Abstract

In this paper, we specify features of a narrative that are responsible for its suspensefulness. Taking Noël Carroll’s account of erotetic narrative as our point of departure, we argue that a narrative is experienced as suspenseful because it gives rise to so-called potentially inquiry terminating questions. Such questions suggest to readers that they are just about to get the information they are reading for. Due to this highly specific erotetic structure, suspenseful narratives trigger cognitive and emotional mechanisms that are associated with what has been called a “near miss” in studies on gambling behavior: a situation which suggests a player that she has almost achieved a favorable result. In spelling out the details of the theory, we propose both a causal explanation of narrative suspense and defining properties, such that instances of suspense can be distinguished from instances of other states of readerly excitement.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that some narratives are suspenseful while others are not, but there is no consensus in the literature as to what features of a narrative are responsible for its suspensefulness. In this paper, we specify such features, thereby proposing both a causal explanation of narrative suspense and defining properties of suspense, such that instances of suspense can be distinguished from instances of other states of readerly excitement. In developing our theory, we take Noël Carroll’s account of erotetic narrative as our point of departure.

***

To get off the ground in explaining the emergence of suspense in narrative consumption, we shall refer to the short horror story “The Brazilian Cat” by A. C. Doyle as our prime example. The story features a scene where Marshall, the protagonist, is trapped in a dungeon that houses the cage of a large cat of prey. Marshall soon actually faces the Brazilian cat as his vicious cousin Everard, the antagonist, starts to open the cage using a mechanism from outside the dungeon.

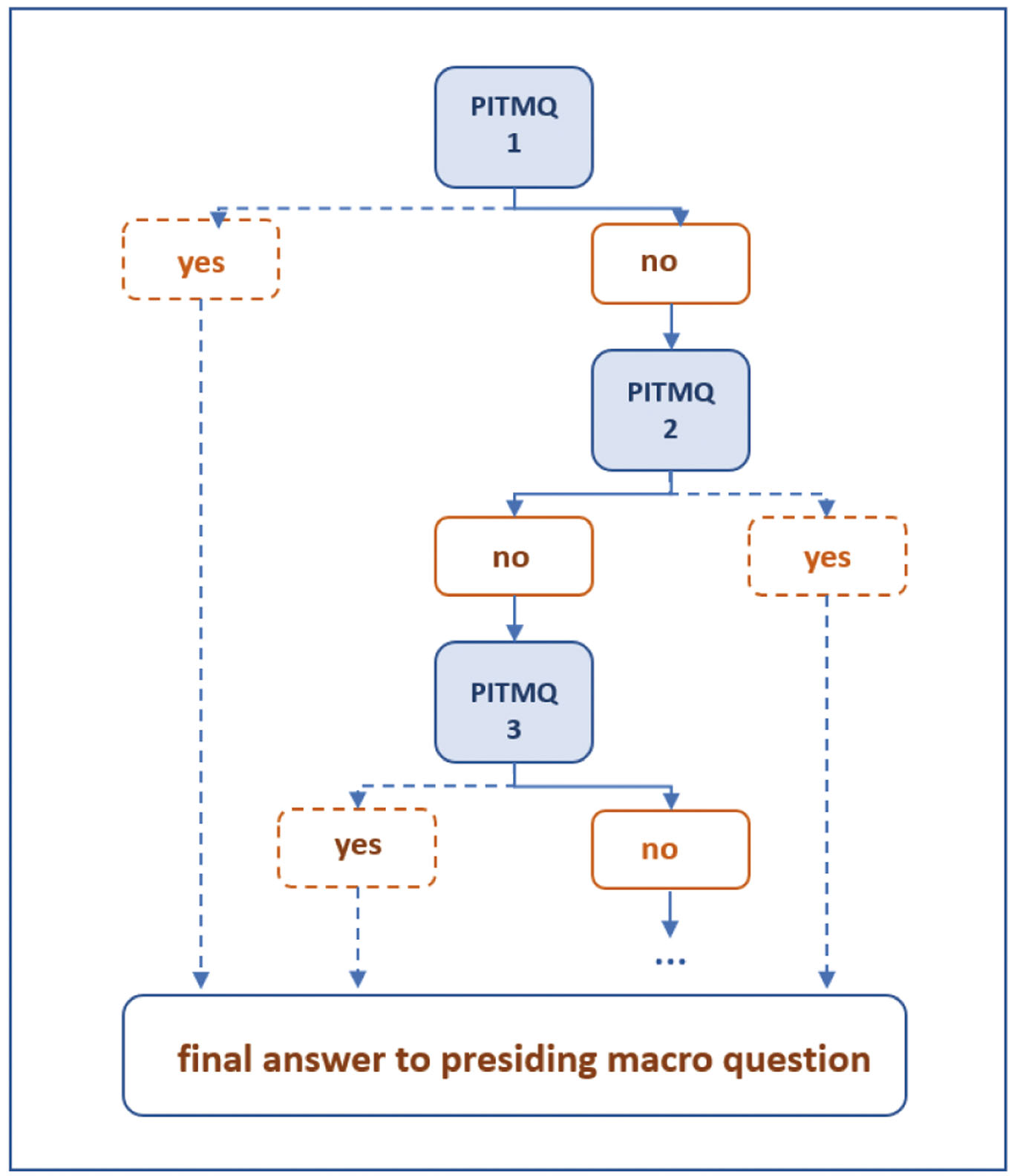

According to Noël Carroll’s account of erotetic narrative, readers of the passage understand that Marshall is in grave danger. This amounts to entertaining a particular event-directed question, namely whether Marshall will be hurt by the cat of prey: for the ensuing part of the narrative the reader’s attention is focused on what may answer this question, and it grounds what we may call the reader’s inquiry. As the text unfolds, the reader entertains a series of further event-directed questions, such as “Will Everard let Marshall out of the dungeon?”, “Will Marshall manage to keep the cage shut?”, and further on in the story: “Will Marshall be safe from the cat on top of the cage?”. Following Carroll, we may call the question that grounds the recipient’s reading inquiry a presiding macro question, as it governs a larger passage of text, while the questions that are brought up (and possibly answered) within the lifespan of a macro question will be referred to as micro questions.[1]

Carroll thinks that suspense can be explained in terms of certain properties of macro questions in particular. Thus, feelings of suspense ensue if a binary macro question has one answer that is deemed probable and immoral (in our case: Marshall is hurt by the cat of prey) and another answer that is deemed unlikely and moral (in our case: Marshall is saved from the cat of prey). Carroll’s theory is thereby very close to what has been dubbed the “standard account” of suspense which holds, roughly, that audiences fear that something bad happens which they deem likely while at the same time they hope that it does not happen.[2] Now, while we agree with Carroll that erotetic structure is at the heart of suspense, this is where we part company. In a nutshell, our theory maintains that readers experience suspense because they are repeatedly under the impression that they are just about to get the answer to a presiding macro question, only to learn that they don’t get it (yet).

Let us explain this idea a bit more fully now. The micro questions that we have just referred to have a curious thing in common. They are such that an answer to each of them could also answer the reader’s presiding macro question and thus terminate the reader’s inquiry. For example, if Everard lets Marshall out of the dungeon, the answer to the macro question is negative (the reader then knows that Marshall won’t be hurt by the cat of prey) and the reading inquiry is terminated. Conversely, if Everard does not let Marshall out of the dungeon, then the reader’s inquiry continues. As only one of its conceivable answers leads to inquiry termination, we may call “Will Everard let Marshall out of the dungeon?” a potentially inquiry terminating micro question (henceforth: PITMQ): it can but need not lead to inquiry termination.[3] The succession of several potentially inquiry terminating micro questions is possible because none of them (but the last one) turns out to actually terminate the inquiry (as, in our case, they are all answered in the negative).

We are now in a position to explain the excitement that is characteristic of experiences of suspense. Intuitively formulated, what happens is this: each time a PITMQ comes up, things look to the reader as if the text provides an answer to her presiding macro question. The reader is prone to think that inquiry termination is imminent and that she thus gets what she wants. The thought “THIS is it!” sparks the excitement.[4]

Let us describe the elements of this explanation a bit more fully. First, why does a PITMQ lead to the impression that inquiry termination is imminent? Now, part of the answer lies in the very fact that a PITMQ is recognized as such. If you recognize a salient question as potentially inquiry terminating, this in itself suggests that the likelihood of inquiry termination has been given a rise. The subjective probability of inquiry termination in the face of a PITMQ is higher than the subjective probability of inquiry termination with nothing on the horizon that might terminate your inquiry, so to speak. Second, upcoming PITMQs are typically such that their inquiry terminating character can be easily and vividly imagined. Psychological research suggests that both ease of imaginability and imaginative vividness are prone to exert an influence on readers’ estimations.

Let’s start with ease of imaginability. Kahneman and Tversky maintain that problem solvers engage in a simulation exercise when they consider different solutions to some problem, and they conclude that the “ease with which the simulation of a system reaches a particular state is eventually used to judge the propensity of the (real) system to produce that state” (1982: 201–202). In particular, the ease with which one can imagine the solution to some problem positively correlates with one’s estimation of the likelihood that this solution is correct (or works or obtains). We take it that, in a narrative setting, readers are prone to judge a possible upcoming event more likely if they can easily imagine its occurrence. This may hold true for the reader’s reading inquiry when she faces a PITMQ. As we have seen, at some point in the story Marshall desperately tries to keep the cage shut by strenuously pulling the cage door. The text gives a detailed description of him doing so. The reader knows that all it takes for Marshall to be safe is to keep the door shut. Kahneman and Tversky’s “simulation heuristic” suggests that, as it is easy for the reader to imagine Marshall keeping the door shut, she is prone to deem this outcome an especially lively option. And since this possible future event answers her presiding macro question (“Will Marshall be hurt by the cat of prey?”), she is prone to deem inquiry termination more likely than other possible story continuations which do not involve imminent inquiry termination.

The fact that the reader vividly imagines what it takes for Marshall to be safe may have a similar effect: the more vividly you imagine some event E, the more weight or importance E will gain in your thoughts. Thus, according to the so-called vividness criterion, subjects are much more influenced in their thinking by vivid information than by information that is “pale”.[5] The reader’s imaginings are vivid in that they fulfill two important “factors contributing to the vividness of information”: the text describes a scene in great detail (“concreteness”) and the whole situation is entrenched with emotion (“emotional interest”) (Nisbett and Ross 1980: 45–49). Taken together, both the ease with which the reader can imagine a solution to her problem (i. e., the termination of her inquiry / the acquisition of information that answers her presiding macro question) and the vividness of her imagining may lure the reader into thinking that “THIS is it” – that the termination of her inquiry is imminent. We will describe this cognitive state in more detail in a minute.

Before that, let’s turn to the second part of our explanation. The reader is prone to think that inquiry termination is imminent and that she thus gets what she wants. Does this cognitive engagement spark excitement?

There is broad empirical evidence that thinking that you are close to a goal triggers excitement. This evidence has been gathered in studies on gambling behavior with respect to so-called “near misses”. These occur “when the elements of a game or task ‘suggest’ to a player that they have almost achieved a favourable result” (Pisklak et al. 2020: 611), such as when a gambler at a slot machine sees “cherry-cherry-lemon” and three cherries amounts to a win. As several studies have shown, “there is considerable evidence that near-miss events can affect subjective measures (e. g., self-reports) and physiological responses (e. g., skin conductance, heart rate, or brain activity)” (Pisklak et al. 2020: 614).[6] If you think that you are about to get what you want (“cherry-cherry-cherry”), then this has been described as a “heart stopper”; and nearly missing it has “some of the excitement of a win” but may also feature “frustration” (Reid 1986: 34, 33).

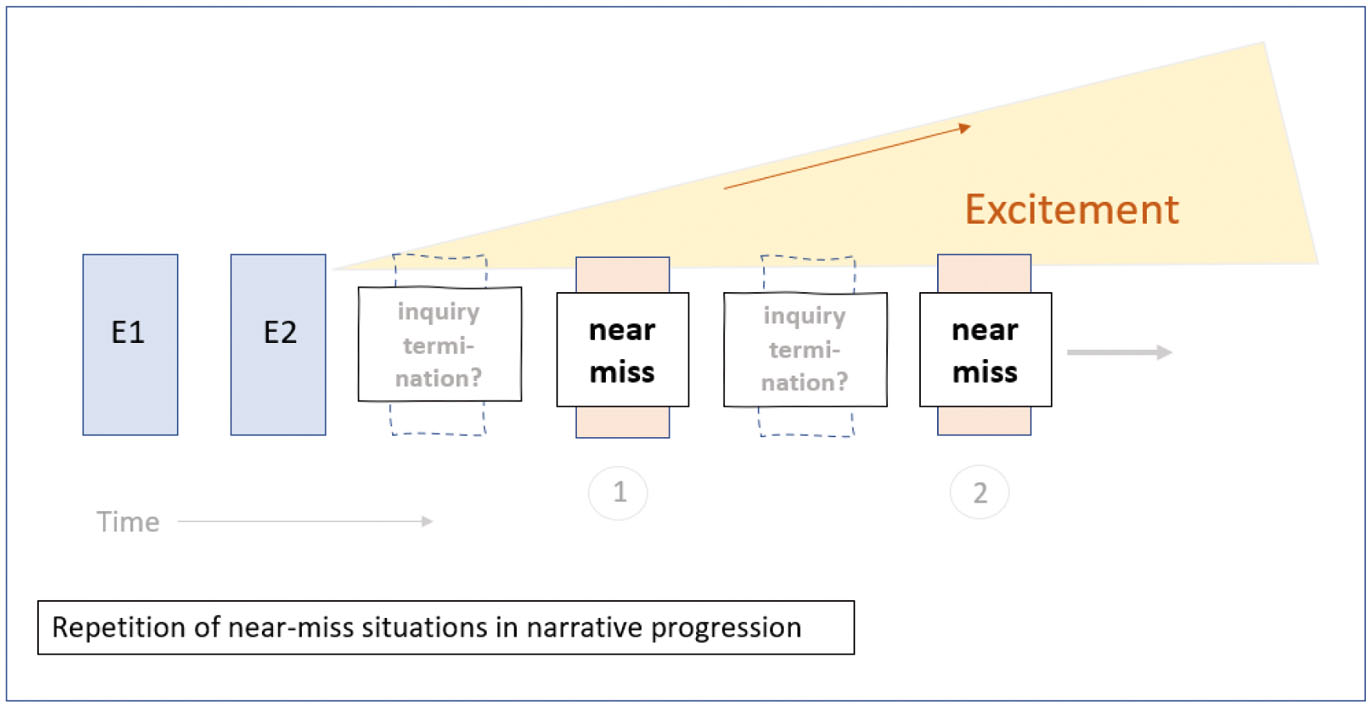

For our purposes, it does not matter much which psychological explanation for the excitement that goes along with a near miss is correct. Suffice it to say that we are somehow hard-wired to experience excitement in near-miss situations. What we do need to stress is that the reader is indeed in a situation that has important features of a near miss: the reader repeatedly deems herself close to her goal of information acquisition. Each time she faces a PITMQ, she can easily and vividly imagine an event that, if only it takes place, answers the PITMQ and thereby also terminates her inquiry. And once it turns out that the answer to a PITMQ does not terminate the inquiry after all, this completes a near miss concerning her goal of information acquisition. To the reader, the situation repeatedly looks as if she is just about to get the information she is reading for, and then it turns out that she doesn’t get it (yet).

We take it that a typical suspense story supplies several PITMQs, thus presenting the reader with a succession of near miss situations. This is prone to keep up feelings of suspense, and probably also to intensify them, such that the readers’ excitement grows stronger if they recurrently think that “THIS is it!”.

Note, finally, that the somewhat unclear affective valence of near miss situations may match the emotional valence of felt suspense. While “some of the excitement of a win” should be experienced as a positive emotion, “frustration” has a negative valence. We shall come back to this point in our closing section.

To sum things up, then, the order of explanation so far unravels like this: the reader’s reading inquiry (her goal directed behavior that involves focused attention and a set of assumptions, expectations and wants) is grounded in (explained in terms of) her entertaining a presiding macro question that the text makes salient. At recurring points in the story, she entertains a PITMQ, that is, she encounters situations that look like her reading inquiry is about to be terminated, as she can easily and vividly imagine what it takes to imminently terminate her inquiry. Recurrently, these vivid imaginings constitute near-miss situations for the reader. They spark and, if repeated, maintain or intensify her excitement.

***

It is time now to be more specific about the reader’s thought that the termination of the reading inquiry is imminent. We do so by way of considering a counterexample. Suppose that, upon reading a suspenseful passage of text, you are aware that you are just in the middle of the chapter that, slowly but surely, builds a suspense arch. Doesn’t that tell you that the termination of your reading inquiry most likely is not imminent? (In other words, doesn’t that tell you that any event-directed micro question you encounter does not give you the answer to your presiding macro question?) We think that it may. And if it does, this may amount to an interfering condition, i. e., a causal factor that may diminish suspense, or even cause it to vanish or prevent it.

At this point, a remark on terminology is in order. In our attempt to explain what causes feelings of suspense in readers, we shall distinguish between three different types of causal factors: First, some causal factors are necessary for the phenomenon to occur. Call them constitutive causal factors. Our theory maintains that entertaining PITMQs is constitutive of suspense in this sense. Second, there are causal factors that may be referred to as background conditions or preconditions, such as the reader’s general ability to vividly imagine a situation. Preconditions must be met for suspense to obtain too, as they play an ineliminable (necessary) role somewhere in the causal network that brings about the target state. But preconditions do not play a role in defining our target phenomenon, and it is not the task of a theory of suspense to enumerate all or any of them. Third, there are causal factors which may intensify or diminish feelings of suspense. Call these intensifiers (or diminishers, respectively). Later on, we shall see that there are many factors which may intensify or diminish feelings of suspense.

Now, to repeat, knowing that the answer to an event-directed micro question does not give you the answer to your presiding macro question may amount to an interfering condition that may diminish suspense, or even cause it to vanish or prevent it. This, however, is not the whole story. It is also possible that a reader believes that inquiry termination is in fact not imminent and still experiences feelings of suspense. In order to see how this is possible, we need to unpack the prevalent notion of the “impression of the imminence of inquiry termination”. If our theory says that the reader deems herself close to her goal of information acquisition, this is just shorthand for a more complex set of attitudes:

Firstly, the reader’s thought that the text raises a PITMQ is justified. The reader realizes that the text supplies her with reasons to believe that the presiding macro question she is reading for may be answered now. Thus, the narrative does address the presiding macro question in a way that makes her consider certain answering options, and at least one of these options can be imagined vividly (as a particularly lively option, so to speak). Note that having these reasons is in no way diminished by the belief that the presiding macro question is in fact not answered now. You may thus believe that your reasons for thinking that your presiding macro question is answered now are not decisive. But still, you do have some (non-decisive) reason to think that an answer is imminent. This in turn means that the thought that “My presiding macro question is answered NOW” comes naturally, as it were. It is not speculative or far-fetched. (Compare: You may know that the sun doesn’t revolve around the earth, but still, from any point of view on earth, the sun surely looks as if it did. Your visual impression thereby supplies you with a non-decisive reason for assuming that the sun revolves around the earth.)

Secondly, remember that readers can easily and vividly imagine what it takes to actually terminate their reading inquiry. (In our example: the reader imagines that Marshall tries to close the door of the cage and she can easily and vividly imagine that he succeeds.) So even if the reader believes that Marshall doesn’t succeed, the text still prompts concrete, vivid imaginings of a situation where he is pretty close and maybe succeeds. This combination of a belief and an interfering vivid thought is not unlike watching a skilled tightrope artist: You believe that she is perfectly safe, but still you are on the edge of your seat because you are presented with strong visual evidence that she is performing a dangerous task which “must be over any minute now”.[7]

In sum, then, we suggest that what is decisive in creating suspense is that readers have the (recurring) vivid thought that they are just about to get the answer to the question they are reading for. In contrast, what is not decisive is that they put much credence in the thought that the answer to a PITMQ actually terminates their inquiry. While this may of course happen (and while it may coincide with the emergence of suspense, or amount to an intensifying condition), our hypothesis is that it need not: vividly entertaining the respective thought, and then possibly experiencing a near-miss situation, is enough for creating and maintaining feelings of suspense.

Note that, at this point we also have some resources for explaining what may be termed failed suspense – i. e., narratives which are perceived as “wannabe” suspense-stories which, however, fail to exert the intended effect on readers.[8] First, a reader may notice that the text supplies some reasons for deeming the end of the reading inquiry close, but these reasons may be perceived as too weak or flimsy. (This may actually be perceived as annoying.) Second, the author may have failed in creating a narrative environment such that the reader can easily and vividly imagine the relevant events. In both scenarios, the relevant textual phenomena amount to what we have called diminishing conditions.

***

The standard account of suspense assumes that suspense involves a reader’s prospective emotions (usually conceptualized as hope and fear) towards an outcome that is unknown to the reader.[9] But if suspense necessarily involves a reader’s lack of information concerning the outcome of the story, how can she feel suspense upon repeated encounters of the story?[10] Our theory could be said to have difficulties explaining the occurrence of suspense upon repeated encounters of the same text simply because the theory is couched in terms of a reading inquiry (you want to know the answer to a presiding macro question) and vividly imagining (what amounts to) potentially inquiry terminating micro questions. But why would anyone inquire into what one already knows, or ask a question where one knows the answer? It seems that, once a reader is supplied with the relevant knowledge, our theory does not even get off the ground in explaining feelings of suspense.

Our reply to this objection is threefold. First, it is plausible that upon repeated encounters with the same text, readers do understand that the text addresses certain questions. This is a basic requirement of experiencing a text as coherent which is independent of how many times it is read. Accordingly, even if readers cannot be said to pose these questions to themselves or to be somehow committed to finding an answer or to attach a high subjective importance to finding an answer, they still fully understand that the text is written such that these questions are being addressed. Alternatively put, we may say that a reader who understands the text thereby grasps the questions that are addressed by the text.[11]

Second, entertaining a presiding macro question (sc. understanding that the text addresses a certain macro question) as well as a series of related PITMQs may be sufficient for sparking feelings of suspense. This is so because the factors we have identified as crucial on the causal pathway may all be present: readers have the (recurring) vivid thought that they are just about to get the answer to the question they are entertaining. The ease with which readers can imagine the termination of their (“entertained”) inquiry and the vividness of their imaginings are what does the trick, so to speak, as these factors account for the impression of imminence which in turn sparks the reader’s excitement. As we have argued, beliefs as to what will happen may be present (although, perhaps, they are rather non-occurrent), but they need not get in the way.

Third, if the foregoing is correct then we may still think that a high subjective importance attached to answering the presiding macro question is something that may intensify feelings of suspense, but it is not necessary for its creation. (Again, entertaining the question is enough.) As such, attaching a high subjective importance to getting an answer to a presiding macro question (such that you actually read for the answer) is on the same page as other potential intensifiers of feelings of suspense. For instance, “The Brazilian Cat” features an atmosphere of mystery, a rather gruesome scenery, and it contains violence up to a point where the protagonist’s life is at stake.[12] These features may all intensify the emotional state of the reader and thus contribute to her excitement. Note that these factors do not constitute her feelings of suspense, but rather contribute to their intensity. (We will address the question of defining conditions for feelings of suspense in a minute.)

Why do theorists think that suspense involves uncertainty concerning story outcomes? Suspense undeniably is a forward-looking state, and a pretty standard situation is that you read a story for the first time and don’t know its future proceedings. As our theory has it, upon reading a suspenseful passage of text, you are entertaining a presiding macro question and a set of specific micro questions. You may read for the answer to this macro question and thus attach a high subjective importance to answering it. However, what carries the explanatory weight in our theory of suspense is not the subjective importance attached to answering the presiding macro question but rather something that happens along the way, so to speak: the text is written such that you come to vividly think that an (endorsed or merely entertained) inquiry is over the next minute. This causes the relevant excitement, not some bare quest for knowledge in a state of uncertainty.

So, let’s conclude. Whether or not a reader experiences suspense upon repeated encounters of the same text is an empirical question. Unlike theories maintaining that uncertainty is a constitutive causal factor of suspense, our theory does not predict any particular reaction on the side of a recurring reader. However, if a reader confirms that she has experienced suspense upon re-reading some text, then this self-report can be taken at face value. It is possible that constitutive causal factors of suspense are in place, and consequently there is no theoretical need to suspect, say, that readers misidentify their excitement as suspense the second time around (while in fact it must be something else that they feel).[13]

***

Our theory not only takes up basic insights from Noël Carroll’s erotetic theory of suspense but also bears some resemblances to Aaron Smuts’ “desire frustration theory of suspense”. According to Smuts, what is necessary and sufficient for suspense is “the frustration of a strong desire to affect the outcome of an imminent event”.[14] As Smuts points out, this frustration may occur upon repeated consumptions of the same narrative:

The desired outcome has not yet occurred when the story is still unfolding, so there is still something to desire even if you know how the situation will be resolved. One may know the outcome of a narrative, as audiences do with Touching the Void, but still want to see it take place – to see the climbers return to camp – and want to lend aid in times of crisis. Stories can arouse and frustrate many of the same desires on subsequent encounters. (2008: 286)

This explanation is structurally similar to ours in that it does not make the occurrence of feelings of suspense depend on a reader’s lack of knowledge concerning story outcomes. It is also similar to ours in that it appeals to some psychological principle in order to explain occurrences of suspense. Indeed, it is even compatible with our theory to the extent that a near miss concerning the termination of one’s reading inquiry may cause feelings of frustration in readers. As we shall argue in the next section, however, the reader’s feelings of frustration qualify as feelings of suspense only if they are caused in the right way, namely by experiencing a near-miss situation that has the accordant erotetic foundation.

Indeed, Smuts’ theory has some explanatory burden our theory lacks. He must explain why standard readers who do not think that they can interfere with the story and thus develop no desire to affect the outcome of an imminent event in the first place nevertheless experience suspense. And, assuming that readers do develop the accordant desires, why should my frustration in keeping vicious Everard from punishing his wife in “The Brazilian Cat” count as an instance of felt suspense? Arguably, this scene is not suspenseful at all, and this suggests that Smuts has not really identified a sufficient condition for “suspense”.

We have conceded so far that feelings of frustration may be part and parcel of the excitement that a near miss concerning the termination of one’s reading inquiry may cause. But desire frustration may also play another part in the reading experience. In particular, if readers do develop the frustration of a strong desire to affect the outcome of an imminent situation, this may amount to yet another intensifier of feelings of suspense. Consider the report of the “banana-gun game” by Donald Beecher:

My two children are at the breakfast table, back when they were just little kids. I would stuff the banana in my pocket and chant in as suspenseful a voice as I could the “da-duh, da-duh, da-duh-da-duh-da-duh” that invariably preceded the draw-and-shoot routine. Do not ask me why they loved this so much, and over and over again, with little diminution of interest or of nervous response and release. (2007: 272)

Our theory has it that suspense is created on the part of the children because they entertain the presiding macro question (they understand that this game is all about the question) “Will the shooter draw?” and they also get it that this game may be over any minute now. In other words, they can easily and vividly imagine that the shooter pulls and fires his gun, because they get strong visual evidence that this is what goes on in their game of make-believe. In other words, they recurrently process a PITMQ (“Will the shooter draw and fire NOW?”), and they recurrently experience a near miss once it turns out that the shooter’s movement was just another feint. This is what sparks their excitement and, as we shall see in a minute, this is what makes their experience qualify as an experience of suspense.[15] But the children may of course also suffer from their imagined inability to prevent the vicious shooter from pulling his gun. This may intensify their excitement, and thereby heighten the felt quality of suspense. However, frustration may also amount to what we have called a diminisher, i. e., a causal condition that reduces someone’s excitement rather than foster it.[16] (We can leave this open as it does not touch the heart of our theory.)

Smuts introduces his theory by pointing to what we may term “Hitchcock-cases”. In such cases, there is an asymmetry of knowledge between characters and viewers: The characters sit at a table and only we, the viewers, know that there’s a bomb under the table. Smuts thinks that the suspensefulness of these scenes can be explained by the viewer’s frustrated desire to remove the bomb or warn the characters (or the like). But note that our theory has the resources to explain suspense in Hitchcock-cases too. If the viewer develops feelings of suspense, then she will watch the movie (“read” the narrative) for an answer to the presiding macro question whether the bomb will go off. During this, the film viewer will repeatedly encounter shots such as closeups of the bomb under the table. And these shots will (recurrently) vividly call to mind the pressing micro question “Will it go off NOW?” as a potentially inquiry terminating question. And for as long as the narrative answers these potentially inquiry terminating questions in the negative, this series of vivid prompts to visualize the bomb constitutes near-miss situations which in turn explain the viewers’ feelings of suspense.

If neither ignorance of story outcomes nor desire frustration are necessary for suspense, how about variants of apprehension? The standard account of suspense claims that suspense involves fear that an unwanted (but probable) outcome ensues.[17] Note, firstly, that this theory has some additional explanatory burdens. Why should we fear an outcome that we know is merely fictional? Why do subjects enjoy suspense, given that fear (or apprehension) is an integral part of it? Secondly, isn’t suspense phenomenologically quite different from apprehension, or fear? Thirdly, it is possible to experience suspense upon reading a story that does not make an apprehended outcome likely (or so it seems to us). Consider real-life cases first. Apparently, one may experience suspense watching a soccer game without rooting for any of the teams. As the center forward runs upfield, you may feel intense excitement without really fearing anything (for you, if the center forward scores that’s just as good as if he misses).[18] Our theory explains the phenomenon thus: If you understand that soccer is a game that is won by scoring, then you are prone to think “This is it”, i. e. you vividly experience the forward’s action as answering not only a “Will he score now?”-question but also as answering a “Who wins this game by scoring?”-macro question, thereby potentially terminating an inquiry for the winning team. If this is what grounds your excitement, then (as we shall argue in the next section) your feelings qualify as feelings of suspense.

Quite similarly, a story may involve you in some inquiry such that you couldn’t say whether any particular outcome is good or bad. Mystery may be a case in point. For typical mystery stories, there is no particular apprehensibility rating attached to the different solutions. (On account of apprehensibility, it doesn’t matter whether the gardener or the butler did it.) But it seems that there is suspense in these stories. Thus, in M. R. Rinehart’s mystery story “Locked Doors”, the protagonist, Miss Adams, does not know what’s wrong with the house where she investigates in an undercover mission, until in the very end a somewhat surprising answer ensues. The text presents us with a sequence of potentially inquiry terminating questions as we follow Miss Adams around the house. If readers describe their reading experience of this story as suspenseful (as some do), we suggest that this is not so because they think that some apprehensible outcome is made likely, but because they are presented with an unfolding story that repeatedly makes them think that Miss Adams is just about to solve the riddle which in turn would amount to immediate inquiry termination.

***

Having described the (rough contours of the) causal story that leads to feelings of suspense, we may turn now to the conceptual task of proposing a definition of the term “suspense”. We think that a suitable way to distinguish feelings of suspense from other feelings of excitement is with reference to the cognitive component of the experience. Roughly, a reader’s state of excitement qualifies as suspense if, and only if, the excitement is caused by certain cognitive states. These cognitive states are referred to above as the reader’s entertaining of a series of particular questions that are prompted by the text. More precisely:

Def Sus

The excitement E a reader R experiences upon reading a narrative qualifies as suspense if, and only if, E is caused by the following set of cognitive states:

R entertains an event-directed macro question (Q), and

R vividly entertains a series of micro questions (q1 ... qn) such that

q1 ... qn are event-directed micro questions

q1 ... qn are potentially inquiry terminating questions concerning Q

q1 ... qn are narratively presented such that R deems herself/himself close to answering Q.

We think that DefSus has a number of advantages to which we shall turn in closing.

First, note that our account does not determine the affective valence (also referred to as the hedonic tone) of felt suspense. The literature on suspense is notoriously unclear as to whether suspense feels good or is enjoyed, or whether it is rather experienced as unpleasant. Some theories of suspense seem to strongly lean towards the negative pole. If you think that suspense is comprised of desire frustration, apprehension, or fear, then it takes some effort (to say the least) to explain how suspense can be experienced as pleasant. Near-miss situations, in contrast, are not fixed in this regard. To some, they seem to carry some of the excitement of a win while to others they carry the frustration of a loss. Some may experience both of these. We think that that’s how it should be: a theory of suspense should not decide the matter of affective valence but be able to explain both positive and negative affective valences of suspense.

Second, note that suspense is often connected to reading motivation. People regularly claim that suspense “glues” them so some text and that the suspensefulness of a text is what makes for a “page-turner”. Our theory lends itself quite easily to explaining this: suspense is all about questions and the expectation of imminent answers. You are the rabbit, and the text waggles a carrot right in front of your nose. So, you’re after it. But each time you think you get it, the text pulls it back, only to return waggling with it in front of your nose a minute later.

Third, our account may be useful for explaining narrative choices.[19] This may come down to different things. For one, the central cognitive ingredients of suspense are the questions that are on the mind of a reader. These questions are rooted in the erotetic structure of the narrative text. An author’s strategic choices of giving information can be understood as addressing particular questions in particular ways. These can be studied in any detail, and doing so amounts to investigating the detailed linguistic basis of suspenseful texts. For another, we have seen that suspense also depends on the ease and vividness of readers’ imaginings, and it is an interesting task to investigate the narrative means by which such effects are achieved.

Fourth, while DefSus is a definition of a psychological concept and thus has psychological states as its domain of application, we can easily adapt the definition such that “suspenseful” applies to passages of a narrative text (or other media). Roughly, a narrative (or some of its parts) is suspenseful if, and only if, it gives rise to the feelings specified in the definition. There are of course several options for fleshing this out further. For instance, one could say that “gives rise” pertains to standard situations, or that it contains a normative qualification (“is appropriately interpreted as giving rise”).

Acknowledgement

Work on this paper has been funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Grant Number: 441917136 and the Österreichischer Wissenschaftsfonds (FWF, Austrian Science Fund) – Grant Number: I 4858.

References

Beecher, Donald. 2007. Suspense. Philosophy and Literature 31(2). 255–279. 10.1353/phl.2007.0022Search in Google Scholar

Carroll, Noël. 1996. Theorizing the moving image. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Carroll, Noël. 2001. Beyond aesthetics: Philosophical essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511605970Search in Google Scholar

Clark, Luke, Ben Crooks, Robert Clarke, Michael R. F. Aitken & Barnaby D. Dunn. 2012. Physiological responses to near-miss outcomes and personal control during simulated gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies 28. 123–137. 10.1007/s10899-011-9247-zSearch in Google Scholar

Gendler, Tamar Szabó. 2008. Alief and belief. The Journal of Philosophy 105(10). 634–663. 10.5840/jphil20081051025Search in Google Scholar

Kahneman, Daniel & Amos Tversky. 1982. The simulation heuristic. In D. Kahneman, P. Slovic & A. Tversky (eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases, 201–208. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511809477.015Search in Google Scholar

Nisbett, Richard E. & Lee Ross. 1980. Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. Search in Google Scholar

Norden, Martin F. 1980. Toward a theory of audience response to suspenseful films. Journal of the University Film Association 31(1/2). 71–77. Search in Google Scholar

Ohler, Peter. 1994. Zur kognitiven Modellierung von Aspekten des Spannungserlebens bei der Filmrezeption [On the cognitive modeling of aspects of suspense experience during film reception]. montage AV – Zeitschrift für Theorie und Praxis audiovisueller Kommunikation [Montage AV – Journal for Theory and Practice of Audiovisual Communication] 3(1). 133–141. Search in Google Scholar

Ortony, Andrew, Gerald L. Clore & Allan Collins. 1988. The cognitive structure of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511571299Search in Google Scholar

Pisklak, Jeffrey M., Joshua J. H. Yong & Marcia L. Spetch. 2020. The near‑miss effect in slot machines: A review and experimental analysis over half a century later. Journal of Gambling Studies 36. 611–632. 10.1007/s10899-019-09891-8Search in Google Scholar

Reid, R. L. 1986. The psychology of the near miss. Journal of Gambling Behavior 2. 32–39. 10.1007/BF01019932Search in Google Scholar

Smuts, Aaron. 2008. The desire-frustration theory of suspense. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 66(3). 281–290. 10.1111/j.1540-6245.2008.00309.xSearch in Google Scholar

Smuts, Aaron. 2021. The paradox of suspense. In E.N. Zalta (ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/paradox-suspense/ (accessed 8 October 2023). Search in Google Scholar

Uidhir, Christy Mag. 2011. An eliminativist theory of suspense. Philosophy and Literature 35(1). 121–133. 10.1353/phl.2011.0000Search in Google Scholar

Velleman, Dan Bridges, David Beaver, Emilie Destruel, Dylan Bumford, Edgar Onea & Liz Coppock. 2012. It-clefts are IT (inquiry terminating) constructions. Proceedings of SALT 22. 441–460. 10.3765/salt.v22i0.2640Search in Google Scholar

Yanal, Robert J. 1999. Paradoxes of emotion and fiction. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Dieses Werk ist lizensiert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Living a storied life: An interview with Mike Baynham

- Uncertainty and the limits of narrative: An introduction

- Whose uncertainty? Addressing the intersectional reader through the wound of trauma

- Disconnective futures: Uncertainty, unfathomability, and the collapse of narrative crisis management

- Climate uncertainty, social media certainty: A story-critical approach to climate change storytelling on social media

- Getting out of history: Levitation and paralysis in Sebald and Nabokov

- The nearly missed account of narrative suspense

- Review

- Karen Petroski. Fictionality. London & New York: Routledge, 2023. vii+211 pp. ISBN: 9780367752316 (hardback) / 9780367752293 (paperback) / 9781003161585 (ebook).

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Frontmatter

- Living a storied life: An interview with Mike Baynham

- Uncertainty and the limits of narrative: An introduction

- Whose uncertainty? Addressing the intersectional reader through the wound of trauma

- Disconnective futures: Uncertainty, unfathomability, and the collapse of narrative crisis management

- Climate uncertainty, social media certainty: A story-critical approach to climate change storytelling on social media

- Getting out of history: Levitation and paralysis in Sebald and Nabokov

- The nearly missed account of narrative suspense

- Review

- Karen Petroski. Fictionality. London & New York: Routledge, 2023. vii+211 pp. ISBN: 9780367752316 (hardback) / 9780367752293 (paperback) / 9781003161585 (ebook).