulk and surface engineering

- Insights into structure, affinity, specificity, and function of GAG-protein interactions through the chemoenzymatic preparation of defined sulfated oligohyaluronans

- Chemically modified glycosaminoglycan derivatives as building blocks for biomaterial coatings and hydrogels

- Men who stare at bone: multimodal monitoring of bone healing

- New insights into the role of glycosaminoglycans in the endosteal bone microenvironment

- Identification of intracellular glycosaminoglycan-interacting proteins by affinity purification mass spectrometry

- Structural insights into the modulation of PDGF/PDGFR-β complexation by hyaluronan derivatives

- Tuning the network charge of biohybrid hydrogel matrices to modulate the release of SDF-1

- Impact of binding mode of low-sulfated hyaluronan to 3D collagen matrices on its osteoinductive effect for human bone marrow stromal cells