Abstract

With the increasing proliferation of the internet, audience-authored online paratexts continue to gain significance in culture and in the communicative structures of narrative texts. This article takes a critical look at the ways in which Gérard Genette’s concept of paratext (1987) has been used in contemporary scholarship. The article offers a model of online paratexts based on an interdisciplinary understanding of paratextuality and internet-age culture. Ways in which paratexts become legitimate in online environments are considered through the analysis of HBO’s popular TV series Game of Thrones (2011–2019). Legitimation extends from production-authored paratexts to audience-authored paratexts, reflecting changes in the relationship between authors and readers typical to contemporary culture. Finally, the article introduces the concept of paratextual reauthoring, which refers to the practice of canonizing alternative interpretations of texts via the use of online paratexts.

A paratext is a vestibule, a threshold of a text. That threshold has no clearly defined boundary: it is a zone of influence that encompasses everything between the text itself and the purely off-text. Paratexts are the fringe that presents a text to the outside world, influencing its reading. All authorial commentary is communicated firmly within this vestibule, as is all commentary perceived as more or less legitimated by the author (Genette 1997a: 2). The cover of a physical book, or more recently the box of a blu-ray release, is the prototypical location of paratexts. Paratextual elements, such as the text “An HBO Original series – Game of Thrones – The Complete Series”, serve to guide the reader. These designations activate context-dependent frames of interpretation, such as knowledge about HBO Original series as a genre, or about Game of Thrones as a culturally impactful work of fiction. These frames are brought into the process of interpretation and impact it even before reading (see Rabinowitz 1987).

In recent years Gérard Genette’s classic concept of paratext has enjoyed a surge of newfound popularity. Adapting the concept to contemporary use requires that its borders are expanded to include many features of online texts. These online texts are fundamentally new: they are produced, distributed, and used in ways that are different from any texts that existed before the advent of networked digital technologies. The logic of the internet, of networked computing, has come to dominate contemporary cultural production as well as many other facets of human society in the convergence era (e.g., ITU 2022). Transmedia storytelling proliferates, and audiences become accustomed to integral elements of fiction being dispersed across multiple delivery channels and platform (Evans 2018: 244). While some scholars trace the beginnings of these practices back to the campfires around which humans gathered to share stories in the dawn of culture, or to the negotiations of religious canon and dogma from the late-Antiquity to the early-Middle Ages, even they rarely dispute the role of the internet in the modern iteration of transmedia storytelling (see Richards 2016: 17–20).

An updated understanding of paratextuality has potential to serve as an angle of approach to subjects like online discourse that congregates around texts, and the structures of marketing that have come to subsume all narratives, fictional and otherwise. I seek to systemize some of the various, sometimes vague conceptions of changing digital paratexts into a synthetized model of online paratexts. I will further refine that model and apply it to HBO’s immensely popular TV series Game of Thrones (2011–2019; henceforth referred to as Thrones) and the online discourse surrounding that series. I will analyze and discuss various uses and consequences of online paratexts in the context of internet-age fiction. These consequences manifest, among other effects, as changes in the dynamics between the author and the reader, or production and audience.

When texts go online through paratexts and become entangled with the mesh of internet discourse, I argue, institutionally authoritative agents such as authors, producers, and publishers start losing control over the substance and meaning of those texts (see Hassler-Forest 2016). That control is ceded to a shared story about the original text: “a retelling, produced by many tellers, across iterative textual segments, which promotes shared attitudes between its tellers” (Page 2018: 18). Texts, their online paratexts and the shared stories that emerge from their interaction function together much like interactive digital narratives (IDNs) (cf. Basaraba 2018: 48). Texts that are engaged in online discourse undergo, in other words, continuous paratextual reauthoring.

1 Limits of paratexts

The paratext is, as Genette himself put it, “a zone not only of transition but also of transaction: a privileged place of a pragmatics and a strategy, of an influence on the public” (1997a: 2). According to Birke and Christ, the paratext “manages the reader’s purchase, navigation and interpretation of the text” (Birke and Christ 2013: 68). Paratexts have the power to influence interpretation, the assignment of meanings to ideas. The study of paratexts is, as Jonathan Gray puts it, “the study of how meaning is created, and of how texts begin” (Gray 2010: 26). That creation of meaning has significant economic and political implications: the financial prospects of contemporary commercial works of fiction, at least, seem to be deeply impacted by the stories shared about them (see Pesce and Noto 2016: 1). There is power in paratexts, and a struggle over the ability to wield that power is taking place in contemporary media spaces. Up to two thirds of a blockbuster film’s budget may be spent on marketing, on controlling the paratextual fringe of an entertainment product (Gray 2010: 7).

I approach online discourse regarding a given text as paratextual. It exists on the borderlands between a narrative text and internet discourse at large. From Genette’s point of view this would stretch the definition of paratextuality, as even epitexts, paratexts that exist wholly separately from the book-as-object text, are defined by explicit legitimation by “some authorial assent or even inspiration” (1997a: 348). If this new usage of paratextuality is incorrect, then why adopt it? Why not heed Genette’s own warning against expanding the definition of paratextuality too much (407)?

When it comes to the choice of term, the readily available options to paratext from Genette’s theory are metatext and hypertext. Both terms, as defined by Genette, would take us far too far from a communicative, two-way relationship that can exist between a text and the online discourse surrounding it (1997b: 7). Neither metatext nor hypertext can claim the privileged position of paratext, which is perceived as being able to legitimately interact with the original text, to influence its reading. A new concept could reasonably be introduced and added to Genette’s model. Paratextuality could remain as a term that refers to things analogous to covers of physical books or author interviews. This approach of leaving the definition of paratext alone, regardless of the changing of contemporary media environments, has been taken by many scholars (cf. Birke and Christ 2013; McCracken 2013). Some notable developments in paratexts can be identified from this perspective as well: digital artefacts such as the metadata of a file can be thought of as paratextual (Cronin 2014: 2). However, the relative obscurity of such data compared to traditional paratexts renders them, in my view, niche when considered as a channel of communication. In fact, metadata is generally supposed to fade into the background unnoticed (Pomerantz 2015: 1), whereas paratexts function by explicitly framing and contextualizing a text (Genette 1997a: 407).

To fully appreciate how significantly the forms of paratexts have changed over the past few decades, we must look beyond the trappings of individual texts. As Genette himself writes, the borders of paratexts are malleable and the “ways and means of the paratext” vary greatly over time depending on “period, culture, genre, author, work, and edition” (1997a: 3). He acknowledges that the proliferation of the type of discourse around texts he calls paratextual is a product of a modern “media age” (3). Genette formulated his theory in the 1980s, and our contemporary media has changed significantly since then. For example, Genette’s subdivision of paratextuality into peritextuality and epitextuality is clearly a relic of an age before transmedia culture. In the age of the internet the distinction between paratexts that are and are not physically connected to the text itself is near meaningless: texts have been uncoupled from their corporeal manifestations. The physical screen-device I use to consume media such as ebooks can function as the de facto peritext of every single novel I read (McCracken 2013: 106). This does not mean that the book-as-object no longer exists, but it is clear that a text is not a book.

Genette’s definition of the concept has, then, become outdated. This can be seen in two significant aspects of paratexts: a) the forms of paratexts have changed, and b) the potential sources of legitimate paratexts have expanded. The most clear-cut changes in the forms of paratexts, such as the emergence of metadata, result from the technological affordances of networked computing. However, I will argue that cultural practices related to the production and uses of paratexts have changed beyond such mechanical considerations as well. The inevitable context of internet discourse fundamentally changes the communicative relationship between author and audience, it brings forth a new type of media age (transmedial, participatory) which in turn results in a proliferation of a new type of discourse around texts (online discourse). From online discourse emerge new potential sources of paratexts, beyond “the author and his allies” whom Genette considered as the sole legitimate originators of paratexts (1997a: 2).

I refer to aspects of our contemporary media age through two related theoretical frames. These are participatory culture (Jenkins 1992; Jenkins 2018), and transmedia culture (Evans 2020). Participatory culture refers to contemporary cultural artefacts including more opportunities for audience participation, and to audiences becoming active parts of production, demanding those opportunities to participate (see Jenkins 2018: 18). Transmedia culture, in turn, refers to the pervasiveness of “movement across and through a media landscape in which content is everywhere, spread across any device” (Evans 2020: 9). In transmedia culture, content, fictional or otherwise, is dispersed across media borders and intertwined with other content in such a way that even single media texts turn into “transmedia experiences”, rendering platform-defined approaches to texts outdated (Evans 2018: 244). The concept of participatory culture is aligned to the point of view of readers, while transmedia culture is more concerned with texts and their uses in contemporary media environments.

2 Expanding definition: online paratexts and the narrative text

The ways the term paratext is used have expanded and changed, because paratexts themselves have changed. That change is facilitated by developing digital technology and encouraged by ongoing cultural shifts which are in the process of restructuring the ways we interact with various texts and narratives. These changes have exposed the limitations of the concept of paratexts as defined by Genette, inspiring many scholarly efforts to adapt the concept to contemporary use. Most of the renewed interest in paratextuality has originated in the fields of media studies and game studies (cf. Consalvo 2007; Desrochers and Apollon 2014; Gray 2010; Pesce and Noto 2016), but a separate strain of new usage also exists in literary theory (cf. Birke and Christ 2013; Lindgren Leavenworth 2015; Sedlmeier 2018).

The beginnings of these changes can be traced back as far as to 1999, the dawn of the era of commercial mainstream internet, some years before the arrival of so-called Web 2.0, when Peter Lunenfeld wrote that the domain of paratexts has expanded for digital texts in such a way that it and text have become almost indistinguishable from each other (1999: 14). According to Lunenfeld, borders between discrete texts have started to lose their meaning. “An ever-shifting nodal system of narrative information” is taking the place of distinct texts (15). He declared that this shift in textuality has fundamentally changed the nature of narratives (15). Following a similar line of reasoning Jonathan Gray, a media scholar, notes that the phrase “don’t judge a book by its cover” translates in a 21st-century media environment into “don’t believe the hype” (2010: 3) – although as the theory of paratextuality teaches us, we usually do judge books by their covers and believe the hype. As a result of this translation, both the text and the paratext have become more abstract: the cover of the book (the paratext) has been transformed into all-encompassing hype, whereas the book itself (the text) has disappeared altogether, having been replaced by whatever it is that is hyped. Transmedia culture facilitates engagement across many media, so it is not surprising that media specificity loses importance.

Mia Consalvo’s influential (2007) book Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Videogames introduces in the field of game studies the trend of referring to all external elements which influence the experience of gaming as paratexts (21). Consalvo takes Lunenfeld’s stance on the topic as a starting point: for her, too, paratextuality has expanded far beyond what narratologists would consider paratexts. Consalvo examines the influence of games industry, as well as the wider media industry, on players’ gaming experiences and arrives at the conclusion that paratexts are not peripheral to games as a medium: they are central to both the industry and the player community (182). Paratexts of games are sites of power, of gaming gapital: they teach players not only to play games, but also canonize socially accepted ways to approach them and play a central part in defining what it means to be a gamer (22). This power to define meanings and identities leads to a struggle between “players, developers, and interested third parties [as they] try to define what gaming capital should be, and how players should best acquire it” (184). Similar struggles over the control of paratexts exist in other media as well.

Making and distributing videogames (or movies for that matter) is a significantly more complex process than writing and publishing novels. It is usual for blockbuster games to have hundreds of people working on different parts of them simultaneously for years. Those responsible for narrative content of major videogames must constantly consider technical limitations and realities of game development when exercising their craft. Videogame narratives are almost always created by many people, and they are much more visibly entangled with the realities of the games industry than literary narratives are with the publishing industry. It makes sense, then, that Genette’s definition of the power of paratext as something that arises from authorial legitimation (with its source as either the singular author or publisher) has been ignored or met with skepticism in game studies and media studies.

Gray advocates for an understanding of a text as “a larger unit than any film or show” (or novel) which consist of “the entire storyworld as we know it” with paratexts contributing to our knowledge of that storyworld just the same as the media they proliferate around (2010: 7). Similarly, Dehry Kurtz and Bourdaa write about expanding the borders of text to include transmedia worldbuilding and online paratexts. They call this whole a transtext (Dehry Kurtz and Mélanie 2016: 1–2). From a perspective like this, paratexts are not only the fringes through which texts are approached, but also expanded parts of the text itself. In addition to providing frames for interpreting texts, paratexts can also function as tools for engaging with them further after reading (Gray 2010: 10–11). This facilitation of continuing engagement with a text illuminates the synergy between paratextual practices and culture as a whole: after all, engagement is located at the center of the stage in transmedia culture, with engagement defined as the kind of privileged attention which functions both as a commodity and a currency in the attention economy (see Evans 2020: 148–149).

With everything I have discussed thus far in mind, I offer a refined definition of paratext: a paratext is a text (of any type) about another text which

facilitates engagement with the storyworld of the original text,

has influence over the interpretation of the original text, and

is perceived as legitimate (to some degree).

I proceed with the term online paratextuality, which refers to a network of texts that exists (primarily) on the internet and has a degree of perceived legitimacy and privilege over the interpretation of the original text. From this network of texts are constructed various “instantiated narratives” or “emergent narratives” (see Basaraba 2018: 49).

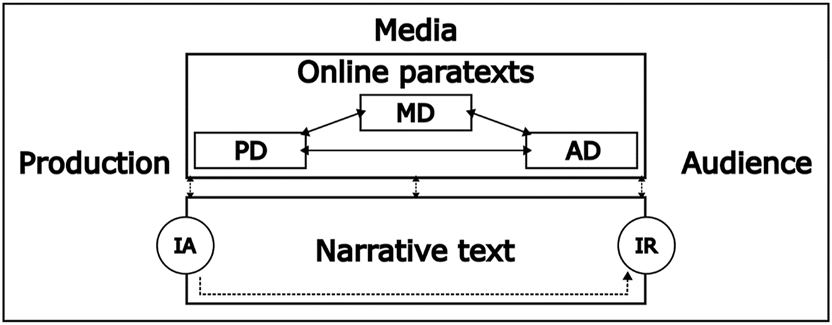

In Figure 1 I have laid out the structure of communication as it relates to online paratexts of narrative texts. The model is based on those drawn up by scholars like Wayne C. Booth (1961) and Seymour Chatman (1978). Communication within a narrative text is not filled in, but layers upon layers of narrators, narratees and other textual agents and devices could be added. I have foregone mention of “reader” and “author” in this depiction in favor of the categories of “production” and “audience”. Production here is broadly synonymous with what Gray calls “Industry” (Gray 2010: 23). As we can see, implied author (IA) is a function of narrative on the side of the production whereas the implied reader (IR) resides in the domain of the audience. Online paratexts and narrative texts are connected to each other indirectly, but still interact and materially influence each other. This connection can be created, recreated, and reinforced by production, by audience, or by the features of the narrative text itself. The three arrows between narrative text and online paratext in Figure 1 depict this.

Narrative text and online paratexts.

Online paratexts are a secondary avenue, parallel to narrative texts themselves, of communication between the authorial supercategory of production and the readerly one of audience. This communication flows both ways in a more concrete way than communication within a narrative text does: production influences audience and audience influences production. Many diverse types of online paratexts exist. In Figure 1 I have divided them into three distinct categories, with those categories being production discourse (PD), media discourse (MD), and audience discourse (AD). Production, audience and media can each act within any of these discourses. Production discourse includes paratextual practices such as the creation of official websites and marketing materials like trailers for a work of fiction. Media discourse consists of materials (articles, blog posts, videos, and such) that are concerned, at least on surface, on informing the public about a text. Due to the nature of online media, media discourse tends to regurgitate significant amounts of content that originates from either production discourse or audience discourse. Audience discourse in turn is constituted by discussion, debate, review, comment, transformative work (such as fan fiction) and much more. Production, media, and audience as actors can engage in any of these discursive categories, yet there exist types of paratexts that are most typical for each of these actors.

The model I have presented here is necessarily incomplete. Most notably it lacks a temporal dimension. It does not explicitly distinguish between the varied temporal dynamics of distinct types of paratexts. Gray, for example, separates paratexts into two categories: entryway paratexts which influence a reader’s entrance to the text and in medias res paratexts which influence the reader during or after reading (Gray 2010: 23). While this separation of categories is worth keeping in mind, it doesn’t seem necessary to maintain from the point of view of this article any more than does Genette’s separation of paratexts into peritexts and epitexts. I focus here mainly on the communicative potential of in medias res paratexts, yet much of it is applicable to entryway paratexts as well: in fact, often the same paratexts can act as either, or both, for different sections of the audience.

Perhaps a more profound result of this timelessness is the invisibility of ephemeral digital media, a difficulty in noticing the difference between permanence and obsolescence as Pesce and Noto put it (see Pesce and Noto 2016: 1). These temporal dynamics gain heightened importance when we shift focus from active readers, who encounter and interpret texts, towards interactive or participatory readers, who also enact and co-create them (see Uricchio 2016: 156). An episode of Thrones will always remain the same, whereas the online discourse regarding it will ebb and flow over time, its contents forever evolving and changing. Many online paratexts, such as livestreamed videos and even official marketing materials for TV series, are ephemeral: they will fade over time and become accessible only through internet archives, if at all. Remembering that online paratexts are not temporally static in relation to their subject texts is, then, an important addendum to this model.

3 Perception of legitimacy

From the perspective of game studies, it is clear that the domain of production is a vast jumble deeply entangled with media and audience. This entanglement may not be as obvious when focusing on the types of case studies literary studies usually focus on. However, just as the importance of book-as-object has lessened with the continued proliferation of the internet, so has the role of authoritative literary institutions on audience engagement with narrative texts. As Roswitha Skare points out, insistence on paratexts arising only from either the author or the publisher of a work is flawed (Skare 2020: 512). The creation of any published text is more complex than Genette’s model implies. It is impossible for a reader (or a scholar) to objectively decipher the level of legitimacy of any paratext. This question of authorization consistently arises as the point of departure when discussing paratexts in narrative studies and in other fields. While I broadly agree with the position that Genette’s emphasis on authorial legitimation in defining paratexts is outdated at best, ignoring the impact of perceived legitimacy on the power of paratexts is still problematic.

The privileged status of the paratextual position is important for its ability to influence the perceived meaning of a text itself: this privilege differentiates paratexts from non-authoritative discussion about texts. The privileged status of paratext is granted to a discourse by the audience’s perception of legitimacy. This perception of legitimacy is constructed through many means, with standard, explicit indicators of authorial legitimacy being just one of them. I am not convinced that there is any meaningful difference between paratexts that are genuinely legitimated by production, and paratexts that are merely perceived as legitimate. Gray takes this further by stating that the primary difference between paratexts created by industry and those created by audiences is circulation: audiences do not have the resources, infrastructure, or uniformity to spread their paratexts as widely as Hollywood does (Gray 2010: 143). Insofar as audience discourses can generate a perception of legitimacy for themselves with no help from production, I agree.

The distinction between online paratextuality and mere commentary regarding a work is primarily a reading effect, a matter of perception. Most contemporary texts can be, and routinely are, read in ways that are completely unadulterated by the internet. This ignorability is not particular to online paratexts: when it comes to most paratextual elements, the reader can always elect to take them into consideration or not (see Skare 2020: 513). Even if some readings ignore paratexts, those paratexts still function to frame any text. Thrones exists as a story that stands alone and can be read as such. Thrones also exists as an adaptation, a text that is saturated with intertextuality to George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire. These levels of textuality are the usual fare of literary studies. However, Thrones also exists as text that is connected to a web of online paratexts. These paratexts serve as the interface that embeds this internet-age text to a network of online intertextuality: a mesh that is formed by countless texts and their overlapping or otherwise connected paratexts. Perceived legitimation of paratextual content means that this mesh bleeds towards the text and becomes an important part of that text’s communicative structure.

Important distinctions still remain to be made, though: who perceives some paratexts as more legitimate than others and why? How can these privileged paratexts be identified, if we are to move beyond the appeal to the original author that Genette advocates for? Stanley Fish’s old concept of interpretive communities (1980) has also been adapted to the needs of analyzing different media environments (e.g., Buozis 2022; Zelizer 1993). Barbie Zelizer describes journalists as an interpretive community engaged in producing a “shared discourse and collective interpretation of key public events” (1993: 219). Michael Buozis in turn argues that online communities discussing media on sites such as Reddit.com constitute similar interpretive communities (2022: 650). Journalists have institutional authority to broadcast their shared interpretations of texts and events in public discourse, but as Paul Dawson points out, the logic of virality and the fragmenting of the public sphere into “homophilic clusters” in the age of social media has enabled alternative sources of perceived authority to emerge (2023: 73).

The answer to the question of who perceives some paratexts as more legitimate that others is, then: interpretive online communities and their audiences. Membership in these communities, fuzzy and often transitory, is mostly based on their visibility and ability engage audiences in discussion. More prominent online communities, like the Game of Thrones forum on Reddit.com with more than three million registered users, have more impact on the public discourse than smaller ones. However, because of the decentralized nature of the internet and the logic of virality, shared interpretations that become dominant in many online communities can easily arise in any of them. Because the perception of legitimacy of paratexts is contingent on the shared discourses of interpretive online communities, it is impossible to create a firm list of the indicators of paratextual legitimacy. Analyzing the contents of online discourse can reveal which paratexts are considered legitimate by individual interpretive communities, however. Corpus-assisted discourse analysis in the vein of Ruth Page’s approach to shared stories (see Page 2018: 45–46), while outside the scope of this article, might also be helpful in identifying which particular paratexts are perceived as legitimate in online discourse.

4 Game of Thrones and its online paratexts

Thrones, dubbed by Time Magazine “the world’s most popular show” (D’Addario 2017), was undoubtedly a success for HBO. It is rare for a piece of fiction to capture the entirety of the cultural zeitgeist in the way that Thrones did. A cottage industry of supplemental paratextual content was created by HBO themselves, by various ad-monetized entertainment news-sites, by other production companies and, most pertinently, by the show’s audiences. Structures for the creation of an audience-driven media industry were mostly in place when Thrones’ cultural dominance begun, with Harry Potter fandom and other similar fan communities having already firmly entrenched themselves online during the previous decade.

The spreading of the internet played a central role in the proliferation of paratextual discourse around Thrones, as did the nature of the series’ story, which turned out to be a perfect fit for kickstarting an empire in the internet’s attention economy. Some enterprising fans who had read A Song of Ice and Fire (Martin 1996–), the book series Thrones is based on, secretly filmed the reactions of their uninitiated friends to some of the more shocking turns in the story, such as the beheading of Eddard Stark, who initially seemed like the obvious main character of the series. After being uploaded to YouTube, many of these reaction videos featuring people crying in shock over Stark’s surprising death gained viral status, encouraging the creation of such content further.

In 2013 George R. R. Martin, the author of A Song of Ice and Fire, appeared on the talk show Conan with Conan O’Brien. He was filmed viewing a sampling of fan-filmed reaction videos to the climax of “Rains of Castamere”, the penultimate episode of the third season of Thrones. In that episode Robb Stark, the eldest son of Eddard, attends the wedding of his uncle. The wedding takes a dark turn as Robb is murdered alongside his army, his pregnant wife, and his mother. These brutal and explicitly depicted acts of violence are perpetrated by the family of the bride, who have switched sides and sold the Starks to their enemies. Martin’s televised mischievous cackling in response to his audience’s shocked reactions served to build his authorial mythos as a cruel writer who constantly kills off fan favorite characters. However, it also legitimated audience discourse by including viewer created content in what is undoubtedly a production authorized paratextual space. This is a simple example of production visibly engaging with audience-authored paratexts. As similar cases abound, they begin to form an impression of profound changes having taken place in the relationship between production and audience.

The production of Thrones used audience-authored paratexts in ways that went beyond simple acknowledgment as well. In the final episode of the third season of the series Gendry Waters, the illegitimate son of the previous king, is saved from ritual sacrifice by the smuggler Davos Seaworth, also known as the Onion Knight. Davos frees Gendry from his cell and, under the cloak of night, smuggles him to the shore of the island, where Gendry is provided with a rowboat. Left to fend for himself, rowing inexpertly on the open sea, Gendry is not seen again for more than three seasons, or four years. This strange disappearance of a well-liked character led to much discussion online, and the creation of many memes and other audience-authored online paratexts. This started with shared, viral comments such as “After each episode’s credits there should be a clip of Gendry still rowing to Westeros” (Reddit 2015) which in turn lead to the creation of videos and images depicting just that. Buzzfeed and other ad-monetized online magazines published collections of Gendry-related audience paratexts (see Guillaume 2014). The contents of these early paratexts are now mostly lost to ephemerality. As time passed and Gendry remained lost, more transformative online paratexts were created. Many assumed that Gendry’s plot was abandoned, never to be mentioned again, so images were created in which Gendry was rowing his boat, now named “S. S. Abandoned Plotlines”, with characters from other dropped plots as his passengers (Reddit 2017).

Audiences reframe aspects of Thrones to amuse themselves, and to reflect and criticize the source material. This is a demonstration of audience-authored paratexts engaging in narrative practices, in paratextual storytelling. The question of legitimation becomes pertinent when we consider the fact that the production of Thrones participated in discussing and encouraging these audience-authored online paratexts from nearly the beginning. Joe Dempsie, the actor who played Gendry, posted “Still rowin’ … #GoT” on Twitter a year after the last appearance of his character, which clearly encouraged audience discourse on this topic (Harris 2019). Further still, the creators and primary writers of Thrones, Dan Weiss and David Benioff, threw their hat in the ring and embraced the memes wholeheartedly when they appeared on UFC Unfiltered Podcast:

Dan Weiss: “He’s still rowing.”

David Benioff: “Yes, he’s still rowing. It’s a long, a very long –”

Dan Weiss: “He’s coming up on Florida.”

David Benioff: “He’s getting in great shape. Think of the shape he’s in after rowing for four seasons.”

Dan Weiss: “Big lats.” (Kleinhenz 2016)

This co-opting of audience-authored online paratexts, when it comes to Gendry rowing, continued further when a reference to the memes was incorporated into the text of Thrones itself. Gendry finally returned to the series in the fifth episode of season seven. Davos Seaworth, the same character who launched Gendry upon his nautical quest, journeys to retrieve him from a smithy located in the kingdom’s capital, King’s Landing. Because Davos knows where to find Gendry, it is clear that hiding him in the enemy capital had been the plan all along. However, when the characters meet, Davos quips, “Thought you might still be rowing.” This line is nonsensical from the perspective of the internal logic of Thrones: it becomes comprehensible only through familiarity with the specific audience-authored paratexts I described earlier. This, of course, led to countless online paratexts being created within the realm of media discourse: multiple articles broadcast this inclusion of audience-authored paratexts into Thrones’ primary storyworld, spreading knowledge of paratextual practices and their seeming legitimacy (e.g., Hornshaw 2017).

Such phenomena lend credence to the idea that audience paratexts may have affected Thrones in more complex cases as well. As Henry Jenkins points out, conversation on social media sites have “an expanding capacity to set cultural and political priorities”, and audiences exploit these capacities for the purposes of, among other things, “making demands upon broadcast content” (2018: 13). For example, it is tempting to speculate that online discourse on the careless depictions of sexual assault in Thrones led to changes in the show’s storyworld. Explicit depictions of sexual violence become less common as the series progresses, but it is difficult to determine if audience discourse played a part in that reduction because representatives of production never explicitly commented on the topic. However, these changes take place concurrently with Thrones’ problematic portrayals of sexual assault becoming a common topic of paratextual online discourse about the series (e.g., Pantozzi 2015).

When it comes to contemporary fiction in transmedia culture, it is common for production to actively encourage participation in the form of audience-authored paratextual content (see Fatallah 2016). Such practices are enabled by the technological affordances of internet-based platforms like social media applications and news sites (see Roine and Piippo 2021). A major reason for production companies to encourage participation is, of course, the perceived potential of active fandom to convert bystanders and casual readers, viewers, and players into loyal advocates. As Melanie Kohnen has pointed out, those responsible for marketing Thrones believe that courting fans through interactive paratexts is the reason behind the astonishing success of series (Kohnen 2018: 337; see also Campfire 2012). Visible paratextual audience activity acted to cement Thrones as a work of fiction that one should follow to stay up to speed with cultural discourse (see Castleberry 2015: 127). The White House tweeted memes about Thrones under both Obama and Trump. Thrones became the quintessential example of Event TV (cf. Giuffre 2012): even its trailers were approached as news stories instead of advertisements.

5 Contested authority

Authorship is a form of power over a text, meaning, and culture (Gray 2016: 35). The influence of paratexts on the meanings of texts has always been vast: after all, paratexts are the spaces that make authorship explicit by defining the authorial point of view (see Genette 1997a: 408). When texts are exposed to the logic of networked audiences in the contemporary storytelling environment of the internet, production loses control of their meanings. The authorial point of view espoused by production is replaced by that of audience-authored paratexts that circulate online as shared stories (see Page 2018). These stories create their own legitimacy, their own authorial position, through an almost tautological process of sharing and resharing: a post that is shared by many users and written about in the media gains legitimacy because of that sharing, and as it gains legitimacy it becomes more easily shared and therefore more legitimate (see Dawson and Mäkelä 2020; Mäkelä 2021).

When texts like Thrones are untethered from authorial control, their ability to “set cultural agenda” (Jenkins 2018: 13) becomes available for anyone to exploit via the means of “paratextual re-authoring” (Gray 2016: 35). Gray’s idea of paratextual reauthoring is useful but significantly underdeveloped: the term reauthoring is more familiar to narrative therapy than to narrative studies. As I would conceptualize it, paratextual reauthoring refers to the manipulation of a text’s culturally perceived meaning through the intentional use of online paratexts to recontextualize the original text. The beginnings of this idea of paratext as something that is capable of substantially transforming the text itself exist in Genette’s definition of paratexts as spaces in which “the author and his allies” negotiate with potential readers for transactional advantage (Genette 1997a: 2). As I’ve established, online paratexts supplant authorial agency with the perception of legitimacy created by the logic of networked audiences.

Most of the recent paratextual reauthoring of Thrones has revolved around the fandom attempting to come to terms with the disappointing ending of series. I have written elsewhere, for example, about the ways in which the theme of anthropogenic climate change was perceived to fall apart in the last season of Thrones, and about the paratextual fandom discourse trying to make sense of that (Laukkanen 2022). In the immediate aftermath of the ending of Thrones the narrative put forward by many widely shared memes and other audience-authored paratexts was that of hubris and a fall from grace. For example, reddit used @Old_Kinderhook_ shared an image titled “The legacy of a bad ending” which depicted marketing posters of The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and Thrones next to each other. The Lord of the Rings part of the image read “Ended almost 20 years ago – Fandom going strong and millions still rewatch” Harry Potter part of the image read “Ended 10 years ago – Fandom going strong and millions still rewatch” and Thrones part read “Ended 1 year ago – Fandom is dead and nobody wants to rewatch” (Reddit 2020). This post has almost a hundred thousand likes and thousands of comments. While the truth is that Thrones never lost its status as one of the most streamed TV series in the world from the time it ended to present day (Clark 2022), this narrative of Thrones losing its cultural relevance dominated after the ending of the series disappointed many in the fandom.

Regardless of the potential economic gain, inviting online audiences to co-construct billion-dollar franchises is a fraught practice from the viewpoint of production, as it involves giving up authorial control. To counteract that loss, production can wield economic and institutional power to prioritize certain types of audience-authored paratexts over others to canonize specific audience interpretations as correct, and others as incorrect (see Scott 2013: 325). As Jenkins notes, production can still greatly influence the meanings that are assigned to texts even in our changing, internet dominated media landscape (Jenkins 2018: 13), although leveraging this influence has become a complicated process. This is exemplified by HBO’s attempts to retain authority over their most profitable franchise by inserting themselves into the middle of audience discourse.

Thrones’ production embraced the memes about Gendry still rowing yet remained silent regarding the audience discourse about depiction of sexual assault in the show. This contrast illustrates the tendency of production to privilege some audience paratexts and label them as “quality fandom” (Kohnen 2018) while shunning others. When the sixth season of Thrones was airing, HBO attempted to explicitly define quality fandom through example, by creating supplemental paratexts resembling audience-authored ones. Following each new installment of Thrones, a 30-min episode of a talk show called After the Thrones, with the slogan “Fan the flames of your fandom!”, was broadcasted. In this after-show, Chris Ryan and Andy Greenwald enthused about the latest episode of Thrones. Ryan and Greenwald are both journalists and TV producers, but here they were presented as fans making a show for other fans. The first episode of After the Thrones begins with the following exchange:

Ryan: “This is After the Thrones. Every week, we’re going to be bringing you analysis, jokes, the whos, the whats, the whens, the wheres, the WTFs of this entire Game of Thrones season six.”

Greenwald: “This is the place for hopefully smart conversation, wild speculation and, I pray, some Dornish wine recommendations.”

Ryan: [laughs]

Greenwald: “Think of it this way: If Game of Thrones, the show, is Brienne of Tarth, we are Podrick.”

Ryan: “Yeah, following behind but woefully bad at hunting.”

(Greenwald and Chris 2016, 00:22–00:51).

This banter acts to emphasize that After the Thrones is an authentic part of fandom. The first line, uttered by Ryan, is written in idiosyncratic language of fan influencers. The mention of “WTFs” particularly strikes a specific note: one of the most popular creators of Thrones related fan videos, Charlie Schneider, whose YouTube channel is titled “Emergency Awesome”, framed many of his popular recap videos of each episode of Thrones as “Top 5 WTF Moments”. The wording in After the Thrones serves to evoke these authentic fandom spaces. The second line by Greenwald consists of what amounts to an almost stereotypical description of Thrones fandom as very involved, somewhat cerebral, and sometimes pretentious. The self-deprecating mention of wild speculation refers to the fandom’s well-known habit of creating borderline conspiratorial fan theories about the plots and the storyworld of Thrones.

The last two lines, which reference the swordswoman Brienne of Tarth and her hapless squire Podrick, constitute the most important part of the exchange. Brienne and Podrick had become a darling duo of the fandom by the time After the Thrones was created. Brienne was often pointed to as an example of Thrones’ underlying feminist sensibilities, particularly when the series was criticized for its depictions of sexual violence. Podrick on the other hand earned the fandom’s adoration for his innocent demeanour combined with the implication that prostitutes would not accept payment from him due to his hidden yet apparently fathomless sexual prowess. This combination of traits endeared Podrick to the fandom and ensured that he became a mainstay in memes created about Thrones. By comparing itself to Podrick, After the Thrones communicates that it is much less important and less interesting than Thrones itself, yet in that same line of dialogue it also extends a hidden nod towards the fandom, indicating its status as an authentic fan created text.

That sense of belonging to fandom spaces, of being part of authentic audience discourse, was an obvious façade. Most tellingly, After the Thrones was broadcasted on HBO’s own channels, in the heart of production discourse. Through the antics of Ryan and Greenwald, HBO projected outwards a neutered facsimile of the Thrones fandom. Through that projection overflowing with indicators of authenticity, the fandom was portrayed as being content with the direction of Thrones and engaged in positive fan-activities like the creation of fan theories and viral memes. Meanwhile parts of the genuine fandom, having started becoming disillusioned with Thrones by season six, were engaged in debates over defining the show’s relation to questions like climate change and feminism. Those are divisive topics, however, so they were summarily shut out of HBO’s showpiece of what approved quality fandom looks like. The production of Thrones attempted to take part in the creation of audience discourse and to shift it to match their preferred vision of participatory audience engagement. HBO acted to protect their claim to the authorship of Thrones by reinforcing their own authorial position through paratextual reauthoring.

Because of the ephemerality of digital texts, paratextual reauthoring is a perpetually ongoing process: as time passes, earlier online paratexts fade to obscurity and new ones take their place. Canonized interpretations build upon earlier reauthorings of a text, even if some of those origins are lost to time. Gendry’s “S. S. Abandoned Plotlines” has lost much of its meaning and relevance now that Thrones has ended, and most of the plotlines decried as abandoned ended up returning to the series after all, just like Gendry did. Especially after the first season of the Thrones spinoff prequel series House of the Dragon (2022–) aired and turned out to be a major, fandom reinvigorating hit, new types of paratextual reauthorings abound. They seek to reframe Thrones in relation to current topics of interest in fandom discourse.

The trend of tackling the ending of the series persists in newer audience paratexts, but it is cast as an anomaly to be isolated from the whole of Thrones’ extended storyworld. Instead of being depicted as a culmination of all Thrones’ flaws, the ending is now usually blamed on David Benioff and Dan Weiss, the creators of the series who allegedly grew bored of making the show and wanted to move on to directing Star Wars movies (see Lindbergh 2019). Reddit user @AnyhowGripe66 posted an image titled “LOTR & return of the GOT memes” in January of 2023. The image consists of two frames from The Lord of The Rings movies. First of these shows seven of the nine human kings to whom magical rings of power were given. The second frame depicts the dark lord Sauron secretly forging the One Ring through which he could control the kings and turn them into villainous Ringwraiths.

There are images of the covers of DVD sets for the first seven seasons of Thrones superimposed on top of the kings, and a text reading: “And seven seasons were gifted to the race of men/Who, above all else, desired quality.” The second image has the picture of the cover of Thrones’ last season on top of Sauron with the text “But they were all of them deceived./For another season was made” (Reddit 2023). This reauthoring of Thrones through intertextual reference into a Lord of The Rings parallel is, in many ways, exemplary of audience-authored paratexts in general. As is often the case with online paratexts, the narrative it engages with is a narrative about its subject text, and not the narrative of that text. @AnyhowGripe66 is not making a comparison between the stories of Thrones and The Lord of the Rings, but rather casting the cultural significance of Thrones into this metaphorical template: villains ruined Thrones and must be defeated. There is hope, though, as Sauron is defeated by the end of The Lord of The Rings. The world moves on, free of his oppressive shadow.

6 Conclusions

Direct acknowledgment by production is one of the most prominent ways in which the visibility and membership of interpretive online-communities spreads among audiences. When the creators of Thrones promote interactive, paratextual engagement as a marketing strategy for their franchise, they also bolster the power of online discourse to grant legitimacy to alternative paratexts. When HBO incorporated audience-authored paratexts into the primary text of Thrones, that effect was redoubled. To counteract the resulting loss of control, production can attempt to seize control over audience discourse. HBO attempted to do this by producing and promoting paratexts that looked like audience-authored ones, such as the talk show After the Thrones. It is unclear if the attempt lived up to expectations, but the prompt cancellation of the after-show suggests not.

The significant role that production plays in spreading and legitimating audience-authored paratexts should not be taken as a reinforcement of production as the sole source of legitimation. Rather, it demonstrates the way in which deeper involvement of texts in the communicative structures of the internet leads to further empowerment of the audiences. This involvement does not legitimate only some specific paratextual interaction with a primary text, but also the creation of audience-authored online paratexts as a practice. HBO’s attempt to retain control over the discourse surrounding Thrones reveals the extent to which the production of the series perceived interpretive online-communities and their paratexts as powerful. As many franchises have started to engage with audience-authored paratexts, they have become more than an isolated quirk of some contemporary works of fiction. The new production-audience relationship has turned into a part of contemporary media culture itself.

In this article, I have focused on narratives concerning Thrones and its production: these demonstrate the ability of audience-authored paratexts to wrest control from production over the meaning of a text. However, paratextual reauthoring can be used to engage with important societal debates, to influence opinions, and to campaign for concrete real-world change. Politically charged uses of paratexts dominate reauthorings of non-fictional texts, but they are not rare in the context of fictional texts either. Thrones’ communicative potential has been wielded extensively in the trenches of the so-called modern “culture war” (see Stanton 2021), in discussing such hefty matters as climate change and the role of feminism in contemporary society (see Laukkanen 2021; Laukkanen 2022). Further scholarship on such strategic uses of paratextual reauthoring is needed: as I’ve argued, online paratexts play a significant role in the communicative structures of the internet. They are a form of meaning making typical to online culture in that they are based completely on self-legitimating narrative logic. This means that they can function as tools of manipulation, and not only as tools that emancipate audiences from the tyranny of authors.

Funding source: Finnish Cultural Foundation

References

Basaraba, Nicole. 2018. A communication model for non-fiction interactive digital narratives: A study of cultural heritage websites. Frontiers of Narrative Studies 4(1). 48–75. https://doi.org/10.1515/fns-2018-0032.Search in Google Scholar

Birke, Dorothee & Birte Christ. 2013. Paratext and digitized narrative: Mapping the field. Narrative 21(1). 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1353/nar.2013.0003.Search in Google Scholar

Booth, Wayne C. 1961. The rhetoric of fiction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Buozis, Michael. 2022. Reddit’s cops and cop-watchers: Resisting and insisting on change in online interpretive communities. Convergence 28(3). 648–663. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211056798.Search in Google Scholar

Campfire. 2012. Game of Thrones case study. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/29285256 (accessed 24 February 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Castleberry, Garret. 2015. Game(s) of fandom: The hyperlink labyrinths that paratextualize Game of Thrones fandom. In Alison F. Slade, Amber J. Narro & Dedria Givens-Carroll (eds.), Television, social media and fan culture, 127–145. London: Lexington Books.Search in Google Scholar

Chatman, Seymour. 1978. Story and discourse: Narrative structure in fiction and film. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Clark, Travis. 2022. Game of Thrones is still one of the world’s most popular series, data shows, as HBO readies spinoffs including a new sequel about Jon Snow. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/game-of-thrones-still-one-of-worlds-biggest-shows-data-2022-6?r=US&IR=T (accessed 11 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Consalvo, Mia. 2007. Cheating: Gaining advantage in videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/1802.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Cronin, Blaise. 2014. Foreword: The penumbral world of the paratext. In Nadine Desroches & Daniel Apollon (eds.), Examining paratextual theory and its application in digital culture, xv–xix. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.Search in Google Scholar

D’Addario, Daniel. 2017. Game of Thrones: How they make the world’s most popular show, Time. https://time.com/game-of-thrones-2017/ (accessed 11 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Dawson, Paul & Maria Mäkelä. 2020. The story logic of social media: Co-construction and emergent narrative authority. Style 54(1). 21–35. https://doi.org/10.5325/style.54.1.0021.Search in Google Scholar

Dawson, Paul. 2023. What is ‘the narrative’? Conspiracy theories and journalistic emplotment in the age of social media. In Paul Dawson & Maria Mäkelä (eds.), The Routledge companion to narrative theory, 71–86. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003100157-8Search in Google Scholar

Dehry Kurtz, Benjamin W. L. & Bourdaa Mélanie. 2016. The world is changing … and transtexts are rising. In W. L. Benjamin, Dehry Kurtz & Mélanie Bourdaa (eds.), The rise of transtexts: Challenges and opportunities, 1–11. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315671741Search in Google Scholar

Desroches, Nadine & Daniel Apollon (eds.). 2014. Examining paratextual theory and its application in digital culture. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.10.4018/978-1-4666-6002-1Search in Google Scholar

Evans, Elizabeth. 2018. Transmedia distribution. In Matthew Freeman & Renira Rampazzo Gambarto (eds.), The Routledge companion to transmedia studies, 243–250. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781351054904-27Search in Google Scholar

Evans, Elizabeth. 2020. Understanding engagement in transmedia culture. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315208053Search in Google Scholar

Fatallah, Judith. 2016. Statements and silence: Fanfic paratexts for ASOIAF Game of Thrones. Continuum 30(1). 75–88.10.1080/10304312.2015.1099150Search in Google Scholar

Fish, Stanley. 1980. Is there a text in this class? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Genette, Gérard. 1997a. Paratexts: Thresholds of interpretation. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511549373Search in Google Scholar

Genette, Gérard. 1997b. Palimpsests: Literature in the second degree. Trans. Channa Newman & Claude Doubinsky. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.Search in Google Scholar

Giuffre, Liz. 2012. The coming of the second screen. Metro Magazine 173. 142.Search in Google Scholar

Gray, Jonathan. 2010. Show sold separately: Promos, spoilers, and other media paratexts. New York and London: New York University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gray, Jonathan. 2016. The politics of paratextual ephemeralia. In Sara Pesce & Paolo Noto (eds.), The politics of ephemeral digital media: Permanence and obsolescence in paratexts, 32–44. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Greenwald, Andy & Chris, Ryan. 2016. Season 1, episode 1. After the thrones. HBO.Search in Google Scholar

Guillaume, Jenna. 2014. Seriously, where is Gendry on Game of Thrones. BuzzFeed. https://www.buzzfeed.com/jennaguillaume/row-row-row-your-boat (accessed 11 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Harris, David. 2019. Joe Dempsie (Gendry) blames himself for those “still rowing” memes. Winter is Coming. https://winteriscoming.net/2019/03/19/game-of-thrones-actor-joe-dempsie-blames-gendry-still-rowing-memes/ (accessed 11 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Hassler-Forest, Dan. 2016. Science-fiction, fantasy and politics: Transmedia world-building beyond capitalism. London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield.Search in Google Scholar

Hornshaw, Phil. 2017. Ser Davos just referenced a Game of Thrones meme on Game of Thrones. The Wrap. https://www.thewrap.com/ser-davos-just-referenced-game-thrones-meme-game-thrones/ (accessed 11 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

ITU. 2022. Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2022. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. https://www.itu.int/hub/publication/d-ind-ict_mdd-2022/ (accessed 13 January 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Jenkins, Henry. 1992. Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Jenkins, Henry. 2018. Fandom, negotiation, and participatory culture. In John Booth (ed.), A companion to media fandom and fan studies, 13–26. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781119237211.ch1Search in Google Scholar

Kleinhenz, Marc N. 2016. Game of Thrones showrunners say Gendry is “still rowing”. ScreenRant. https://screenrant.com/game-thrones-gendry-still-rowing/ (accessed 11 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Kohnen, Melanie E. S. 2018. Fannish affect, “quality” fandom, and transmedia storytelling campaigns. In Melissa A. Click & Suzanne Scott (eds.), The Routledge companion to media fandom, 337–346. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315637518-41Search in Google Scholar

Laukkanen, Markus. 2021. Kuka kertoo, mitä Game of Thrones tarkoittaa? Post-postmodernismi ja paratekstuaalinen tarinankerronta [Who gets to tell what Game of Thrones means? Post-postmodernism and paratextual storytelling]. In Samuli Björninen (ed.), Kertomus postmodernismin jälkeen [Narrative after postmodernism], 77–104. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.Search in Google Scholar

Laukkanen, Markus. 2022. Literalixing hyperobjects: On (mis)representing global warming in A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones. In Marek Oziewicz, Brian Attebery & Tereza Dědinová (eds.), Fantasy and myth in the anthropocene: Imagining futures and dreaming hope in literature and media, 235–245. London: Bloomsbury Academic.10.5040/9781350203372.ch-035Search in Google Scholar

Lindbergh, Ben. 2019. David Benioff and D. B. Weiss’s rush to finish “Game of Thrones”. The Ringer. https://www.theringer.com/game-of-thrones/2019/5/9/18537794/game-of-thrones-ending-too-quickly-pacing (accessed 12 February 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Lindgren Leavenworth, Maria. 2015. The paratext of fan fiction. Narrative 23(1). 41–60.10.1353/nar.2015.0004Search in Google Scholar

Lunenfeld, Peter. 1999. Unfinished business. In Peter Lunenfeld (ed.), The digital dialectic: New essays on new media, 6–23. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/2418.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

McCracken, Ellen. 2013. Expanding Genette’s epitext/peritext model for transitional electronic literature: Centrifugal and centripedal vectors on Kindles and iPads. Narrative 21(1). 106–124.10.1353/nar.2013.0005Search in Google Scholar

Mäkelä, Maria. 2021. Viral storytelling as contemporary narrative didacticism: Deriving universal truths from arbitrary narratives of personal experience. In Susanna Lindberg & Hanna-Riikka Roine (eds.), The ethos of digital environments: Technology, literary theory and philosophy, 49–59. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003123996-6Search in Google Scholar

Page, Ruth E. 2018. Narratives online: Shared stories in social media. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316492390Search in Google Scholar

Pantozzi, Jill. 2015. We will no longer be promoting HBO’s Game of Thrones. The Mary Sue. https://www.themarysue.com/we-will-no-longer-be-promoting-hbos-game-of-thrones/ (accessed 11 October 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Pesce, Sara & Paolo Noto (eds.). 2016. The politics of ephemeral digital media: Permanence and obsolescence in paratexts. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315718330Search in Google Scholar

Pomerantz, Jeffrey. 2015. Metadata. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/10237.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Rabinowitz, Peter J. 1987. Before reading: Narrative conventions and the politics of interpretation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Reddit. 2015. https://old.reddit.com/r/gameofthrones/comments/25ftdy/season_4_meanwhile_somewhere_in_the_narrow_sea/chgtauo/ (accessed 12 February 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Reddit. 2017. https://www.reddit.com/r/gameofthrones/comments/49vmfn/s6_theory_why_gendry_hasnt_appeared_again/d0v9zd0/?sort=top (accessed 12 February 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Reddit. 2020. https://www.reddit.com/r/freefolk/comments/ij8h7k/the_legacy_of_a_bad_ending/ (accessed 12 February 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Reddit. 2023. https://www.reddit.com/r/freefolk/comments/10bvl74/crosspost_from_rlotrmemes_lotr_return_of_the_got/?sort=top (accessed 12 February 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Richards, Denzell. 2016. Historicizing transtexts and transmedia. In W. L. Benjamin, Dehry Kurtz & Mélanie Bourdaa (eds.), The rise of transtexts: Challenges and opportunities, 15–32. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Roine, Hanna-Riikka & Laura Piippo. 2021. Authorship vs. assemblage in digital media. In Susanna Lindberg & Hanna-Riikka Roine (eds.), The ethos of digital environments: Technology, literary theory and philosophy, 60–76. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003123996-7Search in Google Scholar

Scott, Suzanne. 2013. And they have a plan: Battlestar Galactica, ancillary content, and affirmational fandom. In Ethan Thompson & Jason Mittell (eds.), How to watch television, 320–330. New York: NYU Press.10.18574/nyu/9780814729465.003.0038Search in Google Scholar

Sedlmeier, Florian. 2018. The paratext and literary narration: Authorship, institutions, historiographies. Narrative 26(1). 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1353/nar.2018.0003.Search in Google Scholar

Skare, Roswitha. 2020. Paratext. Knowledge Organization 47(6). 511–519. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2020-6-511.Search in Google Scholar

Stanton, Zack. 2021. How the “culture war” could break democracy. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/05/20/culture-war-politics-2021-democracy-analysis-489900 (accessed 12 February 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Uricchio, William. 2016. Interactivity and the modalities of textual-hacking: From the Bible to algorithmically generated stories. In Sara Pesce & Paolo Noto (eds.), The politics of ephemeral digital media: Permanence and obsolescence in paratexts, 155–169. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Zelizer, Barbie. 1993. Journalists as interpretive communities. Critical Studies in Media Communication 10(3). 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295039309366865.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Figures of discourse in prose fiction

- Joseph Conrad’s reluctant raconteurs

- Audience-authored paratexts: legitimation of online discourse about Game of Thrones

- Horizontal metalepsis in narrative fiction

- “Small machines of words”: poetics, phonetics, and mechanisms of narrative realism in late twentieth-century Hip Hop

- Secondary storyworld possible selves: narrative response and cultural (un)predictability

- Explaining the innovation dichotomy: the contexts, contents, conflicts, and compromises of innovation stories

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Figures of discourse in prose fiction

- Joseph Conrad’s reluctant raconteurs

- Audience-authored paratexts: legitimation of online discourse about Game of Thrones

- Horizontal metalepsis in narrative fiction

- “Small machines of words”: poetics, phonetics, and mechanisms of narrative realism in late twentieth-century Hip Hop

- Secondary storyworld possible selves: narrative response and cultural (un)predictability

- Explaining the innovation dichotomy: the contexts, contents, conflicts, and compromises of innovation stories