Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the impact of early clinical exposure courses and a preclinical tutorial guide on the academic performance of undergraduate dental students.

Methods

The early clinical exposure curriculum was carried out at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Affiliated Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital. A total of 364 students participated in this study. Seventy six clinicians from different sub-specialties volunteered as tutors. Two detailed questionnaires were administered separately to investigate the students’ and tutors’ opinions on the project. The results from students were gathered and further compared between the experimental group (n=253) who went through the curriculum and the control group (n=111) who did not. The tutors were asked to evaluate the students’ performance based on their observations.

Results

The results can be classified into two key categories: the evaluation of teaching outcomes and the appraisal of course arrangements. While students in the experimental group acknowledged and applauded the curriculum, all students in the control group showed a willingness to participate in the course. The tutors affirmed the effectiveness of the course and the students’ progress.

Conclusions

The combination of early clinical exposure and a preclinical tutorial system may extend conventional courses. The feedback provided in this study demonstrates the effectiveness of the curriculum, and some improvements are expected.

Introduction

The early years of the undergraduate phase are crucial for forming a thorough understanding of a doctor’s mission, which includes developing professional competency, medical ethics, and essential skills [1]. The traditional and most accepted training mode at stomatology colleges in China is mainly composed of theoretical courses for the first three or four years, followed by clinical internships. While clinical skills are prioritized at esteemed institutions, including Peking Union Medical College [2], challenges emerge during the transition from student to physician. This segmented approach can result in issues such as inexperience, shyness, and a lack of empathy, impacting both students and their mentors. Furthermore, as reported in the medical literature, up to 33.8 % of medical students experience anxiety, with dental students exhibiting even higher rates of depression, anxiety, and chronic stress during the shift from preclinical to clinical practice. This underscores the urgent need for educational institutions to prioritize and address students’ mental health [3, 4].

In recent years, the preparation of oral health medical students for complex work has become a pressing concern for both students and medical schools. Early exposure to clinical environments, alongside theoretical instruction, has emerged as a promising solution. Increasing evidence indicates that early clinical exposure positively affects students’ professional development and fosters their ability to integrate fundamental knowledge with clinical practice [5, 6]. For instance, a systematic review found that early clinical exposure prepares students for patient interactions and clinical responsibilities [7]. Students who have undergone early clinical experience seem to feel less stressed, more confident, and more motivated internally [3]. Hence, many colleges worldwide have designed and implemented early clinical experience courses aimed at enhancing teaching efficiency, promoting individual competencies, and facilitating the preclinic-clinic transition. Preclinical courses introduced in existing researches includes “clinical observation,” “site visits,” “case-based learning,” “interdisciplinary group activities,” “simulated multidisciplinary teams,” and so on 8], [9], [10. Furthermore, a tutorial system for undergraduates has been adopted to familiarize students with the role of physicians by providing a simulation environment and individualized tutor instructions [11, 12]. Therefore, in furtherance of preclinic-to-clinic transition, early clinic contact has been extensively implemented simultaneously with the preclinical tutorial system [13].

Analogously, divergent courses have been conducted at medical colleges in China and demonstrating advantages over conventional curricula in prompting students’ mastery of professional knowledge, communication capabilities, and clinical skills [14]. However, many of these courses are relatively temporary, typically lasting no longer than a year, and students are not entitled to shift their selection of instructors. Building on previous courses, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, launched a curriculum titled “Patients and Physicians” since the class of 2016 to bridge the gap between theoretical learning and clinical practice. The curriculum has proposed the concept of “all-around students,” aiming at developing well-rounded individuals with adept clinical inquiry ability, operation skills, competency to maintain a doctor-patient relationship, emotional management capacity, humanistic caring spirit, research ability, and holistic thinking.

In this study, we evaluated the impact of the curriculum by collecting and comparing students’ perspectives on the course.

Materials and methods

Setting and participants

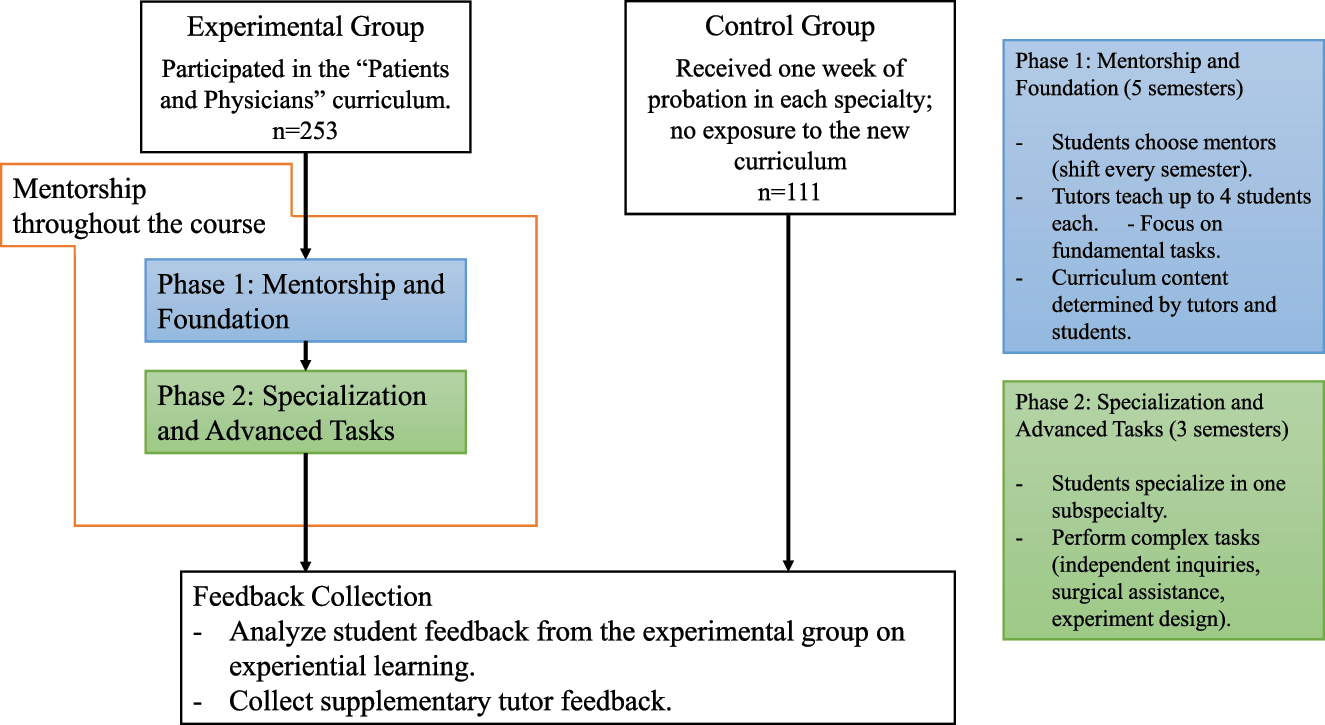

The curriculum “Patients and Physicians” begins in the second grade of the undergraduate and ends in the fifth grade. The eight-semester curriculum is divided into two stages. Section one continues for five semesters, during which students may choose a mentor and shift their choices every semester. Correspondently, each tutor may teach up to four students to ensure personalized attention. The most fundamental tasks should be performed during this stage. The curriculum contents are determined collaboratively by the tutors and students. Students may specialize in one specific subspecialty in section two, which continues for three semesters, where they engage in more complex and demanding tasks. Complicated tasks, such as independently completing inquiries, working as a surgical assistant, and designing experiments, will be performed. This research incorporates a comprehensive “Patients and Physicians” curriculum that emphasizes experiential learning through real patient interactions, simulated environments, and individualized mentorship.

A total of 364 dental students were recruited from the class of 2013 to the class of 2021. The experimental group, in which the curriculum was implemented, contained 253 students from both the five-year and eight-year oral medicine programs (international students encompassed). The control group, in which the curriculum was not implemented, comprised 111 participants from both five-year and seven-year educational systems (international students encompassed). The students in the control group underwent only one week of probation for each specialty during summer vacation before the internship. The curriculum was circumstantiated to them before the release of the questionnaire (Figure 1).

The study design and the course arrangement of “Patients and Physicians”.

In this retrospective study, student feedback was the primary focus, supplemented by insights from tutors. A total of 76 tutors participated in the study. All tutors work as clinicians at Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital. They volunteered to join the curriculum and provided guidance to younger students.

Data collection

Two separate questionnaires were designed and released to capture the opinions of students and tutors (Tables 1 and 2). Students in the control group were required to evaluate the teaching outcomes based on the conventional preclinical courses they had taken, and they were not asked to appraise the course arrangement considering their inexperience.

Questionnaire items for students.

| No. | Items |

|---|---|

| 1. | Participation in the curriculum (duration, departments, etc.) |

| 2. | Understanding of the intention, requirements, and evaluation system of the curriculum |

| 3. | Anticipated class hours |

| 4. | Activities carried out during the curriculum |

| 5. | Enthusiasm for attending the curriculum |

| 6. | Difficulties experienced during the internship |

| 7. | Evaluation of the teaching outcomes (elevation in confidence, clinical skills, communication capability, etc.) |

| 8. | Opinions on starting early clinical exposure before the launch of professional courses |

| 9. | Appraisal of curriculum arrangement (teaching both offline and online, extra courses on cultivating academic research ability, etc.) |

| 10. | Differences compared with conventional preclinical courses |

| 11. | The tendency to choose a specialty (students in the control group respond according to their situations before the internship) |

| 12. | Prefer focusing on a specific specialty or having extensive contacts with divergent specialties |

| 13. | Appraisal of the mentors |

| 14. | Suggestions for improvements |

-

Students in the control group ought to respond based on their experience of conventional preclinical courses and understanding of the curriculum “Patients and Physicians.”

Questionnaire items for tutors.

| No. | Items |

|---|---|

| 1. | Which hospital department do you belong to? |

| 2. | Based on your experience as a tutor for the curriculum “Patients and Physicians,” in which areas do you think students have fallen short? |

| 3. | During the teaching process, which parts do you lay emphasis upon? |

| 4. | What teaching methods are you inclined to utilize? |

| 5. | In which ways do you think students have advanced after the course? |

| 6. | Do you believe this course can help undergraduates choose their ideal specialties in the process of career planning? |

| 7. | Have you encountered any of the following difficulties in the teaching process? |

| 8. | Would you like to offer any advice for students’ future studies? |

| 9. | Do you have any other suggestions for this course? |

-

Tutors were required to answer 10 questions concerning the performance of the students and the arrangement of the course.

Ethical considerations

This study has gained approval from Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Ethics Committee. The approval number is SH9H-2024-T75-1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 25). The χ2 tests and Fisher’s exact tests were conducted to scrutinize subgroup analysis. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 336 questionnaires were collected from the students: 230 from the experimental group and 106 from the control group, yielding response rate of 90.9 % and 95.50 %, respectively. A total of 220 female and 116 male students completed the questionnaires. Additionally, 76 tutors, who participated in the preclinical contact curriculum, from 13 sub-specialties responded to the questionnaire. The results indicated that students in the experimental group gained sufficient knowledge of the intention, requirements, and evaluation methodology of the curriculum, whereas those in the control group remained unfamiliar with the course.

Evaluation of the teaching outcomes

The statistical analysis highlights significant differences in students’ attitudes towards whether the curriculum can “spark enthusiasm for learning stomatology,” “boost enthusiasm for clinical work,” and “lay emphasis on humanistic care consciousness” (p<0.05). While both groups recognized the unique features of the “Patients and Physicians” curriculum compared to other clinical courses, no statistical significance was revealed regarding the effect of starting clinical contact courses before the launch of specialized professional studies (Table 3). In the experimental group, a substantial 71.9 % of students identified their ideal developmental direction after learning in two or three departments (Table 4). Aside from group, gender has also been considered a potential factor. Statistical significance has been observed in terms of “assisting in integrating theory with practice” concerning gender (χ2=3.92, p=0.043).

Analysis of students’ perspectives on individual items.

| Items | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Group | Gendera | |

| Sparking enthusiasm for learning stomatology | 0.020 | NS |

| Establishing a perceptual understanding of clinical work | NS | NS |

| Understanding oral medicine in depth | NS | NS |

| Boosting positivity for scientific research | NS | NS |

| Boosting enthusiasm for clinical work | 0.040 | NS |

| Emphasizing humanistic care consciousness | 0.000 | NS |

| Improving learning motivation | NS | NS |

| Learning skills in communication and emotion management | NS | NS |

| Enhancing self-confidence | NS | NS |

| Assisting in comprehending professional knowledge | NS | NS |

| Stimulating passion for learning professional classes | NS | NS |

| Getting familiar with the future working environment | NS | NS |

| Assisting in integrating theory with practice | NS | 0.043 |

| Balancing between clinical work and academic research | NS | NS |

-

Gendera: Statistical results were calculated by comparing the replies from female and male students in the experimental group. “NS” means no statistically significant difference (p≥0.05).

Statistical analysis of students’ perspectives of the curriculum arrangement.

| Items | Percentage of students who affirmed the items | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Gendera | ||

| Being able to determine ideal developing direction after learning | 71.7 % | NS |

| ≥6 classes per semester | 69.1 % | NS |

| The requirement of accomplishing an essay | ||

| Of great importance to releasing papers | 34.3 % | NS |

| Learning skills to write papers | 53.9 % | NS |

| Adequate instruction from mentors | 89.6 % | NS |

| The teaching method of learning both online and offline | ||

| Saving time and improving efficiency | 53.0 % | NS |

| Reinforcing learning outcomes | 55.2 % | NS |

| Treasuring getting guided online | 43.3 % | NS |

| The arrangement of courses focusing on academic training | ||

| Playing a significant part in academic training | 27.8 % | NS |

| Contributing to training of academic research capabilities | 60.9 % | NS |

| Mastering fundamental research methods | 51.3 % | 0.005 |

| Getting exposed to the frontier areas | 44.8 % | 0.000 |

-

Statistical results were calculated by dividing the number of students who held positive attitudes towards the curriculum by the total number of students in the experimental group. Gendera: Statistical results were calculated by comparing the replies from female and male students in the experimental group.

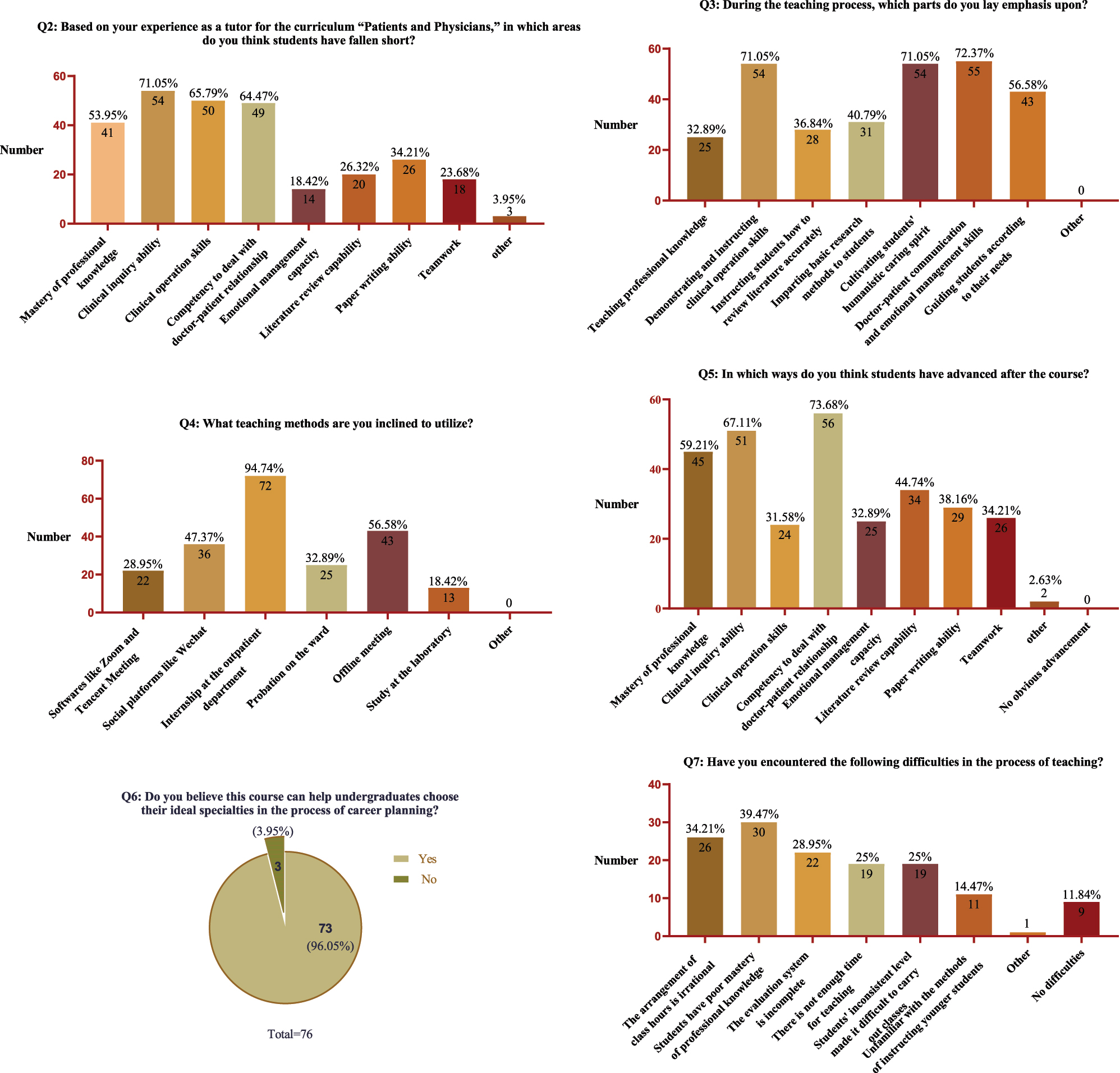

More than half of the investigated tutors observed that the students had fallen short of the following areas: mastery of professional knowledge (53.95 %), clinical inquiry ability (71.05 %), clinical operation skills (69.75 %), and competency in dealing with the doctor-patient relationship (64.47 %) (Figure 2). Tutors were inclined to place more emphasis on the demonstration and instruction of clinical operation skills (71.05 %), cultivating students’ humanistic caring spirit (71.05 %), and addressing doctor-patient communication and emotional management skills (72.37 %), and the majority of tutors chose to customize course contents based on students’ requests. Of the tutors, 96.05 % affirmed the curriculum’s role in helping undergraduates with career planning.

Results analysis of tutors’ responses to questions 2–7 (n=76).

Appraisal of the course arrangement

Questions concerning the rationality of the course arrangement were refined into three parts: students’ opinions on the requirement of finishing an easy course independently, the teaching modes of learning both online and offline, and academic training tasks. Only students in the experimental group responded to the relevant questions. They expressed generally positive views about several aspects of the curriculum, with over half supporting elements such as “learning techniques for writing papers” (53.9 %), “adequate instruction from mentors” (89.6 %), “saving time and improving efficiency” (53.0 %), “reinforcing learning outcomes” (55.2 %), “contributing to the training of academic research capability” (60.9 %), “mastering fundamental research methods” (51.3 %), and “≥6 classes per semester” (69.1 %) (Table 4). Notably, female students particularly recognized the positive effects of the curriculum on academic research capacity improvement (χ2=7.06, p=0.005) and exposure to frontier areas (χ2=12.14, p=0.000).

The difficulties mentioned most frequently by tutors were an irrational arrangement of class hours (34.21 %), poor mastery of professional knowledge (39.47 %), an incomplete evaluation system (28.95 %), inadequate teaching time (25.00 %), students’ inconsistent levels (25.00 %), and unfamiliarity with the methods of instructing younger students (14.47 %). The tutors’ suggestions were collected and displayed (Table 5).

Advices from tutors for students and the curriculum.

| No. | Advice |

|---|---|

| 1. | Goals and overall plans should be made at the beginning of each semester. |

| 2. | The course should begin from the first grade. |

| 3. | Students may set up a schedule and record their learning progress timely. |

| 4. | More emphasis ought to be laid on cultivation of research abilities. |

| 5. | For lower-grade students, it is important to cultivate their problem-solving ability and enhance their clinical thinking and scientific research abilities. |

| 6. | Students need to consolidate the foundation. |

| 7. | It is suggested to improve the syllabus, organize collective lesson preparation, define the content of the examination, and clarify curriculum training objectives. |

| 8. | Official accounts can be designed to display teaching contents and tutors’ introductions and encourage more teachers to participate in the course. |

| 9. | Students’ feedback should be collected at the end of each semester to reflect their real thoughts and advice for tutors. |

| 10. | Goals for trainee teachers are necessary. |

| 11. | To increase students’ exposure to clinical operations, students should be arranged to work as four-handed assistants. |

| 12. | Books ought to be updated to make them more flexible to use. |

-

Twelve out of 41 pieces of advice have been recorded. Repeated and similar pieces of advice have been deleted or gathered.

Discussion

According to the original arrangement at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, students do not accept clinical courses systematically or begin an internship until the second semester of the fourth grade, limiting early exposure to clinical practice. Opportunities for students to engage in clinical work prior to internships are mostly superficial and transient, consisting of brief observational courses at affiliated hospitals. The curriculum “Patients and Physicians” may provide undergraduates with opportunities to go into clinical operation skills, humanistic caring spirit, problem-based learning (PBL) curriculums, and so forth [15, 16]. The students in the experimental group acknowledged the curriculum for its ability to spark learning motivation, enhance confidence, improve their interest in work, and reinforce their professional knowledge. Based on our study, we achieved the teaching goal of facilitating the preclinic-to-clinic transition by arranging a systematic, comprehensive, and long-term curriculum.

Both students and tutors acknowledged that a solid theoretical foundation is critical for effective clinical practice. However, much like the tutors’ regret, some students entered the preclinical courses unprepared. Meanwhile, tutors would rather let students study professional knowledge on their own, than spend valuable class time on book learning. Fortunately, most students managed to identify problems and took the initiative to supplement their knowledge constantly during their participation in the clinical course. One significant implication of our results is the potential for this integrated approach to be applied across various medical education programs.

Recently, the occurrence of several severe “medically alarming” incidents have alerted doctors of the gravity of establishing a benign doctor-patient relationship. Young students require good communication and emotion management skills to deal with patients and provide self-protection [17]. The course aimed to develop communication skills, evolving from preliminary communication with patients to the adjustment of their own emotions and even patients’ emotions. Alvarez et al. revealed that participants spoke highly about communication-focused curricula because of their enhanced self-perception and self-awareness [18]. Students in the experimental group similarly reported enhanced communication skills, with tutors noting the curriculum’s significant contribution to maintaining doctor-patient relationships.

In addition to theoretical knowledge and clinical skills, innovation capability is gaining attention, especially at leading institutions. However, academic research demands comprehensive qualities and has been regarded as an arduous task by some undergraduates. According to the statistical results, most students believed that the curriculum would assist them in writing essays and understanding fundamental academic knowledge and basic methods. Female students were inclined to recognize the curriculum as cultivating their academic abilities. However, students did not think that this course can contribute to the upgradation of academic research abilities as much as it facilitates clinical skills and humanistic care consciousness. Consistently, over 80 % of the tutors did not implement preclinical courses in the laboratory due to time limitations, insufficient laboratory resources, and other reasons. Given the rigorous demands for research proficiency, schools should carry out more unified scientific research courses, instead of relying solely on courses conducted by tutors.

Students in China must choose their specialty before the completion of their internships, a requirement dictated by the timing of the postgraduate entrance examination. This often leads to confusion due to the limited exposure to various specialties. Therefore, adequate exposure to various sub-specialties is urgently required. Both groups’ feedback showed an inclination to try divergent sub-specialties before making a final decision. Moreover, the ability to evaluate the situation as a whole has been increasingly valued, as patients expect to receive comprehensive advice from clinicians. Accordingly, an arrangement allowing students to shift their choice of mentors was designed. The experience of being trained in various departments enables students to jump out of certain sub-specialties and think integrally. The study highlights the importance of mentorship in shaping the educational experiences of dental students. As demonstrated, individualized guidance can significantly impact learning outcomes. Most of the experimental group students and tutors admitted that the curriculum could help undergraduates choose their ideal specialty in the process of career planning. This model could be adapted in other disciplines within medical education, encouraging institutions to prioritize mentorship structures that facilitate one-on-one interactions between students and experienced clinicians.

The online courses widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic have become an important method of instruction both in the past and present. Online courses have been popularized domestically and internationally to supplement conventional teaching methods. In our study, the teaching methods of studying offline and online were supported by both groups. Online teaching implemented at a fragmented time may help students develop proficient time-utilization capabilities in the initial years of medical education. Although online teaching can reduce commute time and allow for repeated viewing, it cannot fully substitute for essential hands-on experiences like internships and lab work. Most tutors pointed out that the effectiveness of the preclinical course had been affected, even though online courses could supplement that experience at the outpatient department, and the ward could not be carried out. Fortunately, the order of teaching has been restored to normal, and this course will be conducted regularly in the future.

In this research, the curriculum incorporates reflective practices and feedback mechanisms that promote continuous improvement and self-awareness among students. This dual focus not only enhances clinical enthusiasm but also fosters resilience and empathy – key attributes for effective healthcare professionals. By employing these innovative strategies, the study aims to demonstrate how such an integrated approach can better prepare medical students for the complexities of clinical practice, ultimately contributing to their professional development in ways that traditional methods may not fully achieve.

Meanwhile, it is essential to address the aspects of the curriculum that did not yield statistically significant results. Several factors could contribute to this outcome.

Timing of exposure: students may need more time to assimilate clinical experiences before they can meaningfully apply them in specialized contexts. The lack of immediate relevance might dilute the perceived impact of early exposure.

Variability in student engagement: differences in student motivation and engagement levels may affect how they benefit from early clinical exposure. Those who are less engaged might not experience the intended advantages.

Differences in specialty requirements: certain specialties may demand more advanced skills and knowledge, rendering early exposure less impactful for students who later specialize in those areas.

Further in-depth analysis is necessary to explore these factors and their implications on curriculum design. Understanding these nuances will allow educators to better tailor programs to maximize student learning and professional development. Years are required before educational achievements can be observed. The presumption of a causal relationship between the curriculum and academic achievement based on students’ periodic grades or performances is irrational. Further improvements should be made to improve course arrangements and increase teaching efficiency. Methods such as virtual shadowing programs for dental students may be useful.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that early clinical exposure and preclinical guidance for dental students during the undergraduate phase reforms and improves traditional teaching methods, significantly stimulating students’ interest and motivation towards stomatology. As students were entitled to experience clinical work as participants rather than bystanders, their initiative to learn stomatology was significantly boosted. In the future, more efforts should be made to further optimize the course and address this shortage.

Funding source: The second batch of the Industry-University-Research Collaborative Education Project in 2021 of the Higher Education Department, Ministry of Education

Award Identifier / Grant number: number 202102457003

Funding source: 2021 Ideological and Political Education Research Fund of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of medicine

Award Identifier / Grant number: SZ-2021-12

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the students and mentors of this program from the College of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. We are grateful to Lin Li, Yun Sun, Weiyan Zhu, Jiawei Zheng, Chi Yang, and Guo Lian for their suggestions.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Research ethics: This study has gained approval from Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Ethics Committee. The approval number is SH9H-2024-T75-1.

-

Author contributions: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: No Artificial Intelligence (AI) and/or Machine Learning Tools were used in the research or article.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by 2021 Ideological and Political Education Research Fund of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of medicine (grant number SZ-2021-12); The second batch of the Industry-University-Research Collaborative Education Project in 2021 of the Higher Education Department, Ministry of Education (grant number 202102457003).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Littlewood, S, Ypinazar, V, Margolis, SA, Scherpbier, A, Spencer, J, Dornan, T. Early practical experience and the social responsiveness of clinical education: systematic review. BMJ 2005;331:387–91. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7513.387.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Liu, YN, Zhao, LJ, Su, J, Zhang, Y, Kang, JS, Guo, LR, et al.. Experimenting early exposure to clinical aspects for medical students. China Higher Med Educ 2017;10:85–6. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-1701.2017.10.043.Search in Google Scholar

3. Moore, R, Molsing, S, Meyer, N, Schepler, M. Early clinical experience and mentoring of Young dental students-A qualitative study. Dent J 2021;9:91. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9080091.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Collin, V, O’Selmo, E, Whitehead, P. Stress, psychological distress, burnout and perfectionism in UK dental students. Br Dent J 2020;229:605–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2281-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Spencer, AL, Brosenitsch, T, Levine, AS, Kanter, SL. Back to the basic sciences: an innovative approach to teaching senior medical students how best to integrate basic science and clinical medicine. Acad Med 2008;83:662–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318178356b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Goldie, J, Dowie, A, Cotton, P, Morrison, J. Teaching professionalism in the early years of a medical curriculum: a qualitative study. Med Educ 2007;41:610–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02772.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Ingale, MH, Tayade, MC, Bhamare, S. Early clinical exposure: dynamics, opportunities, and challenges in modern medical education. J Educ Health Promot 2023;12:295. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_237_23.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Tayade, MC, Latti, RG. Effectiveness of early clinical exposure in medical education: settings and scientific theories – review. J Educ Health Promot 2021;10:117. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_988_20.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Gonzalez, L, Nielsen, A. An integrative review of teaching strategies to support clinical judgment development in clinical education for nurses. Nurse Educ Today 2024;133:106047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2023.106047.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. van Diggele, C, Roberts, C, Burgess, A, Mellis, C. Interprofessional education: tips for design and implementation. BMC Med Educ 2020;20(Suppl 2):455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02286-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Liu, ZJ, Sun, ML, Zhang, HY, Guo, W, Wang, BQ, Zhou, T, et al.. An exploration of the training and evaluation systems of medical undergraduates in the context of tutorial system. Chin J Med Educ Res 2019;5:458–61. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-1485.2019.05.007.Search in Google Scholar

12. Ren, ZL, Yu, N, Zhang, ZG, Ma, GM, Yu, Y, He, TP, et al.. Application effect of under-graduate tutorial system combined with PBL teaching in improving comprehensive ability of medical imaging students. Clin Res Pract 2019;4:187–9. https://doi.org/10.19347/j.cnki.2096-1413.201907076.Search in Google Scholar

13. Ali, K, Zahra, D, McColl, E, Salih, V, Tredwin, C. Impact of early clinical exposure on the learning experience of undergraduate dental students. Eur J Dent Educ 2018;22:e75–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12260.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Feng, GJ, Xing, J, Lian, M, Huang, D, Feng, XM. Application of early clinical contactearly clinical exposure in teaching dental medicine. Med J Commun 2019;33:540–2. https://doi.org/10.19767/j.cnki.32-1412.2019.05.041.Search in Google Scholar

15. Lv, RY, Liu, HX, Chen, QQ, Wang, J, Han, BL. The application of the PDCA cycle combine with PBL teaching method in undergraduate dental student clinical practice. Chin J Dent Mater Devices 2017;26:107–9. https://doi.org/10.11752/j.kqcl.2017.02.10.Search in Google Scholar

16. Li, YC, Pu, J, Xu, JM, Wang, Z, Li, Y, Cao, DP. Research progress of early clinical exposure in medical colleges and Universities in China: a review. Chin J Med Educ Res 2019;18:757–61. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-1485.2019.08.001.Search in Google Scholar

17. Wang, Y, Tang, Y, He, Y, Zhu, YQ. Effect of doctor-patient communication education on oral clinical practice. Shanghai J Stomatol 2012;21:474–7.Search in Google Scholar

18. Alvarez, S, Schultz, JH. A communication-focused curriculum for dental students – an experiential training approach. BMC Med Educ 2018;18:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1174-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.